PhD students’ mental health is poor and the pandemic made it worse – but there are coping strategies that can help

Senior Lecturer in Technology Enhanced Learning, The Open University

Assistant Professor in Strategy and Entrepreneurship, UCL

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University College London and The Open University provide funding as founding partners of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A pre-pandemic study on PhD students’ mental health showed that they often struggle with such issues. Financial insecurity and feelings of isolation can be among the factors affecting students’ wellbeing.

The pandemic made the situation worse. We carried out research that looked into the impact of the pandemic on PhD students, surveying 1,780 students in summer 2020. We asked them about their mental health, the methods they used to cope and their satisfaction with their progress in their doctoral study.

Unsurprisingly, the lockdown in summer 2020 affected the ability to study for many. We found that 86% of the UK PhD students we surveyed reported a negative impact on their research progress.

But, alarmingly, 75% reported experiencing moderate to severe depression. This is a rate significantly higher than that observed in the general population and pre-pandemic PhD student cohorts .

Risk of depression

Our findings suggested an increased risk of depression among those in the research-heavy stage of their PhD – for example during data collection or laboratory experiments. This was in contrast to those in the initial stages, or who were nearing the end of their PhD and writing up their research. The data collection stage was more likely to have been disrupted by the pandemic.

Our research also showed that PhD students with caring responsibilities faced a greatly increased risk of depression. In our our study , we found that PhD students with childcare responsibilities were 14 times more likely to develop depressive symptoms than PhD students without children.

This does align with findings on people in the general UK population with childcare responsibilities during the pandemic. Adults with childcare responsibilities were 1.4 times more likely to develop depression or anxiety compared to their counterparts without children or childcare duties.

It was also interesting to find that PhD students facing the disruption caused by the pandemic who did not receive an extension – extra financial support and time beyond the expected funding period – or were uncertain about whether they would receive an extension at the time of our study, were 5.4 times more likely to experience significant depression.

Our research also used a questionnaire designed to measure effective and ineffective ways to cope with stressful life events. We used this to look at which coping skills – strategies to deal with challenges and difficult situations — used by PhD students were associated with lower depression levels. These “good” strategies included “getting comfort and understanding from someone” and “taking action to try to make the situation better”.

Interestingly, female PhD students, who were slightly less likely than men to experience significant depression, showed a greater tendency to use good coping approaches compared to their counterparts. Specifically, they favoured the above two coping strategies that are associated with lower levels of depression.

On the other hand, certain coping strategies were associated with higher depression levels. Prominent among these were self-critical tendencies and the use of substances like alcohol or drugs to cope with challenging situations.

A supportive environment

Creating a supportive environment is not solely the responsibility of individual students or academic advisors. Universities and funding bodies must play a proactive role in mitigating the challenges faced by PhD students.

By taking proactive steps, universities could create a more supportive environment for their students and help to ensure their success.

Training in coping skills could be extremely beneficial for PhD students. For instance, the University of Cambridge includes this training as part of its building resilience course .

A focus on good strategies or positive reframing – focusing on positive aspects and potential opportunities – could be crucial. Additionally, encouraging PhD students to seek emotional support may also help reduce the risk of depression.

Another example is the establishment of PhD wellbeing support groups , an intervention funded by the Office for Students and Research England Catalyst Fund .

Groups like this serve as a platform for productive discussions and meaningful interactions among students, facilitated by the presence of a dedicated mental health advisor.

Our research showed how much financial insecurity and caring responsibilities had an effect on mental health. More practical examples of a supportive environment offered by universities could include funded extensions to PhD study and the availability of flexible childcare options.

By creating supportive environments, universities can invest in the success and wellbeing of the next generation of researchers.

- Higher education

- Mental health

- Coping strategies

- PhD students

- Give me perspective

Service Delivery Consultant

Newsletter and Deputy Social Media Producer

College Director and Principal | Curtin College

Head of School: Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences

Educational Designer

Managing While and Post-PhD Depression And Anxiety: PhD Student Survival Guide

Embarking on a PhD journey can be as challenging mentally as it is academically. With rising concerns about depression among PhD students, it’s essential to proactively address this issue. How to you manage, and combat depression during and after your PhD journey?

In this post, we explore the practical strategies to combat depression while pursuing doctoral studies.

From engaging in enriching activities outside academia to finding supportive networks, we describe a variety of approaches to help maintain mental well-being, ensuring that the journey towards academic excellence doesn’t come at the cost of your mental health.

How To Manage While and Post-Phd Depression

| – Participate in sports, arts, or social gatherings. – Temporarily remove the weight of your studies from your mind. | |

| – Find a mentor who is encouraging and positive. – Look for a ‘yes and’ approach to boost morale. | |

| – Regular exercise like walking, swimming, gym combats depression – Improves mood and overall wellbeing. | |

| – Choose a graduate program that fosters community. – Ensure open discussion and support for mental health. – Select a university with the right support system. | |

| – Understand your choices in the PhD journey. – Consider deferment, pause, or quitting if needed. |

Why PhD Students Are More Likely To Experience Depression Than Other Students

The journey of a PhD student is often romanticised as one of intellectual rigour and eventual triumph.

However, beneath this veneer lies a stark reality: PhD students are notably more susceptible to experiencing depression and anxiety.

This can be unfortunately, quite normal in many PhD students’ journey, for several reasons:

Grinding Away, Alone

Imagine being a graduate student, where your day-to-day life is deeply entrenched in research activities. The pressure to consistently produce results and maintain productivity can be overwhelming.

For many, this translates into long hours of isolation, chipping away at one’s sense of wellbeing. The lack of social support, coupled with the solitary nature of research, often leads to feelings of isolation.

Mentors Not Helping Much

The relationship with a mentor can significantly affect depression levels among doctoral researchers. An overly critical mentor or one lacking in supportive guidance can exacerbate feelings of imposter syndrome.

Students often find themselves questioning their capabilities, feeling like they don’t belong in their research areas despite their achievements.

Nature Of Research Itself

Another critical factor is the nature of the research itself. Students in life sciences, for example, may deal with additional stressors unique to their field.

Specific aspects of research, such as the unpredictability of experiments or the ethical dilemmas inherent in some studies, can further contribute to anxiety and depression among PhD students.

Competition Within Grad School

Grad school’s competitive environment also plays a role. PhD students are constantly comparing their progress with peers, which can lead to a mental health crisis if they perceive themselves as falling behind.

This sense of constant competition, coupled with the fear of failure and the stigma around mental health, makes many hesitant to seek help for anxiety or depression.

How To Know If You Are Suffering From Depression While Studying PhD?

If there is one thing about depression, you often do not realise it creeping in. The unique pressures of grad school can subtly transform normal stress into something more insidious.

As a PhD student in academia, you’re often expected to maintain high productivity and engage deeply in your research activities. However, this intense focus can lead to isolation, a key factor contributing to depression and anxiety among doctoral students.

Changes in Emotional And Mental State

You might start noticing changes in your emotional and mental state. Feelings of imposter syndrome, where you constantly doubt your abilities despite evident successes, become frequent.

This is especially true in competitive environments like the Ivy League universities, where the bar is set high. These feelings are often exacerbated by the lack of positive reinforcement from mentors, making you feel like you don’t quite belong, no matter how hard you work.

Lack Of Pleasure From Previously Enjoyable Activities

In doctoral programs, the stressor of overwork is common, but when it leads to a consistent lack of interest or pleasure in activities you once enjoyed, it’s a red flag. This decline in enjoyment extends beyond one’s research and can pervade all aspects of life.

