Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

PhD Defence Process: A Comprehensive Guide

Embarking on the journey toward a PhD is an intellectual odyssey marked by tireless research, countless hours of contemplation, and a fervent commitment to contributing to the body of knowledge in one’s field. As the culmination of this formidable journey, the PhD defence stands as the final frontier, the proverbial bridge between student and scholar.

In this comprehensive guide, we unravel the intricacies of the PhD defence—a momentous occasion that is both a celebration of scholarly achievement and a rigorous evaluation of academic prowess. Join us as we explore the nuances of the defence process, addressing questions about its duration, contemplating the possibility of failure, and delving into the subtle distinctions of language that surround it.

Beyond the formalities, we aim to shed light on the significance of this rite of passage, dispelling misconceptions about its nature. Moreover, we’ll consider the impact of one’s attire on this critical day and share personal experiences and practical tips from those who have successfully navigated the defence journey.

Whether you are on the precipice of your own defence or are simply curious about the process, this guide seeks to demystify the PhD defence, providing a roadmap for success and a nuanced understanding of the pivotal event that marks the transition from student to scholar.

Introduction

A. definition and purpose:, b. overview of the oral examination:, a. general duration of a typical defense, b. factors influencing the duration:, c. preparation and flexibility:, a. preparation and thorough understanding of the research:, b. handling questions effectively:, c. confidence and composure during the presentation:, d. posture of continuous improvement:, a. exploring the possibility of failure:, b. common reasons for failure:, c. steps to mitigate the risk of failure:, d. post-failure resilience:, a. addressing the language variation:, b. conforming to regional preferences:, c. consistency in usage:, d. flexibility and adaptability:, e. navigating language in a globalized academic landscape:, a. debunking myths around the formality of the defense:, b. significance in validating research contributions:, c. post-defense impact:, a. appropriate attire for different settings:, b. professionalism and the impact of appearance:, c. practical tips for dressing success:, b. practical tips for a successful defense:, c. post-defense reflections:, career options after phd.

Embarking on the doctoral journey is a formidable undertaking, where aspiring scholars immerse themselves in the pursuit of knowledge, contributing new insights to their respective fields. At the pinnacle of this academic odyssey lies the PhD defence—a culmination that transcends the boundaries of a mere formality, symbolizing the transformation from a student of a discipline to a recognized contributor to the academic tapestry.

The PhD defence, also known as the viva voce or oral examination, is a pivotal moment in the life of a doctoral candidate.

PhD defence is not merely a ritualistic ceremony; rather, it serves as a platform for scholars to present, defend, and elucidate the findings and implications of their research. The defence is the crucible where ideas are tested, hypotheses scrutinized, and the depth of scholarly understanding is laid bare.

The importance of the PhD defence reverberates throughout the academic landscape. It is not just a capstone event; it is the juncture where academic rigour meets real-world application. The defence is the litmus test of a researcher’s ability to articulate, defend, and contextualize their work—an evaluation that extends beyond the pages of a dissertation.

Beyond its evaluative nature, the defence serves as a rite of passage, validating the years of dedication, perseverance, and intellectual rigour invested in the research endeavour. Success in the defence is a testament to the candidate’s mastery of their subject matter and the originality and impact of their contributions to the academic community.

Furthermore, a successful defence paves the way for future contributions, positioning the scholar as a recognized authority in their field. The defence is not just an endpoint; it is a launchpad, propelling researchers into the next phase of their academic journey as they continue to shape and redefine the boundaries of knowledge.

In essence, the PhD defence is more than a ceremonial checkpoint—it is a transformative experience that validates the intellectual journey, underscores the significance of scholarly contributions, and sets the stage for a continued legacy of academic excellence. As we navigate the intricacies of this process, we invite you to explore the multifaceted dimensions that make the PhD defence an indispensable chapter in the narrative of academic achievement.

What is a PhD Defence?

At its core, a PhD defence is a rigorous and comprehensive examination that marks the culmination of a doctoral candidate’s research journey. It is an essential component of the doctoral process in which the candidate is required to defend their dissertation before a committee of experts in the field. The defence serves multiple purposes, acting as both a showcase of the candidate’s work and an evaluative measure of their understanding, critical thinking, and contributions to the academic domain.

The primary goals of a PhD defence include:

- Presentation of Research: The candidate presents the key findings, methodology, and significance of their research.

- Demonstration of Mastery: The defence assesses the candidate’s depth of understanding, mastery of the subject matter, and ability to engage in scholarly discourse.

- Critical Examination: Committee members rigorously question the candidate, challenging assumptions, testing methodologies, and probing the boundaries of the research.

- Validation of Originality: The defence validates the originality and contribution of the candidate’s work to the existing body of knowledge.

The PhD defence often takes the form of an oral examination, commonly referred to as the viva voce. This oral component adds a dynamic and interactive dimension to the evaluation process. Key elements of the oral examination include:

- Presentation: The candidate typically begins with a formal presentation, summarizing the dissertation’s main components, methodology, and findings. This presentation is an opportunity to showcase the significance and novelty of the research.

- Questioning and Discussion: Following the presentation, the candidate engages in a thorough questioning session with the examination committee. Committee members explore various aspects of the research, challenging the candidates to articulate their rationale, defend their conclusions, and respond to critiques.

- Defence of Methodology: The candidate is often required to defend the chosen research methodology, demonstrating its appropriateness, rigour, and contribution to the field.

- Evaluation of Contributions: Committee members assess the originality and impact of the candidate’s contributions to the academic discipline, seeking to understand how the research advances existing knowledge.

The oral examination is not a mere formality; it is a dynamic exchange that tests the candidate’s intellectual acumen, research skills, and capacity to contribute meaningfully to the scholarly community.

In essence, the PhD defence is a comprehensive and interactive evaluation that encapsulates the essence of a candidate’s research journey, demanding a synthesis of knowledge, clarity of expression, and the ability to navigate the complexities of academic inquiry. As we delve into the specifics of the defence process, we will unravel the layers of preparation and skill required to navigate this transformative academic milestone.

How Long is a PhD Defence?

The duration of a PhD defence can vary widely, but it typically ranges from two to three hours. This time frame encompasses the candidate’s presentation of their research, questioning and discussions with the examination committee, and any additional deliberations or decisions by the committee. However, it’s essential to note that this is a general guideline, and actual defence durations may vary based on numerous factors.

- Sciences and Engineering: Defenses in these fields might lean towards the shorter end of the spectrum, often around two hours. The focus is often on the methodology, results, and technical aspects.

- Humanities and Social Sciences: Given the theoretical and interpretive nature of research in these fields, defences might extend closer to three hours or more. Discussions may delve into philosophical underpinnings and nuanced interpretations.

- Simple vs. Complex Studies: The complexity of the research itself plays a role. Elaborate experiments, extensive datasets, or intricate theoretical frameworks may necessitate a more extended defence.

- Number of Committee Members: A larger committee or one with diverse expertise may lead to more extensive discussions and varied perspectives, potentially elongating the defence.

- Committee Engagement: The level of engagement and probing by committee members can influence the overall duration. In-depth discussions or debates may extend the defence time.

- Cultural Norms: In some countries, the oral defence might be more ceremonial, with less emphasis on intense questioning. In others, a rigorous and extended defence might be the norm.

