Understanding Case Study Method in Research: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered how researchers uncover the nuanced layers of individual experiences or the intricate workings of a particular event? One of the keys to unlocking these mysteries lies in the case study method , a research strategy that might seem straightforward at first glance but is rich with complexity and insightful potential. Let’s dive into the world of case studies and discover why they are such a valuable tool in the arsenal of research methods.

What is a Case Study Method?

At its core, the case study method is a form of qualitative research that involves an in-depth, detailed examination of a single subject, such as an individual, group, organization, event, or phenomenon. It’s a method favored when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident, and where multiple sources of data are used to illuminate the case from various perspectives. This method’s strength lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case in its real-life context.

Historical Context and Evolution of Case Studies

Case studies have been around for centuries, with their roots in medical and psychological research. Over time, their application has spread to disciplines like sociology, anthropology, business, and education. The evolution of this method has been marked by a growing appreciation for qualitative data and the rich, contextual insights it can provide, which quantitative methods may overlook.

Characteristics of Case Study Research

What sets the case study method apart are its distinct characteristics:

- Intensive Examination: It provides a deep understanding of the case in question, considering the complexity and uniqueness of each case.

- Contextual Analysis: The researcher studies the case within its real-life context, recognizing that the context can significantly influence the phenomenon.

- Multiple Data Sources: Case studies often utilize various data sources like interviews, observations, documents, and reports, which provide multiple perspectives on the subject.

- Participant’s Perspective: This method often focuses on the perspectives of the participants within the case, giving voice to those directly involved.

Types of Case Studies

There are different types of case studies, each suited for specific research objectives:

- Exploratory: These are conducted before large-scale research projects to help identify questions, select measurement constructs, and develop hypotheses.

- Descriptive: These involve a detailed, in-depth description of the case, without attempting to determine cause and effect.

- Explanatory: These are used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships and understand underlying principles of certain phenomena.

- Intrinsic: This type is focused on the case itself because the case presents an unusual or unique issue.

- Instrumental: Here, the case is secondary to understanding a broader issue or phenomenon.

- Collective: These involve studying a group of cases collectively or comparably to understand a phenomenon, population, or general condition.

The Process of Conducting a Case Study

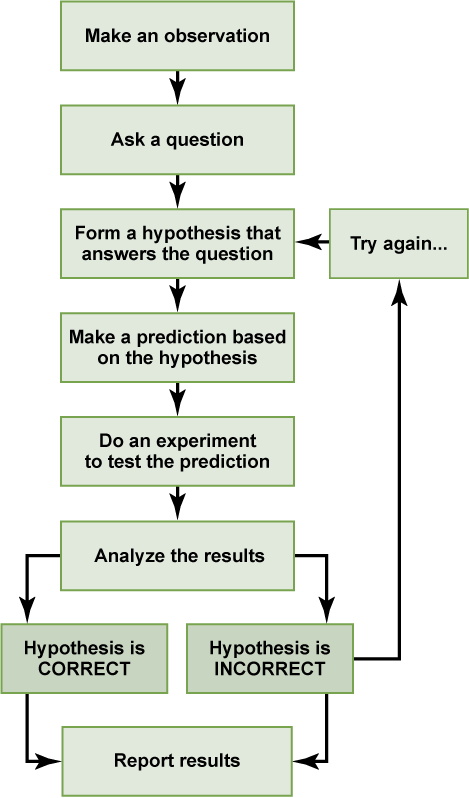

Conducting a case study involves several well-defined steps:

- Defining Your Case: What or who will you study? Define the case and ensure it aligns with your research objectives.

- Selecting Participants: If studying people, careful selection is crucial to ensure they fit the case criteria and can provide the necessary insights.

- Data Collection: Gather information through various methods like interviews, observations, and reviewing documents.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the collected data to identify patterns, themes, and insights related to your research question.

- Reporting Findings: Present your findings in a way that communicates the complexity and richness of the case study, often through narrative.

Case Studies in Practice: Real-world Examples

Case studies are not just academic exercises; they have practical applications in every field. For instance, in business, they can explore consumer behavior or organizational strategies. In psychology, they can provide detailed insight into individual behaviors or conditions. Education often uses case studies to explore teaching methods or learning difficulties.

Advantages of Case Study Research

While the case study method has its critics, it offers several undeniable advantages:

- Rich, Detailed Data: It captures data too complex for quantitative methods.

- Contextual Insights: It provides a better understanding of the phenomena in its natural setting.

- Contribution to Theory: It can generate and refine theory, offering a foundation for further research.

Limitations and Criticism

However, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations and criticisms:

- Generalizability : Findings from case studies may not be widely generalizable due to the focus on a single case.

- Subjectivity: The researcher’s perspective may influence the study, which requires careful reflection and transparency.

- Time-Consuming: They require a significant amount of time to conduct and analyze properly.

Concluding Thoughts on the Case Study Method

The case study method is a powerful tool that allows researchers to delve into the intricacies of a subject in its real-world environment. While not without its challenges, when executed correctly, the insights garnered can be incredibly valuable, offering depth and context that other methods may miss. Robert K. Yin ’s advocacy for this method underscores its potential to illuminate and explain contemporary phenomena, making it an indispensable part of the researcher’s toolkit.

Reflecting on the case study method, how do you think its application could change with the advancements in technology and data analytics? Could such a traditional method be enhanced or even replaced in the future?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Research Methods in Psychology

1 Introduction to Psychological Research – Objectives and Goals, Problems, Hypothesis and Variables

- Nature of Psychological Research

- The Context of Discovery

- Context of Justification

- Characteristics of Psychological Research

- Goals and Objectives of Psychological Research

2 Introduction to Psychological Experiments and Tests

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Extraneous Variables

- Experimental and Control Groups

- Introduction of Test

- Types of Psychological Test

- Uses of Psychological Tests

3 Steps in Research

- Research Process

- Identification of the Problem

- Review of Literature

- Formulating a Hypothesis

- Identifying Manipulating and Controlling Variables

- Formulating a Research Design

- Constructing Devices for Observation and Measurement

- Sample Selection and Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Hypothesis Testing

- Drawing Conclusion

4 Types of Research and Methods of Research

- Historical Research

- Descriptive Research

- Correlational Research

- Qualitative Research

- Ex-Post Facto Research

- True Experimental Research

- Quasi-Experimental Research

5 Definition and Description Research Design, Quality of Research Design

- Research Design

- Purpose of Research Design

- Design Selection

- Criteria of Research Design

- Qualities of Research Design

6 Experimental Design (Control Group Design and Two Factor Design)

- Experimental Design

- Control Group Design

- Two Factor Design

7 Survey Design

- Survey Research Designs

- Steps in Survey Design

- Structuring and Designing the Questionnaire

- Interviewing Methodology

- Data Analysis

- Final Report

8 Single Subject Design

- Single Subject Design: Definition and Meaning

- Phases Within Single Subject Design

- Requirements of Single Subject Design

- Characteristics of Single Subject Design

- Types of Single Subject Design

- Advantages of Single Subject Design

- Disadvantages of Single Subject Design

9 Observation Method

- Definition and Meaning of Observation

- Characteristics of Observation

- Types of Observation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Observation

- Guides for Observation Method

10 Interview and Interviewing

- Definition of Interview

- Types of Interview

- Aspects of Qualitative Research Interviews

- Interview Questions

- Convergent Interviewing as Action Research

- Research Team

11 Questionnaire Method

- Definition and Description of Questionnaires

- Types of Questionnaires

- Purpose of Questionnaire Studies

- Designing Research Questionnaires

- The Methods to Make a Questionnaire Efficient

- The Types of Questionnaire to be Included in the Questionnaire

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaire

- When to Use a Questionnaire?

