- Biomarker-Driven Lung Cancer

- HER2 Breast Cancer

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Renal Cell Carcinoma

- CONFERENCES

- PUBLICATIONS

- CASE-BASED ROUNDTABLE

Case 1: 72-Year-Old Woman With Small Cell Lung Cancer

EP: 1 . Case 1: 72-Year-Old Woman With Small Cell Lung Cancer

Ep: 2 . case 1: extensive-stage small cell lung cancer background, ep: 3 . case 1: impower133 trial in small cell lung cancer, ep: 4 . case 1: caspian trial in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, ep: 5 . case 1: biomarkers in small cell lung cancer, ep: 6 . case 1: small cell lung cancer in the era of immunotherapy.

EP: 7 . Case 2: 67-Year-Old Woman With EGFR+ Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer

Ep: 8 . case 2: biomarker testing for non–small cell lung cancer, ep: 9 . case 2: egfr-positive non–small cell lung cancer, ep: 10 . case 2: flaura study for egfr+ metastatic nsclc, ep: 11 . case 2: egfr+ nsclc combination therapies.

EP: 12 . Case 2: Treatment After Progression of EGFR+ NSCLC

EP: 13 . Case 3: 63-Year-Old Man With Unresectable Stage IIIA NSCLC

Ep: 14 . case 3: molecular testing in stage iii nsclc, ep: 15 . case 3: chemoradiation for stage iii nsclc, ep: 16 . case 3: pacific trial in unresectable stage iii nsclc, ep: 17 . case 3: standard of care in unresectable stage iii nsclc, ep: 18 . case 3: management of immune-related toxicities in stage iii nsclc.

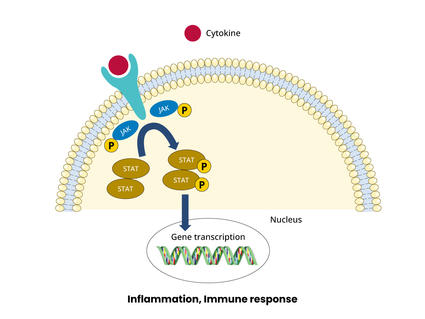

Mark Socinski, MD: Thank you for joining us for this Targeted Oncology ™ Virtual Tumor Board ® focused on advanced lung cancer. In today’s presentations my colleagues and I will review three clinical cases. We will discuss an individualized approach to treatment for each patient, and we’ll review key clinical trial data that impact our decisions. I’m Dr. Mark Socinski from the AdventHealth cancer institute in Orlando, Florida. Today I’m joined by Dr Ed Kim, a medical oncologist from the Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, North Carolina; Dr Brendon Stiles, who is a thoracic surgeon from the Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York ; and Dr Tim Kruser, radiation oncologist from Northwestern Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Thank you all for joining me today. We’re going to move to the first case, which is a case of small cell lung cancer. I’m going to ask Dr Kim to do the presentation.

Edward Kim, MD: Thanks, Mark. It’s my pleasure to walk us through the first case, which is small cell lung cancer. This is a case with a 72-year-old woman who presents with shortness of breath, a productive cough, chest pain, some fatigue, anorexia, a recent 18-pound weight loss, and a history of hypertension. She is a schoolteacher and has a 45-pack-a-year smoking history; she is currently a smoker. She is married, has 2 kids, and has a grandchild on the way. On physical exam she had some dullness to percussion with some decreased-breath sounds, and the chest x-ray shows a left hilar mass and a 5.4-cm left upper-lobe mass. CT scan reveals a hilar mass with a bilateral mediastinal extension. Negative for distant metastatic disease. PET scan shows activity in the left upper-lobe mass with supraclavicular nodal areas and liver lesions, and there are no metastases in the brain on MRI. The interventional radiographic test biopsy for liver reveals small cell, and her PS is 1. Right now we do have a patient who has extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Unfortunately, it’s what we found. It’s very common to see this with liver metastases.

Transcript edited for clarity.

FDA Approval Marks Amivantamab's Milestone in EGFR+ NSCLC

In this episode, Joshua K. Sabari, MD, discusses the FDA approval of amivantamab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer.

FDA Grants Zongertinib Breakthrough Therapy Designation in HER2-Mutant NSCLC

New data on zongertinib for HER2-positive non–small cell lung cancer will be presented at the IASLC 2024 World Conference on Lung Cancer, shedding light on its potential as a novel treatment option for this patient population.

Lisberg Discusses Dato-DXd's Role in Advanced Lung Cancer Care

In this episode of Targeted Talks, Aaron Lisberg, MD, discusses results from the phase 3 TROPION-Lung01 study of datopotamab in advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer.

Long-Term Immune Checkpoint Inhibition Shows Potential Extended Survival in NSCLC

Biagio Ricciuti, MD, discussed findings from a retrospective study exploring the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors for longer than 2 years in patients with non–small cell lung cancer.

Amivantamab/Lazertinib Shows Potential in Atypical EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancer

Byoung Chul Cho, MD, PhD, discussed findings from cohort C of the CHYRSALIS-2 study exploring amivantamab plus lazertinib in patients with non–small cell lung cancer with uncommon EGFR mutations.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 19 August 2022

Triple primary lung cancer: a case report

- Hye Sook Choi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8387-4907 1 &

- Ji-Youn Sung 2

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 22 , Article number: 318 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3077 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

The risk of developing lung cancer is increased in smokers, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, individuals exposed to environmental carcinogens, and those with a history of lung cancer. Automobile exhaust fumes containing carcinogens are a risk factor for lung cancer. However, we go through life unaware of the fact that automobile exhaust is the cause of cancer. Especially, in lung cancer patient, it is important to search out pre-existing risk factors and advice to avoid them, and monitor carefully for recurrence after treatment.

Case presentation

This is the first report of a case with triple lung cancers with different histologic types at different sites, observed in a 76-year-old parking attendant. The first adenocarcinoma and the second squamous cell carcinoma were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery because the patient did not want to undergo surgery. Although the patient stopped intermittent smoking after the diagnosis, he continued working as a parking attendant in the parking lot. After 29 months from the first treatment, the patient developed a third new small cell lung cancer; he was being treated with chemoradiation.

Conclusions

New mass after treatment of lung cancer might be a multiple primary lung cancer rather than metastasis. Thus, precision evaluation is important. This paper highlights the risk factors for lung cancer that are easily overlooked but should not be dismissed, and the necessity of discussion with patients for the surveillance after lung cancer treatment. We should look over carefully the environmental carcinogens already exposed, and counsel to avoid pre-existing lung cancer risk factors at work or residence in patients with lung cancer.

Peer Review reports

The risk factors for lung cancer include smoking and inhaling exhaust fumes. Primary lung cancer (PLC) increases the risk of secondary lung cancers by four to six times [ 1 , 2 ]. With increasing exposure to environmental risk factors such as automobile exhaust fumes and advances in computed tomographic (CT) screening and treatment modality of lung cancer, the incidence of multiple primary lung cancers (MPLC) is increasing [ 2 ]. Synchronous MPLC is defined as a new cancer if it occurs with the same histology within 2 years after the PLC therapy, or with a different histology at the same time [ 3 ]; Metachronous MPLC is defined as a new cancer with the same histology if it occurs after a tumor-free period of 2 years; otherwise, it is considered to have a different histology [ 3 ]. Incidence of MPLC is higher in women, people with history of malignant disease, and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), compared to solitary PLC. Men, smokers, patients with COPD, and those with non-adenocarcinomas have higher incidence of metachronous MPLC. Female sex and not smoking are independent risk factors for synchronous MPLC [ 4 ]. It is important to manage the risk factors for MPLC in patients diagnosed with lung cancer. However, patients counselling to avoid the already existing risk factors for lung cancers is not generally conducted in depth. For the first time, we report a case of triple lung cancers with metachronous MPLC in a parking attendant.

A 76-year-old man was referred for a lung mass in December 2018. He was a smoker (30 pack years with intermittent stops) and parking attendant for 30 years. There was no history of lung cancer in the immediate family of the patient. The patient was administered a dual bronchodilator for COPD.

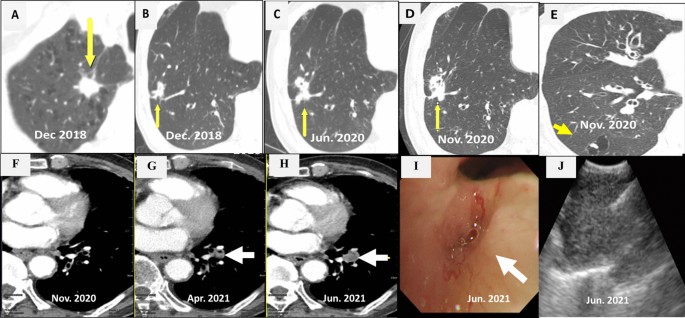

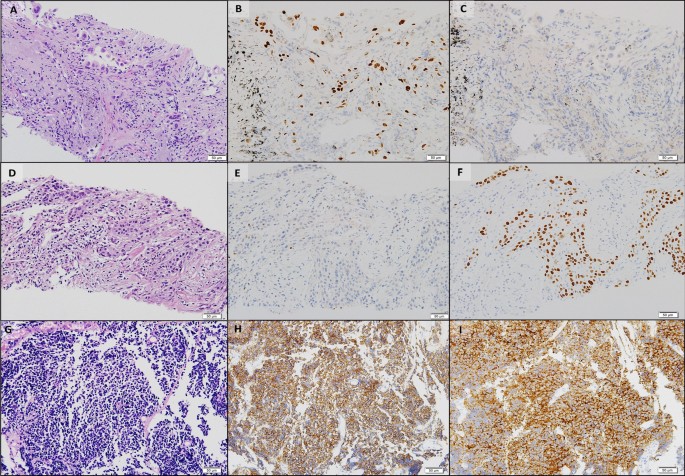

CT scan showed a 1.4 cm × 1.3 cm mass in the right upper lobe (RUL) (Fig. 1 a) and a right lower lobe (RLL) mass-like consolidation (Fig. 1 b). Histopathologic examinations of CT-guided-percutaneous needle biopsy (PCNB) of the RUL mass revealed adenocarcinoma (ADC) (Fig. 2 a–c) with clinical staging cT1bN0M0 on ultrasonic-guided transbronchial needle biopsy (EBUS-TBNB) and fluorodeoxyglucose F18-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan. RLL mass showed no metabolism on the FDG-PET scan. The FEV 1 was 56% of the predicted value. We planned a lobectomy for the RUL cancer and a follow-up for the RLL mass. However, the patient refused to undergo surgery and was treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) on the RUL mass in January 2019. The RLL mass-like consolidation did not show any changes on the follow-up chest CT or FDG-PET scan in November 2019.

Chest CT scans. a A mass on the RUL of the first adenocarcinoma (arrow). b A mass on the RLL at the same time of the first cancer diagnosis (arrow). c Increased RLL mass six months later (arrow). d Further increased RLL mass after five months (arrow). e New nodule on the peripheral RLL (arrow). f–h Development and increase of the lymph node (arrow). i Bronchoscopic finding showing LLL anterobasal segment obstruction (arrow). j Lymph node enlargement on the EBUS. CT, computed tomography; RUL, right upper lobe; RLL, right lower lobe; LLL, left lower lobe; EBUS, endobronchial ultrasound

Histopathologic comparisons of the triple lung cancers. a-c The first tumor of adenocarcinoma at the right upper lobe. a Pleomorphic neoplastic cells with an acinar pattern (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). b Immunoreactivity for TTF-1(×200). c Negative for P40(×200). d-f The second tumor of squamous cell carcinoma at the right lower lobe. d Polygonal cells with a solid pattern and no keratinization (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). e No immunoreactivity for TTF-1(×200). f Strong staining of P40 at tumor cells(×200). g-i The third tumor of small cell carcinoma at the left lower lobe. g Small cells with scant cytoplasm and lack of nucleoli with a high mitotic activity (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). h Positive neuroendocrine markers of CD56(×200). i Positive neuroendocrine marker of synaptophysin(×200). Equipment used to obtain images: Olympus BX53 microscope/Olympus objective lens WHN10X/22 UIS2, Olympus DP72 cameras and acquisition software: Olympus CellSens Standard 1.6 software. TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1

In June 2020, the RLL mass-like consolidation was found to have increased on a chest CT scan (Fig. 1 c). PCNB of the RLL mass was performed, and histologic examination revealed anthracofibrosis. Five months later, the RLL mass increased further (Fig. 1 d), and a new nodule appeared at the periphery of the RLL (Fig. 1 e). PCNB was performed again on the same RLL mass (Fig. 1 d), and histological examination demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (Fig. 2 d–f). There was no metastasis except for hypermetabolism of the new nodule in the RLL periphery (Fig. 1 e) on the FDG-PET scans. We could not perform a biopsy for the new peripheral nodule (Fig. 1 e) due to cystic changes. We concluded the clinical staging of the RLL SCC as cT3N0M0 on the EBUS-TBNB and PET scan. SRSs were performed separately for the RLL SCC and the new RLL peripheral nodule, respectively in February 2021.

We performed chest CT scan for surveillance of lung cancer. Five months later after 2nd SCC diagnosis, a new nodule emerged at the left lower lobe (LLL) (Fig. 1 f, g). Two months after that, the nodule increased further (Fig. 1 h). Bronchoscopy showed new total obstruction of the anterobasal segmental bronchus of the LLL (Fig. 1 i). Histologic examinations of bronchial biopsy and EBUS-TBNB (Fig. 1 j) for LLL lesions demonstrated small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) (Fig. 2 g–i). Clinical staging was limited stage. The patient was treated with chemotherapy (etoposide/carboplatin) and concurrent thoracic radiation.

Discussion and conclusions

Smoking is a notorious risk factor for lung cancer. The parking attendant was exposed to exhaust fumes, including carcinogens from the fuel. He was using a bronchodilator for COPD. Smoking and COPD are independent risk factors for MPLC [ 4 ]. PLC increased the risk of MPLC despite stage IA lung cancer [ 5 , 6 ]. We suggest that his history of exposure to exhaust fumes in addition to smoking, COPD, and PLC contributed to the metachronous MPLC.

At the time of the first ADC diagnosis on the RUL, we discuss the possibility that the RLL mass was lung cancer, and decided to follow according to the PET-CT scan results with the multidisciplinary approach. Unfortunately, 18 months later, PCNB and histologic findings for the RLL mass showed no cancers. Five months after that (23 months after the first ADC treatment), repeated PCNB on the RLL mass demonstrated SCC. The possibility that an additional abnormality is cancer must be addressed when PLC is diagnosed.

The third SCLC of LLL developed newly 29 months after the first ADC treatment. It was detected after 5 months after the diagnosis of second cancer. Timely CT scan for surveillance is essential for earlier diagnosis of metachronous MPLC in the patients with PLC, which could be improve the outcomes of MPLC. We considered that the first ADC and the second SCC were synchronous MPLC; thus, the third SCLC might be metachronous MPCL. The three different types of MPLC were not a transformation of the PLC after SRSs, but originally developed from three different histologies. Recently, genetic/molecular profiles have begun to be used for differentiation and diagnosis of MPLC [ 7 ]. and further investigation is needed.

The primary tumor control rate of SRS is 97.6% in medically inoperable early-stage non-SCLC [ 8 ]. Recently, the risk of metachronous MPLC was found to be lower with radiotherapy than non-radiotherapy [ 6 , 8 ] even though in stage IA lung cancer [ 5 ]. The incidence of metachronous MPLC was 0.5% at 1 year and 2.28% at 5 years among solitary PLC survivors with radiotherapy, which was lower compared to the non-radiotherapy group [ 6 ]. Based on these findings, it is assumed that the SRSs might not induce metachronous MPLC in our patient.

The question was what could have been responsible for the patient’s triple lung cancers. Unknown susceptible genetic factors, smoking, and exhaust fumes might have contributed to the development of triple lung cancers. Previously reported risk factors [ 4 ] such as male sex, smoking, COPD, and nonadenocarcinoma also increased the risk of metachronous MPLC in this patient. He stopped smoking after the first diagnosis of lung cancer, but continued as a parking attendant for 12 h a day. It is well known that harmful effects of smoking persist for years even after smoking cessation. Thus, the main cause of lung cancer in this patient is likely to be smoking. Physicians always counsel their lung cancer patients that smoking is one of the main causes of lung cancer and advise to quit smoking immediately. However, the emphasis on counselling avoidance of other environmental carcinogens that may have a synergistic effect with smoking is often neglected. This patient was exposed to exhaust gas at work for 30 years which is a known occupational carcinogen, and exposure continued even after quitting smoking and diagnosing lung cancer. He had no family history of lung cancer. Unfortunately, his wife was diagnosed with stage IV lung adenocarcinoma lung cancer at August 2021, the time of 3 rd SCLC diagnosis of him. He and his wife had worked together in parking lot for several years. We suggest that exhaust fumes might be an additional main risk factor for metachronous MPLC that is easily overlooked in this patient.

Despite stage I lung cancer, careful surveillance for metachronous MPLC is needed, especially in patients with a history of smoking, COPD, PLC, and exposure to environmental carcinogens such as exhaust fumes. Occupation and environment surveys with attentive advice for risk factors of lung cancer are very important, and it is valuable to evaluate concurrent abnormal images in patients with lung cancer. Appropriate CT scan surveillance after PLC therapy can help identify curable MPLC, which might lead to improved overall survival.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Adenocarcinoma

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Computed tomography

Ultrasonic-guided transbronchial needle biopsy

F18-positron emission tomography

Left lower lobe

Primary lung cancer

Multiple primary lung cancers

Percutaneous needle biopsy

Right lower lobe

Right upper lobe

Squamous cell carcinoma

Small cell lung carcinoma

Stereotactic radiosurgery

Johnson BE. Second lung cancers in patients after treatment for an initial lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(18):1335–45.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Surapaneni R, Singh P, Rajagopalan K, Hageboutros A. Stage I lung cancer survivorship: risk of second malignancies and need for individualized care plan. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(8):1252–6.

Article Google Scholar

Martini N, Melamed MR. Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70(4):606–12.

Shintani Y, Okami J, Ito H, Ohtsuka T, Toyooka S, Mori T, Watanabe S-i, Asamura H, Chida M, Date H, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with stage I multiple primary lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(5):1924–35.

Khanal A, Lashari BH, Kruthiventi S, Arjyal L, Bista A, Rimal P, Uprety D. The risk of second primary malignancy in patients with stage Ia non-small cell lung cancer: a US population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(2):239–43.

Hu ZG, Tian YF, Li WX, Zeng FJ. Radiotherapy was associated with the lower incidence of metachronous second primary lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19283–19283.

Asamura H. Multiple primary cancers or multiple metastases, that is the question. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(7):930–1.

Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, Michalski J, Straube W, Bradley J, Fakiris A, Bezjak A, Videtic G, Johnstone D, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

No funding sources were used.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee Unversity Medical Center, 23 Kyunghee dae-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, 02447, Republic of Korea

Hye Sook Choi

Department of Pathology, Kyung Hee University Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Ji-Youn Sung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HSC drafted the manuscript, reviewed the literature, and collected the data. JYS collected the data and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to obtaining and interpreting the clinical information. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hye Sook Choi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Kyung Hee University Medical Center (approval number: KHUH 2021–09-069–002) and written informed consent was given by the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Choi, H.S., Sung, JY. Triple primary lung cancer: a case report. BMC Pulm Med 22 , 318 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-02111-x

Download citation

Received : 07 April 2022

Accepted : 10 August 2022

Published : 19 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-02111-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Multiple primary lung cancer (MLPC)

- Synchronous MLPC

- Metachronous MLPC

- Parking attendant

BMC Pulmonary Medicine

ISSN: 1471-2466

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

A case report of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with long-term survival for over 11 years

Editor(s): NA.,

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital, 5-11-13, Sugano, Ichikawa, Chiba, Japan.

∗Correspondence: Tatsu Matsuzaki, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital, 5-11-13, Sugano, Ichikawa, Chiba 272-8513, Japan (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Abbreviations: CBDCA = carboplatin, CDDP = cisplatin, CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen, DTX = docetaxel, ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR-TKI = epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer, OS = overall survival, PD = progressive disease, PEM = pemetrexed, PFS = progression-free survival, RC = re-challenge chemotherapy, RR = response rate, UICC = Union of International Cancer Control.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The Ethics Committee of our hospital approved the study and provided permission to publish the results.

The patient provided written informed consent and has provided consent for publication of the case.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Rationale:

This is the first known report in the English literature to describe a case of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer that has been controlled for >11 years.

Patient concerns:

A 71-year-old man visited our hospital because of dry cough.

Diagnosis:

Chest computed tomography revealed a tumor on the left lower lobe with pleural effusion, and thoracic puncture cytology indicated lung adenocarcinoma.

Interventions:

Four cycles of carboplatin and docetaxel chemotherapy reduced the size of the tumor; however, it increased in size after 8 months, and re-challenge chemotherapy (RC) with the same drugs was performed. Repeated RC controlled disease activity for 6 years. After the patient failed to respond to RC, erlotinib was administered for 3 years while repeating a treatment holiday to reduce side effects. The disease progressed, and epidermal growth factor receptor ( EGFR ) gene mutation analysis of cells from the pleural effusion detected the T790 M mutation. Therefore, osimertinib was administered, which has been effective for >1 year.

Outcomes:

The patient has survived for >11 years since the diagnosis of lung cancer.

Lessons:

Long-term survival may be implemented by actively repeating cytotoxic chemotherapy and EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor administration.

1 Introduction

The prognosis of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is poor, and their 1-year survival rate after cytotoxic chemotherapy is only 29%. [1] However, the development of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) dramatically improves the prognosis of certain patients. Patients with EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC receiving EGFR-TKIs have a median overall survival (OS) more than twice as long as those not receiving EGFR-TKIs (24.3 vs 10.8 months). [2] The 5-year survival rate of patients with EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs is 14.6%. [3] However, metastatic NSCLC patients with long-term survival (>10 years) are still rare.

We treated an advanced NSCLC patient with malignant pleural effusion who survived for >11 years and for whom disease progression was controlled using drugs alone without surgery or radiation therapy.

2 Case presentation

A 71-year-old Japanese man experienced dry cough for 2 weeks and visited the Department of Respiratory Medicine at our hospital in August 2007. Enhanced chest-abdomen computed tomography revealed a tumor with a 3-cm diameter in the left lower lobe and left pleural effusion ( Fig. 1 ). A 5-mm nodule, considered to be lung metastasis, was detected in the left upper lobe. Cytological analysis of the left pleural effusion by thoracic puncture led to the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Gadolinium-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging and bone scintigraphy did not reveal any other metastases. The tumor was classified as clinical T4N0M1, stage IV according to the TNM classification of the Union of International Cancer Control (UICC), 6th edition. According to the UICC 8th edition, it was classified as clinical T4N0M1a, stage IV A. The patient had a history of hypertension and was a past smoker (60 pack-years) and a company employee. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) at the time of admission was 1. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was 97.4 ng/mL (normal, 0–5 ng/ml).

Beginning in August 2007, the patient received carboplatin (CBDCA) and docetaxel (DTX). After 4 cycles, the tumor was reduced to 1 cm in diameter. The 5-mm nodule and pleural effusion had also decreased. According to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1, partial response was achieved, but he experienced progressive disease (PD) after 8 months. Six cycles of re-challenge chemotherapy (RC) using the same regimen were started in August 2008 and were effective. Thereafter, at each recurrence of PD, 4 to 6 cycles of RC were administered, and by 2013, 38 cycles had been completed over 6 years of treatment ( Fig. 2 A). However, we could no longer control disease activity using the same chemotherapy regimen. Moreover, primary tumor size evaluation became difficult owing to massive pleural effusion; although not standard, we estimated the effect of treatment using the increase and decrease of CEA as an index. CEA increased from a minimum of 4.6 ng/ml to 33.3 ng/ml in October 2013 during repeated cytotoxic chemotherapy. Although his EGFR mutation status was unknown, we initiated erlotinib administration and the CEA level decreased. After 8 weeks, the patient developed grade 3 acneiform rash, assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0, and erlotinib administration was discontinued for 6 weeks. Cycles of medication and treatment holiday were repeated, and the patient was carefully observed for skin rash. Dose reduction was attempted once, but it was not effective, because we noted an elevated CEA level and intolerable skin rash. For 3 years, 4-week erlotinib administration was repeated with 4–6-week treatment holiday intervals ( Fig. 2 B). CEA increased from a minimum of 3.1 ng/ml to 30.4 ng/ml in January 2017 during treatment with erlotinib. We performed EGFR mutation analysis using adenocarcinoma cells from the pleural effusion and detected exon 19 deletion and exon 20 T790 M mutation; therefore, osimertinib was substituted for erlotinib.

We continued monthly CEA measurements after beginning osimertinib administration and noted that the level continued to decrease. In August 2018, the CEA level was 12.1 ng/ml and the ECOG-PS was 1. As of the last follow-up, the patient has survived for >11 years since the diagnosis of lung cancer.

3 Discussion

The clinical data of 10 patients with advanced NSCLC who survived for >5 years were retrospectively reviewed, and a good PS, adenocarcinoma, and a history of EGFR-TKI administration were the factors contributing to long-term survival. [4] According to another retrospective study, [3] 20 of 137 patients with EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma survived for ≥5 years, and exon 19 deletion, absence of extrathoracic metastases, absence of brain metastasis, and current non-smoking status were reportedly good prognostic factors. Our case corroborated the good prognostic factors reported in these studies.

A case of metastatic NSCLC in which the patient survived for 10 years has already been reported; however, the patient underwent not only chemotherapy but also surgery and radiation therapy. [5] To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first report in the English literature to describe a metastatic NSCLC case controlled for >11 years. Moreover, our patient was only treated with chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs.

We considered that 4 treatment policies may be the key to success:

- 1. RC with CBDCA plus DTX;

- 2. repeated re-challenge erlotinib administration;

- 3. osimertinib administration after T790 M mutation in exon 20, which confers resistance to erlotinib; and

- 4. use of both cytotoxic drugs and EGFR-TKIs. We will particularly focus on the first and second policies because of the non-standard methods.

The response rate (RR) to RC of platinum doublets containing pemetrexed (PEM) or taxanes is reportedly 27.5%, with a progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.9 months and an OS of 8.7 months. This RR is high, but the PFS and OS are similar to those seen with administration of a single-agent as second-line treatment. [6] Advanced NSCLC patients for whom RC with 2-drug combination therapy is performed have a longer median survival than those administered only DTX as second-line treatment. [7] The current evidence that RC is superior to a single agent second-line treatment is not sufficient, but if the side effects are acceptable, RC may be a suitable option.

To safely perform RC using platinum-based 2-drug therapy, it may be necessary to include a treatment holiday period for a certain duration to facilitate physical fitness recovery. Time to progression of >3 months after ending first-line chemotherapy is a predictor of long-term survival (>2 years) in advanced NSCLC patients who receive cytotoxic chemotherapy. [8] Advanced NSCLC patients who survive for >2 years have a good response to first-line cytotoxic chemotherapy, and a prolonged treatment-free interval increases long-term survival. [9] In the present case, the treatment holiday after cytotoxic chemotherapy was approximately 6 months. A prolonged treatment-free interval appears to be important for restoring physical fitness; therefore, the patient could tolerate the next treatment.

A meta-analysis of randomized control studies compared cisplatin (CDDP) and CBDCA in advanced NSCLC patients. Although regimens containing CDDP did not prolong OS, subgroup analysis demonstrated that, when combined with third-generation anticancer drugs, CDDP prolonged OS more than CBDCA in patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma. [10] In the TAX 326 trial, CBDCA and DTX combination therapy helped achieve an OS equivalent to that associated with CDDP and vinorelbine combination therapy; in addition, the CBDCA and DTX combination was well tolerated and facilitated a high quality of life. [11] Here, 38 cycles of CBDCA and DTX combination therapy were administered. To perform platinum-based 2-drug RC, it may be advantageous to repeatedly administer CBDCA rather than CDDP to facilitate tolerability.

When erlotinib toxicity is intolerable, as in our patient who developed a severe skin rash, the dosage is generally reduced. In patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, dose reduction (25 mg/day) of erlotinib can reduce the toxicity while maintaining efficacy. [12] In contrast, a prospective phase II trial involving low-dose erlotinib in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC revealed that dose reduction (50 mg/day) is not recommended because of reduced efficacy. [13] Intermittent erlotinib administration on alternate days successfully maintained efficacy while reducing toxicity. [14] Here, disease control was possible by RC of platinum doublets for approximately 6 cycles after the 6-month treatment holiday. Therefore, we applied the RC strategy to EGFR-TKI administration. Continued erlotinib administration was discontinued if side effects became intolerable or health-threatening and resumed when side effects disappeared. Toxicity and efficacy were balanced by allowing an approximately 4–6-week treatment holiday after the 4-week erlotinib administration. To the best of our knowledge, we were the first to employ erlotinib in RC; this method was named repeated re-challenge administration of erlotinib and was considered to alleviate suffering due to toxicity. Although there is little evidence to determine whether dose reduction, intermittent administration, or repeated re-challenge administration is better, it is important to avoid complete cessation of therapy.

The exon 20 mutation in EGFR , leading to the T790 M mutation, is a resistance mechanism to traditional EGFR-TKIs. Osimertinib treatment is associated with a longer median PFS than chemotherapy using PEM plus either CBDCA or CDDP as second-line treatment in T790M-mutant patients who received EGFR-TKIs. [15] Our patient with the exon 19 deletion and T790 M mutation received osimertinib after erlotinib. Even if the tumor develops resistance to conventional EGFR-TKIs, it is important to recognize that drugs such as osimertinib are available and may improve long-term survival.

In EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC with exon 19 deletion and exon 21 (L858R) mutation, patients who receive sequential therapy with erlotinib and cytotoxic drugs experience a longer median OS than those who receive cytotoxic drugs or erlotinib alone. [16] It may be important to administer both EGFR-TKIs and cytotoxic drugs throughout the course of treatment.

Although more study is required, RC of CBDCA plus DTX and repeated re-challenge administration of erlotinib may be an empirical option for long-term survival. To understand the clinical and biological background of long-term survival cases, accumulation of future cases similar to ours is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage ( www.editage.jp ) for English language editing.

Author contributions

Supervision: Takeshi Terashima.

Writing – original draft: Tatsu Matsuzaki.

Writing – review & editing: Eri Iwami, Kotaro Sasahara, Aoi Kuroda, Takahiro Nakajima.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

- View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef |

- PubMed | CrossRef |

adenocarcinoma; EFGR-TKIs; EGFR gene mutation; long-term survival; non-small cell lung cancer; re-challenge chemotherapy; T790 M

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Global and regional prevalence and burden for premenstrual syndrome and..., severe re-expansion pulmonary edema after chest tube insertion for the..., is intraoperative corticosteroid a good choice for postoperative pain relief in ..., the incidence and prognosis of thymic squamous cell carcinoma: a surveillance,..., klebsiella pneumoniae</em> k2-st86: case report', 'yamamoto hiroyuki md phd; iijima, anna ms; kawamura, kumiko phd; matsuzawa, yasuo md, phd; suzuki, masahiro phd; arakawa, yoshichika md, phd', 'medicine', 'may 22, 2020', '99', '21' , 'p e20360');" onmouseout="javascript:tooltip_mouseout()" class="ejp-uc__article-title-link">fatal fulminant community-acquired pneumonia caused by hypervirulent klebsiella ....

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Thorax Education

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 64, Issue 7

- A case of small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy followed by photodynamic therapy

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Department of Internal Medicine; College of Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital and Cancer Research Institute, Jungku, Daejeon, South Korea

- Professor J O Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital and Cancer Research Institute, 640 Daesadong, Jungku, Daejeon 301-721, South Korea; jokim{at}cnu.ac.kr

Here, we present the case of a 51-year-old man with limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC) who received concurrent chemoradiotherapy and photodynamic therapy (PDT). The patient was diagnosed as having LS-SCLC with an endobronchial mass in the left main bronchus. Following concurrent chemoradiotherapy, a mass remaining in the left lingular division was treated with PDT. Clinical and histological data indicate that the patient has remained in complete response for 2 years without further treatment. This patient represents a rare case of complete response in LS-SCLC treated with PDT.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2008.112912

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Call: 1.631.629.4328 Mon-Fri 10 am - 2 pm EST

A 75-Year-Old Female Smoker with Advanced Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status 2 who Responded to Combination Immunochemotherapy with Atezolizumab, Etoposide, and Carboplatin

Unusual clinical course, Unusual setting of medical care, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

- 1 Second Department of Lung Diseases and Tuberculosis, Medical University of Białystok, Białystok, Poland

- A Study design/planning

- B Data collection/entry

- C Data analysis/statistics

- D Data interpretation

- E Preparation of manuscript

- F Literature analysis/search

- * Corresponding author: [email protected]

DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936536

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936536

- * Corresponding Author: Michał Dębczyński, e-mail: [email protected]

- Submitted: 01 March 2022

- Accepted: 08 June 2022

- In Press: 01 July 2022

- Published: 11 August 2022

This paper has been published under Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International ( CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ) allowing to download articles and share them with others as long as they credit the authors and the publisher, but without permission to change them in any way or use them commercially.

BACKGROUND: Atezolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor used as first-line treatment with carboplatin and etoposide chemotherapy for advanced small cell lung cancer. Immunochemotherapy treatment decisions can be affected by patients’ physical ability. Because of the exclusion of patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) ≥2 from clinical trials, treatment outcome evidence in this group is limited.

CASE REPORT: We present the case of a 75-year-old woman with an ECOG PS of 2 admitted with respiratory symptoms and diagnosed with advanced small-cell lung cancer. After managing exacerbation of COPD and decompensated heart failure, atezolizumab with carboplatin and etoposide was administered. After 2 cycles of immunochemotherapy, deterioration of health was observed, including anemia and thrombocytopenia. Because of the good response in imaging tests and restored balance of the patient condition, immunochemotherapy was continued. After 4 cycles of combined treatment, complete regression was achieved. No another adverse effects were observed. The patient was qualified for maintenance therapy with atezolizumab. In follow-up CT scan after 2 cycles of atezolizumab, progression was observed and patient was qualified for second-line treatment.

CONCLUSIONS: This report presents the case of an older patient with advanced small cell lung cancer and an ECOG status of 2 who responded to combined immunochemotherapy with atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin. Adverse effects observed during immunotherapy were not a reason for discontinuation of the therapy. The assessment of the effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with ECOG PS ³2 is difficult owing to the insufficient representation of this group in clinical trials.

Keywords: Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols, case reports, Immunotherapy, Physical Functional Performance, Aged, Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized, Carboplatin, Etoposide, Female, Group Processes, Humans, Lung Neoplasms, smokers

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for 15% to 20% of all lung cancer cases. Most of the patients diagnosed with this cancer are ≥65 years old, and the median age is 67 years [1,2]. SCLC is a cancer with an unfavorable prognosis [3]. The 3-year survival rate before the combined treatment era was 12% to 25% in the limited disease stage and did not exceed 2% in the disseminated disease stage [3]. SCLC is a highly tobacco-dependent cancer, as most of the patients diagnosed with SCLC are former or current cigarette smokers [4]. It is characterized by a high mitotic index and thus a rapid growth rate. Often, distant metastases are found at diagnosis. The limited form of the disease affects only 30% of patients [5]. The main method of treating patients with SCLC is chemotherapy based on etoposide and platinum derivatives. Recently, new therapeutic options have emerged in first-line treatment, with the addition of immunological drugs to standard chemotherapy. In some cases, the addition of an immune checkpoint inhibitor drug is associated with an increase in overall survival and progression-free survival [6]. There are still ongoing medical trials being conducted to more accurately define the safety and efficacy of atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide in patients with untreated extensive-stage SCKC [7,8]. When qualifying patients for treatment, it is very important to accurately and individually assess the degree of performance status (PS) of patients, distinguishing whether a poor PS score results from the neoplastic disease itself and its complications or from concomitant diseases [9].

PS is a tool often used by oncology healthcare professionals to assess the fitness of patients for systemic anticancer therapy and to predict prognosis in advanced malignancy. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) scoring system (Table 1) is considered an effective and reliable scale, which shows no significant variations in PS assessment by different healthcare professionals [10].

In a meta-analysis, Dall’Olio et al noticed that the high level of heterogeneity for overall survival analysis in the PS ≥2 population with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors could be the result of the patient heterogeneity within the PS 2 population and the subjectivity of the ECOG PS assessment. They indicate that poorer PS is correlated with lower immunotherapy efficacy [12].

Most case reports in the literature refer to the immunochemotherapy in NSCLC. There are reports of using chemotherapy with atezolizumab in an 80-year-old male patient with extensive-stage SCLC undergoing hemodialysis [13]. Authors of another case report also suggested that SCLC patients outside of clinical trials are typically in a poor ECOG state but could also benefit from immunotherapy [14].

In the presented study, we report a case of a 75-year-old female patient with advanced SCLC and an ECOG PS of 2 who responded well to combination immunochemotherapy with atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin. We draw attention to the qualification and benefits of combination therapy: immunochemotherapy in a patient with SCLC at an older age and an ECOG PS of 2 and the impact of possible adverse effects on this type of treatment.

Case Report

A 75-year-old woman who was an active smoker (about 30 pack-years), reported reduced exercise tolerance, exercise dyspnea, and periodic chest pain. She had been experiencing a gradual deterioration in her health for about 3 weeks. The patient associated respiratory system ailments with a past infection. She was taking symptomatic medications with no significant improvement. Two weeks prior, the patient noticed hemoptysis; therefore, she went to the family doctor. She was prescribed antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin) on an outpatient basis, and experienced no noticeable improvement. Then, the patient was referred to the Department of Lung Diseases.

Reported comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 2 months prior to admission. She had a mild course of COVID-19 and was treated at home only. For several years, the patient had been taking ipratropium bromide, salbutamol, temporarily, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ramipril).

The physical examination on admission showed increased blood pressure (160/90 mmHg), 95% oxygen saturation, bilateral edema of the lower limbs, and tachycardia, and chest auscultation showed diminished respiratory sound on the right side, with soft wheezing. The result of the ECOG PS score was 2, based on the patient’s daily activity: unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours. In laboratory tests, the abnormalities found were increased parameters of inflammation, hypoxemia without hypercapnia, and increased level of NT-proBNP.

A chest X-ray was performed (Figure 1), followed by a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdominal cavity. A tumor in the hilum of the right lung with mediastinal lymphadenopathy and hypodense areas in the liver, corresponding to metastases, were found (Figure 2).

Bronchoscopy showed a neoplastic, submucosal wall infiltration of the right main bronchus, covered with necrotic masses. In the upper lobe bronchi, segment 1 was narrowed, and segments 2 and 3 were unchanged. The intermediate bronchus was narrowed and was circularly infiltrated with neoplasm masses (Figure 3). In the histopathological examination, SCLC was diagnosed (Figure 4).

A CT scan of the central nervous system with contrast was performed and no metastases were found. The stage of disease was defined as cT4N2M1, stage IV.

Because of the exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the features of decompensated heart failure, the current treatment was changed, and olodaterol + tiotropium, diuretics, and beta-blockers were used. The patient also received antibiotic therapy (levofloxacin) owing to the increase in inflammatory parameters. After 10 days of therapy, clinical improvement was achieved. There was no lower limb edema, no signs of pulmonary edema or airway obstruction, and the heart rate was regular at 70 beats per min. The ECOG PS was rated as 1.

The multidisciplinary council discussed whether the patient was eligible for combination treatment with immunochemotherapy. The discussion concerned the patient’s age, comorbidities, and general condition and the advancement of the disease.

Due to the improvement of the patient’s general condition after the described treatment, it was decided to administer the combination therapy every 21 days as follows: atezolizumab: 1200 mg on day 1; etoposide: 130 mg on days 1–3 (100 mg/ m2); and carboplatin 330 mg (AUC: 5) on day 1.

After 2 cycles of immunochemotherapy, the patient came to the clinic with a worsened general condition (ECOG PS of 2). The patient reported weakness and dizziness. Physical examination revealed pale skin and a Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) scale grade 1 maculopapular rash, and chest auscultation revealed diminished respiratory sound on the right side (as before). Laboratory tests showed anemia (grade G3) and thrombocytopenia (grade G2). Two units of blood were transfused, which improved the blood count parameters.

During hospitalization, a control contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and abdominal cavity showed a significant reduction in the size of the tumor in the hilum of the right lung. At the level of the carina, the nodal masses were approximately 16 mm in diameter (previously, 37 mm). There was no evidence of liver metastases.

At the multidisciplinary council, owing to the good response in imaging tests and the balance of the patient’s general condition, it was decided to continue the combination treatment, but with a 25% reduction in the dose of chemotherapeutic agents.

After another 2 treatment cycles, the patient assessed her condition as good. The general condition of the patient was established as an ECOG PS of 1. No adverse effects of the treatment were observed. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest and abdominal cavity showed a significant regression of the underlying disease (Figure 5).

In a subsequent follow-up after 4 cycles of combined treatment, complete regression was achieved. There were no treatment adverse effects, except for CTCAE grade G1 maculopapular rash, which did not require treatment. After completion of the combined treatment, the therapy was continued with atezolizumab alone. After 2 cycles of atezolizumab, progression was observed in a follow-up CT scan. The patient was qualified for second-line treatment with topotecan in a minimal dose, but owing to observed pancytopenia and worsening of the patient’s general condition, she was qualified for best palliative care.

The assessment of the effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with an ECOG PS ≥2 is difficult owing to the insufficient representation of this group of patients in clinical trials. There is an ongoing clinical trial for these patients, which addresses this problem and perceives it as important and actual issue, but recruitment is still in progress and no results have been published yet [15].

The sparse case reports in the literature show that an elderly patient undergoing hemodialysis safely received this kind of treatment [13] and describe a good response in a patient with poorer PS scores and indicate that there is a lack of research in this group [14].

Yan Wu et al [14] reported the case of a 68-year-old patient who was a cigarette smoker and was admitted to the pulmonary hospital with a cough, chest tightness, and asthma, similar to our present case. Physicians found the patient’s right neck lymph nodes were enlarged. After 4 cycles of treatment, which was similar to that used in our patient, partial regression was achieved and the patient’s quality of life improved significantly. The authors mentioned moderate adverse events but did not describe them.

The first-line treatment of patients with disseminated SCLC was based solely on etoposide and platinum derivatives [3]. The breakthrough came in 2019 when new therapeutic options appeared, including immunotherapy, which was added to classic chemotherapy. The simultaneous use of chemotherapy and immunotherapy may lead to an increase in the effectiveness of anti-cancer treatment in patients with SCLC and improve their quality of life [16,17]. Combined treatment increases tumor immunogenicity. It should be emphasized that combined treatment does not increase the toxicity of the drugs used, which shows that such a combination is well tolerated [6].

Currently, in Poland, we commonly use 2 drugs that are monoclonal antibodies directed against the ligand of programmed cell death: atezolizumab and durvalumab. Atezolizumab has been approved for treatment under the Ministry of Health’s drug program since July 2021, and durvalumab is available under the Emergency Access to Drug Technologies program.

In the phase III study IMpower 133, a group of 403 patients with stage IV SCLC was treated with first-line chemotherapy etoposide and carboplatin with or without atezolizumab. Overall survival was 2 months longer in the group receiving the additional immunocompetent drug [18]. The efficacy of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with SCLC was also demonstrated in the Caspian phase III clinical trial. A total of 805 patients with extensive-stage SCLC were divided into 3 groups, and an advantage in terms of overall survival was demonstrated in patients additionally receiving immunotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone [19].

Extending overall survival when combining atezolizumab or durvalumab with platinum-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment improves the prognosis and should be the standard of care in the treatment of patients with disseminated SCLC [20].

It is worth noting that also in the case of NSCLC, patients with an ECOG PS of 2 constitute a huge, heterogeneous group of patients, including approximately 40% of patients [21]. Data on the benefits of immunotherapy with lower performance levels are limited and most often refer to patients with NSCLC. In a study regarding the use of immunotherapy in patients with an ECOG PS 2 score, Mojsak et al [22] showed that these patients may benefit from this approach in terms of increased overall survival and progression-free survival. This benefit is modest compared to that in people with a better PS score, but given the low toxicity profile and proven safety of such therapy, it is an option that should be considered in patients with NSCLC. It seems that these conclusions can be applied in a similar way to patients with SCLC; however, data on this subject are sparse and further research is needed. In the case of SCLC, the group of patients with an ECOG PS of 2, as shown by personal observation, is larger than that of patients with NSCLC, and the disease is most often diagnosed in an extensive stage [4]. In the event of adverse effects of therapy, they can be effectively treated and do not have to lead to the termination of therapy.

In our case report, the patient was not disqualified from immunochemotherapy because of her age and comorbidities. The patient’s treatment for chronic diseases was optimized, thus improving her general condition. The symptoms of cancer may also be alleviated after therapy administration. Each such case should be treated individually and the decision should be made by a multidisciplinary council.

Conclusions

This report has presented a 75-year-old patient with advanced small cell lung cancer and an ECOG PS of 2 who responded to combined immunochemotherapy with atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin. The adverse effects observed during immunotherapy were not always the reason for discontinuation of the therapy. In the described case, combined immunochemo-therapy treatment turned out to be safe for the patient and resulted in a beneficial effect in the form of complete remission in the lungs and the liver. After completion of the combined treatment, maintenance therapy with atezolizumab, and then second-line treatment, the patient was qualified for best palliative care because of worsening of her general condition.

The use of immunochemotherapy in older adults with SCLC appears to be a viable option that may benefit these patients. It should be emphasized that advanced age or comorbidities do not determine the qualification for such treatment; rather, this is determined by the general condition of the patient. The compensation of comorbidities improved the PS score in our patient. The assessment of the effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with an ECOG PS ≥2 is difficult owing to the insufficient representation of this group of patients in clinical trials.

References:

1.. Dyzmann-Sroka A, Malicki J, Jędrzejczak A, Cancer incidence in the Greater Poland region as compared to Europe: Rep Pract Oncol Radiother, 2020; 25(4); 632-36

2.. Adamek M, Biernat W, Chorostowska-Wynimko J, Lung cancer in Poland: J Thorac Oncol, 2020; 15(8); 1271-76

3.. Simon M, Argiris A, Murren JR, Progress in the therapy of small cell lung cancer: Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2004; 49(2); 119-33

4.. Jackman DM, Johnson BE, Small cell lung cancer: Lancet, 2005; 366(9494); 1385-96

5.. Krzakowski M, Orłowski T, Roszkowski K, [Small cell lung cancer diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of Polish Lung Cancer Group]: Pneumonol Alergol Pol, 2007; 75(1); 88-94 [in Polish]

6.. Tariq S, Kim SY, Monteiro de Oliveira Novaes J, Cheng H, Update 2021: Management of small cell lung cancer: Lung, 2021; 199(6); 579-87

7.. Updated March 7, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2022. https:////clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04920981

8.. , A study of atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus etopo-side to investigate safety and efficacy in patients with untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (MAURIS) ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04028050 Updated March 17 2022. Accessed May 30, 2022 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04028050

9.. Seve P, Sawyer M, Hanson J, The influence of comorbidities, age, and performance status on the prognosis and treatment of patients with metastatic carcinomas of unknown primary site: A population-based study: Cancer, 2006; 106(9); 2058-66

10.. Azam F, Latif MF, Farooq A, Performance status assessment by using ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score for cancer patients by oncology healthcare professionals: Case Rep Oncol, 2019; 12(3); 728-36

11.. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group: Am J Clin Oncol, 1982; 5(6); 649-55

12.. Dall’Olio FG, Maggio I, Massucci M, ECOG performance status ≥2 as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced non small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors – a systematic review and meta-analysis of real world data: Lung Cancer, 2020; 145; 95-104

13.. Imaji M, Fujimoto D, Kato M, Chemotherapy plus atezolizumab for a patient with small cell lung cancer undergoing haemodialysis: A case report and review of literature: Respirol Case Rep, 2021; 9(5); e00741

14.. Wu Y, Liu Y, Sun C, Immunotherapy as a treatment for small cell lung cancer: A case report and brief review: Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2020; 9(2); 393-400

15.. , Patients With ES-SCLC and ECOG PS = 2 Receiving AtezolizumabCarboplatin-Etoposide (SPACE), ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04221529 Updated April 27, 2021. Accessed May 30, 2022 https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04221529

16.. Kim J, Chen D, Immune escape to Pd-L1/PD-1 blockade: Seven steps to success (or failure): Ann Oncol, 2016; 27(8); 1492-504

17.. Park R, Shaw JW, Korn A, McAuliffe J, The value of immunotherapy for survivors of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: Patient perspectives on quality of life: J Cancer Surviv, 2020; 14(3); 363-76

18.. Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: N Engl J Med, 2018; 379(23); 2220-29

19.. Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial: Lancet, 2019; 394(10212); 1929-39

20.. Mathieu L, Shah S, Pai-Scherf L, FDA approval summary: Atezolizumab and durvalumab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy in extensive stage small cell lung cancer: Oncologist, 2021; 26(5); 433-38

21.. Prelaj A, Ferrara R, Rebuzzi SE, EPSILoN: A prognostic score for immunotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A validation cohort: Cancers (Basel), 2019; 11(12); 1954

22.. Mojsak D, Kuklińska B, Minarowski Ł, Mróz RM, Current state of knowledge on immunotherapy in ECOG PS 2 patients. A systematic review: Adv Med Sci, 2021; 66(2); 381-87

Case report A Challenging Diagnosis of HHV-8-Associated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified, in a Yo...

Am J Case Rep In Press ; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.945162

Case report Statin-Induced Autoimmune Myopathy: A Diagnostic Challenge in Muscle Weakness

Am J Case Rep In Press ; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.944261

Case report Rare Right Ventricular Calcified Amorphous Tumor Mimicking Malignancy: A Case Report

Am J Case Rep In Press ; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943908

Case report Optimal Airway Management in Severe Maxillofacial Trauma: A Case Report on Submental Intubation

Am J Case Rep In Press ; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.944387

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 mar 2024 : case report 41,089 neurocysticercosis presenting as migraine in the united states.

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report 32,075 A Report on the First 7 Sequential Patients Treated Within the C-Reactive Protein Apheresis in COVID (CACOV...

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

23 Feb 2022 : Case report 19,033 Penile Necrosis Associated with Local Intravenous Injection of Cocaine

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250

19 Jul 2022 : Case report 18,427 Atlantoaxial Subluxation Secondary to SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Rare Orthopedic Complication from COVID-19

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

Your Privacy

We use cookies to ensure the functionality of our website, to personalize content and advertising, to provide social media features, and to analyze our traffic. If you allow us to do so, we also inform our social media, advertising and analysis partners about your use of our website, You can decise for yourself which categories you you want to deny or allow. Please note that based on your settings not all functionalities of the site are available. View our privacy policy .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 05 July 2023

A comprehensive analysis of lung cancer highlighting epidemiological factors and psychiatric comorbidities from the All of Us Research Program

- Vikram R. Shaw 1 ,

- Jinyoung Byun 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Rowland W. Pettit 1 ,

- Younghun Han 1 , 2 ,

- David A. Hsiou 4 ,

- Luke A. Nordstrom 4 &

- Christopher I. Amos 1 , 2 , 3

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 10852 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1115 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

- Cancer epidemiology

- Lung cancer

- Risk factors

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States. Investigating epidemiological and clinical parameters can contribute to an improved understanding of disease development and management. In this cross-sectional, case–control study, we used the All of Us database to compare healthcare access, family history, smoking-related behaviors, and psychiatric comorbidities in light smoking controls, matched smoking controls, and primary and secondary lung cancer patients. We found a decreased odds of primary lung cancer patients versus matched smoking controls reporting inability to afford follow-up or specialist care. Additionally, we found a significantly increased odds of secondary lung cancer patients having comorbid anxiety and insomnia when compared to matched smoking controls. Our study provides a profile of the psychiatric disease burden in lung cancer patients and reports key epidemiological factors in patients with primary and secondary lung cancer. By using two controls, we were able to separate smoking behavior from lung cancer and identify factors that were mediated by heavy smoking alone or by both smoking and lung cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Multimorbidity clusters in patients with chronic obstructive airway diseases in the EpiChron Cohort

Association between medicated obstructive pulmonary disease, depression and subjective health: results from the population-based Gutenberg Health Study

Introduction.

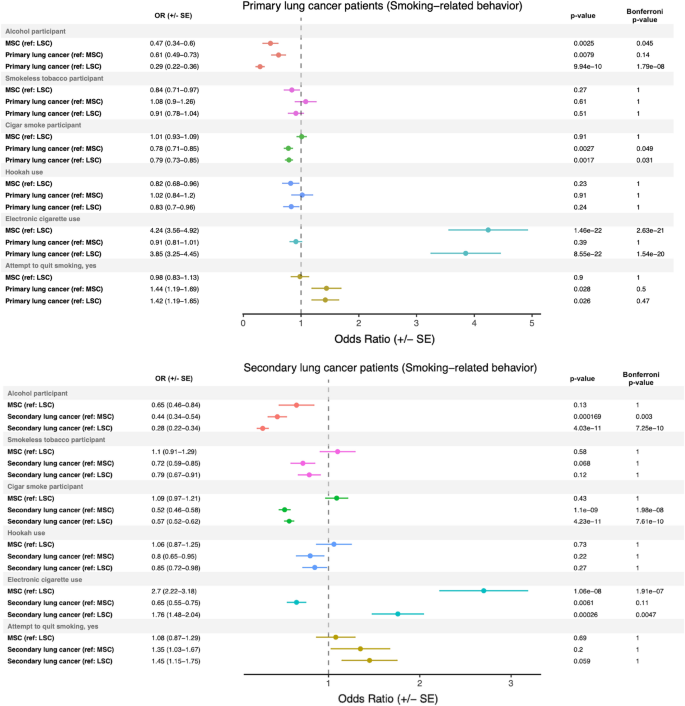

In 2022, approximately 236,000 lung cancer diagnoses and 130,000 lung cancer deaths were expected to occur in the United States (US) 1 . Every day, roughly 350 patients are expected to die from lung cancer, making it the leading cause of cancer-related death in the US 1 . Tumors in the lungs can be classified as primary lung cancer, including small-cell or non-small-cell lung cancer, or secondary lung cancer, which typically arises from the metastasis of breast 2 , colorectal 3 , renal 4 , testicular 5 , and uterine cancer 6 , among other forms of cancer. Many primary lung cancers are attributed to modifiable risk factors, such as smoking 1 , 7 , secondhand smoke 7 , excess body weight 8 , red and processed meat consumption 7 , alcohol intake 7 , and various occupational exposures 9 . However, cigarette smoking is a well-known risk factor for primary lung cancer and is attributed as the leading cause of more than 80% of lung cancer cases in the US 1 .

Although cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor for the development of lung cancer, numerous studies have demonstrated that a family history of lung cancer is also associated with an increased risk 10 . Even after accounting for age, sex, smoking history, and occupation, studies suggest a 2–4-fold increase in lung cancer risk for first-degree relatives of lung cancer patients 10 . Other epidemiologic factors, such as barriers to healthcare, can impact lung cancer development and outcomes, especially in vulnerable populations 11 . Studies estimate that only 5–18% of patients at high risk for lung cancer receive low dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening 12 . Investigating smoking-related behaviors is also crucial in the context of lung cancer risks, including e-cigarette use and smokeless tobacco. While nicotine replacement and pharmacological therapies along with behavior therapies have led to improved smoking cessation rates, the accessibility of e-cigarettes has led to an increase in their usage 13 , 14 . A particular concern is that e-cigarette users often also use cigarettes, thus increasing their lung cancer risk 15 . Notably, a literature gap exists in understanding the complex interplay between smoking, e-cigarette or smokeless tobacco use, and lung cancer, which this study aims to address.

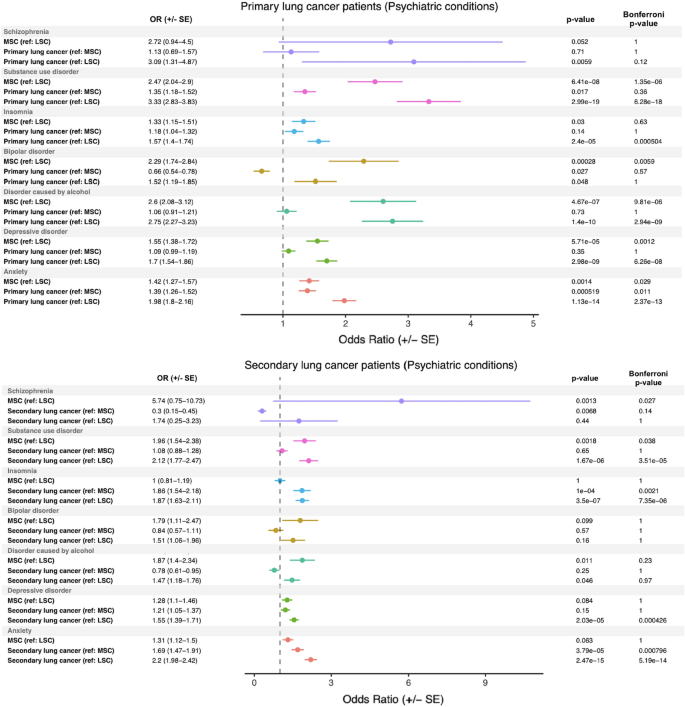

Finally, the psychiatric disease burden associated with both smoking and lung cancer is well-documented 16 , 17 , 18 . However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the differences in the psychiatric disease burden between primary and secondary lung cancer. Understanding which psychiatric diseases are comorbid with both primary and secondary lung cancer can help physicians develop treatment plans tailored to the individual patient.

To obtain a more comprehensive understanding of lung cancer development, treatment, and outcomes, it is essential to investigate epidemiological factors beyond cigarette smoking. This investigation can help develop better risk-based lung cancer screening methods and outcome prediction models that can draw on data from diverse sources 19 . This study aims to explore several key factors that may contribute to primary and secondary lung cancer, including lung cancer family history, barriers to healthcare, smoking-related behaviors, and psychiatric comorbidities. To understand better the impact of these factors, we designed a case–control analysis using two control groups (light smokers and matched smokers) to study the effects of smoking, lung cancer, and comorbid psychiatric conditions. Specifically, this study aims to answer the research question of whether the prevalence and impact of smoking-related behaviors, psychiatric comorbidities, and other epidemiological factors differ between primary and secondary lung cancer patients compared to light smoking and matched smoking controls.

Materials and methods

All of us research program.

The All of Us Research Program is a prospective cohort study with the objective of recruiting at least one million individuals in the US to provide a comprehensive database that enables researchers to investigate the effects of lifestyle, access to care, family history, environment, and genomics on participant health 20 . The program collects data through self-reported surveys, electronic health records (EHRs), and physical wearables such as Fitbit devices. Of the 372,082 patients in the All of Us Research Program, 54.1% are white, 19.7% are black or African American, 3.3% are Asian, 0.60% are Middle Eastern or North African, and 0.11% are Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Data from this program are accessible at http://www.allofus.nih.gov , and this study was conducted on version 6 of the data utilizing the All of Us Researcher Workbench. Supplementary Material provide codes utilized to query EHRs for lung cancer and psychiatric conditions.

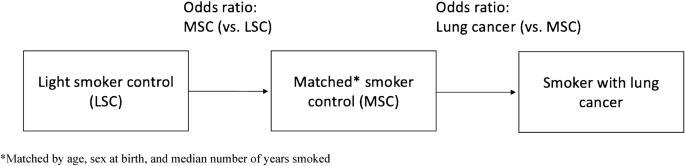

Lung cancer patient and control selection

Using the cohort builder function within the All of Us workbench, we created cohorts for patients with primary and secondary lung cancer based on source concept names ( Supplementary Material ). To protect individual-level patient information and in accordance with the All of Us data access policy, we excluded a small number of patients from both the primary and secondary lung cancer cohorts whose sex at birth survey answer categories contained fewer than 20 participants. Controls were divided into two groups: a light smoking control (LSC) and a matched smoking control (MSC). Light smoking controls in primary lung cancer and secondary lung cancer are designated as LSC-1 and LSC-2, respectively. Matched smoking controls in primary and secondary lung cancer are designated as MSC-1 and MSC-2, respectively. Control group participants were matched with patients based on their current age at the time of this study in 5-year intervals, sex at birth, and smoking status from a sample excluding primary and secondary lung cancer patients. The controls were matched by randomly selecting the control group participant with the appropriate inclusion criteria for a given matched lung cancer patient from a list of eligible control participants (i.e., same age, sex at birth, and smoking status as matched lung cancer patient). While smoking pack years is a well-established metric for smoking history 21 , we used the number of years smoked as the matching criteria because not all patients filled out both years smoked and the average number of daily cigarettes, which are needed to calculate the pack-year metric. LSC controls answered the “Number of Years Smoked” question from the “Lifestyle” survey with an answer less than or equal to 5, which is a well-published “years smoked” cutoff for light smokers 22 , 23 , while MSC controls were matched based on the exact number of years smoked. Fewer secondary lung cancer patients completed the “Number of Years Smoked” question, leading to a smaller sample size for the matched smoking controls in secondary lung cancer. We excluded answers of “PMI: Skip” and “PMI: Don’t Know” when calculating smoking-related demographic information such as the average daily cigarette number, the current average daily cigarette number, the daily smoking starting age, and the number of years smoked.

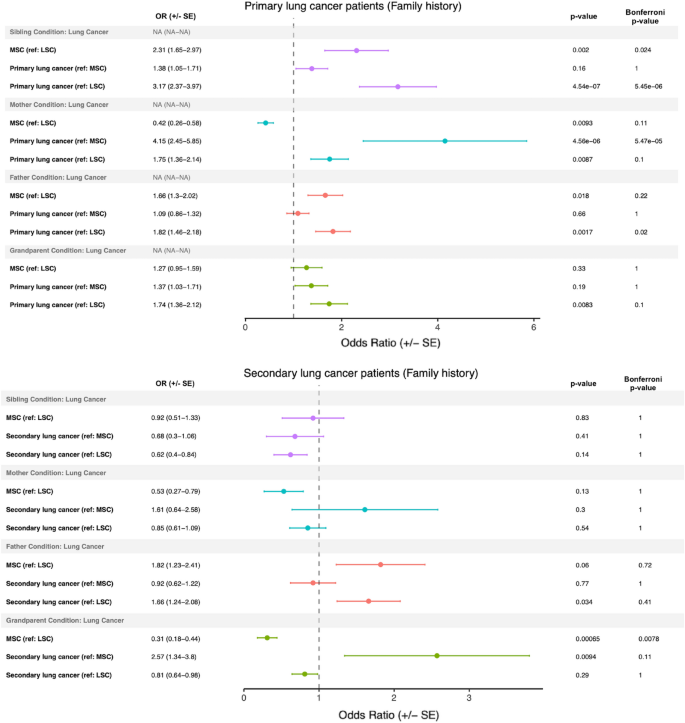

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios were used to generate forest plots, and the following R (v 4.2.2) packages were used for statistical analysis or plotting: epitools (v 0.5.10.1) 24 , tidyverse (v 1.3.2) 25 , patchwork (v 1.1.2) 26 , and ggplot2 (v 3.4.0) 27 . Mid p-values are commonly used in the analysis of odds ratios and are calculated by taking the midpoint of the range of p-values with a full description available in the documentation for the epitools 24 R package. The epitools R package provides mid p-values, Fisher p-values, and Chi-squared p-values. Mid p-values are used for all p-values in this study except for the primary lung cancer vs. LSC and MSC vs. LSC comparisons for electronic cigarette use and in analysis of psychiatric comorbidities, in which cases Fisher exact p-values were used as the epitools program returned a value of 0 for the mid p-value. Bonferroni p-values were calculated by multiplying the shown p-value by the number of comparisons and are significant if they are less than 0.05. All p-values reported in results text are mid p-values.

Lung cancer patient and control demographics

We conducted a matched case–control study to investigate the epidemiological and clinical parameters of primary and secondary lung cancer. This study included two age- and sex-matched controls for each case: a light smoking control (LSC) and a matched smoking control (MSC), with the latter having smoked for an equivalent number of years as their respective lung cancer patient. From a total of 221,125 patients in the All of Us database with available electronic health record (EHR) data, we identified 1451 patients with primary lung cancer (prevalence of 0.66%) and 1161 patients with secondary lung cancer (prevalence of 0.53%). The median age of lung cancer patients in our cohorts at the time of this study was 72 for primary lung cancer and 67 for secondary lung cancer (Table 1 ), which aligns with the literature suggesting a median age of lung cancer diagnosis 70 for both men and women 28 . In our primary lung cancer cohort, 60.0% of patients reported female sex at birth, while 55.1% of secondary lung cancer patients did so. In our primary lung cancer cohort, 68.8% of patients were white, 16.7% were black or African American, 2.4% were Asian, and 7.7% were Hispanic. In our secondary lung cancer cohort, 68.6% of patients were white, 10.1% were black of African American, 3.2% were Asian, and 14.8% were Hispanic.

The lifestyle survey data from participants offered insights into smoking behaviors and patterns. Of the primary lung cancer patients, 72.8% self-reported having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, compared to 46.6% of secondary lung cancer patients (Table 1 ). In the light smoking controls without primary lung cancer (LSC-1), the median years smoked was 3 (interquartile range [IQR]: 2–5). Primary lung cancer patients and matched smoking controls without primary lung cancer (MSC-1) reported a median of 35 years smoked (IQR: 21.5–45) and 35 years smoked (IQR: 21–45), respectively. In the light smoking controls without secondary lung cancer (LSC-2), the median years smoked was 3 (IQR: 2–4). Secondary lung cancer patients and matched smoking controls without secondary lung cancer (MSC-2) reported a median of 25 years smoked (IQR: 11–40) and 24.5 years smoked (IQR: 11–40), respectively.

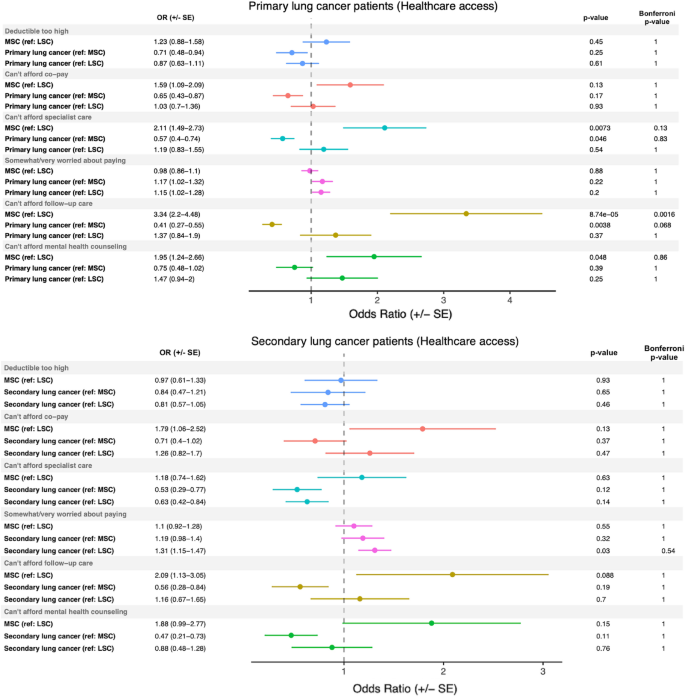

Differences in access to healthcare in primary and secondary lung cancer