- Research Group

- Job Seekers

Research Tips

Understanding the Difference between Research Questions and Objectives

January 13, 2023

When conducting research, clearly understanding the difference between research questions and objectives is important. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they refer to two distinct aspects of the research process.

Research questions are broad statements that guide the overall direction of the research. They identify the main problem or area of inquiry that the research will address. For example, a research question might be, "What is the impact of social media on teenage mental health?" This question sets the stage for the research and helps to define the scope of the study.

- Research questions are more general and open-ended, while objectives are specific and measurable.

- Research questions identify the main problem or area of inquiry, while objectives define the specific outcomes that the researcher is looking to achieve.

- Research questions help define the study's scope, while objectives help guide the research process.

- Research questions are often used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge, while objectives are used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research.

- Research questions and objectives are not mutually exclusive, but well-defined research questions should lead to specific objectives necessary to answer the question.

On the other hand, research objectives are specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve. They are used to guide the research process and help to define the specific outcomes that the researcher is looking to achieve. For example, an objective for the above research question might be "To determine the correlation between social media usage and rates of depression in teenagers." This objective is more specific and measurable than the research question and helps define the specific outcomes that the researcher is looking to achieve.

It is important to note that research questions and objectives are not mutually exclusive; a study can have one or several questions and objectives. A well-defined research question should lead to specific objectives necessary to answer the question.

In summary, research questions and objectives are two distinct aspects of the research process. Research questions are broad statements that guide the overall direction of the research, while research objectives are specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve. Understanding these two terms' differences is essential for conducting effective and meaningful research.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What Are Research Objectives and How to Write Them (with Examples)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Research is at the center of everything researchers do, and setting clear, well-defined research objectives plays a pivotal role in guiding scholars toward their desired outcomes. Research papers are essential instruments for researchers to effectively communicate their work. Among the many sections that constitute a research paper, the introduction plays a key role in providing a background and setting the context. 1 Research objectives, which define the aims of the study, are usually stated in the introduction. Every study has a research question that the authors are trying to answer, and the objective is an active statement about how the study will answer this research question. These objectives help guide the development and design of the study and steer the research in the appropriate direction; if this is not clearly defined, a project can fail!

Research studies have a research question, research hypothesis, and one or more research objectives. A research question is what a study aims to answer, and a research hypothesis is a predictive statement about the relationship between two or more variables, which the study sets out to prove or disprove. Objectives are specific, measurable goals that the study aims to achieve. The difference between these three is illustrated by the following example:

- Research question : How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

- Research hypothesis : Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

- Research objective : To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

This article discusses the importance of clear, well-thought out objectives and suggests methods to write them clearly.

What is the introduction in research papers?

Research objectives are usually included in the introduction section. This section is the first that the readers will read so it is essential that it conveys the subject matter appropriately and is well written to create a good first impression. A good introduction sets the tone of the paper and clearly outlines the contents so that the readers get a quick snapshot of what to expect.

A good introduction should aim to: 2,3

- Indicate the main subject area, its importance, and cite previous literature on the subject

- Define the gap(s) in existing research, ask a research question, and state the objectives

- Announce the present research and outline its novelty and significance

- Avoid repeating the Abstract, providing unnecessary information, and claiming novelty without accurate supporting information.

Why are research objectives important?

Objectives can help you stay focused and steer your research in the required direction. They help define and limit the scope of your research, which is important to efficiently manage your resources and time. The objectives help to create and maintain the overall structure, and specify two main things—the variables and the methods of quantifying the variables.

A good research objective:

- defines the scope of the study

- gives direction to the research

- helps maintain focus and avoid diversions from the topic

- minimizes wastage of resources like time, money, and energy

Types of research objectives

Research objectives can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives . 4 General objectives state what the research expects to achieve overall while specific objectives break this down into smaller, logically connected parts, each of which addresses various parts of the research problem. General objectives are the main goals of the study and are usually fewer in number while specific objectives are more in number because they address several aspects of the research problem.

