Cross-Cultural Psychology

WEIRD, Culture

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Cross-cultural psychology is a branch of psychology that explores the similarities and differences in thinking and behavior between individuals from different cultures.

Scientists using a cross-cultural approach focus on and compare participants from diverse cultural groups to examine ways in which cognitive styles, perception, emotional expression, personality , and other psychological features relate to cultural contexts. They also compare cultural groups on broad dimensions such as individualism and collectivism—roughly, how much a culture emphasizes its members’ individuality versus their roles in a larger group.

Psychologists who are interested in expanding psychology’s focus on diverse cultures have pointed out that the majority of research participants are, to use a popular term, WEIRD: they are from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies. Cross-cultural research has made it clear that what psychologists conclude about this slice of the world’s population does not always extend to people with other cultural backgrounds.

- What Is Cross-Cultural Psychology?

- Psychological Differences Across Cultures

- The WEIRDness of Psychology

Psychology’s mission to understand how humans think and behave requires studying humanity as broadly as possible—not just the humans to which researchers tend to be nearest. Psychologists who conduct cross-cultural research investigate the richness of human psychological variation across the world, including points of consistency and divergence between populations with distinct cultural backgrounds, such as those in Western and East Asian countries.

Psychological research that incorporates a more global sample of people provides insights into whether findings and models (such as those about the structure of personality or the nature of mental illness) are universal or not, the extent to which psychological phenomena and characteristics vary across cultures, and the potential reasons for these differences. Cross-cultural research demonstrates that experimental effects, correlations, or other results that are observed in one cultural context—for example, the tendency of Western participants to rate their abilities as better-than-average—do not always appear in the same way, or at all, in others.

While various definitions are used, culture can be understood as the collection of ideas and typical ways of doing things that are shared by members of a society and have been passed down through generations. These can include norms, rules, and values as well as physical creations such as tools.

Cross-cultural studies allow psychologists to make comparisons and inferences about people from different countries or from broader geographic regions (such as North America or the Western world). But psychologists also compare groups at smaller scales, such as people from culturally distinct subpopulations or areas of the same country, or immigrants and non-immigrants.

While there is overlap between these approaches, there are also differences. Cross-cultural psychology analyzes characteristics and behavior across different cultural groups, with an interest in variation as well as human universals. Cultural psychology involves comparison as well, but has been described as more focused on psychological processes within a particular culture. In another approach, indigenous psychology, research methods, concepts, and theories are developed within the context of the culture being studied.

The inhabitants of different regions and countries have a great deal in common : They build close social relationships, follow rules established by their communities, and engage in important rituals. But globally, groups also exhibit somewhat different psychological tendencies in domains ranging from the strictness of local rules to how happiness and other emotions are conceived. Of course, within each region, nation, or community, there is plenty of individual variation; people who share a culture never think and act in exactly the same way. Cross-cultural psychology seeks to uncover how populations with shared cultures differ on average from those with other cultural backgrounds—and how those differences tie back to cultural influence.

While there are shared aspects of emotional experience across cultural groups, culture seems to influence how people describe, evaluate, and act on emotions. For example, while the experience of shame follows perceived wrongdoing across cultures, having shame may be evaluated more positively in some cultures than in others and may be more likely to prompt behavioral responses such as reaching out to others rather than withdrawing. Different emotional concepts (such as “ anxiety ,” “ fear ,” and “ grief ”) may also be thought of as more or less closely related to each other in different cultures. And cultural differences have been observed with regard to how emotions are interpreted and the “display rules” that individuals learn about appropriate emotional expression.

While happiness seems to be one of the most cross-culturally recognizable emotions in terms of individual expression, culture can influence how one thinks about happiness. Research indicates that people in different cultures vary in how much value they place on happiness and how much they focus on their own well-being. Culture may also affect how people believe happiness should be defined and achieved —whether a good life is to be found more in individual self-enhancement or through one’s role as part of a collective, for example.

Some mental health conditions, in addition to being reported at markedly different rates in different countries, can also be defined and even experienced in different ways. The appearance of depression may depend partly on culture —with mood-related symptoms emphasized in how Americans think of depression , for example, and bodily symptoms potentially more prominent in China. Features of certain cultural groups, such as highly stable social networks, may also serve as protective factors against the risk of mental illness. Increased understanding of cultural idiosyncrasies could lead to gains in mental health treatment.

Individualism and collectivism are two of the contrasting cultural patterns described in cross-cultural psychology. People in relatively collectivist cultures are described as tending to define themselves as parts of a group and to heed the norms and goals of the group. Those in relatively individualistic cultures are thought to emphasize independence and to favor personal attitudes and preferences to a greater degree. Cross-cultural psychologists have pointed to East Asia, Latin America, and Africa as regions where collectivism is relatively prominent and much of Europe, the U.S., and Canada as among those where individualism is more pronounced. But individualism-collectivism is thought of as a continuum, with particular countries, and cultures within those countries, showing a balance of each.

Tightness and looseness are contrasting cultural patterns related to how closely people adhere to social rules. Each culture has its own rules and norms about everything from acceptable public behavior to what kinds of intimate relationships are allowed. But in some cultures, or even in particular domains within cultures (such as the workplace), the importance placed on rules and norms and the pressure on people to follow them are greater than in other cultural contexts. Relatively rule-bound cultures have been described as “tight” cultures, while more permissive cultures are called “loose.” As with individualism and collectivism, tightness and looseness are thought of as opposite ends of the same dimension.

It seems to be. In the West, the Big Five model of personality traits and related models were developed to broadly map out personality differences, and they have been tested successfully in multiple countries. But research suggests that in some cultures, the Big Five traits are not necessarily the best way to describe how people perceive individual differences. Scientists have also found that associations between personality traits and outcomes that appear in some cultures may not be universal. For example, while more extraverted North Americans appear to be happier, on average, extraverts may not have the same advantage elsewhere.

While some mating preferences, such as a desire for kindness and physical attractiveness in a partner, appear in many if not all cultures, preferences also differ in some ways across cultures—like the importance placed on humor or other traits. In the realm of physical attraction , both men’s preferences and women’s preferences seem to depend partly on the cultural context, with research suggesting that men in wealthier societies more strongly favor women of average-to-slender weight, for instance.

In cross-cultural psychology, an analytic cognitive style roughly describes a tendency to focus on a salient object, person, or piece of information (as in an image or a story) independently from the context in which it appears. A holistic cognitive style, in contrast, involves a tendency to focus more on the broader context and relationship between objects. Using a variety of tasks—such as one in which a scene with both focal objects and background elements is freely described—psychologists have reported evidence that participants from Western cultures (like the U.S.) tend to show a more analytic cognitive style, while those from East Asian cultures (like Japan) show a more holistic cognitive style. Analytic thinking and holistic thinking have been theorized to stem, respectively, from independent and interdependent cultural tendencies.

