Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- < Back to search results

- An Introduction to Fantasy

An Introduction to Fantasy

- Get access Buy a print copy Check if you have access via personal or institutional login Log in Register

- Matthew Sangster , University of Glasgow

- 24.99 (USD) Digital access for individuals (PDF download and/or read online) Add to cart Added to cart Digital access for individuals (PDF download and/or read online) View cart

- Export citation

- Buy a print copy

Book description

Providing an engaging and accessible introduction to the Fantasy genre in literature, media and culture, this incisive volume explores why Fantasy matters in the context of its unique affordances, its disparate pasts and its extraordinary current flourishing. It pays especial attention to Fantasy's engagements with histories and traditions, its manifestations across media and its dynamic communities. Matthew Sangster covers works ancient and modern; well-known and obscure; and ranging in scale from brief poems and stories to sprawling transmedia franchises. Chapters explore the roles Fantasy plays in negotiating the beliefs we live by; the iterative processes through which fantasies build, develop and question; the root traditions that inform and underpin modern Fantasy; how Fantasy interrogates the preconceptions of realism and Enlightenment totalisations; the practices, politics and aesthetics of world-building; and the importance of Fantasy communities for maintaining the field as a diverse and ever-changing commons.

‘Matthew Sangster offers us an entirely new way to look at fantasy and its cultural significance. Drawing on a wide range of examples, from ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight' to Dungeons and Dragons, and gracefully integrating ideas from a number of disciplines, Sangster offers a convincing account of one of the major cultural phenomena of the past century and a half.'

Brian Attebery - Emeritus Professor of English, Idaho State University

‘On all accounts, this is a wonderful book. The range of texts considered is amazing. Sangster examines written narratives, films, TV series, fan fiction, graphic narratives, comics, role-playing games, and other web manifestations of fantasy, and invokes Asian, African, and Near Eastern examples alongside Western ones. The teeming variety, and Sangster's own uniquely positive approach, support claims to the importance of fantasy in human experience and enforce the sense that collaboration and shared experience is an integral element of human interaction, and one that fantasy encourages.'

Kathryn Hume - Emerita Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English, The Pennsylvania State University

‘Matthew Sangster's modestly titled An Introduction to Fantasy is much more than an introduction to a single genre. It is a powerful meditation on a communal mode of artistic creativity that has shaped culture for thousands of years and now finds expression in textual, visual and interactive forms all across the world.'

Anna Vaninskaya - Senior Lecturer in English Literature, University of Edinburgh

‘Although it's one of the oldest modes of storytelling, fantasy has exploded in popularity over the last half-century, and critical and historical commentary about it has expanded almost as dramatically. In An Introduction to Fantasy: Imagination, Iteration and Community, Matthew Sangster demonstrates a keen understanding both of the source material—drawing not only on literature but on films, TV, gaming, and art—and of the critical discourse around it. His eminently readable study is both historically grounded as far back as Plato, and as contemporary as Kelly Link and Nghi Vo.'

Gary K. Wolfe - Emeritus Professor of Humanities, Roosevelt University

‘An insightful and engaging exploration into the broad landscape of fantasy. Brilliantly written and comprehensive, Sangster delves deftly into the signal importance of the genre throughout human history and in our fraught contemporary moment. Thought-provoking and timely, this volume belongs on every fantasist's bookshelf.’

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas - Associate Professor, Joint Program in English and Education, University of Michigan, author of The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to The Hunger Games

- Aa Reduce text

- Aa Enlarge text

Refine List

Actions for selected content:.

- View selected items

- Save to my bookmarks

- Export citations

- Download PDF (zip)

- Save to Kindle

- Save to Dropbox

- Save to Google Drive

Save content to

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to .

To save content items to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

Save Search

You can save your searches here and later view and run them again in "My saved searches".

An Introduction to Fantasy pp i-ii

- Get access Check if you have access via personal or institutional login Log in Register

An Introduction to Fantasy - Title page pp iii-iii

Copyright page pp iv-iv, contents pp v-v, figures pp vi-x, introduction pp 1-52, 1 - fantasy, language and the shaping of culture pp 53-96, 2 - the value of iteration pp 97-161, 3 - root formations pp 162-224, 4 - enlightenment and its shadows pp 225-297, 5 - fashioning worlds pp 298-373, 6 - fantastic communities and common ground pp 374-431, envoi pp 432-436, acknowledgements pp 437-438, select bibliography pp 439-458, index pp 459-470, altmetric attention score, full text views.

Full text views reflects the number of PDF downloads, PDFs sent to Google Drive, Dropbox and Kindle and HTML full text views for chapters in this book.

Book summary page views

Book summary views reflect the number of visits to the book and chapter landing pages.

* Views captured on Cambridge Core between #date#. This data will be updated every 24 hours.

Usage data cannot currently be displayed.

What Is Fantasy and Who Decides?

- First Online: 08 June 2023

Cite this chapter

- Elana Gomel 3 &

- Danielle Gurevitch 4

480 Accesses

This chapter offers a definition of the genre in terms of its positioning within a historically, linguistically, and nationally specific consensus reality.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Fast, Furious and Xerox: Punk, Fanzines and Diy Cultures in a Global World

Delany, Samuel Ray Jr.

Comparative Collapsology: From Shakespeare to George R. R. Martin

Confusingly Rayment critiques what he calls “diachronic” definitions, but these are not the same thing as the “historical” genres of Fowler. Rayment’s “diachronic” definitions are rather what we call “broad,” incorporating as many diverse texts as possible.

Compare with: Mabille, 13.

See discussion on universal Chronotopes and their interactions in Vered Weiss’ article.

The question of translation, both linguistic and cultural, is very important in this context; however, the limitations of space do not allow us to go into it in any detail, though it is raised in several essays, notably by Zhange Ni and Deimantas Valanciunas.

An observation largely discussed in Teresa P. Mira de Echeverría’s article.

https://www.tor.com/2019/12/23/to-prepare-for-the-witcher-i-read-the-book-it-didnt-help/ .

https://austsfsnapshot.wordpress.com/2016/08/07/2016-snapshot-gillian-rubinstein-lian-hearn/ .

A lecture in honor of South African Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer, titled: “At the same time: The Novelist and moral reasoning,” Cape Town and Johannesburg, March 2004; Sontag ( 2007 : 210).

Works Cited

Attebery, Brian. “The Politics (if Any) of Fantasy.” In Strategies of Fantasy . Indiana University Press, 1992.

Google Scholar

Berger, Peter L. and Luckmann, Thomas. The Social Construction of Reality . Tridico-Elsemer Press, 2003; Berger-Penguin Books, 1966.