12 Case Study

- Definition and Description of Case Study Method

- Historical Account of Case Study Method

- Designing Case Study

- Requirements for Case Studies

- Guideline to Follow in Case Study Method

- Other Important Measures in Case Study Method

- Case Reports

13 Report Writing

- Purpose of a Report

- Writing Style of the Report

- Report Writing – the Do’s and the Don’ts

- Format for Report in Psychology Area

- Major Sections in a Report

14 Review of Literature

- Purposes of Review of Literature

- Sources of Review of Literature

- Types of Literature

- Writing Process of the Review of Literature

- Preparation of Index Card for Reviewing and Abstracting

15 Methodology

- Definition and Purpose of Methodology

- Participants (Sample)

- Apparatus and Materials

16 Result, Analysis and Discussion of the Data

- Definition and Description of Results

- Statistical Presentation

- Tables and Figures

17 Summary and Conclusion

- Summary Definition and Description

- Guidelines for Writing a Summary

- Writing the Summary and Choosing Words

- A Process for Paraphrasing and Summarising

- Summary of a Report

- Writing Conclusions

18 References in Research Report

- Reference List (the Format)

- References (Process of Writing)

- Reference List and Print Sources

- Electronic Sources

- Book on CD Tape and Movie

- Reference Specifications

- General Guidelines to Write References

Share on Mastodon

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

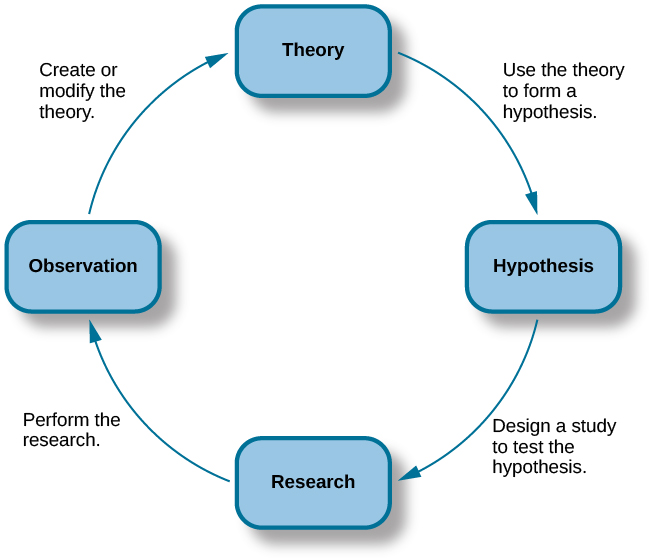

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved September 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Psychology Case Study Examples: A Deep Dive into Real-life Scenarios

Peeling back the layers of the human mind is no easy task, but psychology case studies can help us do just that. Through these detailed analyses, we’re able to gain a deeper understanding of human behavior, emotions, and cognitive processes. I’ve always found it fascinating how a single person’s experience can shed light on broader psychological principles.

Over the years, psychologists have conducted numerous case studies—each with their own unique insights and implications. These investigations range from Phineas Gage’s accidental lobotomy to Genie Wiley’s tragic tale of isolation. Such examples not only enlighten us about specific disorders or occurrences but also continue to shape our overall understanding of psychology .

As we delve into some noteworthy examples , I assure you’ll appreciate how varied and intricate the field of psychology truly is. Whether you’re a budding psychologist or simply an eager learner, brace yourself for an intriguing exploration into the intricacies of the human psyche.

Understanding Psychology Case Studies

Diving headfirst into the world of psychology, it’s easy to come upon a valuable tool used by psychologists and researchers alike – case studies. I’m here to shed some light on these fascinating tools.

Psychology case studies, for those unfamiliar with them, are in-depth investigations carried out to gain a profound understanding of the subject – whether it’s an individual, group or phenomenon. They’re powerful because they provide detailed insights that other research methods might miss.

Let me share a few examples to clarify this concept further:

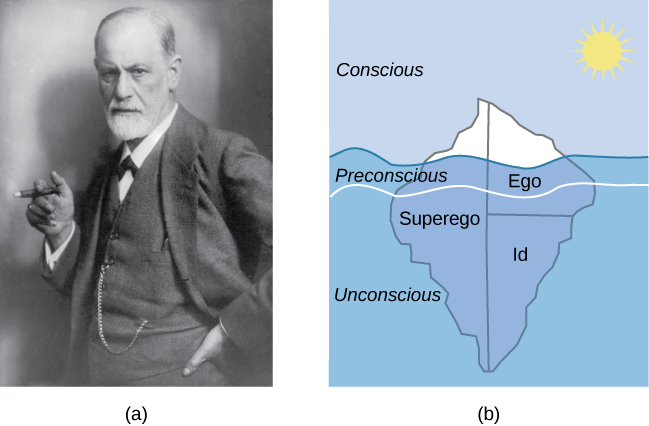

- One notable example is Freud’s study on Little Hans. This case study explored a 5-year-old boy’s fear of horses and related it back to Freud’s theories about psychosexual stages.

- Another classic example is Genie Wiley (a pseudonym), a feral child who was subjected to severe social isolation during her early years. Her heartbreaking story provided invaluable insights into language acquisition and critical periods in development.

You see, what sets psychology case studies apart is their focus on the ‘why’ and ‘how’. While surveys or experiments might tell us ‘what’, they often don’t dig deep enough into the inner workings behind human behavior.

It’s important though not to take these psychology case studies at face value. As enlightening as they can be, we must remember that they usually focus on one specific instance or individual. Thus, generalizing findings from single-case studies should be done cautiously.