The psychological findings that get the most attention are disproportionately derived from a fraction of the world’s population. Some scientists call this relatively well-examined subgroup of human societies WEIRD: that is, Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. As long as people who live in countries that meet these descriptors are the primary subjects of psychological research—and that has long been the case—it will often be difficult for psychologists to determine whether an observation applies to people in general or only to those in certain cultural contexts. Increasing the representation of people from diverse cultures in research is therefore a goal of many psychologists.

WEIRD populations are those who are broadly part of the Western world and who live in democratic societies that feature high levels of education , wealth, and industrialization. While there is not a single agreed-upon list of WEIRD cultures—and populations within particular countries can show different levels of these characteristics—commonly cited examples of WEIRD countries include the U.S., Canada, the U.K. and other parts of Western Europe, and Australia.

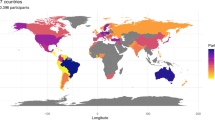

Sampling top psychology journals in the mid-2000s, psychologist Jeffrey Arnett observed that 96 percent of research subjects came from Western, industrialized countries that represented just 12 percent of the world’s population, and that about two-thirds were from the U.S. Subjects seemed to largely be sourced from the countries in which the researchers lived. In 2010, citing this finding and others, Joseph Henrich, Steven Heine, and Ara Norenzayan introduced the term WEIRD to describe this subpopulation. They expanded on the problems with focusing so exclusively on such participants and with assuming that findings from a relatively unrepresentative group generalized to the rest of the world.

In numerical terms, it seems, not much. While the problems with global underrepresentation in psychology research have gained more attention in recent years, an updated analysis of top journals in the mid-2010s found that the vast majority of samples were still from Western, industrialized countries, with about 60 percent from the U.S.

In many ways, WEIRD populations seem to be less representative of humans in general than non-WEIRD populations are. Overlapping with other findings from cross-cultural psychology, psychological differences between people from relatively WEIRD countries and those from elsewhere have been noted: WEIRD samples show higher levels of individualism and lower levels of conformity , on average, among other characteristics. One scientist behind the WEIRD concept theorizes that societal changes in the West caused by the Catholic Church, and their subsequent cultural impact, help explain these signature differences.

In traditional Eastern cultures, coming out is not the cause for celebration that it can be in some Western countries.

Observations of play in Tokyo revealed that Japanese children tended to engage in more rule-based, academic play than is typical among American children.

An intentional response to the climate crisis.

Cultural factors deeply shape BFRB experiences and treatment, from the symbolic meanings of hair, skin, and nails to the impact of intersectional stigma on marginalized individuals.

Personal Perspective: Why are cultural changes so difficult? Drawing from my Korean American experience, I suggest that a surprising psychological process can aid acceptance.

Navigating neurodivergence in the BIPOC community involves recognizing how race, culture, and systemic biases shape mental health and addressing these overlapping challenges.

A new practical method for promoting fair-mindedness, reducing bias and engaging in meaningful conversations that promote understanding and progress.

Ever feel like you’re struggling to connect with a therapist? Discover what experts have to say about culturally congruent care.

Ever wonder why there are few minority psychologists? This may be one of the reasons.

Discover whether being on time really matters and how it can reflect a culture's values.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Comprehensive Coverage Ten Times a Year!

The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology provides the latest empirical research on important cross-cultural questions in social, developmental, cognitive, linguistic, personality, organizational and other areas of psychology.

Regular Features

Each volume of the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology includes empirical papers, brief reports, and integrative review articles of empirical cross-cultural research, along with theoretical papers that may suggest new orientations for future research. The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology publishes cross-cultural and single culture studies, and quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods are represented.*

Thematic Discussions

The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology supplements its broad coverage with single-themed Special Issues and Special Sections dedicated to topics of particular interest. Previous thematic discussions include Culture, Creativity, and Innovation and Reflections on Methods and Theory . Special Issue Coming Soon – Norms and Assessment of Communication Contexts: Multidisciplinary Perspectives .

Access and Article Submission

To read about the history and continuing development of JCCP click here

To see the masthead policy of JCCP, types of articles published, and instructions for submitting articles, please see the JCCP section of the Sage web site. Click here .

The tables of contents of current and past issues can be accessed on the Sage web site. Click here .

IACCP members have free access to current and past issues of JCCP. If you are member in good standing, log onto the membership portal with your username and password, then click on the link "Access JCCP Online".

Sylvia X. Chen Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Founding and Contributing Editor

Walter J. Lonner Western Washington University, USA (Emeritus)

Special Issues Editor

Deborah L. Best Wake Forest University, USA (Emerita)

Associate Editors

Brien Ashdown Carlos Albizu University, USA

Judith Gibbons Saint Louis University, USA

Yanjun Guan Nottingham University Business School, China

Keiko Ishii Nagoya University,Japan

Takeshi Hamamura Curtin University, Australia

Vaisali Raval Miami University,USA

Sunita Stewart University of Texas Southwestern,USA

Junko Tanaka-Matsumi Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan

Antonio Terracciano Florida State University, USA

Ching (Catherine) Wan Nanyang Technological University,Singapore

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

For 50 years the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology has provided a leading interdisciplinary forum for psychologists, sociologists, and other researchers who study the relations between culture and behavior.

Comprehensive Coverage - Eight Times a Year!

The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology provides the latest empirical research on important cross-cultural questions in social, developmental, cognitive, linguistic, personality, organizational and other areas of psychology.

Regular Features

Each volume of the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology includes empirical papers, brief reports, and integrative review articles of empirical cross-cultural research, along with theoretical papers that may suggest new orientations for future research. The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology publishes cross-cultural and single culture studies, and quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods are represented.

Thematic Discussions

The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology supplements its broad coverage with single-themed Special Issues and Special Sections dedicated to topics of particular interest. Previous thematic discussions include Bridging Cross-Cultural Psychology with Societal Development Studies, Half-Century Assessment, Europe's Culture(s): Negotiating Cultural Meanings, Values, and Identities in the European Context, and Reflections on Methods and Theory. Special Issues Coming Soon: Diverse Methods for Assessing Cultural Identity, and Mapping Human Morality: Human Universals and Cultural Differences.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology publishes papers that focus on the interrelations between culture and psychological processes. Submitted manuscripts may report results from either cross-cultural comparative research or single culture studies.