- Evaluation Practices: Different academic systems have varying evaluation criteria, which can impact the duration of the defence.

- Institutional Guidelines: Some institutions may have specific guidelines on defence durations, influencing the overall time allotted for the process.

Candidates should be well-prepared for a defence of any duration. Adequate preparation not only involves a concise presentation of the research but also anticipates potential questions and engages in thoughtful discussions. Additionally, candidates should be flexible and responsive to the dynamics of the defense, adapting to the pace set by the committee.

Success Factors in a PhD Defence

- Successful defence begins with a deep and comprehensive understanding of the research. Candidates should be well-versed in every aspect of their study, from the theoretical framework to the methodology and findings.

- Thorough preparation involves anticipating potential questions from the examination committee. Candidates should consider the strengths and limitations of their research and be ready to address queries related to methodology, data analysis, and theoretical underpinnings.

- Conducting mock defences with peers or mentors can be invaluable. It helps refine the presentation, exposes potential areas of weakness, and provides an opportunity to practice responding to challenging questions.

- Actively listen to questions without interruption. Understanding the nuances of each question is crucial for providing precise and relevant responses.

- Responses should be clear, concise, and directly address the question. Avoid unnecessary jargon, and strive to convey complex concepts in a manner that is accessible to the entire committee.

- It’s acceptable not to have all the answers. If faced with a question that stumps you, acknowledge it honestly. Expressing a willingness to explore the topic further demonstrates intellectual humility.

- Use questions as opportunities to reinforce key messages from the research. Skillfully link responses back to the core contributions of the study, emphasizing its significance.

- Rehearse the presentation multiple times to build familiarity with the material. This enhances confidence, reduces nervousness, and ensures a smooth and engaging delivery.

- Maintain confident and open body language. Stand tall, make eye contact, and use gestures judiciously. A composed demeanour contributes to a positive impression.

- Acknowledge and manage nervousness. It’s natural to feel some anxiety, but channelling that energy into enthusiasm for presenting your research can turn nervousness into a positive force.

- Engage with the committee through a dynamic and interactive presentation. Invite questions during the presentation to create a more conversational atmosphere.

- Utilize visual aids effectively. Slides or other visual elements should complement the spoken presentation, reinforcing key points without overwhelming the audience.

- View the defence not only as an evaluation but also as an opportunity for continuous improvement. Feedback received during the defence can inform future research endeavours and scholarly pursuits.

In essence, success in a PhD defence hinges on meticulous preparation, adept handling of questions, and projecting confidence and composure during the presentation. A well-prepared and resilient candidate is better positioned to navigate the challenges of the defence, transforming it from a moment of evaluation into an affirmation of scholarly achievement.

Failure in PhD Defence

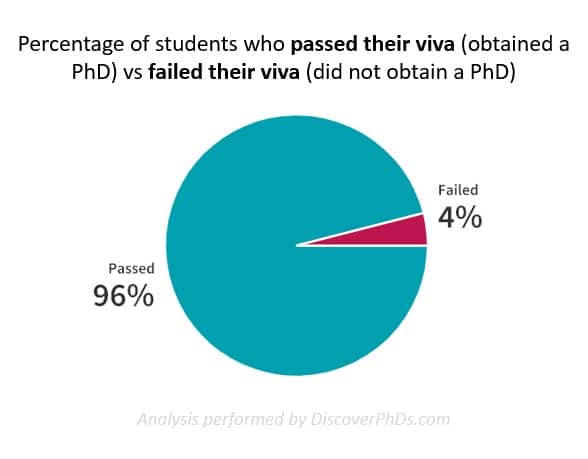

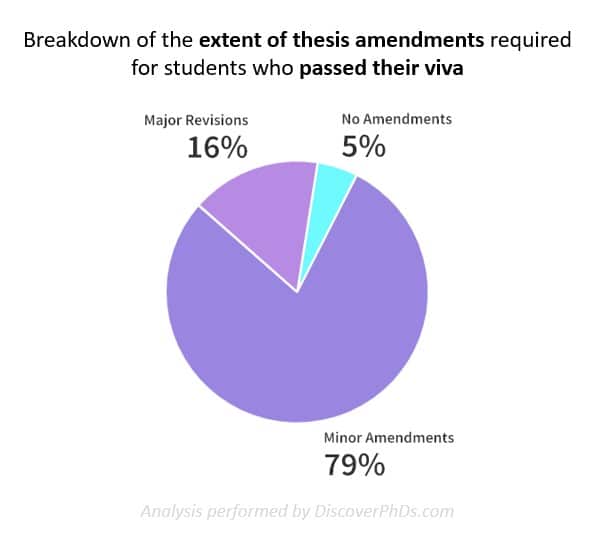

- While the prospect of failing a PhD defence is relatively rare, it’s essential for candidates to acknowledge that the possibility exists. Understanding this reality can motivate diligent preparation and a proactive approach to mitigate potential risks.

- Failure, if it occurs, should be seen as a learning opportunity rather than a definitive endpoint. It may highlight areas for improvement and offer insights into refining the research and presentation.

- Lack of thorough preparation, including a weak grasp of the research content, inadequate rehearsal, and failure to anticipate potential questions, can contribute to failure.

- Inability to effectively defend the chosen research methodology, including justifying its appropriateness and demonstrating its rigour, can be a critical factor.

- Failing to clearly articulate the original contributions of the research and its significance to the field may lead to a negative assessment.

- Responding defensively to questions, exhibiting a lack of openness to critique, or being unwilling to acknowledge limitations can impact the overall impression.

- Inability to address committee concerns or incorporate constructive feedback received during the defense may contribute to a negative outcome.

- Comprehensive preparation is the cornerstone of success. Candidates should dedicate ample time to understanding every facet of their research, conducting mock defences, and seeking feedback.

- Identify potential weaknesses in the research and address them proactively. Being aware of limitations and articulating plans for addressing them in future work demonstrates foresight.

- Engage with mentors, peers, or advisors before the defence. Solicit constructive feedback on both the content and delivery of the presentation to refine and strengthen the defence.

- Develop strategies to manage stress and nervousness. Techniques such as mindfulness, deep breathing, or visualization can be effective in maintaining composure during the defence.

- Conduct a pre-defense review of all materials, ensuring that the presentation aligns with the dissertation and that visual aids are clear and supportive.

- Approach the defence with an open and reflective attitude. Embrace critique as an opportunity for improvement rather than as a personal affront.

- Clarify expectations with the examination committee beforehand. Understanding the committee’s focus areas and preferences can guide preparation efforts.

- In the event of failure, candidates should approach the situation with resilience. Seek feedback from the committee, understand the reasons for the outcome, and use the experience as a springboard for improvement.

In summary, while the prospect of failing a PhD defence is uncommon, acknowledging its possibility and taking proactive steps to mitigate risks are crucial elements of a well-rounded defence strategy. By addressing common failure factors through thorough preparation, openness to critique, and a resilient attitude, candidates can increase their chances of a successful defence outcome.

PhD Defense or Defence?

- The choice between “defense” and “defence” is primarily a matter of British English versus American English spelling conventions. “Defense” is the preferred spelling in American English, while “defence” is the British English spelling.