To illustrate my point using numbers: let’s say we have 1 million people suffering from condition X worldwide; if only 20 unique cases have been studied so far (which would be quite typical for rare conditions), then our understanding is based on just 0.002% of the total cases! That’s why multiple sources and types of research are vital when trying to understand complex psychological phenomena fully.

| Number of People with Condition X | Number Of Unique Cases Studied | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1,000,000 | 20 | 0.002% |

In the grand scheme of things, psychology case studies are just one piece of the puzzle – albeit an essential one. They provide rich, detailed data that can form the foundation for further research and understanding. As we delve deeper into this fascinating field, it’s crucial to appreciate all the tools at our disposal – from surveys and experiments to these insightful case studies.

Importance of Case Studies in Psychology

I’ve always been fascinated by the human mind, and if you’re here, I bet you are too. Let’s dive right into why case studies play such a pivotal role in psychology.

One of the key reasons they matter so much is because they provide detailed insights into specific psychological phenomena. Unlike other research methods that might use large samples but only offer surface-level findings, case studies allow us to study complex behaviors, disorders, and even treatments at an intimate level. They often serve as a catalyst for new theories or help refine existing ones.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at one of psychology’s most famous case studies – Phineas Gage. He was a railroad construction foreman who survived a severe brain injury when an iron rod shot through his skull during an explosion in 1848. The dramatic personality changes he experienced after his accident led to significant advancements in our understanding of the brain’s role in personality and behavior.

Moreover, it’s worth noting that some rare conditions can only be studied through individual cases due to their uncommon nature. For instance, consider Genie Wiley – a girl discovered at age 13 having spent most of her life locked away from society by her parents. Her tragic story gave psychologists valuable insights into language acquisition and critical periods for learning.

Finally yet importantly, case studies also have practical applications for clinicians and therapists. Studying real-life examples can inform treatment plans and provide guidance on how theoretical concepts might apply to actual client situations.

- Detailed insights: Case studies offer comprehensive views on specific psychological phenomena.

- Catalyst for new theories: Real-life scenarios help shape our understanding of psychology .

- Study rare conditions: Unique cases can offer invaluable lessons about uncommon disorders.

- Practical applications: Clinicians benefit from studying real-world examples.

In short (but without wrapping up), it’s clear that case studies hold immense value within psychology – they illuminate what textbooks often can’t, offering a more nuanced understanding of human behavior.

Different Types of Psychology Case Studies

Diving headfirst into the world of psychology, I can’t help but be fascinated by the myriad types of case studies that revolve around this subject. Let’s take a closer look at some of them.

Firstly, we’ve got what’s known as ‘Explanatory Case Studies’. These are often used when a researcher wants to clarify complex phenomena or concepts. For example, a psychologist might use an explanatory case study to explore the reasons behind aggressive behavior in children.

Second on our list are ‘Exploratory Case Studies’, typically utilized when new and unexplored areas of research come up. They’re like pioneers; they pave the way for future studies. In psychological terms, exploratory case studies could be conducted to investigate emerging mental health conditions or under-researched therapeutic approaches.

Next up are ‘Descriptive Case Studies’. As the name suggests, these focus on depicting comprehensive and detailed profiles about a particular individual, group, or event within its natural context. A well-known example would be Sigmund Freud’s analysis of “Anna O”, which provided unique insights into hysteria.

Then there are ‘Intrinsic Case Studies’, which delve deep into one specific case because it is intrinsically interesting or unique in some way. It’s sorta like shining a spotlight onto an exceptional phenomenon. An instance would be studying savants—individuals with extraordinary abilities despite significant mental disabilities.

Lastly, we have ‘Instrumental Case Studies’. These aren’t focused on understanding a particular case per se but use it as an instrument to understand something else altogether—a bit like using one puzzle piece to make sense of the whole picture!

So there you have it! From explanatory to instrumental, each type serves its own unique purpose and adds another intriguing layer to our understanding of human behavior and cognition.

Exploring Real-Life Psychology Case Study Examples

Let’s roll up our sleeves and delve into some real-life psychology case study examples. By digging deep, we can glean valuable insights from these studies that have significantly contributed to our understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

First off, let me share the fascinating case of Phineas Gage. This gentleman was a 19th-century railroad construction foreman who survived an accident where a large iron rod was accidentally driven through his skull, damaging his frontal lobes. Astonishingly, he could walk and talk immediately after the accident but underwent dramatic personality changes, becoming impulsive and irresponsible. This case is often referenced in discussions about brain injury and personality change.

Next on my list is Genie Wiley’s heart-wrenching story. She was a victim of severe abuse and neglect resulting in her being socially isolated until she was 13 years old. Due to this horrific experience, Genie couldn’t acquire language skills typically as other children would do during their developmental stages. Her tragic story offers invaluable insight into the critical periods for language development in children.

Then there’s ‘Little Hans’, a classic Freudian case that delves into child psychology. At just five years old, Little Hans developed an irrational fear of horses -or so it seemed- which Sigmund Freud interpreted as symbolic anxiety stemming from suppressed sexual desires towards his mother—quite an interpretation! The study gave us Freud’s Oedipus Complex theory.

Lastly, I’d like to mention Patient H.M., an individual who became amnesiac following surgery to control seizures by removing parts of his hippocampus bilaterally. His inability to form new memories post-operation shed light on how different areas of our brains contribute to memory formation.

Each one of these real-life psychology case studies gives us a unique window into understanding complex human behaviors better – whether it’s dissecting the role our brain plays in shaping personality or unraveling the mysteries of fear, language acquisition, and memory.

How to Analyze a Psychology Case Study

Diving headfirst into a psychology case study, I understand it can seem like an intimidating task. But don’t worry, I’m here to guide you through the process.

First off, it’s essential to go through the case study thoroughly. Read it multiple times if needed. Each reading will likely reveal new information or perspectives you may have missed initially. Look out for any patterns or inconsistencies in the subject’s behavior and make note of them.

Next on your agenda should be understanding the theoretical frameworks that might be applicable in this scenario. Is there a cognitive-behavioral approach at play? Or does psychoanalysis provide better insights? Comparing these theories with observed behavior and symptoms can help shed light on underlying psychological issues.

Now, let’s talk data interpretation. If your case study includes raw data like surveys or diagnostic tests results, you’ll need to analyze them carefully. Here are some steps that could help:

- Identify what each piece of data represents

- Look for correlations between different pieces of data

- Compute statistics (mean, median, mode) if necessary

- Use graphs or charts for visual representation

Keep in mind; interpreting raw data requires both statistical knowledge and intuition about human behavior.

Finally, drafting conclusions is key in analyzing a psychology case study. Based on your observations, evaluations of theoretical approaches and interpretations of any given data – what do you conclude about the subject’s mental health status? Remember not to jump to conclusions hastily but instead base them solidly on evidence from your analysis.

In all this journey of analysis remember one thing: every person is unique and so are their experiences! So while theories and previous studies guide us, they never define an individual completely.