Research that concerns the ways in which culture, and related concepts such as ethnicity, affects the thinking and behavior of individuals, as well as how individual thought and behavior define and reflect aspects of culture are appropriate for the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology .

Cultural Variables. Cultural variables that may be related to the behavior(s) of interest should be assessed rather than relying upon conjectures regarding assumed cultural differences that could be influencing behavior(s).

Empirical Research. Most papers published in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology are reports of empirical research. Empirical studies must be described in sufficient detail to be potentially replicable.

- NOTE: The Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology does not publish psychometric studies of test construction or validation. Studies that compare scale performance or factor structure among different cultural groups are also not considered by the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology .

Reviews and Theoretical Papers. Integrative reviews that synthesize empirical studies and innovative reformulations of cross-cultural theory will also be considered. These reviews are expected to reformulate or offer a novel perspective to an existing cross-cultural theory or research area.

Single Nation/Culture Research. Studies reporting data from within a single nation should focus on cultural factors and explore the theoretical or applied relevance of the findings from a broad cross-cultural perspective.

Methods. Psychology publishes studies using quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods.

Authors who are uncertain about the appropriateness of particular manuscripts should contact the Editor, Senior Editor, or any of the Associate Editors for clarification and advice.

| Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China |

| Western Washington University, USA (Emeritus) |

| Wake Forest University, USA (Emerita) |

| Carlos Albizu University, USA | |

| University of Essex, UK | |

| Nottingham University Business School, China | |

| Curtin University, Australia | |

| Nagoya University, Japan | |

| Miami University, USA | |

| University of Texas Southwestern, USA | |

| Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan | |

| Florida State University, USA | |

| Nanyang Technological University, Singapore |

| Grand Valley State University, USA | |

| University of Tartu, Estonia | |

| Scripps College, USA | |

| Pompeu Fabra University, Spain | |

| Jacobs University Bremen, Germany | |

| Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China | |

| Tilburg University, Netherlands | |

| North-West University, South Africa | |

| Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany | |

| Georgetown University, USA | |

| the University of Saskatchewan, Canada | |

| Chinese University of Hong Kong, China | |

| Washington State University, USA | |

| Grand Valley State University, USA | |

| University of Queensland, Australia (Emerita) | |

| University of Wisconsin – La Crosse, USA (Emeritus) | |

| University of Trier, Germany | |

| San Francisco State University and Humintell, LLC, USA | |

| National Chung Cheng University, Taiwan | |

| La Trobe University, Australia | |

| University of Melbourne, Australia | |

| San Francisco State University, USA | |

| Baltimore, MD, USA | |

| New York University, USA | |

| University of Athens, Greece | |

| Tilburg University, Netherlands (Emeritus) | |

| University of Warwick, UK | |

| City University of Hong Kong, China | |

| Concordia University, Canada | |

| University of Guelph, Canada | |

| Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel | |

| Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel | |

| University of Sussex, UK (Emeritus) | |

| University of Konstanz, Germany (Emerita) | |

| University of Groningen, Netherlands (Emeritus) | |

| Elon College, USA | |

| Peking University, China | |

| Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand | |

| Sabanci University, Turkey | |

| University of Leuphana, Germany | |

| The University of Tokyo, Japan |

| Wake Forest University, USA |

- Abstract Journal of the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC)

- Abstracts in Anthropology Online

- Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- Clarivate Analytics: Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences

- Corporate ResourceNET - Ebsco

- Current Bibliography of African Affairs

- Current Citations Express

- EBSCO: Business Source - Main Edition

- EBSCO: Human Resources Abstracts

- ERIC Current Index to Journals in Education (CIJE)

- Family & Society Studies Worldwide (NISC)

- Gale: Diversity Studies Collection

- Health Source Plus

- ISI Basic Social Sciences Index

- International Bibliography of Periodical Literature on the Humanities and Social Sciences (IBZ)

- MasterFILE - Ebsco

- OmniFile: Full Text Mega Edition (H.W. Wilson)

- Peace Research Abstracts Journal

- ProQuest: Applied Social Science Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- ProQuest: CSA Sociological Abstracts

- Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal

- Psychological Abstracts

- Race Relations Abstracts

- Sexual Diversity Studies (formerly Gay & Lesbian Abstracts)

- Social SciSearch

- Social Science Source

- Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Social Sciences Index Full Text

- Social Services Abstracts

- Standard Periodical Directory (SPD)

- TOPICsearch - Ebsco

- Wilson Social Sciences Index Retrospective

Manuscript submission guidelines can be accessed on Sage Journals .

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, E-access Plus Backfile (All Online Content)

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, Combined Plus Backfile (Current Volume Print & All Online Content)

Institutional Backfile Purchase, E-access (Content through 1998)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

To order single issues of this journal, please contact SAGE Customer Services at 1-800-818-7243 / 1-805-583-9774 with details of the volume and issue you would like to purchase.

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Cross-cultural research allows you to identify important similarities and differences across cultures. This research approach involves comparing two or more cultural groups on psychological variables of interest to understand the links between culture and psychology better.

As Matsumoto and van de Vijver (2021) explain, cross-cultural comparisons test the boundaries of knowledge in psychology. Findings from these studies promote international cooperation and contribute to theories accommodating both cultural and individual variation.

However, there are also risks involved. Flawed methodology can produce incorrect cultural knowledge. Thus, cross-cultural scientists must address methodological issues beyond those faced in single-culture studies.

Methodology

Cross-cultural comparative research utilizes quasi-experimental designs comparing groups on target variables.

Cross-cultural research takes an etic outsider view, testing theories and standardized measurements often derived elsewhere.

- Studies can be exploratory , aimed at increasing understanding of cultural similarities and differences by staying close to the data.

- In contrast, hypothesis-testing studies derive from pre-established frameworks predicting specific cultural differences. They substantially inform theory but may overlook unexpected findings outside researcher expectations (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

Each approach has tradeoffs. Exploratory studies broadly uncover differences but have limited explanatory power. While good for revealing novel patterns, exploratory studies cannot address the reasons behind cross-cultural variations.

Hypothesis testing studies substantially inform theory but may overlook unexpected findings. Optimally, cross-cultural research should combine elements of both approaches.

Ideal cross-cultural research combines elements of exploratory work to uncover new phenomena and targeted hypothesis testing to isolate cultural drivers of observed differences (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

Cross-cultural scientists should strategically intersect exploratory and theory-driven analysis while considering issues of equivalence and ecological validity.