- In the global academic community, both spellings are generally understood and accepted. However, the choice of spelling may be influenced by the academic institution’s language conventions or the preferences of individual scholars.

- Academic institutions may have specific guidelines regarding language conventions, and candidates are often expected to adhere to the institution’s preferred spelling.

- Candidates may also consider the preferences of their advisors or committee members. If there is a consistent spelling convention used within the academic department, it is advisable to align with those preferences.

- Consideration should be given to the spelling conventions of scholarly journals in the candidate’s field. If intending to publish research stemming from the dissertation, aligning with the conventions of target journals is prudent.

- If the defense presentation or dissertation will be shared with an international audience, using a more universally recognized spelling (such as “defense”) may be preferred to ensure clarity and accessibility.

- Regardless of the chosen spelling, it’s crucial to maintain consistency throughout the document. Mixing spellings can distract from the content and may be perceived as an oversight.

- In oral presentations and written correspondence related to the defence, including emails, it’s advisable to maintain consistency with the chosen spelling to present a professional and polished image.

- Recognizing that language conventions can vary, candidates should approach the choice of spelling with flexibility. Being adaptable to the preferences of the academic context and demonstrating an awareness of regional variations reflects a nuanced understanding of language usage.

- With the increasing globalization of academia, an awareness of language variations becomes essential. Scholars often collaborate across borders, and an inclusive approach to language conventions contributes to effective communication and collaboration.

In summary, the choice between “PhD defense” and “PhD defence” boils down to regional language conventions and institutional preferences. Maintaining consistency, being mindful of the target audience, and adapting to the expectations of the academic community contribute to a polished and professional presentation, whether in written documents or oral defences.

Is PhD Defense a Formality?

- While the PhD defence is a structured and ritualistic event, it is far from being a mere formality. It is a critical and substantive part of the doctoral journey, designed to rigorously evaluate the candidate’s research contributions, understanding of the field, and ability to engage in scholarly discourse.

- The defence is not a checkbox to be marked but rather a dynamic process where the candidate’s research is evaluated for its scholarly merit. The committee scrutinizes the originality, significance, and methodology of the research, aiming to ensure it meets the standards of advanced academic work.

- Far from a passive or purely ceremonial event, the defence involves active engagement between the candidate and the examination committee. Questions, discussions, and debates are integral components that enrich the scholarly exchange during the defence.

- The defence serves as a platform for the candidate to demonstrate the originality of their research. Committee members assess the novelty of the contributions, ensuring that the work adds value to the existing body of knowledge.

- Beyond the content, the defence evaluates the methodological rigour of the research. Committee members assess whether the chosen methodology is appropriate, well-executed, and contributes to the validity of the findings.

- Successful completion of the defence affirms the candidate’s ability to contribute meaningfully to the academic discourse in their field. It is an endorsement of the candidate’s position as a knowledgeable and respected scholar.

- The defence process acts as a quality assurance mechanism in academia. It ensures that individuals awarded a doctoral degree have undergone a thorough and rigorous evaluation, upholding the standards of excellence in research and scholarly inquiry.

- Institutions have specific criteria and standards for awarding a PhD. The defence process aligns with these institutional and academic standards, providing a consistent and transparent mechanism for evaluating candidates.

- Successful completion of the defence is a pivotal moment that marks the transition from a doctoral candidate to a recognized scholar. It opens doors to further contributions, collaborations, and opportunities within the academic community.

- Research presented during the defence often forms the basis for future publications. The validation received in the defence enhances the credibility of the research, facilitating its dissemination and impact within the academic community.

- Beyond the academic realm, a successfully defended PhD is a key credential for professional advancement. It enhances one’s standing in the broader professional landscape, opening doors to research positions, teaching opportunities, and leadership roles.

In essence, the PhD defence is a rigorous and meaningful process that goes beyond formalities, playing a crucial role in affirming the academic merit of a candidate’s research and marking the culmination of their journey toward scholarly recognition.

Dressing for Success: PhD Defense Outfit

- For Men: A well-fitted suit in neutral colours (black, navy, grey), a collared dress shirt, a tie, and formal dress shoes.

- For Women: A tailored suit, a blouse or button-down shirt, and closed-toe dress shoes.

- Dress codes can vary based on cultural expectations. It’s advisable to be aware of any cultural nuances within the academic institution and to adapt attire accordingly.

- With the rise of virtual defenses, considerations for attire remain relevant. Even in online settings, dressing professionally contributes to a polished and serious demeanor. Virtual attire can mirror what one would wear in-person, focusing on the upper body visible on camera.

- The attire chosen for a PhD defense contributes to the first impression that a candidate makes on the examination committee. A professional and polished appearance sets a positive tone for the defense.

- Dressing appropriately reflects respect for the gravity of the occasion. It acknowledges the significance of the defense as a formal evaluation of one’s scholarly contributions.

- Wearing professional attire can contribute to a boost in confidence. When individuals feel well-dressed and put-together, it can positively impact their mindset and overall presentation.

- The PhD defense is a serious academic event, and dressing professionally fosters an atmosphere of seriousness and commitment to the scholarly process. It aligns with the respect one accords to academic traditions.

- Institutional norms may influence dress expectations. Some academic institutions may have specific guidelines regarding attire for formal events, and candidates should be aware of and adhere to these norms.

- While adhering to the formality expected in academic settings, individuals can also express their personal style within the bounds of professionalism. It’s about finding a balance between institutional expectations and personal comfort.

- Select and prepare the outfit well in advance to avoid last-minute stress. Ensure that the attire is clean, well-ironed, and in good condition.

- Accessories such as ties, scarves, or jewelry should complement the outfit. However, it’s advisable to keep accessories subtle to maintain a professional appearance.

- While dressing professionally, prioritize comfort. PhD defenses can be mentally demanding, and comfortable attire can contribute to a more confident and composed demeanor.

- Pay attention to grooming, including personal hygiene and haircare. A well-groomed appearance contributes to an overall polished look.

- Start preparation well in advance of the defense date. Know your research inside out, anticipate potential questions, and be ready to discuss the nuances of your methodology, findings, and contributions.

- Conduct mock defenses with peers, mentors, or colleagues. Mock defenses provide an opportunity to receive constructive feedback, practice responses to potential questions, and refine your presentation.

- Strike a balance between confidence and humility. Confidence in presenting your research is essential, but being open to acknowledging limitations and areas for improvement demonstrates intellectual honesty.

- Actively engage with the examination committee during the defense. Listen carefully to questions, respond thoughtfully, and view the defense as a scholarly exchange rather than a mere formality.

- Understand the expertise and backgrounds of the committee members. Tailor your presentation and responses to align with the interests and expectations of your specific audience.

- Practice time management during your presentation. Ensure that you allocate sufficient time to cover key aspects of your research, leaving ample time for questions and discussions.

- It’s normal to feel nervous, but practicing mindfulness and staying calm under pressure is crucial. Take deep breaths, maintain eye contact, and focus on delivering a clear and composed presentation.

- Have a plan for post-defense activities. Whether it’s revisions to the dissertation, publications, or future research endeavors, having a roadmap for what comes next demonstrates foresight and commitment to ongoing scholarly contributions.

- After successfully defending, individuals often emphasize the importance of taking time to reflect on the entire doctoral journey. Acknowledge personal and academic growth, celebrate achievements, and use the experience to inform future scholarly pursuits.