Applying Lessons from Psychology Case Studies

Let’s dive into how we can apply the lessons learned from psychology case studies. If you’ve ever studied psychology, you’ll know that case studies offer rich insights. They shed light on human behavior, mental health issues, and therapeutic techniques. But it’s not just about understanding theory. It’s also about implementing these valuable lessons in real-world situations.

One of the most famous psychological case studies is Phineas Gage’s story. This 19th-century railroad worker survived a severe brain injury which dramatically altered his personality. From this study, we gained crucial insight into how different brain areas are responsible for various aspects of our personality and behavior.

- Lesson: Recognizing that damage to specific brain areas can result in personality changes, enabling us to better understand certain mental conditions.

Sigmund Freud’s work with a patient known as ‘Anna O.’ is another landmark psychology case study. Anna displayed what was then called hysteria – symptoms included hallucinations and disturbances in speech and physical coordination – which Freud linked back to repressed memories of traumatic events.

- Lesson: The importance of exploring an individual’s history for understanding their current psychological problems – a principle at the heart of psychoanalysis.

Then there’s Genie Wiley’s case – a girl who suffered extreme neglect resulting in impaired social and linguistic development. Researchers used her tragic circumstances as an opportunity to explore theories around language acquisition and socialization.

- Lesson: Reinforcing the critical role early childhood experiences play in shaping cognitive development.

Lastly, let’s consider the Stanford Prison Experiment led by Philip Zimbardo examining how people conform to societal roles even when they lead to immoral actions.

- Lesson: Highlighting that situational forces can drastically impact human behavior beyond personal characteristics or morality.

These examples demonstrate that psychology case studies aren’t just academic exercises isolated from daily life. Instead, they provide profound lessons that help us make sense of complex human behaviors, mental health issues, and therapeutic strategies. By understanding these studies, we’re better equipped to apply their lessons in our own lives – whether it’s navigating personal relationships, working with diverse teams at work or even self-improvement.

Challenges and Critiques of Psychological Case Studies

Delving into the world of psychological case studies, it’s not all rosy. Sure, they offer an in-depth understanding of individual behavior and mental processes. Yet, they’re not without their share of challenges and criticisms.

One common critique is the lack of generalizability. Each case study is unique to its subject. We can’t always apply what we learn from one person to everyone else. I’ve come across instances where results varied dramatically between similar subjects, highlighting the inherent unpredictability in human behavior.

Another challenge lies within ethical boundaries. Often, sensitive information surfaces during these studies that could potentially harm the subject if disclosed improperly. To put it plainly, maintaining confidentiality while delivering a comprehensive account isn’t always easy.

Distortion due to subjective interpretations also poses substantial difficulties for psychologists conducting case studies. The researcher’s own bias may color their observations and conclusions – leading to skewed outcomes or misleading findings.

Moreover, there’s an ongoing debate about the scientific validity of case studies because they rely heavily on qualitative data rather than quantitative analysis. Some argue this makes them less reliable or objective when compared with other research methods such as experiments or surveys.

To summarize:

- Lack of generalizability

- Ethical dilemmas concerning privacy

- Potential distortion through subjective interpretation

- Questions about scientific validity

While these critiques present significant challenges, they do not diminish the value that psychological case studies bring to our understanding of human behavior and mental health struggles.

Conclusion: The Impact of Case Studies in Understanding Human Behavior

Case studies play a pivotal role in shedding light on human behavior. Throughout this article, I’ve discussed numerous examples that illustrate just how powerful these studies can be. Yet it’s the impact they have on our understanding of human psychology where their true value lies.

Take for instance the iconic study of Phineas Gage. It was through his tragic accident and subsequent personality change that we began to grasp the profound influence our frontal lobes have on our behavior. Without such a case study, we might still be in the dark about this crucial aspect of our neurology.

Let’s also consider Genie, the feral child who showed us the critical importance of social interaction during early development. Her heartbreaking story underscores just how vital appropriate nurturing is for healthy mental and emotional growth.

Here are some key takeaways from these case studies:

- Our brain structure significantly influences our behavior.

- Social interaction during formative years is vital for normal psychological development.

- Studying individual cases can reveal universal truths about human nature.

What stands out though, is not merely what these case studies teach us individually but collectively. They remind us that each person constitutes a unique combination of various factors—biological, psychological, and environmental—that shape their behavior.

One cannot overstate the significance of case studies in psychology—they are more than mere stories or isolated incidents; they’re windows into the complexities and nuances of human nature itself.

In wrapping up, I’d say that while statistics give us patterns and trends to understand groups, it’s these detailed narratives offered by case studies that help us comprehend individuals’ unique experiences within those groups—making them an invaluable part of psychological research.

Related Posts

Cracking the Anxious-Avoidant Code

Deflection: Unraveling the Science Behind Material Bending

Case Study Research

- First Online: 29 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Robert E. White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8045-164X 3 &

- Karyn Cooper 4

2340 Accesses

1 Citations

As a footnote to the previous chapter, there is such a beast known as the ethnographic case study. Ethnographic case study has found its way into this chapter rather than into the previous one because of grammatical considerations. Simply put, the “case study” part of the phrase is the noun (with “case” as an adjective defining what kind of study it is), while the “ethnographic” part of the phrase is an adjective defining the type of case study that is being conducted. As such, the case study becomes the methodology, while the ethnography part refers to a method, mode or approach relating to the development of the study.

The experiential account that we get from a case study or qualitative research of a similar vein is just so necessary. How things happen over time and the degree to which they are subject to personality and how they are only gradually perceived as tolerable or intolerable by the communities and the groups that are involved is so important. Robert Stake, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Rethinking case study research . Routledge.

Google Scholar

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity . Polity Press.

Bhaskar, R., & Danermark, B. (2006). Metatheory, interdisciplinarity and disability research: A critical realist perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8 (4), 278–297.

Article Google Scholar

Bulmer, M. (1986). The Chicago School of sociology: Institutionalization, diversity, and the rise of sociological research . University of Chicago Press.

Campbell, D. T. (1975). Degrees of freedom and the case study. Comparative Political Studies, 8 (1), 178–191.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1966). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research . Houghton Mifflin.

Chua, W. F. (1986). Radical developments in accounting thought. The Accounting Review, 61 (4), 601–632.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design . Sage.

Davey, L. (1991). The application of case study evaluations. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation 2 (9) . Retrieved May 28, 2018, from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=2&n=9

Demetriou, H. (2017). The case study. In E. Wilson (Ed.), School-based research: A guide for education students (pp. 124–138). Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research . Sage.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. In C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 420–433). Sage.

Hamel, J., Dufour, S., & Fortin, D. (1993). Case study methods . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Healy, M. E. (1947). Le Play’s contribution to sociology: His method. The American Catholic Sociological Review, 8 (2), 97–110.