The high rates of depression among PhD students are alarming, yet many continue to suffer in silence, afraid to ask for help or reveal their depression due to the stigma associated with mental health issues in academia.

Losing Social Connections

Another sign is the deterioration of social connections. Graduate student mental health is significantly affected by social support and isolation.

You may find yourself withdrawing from friends and activities, preferring the solitude that ironically feeds into your sense of isolation.

Changes In Appetite And Weight

Changes in appetite and weight can be a significant indicator of depression. As they navigate the demanding PhD study, students might experience fluctuations in their eating habits.

Some may find themselves overeating as a coping mechanism, leading to weight gain. Others might lose their appetite altogether, resulting in noticeable weight loss.

These changes are not just about food; they reflect deeper emotional and mental states.

Such shifts in appetite and weight, especially if sudden or severe, warrant attention as they may signal underlying depression, a common issue in the high-stress environment of PhD studies.

Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms

PhD students grappling with depression often feel immense pressure to excel academically while battling isolation and imposter syndrome. Lacking adequate mental health support, some turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms like substance abuse. These may include:

- Overeating,

- And many more.

These provide temporary relief from overwhelming stress and emotional turmoil. However, such methods can exacerbate their mental health issues, creating a vicious cycle of dependency and further detachment from healthier coping strategies and support systems.

It’s essential for PhD students experiencing depression to recognise these signs and seek professional help. Resources like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are very helpful in this regard.

Suicidal Thoughts Or Attempts

Suicidal thoughts or attempts may sound extreme, but they can happen in PhD studies. This is because of the high-pressure environment of PhD studies.

Doctoral students, often grappling with intense academic demands, social isolation, and imposter syndrome, can be susceptible to severe mental health crises.

When the burden becomes unbearable, some may experience thoughts of self-harm or suicide as a way to escape their distress. These thoughts are a stark indicator of deep psychological distress and should never be ignored.

It’s crucial for academic institutions and support networks to provide robust mental health resources and create an environment where students feel safe to seek help and discuss their struggles openly.

How To Prevent From Depression During And After Ph.D?

A PhD student’s experience is often marked by high rates of depression, a concern echoed in studies from universities like the University of California and Arizona State University. If you are embarking on a PhD journey, make sure you are aware of the issue, and develop strategies to cope with the stress, so you do not end up with depression.

Engage With Activities Outside Academia

One effective strategy is engaging in activities outside academia. Diverse interests serve as a lifeline, breaking the monotony and stress of grad school. Some activities you can consider include:

- Social gatherings.

These activities provide a crucial balance. For instance, some students highlighted the positive impact of adopting a pet, which not only offered companionship but also a reason to step outside and engage with the world.

Seek A Supportive Mentor

The role of a supportive mentor cannot be overstated. A mentor who adopts a ‘yes and’ approach rather than being overly critical can significantly boost a doctoral researcher’s morale.

This positive reinforcement fosters a healthier research environment, essential for good mental health.

Stay Active Physically

Physical exercise is another key element. Regular exercise has been shown to help cope with symptoms of moderate to severe depression. It’s a natural stress reliever, improving mood and enhancing overall wellbeing. Any physical workout can work here, including:

- Brisk walking

- Swimming, or

- Gym sessions.

Seek Positive Environment

Importantly, the graduate program environment plays a critical role. Creating a community where students feel comfortable to reveal their depression or seek help is vital.

Whether it’s through formal support groups or informal peer networks, building a sense of belonging and understanding can mitigate feelings of isolation and imposter syndrome.

This may be important, especially in the earlier stage when you look and apply to universities study PhD . When possible, talk to past students and see how are the environment, and how supportive the university is.

Choose the right university with the right support ensures you keep depression at bay, and graduate on time too.

Remember You Have The Power

Lastly, acknowledging the power of choice is empowering. Understanding that continuing with a PhD is a choice, not an obligation. If things become too bad, there is always an option to seek a deferment, pause. You can also quit your studies too.

Work on fixing your mental state, and recover from depression first, before deciding again if you want to take on Ph.D studies again. There is no point continuing to push yourself, only to expose yourself to self-harm, and even suicide.

Wrapping Up: PhD Does Not Need To Ruin You

Combating depression during PhD studies requires a holistic approach. Engaging in diverse activities, seeking supportive mentors, staying physically active, choosing positive environments, and recognising one’s power to make choices are all crucial.

These strategies collectively contribute to a healthier mental state, reducing the risk of depression. Remember, prioritising your mental well-being is just as important as academic success. This helps to ensure you having a more fulfilling and sustainable journey through your PhD studies.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

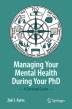

Setting the Scene: Understanding the PhD Mental Health Crisis

- First Online: 15 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Zoë J. Ayres 2

9172 Accesses

This chapter deep-dives into research that has explored the so-called “PhD mental health crisis” looking at both statistics and common stressors that PhD students may face during their studies, as well as the possible causes for increased incidences of mood disorders in the PhD population.

(Trigger Warnings: suicidal ideation, suicide, self-harm, anxiety, depression, discrimination)

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Highly educated was deemed to be having successfully completed an educational program of 3–5 years outside of the university setting or having a bachelors or master’s degree.

Note that the 2019 survey was the first time that the survey was offered in four additional languages including Chinese, Spanish, French and Portuguese which may have impact on the results.

If you are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or self-harming, there is a range of support available to you, detailed in the online resources accompanying this book.

You will note I have placed “failed” in quotations. This is because I do not believe that choosing to leave a PhD is failure, it is just a different decision. We will discuss this in detail later on in the book.

Many of these studies use IQ as a measure of intelligence, though there is evidence to suggest that IQ tests have biases, and a person can improve their IQ results over time with practice, suggesting it is not a true measure of intelligence.

For me, it was really feeling like a fraud (struggling from the impostor phenomenon that really fuelled my struggles during my PhD. I used errors made in the lab as “proof” in my own head that I did not deserve to be doing a PhD.

Satinsky EN, Kimura T, Kiang MV, Abebe R, Cunningham S, Lee H, Lin X, Liu CH, Rudan I, Sen S, Tomlinson M, Yaver M, Tsai AC (2021) Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph.D. students. Sci Rep 11(1):14370

Article Google Scholar

Evans TM, Bira L, Gastelum JB, Weiss LT, Vanderford NL (2018) Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat Biotechnol 36(3):282–284

Bertolote J (2008) The roots of the concept of mental health. World Psychiatry 7(2):113–116

Google Scholar

Crook S (2020) Historicising the “crisis” in undergraduate mental health: British universities and student mental illness, 1944–1968. J Hist Med Allied Sci 75(2):193–220

Andersen J, Altwies E, Bossewitch J, Brown C, Cole K, Davidow S, DuBrul SA, Friedland-Kays E, Fontaine G, Hall W, Hansen C, Lewis B, Mitchell-Brody M, McNamara J, Nikkel G, Sadler P, Stark D, Utah A, Vidal A, Weber CL (2017) Mad resistance/mad alternatives: democratizing mental health care. In: Community mental health. Routledge, Abingdon

The Graduate Assembly (2014) Graduate student happiness & well-being report. University of California, Berkeley, CA

Levecque K, Anseel F, De Beuckelaer A, Van der Heyden J, Gisle L (2017) Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Res Policy 46(4):868–879

Guthrie S, Lichten C, Belle J, Ball S, Knack A, Hofman J (2017) Understanding mental health in the research environment. RAND Europe, Cambridge, UK