Other distinctions include: comparing psychological structures versus absolute score levels; analysis at the individual versus cultural levels; and combining individual-level data with country indicators in multilevel modeling (Lun & Bond, 2016; Santos et al., 2017)

Methodological Considerations

Cross-cultural research brings unique methodological considerations beyond single-culture studies. Matsumoto and van de Vijver (2021) explain two key interconnected concepts – bias and equivalence.

Bias refers to systematic differences in meaning or methodology across cultures that threaten the validity of cross-cultural comparisons.

Bias signals a lack of equivalence, meaning score differences do not accurately reflect true psychological construct differences across groups.

There are three main types of bias:

- Construct bias stems from differences in the conceptual meaning of psychological concepts across cultures. This can occur due to incomplete overlap in behaviors related to the construct or differential appropriateness of certain behaviors in different cultures.

- Method bias arises from cross-cultural differences in data collection methods. This encompasses sample bias (differences in sample characteristics), administration bias (differences in procedures), and instrument bias (differences in meaning of specific test items across cultures).

- Item bias refers to specific test items functioning differently across cultural groups, even for people with the same standing on the underlying construct. This can result from issues like poor translation, item ambiguity, or differential familiarity or relevance of content.

Techniques to identify and minimize bias focus on achieving equivalence across cultures. This involves similar conceptualization, data collection methods, measurement properties, scale units and origins, and more.

Careful study design, measurement validation, data analysis, and interpretation help strengthen equivalence and reduce bias.

Equivalence

Equivalence refers to cross-cultural similarity that enables valid comparisons. There are multiple interrelated types of equivalence that researchers aim to establish:

- Conceptual/Construct Equivalence : Researchers evaluate whether the same theoretical construct is being measured across all cultural groups. This can involve literature reviews, focus groups, and pilot studies to assess construct relevance in each culture. Claims of inequivalence argue concepts can’t exist or be understood outside cultural contexts, precluding comparison.

- Functional Equivalence : Researchers test for identical patterns of correlations between the target instrument and other conceptually related and unrelated constructs across cultures. This helps evaluate whether the measure relates to other variables similarly in all groups.

- Structural Equivalence : Statistical techniques like exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis are used to check that underlying dimensions of multi-item instruments have the same structure across cultures.

- Measurement Unit Equivalence : Researchers determine if instruments have identical scale properties and meaning of quantitative score differences within and across cultural groups. This can be checked via methods like differential item functioning analysis.

Multifaceted assessment of equivalence is key for valid interpretation of score differences reflecting actual psychological variability across cultures.

Establishing equivalence requires careful translation and measurement validation using techniques like differential item functioning analysis, assessing response biases, and examining practical significance. Adaptation of instruments or procedures may be warranted to improve relevance for certain groups.

Building equivalence into the research process reduces non-equivalence biases. This avoids incorrect attribution of score differences to cultural divergence, when differences may alternatively reflect methodological inconsistencies.

Procedures to Deal With Bias

Researchers can take steps before data collection (a priori procedures) and after (a posteriori procedures) to deal with bias and equivalence threats. Using both types of procedures is optimal (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

Designing cross-cultural studies (a priori procedure)

Simply documenting cultural differences has limited scientific value today, as differences are relatively easy to obtain between distant groups. The critical challenge facing contemporary cross-cultural researchers is isolating the cultural sources of observed differences (Matsumoto & Yoo, 2006).

This involves first defining what constitutes a cultural (vs. noncultural) explanatory variable. Studies should incorporate empirical measures of hypothesized cultural drivers of differences, not just vaguely attribute variations to overall “culture.”

Both top-down and bottom-up models of mutual influence between culture and psychology are plausible. Research designs should align with the theorized causal directionality.

Individual-level cultural factors must also be distinguished conceptually and statistically from noncultural individual differences like personality traits. Not all self-report measures automatically concern “culture.” Extensive cultural rationale is required.

Multi-level modeling can integrate data across individual, cultural, and ecological levels. However, no single study can examine all facets of culture and psychology simultaneously.

Pursuing a narrow, clearly conceptualized scope often yields greater returns than superficial breadth (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021). By tackling small pieces thoroughly, researchers collectively construct an interlocking picture of how culture shapes human psychology.

Sampling (a priori procedure)

Unlike typical American psychology research drawing from student participant pools, cross-cultural work often cannot access similar convenience samples .

Groups compared across cultures frequently diverge substantially in background characteristics beyond the cultural differences of research interest (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

Demographic variables like educational level easily become confounds making it difficult to interpret whether cultural or sampling factors drive observed differences in psychological outcomes. Boehnke et al. (2011) note samples of greater cultural distance often have more confounding influences .

Guidelines exist to promote adequate within-culture representativeness and cross-cultural matching on key demographics that cannot be dismissed as irrelevant to the research hypotheses. This allows empirically isolating effects of cultural variables over and above sample characteristics threatening equivalence.

Where perfect demographic matching is impossible across widely disparate groups, analysts should still measure and statistically control salient sample variables that may form rival explanations for group outcome differences. This unpacks whether valid cultural distinctions still exist after addressing sampling confounds.

In summary, sampling rigor in subject selection and representativeness support isolating genuine cultural differences apart from method factors, jeopardizing equivalence in cross-cultural research.

Designing questions and scales (a priori procedure)

Cross-cultural differences in response styles when using rating scales have posed persistent challenges. Once viewed as merely nuisance variables requiring statistical control, theory now conceptualizes styles like social desirability, acquiescence, and extremity as a meaningful individual and cultural variation in their own right (Smith, 2004).

For example, an agreeableness acquiescence tendency may be tracked with harmony values in East Asia. Efforts to simply “correct for” response style biases can thus discount substantive culture-linked variation in scale scores (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

Guidelines help adapt item design, instructions, response options, scale polarity, and survey properties to mitigate certain biases and equivocal interpretations when comparing scores across groups.

It remains important to assess response biases empirically through statistical controls or secondary measures. This evaluates whether cultural score differences reflect intended psychological constructs above and beyond style artifacts.

Appropriately contextualizing different response tendencies allows judiciously retaining stylistic variation attributable to cultural factors while isolating bias-threatening equivalence. Interpreting response biases as culturally informative rather than merely as problematic noise affords richer analysis.

In summary, response styles exhibit differential prevalence across cultures and should be analyzed contextually through both control and embrace rather than simplistically dismissed as invalid nuisance factors.

A Posteriori Procedures to Deal With Bias

After data collection, analysts can evaluate measurement equivalence and probe biases threatening the validity of cross-cultural score comparisons (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

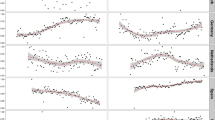

For structure-oriented studies examining relationships among variables, techniques like exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and multidimensional scaling assess similarities in conceptual dimensions across groups. This establishes structural equivalence.

