- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

- Signs of Burnout

- Stress and Weight Gain

- Stress Reduction Tips

- Self-Care Practices

- Mindful Living

How to Recognize Burnout Symptoms

What to do if your physically and emotionally burned out at work

Burnout vs. Depression

- Take the Burnout Quiz

- Risk Factors

- Prevention and Treatment

- Next in How Stress Impacts Your Health Guide How Stress Can Cause Weight Gain

Is your job making you exhausted? Does the thought of dragging yourself to work fill you with dread? Or have you reached the point where you just don't care about your job anymore? If so, you might be experiencing burnout—a type of work-related exhaustion that can bleed over into other areas of your life.

Burnout is a type of exhaustion that can happen when you face prolonged stress that eventually results in severe physical, mental, and emotional fatigue.

Excessive workplace stress for prolonged periods can lead to burnout. However, it can also happen in other areas of life where you face too much stress for too long, such as when dealing with caregiving, relationship, parenting, or financial challenges.

So, what does burnout look like, exactly? Symptoms of burnout include feeling exhausted, empty, and unable to cope with daily life. If left unaddressed, your burnout may even make it difficult to function. Keep reading to learn more about the physical and mental symptoms of burnout, factors that may increase your risk, and a few recovery strategies .

Signs You're Burning Out

Recognizing the signs can help you better understand whether the stress you are experiencing is impacting you in a negative way. Here are a few to look for:

- Gastrointestinal problems

- High blood pressure

- Poor immune function (getting sick more often)

- Reoccurring headaches

- Sleep issues

- Concentration issues

- Depressed mood

- Feeling worthless

- Loss of interest or pleasure

- Suicidal ideation

What Does Burnout Mean?

Burnout is a reaction to prolonged or chronic job stress . It is characterized by three main dimensions:

- exhaustion,

- cynicism (less identification with the job),

- and feelings of reduced professional ability.

More simply put, if you feel exhausted, start to hate your job , and begin to feel less capable at work, you are showing signs of burnout.

Most people spend the majority of their waking hours working. So, if you hate your job, dread going to work, and don't gain any satisfaction from what you're doing, it can take a serious toll on your life. This toll shows up via burnout symptoms.

The term “burnout” is a relatively new term, first coined in 1974 by Herbert Freudenberger in his book, "Burnout: The High Cost of High Achievement." Freudenberger defined burnout as "the extinction of motivation or incentive, especially where one's devotion to a cause or relationship fails to produce the desired results."

Symptoms You Might Be Experiencing Burnout

Burnout isn’t a diagnosable psychological disorder , but that doesn't mean it shouldn't be taken seriously. Burnout symptoms can affect you both physically and mentally. Feeling burned out can contribute to mental health conditions like anxiety and depression, and the ongoing stress you are experiencing can take a massive toll on both your physical and mental health.

Physical Burnout Symptoms

When you experience burnout, your body will often display certain signs. Research indicates that some of the most common physical burnout symptoms include:

Because burnout is caused by chronic stress, it's helpful to also be aware of how this stress, in general, affects the body. Having chronic stress in your life doesn't necessarily mean that you are experiencing burnout. Unaddressed chronic stress, however, can eventually lead to burnout.

Chronic stress may be felt physically in terms of having more aches and pains, low energy levels, and changes in appetite. All of these physical signs suggest that you may be experiencing burnout.

Health Risks of Burnout

Chronic stress is associated with a wide range of negative health complications and outcomes, including heart disease, weight changes, depression, high blood pressure, and irritable bowel syndrome. Researchers have also connected stress-related disorders to an increased risk of death.

Mental Burnout Symptoms

Burnout also impacts you mentally and emotionally. Here are some of the most common mental symptoms of burnout:

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

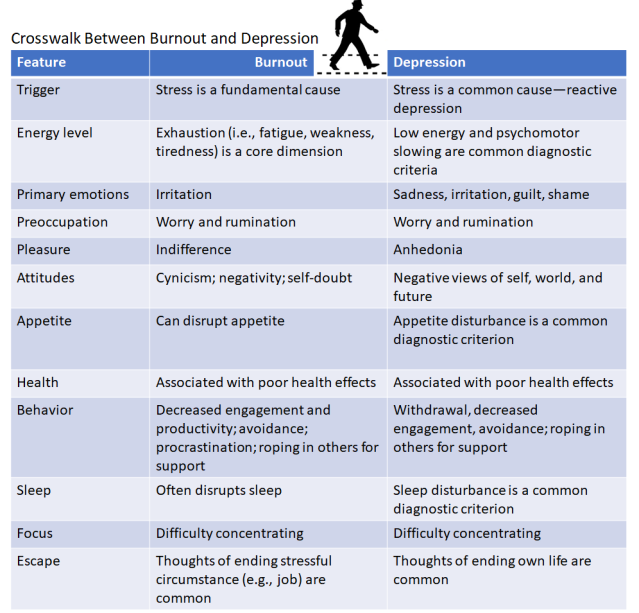

Burnout shares symptoms with some mental health conditions, such as depression. Depression symptoms also include a loss of interest in things, feelings of hopelessness, cognitive and physical symptoms, as well as thoughts of suicide. How can you tell if what you are feeling is burnout versus depression?

The key differences center on where and when you experience symptoms. Burnout symptoms tend to be focused on work (or the specific challenge you're dealing with), while depression tends to affect all areas of your life.

If you are depressed, you'll experience negative feelings and thoughts about all aspects of life, not just at work.

If this is how you feel, a mental health professional can help. Seeking help is important because individuals experiencing burnout may be at a higher risk of developing depression .

Are You Feeling Burnt Out? Take the Quiz

Try our fast and free burnout quiz to find out if some of the things you've been feeling may be a sign of burnout.

Factors That Put You at Risk of Burnout

People who work in certain stressful professions sometimes have a higher risk of burning out, but having a high-stress job doesn't always lead to burnout. You may not experience these ill effects if your stress is managed well.

However, some individuals (and those in certain occupations) are at a higher risk of having burnout symptoms than others. It often comes down to how you manage your stress and the support you have in your life.

For instance, a 2019 National Physician Burnout, Depression, and Suicide Report found that 44% of physicians experience burnout. Of course, it's not just physicians who are burning out. Workers in every industry at every level are at potential risk.

According to a 2018 Gallup report, there are five job factors that can contribute to employee burnout :

- Unreasonable time pressures . Employees who say they have enough time to do their work are 70% less likely to experience high burnout, while individuals who are not able to gain more time (such as paramedics and firefighters ) are at a higher risk of burnout.

- Lack of communication and support from management . Manager support offers a psychological buffer against stress. Employees who feel strongly supported by their manager are 70% less likely to experience burnout symptoms on a regular basis.

- Lack of role clarity . Only 60% of workers know what is expected of them. When expectations are like moving targets, employees may become exhausted simply by trying to figure out what they are supposed to be doing.

- Unmanageable workload . When the workload feels unmanageable, even the most optimistic employees will feel hopeless . Feeling overwhelmed can quickly lead to burnout symptoms.

- Unfair treatment . Employees who feel they are treated unfairly at work are 2.3 times more likely to experience a high level of burnout. Unfair treatment may include things such as favoritism, unfair compensation, and mistreatment from a co-worker .

The stress that contributes to burnout can come mainly from your job, but stressors from other areas of life can add to these levels as well. For instance, personality traits and thought patterns such as perfectionism , neuroticism , and pessimism can contribute to the stress you feel.