Camus, Albert. l’étranger: Roman . Gallimard; Bibliothèque, 1942. Digital Copy at: Paul-Émile-Boulet de L’Université de Québec à Chicoutimi, 2010.

Fowler, Alastair. Kinds of Literature: An Introduction to the Theory of Genres and Modes . Clarendon Press, 2002.

Gurevitch, Danielle and Gomal, Elana (eds.) With Both Feet on the Clouds: Fantasy in Israeli Literature . Academic Studies Press, 2013.

Hume, Kathryn. Fantasy and Mimesis: Responses to Reality in Western Literature. Talor and Francis , (1984) 2014.

Irwin, W. R. The Game of the Impossible . University of Illinois, 1976.

Jackson, Rosemary. Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion . Routledge, 1981.

Book Google Scholar

James, Edward and Mendelsohn, Farah. The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature . Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Jauss, Robert Hans. Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory . Newton-Twentieth-Century Literary Theory, (1970) 1977.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Totalité et Infini: Essai sur l’extériorité . Le Livre de Poche, (1961) 1991.

Mabille, Pierre. Mirror of the Marvelous: The Surrealist Reimaging of Myth . Jody Gladding (trans.). Inner Traditions, 2018 [1962].

Mendelsson, Farah. Rhetorics of Fantasy . Welsleyan University Press, 2013. (2008).

Okorafor, Nnedi. “Writers of Colour,” in: The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature, 2012.

Patell, Cyrus. Cosmopolitanism and the Literary Imagination . Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Rayment, Andrew. Fantasy, Politics, Postmodernity . Brill, 2015.

Sontag, Susan. At The Same Time: Essays and Speeches . Farrer, Straus, and Giroux, 2007.

Todorov, Tzvetan. The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre . Cornell University Press, 2007.

Tolkien, J. R. R. Tree and Leaf . HarperCollins, 2014.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv, Israel

Elana Gomel

Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel

Danielle Gurevitch

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elana Gomel .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Gomel, E., Gurevitch, D. (2023). What Is Fantasy and Who Decides?. In: Gomel, E., Gurevitch, D. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Fantasy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26397-2_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26397-2_1

Published : 08 June 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-26396-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-26397-2

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Fantasy

I. What is Fantasy?

Fantasy , from the Greek ϕαντασία meaning ‘making visible,’ is a genre of fiction that concentrates on imaginary elements (the fantastic). This can mean magic, the supernatural, alternate worlds, superheroes, monsters, fairies, magical creatures, mythological heroes—essentially, anything that an author can imagine outside of reality. With fantasy, the magical or supernatural elements serve as the foundation of the plot, setting, characterization, or storyline in general. Nowadays, fantasy is popular across a huge range of media—film, television, comic books, games, art, and literature—but, it’s predominate and most influential place has always been in literature.

II. Examples of Fantasy

Fantasy stories can be about anything, anywhere, anytime with essentially no limitations on what is possible. A seemingly simple plotline can be made into a fantasy with just one quick moment:

Susie sat at her table with all of her favorite dolls and stuffed animals. It was afternoon tea time, and she started serving each of her pretend friends as she did every other day. But today was no ordinary day. As Susie reached the chair where she had sat her favorite stuffed bear, she suddenly had the strange feeling like someone was watching her. She stopped pouring the tea and looked up at Bear, who stared back with his glass eyes and replied, “Well Hello!!”

As can be seen, by changing one ordinary thing into something fantastic or imaginary—like a normal stuffed animal coming to life before the eyes of a child—the story turns into a fantasy.

III. Types of Fantasy

There are dozens of types and subgenres of fantasy; below are several of the most well-known and typically used.

a. Medieval

Fantasy stories that are medievalist in nature; particularly focused on topics such as King Arthur and his knights, royal court, sorcery, magic, and so on. Furthermore, they are usually set in medieval times. They often involve human protagonists facing supernatural antagonists —opponents like fire-breathing dragons, evil witches, or powerful wizards.

b. High/Epic Fantasy

Fantasy stories that are set in an imaginary world and/or are epic in nature; meaning they feature a hero on some type of quest. This subgenre became particularly popular in the 20 th century and continues to dominate much of popular fantasy today. Prime examples include J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia.

c. Fairy Tales

Short stories that involve fantasy elements and characters —like gnomes, fairies, witches, etc— who use magical powers to accomplish good and/ or evil. These tales involve princes and princesses, fairy godmothers and wicked stepmothers, helpful gnomes and tricky goblins, magical unicorns and flying dragons. Fairytales feature magical elements but are based in a real world setting; for example, “Snow White” takes place in a human kingdom and also has a magical witch. The most notable collections include Grimm’s Fairytales (Hansel and Gretel, Rapunzel) and works by Hans Christian Anderson (“The Ugly Duckling,” “The Little Mermaid”) and Charles Perrault (“Cinderella,” Tales of Mother Goose). It is also very common for stories in other genres to feature elements of fairy tales , like Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream , where humans are unaware that a fantasy world exists within their own.

d. Mythological

Fantasies that involve elements of myths and folklore, which are typically ancient in origin and often help to explain the mysteries of the universe and all of its elements—weather, the earth, the existence of creatures and things, etc—as well as historical events. The most well-known are Greek and Roman mythology; for example, stories about the Greek Gods and heroes like Hercules have been retold countless times through fantasy films. Major examples include Homer’s epic tales The Iliad and The Odyssey .

Short stories that are similar to fairy tales, but involve animated animals as the main characters . The most famous collection is Aesop’s Fables , which each end with a short moral; for example, his tale “Mercury and the Woodman” concludes with the lesson, “honesty is the best policy.”

IV. Importance of Fantasy

While fiction in general is a popular way to tell stories, fantasy’s key asset is that it allows authors to do things outside the confines of the common world. By removing the limitations of reality, fantasy opens stories to the possibility of anything . People can become superheroes, animals can speak, dragons become real dangers, and magic can be as normal as anything else in life. Most importantly, fantasy is for the audience—it allows people to escape from reality, becoming lost in exciting and unusual stories that provoke the imagination. Fantasy allows authors and audience alike to fulfill their wonders about magic and the supernatural while exploring beyond what is truly possible in our world. Furthermore, some fantasy stories (particularly fairy tales) confront real world problems and offer solutions through magic or another element of fantasy.