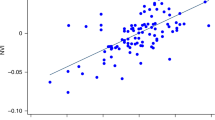

For comparing group mean scores, methods like differential item functioning, logistic regression, and standardization identify biases causing specific items or scales to function differently across cultures. Addressing biases promotes equivalence (Fischer & Fontaine, 2011; Sireci, 2011).

Multilevel modeling clarifies connections between culture-level ecological factors, individual psychological outcomes, and variables at other levels simultaneously. This leverages the nested nature of cross-cultural data (Matsumoto et al., 2007).

Supplementing statistical significance with effect sizes evaluates the real-world importance of score differences. Metrics like standardized mean differences and probability of superiority prevent overinterpreting minor absolute variations between groups (Matsumoto et al., 2001).

In summary, a posteriori analytic approach evaluates equivalence at structural and measurement levels and isolates biases interfering with valid score comparisons across cultures. Quantifying practical effects also aids replication and application.

Ethical Issues

Several ethical considerations span the research process when working across cultures. In design, conscious efforts must counteract subtle perpetuation of stereotypes through poorly constructed studies or ignorance of biases.

Extensive collaboration with cultural informants and members can alert researchers to pitfalls (Matsumoto & van de Vijver, 2021).

Recruiting participants ethically becomes more complex globally, as coercion risks increase without shared assumptions about voluntary participation rights.

Securing comprehensible, properly translated informed consent also grows more demanding, though remains an ethical priority even when local guidelines seem more lax. Confidentiality protections likewise prove more intricate across legal systems, requiring extra researcher care.

Studying sensitive topics like gender, sexuality, and human rights brings additional concerns in varying cultural contexts, necessitating localized ethical insight.

Analyzing and reporting data in a culturally conscious manner provides its own challenges, as both subtle biases and consciously overgeneralizing findings can spur harm.

Above all, ethical cross-cultural research requires recognizing communities as equal partners, not mere data sources. From first consultations to disseminating final analyses, maintaining indigenous rights and perspectives proves paramount to ethical engagement.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bond, M. H., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2011). Making scientific sense of cultural differences in psychological outcomes: Unpackaging the magnum mysteriosum. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 75–100). Cambridge University Press.

Fischer, R., & Fontaine, J. R. J. (2011). Methods for investigating structural equivalence. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 179–215). Cambridge University Press.

Hambleton, R. K., & Zenisky, A. L. (2011). Translating and adapting tests for cross-cultural assessments. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 46–74). Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, T., Shavitt, S., & Holbrook, A. (2011). Survey response styles across cultures. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 130–176). Cambridge University Press.

Matsumoto, D., Grissom, R., & Dinnel, D. (2001). Do between-culture differences really mean that people are different? A look at some measures of cultural effect size. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32 (4), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032004007

Matsumoto, D., & Juang, L. P. (2023). Culture and psychology (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Matsumoto, D., & van de Vijver, F.J.R. (2021). Cross-cultural research methods in psychology. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 97-113). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000318-005

Matsumoto, D., & Yoo, S. H. (2006). Toward a new generation of cross cultural research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1 (3), 234-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00014.x

Nezlek, J. (2011). Multilevel modeling. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 299–347). Cambridge University Press.

Shweder, R. A. (1999). Why cultural psychology? Ethos, 27 (1), 62–73.

Sireci, S. G. (2011). Evaluating test and survey items for bias across languages and cultures. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 216–243). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, P. B. (2004). Acquiescent response bias as an aspect of cultural communication style. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35 (1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022103260380

van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2009). Types of cross-cultural studies in cross-cultural psychology. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1017

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 40, 1989, review article, cross-cultural psychology: current research and trends.

- C Kagitcibasi , and J W Berry

- Vol. 40:493-531 (Volume publication date February 1989) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002425

- © Annual Reviews

Cross-Cultural Psychology: Current Research and Trends, Page 1 of 1

There is no abstract available.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Publication Date: 01 Feb 1989

Online Option

Sign in to access your institutional or personal subscription or get immediate access to your online copy - available in PDF and ePub formats

What Is Cross-Cultural Psychology? 11 Theories & Examples

Therefore, we must consider the effect of cultural learning on how we live, our drives, and our goals (Heine, 2010).

As Steven Heine (2010) writes, “on no occasions do we cast aside our cultural dressings to reveal the naked universal human mind.”

Culture should be taken into account when working with clients. According to cross-cultural psychology, it has broad impacts, including on our motivation, self-esteem, social behavior, and communication (Triandis, 2002).

This article explores the background of cross-cultural psychology’s search for possible behavioral and psychological universals.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is cross-cultural psychology, 7 theories and goals of the field, 4 examples of real-life applications, popular topics: 4 interesting research findings, differences between psychology and cultural psychology, a look at 8 programs, degrees, and training options, 4 books to learn more, positivepsychology.com’s related resources, a take-home message.

Cross-cultural psychology is not only fascinating, but insightful, shedding vital light on how and why we behave as we do. This offshoot of psychology involves the scientific study of variations in human behavior under the influence of a “shared way of life of a group of people,” known as cultural context (Berry, 2013).

The American Psychological Association describes cross-cultural psychology as being interested in the “similarities and variances in human behavior across different cultures” to identify “the different psychological constructs and explanatory models used by these cultures” (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2020).

Cross-cultural psychology became a sub-discipline of general psychology in the 1960s to prevent psychology from “becoming an entirely Western project” and “sought to test the universality of psychological laws via cultural comparative studies” (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

This cross-cultural approach to psychology involved recognizing culture as an external variable and exploring its impact on individual behavior. Over the decades that followed, the focus remained on identifying and testing the generalizability of using mainstream psychology approaches (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

It differs from cultural psychology , which aims to organize psychological processes by culture, because rather than looking for differences, cross-cultural psychology is ultimately searching for psychological universals. It seeks psychological patterns that we all share (Ellis & Stam, 2015; Berry, 2013).

Cross-cultural psychology borrows ideas, theories, and approaches from anthropology; it also recognizes the importance of analyzing international differences identified through social-psychological mechanisms.

And it’s important. We often assume that, psychologically speaking, all cultures are the same. Yet this is simply not the case (Berry, 2013).

When anthropologist turned psychologist Joseph Henrich began his research into cultural diversity, he became aware that Western populations were often unusual compared to others.

He also warns us of the risks of psychological bias toward WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) populations. We could be ignoring the psychological differences between peoples and wrongly assuming psychological patterns hold cross-culturally (Henrich, 2020).