Example (general objective): To investigate the factors influencing the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

Example (specific objective): To assess the influence of firm size on the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

In addition to this broad classification, research objectives can be grouped into several categories depending on the research problem, as given in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of research objectives

| Exploratory | Explores a previously unstudied topic, issue, or phenomenon; aims to generate ideas or hypotheses |

| Descriptive | Describes the characteristics and features of a particular population or group |

| Explanatory | Explains the relationships between variables; seeks to identify cause-and-effect relationships |

| Predictive | Predicts future outcomes or events based on existing data samples or trends |

| Diagnostic | Identifies factors contributing to a particular problem |

| Comparative | Compares two or more groups or phenomena to identify similarities and differences |

| Historical | Examines past events and trends to understand their significance and impact |

| Methodological | Develops and improves research methods and techniques |

| Theoretical | Tests and refines existing theories or helps develop new theoretical perspectives |

Characteristics of research objectives

Research objectives must start with the word “To” because this helps readers identify the objective in the absence of headings and appropriate sectioning in research papers. 5,6

- A good objective is SMART (mostly applicable to specific objectives):

- Specific—clear about the what, why, when, and how

- Measurable—identifies the main variables of the study and quantifies the targets

- Achievable—attainable using the available time and resources

- Realistic—accurately addresses the scope of the problem

- Time-bound—identifies the time in which each step will be completed

- Research objectives clarify the purpose of research.

- They help understand the relationship and dissimilarities between variables.

- They provide a direction that helps the research to reach a definite conclusion.

How to write research objectives?

Research objectives can be written using the following steps: 7

- State your main research question clearly and concisely.

- Describe the ultimate goal of your study, which is similar to the research question but states the intended outcomes more definitively.

- Divide this main goal into subcategories to develop your objectives.

- Limit the number of objectives (1-2 general; 3-4 specific)

- Assess each objective using the SMART

- Start each objective with an action verb like assess, compare, determine, evaluate, etc., which makes the research appear more actionable.

- Use specific language without making the sentence data heavy.

- The most common section to add the objectives is the introduction and after the problem statement.

- Add the objectives to the abstract (if there is one).

- State the general objective first, followed by the specific objectives.

Formulating research objectives

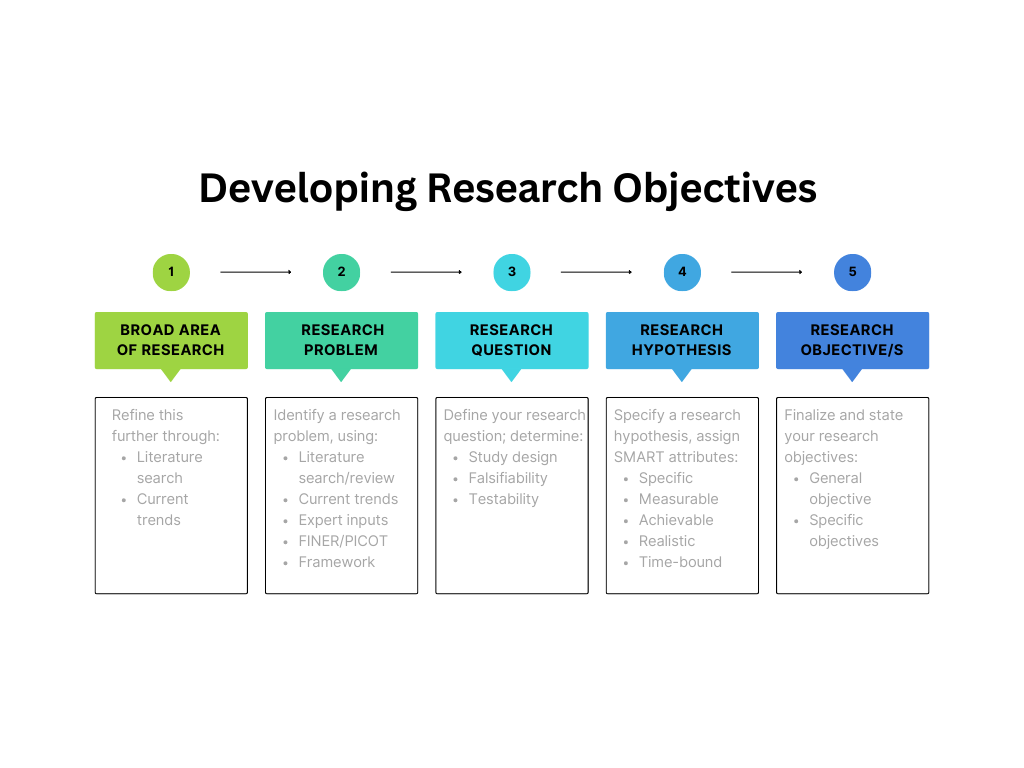

Formulating research objectives has the following five steps, which could help researchers develop a clear objective: 8

- Identify the research problem.

- Review past studies on subjects similar to your problem statement, that is, studies that use similar methods, variables, etc.

- Identify the research gaps the current study should cover based on your literature review. These gaps could be theoretical, methodological, or conceptual.