In summary, learning from the experiences of others who have successfully defended offers a wealth of practical wisdom. These insights, combined with thoughtful preparation and a proactive approach, contribute to a successful and fulfilling defense experience.

You have plenty of career options after completing a PhD. For more details, visit my blog posts:

7 Essential Steps for Building a Robust Research Portfolio

Exciting Career Opportunities for PhD Researchers and Research Scholars

Freelance Writing or Editing Opportunities for Researchers A Comprehensive Guide

Research Consultancy: An Alternate Career for Researchers

The Insider’s Guide to Becoming a Patent Agent: Opportunities, Requirements, and Challenges

The journey from a curious researcher to a recognized scholar culminates in the PhD defence—an intellectual odyssey marked by dedication, resilience, and a relentless pursuit of knowledge. As we navigate the intricacies of this pivotal event, it becomes evident that the PhD defence is far more than a ceremonial rite; it is a substantive evaluation that validates the contributions of a researcher to the academic landscape.

Upcoming Events

- Visit the Upcoming International Conferences at Exotic Travel Destinations with Travel Plan

- Visit for Research Internships Worldwide

Recent Posts

- Best 5 Journals for Quick Review and High Impact in August 2024

- 05 Quick Review, High Impact, Best Research Journals for Submissions for July 2024

- Top Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Research Paper

- Average Stipend for Research/Academic Internships

- These Institutes Offer Remote Research/Academic Internships

- All Blog Posts

- Research Career

- Research Conference

- Research Internship

- Research Journal

- Research Tools

- Uncategorized

- Research Conferences

- Research Journals

- Research Grants

- Internships

- Research Internships

- Email Templates

- Conferences

- Blog Partners

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Research Voyage

Design by ThemesDNA.com

- Career Advice

How to Avoid Failing Your Ph.D. Dissertation

By Daniel Sokol

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istock.com/erhui1979

I am a barrister in London who specializes in helping doctoral students who have failed their Ph.D.s. Few people will have had the dubious privilege of seeing as many unsuccessful Ph.D. dissertations and reading as many scathing reports by examination committees. Here are common reasons why students who submit their Ph.D.s fail, with advice on how to avoid such pitfalls. The lessons apply to the United States and the United Kingdom.

Lack of critical reflection. Probably the most common reason for failing a Ph.D. dissertation is a lack of critical analysis. A typical observation of the examination committee is, “The thesis is generally descriptive and a more analytical approach is required.”

For doctoral work, students must engage critically with the subject matter, not just set out what other scholars have said or done. If not, the thesis will not be original. It will not add anything of substance to the field and will fail.

Doctoral students should adopt a reflexive approach to their work. Why have I chosen this methodology? What are the flaws or limitations of this or that author’s argument? Can I make interesting comparisons between this and something else? Those who struggle with this aspect should ask their supervisors for advice on how to inject some analytic sophistication to their thesis.

Lack of coherence. Other common observations are of the type: “The argument running through the thesis needs to be more coherent” or “The thesis is poorly organized and put together without any apparent logic.”

The thesis should be seen as one coherent whole. It cannot be a series of self-contained chapters stitched together haphazardly. Students should spend considerable time at the outset of their dissertation thinking about structure, both at the macro level of the entire thesis and the micro level of the chapter. It is a good idea to look at other Ph.D. theses and monographs to get a sense of what constitutes a logical structure.

Poor presentation. The majority of failed Ph.D. dissertations are sloppily presented. They contain typos, grammatical mistakes, referencing errors and inconsistencies in presentation. Looking at some committee reports randomly, I note the following comments:

- “The thesis is poorly written.”

- “That previous section is long, badly written and lacks structure.”

- “The author cannot formulate his thoughts or explain his reasons. It is very hard to understand a good part of the thesis.”

- “Ensure that the standard of written English is consistent with the standard expected of a Ph.D. thesis.”

- “The language used is simplistic and does not reflect the standard of writing expected at Ph.D. level.”

For committee members, who are paid a fixed and pitiful sum to examine the work, few things are as off-putting as a poorly written dissertation. Errors of language slow the reading speed and can frustrate or irritate committee members. At worst, they can lead them to miss or misinterpret an argument.

Students should consider using a professional proofreader to read the thesis, if permitted by the university’s regulations. But that still is no guarantee of an error-free thesis. Even after the proofreader has returned the manuscript, students should read and reread the work in its entirety.

When I was completing my Ph.D., I read my dissertation so often that the mere sight of it made me nauseous. Each time, I would spot a typo or tweak a sentence, removing a superfluous word or clarifying an ambiguous passage. My meticulous approach was rewarded when one committee member said in the oral examination that it was the best-written dissertation he had ever read. This was nothing to do with skill or an innate writing ability but tedious, repetitive revision.

Failure to make required changes. It is rare for students to fail to obtain their Ph.D. outright at the oral examination. Usually, the student is granted an opportunity to resubmit their dissertation after making corrections.

Students often submit their revised thesis together with a document explaining how they implemented the committee’s recommendations. And they often believe, wrongly, that this document is proof that they have incorporated the requisite changes and that they should be awarded a Ph.D.

In fact, the committee may feel that the changes do not go far enough or that they reveal further misunderstandings or deficiencies. Here are some real observations by dissertation committees:

- “The added discussion section is confusing. The only thing that has improved is the attempt to provide a little more analysis of the experimental data.”

- “The author has tried to address the issues identified by the committee, but there is little improvement in the thesis.”

In short, students who fail their Ph.D. dissertations make changes that are superficial or misconceived. Some revised theses end up worse than the original submission.

Students must incorporate changes in the way that the committee members had in mind. If what is required is unclear, students can usually seek clarification through their supervisors.

In the nine years I have spent helping Ph.D. students with their appeals, I have found that whatever the subject matter of the thesis, the above criticisms appear time and time again in committee reports. They are signs of a poor Ph.D.

Wise students should ask themselves these questions prior to submission of the dissertation:

- Is the work sufficiently critical/analytical, or is it mainly descriptive?

- Is it coherent and well structured?

- Does the thesis look good and read well?

- If a resubmission, have I made the changes that the examination committee had in mind?

Once students are satisfied that the answer to each question is yes, they should ask their supervisors the same questions.

Academic Success Tip: Credit Predictor Tool Helps Award Credit for Prior Learning

Davenport University in Michigan added a feature to help current and potential students identify how their experience

Share This Article

More from career advice.