As Henrich (2020) says, we should celebrate human diversity (psychological or otherwise), while noting that none of the psychological differences identified between cultures suggest one is better than the other or is immutable . Instead, human “psychology has changed over history and will continue to evolve” (Henrich, 2020).

- First and most importantly, test the field’s generality by looking at how different cultures respond to standard psychological tests.

- Next, remain open and observant of other cultures’ psychology, such as recognizing novel aspects of how they behave.

- Finally, integrate the knowledge (from the first two points) to create nearly universal psychology valid for a greater number of cultures.

Several psychological theories, models, and approaches have emerged from the ongoing research into cross-cultural psychology. They are often not distinct, but complementary, and include:

- Ecocultural model More recently, having reconfirmed the above goals, Berry proposed the ecocultural model.

It treats culture as a series of variables, existing at both individual and population levels, that interact to influence diversity in individual behavior (Berry, 2004, 2013; Ellis & Stam, 2015).

- Cultural syndromes Harry Triandis (2002) from the University of Illinois suggests that ecologies shape cultures, and cultures “influence the development of personalities.”

Cultural differences are identified, measured, and described as cultural syndromes (defined by their complexity, tightness, individualism, and collectivism) that can be used to group and organize cultures.

- Individualism and collectivism Over the years since Triandis’s initial work, individualism and collectivism have dominated research in the field, particularly regarding the differences identified through psychometric testing (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

Individualistic cultures recognize the individual’s needs (over the group’s), including individual goals and rights. By contrast, collectivist cultures are motivated by group goals, where individuals sacrifice their own needs for the group (Triandis, 2002).

- Natural science approach “Cross-cultural psychology relies on genetics” and neuroscience to provide a more complete picture of biological building materials that influence the behaviors and psychological features associated with different cultures (Shiraev & Levy, 2020).

Evolutionary theory provides further information regarding the evolutionary factors that influence human experience and behavior, laying the foundation for human culture (Shiraev & Levy, 2020).

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Cross-cultural psychology has been applied to (and affected) multiple, diverse areas of human care over the last few decades.

Narrative approach in psychotherapy

“Culture can be thought of as a community of individuals who see the world in a particular manner” (Howard, 1991). As a result, storytelling can be a powerful therapy approach, with narratives capturing the essence of human thought and cultural context. Narrative helps the psychotherapist not only relate to clients, but also understand the development of their identity.

Multicultural counseling and therapy

Cross-cultural psychology is valuable in informing mental healthcare. Indeed, “systems of care must adapt to cultural complexity so that services are acceptable and effective” (Gielen, Draguns, & Fish, 2008).

It is essential to begin with an awareness of biases and privilege, then form a deep understanding of the cultural influences on wellbeing and distress to improve service delivery (Gielen et al., 2008).

Learning and teaching

Combining insights from multiple disciplines, including cross-cultural psychology, has informed educational psychology and led to numerous teaching reforms. A broader cultural view encourages educators and researchers to revisit the biases of educational systems at various levels (Watkins, 2000).

Speech therapy

The development of speech is inevitably influenced by cultural factors. Knowledge gained from cross-cultural psychology provides greater insight into the needs and difficulties faced by children and improves the awareness of potential bias from clinicians and assessors (Carter et al., 2005).

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Cross-cultural psychology research has led to some fascinating findings in diverse areas, including the following.

Entrepreneurial career intentions

To better understand “the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention,” psychology has used cross-cultural research methods to confirm the importance of cultural context (including cultural identity and cultural variation) on career decisions (Moriano, Gorgievski, Laguna, Stephan, & Zarafshani, 2011).

Moriano et al. (2011) found that sociocultural attitudes were the strongest predictors of individuals wanting to become entrepreneurs. Indeed, an entrepreneur in one culture may be seen as more legitimate than in another, impacting uptake (Moriano et al., 2011).

Differences between individualistic and collectivist cultures

There are some very recognizable differences between individualistic and collectivist cultures (Church, 2000).

In collectivist cultures:

- People tend to focus on context rather than their internal processes when predicting others’ behavior.

- Individual behaviors are less consistent across different situations.

- Behavior is more easily predicted from “norms and roles than from attitudes.”

Cross-cultural psychology has been applied to the field of creativity with some interesting results.

According to Glăveanu (2010), “culture and the individual are both open systems” and the two are mutually dependent and involved in the creative process.

Glăveanu (2010) suggests that the community serves as a social context for producing the artistic outcome and contributes to evaluating creativity.

Cohen, Wu, and Miller (2016) suggest “that a greater attention to both Western and Eastern religions in cross-cultural psychology can be illuminating regarding religion and culture” and insightful regarding how national cultures interact.

Collectivist cultures encourage people to develop interdependent selves, connected in meaningful ways to those around them. By contrast, in individualistic cultures, people think of themselves “as relatively distinct from close others” (Cohen et al., 2016).

Furthermore, some religions are collectivistic, focusing on tradition and community-based religious practice, while others are individualistic, expressing personal faith and one’s relationship with God.

What is cross-cultural psychology? – Audioversity

“Cross-cultural psychology arose as a division of mainstream psychology that deliberately extended the mainstream research framework to test the universality of psychological principles” (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

However, there are several differences between cross-cultural psychology and other branches of psychology. Indeed, much of general psychology focuses on the impact of other people on behavior (such as family, relationships, and friends), yet it ignore culture’s influence. On the other hand, cross-cultural psychology looks at human behavior within the culture, using it as the context for study (Shiraev & Levy, 2020).

It is also important to note that while cross-cultural and cultural psychology are both extensions of general psychology, despite the similar names, they have different focuses (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

Cross-cultural psychology has, since the 1970s, formed part of the established, mainstream, and empirical psychology dedicated to individualistic explanations of psychological phenomena. Culture becomes a way of testing the universality of psychological processes (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

Cultural psychology is interested in determining how local cultures (including their social practices) influence and shape how our psychological processes develop (Ellis & Stam, 2015).

Several organizations offer training influenced by cross-cultural psychology theory and research findings, including:

- Cross-cultural training Global Integration provides tailored training opportunities that include understanding the impact of cultural styles, recognizing the benefits of cultural diversity, and seeing the value in more inclusive virtual meetings.

- Country-specific cross-culture training Living Institute offers training to help collaborate across cultures and seek value in diversity.

- Building cross-cultural skills for global working Culturewise specializes in cross-cultural and cultural awareness training including, leadership, management, and communication skills.

While few graduate programs focus entirely on cross-cultural psychology, the following master’s degrees offer valuable insights into areas related to the field.