- Define the research question(s) based on the gaps identified.

- Revise/relate the research problem based on the defined research question and the gaps identified. This is to confirm that there is an actual need for a study on the subject based on the gaps in literature.

- Identify and write the general and specific objectives.

- Incorporate the objectives into the study.

Advantages of research objectives

Adding clear research objectives has the following advantages: 4,8

- Maintains the focus and direction of the research

- Optimizes allocation of resources with minimal wastage

- Acts as a foundation for defining appropriate research questions and hypotheses

- Provides measurable outcomes that can help evaluate the success of the research

- Determines the feasibility of the research by helping to assess the availability of required resources

- Ensures relevance of the study to the subject and its contribution to existing literature

Disadvantages of research objectives

Research objectives also have few disadvantages, as listed below: 8

- Absence of clearly defined objectives can lead to ambiguity in the research process

- Unintentional bias could affect the validity and accuracy of the research findings

Key takeaways

- Research objectives are concise statements that describe what the research is aiming to achieve.

- They define the scope and direction of the research and maintain focus.

- The objectives should be SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.

- Clear research objectives help avoid collection of data or resources not required for the study.

- Well-formulated specific objectives help develop the overall research methodology, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and utilization.

- Research objectives should cover all aspects of the problem statement in a coherent way.

- They should be clearly stated using action verbs.

Frequently asked questions on research objectives

Q: what’s the difference between research objectives and aims 9.

A: Research aims are statements that reflect the broad goal(s) of the study and outline the general direction of the research. They are not specific but clearly define the focus of the study.

Example: This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.

Research objectives focus on the action to be taken to achieve the aims. They make the aims more practical and should be specific and actionable.

Example: To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation.

Q: What are the examples of research objectives, both general and specific?

A: Here are a few examples of research objectives:

- To identify the antiviral chemical constituents in Mumbukura gitoniensis (general)

- To carry out solvent extraction of dried flowers of Mumbukura gitoniensis and isolate the constituents. (specific)

- To determine the antiviral activity of each of the isolated compounds. (specific)

- To examine the extent, range, and method of coral reef rehabilitation projects in five shallow reef areas adjacent to popular tourist destinations in the Philippines.

- To investigate species richness of mammal communities in five protected areas over the past 20 years.

- To evaluate the potential application of AI techniques for estimating best-corrected visual acuity from fundus photographs with and without ancillary information.

- To investigate whether sport influences psychological parameters in the personality of asthmatic children.

Q: How do I develop research objectives?