V. Examples of Fantasy in Literature

Fantastic stories of kings and queens, princes and princesses, knights and dragons have been entertaining people for centuries. One of the oldest and most important pieces of English literature is the epic fantasy poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight . In this medieval tale, a green knight challenges King Arthur in a match that involves each opponent taking one stroke of an axe to their neck. Below is a selection from the tale, when one of Arthur’s knights steps up to take the challenge in place of the king, and the Green Knight goes first…

The Green Knight adjusts himself on the ground, bends slightly his head, lays his long lovely locks over his crown, and lays bare his neck for the blow. Gawayne then gripped the axe, and, raising it on high, let it fall quickly upon the knight’s neck and severed the head from the body. The fair head fell from the neck to the earth, and many turned it aside with their feet as it rolled forth. The blood burst from the body, yet the knight never faltered nor fell; but boldly he started forth on stiff shanks and fiercely rushed forward, seized his head, and lifted it up quickly.

Here, we see the extent of the Green Knight’s supernatural abilities—he is decapitated by the axe and picks up his own head, otherwise seemingly unharmed. King Arthur and his knights, however, are humans, without supernatural abilities. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a classic example of a medieval fantasy featuring human protagonists and supernatural antagonists.

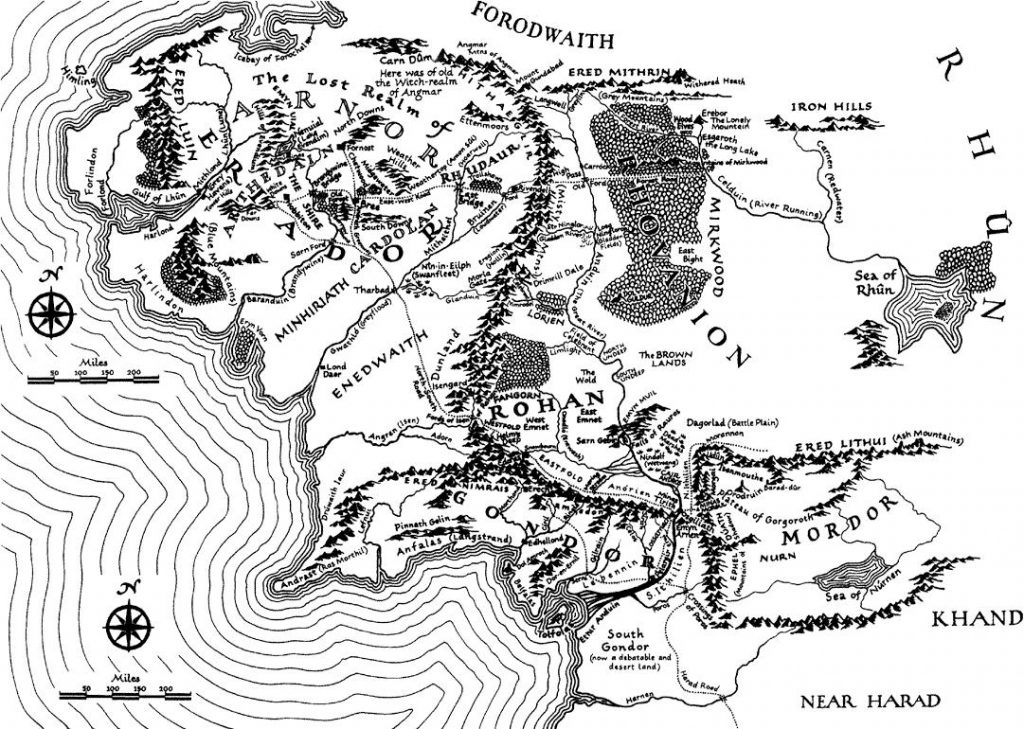

With his creation of The Hobbit and the subsequent The Lord of the Rings , J.R.R. Tolkien changed fantasy literature as the world knew it. The most influential part of his writing is the fact that the stories take place in a fantasy world—a world completely external to our own— now known as high fantasy or epic fantasy. In such a setting, elements of fantasy are a standard part of that world. Below is a map of Tolkien’s Middle Earth:

Before Tolkien, the genre of fantasy was composed of stories that took place in our world, but included fantastic elements. Middle Earth is not part of the human earth, and it is home to races, creatures, languages, histories, and folklore that were completely created by Tolkien. In his world, things we see as fantastic are natural parts of the universe he developed. Tolkien also developed a full geography, history, mythology, ancestry, and fourteen languages of Middle Earth.

A very influential set of short fantasy stories is Aesop’s Fables . Below is the well-known tale of “The Hare and the Tortoise:”

The Hare was once boasting of his speed before the other animals. “I have never yet been beaten,” said he, “when I put forth my full speed. I challenge any one here to race with me.” The Tortoise said quietly, “I accept your challenge.” “That is a good joke,” said the Hare; “I could dance round you all the way.” “Keep your boasting till you’ve won,” answered the Tortoise. “Shall we race?” So a course was fixed and a start was made. The Hare darted almost out of sight at once, but soon stopped and, to show his contempt for the Tortoise, lay down to have a nap. The Tortoise plodded on and plodded on, and when the Hare awoke from his nap, he saw the Tortoise just near the winning-post and could not run up in time to save the race. Then the Tortoise said: “Slow but steady progress wins the race.”

The fantastic element of this story is, of course, the talking tortoise and hare, and their abilities to reason like humans. Aesop’s Fables are short, memorable, and enjoyable to both children and adults alike, which is why they remain relevant thousands of years after being written. They are particularly memorable because of the moral or lesson that closes each of the stories; in this case, “slow but steady progress wins the race,” which is a familiar saying even today.

VI. Examples of Fantasy in Pop Culture

Fantasy has a particularly large presence in popular culture, much more so than most other genres. Many now-famous books and films have developed massive fan bases seemingly overnight, from fantasy classics like The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia , to modern day favorites like the Harry Potter series, the Twilight saga, and Percy Jackson and the Olympians .

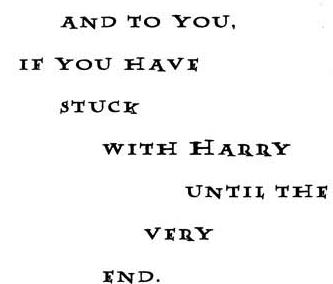

Literally sold by the billions, the most popular series of books ever written to date is J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. In fact, the size of the Harry Potter universe within popular culture is immeasurable. The fan following of these fantasy books is both historical and remarkable, as is the resulting relationship between the author and her fans. Rowling even made a special dedication to her fans with Harry’s last journey in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows :

As a result of their popularity, the seven Harry Potter books have been made into eight blockbusters (some of the most successful in cinematic history), which led to an expansive merchandise and videogame business, and then further to the opening of the Wizarding World of Harry Potter at Universal Studios—to name a few things. Furthermore, the dedication and enthusiasm of her fan base led Rowling to develop Pottermore , an online interactive world set within the storyline of the Harry Potter series, where fans can become virtual wizards and students at Hogwarts, and is still releasing content years after the publication of the final book. When it comes to fantasy in popular culture, Harry Potter is a powerhouse.