Johansson, R. (2003). Case study methodology. [Keynote speech]. In International Conference “Methodologies in Housing Research.” Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, September 2003 (pp. 1–14).

Klonoski, R. (2013). The case for case studies: Deriving theory from evidence. Journal of Business Case Studies, 9 (31), 261–266.

McDonough, J., & McDonough, S. (1997). Research methods for English language teachers . Routledge.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education . Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B. (1979). Qualitative data as an attractive nuisance: The problem of analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4), 590–601.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Mills, A. J., Durepos, G. & E. Wiebe (Eds.) (2010). What is a case study? Encyclopedia of case study research, Volumes I and II. Sage.

National Film Board of Canada. (2012, April). Here at home: In search of the real cost of homelessness . [Web documentary]. Retrieved February 9, 2020, from http://athome.nfb.ca/#/athome/home

Popper, K. (2002). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge . Routledge.

Ridder, H.-G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research, 10 (2), 281–305.

Rolls, G. (2005). Classic case studies in psychology . Hodder Education.

Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case-Selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61 , 294–308.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . Sage.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Multiple case study analysis . Guilford Press.

Swanborn, P. G. (2010). Case study research: What, why and how? Sage.

Thomas, W. I., & Znaniecki, F. (1996). The Polish peasant in Europe and America: A classic work in immigration history . University of Illinois Press.

Yin, R. K. (1981). The case study crisis: Some answers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26 (1), 58–65.

Yin, R. K. (1991). Advancing rigorous methodologies : A Review of “Towards Rigor in Reviews of Multivocal Literatures….”. Review of Educational Research, 61 (3), 299–305.

Yin, R. K. (1999). Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Services Research, 34 (5) Part II, 1209–1224.

Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

Zaretsky, E. (1996). Introduction. In W. I. Thomas & F. Znaniecki (Eds.), The Polish peasant in Europe and America: A classic work in immigration history (pp. vii–xvii). University of Illinois Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada

Robert E. White

OISE, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Karyn Cooper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert E. White .

A Case in Case Study Methodology

Christine Benedichte Meyer

Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration

Meyer, C. B. (2001). A Case in Case Study Methodology. Field Methods 13 (4), 329-352.

The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive view of the case study process from the researcher’s perspective, emphasizing methodological considerations. As opposed to other qualitative or quantitative research strategies, such as grounded theory or surveys, there are virtually no specific requirements guiding case research. This is both the strength and the weakness of this approach. It is a strength because it allows tailoring the design and data collection procedures to the research questions. On the other hand, this approach has resulted in many poor case studies, leaving it open to criticism, especially from the quantitative field of research. This article argues that there is a particular need in case studies to be explicit about the methodological choices one makes. This implies discussing the wide range of decisions concerned with design requirements, data collection procedures, data analysis, and validity and reliability. The approach here is to illustrate these decisions through a particular case study of two mergers in the financial industry in Norway.

In the past few years, a number of books have been published that give useful guidance in conducting qualitative studies (Gummesson 1988; Cassell & Symon 1994; Miles & Huberman 1994; Creswell 1998; Flick 1998; Rossman & Rallis 1998; Bryman & Burgess 1999; Marshall & Rossman 1999; Denzin & Lincoln 2000). One approach often mentioned is the case study (Yin 1989). Case studies are widely used in organizational studies in the social science disciplines of sociology, industrial relations, and anthropology (Hartley 1994). Such a study consists of detailed investigation of one or more organizations, or groups within organizations, with a view to providing an analysis of the context and processes involved in the phenomenon under study.

As opposed to other qualitative or quantitative research strategies, such as grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967) or surveys (Nachmias & Nachmias 1981), there are virtually no specific requirements guiding case research. Yin (1989) and Eisenhardt (1989) give useful insights into the case study as a research strategy, but leave most of the design decisions on the table. This is both the strength and the weakness of this approach. It is a strength because it allows tailoring the design and data collection procedures to the research questions. On the other hand, this approach has resulted in many poor case studies, leaving it open to criticism, especially from the quantitative field of research (Cook and Campbell 1979). The fact that the case study is a rather loose design implies that there are a number of choices that need to be addressed in a principled way.

Although case studies have become a common research strategy, the scope of methodology sections in articles published in journals is far too limited to give the readers a detailed and comprehensive view of the decisions taken in the particular studies, and, given the format of methodology sections, will remain so. The few books (Yin 1989, 1993; Hamel, Dufour, & Fortin 1993; Stake 1995) and book chapters on case studies (Hartley 1994; Silverman 2000) are, on the other hand, mainly normative and span a broad range of different kinds of case studies. One exception is Pettigrew (1990, 1992), who places the case study in the context of a research tradition (the Warwick process research).

Given the contextual nature of the case study and its strength in addressing contemporary phenomena in real-life contexts, I believe that there is a need for articles that provide a comprehensive overview of the case study process from the researcher’s perspective, emphasizing methodological considerations. This implies addressing the whole range of choices concerning specific design requirements, data collection procedures, data analysis, and validity and reliability.

WHY A CASE STUDY?

Case studies are tailor-made for exploring new processes or behaviors or ones that are little understood (Hartley 1994). Hence, the approach is particularly useful for responding to how and why questions about a contemporary set of events (Leonard-Barton 1990). Moreover, researchers have argued that certain kinds of information can be difficult or even impossible to tackle by means other than qualitative approaches such as the case study (Sykes 1990). Gummesson (1988:76) argues that an important advantage of case study research is the opportunity for a holistic view of the process: “The detailed observations entailed in the case study method enable us to study many different aspects, examine them in relation to each other, view the process within its total environment and also use the researchers’ capacity for ‘verstehen.’ ”

The contextual nature of the case study is illustrated in Yin’s (1993:59) definition of a case study as an empirical inquiry that “investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context and addresses a situation in which the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

The key difference between the case study and other qualitative designs such as grounded theory and ethnography (Glaser & Strauss 1967; Strauss & Corbin 1990; Gioia & Chittipeddi 1991) is that the case study is open to the use of theory or conceptual categories that guide the research and analysis of data. In contrast, grounded theory or ethnography presupposes that theoretical perspectives are grounded in and emerge from firsthand data. Hartley (1994) argues that without a theoretical framework, the researcher is in severe danger of providing description without meaning. Gummesson (1988) says that a lack of preunderstanding will cause the researcher to spend considerable time gathering basic information. This preunderstanding may arise from general knowledge such as theories, models, and concepts or from specific knowledge of institutional conditions and social patterns. According to Gummesson, the key is not to require researchers to have split but dual personalities: “Those who are able to balance on a razor’s edge using their pre-understanding without being its slave” (p. 58).