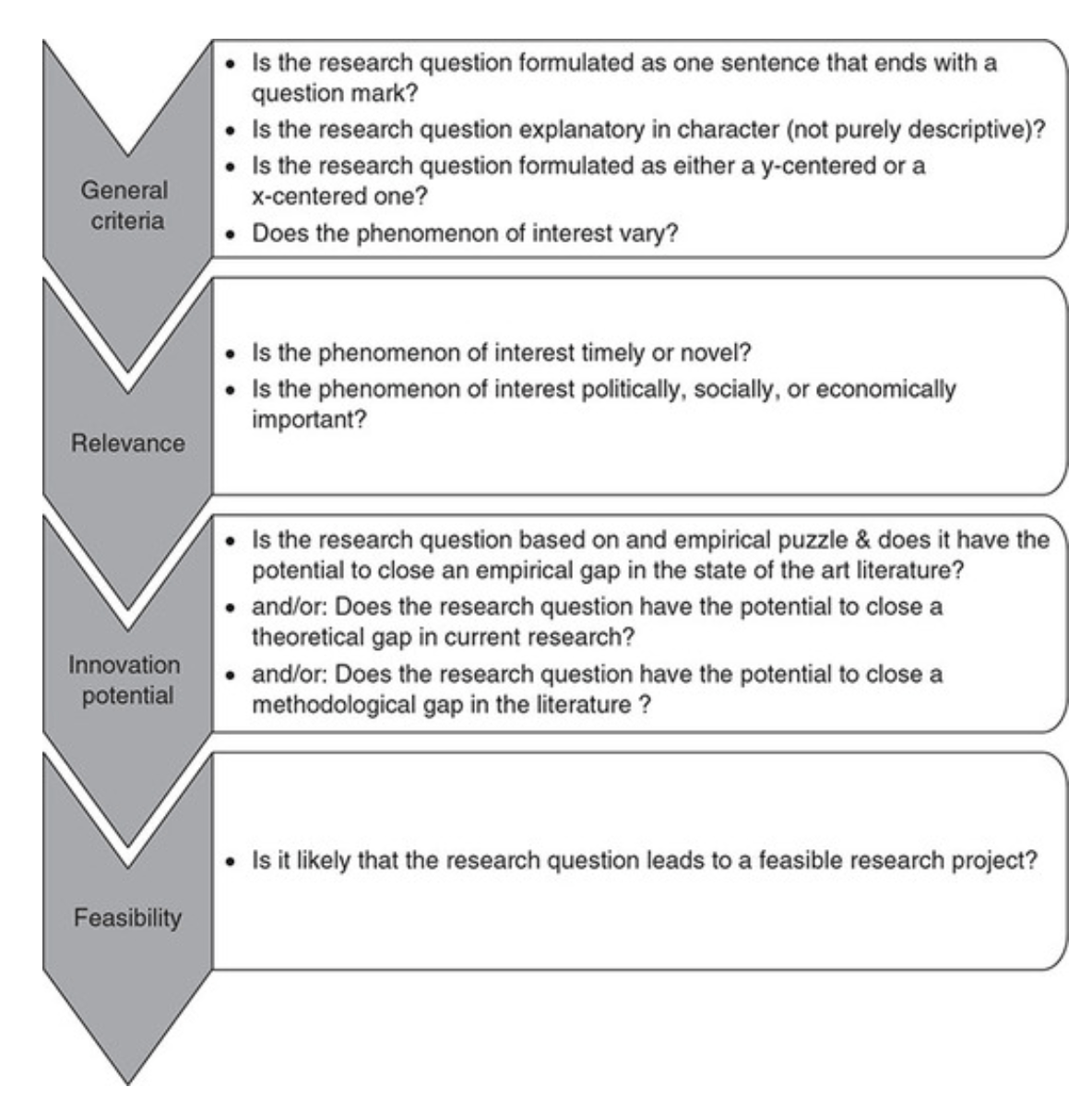

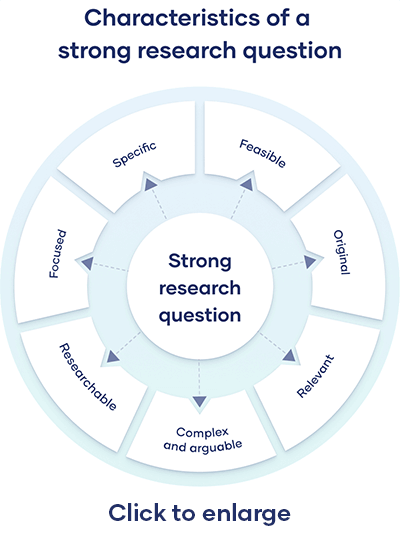

A: Developing research objectives begins with defining the problem statement clearly, as illustrated by Figure 1. Objectives specify how the research question will be answered and they determine what is to be measured to test the hypothesis.

Q: Are research objectives measurable?

A: The word “measurable” implies that something is quantifiable. In terms of research objectives, this means that the source and method of collecting data are identified and that all these aspects are feasible for the research. Some metrics can be created to measure your progress toward achieving your objectives.

Q: Can research objectives change during the study?

A: Revising research objectives during the study is acceptable in situations when the selected methodology is not progressing toward achieving the objective, or if there are challenges pertaining to resources, etc. One thing to keep in mind is the time and resources you would have to complete your research after revising the objectives. Thus, as long as your problem statement and hypotheses are unchanged, minor revisions to the research objectives are acceptable.

Q: What is the difference between research questions and research objectives? 10

| Broad statement; guide the overall direction of the research | Specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve |

| Identify the main problem | Define the specific outcomes the study aims to achieve |

| Used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge | Used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research |

| Not mutually exclusive with research objectives | Should be directly related to the research question |

| Example: | Example: |

Q: Are research objectives the same as hypotheses?

A: No, hypotheses are predictive theories that are expressed in general terms. Research objectives, which are more specific, are developed from hypotheses and aim to test them. A hypothesis can be tested using several methods and each method will have different objectives because the methodology to be used could be different. A hypothesis is developed based on observation and reasoning; it is a calculated prediction about why a particular phenomenon is occurring. To test this prediction, different research objectives are formulated. Here’s a simple example of both a research hypothesis and research objective.

Research hypothesis : Employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

Research objective : To assess whether employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

To summarize, research objectives are an important part of research studies and should be written clearly to effectively communicate your research. We hope this article has given you a brief insight into the importance of using clearly defined research objectives and how to formulate them.

- Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surg. 2010 Aug;53(4):278-81.