One of the most watched series on television is HBO’s Game of Thrones , based on the book series A Song of Ice and Fire by George Martin. Like J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, Game of Thrones is set in an imaginary world. These stories are unique, however, because the elements of fantasy that are part of the books—dragons, white walkers, giants, etc—are all mentioned, but are thought to have become extinct or ceased to exist years and years before. Thus, the dragons are even more magical and terrible to behold because people believe they are gone from the world.

Another series with a massive fan base is Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight . Twilight took over the market for teen fiction and was soon developed into four majorly successful films. Knowing in advance that there would be a demand, the franchise even worked with a designer to reproduce Bella Swann’s wedding dress, which became available alongside the release of the related movie. Another trend that rose from the films was “Team Edward” vs. “Team Jacob”—the battle between fans about which man Bella should be with. It took over magazines, websites, social media, clothing companies, and more.

Meyer’s books are also particularly notable because of the huge collection of “fan fiction”—stories written by fans that involve characters and/or elements of the original story—that has resulted from their publication. In fact, one fan’s fiction became so well known that it was recently published—the infamous and wildly successful “50 Shades” novels. Furthermore, the Twilight series made vampires stories “trendy”—it led to a significant rise in the popularity and production of vampire literature, film and television.

VII. Related Terms

- Science Fiction

Technically, science fiction could be considered a subgenre of fantasy, as it involves supernatural elements. However, it is always distinguished from fantasy because its focus is scientific and futuristic rather than magical and (often) medieval. The most influential science fiction stories to date are undoubtedly the George Lucas’s Star Wars films; further examples include the TV series Star Trek and novels like H.G. Wells’ The War of the World’s and Douglas Adams’ series The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy .

Like science fiction, horror could also technically be considered a subgenre of fantasy, but it is likewise always distinguished from fantasy. Horror’s main focus is to promote fear and terror in its audience, sometimes using supernatural elements like ghosts, zombies, monsters, demons, etc. Examples include classic films like The Exorcist and Poltergeist , the popular TV series The Walking Dead , and Stephen King’s horror novels like Pet Sematary.

VIII. Conclusion

In conclusion, fantasy is one of the most popular and significant genres in both popular culture and literary history. From its dozens of subgenres, to its compatibility with other genres, to its ability to be adapted into any form of media, fantasy’s influence cannot be compared to many other styles .

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Start typing to search all Word on Fire content.

Home › Articles › Why We Need Fantasy Literature

Why We Need Fantasy Literature

Dr. holly ordway, may 26, 2021.

Which books are most powerful, most evocative, most engaging for the work of evangelizing through literature? If we survey the landscape of modern literature with that question in mind, certain works of fiction form their own mountain range: Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings ; Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles and Ransom Trilogy ; George MacDonald’s Phantastes . To be sure, the works of other authors loom large in the landscape—Flannery O’Connor’s stories and novels, as one very notable example. But in my own admittedly anecdotal (albeit extensive) experience of which books are most often mentioned as being significant in readers’ journeys of faith, the pre-eminence of fantasy is notable.

Tolkien and Lewis are in the lead, undoubtedly, because they are such outstanding writers of imaginative literature: creative geniuses who, we might say, happened to choose fantasy as their preferred form. Lewis certainly shows that he is a master communicator in any genre or form that he chooses (as Steven Beebe argues convincingly in C.S. Lewis and the Craft of Communication ). But I would venture to suggest that the power of their work is not unrelated to their choice of fantasy as a literary form. This isn’t to say that fantasy as a genre is superior to other forms per se—but it’s entirely possible (indeed, I think probable) that it has particular strengths for evangelization, and particularly for “leading with beauty.”

C.S. Lewis himself wrote in Surprised by Joy that reading George MacDonald’s fantasy novel Phantastes “baptized” his imagination, having a crucial impact long before he considered the intellectual question of whether Christianity was true. Many more have been drawn to Christ through Lewis’s own writing. In Mere Christians , Mary Anne Phemister and Andrew Lazo gathered accounts from readers of the impact of Lewis’s writings on their spiritual lives. For example, Atessa Afshar, a convert to Christianity from Islam, remarked that “in Perelandra , he displayed angels as close to their biblical revelation as words can manage. I was captivated: these eldila I could believe in, for they were not ridiculous, dewy-looking cherubs.” Philip Yancey noted that the Ransom Trilogy “made the supernatural so believable that I could not help wondering, What if it’s really true? ” As I noted in my own memoir, Not God’s Type , I can attest to the profound impact that Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings had on me; long before I seriously considered the claims of Christianity, I was strangely compelled by his vision of a world that was beautiful and meaningful.

What makes fantasy particularly significant for evangelization? Tolkien’s own analysis of fantasy, in his essay “ On Fairy-stories ,” is helpful in this regard. One of the functions of fantasy, he suggests, is what he calls Recovery: “regaining of a clear view,” and in particular, as “‘seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them’—as things apart from ourselves.” In phrasing Recovery this way, Tolkien emphasizes the meaning behind reality: we are meant to see things in a certain way. Meant by whom? By our Creator. Tolkien’s choice of synonyms emphasizes that we have lost something which once we had: re-gaining, re-covery, re-newal, re-turn. We once had the health and clarity of vision which we now lack; as Christians we understand that this is the result of the fall, played out in our individual lives.

Using the metaphor of a dirty, smudged window, whose film of grime obscures what we see through it, Tolkien says that we need “to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity—from possessiveness.” When we think that we truly know something, or someone, then we often stop really seeing. Indeed, Tolkien notes that our familiares are the “most difficult really to see with fresh attention, perceiving their likeness and unlikeness: that they are faces, and yet unique faces.” The strangeness and difference of a fantasy world, the contrast that it provides between the imagined Secondary World and our real Primary World, facilitates the process of Recovery. Tolkien’s Treebeard and the other Ents, the shepherds of trees, help us to more clearly see the marvelous reality and particularity of trees: oaks, ash, beech, rowan. The homely comforts of second breakfast in a hobbit-hole in the Shire help us recognize the genuine beauty of a simple meal at home with family.

C.S. Lewis describes much the same concept when discussing the creation of the Narnia Chronicles in his essay “Sometimes Fairy Stories Say Best What’s to Be Said”:

I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralysed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.