- Social and cultural psychology The London School of Economics and Political Science , UK, offers a master’s degree that explores how culture and society shape how we think, behave, and relate to one another.

- Culture, adaptive leadership, & transcultural competence The University of Amsterdam , Netherlands, has a master’s program that includes cross-cultural psychology. Specifically, it covers how culture shapes psychological functioning and how to design programs and culturally sensitive interventions.

- Mental health: Cultural psychology and psychiatry Queen Mary University , London, UK, offers a master’s degree that explores sociocultural factors in mental health and mental illness.

- Diversity and inclusion leadership Tufts University , Medford, USA, offers a master’s degree in becoming a strong, informed, and skilled leader versed in diversity and inclusion.

- Criminal justice – Diversity, inclusion and belonging Saint Joseph’s University , Philadelphia, USA, offers a master’s degree in criminal justice with a concentration in diversity, inclusion , and belonging.

The following four books are some of our favorites on the subject of cross-cultural psychology. Combined, they provide a broad and deep insight into the research, theories, and application.

1. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications – John Berry, Ype Poortinga, Seger Breugelmans, Athanasios Chasiotis, and David Sam

This new edition of one of the leading textbooks on cross-cultural psychology targets students new to the field and more experienced practitioners wishing to update their skills.

Written by a team of distinguished international authors, the book’s 18 chapters present an exhaustive discussion of cross-cultural psychology approaches and their application.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Critical Thinking and Contemporary Applications – Eric Shiraev and David Levy

This new seventh edition of this popular text on cross-cultural psychology is conversational in style and uses a critical thinking framework to develop analytical skills.

The book contains a wealth of recent references to keep you updated about the field. Along with covering the theory, it explores how to apply the learnings in various multicultural contexts including teaching, healthcare, social work, and counseling.

3. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives – Kenneth Keith

Kenneth Keith does an excellent job at placing key areas of psychology within a cultural perspective. An introductory section is followed by the research and theories of cross-cultural psychology, and then the book moves into clinical and social principles and applications.

This second edition is rich in research and examples and will provide the reader with a comprehensive overview of the discipline and its integration with the rest of psychology.

4. The Cross-Cultural Coaching Kaleidoscope – Jennifer Plaister-Ten

In Jennifer Plaister-Ten’s excellent book, we learn about the impact of cross-cultural psychology research findings on coaching and how to work and practice in a global market.

This is an incredibly valuable text for coaches working in a multicultural environment and raising awareness of cultural influences for their clients’ benefit.

Our cultural context influences who we are, including our personality, strengths, values, and behavior.

We have several resources to get to know yourself better.

- Exploring Character Strengths These 10 questions are valuable ways of recognizing and exploring your character strengths.

- Core Beliefs CBT Formulation We typically interpret another’s actions based on our personal core beliefs. Challenging those beliefs with this CBT formulation can help you manage your unhelpful responses to the perceived negative behavior of others.

- Spotting Good Traits We often miss opportunities to recognize or praise others for the many good traits that they possess. Understanding them can help our interactions with other people.

- Basic Needs Satisfaction in General Scale Emotions provide feedback on whether we are meeting our personal needs. This assessment allows clients to better satisfy their personal needs by building their self-awareness.

- How To Use Your Strengths Strengths can be under- or overused. In this exercise , we explore each strength and consider various ways to apply them in daily life.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Psychological phenomena vary significantly across cultural contexts and have different degrees of universality. And yet, a great deal of psychological research has been performed in Western countries – a high percentage in the United States – impacting and biasing our understanding of human psychology (Heine, 2010).

Cross-cultural psychology is particularly valuable, as it helps address this narrow view by looking for what psychological phenomena are universal. It “examines psychological diversity and the underlying reasons for such diversity” (Shiraev & Levy, 2020).

Findings from research studies provide insight into cultural norms and behavior, including how social and cultural forces impact our activities (Shiraev & Levy, 2020).

Cross-cultural psychology aims to do more than merely identify differences between cultural groups; it seeks to uncover what is common or shared.

Explore some of the mental health theories , research, and applications involved in cross-cultural psychology. While it is a complex and vast subject, it has far-reaching value in our direct dealings with individuals from different cultures and can be used to promote awareness in our clients that may benefit their multicultural relationships.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2020). Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://dictionary.apa.org/cross-cultural-psychology

- Berry, J. W. (2004). An ecocultural perspective on the development of competence. In R. J. Sternberg & E. Grigorenko (Eds.), Culture and competence (pp. 3–22). American Psychological Association.

- Berry, J. (2013). Achieving a global psychology. Canadian Psychology , 54 , 55–61.

- Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Breugelmans, S. M., Chasiotis, A., & Sam, D. L. (2011). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Berry, J., Poortinga, Y. H., Marshall, S. H., & Dasen, P. R. (1992). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Carter, J. A., Lees, J. A., Murira, G. M., Gona, J., Neville, B. G. R., & Newton, C. R. J. C. (2005). Issues in the development of cross-cultural assessments of speech and language for children. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders , 40 (4), 385–401.

- Church, A. T. (2000). Culture and personality: Toward an integrated cultural trait psychology. Journal of Personality , 69 , 651–703.

- Cohen, A. B., Wu, M. S., & Miller, J. (2016). Religion and culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology , 47 (9), 1236–1249.

- Ellis, B. D., & Stam, H. J. (2015). Crisis? What crisis? Cross-cultural psychology’s appropriation of cultural psychology. Culture & Psychology , 21 (3), 293–317.

- Gielen, U. P., Draguns, J. G., & Fish, J. M. (Eds.). (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy: Investigating practice from scientific, historical, and cultural perspectives. Principles of multicultural counseling and therapy . Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2010). Principles for a cultural psychology of creativity. Culture & Psychology , 16 (2), 147–163.

- Heine, S. J. (2010). Cultural psychology. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 1423–1464). John Wiley & Sons.

- Henrich, J. P. (2020). The WEIRDest people in the world: How the West became psychologically peculiar and particularly prosperous . Penguin Books.

- Howard, G. S. (1991). Culture tales: A narrative approach to thinking, cross-cultural psychology, and psychotherapy. American Psychologist , 46 (3), 187–197.

- Keith, K. D. (Ed.). (2019). Cross-cultural psychology: Contemporary themes and perspectives (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Moriano, J. A., Gorgievski, M., Laguna, M., Stephan, U., & Zarafshani, K. (2011). A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Career Development , 39 (2), 162–185.

- Plaister-Ten, J. (2016). The cross-cultural coaching kaleidoscope. Routledge.