- Abbadia J. How to write an introduction for a research paper. Mind the Graph website. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://mindthegraph.com/blog/how-to-write-an-introduction-for-a-research-paper/

- Writing a scientific paper: Introduction. UCI libraries website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249903

- Research objectives—Types, examples and writing guide. Researchmethod.net website. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://researchmethod.net/research-objectives/#:~:text=They%20provide%20a%20clear%20direction,track%20and%20achieve%20their%20goals .

- Bartle P. SMART Characteristics of good objectives. Community empowerment collective website. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://cec.vcn.bc.ca/cmp/modules/pd-smar.htm

- Research objectives. Studyprobe website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.studyprobe.in/2022/08/research-objectives.html

- Corredor F. How to write objectives in a research paper. wikiHow website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-Objectives-in-a-Research-Proposal

- Research objectives: Definition, types, characteristics, advantages. AccountingNest website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.accountingnest.com/articles/research/research-objectives

- Phair D., Shaeffer A. Research aims, objectives & questions. GradCoach website. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://gradcoach.com/research-aims-objectives-questions/

- Understanding the difference between research questions and objectives. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://board.researchersjob.com/blog/research-questions-and-objectives

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

How Does R Discovery’s Interplatform Capability Enhance Research Accessibility

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

| Quantitative research questions | Quantitative research hypotheses |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research questions | Simple hypothesis |

| Comparative research questions | Complex hypothesis |

| Relationship research questions | Directional hypothesis |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| Hypothesis-testing | |

| Qualitative research questions | Qualitative research hypotheses |

| Contextual research questions | Hypothesis-generating |

| Descriptive research questions | |

| Evaluation research questions | |

| Explanatory research questions | |

| Exploratory research questions | |

| Generative research questions | |

| Ideological research questions | |

| Ethnographic research questions | |

| Phenomenological research questions | |

| Grounded theory questions | |

| Qualitative case study questions |

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

| Quantitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Measures responses of subjects to variables | |

| - Presents variables to measure, analyze, or assess | |

| What is the proportion of resident doctors in the hospital who have mastered ultrasonography (response of subjects to a variable) as a diagnostic technique in their clinical training? | |

| Comparative research question | |

| - Clarifies difference between one group with outcome variable and another group without outcome variable | |

| Is there a difference in the reduction of lung metastasis in osteosarcoma patients who received the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group with outcome variable) compared with osteosarcoma patients who did not receive the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group without outcome variable)? | |

| - Compares the effects of variables | |

| How does the vitamin D analogue 22-Oxacalcitriol (variable 1) mimic the antiproliferative activity of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (variable 2) in osteosarcoma cells? | |

| Relationship research question | |

| - Defines trends, association, relationships, or interactions between dependent variable and independent variable | |

| Is there a relationship between the number of medical student suicide (dependent variable) and the level of medical student stress (independent variable) in Japan during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

| Quantitative research hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Simple hypothesis | |

| - Predicts relationship between single dependent variable and single independent variable | |

| If the dose of the new medication (single independent variable) is high, blood pressure (single dependent variable) is lowered. | |

| Complex hypothesis | |

| - Foretells relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables | |

| The higher the use of anticancer drugs, radiation therapy, and adjunctive agents (3 independent variables), the higher would be the survival rate (1 dependent variable). | |

| Directional hypothesis | |

| - Identifies study direction based on theory towards particular outcome to clarify relationship between variables | |

| Privately funded research projects will have a larger international scope (study direction) than publicly funded research projects. | |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| - Nature of relationship between two variables or exact study direction is not identified | |

| - Does not involve a theory | |

| Women and men are different in terms of helpfulness. (Exact study direction is not identified) | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| - Describes variable interdependency | |

| - Change in one variable causes change in another variable | |

| A larger number of people vaccinated against COVID-19 in the region (change in independent variable) will reduce the region’s incidence of COVID-19 infection (change in dependent variable). | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| - An effect on dependent variable is predicted from manipulation of independent variable | |

| A change into a high-fiber diet (independent variable) will reduce the blood sugar level (dependent variable) of the patient. | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| - A negative statement indicating no relationship or difference between 2 variables | |

| There is no significant difference in the severity of pulmonary metastases between the new drug (variable 1) and the current drug (variable 2). | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| - Following a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis predicts a relationship between 2 study variables | |

| The new drug (variable 1) is better on average in reducing the level of pain from pulmonary metastasis than the current drug (variable 2). | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory | |

| Dairy cows fed with concentrates of different formulations will produce different amounts of milk. | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| - Assumption about the value of population parameter or relationship among several population characteristics | |