Smith E, Brooks Z (2015) Graduate student mental health. University of Arizona Tucson, AZ

Williams S (2019) Postgraduate research experience survey 2019. Advance HE, York

Woolston C (2019) PhDs: the tortuous truth. Nature 575(7782):403–407

Byrom N (2020) The challenges of lockdown for early-career researchers. eLife:9e59634

Garcia-Williams AG, Moffitt L, Kaslow NJ (2014) Mental health and suicidal behavior among graduate students. Acad Psychiatry 38:554–560

ten Have M, De Graaf R, Van Dorsselaer S, Verdurmen J, Van’t Land H, Vollebergh W, Beekman A (2009) Incidence and course of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the general population. Can J Psychiatry 54(12):824–833

DiscoverPhDs (2017) PhD failure rate – a study of 26,076 PhD candidates. https://www.discoverphds.com/advice/doing/phd-failure-rate . Accessed 3 Mar 2022

Young SN, Vanwye WR, Schafer MA, Robertson TA, Poore AV (2019) Factors affecting PhD student success. Int J Exerc Sci 12(1):34–45

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Karpinski RI, Kolb AMK, Tetreault NA, Borowski TB (2018) High intelligence: a risk factor for psychological and physiological overexcitabilities. Intelligence: 668–623

Givens JL, Tjia J (2002) Depressed medical students’ use of mental health services and barriers to use. Acad Med 77(9):918–921

Moran H, Karlin L, Lauchlan E, Rappaport SJ, Bleasdale B, Wild L, Dorr J (2020) Understanding research culture: what researchers think about the culture they work in. Wellcome Trust, London, UK

Moss SE, Mahmoudi M (2021) STEM the bullying: an empirical investigation of abusive supervision in academic science. EClinicalMedicine 40:101121

Devos C, Boudrenghien G, Van der Linden N, Azzi A, Frenay M, Galand B, Klein O (2017) Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: a matter of sense, progress and distress. Eur J Psychol Educ 32(1):61–77

Limas JC, Corcoran LC, Baker AN, Cartaya AE, Ayres ZJ (2022) The impact of research culture on mental health & diversity in STEM. Chemistry s(9):e202102957

Cerejo C, Awati M, Hayward A (2020) Joy and stress triggers: a global survey on mental health among researchers. CACTUS Foundation, Solapur

Berhe AA, Barnes RT, Hastings MG, Mattheis A, Schneider B, Williams BM, Marín-Spiotta E (2022) Scientists from historically excluded groups face a hostile obstacle course. Nat Geosci 15(1):2–4

Bhopal K (2015) The experiences of black and minority ethnic academics: a comparative study of the unequal academy. Routledge, Abingdon

Book Google Scholar

Woolston C (2018) Feeling overwhelmed by academia? You are not alone. Nature 557(7706):129–131

Moore S, Neylon C, Eve MP, Paul O’Donnell D, Pattinson D (2017) “Excellence R Us”: university research and the fetishisation of excellence. Palgrave Commun 3:16105

Russo G (2013) Education: financial burden. Nature 501(7468):579–581

Khoo S (2021) How Canada short-changes its graduate students and postdocs. https://www.universityaffairs.ca/opinion/in-my-opinion/how-canada-short-changes-its-graduate-students-and-postdocs/ . Accessed 4 Mar 2022

UK Council for International Student Affairs (2022) Student work. https://www.ukcisa.org.uk/Information%2D%2DAdvice/Working/Student-work . Accessed 2 Jun 2022

Kearns H, Gardiner M, Marchall K, Banytis F (2006) The PhD experience: what they didn’t tell you at induction. ThinkWell, Glenelg North

Jackman PC, Jacobs L, Hawkins RM, Sisson K (2021) Mental health and psychological wellbeing in the early stages of doctoral study: a systematic review. Eur J High Educ. 12(3):293–313

Clance PR, Imes SA (1978) The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother Theory Res Pract 15(3):241–247

De Rond M, Miller AN (2005) Publish or perish: bane or boon of academic life? J Manage Inq 14(4):321–329

Miller AN, Taylor SG, Bedeian AG (2011) Publish or perish: academic life as management faculty live it. Career Development International. Emerald, Bingley, UK

Hazell CM, Chapman L, Valeix SF, Roberts P, Niven JE, Berry C (2020) Understanding the mental health of doctoral researchers: a mixed methods systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Syst Rev 9(1):197

Lim MH, Rodebaugh TL, Zyphur MJ, Gleeson JFM (2016) Loneliness over time: the crucial role of social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol 125(5):620–630

Yu B, Steptoe A, Niu K, Ku P, Chen L (2018) Prospective associations of social isolation and loneliness with poor sleep quality in older adults. Qual Life Res 27(3):683–691

Casey C, Harvey O, Taylor J, Knight F, Trenoweth S (2022) Exploring the wellbeing and resilience of postgraduate researchers. J Further High Educ 46(6):850–867

Zapf MK (1991) Cross-cultural transitions and wellness: dealing with culture shock. Int J Adv Couns 14(2):105–119

Sokratous S, Merkouris A, Middleton N, Karanikola M (2013) The association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms among Cypriot university students: a cross-sectional descriptive correlational study. BMC Public Health 13(1):1121

Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Kippen S, Liamputtong P (2007) Doing sensitive research: what challenges do qualitative researchers face? Qual Res 7(3):327–353

Boynton P (2020) Being Well in Academia: Ways to Feel Stronger, Safer and More Connected. Routledge, Abingdon

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Zoë J. Ayres

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ayres, Z.J. (2022). Setting the Scene: Understanding the PhD Mental Health Crisis. In: Managing your Mental Health during your PhD. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14194-2_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14194-2_3

Published : 15 September 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-14193-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-14194-2

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health

PhDs are renowned for being stressful and when you add a global pandemic into the mix it’s no surprise that many students are struggling with their mental health. Unfortunately this can often lead to PhD fatigue which may eventually lead to burnout.

In this post we’ll explore what academic burnout is and how it comes about, then discuss some tips I picked up for managing mental health during my own PhD.

Please note that I am by no means an expert in this area. I’ve worked in seven different labs before, during and after my PhD so I have a fair idea of research stress but even so, I don’t have all the answers.

If you’re feeling burnt out or depressed and finding the pressure too much, please reach out to friends and family or give the Samaritans a call to talk things through.

Note – This post, and its follow on about maintaining PhD motivation were inspired by a reader who asked for recommendations on dealing with PhD fatigue. I love hearing from all of you, so if you have any ideas for topics which you, or others, could find useful please do let me know either in the comments section below or by getting in contact . Or just pop me a message to say hi. 🙂

This post is part of my PhD mindset series, you can check out the full series below:

- PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health (this part!)

- PhD Motivation: How to Stay Driven From Cover Letter to Completion

- How to Stop Procrastinating and Start Studying

What is PhD Burnout?

Whenever I’ve gone anywhere near social media relating to PhDs I see overwhelmed PhD students who are some combination of overwhelmed, de-energised or depressed.

Specifically I often see Americans talking about the importance of talking through their PhD difficulties with a therapist, which I find a little alarming. It’s great to seek help but even better to avoid the need in the first place.

Sadly, none of this is unusual. As this survey shows, depression is common for PhD students and of note: at higher levels than for working professionals.

All of these feelings can be connected to academic burnout.

The World Health Organisation classifies burnout as a syndrome with symptoms of:

– Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; – Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; – Reduced professional efficacy. Symptoms of burnout as classified by the WHO. Source .

