Server Busy

Our servers are getting hit pretty hard right now. To continue shopping, enter the characters as they are shown in the image below.

Type the characters you see in this image:

Select your cookie preferences

We use cookies and similar tools that are necessary to enable you to make purchases, to enhance your shopping experiences and to provide our services, as detailed in our Cookie notice . We also use these cookies to understand how customers use our services (for example, by measuring site visits) so we can make improvements.

If you agree, we'll also use cookies to complement your shopping experience across the Amazon stores as described in our Cookie notice . Your choice applies to using first-party and third-party advertising cookies on this service. Cookies store or access standard device information such as a unique identifier. The 96 third parties who use cookies on this service do so for their purposes of displaying and measuring personalized ads, generating audience insights, and developing and improving products. Click "Decline" to reject, or "Customise" to make more detailed advertising choices, or learn more. You can change your choices at any time by visiting Cookie preferences , as described in the Cookie notice. To learn more about how and for what purposes Amazon uses personal information (such as Amazon Store order history), please visit our Privacy notice .

- School & Educational Supplies

- Early Childhood Education Materials

Sorry, there was a problem.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Critical Thinking Educator Wheel

| Brand | Mentoring Minds |

| Batteries required? | No |

| Item weight | 1 Ounces |

About this item

- Provides easy-to-use access to content that supports educators as they in weave critical thinking into lesson plans for all subjects at all grade levels

- Includes questioning prompts based on Bloom’s Taxonomy to help teachers design dynamic lesson plans

- Offers definitions and Power Words for building quality lessons and questioning prompts to stimulate thinking and spark discussion

Product information

Technical details.

| Manufacturer recommended age | 18 years and up |

|---|---|

| Item model number | 30100 |

| Batteries Required? | No |

| Batteries included? | No |

| ASIN | 1627632646 |

Additional Information

| Customer Reviews | 4.7 out of 5 stars |

|---|---|

| Date First Available | 18 May 2022 |

Warranty & Support

Product description

The Critical Thinking Educator Wheel features questioning prompts based on Bloom’s Taxonomy and other information to help teachers design dynamic lesson plans. It includes definitions, Power Words for building quality lessons, and questioning prompts to stimulate thinking and spark discussion.

Looking for specific info?

Customer reviews.

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 87%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 13%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings, help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyses reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- UK Modern Slavery Statement

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell on Amazon Handmade

- Associates Programme

- Fulfilment by Amazon

- Seller Fulfilled Prime

- Advertise Your Products

- Independently Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- The Amazon Barclaycard

- Credit Card

- Amazon Money Store

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Payment Methods Help

- Shop with Points

- Top Up Your Account

- Top Up Your Account in Store

- COVID-19 and Amazon

- Track Packages or View Orders

- Delivery Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Amazon Mobile App

- Customer Service

- Accessibility

- Conditions of Use & Sale

- Privacy Notice

- Cookies Notice

- Interest-Based Ads Notice

Sorry, there was a problem.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Critical Thinking Educator Wheel

Return policy.

Tap on the category links below for the associated return window and exceptions (if any) for returns.

| Brand | Mentoring Minds |

| Genre | Educational |

| Batteries required? | No |

| Item weight | 1 Ounces |

About this item

- Provides easy-to-use access to content that supports educators as they in weave critical thinking into lesson plans for all subjects at all grade levels

- Includes questioning prompts based on Bloom’s Taxonomy to help teachers design dynamic lesson plans

- Offers definitions and Power Words for building quality lessons and questioning prompts to stimulate thinking and spark discussion

Product information

Technical details.

| Manufacturer recommended age | 18 years and up |

|---|---|

| Item model number | 30100 |

| Batteries Required? | No |

| Batteries Included? | No |

| ASIN | 1627632646 |

Additional Information

| Customer Reviews | 4.7 out of 5 stars |

|---|---|

| Date First Available | 23 December 2022 |

Warranty & Support

Product description

The Critical Thinking Educator Wheel features questioning prompts based on Bloom’s Taxonomy and other information to help teachers design dynamic lesson plans. It includes definitions, Power Words for building quality lessons, and questioning prompts to stimulate thinking and spark discussion.

Looking for specific info?

Customer reviews.

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 87%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 13%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 87% 0% 13% 0% 0% 0%

No customer reviews

- About Amazon

- Amazon Science

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Your Addresses

- Protect and build your brand

- Sell on Amazon

- Fulfillment by Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Shipping & Delivery

- Returns & Replacements

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Amazon App Download

- Conditions of Use & Sale

- Privacy Notice

- Interest-Based Ads

Server Busy

Our servers are getting hit pretty hard right now. To continue shopping, enter the characters as they are shown in the image below.

Type the characters you see in this image:

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Our Future Depends on Critical Thinking

Empower the Next Generation to Think Critically. Teach Them to ThinkUp!

Critical Thinking

Students who are taught to think critically will have the skill set to succeed in the classroom today, build confidence for upcoming assessments, and for the challenges they’ll face in the rapidly evolving future.

The 9 Traits of Critical Thinking™

Each trait contributes to the development of skillful thinking and an environment that supports deeper learning. Students become more effective critical thinkers and problem solvers when they apply the 9 Traits: Adapt, Examine, Create, Communicate, Collaborate, Reflect, Strive, Link, and Inquire.