| - Validity tested by a statistical experiment or analysis | |

| The mean recovery rate from COVID-19 infection (value of population parameter) is not significantly different between population 1 and population 2. | |

| There is a positive correlation between the level of stress at the workplace and the number of suicides (population characteristics) among working people in Japan. | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| - Offers or proposes an explanation with limited or no extensive evidence | |

| If healthcare workers provide more educational programs about contraception methods, the number of adolescent pregnancies will be less. | |

| Hypothesis-testing (Quantitative hypothesis-testing research) | |

| - Quantitative research uses deductive reasoning. | |

| - This involves the formation of a hypothesis, collection of data in the investigation of the problem, analysis and use of the data from the investigation, and drawing of conclusions to validate or nullify the hypotheses. | |

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

| Qualitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Contextual research question | |

| - Ask the nature of what already exists | |

| - Individuals or groups function to further clarify and understand the natural context of real-world problems | |

| What are the experiences of nurses working night shifts in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic? (natural context of real-world problems) | |

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Aims to describe a phenomenon | |

| What are the different forms of disrespect and abuse (phenomenon) experienced by Tanzanian women when giving birth in healthcare facilities? | |

| Evaluation research question | |

| - Examines the effectiveness of existing practice or accepted frameworks | |

| How effective are decision aids (effectiveness of existing practice) in helping decide whether to give birth at home or in a healthcare facility? | |

| Explanatory research question | |

| - Clarifies a previously studied phenomenon and explains why it occurs | |

| Why is there an increase in teenage pregnancy (phenomenon) in Tanzania? | |

| Exploratory research question | |

| - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated to have a deeper understanding of the research problem | |

| What factors affect the mental health of medical students (areas that have not yet been fully investigated) during the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

| Generative research question | |

| - Develops an in-depth understanding of people’s behavior by asking ‘how would’ or ‘what if’ to identify problems and find solutions | |

| How would the extensive research experience of the behavior of new staff impact the success of the novel drug initiative? | |

| Ideological research question | |

| - Aims to advance specific ideas or ideologies of a position | |

| Are Japanese nurses who volunteer in remote African hospitals able to promote humanized care of patients (specific ideas or ideologies) in the areas of safe patient environment, respect of patient privacy, and provision of accurate information related to health and care? | |

| Ethnographic research question | |

| - Clarifies peoples’ nature, activities, their interactions, and the outcomes of their actions in specific settings | |

| What are the demographic characteristics, rehabilitative treatments, community interactions, and disease outcomes (nature, activities, their interactions, and the outcomes) of people in China who are suffering from pneumoconiosis? | |

| Phenomenological research question | |

| - Knows more about the phenomena that have impacted an individual | |

| What are the lived experiences of parents who have been living with and caring for children with a diagnosis of autism? (phenomena that have impacted an individual) | |

| Grounded theory question | |

| - Focuses on social processes asking about what happens and how people interact, or uncovering social relationships and behaviors of groups | |

| What are the problems that pregnant adolescents face in terms of social and cultural norms (social processes), and how can these be addressed? | |

| Qualitative case study question | |

| - Assesses a phenomenon using different sources of data to answer “why” and “how” questions | |

| - Considers how the phenomenon is influenced by its contextual situation. | |

| How does quitting work and assuming the role of a full-time mother (phenomenon assessed) change the lives of women in Japan? | |

| Qualitative research hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis-generating (Qualitative hypothesis-generating research) | |

| - Qualitative research uses inductive reasoning. | |

| - This involves data collection from study participants or the literature regarding a phenomenon of interest, using the collected data to develop a formal hypothesis, and using the formal hypothesis as a framework for testing the hypothesis. | |

| - Qualitative exploratory studies explore areas deeper, clarifying subjective experience and allowing formulation of a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach. | |

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

| Variables | Unclear and weak statement (Statement 1) | Clear and good statement (Statement 2) | Points to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research question | Which is more effective between smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion? | “Moreover, regarding smoke moxibustion versus smokeless moxibustion, it remains unclear which is more effective, safe, and acceptable to pregnant women, and whether there is any difference in the amount of heat generated.” | 1) Vague and unfocused questions |

| 2) Closed questions simply answerable by yes or no | |||

| 3) Questions requiring a simple choice | |||

| Hypothesis | The smoke moxibustion group will have higher cephalic presentation. | “Hypothesis 1. The smoke moxibustion stick group (SM group) and smokeless moxibustion stick group (-SLM group) will have higher rates of cephalic presentation after treatment than the control group. | 1) Unverifiable hypotheses |

