Understanding the Constructive and Destructive Natures of Nationalism

Nationalism can unify diverse societies. But when taken to extremes, it can also fuel violence, division, and global disorder.

A man rides his bicycle past volunteers of the Hindu nationalist organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) taking part in the "Path-Sanchalan", or Route March, during celebrations to mark the Vijaya Dashmi or Dussehra in Mumbai, India, on October 11, 2016.

Source: Shailesh Andrade/Reuters

Countries are the building blocks of the modern world. Nearly two hundred make up the globe today. They vary in population and size: China and India are home to more than one billion people. Meanwhile, Vatican City and Monaco are smaller than a single square mile.

The world also comprises a large number of nations.

While the terms country and nation are often used interchangeably, they have subtle, but important, differences. Nations are groups of people united by ethnic, linguistic, geographic, or other common characteristics. Countries, on the other hand, refer to places with governments that are internationally recognized and have the power to oversee what happens within their borders.

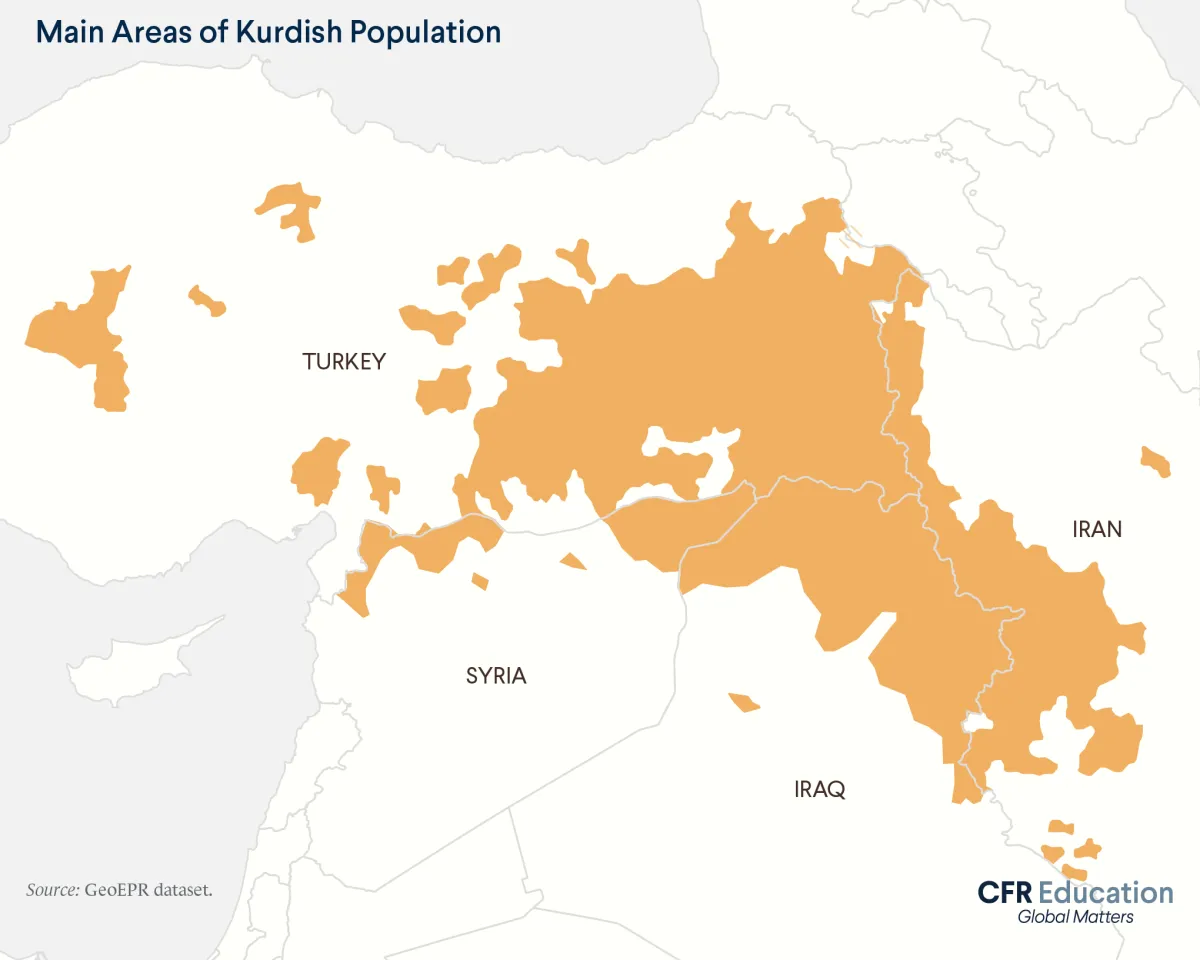

Like countries, nations come in different shapes and sizes. But unlike countries, nations are not always reflected in borders on a map. Some nations span multiple countries, such as the Kurdish nation , whose approximately thirty million people live in Armenia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. The Kurds, importantly, do not have a country of their own and are a minority in all the countries that they inhabit.

Source: GeoEPR dataset.

Other nations exist primarily within one country. Belgium, for example, is largely made up of two different groups of people—the Flemings and Walloons—which have distinct languages and cultural identities. Few members of these two nations live outside Belgium. Sometimes, a nation neatly overlaps with the borders of a country. For example, in Japan, 98 percent of citizens are of the same ethnicity and nearly all speak Japanese and share national traditions.

Groups of people working to advance the interests of their nation, country, or would-be country is known as nationalism . Often, nationalism is invoked by groups pushing for independence, especially when they are ruled by perceived outsiders. But nationalism doesn’t always mean being pro-independence. It can also entail people promoting their culture, asserting their religious beliefs, or organizing for greater political power.

In certain contexts, nationalism can serve as a basis for unity, inclusion, and social cohesion for a country. But when taken to extremes, nationalism can fuel violence, division, and global disorder.

When is nationalism positive?

Rarely do all people in a country look, speak, and pray the same way. Even in Japan—one of the world’s most homogeneous societies—more than two million citizens are ethnic minorities.

In reality, most countries comprise a diverse tapestry of unique identities. When that’s the case, how do countries create a common national identity amid so many internal differences? Let’s take a look at Indonesia.

The sprawling southeast Asian archipelago has around six thousand inhabited islands. It’s the world’s fourth most populous country. Indonesia has more than 260 million citizens who speak over seven hundred languages and practice a half dozen official religions. Its existence today as one country is the result of three centuries of colonization, during which mostly European empires drew borders. These colonial boundaries had little regard for any national, economic, or internal political criteria.

So how has Indonesia stuck together since gaining independence, and what does it now mean to be Indonesian?

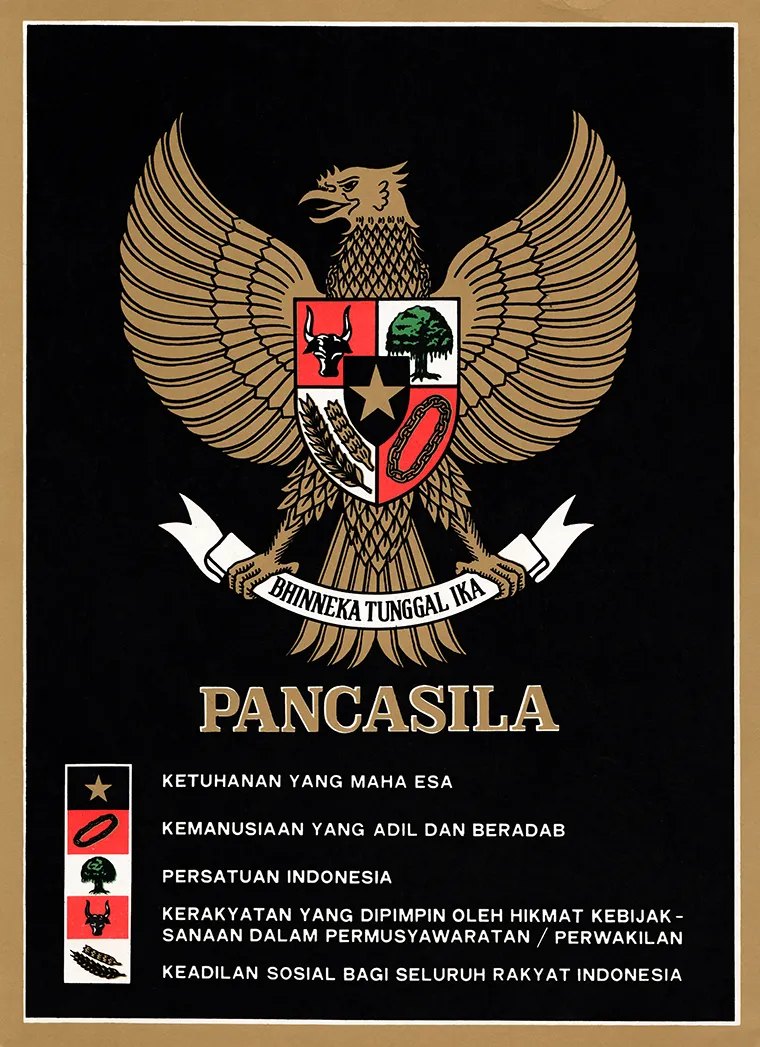

Rather than build a national identity based on geography, language, religion, or ethnicity, Indonesia’s founding father, Sukarno, forged one through ideas. In 1945, just weeks before his country achieved independence, Sukarno laid out a vision known as Pancasila —meaning Five Principles—for an Indonesian identity. This philosophy was intended to unite the diverse and soon-to-be independent country. An iteration of Sukarno’s Pancasila would ultimately appear in the preamble of the country’s constitution. To be Indonesian meant adhering to the following:

- belief in the One and Only God

- just and civilized humanity

- the unity of Indonesia

- democratic rule that is guided by the strength of wisdom resulting from deliberation/representation

- social justice for all the people of Indonesia

An Indonesian government poster showcasing “Pancasila,” the political philosophy on which Indonesia was founded. The five principles of pancasila are a belief in God, a just and civilized humanity, unity of Indonesia, democracy led by collective wisdom, and social justice for all Indonesians.