How to Mitigate Bias and Hire the Best People

Patrick Arens shares an approach to reviewing candidates that helps you select those most suited to do the job rather

The Warning Signs of Academic Layoffs

Ryan Anderson advises on how to tell if your institution is gearing up for them and how you can prepare and protect y

Legislation Isn’t All That Negatively Impacts DEI Practitioners

Many experience incivility, bullying, belittling and a disregard for their views and feelings on their own campuses,

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

What Took Them So Long? Explaining PhD Delays among Doctoral Candidates

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Methods and Statistics, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, Optentia Research Focus Area, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

Affiliations Institute for Social Science Research, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Affiliation Education and Child Studies, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

Affiliations Netherlands Centre for Graduate and Research Schools, Utrecht, The Netherlands, Tilburg Law School, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands

- Rens van de Schoot,

- Mara A. Yerkes,

- Jolien M. Mouw,

- Hans Sonneveld

- Published: July 23, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839

- Reader Comments

A delay in PhD completion, while likely undesirable for PhD candidates, can also be detrimental to universities if and when PhD delay leads to attrition/termination. Termination of the PhD trajectory can lead to individual stress, a loss of valuable time and resources invested in the candidate and can also mean a loss of competitive advantage. Using data from two studies of doctoral candidates in the Netherlands, we take a closer look at PhD duration and delay in doctoral completion. Specifically, we address the question: Is it possible to predict which PhD candidates will experience delays in the completion of their doctorate degree? If so, it might be possible to take steps to shorten or even prevent delay, thereby helping to enhance university competitiveness. Moreover, we discuss practical do's and don'ts for universities and graduate schools to minimize delays.

Citation: van de Schoot R, Yerkes MA, Mouw JM, Sonneveld H (2013) What Took Them So Long? Explaining PhD Delays among Doctoral Candidates. PLoS ONE 8(7): e68839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839

Editor: Matteo Convertino, University of Florida, United States of America

Received: February 15, 2013; Accepted: June 3, 2013; Published: July 23, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 van de Schoot et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The data collection for the first project was financed by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and IVLOS at Utrecht University. The data collection for the second project was financed by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). This research was made possible in part by a grant the first author received from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research: NWO-VENI-451-11-008. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Universities across the globe are increasingly focused on how to be competitive in global and national rankings, and are often looking for ways to improve research and teaching efforts. The role of PhD candidates is extremely important in this regard as they can potentially produce a large amount of scientific output, a factor crucial in most ranking systems. The Shanghai Ranking, one of the most recognized academic ranking systems, ranks universities in part based on the number of successful PhD completions. A delay in PhD completion, while likely undesirable for PhD candidates, can also be detrimental to universities if PhD delay leads to attrition (i.e. termination of the PhD trajectory). PhD termination can lead to individual stress, a loss of valuable time and resources because of all the training and supervision invested in the candidate [1] , and can also mean a loss of competitive advantage [2] .

While many countries maintain a notional PhD duration of three or four years [3] , in reality, PhD candidates often take much longer to complete their doctoral studies. Using data from two studies of doctoral candidates in the Netherlands, we take a closer look at PhD duration and delay in doctoral completion. Specifically, we address the question: Is it possible to predict which PhD candidates will experience delays in the completion of their doctoral degree? If this is possible, then it is also possible to take steps to shorten or even prevent delay, thereby helping to enhance university competitiveness.

PhD completion in The Netherlands

The Dutch system of doctoral education has a number of characteristics specific to the Dutch context [4] . One important characteristic in relation to PhD completion and delay is the structure of funding and time given to PhD candidates to complete the PhD. Most PhD candidates are employed by the university for a set period of time to complete a PhD. The funding for these positions within the university often stems directly or indirectly from an external source, such as a research grant. As such, PhD projects consist primarily of a pre-specified trajectory of anywhere between three and five years. One consequence of this structure is that the contract duration for the PhD is set prior to a candidate starting a doctoral trajectory. Therefore, PhD candidates have no influence on the duration of the contract. Exceptions to this can only occur in special cases of delay, for example delay due to maternity leave or extended illness, or if a PhD candidate requests a decrease in working hours, which is a legislative right in the Netherlands. Individuals who have worked for their employer for 12 months or longer have a right to request an increase or decrease in working hours. If a business wishes to refuse such a request, the burden of proof is on employers to prove that granting the request would be harmful to the business. In these cases, the contract is likely to be extended pro rata to the time taken off work or the reduction in working hours.

It should be noted that the set time limit of the Dutch system does not mean PhD candidates cannot continue to work on the PhD thesis or graduate after the contract finishes. Rather, the set time limit refers to the period of time during which a candidate receives funding and can work (almost) full-time on the PhD thesis. Beyond this period, the candidate is responsible for finishing the thesis in his/her own time, which can lead to further delay. An advantage of this system is that PhD candidates have a period of guaranteed funding, during which they have the capacity to undertake field work, carry out research, and write, with minimal teaching obligations. While PhD candidates in the Netherlands may experience delays throughout the PhD trajectory, either within or beyond this set time period, these delays will most likely not be due to an absence of funding or the necessity of other professional work to finance one's PhD trajectory (for example teaching assistantships). This may not be the case with delays experienced by PhD candidates in other countries, such as the United States, where funding for doctoral research differs. What these different delays (financial, research-oriented, and supervisory) mean for PhD candidates and their success, and how this differs across countries, remains an important issue for further research.

Another characteristic of the Dutch system is that most PhD students are paid by way of the university as regular employees with a set salary level (set by collective agreement). While this is the case for most PhD candidates, it is not true for all of them. In the Netherlands, it is possible to differentiate between three different types of PhD status, including: (a) PhD candidates employed by the university (on the basis of university funding or external funding, such as funding from the national science foundation or third (private) parties), (b) scholarship recipients, and (c) external and/or dual PhD candidates. The first form is the exception and not the rule in most doctoral education programs in industrialized countries. The co-existence of multiple types of doctoral candidates is not unique to the Netherlands, however. Germany, Finland and Turkey also have doctoral systems where various types of PhD candidates co-exist, including PhD candidates employed by universities, scholarship recipients and external candidates who combine doctoral work with professional activities in other organizations [5] . What is unique about the Dutch system, however, is the high proportion of PhD candidates who are paid to work full-time or nearly full-time (0.8 FTE) on their research and PhD thesis. As noted above, a major advantage of this system is that by providing PhD candidates with a stable funding source, PhD candidates are often successful in completing the doctoral trajectory within the pre-set time period [6] . The average completion rate in the Netherlands, in general, is around 75 per cent. The existence of such a system is also useful for understanding PhD delay, a point we address below.

While the Dutch system provides most PhD candidates with a stable funding source, these external funding sources generally do not provide for the coverage of salary costs associated with an extension of a PhD contract. Therefore, any delay in the PhD trajectory in terms of salary costs has to be paid for by an academic department or institute. Alternatively, the PhD student must finish the thesis in his/her private time without drawing a salary from the university. Financially, delays can be costly for academic departments and are highly undesirable. If universities are not willing to cover the cost of an extension of the contract and a PhD candidate must finish the thesis in his/her own time, the risk increases that the thesis will not be completed [7] . In essence, the greater the duration of PhD delay, the greater the likelihood that a thesis may never be completed. Failure to complete the thesis translates into a significant loss in research investment and lost revenue for universities. In the Dutch case, this can also mean a significant financial loss because universities are rewarded financially by the government for PhD completions (€90,000 per successfully defended thesis).