This often leads to students falling completely out of love with the topic they decided to spend years of their life researching!

The pandemic has added extra pressures and constraints which can make it even more difficult to have a well balanced and positive PhD experience. Therefore it is more important than ever to take care of yourself, so that not only can you continue to make progress in your project but also ensure you stay healthy.

What are the Stages of Burnout?

Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North developed a 12 stage model of burnout. The following graphic by The Present Psychologist does a great job at conveying each of these.

I don’t know about you, but I can personally identify with several of the stages and it’s scary to see how they can potentially lead down a path to complete mental and physical burnout. I also think it’s interesting that neglecting needs (stage 3) happens so early on. If you check in with yourself regularly you can hopefully halt your burnout journey at that point.

PhDs can be tough but burnout isn’t an inevitability. Here are a few suggestions for how you can look after your mental health and avoid academic burnout.

Overcoming PhD Burnout

Manage your energy levels, maintaining energy levels day to day.

- Eat well and eat regularly. Try to avoid nutritionless high sugar foods which can play havoc with your energy levels. Instead aim for low GI food . Maybe I’m just getting old but I really do recommend eating some fruit and veg. My favourite book of 2021, How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reduce Disease , is well worth a read. Not a fan of veggies? Either disguise them or at least eat some fruit such as apples and bananas. Sliced apple with some peanut butter is a delicious and nutritious low GI snack. Check out my series of posts on cooking nutritious meals on a budget.

- Get enough sleep. It doesn’t take PhD-level research to realise that you need to rest properly if you want to avoid becoming exhausted! How much sleep someone needs to feel well-rested varies person to person, so I won’t prescribe that you get a specific amount, but 6-9 hours is the range typically recommended. Personally, I take getting enough sleep very seriously and try to get a minimum of 8 hours.

A side note on caffeine consumption: Do PhD students need caffeine to survive?

In a word, no!

Although a culture of caffeine consumption goes hand in hand with intense work, PhD students certainly don’t need caffeine to survive. How do I know? I didn’t have any at all during my own PhD. In fact, I wrote a whole post about it .

By all means consume as much caffeine as you want, just know that it doesn’t have to be a prerequisite for successfully completing a PhD.

Maintaining energy throughout your whole PhD

- Pace yourself. As I mention later in the post I strongly recommend treating your PhD like a normal full-time job. This means only working 40 hours per week, Monday to Friday. Doing so could help realign your stress, anxiety and depression levels with comparatively less-depressed professional workers . There will of course be times when this isn’t possible and you’ll need to work longer hours to make a certain deadline. But working long hours should not be the norm. It’s good to try and balance the workload as best you can across the whole of your PhD. For instance, I often encourage people to start writing papers earlier than they think as these can later become chapters in your thesis. It’s things like this that can help you avoid excess stress in your final year.

- Take time off to recharge. All work and no play makes for an exhausted PhD student! Make the most of opportunities to get involved with extracurricular activities (often at a discount!). I wrote a whole post about making the most of opportunities during your PhD . PhD students should have time for a social life, again I’ve written about that . Also give yourself permission to take time-off day to day for self care, whether that’s to go for a walk in nature, meet friends or binge-watch a show on Netflix. Even within a single working day I often find I’m far more efficient when I break up my work into chunks and allow myself to take time off in-between. This is also a good way to avoid procrastination!

Reduce Stress and Anxiety

During your PhD there will inevitably be times of stress. Your experiments may not be going as planned, deadlines may be coming up fast or you may find yourself pushed too far outside of your comfort zone. But if you manage your response well you’ll hopefully be able to avoid PhD burnout. I’ll say it again: stress does not need to lead to burnout!

Everyone is unique in terms of what works for them so I’d recommend writing down a list of what you find helpful when you feel stressed, anxious or sad and then you can refer to it when you next experience that feeling.

I’ve created a mental health reminders print-out to refer to when times get tough. It’s available now in the resources library (subscribe for free to get the password!).

Below are a few general suggestions to avoid PhD burnout which work for me and you may find helpful.

- Exercise. When you’re feeling down it can be tough to motivate yourself to go and exercise but I always feel much better for it afterwards. When we exercise it helps our body to adapt at dealing with stress, so getting into a good habit can work wonders for both your mental and physical health. Why not see if your uni has any unusual sports or activities you could try? I tried scuba diving and surfing while at Imperial! But remember, exercise doesn’t need to be difficult. It could just involve going for a walk around the block at lunch or taking the stairs rather than the lift.

- Cook / Bake. I appreciate that for many people cooking can be anything but relaxing, so if you don’t enjoy the pressure of cooking an actual meal perhaps give baking a go. Personally I really enjoy putting a podcast on and making food. Pinterest and Youtube can be great visual places to find new recipes.

- Let your mind relax. Switching off is a skill and I’ve found meditation a great way to help clear my mind. It’s amazing how noticeably different I can feel afterwards, having not previously been aware of how many thoughts were buzzing around! Yoga can also be another good way to relax and be present in the moment. My partner and I have been working our way through 30 Days of Yoga with Adriene on Youtube and I’d recommend it as a good way to ease yourself in. As well as being great for your mind, yoga also ticks the box for exercise!

- Read a book. I’ve previously written about the benefits of reading fiction * and I still believe it’s one of the best ways to relax. Reading allows you to immerse yourself in a different world and it’s a great way to entertain yourself during a commute.

* Wondering how I got something published in Science ? Read my guide here .

Talk It Through

- Meet with your supervisor. Don’t suffer in silence, if you’re finding yourself struggling or burned out raise this with your supervisor and they should be able to work with you to find ways to reduce the pressure. This may involve you taking some time off, delegating some of your workload, suggesting an alternative course of action or signposting you to services your university offers.

Also remember that facing PhD-related challenges can be common. I wrote a whole post about mine in case you want to cheer yourself up! We can’t control everything we encounter, but we can control our response.

A free self-care checklist is also now available in the resources library , providing ideas to stay healthy and avoid PhD burnout.

Top Tips for Avoiding PhD Burnout

On top of everything we’ve covered in the sections above, here are a few overarching tips which I think could help you to avoid PhD burnout:

- Work sensible hours . You shouldn’t feel under pressure from your supervisor or anyone else to be pulling crazy hours on a regular basis. Even if you adore your project it isn’t healthy to be forfeiting other aspects of your life such as food, sleep and friends. As a starting point I suggest treating your PhD as a 9-5 job. About a year into my PhD I shared how many hours I was working .

- Reduce your use of social media. If you feel like social media could be having a negative impact on your mental health, why not try having a break from it?

- Do things outside of your PhD . Bonus points if this includes spending time outdoors, getting exercise or spending time with friends. Basically, make sure the PhD isn’t the only thing occupying both your mental and physical ife.

- Regularly check in on how you’re feeling. If you wait until you’re truly burnt out before seeking help, it is likely to take you a long time to recover and you may even feel that dropping out is your only option. While that can be a completely valid choice I would strongly suggest to check in with yourself on a regular basis and speak to someone early on (be that your supervisor, or a friend or family member) if you find yourself struggling.

I really hope that this post has been useful for you. Nothing is more important than your mental health and PhD burnout can really disrupt that. If you’ve got any comments or suggestions which you think other PhD scholars could find useful please feel free to share them in the comments section below.

You can subscribe for more content here:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

The Five Most Powerful Lessons I Learned During My PhD

8th August 2024 8th August 2024

Minor Corrections: How To Make Them and Succeed With Your PhD Thesis

2nd June 2024 2nd June 2024

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 4th August 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

Cassie M Hazell

January 12th, 2022, is doing a phd bad for your mental health.

9 comments | 77 shares

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Poor mental health amongst PhD researchers is increasingly being recognised as an issue within higher education institutions. However, there continues to be unanswered questions relating to the propensity and causality of poor mental health amongst PhD researchers. Reporting on a new comparative survey of PhD researchers and their peers from different professions, Dr Cassie M Hazell and Dr Clio Berry find that PhD researchers are particularly vulnerable to poor mental health compared to their peers. Arguing against an inherent and individualised link between PhD research and mental health, they suggest institutions have a significant role to play in reviewing cultures and working environments that contribute to the risk of poor mental health.

Evidence has been growing in recent years that mental health difficulties are common amongst PhD students . These studies understandably have caused concern in academic circles about the welfare of our future researchers and the potential toxicity of academia as a whole. Each of these studies has made an important contribution to the field, but there are some key questions that have thus far been left unanswered:

- Is this an issue limited to certain academic communities or countries?

- Do these findings reflect a PhD-specific issue or reflect the mental health consequences of being in a graduate-level occupation?

- Are the mental health difficulties reported amongst PhD students clinically meaningful?

We attempted to answer these questions as part of our Understanding the mental health of DOCtoral researchers (U-DOC) survey. To do this we surveyed more than 3,300 PhD students studying in the UK and a control group of more than 1,200 matched working professionals about their mental health. In our most recent paper , we compared the presence and severity of mental health symptoms between these two groups. Using the same measures as are used in the NHS to assess symptoms of depression and anxiety, we found that PhD students were more likely to meet criteria for a depression and/or anxiety diagnosis and have more severe symptoms overall. We found no difference between these groups in terms of their overall suicidality. However, survey responses corresponding to past suicidal thinking and behaviour, and future suicide intent were generally highly rated in both groups.

42% of PhD students reported that they believed having a mental health problem during your PhD is the norm

We also asked PhD students about their perceptions and lived experience of mental health. Sadly, 42% of PhD students reported that they believed having a mental health problem during your PhD is the norm. We also found similar numbers saying they have considered taking a break from their studies for mental health reasons, with 14% actually taking a mental health-related break. Finally, 35% of PhD students have considered ending their studies altogether because of their mental health.

We were able to challenge the working theory that the reason for our findings is that those with mental health difficulties are more likely to continue their studies at university to the doctoral level. In other words, the idea that doing a PhD doesn’t in any way cause mental health problems and these results are instead the product of pre-existing conditions. Contrary to this notion, we found that PhD students were not more likely than working professionals to report previously diagnosed mental health problems, and if anything, when they had mental health problems, these started later in life than for the working professionals. Additionally, we found that our results regarding current depression and anxiety symptoms remained even after controlling for a history of mental health difficulties.

The findings from this paper and our other work on the U-DOC project has highlighted that PhD students seem to be particularly vulnerable to experiencing mental health problems. We found several factors to be key predictors of this poor mental health ; specifically not having interests and relationships outside of PhD studies, students’ perfectionism, impostor thoughts, their supervisory relationship, isolation, financial insecurity and the impact of stressors outside of the PhD .

the current infrastructure, systems and practices in most academic institutions, and in the wider sector, are increasing PhD students’ risk of mental health problems and undermining the potential joy of pursuing meaningful and exciting research

So, does this mean that doing a PhD is bad for your mental health? Not necessarily. There are several aspects of the PhD process that are conducive to mental health difficulties, but it is absolutely not inevitable. Our research (and our own experiences!) suggests that doing a PhD can be an incredibly positive experience that is intellectually stimulating, personally satisfying, and gives a sense of meaning and purpose. We instead believe a more appropriate conclusion to draw from our work is that the current infrastructure, systems and practices in most academic institutions, and in the wider sector, are increasing PhD students’ risk of mental health problems and undermining the potential joy of pursuing meaningful and exciting research.

Reducing this issue to the common rhetoric that “PhD studies cause mental health problems” is problematic for several reasons: Firstly, it ignores the many interacting moving parts at work here that variably increase and reduce risk of poor mental health across people, time, and place. Secondly, it does not acknowledge the pockets of incredibly good practice in the sector we can learn from and implement more widely. Finally, it reinforces the notion that poor mental health is the norm for PhD students which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy- and itself ignores the joy of pursuing a thesis in something potentially so personally meaningful. Nonetheless, a significant paradigm shift is needed in academia to reduce the current environmental toxins so that studying for a PhD can be a truly enjoyable and fulfilling process for all.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Geralt via Pixabay.

About the author

Dr Cassie M Hazell (she/her) is a lecturer in Social Sciences at the University of Westminster. Her research is on around mental health, with a special interest in implementation science. She is the co-founder of the international Early Career Hallucinations Research (ECHR) group and Early-Mid Career representative on the Research Council at her institution.

Dr Clio Berry is a Senior Lecturer in Healthcare Evaluation and Improvement in the Brighton and Sussex Medical School. She is interested in the application of positive and social psychology approaches to mental health problems and social outcomes for young people and students. Her work spans identification of risk and resilience factors in predicting mental health and social problems and their outcomes, and in the development and evaluation of clinical and non-clinical interventions.

- Pingback: Is doing a PhD bad for your mental health? | Thinking about Digital Publishing

My own experience of doing a PhD (loneliness, the lack of routine, imposter syndrome) has led to my discouraging my daughter, who has a history of mental health issues, from considering it at the moment, despite her having the academic aptitude and even a topic. I would hazard a guess that the problems are worse in the humanities than in the applied sciences, where most PhD students tend to work as part of research teams and be well supported in more structured environments.

- Pingback: What can universities do to support the well-being and mental health of postgraduate researchers? | Impact of Social Sciences

Fascinating research… I had a terrible PhD, but most of the mental health issues arose after the fact. If you ever conducted another survey it would be interesting to include those who had recently finished a PhD.

Looking at your follow up BJPsyche paper, I noticed you haven’t gone into the correlation between subject and mental health. I’d be interested to know how sciences vs humanities compared.

I see that your work is very restrained in discussing the causes of mental health issues, and I’m sure you have plenty of hypothesis. In my experience, a key factor is that there is no mechanism to hold supervisors to account for the quality of their supervision. (Linking to the point above, I believe in the sciences supervisors with poor outcomes do suffer repetitional damage – not so in the humanities.)

I’d also add that the UK’s Viva system, which I believe is unique globally, is a recipe for disaster – years of work evaluated over the course of just a couple of hours by examiners who, again, are not held accountable in any way.

I wrote my experience up here: https://medium.com/the-faculty/i-had-a-brutal-phd-viva-followed-by-two-years-of-corrections-here-is-what-i-learned-about-vivas-5e81175aa5d

- Pingback: The benefits of getting involved with the LSESU as a PhD student | Students@LSE

- Pingback: “Am I ready for a PhD?” - The Undercover Academic

- Pingback: #AcWriMo & online writing communities for off-campus PGRs – UoB PGR Development

- Pingback: Psychische Herausforderungen während der juristischen Promotion › JuWissBlog

- Pingback: What To Expect When You’re PhDing - Völkerrechtsblog

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

What can universities do to support the well-being and mental health of postgraduate researchers? February 1st, 2022

Related posts.

Is peer review bad for your mental health?

April 19th, 2018.

Book Review: Being Well in Academia: Ways to Feel Stronger, Safer and More Connected by Petra Boynton

February 27th, 2021.

Mental health risks in research training can no longer be ignored

June 25th, 2018.

The neurotic academic: how anxiety fuels casualised academic work

April 17th, 2018.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychol Res Behav Manag

Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among doctoral students: the mediating effect of mentoring relationships on the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety

1 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China, gro.latipsoh-js@hyoahz

2 Department of Library and Medical Information, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

3 Department of Social Medicine, School of Public Health, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

4 Key Laboratory of Immunodermatology, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

5 Department of Dermatology, First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Weiqiu Wang

Shanshan jia.

6 Key Laboratory of Health Ministry for Congenital Malformation, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Deshu Shang

7 Department of Developmental Cell Biology, Key Laboratory of Medical Cell Biology, Ministry of Education, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

8 Department of Developmental Cell Biology, Cell Biology Division, Key Laboratory of Cell Biology, Ministry of Health, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Yangguang Shao

9 Department of Cell Biology, Key Laboratory of Cell Biology, National Health Commission of the PRC, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

10 Department of Cell Biology, Key Laboratory of Medical Cell Biology, Ministry of Education, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Xinwang Zhu

11 Department of Nephrology, First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Shengnan Yan

12 Graduate Division, School of Public Health, China Medical University, Shenyang, China

Yuhong Zhao

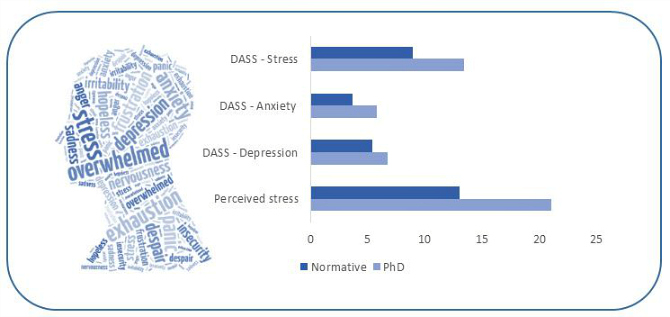

Although the mental health status of doctoral students deserves attention, few scholars have paid attention to factors related to their mental health problems. We aimed to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in doctoral students and examine possible associated factors. We further aimed to assess whether mentoring relationships mediate the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 325 doctoral students in a medical university. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 scale were used to assess depression and anxiety. The Research Self-Efficacy Scale was used to measure perceived ability to fulfill various research-related activities. The Advisory Working Alliance Inventory-student version was used to assess mentoring relationships. Linear hierarchical regression analyses were performed to determine if any factors were significantly associated with depression and anxiety. Asymptotic and resampling methods were used to examine whether mentoring played a mediating role.

Approximately 23.7% of participants showed signs of depression, and 20.0% showed signs of anxiety. Grade in school was associated with the degree of depression. The frequency of meeting with a mentor, difficulty in doctoral article publication, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program was associated with both the level of depression and anxiety. Moreover, research self-efficacy and mentoring relationships had negative relationships with levels of depression and anxiety. We also found that mentoring relationships mediated the correlation between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

The findings suggest that educational experts should pay close attention to the mental health of doctoral students. Active strategies and interventions that promote research self-efficacy and mentoring relationships might be beneficial in preventing or reducing depression and anxiety.

Introduction

Recently, the mental health status of students has become a hot topic in public health, higher education, and research policy. 1 – 3 Depression and anxiety are two of the most common psychological disorders. Researchers have reported depression and anxiety among students in several countries and in numerous disciplines, such as counseling, medicine, law, and psychology. 4 – 14 Depression is defined as a mood that includes a feeling of hopelessness, helplessness, or worthlessness. 2 Anxiety is an emotion characterized by unpleasant inner feelings, which is accompanied by caution, complaints, meditation, nervousness, and worry. 5 Depression and anxiety can affect a person’s behavior, academic performance, and general health, as well as quality of sleep, eating habits, and well-being. 8 In addition, it has been confirmed that depression and psychological distress influence suicidal ideation in undergraduate and graduate students. 15 – 18 However, mental health among doctoral students has been relatively ignored by researchers and educational experts. It has only been in the last 2 years that this topic has begun to attract more and more attention.

A doctoral student’s school career is full of hardships and happiness. Doctoral students frequently feel a sense of urgency, worry, and stress as they work toward their doctoral degrees. In addition to financial support and future employment, doctoral students worry about writing a thesis, publishing papers, and handling relationships with advisors. In recent years, a few scholars have explored the prevalence of mental health problems among PhD students. 3 , 12 , 19 – 21 In 2013, Levecquea et al investigated PhD students in Belgium. They concluded that approximately half the PhD students in Flanders had at least two symptoms, and 32% reported at least four symptoms on the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12). 3 According to a 2015 survey at the University of California, approximately half the PhD students in science and engineering were depressed. 12 Springer Nature did a survey of PhD students in 2017, and confirmed that 12% reported seeking help for anxiety or depression caused by PhD studies. 20 A 2018 survey of graduate students via social media revealed that 41% of graduate students scored in the moderate–severe range for anxiety and 39% scored in the moderate–severe range for depression. 21 Doctoral students with mental health issues are more likely to drop out of PhD programs. 22 The high attrition rate in PhD programs caused by the dropout of PhD students with psychological illness is damaging to research institutions and the whole research industry. 23 However, there have been few reports on the mental health of doctoral students in medical universities.

Students in medical schools engage in rigorous medical training. 24 , 25 Previous studies have demonstrated that medical students have more pressure, more burnout, and a greater prevalence of mental health disorders than the general population or students in other disciplines. 26 – 31 Medical training varies considerably by discipline, institution, and country. US and Canadian medical students enter medical education systems after they receive a bachelor’s degree. 32 , 33 In China, students can enter medical schools after graduating from high school (similarly to the UK and France). In general, there is an entrance examination required for students with a master’s degree who would like to study for doctoral degrees. Doctoral students need another 3 years to earn a doctoral degree, allowing for an extension of 3 years. Master’s degree candidates in grade two have the choice to apply for a master–doctor combined-training program (a total of 5 years for a doctoral degree, allowing an extension of 3 years). Doctoral students can be either full-time or part-time students. Part-time doctoral students are those who are studying doctoral courses while working in clinical settings or having another job. As such, for clinical doctoral students, some are still fully engaged in clinical work while earning their doctoral degree, whereas others are temporarily away from clinical work to concentrate on the doctoral program research. It is a bit too much to expect clinical doctoral students to do clinical work and research at the same time throughout their doctoral training.

Sociodemographic variables, such as age, sex, and marital status, have been reported to be associated with the mental health of postgraduate students. 8 , 10 However, sex differences in depression among medical students have also yielded mixed results, showing either no difference or high prevalence among female or male medical students. 27 , 29 , 33 Further exploration among doctoral students is still needed. The execution phase during doctoral study has been shown to be prone to mental health problems among doctoral students. 3 Additionally, researchers have suggested that work–life balance is the key factor related to the mental health problems of postgraduate students. 3 , 21 Employed doctoral students work full time or part time while they are studying for their doctoral degree. In this case, conflict concerns not only balancing family and work but also completing the doctoral program itself. Few scholars have focused on the conflicts among family, work, and a doctoral program. Getting married and raising children also puts a strain on doctoral students. Doing experiments, writing a doctoral thesis, and publishing doctoral qualification papers requires considerable time, energy, and financial resources.