ThinkUp! Studios

Join Our Critical Thinking Community

This groundbreaking content hub shares the hows and whys of critical thinking. Learn more about lesson plans, teacher tips, innovative ideas for thinking critically, and the latest news about our products from a community of educators committed to critical thinking.

Our Products

We equip educators with the resources to teach students to think critically. ThinkUp! offers educators and students a path for continual growth that leads to improved student achievement and success in the future.

Critical Thinking Success Stories

Hear from Those Who Matter Most: Educators on the Frontlines of Our Future

Success Depends on Critical Thinking

Success at School

Success for Life

Subscribe to join our community of educators and start receiving useful teacher tips, lesson plans, innovative ideas for thinking critically, and the latest news about our products.

We’re Here to Help

Contact Our Customer Support Team

(800) 585-5258

Video Series

- Analyze the logic of a problem or issue

- Analyze the logic of an article, essay, or text

- Analyze the logic of any book of nonfiction

- Evaluate an Author’s Reasoning

- Analyze the logic of a character in a novel

- Analyze the logic of a profession, subject, or discipline

- Analyze the logic of a concept or idea

- Distinguishing Inferences and Assumptions

- Thinking Through Conflicting Ideas

- Could you elaborate further?

- Could you give me an example?

- Could you illustrate what you mean?

- How could we check on that?

- How could we find out if that is true?

- How could we verify or test that?

- Could you be more specific?

- Could you give me more details?

- Could you be more exact?

- How does that relate to the problem?

- How does that bear on the question?

- How does that help us with the issue?

- What factors make this a difficult problem?

- What are some of the complexities of this question?

- What are some of the difficulties we need to deal with?

- Do we need to look at this from another perspective?

- Do we need to consider another point of view?

- Do we need to look at this in other ways?

- Does all this make sense together?

- Does your first paragraph fit in with your last?

- Does what you say follow from the evidence?

- Is this the most important problem to consider?

- Is this the central idea to focus on?

- Which of these facts are most important?

- Do I have any vested interest in this issue?

- Am I sympathetically representing the viewpoints of others?

Everyone thinks; it is our nature to do so. But much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed, or downright prejudiced. If we want to think well, we must understand at least the udiments of thought, the most basic structures out of which all thinking is made. We must learn how to take thinking apart.

All Thinking Is Defined by the Eight Elements That Make It Up. Eight basic structures are present in all thinking: Whenever we think, we think for a purpose within a point of view based on assumptions leading to implications and consequences. We use concepts, ideas and theories to interpret data, facts, and experiences in order to answer questions, solve problems, and resolve issues.

- generates purposes

- raises questions

- uses information

- utilizes concepts

- makes inferences

- makes assumptions

- generates implications

- embodies a point of view

- What is your, my, their purpose in doing________?

- What is the objective of this assignment (task, job, experiment, policy, strategy, etc.)?

- Should we question, refine, modify our purpose (goal, objective, etc.)?

- What is the purpose of this meeting (chapter, relationship, action)?

- What is your central aim in this line of thought?

- What is the purpose of education?

- Why did you say…?

- Take time to state your purpose clearly.

- Distinguish your purpose from related purposes.

- Check periodically to be sure you are still on target.

- Choose significant and realistic purposes.

- What is the question I am trying to answer?

- What important questions are embedded in the issue?

- Is there a better way to put the question?

- Is this question clear? Is it complex?

- I am not sure exactly what question you are asking. Could you explain it?

- The question in my mind is this: How do you see the question?

- What kind of question is this? Historical? Scientific? Ethical? Political? Economic? Or…?

- What would we have to do to settle this question?

- State the question at issue clearly and precisely.

- Express the question in several ways to clarify its meaning.

- Break the question into sub-questions.

- Distinguish questions that have definitive answers from those that are a matter of opinion or that require multiple viewpoints.

- What information do I need to answer this question?

- What data are relevant to this problem?

- Do we need to gather more information?

- Is this information relevant to our purpose or goal?

- On what information are you basing that comment?

- What experience convinced you of this? Could your experience be distorted?

- How do we know this information (data, testimony) is accurate?

- Have we left out any important information that we need to consider?

- Restrict your claims to those supported by the data you have.

- Search for information that opposes your position as well as information that supports it.

- Make sure that all information used is clear, accurate and relevant.

- Make sure you have gathered sufficient information.

- What conclusions am I coming to?

- Is my inference logical?

- Are there other conclusions I should consider?

- Does this interpretation make sense?

- Does our solution necessarily follow from our data?

- How did you reach that conclusion?

- What are you basing your reasoning on?

- Is there an alternative plausible conclusion?

- Given all the facts what is the best possible conclusion?

- How shall we interpret these data?

- Infer only what the evidence implies.

- Check inferences for their consistency with each other.

- Identify assumptions underlying your inferences.

- What idea am I using in my thinking? Is this idea causing problems for me or for others?

- I think this is a good theory, but could you explain it more fully?

- What is the main hypothesis you are using in your reasoning?

- Are you using this term in keeping with established usage?

- What main distinctions should we draw in reasoning through this problem?

- What idea is this author using in his or her thinking? Is there a problem with it?

- Identify key concepts and explain them clearly.

- Consider alternative concepts or alternative definitions of concepts.

- Make sure you are using concepts with precision.

- What am I assuming or taking for granted?

- Am I assuming something I shouldn’t?

- What assumption is leading me to this conclusion?

- What is… (this policy, strategy, explanation) assuming?

- What exactly do sociologists (historians, mathematicians, etc.) take for granted?

- What is being presupposed in this theory?

- What are some important assumptions I make about my roommate, my friends, my parents, my instructors, my country?

- Clearly identify your assumptions and determine whether they are justifiable.

- Consider how your assumptions are shaping your point of view.

- If I decide to do “X”, what things might happen?

- If I decide not to do “X”, what things might happen?

- What are you implying when you say that?

- What is likely to happen if we do this versus that?

- Are you implying that…?

- How significant are the implications of this decision?

- What, if anything, is implied by the fact that a much higher percentage of poor people are in jail than wealthy people?

- Trace the implications and consequences that follow from your reasoning.

- Search for negative as well as positive implications.

- Consider all possible consequences.

- How am I looking at this situation? Is there another way to look at it that I should consider?

- What exactly am I focused on? And how am I seeing it?

- Is my view the only reasonable view? What does my point of view ignore?

- Have you ever considered the way ____(Japanese, Muslims, South Americans, etc.) view this?

- Which of these possible viewpoints makes the most sense given the situation?

- Am I having difficulty looking at this situation from a viewpoint with which I disagree?

- What is the point of view of the author of this story?

- Do I study viewpoints that challenge my personal beliefs?

- Identify your point of view.

- Seek other points of view and identify their strengths as well as weaknesses.

- Strive to be fairminded in evaluating all points of view.

The 30-second briefing: What is the TASC approach?

What is the TASC approach to learning?

“TASC” stands for “thinking actively in a social context”. The approach was developed by Belle Wallace in the 1980s as a way to develop thinking and problem-solving skills in students.

How does it work?

Wallace presents her framework in the form of a wheel, where each section of the wheel represents a different opportunity to revise and develop thinking skills.

Working in groups, students make their way clockwise around the wheel, moving through the stages, which range from “identifying” and “deciding” to “implementing” and “learning from experience”.

Wallace was clear that the focus is on the complexity of thinking and on guiding learners to develop their skills.

So, the children direct the learning themselves?

Essentially, yes. Wallace has grouped the stages of the group-work process to give a more robust strategy that the learners lead themselves.

It’s the students’ responsibility to work through the stages after you’ve introduced the problem or learning context, but there is a strong framework for learners to follow.

What about the research? Is there much to back this up?

TASC is an eclectic approach that draws on many of the “big hitter” principles in education. It borrows from philosophy for children and certainly has a constructivist feel.

While there are case studies that support the method and a great deal of neuroscience has been included in developing the approach, its impact remains to be seen.

Should I be trying this?

If you feel that either you or your learners need support in critical thinking or problem-solving, then this approach will walk you through the process nicely. It is the equivalent of adding stabilisers to your problem-solving bike, before you’re ready to whip them off and try something more complex or less rigid.

Will it have an impact in my classroom?

That depends on you and your children. It provides a sound and well-thought-out structure to scaffold learning, particularly if problem solving is something that you feel you need to develop. However, many of us will do this naturally as part of our teaching.

Where can I find out more?

Check out the TASC website and have a look at the case and impact studies produced by schools, such as this one .

Sarah Wright is a senior lecturer at Edge Hill University. She tweets as @Sarah__wright1

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook

Want to keep reading for free?

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Programs & Services

- Delphi Center

Ideas to Action (i2a)

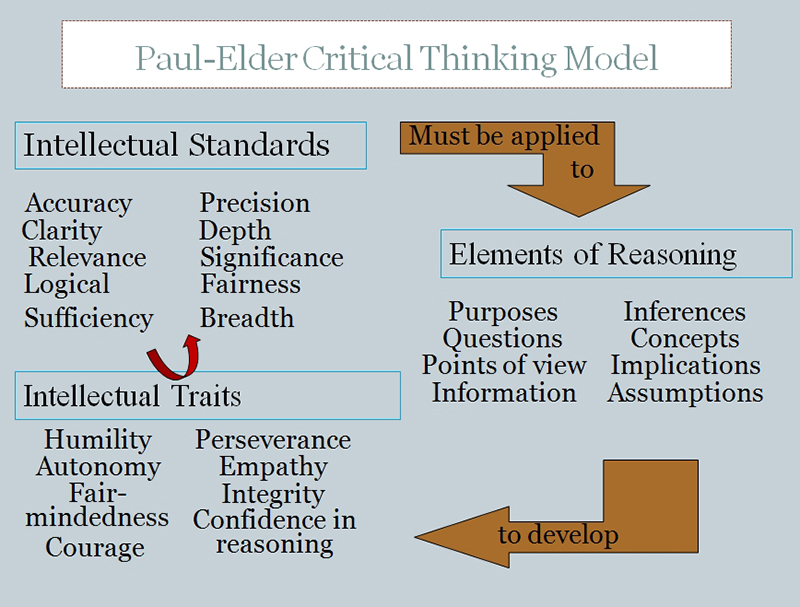

- Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them. (Paul and Elder, 2001). The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought

According to Paul and Elder (1997), there are two essential dimensions of thinking that students need to master in order to learn how to upgrade their thinking. They need to be able to identify the "parts" of their thinking, and they need to be able to assess their use of these parts of thinking.