Other Causes of Burnout

Other factors that can contribute to burnout include:

- Poor communication from your employer

- Lack of clarity about your role or duties

- Intense pressure and tight deadlines

- Feeling like you have no control over your life or work

- Being mistreated by your boss or coworkers

- Excessive workloads or expectations

- Working too long without enough time to rest

- Work that is overly boring or stressful

- Not getting enough sleep

- Lack of social support

- Lack of recognition for your efforts

- Poor work-life balance

Press Play for Advice On Dealing With a Toxic Workplace

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring business expert Heather Monahan, shares how to survive a toxic workplace. Click below to listen now.

Subscribe Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Burnout Can Have Serious Effects

Chances are, you probably have a pretty good idea of whether you are burned out or not. So what happens if you don't take steps to address those feelings of exhaustion, disconnect, and distress? If left untreated, burnout symptoms can lead to:

You Might Feel Alienated From Your Work

Individuals experiencing burnout view their jobs as increasingly stressful and frustrating. You may grow cynical about your working conditions and the people you work with. You might also emotionally distance yourself and begin to feel numb about your work.

You May Become Emotionally Exhausted

Over time, untreated burnout symptoms can cause you to feel emotionally drained and unable to cope. You might find it harder and harder to deal with problems at work and at home. When you get home from work, you may be so fatigued that you don't have the physical or mental energy to engage in other activities that are part of your home life.

Your Performance at Work Can Suffer

Burnout affects everyday tasks at work, or in the home if your main job involves caring for family members . Individuals with burnout symptoms feel negative about tasks, have difficulty concentrating, and often lack creativity. Together, this results in reduced performance.

How to Prevent and Treat Burnout

Although the term "burnout" suggests that this may be a permanent condition, it is reversible. If you are feeling burned out , you may need to make some changes to your work environment.

How to Deal With Burnout

- Discuss work problems with your company's human resources department or your supervisor.

- Explore less stressful positions or tasks within your company.

- Take regular breaks.

- Learn meditation or other mindfulness techniques.

- Eat a healthy diet.

- Get plenty of exercise.

- Practice healthy sleep habits.

- Consider taking a vacation.

Approaching human resources about problems you're having or talking to a supervisor could be helpful if the company is invested in creating a healthier work environment. In some cases, a change in position or a new job altogether may be necessary to begin to recover from burnout. If you can't switch jobs, it may help to at least switch tasks .

It can also be helpful to develop clear strategies to help you manage your stress. Self-care strategies like eating a healthy diet, getting plenty of exercise, and engaging in healthy sleep habits may help reduce some of the effects of a high-stress job.

A vacation may offer you some temporary relief too, but a week away from the office won't be enough to help you beat burnout. Regularly scheduled breaks from work, along with daily renewal exercises, can be key to helping you combat burnout.

Social support is also critical. This can come from various sources, including coworkers, friends, family, and mental health professionals. If you are struggling to find the type of support you need, consider joining an in-person or online support group where you can talk about your challenges and get encouragement from people with the same type of experience.

If you are experiencing burnout and are having difficulty finding your way out, or you suspect that you may also have a mental health condition such as depression, seek professional treatment. Talking to a mental health professional can help you discover the strategies you need to feel your best.

Tileva A. How to douse chronic workplace stress before it explodes into full burnout . Society for Human Resource Management.

Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry . 2016;15(2):103–111. doi:10.1002/wps.20311

Brandstätter V, Job V, Schulze B. Motivational incongruence and well-being at the workplace: person-job fit, job burnout, and physical symptoms . Front Psychol . 2016;7:1153. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01153

Yale Medicine. Chronic stress .

American Psychological Association. Stress effects on the body .

Tian F, Shen Q, Hu Y, et al. Association of stress-related disorders with subsequent risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A population-based and sibling-controlled cohort study . The Lancet Regional Health - Europe . 2022;18:100402. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100402

Pereira H, Feher G, Tibold A, Monteiro S, Esgalhado G. Mediating effect of burnout on the association between work-related quality of life and mental health symptoms . Brain Sci . 2021;11(6):813. doi:10.3390/brainsci11060813

Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout-depression overlap: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;36:28-41. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.004

Kane L. Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019 .

Wigert B, Agrawal S. Employee burnout, Part 1: The 5 main causes . Gallup.

Wekenborg MK, Von dawans B, Hill LK, Thayer JF, Penz M, Kirschbaum C. Examining reactivity patterns in burnout and other indicators of chronic stress . Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;106:195-205. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.04.002

Demerouti E. Strategies used by individuals to prevent burnout. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45(10):1106-12. doi:10.1111/eci.12494

By Elizabeth Scott, PhD Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Burnout: Modern Affliction or Human Condition?

Burnout is generally said to date to 1973; at least, that’s around when it got its name. By the nineteen-eighties, everyone was burned out. In 1990, when the Princeton scholar Robert Fagles published a new English translation of the Iliad, he had Achilles tell Agamemnon that he doesn’t want people to think he’s “a worthless, burnt-out coward.” This expression, needless to say, was not in Homer’s original Greek. Still, the notion that people who fought in the Trojan War, in the twelfth or thirteenth century B.C., suffered from burnout is a good indication of the disorder’s claim to universality: people who write about burnout tend to argue that it exists everywhere and has existed forever, even if, somehow, it’s always getting worse. One Swiss psychotherapist, in a history of burnout published in 2013 that begins with the usual invocation of immediate emergency—“Burnout is increasingly serious and of widespread concern”—insists that he found it in the Old Testament. Moses was burned out, in Numbers 11:14, when he complained to God, “I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me.” And so was Elijah, in 1 Kings 19, when he “went a day’s journey into the wilderness, and came and sat down under a juniper tree: and he requested for himself that he might die; and said, It is enough.”

To be burned out is to be used up, like a battery so depleted that it can’t be recharged. In people, unlike batteries, it is said to produce the defining symptoms of “burnout syndrome”: exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of efficacy. Around the world, three out of five workers say they’re burned out. A 2020 U.S. study put that figure at three in four. A recent book claims that burnout afflicts an entire generation. In “ Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation ,” the former BuzzFeed News reporter Anne Helen Petersen figures herself as a “pile of embers.” The earth itself suffers from burnout. “Burned out people are going to continue burning up the planet,” Arianna Huffington warned this spring. Burnout is widely reported to have grown worse during the pandemic, according to splashy stories that have appeared on television and radio, up and down the Internet, and in most major newspapers and magazines, including Forbes , the Guardian , Nature , and the New Scientist . The New York Times solicited testimonials from readers. “I used to be able to send perfect emails in a minute or less,” one wrote. “Now it takes me days just to get the motivation to think of a response.” When an assignment to write this essay appeared in my in-box, I thought, Oh, God, I can’t do that, I’ve got nothing left, and then I told myself to buck up. The burnout literature will tell you that this, too—the guilt, the self-scolding—is a feature of burnout. If you think you’re burned out, you’re burned out, and if you don’t think you’re burned out you’re burned out. Everyone sits under the shade of that juniper tree, weeping, and whispering, “Enough.”

But what, exactly, is burnout? The World Health Organization recognized burnout syndrome in 2019, in the eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases, but only as an occupational phenomenon, not as a medical condition. In Sweden, you can go on sick leave for burnout. That’s probably harder to do in the United States because burnout is not recognized as a mental disorder by the DSM-5 , published in 2013, and though there’s a chance it could one day be added, many psychologists object, citing the idea’s vagueness. A number of studies suggest that burnout can’t be distinguished from depression, which doesn’t make it less horrible but does make it, as a clinical term, imprecise, redundant, and unnecessary.

To question burnout isn’t to deny the scale of suffering, or the many ravages of the pandemic: despair, bitterness, fatigue, boredom, loneliness, alienation, and grief—especially grief. To question burnout is to wonder what meaning so baggy an idea can possibly hold, and whether it can really help anyone shoulder hardship. Burnout is a metaphor disguised as a diagnosis. It suffers from two confusions: the particular with the general, and the clinical with the vernacular. If burnout is universal and eternal, it’s meaningless. If everyone is burned out, and always has been, burnout is just . . . the hell of life. But if burnout is a problem of fairly recent vintage—if it began when it was named, in the early nineteen-seventies—then it raises a historical question. What started it?

Herbert J. Freudenberger, the man who named burnout, was born in Frankfurt in 1926. By the time he was twelve, Nazis had torched the synagogue to which his family belonged. Using his father’s passport, Freudenberger fled Germany. Eventually, he made his way to New York; for a while, in his teens, he lived on the streets. He went to Brooklyn College, then trained as a psychoanalyst and completed a doctorate in psychology at N.Y.U. In the late nineteen-sixties, he became fascinated by the “free clinic” movement. The first free clinic in the country was founded in Haight-Ashbury, in 1967. “ ‘Free’ to the free clinic movement represents a philosophical concept rather than an economic term,” one of its founders wrote, and the community-based clinics served “alienated populations in the United States including hippies, commune dwellers, drug abusers, third world minorities, and other ‘outsiders’ who have been rejected by the more dominant culture.” Free clinics were free of judgment, and, for patients, free of the risk of legal action. Mostly staffed by volunteers, the clinics specialized in drug-abuse treatment, drug crisis intervention, and what they called “detoxification.” At the time, people in Haight-Ashbury talked about being “burnt out” by drug addiction: exhausted, emptied out, used up, with nothing left but despair and desperation. Freudenberger visited the Haight-Ashbury clinic in 1967 and 1968. In 1970, he started a free clinic at St. Marks Place, in New York. It was open in the evening from six to ten. Freudenberger worked all day in his own practice, as a therapist, for ten to twelve hours, and then went to the clinic, where he worked until midnight. “You start your second job when most people go home,” he wrote in 1973, “and you put a great deal of yourself in the work. . . . You feel a total sense of commitment . . . until you finally find yourself, as I did, in a state of exhaustion.”

Burnout, as the Brazilian psychologist Flávio Fontes has pointed out, began as a self-diagnosis, with Freudenberger borrowing the metaphor that drug users invented to describe their suffering to describe his own. In 1974, Freudenberger edited a special issue of the Journal of Social Issues dedicated to the free-clinic movement, and contributed an essay on “staff burn-out” (which, as Fontes noted, contains three footnotes, all to essays written by Freudenberger). Freudenberger describes something like the burnout that drug users experienced in his experience of treating them:

Having experienced this feeling state of burn-out myself, I began to ask myself a number of questions about it. First of all, what is burn-out? What are its signs, what type of personalities are more prone than others to its onslaught? Why is it such a common phenomenon among free clinic folk?

The first staff burnout victim, he explained, was often the clinic’s charismatic leader, who, like some drug addicts, was quick to anger, cried easily, and grew suspicious, then paranoid. “The burning out person may now believe that since he has been through it all, in the clinic,” Freudenberger wrote, “he can take chances that others can’t.” The person exhibits risk-taking that “sometimes borders on the lunatic.” He, too, uses drugs. “He may resort to an excessive use of tranquilizers and barbiturates. Or get into pot and hash quite heavily. He does this with the ‘self con’ that he needs the rest and is doing it to relax himself.”

The street term spread. To be a burnout in the nineteen-seventies, as anyone who went to high school in those years remembers, was to be the kind of kid who skipped class to smoke pot behind the parking lot. Meanwhile, Freudenberger extended the notion of “staff burnout” to staffs of all sorts. His papers, at the University of Akron, include a folder each on burnout among attorneys, child-care workers, dentists, librarians, medical professionals, ministers, middle-class women, nurses, parents, pharmacists, police and the military, secretaries, social workers, athletes, teachers, veterinarians. Everywhere he looked, Freudenberger found burnouts. “It’s better to burn out than to fade away,” Neil Young sang, in 1978, at a time when Freudenberger was popularizing the idea in interviews and preparing the first of his co-written self-help books. In “ Burn-out: The High Cost of High Achievement ,” in 1980, he extended the metaphor to the entire United States. “ WHY, AS A NATION, DO WE SEEM, BOTH COLLECTIVELY AND INDIVIDUALLY, TO BE IN THE THROES OF A FAST-SPREADING PHENOMENON—BURN-OUT? ”

Somehow, suddenly, burning out wasn’t any longer what happened to you when you had nothing, bent low, on skid row; it was what happened to you when you wanted everything. This made it an American problem, a yuppie problem, a badge of success. The press lapped up this story, filling the pages of newspapers and magazines with each new category of burned-out workers (“It used to be that just about every time we heard or read the word ‘burnout’ it was preceded by ‘teacher,’ ” read a 1981 story that warned about “homemakers burnout”), anecdotes (“Pat rolls over, hits the sleep button on her alarm clock and ignores the fact that it’s morning. . . . Pat is suffering from ‘burnout’ ”), lists of symptoms (“the farther down the list you go, the closer you are to burnout!”), rules (“Stop nurturing”), and quizzes:

Are you suffering from burnout? . . . Looking back over the past six months of your life at the office, at home and in social situations. . . . 1. Do you seem to be working harder and accomplishing less? 2. Do you tire more easily? 3. Do you often get the blues without apparent reason? 4. Do you forget appointments, deadlines, personal possessions? 5. Have you become increasingly irritable? 6. Have you grown more disappointed in the people around you? 7. Do you see close friends and family members less frequently? 8. Do you suffer physical symptoms like pains, headaches and lingering colds? 9. Do you find it hard to laugh when the joke is on you? 10. Do you have little to say to others? 11. Does sex seem more trouble than it’s worth?

You could mark questions with “X”s, cut out the quiz, and stick it on the fridge, or on the wall of your “Dilbert”-era cubicle. See? See? This says I need a break, goddammit.

Link copied

Sure, there were skeptics. “The new IN thing is ‘burnout,’ ” a Times-Picayune columnist wrote. “And if you don’t come down with it, possibly you’re a bum.” Even Freudenberger said he was burned out on burnout. Still, in 1985 he published a new book, “Women’s Burnout: How to Spot It, How to Reverse It, and How to Prevent It.” In the era of anti-feminist backlash chronicled by Susan Faludi, the press loved quoting Freudenberger saying things like “You can’t have it all.”

Freudenberger died in 1999 at the age of seventy-three. His obituary in the Times noted, “He worked 14 or 15 hours a day, six days a week, until three weeks before his death.” He had run himself ragged.

“Every age has its signature afflictions,” the Korean-born, Berlin-based philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes in “ The Burnout Society, ” first published in German in 2010. Burnout, for Han, is depression and exhaustion, “the sickness of a society that suffers from excessive positivity,” an “achievement society,” a yes-we-can world in which nothing is impossible, a world that requires people to strive to the point of self-destruction. “It reflects a humanity waging war on itself.”

Lost in the misty history of burnout is a truth about the patients treated at free clinics in the early seventies: many of them were Vietnam War veterans, addicted to heroin. The Haight-Ashbury clinic managed to stay open partly because it treated so many veterans that it received funding from the federal government. Those veterans were burned out on heroin. But they also suffered from what, for decades, had been called “combat fatigue” or “battle fatigue.” In 1980, when Freudenberger first reached a popular audience with his claims about “burnout syndrome,” the battle fatigue of Vietnam veterans was recognized by the DSM-III as post-traumatic stress disorder. Meanwhile, some groups, particularly feminists and other advocates for battered women and sexually abused children, were extending this understanding to people who had never seen combat.

Burnout, like P.T.S.D., moved from military to civilian life, as if everyone were, suddenly, suffering from battle fatigue. Since the late nineteen-seventies, the empirical study of burnout has been led by Christina Maslach, a social psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1981, she developed the field’s principal diagnostic tool, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, and the following year published “ Burnout: The Cost of Caring ,” which brought her research to a popular readership. “Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who do ‘people work’ of some kind,” Maslach wrote then. She emphasized burnout in the “helping professions”: teaching, nursing, and social work—professions dominated by women who are almost always very poorly paid (people who, extending the military metaphor, are lately classed as frontline workers, alongside police, firefighters, and E.M.T.s). Taking care of vulnerable people and witnessing their anguish exacts an enormous toll and produces its own suffering. Naming that pain was meant to be a step toward alleviating it. But it hasn’t worked out that way, because the conditions of doing care work—the emotional drain, the hours, the thanklessness—have not gotten better.

Burnout continued to climb the occupational ladder. “Burnout cuts across executive and managerial levels,” Harvard Business Review reported in 1981, in an article that told the tale of a knackered executive: “Not only did the long hours and the unremitting pressure of walking a tightrope among conflicting interests exhaust him; they also made it impossible for him to get at the control problems that needed attention. . . . In short, he had ‘burned out.’ ” Burnout kept spreading. “College Presidents, Coaches, Working Mothers Say They’re Exhausted,” according to a Newsweek cover in 1995. With the emergence of the Web, people started talking about “digital burnout.” “Is the Internet Killing Us?” Elle asked in 2014, in an article on “how to deal with burnout.” (“Don’t answer/write emails in the middle of the night. . . . Watch your breath come in and out of your nostrils or your stomach contracting and expanding as you breathe.”) “Work hard and go home” is the motto at Slack, a company whose product, launched in 2014, made it even harder to stop working. Slack burns you out. Social media burns you out. Gig work burns you out. In “Can’t Even,” a book that started out as a viral BuzzFeed piece, Petersen argues, “Increasingly—and increasingly among millennials—burnout isn’t just a temporary affliction. It’s our contemporary condition.” And it’s a condition of the pandemic.

In March, Maslach and a colleague published a careful article in Harvard Business Review , in which they warned against using burnout as an umbrella term and expressed regret that its measurement has been put to uses for which it was never intended. “We never designed the MBI as a tool to diagnose an individual health problem,” they explained; instead, assessing burnout was meant to encourage employers to “establish healthier workplaces.”

The louder the talk about burnout, it appears, the greater the number of people who say they’re burned out: harried, depleted, and disconsolate. What can explain the astonishing rise and spread of this affliction? Declining church membership comes to mind. In 1985, seventy-one per cent of Americans belonged to a house of worship, which is about what that percentage had been since the nineteen-forties; in 2020, only forty-seven per cent of Americans belonged to an institution of faith. Many of the recommended ways to address burnout—wellness, mindfulness, and meditation (“Take time each day, even five minutes, to sit still,” Elle advised)—are secularized versions of prayer, Sabbath-keeping, and worship. If burnout has been around since the Trojan War, prayer, worship, and the Sabbath are what humans invented to alleviate it. But this explanation goes only so far, not least because the emergence of the prosperity gospel made American Christianity a religion of achievement. Much the same appears to apply to other faiths. A Web site called productivemuslim.com offers advice on “How to Counter Workplace Burnout” (“There is barakah in earning a halal income”). Also, actually praying, honoring the Sabbath, and attending worship services don’t seem to prevent people who are religious from burning out, since religious Web sites and magazines, too, are full of warnings about burnout, including for the clergy. (“The life of a church leader involves a high level of contact with other people. Often when the church leader is suffering high stress or burnout he or she will withdraw from relationships and fear public appearances.”)

You can suffer from marriage burnout and parent burnout and pandemic burnout partly because, although burnout is supposed to be mainly about working too much, people now talk about all sorts of things that aren’t work as if they were: you have to work on your marriage, work in your garden, work out, work harder on raising your kids, work on your relationship with God. (“Are You at Risk for Christian Burnout?” one Web site asks. You’ll know you are if you’re driving yourself too hard to become “an excellent Christian.”) Even getting a massage is “bodywork.”

Burnout may be our contemporary condition, but it has very particular historical origins. In the nineteen-seventies, when Freudenberger first started looking for burnout across occupations, real wages stagnated and union membership declined. Manufacturing jobs disappeared; service jobs grew. Some of these trends have lately begun to reverse, but all the talk about burnout, beginning in the past few decades, did nothing to solve these problems; instead, it turned responsibility for enormous economic and social upheaval and changes in the labor market back onto the individual worker. Petersen argues that this burden falls especially heavily on millennials, and she offers support for this claim, but a lesson of the history of burnout is that every generation of Americans who have come of age since the nineteen-seventies have made the same claim, and they were right, too, because overwork keeps getting worse . It’s this giant mess that Joe Biden is trying to fix. In earlier eras, when companies demanded long hours for low wages, workers engaged in collective bargaining and got better contracts. Starting in the nineteen-eighties, when companies demanded long hours for low wages, workers put newspaper clippings on the doors of their fridges, burnout checklists. Do you suffer from burnout? Here’s how to tell!

Burnout is a combat metaphor. In the conditions of late capitalism, from the Reagan era forward, work, for many people, has come to feel like a battlefield, and daily life, including politics and life online, like yet more slaughter. People across all walks of life—rich and poor, young and old, caretakers and the cared for, the faithful and the faithless—really are worn down, wiped out, threadbare, on edge, battered, and battle-scarred. Lockdowns, too, are features of war, as if each one of us, amid not only the pandemic but also acts of terrorism and mass shootings and armed insurrections, were now engaged in a Hobbesian battle for existence, civil life having become a war zone. May there one day come again more peaceful metaphors for anguish, bone-aching weariness, bitter regret, and haunting loss. “You will tear your heart out, desperate, raging,” Achilles warned Agamemnon. Meanwhile, a wellness site tells me that there are “11 ways to alleviate burnout and the ‘Pandemic Wall.’ ” First, “Make a list of coping strategies.” Yeah, no. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Burnout Is About Your Workplace, Not Your People

- Jennifer Moss

Leaders create the conditions that lead to burnout — or prevent it.

We often think of burnout as an individual problem, solvable with simple-fix techniques like “learning to say no”, more yoga, better breathing, practicing resilience. Yet, evidence is mounting that personal, band-aid solutions are not enough to combat an epic and rapidly evolving workplace phenomenon. In fact, they might be harming, not helping the battle. With “burnout” now officially recognized by the World Health Organization, the responsibility for managing it has shifted away from employees and toward employers. Burnout is preventable. It requires good organizational hygiene, better data, asking more timely and relevant questions, smarter budgeting (more micro-budgeting), and ensuring that wellness offerings are included as part of your well-being strategy

We tend to think of burnout as an individual problem, solvable by “learning to say no,” more yoga, better breathing techniques, practicing resilience — the self-help list goes on. But evidence is mounting that applying personal, band-aid solutions to an epic and rapidly evolving workplace phenomenon may be harming, not helping, the battle. With “burnout” now officially recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) , the responsibility for managing it has shifted away from the individual and towards the organization. Leaders take note: It’s now on you to build a burnout strategy.

- Jennifer Moss is a workplace expert, international public speaker, and award-winning journalist. She is the bestselling author of Unlocking Happiness at Work (Kogan Page, 2016) and The Burnout Epidemic (HBR Press, September 2021).

Partner Center

How to Prevent Burnout in the Workplace: 20 Strategies

Its impact is considerable.

Indeed, burnout among physicians, which is twice that of the general public, leads to emotional and physical withdrawal from work and can negatively impact safe, high-quality healthcare for patients (Olson et al., 2019).

The effect of burnout is widespread. The impact of increasing workload, a perceived lack of control, and job insecurity lead to high turnover, reduced productivity, and poor mental health (Kolomitro et al., 2019).

This article explores the warning signs of burnout in the workplace and what we can do to prevent it.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF) for free . These science-based exercises will equip you and those you work with, with tools to manage stress better and find a healthier balance in your life.

This Article Contains:

14 warning signs of workplace burnout, 8 strategies to prevent employee burnout, 6 programs & initiatives for hr professionals, preventing burnout when working from home, positivepsychology.com’s relevant resources, a take-home message.

In increasingly busy, high-pressure working environments, employees often become the shock absorbers , taking organizational strain and working longer, more frantic hours (Kolomitro et al., 2019).

The long-term impact is burnout , identified by “lower psychological and physical wellbeing, as well as dissatisfaction, and employee turnover” (Kolomitro et al., 2019).

“Burnout occurs when an individual experiences too much stress for a prolonged period,” writes researcher Susan Bruce (2009). The employee is left feeling mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausted. Not only that, they are less productive at work, show reduced concern for others, and are more likely to miss work (Bruce, 2009).

Its effects are not only felt by the individual. In education, for example, burned-out teachers can negatively impact their students’ education (Bruce, 2009).

Organizations with burned-out staff experience low productivity, lost working days, lower profits, reduced talent, and even damage to their corporate reputation (Bruce, 2009).

So how do we recognize the warning signs of burnout?

Once we can spot early predictors and signs of burnout, we can take action.

Writing for the Harvard Business Review , Elizabeth Grace Saunders (2021) describes how, without realizing and on the verge of burnout, she was “perpetually exhausted, annoyed, and feeling unaccomplished and unappreciated.”

There are many early predictors, indicators, and manifestations of stress that contribute to burnout.

The following factors are recognized as early predictors of burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2008):

- Job demands that exceed human limits.

- Role conflict leading to a perceived lack of control; being under pressure from several, often incompatible, demands that compete with one another.

- Insufficient reward and lack of recognition for the work performed, devaluing both the work and the worker.

- Lack of support from the manager or team, consistently associated with exhaustion.

- Work perceived as unfair or inequitable , caused by an effort–reward imbalance.

- Relationship between the individual and the environment leading to feelings of imbalance or a bad fit. Such incongruity connects with excessive job demands and unfairness at work.

The following feelings, physical complaints, and thought patterns accompany stress and manifest in the workplace (Bruce, 2009):

- Feelings : Tired, irritable, distracted, inadequate, and incompetent.

- Physical : Muscular aches and body pain, headaches, increased or reduced appetite, weight change, and nausea.

- Emotional : Feeling trapped, hopeless, and depressed.

- Mental : Poor concentration, muddled thinking, and indecisiveness.

Stress in the workplace can manifest as:

- Regularly arriving late to work

- Absenteeism

- Reduced goals, aspirations, and commitment

- Increased cynicism and apathy

- Poor treatment of others

- Relationship difficulties

- Increase in smoking and alcohol consumption

- Making careless mistakes

- Obstructive and uncooperative behavior

- Overspending

While burnout is unique for every individual, it can be spotted and avoided.

- Work satisfaction

- Organizational respect

- Employer care

- Work–life integration

Balancing all four factors is essential to overall employee wellbeing and reduces the likelihood of long-term and ultimately overwhelming pressure.

The following strategies can help find that balance and protect against burnout (Saunders, 2021; Boyes, 2021).

When workload and capacity are in balance, it is possible to get work done and find time for professional growth, development, rest, and work recovery.

Assess how you are doing in each of the following activities:

- Planning your work. Do you know what work is coming? What will you be working on next week? Do you have a shareable plan?

- Delegating tasks. Sometimes we steer away from handing over work to others, but it can be positive for both parties.

- Saying no. Saying no is necessary when you have too much work or someone else could perform it.

- Letting go of perfectionism. Sometimes producing a perfect piece of work is not required; sometimes, good enough is all that is needed.

If you are experiencing any of the symptoms of burnout, try to focus on each of the above actions. Proactive effort to reduce workload can be highly effective at removing some stressors impacting burnout.

Feeling out of control, a lack of autonomy, and inadequate resources impact your ability to succeed at what you are doing and contribute to burnout.

Do you get calls from your boss or answer emails late into the night or over the weekend?

Consider how you can regain control. Agree on a timetable for when you are available and what resources you need to do your job well. Gaining a sense of control over your environment can increase your sense of autonomy.

Community is essential to feeling supported. While you may not be able to choose who you work with, you can invest time and energy in strengthening the bonds you share with your coworkers and boss.

Positive group morale, where you can rely on one other, can make the team more robust and reduce the likelihood of burnout.

A sense of fairness at work can be helped by feeling valued and recognized for the contributions you make.

Let it be known that you would like to be mentioned as a contributor or become involved in presenting some of the team’s successes.

Value mismatch

“Burnout isn’t simply about being tired,” writes Saunders (2021). When your values cannot align with those of your organization, you may need to consider whether it is time to look for new opportunities.

Determine if you can find compatibility in your current position or whether another organization might be better suited to your values.

Task balancing

After delivering something highly demanding (cognitively, emotionally, or physically), it may be beneficial to switch to a less complex task.

Swapping between tasks of varying difficulty on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis can be an excellent way to regain balance and give yourself a break.

After putting together a complex report, presentation, or analysis, why not plan the rest of your week for organizing emails into folders?

Mental breaks

We sometimes feel unable to stop. We check emails while in line for a coffee and type up notes on the flight back from a business meeting. While it can seem essential when you are busy to keep pushing ahead, it is vital to take breaks. Use spare time to read a book, listen to music, talk to a friend, or run through breathing exercises.

Taking time out for yourself is crucial to your wellbeing and will ultimately benefit your performance.

Physical breaks

Stress and tension take their toll physically. You may notice tight shoulders or headaches. Learning to recognize times when you are most stressed or anxious can help. When you do, find a moment to take some slow breaths or go for a walk.

Download 3 Free Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to manage stress better and find a healthier balance in their life.

Download 3 Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

While burnout is damaging to the employee, it is also expensive for the business. In the U.S. alone, the cost of absenteeism is $300 billion a year in insurance, reduced productivity, and staff turnover (Peart, 2021).

HR professionals have an essential role to play in reducing the effect and likelihood of burnout within the working environment (Castanheira & Chambel, 2010).

Putting in effective workplace wellness practices can help. For them to be effective, they must be at an organizational level, reducing stress at work, fostering employee wellbeing, and upping employee engagement (Peart, 2021; Chamorro-Premuzic, 2021).

According to clinical psychologist and leadership consultant Natalia Peart (2021), it is possible to create a working environment that reduces stress. To do this, we must build positive, stress-reducing environments that integrate with day-to-day working habits.

Increase psychological safety

Staff must see work as nonthreatening, allowing them to work and collaborate effectively. We can help perceptions of psychological safety by:

- Giving staff clear goals

- Making sure they feel heard by management

- Making work challenging yet non-threatening

Create a culture where it is okay to fail. Recognize and encourage people who think outside the box.

Regular workday breaks

Our attention and ability to focus are limited. After two hours (or less), our concentration reduces significantly (Peart, 2021), which could make us more likely to make mistakes, become less creative, and lose the ability to solve complex problems.

Staff must be encouraged to take breaks without feeling guilty. It is vital that they take time away from their desk regularly and as needed.

Placing entries in the calendar can help by setting aside time. And leading by example can help reduce stress and create an environment conducive to consistent performance.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Private spaces

While open offices are commonplace, they can be a cause of ongoing distraction.

Create spaces where staff can work uninterrupted and encourage them to turn off email and other messaging services at predefined times.

Set work boundaries

There will be times when working outside core hours may be necessary, but there is still a need to agree on typical workday expectations. Regularly answering emails late in the evening or over the weekend can increase employee anxiety and the sense of never leaving work.

Setting boundaries, flexible working, and providing additional time off can restore work–life balance.

Increase employee engagement

Improving the connection staff feel with their workplace and coworkers can heighten job satisfaction while reducing stress (Peart, 2021).

Engagement can be promoted through a culture of:

- Transparency It is vital to understand how work aligns with corporate goals.

- Using strengths and talents When people use their strengths, they feel more competent and engaged.

- Autonomy Staff are “43% less likely to experience high levels of burnout” when they decide on how and when they complete their work (Peart, 2021).

- Recognition Supporting and recognizing good work reduces stress while promoting a sense of belonging.

- Sense of purpose Feeling a sense of purpose in what we do adds meaning to otherwise tedious tasks. Share the company’s goals and communicate their positive effect on the community.

Hire better bosses

Good leaders must be hired or created, shielding employees from stress. However, rather than being seen as a source of calm and inspiration, managers often become the cause of stress. This is especially the case when managers make poor decisions, are abusive, or alienate their staff.

Hiring teams must take more time scrutinizing candidates who apply for leadership roles, identifying their empathy, emotional intelligence , and ability to perform under pressure.

While working from home removes commuting times and can allow us to take our children to school, it may be overshadowed by long working hours and a sense that we never leave work.

“The risk of burnout when working from home is substantial” write Laura Giurge and Vanessa Bohns (2021).

In an environment where the line between work and home life can quickly become blurred, it is crucial to our mental health that we agree upon and implement boundaries.

Even a non-urgent email sent after hours can create a sense of urgency or leave us with the weight of the action on our mind until we log on the next day. Working from home can also cause staff to feel indebted to their employer and mistakenly believe they need to work more intensely for more hours each day.

There are ways to create boundaries when working from home and reduce loneliness and burnout (Giurge & Bohns, 2021; Moss, 2021):

- Put on work clothes. Wearing something different when working from home can create a sense of performing a work activity in a separate environment.

- Commute to work. Even a walk around the block before heading to a dedicated space to work can create a feeling of separation.

- Maintain temporal boundaries. Create a work schedule that fits your needs and your organization’s, such as taking the children to school and stopping for lunch. Respect your own time and that of your colleagues. They may have different schedules for their commitments.

- Create an out-of-office reply. Create an automated email reply for when you are performing non-work activities or need time to focus uninterrupted on your tasks.

- Virtual coffee breaks. Staff should be encouraged to take time away from the desk for a walk with a friend, a casual chat, or to grab a coffee. Taking even 10 minutes will ultimately benefit concentration and focus. Finding ways to “carve out non-work time and mental space” are crucial when working from home, where boundaries are so unclear (Giurge & Bohns, 2021).

- Reducing loneliness. While working from home can be incredibly beneficial or even necessary, it may become a source of loneliness. Scheduling an in-office day once a month (as long as a time can be agreed upon and works for all remote workers) where staff can get together and have a catch-up can improve bonds between workers while creating a sense of shared goals.

15 Minutes a day to prevent burnout – Paul Koeck

We have many resources that can help with managing stress, overcoming obstacles, and dealing with difficult situations.

- 5-4-3-2-1 Stress Reduction Technique Use your five senses to ground yourself in the moment and slow down thinking.

- Coping With Stress Identifying and understanding what causes you stress can help you regain control over how you respond.

- Coping – Stressors and Resources Consider past, current, and anticipated stressors, and plan coping strategies to manage them.

- It Could Be Worse Build resilience by challenging unhelpful thought patterns and processes .

17 Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others manage stress without spending hours on research and session prep, this collection contains 17 validated stress management tools for practitioners . Use them to help others identify signs of burnout and create more balance in their lives.

17 Exercises To Reduce Stress & Burnout

Help your clients prevent burnout, handle stressors, and achieve a healthy, sustainable work-life balance with these 17 Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises [PDF].

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Humans are curious.

We need a degree of stress to prevent boredom and frustration.

However, too much can lead to poor decision making and ineffective communication, negatively impact mental health, and ultimately cause burnout (Bruce, 2009).

Stress not only takes a toll on our physical and mental wellbeing, but also narrows our outlook, making long-term strategic thinking more difficult (Peart, 2021).

“Burnout is experienced as emotional exhaustion or depersonalization” (Olson et al., 2019) and is the ultimate destination for long-term stress. It can harm physical health, psychological wellbeing, and performance at work (Olson et al., 2019; Maslach & Leiter, 2008).

While unpleasant for the individual, it can also damage the organization, leading to failing performance, absenteeism, and disengagement.

Spotting the early warning signs, positive leadership , and protective and proactive policies can avoid or reduce burnout. A balanced work culture promotes a positive work environment and a growth mindset.

There is a proven link between job satisfaction and mental health, so finding a good balance for stress is vital. Low job satisfaction at work can predict depression, low self-esteem, and anxiety (Bruce, 2009).

Use this article’s guidance to recognize dangers or early warning signs in yourself, colleagues, or clients. Then take some steps discussed to help reduce or prevent damaging environments and invest in employees’ wellbeing and performance.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF) for free .

- Boyes, A. (2021). How to get through an extremely busy time at work. In HBR guide to beating burnout (pp. 29–34). Harvard Business Review Press.

- Bruce, S. P. (2009). Recognizing stress and avoiding burnout. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 1 (1), 57–64.

- Castanheira, F., & Chambel, M. J. (2010). Reducing burnout in call centers through HR practices. Human Resource Management , 49 (6), 1047–1065.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2021). Just hire better bosses. In HBR guide to beating burnout (pp. 189–194). Harvard Business Review Press.

- Giurge, L. M, & Bohns, V. K. (2021). How to avoid burnout while working from home. In HBR guide to beating burnout (pp. 35–40). Harvard Business Review Press.

- Hyett, M. P., & Parker, G. B. (2015). Further examination of the properties of the Workplace Well-Being Questionnaire (WWQ). Social Indicators Research , 124 (2), 683–692.

- Kolomitro, K., Kenny, N., & Sheffield, S. L. M. (2019). A call to action: Exploring and responding to educational developers’ workplace burnout and well-being in higher education. International Journal for Academic Development , 1–14.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 (3), 498–512.

- Moss, J. (2021). Helping remote workers avoid loneliness and burnout. In HBR guide to beating burnout (pp. 173–180). Harvard Business Review Press.

- Olson, K., Sinsky, C., Rinne, S. T., Long, T., Vender, R., Mukherjee, S., … Linzer, M. (2019). Cross-sectional survey of workplace stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Stress and Health , 35 (2), 157–175.

- Peart, N. (2021). Making work less stressful and more engaging for your employees. In HBR guide to beating burnout (pp. 139–148). Harvard Business Review Press.

- Saunders, E. G. (2021). Six causes of burnout, and how to avoid them. In HBR guide to beating burnout (pp. 23–28). Harvard Business Review Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Wow, a very well-researched report with clearly explained content. Although the articles took the form of a generalised format which is why there was a less evidence-based approach, the author did a marvellous work.

Question: Is burnout predictive? In an education study, how would predictive burnout be validated in an evidence-based educational environment?

Thank you for your comment and your question. Burnout is most certainly predictive, and therefore also preventative. There has been a plethora of research on protective factors of burnout as well as what can actually predict burnout.

I think this article and this article might be of interest to you since they discuss predictive burnout in educational environments.

I hope this helps.

Kind regards, -Caroline | Community Manager

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Recognizing High-Functioning Anxiety & 6 Tools to Manage It

As our lives get busier and busier and more and more crises develop on the world stage, we are seeing reports of increasing incidences of [...]

Moving From Chronic Stress to Wellbeing & Resilience

Stress. It can be as minute as daily hassles, car trouble, an angry boss, to financial strain, a death or terminal illness. The ongoing stressors [...]

3 Burnout Prevention Strategies for Type A Personality

Highly driven, goal-oriented, and somewhat impatient? You may be dealing with a Type A personality. Having a Type A personality comes with a mixed bag [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (55)

- Coaching & Application (59)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (27)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (46)

- Optimism & Mindset (35)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (48)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (20)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (40)

- Self Awareness (22)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (33)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (38)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (65)

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Stress Exercises Pack

The Face of Burnout in Nursing: My Personal Story and Lessons Learned

Photo by Artem Kovalev on Unsplash

Two-and-a-half years ago, I experienced severe burnout in my role as a night shift charge nurse in a cardiovascular ICU. This blog post shares my personal story, highlighting the common ingredients of burnout and the challenges I faced. Through this experience, I learned valuable lessons that can benefit both nurses and the health care industry as a whole.

Where it All Began

Transitioning from a clinical nurse educator to a night shift charge nurse in a new cardiovascular ICU was an exciting opportunity for me. However, it soon became overwhelming due to various factors. These included a surgeon I didn’t see eye-to-eye with, moral and ethical dilemmas in patient care, staffing challenges, and a hostile work environment created by lateral violence from coworkers.

Strained to the Breaking Point

As my anxiety grew, I struggled to meet expectations each night. While prioritizing patient care and my night shift team, I feared for our patients’ well-being. Frequently, we were overloaded with acute post-cardiothoracic surgery patients. Despite my efforts to manage admissions responsibly, I faced constant pressure. Doubts crept in, and I lost trust in myself and my ability to provide safe care.

The emotional toll affected my eating, sleeping, and overall well-being. I couldn’t disconnect from work. When I was at work I feared when my surgeon rounded or if I would need to call him in the middle of the night because a patient’s condition was declining. When I was off, I was worried about how the patients were doing and if there was anything I might have done wrong. It was nothing for me to randomly start crying at any moment.

I was afraid to leave because of the financial stability this position gave me and my family. But the last thing I wanted was to be responsible for a patient’s deterioration, or worse, a patient dying. I had to get out of there. To be honest, I wasn’t even sure I wanted to be a nurse anymore.

Seeking a Solution

My story of burnout is unique to me, but it echoes stories from many other nurses. After resigning, I realized I didn’t want to be a victim of burnout. I embarked on a healing journey and learned valuable lessons about myself and the life I wanted to create. While personal shifts are important, I also believe tangible solutions within the health care environment can significantly impact patient well-being and nurse satisfaction. Instead of dwelling on problems, I embraced a mindset of seeking solutions. Here are some actionable suggestions to create a safer, healthier health care workplace.

Four Suggestions for Improvement

- Suggest an acuity-based staffing model: An acuity-based staffing model, supported by research, adjusts nurse-to-patient ratios based on patient diagnoses and acuity. This allows nurses caring for higher-acuity patients to have a reduced nurse-to-patient ratio so they can be more attentive to patients’ needs and subtle changes. A nurse with a higher nurse-to-patient ratio will have patients with stable vital signs, controlled pain, and not showing signs of distress.

- Advocate for leadership presence on night shift: Night shift nurses often face resource limitations and imbalanced skill mixes, including more novice nurses. Communicating the challenges to leadership and inviting them to experience the night shift reality can help bridge the gap between awareness and action. Trust me, leadership doesn’t always know how things really are.

- Foster accountability within the team: Encourage a culture of mutual support and self-care. Don’t just come in each day to take care of your patients. Come in each day to take care of each other. Establish a buddy system to make sure you are taking your needed breaks, using the bathroom, and staying hydrated. By caring for each other, nurses can collectively prioritize well-being.

- Provide a comprehensive orientation for new hires: Play an active role in onboarding new nurses, ensuring they feel confident, competent, and welcomed into the team. Reducing turnover is essential to improving staffing situations and maintaining the effectiveness of any new staffing model.

Jenna Colelli, MSN, BSEd, RN, CCRN-K, is director of staff development for Wellington Regional Medical Center, Wellington, FL. In this role, she works to “mentor and empower nurses to care for themselves so they can better care for the patients we serve.”

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: guest author.

Thank you for this honest, thoughtful and insightful essay. Your suggested solutions are right on target. I hope the appropriate leaders heed your words and put them into practice. Good luck in your new position.

Thank you for speaking your truth. Best wishes for success in your new position. Gloria Cox MSN, BS Health Art, RN Retired Nurse Educator Vaccinator (Covid-19) 2021-2022

Thank you for this. I’m retired now but nursing can’t be like a production line, it requires attention to individuals- co-workers as well as patients. Our system is so fragmented that saving money in the hospital can seem like a win even if it increases costs elsewhere. We can do a lot to reduce burn-out and improve practice by caring for our team.

Comments are moderated before approval, but always welcome. Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from Off the Charts

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Employers need to focus on workplace burnout: Here's why

Concrete ways to address the problem with psychological science

- Healthy Workplaces

- Mental Health

Workplace burnout can be a serious problem for individual workers and entire organizations. The good news is there are ways to get ahead of it and methods to rectify it.

What it is: “Workplace” burnout is an occupation-related syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. Burnout can be measured and quantified using validated scientific tools. It involves ongoing emotional exhaustion, psychological distance or negativity, and feelings of inefficacy—all adding up to a state where the job-related stressors are not being effectively managed by the normal rest found in work breaks, weekends, and time off (World Health Organization, 2019).

What it isn’t: This isn’t “burnout” we use in casual conversation. True workplace burnout is specific to one’s job or occupation and is more concerning and detrimental than the daily irritations everyone experiences and most of us manage.

There are three dimensions to workplace burnout:

- Feelings of energy depletion or emotional exhaustion

- Increased mental distance from one’s work and negative or cynical feelings toward one’s work

- Reduced sense of efficacy at work

Mindy Shoss, PhD, professor of psychology at the University of Central Florida and associate editor of the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , says, “There are many potential causes of burnout in today’s workplaces—excessive workloads, low levels of support, having little say or control over workplace matters, lack of recognition or rewards for one’s efforts, and interpersonally toxic and unfair work environments. Add to that the constant hum of uncertainty about a possible recession, and it’s no surprise that burnout is on the rise in many workplaces.”

[ Related: A pandemic of burnout: 4 questions for Dan Pelton ]

Why workplace burnout matters

Decades of research shows an association between workplace burnout and a host of negative organizational, psychological, and even physical consequences, including:

Organizational

- Absenteeism

- Job dissatisfaction

- Presenteeism

Psychological

- Psychological distress

- Heart disease

- Musculoskeletal pain

(Salvagioni et al., 2017).

The facts and figures

According to leading scientific research, employees who experience true workplace burnout have a:

- 57% increased risk of workplace absence greater than two weeks due to illness (Borritz et al., 2010)

- 180% increased risk of developing depressive disorders (Ahola et al., 2005)

- 84% increased risk of Type 2 diabetes (Melamed et al., 2006)

- 40% increased risk of hypertension (von Känel et al., 2020)

Additionally, workplace burnout may impair short-term memory, attention, and other cognitive processes essential for daily work activities (Gavelin et al., 2022).

Dennis P. Stolle, JD, PhD, APA’s senior director of applied psychology, points out that burnout has consequences for organizational effectiveness, not just individuals. “When workers are suffering from burnout, their productivity drops, and they may become less innovative and more likely to make errors. If this spreads throughout an organization, it can have a serious negative impact on productivity, service quality, and the bottom-line.”

What you can do

Christina Maslach , PhD, one of the leading experts on workplace burnout, has emphasized that finding solutions to the problem of burnout requires considering the workplace, the worker, and the workplace/worker fit.

“We need to reframe the basic question from who is burning out to why they are burning out. It is not enough to simply focus on the worker who is having a problem—there must be a recognition of the surrounding job conditions that are the sources of the problem. That is why the job-person relationship is so important. Is there a good match between the worker and the workplace environment, which enables the worker to thrive and do well?” Maslach says.

Employers can

- Periodically measure whether workplace burnout is happening in their organization through thoughtful and systematic surveys.

- Keep track of workloads, regularly check in with workers on how they are doing, and encourage taking advantage of time off.

- Take a hard look at their organization’s practices to ensure that they are giving workers the control, flexibility, and resources needed to manage workload and job stress.

Employees can

- Prioritize self-care, including caring for both physical and emotional well-being.

- Set appropriate boundaries, including giving themselves permission to truly unplug from work for reasonable periods of time.

- Prioritize social relationships. Healthy relationships with coworkers, friends, and family can help buffer workplace stresses.

Employers and employees can

- Constantly strive for a healthy, supportive, and inclusive workplace that fosters a sense of trust and confidence that workers have each other’s backs.

- Regularly discuss whether workloads are reasonable and appropriate to ensure work is distributed in an equitable way and, if needed, restructure accordingly.

Sometimes the solution may be to redesign job responsibilities or move the employee to a different position in the same organization. Not only might this be good for the employee, but it may help the organization retain valuable talent. A win/win.

Related podcasts

Why we’re burned out and what to do about it, with Christina Maslach, PhD

How do you build a successful team? With Eduardo Salas, PhD

Mental health in the workplace

To Curb Burnout, Design Jobs to Better Match Employees’ Needs

The Burnout Challenge: Managing People’s Relationships with Their Jobs

Burnout: A Guide to Identifying Burnout and Pathways to Recovery

Ahola, K., Honkonen, T., Isometsä, E., Kalimo, R., Nykyri, E., Aromaa, A., & Lönnqvist, J. (2005). The relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders—Results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. Journal of Affective Disorders , 88 (1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.004

Borritz, M., Christensen, K. B., Bültmann, U., Rugulies, R., Lund, T., Andersen, I., Villadsen, E., Diderichsen, F., & Kristensen, T. S. (2010). Impact of burnout and psychosocial work characteristics on future long-term sickness absence. Prospective results of the Danish PUMA study among human service workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine , 52 (10), 964–970. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181f12f95

Gavelin, H. M., Domellöf, M. E., Åström, E., Nelson, A., Launder, N. H., Neely, A. S., & Lampit, A. (2022). Cognitive function in clinical burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress , 36 (1), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.2002972

Melamed, S., Shirom, A., Toker, S., & Shapira, I. (2006). Burnout and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study of apparently healthy employed persons. Psychosomatic Medicine , 68 (6), 863–869. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000242860.24009.f0

Salvagioni, D. A. J., Melanda, F. N., Mesas, A. E., González, A. D., Gabani, F. L., & de Andrade, S. M. (2017). Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE , 12 (10), Article e0185781. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185781

von Känel, R., Princip, M., Holzgang, S. A., Fuchs, W. J., van Nuffel, M., Pazhenkottil, A. P., & Spiller, T. R. (2020). Relationship between job burnout and somatic diseases: A network analysis. Scientific Reports , 10 (1), Article 18438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75611-7

World Health Organization. (2019). QD85 Burnout. In International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281

Recommended Reading

Related topics.

- Healthy workplaces

- 5 ways to improve employee mental health

- Psychology informs Surgeon General’s healthy workplace framework

- Worker well-being is in demand as organizational culture shifts

- Women leaders make work better

You may also like

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement

Sergio edú-valsania.

1 Department of Social Sciences, Universidad Europea Miguel de Cervantes (UEMC), C/Padre Julio Chevalier, 2, 47012 Valladolid, Spain; se.cmeu@udes

Ana Laguía

2 Department of Social and Organizational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), C/Juan del Rosal 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain; se.denu.isp@onairomaj

Juan A. Moriano

A growing body of empirical evidence shows that occupational health is now more relevant than ever due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This review focuses on burnout, an occupational phenomenon that results from chronic stress in the workplace. After analyzing how burnout occurs and its different dimensions, the following aspects are discussed: (1) Description of the factors that can trigger burnout and the individual factors that have been proposed to modulate it, (2) identification of the effects that burnout generates at both individual and organizational levels, (3) presentation of the main actions that can be used to prevent and/or reduce burnout, and (4) recapitulation of the main tools that have been developed so far to measure burnout, both from a generic perspective or applied to specific occupations. Furthermore, this review summarizes the main contributions of the papers that comprise the Special Issue on “Occupational Stress and Health: Psychological Burden and Burnout”, which represent an advance in the theoretical and practical understanding of burnout.

1. Introduction