Source: Government of Indonesia

Pancasila is an example of how a belief in shared ideas and values can unify diverse groups of people. It encourages social cohesion and contributes to pride in one’s country, often referred to as patriotism. Moreover, national identities built solely around characteristics like ethnicity, language, or religion exclude those who do not meet these narrow criteria. As a result, a national identity based on ideas (as well as shared history and common experience) is more accepting.

Throughout the world, liberal countries build unity around common ideas such as freedom and equality. Like Pancasila, liberal principles are often enshrined in countries’ laws and constitutions.

But just because a country lays out a vision for one, all-inclusive national identity doesn’t mean that its citizens are always treated equally. In Indonesia, people have been imprisoned for not adhering to one of the country’s six official religions. And in the United States—a country that prides itself on its diversity—discrimination is still a major issue. This issue was especially evident during the countrywide protests for social justice and against police violence targeting Black Americans following the death of George Floyd .

When is nationalism negative?

Like ideologies or technology, nationalism can be a positive or a negative force. Narrow or aggressive forms of nationalism can be highly divisive. Such nationalism calls for advancing the interests of one group above all else—even at the expense of others. Extreme nationalism is illiberal and intolerant. It doesn’t accept those outside the narrowly defined nation as equal. This “us versus them” mentality, often rooted in ideas of racial and national superiority, can lead to dangerous and violent ends.

What are some instances in which nationalism fuels conflict and global disorder?

Extreme nationalism (hyper-patriotism) : Aggressively advancing one country’s or nation’s interests can have consequences that reverberate around the world.

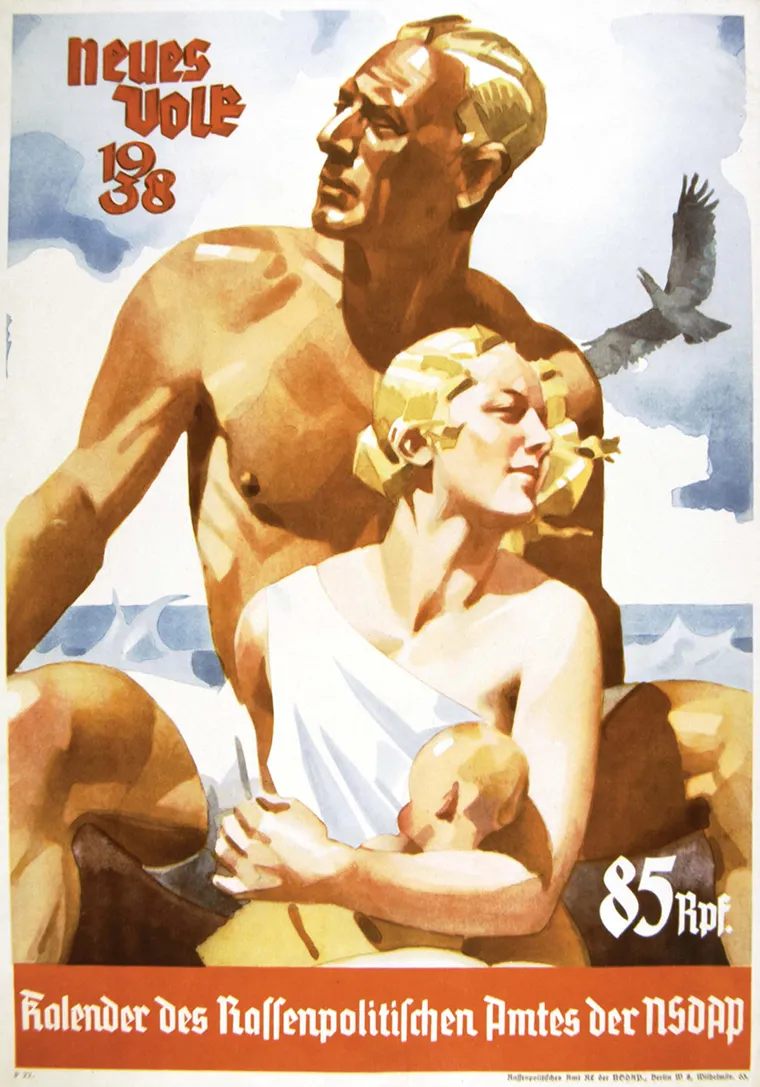

Such strident nationalism precipitated World War I. Shortly thereafter, the world witnessed perhaps the most dramatic example of extreme nationalism fueling global disorder: Nazi Germany. There, a belief in Aryan (essentially white Germanic) racial superiority—a manifestation of what is known as ethnocentric nationalism—led to World War II. Extreme Nationalism unleashed the deadliest conflict in human history, which included horrific campaigns of identity-based violence. Particularly, the Nazi government perpetrated the Holocaust, a systematic killing of over six million Jews.

A propaganda image depicting an idealized “Aryan” family, from the Nazi Party’s Racial Policy Office calendar during the Holocaust, circa 1938.

Source: Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe/U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

Since the end of World War II, European leaders have sought to promote regional security and prosperity over solely national interests by binding countries together through political and economic institutions like the European Union (EU). But recently, a rising tide of nationalism has led countries to once again question such partnerships. Most notably, nationalism fueled the United Kingdom’s decision in 2016, known as Brexit , to leave the EU.

A propaganda poster using an image of immigrants and refugees to advocate for the United Kingdom’s exit from the EU (Brexit), shared by Nigel Farage of the United Kingdom Independence Party in 2016, via Twitter.

Source: UK Independence Party via Twitter

Elsewhere in Europe, identity and exclusive nationalism have led to an aggressive foreign policy that threatens world order. For instance, the Russian government has pursued a multi-year campaign to occupy land in the neighboring nation of Ukraine, partially under claims about its support for ethnic Russians living in the country. However, such justifications are undermined by at least one poll showing that the majority of ethnic Russians in Ukraine oppose Russia's land grab.

Source: Institute for the Study of War; American Enterprise Institute.

Exclusive nationalism : This is the idea that only people who meet certain criteria are citizens and those who are not part of this group can never be equal. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, Islam is the official religion, and non-Muslims cannot become citizens. Even then, not all Saudi Muslims are treated equally. In the majority-Sunni society, adherents of Shia and other minority denominations face prejudice.

Strict definitions of who is and is not part of the nation can lead to economic and political discrimination or even violence as governments attempt to forcibly assimilate minority groups.

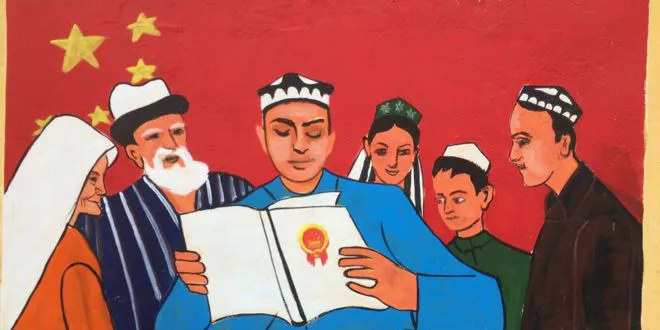

In China, the government has forced over one million Uighur Muslims into detention centers , where detainees are made to learn Mandarin, renounce Islam, and pledge loyalty to the Chinese government.

A propaganda mural painted next to a mosque in the western Chinese province of Xinjiang, where internment camps for Uighur and other Muslim minorities facing religions persecution are located.

Source: Courtesy of BBC News

In Iran, minorities often face government persecution; for instance, Baha’is—adherents of a small religious group—are barred from attending universities. In India, Hindu nationalists, who have gained power in recent years, reject the country’s founding vision as a secular, multicultural society. They have increasingly advocated for preferential treatment for Hindus. At this times this has come at the expense of the rights of some two hundred million Muslim Indians.

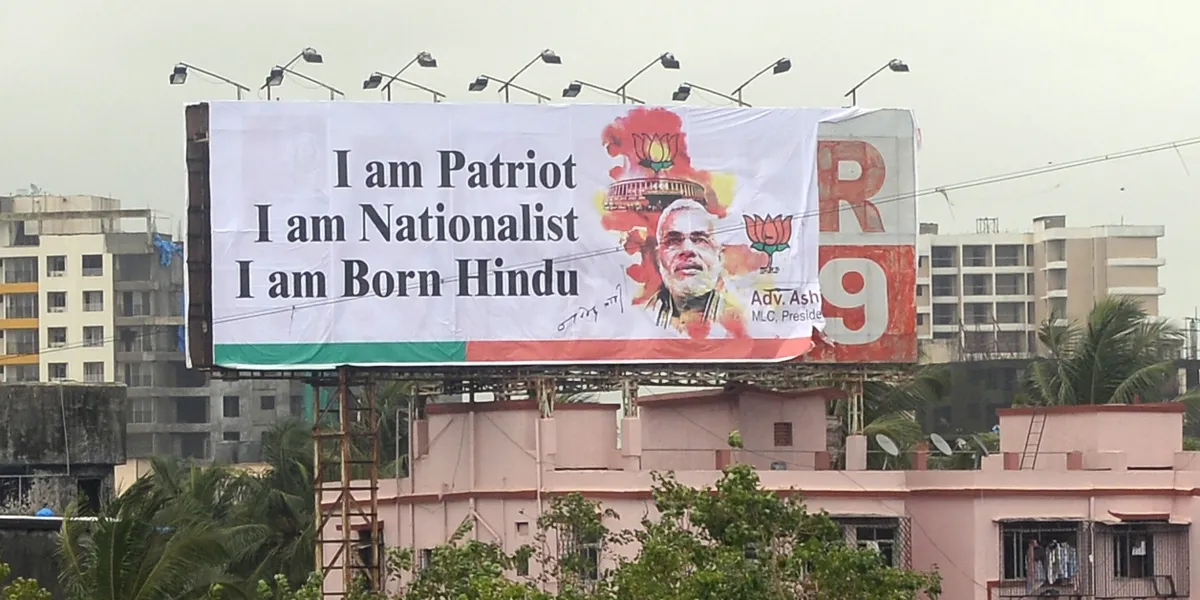

A political advertisement ahead of India’s 2014 elections depicts Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose platform is based on Hindu nationalism, the idea that Hindu faith and culture should shape the diverse country’s politics.

Source: Indranil Mukherjee/AFP via Getty Images

In the most extreme cases, nationalism has led to genocide , the targeted mass killing of a specific group of people. In the predominantly Buddhist Myanmar, Muslim Rohingya have faced decades of persecution . Tensions spiked in 2017 when the government carried out a violent and brutal campaign against the ethnic Muslim minority. This violence forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee into neighboring Bangladesh.

Protesters hold signs objecting to the word "Rohingya" as an aid ship headed for Rohingya refugee camps docks in Myanmar in 2017. The Rohingya are a marginalized Muslim ethnic group, who have been denied citizenship and subjected to ethnic cleansing in Myanmar.

Source: Lauren DeCicca/Getty Images

Economic nationalism : This form of nationalism promotes domestic control of the economy, usually to protect jobs and minimize imports. Economic nationalists also tend to oppose free international trade. To shore up local industries against foreign competition, governments often implement protectionist policies , including tariffs , subsidies, and import quotas.

On the surface, a policy that purports to put the nation’s economic interests first seems fine. However, such policies can actually hurt that country’s citizens. Tariffs increase the prices of imported goods, and consumers must bear the additional cost if the goods are not produced domestically. When one country imposes tariffs on goods from another, it usually faces retaliatory tariffs. These tariffs make it difficult for industries to sell their products at competitive prices abroad.

In today’s global era, international trade is essential. No country is entirely self-sufficient—it cannot rely solely on what it produces within its borders. Whether it’s importing fuel, food, electronics, or face masks during a pandemic , a country needs international trade to function. Some experts even argue that increased trading makes the world a safer place, as countries that are economically interdependent are less likely to go to war.

Nationalism in a Global Era

At the end of World War II, countries sought ways to ensure the world would never again break down into such horrific conflict. Leaders created new global institutions—including the United Nations, World Bank , and International Monetary Fund . These governing bodies form the backbone of what is called the liberal world order. For decades, this liberal world order has tried to guard against the most violent impulses of nationalism. They create forums for international cooperation designed to promote collective security and economic growth. And while certainly not always successful, it has contributed to a largely peaceful and prosperous era for many.

But around the world, nationalism is on the rise again, often along with populism—the movement when large groups of people believe the ruling elites are not addressing their concerns. This combination of sentiments has led to the emergence of new leaders who claim to represent “the people,” alongside efforts to oust existing elites.

Numerous factors account for these developments, including stagnating wages, rising income inequality, and job losses. While such losses in the labor market are mostly associated with technological innovation, they are often attributed to global factors, such as the 2008 global financial crisis , and the COVID-19 pandemic . This is also happening—somewhat paradoxically—as the world grows increasingly interconnected: globalization has enabled people, ideas, money, goods, data, drugs, weapons, greenhouse gasses , viruses, and more to move around the world at unprecedented speeds.

In a time when so much travels across borders so quickly—including today’s greatest threats—the world requires more cooperation. No country can deal successfully with global challenges on its own; countries fare better when they join forces with like-minded partners.

EducationalWave

Pros and Cons of Nationalism

Nationalism can foster unity , pride, and common identity among citizens, promoting social cohesion and inclusivity. It can inspire positive contributions to society, preserve cultural heritage , and strengthen resilience during challenges. However, nationalist sentiments may also lead to negative divisions , conflicts, and marginalization within society. Excluding certain groups and fostering competition can hinder social harmony and diversity. Understanding both the advantages and drawbacks of nationalism is essential for fully grasping its impact on societies and individuals.

Table of Contents

- Fosters unity, pride, and shared identity among citizens.

- Promotes social cohesion and common goals.

- Preserves cultural heritage and traditions.

- Strengthens resilience to overcome challenges.

- Creates negative group divisions and heightens conflicts.

Benefits of Nationalism

Nationalism, when harnessed positively, can foster a sense of unity , pride, and shared identity among citizens within a nation. This shared national identity can create a cohesive society where individuals feel a sense of belonging and loyalty to their country.

Nationalism often serves as a unifying force , bringing together people from diverse backgrounds under a common flag and shared values. It can promote social cohesion by emphasizing common goals, traditions, and cultural heritage that bind citizens together.

Furthermore, nationalism can inspire citizens to work towards the betterment of their nation. When individuals feel a strong sense of national pride , they are more likely to contribute positively to their society, whether through civic engagement, community service, or economic productivity. This collective sense of purpose and responsibility can drive progress and development within a country.

Sense of Identity and Belonging

A strong sense of identity and belonging is often cultivated within a nation through the promotion of nationalism. Nationalism fosters a shared cultural heritage, history, traditions, and values that create a cohesive national identity among its citizens. This sense of identity instills pride in one's nation and strengthens the feeling of belonging to a larger community, fostering unity and a common purpose among individuals.

| Nationalism promotes a feeling of togetherness and solidarity among citizens, fostering cooperation and collaboration. | |

| It helps preserve and celebrate unique cultural practices, languages, and traditions that define the nation's identity. | |

| A strong national identity empowers individuals to contribute positively to their society and work towards common goals. | |

| A shared sense of belonging can strengthen a nation's ability to overcome challenges and adversity collectively. | |

| Nationalism can promote inclusivity by embracing diversity within the national identity, fostering a sense of belonging among all citizens. |

Unity and Patriotism

Fostering a collective spirit of loyalty and devotion towards one's country, unity and patriotism play pivotal roles in shaping a nation's cohesion and strength. Unity, derived from a shared sense of purpose and belonging, binds individuals together under a common identity , transcending differences for the greater good of the nation.

This unity cultivates a sense of solidarity among citizens, promoting cooperation and collaboration towards common goals. Patriotism, on the other hand, fuels a deep love and pride for one's country, instilling a sense of responsibility to contribute positively to its progress and well-being.

Through unity and patriotism, a nation can overcome internal divisions and external threats, standing strong in the face of challenges. These values inspire citizens to work towards the betterment of their country, fostering a spirit of national pride and resilience.

Additionally, unity and patriotism serve as foundations for social harmony , political stability, and economic prosperity, laying the groundwork for a flourishing and resilient nation.

Drawbacks of Nationalism

The drawbacks of nationalism are evident in the negative group divisions it can create within a society, leading to tensions and conflicts among different groups.

Additionally, nationalism has the potential to heighten the chances of conflicts, as it often fosters a sense of superiority and competition between nations.

Lastly, nationalism's tendency to be exclusionary can result in marginalized groups feeling alienated or discriminated against within their own country.

Negative Group Division

One significant consequence of nationalism is the exacerbation of social and ethnic divisions within a country. While nationalism can foster a sense of unity and pride among a specific group of people, it often does so at the expense of creating negative group divisions . This can lead to increased tensions between different ethnic, cultural, or religious groups within a nation.

Nationalism tends to promote an 'us versus them' mentality, where those who do not fit into the dominant national identity are marginalized or discriminated against . This can manifest in various forms, such as discrimination in employment opportunities, unequal access to resources, or even violent conflicts between different groups .

In extreme cases, nationalism can fuel ethnic nationalism , leading to segregation, persecution , or even genocide. Moreover, the emphasis on national identity can overshadow the diversity and richness of multicultural societies, further alienating minority groups.

This can hinder social cohesion , weaken the fabric of society, and impede progress towards equality and inclusivity. Therefore, while nationalism can promote a sense of belonging for some, it often comes at the cost of deepening negative group divisions within a country.

Heightened Conflict Potential

Heightened conflict potential is a prominent drawback associated with nationalist ideologies, often resulting in increased tensions and hostilities between different groups within a nation. This negative consequence can lead to various detrimental effects on society, including:

- Violence : Nationalism has the potential to fuel violent confrontations between groups with differing nationalist views, escalating conflicts to dangerous levels.

- Discrimination : Nationalist ideals sometimes lead to discrimination against minority groups within a nation, fostering inequality and injustice.

- Polarization : Nationalism can polarize communities, creating an 'us versus them' mentality that hinders unity and cooperation.

- Isolation : Excessive nationalism may isolate a country on the global stage, leading to strained international relations and diminishing opportunities for collaboration and progress.

These outcomes highlight the destructive nature of heightened conflict potential associated with nationalist ideologies, emphasizing the importance of fostering unity and understanding among diverse groups within a nation.

Exclusionary Tendencies Displayed

Exhibiting exclusionary tendencies , nationalism often promotes the prioritization of one group's interests over others within a nation. This exclusionary behavior can lead to the marginalization or discrimination of minority groups, ethnicities, or immigrants who do not fit the dominant national identity . Such exclusion can create divisions within society, fostering resentment , animosity , and social unrest. This can further exacerbate existing inequalities and perpetuate prejudices , hindering social cohesion and unity.

Moreover, nationalism's exclusionary tendencies can also manifest in policies that restrict immigration, promote protectionist economic measures , or limit cultural diversity. By favoring one group over others, nationalist ideologies can hinder the integration of diverse perspectives, hindering innovation and progress. This narrow focus on a singular national identity can stifle creativity, limit tolerance, and impede the exchange of ideas essential for societal development.

Divisions and Exclusion

Examining the impact of nationalism on social identity and the challenges it poses to cultural diversity brings to light the inherent divisions and exclusions that can arise within a society.

The emphasis on national identity can sometimes overshadow the diverse backgrounds and beliefs of individuals, leading to a sense of exclusion among minority groups .

As nationalism strengthens a sense of unity among certain groups, it simultaneously creates barriers that can isolate others, potentially hindering inclusivity and understanding.

Social Identity Impact

Nationalism can often lead to the reinforcement of social divisions and the exclusion of certain groups within a society. This impact on social identity can have far-reaching consequences, affecting how individuals perceive themselves and others, as well as shaping the dynamics of a nation.

The following points illustrate the divisive nature of nationalism:

- Loss of Belonging :

Nationalism can create an 'us vs. them' mentality, causing individuals who do not fit the dominant national identity to feel excluded and marginalized.

- Heightened Tensions :

The emphasis on national pride can escalate tensions between different social groups, fueling conflicts and deepening existing divisions.

- Undermining Diversity :

Nationalism often prioritizes a singular national identity, overshadowing the richness of cultural, ethnic, and social diversity present within a society.

- Inequality and Discrimination :

Certain groups may face discrimination or unequal treatment based on their perceived lack of alignment with the nationalist ideology, leading to social injustices and disparities.

Cultural Diversity Challenge

The challenge of cultural diversity within nationalist movements often manifests through divisions and exclusion of minority groups. Nationalism, while promoting a sense of unity and pride in one's nation, can lead to the marginalization of individuals who do not fit the dominant cultural or ethnic group. This exclusionary aspect of nationalism can create tensions and hinder social cohesion within a country.

To further illustrate this point, let's consider the following table showcasing the potential impacts of cultural diversity challenges within nationalist movements:

| Cultural Diversity Challenge | Implications |

|---|---|

| Divisions based on ethnicity | Fragmentation of society |

| Exclusion of minority cultures | Loss of cultural heritage |

| Lack of representation for marginalized groups | Inequality and discrimination |

| Difficulty in fostering a sense of national unity | Social unrest and conflict |

Addressing these challenges requires a delicate balance between promoting national identity and respecting the diversity that exists within a country's population. Failure to navigate this balance can exacerbate divisions and perpetuate exclusionary practices.

Potential for Conflict

Nationalism's propensity to ignite tensions within diverse societies has been a subject of scholarly debate. While nationalism can foster a sense of unity and pride among a group of people, it also carries the potential to spark conflicts that can have far-reaching consequences.

Here are some reasons why nationalism can lead to conflict:

- Us vs. Them Mentality : Nationalism often emphasizes differences between 'us', the nationals, and 'them', those outside the nation, creating an environment of hostility towards perceived outsiders.

- Historical Grievances : Nationalistic sentiments rooted in historical events or territorial disputes can fuel animosity and lead to conflicts between nations or within multicultural societies.

- Xenophobia and Discrimination : Extreme nationalism can breed xenophobia and discriminatory attitudes towards minority groups, escalating tensions and potentially resulting in violence.

- Competing Nationalisms : When multiple nationalist movements exist within a region, each vying for dominance, clashes over cultural identity and political power can erupt, exacerbating conflicts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can nationalism lead to positive globalization?.

Nationalism can potentially foster positive globalization by promoting a sense of national pride and unity that encourages collaboration and cooperation on a global scale. When harnessed constructively, nationalism can contribute to a more interconnected and prosperous world.

How Does Nationalism Impact Cultural Diversity?

Nationalism can impact cultural diversity by promoting a sense of unity and identity within a specific group, potentially leading to the preservation and celebration of unique cultural traditions. Conversely, it may also foster exclusion and conflict with other cultures.

Is Nationalism Compatible With Multicultural Societies?

Nationalism and multicultural societies can present challenges due to potential conflicts between national identity and diverse cultural backgrounds. Balancing pride in one's nation with respect for cultural differences is essential for harmony.

What Role Does Social Media Play in Nationalism?

Social media plays a significant role in shaping nationalist sentiments by providing a platform for amplifying nationalist ideologies, spreading propaganda, and fostering a sense of unity among like-minded individuals, ultimately influencing public opinion and political discourse.

Can Nationalism Promote Economic Growth Sustainably?

Nationalism can potentially promote economic growth sustainably by fostering a sense of unity and pride among citizens, which can lead to increased productivity, innovation, and investment in national industries. However, it also raises concerns about protectionism and global cooperation.

In conclusion, nationalism can provide individuals with a sense of identity and belonging, as well as foster unity and patriotism within a nation.

However, it also has the potential to create divisions and exclusion among different groups, leading to conflicts.

It is important for societies to carefully consider the implications of nationalism and strive to promote unity and inclusivity while recognizing and celebrating cultural diversity .

Related Posts:

- Pros and Cons of Ethnocentrism

- Pros and Cons of Pluralism

- Pros and Cons of Open and Closed Groups

Related posts:

- Pros and Cons of Monarchy

- Pros and Cons of the War of 1812

Educational Wave Team

- Communication

- Recreational

Pros and Cons of Nationalism

- Post author: admin

- Post published: June 22, 2019

- Post category: Government

- Post comments: 0 Comments

Image source: Ekantipur.com

Nationalism is a system created by people who believe their nation is superior to all others. Most often this sense of superiority has its roots in shared ethnicity. Other countries build nationalism around a shared language, religion, and culture or a set of social values.

A nation emphasizes shared symbols, folklore, and mythology. Shared music, literature, and spots may further strengthen Nationalism.

Nationalists work towards a self-governing state. Their government controls aspects of the economy in order to promote the nation’s self-interests. It sets policies that strengthen the domestic entities that own the factors of production.

Here are the 10 pros and cons of Nationalism. If you want to read the short form of 5 Pros and Cons of Nationalism .

1. It develops the infrastructure of the nation . National pride means careering for what is yours. When there is a strong sense of nationalism, then there are programs put in place to care for roads bridges, and other needed infrastructure items.

2. It inspires people to succeed. The American dream is an example of nationalism. The idea that someone can come to the US from anywhere and pursue their own version of happiness or achieve what they want to achieve in life is an effort many wish to have access to.

3. It gives a nation a position of strength . One should always negotiate from a position of strength. A nation can be as strong as it can possibly be as a community and this can give it global negotiating power.

4. Nationalism brings about Patriotism . This is the feeling of love, devotion, a sense of attachment to a homeland, and alliance with others. This is all caused by the nationalism of the citizens in the country.

5. Brings about the duty to the nation above all . If the rights of the nation spring from its obligations, then it is principally from those that relate to itself and above all. This singularity manly brave the adventurous character of the nation.

6. Unity in the group even in diversity. The challenge of achieving unity in diversity even through basic knowledge regarding suitable language or nonverbal is brought by nationalism.

7. Leads to pride in belonging to the nation . As a citizen of the country, nationalism will bring about the pride of being part of the nation or belonging to the nation.

8. Working together for the motherland even when living in a different country . Some of the citizens work together with their country or nation despite being away from their nation this is all caused by nationalism.

9. Working for the all-around development of the nation. Nationalism ensures that the involved participant works all round to the development of the nation.

10. Bring justice and rule of law . Nationalism could bring about justice in a nation and a better rule of law.

1. It often leads to separation and loneliness . Nationalism superiority often causes a country to not only be independent of the rest of the world but also separated from the rest of the world. Treaties can become more difficult to form. It can also become difficult to have a strong export/import market.

2. It can lead to socioeconomic cliques . Nationalism doesn’t occur at the community level. It only occurs at the individual level thus, creating separation among people based on the labels they create on their own.

3. It can lead to war . When two nations focused on nationalism clash in their ideas, both will feel that they are right and the other is wrong. If either feels like their values are under attack, then nationalism can also become the foundation of war.

4. In some cases going to extreme left/right fringes in the name of security of the nation . Extreme fingers caused by nationalism may lead in the name of the secure ring, then the security of the country involved is affected.

5. The intolerance that may lead to hatred . Sometimes creating intolerance for their countries may bring extreme hatred for people of another country.

6. May lead to insults and hurting. One can insult and hurt others’ nationalities, religions,s or social cultures due to nationalism.

7. Have prejudice about others. Prejudice is having an effective feeling for others in the nation. This reasonable feeling or opinion about others is a result of nationalism.

8. One thinks for only one’s nation. In nationalism, one only thinks about his/her own nation without any concern for the country he is actually living in as well as others.

9. Weighing majority and minority concerns . In a nation, nationalism may bring about problems as a result of weighing the majority and the minority concerns.

10. Human abuses of power . Nationalism leads to abuses of power, hence there would be no accountability or any justice in the nation.

You Might Also Like

Pros and cons of constitution

Pros and Cons of Collecting Unemployment

Pros and cons of Versailles treaty

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Nationalism Essay: Topics, Examples, & Tips

A nationalism essay is focused on the idea of devotion and loyalty to one’s country and its sovereignty. In your paper, you can elaborate on its various aspects. For example, you might want to describe the phenomenon’s meaning or compare the types of nationalism. You might also be interested in exploring nationalism examples: in various countries (South Africa, for instance), in international relations, in government, in world history, or even in everyday life.

This article by our custom-writing experts will help you succeed with your assignment. Here, you will find:

- Definitions and comparisons of different types of nationalism;

- A step-by-step nationalism essay writing guide;

- A number of nationalism examples;

- A list of 44 nationalism essay topics.

- 🔝 Top 10 Topics

- ❓ Definition

- ✔️ Pros & Cons

- 📜 Nationalism Essay Structure

- 🌐 44 Nationalism Topics

- 📝 Essay Prompts & Example

- ✏️ Frequent Questions

🔝 Top 10 Nationalism Essay Topics

- Irish nationalism in literature

- Cultural nationalism in India

- Can nationalism promote peace?

- The politics of contested nationalism

- How does religion influence nationalism?

- Does globalization diminish nationalism?

- Does nationalism promote imperialism?

- Nationalism in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- How liberalism leads to economic nationalism

- Link between national identity and civic nationalism

❓ Nationalism Essay: What Is It About?

Nationalism is an idea that a nation’s interests are above those of other countries or individuals. It implies identifying with a nation and promoting its independence. In particular, nationalism ascribes value to a nation’s culture, traditions, religion, language, and territory.

In fact, “nationalism” is a very complicated term. It has many types and gradations that are exciting to explore. Besides, it has a long and varied history. In countries such as India and France nationalism helped to achieve democracy and independence. At the same time, in it extreme forms it led to wars and terrorism. Any of these aspects can be the focus of your nationalism essay.

Types of Nationalism

As we’ve mentioned before, nationalism is a complicated notion. It varies a lot from country to country as well as historically. That’s why scholars proposed a classification of nationalism types. It helps to reflect these differences. Check out some of the most popular forms of nationalism in the list below.

- Cultural nationalism. This type is centered on a nation’s culture and language. In the 1800s, it became a popular idea in Europe and postcolonial states. Cultural nationalism is reflected in the celebration of folklore and local dialects. For example, in Ireland it led to an increased interest in the Gaelic language. We can still find ideas related to this ideology today. A prominent example is Americans’ appreciation of their cultural symbols, such as the flag.

- Civic nationalism. Civic nationalism’s definition is an idea of belonging through common rights. According to this ideology, the interests of a state are more important than those of a single nation. Civic nationalism is based on modern ideas of equality and personal freedom. These values help people achieve common goals. Nowadays, civic nationalism is closely associated with liberal Western countries.

- Ethnic nationalism. This type is focused on common ethnicity and ancestry. According to ethno-nationalists, a country’s homogenous culture allows sovereignty. This ideology is considered controversial due to its association with racism and xenophobia. Ethnic nationalism’s pros and cons can be illustrated by its effects on culture in Germany. On the one hand, it influenced the art of the Romantic era. On the other, its extreme form led to the rise of Nazism.

- Economic nationalism. A simple definition of economic nationalism is the idea that a government should protect its economy from outside influences. It leads to the discouragement of cooperation between countries. Such an approach has its benefits. However, it is often counterproductive. Scholars point out many failures throughout the history of economic nationalism. The Great Depression, for example, was prolonged due to this approach.

- Religious nationalism. The fusion of politics and religion characterizes this ideology. Its proponents argue that religion is an integral part of a national identity. For instance, it helps to unite people. The rise of religious nationalism often occurs in countries that fight for independence. Notable examples are India, Pakistan, and Christian countries like Poland.

The Globalism vs Nationalism Debate

One of the fiercest debates concerning nationalism is focused on how it relates to globalism. These two attitudes are often seen as opposed to each other. Some even call globalism and nationalism “the new political divide.” Let’s see whether this point of view is justified.

Nowadays, communities around the world are becoming more and more homogenous. This unification and interconnectedness is called globalization , while an ideology focused on its promotion is known as globalism.

Naturally, these tendencies have their pros and cons . Want to learn more? Have a look at the table below.

| Globalism | Nationalism | |

|---|---|---|

| 👍 | Is associated with and development. | Is associated with and love for one’s country. |

| 👍️ | Promotes around the world. | Promotes within a nation. |

| 👍 | Values between nations. | Values a , history, and heritage. |

| 👍 | Seeks to solve , such as climate change. | Seeks specific solutions for . |

| 👍 | Encourages between countries. | Encourages companies to produce . |

| 👎 | The unification of cultures makes them increasingly . | Extreme nationalism is linked to . |

| 👎 | Excessive focus on global cooperating can lead to at home. | Excessive focus on one’s home country with nations abroad. |

| 👎 | Advanced communication leads to . | Protection from outside influences . |

As you can see, both notions have their strong and weak aspects. But can globalism and nationalism coexist? In fact, many scholars say “ yes, they can .” Instead of choosing either option, people can combine their best traits. This way, we will promote effective communication and collaboration.

Nationalism vs. Patriotism

You may be wondering: Is nationalism a synonym for patriotism? The answer is that both words denote pride and love for one’s country. However, there is an important distinction to be made. While patriotism has a generally positive meaning, nationalism has a negative one.

The main difference lies in the attitude towards other nations:

- Patriotism doesn’t imply that one’s nation is superior to others. Generally, this term refers to how the state approaches its ideals, values, and culture. In this case, a patriot of a particular country can represent any nation, regardless of their origin.

- In contrast, nationalism implies an idea of a nation’s sovereignty. This means that a country’s interests are viewed separately from the rest of the world. It also focuses on the importance of nation’s culture and ethnicity. In extreme situations, these values may result in an idea of supremacy.

In short, nationalism is patriotism taken to the extreme. With this in mind, let’s have a look at positive and negative effects of nationalism. An essay on any of the following points will surely be a success.

✔️ Nationalism Pros and Cons

If you have to write an essay on “why nationalism is good”, here are some of its key benefits for you to consider:

| ✔️ | Nationalism emphasizes collective identity. This encourages people to strengthen their nation while working together on for the common good. | |

| ✔️ | Have you ever heard about the American Dream? It’s the idea that anyone may come to the United States and achieve what they want. Nationalism inspires people to succeed. | |

| ✔️ | It can be the force that unites people, inspiring them to fight back. It’s especially true for nationalism based on a freedom movement. An example of this phenomenon is India before 1947. | |

| ✔️ | . | Nationalist politics can influence a country’s economy. Protectionism, for example, is a way to restrict imports. Bans, tariffs, and taxes are its popular methods. These efforts often help to drive the local economy. |

| ✔️ | From time to time, each country faces crises. However, the ways in which nations deal with them differ. A nationalist society may overcome these periods more easily. | |

| ✔️ | Nationalist leaders can stabilize a country’s political system. Under a nationalist regime, loyalists fill the top government jobs. It reduces the potential for political quarrels. | |

| ✔️ | The desire for self-government often promotes democratic movements. A prime example of this is the French Revolution. The 2020 protests in Belarus are a more recent case. | |

| ✔️ | Pan-nationalism is a common idea in the and in Africa. Such movements strive to unify similar cultures under one banner. It can also help stabilize the economy. | |

| ✔️ | . | Once a nation has claimed its territory, it needs to build a government. Nationalists often have clear ideas about how to rule a country. Such leaders are interested in the rapid development of crucial state structures. |

| ✔️ | Most nations pride themselves on their culture. Their unique traditions are the foundation of their identities. Protective policies can be a crucial concern for a nationalist government. |

But what about the concept’s drawbacks? After all, nothing can be 100% beneficial. For a credible investigation, it’s necessary to examine both sides of the topic. Here are some disadvantages to consider for a paper on nationalism:

| ❌ | When nationalism becomes aggressive, it can lead to trade restrictions. On the one hand, such policies stimulate the production of goods. On the other hand, trade wars lead to the loss of export markets. | |

| ❌ | Nationalism can lead to the separation of people based on race, ethnicity, religion, wealth, etc. Some examples are racial supremacy in Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. | |

| ❌ | When a community focuses on nationalist ideals, it might develop an idea of supremacy. If they believe their principles and values are under attack, it can even lead to war. Examples include the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014. | |

| ❌ | Many European nations expanded their trade by conquering other countries. This often led to mass genocides and enslavement. Notable imperialists are England, Spain, and the Netherlands. | |

| ❌ | Ultranationalism can go beyond the struggle for a nation’s independence. Often it involves attacking other peoples. It may even result in civil wars. The Israeli-Palestine conflict is a prime example of such warfare. | |

| ❌ | Countries’ nationalist tendencies interfere with their foreign affairs. The events in Europe and the US in 2020 have demonstrated the effects of such policies. | |

| ❌ | . | Nationalism often implies that one ethnicity is superior to others. Its rhetoric includes criticism of other peoples. This way, it appeals to existing stereotypes and exacerbates them. |

| ❌ | A nationalist country would educate children according to the ideology. It especially affects classes such as history or . They can become a platform for spreading dangerous ideas. | |

| ❌ | Unions such as the EU or the WTO make grand promises to their members. However, for smaller countries, membership can be straining. Citizens may want to choose a separate path to protect their economy. The Brexit referendum is an example of this phenomenon. | |

| ❌ | Immigrants’ diverse cultures don’t correlate with nationalists’ values. Such governments often strive to create a homogenous population. They belittle the importance of other cultures and hinder integration. |

As you can see, nationalism can lead both to prosperity and destruction. Now you know why keeping the balance is crucial to a nation’s well-being. Think about it when you write your argumentative essay on nationalism.

📜 Nationalism Essay Structure

Now, let’s take a closer look at the essay structure. When writing your paper on nationalism, follow this outline:

| ✔️ | should emphasize the importance of discussing nationalism. Describing the distinction between a state and a nation is a good start. |

| ✔️ | should express your main claim. For example, if you’re writing about nationalism and patriotism, your thesis should demonstrate your conclusion whether they’re similar or different. |

| ✔️ | by putting forward strong arguments. Historical sources can be of great help. |

| ✔️ | it’s vital to show you’ve understood the term “nationalism”. You will also need to present your position. While writing a conclusion, try to outline and reemphasize your thesis, adding your own thoughts and views on this issue. |

So, was the writing process as hard as you expected? Nationalism essays indeed require a little bit more time and research than other papers. Nonetheless, you can only benefit from this experience.

🌐 Nationalism Essay Topics

Don’t know which nationalism essay topic to choose? Try one of the ideas below:

- How do nationalism and patriotism differ? The former is linked to acquiring territories perceived as the homeland. The latter means taking pride in the nation’s achievements. Scholars sometimes consider patriotism a form of nationalism.

- How does nationalism affect the distribution of the Sars-CoV-2 vaccine? Determine whether the countries with nationalist tendencies are more successful in getting their population vaccinated.

- Nationality politics in the Soviet Union. Under the rule of Stalin, the USSR transformed into a totalitarian state. But before that, Lenin took care to enact extensive ethnicity laws. What happened when Stalin slammed the brakes on the program?

- Perceiving nationalism as bad: why is it common? For many, the word itself evokes negative associations. For a person who considers themselves a liberal, it may seem like a great evil. Where does this perception come from? What benefits does nationalism have for liberals?

- Nationalist ideology and its many categories. In nationalism studies, the main distinction is between its ethnic and civic types. But there are many other categories that you can explore. Use this prompt to give an overview of such concepts.

- Religious nationalism: Crusades vs. Jihad. In the Middle Ages, Christians tried to stop Islam’s expansion via bloody crusades. In modern times, the call to jihad is used to mobilize extremist Muslims. What are the major differences between these types of holy war?

- What role does nationalism play in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict Israel and Palestine have been fighting for decades over what they believe to be a holy land. The dispute appears to be unsolvable. What arguments do both parties bring forth? How does Arab nationalism come into play here?

- The development of nationalism over time . The French Revolution was the result of nationalist thinking. However, what we perceive as nationalist today is different from what it was back then. In your essay, trace the origins and evolution of the term “nationalism” and its meaning.

- Prominent dictators then and now: a comparison. Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco are well-known names. But how do they compare to modern authoritarian leaders? When answering this question, evaluate the role of nationalist ideology.

- What are some political disadvantages of nationalism? Populist leaders are often unpopular with other politicians. Some examples are Poland’s PiS party and Donald Trump. Discuss how a nationalist stance can affect domestic policies.

- Arab nationalism and its influence on the world economy.

- Nationalism vs. liberalism.

- German nationalism and the World Wars.

- Economic nationalism: pros and cons.

- European nationalism in the 20th century.

- Globalism vs. nationalism: how do they differ ?

- Jewish nationalism and its influence on the formation of the Israeli state.

- Relationship between nationalism and religion.

- Nationalism in Orwell’s novels.

- The French Revolution: how nationalism influenced the political system change.

- Is nationalism objectively good or bad?

- Nationalism, transnationalism, and globalism: differences and similarities.

- Russian nationalism in the 21st century and its impact on the world political system.

- Nationalism as a catalyst for war.

- Liberal nationalism and radical nationalism: benefits and disadvantages.

- Evaluate the significance of national identity.

- What is the difference between race and ethnicity?

- How can love of a country positively impact a state’s healthcare system?

- What fueled the rise of nationalism in the post-socialist space?

- Trace the connection between nationalist ideology and morality.

- What countries are considered nationalizing?

- Compare the conflicts where nationalism hinders solution.

- Choose five aspects of neo-nationalism and analyze them.

- Nationalist expressions in art .

- Nationalism in Ukraine: consequences of the Crimean annexation.

- Revolution and nationalism in South America.

- Examine the significance of street names to spread nationalist views.

- Why do people grow attached to a specific territory?

- The political power of nationalist language and propaganda.

- What does the feminist theory say about chauvinism?

- What makes post-colonial nationalism unique?

- Assess the difference between Western and non‐Western nationalism.

- Sex and gender in nationalism.

- Civic and ethnic forms of nationalism: similarities and differences.

📝 Nationalism Examples & Essay Prompts

Want more ideas? Check out these additional essay prompts on some of the crucial nationalism topics!

Nationalism in South Africa Essay Prompt

South African nationalism is a movement aimed at uniting indigenous African peoples and protecting their values. An essay on this topic can consist of the following parts:

- The factors that led to the rise of African nationalism. These include dissatisfaction with colonial oppression, racial discrimination, and poor living conditions.

- Effects of African nationalism. One significant achievement is indigenous peoples regaining their territories. They also improved their status and revived their culture that was distorted by colonialism.

- Conclusion of African nationalism. With time, the struggle for autonomy evolved into an idea of Pan Africanism. This concept refers to the unification of indigenous South African peoples.

Nationalism in India Essay Prompt

Nationalism in 19 th -century India was a reaction against British rule. One of its defining characteristics is the use of non-violent protests. Your essay on this topic may cover the following aspects:

- Mahatma Gandhi and Indian nationalism. Gandhi was a pioneer of non-violent civil disobedience acts. His adherence to equality inspired many human rights activists.

- Cultural nationalism in India. Pride rooted in national heritage, language, and religion played a crucial role in Indian nationalism. One of the most important figures associated with this movement is Bengal poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Nationalism in the Philippines Essay Prompt

Nationalism in the Philippines has a unique chronological pattern. It’s also closely related to the Philippino identity. You can explore these and other aspects in your essay:

- The rise of Filipino nationalism in the 19 th century. Discuss the role of José Rizal and the Propaganda Movement in these events.

- Nationalism and patriotism in the Philippines. Compare the levels of patriotism at different points in the country’s history.

- Is there a lack of nationalism in the Philippines? Studies show that Filipinos have a relatively weak sense of nationhood and patriotism. What is your perspective on this problem?

How Did Nationalism Lead to WWI?: Essay Prompt

Nationalism is widely considered to be one of the leading causes of WWI. Discuss it with the following prompts:

- Militarism and nationalism before WWI. Militarism is a belief in a country’s military superiority. Assess its role in countries such as the British and Russian Empires before the war.

- How did imperialism contribute to WWI? Imperialism refers to a nation’s fight for new territories. It fuelled the rivalry between the world’s leading countries before the war.

- Nationalism in the Balkans and the outbreak of WWI. Write a persuasive essay on the role of the Balkan crisis in Franz Ferdinand’s assassination. How did this event lead to the outbreak of war?

Want to see what a paper on this topic may look like? Check out this nationalism essay example:

| Title | How Did Nationalism Lead to WWI? |

|---|---|

| Introduction | The reasons for the beginning of World War I are argued among historians. At the beginning of the twentieth century, many European countries had cultural, economic, and military superiority, which led to their exaltation. Economic and technological progress had both positive and negative consequences. |

| Thesis statement | Nationalism was gradually promoted in the press and mass media. The adherents of nationalism saw the interests of other nations as less of a priority than their own. It is impossible to ignore the fact that these mass movements had a serious influence on the events of WWI. |

| Body paragraph 1 | The idea of opposing an overwhelming state is seen as noble but often leads to protracted wars. This was most evident in Serbia, where nationalism was at its peak before the war. Therefore, it is not surprising that more distinct nationalism began to emerge in the suppressed countries. |

| Body paragraph 2 | Nationalism was represented not only by social movements but also by militaristic ones. It was important for leaders to create a sense of power so that other countries would see their superiority in the event of war. Every leading nation saw its military advantages and was not afraid of hostilities. |

| Body paragraph 3 | The fact of the influence of nationalist ideas on World War I is of great importance because this social phenomenon is still relevant. Even in a relatively peaceful modern society, there are many supporters of radical nationalism, which indicates the dangers of possible military conflicts. |

| Conclusion | Nationalism played a huge role in the minds of people at the beginning of the 20th century, and, consequently, in leading Europe to war. Perhaps the origins of the ideas of nationalism arose through inculcation, but the scale of military events and their results show that the population supported it. It is important to remember these events to avoid their recurrence. |

Now you have all you need to write an excellent essay on nationalism. Liked this article? Let us know in the comment section below!

You might also be interested in:

- Canadian Identity Essay: Essay Topics and Writing Guide

- Human Trafficking Essay for College: Topics and Examples

- Essay on Corruption: How to Stop It. Quick Guide

- Murder Essay: Top 3 Killing Ideas to Complete your Essay

- Student Exchange Program (Flex) Essay Topics

- Gun Control Essay: How-to Guide + 150 Argumentative Topics

- Transportation Essay: Writing Tips and 85 Brilliant Topics

✏️ Nationalism Essay FAQ

You can define nationalism as the identification with nation and support of its interests. Nationalism is aimed at protecting a nation from foreign influences. This idea is important because it helps a country be strong and independent.

Most specialists highlight religious, political, and ethnic nationalism. Different classifications suggest various types of nationalism. It can be positive and negative, militant, extreme, etc. The phenomenon is complex and multidimensional. You can find it in most societies.

Nationalism is a complex phenomenon. It has positive and negative sides. Because of this, it’s crucial to write about it objectively. In any academic text on nationalism you should provide relevant arguments, quotes, and other evidence.

A nationalism essay focuses on the concept’s principles, advantages, and disadvantages. You can find numerous articles and research papers about it online or in your school’s library. Beware of copying anything directly: use them only as a source of inspiration.

🔗 References

- A New Dawn in Nationalism Studies? European History Quaterly

- The SAGE Handbook of Nations and Nationalism: Google Books

- Nationalism Studies Program: 2-year MA Student Handbook (CEU)

- Nationalism: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Nationalism is back: The Economist

- Working-class Neo-Nationalism in Postsocialist Cluj, Romania: Academia

- Nationalism: Encyclopedia Britannica

- Nationalism: Definition, Examples, and History: The Balance

- The Problem of Nationalism: The Heritage Foundation

- Effects of Nationalism: LearnAlberta

- The Difference Between Patriotism and Nationalism: Merriam-Webster

- Varieties of American Popular Nationalism: Harvard University

- Not So Civic: Is There a Difference between Ethnic and Civic Nationalism?: Annual Review

- Globalism and Nationalism: Which One Is Bad?: Taylor & Francis Online

- African Nationalism and the Struggle for Freedom: Pearson Higher Education

- Share to Facebook

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

![nationalism pros and cons essay 331 Advantages and Disadvantages Essay Topics [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/smiling-young-woman-284x153.jpg)

Is globalization a beneficial process? What are the pros and cons of a religious upbringing? Do the drawbacks of immigration outweigh the benefits? These questions can become a foundation for your advantages and disadvantages essay. And we have even more ideas to offer! There is nothing complicated about writing this...

This time you have to write a World War II essay, paper, or thesis. It means that you have a perfect chance to refresh those memories about the war that some of us might forget. So many words can be said about the war in that it seems you will...

![nationalism pros and cons essay 413 Science and Technology Essay Topics to Write About [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/scientist-working-in-science-and-chemical-for-health-e1565366539163-284x153.png)

Would you always go for Bill Nye the Science Guy instead of Power Rangers as a child? Were you ready to spend sleepless nights perfecting your science fair project? Or maybe you dream of a career in science? Then this guide by Custom-Writing.org is perfect for you. Here, you’ll find...

![nationalism pros and cons essay 256 Satirical Essay Topics & Satire Essay Examples [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/classmates-learning-and-joking-at-school-e1565370536154-284x153.jpg)

A satire essay is a creative writing assignment where you use irony and humor to criticize people’s vices or follies. It’s especially prevalent in the context of current political and social events. A satirical essay contains facts on a particular topic but presents it in a comical way. This task...

![nationalism pros and cons essay 267 Music Essay Topics + Writing Guide [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/lady-is-playing-piano-284x153.jpg)

Your mood leaves a lot to be desired. Everything around you is getting on your nerves. But still, there’s one thing that may save you: music. Just think of all the times you turned on your favorite song, and it lifted your spirits! So, why not write about it in a music essay? In this article, you’ll find all the information necessary for this type of assignment: And...

Not everyone knows it, but globalization is not a brand-new process that started with the advent of the Internet. In fact, it’s been around throughout all of human history. This makes the choice of topics related to globalization practically endless. If you need help choosing a writing idea, this Custom-Writing.org...

In today’s world, fashion has become one of the most significant aspects of our lives. It influences everything from clothing and furniture to language and etiquette. It propels the economy, shapes people’s personal tastes, defines individuals and communities, and satisfies all possible desires and needs. In this article, Custom-Writing.org experts...

Early motherhood is a very complicated social problem. Even though the number of teenage mothers globally has decreased since 1991, about 12 million teen girls in developing countries give birth every year. If you need to write a paper on the issue of adolescent pregnancy and can’t find a good...

Human rights are moral norms and behavior standards towards all people that are protected by national and international law. They represent fundamental principles on which our society is founded. Human rights are a crucial safeguard for every person in the world. That’s why teachers often assign students to research and...

Global warming has been a major issue for almost half a century. Today, it remains a topical problem on which the future of humanity depends. Despite a halt between 1998 and 2013, world temperatures continue to rise, and the situation is expected to get worse in the future. When it...

Have you ever witnessed someone face unwanted aggressive behavior from classmates? According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, 1 in 5 students says they have experienced bullying at least once in their lifetime. These shocking statistics prove that bullying is a burning topic that deserves detailed research. In this...

Recycling involves collecting, processing, and reusing materials to manufacture new products. With its help, we can preserve natural resources, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and save energy. And did you know that recycling also creates jobs and supports the economy? If you want to delve into this exciting topic in your...

Hi. Can you please help me out in getting a simple topic to discuss/write for my final essay in my masters programme pertaining to nationalism. I’m new to this field of study and would want to enjoy reading and writing this final essay. Thanks in advance for your help.

Thanks to historians all over the world!

I have to write a 3000-word essay on the following topic: “Is it possible to imagine nationalism without the nation”? I find the readings difficult to understand and would greatly appreciate any help you could give me. Thank you. Noreen Devine

Hi Noreen, We’d be happy to help you with this task. Don’t hesitate to place an order with our writing company. Our best writer will help you understand the readings and create a great paper.