Predictors of PhD-delay

While most other studies investigating variation in PhD completion typically focus on describing causes of (high) attrition rates [8] , predicting the timing of completion [2] , [9] , and/or time-to-degree [10] , [11] given the structure of the Dutch system we are able to measure the ‘true’ rate of delay. Rather than merely attempting to predict the timing and duration of PhD completion and/or time-to-degree, the structure of the Dutch system means we know a priori how long a PhD should take (expected duration) versus the actual duration. The expected duration is equal to the pre-determined end date minus the pre-determined starting date, whereas the actual duration is equal to the actual end date minus the actual starting date. The difference between these two is what we call ‘delay’. This measurement of the true rate of delay means we can focus on which factors predict PhD delay. Explanations for variation in PhD completion rates and/or time-to-degree can be sought in a number of areas and are often difficult to disentangle, but can be generalized into three categories [6] , [8] , [9] , [11] – [16] :

- Institutional or environmental factors , including field of study, departmental research climate, and resources and facilities available to the project;

- The nature and quality of supervision , entailing both the frequency of meetings as well as the support of research colleagues;

- Characteristics of the PhD candidate : including gender, ethnicity, age, having children, marital status, satisfaction with the project, academic achievement, and expectations about the project. In addition, certain personality traits, such as patience, a willingness to work hard, motivation and self-confidence have also been shown to influence PhD completion rates, but accounting for variation in these traits is beyond the scope of the research design here.

Factors most important in determining delay vary across university settings but some key warning signs, as noted by [17] , are:

- constant changes to the research topic;

- avoiding communication with the supervisor;

- PhD candidates isolating themselves;

- avoiding submitting work for review.

The above findings have, to our knowledge, never been included in a single quantitative study, which we ascribe to do here.

Before discussing the data and methodology, we call attention to one possible factor of interest: gender. Recent educational statistics show that women are increasingly taking part in higher education, including doctoral education [18] . Whereas a previous study conducted in the Netherlands in 1995 found that one fifth of PhD candidates were female [19] , a more recent study conducted in 2008–09 shows that this percentage has more than doubled to 47 per cent [20] . The effect of gender on the duration of the PhD trajectory is, however, disputed. While some studies find gender differences [21] , others do not [15] , [22] . Some studies report a positive relationship between being married or having children and delays in PhD completion for women [8] , however others suggest the effects of being married and having children are usually larger for men, as the behavioural changes accompanying marriage and parenthood are smaller for women than for men [23] . A recent article in Nature confirms the contradictions evident in research that investigates gender differences in relation to the PhD trajectory [24] . We address this issue by predicting PhD delay separately for male and female PhD candidates.

In the current paper we use data from two separate but related studies. While these studies are drawn from different populations and use various methods, they allow for a closer examination of PhD duration and delay in the Netherlands. We discuss the generalizability and possible limitations of these studies in our conclusions. The first dataset stems from a survey of doctoral recipients who completed their PhD in 2008–2009. Using these data we a) describe the occurrence of PhD delay and b) build a statistical model to predict which PhD candidates are likely to be delayed. The second dataset consists of PhD candidates surveyed in The Netherlands at Utrecht University in the final year of their PhD. These candidates were asked whether they expected to complete their PhD on time. Candidates expecting to be delayed were asked about possible reasons for this delay, including a number of open-ended questions. Data from this study allow us an opportunity to contextualize delays in PhD completion experienced by doctoral candidates. We provide a further discussion of the data and methodology for each study and turn to the results of each of these studies below.

It should be noted that the research discussed here has not been subjected to an ethics approval process. While obtaining ethics approval is standard practice in most Anglo-American systems, this is not (yet) the case for most social science research in the Netherlands. In our case, no approval by an ethical review committee was obtained because the planned surveys with adult academics are neither physically nor emotionally burdensome nor do they violate respondents' privacy. We did obtain consent from each of the local executive boards at participating universities, however, and the research was undertaken with the utmost care. This includes, but is not limited to, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of respondents, explaining the research process to participants and minimizing the demands placed on respondents by using well-tested survey instruments. Research was not undertaken outside the country of residence, therefore no local authorities were contacted. The research was not conducted in relation to any medical facility. The quantitative and qualitative data presented here are not publicly available. However, a copy of the fully-anonymized quantitative dataset is available from the first author upon request.

Methods Study 1: PhD Duration and Completion

Participants.

The first study relies on survey data on Dutch doctoral recipients gathered between February 2008 and June 2009 (response rate 50.7%; n = 565; 47% female; 73.8% were of Dutch origin) in the Netherlands at four universities (Delft University of Technology, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Utrecht University, and Wageningen University and Research Centre). For more details see [25] .

Of the 565 respondents surveyed, the majority (71.1%) reported that their formal PhD status was ‘employee’ at a university with five per cent listing ‘scholarship recipient’ as their main PhD status. The share of external or dual PhD candidates was 23.9 per cent. In the current paper we focus solely on those respondents who reported their start and end date, and who reported their status as being an employee (n = 308) or scholarship recipient (n = 25), of which 48 per cent were female. This decision is based on the transparency of these PhD trajectories. PhD candidates employed by the university and scholarship recipients have unambiguous start and end dates and these candidates primarily work full-time on their PhD thesis, allowing for a clear look at PhD delay. The group of PhD candidates not employed by the university is highly heterogeneous, which makes it difficult to assess delay clearly. There were no significant differences on key background variables between respondents included/excluded from our study. The total sample size used for the analyses is therefore n = 301 and a summary of descriptive statistics on this sample can be found in Table 1 . Note that we also deleted two outliers because they reported unrealistic values for the gap between actual and completed project time, namely -31 (completed the PhD 31 months sooner than expected) and 91 (completed the PhD 91 months later than expected). We conducted the final analyses with and without these two cases and although some numerical differences appeared, our conclusions remained the same.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839.t001

All PhD candidates who applied for permission to defend their thesis were invited to participate in the survey. Respondents were contacted through the Registrar's office (the pedel) , the university office in charge of organising the doctoral defence, at each of the participating universities. Note that in the Netherlands the so-called ‘all-but-dissertation’ (ABD) status does not exist, and registering for the defence is only allowed after official approval of the doctoral thesis by the defence (examination) committee. Outside of exceptional cases such as fraud, the degree will be conferred following a primarily ceremonial defence. When PhD candidates registered for their defence, they received an informational packet, which included a letter from the university Board of Governors ( College van Bestuur ) explaining the aim and objectives of this research project and asking for their participation. The Netherlands Centre for Graduate and Research Schools was then provided with a list of e-mail addresses of PhD candidates who registered for the defence at each university. Respondents were approached within 10–14 days after registering for graduation and were provided a login and password to complete the survey. Up to two reminder emails were sent if a respondent did not sign in to complete the survey. In sum, respondents received a maximum of three e-mails asking them to participate. Any identifying information has been removed from the data for purposes of confidentiality.

We asked the participants to provide information on certain background characteristics such as age, gender, citizenship (whether or not they were born in the Netherlands and/or have a Dutch passport), marital status (including cohabitation), both as a static category and whether their marital status changed during the PhD trajectory, and whether there are any children under the age of 18 living in the household. Furthermore, we asked them questions about any major changes occurring during the PhD trajectory. These changes included: [Did you change']… ‘[…] your main supervisor?’ '[…] daily supervisor?’ ‘[…] the institute or graduate school where you were completing the PhD?’, and ‘Did you change your thesis topic?’ In addition, respondents were asked about their publication record, including the number of submitted and accepted articles as well as conference visits. We then asked about perceived expectations from supervisors, including the expected number of journal articles, book chapters, conference papers, conference visits, etc. Finally, we asked respondents to reply to 15 statements about their supervisor and the academic climate in their department. Answers were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. One example of these statements is ‘Prior to the start of the second year of my PhD trajectory, I had a clear idea which data I would need to answer my research questions’. All 15 statements can be found in Table 1 . Each of these predicting variables was added to the model in one step. In addition, we control for the relationship between age and having children by regression the variable having children on age, see also the syntax in the supplementary materials.