DESCRIPTION OF THE ILLUSTRATIVE STUDY

The study that will be used for illustrative purposes is a comparative and longitudinal case study of organizational integration in mergers and acquisitions taking place in Norway. The study had two purposes: (1) to identify contextual factors and features of integration that facilitated or impeded organizational integration, and (2) to study how the three dimensions of organizational integration (integration of tasks, unification of power, and integration of cultures and identities) interrelated and evolved over time. Examples of contextual factors were relative power, degree of friendliness, and economic climate. Integration features included factors such as participation, communication, and allocation of positions and functions.

Mergers and acquisitions are inherently complex. Researchers in the field have suggested that managers continuously underestimate the task of integrating the merging organizations in the postintegration process (Haspeslaph & Jemison 1991). The process of organizational integration can lead to sharp interorganizational conflict as the different top management styles, organizational and work unit cultures, systems, and other aspects of organizational life come into contact (Blake & Mounton 1985; Schweiger & Walsh 1990; Cartwright & Cooper 1993). Furthermore, cultural change in mergers and acquisitions is compounded by additional uncertainties, ambiguities, and stress inherent in the combination process (Buono & Bowditch 1989).

I focused on two combinations: one merger and one acquisition. The first case was a merger between two major Norwegian banks, Bergen Bank and DnC (to be named DnB), that started in the late 1980s. The second case was a study of a major acquisition in the insurance industry (i.e., Gjensidige’s acquisition of Forenede), that started in the early 1990s. Both combinations aimed to realize operational synergies though merging the two organizations into one entity. This implied disruption of organizational boundaries and threat to the existing power distribution and organizational cultures.

The study of integration processes in mergers and acquisitions illustrates the need to find a design that opens for exploration of sensitive issues such as power struggles between the two merging organizations. Furthermore, the inherent complexity in the integration process, involving integration of tasks, unification of power, and cultural integration stressed the need for in-depth study of the phenomenon over time. To understand the cultural integration process, the design also had to be linked to the past history of the two organizations.

DESIGN DECISIONS

In the introduction, I stressed that a case is a rather loose design that requires that a number of design choices be made. In this section, I go through the most important choices I faced in the study of organizational integration in mergers and acquisitions. These include: (1) selection of cases; (2) sampling time; (3) choosing business areas, divisions, and sites; and (4) selection of and choices regarding data collection procedures, interviews, documents, and observation.

Selection of Cases

There are several choices involved in selecting cases. First, there is the question of how many cases to include. Second, one must sample cases and decide on a unit of analysis. I will explore these issues subsequently.

Single or Multiple Cases

Case studies can involve single or multiple cases. The problem of single cases is limitations in generalizability and several information-processing biases (Eisenhardt 1989).

One way to respond to these biases is by applying a multi-case approach (Leonard-Barton 1990). Multiple cases augment external validity and help guard against observer biases. Moreover, multi-case sampling adds confidence to findings. By looking at a range of similar and contrasting cases, we can understand a single-case finding, grounding it by specifying how and where and, if possible, why it behaves as it does. (Miles & Huberman 1994)

Given these limitations of the single case study, it is desirable to include more than one case study in the study. However, the desire for depth and a pluralist perspective and tracking the cases over time implies that the number of cases must be fairly few. I chose two cases, which clearly does not support generalizability any more than does one case, but allows for comparison and contrast between the cases as well as a deeper and richer look at each case.

Originally, I planned to include a third case in the study. Due to changes in management during the initial integration process, my access to the case was limited and I left this case entirely. However, a positive side effect was that it allowed a deeper investigation of the two original cases and in hindsight turned out to be a good decision.

Sampling Cases

The logic of sampling cases is fundamentally different from statistical sampling. The logic in case studies involves theoretical sampling, in which the goal is to choose cases that are likely to replicate or extend the emergent theory or to fill theoretical categories and provide examples for polar types (Eisenhardt 1989). Hence, whereas quantitative sampling concerns itself with representativeness, qualitative sampling seeks information richness and selects the cases purposefully rather than randomly (Crabtree and Miller 1992).

The choice of cases was guided by George (1979) and Pettigrew’s (1990) recommendations. The aim was to find cases that matched the three dimensions in the dependent variable and provided variation in the contextual factors, thus representing polar cases.

To match the choice of outcome variable, organizational integration, I chose cases in which the purpose was to fully consolidate the merging parties’ operations. A full consolidation would imply considerable disruption in the organizational boundaries and would be expected to affect the task-related, political, and cultural features of the organizations. As for the contextual factors, the two cases varied in contextual factors such as relative power, friendliness, and economic climate. The DnB merger was a friendly combination between two equal partners in an unfriendly economic climate. Gjensidige’s acquisition of Forenede was, in contrast, an unfriendly and unbalanced acquisition in a friendly economic climate.

Unit of Analysis

Another way to respond to researchers’ and respondents’ biases is to have more than one unit of analysis in each case (Yin 1993). This implies that, in addition to developing contrasts between the cases, researchers can focus on contrasts within the cases (Hartley 1994). In case studies, there is a choice of a holistic or embedded design (Yin 1989). A holistic design examines the global nature of the phenomenon, whereas an embedded design also pays attention to subunit(s).

I used an embedded design to analyze the cases (i.e., within each case, I also gave attention to subunits and subprocesses). In both cases, I compared the combination processes in the various divisions and local networks. Moreover, I compared three distinct change processes in DnB: before the merger, during the initial combination, and two years after the merger. The overall and most important unit of analysis in the two cases was, however, the integration process.

Sampling Time

According to Pettigrew (1990), time sets a reference for what changes can be seen and how those changes are explained. When conducting a case study, there are several important issues to decide when sampling time. The first regards how many times data should be collected, while the second concerns when to enter the organizations. There is also a need to decide whether to collect data on a continuous basis or in distinct periods.

Number of data collections. I studied the process by collecting real time and retrospective data at two points in time, with one-and-a-half- and two-year intervals in the two cases. Collecting data twice had some interesting implications for the interpretations of the data. During the first data collection in the DnB study, for example, I collected retrospective data about the premerger and initial combination phase and real-time data about the second step in the combination process.

Although I gained a picture of how the employees experienced the second stage of the combination process, it was too early to assess the effects of this process at that stage. I entered the organization two years later and found interesting effects that I had not anticipated the first time. Moreover, it was interesting to observe how people’s attitudes toward the merger processes changed over time to be more positive and less emotional.

When to enter the organizations. It would be desirable to have had the opportunity to collect data in the precombination processes. However, researchers are rarely given access in this period due to secrecy. The emphasis in this study was to focus on the postcombination process. As such, the precombination events were classified as contextual factors. This implied that it was most important to collect real-time data after the parties had been given government approval to merge or acquire. What would have been desirable was to gain access earlier in the postcombination process. This was not possible because access had to be negotiated. Due to the change of CEO in the middle of the merger process and the need for renegotiating access, this took longer than expected.