| Hypothesis 2. The SM group and SLM group will have higher rates of cephalic presentation at birth than the control group. | 2) Incompletely stated groups of comparison | ||

| Hypothesis 3. There will be no significant differences in the well-being of the mother and child among the three groups in terms of the following outcomes: premature birth, premature rupture of membranes (PROM) at < 37 weeks, Apgar score < 7 at 5 min, umbilical cord blood pH < 7.1, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and intrauterine fetal death.” | 3) Insufficiently described variables or outcomes | ||

| Research objective | To determine which is more effective between smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion. | “The specific aims of this pilot study were (a) to compare the effects of smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion treatments with the control group as a possible supplement to ECV for converting breech presentation to cephalic presentation and increasing adherence to the newly obtained cephalic position, and (b) to assess the effects of these treatments on the well-being of the mother and child.” | 1) Poor understanding of the research question and hypotheses |

| 2) Insufficient description of population, variables, or study outcomes |

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

| Variables | Unclear and weak statement (Statement 1) | Clear and good statement (Statement 2) | Points to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research question | Does disrespect and abuse (D&A) occur in childbirth in Tanzania? | How does disrespect and abuse (D&A) occur and what are the types of physical and psychological abuses observed in midwives’ actual care during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania? | 1) Ambiguous or oversimplistic questions |

| 2) Questions unverifiable by data collection and analysis | |||

| Hypothesis | Disrespect and abuse (D&A) occur in childbirth in Tanzania. | Hypothesis 1: Several types of physical and psychological abuse by midwives in actual care occur during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. | 1) Statements simply expressing facts |

| Hypothesis 2: Weak nursing and midwifery management contribute to the D&A of women during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. | 2) Insufficiently described concepts or variables | ||

| Research objective | To describe disrespect and abuse (D&A) in childbirth in Tanzania. | “This study aimed to describe from actual observations the respectful and disrespectful care received by women from midwives during their labor period in two hospitals in urban Tanzania.” | 1) Statements unrelated to the research question and hypotheses |

| 2) Unattainable or unexplorable objectives |

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

Research Question 101 📖

Everything you need to know to write a high-quality research question

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2023

If you’ve landed on this page, you’re probably asking yourself, “ What is a research question? ”. Well, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll explain what a research question is , how it’s differen t from a research aim, and how to craft a high-quality research question that sets you up for success.

Research Question 101

What is a research question.

- Research questions vs research aims

- The 4 types of research questions

- How to write a research question

- Frequently asked questions

- Examples of research questions

As the name suggests, the research question is the core question (or set of questions) that your study will (attempt to) answer .

In many ways, a research question is akin to a target in archery . Without a clear target, you won’t know where to concentrate your efforts and focus. Essentially, your research question acts as the guiding light throughout your project and informs every choice you make along the way.

Let’s look at some examples:

What impact does social media usage have on the mental health of teenagers in New York?

How does the introduction of a minimum wage affect employment levels in small businesses in outer London?

How does the portrayal of women in 19th-century American literature reflect the societal attitudes of the time?

What are the long-term effects of intermittent fasting on heart health in adults?

As you can see in these examples, research questions are clear, specific questions that can be feasibly answered within a study. These are important attributes and we’ll discuss each of them in more detail a little later . If you’d like to see more examples of research questions, you can find our RQ mega-list here .

Research Questions vs Research Aims

At this point, you might be asking yourself, “ How is a research question different from a research aim? ”. Within any given study, the research aim and research question (or questions) are tightly intertwined , but they are separate things . Let’s unpack that a little.

A research aim is typically broader in nature and outlines what you hope to achieve with your research. It doesn’t ask a specific question but rather gives a summary of what you intend to explore.

The research question, on the other hand, is much more focused . It’s the specific query you’re setting out to answer. It narrows down the research aim into a detailed, researchable question that will guide your study’s methods and analysis.

Let’s look at an example:

Research Aim: To explore the effects of climate change on marine life in Southern Africa.

Research Question: How does ocean acidification caused by climate change affect the reproduction rates of coral reefs?

As you can see, the research aim gives you a general focus , while the research question details exactly what you want to find out.

Need a helping hand?

Types of research questions

Now that we’ve defined what a research question is, let’s look at the different types of research questions that you might come across. Broadly speaking, there are (at least) four different types of research questions – descriptive , comparative , relational , and explanatory .