Statistical Analysis

As discussed above, the Dutch system is characterized by having PhD trajectories with primarily fixed durations. Consequently, a PhD project includes a pre-determined start and end date which makes it possible to compute an exact duration for the PhD, both actual and expected. In the survey, all respondents were asked to indicate the length of their contract (planned PhD duration) as well as how long it took them to complete their thesis (actual PhD duration). This information can then be used to compute the average gap between actual and planned duration, referred to as the gap .

Using the gap as our dependent variable, we can build a statistical model where we add predictors of the average gap for females and males separately. We provide the syntax of the model in the appendix (see Appendix S1 ), and the data can be requested by sending an email to the first author. We have used Bayesian statistics in the software package Mplus v7.0 [26] , [27] for all of the analyses. Mplus is a software package that can deal with many types of statistical models with continuous and categorical variables and different types of estimators, for example maximum likelihood, weighted least squares, bootstrapping and the Bayesian estimator. Bayesian statistics are becoming more common in academic research [28] . The number of papers published, for example, in the journal PLoS One with Bayes in the title or abstract has increased from only one in 2006 to 89 in 2011. The key difference between Bayesian statistics and ML-estimation concerns the nature of the unknown parameters. For example, following the frequentist framework approach to maximum likelihood estimation, a parameter of interest is assumed to be unknown, but fixed. That is, it is assumed that there is only one true population parameter in the population; for example, one true regression coefficient. In the Bayesian view of subjective probability, all unknown parameters are treated as uncertain and should therefore be described using a probability distribution. Hence, with Bayesian statistics, all parameters of the model (e.g., means, variances, regression parameters, etc.) are repeatedly estimated in an iterative process. This distribution of parameters can subsequently be used to compute the mean regression coefficient and its confidence interval. For a more detailed comparison and for an introduction to Bayesian statistics see the many textbooks on this topic, for example [29] .

In our case there are three main reasons why we have chosen to use Bayesian statistics. First, Bayesian estimation is less sensitive to the distribution of the parameters in our model because of the iterative process. This is an advantage in our case because of the highly skewed distribution of our dependent variable (see Figure 1 ). Second, in each iteration of the iterative process, missing data is automatically imputed. In our data, 75 per cent of the cases had complete data and another 20 per cent had missing data for only one or two variables. The remaining 5 per cent had missing data on multiple variables. The amount of missing data was not related to any of the variables in the model. Third, the use of Bayesian statistics results in slightly different interpretations of the results compared to maximum likelihood or a weighted least squares estimation. When Bayesian statistics are used, the confidence intervals (i.e., credibility intervals, or posterior probability intervals) are used to indicate the 95 per cent probability that the estimate will lie between the lower and upper value of the interval. When the interval does not include zero, the null hypothesis is rejected and the effect is assumed to be present.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839.g001

On a final methodological note, when analyzing statistical models, we may be interested in more than just confirming or rejecting a single hypothesis –we may want to evaluate the entire model. When using Bayesian statistics, classical model fit indices, such as the CFI, TLI, and RMSEA are not available. However, it is possible to obtain the predictive accuracy of the model (see [30] for a more detailed discussion). This evaluation of the model is also referred to as posterior predictive checking, see [31] . In Mplus, the posterior predictive p -value ( ppp-value ) is given and ppp -values around.50 indicate a good-fitting model.

Results Study 1: PhD Duration and Completion

Starting with results from our first study, the data show that female PhD recipients took an average of 59.8 months (95% CI: 57.18–61.82) to complete their PhD thesis and male PhD candidates an average of 59.67 months (95% CI: 57.46–61.91), see also Figure 2 . The average gap between actual and planned duration (i.e., the gap ) was 9.52 months for women (95% CI: 7.43–11.69) and 10.11 months for men (95% CI: 8.09–12.17), see also Figure 1 . Since the 95% CI for both variables for women and men completely overlap, no significant gender differences are found. While the duration of the gap does not differ for men and women, we do find significant differences in what causes the gap , or rather what is associated with the gap . Because our data is cross-sectional data, we cannot make assumptions about causal relationships.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839.g002

In the statistical model for female PhD candidates (n = 158), 30.0 per cent of the variance in the gap was explained and the ppp-value is.60, indicating a well-fitting model. Our results clearly show significant predictors, that is, the 95 per cent CI does not include zero, see Table 2 . For women, a change in marital status during the PhD trajectory (while controlling for the status itself) is associated with more than five months delay. In addition, having had opportunities through their supervisors to establish international contacts was associated with a three month delay. In contrast, for women, working together with other PhD candidates is associated with a four month gain in project time.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839.t002

In the statistical model for male PhD candidates (n = 173), 30.4 per cent of the variance in the gap was explained and the ppp-value is.52, also indicating a good-fitting model. In contrast to women, marital status was not associated with the gap for men, but having children is associated with almost four months delay. Moreover, for men, a change of supervisor or thesis topic was associated with a five-and-a-half month delay. Conference attendance, however, was associated with a decrease of the gap by 7 months. In addition, for men, whether the PhD candidate knew which research question to answer by the end of the first year was associated with a 3.8 month decrease in the gap.

Methods Study 2: Explaining PhD Delay

The second study relies on survey data on doctoral recipients gathered in 2010 at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, for more information see [32] . The sampling frame included all PhD candidates registered at Utrecht University. In other words, the frame consists of candidates employed by the university as well as external and dual PhD candidates (candidates who combined a PhD with another job or other activities), and scholarship-funded PhD candidates. Candidates were invited to rate various aspects of their PhD experience through an online questionnaire, including a series of open ended questions. In total, 2,870 candidates were approached and of these 2870 candidates, 1,504 (52%) completed at least one part of the survey. Similar to the previous study, most PhD candidates surveyed (79%) were employed by the university, 5% of respondents were on a PhD scholarship and external and/or dual PhD candidates (who combine a PhD with other activities) made up 12 per cent of the candidates surveyed. Nearly one third (31%) of the respondents had a non-Dutch nationality. The top three foreign nationalities included German (3%), Italian (3%) and Chinese (2%). Candidates' average age was 31. More than one–third of candidates (36%) were older than 31. Fifty-seven percent of the candidates were female and 43 percent were male.

In line with the previous study, while a survey carried out at one university in the Netherlands may not be representative of the population of PhD candidates as a whole, the data provide rich, contextual data on expectations of PhD duration and reasons for delay.

Results Study 2: Explaining PhD Delay

Using data from this second study, it was possible to determine the current stage of the PhD trajectory for 1,286 respondents: 25 per cent were in their first year, 19 per cent were in their last year, 53 per cent were somewhere in between and 3 per cent had recently graduated. When asked whether they were on track to finish their PhD thesis on time, 60.5 per cent of the PhD candidates reported they expected to finish on time, while 27.5 per cent expected difficulty in finishing on time and another 12 per cent did not know. If we select only those PhD candidates who were in the final year of their PhD, 88 out of 232 (38%) expected to experience problems in finishing on time. For the remainder of the analysis, we refer only to this group of respondents in the final year of their PhD. Not only do these candidates probably know best why they were experiencing a delay (the time to finish their PhD was quickly running out), it is also plausible that an expected delay in the first few years of the PhD trajectory may be resolved at a later stage. Due to the small sample size, we do not exclude external and/or dual PhD students from this study, whereas external and/or dual candidates are excluded from Study 1.