Lewis noted that the Narnia books were “all about Christ,” yet they are anything but propagandistic evangelizing tracts. (The ire directed against the Chronicles by a few, such as Philip Pullman, ironically serves to emphasize their literary power: no one bothers to rail against the blandly pious and forgettable volumes in the average Christian Fiction section in the bookstore.) Rather, the Chronicles are infused with Christ, centered on the figure of Aslan, so that the reader breathes in the very spirit of Christ in their reading, as Michael Ward has explained in fascinating depth in Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis . Our sojourn in the fantasy world of Narnia helps us to recover a fresh vision of Christ, a rich and dynamic sense of who he is, and how we can get to know him.

In my earlier piece on Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “As kingfishers catch fire,” I pointed out how the poet guides us to look closely at the world, to truly see rather than just glance at something, and thus helps us, for a moment, to see the world through the eyes of faith. The reader may, for a brief moment, see from the inside what it means to have an identity in Christ, or to see the world as God sees it. Such an experience can have a lasting effect.

Fantasy, Tolkien is careful to note, has a deep and necessary relationship with the world as it truly is: “For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it.” He goes on to explain that “Fantasy is made out of the Primary World. . . . And actually fairy-stories deal largely, or (the better ones) mainly, with simple or fundamental things, untouched by Fantasy, but these simplicities are made all the more luminous by their setting. . . . It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of the words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; bread and wine.”

By closing his list with the subtle Eucharistic image of “bread and wine,” Tolkien hints at the power of Fantasy to cleanse our vision on the deepest possible level. It is only a hint: he is too wise to belabor the point. He who has ears to hear, let him hear!

The desirable end result of fantasy, Tolkien says, is for the story to “open your hoard and let all the locked things fly away like cage-birds. The gems all turn into flowers or flames, and you will be warned that all you had (or knew) was dangerous and potent, not really effectively chained, free and wild.” And that gives us guidance, as evangelists. We should not try to make fantasy stories into rigid allegories or evangelistic tracts; we should not try to force the Christian connections upon people who are not yet ready or interested in discovering them.

To do that is to shut the birds back in their cages and lock up the hoard once again. Rather, we should allow these marvelous stories to be “free and wild”—that is, to allow readers to experience the story as story, and delight in it with them. The happy ending of a fantasy story, Tolkien writes, does not ignore “sorrow and failure” but rather “it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.” Such a story does not impose, but it invites, a further consideration of the source of this mysterious Joy. As evangelists, then, we should stand ready to be, like Virgil in Dante’s Divine Comedy , guides on the journey for those readers who have become intrigued, or perhaps unsettled, by this glimpse of hope. We can help them see even more clearly how our Primary World has depths of meaning and beauty beyond anything dreamed of in the most exciting fantasy novel ever written.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Fantastical Experience: The Relationship between History, Fantasy, and Reality in Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere

This dissertation proposes a fantastical experience analogue to the historical experience proposed by Frank Ankersmit. It investigates how contemporary popular fantasy literature may provoke an experience of the fantastical within its readers, and serve to enrich the reader's experience of reality. After proposing this theory, this dissertation examines Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere as a case study. It concludes that the unique mixture of actual history with fictionalised and fantastical history serves to imaginatively transport its readers to a new realm.

Related Papers

Seda Pekşen

New Horizons in English Studies

Julia Seltnerajch

Neil Gaiman’s urban fantasy novel Neverwhere revolves around some problematic aspects prevalent in the contemporary world, such as an iniquitous discrepancy between social classes or a problematic attitude to history. The artistic universes created by Gaiman are instrumental in conveying a complex condition of postmodern society. Although one of the represented worlds, London Above, is realistic and the other, London Below, is fantastic, both are suggestive of the contemporary social situation, citizens’ shared values and aspirations. Only when considered together can they reveal a comprehensive image of what the community accepts and what it rejects as no longer consistent with commonly held beliefs. The disparities in the representations of London Above and London Below refer to the division into the present and the past. The realistically portrayed metropolis is the embodiment of contemporary times. The fantastic London Below epitomises all that is ignored or rejected by London Above. The present study is going to discuss the main ideas encoded in the semiotic spaces created by Neil Gaiman, on the basis of postmodern theories. I am going to focus on how the characteristic features of postmodern fiction, such as the use of fantasy and the application of the ontological dominant, by highlighting the boundaries between London Above and London Below affect the general purport of the work.

Andres Romero-Jodar

According to certain theories, Postmodernism makes a conscious use of the cyclical nature of mythical narrations in response to the anxieties of fragmentation and isolation of the self. Hence, Postmodernism, through its own mechanisms and techniques, offers reconceptualizations of the mythical strucutre applied to the contemporary social conditions. The aim of this article is to analyse how Neil Gaiman consciously employs a mythical structure in his first novel, "Neverwhere" (1996), and how he subverts the final aim of this pattern. My contention is that "Neverwhere" is a postmodernist novel whose structure follows the cyclical pattern of the Campbellian monomyth. But the cyclical nature of the myth is utterly transformed in the novel.

Darko Suvin

0. Fantasy: Why Bother?; 1. Some Preconditions for Approaching Fantasy; 2. On What Fantastic Fiction Is Not; 3. In medias res: The Genres of Ahistorical Alternative Worlds; 4. Some Dilemmas on Uses and Values of Fantasy.

Tereza Dědinová

The aim of this paper is to show a correlation between the level of integration of the fantastic element into the structure of the fictional world and the potential of literary works to be successfully read as both fantastic literature and non-genre literature, valuable for their meaning, transcendence and art of narration. It will introduce four levels of integration of the fantastic element and focus on two neighbouring levels: the fantastic element used as a platform and as a resource. Using four specific examples, I will try to distinguish very different attitudes toward the fantastic element and to argue that literary works using the fantastic element merely as a resource for expressing something else do not necessarily indicate failed fantasy, but create a specific fuzzy set within fantastic literature, which I call the fantastic as a means of expression (and which might be distinguished from the fuzzy set of the pure fantastic, characterised by the full contextualisation of t...

Lars Schmeink, H.-H. Müller: Fremde Welten. Wege und Räume der Fantasie im 21. Jahrhundert. Berlin: De Gruyter

Frank Weinreich

The paper examines to what extent fantastic literature, movies and other art can actually be termed "fantastic" in the sense of dealing with or telling of impossible events. The argument of the paper is that fantastic art rather deals foremost with real life, only applying a fantastic "disguise" to the real-life stories it tells. The paper claims that the fantastic is a specific mode of storytelling which is used to enhance certain aspects of real life by clothing it in unlikely garb in order to emphasize the underlying meaning, as do metaphors in other circumstances also. Thus, the paper concludes, the fantastic in general is able to reach the same level of applicability and meaning that all other art does. This in turn also means that artists of the fantastic should be aware of a certain kind of responsibility for their works, especially as the fantastic is a very successful genre holding great appeal to a younger audience.