Elements of Thought (reasoning)

The "parts" or elements of thinking are as follows:

- All reasoning has a purpose

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem

- All reasoning is based on assumptions

- All reasoning is done from some point of view

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequences

Universal Intellectual Standards

The intellectual standards that are to these elements are used to determine the quality of reasoning. Good critical thinking requires having a command of these standards. According to Paul and Elder (1997 ,2006), the ultimate goal is for the standards of reasoning to become infused in all thinking so as to become the guide to better and better reasoning. The intellectual standards include:

Intellectual Traits

Consistent application of the standards of thinking to the elements of thinking result in the development of intellectual traits of:

- Intellectual Humility

- Intellectual Courage

- Intellectual Empathy

- Intellectual Autonomy

- Intellectual Integrity

- Intellectual Perseverance

- Confidence in Reason

- Fair-mindedness

Characteristics of a Well-Cultivated Critical Thinker

Habitual utilization of the intellectual traits produce a well-cultivated critical thinker who is able to:

- Raise vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely

- Gather and assess relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively

- Come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2010). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

- SACS & QEP

- Planning and Implementation

- What is Critical Thinking?

- Why Focus on Critical Thinking?

- Culminating Undergraduate Experience

- Community Engagement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is i2a?

Copyright © 2012 - University of Louisville , Delphi Center

- Our Mission

Sharing the Depth of Knowledge Framework With Students

Many teachers use Norman Webb’s framework in developing assignments, but it can also be shared with students to help them develop literacy skills.

Educators spend a great deal of time analyzing diagnostic, formative, and summative performance data to individualize instruction for their students. In my current role as a staff developer, I’m often asked about how to do this while meeting curriculum expectations and benchmarks and supporting critical thinking skills. I find myself discussing the concept of critical thinking in many contexts, including curriculum planning, lesson ideas, and assessment.

I like to use Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DoK) framework to unpack what critical thinking might look like in a variety of contexts to support literacy skills, working with teachers to identify links between the Depth of Knowledge levels and the Common Core State Standards .

I often use Gerald Aungst’s “ Using Webb’s Depth of Knowledge to Increase Rigor ” in my work with teachers, because the article explains the four levels outlined in Webb’s framework for cognitive rigor in the classroom. Aungst makes clear recommendations for teachers, including: reflecting on tasks, sorting the tasks we ask students to do, working collaboratively to review student groupings, analyzing groupings, and reworking Level 1 and 2 tasks to Level 3 or 4. One important point he makes is that “DoK levels are not sequential.” In other words, students don’t need to fully master a Level 1 in order to move on to a Level 2.

While Aungst provides actionable ideas for teachers, I would like to propose a road map that includes students in the process. When it comes to enhancing literacy practices in the classroom, there is a great deal of research that supports explicit instruction, as well as the role of student engagement and achievement. The authors of a recent guide to improving adolescent literacy have five recommendations based on this research: Teachers should provide vocabulary instruction, comprehension strategy instruction, opportunities to discuss surrounding texts, work that enhances student motivation and engagement, and individualized intervention resources. Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DoK) can be a useful tool in acting on all of these recommendations.

Webb’s DoK provides students with language tools to access text and classroom discourse. I’ve found that helping students develop their understanding of the language within the DoK has been beneficial in supporting literacy and can also support students as they prepare for Common Core–aligned assessments. In fact, helping students review and code sample questions can help them figure out which strategies they might need to apply in order to answer the questions.

In my experience, students like using the DoK framework to figure out how it aligns with their assignments. They also enjoy developing their own questions to ask their peers. These kinds of activities ask students to critically think about what kinds of questions they will ask, and in doing so, engage in rich metacognitive learning experiences.

This can be particularly empowering as students are increasingly faced with the rigors of high stakes testing. Many assessments require students to critically analyze texts, make inferences, prove their responses using textual evidence, develop a claim or analyze an author’s claim, and make comparisons.

Implementing Webb’s Depth of Knowledge With Students

- Explicitly teach students about the different cognitive levels and ensure that they understand what each of the terms means. Then, have them analyze question prompts for DoK level and assess what they are being asked to do—e.g., are they asked to categorize, infer, or predict?

- Work with students on unpacking strategies that help them engage in that cognitive activity. Consider creating process charts with them to identify the skills needed. For example, what kinds of skills and tools might we need to analyze a character’s motivation in a story?

- Give students the opportunity to develop their own questions aligned to the DoK levels that can be used in collaborative settings through group work, in Socratic seminars , or through a carousel , for example.

- Offer students the opportunity to reflect on their strengths—are they really strong in certain areas, but want to further develop in others?

- Have students code their assignments and questions. This is empowering and offers students a chance to reflect on what they are being asked to do.

These suggestions can be implemented with elementary and secondary students. I’ve seen teachers create and display posters and anchor charts using the DoK language and use that language throughout their lessons. This direct linking of the academic language embeds the framework so that it becomes a fluid part of classroom discussions. I’ve seen elementary students adeptly use the language as a way of explaining their own learning. We can view Webb’s framework as one of many tools that can be used to help students develop their own understanding of what rigor means, and in so doing, give them a vocabulary to articulate their own goals and learning experiences. [ Editor’s note: This article has been updated to remove references to an image called the Depth of Knowledge wheel, which misrepresents Norman Webb’s ideas.]