Respondents were asked about the reasons for the expected delay and could choose from ten answer categories, see Figure 3 . Multiple answers could be provided. Responses to this question illustrate that experiencing practical setbacks is the most common reason for a delay, followed by not adhering to the original thesis plan. In contrast to other countries like the US, Dutch PhD candidates do not wait to select a thesis topic until later in the PhD trajectory. Rather, PhD candidates start their trajectory with a clear topic and research plan laid out.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839.g003

We also asked respondents a number of open-ended questions about expected delays. The responses to these questions can be grouped into four broad themes thought to influence delay:

- Thesis-related issues , meaning additional work needed to be done ( n = 16), such as extra papers being written or statistical analyses taking longer than expected; bad planning or a change in plans, and external circumstances ( n = 15) such as waiting for donor material, waiting for ethics approval, or as one respondent replied, “experiments were affected due to renovations in the building”.

- Supervisor-related issues . For many respondents, clear guidance and communication were essential to their PhD trajectory ( n = 17). Stated differently, an absence of clear guidance and communication were seen as integral in explaining their expected delay.

- Personal issues . This includes circumstances at home (n = 15), such as care responsibilities, or more serious circumstances such as the death of a relative, a candidate suffering from severe illness; or personal difficulties in managing the project ( n = 8).

- Combination problems . These issues involved trying to combine the PhD with other duties, such as other work (n = 24); starting a new job before finishing the thesis; or as one respondent replied, needing “to spend time pleasing the grant provider.”

For many respondents, clear guidance and communication were essential to their PhD trajectory. Or rather, they perceived an absence of clear guidance and communication as fundamental in causing delay, as these two respondents discuss:

“I have been having a difficult time relating with my first project which I started with my supervisor, who moved to another institute and who doesn't pay attention to what I am doing anymore. [...] I fell in a void when my previous supervisor left, and no one noticed. It took me 1.5 years to find a new supervisor, start a project etc. That time is lost, and I do not get any (monetary) help on that point.” 4 th year PhD candidate in the Social Sciences, delayed by 6 months and still working on the thesis “My supervisor does not motivate or stimulate me scientifically or socially. He does not provide any practical supervision, nor does he ensure that a secondary supervisor does so, even when explicitly asked to do so and agreeing upon this. This has caused considerable and unnecessary delay in my project. When confronted, the supervisor denies any insufficiencies and does not show willingness to invest in improving the situation.” 4 th year PhD candidate in the Health Sciences delayed by approximately 1 year

The frustration caused by an absence of clear guidance and communication is summed up succinctly by the response of one PhD candidate who stated:

“HE'S LEFT ME ALONE”. (Emphasis in original) 4 th year PhD candidate in the Earth Sciences delayed by approximately 2 years

Answers to these open-ended questions provide interesting insights into PhD candidates' experiences and perceptions of delay. Together with the results from the first study, the data offer a starting point for developing practical tips for preventing delay. One creative and useful way of developing these tips is to apply the Machine Trick to these responses, suggested by famed sociologist Howard Becker [33] :

Take a second. Imagine that you have a spouse/partner. We ask you to tell us what your partner should do to keep you happy. You could talk for hours, mentioning dozens and dozens of examples of what the partner should or should not do. Now we apply the Machine Trick. What should your partner do to make you feel sad and unhappy as quickly as possible? Within five minutes you will be able to sum up the essential things, the opposite of which thus provides key insights into having and maintaining a happy relationship.

To understand key factors contributing to the successful completion of a PhD project, we should ask ourselves what key factors a “machine” would use to make a PhD project fail. Of course, as Becker tells us, in actuality we do not want a PhD project to fail. But utilizing such a machine-designing exercise offers a systematic means of considering which factors contribute to the failure (and conversely the success) of a PhD project.

Applying Becker's Machine Trick to our qualitative data, we can conclude that key steps likely to contribute to the failure of a PhD project include:

- Admit doctoral candidates who demonstrate the least amount of knowledge about their potential PhD topic.

- Base admission decisions on written material only – do not invite candidates for face-to-face interviews.

- Do not test the (English) language proficiency of PhD candidates from abroad.

- Restrict supervision to one supervisor who is overloaded with responsibilities, has multiple PhD candidates and offers no team supervision.

- Restrict supervision to a supervisor who does not care about PhD planning, who will meet with the candidate once every two or three months at the most and who will let the PhD candidate independently determine which criteria are applied in assessing the thesis and if/when progress will be monitored.

- Do not assess whether the candidate possesses the basic and necessary qualities for designing and completing a PhD project prior to enrolment.

- Have the candidate focus solely on reading and do not provide any training in rigorous, academic writing or any other research skills.

- Isolate the candidate: Communication with other experts or peers to discuss one's work should be avoided.

- And please, let the candidate teach for at least for three or four days a week.

These factors will guarantee a delay of the PhD candidate. While these tips may appear self-evident, few studies offer empirical evidence from the perspective of PhD candidates on which to base these recommendations. While further research is needed to test the generalizability of the results shown here, taking steps to develop policies aimed at addressing these concerns can minimize the chances of delay.

In this paper, we have taken a brief look at PhD delay. Results from the first study show significant gender differences in predicting PhD delay, confirming findings from [21] . What is associated with delay differs for men and women. For women, work and social contacts are associated with a reduction in delay, whereas for men, conference attendance and knowing precisely which research questions the candidate wants to answer at the end of the first year is associated with a decrease in delay. We also find that for women, a change in marital status (while controlling for marital status itself), and having had opportunities through their supervisors to establish international contacts are associated with delay. For men, having children younger than 18 in the household or experiencing a change of supervisor or thesis topic is associated with a delay in finishing the PhD. In part, then, our results appear to confirm findings from Waite [23] , that the effects of having children are larger for men than for women. In fact, we find no significant effect of having children under the age of 18 on the PhD delay experienced by women. The absence of a finding here could be a reflection of when women choose to have children. Mastekaasa [34] finds, for example, that there is no relationship between having children and completion rates of doctoral candidates in Norway, as long as children were born prior to commencement of a PhD program. Female doctoral candidates may make a conscious choice to delay childbearing until after PhD completion. However, more research is needed to determine the validity of such an argument.

The second study, looking in more detail at reasons for expected delays, demonstrates that practical setbacks can lead to unnecessary delays in the PhD trajectory. This may not be a surprising finding, given that practical setbacks, such as problems with data, are part of doing research more generally and the PhD experience in particular. However, an individual's ability to deal with these practical setbacks may be what separates a successful scientist from a less successful one. In addition, the open-ended responses provided by PhD candidates in the second study suggest that universities and graduate schools can work with PhD candidates to minimize these delays by:

- ensuring PhD planning takes place within a reasonable timeframe;

- by conducting structural reviews of PhD progress;

- working to ensure effective communication between candidates and supervisors;

- and providing structural support to PhD candidates, for example support for those individuals with caring duties.