Regarding the second case, I was restricted by the time frame of the study. In essence, I had to choose between entering the combination process as soon as governmental approval was given, or entering the organization at a later stage. In light of the previous studies in the field that have failed to go beyond the initial two years, and given the need to collect data about the cultural integration process, I chose the latter strategy. And I decided to enter the organizations at two distinct periods of time rather than on a continuous basis.

There were several reasons for this approach, some methodological and some practical. First, data collection on a continuous basis would have required use of extensive observation that I didn’t have access to, and getting access to two data collections in DnB was difficult in itself. Second, I had a stay abroad between the first and second data collection in Gjensidige. Collecting data on a continuous basis would probably have allowed for better mapping of the ongoing integration process, but the contrasts between the two different stages in the integration process that I wanted to elaborate would probably be more difficult to detect. In Table 1 I have listed the periods of time in which I collected data in the two combinations.

Sampling Business Areas, Divisions, and Sites

Even when the cases for a study have been chosen, it is often necessary to make further choices within each case to make the cases researchable. The most important criteria that set the boundaries for the study are importance or criticality, relevance, and representativeness. At the time of the data collection, my criteria for making these decisions were not as conscious as they may appear here. Rather, being restricted by time and my own capacity as a researcher, I had to limit the sites and act instinctively. In both cases, I decided to concentrate on the core businesses (criticality criterion) and left out the business units that were only mildly affected by the integration process (relevance criterion). In the choice of regional offices, I used the representativeness criterion as the number of offices widely exceeded the number of sites possible to study. In making these choices, I relied on key informants in the organizations.

SELECTION OF DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES

The choice of data collection procedures should be guided by the research question and the choice of design. The case study approach typically combines data collection methods such as archives, interviews, questionnaires, and observations (Yin 1989). This triangulated methodology provides stronger substantiation of constructs and hypotheses. However, the choice of data collection methods is also subject to constraints in time, financial resources, and access.

I chose a combination of interviews, archives, and observation, with main emphasis on the first two. Conducting a survey was inappropriate due to the lack of established concepts and indicators. The reason for limited observation, on the other hand, was due to problems in obtaining access early in the study and time and resource constraints. In addition to choosing among several different data collection methods, there are a number of choices to be made for each individual method.

When relying on interviews as the primary data collection method, the issue of building trust between the researcher and the interviewees becomes very important. I addressed this issue by several means. First, I established a procedure of how to approach the interviewees. In most cases, I called them first, then sent out a letter explaining the key features of the project and outlining the broad issues to be addressed in the interview. In this letter, the support from the institution’s top management was also communicated. In most cases, the top management’s support of the project was an important prerequisite for the respondent’s input. Some interviewees did, however, fear that their input would be open to the top management without disguising the information source. Hence, it became important to communicate how I intended to use and store the information.

To establish trust, I also actively used my preunderstanding of the context in the first case and the phenomenon in the second case. As I built up an understanding of the cases, I used this information to gain confidence. The active use of my preunderstanding did, however, pose important challenges in not revealing too much of the research hypotheses and in balancing between asking open-ended questions and appearing knowledgeable.

There are two choices involved in conducting interviews. The first concerns the sampling of interviewees. The second is that you must decide on issues such as the structure of the interviews, use of tape recorder, and involvement of other researchers.

Sampling Interviewees

Following the desire for detailed knowledge of each case and for grasping different participant’s views the aim was, in line with Pettigrew (1990), to apply a pluralist view by describing and analyzing competing versions of reality as seen by actors in the combination processes.

I used four criteria for sampling informants. First, I drew informants from populations representing multiple perspectives. The first data collection in DnB was primarily focused on the top management level. Moreover, most middle managers in the first data collection were employed at the head offices, either in Bergen or Oslo. In the second data collection, I compensated for this skew by including eight local middle managers in the sample. The difference between the number of employees interviewed in DnB and Gjensidige was primarily due to the fact that Gjensidige has three unions, whereas DnB only has one. The distribution of interviewees is outlined in Table 2 .

The second criterion was to use multiple informants. According to Glick et al. (1990), an important advantage of using multiple informants is that the validity of information provided by one informant can be checked against that provided by other informants. Moreover, the validity of the data used by the researcher can be enhanced by resolving the discrepancies among different informants’ reports. Hence, I selected multiple respondents from each perspective.

Third, I focused on key informants who were expected to be knowledgeable about the combination process. These people included top management members, managers, and employees involved in the integration project. To validate the information from these informants, I also used a fourth criterion by selecting managers and employees who had been affected by the process but who were not involved in the project groups.

Structured versus unstructured. In line with the explorative nature of the study, the goal of the interviews was to see the research topic from the perspective of the interviewee, and to understand why he or she came to have this particular perspective. To meet this goal, King (1994:15) recommends that one have “a low degree of structure imposed on the interviewer, a preponderance of open questions, a focus on specific situations and action sequences in the world of the interviewee rather than abstractions and general opinions.” In line with these recommendations, the collection of primary data in this study consists of unstructured interviews.

Using tape recorders and involving other researchers. The majority of the interviews were tape-recorded, and I could thus concentrate fully on asking questions and responding to the interviewees’ answers. In the few interviews that were not tape-recorded, most of which were conducted in the first phase of the DnB-study, two researchers were present. This was useful as we were both able to discuss the interviews later and had feedback on the role of an interviewer.

In hindsight, however, I wish that these interviews had been tape-recorded to maintain the level of accuracy and richness of data. Hence, in the next phases of data collection, I tape-recorded all interviews, with two exceptions (people who strongly opposed the use of this device). All interviews that were tape-recorded were transcribed by me in full, which gave me closeness and a good grasp of the data.

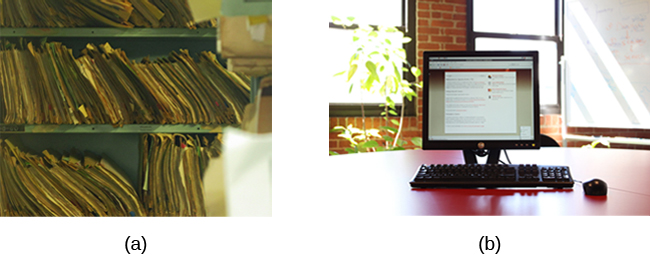

When organizations merge or make acquisitions, there are often a vast number of documents to choose from to build up an understanding of what has happened and to use in the analyses. Furthermore, when firms make acquisitions or merge, they often hire external consultants, each of whom produces more documents. Due to time constraints, it is seldom possible to collect and analyze all these documents, and thus the researcher has to make a selection.

The choice of documentation was guided by my previous experience with merger and acquisition processes and the research question. Hence, obtaining information on the postintegration process was more important than gaining access to the due-diligence analysis. As I learned about the process, I obtained more documents on specific issues. I did not, however, gain access to all the documents I asked for, and, in some cases, documents had been lost or shredded.

The documents were helpful in a number of ways. First, and most important, they were used as inputs to the interview guide and saved me time, because I did not have to ask for facts in the interviews. They were also useful for tracing the history of the organizations and statements made by key people in the organizations. Third, the documents were helpful in counteracting the biases of the interviews. A list of the documents used in writing the cases is shown in Table 3 .

Observation

The major strength of direct observation is that it is unobtrusive and does not require direct interaction with participants (Adler and Adler 1994). Observation produces rigor when it is combined with other methods. When the researcher has access to group processes, direct observation can illuminate the discrepancies between what people said in the interviews and casual conversations and what they actually do (Pettigrew 1990).

As with interviews, there are a number of choices involved in conducting observations. Although I did some observations in the study, I used interviews as the key data collection source. Discussion in this article about observations will thus be somewhat limited. Nevertheless, I faced a number of choices in conducting observations, including type of observation, when to enter, how much observation to conduct, and which groups to observe.

The are four ways in which an observer may gather data: (1) the complete participant who operates covertly, concealing any intention to observe the setting; (2) the participant-as-observer, who forms relationships and participates in activities, but makes no secret of his or her intentions to observe events; (3) the observer-as-participant, who maintains only superficial contact with the people being studied; and (4) the complete observer, who merely stands back and eavesdrops on the proceedings (Waddington 1994).

In this study, I used the second and third ways of observing. The use of the participant-as-observer mode, on which much ethnographic research is based, was rather limited in the study. There were two reasons for this. First, I had limited time available for collecting data, and in my view interviews made more effective use of this limited time than extensive participant observation. Second, people were rather reluctant to let me observe these political and sensitive processes until they knew me better and felt I could be trusted. Indeed, I was dependent on starting the data collection before having built sufficient trust to observe key groups in the integration process. Nevertheless, Gjensidige allowed me to study two employee seminars to acquaint me with the organization. Here I admitted my role as an observer but participated fully in the activities. To achieve variation, I chose two seminars representing polar groups of employees.

As observer-as-participant, I attended a top management meeting at the end of the first data collection in Gjensidige and observed the respondents during interviews and in more informal meetings, such as lunches. All these observations gave me an opportunity to validate the data from the interviews. Observing the top management group was by far the most interesting and rewarding in terms of input.

Both DnB and Gjensidige started to open up for more extensive observation when I was about to finish the data collection. By then, I had built up the trust needed to undertake this approach. Unfortunately, this came a little late for me to take advantage of it.

DATA ANALYSIS

Published studies generally describe research sites and data-collection methods, but give little space to discuss the analysis (Eisenhardt 1989). Thus, one cannot follow how a researcher arrives at the final conclusions from a large volume of field notes (Miles and Huberman 1994).

In this study, I went through the stages by which the data were reduced and analyzed. This involved establishing the chronology, coding, writing up the data according to phases and themes, introducing organizational integration into the analysis, comparing the cases, and applying the theory. I will discuss these phases accordingly.

The first step in the analysis was to establish the chronology of the cases. To do this, I used internal and external documents. I wrote the chronologies up and included appendices in the final report.

The next step was to code the data into phases and themes reflecting the contextual factors and features of integration. For the interviews, this implied marking the text with a specific phase and a theme, and grouping the paragraphs on the same theme and phase together. I followed the same procedure in organizing the documents.

I then wrote up the cases using phases and themes to structure them. Before starting to write up the cases, I scanned the information on each theme, built up the facts and filled in with perceptions and reactions that were illustrative and representative of the data.

The documents were primarily useful in establishing the facts, but they also provided me with some perceptions and reactions that were validated in the interviews. The documents used included internal letters and newsletters as well as articles from the press. The interviews were less factual, as intended, and gave me input to assess perceptions and reactions. The limited observation was useful to validate the data from the interviews. The result of this step was two descriptive cases.

To make each case more analytical, I introduced the three dimensions of organizational integration—integration of tasks, unification of power, and cultural integration—into the analysis. This helped to focus the case and to develop a framework that could be used to compare the cases. The cases were thus structured according to phases, organizational integration, and themes reflecting the factors and features in the study.

I took all these steps to become more familiar with each case as an individual entity. According to Eisenhardt (1989:540), this is a process that “allows the unique patterns of each case to emerge before the investigators push to generalise patterns across cases. In addition it gives investigators a rich familiarity with each case which, in turn, accelerates cross-case comparison.”

The comparison between the cases constituted the next step in the analysis. Here, I used the categories from the case chapters, filled in the features and factors, and compared and contrasted the findings. The idea behind cross-case searching tactics is to force investigators to go beyond initial impressions, especially through the use of structural and diverse lenses on the data. These tactics improve the likelihood of accurate and reliable theory, that is, theory with a close fit to the data (Eisenhardt 1989).

As a result, I had a number of overall themes, concepts, and relationships that had emerged from the within-case analysis and cross-case comparisons. The next step was to compare these emergent findings with theory from the organizational field of mergers and acquisitions, as well as other relevant perspectives.

This method of generalization is known as analytical generalization. In this approach, a previously developed theory is used as a template with which to compare the empirical results of the case study (Yin 1989). This comparison of emergent concepts, theory, or hypotheses with the extant literature involves asking what it is similar to, what it contradicts, and why. The key to this process is to consider a broad range of theory (Eisenhardt 1989). On the whole, linking emergent theory to existent literature enhances the internal validity, generalizability, and theoretical level of theory-building from case research.

According to Eisenhardt (1989), examining literature that conflicts with the emergent literature is important for two reasons. First, the chance of neglecting conflicting findings is reduced. Second, “conflicting results forces researchers into a more creative, frame-breaking mode of thinking than they might otherwise be able to achieve” (p. 544). Similarly, Eisenhardt (1989) claims that literature discussing similar findings is important because it ties together underlying similarities in phenomena not normally associated with each other. The result is often a theory with a stronger internal validity, wider generalizability, and a higher conceptual level.

The analytical generalization in the study included exploring and developing the concepts and examining the relationships between the constructs. In carrying out this analytical generalization, I acted on Eisenhardt’s (1989) recommendation to use a broad range of theory. First, I compared and contrasted the findings with the organizational stream on mergers and acquisition literature. Then I discussed other relevant literatures, including strategic change, power and politics, social justice, and social identity theory to explore how these perspectives could contribute to the understanding of the findings. Finally, I discussed the findings that could not be explained either by the merger and acquisition literature or the four theoretical perspectives.

In every scientific study, questions are raised about whether the study is valid and reliable. The issues of validity and reliability in case studies are just as important as for more deductive designs, but the application is fundamentally different.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY