Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest Content

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 11, Issue 1

- Relationship between continuity of primary care and hospitalisation for patients with COPD: population-based cohort study from South Korea

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6644-0808 Iyn-Hyang Lee 1 , 2 ,

- Eunjung Choo 3 ,

- Sejung Kim 4 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0299-5131 Nam Kyung Je 5 ,

- Ae Jeong Jo 4 and

- Eun Jin Jang 4

- 1 College of Pharmacy , Yeungnam University , Gyeongsan , Korea (the Republic of)

- 2 Department of Health Sciences , University of York , York , UK

- 3 College of Pharmacy , Ajou University , Suwon , Korea (the Republic of)

- 4 Department of Data Science , Andong National University , Andong , Korea (the Republic of)

- 5 College of Pharmacy , Pusan National University , Busan , Korea (the Republic of)

- Correspondence to Dr Iyn-Hyang Lee; leeiynhyang{at}ynu.ac.kr ; Dr Eun Jin Jang; ejjang{at}anu.ac.kr

Objectives The existing evidence for the impacts of continuity of care (COC) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is low to moderate. This study aimed to investigate the associations between relational COC within primary care and COPD-related hospitalisations using a robust methodology.

Design Population-based cohort study.

Setting National Health Insurance Service database, South Korea.

Participants 92 977 adults (≥40 years) with COPD newly diagnosed between 2015 and 2016 were included. The propensity score (PS) matching approach was used. PSs were calculated from a multivariable logistic regression that included eight baseline characteristics.

Exposure COC within primary care.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was the incidence of COPD-related hospitalisations. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate HRs and 95% CIs.

Results Out of 92 977 patients, 66 677 of whom were cared for continuously by primary doctors (the continuity group), while 26 300 were not (the non-continuity group). During a 4-year follow-up period, 2094 patients (2.25%) were hospitalised; 874 (1.31%) from the continuity group and 1220 (4.64%) from the non-continuity group. After adjusting for confounding covariates, patients in the non-continuity group exhibited a significantly higher risk of hospital admission (adjusted HR (aHR) 2.43 (95% CI 2.22 to 2.66)). This risk was marginally reduced to 2.21 (95% CI 1.99 to 2.46) after PS matching. The risk of emergency department (ED) visits, systemic corticosteroid use and costs were higher for patients in the non-continuity group (aHR 2.32 (95% CI 2.04 to 2.63), adjusted OR 1.25 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.31) and exp β =1.89 (95% CI 1.82 to 1.97), respectively). These findings remained consistent across the PS-matched cohort, as well as in the sensitivity and subgroup analyses.

Conclusions In patients with COPD aged over 40, increased continuity of primary care was found to be associated with less hospitalisation, fewer ED visits and lower healthcare expenditure.

- COPD epidemiology

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The raw data that support the findings of this study are available only for authorised researchers in South Korea and for a limited period due to the information protection law for patient privacy. Study protocol is available from the corresponding author on request.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2024-002472

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Clinical and economic outcomes improve with high levels of relational continuity between doctors and patients.

However, there is limited empirical evidence demonstrating the impact of continuous primary care on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related hospitalisations.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This population-based study, with internal validity, demonstrated that reduced continuity of care in primary settings correlated with a heightened risk of hospital admission.

The findings, investigated in a healthcare system with markedly different environments, would enhance the external validity of the evidence.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study highlights the need for further investigation into how factors influencing continuity levels vary according to different healthcare system environments.

Healthcare providers may need to prioritise strategies that enhance ongoing patient–provider relationships.

The evidence supports the development of policies that promote consistent primary care relationships.

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that primary care quality efficiently improves overall health outcomes, 1 2 and continuity of care (COC) is considered a core element of primary care. 3–5 According to a systematic review by Huntley et al , COC is one of four identified systemic features that affect unscheduled secondary care utilisation, and the other three were access, practice features and quality of care. 6 COC has been characterised by informational, management and relational continuity. 2 7–9 Informational continuity involves the exchange of medical histories among current and previous healthcare providers. Management continuity entails coordinating and harmonising care according to shared treatment plans across providers. 1 2 7 9 Relational continuity (also called interpersonal continuity) concerns long-term therapeutic relationships between patients and their healthcare providers. 2 While informational and management continuity is an issue among service providers, relational continuity centres on the relationship between the service provider and the patient. Relational continuity places focus on the individual rather than on the illness, this concept reflects the value of primary care. 1 A long-term patient–provider relationship can improve communication and establish trust, 1 2 10 which results in a greater willingness to share crucial information with providers and increases the likelihood of patients adhering to treatment and preventive advice. 10 These relationships also help healthcare providers understand their patients better, improve the effectiveness of chronic condition management and the development of long-term disease-monitoring strategies. 1 10 Undoubtedly, high-quality primary care can facilitate planned end-of-life care in the community rather than in hospital. 11 As a result, studies show that high relational COC might lower the risk of premature mortality and prevent the exacerbation of chronic conditions. 12–16 Furthermore, patients with higher relational continuity tend to use secondary care less 16–20 and lower medical costs. 16 21 22 Conversely, low relational continuity negatively affects patient experience. 23 24

Although evidence is accumulating for a wide range of conditions, evidence linking the benefits of high relational continuity in patients with specific conditions is insufficient. A recent systematic review expressed concern that the current level of evidence is low to moderate for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 12 After this systematic literature review, two new studies on COC in patients with COPD have been published. 25 26 However, the Canadian study still uses a design that measures exposure and outcome simultaneously, leading to confusion about the temporal relationship between cause and effect. 25 Additionally, concerns have been expressed that it will become difficult to maintain patient–doctor relationships as complexity increases in terms of illnesses and medical organisations. 4 27

Approximately, 97% of the Korean population is covered by the National Health Insurance (NHI) while the remaining 3% are covered by a medical aid programme (MedAid) that provides more comprehensive coverage to low-income households. 28 The South Korean healthcare system is composed of primary, secondary and tertiary institutions. A mandatory referral document is required only for accessing tertiary hospitals. Tertiary hospitals are mostly university-affiliated institutions located in a few metropolitan cities. They serve as major centres for medical education and training, offering a wide range of specialised medical treatments. In the absence of legal restrictions, except for those involving tertiary hospitals, patients often prioritise proximity to medical facilities. Patients may receive primary care at clinics or hospital outpatient departments if these are within their catchment area. As a result, the country has been evaluated to have a weak gate-keeping primary care function. 29 In this regard, the relationship between COC and outcomes in the Korean healthcare system has implications for other countries concerned about the weakening of primary care systems.

Set against the presented background, this study aimed to investigate the impacts of relational COC between patients with COPD and primary care doctors on clinical and economic outcomes. COPD is an ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC), and its effective management and treatment within ambulatory settings obviate hospital admission. 30 31 We hypothesised that high relational care continuity with a primary care doctor results in better clinical results and lower costs.

Study design and data source

This population-based cohort study was performed according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline. 32 Levels of patient relational COC with their doctors were explored, comparative cohorts based on COC levels were established and the associations between COCs and hospital admission rates and other outcome measures were investigated. Anonymised national insurance claims data between 2014 and 2021 provided by the Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) were analysed. The KNHIS database contains details of all claims made by Korean residents. These details include deidentified patient sociodemographic information, diagnoses, all medical services provided and medications dispensed and death records. 33

Study time frame

Figure 1 illustrates the study period from 2014 to 2021. Index dates were defined as the dates of the first diagnosis of COPD during 2015–2016. The 12-month period preceding the index date was defined as the preindex year. The exposure period was defined as the 2-year period following the index date, and the outcome period was defined as the period from the end of the exposure period to 31 December 2021. Patients were followed from the end of the exposure period until outcome determinations, death or the end of data collection, whichever came first.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Defined study periods.

Study population

Patients with COPD newly diagnosed in 2015–2016 at primary clinics, aged ≥40 years on index date, and who made at least four ambulatory visits during the exposure period were enrolled in the study. 19 34 COPD was identified using the International Classification of Disease, 10th revision (ICD-10) as diagnosis codes J42–44 but excluding McLeod syndrome (a genetic disease coded J43.0). Patients with a claims record for COPD in the preindex year were excluded, and those who visited tertiary facilities, died or experienced hospitalisations or emergency department (ED) visits during the exposure period were also excluded. After exclusions, the final analytic cohort contained 92 977 unique patients.

Measuring continuity of primary care

Continuity of primary care is conceptualised as the extent to which a patient’s visits are concentrated among primary care doctors. Primary care is defined differently across countries. 35 We defined primary care as community-based care and included visits to small-sized and medium-sized facilities, excluding tertiary hospitals, in the COC measurement. To measure COC, we used the Bice & Boxerman Continuity of Care Index (COCI) and Usual Provider Continuity (UPC). 21 36 37 COCI is a dispersion index, and a useful metric for patients who may potentially visit different providers and is used chiefly for claims data analysis. 38 COCI is recommended in South Korea because patients are almost free to contact doctors of choice due to the weak gatekeeper role of primary care. 29 In this study, we also calculated UPC because it is one of the most popular continuity indices used in studies. 38 UPC is a density index that quantifies patients’ visit patterns by focusing on specific providers. 38

Bice and Boxerman COCI and UPC were calculated using the following formulae. 37–39

Where N is the total number of visits made by a patient to a doctor, n i is the number of patient visits with provider i and M is the number of potentially available providers. In the UPC equation, provider i is the provider patients usually visit.

Both indices have a value of unity (1) if a patient always visits one specific health provider and a value of 0 if the patient visits different providers at each visit.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the incidence of COPD-related hospitalisation during the outcome period because hospitalisation rates for ACSCs can indicate the quality of primary care. Secondary outcomes were the incidence of COPD-related ED visits and COPD-related costs. Patients using corticosteroids in oral or injection form, defined as systemic corticosteroid use, were also investigated to evaluate COPD exacerbation. COPD-related medical costs were defined as the average annual medical costs for each year during the outcome period. Data related to COPD were identified by the ICD-10 diagnosis codes mentioned above. All medical costs were standardised costs to 2020 KRW to remove any effects of inflation.

Covariates included individual characteristics such as age and sex. NHI contributions were classified as high, moderate or low and used as proxies of patients’ economic circumstances. Two types of health insurance programmes, that is, NHI and MedAid were included. Locations of residences at index dates were classified as large urban (metropolitan cities), small urban (other cities) or rural areas. Large and small urban, and rural areas were classified based on population densities. Elixhauser Comorbidity Indices (ECIs) were computed as proxies of patient health statuses 40 based on diagnoses obtained from outpatient and inpatient records during the preindex year. In addition, we considered whether patients had a diagnosis of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, cancer, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis during the preindex year or were being prescribed inhalers for COPD treatment at index dates or systemic corticosteroids during the exposure period. Patients who made more than 14 outpatient clinic visits during the exposure period were defined as frequent doctor visitors (90th percentile or higher). Based on index dates, disability status was defined as none, moderate or severe, and smoking status as never-smoker, ex-smoker, smoker or no record. For reference purposes, we also collected average annual COPD-related medical costs during exposure periods.

Configuration of the continuity cohort

Interim analysis was conducted to determine continuity score distributions of primary care doctor visits during the exposure period. Interim analyses showed that patients with a COCI of 1 accounted for 71.7% of doctor visits and those with a UPC of 1 accounted for 71.7%. We allocated patients with a continuity score of 1 during the exposure period to the continuity group and the others to the non-continuity group. Propensity score (PS) matching was used to improve comparability between the continuity and non-continuity groups and to reduce the effect of known confounders on study outcomes. PS matching was performed using a logistic regression model containing age, sex, health insurance programme, insurance contributions, residence urbanisation level, disability, ECI score and asthma coexistence as covariates. The continuity group was matched 1:1 to the non-continuity group without replication using the nearest matching method with 0.2 times the logit of PS as a calliper.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics and healthcare utilisation were summarised using means, SD, medians and IQR for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Intergroup differences in baseline characteristics between the continuity and non-continuity groups were assessed using the absolute standardised difference method and when they exceeded 0.1, the intergroup difference was considered as a meaningful difference between the two groups existed. 41 COCIs, UPCs and annual health service utilisations during the exposure period in the two groups were compared by the independent t-test or the χ 2 test, based on type of data. The effects of COC on hospitalisation and ED visits due to COPD were assessed using a Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model that considered death as a competing risk. 42 HRs and 95% CIs were provided. The use of systemic corticosteroids was assessed using a logistic regression model, and the results are presented as ORs. COPD-associated costs were estimated using a gamma regression model, and results are reported as exponential coefficients. In the analysis of the total cohort, sex, age, insurance programme, insurance contributions, urbanisation level of residence, disability, ECIs, asthma coexistence, COPD inhaler use, systemic corticosteroid use during the exposure period, smoking and frequent doctor visits were adjusted as covariates, and in the PS matched cohort, COPD inhaler use, corticosteroid use during the exposure period, smoking and frequent doctor visits were adjusted as covariates. Individuals whose information about insurance contribution, living area and smoking status was missing were not excluded, and missing values were considered as an independent category in the statistical models. A cumulative incidence graph was used to compare the continuity and non-continuity groups. For sensitivity analysis, we calculated COCIs every 2 years following the index date to construct longitudinal data. These data were then analysed using the generalised estimating equations method, adjusting for the same baseline characteristics and covariates as in the adjusted model for the total cohort. Subgroup analyses were performed on basic characteristics. The analysis was conducted by using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute), and statistical significance was accepted for p values <0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

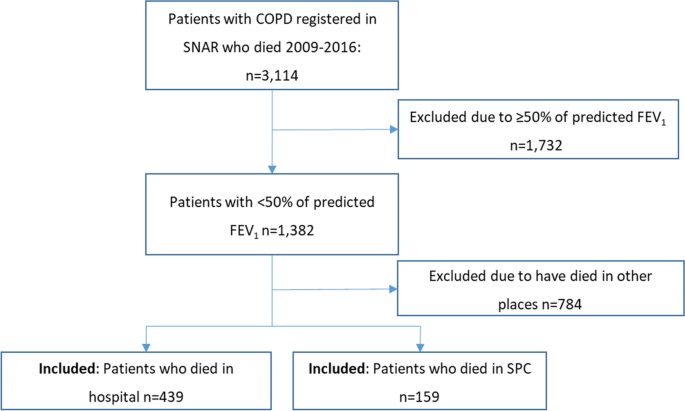

The selection process is shown in figure 2 . A total of 92 977 patients were eligible for analysis.

Identification of study participants and formation of study cohort. COCI, Continuity of Care Index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Indices; PS, propensity score.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population. After classifying patients according to the COCI criteria, 66 677 were allocated to the continuity group and 26 300 to the non-continuity group. In the continuity group, there were more female patients than in the non-continuity group. Patients in the non-continuity group were older, had more beneficiaries, more with disabilities, more who were former or current smokers, more who had five or more chronic conditions and a higher copresence of asthma than those in the continuity group. In the non-continuity group, patients were less likely to live in large urban areas. 25 866 patients in the non-continuity group were matched to an equal number of patients in the continuity group by PS matching. The characteristics of matched cohorts were well balanced, showing no meaningful differences in major factors ( table 1 ). In the exposure period, the non-continuity group made more frequent doctor visits and had higher medical expenses compared with the continuity group ( table 1 ).

- View inline

Baseline characteristics of study population and health service utilisation during the exposure period

Changes in COC

The mean COCI of study patients was 0.87 during the exposure period, which slightly decreased to 0.84 during the 4-year study outcome period. By group, while the mean COCI decreased from 1.0 to 0.96 in the continuity group, it remained around 0.54 in the non-continuity group throughout the study period ( online supplemental figure 1 ). COCI changes were similar in the PS-matched cohorts ( online supplemental figure 1 ). The mean UPCs were slightly larger than those of COCIs, and the pattern of changes was similar to that of the COCI ( online supplemental figure 1 ). The average study periods for the continuity and non-continuity groups were 5.89 (SD 0.88) and 5.74 (1.05) years, respectively, and in the PS-matched cohort were 5.82 (0.96) and 5.74 (1.05), respectively.

Supplemental material

Risks of hospital admission.

874 patients (1.31%) were hospitalised in the continuity group, and 1220 patients (4.64%) in the non-continuity for COPD-related reasons ( table 2 ). After adjusting for key covariates, patients in the non-continuity group were found to be at significantly higher risk of hospitalisation (adjusted HR 2.43 (95% CI 2.22 to 2.66)). Figure 3 presents the cumulative incidence of hospitalisation during the outcome period from the primary analysis. The sensitivity analysis indicated a reduced but consistent result (adjusted HR 1.25 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.36)). In the PS-matched cohort, adjusted HR for hospital admission was 2.21 (95% CI 1.99 to 2.46). The demographic features that increased the risk of hospitalisation included being men, aged 65 or older, residing in small urban or rural areas, using a COPD inhaler at the index date, using systemic corticosteroids during the exposure period, having coexistence asthma, being a past or current smoker and being a frequent doctor visitor ( online supplemental table 1 ).

Cumulative incidence of hospital admission and ED visit by level of continuity. (A) Hospital admissions in the total cohort, (B) Hospital admissions in the PS-matched cohort. (C) ED visits in the total cohort, (D) ED visits in the PS-matched cohorts. ED, emergency department; PS, propensity score.

Descriptive summary of study outcomes and association of continuity of primary care with study outcomes

Risks of ED visits

Patients in the non-continuity group were more likely to visit an ED than those in the continuity group (adjusted HR 2.32 (95% CI 2.04 to 2.63)) ( table 2 ). However, the magnitude of the adjusted HR insignificantly decreased to 1.13 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.28) in the sensitivity analysis (p=0.061). In the PS-matched cohort, the adjusted HR for an ED visit was 2.06 (95% CI 1.78 to 2.38). The demographic features that increased the risk of an ED visit were similar to those of hospital admission ( online supplemental table 1 ).

Risk of systemic corticosteroid use

6461 (9.69%) patients in the continuity group and 3807 (14.48%) in the non-continuity group were newly prescribed systemic corticosteroids ( table 2 ). After adjusting for covariates, the non-continuity group had a 1.25-fold higher risk of being prescribed systemic corticosteroids (adjusted OR 1.25 (95% CI 1.19 to 1.31)). The adjusted OR of the PS-matched cohort was similar (1.29 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.37)).

COPD-related medical costs

Mean annual COPD-related medical cost was significantly higher in the non-continuity group ( table 2 ). After adjusting for major covariates, gamma regression modelling analysis demonstrated patients in the non-continuity group spent on them about 1.89 (95% CI 1.82 to 1.97) times more than patients in the continuity group. The intergroup difference was similar for the PS-matched cohort (1.79 (95% CI 1.70 to 1.87) times more).

Subgroup analyses on hospitalisation and ED visits

Primary analysis trends were similar for all subgroups of the total cohort or PS-matched cohort ( online supplemental figure 2 ).

This study analysed nationwide claims data to investigate the impact of continuity of primary care on the clinical and economic outcomes of patients with COPD in the Korean healthcare environment. Study patients with low-level COCs with doctors were twice as likely to be hospitalised or visit an ED and incurred 1.8 times higher healthcare costs. In addition, the risk of receiving systemic corticosteroids due to COPD exacerbation was 1.25 times greater in the non-continuity group than in the continuity group, and similar results were obtained after PS matching. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses produced consistent results. The study shows that high relational continuity of primary care is associated with better health outcomes and lower healthcare costs, which concurs with previous studies. 12 Recently, a study conducted in Ontario, Canada, reported that patients with COPD aged over 35 who received non-continuous primary care had a 2.81-fold higher risk of hospitalisation and a 2.12-fold higher risk of emergency room visits. 25 Additionally, a Norwegian study found that patients in the lowest 30% for UPC had a 3.3-fold increased risk of death compared with those with a UPC of 1. 26

This study contributes as the robust methodology employed enhances the internal validity of the findings from previous studies. We analysed nationwide claims data for the entire Korean population. PS matching increased comparability between cohorts. In order to avoid overestimating outcome risks, the period measuring continuity and outcomes was separated and sensitivity analysis was conducted. 12 34 The analysis conducted on the PS-matched groups and the sensitivity analysis consistently yielded the same results, which underscored the reliability and validity of the study. Nonetheless, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the COC measurements used for the analysis were related to visit patterns and concentration rather than the interpersonal nature of the continuity relationship. 7 Second, we used claims data for the analysis, which inherently introduces its shortcomings. For example, the claims data did not include information about individual doctors, which can be more problematic in a hospital outpatient setting than in a clinic. To address this, we operationally defined visits to the same institution and the same department in the hospital outpatient setting as visits to the same provider. In the Korean healthcare reservation system, patients are typically scheduled to see the same doctor if they visit the same medical department within the institution. Another important shortcoming is that we were unable to incorporate objective parameters reflecting patient health statuses (eg, laboratory results) into the analysis. However, the use of systemic corticosteroids was included as a secondary outcome measure to assess disease exacerbation. Third, the results of this study should be interpreted with the understanding that they pertain to patients with COPD in the early stages of the disease. Future research should also evaluate the impact of COC on end-of-life management in COPD. Lastly, care should be taken when generalising our results because the primary care facilities of this study were chosen to reflect the Korean situation. While the inclusion criteria were limited to primary clinics, visits to small-sized and medium-sized facilities, excluding tertiary hospitals, were considered in the measurement of COCI. This might limit the comparability of this study with previous research. However, our results were obtained from a different healthcare setting and are concordant with those of previous studies. In this regard, our analysis may contribute to improving the external validity of this theme.

Interestingly, despite the nearly free choice of healthcare providers in the Korean healthcare system, the proportion of study patients with a COCI of 1 was high at 72%. A COCI of 1 indicates that patients exclusively visited one doctor throughout the observation period, rendering UPC-based analyses meaningless, as a COCI of 1 is equivalent to a UPC of 1. The unexpectedly high COCI value among Korean patients with COPD contrasts with approximately 46% of Korean patients with newly developed dyslipidaemia 16 and 62% of Austrian patients with diabetes who had a COCI of 1. 43 However, direct comparisons of COC measurements across diseases or countries are challenging. For instance, in Norway, the proportion of patients with a UPC≥0.75 were lower in asthma (42%–48%) or COPD (49%–52%) than in diabetes (59%) or heart failure (62%–72%), 44 which is the opposite of what was presented earlier. A recent study reported that COCI among patients with COPD in Norway was observed to be lower than that in Germany, even though Norway has a mandated gatekeeping system. 45 This suggests that various factors, beyond health policy, could influence COC. Although there is growing awareness of a positive association between COC and clinical results, understanding of the factors that influence COC is limited.

In this regard, further research is needed to determine the reasons for the high COC exhibited by Korean patients with COPD. One possible explanation may lie in the nature of COPD, which is characterised by symptoms such as persistent, progressive airflow limitation. As compared with other chronic conditions like dyslipidaemia and early hypertension, COPD can cause immediate discomfort and increase patient desire for medication. Moreover, there is a high probability that a patient will return to the same doctor when symptoms are adequately managed using medication. In this regard, one US study reported that COCIs for COPD were slightly higher than those for congestive heart failure or diabetes. 21 However, this might not be the sole reason for the high COC, given that in Taiwan, only 46% of patients with COPD exhibited a COCI of 1, even though the inclusion criteria in the Taiwanese study were similar to those in the present study. 22 The high proportion of patients with a COCI of 1 in this study may reduce comparability with other studies. Due to this high proportion, classifying all cases with a COCI less than 1 as non-continuity suggests that our non-continuity group may actually have more continuity than those in other studies, potentially undervaluing the impact of primary care continuity.

This study’s findings offer crucial insights for policy-makers and primary care providers. Despite evolving patient–doctor dynamics, it is vital for primary care providers to sustain ongoing relationships with patients. In healthcare systems without traditional family doctor models, efforts to foster consistent connections between patients and their doctors are essential. Exploring options such as proactive information sharing can address challenges linked to multiple doctor involvement. Additionally, coordinated care among healthcare professionals may ease the complexities of fragmented encounters.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study analysed claims data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (research management number NHIS-2023-1-211).

- Freeman GK ,

- Hjortdahl P

- Haggerty JL ,

- Freeman GK , et al

- Tarrant C ,

- Mainous AG , et al

- Te Winkel M ,

- Schers H , et al

- Huntley A ,

- Lasserson D ,

- Wye L , et al

- Salisbury C ,

- Sampson F ,

- Ridd M , et al

- Schers HJ ,

- Schellevis FG , et al

- Sweeney K , et al

- Green H , et al

- Engström S ,

- Ekstedt M , et al

- Pereira Gray DJ ,

- Sidaway-Lee K ,

- White E , et al

- Yang HK , et al

- Cheng H-M ,

- Lu M-C , et al

- Choo E , et al

- Campbell D ,

- Elliott M , et al

- Williams H , et al

- Chen W-H , et al

- Zielinski A

- Hussey PS ,

- Schneider EC ,

- Rudin RS , et al

- Rodriguez HP ,

- Rogers WH ,

- Marshall RE , et al

- Pollack CE ,

- Asch DA , et al

- Woodhouse K , et al

- Pahlavanyali S ,

- Hetlevik Ø ,

- Baste V , et al

- Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service & National Health Insurance Service

- Bardsley M ,

- Davies S , et al

- Elm E von ,

- Altman DG ,

- Egger M , et al

- National Health Insurance Sharing Service

- Lee J , et al

- van Walraven C ,

- Jennings A , et al

- Boxerman SB

- Steinwachs DM

- Sundararajan V ,

- Halfon P , et al

- Lonjon G , et al

- Austin PC ,

- Latouche A ,

- Geroldinger A ,

- Sauter SK ,

- Heinze G , et al

- Blinkenberg J , et al

- Swanson JO ,

- Sundmacher L , et al

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

I-HL and EJJ contributed equally.

Contributors I-HL, EJJ, NKJ and EC wrote the statistical analysis plan, analysed data and SK carried out data cleaning and statistical analyses. I-HL and EJJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AJJ, EC and SK prepared tables and figures. NKJ and AJJ critically reviewed and edited the first draft. EJJ supervised all statistical analysis processes. I-HL was a fund holder and supervised all process of this research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and met the ICMJE criteria for authorship. I-HL is the guarantor.

Funding This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) grant number (2022R1F1A1073485).

Disclaimer The funding organisations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note Transparency declaration: The lead author (I-HL) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Caregivers Corner

When to transition from curative measures to palliative or hospice care.

Deciding when to stop seeking curative measures and transition to palliative or hospice care is a deeply personal and often challenging decision. Understanding the differences between these types of care and recognizing the appropriate time for each can help families make informed choices.

Curative Measures vs. Palliative and Hospice Care Curative measures aim to cure or significantly prolong life by treating the underlying disease. These treatments can include surgeries, chemotherapy, radiation, and other aggressive interventions. While these measures can be effective, they may also come with significant side effects and a reduced quality of life.

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness. It is appropriate at any stage of a serious illness and can be provided alongside curative treatments. The goal of palliative care is to improve the quality of life for both the patient and their family by addressing physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.

Hospice care is a type of palliative care specifically for patients who are nearing the end of life, typically with a prognosis of six months or less if the disease follows its natural course. Hospice care prioritizes comfort and quality of life, rather than attempting to cure the illness. It often involves a team of healthcare professionals who provide medical, emotional, and spiritual support to the patient and their family.

When to Consider Palliative or Hospice Care

Frequent Hospitalizations: If a patient is experiencing frequent hospitalizations or emergency room visits without significant improvement, it may be time to consider palliative or hospice care.

Declining Health: When a patient's health is steadily declining despite aggressive treatments, and the treatments are causing more harm than benefit, transitioning to palliative or hospice care can provide better quality of life.

Symptom Management: If managing symptoms such as pain, breathlessness, or fatigue becomes the primary focus, palliative care can offer specialized support to alleviate these issues.

Patient and Family Wishes: Respecting the wishes of the patient and their family is crucial. If the patient expresses a desire to focus on comfort rather than curative treatments, it is important to honor their preferences.

Making the decision to transition from curative measures to palliative or hospice care is never easy, but understanding the options and recognizing the signs can help families provide the best possible care for their loved ones. By prioritizing comfort and quality of life, palliative and hospice care offer compassionate support during a challenging time.

If you need support in your caregiving journey reach out to the Duke Caregiver Support Program for free resources and support. Also, please watch our weekly caregiver educations segments every Monday on Eyewitness News 10-11am.

Related Topics

- HEALTH & FITNESS

- CAREGIVERS CORNER

- ABC11 TOGETHER

Helping an Aging Loved One with a Legacy Project

When caregiving clouds gather: a guide to finding your sunshine., harmonizing care: a guide for family caregivers to communicate., finding solace after loss: the road to recovery for family caregivers.