- Shiraev, E., & Levy, D. A. (2020). Cross-cultural psychology: Critical thinking and contemporary applications (7th ed.). Routledge.

- Triandis, H. C. (2002). Cultural influences on personality. Annual Review of Psychology , 53 , 133–160.

- Watkins, D. (2000). Learning and teaching: A cross-cultural perspective. School Leadership & Management , 20 (2), 161–173.

- Wei, Y., Spencer-Rodgers, J., Anderson, E., & Peng, K. (2020). The effects of a cross-cultural psychology course on perceived intercultural competence. Teaching of Psychology .

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

A very useful article

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Hierarchy of Needs: A 2024 Take on Maslow’s Findings

One of the most influential theories in human psychology that addresses our quest for wellbeing is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. While Maslow’s theory of [...]

Emotional Development in Childhood: 3 Theories Explained

We have all witnessed a sweet smile from a baby. That cute little gummy grin that makes us smile in return. Are babies born with [...]

Using Classical Conditioning for Treating Phobias & Disorders

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell? Classical conditioning, a psychological phenomenon first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the late 19th century, has proven to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Cross-Cultural Psychology?

Cross-cultural psychology is a branch of psychology that looks at how cultural factors influence human behavior. While many aspects of human thought and behavior are universal, cultural differences can lead to often surprising differences in how people think, feel, and act.

Some cultures, for example, might stress individualism and the importance of personal autonomy. Other cultures may place a higher value on collectivism and cooperation among members of the group. Such differences can play an influential role in many aspects of life.

This article discusses the history of cross-cultural psychology, different types of cross-cultural psychology, and applications of this field. It also discusses the impact it has had on the understanding of human psychology.

What Is Culture?

Culture refers to many characteristics of a group of people, including attitudes , behaviors, customs, religious beliefs, and values that are transmitted from one generation to the next. Cultures throughout the world share many similarities but are also marked by considerable differences. For example, while people of all cultures experience happiness , how this feeling is expressed varies from one culture to the next.

The goal of cross-cultural psychologists is to look at both universal behaviors and unique behaviors to identify the ways in which culture influences behavior, family life, education, social experiences, and other areas.

History of Cross-Cultural Psychology

Cross-cultural psychology is an important topic. Researchers strive to understand both the differences and similarities among people of various cultures throughout the world.

The International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology (IACCP) was established in 1972, and this branch of psychology has continued to grow and develop since that time. Today, increasing numbers of psychologists investigate how behavior differs among various cultures throughout the world.

After prioritizing European and North American research for many years, Western researchers began to question whether many of the observations and ideas once believed to be universal might apply to cultures outside of these areas. Could their findings and assumptions about human psychology be biased based on the sample from which their observations were drawn?

Many of the findings described by psychologists are focused on a specific group of people, which some researchers have dubbed Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, often referred to by the acronym WEIRD.

As a result, cross-cultural psychologists suggest that many observations about human thought and behavior may only be generalizable to specific subgroups. To develop a broader, richer understanding of people that can be applied to a wider variety of cultural settings, it is essential for researchers to also look at people from diverse cultures.

Despite recognizing that research has a strong Western bias, evidence suggests that this bias persists today. According to one analysis of six prominent psychology research journals, around 90% of participants in psychology research are drawn from Western, industrialized countries, 60% of which were American.

Cross-cultural psychologists work to rectify many of the biases that may exist in the current research and determine if the phenomena that appear in European and North American cultures also appear in other parts of the world.

Types of Cross-Cultural Psychology

Many cross-cultural psychologists choose to focus on one of two approaches:

- The etic approach studies culture through an "outsider" perspective, applying one "universal" set of concepts and measurements to all cultures.

- The emic approach studies culture using an "insider" perspective, analyzing concepts within the specific context of the observed culture.

It is also common for cross-cultural psychologists to take a combined emic-etic approach.

Meanwhile, some cross-cultural psychologists also study something known as ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism refers to a tendency to use your own culture as the standard by which to judge and evaluate other cultures.

In other words, taking an ethnocentric point of view means using your understanding of your own culture to gauge what is "normal." This can lead to biases and a tendency to view cultural differences as abnormal or in a negative light. It can also make it difficult to see how your cultural background influences your behaviors.

Cross-cultural psychologists often look at how ethnocentrism influences our behaviors and thoughts, including how we interact with individuals from other cultures.

Psychologists are also concerned with how ethnocentrism can influence the research process. For example, a study might be criticized for having an ethnocentric bias.

Topics in Cross-Cultural Psychology

Cross-cultural psychology explores many subjects, focusing on how culture affects different aspects of development, thought, and behavior. Some important areas of study include:

- Emotions : This field seeks to understand if all people experience emotions the same way and if emotional expressions are universal.

- Language acquisition : This area explores whether language development follows the same path throughout different cultures.

- Child development : This topic investigates how culture affects child development and whether different cultural practices influence the course of development. For example, psychologists might investigate how child-rearing practices differ in various cultures and how these practices impact variables such as achievement, self-esteem, and subjective well-being .

- Personality : This area researches the degree to which different aspects of personality might be influenced or tied to cultural influences.

- Social behavior : Cultural norms and expectations can have a powerful effect on social behavior, which this topic seeks to understand.

- Family and social relationships : Familial and other interpersonal relationships can also be heavily influenced by societies and cultures.

- Mental health: Professionals who provide mental health services should embrace cultural sensitivity. There can be significant differences in emotional expression, social behaviors, and spiritual beliefs across cultures that are "normal" within the context of the person's culture and should not be treated as a symptom or disorder.

Cross-cultural psychology seeks to understand how culture influences many different aspects of human emotion, thought, and behavior. Cross-cultural psychologists often study child development, personality, and social relationships. Mental health professionals should be culturally sensitive to differing norms in the context of culture.

Uses for Cross-Cultural Psychology

Cross-cultural psychology touches on a wide range of topics, so students interested in other psychology topics may choose to also focus on this area of psychology. For example, a child psychologist might study how child-rearing practices in different cultures impact development.

Cross-cultural psychology can help teachers, educators, and curriculum designers who create multicultural education lessons and materials learn more about how cultural differences affect student learning, achievement, and motivation.

In the field of social psychology, applying a cross-cultural view might lead researchers to study how social cognition might vary in an individualist culture versus a collectivist culture. Do people from each culture rely on the same types of social cues? What cultural differences might influence how people perceive each other ?

Impact of Cross-Cultural Psychology

Many other branches of psychology focus on how parents, friends, and other people impact human behavior. However, most do not take into account the powerful impact that culture may have on individual human actions.