Richard McCulloch

The Place of Memory and Memory of Place

The central focus of the research paper is on the urban fantasy novel by Neil Gaiman entitled Neverwhere. I would like to discuss the manipulation of memories imprinted in the urban space of London Below so as to prove that the cityscape can serve as a container for past times, now erased from contemporary society’s consciousness. The analysis of the fictional world will be supported by the discussion of urban theory. London Below, one of the fictional worlds in Neverwhere, embraces vivid reminiscences of past times. These memories immersed in space are not only sheer representations of bygone times; they become literally alive, they create and model the reality around. The cityscape, the world of things lost and forgotten, embodies aspects that seem no longer worth remembering in a contemporary society. Particular components of the city figuratively plunged into darkness, such as ruins, forgotten buildings or family homes relate to different sorts of memories, not only those regarding the past, but also personal recollections. This paper is going to focus on how the issue of memories and foregone times is treated by the author and to what extent Gaiman’s depiction can be suggestive of the condition of contemporary society. Keywords: Gaiman, Neverwhere, memory, London Below, the past, fantasy

Daniel Baker

Ars Aeterna

Simona Klimková

The paper focuses on the phenomenon of urban fantasy with a particular interest in the topos of a city, which assumes great significance as a thematic and motivic element in the subgenre. The authors touch upon the relation between (sub)genre and topos/topoi in general, but also more specifically, between urban fantasy and the city, regarding the urban area as a distinct setting with a specific atmosphere, character or genius loci. Within this frame, the paper seeks to exemplify the aforementioned relations through an interpretative study of Neil Gaiman’s novel Neverwhere, which breathes life into the London underground scene. London Below comes to personify, literally, the vices of London Above via the use of anthropomorphic strategies. Moreover, the spatial peculiarities of the novel not only contribute to the creation of the fantastical atmosphere but they also function as a vehicle of social critique and a constitutive element of the protagonist’s transformation.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Phainomenon

Pedro M S Alves

Journal of Narrative and Language Studies

Mehmet Galip Zorba

Journal of Language and Politics

Jason Glynos

Nike Pamela

Grace Monroe

Munazza Yaqoob

rebecca suter

Andrew Rayment

Orbis Litterarum

Hanna Meretoja

Katarzyna Wasylak

IJAR Indexing

Leonie Viljoen

Via Panoramica: Revista de Estudos Anglo-Americanos

Baysar Taniyan

Neophilologus

Dr Maureen A . Ramsden

University of York

Basil A Price

Reading Teacher

Catherine Kurkjian

ACTA IASSYENSIA COMPARATIONIS

Andrei Cojocaru

Historical Materialism

Karan Kumar

Michael Sarabia

Anne-Li Lindgren

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Fantasy Literature

Fantasy literature is a genre of imaginative fiction that often features elements such as magic, mythical creatures, and extraordinary settings. It has been around for centuries in various forms, from classic myths to modern-day books and films. Fantasy literature has become increasingly popular over the years with readers of all ages due to its ability to take us away from our everyday lives into other worlds full of adventure and excitement.

The most common type of fantasy story involves characters on quests or journeys through magical lands filled with strange creatures and obstacles they must overcome in order to reach their goal. These types of tales have been told since ancient times, particularly through oral storytelling traditions like those found in folklore. Many famous authors wrote works featuring these kinds of narratives, including JRR Tolkien's Lord of the Rings series, which helped bring fantasy literature into mainstream culture when it was released in 1954–55.

In addition to quest stories, many fantasies also feature characters who possess special powers, such as wizards or witches who use spells or potions to achieve their goals; gods or goddesses who interfere with human affairs; talking animals; shapeshifters capable of transforming themselves into different shapes at will; dragons (or other powerful monsters); magical weapons used by heroes against villains; alternate realities where anything can happen without consequences; time travel back and forth between different periods within time. history, etcetera. All these elements are combined to create unique tales set apart from any other kind of literary work out there.

One example that stands out among them is Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea Cycle, which tells the story of a young wizard named Ged whose journey leads him across an archipelago made up of islands inhabited by people living alongside fantastical beasts like dragons while learning about his own power along the way. This series consists of six novels written between 1968 and 2001, making it one of the longest-running epic sagas ever written within this particular subgenre.

Other notable examples include C.S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia series, which follows four siblings on their adventures throughout a world populated by mythical beings after discovering an old wardrobe inside Professor Digory Kirke's home; H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, wherein investigators uncover dark secrets related to alien entities living beyond space and time dimensions known only as "Great Old Ones"; and the Terry Pratchett Discworld franchise, which is humorous and takes traditional high fantasy tropes mixed with satirical social commentary is aimed at adults rather than children or young adults.

Aside from being entertaining reads, however, there are deeper reasons why people love reading or watching works belonging to the umbrella term 'fantasy'. Because they offer an escape from reality while simultaneously giving us the opportunity to explore our innermost thoughts and feelings, we may not be comfortable expressing ourselves outside of our imagination (i.e., writing fanfiction). Additionally, some argue that these stories help promote creativity and problem-solving skills through exploration of unfamiliar environments and unexpected plot twists readers come across during the course of the narrative, thus improving overall mental acuity and emotional intelligence too.

No matter what your personal reason may be, one thing remains certain: fantasy literature provides exciting escapism and allows readers to immerse themselves in completely new experiences unlike any experienced before, leaving a lasting impression even after the last page is done.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, written by Lewis Carroll and published in 1865, is a classic work of literature that has captured the imaginations of generations. The story follows Alice as she falls down a rabbit hole into an imaginative world filled with talking animals, whimsical characters, and bizarre situations. Through her journey, Alice learns lessons about life, such as how to think for herself and how to stay true to who she is.

Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief, written by Rick Riordan in 2005, is a modern fantasy novel that has become part of the literary canon. The story follows the young protagonist, Percy, as he discovers his true identity as the son of Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea. After Zeus' lightning bolt is stolen from Mount Olympus, Percy embarks on an adventure to retrieve it with his friends Grover (a satyr) and Annabeth (the daughter of Athena). Along their journey, they encounter monsters from Greek mythology, such as Medusa, Scylla, Charybdis, and the Minotaur. Through this exciting quest filled with danger and excitement, readers are able to learn about various aspects of Ancient Greece while also enjoying an entertaining plot line full of humor and heartwarming moments between characters.