You must have javascript enabled to use this website.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Palliative care in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Results from a survey among hepatologists and palliative care physicians

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Foundation IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy.

- 2 Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, CRC "A. M. and A. Migliavacca" Center for Liver Disease, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

- 3 Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

- 4 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Humanitas University, Pieve Emanuele, Italy.

- 5 Division of Internal Medicine and Hepatology, Humanitas Research Hospital IRCCS, Rozzano, Italy.

- 6 Department of Oncology, ASST Lodi, Lodi, Italy.

- 7 UO Palliative Care, Department of Primary Care, APSS Trento, Italy.

- 8 Gastroenterology & Hepatology Unit, Department of Health Promotion, Mother & Child Care, Internal Medicine & Medical Specialties (PROMISE), University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy.

- 9 Fondazione FARO ETS, Turin, Italy.

- 10 Italian Journal of Palliative Care, Italian Society of Palliative Care, Milan, Italy.

- 11 Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

- 12 Unit of Semeiotics, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

- PMID: 39193728

- DOI: 10.1177/02692163241269794

Background: Delays and limitations of palliative care in patients with liver transplantation- ineligible end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system may be explained by different perceptions between hepatologists and palliative care physicians in the absence of shared guidelines.

Aim: To assess physicians' attitudes toward palliative care in end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma and to understand what the obstacles are to more effective management and co-shared between palliative care physicians and hepatologists.

Design: Members of the Italian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Italian Society of Palliative Care were invited to a web-based survey to investigate practical management attitude for patients with liver transplant- ineligible end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma.

Participants: Physician members of the of the two associations, representing several hospitals and services in the country.

Results: Ninety-seven hepatologists and 70 palliative care physicians completed the survey: >80% regularly follow 1-19 patients; 58% of hepatologists collaborate with palliative care physicians in the management of patients, 55% of palliative care physicians take care of patients without the aid of hepatologists. Management of cirrhosis differed significantly between the two groups in terms of prescription of albumin, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, anti-viral treatment, anticoagulation, indication to paracentesis and management of encephalopathy. Full-dose acetaminophen is widely used among hepatologists, while opioids are commonly used by both categories, at full dosage, regardless of liver function.

Conclusions: This survey highlights significant differences in the approach to patients with liver transplantation- ineligible end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, reinforcing the need for shared guidelines and further studies on palliative care in the setting.

Keywords: Liver cancer; albumin; cirrhosis; liver transplantation; pain.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Declaration of conflicting interestThe author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M. Iavarone: Advisory Board/Speaker Bureau for Bayer, Gilead Sciences, BMS, Janssen, Ipsen, MSD, BTG-Boston Scientific, AbbVie, Guerbet, EISAI, Roche, Astra-Zeneca; A. Aghemo: Advisory Board/Speaker Bureau for GILEAD SCIENCES, ABBVIE, MSD, MYLAN, ALFASIGMA, SOBI, INTERCEPT; P. Lampertico: Advisory Board/Speaker Bureau for BMS, ROCHE, GILEAD SCIENCES, GSK, ABBVIE, MSD, ARROWHEAD, ALNYLAM, JANSSEN, SBRING BANK, MYR, EIGER, ALIGOS, ANTIOS, VIR.

Related information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Spotify is currently not available in your country.

Follow us online to find out when we launch., spotify gives you instant access to millions of songs – from old favorites to the latest hits. just hit play to stream anything you like..

Listen everywhere

Spotify works on your computer, mobile, tablet and TV.

Unlimited, ad-free music

No ads. No interruptions. Just music.

Download music & listen offline

Keep playing, even when you don't have a connection.

Premium sounds better

Get ready for incredible sound quality.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

The prevalence and prognosis of cachexia in patients with non-sarcopenic dysphagia: a retrospective cohort study.

1. Introduction

2. materials and methods, 2.1. study design and patients, 2.2. diagnosis of sarcopenic dysphagia, 2.3. cachexia diagnostic criteria.

- Subjective symptom: loss of appetite;

- Objective measure: reduced grip strength (less than 28 kg in men and less than 18 kg in women);

- Biomarker: increased C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (greater than 0.5 mg/dL).

2.4. Outcomes and Other Data

2.5. statistical analysis, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Rech, R.S.; de Goulart, B.N.G.; Dos Santos, K.W.; Marcolino, M.A.Z.; Hilgert, J.B. Frequency and associated factors for swallowing impairment in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022 , 34 , 2945–2961. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rajati, F.; Ahmadi, N.; Naghibzadeh, Z.A.; Kazeminia, M. The global prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2022 , 20 , 175. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ribeiro, M.; Miquilussi, P.A.; Gonçalves, F.M.; Taveira, K.V.M.; Stechman-Neto, J.; Nascimento, W.V.; de Araujo, C.M.; Schroder, A.G.D.; Massi, G.; Santos, R.S. The Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dysphagia 2024 , 39 , 163–176. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Blanař, V.; Hödl, M.; Lohrmann, C.; Amir, Y.; Eglseer, D. Dysphagia and factors associated with malnutrition risk: A 5-year multicentre study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019 , 75 , 3566–3576. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Xue, W.; He, X.; Su, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, H. Association between dysphagia and activities of daily living in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024 , 1–17. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Roberts, H.; Lambert, K.; Walton, K. The Prevalence of Dysphagia in Individuals Living in Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024 , 12 , 649. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Almirall, J.; Rofes, L.; Serra-Prat, M.; Icart, R.; Palomera, E.; Arreola, V.; Clavé, P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a risk factor for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Eur. Respir. J. 2013 , 41 , 923–928. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Patel, D.A.; Krishnaswami, S.; Steger, E.; Conover, E.; Vaezi, M.F.; Ciucci, M.R.; Francis, D.O. Economic and survival burden of dysphagia among inpatients in the United States. Dis. Esophagus 2018 , 31 , dox131. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Márquez-Sixto, A.; Navarro-Esteva, J.; Batista-Guerra, L.Y.; Simón-Bautista, D.; Rodríguez-de Castro, F. Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia and Its Value as a Prognostic Factor in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Prospective Case-Control Study. Cureus 2024 , 16 , e55310. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kakehi, S.; Isono, E.; Wakabayashi, H.; Shioya, M.; Ninomiya, J.; Aoyama, Y.; Murai, R.; Sato, Y.; Takemura, R.; Mori, A.; et al. Sarcopenic Dysphagia and Simplified Rehabilitation Nutrition Care Process: An Update. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2023 , 47 , 337–347. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arai, H.; Maeda, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Naito, T.; Konishi, M.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, W.T.; Chalermsri, C.; Chen, W.; Chew, J.; et al. Diagnosis and outcomes of cachexia in Asia: Working Consensus Report from the Asian Working Group for Cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023 , 14 , 1949–1958. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Pandey, S.; Bradley, L.; Del Fabbro, E. Updates in Cancer Cachexia: Clinical Management and Pharmacologic Interventions. Cancers 2024 , 16 , 1696. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bertocchi, E.; Frigo, F.; Buonaccorso, L.; Venturelli, F.; Bassi, M.C.; Tanzi, S. Cancer cachexia: A scoping review on non-pharmacological interventions. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024 , 11 , 100438. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sakaguchi, T.; Maeda, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Mizuno, A.; Kato, R.; Ishida, Y.; Ueshima, J.; Shimizu, A.; Amano, K.; Mori, N. Validity of the diagnostic criteria from the Asian Working Group for Cachexia in advanced cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024 , 15 , 370–379. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Zhang, F.M.; Zhuang, C.L.; Dong, Q.T.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Shen, X.; Wang, S.L. Characteristics and prognostic impact of cancer cachexia defined by the Asian Working Group for Cachexia consensus in patients with curable gastric cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2024 , 43 , 1524–1531. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ida, S.; Imataka, K.; Morii, S.; Katsuki, K.; Murata, K. Frequency and Overlap of Cachexia, Malnutrition, and Sarcopenia in Elderly Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Study Using AWGC, GLIM, and AWGS2019. Nutrients 2024 , 16 , 236. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yoshikoshi, S.; Imamura, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Harada, M.; Osada, S.; Matsuzawa, R.; Matsunaga, A. Prevalence and relevance of cachexia as diagnosed by two different definitions in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A retrospective and exploratory study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024 , 124 , 105447. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arends, J.; Strasser, F.; Gonella, S.; Solheim, T.S.; Madeddu, C.; Ravasco, P.; Buonaccorso, L.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Baldwin, C.; Chasen, M.; et al. Cancer cachexia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open 2021 , 6 , 100092. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Buccheri, E.; Dell’Aquila, D.; Russo, M.; Chiaramonte, R.; Vecchio, M. Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass in Older Adults Can Be Estimated with a Simple Equation Using a Few Zero-Cost Variables. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2024 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huang, L.; Shu, X.; Ge, N.; Gao, L.; Xu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yue, J.; Wu, C. The accuracy of screening instruments for sarcopenia: A diagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2023 , 52 , afad152. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Kakehi, S.; Mizuno, S.; Kinoshita, T.; Toga, S.; Ohtsu, M.; Nishioka, S.; Momosaki, R. Prevalence and prognosis of cachexia according to the Asian Working Group for Cachexia criteria in sarcopenic dysphagia: A retrospective cohort study. Nutrition 2024 , 122 , 112385. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Yamanaka, M.; Wakabayashi, H.; Nishioka, S.; Momosaki, R. Malnutrition and cachexia may affect death but not functional improvement in patients with sarcopenic dysphagia. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024 , 15 , 777–785. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mizuno, S.; Wakabayashi, H.; Fujishima, I.; Kishima, M.; Itoda, M.; Yamakawa, M.; Wada, F.; Kato, R.; Furiya, Y.; Nishioka, S.; et al. Construction and Quality Evaluation of the Japanese Sarcopenic Dysphagia Database. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021 , 25 , 926–932. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Miyai, I.; Sonoda, S.; Nagai, S.; Takayama, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Kakehi, A.; Kurihara, M.; Ishikawa, M. Results of new policies for inpatient rehabilitation coverage in Japan. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2011 , 25 , 540–547. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fujishima, I.; Fujiu-Kurachi, M.; Arai, H.; Hyodo, M.; Kagaya, H.; Maeda, K.; Mori, T.; Nishioka, S.; Oshima, F.; Ogawa, S.; et al. Sarcopenia and dysphagia: Position paper by four professional organizations. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019 , 19 , 91–97. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mori, T.; Fujishima, I.; Wakabayashi, H.; Oshima, F.; Itoda, M.; Kunieda, K.; Kayashita, J.; Nishioka, S.; Sonoda, A.; Kuroda, Y.; et al. Development, reliability, and validity of a diagnostic algorithm for sarcopenic dysphagia. JCSM Clin. Rep. 2017 , 2 , 1–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Chou, M.Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020 , 21 , 300–307.e2. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Maeda, K.; Akagi, J. Decreased tongue pressure is associated with sarcopenia and sarcopenic dysphagia in the elderly. Dysphagia 2015 , 30 , 80–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kunieda, K.; Ohno, T.; Fujishima, I.; Hojo, K.; Morita, T. Reliability and validity of a tool to measure the severity of dysphagia: The Food Intake LEVEL Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013 , 46 , 201–206. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shah, S.; Vanclay, F.; Cooper, B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989 , 42 , 703–709. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 2019 , 38 , 1–9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ueshima, J.; Inoue, T.; Saino, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Murotani, K.; Mori, N.; Maeda, K. Diagnosis and prevalence of cachexia in Asians: A scoping review. Nutrition 2024 , 119 , 112301. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Zhong, X.; Zimmers, T.A. Sex Differences in Cancer Cachexia. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2020 , 18 , 646–654. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Geppert, J.; Rohm, M. Cancer cachexia: Biomarkers and the influence of age. Mol. Oncol. 2024 , 1–17. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Permuth, J.B.; Park, M.A.; Chen, D.T.; Basinski, T.; Powers, B.D.; Gwede, C.K.; Dezsi, K.B.; Gomez, M.; Vyas, S.L.; Biachi, T.; et al. Leveraging real-world data to predict cancer cachexia stage, quality of life, and survival in a racially and ethnically diverse multi-institutional cohort of treatment-naïve patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024 , 14 , 1362244. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Han, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Tang, M.; Xu, J.; Tan, S.; Wu, G. Prognostic value of body composition in patients with digestive tract cancers: A prospective cohort study of 8267 adults from China. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024 , 62 , 192–198. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rosa-Caldwell, M.E.; Greene, N.P. Muscle metabolism and atrophy: Let’s talk about sex. Biol. Sex Differ. 2019 , 10 , 43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhong, X.; Narasimhan, A.; Silverman, L.M.; Young, A.R.; Shahda, S.; Liu, S.; Wan, J.; Liu, Y.; Koniaris, L.G.; Zimmers, T.A. Sex specificity of pancreatic cancer cachexia phenotypes, mechanisms, and treatment in mice and humans: Role of Activin. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022 , 13 , 2146–2161. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bonomi, P.D.; Crawford, J.; Dunne, R.F.; Roeland, E.J.; Smoyer, K.E.; Siddiqui, M.K.; McRae, T.D.; Rossulek, M.I.; Revkin, J.H.; Tarasenko, L.C. Mortality burden of pre-treatment weight loss in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024 , 15 , 1226–1239. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Amano, K.; Okamura, S.; Baracos, V.E.; Mori, N.; Sakaguchi, T.; Uneno, Y.; Hiratsuka, Y.; Hamano, J.; Miura, T.; Ishiki, H.; et al. Impacts of fluid retention on prognostic abilities of cachexia diagnostic criteria in cancer patients with refractory cachexia. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024 , 60 , 373–381. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Papadopoulou, S.K.; Tsintavis, P.; Potsaki, P.; Papandreou, D. Differences in the Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling, Nursing Home and Hospitalized Individuals. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020 , 24 , 83–90. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Churilov, I.; Churilov, L.; MacIsaac, R.J.; Ekinci, E.I. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of sarcopenia in post acute inpatient rehabilitation. Osteoporos. Int. 2018 , 29 , 805–812. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Wan, S.N.; Thiam, C.N.; Ang, Q.X.; Engkasan, J.; Ong, T. Incident sarcopenia in hospitalized older people: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023 , 18 , e0289379. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C.; Ho, F.K. Frailty, sarcopenia, cachexia and malnutrition as comorbid conditions and their associations with mortality: A prospective study from UK Biobank. J. Public Health 2022 , 44 , e172–e180. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Wakabayashi, H. Hospital-associated sarcopenia, acute sarcopenia, and iatrogenic sarcopenia: Prevention of sarcopenia during hospitalization. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2023 , 24 , 146–147. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liposits, G.; Singhal, S.; Krok-Schoen, J.L. Interventions to improve nutritional status for older patients with cancer—A holistic approach is needed. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2023 , 17 , 15–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Agostini, D.; Gervasi, M.; Ferrini, F.; Bartolacci, A.; Stranieri, A.; Piccoli, G.; Barbieri, E.; Sestili, P.; Patti, A.; Stocchi, V.; et al. An Integrated Approach to Skeletal Muscle Health in Aging. Nutrients 2023 , 15 , 1802. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mititelu, M.; Licu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Călin, M.F.; Matei, S.R.; Scafa-Udriște, A.; Stanciu, T.I.; Busnatu, Ș.; Olteanu, G.; Măru, N.; et al. An Assessment of Behavioral Risk Factors in Oncology Patients. Nutrients 2024 , 16 , 2527. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mangano, G.R.A.; Avola, M.; Blatti, C.; Caldaci, A.; Sapienza, M.; Chiaramonte, R.; Vecchio, M.; Pavone, V.; Testa, G. Non-Adherence to Anti-Osteoporosis Medication: Factors Influencing and Strategies to Overcome It. A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022 , 12 , 14. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Finch, A.; Benham, A. Patient attitudes and experiences towards exercise during oncological treatment. A qualitative systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2024 , 32 , 509. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gautam, P.; Shankar, A. Management of cancer cachexia towards optimizing care delivery and patient outcomes. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023 , 10 , 100322. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Park, M.A.; Whelan, C.J.; Ahmed, S.; Boeringer, T.; Brown, J.; Crowder, S.L.; Gage, K.; Gregg, C.; Jeong, D.K.; Jim, H.S.L.; et al. Defining and Addressing Research Priorities in Cancer Cachexia through Transdisciplinary Collaboration. Cancers 2024 , 16 , 2364. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Cheung, C.; Boocock, E.; Grande, A.J.; Maddocks, M. Exercise-based interventions for cancer cachexia: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023 , 10 , 100335. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Slee, A.; Reid, J. Exercise and nutrition interventions for renal cachexia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2024 , 27 , 219–225. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Meza-Valderrama, D.; Marco, E.; Dávalos-Yerovi, V.; Muns, M.D.; Tejero-Sánchez, M.; Duarte, E.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, D. Sarcopenia, Malnutrition, and Cachexia: Adapting Definitions and Terminology of Nutritional Disorders in Older People with Cancer. Nutrients 2021 , 13 , 761. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Aprile, G.; Basile, D.; Giaretta, R.; Schiavo, G.; La Verde, N.; Corradi, E.; Monge, T.; Agustoni, F.; Stragliotto, S. The Clinical Value of Nutritional Care before and during Active Cancer Treatment. Nutrients 2021 , 13 , 1196. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Total n = 175 | Cachexia (+) n = 30 | Cachexia (−) n = 145 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD * | 77 ± 11 | 78 ± 9 | 77 ± 11 | 0.437 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.103 | |||

| Men | 103 (59%) | 22 (73%) | 81 (56%) | |

| Women | 72 (41%) | 8 (27%) | 64 (44%) | |

| Setting, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Acute care hospitals | 78 (45%) | 23 (77%) | 55 (38%) | |

| Rehabilitation hospitals | 76 (43%) | 4 (13%) | 72 (50%) | |

| Others | 21 (12%) | 3 (10%) | 18 (12%) | |

| Main causative diseases of dysphagia, n (%) | ||||

| Cerebral infarction | 77 (44%) | 9 (30%) | 68 (47%) | 0.113 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 19 (11%) | 2 (7%) | 17 (12%) | 0.536 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 9 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (6%) | 0.361 |

| Parkinsonism | 15 (9%) | 5 (17%) | 10 (7%) | 0.142 |

| Dementia | 12 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 9 (6%) | 0.435 |

| Cancer | 8 (5%) | 7 (23%) | 1 (1%) | <0.001 |

| Others | 35 (20%) | 4 (13%) | 31 (21%) | 0.453 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic heart failure | 21 (12%) | 9 (30%) | 12 (8%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 13 (7%) | 15 (50%) | 8 (6%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 8 (5%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (3%) | 0.139 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8 (5%) | 4 (13%) | 4 (3%) | 0.030 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Progressive worsening or uncontrolled chronic infections | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Chronic liver failure | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Rheumatoid arthritis and other collagen diseases | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Sarcopenia, n (%) | 133 (76%) | 26 (87%) | 107 (74%) | 0.133 |

| Malnutrition, n (%) | 92 (53%) | 19 (63%) | 73 (50%) | 0.181 |

| Body mass index, kg/m , mean ± SD * | 21.0 ± 4.0 | 18.9 ± 3.0 | 21.4 ± 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Body weight change in 6 months, %, median (IQR **) | 3.3 (−1.9, 12.7) | 11.0 (3.3, 19.7) | 1.5 (−3.5, 10.5) | 0.074 |

| Handgrip strength, kg, mean ± SD * | 16.5 ± 10.9 | 15.2 ± 10.2 | 16.8 ± 11.1 | 0.467 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL, median (IQR **) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.9) | 3.4 (0.8, 11.6) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.0) | <0.001 |

| FILS *** initial, median (IQR **) | 7 (1, 7) | 2 (1, 7) | 7 (1, 7) | 0.160 |

| FILS follow-up, median (IQR **) | 8 (7, 8) | 7 (5.5, 8) | 8 (7, 8) | 0.585 |

| Barthel Index initial, median (IQR **) | 25 (10, 50) | 25 (5, 67.5) | 30 (10, 50) | 0.406 |

| Barthel Index follow-up, median (IQR **) | 50 (20, 85) | 35 (12.5, 75) | 50 (20, 85) | 0.469 |

| Death, n (%) | 7 (4%) | 5 (17%) | 2 (1%) | 0.002 |

| No | Sex | Causative Disease of Admission | Cause of Death | Sarcopenia | Malnutrition | Cachexia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Woman | Urinary tract infection | Senility | + | + | + |

| 2 | Man | Gastric cancer | Systemic metastatic cancer | + | − | + |

| 3 | Man | Colorectal cancer | Colorectal cancer | + | + | + |

| 4 | Man | Urinary tract infection | Pyothorax | + | + | + |

| 5 | Man | Cardiogenic cerebral embolism | Unknown | + | + | + |

| 6 | Woman | Cerebral infarction | Stroke | + | + | − |

| 7 | Woman | Multiple system atrophy | Septic shock | + | + | − |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Kakehi, S.; Wakabayashi, H.; Nagai, T.; Nishioka, S.; Isono, E.; Otsuka, Y.; Ninomiya, J.; Momosaki, R. The Prevalence and Prognosis of Cachexia in Patients with Non-Sarcopenic Dysphagia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2024 , 16 , 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172917

Kakehi S, Wakabayashi H, Nagai T, Nishioka S, Isono E, Otsuka Y, Ninomiya J, Momosaki R. The Prevalence and Prognosis of Cachexia in Patients with Non-Sarcopenic Dysphagia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Nutrients . 2024; 16(17):2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172917

Kakehi, Shingo, Hidetaka Wakabayashi, Takako Nagai, Shinta Nishioka, Eri Isono, Yukiko Otsuka, Junki Ninomiya, and Ryo Momosaki. 2024. "The Prevalence and Prognosis of Cachexia in Patients with Non-Sarcopenic Dysphagia: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Nutrients 16, no. 17: 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172917

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- Advertise with us

- Wednesday, September 04, 2024

Most Widely Read Newspaper

PunchNG Menu:

- Special Features

- Sex & Relationship

ID) . '?utm_source=news-flash&utm_medium=web"> Download Punch Lite App

Gombe extends palliative distribution to security agencies

Kindly share this story:

- Northern govs vow to tackle insecurity

- Gombe to inaugurate medical emergency agency

- Gombe gov charges promoted police officers on dedication

- Haruna Abdullahi

- Joshua Danmalam

- Muhammadu Yahaya

All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from PUNCH.

Contact: [email protected]

Stay informed and ahead of the curve! Follow The Punch Newspaper on WhatsApp for real-time updates, breaking news, and exclusive content. Don't miss a headline – join now!

VERIFIED NEWS: As a Nigerian, you can earn US Dollars with REGULAR domains, buy for as low as $24, resell for up to $1000. Earn $15,000 monthly. Click here to start.

Latest News

Emir sanusi seeks fg’s mandate to resolve fulani crisis, paralympics: ogunleke nigeria’s last table tennis hope, court remands ‘whistleblower’ pidom in kuje prison, knocks for s’africa over junior d’tigers visa denial, abure, loyalists to boycott otti’s stakeholders’ meeting today.

Hunger protest: Wanted Briton alleges invasion, police quiz staff

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, conse adipiscing elit.

- Subscriptions

- Advanced search

Advanced Search

Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. For many patients, maximal therapy for COPD produces only modest or incomplete relief of disabling symptoms and these symptoms result in a significantly reduced quality of life.

Despite the high morbidity and mortality associated with severe COPD, many patients receive inadequate palliative care. There are several reasons for this. First, patient–physician communication about palliative and end-of-life care is infrequent and often of poor quality. Secondly, the uncertainty in predicting prognosis for patients with COPD makes communication about end-of-life care more difficult. Consequently, patients and their families frequently do not understand that severe COPD is often a progressive and terminal illness.

The purpose of the present review is to summarise recent research regarding palliative and end-of-life care for patients with COPD. Recent studies provide insight and guidance into ways to improve communication about end-of-life care and thereby improve the quality of palliative and end-of-life care the patients receive. Two areas that may influence the quality of care are also highlighted: 1) the role of anxiety and depression, common problems for patients with COPD; and 2) the importance of advance care planning.

Improving communication represents an important opportunity for the improvement of the quality of palliative and end-of-life care received by these patients.

- Chronic bronchitis

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- communication

- end-of-life care

- palliative care

SERIES “COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT OF END-STAGE COPD”

Edited by N. Ambrosino and R. Goldstein

Number 6 in this Series

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of mortality and the 12th leading cause of disability worldwide 1 , 2 . By the year 2020, COPD will be the third leading cause of mortality and the fifth leading cause of disability worldwide 3 – 5 . For many patients, maximal therapy for COPD produces only modest relief of symptoms, leaving patients with significantly reduced health-related quality of life. Many patients with COPD receive inadequate palliative care. The purpose of the present review is to examine problems in the delivery of high-quality palliative care to patients with severe COPD and to identify ways in which to address these problems. Since other articles in the series have discussed treatment of dyspnoea and other symptoms and improving quality of life, the current review will focus on communication about palliative and end-of-life care.

- THE DEFINITION OF PALLIATIVE AND END-OF-LIFE CARE

The goal of palliative care is to prevent and relieve suffering and to support the best possible quality of life for patients and their families, regardless of the stage of disease or the need for other therapies 6 . The World Health Organization adopted the following definition of palliative care: “Palliative care means patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social and spiritual needs and to facilitate patient autonomy, access to information and choice” 7 . As such, palliative care expands traditional treatment goals to include: enhancing quality of life; helping with medical decision making and identifying the goals of care; addressing the needs of family and other informal caregivers; and providing opportunities for personal growth 6 . In contrast, the term “end-of-life care” usually refers to care concerning the final stage of life and focuses on care of the dying person and their family. The time period for end-of-life care is arbitrary and should be considered variable depending on the patient's trajectory of illness 8 , 9 . Using these definitions, palliative care includes end-of-life care, but is broader and also includes care focused on improving quality of life and minimising symptoms before the end-of-life period, as depicted in figure 1 ⇓ . Although end-of-life care usually refers to care in the final months, weeks or days, there is growing evidence that communication with patients and families about their preferences for end-of-life care should occur early in the course of a chronic life-limiting illness, in order to facilitate high-quality palliative and end-of-life care. The present review will summarise some of this evidence, particularly as it pertains to patients with severe COPD.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Schematic diagram for use of the terms “palliative care” and “end-of-life care”.

- POOR PALLIATIVE CARE IN COPD AND THE LINK TO POOR COMMUNICATION

The Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Treatments (SUPPORT) enrolled seriously ill, hospitalised patients in one of five hospitals in the USA with one of nine life-limiting illnesses, including COPD 10 . Compared with patients with lung cancer, patients with COPD were much more likely to die in the intensive care unit (ICU), on mechanical ventilation, and with dyspnoea 11 . These differences occurred despite most patients with COPD preferring treatment focused on comfort rather than on prolonging life. In fact, SUPPORT found that patients with lung cancer and patients with COPD were equally likely to prefer not to be intubated and not to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), yet patients with COPD were much more likely to receive these therapies 11 . A study in the UK also found that patients with COPD are much less likely to die at home and to receive palliative care services than patients with lung cancer 12 . Additional studies have documented the poor quality of palliative care and significant burden of symptoms among patients with COPD 13 . Healthcare for these patients is often initiated in response to acute exacerbations rather than being initiated proactively based on a previously developed plan for managing their disease 14 . A recent study of patients with COPD or lung cancer in the US Veterans Affairs Health System also found that patients with COPD were much more likely to be admitted to an ICU, and have greater lengths of stay in the ICU during their terminal hospitalisation, than patients with lung cancer. In the same study, significant geographic variation in ICU utilisation was found for patients with COPD 15 . Although variation in care may be influenced by many factors including availability, access and reimbursement issues, such geographic variation suggests a lack of consensus concerning the best approach to palliative and end-of-life care for patients with COPD. In summary, there are important opportunities for research and quality improvement if better palliative and end-of-life care is to be provided for patients with severe COPD.

- CHALLENGES IN PROGNOSTICATION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH COPD

In COPD, it may be difficult to identify those patients who are likely to die within 6 months. The prognostic models used in SUPPORT, which were based on the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, documented this difficulty. These models showed that, at 5 days prior to death, patients with lung cancer were predicted to have <10% chance of surviving for 6 months, while patients with COPD were predicted to have >50% chance 11 . Recent efforts to identify disease-specific prognostic models for patients with COPD do improve prognostic accuracy, but do not predict individual short-term survival as well as can be done for many patients with cancer 16 – 18 .