To Whom it May Concern, Thank you so much for your help. This morning I was reading your tips on how to write an essay about nationalism, and I find that it’s so helpful. I will contact you soon for help.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Nationalism

The term “nationalism” is generally used to describe two phenomena:

- the attitude that the members of a nation have when they care about their national identity, and

- the actions that the members of a nation take when seeking to achieve (or sustain) self-determination.

(1) raises questions about the concept of a nation (or national identity), which is often defined in terms of common origin, ethnicity, or cultural ties, and specifically about whether an individual’s membership in a nation should be regarded as non-voluntary or voluntary. (2) raises questions about whether self-determination must be understood as involving having full statehood with complete authority over domestic and international affairs, or whether something less is required.

Nationalism came into the focus of philosophical debate three decades ago, in the nineties, partly in consequence of rather spectacular and troubling nationalist clashes. Surges of nationalism tend to present a morally ambiguous, and for this reason often fascinating, picture. “National awakening” and struggles for political independence are often both heroic and cruel; the formation of a recognizably national state often responds to deep popular sentiment but sometimes yields inhuman consequences, from violent expulsion and “cleansing” of non-nationals to organized mass murder. The moral debate on nationalism reflects a deep moral tension between solidarity with oppressed national groups on the one hand and repulsion in the face of crimes perpetrated in the name of nationalism on the other. Moreover, the issue of nationalism points to a wider domain of problems related to the treatment of ethnic and cultural differences within democratic polity, arguably among the most pressing problems of contemporary political theory.

In the last two decades, migration crisis and the populist reactions to migration and domestic economic issues have been the defining traits of a new political constellation. The traditional issue of the contrast between nationalism and cosmopolitanism has changed its profile: the current drastic contrast is between populist aversion to the foreigners-migrants and a more generous, or simply just, attitude of acceptance and Samaritan help. The populist aversion inherits some features traditionally associated with patriotism and nationalism, and the opposite attitude the main features of traditional cosmopolitanism. One could expect that the work on nationalism will be moving further on this new and challenging playground, addressing the new contrast and trying to locate nationalism in relation to it.

In this entry, we shall first present conceptual issues of definition and classification (Sections 1 and 2) and then the arguments put forward in the debate (Section 3), dedicating more space to the arguments in favor of nationalism than to those against it in order to give the philosophical nationalist a proper hearing. In the last part we shall turn to the new constellation and sketch the new issues raised by nationalist and trans-nationalist populisms and the migration crisis.

1.1 The Basic Concept of Nationalism

1.2 the concept of a nation, 2.1 concepts of nationalism: classical and liberal, 2.2 moral claims, classical vs. liberal: the centrality of nation, 3.1 classical and liberal nationalisms, 3.2 arguments in favor of nationalism, classical vs. liberal: the deep need for community, 3.3 arguments in favor of nationalism: issues of justice, 3.4 populism and a new face of nationalism, 3.5 nation-state in global context, 4. conclusion, introduction, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is a nation.

Although the term “nationalism” has a variety of meanings, it centrally encompasses two phenomena: (1) the attitude that the members of a nation have when they care about their identity as members of that nation and (2) the actions that the members of a nation take in seeking to achieve (or sustain) some form of political sovereignty (see for example, Nielsen 1998–9: 9). Each of these aspects requires elaboration.

- raises questions about the concept of a nation or national identity, about what it is to belong to a nation, and about how much one ought to care about one’s nation. Nations and national identity may be defined in terms of common origin, ethnicity, or cultural ties, and while an individual’s membership in the nation is often regarded as involuntary, it is sometimes regarded as voluntary. The degree of care for one’s nation that nationalists require is often, but not always, taken to be very high: according to such views, the claims of one’s nation take precedence over rival contenders for authority and loyalty. [ 1 ]

- raises questions about whether sovereignty requires the acquisition of full statehood with complete authority over domestic and international affairs, or whether something less than statehood suffices. Although sovereignty is often taken to mean full statehood (Gellner 1983: ch. 1), [ 2 ] possible exceptions have been recognized (Miller 1992: 87; Miller 2000). Some authors even defend an anarchist version of patriotism-moderate nationalism foreshadowed by Bakunin (see Sparrow 2007).

There is a terminological and conceptual question of distinguishing nationalism from patriotism. A popular proposal is the contrast between attachment to one’s country as defining patriotism and attachment to one’s people and its traditions as defining nationalism (Kleinig 2014: 228, and Primoratz 2017: Section 1.2). One problem with this proposal is that love for a country is not really just love of a piece of land but normally involves attachment to the community of its inhabitants, and this introduces “nation” into the conception of patriotism. Another contrast is the one between strong, and somewhat aggressive attachment (nationalism) and a mild one (patriotism), dating back at least to George Orwell (see his 1945 essay). [ 3 ]

Despite these definitional worries, there is a fair amount of agreement about the classical, historically paradigmatic form of nationalism. It typically features the supremacy of the nation’s claims over other claims to individual allegiance and full sovereignty as the persistent aim of its political program. Territorial sovereignty has traditionally been seen as a defining element of state power and essential for nationhood. It was extolled in classic modern works by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau and is returning to center stage in the debate, though philosophers are now more skeptical (see below). Issues surrounding the control of the movement of money and people (in particular immigration) and the resource rights implied in territorial sovereignty make the topic politically central in the age of globalization and philosophically interesting for nationalists and anti-nationalists alike.

In recent times, the philosophical focus has moved more in the direction of “liberal nationalism”, the view that mitigates the classical claims and tries to bring together the pro-national attitude and the respect for traditional liberal values. For instance, the territorial state as political unit is seen by classical nationalists as centrally “belonging” to one ethnic-cultural group and as actively charged with protecting and promulgating its traditions. The liberal variety allows for “sharing” of the territorial state with non-dominant ethnic groups. Consequences are varied and quite interested (for more see below, especially section 2.1 ).

In its general form, the issue of nationalism concerns the mapping between the ethno-cultural domain (featuring ethno-cultural groups or “nations”) and the domain of political organization. In breaking down the issue, we have mentioned the importance of the attitude that the members of a nation have when they care about their national identity. This point raises two sorts of questions. First, the descriptive ones:

Second, the normative ones:

This section discusses the descriptive questions, starting with (1a) and (1b) ;the normative questions are addressed in Section 3 on the moral debate. If one wants to enjoin people to struggle for their national interests, one must have some idea about what a nation is and what it is to belong to a nation. So, in order to formulate and ground their evaluations, claims, and directives for action, pro-nationalist thinkers have expounded theories of ethnicity, culture, nation, and state. Their opponents have in turn challenged these elaborations. Now, some presuppositions about ethnic groups and nations are essential for the nationalist, while others are theoretical elaborations designed to support the essential ones. The definition and status of the social group that benefits from the nationalist program, variously called the “nation”, “ethno-nation”, or “ethnic group”, is essential. Since nationalism is particularly prominent with groups that do not yet have a state, a definition of nation and nationalism purely in terms of belonging to a state is a non-starter.

Indeed, purely “civic” loyalties are often categorized separately under the title “patriotism”, which we already mentioned, or “constitutional patriotism”. [ 4 ] This leaves two extreme options and a number of intermediates. The first extreme option has been put forward by a small but distinguished band of theorists. [ 5 ] According to their purely voluntaristic definition, a nation is any group of people aspiring to a common political state-like organization. If such a group of people succeeds in forming a state, the loyalties of the group members become “civic” (as opposed to “ethnic”) in nature. At the other extreme, and more typically, nationalist claims are focused upon the non-voluntary community of common origin, language, tradition, and culture: the classic ethno-nation is a community of origin and culture, including prominently a language and customs. The distinction is related (although not identical) to that drawn by older schools of social and political science between “civic” and “ethnic” nationalism, the former being allegedly Western European and the latter more Central and Eastern European, originating in Germany. [ 6 ] Philosophical discussions centered on nationalism tend to concern the ethnic-cultural variants only, and this habit will be followed here. A group aspiring to nationhood on this basis will be called an “ethno-nation” to underscore its ethno-cultural rather than purely civic underpinnings. For the ethno-(cultural) nationalist it is one’s ethnic-cultural background that determines one’s membership in the community. One cannot choose to be a member; instead, membership depends on the accident of origin and early socialization. However, commonality of origin has become mythical for most contemporary candidate groups: ethnic groups have been mixing for millennia.

Sophisticated, liberal pro-nationalists therefore tend to stress cultural membership only and speak of “nationality”, omitting the “ethno-” part (Miller 1992, 2000; Tamir 1993,2013; Gans 2003). Michel Seymour’s proposal of a “socio-cultural definition” adds a political dimension to the purely cultural one: a nation is a cultural group, possibly but not necessarily united by a common descent, endowed with civic ties (Seymour 2000). This is the kind of definition that would be accepted by most parties in the debate today. So defined, the nation is a somewhat mixed category, both ethno-cultural and civic, but still closer to the purely ethno-cultural than to the purely civic extreme.