Mentorship effectiveness and mentoring functions are thought to be vital to graduate-student programs. 34 , 35 Mentors have a great responsibility to guide their doctoral students through the doctoral program. Advisor mentoring affects student-research self-efficacy, productivity, and development as a scientist. 36 – 38 Recently, a study explored the effect of a supervisor’s leadership style on the mental health of graduate students. 3 Nearly half the doctoral students who withdrew from the doctoral program reported experiencing insufficient supervision, highlighting the fact that good supervision was important for completing the doctoral program. 39 , 40 A survey in 2018 indicated that a weak relationship with a mentor is a common characteristic of most graduate students who experience anxiety and/or depression. 21

Research self-efficacy refers to the individual’s confidence in the successful completion of various aspects of the scientific research process, 41 such as data collection, performing experimental procedures, and writing papers. 42 Studies have evaluated the important role of research self-efficacy in research training. Self-efficacy is a factor that affects how much effort students spend on research tasks and how long they persist when they experience difficulties. 43 Some universities in the US have used research self-efficacy to evaluate the effects of degree programs on graduate research ability. 44 A study has shown that research self-efficacy can predict the research interest and knowledge of doctoral students. 45 Some researchers have reported that high research self-efficacy is correlated with future research involvement and research productivity. 46 , 47 It was suggested that research self-efficacy could play a mediating role between the research-training environment and scientific research output. Furthermore, the relationship between stress and depression has been shown to be mediated by stress management self-efficacy. 48 Interestingly, the length of student–advisor relationships has been reported to be significantly correlated with student research self-efficacy. 36 Moreover, among agricultural students, research self-efficacy has been found to be negatively associated with research anxiety. 49 Therefore, the higher the students’ research self-efficacy, the lower their research anxiety. However, it is not clear whether scientific research self-efficacy is correlated with levels of generalized anxiety.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety among doctoral students in a medical university in China, determine factors that are associated with depression and anxiety, determine whether mentoring relationships and research self-efficacy are associated with depression and anxiety, and test whether mentoring relationships mediate the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety.

Participants

We recruited doctoral students from October to November 2017 using a combination of snowball sampling and stratified sampling from five medical schools and four affiliated clinical hospitals at a medical university in northeast China. This university has the authority to grant doctoral degrees in six major disciplines (basic medicine, clinical medicine, biology, stomatology, public health and preventive medicine, and nursing), including 49 different majors. Our inclusion criteria were still studying at the medical university, had not yet earned a PhD degree, enrollment in a successive postgraduate and doctoral program, and no history of depression or anxiety before entering medical school. A total of 437 doctoral students (218 male, 219 female) were enrolled. This study received approval from the Committee for Human Trials of China Medical University (CMU17/375/R). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before they entered the experiment. All questionnaires were filled out anonymously and confidentially.

Sociodemographic and doctoral factors

Doctoral students’ sociodemographic status included age, sex, marital status, children, and income. In addition, we selected some doctoral characteristics that might affect the mental health of doctoral students. We asked participants whether they had been employed before doctoral enrollment. Clinical doctoral students refers to students who were doing clinical work while earning their doctoral degree. Grade was measured assigned to one of four categories (1, first year; 2, second year; 3, third year; 4, fourth year or above). Mentors meet with their doctoral students regularly or irregularly. They come together and analyze the latest literature, discuss the research direction or experimental methods, and revise the thesis. Therefore, the frequency of these meetings can reflect the strength of the relationship from a certain quantitative angle. The frequency with which doctoral students met with mentors was measured with one item: “On average, how often do you meet with your advisor? (1, at least once a week; 2, at least once a month; 3, seldom)”. In most medical universities, doctoral students are required to publish at least one academic paper indexed by the Science Citation Index or Social Science Citation Index. Only when this qualification has been reached are doctoral students able to apply for a doctoral degree. The perceived difficulty in publishing a doctoral qualification paper was assessed by one item: “How much effort do you think it takes to publish doctoral qualification papers? (1, a little bit of effort; 2, some effort; 3, a lot of effort). Considering that the total time and energy of doctoral students is limited, we asked the doctoral students, “Do you have difficulty in balancing work, family, and the PhD program? (1, almost no difficulty; 2, some difficulty; 3, great difficulty)”.

Depression questionnaire

We chose the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) 50 to evaluate depression among doctoral students. Each item is measured on a 4-point Likert-like scale (0, not at all; 3, almost every day) based on the frequency of depression symptoms over the last 2 weeks. Total scores range from 0 to 27. A higher PHQ-9 score represents more serious depression (0–4, none–minimal; 5–9, mild; 10–14, moderate; 15–19, moderately severe; 20–27, severe). In general, a diagnosis of depression can only be arrived at after clinical assessment by a mental health professional. With such questionnaires as the PHQ-9, it has been shown that at certain cutoffs there is good correlation with diagnostic interviews. PHQ-9 scores of 10 or above had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depressive disorder. 50 The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 has been used in older people and hospital inpatients, with sound reliability. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-9 scale was 0.918.

Anxiety questionnaire

We used the seven item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) to indicate the degree of anxiety among doctoral students. 51 The GAD-7 contains seven items that are rated on a 4-point Likert-like scale (0, not at all; 3, almost every day). The total score ranges from 0 to 21. A higher GAD-7 score indicates more serious anxiety (0–4, none–minimal; 5–9, mild; 10–14, moderate; 15–21, severe). Using a threshold score of 10, the GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82% for major generalized anxiety disorder. 51 The Chinese version of the GAD-7 has been used in outpatients with satisfactory reliability. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the GAD-7 scale was 0.946.

Mentoring-relationship questionnaire

The 30-item Advisory Working Alliance Inventory-student version (AWAI-S) was used to assess the mentoring relationship from the student’s perspective. 36 This scale is a brief, self-reported measure designed on the basis of the Working Alliance model. Its developer, Schlosser, believed that a favorable supervisory alliance was vital to outcomes. 52 The scale has had good reliability in previous studies. 53 The AWAI-S consists of three domains: rapport (11 items), apprenticeship (14 items), and identification-individuation (5 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). The AWAI-S scale contains 16 reverse-scoring questions. High scores (after reverse scoring) suggest that the advisee has a strong mentoring relationship with the advisor. The internal consistency of AWAI-S scores from previous studies ranged from 0.84 to 0.95 36 , 54 and was 0.95 in this study.

Research Self-Efficacy Scale

The Research Self-Efficacy Scale (RSES) was used to measure the doctoral students’ perceived ability to fulfill various research-related tasks. 55 The RSES comprises 50 items with four subscales: conceptualization (18 items), implementation (19 items), early tasks (5 items), and presenting the results (8 items). Individuals were asked to mark the tasks they perceived they could perform. The strength of each item was rated on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (complete confidence). A total RSES score was calculated, ranging from 75 to 500. A higher score indicates higher self-efficacy. The internal consistency of RSES scores was 0.98 in the present study.

Data analysis

We used SPSS 17.0 for all statistical analyses. We investigated demographic and doctoral characteristics using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-squared for categorical data. Correlations among depression, anxiety, mentoring relationships, and research self-efficacy were examined by Pearson correlation. We performed hierarchical linear regression analysis to explore the association of mentoring relationship and research self-efficacy with depression/anxiety. In this study, depression and anxiety were modeled as dependent variables, RSES as an independent variable, AWAI-S as a mediator, and sociodemographic and doctoral variables as controlled variables. In step 1 of the regression, sociodemographic and doctoral variables were entered as controlled variables. Because linear hierarchical regression analysis requires continuous variables, the grade, frequency of meeting with a mentor, difficulty in publishing a doctoral qualification paper, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program was dummy coded. In step 2 of the regression, research self-efficacy was added. In step 3, the mentoring relationship was added. The asymptotic and resampling method was used to examine mentoring relationship as potential mediator in the association between research self-efficacy and depression/anxiety, based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. 56 A bias-corrected and accelerated (BC a ) 95% CI was used to estimate mediation. If the BC a 95% CI excludes 0, this indicates that the mediation is significant. All statistical tests were two-sided (α=0.05). P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics of respondents

After exclusion of 45 doctoral students who refused to fill out questionnaires, the 392 who completed the questionnaires were included. A total of 67 questionnaires with missing values >10% were deemed invalid. As such, we collected 325 valid responses. The effective response rate was 74.37%. The mean age of the participants was 31.1±5.3 (23–47) years. Of the 325 respondents, 60.3% were female, 50.8% married or lived with a partner, and 40% had one or more child. The monthly income for 56.6% of respondents was <CN¥3,000 per month (equivalent of local per capita income), 50.8% had been employed before doctoral enrollment, and 40.6% were clinical doctoral students. Furthermore, 13.8% seldom met with their mentors, 37.2% thought they should try their best to publish a PhD qualification paper, and 31.1% reported that they had difficulty in balancing work–family–PhD ( Table 1 ).

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics of respondents (n=325)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 325 | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤25 | 30 | 9.2 |

| 26–30 | 151 | 46.5 |

| ≥31 | 144 | 44.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 129 | 39.7 |

| Female | 196 | 60.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 165 | 50.8 |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 160 | 49.2 |

| Have children | ||

| No | 195 | 60 |

| One or more | 130 | 40 |

| Income (CN¥ per month) | ||

| ≤3,000 | 184 | 56.6 |

| 3,001–5,000 | 30 | 9.2 |

| ≥5,001 | 111 | 34.2 |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment | ||

| No | 160 | 49.2 |

| Yes | 165 | 50.8 |

| Clinical doctoral student | ||

| No | 193 | 59.4 |

| Yes | 132 | 40.6 |

| Grade | ||

| First year | 71 | 21.8 |

| Second year | 121 | 37.2 |

| Third year | 116 | 35.7 |

| Fourth year or above | 17 | 5.23 |

| Frequency of meeting with mentor | ||

| At least once a week | 193 | 59.4 |

| At least once a month | 87 | 26.8 |

| Seldom | 45 | 13.8 |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper | ||

| A little bit of effort | 56 | 17.2 |

| Some effort | 148 | 45.5 |

| A lot of effort | 121 | 37.2 |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program | ||

| Almost no difficulty | 98 | 30.2 |

| Some difficulty | 126 | 38.8 |

| Great difficulty | 101 | 31.1 |

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics by depression and anxiety

The prevalence of clinical depression was 23.7% (moderate, moderately severe, and severe) and the prevalence of clinical anxiety was 20.0% (moderate and severe; Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). Factors that were significantly different among respondents at varying levels of depression included age, marital status, having children, employment, grade, frequency of meeting with mentors, difficulty in publishing, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program. Factors that were significantly different among respondents at varying levels of anxiety included being a clinical doctoral student, frequency of meeting with mentors, difficulty in publishing, and difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program.

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics by depression (n=325)

| Characteristics | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None–minimal (n=114) | Mild (n=134) | Moderate (n=38) | Moderately severe (n=26) | Severe (n=13) | -value | |

| Age (years), n (%) | 0.023 | |||||

| ≤25 | 15 (50.0) | 11 (36.7) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| 26–30 | 57 (37.7) | 60 (39.7) | 21 (13.9) | 7 (4.6) | 6 (4.0) | |

| ≥31 | 42 (29.2) | 63 (43.8) | 14 (9.7) | 18 (12.5) | 7 (4.9) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.475 | |||||

| Male | 45 (34.9) | 51 (39.5) | 20 (15.5) | 9 (7.0) | 4 (3.1) | |

| Female | 69 (35.2) | 83 (42.3) | 18 (9.2) | 17 (8.7) | 9 (4.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.016 | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 52 (31.5) | 71 (43.0) | 14 (8.5) | 20 (12.1) | 8 (4.8) | |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 62 (38.8) | 63 (39.4) | 24 (15.0) | 6 (3.8) | 5 (3.1) | |

| Have children, n (%) | 0.002 | |||||

| No | 79 (40.5) | 74 (37.9) | 27 (13.8) | 8 (4.2) | 7 (3.6) | |

| One or more | 35 (26.9) | 60 (46.2) | 11 (8.5) | 18 (13.8) | 6 (4.6) | |

| Income (CN¥ per month), n (%) | 0.982 | |||||

| ≤3,000 | 69 (37.5) | 72 (39.1) | 25 (13.6) | 11 (6.0) | 7 (3.8) | |

| 3,001–5,000 | 13 (43.3) | 10 (33.3) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (10.0) | |

| ≥5,001 | 32 (28.8) | 52 (46.8) | 11 (9.9) | 13 (11.7) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Employment before doctoral enrollment, n (%) | 0.021 | |||||

| No | 68 (42.5) | 57 (35.6) | 21 (13.1) | 8 (5.0) | 6 (3.8) | |

| Yes | 46 (27.9) | 77 (46.7) | 17 (10.3) | 18 (10.9) | 7 (4.2) | |

| Clinical doctoral students, n (%) | 0.221 | |||||

| No | 74 (38.3) | 79 (40.9) | 23 (11.9) | 12 (6.2) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Yes | 40 (30.3) | 55 (41.7) | 15 (11.4) | 14 (10.6) | 8 (6.0) | |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.040 | |||||

| First year | 37 (52.1) | 20 (28.2) | 10 (14.1) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Second year | 42 (34.7) | 54 (44.6) | 11 (9.1) | 9 (7.4) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Third year | 32 (27.6) | 53 (45.7) | 14 (12.1) | 13 (11.2) | 4 (3.4) | |

| Fourth year or above | 3 (17.6) | 7 (41.2) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Frequency of meeting with mentor, n (%) | 0.090 | |||||

| At least once a week | 79 (40.9) | 78 (40.4) | 20 (10.4) | 10 (5.2) | 6 (3.1) | |

| At least once a month | 25 (28.7) | 38 (43.7) | 10 (11.5) | 9 (10.3) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Seldom | 10 (22.2) | 18 (40.0) | 8 (17.8) | 7 (15.6) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Difficulty in publishing doctoral qualification paper, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| A little bit of effort | 33 (58.9) | 19 (33.9) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.4) | 0 | |

| Some effort | 52 (35.1) | 66 (44.6) | 19 (12.8) | 6 (4.1) | 5 (3.4) | |

| A lot of effort | 29 (24.0) | 49 (40.5) | 18 (14.9) | 17 (14.0) | 8 (6.6) | |

| Difficulty in balancing work–family–doctoral program, n (%) | 0.001 | |||||

| Almost none | 51 (52.0) | 35 (35.7) | 7 (7.1) | 4 (4.1) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Some | 36 (28.6) | 59 (46.8) | 18 (14.3) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (4.0) | |

| Great | 27 (26.7) | 40 (39.6) | 13 (12.9) | 14 (13.9) | 7 (6.9) | |

Sociodemographic and doctoral characteristics by anxiety (n=325)