- Call for Volunteers!

- Our Team of Presenters

- Dr. Richard Paul

- Dr. Linda Elder

- Dr. Gerald Nosich

- Contact Us - Office Information

- Permission to Use Our Work

- Create a CriticalThinking.Org Account

- Contributions to the Foundation for Critical Thinking

- Testimonials

- Center for Critical Thinking

The National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking

- International Center for the Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

| |

A Draft Statement of Principles

Goals The goals of the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking Instruction are as follows:

- To articulate, preserve, and foster high standards of research, scholarship, and instruction in critical thinking.

- To articulate the standards upon which "quality" thinking is based and the criteria by means of which thinking, and instruction for thinking, can be appropriately cultivated and assessed.

- To assess programs which claim to foster higher-order critical thinking.

- To disseminate information that aids educators and others in identifying quality critical thinking programs and approaches which ground the reform and restructuring of education on a systematic cultivation of disciplined universal and domain specific intellectual standards.

Founding Principles

- There is an intimate interrelation between knowledge and thinking.

- Knowing that something is so is not simply a matter of believing that it is so, it also entails being justified in that belief (Definition: Knowledge is justified true belief).

- There are general, as well as domain-specific, standards for the assessment of thinking.

- To achieve knowledge in any domain, it is essential to think critically.

- Critical thinking is based on articulable intellectual standards and hence is intrinsically subject to assessment by those standards.

- Criteria for the assessment of thinking in all domains are based on such general standards as: clarity, precision, accuracy, relevance, significance, fairness, logic, depth, and breadth, evidentiary support, probability, predictive or explanatory power. These standards, and others, are embedded not only in the history of the intellectual and scientific communities, but also in the self-assessing behavior of reasonable persons in everyday life. It is possible to teach all subjects in such a way as to encourage the use of these intellectual standards in both professional and personal life.

- Instruction in critical thinking should increasingly enable students to assess both their own thought and action and that of others by reference, ultimately, to standards such as those above. It should lead progressively, in other words, to a disciplining of the mind and to a self-chosen commitment to a life of intellectual and moral integrity.

- Instruction in all subject domains should result in the progressive disciplining of the mind with respect to the capacity and disposition to think critically within that domain. Hence, instruction in science should lead to disciplined scientific thinking; instruction in mathematics should lead to disciplined mathematical thinking; instruction in history should lead to disciplined historical thinking; and in a parallel manner in every discipline and domain of learning.

- Disciplined thinking with respect to any subject involves the capacity on the part of the thinker to recognize, analyze, and assess the basic elements of thought: the purpose or goal of the thinking; the problem or question at issue; the frame of reference or points of view involved; assumptions made; central concepts and ideas at work; principles or theories used; evidence, data, or reasons advanced, claims made and conclusions drawn; inferences, reasoning, and lines of formulated thought; and implications and consequences involved.

- Critical reading, writing, speaking, and listening are academically essential modes of learning. To be developed generally they must be systematically cultivated in a variety of subject domains as well as with respect to interdisciplinary issues. Each are modes of thinking which are successful to the extent that they are disciplined and guided by critical thought and reflection.

- The earlier that children develop sensitivity to the standards of sound thought and reasoning, the more likely they will develop desirable intellectual habits and become open-minded persons responsive to reasonable persuasion.

- Education - in contrast to training, socialization, and indoctrination - implies a process conducive to critical thought and judgment. It is intrinsically committed to the cultivation of reasonability and rationality.

History and Philosophy Critical thinking is integral to education and rationality and, as an idea, is traceable, ultimately, to the teaching practices — and the educational ideal implicit in them — of Socrates of ancient Greece. It has played a seminal role in the emergence of academic disciplines, as well as in the work of discovery of those who created them. Knowledge, in other words, has been discovered and verified by the distinguished critical thinkers of intellectual, scientific, and technological history. For the majority of the idea's history, however, critical thinking has been "buried," a conception in practice without an explicit name. Most recently, however, it has undergone something of an awakening, a coming-out, a first major social expression, signaling perhaps a turning-point in its history. This awakening is correlated with a growing awareness that if education is to produce critical thinkers en mass, if it is to globally cultivate nations of skilled thinkers and innovators rather than a scattering of thinkers amid an army of intellectually unskilled, undisciplined, and uncreative followers, then a renaissance and re-emergence of the idea of critical thinking as integral to knowledge and understanding is necessary. Such a reawakening and recognition began first in the USA in the later 30's and then surfaced in various forms in the 50's, 60's, and 70's, reaching its most public expression in the 80's and 90's. Nevertheless, despite the scholarship surrounding the idea, despite the scattered efforts to embody it in educational practice, the educational and social acceptance of the idea is still in its infancy, still largely misunderstood, still existing more in stereotype than in substance, more in image than in reality. The members of the Council (some 8000 plus educators) are committed to high standards of excellence in critical thinking instruction across the curriculum at all levels of education. They are, therefore, concerned with the proliferation of poorly conceived "thinking skills" programs with their simplistic — often slick — approaches to both thinking and instruction. If the current emphasis on critical thinking is genuinely to take root, if it is to avoid the traditional fate of passing educational fad and "buzz word," it is essential that the deep obstacles to its embodiment in quality education be recognized for what they are, reasonable strategies to combat them formulated by leading scholars in the field, and successful communication of both obstacles and strategies to the educational and broader community achieved. To this end, sound standards of the field of critical thinking research must be made accessible by clear articulation and the means set up for the large-scale dissemination of that articulation. The nature and challenge of critical thinking as an educational ideal must not be allowed to sink into the murky background of educational reform and restructuring efforts, while superficial ideas take its place. Critical thinking must assume its proper place at the hub of educational reform and restructuring. Critical thinking — and intellectual and social development generally — are not well-served when educational discussion is inundated with superficial conceptions of critical thinking and slick merchandizing of "thinking skills" programs while substantial — and necessarily more challenging conceptions and programs — are thrust aside, obscured, or ignored.

Elements of Thought

If teachers want their students to think well, they must help students understand at least the rudiments of thought, the most basic structures out of which all thinking is made. In other words, students must learn how to take thinking apart. All thinking is defined by the eight elements that make it up. Eight basic structures are present in all thinking. Whenever we think, we think for a purpose within a point of view based on assumptions leading to implications and consequences. We use concepts, ideas, and theories to interpret data, facts, and experiences in order to answer questions, solve problems, and resolve issues. Thinking, then, generates purposes, raises questions, uses information, utilizes concepts, makes inferences, makes assumptions, generates implications, and embodies a point of view. Students should understand that each of these structures has implications for the others. If they change their purpose or agenda, they change their questions and problems. If they change their questions and problems, they are forced to seek new information and data, and so on. Students should regularly use the following checklist for reasoning to improve their thinking in any discipline or subject area:

- State your purpose clearly.

- Distinguish your purpose from related purposes.

- Check periodically to be sure you are still on target.

- Choose significant and realistic purposes.

- State the question at issue clearly and precisely.

- Express the question in several ways to clarify its meaning and scope.

- Break the question into sub-questions.

- Distinguish questions that have definitive answers from those that are a matter of opinion and from those that require consideration of multiple viewpoints.

- Clearly identify your assumptions and determine whether they are justifiable.

- Consider how your assumptions are shaping your point of view.

- Identify your point of view.

- Seek other points of view and identify their strengths and weaknesses.

- Strive to be fair-minded in evaluating all points of view.

- Restrict your claims to those supported by the data you have.

- Search for information that opposes your position, as well as information that supports it.

- Make sure that all information used is clear, accurate, and relevant to the question at issue.

- Make sure you have gathered sufficient information.

- Identify key concepts and explain them clearly.

- Consider alternative concepts or alternative definitions of concepts.

- Make sure you are using concepts with care and precision.

- Infer only what the evidence implies.

- Check inferences for their consistency with each other.

- Identify assumptions that lead you to your inferences.

- Trace the implications and consequences that follow from your reasoning.

- Search for negative as well as positive implications.

- Consider all possible consequences.

Universal Intellectual Standards

Universal intellectual standards are standards which must be applied to thinking whenever one is interested in checking the quality of reasoning about a problem, issue, or situation. To think critically entails having command of these standards. To help students learn them, teachers should pose questions which probe student thinking, questions which hold students accountable for their thinking, questions which, through consistent use by the teacher in the classroom, become internalized by students as questions they need to ask themselves.

The ultimate goal, then, is for these questions to become infused in the thinking of students, forming part of their inner voice, which then guides them to better and better reasoning. While there are a number of universal standards, the following are the most significant:

Clarity is the gateway standard. If a statement is unclear, we cannot determine whether it is accurate or relevant. In fact, we cannot tell anything about it because we don’t yet know what it is saying. For example, the question "What can be done about the education system in America?" is unclear. In order to address the question adequately, we would need to have a clearer understanding of what the person asking the question is considering the "problem" to be. A clearer question might be "What can educators do to ensure that students learn the skills and abilities which help them function successfully on the job and in their daily decision-making?"

A statement can be clear but not accurate, as in "Most dogs are over 300 pounds in weight."

A statement can be both clear and accurate, but not precise, as in "Jack is overweight." (We don’t know how overweight Jack is, one pound or 500 pounds.)

A statement can be clear, accurate, and precise, but not relevant to the question at issue. For example, students often think that the amount of effort they put into a course should be used in raising their grade in a course. Often, however, the "effort" does not measure the quality of student learning, and when this is so , effort is irrelevant to their appropriate grade.

A statement can be clear, accurate, precise, and relevant, but superficial (that is, lacks depth). For example, the statement "Just say No," which is often used to discourage children and teens from using drugs, is clear, accurate, precise, and relevant. Nevertheless, it lacks depth because it treats an extremely complex issue, the pervasive problem of drug use among young people, superficially. It fails to deal with the complexities of the issue.

A line of reasoning may be clear accurate, precise, relevant, and deep, but lack breadth (as in an argument from either the conservative or liberal standpoint which gets deeply into an issue, but only recognizes the insights of one side of the question.)

When we think, we bring a variety of thoughts together into some order. When the combination of thoughts are mutually supporting and make sense in combination, the thinking is "logical." When the combination is not mutually supporting, is contradictory in some sense, or does not "make sense," the combination is not logical.

Valuable Intellectual Traits

Intellectual traits, or virtues, are interrelated intellectual habits that enable students to discipline and improve mental functioning. Teachers need to keep in mind that critical thinking can be used to serve two incompatible ends: self-centeredness or fair-mindedness. As students learn the basic intellectual skills that critical thinking entails, they can begin to use those skills in either a selfish or in a fair-minded way. For example, when students are taught how to recognize mistakes in reasoning (commonly called fallacies), most students readily see those mistakes in the reasoning of others but do not see them so readily in their own reasoning. Often they enjoy pointing out others' errors and develop some proficiency in making their opponents' thinking look bad, but they don't generally use their understanding of fallacies to analyze and assess their own reasoning. It is thus possible for students to develop as thinkers and yet not to develop as fair-minded thinkers. The best thinkers strive to be fair-minded, even when it means they have to give something up. They recognize that the mind is not naturally fair-minded, but selfish. And they understand that to be fair-minded, they must also develop particular traits of mind, traits such as intellectual humility, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, intellectual integrity, intellectual perseverance, faith in reason, and fair-mindedness. Teachers should model and discuss the following intellectual traits as they help their students become fair-minded, ethical thinkers.

- Intellectual Humility : Having a consciousness of the limits of one's knowledge, including a sensitivity to circumstances in which one's native egocentrism is likely to function self-deceptively; sensitivity to bias, prejudice and limitations of one's viewpoint. Intellectual humility depends on recognizing that one should not claim more than one actually knows. It does not imply spinelessness or submissiveness. It implies the lack of intellectual pretentiousness, boastfulness, or conceit, combined with insight into the logical foundations, or lack of such foundations, of one's beliefs.

- Intellectual Courage : Having a consciousness of the need to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs or viewpoints toward which we have strong negative emotions and to which we have not given a serious hearing. This courage is connected with the recognition that ideas considered dangerous or absurd are sometimes rationally justified (in whole or in part) and that conclusions and beliefs inculcated in us are sometimes false or misleading. To determine for ourselves which is which, we must not passively and uncritically "accept" what we have "learned." Intellectual courage comes into play here, because inevitably we will come to see some truth in some ideas considered dangerous and absurd, and distortion or falsity in some ideas strongly held in our social group. We need courage to be true to our own thinking in such circumstances. The penalties for non-conformity can be severe.

- Intellectual Empathy : Having a consciousness of the need to imaginatively put oneself in the place of others in order to genuinely understand them, which requires the consciousness of our egocentric tendency to identify truth with our immediate perceptions of long-standing thought or belief. This trait correlates with the ability to reconstruct accurately the viewpoints and reasoning of others and to reason from premises, assumptions, and ideas other than our own. This trait also correlates with the willingness to remember occasions when we were wrong in the past despite an intense conviction that we were right, and with the ability to imagine our being similarly deceived in a case-at-hand.

- Intellectual Integrity : Recognition of the need to be true to one's own thinking; to be consistent in the intellectual standards one applies; to hold one's self to the same rigorous standards of evidence and proof to which one holds one's antagonists; to practice what one advocates for others; and to honestly admit discrepancies and inconsistencies in one’s own thought and action.

- Intellectual Perseverance : Having a consciousness of the need to use intellectual insights and truths in spite of difficulties, obstacles, and frustrations; firm adherence to rational principles despite the irrational opposition of others; a sense of the need to struggle with confusion and unsettled questions over an extended period of time to achieve deeper understanding or insight.

Faith In Reason: Confidence that, in the long run, one's own higher interests and those of humankind at large will be best served by giving the freest play to reason, by encouraging people to come to their own conclusions by developing their own rational faculties; faith that, with proper encouragement and cultivation, people can learn to think for themselves, to form rational viewpoints, draw reasonable conclusions, think coherently and logically, persuade each other by reason and become reasonable persons, despite the deep-seated obstacles in the native character of the human mind and in society as we know it.

Fair-mindedness : Having a consciousness of the need to treat all viewpoints alike, without reference to one's own feelings or vested interests, or the feelings or vested interests of one's friends, community or nation; implies adherence to intellectual standards without reference to one's own advantage or the advantage of one's group.

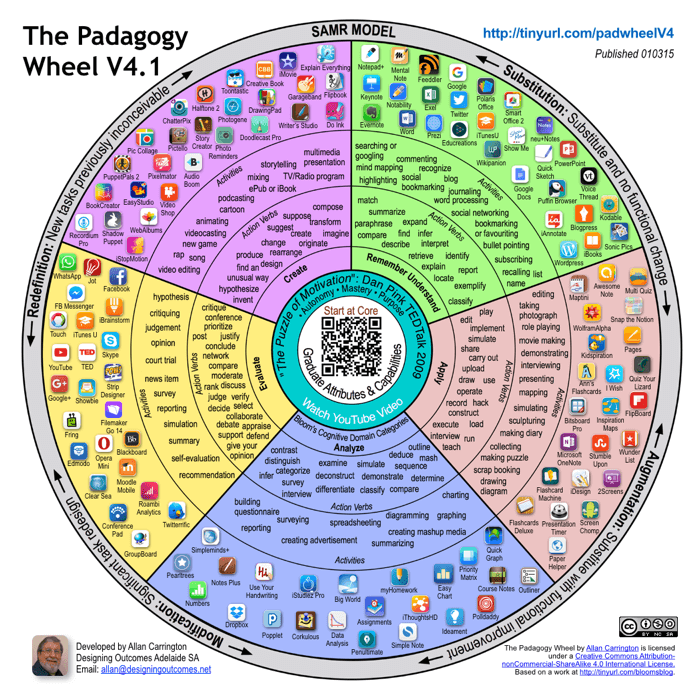

The Padagogy Wheel: It’s Not About The Apps, It’s About The Pedagogy

The Padagogy Wheel brings together in one chart several different domains of thinking with education apps for learning.

It’s Not About The Apps, It’s About The Pedagogy

contributed by Allan Carrington

The Padagogy Wheel is designed to help educators think – systematically, coherently, and with a view to long term, big-picture outcomes – about how they use mobile apps in their teaching. The Padagogy Wheel is all about mindsets; it’s a way of thinking about digital-age education that meshes together concerns about mobile app features, learning transformation, motivation, cognitive development and long-term learning objectives.

The Padagogy Wheel, though, is not rocket science. It is an everyday device that can be readily used by everyday teachers; it can be applied to everything from curriculum planning and development, to writing learning objectives and designing centered activities. The idea is for the users to respond to the challenges that the Wheel presents for their teaching practices, and to ask themselves the tough questions about their choices and methods.

The underlying principle of the Padagogy Wheel is that it is the pedagogy that should determine our educational use of apps. It’s all very well to come across an exciting new app and to think to yourself, ‘That’s really cool, now how can I use it in the classroom?,’ but what you need to do at the same time is to think about how that app might contribute to your set of educational aims for the program you are teaching. It was in fact this very concern, my desire to help teachers make good decisions as to how to make the pedagogy drive the technology, and not the other way around, that led to the birth of the Padagogy Wheel.

So how does it work?

The Padagogy Wheel brings together in the one chart several different domains of pedagogical thinking. It situates mobile apps within this integrated framework, associating them with the educational purpose they are most likely to serve. It then enables teachers to identify the pedagogical place and purpose of their various app-based learning and teaching activities in the context of their overall objectives for the course, and with reference to the wider developmental needs of their students.

THE FIVE GRIDS

1. Graduate Attributes And Capabilities

Graduate Attributes are at the core of learning design. Graduate Attributes address the long-term, enduring aims of our educational activity. They involve thinking about the type of people that emerge from our educational programs – their ethics, responsibility, and citizenship, for example – and their employability in our current and future society. Teachers must constantly revisit how their programs are contributing to the development of these attributes.

They need to do the hard yards of articulating what they expect a program graduate to ‘look like’–i.e. what is it that a graduate is and does that we regard as successful and meets the expectations of their communities as change agents and leaders. How else can teachers help students know what transformation ‘looks like’?

Many universities around the world are constantly working on their graduate attributes and are mapping their programs to them. The blog post “ If you exercise these capabilities.. You will be employed!” where I interviewed Prof. Geoff Scott, is really eye opening for college educators as it highlights the attributes and capabilities the CEOs in the marketplace want in graduates, the things they look for in hiring. If educational leaders don’t have a clear picture of the qualities and capabilities of an excellent graduate of their program, then how can teachers help students strive for excellence and to be leaders in their worlds?

Every teacher needs to examine their courses and pedagogy and ask, “How does everything I do support these attributes? Is there any way I can build content and activities that help students become ‘excellent’?”

2. Motivation

Motivation is vital to achieving the most effective learning outcomes. It is valuable for teachers to regularly ask themselves “Why am I doing this again?” That is not a joke. I am referring to the choices of learning outcomes, development of activities and design of content e.g. writing text and even making videos. So the wheel introduces a 21st century model of motivation that science has developed and is so well presented by Dan Pink in the TEDtalk “ The Puzzle of Motivation “.

Thinking through the grid of Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose (AMP) and filtering everything you do from idea-creation to assessment will, I believe, significantly help your teaching be transformational.

3. Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy is really a way of helping teachers design learning objectives that require higher-order thinking. You start with ‘remembering and understanding’, which is the easiest category to serve with objectives but produces the least effective outcomes in achieving transformation. When supporting teachers, I recommend they try to get at least one learning objective from each category and always push towards the domain category of Creating, where higher order thinking takes place. This is the ‘By the time you finish this workshop/seminar/lesson you should be able to. . .’ type of thinking. Only after you have developed your learning outcomes are you ready for technology enhancement.

4. Technology Enhancement

Technology Enhancement serves your pedagogy. When you choose any app or technology remember to apply the app selection criteria. The model only suggests apps that can support the learning objectives and activities at the time of publishing. The Padagogy Wheel constantly needs updating with apps as they are released. Teachers also should think about customization all the time – is there a better app or tool for the job of enhancing my defined pedagogy?

5. The SAMR Model

The history of the Padagogy Wheel

In 2012 on a teaching trip to the UK, I got the idea of putting apps around the outside of Bloom’s Taxonomy Wheel and organizing them according to his cognitive domain categories. The taxonomy was based on Kathwohl and Anderson’s (2001) adaption of Bloom (1956) and it was their work that combined Remembering and Understanding.