The Wizard of Oz is a classic American children's novel written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W.W. Denslow in 1900. It has become an iconic part of literature with its fantastical story about Dorothy Gale and her adventures in the magical land of Oz, filled with talking animals, witches, and wizards. The characters are beloved around the world for their courage, loyalty, and wit as they face obstacles such as wicked witches and flying monkeys to get back home to Kansas again. In addition to being a timeless tale that continues to be enjoyed today, it also serves as an allegory for several issues facing America at the time, such as industrialization versus rural life or racism towards Native Americans (the Munchkins). Since then, it has been adapted into multiple versions, including stage plays, musicals, films, television series, video games, and even comics. All these adaptations make The Wizard of Oz one of the most widely known stories in literature, which still captivates audiences both young and old alike all over the globe today.

Harry Potter is a globally renowned series of books and films created by J.K Rowling, beginning with the novel "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone" in 1997. The story follows a young wizard-in-training, Harry Potter, as he embarks on his magical journey at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Since its inception, this beloved fantasy franchise has become an international phenomenon, spawning multiple sequels and spin-offs that have captivated readers for more than two decades.

The Lord of the Rings is a classic work of literature that has been beloved by readers for decades. Written by J.R.R. Tolkien, this epic fantasy series follows Frodo Baggins and his quest to destroy the One Ring and save Middle-Earth from Sauron’s dark forces. Along with its sequel, The Hobbit, it helped define modern fantasy fiction as we know it today.

Plot Summary

"The Princess Bride" is a fantasy novel written by William Goldman, which is presented as an abridged version of a fictional book written by S. Morgenstern, with Goldman providing commentary throughout.

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

- Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief

- The Wizard of Oz

- Harry Potter

- The Lord of the Rings

- The Princess Bride

In Mendlesohn’s The Rhetoric of Fantasy, she outlines various methods that can be used to enter the reader into the “fantasy” of fantasy novels. Three of the main methods of entering the secondary world are portal-quest, immersion, and intrusion stories. Many fantasy novels explore at least one if not more of the options outlined by Mendlesohn. We can consider the choices made in children’s fantasy literature in conjunction with their levels of involvement, entertainment, and capacity to pass off

Composers of Fantasy texts successfully use Fantasy conventions to engage their audience by magical worlds. Fantasy text composers make their own magical world since it will engage their audience. Most worlds, you'll notice, are full of magic meaning wizards are very common. The audience is attracted to the text as the Fantasy composers use magical worlds, they create rules,maps,languages and cultures. Composers of Fantasy texts do it fantastically so that the audience will understand fictional worlds

In the following section of the paper, I will use the fantasy theme analysis, including its assumptions, and symbolic convergence theory in order to understand my artifact. The fantasy theme criticism was designed by Ernest G. Bormann "to look at how a group dramatizes an event or how a dramatization creates a special kind of myth that influences a group's thinking and behavior"(Rhetorical Criticism, fantasy theme criticism, p 167). The fantasy theme criticism relies on two assumptions: one is that

Fantasy is a make-believe, fictional world or place made for entertainment, typically by people who find reality boring or dull. People invented fantasy to make new surreal worlds, which opened people’s minds to new possibilities. Fantasy can be used to escape the real world, Coraline, a fantasy novel by Neil Gaiman, is a good example of this. It pulls us into a new world full of strange beings and new, unknown places. Fantasy is the real world from an unfamiliar perspective, taking difficult tasks

Fantasy Genre: A Lens Into Ourselves “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies. The man who never reads lives only one” (Martin 2000). This was a quote written by one of the most well known authors of our time, George R. R. Martin, and how true it is. Readers of the fantasy genre live lives full of magic, kings, castles, and heroes. The fantasy genre is one with deep roots in history, and it is still popular today. It has evolved through the years with changing opinions and beliefs, but fantasy

relationship between fantasy in reality, and desire connects between the various states of the mind. Fantasy is when someone’s thoughts are indifferent to what is actually happening in reality. A person may imagine impossible things, that have been imaged about a situation. Understanding oneself and why the mind works in a specific way can help accept what is in the present, and letting go of what is holding one back. Certain actions can help break getting lost within fantasy which causes growth for

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Fantasy

Introduction, general overviews.

- Reference Works

- Anthologies

- Definitions

- Audio-Visual Style

- Fantasy Worlds and World Building

- Ideology and Politics

- Major Directors of Fantasy Films

- Fairy Tale Films

- The Lord of the Rings Films

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Elmer Bernstein

- Georges Méliès

- Hayao Miyazaki

- Hollywood and Politics

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Queer Television

- Science Fiction Film Theory and Criticism

- Terry Gilliam

- The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

- The Twilight Zone

- The Wizard of Oz

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Superhero Films

- Wim Wenders

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Fantasy by David Butler LAST REVIEWED: 29 November 2022 LAST MODIFIED: 29 November 2022 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0192

Fantasy films can be traced to the early years of film history and Georges Méliès, cinema’s first great fantasist, in particular. Méliès is often presented (somewhat simplistically) as embodying one of the two fountainheads of cinema, alongside the documentary realism of the Lumière brothers, placing fantasy as a vital founding impulse in film. Fantasy films represent hopes and desires for better or alternative worlds, and through the technical developments required to portray those worlds, they have contributed significantly to the development of cinema and how we experience it. For many, fantasy films are typified by formulaic products—fairy tales for children and heroic quest narratives in magical pseudo-medieval realms for adolescents—but the range of fantasy films is remarkable, taking in popular mainstream “classics” (e.g., The Wizard of Oz [1939]), big-budget franchises (e.g., Harry Potter), small-scale independent projects (e.g., Tideland [2005]), and films by prominent figures in so-called art-house cinema (e.g., Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander [1982]). That diversity and perceived emphasis on the populist and juvenile has contributed to the academic literature on fantasy film being slow to develop. Although the Freudian notion of fantasy as a psychic process to help negotiate and repress traumatic memories meant that the psychoanalytical term “fantasy” was often evident, especially in the “grand theory” flourishing across film studies in the 1970s–1990s, there was relatively little discussion of fantasy films in the sense of narrative fictions featuring worlds or events that in some way break empirically (or magically) and ontologically with the known laws of our universe. From the 1980s, science fiction and horror cinema began to accumulate a substantial literature, but the more amorphous notion of fantasy would lag far behind: scattered articles rather than sustained dialogue, despite the early and mid-1980s seeing sustained fantasy filmmaking, especially from Hollywood. Defining fantasy has been problematic (e.g., is it a coherent genre? Is it a broader impulse to move away from mimetic representations of what is understood to be empirical and ontological reality? In what way can (or should) it be distinguished from science fiction and horror?), but it has also suffered from suspicious intellectual schools of thought (Marxism not least). Perhaps inevitably, given the influx of films released in the wake of the phenomenal success of The Lord of the Rings (2001–2003) and Harry Potter films revealing a “global hunger” for fantasy, as Susan Napier refers to it in Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation ( Napier 2005 , cited under Individual Genres ), the 2000s witnessed a welcome change with the publication of several introductory texts on studying fantasy film, collections on aspects of fantasy film, monographs on individual films, and articles from a wealth of theoretical perspectives.

Early overviews of fantasy film tended to be brief, typically a few pages in wider discussions about the history and development of film rather than focused studies. Writing in 1960, Kracauer’s chapter addressing (in part) fantasy film ( Kracauer 1997 , cited under Audio-Visual Style ) was extensive for its time and demonstrated awareness of a wide range of exponents and techniques of cinematic fantasy, from Méliès, Chaplin, and René Clair to Disney and Powell and Pressburger, with particular emphasis on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and Vampyr (1932). Fantasy film would not receive an extended book-length overview until Von Gunden 1989 , which provides critical commentary and production details on fifteen “great fantasy films,” each representing a separate subgenre of fantasy. Von Gunden’s case studies range from King Kong (1933) to Conan the Barbarian (1982) and with the exception of La Belle et la bête (1946), Time Bandits (1981), and The Dark Crystal (1982) are all Hollywood productions. A much more extensive account of fantasy cinema is provided in Worley 2005 , which provides critical commentary on a far wider range of films, going back to the earliest years of cinema and taking in examples from around the world as well as not being restricted to perceived classics or great films. In the late 2000s, Butler 2009 , Fowkes 2010 , Walters 2011 , and Furby and Hines 2012 appeared in quick succession, offering contrasting introductions to the subject and reflecting the growing recognition and prominence of fantasy in (popular) culture as well as the softening of academia toward the validity of fantasy (film) as something meriting serious analysis. Each book provides an overview of fantasy film in terms of how to approach its study and the key issues and debates surrounding it as well as its history. All four acknowledge the difficulty in defining fantasy and address dismissive attitudes toward fantasy, but each has its own particular strengths. Butler emphasizes archival research and audio-visual style, Fowkes offers the most extensive case studies of individual films, Walters’s chapters are grouped more around conceptual discussions, and Furby and Hines offer discussion of the widest range of theoretical approaches.

Butler, David. Fantasy Cinema: Impossible Worlds on Screen . London: Wallflower, 2009.

Covers defining fantasy (noting industry and scholarly definitions), “fantasy violence,” major genres (e.g., fairy tale), special effects and audio-visual style, and the social value and function of fantasy. The range of films discussed is the widest of the recent introductions in terms of examples outside Hollywood, including Czech, French, and Japanese cinema.

Fowkes, Katherine A. The Fantasy Film . Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

DOI: 10.1002/9781444320589

Engaging but weighted heavily toward contemporary Hollywood productions. Addresses defining the fantasy genre (including Fowkes’s own definition), a brief historical overview of fantasy film, major critical and theoretical approaches to studying fantasy film before the book’s core content: a series of readings of individual films (e.g., The Wizard of Oz ) and franchises (e.g., Shrek, Harry Potter).

Furby, Jacqueline, and Claire Hines. Fantasy . Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2012.

Thorough overview of the history of fantasy film and major approaches to its study. As with Fowkes, the emphasis is on Hollywood, but the volume includes a more substantial account of the debates around definition and key theoretical discussions, including psychoanalysis, adaptation, realism, narrative, gender, violence, special effects, and the monstrous. Case studies include The Dark Knight (2008).

Von Gunden, Kenneth. Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films . Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1989.

Covering fifteen “superior” films representing separate subgenres of fantasy (e.g., sword and sorcery) with clear synopses and overviews of each film’s production before discussing their respective merits. These genres are not always defined with critical rigor, however, or semantic and syntactic depth (e.g., the somewhat hazy “other worlds, other times”).

Walters, James. Fantasy Film: A Critical Introduction . Oxford and New York: Berg, 2011.

DOI: 10.5040/9781501351051

Addresses the problem of defining fantasy with insightful chapters on the relationship between fantasy and concepts such as authorship and genre (discussing the films of Vincente Minnelli), childhood and entertainment, the interior imagination, and space and audio-visual style/coherency with Watership Down (1978) and The Lord of the Rings as closing case studies.

Worley, Alec. Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Méliès to The Lord of the Rings. Foreword by Brian Sibley. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005.

Extensive critical commentary on the history of fantasy cinema, taking in major films and lesser-known examples. Chapters address defining fantasy film (emphasizing the presence of magic), the birth of fantasy cinema then more substantial chapters on major forms of fantasy: fairy tales, earthbound fantasy, heroic fantasy, and epic fantasy.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- À bout de souffle

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Australian Cinema

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Documentary Film

- Downton Abbey

- Dr. Strangelove

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film and Literature

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Game of Thrones

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Golden Girls, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Icelandic Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- It Happened One Night

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latin American Cinema

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Cinema

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Russian Cinema

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Shakespeare on Film

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Tati, Jacques

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and Film

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yang, Edward

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

- Corpus ID: 162051107

A Short History of Fantasy

- F. Mendlesohn , E. James

- Published 2009

50 Citations

The worlds of popular fiction: genres, texts, reading communities.

- Highly Influenced

- 18 Excerpts

Genii Loci and Ecocriticism from Mythology to Fantasy

The edge of the imaginary world: the influences of imperialism and expansionism in secondary world cartography, la expansión del transmedia en el género fantástico: de matrix a gravity falls, el ministerio del tiempo y stranger things., o mundo de oz de l. frank baum: conto de fadas modernizado, utopia norte-americana ou alta fantasia avant la lettre, fantasy’s traumatic take on the bildungsroman:reading neil gaiman, xiuzhen (immortality cultivation) fantasy: science, religion, and the novels of magic/superstition in contemporary china, disability, literature, genre, motiv straha i njegovi mehanizmi u hrvatskoj fantastičnoj noveli 19. stoljeća, the cambridge introduction to british fiction, 1900–1950, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Hallmarks of Fantasy: A Brief History of the Genre

Then the dragon made a dart at the hunter, but he swung his sword round and cut off three of the beast's heads. Art and Picture Collection, NYPL (1900 - 1909). NYPL Digital Collections, Image ID: 1698228

The history of fantasy is as old as humanity itself. Every culture around the world has their own myths and folklore that they use to impart lessons or carry on pieces of their history. Some of the oldest works of classical fiction are fantastical stories passed on through the centuries and across international borders such as One Thousand and One Arabian Nights , and Journey to the West . Greco-Roman , Egyptian , and Norse mythology are among the most popular and most recognizable collections of stories read on an international level.