Descriptive questions ask what is happening. In other words, they seek to describe a phenomena or situation . An example of a descriptive research question could be something like “What types of exercise do high-performing UK executives engage in?”. This would likely be a bit too basic to form an interesting study, but as you can see, the research question is just focused on the what – in other words, it just describes the situation.

Comparative research questions , on the other hand, look to understand the way in which two or more things differ , or how they’re similar. An example of a comparative research question might be something like “How do exercise preferences vary between middle-aged men across three American cities?”. As you can see, this question seeks to compare the differences (or similarities) in behaviour between different groups.

Next up, we’ve got exploratory research questions , which ask why or how is something happening. While the other types of questions we looked at focused on the what, exploratory research questions are interested in the why and how . As an example, an exploratory research question might ask something like “Why have bee populations declined in Germany over the last 5 years?”. As you can, this question is aimed squarely at the why, rather than the what.

Last but not least, we have relational research questions . As the name suggests, these types of research questions seek to explore the relationships between variables . Here, an example could be something like “What is the relationship between X and Y” or “Does A have an impact on B”. As you can see, these types of research questions are interested in understanding how constructs or variables are connected , and perhaps, whether one thing causes another.

Of course, depending on how fine-grained you want to get, you can argue that there are many more types of research questions , but these four categories give you a broad idea of the different flavours that exist out there. It’s also worth pointing out that a research question doesn’t need to fit perfectly into one category – in many cases, a research question might overlap into more than just one category and that’s okay.

The key takeaway here is that research questions can take many different forms , and it’s useful to understand the nature of your research question so that you can align your research methodology accordingly.

How To Write A Research Question

As we alluded earlier, a well-crafted research question needs to possess very specific attributes, including focus , clarity and feasibility . But that’s not all – a rock-solid research question also needs to be rooted and aligned . Let’s look at each of these.

A strong research question typically has a single focus. So, don’t try to cram multiple questions into one research question; rather split them up into separate questions (or even subquestions), each with their own specific focus. As a rule of thumb, narrow beats broad when it comes to research questions.

Clear and specific

A good research question is clear and specific, not vague and broad. State clearly exactly what you want to find out so that any reader can quickly understand what you’re looking to achieve with your study. Along the same vein, try to avoid using bulky language and jargon – aim for clarity.

Unfortunately, even a super tantalising and thought-provoking research question has little value if you cannot feasibly answer it. So, think about the methodological implications of your research question while you’re crafting it. Most importantly, make sure that you know exactly what data you’ll need (primary or secondary) and how you’ll analyse that data.

A good research question (and a research topic, more broadly) should be rooted in a clear research gap and research problem . Without a well-defined research gap, you risk wasting your effort pursuing a question that’s already been adequately answered (and agreed upon) by the research community. A well-argued research gap lays at the heart of a valuable study, so make sure you have your gap clearly articulated and that your research question directly links to it.

As we mentioned earlier, your research aim and research question are (or at least, should be) tightly linked. So, make sure that your research question (or set of questions) aligns with your research aim . If not, you’ll need to revise one of the two to achieve this.

FAQ: Research Questions

Research question faqs, how many research questions should i have, what should i avoid when writing a research question, can a research question be a statement.

Typically, a research question is phrased as a question, not a statement. A question clearly indicates what you’re setting out to discover.

Can a research question be too broad or too narrow?

Yes. A question that’s too broad makes your research unfocused, while a question that’s too narrow limits the scope of your study.

Here’s an example of a research question that’s too broad:

“Why is mental health important?”

Conversely, here’s an example of a research question that’s likely too narrow:

“What is the impact of sleep deprivation on the exam scores of 19-year-old males in London studying maths at The Open University?”

Can I change my research question during the research process?

How do i know if my research question is good.

A good research question is focused, specific, practical, rooted in a research gap, and aligned with the research aim. If your question meets these criteria, it’s likely a strong question.

Is a research question similar to a hypothesis?

Not quite. A hypothesis is a testable statement that predicts an outcome, while a research question is a query that you’re trying to answer through your study. Naturally, there can be linkages between a study’s research questions and hypothesis, but they serve different functions.

How are research questions and research objectives related?

The research question is a focused and specific query that your study aims to answer. It’s the central issue you’re investigating. The research objective, on the other hand, outlines the steps you’ll take to answer your research question. Research objectives are often more action-oriented and can be broken down into smaller tasks that guide your research process. In a sense, they’re something of a roadmap that helps you answer your research question.

Need some inspiration?

If you’d like to see more examples of research questions, check out our research question mega list here . Alternatively, if you’d like 1-on-1 help developing a high-quality research question, consider our private coaching service .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .