- Utility Menu

harvardchan_logo.png

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Case-Based Teaching & Learning Initiative

Teaching cases & active learning resources for public health education, the case study handbook, revised edition: a student's guide.

Publisher's Version

Using our case library

Access to cases.

Many of our cases are available for sale through Harvard Business Publishing in the Harvard T.H. Chan case collection . Others are free to download through this website .

Cases in this collection may be used free of charge by Harvard Chan course instructors in their teaching. Contact Allison Bodznick , Harvard Chan Case Library administrator, for access.

Access to teaching notes

Teaching notes are available as supporting material to many of the cases in the Harvard Chan Case Library. Teaching notes provide an overview of the case and suggested discussion questions, as well as a roadmap for using the case in the classroom.

Access to teaching notes is limited to course instructors only.

- Teaching notes for cases available through Harvard Business Publishing may be downloaded after registering for an Educator account .

- To request teaching notes for cases that are available for free through this website, look for the "Teaching note available for faculty/instructors " link accompanying the abstract for the case you are interested in; you'll be asked to complete a brief survey verifying your affiliation as an instructor.

Using the Harvard Business Publishing site

Faculty and instructors with university affiliations can register for Educator access on the Harvard Business Publishing website, where many of our cases are available . An Educator account provides access to teaching notes, full-text review copies of cases, articles, simulations, course planning tools, and discounted pricing for your students.

Filter cases

Case format.

- Case (116) Apply Case filter

- Case book (5) Apply Case book filter

- Case collection (2) Apply Case collection filter

- Industry or background note (1) Apply Industry or background note filter

- Simulation or role play (4) Apply Simulation or role play filter

- Teaching example (1) Apply Teaching example filter

- Teaching pack (2) Apply Teaching pack filter

Case availability & pricing

- Available for purchase from Harvard Business Publishing (73) Apply Available for purchase from Harvard Business Publishing filter

- Download free of charge (50) Apply Download free of charge filter

- Request from author (4) Apply Request from author filter

Case discipline/subject

- Child & adolescent health (15) Apply Child & adolescent health filter

- Maternal & child health (1) Apply Maternal & child health filter

- Human rights & health (11) Apply Human rights & health filter

- Women, gender, & health (11) Apply Women, gender, & health filter

- Social & behavioral sciences (41) Apply Social & behavioral sciences filter

- Social innovation & entrepreneurship (11) Apply Social innovation & entrepreneurship filter

- Finance & accounting (10) Apply Finance & accounting filter

- Environmental health (12) Apply Environmental health filter

- Epidemiology (6) Apply Epidemiology filter

- Ethics (5) Apply Ethics filter

- Global health (28) Apply Global health filter

- Health policy (35) Apply Health policy filter

- Healthcare management (55) Apply Healthcare management filter

- Life sciences (5) Apply Life sciences filter

- Marketing (15) Apply Marketing filter

- Multidisciplinary (16) Apply Multidisciplinary filter

- Nutrition (6) Apply Nutrition filter

- Population health (8) Apply Population health filter

- Quality improvement (4) Apply Quality improvement filter

- Quantative methods (3) Apply Quantative methods filter

- Social medicine (7) Apply Social medicine filter

- Technology (6) Apply Technology filter

Geographic focus

- Cambodia (1) Apply Cambodia filter

- Australia (1) Apply Australia filter

- Bangladesh (2) Apply Bangladesh filter

- China (1) Apply China filter

- Egypt (1) Apply Egypt filter

- El Salvador (1) Apply El Salvador filter

- Guatemala (2) Apply Guatemala filter

- Haiti (2) Apply Haiti filter

- Honduras (1) Apply Honduras filter

- India (3) Apply India filter

- International/multiple countries (11) Apply International/multiple countries filter

- Israel (3) Apply Israel filter

- Japan (2) Apply Japan filter

- Kenya (2) Apply Kenya filter

- Liberia (1) Apply Liberia filter

- Mexico (4) Apply Mexico filter

- Nigeria (1) Apply Nigeria filter

- Pakistan (1) Apply Pakistan filter

- Philippines (1) Apply Philippines filter

- Rhode Island (1) Apply Rhode Island filter

- South Africa (2) Apply South Africa filter

- Turkey (1) Apply Turkey filter

- Uganda (2) Apply Uganda filter

- United Kingdom (2) Apply United Kingdom filter

- United States (63) Apply United States filter

- California (6) Apply California filter

- Colorado (2) Apply Colorado filter

- Connecticut (1) Apply Connecticut filter

- Louisiana (1) Apply Louisiana filter

- Maine (1) Apply Maine filter

- Massachusetts (14) Apply Massachusetts filter

- Michigan (1) Apply Michigan filter

- Minnesota (1) Apply Minnesota filter

- New Jersey (1) Apply New Jersey filter

- New York (3) Apply New York filter

- Washington DC (1) Apply Washington DC filter

- Washington state (2) Apply Washington state filter

- Zambia (1) Apply Zambia filter

Case keywords

- Financial analysis & accounting practices (1) Apply Financial analysis & accounting practices filter

- Law & policy (2) Apply Law & policy filter

- Sexual & reproductive health & rights (2) Apply Sexual & reproductive health & rights filter

- Cigarettes & e-cigarettes (1) Apply Cigarettes & e-cigarettes filter

- Occupational health & safety (2) Apply Occupational health & safety filter

- Bullying & cyber-bullying (1) Apply Bullying & cyber-bullying filter

- Sports & athletics (1) Apply Sports & athletics filter

- Women's health (1) Apply Women's health filter

- Anchor mission (1) Apply Anchor mission filter

- Board of directors (1) Apply Board of directors filter

- Body mass index (1) Apply Body mass index filter

- Carbon pollution (1) Apply Carbon pollution filter

- Child protection (2) Apply Child protection filter

- Collective impact (1) Apply Collective impact filter

- Colorism (1) Apply Colorism filter

- Community health (3) Apply Community health filter

- Community organizing (2) Apply Community organizing filter

- Corporate social responsibility (2) Apply Corporate social responsibility filter

- Crisis communications (2) Apply Crisis communications filter

- DDT (1) Apply DDT filter

- Dietary supplements (1) Apply Dietary supplements filter

- Education (3) Apply Education filter

- Higher education (1) Apply Higher education filter

- Electronic medical records (1) Apply Electronic medical records filter

- Air pollution (1) Apply Air pollution filter

- Lead poisoning (1) Apply Lead poisoning filter

- Gender-based violence (3) Apply Gender-based violence filter

- Genetic testing (1) Apply Genetic testing filter

- Geriatrics (1) Apply Geriatrics filter

- Global health (3) Apply Global health filter

- Health (in)equity (6) Apply Health (in)equity filter

- Health care delivery (3) Apply Health care delivery filter

- Health reform (1) Apply Health reform filter

- Homelessness (3) Apply Homelessness filter

- Housing (1) Apply Housing filter

- Insecticide (1) Apply Insecticide filter

- Legislation (2) Apply Legislation filter

- Management issues (4) Apply Management issues filter

- Cost accounting (1) Apply Cost accounting filter

- Differential analysis (1) Apply Differential analysis filter

- Queuing analysis (1) Apply Queuing analysis filter

- Marketing (5) Apply Marketing filter

- Mergers (3) Apply Mergers filter

- Strategic planning (6) Apply Strategic planning filter

- Marijuana (1) Apply Marijuana filter

- Maternal and child health (2) Apply Maternal and child health filter

- Medical Spending (1) Apply Medical Spending filter

- Mental health (1) Apply Mental health filter

- Mercury (1) Apply Mercury filter

- Monitoring and Evaluation (1) Apply Monitoring and Evaluation filter

- Non-profit hospital (1) Apply Non-profit hospital filter

- Pharmaceuticals (5) Apply Pharmaceuticals filter

- Power plants (2) Apply Power plants filter

- Prevention (1) Apply Prevention filter

- Public safety (4) Apply Public safety filter

- Racism (1) Apply Racism filter

- Radiation (1) Apply Radiation filter

- Research practices (1) Apply Research practices filter

- Rural hospital (2) Apply Rural hospital filter

- Salmonella (1) Apply Salmonella filter

- Sanitation (1) Apply Sanitation filter

- Seafood (1) Apply Seafood filter

- Skin tanning (1) Apply Skin tanning filter

- Social business (1) Apply Social business filter

- Social determinants of health (9) Apply Social determinants of health filter

- Social Impact Bonds (1) Apply Social Impact Bonds filter

- Social media (2) Apply Social media filter

- State governance (2) Apply State governance filter

- Statistics (1) Apply Statistics filter

- Surveillance (3) Apply Surveillance filter

- United Nations (1) Apply United Nations filter

- Vaccination (4) Apply Vaccination filter

- Water (3) Apply Water filter

- Wellness (1) Apply Wellness filter

- Workplace/employee health (4) Apply Workplace/employee health filter

- World Health Organization (3) Apply World Health Organization filter

Supplemental teaching material

- Additional teaching materials available (12) Apply Additional teaching materials available filter

- Simulation (2) Apply Simulation filter

- Multi-part case (18) Apply Multi-part case filter

- Teaching note available (70) Apply Teaching note available filter

Author affiliation

- Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at Harvard University (12) Apply Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at Harvard University filter

- Harvard Business School (22) Apply Harvard Business School filter

- Harvard Kennedy School of Government (1) Apply Harvard Kennedy School of Government filter

- Harvard Malaria Initiative (1) Apply Harvard Malaria Initiative filter

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (98) Apply Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health filter

- Social Medicine Consortium (8) Apply Social Medicine Consortium filter

- Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED) (11) Apply Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED) filter

- Women, Gender, and Health interdisciplinary concentration (1) Apply Women, Gender, and Health interdisciplinary concentration filter

Health condition

- Alcohol & drug use (1) Apply Alcohol & drug use filter

- Opioids (1) Apply Opioids filter

- Asthma (1) Apply Asthma filter

- Breast implants (1) Apply Breast implants filter

- Cancer (3) Apply Cancer filter

- Breast cancer (2) Apply Breast cancer filter

- Cervical cancer (1) Apply Cervical cancer filter

- Cardiovascular disease (1) Apply Cardiovascular disease filter

- Cholera (1) Apply Cholera filter

- COVID-19 (3) Apply COVID-19 filter

- Disordered eating (2) Apply Disordered eating filter

- Ebola (2) Apply Ebola filter

- Food poisoning (1) Apply Food poisoning filter

- HPV (1) Apply HPV filter

- Influenza (2) Apply Influenza filter

- Injury (2) Apply Injury filter

- Road traffic injury (1) Apply Road traffic injury filter

- Sharps injury (1) Apply Sharps injury filter

- Malaria (2) Apply Malaria filter

- Malnutrition (1) Apply Malnutrition filter

- Meningitis (1) Apply Meningitis filter

- Obesity (3) Apply Obesity filter

- Psychological trauma (1) Apply Psychological trauma filter

- Skin bleaching (1) Apply Skin bleaching filter

Filter resources

Resource format.

- Article (15) Apply Article filter

- Video (8) Apply Video filter

- Blog or post (7) Apply Blog or post filter

- Slide deck or presentation (5) Apply Slide deck or presentation filter

- Book (2) Apply Book filter

- Digital resource (2) Apply Digital resource filter

- Peer-reviewed research (2) Apply Peer-reviewed research filter

- Publication (2) Apply Publication filter

- Conference proceedings (1) Apply Conference proceedings filter

- Internal Harvard resource (1) Apply Internal Harvard resource filter

Resource topic

- Teaching, learning, & pedagogy (33) Apply Teaching, learning, & pedagogy filter

- Teaching & learning with the case method (14) Apply Teaching & learning with the case method filter

- Active learning (12) Apply Active learning filter

- Leading discussion (10) Apply Leading discussion filter

- Case writing (9) Apply Case writing filter

- Writing a case (8) Apply Writing a case filter

- Asking effective questions (5) Apply Asking effective questions filter

- Engaging students (5) Apply Engaging students filter

- Managing the classroom (4) Apply Managing the classroom filter

- Writing a teaching note (4) Apply Writing a teaching note filter

- Teaching inclusively (3) Apply Teaching inclusively filter

- Active listening (1) Apply Active listening filter

- Assessing learning (1) Apply Assessing learning filter

- Planning a course (1) Apply Planning a course filter

- Problem-based learning (1) Apply Problem-based learning filter

- Abare, Marce (1)

- Abdallah, Mouin (1)

- Abell, Derek (1)

- Abo Kweder, Amir (1)

- Al Kasir, Ahmad (1)

- Alidina, Shehnaz (3)

- Ammerman, Colleen (1)

- Andersen, Espen (1)

- Anyona, Mamka (1)

- Arnold, Brittany (1)

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

What is the Case Study Method?

Simply put, the case method is a discussion of real-life situations that business executives have faced.

On average, you'll attend three to four different classes a day, for a total of about six hours of class time (schedules vary). To prepare, you'll work through problems with your peers.

How the Case Method Creates Value

Often, executives are surprised to discover that the objective of the case study is not to reach consensus, but to understand how different people use the same information to arrive at diverse conclusions. When you begin to understand the context, you can appreciate the reasons why those decisions were made. You can prepare for case discussions in several ways.

Case Discussion Preparation Details

In self-reflection.

The time you spend here is deeply introspective. You're not only working with case materials and assignments, but also taking on the role of the case protagonist—the person who's supposed to make those tough decisions. How would you react in those situations? We put people in a variety of contexts, and they start by addressing that specific problem.

In a small group setting

The discussion group is a critical component of the HBS experience. You're working in close quarters with a group of seven or eight very accomplished peers in diverse functions, industries, and geographies. Because they bring unique experience to play you begin to see that there are many different ways to wrestle with a problem—and that’s very enriching.

In the classroom

The faculty guides you in examining and resolving the issues—but the beauty here is that they don't provide you with the answers. You're interacting in the classroom with other executives—debating the issue, presenting new viewpoints, countering positions, and building on one another's ideas. And that leads to the next stage of learning.

Beyond the classroom

Once you leave the classroom, the learning continues and amplifies as you get to know people in different settings—over meals, at social gatherings, in the fitness center, or as you are walking to class. You begin to distill the takeaways that you want to bring back and apply in your organization to ensure that the decisions you make will create more value for your firm.

How Cases Unfold In the Classroom

Pioneered by HBS faculty, the case method puts you in the role of the chief decision maker as you explore the challenges facing leading companies across the globe. Learning to think fast on your feet with limited information sharpens your analytical skills and empowers you to make critical decisions in real time.

To get the most out of each case, it's important to read and reflect, and then meet with your discussion group to share your insights. You and your peers will explore the underlying issues, compare alternatives, and suggest various ways of resolving the problem.

How to Prepare for Case Discussions

There's more than one way to prepare for a case discussion, but these general guidelines can help you develop a method that works for you.

Preparation Guidelines

Read the professor's assignment or discussion questions.

The assignment and discussion questions help you focus on the key aspects of the case. Ask yourself: What are the most important issues being raised?

Read the first few paragraphs and then skim the case

Each case begins with a text description followed by exhibits. Ask yourself: What is the case generally about, and what information do I need to analyze?

Reread the case, underline text, and make margin notes

Put yourself in the shoes of the case protagonist, and own that person's problems. Ask yourself: What basic problem is this executive trying to resolve?

Note the key problems on a pad of paper and go through the case again

Sort out relevant considerations and do the quantitative or qualitative analysis. Ask yourself: What recommendations should I make based on my case data analysis?

Case Study Best Practices

The key to being an active listener and participant in case discussions—and to getting the most out of the learning experience—is thorough individual preparation.

We've set aside formal time for you to discuss the case with your group. These sessions will help you to become more confident about sharing your views in the classroom discussion.

Participate

Actively express your views and challenge others. Don't be afraid to share related "war stories" that will heighten the relevance and enrich the discussion.

If the content doesn't seem to relate to your business, don't tune out. You can learn a lot about marketing insurance from a case on marketing razor blades!

Actively apply what you're learning to your own specific management situations, both past and future. This will magnify the relevance to your business.

People with diverse backgrounds, experiences, skills, and styles will take away different things. Be sure to note what resonates with you, not your peers.

Being exposed to so many different approaches to a given situation will put you in a better position to enhance your management style.

Frequently Asked Questions

What can i expect on the first day, what happens in class if nobody talks, does everyone take part in "role-playing".

- Case Teaching Resources

Teaching With Cases

Included here are resources to learn more about case method and teaching with cases.

What Is A Teaching Case?

This video explores the definition of a teaching case and introduces the rationale for using case method.

Narrated by Carolyn Wood, former director of the HKS Case Program

Learning by the Case Method

Questions for class discussion, common case teaching challenges and possible solutions, teaching with cases tip sheet, teaching ethics by the case method.

The case method is an effective way to increase student engagement and challenge students to integrate and apply skills to real-world problems. In these videos, Using the Case Method to Teach Public Policy , you'll find invaluable insights into the art of case teaching from one of HKS’s most respected professors, Jose A. Gomez-Ibanez.

Chapter 1: Preparing for Class (2:29)

Chapter 2: How to begin the class and structure the discussion blocks (1:37)

Chapter 3: How to launch the discussion (1:36)

Chapter 4: Tools to manage the class discussion (2:23)

Chapter 5: Encouraging participation and acknowledging students' comments (1:52)

Chapter 6: Transitioning from one block to the next / Importance of body (2:05)

Chapter 7: Using the board plan to feed the discussion (3:33)

Chapter 8: Exploring the richness of the case (1:42)

Chapter 9: The wrap-up. Why teach cases? (2:49)

The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide

William ellet.

Revision includes study guides and new insight for students

The business case study is a powerful learning tool. This practical guide provides students with a potent approach to:

- Recognize case situations and apply appropriate tools to solve problems, make decisions, or develop evaluations

- Quickly establish a base of knowledge about a case

- Write persuasive case-based essays

- Talk about cases effectively in class

The Case Study Handbook comes with downloadable study guides for analyzing and writing about different types of cases, whether they require a decision, an evaluation, or problem diagnosis.

Individual chapters are available in PDF for purchase or to assign in a class.

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 |

Downloadable Study Guides

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 |

About the Author

William Ellet has worked with MBA students for over thirty years. He has taught at Harvard Business School, Brandeis University, George Washington University, and the University of Miami. He has facilitated case teaching seminars for Harvard Business Publishing and as a consultant in China, Saudi Arabia, the United States, Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Brazil. His publications include an online course (Management Communication), this book, cases, and a video, all published by Harvard Business School or Harvard Business Publishing.

With cases, you need to change how you read and, ultimately, how you think. Cases are a jigsaw puzzle with the pieces arranged in a confusing pattern. You need to take the pieces and fit them into a pattern that helps you understand the main issue and think about the optimal ways to address it. You need to be comfortable with less than perfect information and an irreducible level of uncertainty. You need to be able to filter the noise of irrelevant or relatively unimportant information. You need to focus on key tasks that allow you to put pieces together in a meaningful pattern, which in turn will give you a better understanding of the main issue and put you in a position to make impactful recommendations. The Case Reading Process Read the first and last sections of the case. What do they tell you about the core scenario of the case? These sections typically give you the clues needed to identify the core scenario. Take a quick look at the other sections and the exhibits to determine what information the case contains. The purpose is to learn what information is in the case and where. Avoid reading sections slowly and trying to memorize the content. Stop! Now is the time to think rather than read. What is the core scenario of the case? What does the main character have to do? What is the major uncertainty? Identify the core scenario by asking the 2 questions. Once you are reasonably certain of the core scenario—decision, evaluation, or problem diagnosis—you can use the relevant framework to ask the questions in the next step. Those questions will give you a specific agenda for productively exploring the case. What do you need to know to accomplish what the main character has to do or to resolve the major uncertainty? List the things you need to know about the situation. Don’t worry about being wrong. This is probably the most important step of the entire process. If you don’t know what you’re looking for in the case, you won’t find it. The right core scenario framework will prompt you to list things that you need to explore. For example, for a decision scenario case, you should think about the best criteria the main character can use to make the decision. To determine criteria, think about quantitative and qualitative tools you’ve learned that can help you. Go through the case, skim sections, and mark places or takes notes about where you find information that corresponds to the list of things you need to know. You’re ready for a deep dive into the case. Carefully read and analyze the information you’ve identified that is relevant to the things you need to know. As you proceed in your analysis, ask, How does what I’m learning help me understand the main issue? The most efficient and least confusing way to read and analyze is to peel the onion—to study one issue at a time. For instance, let’s say that a decision has financial and marketing criteria. Analyzing the financial issues separately from marketing is far less confusing than trying to switch back and forth. As your analysis moves from issue to issue, you may discover gaps in your knowledge and have to add items to your list of what you need to know. Your ultimate goal is to arrive at a position or conclusion about the case’s main issue, backed by evidence from the case. Remember, there are usually no objectively right answers to a case. The best answer is the one with the strongest evidence backing it. As you learn more, ask, How does what I know help me understand the main issue? When you are preparing a case for class discussion, consider alternative positions. Finally, take some time to think about actions that support your position. What actions does your position support or require? In the real world, analysis is often followed by action. A decision obviously has to be implemented. Usually the entire point of a problem diagnosis is to target action that will solve the problem. And even evaluation has an important action component: sustaining the strengths and shoring up the weaknesses that it has revealed.

Exhibition Home

Business Education & The Case Method

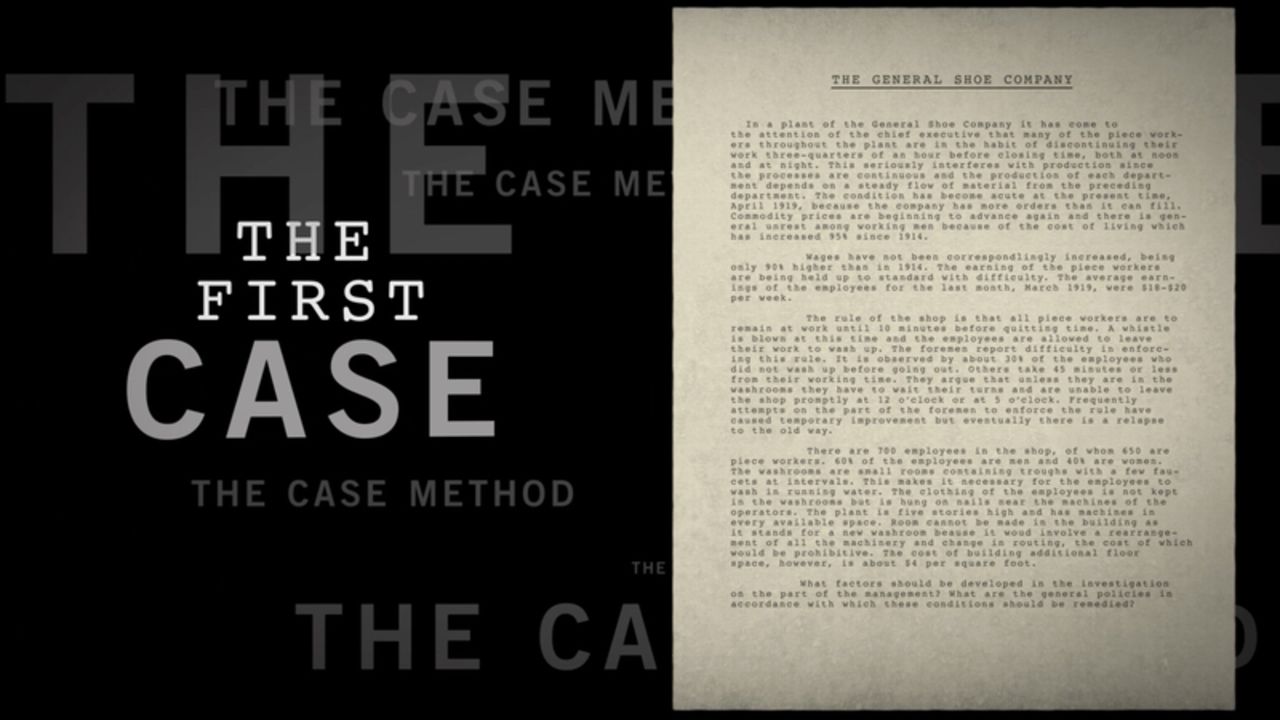

- The General Shoe Company, 1921

Case Writing & Industry

- Expansion of the Case Method

The Case Method Classroom

Teaching & The Case Method

Impact on Research & Curriculum

Global Reach

- Case Method - Research Resources

- HBS & the Case Method - Message From the Director

- HBS & the Case Method Site Credits

- Special Collections

- Baker Library

Homepage banner

From inquiry to action, harvard business school & the case method, homepage section.

Since the 1920s, the case method has been the foundational teaching practice at Harvard Business School (HBS). Based on participant-centered learning, the instructional approach facilitates discussions about real-life problems encountered in business, to prepare students for roles as leaders, managers, and decision makers. The case method encourages students to plan a course of inquiry—analyze, listen, compare other perspectives—and choose a course of action. For over 100 years, HBS has been an innovative leader in the development and refinement of teaching with the case method, helping to shape business education programs and business leaders around the world. “While cases may look different in the future,” HBS Dean Srikant Datar observes, “the fundamental approach of discussion, debate, and deliberation will undoubtedly last into the next century.” 1 Drawing on materials from the HBS Archives, From Inquiry to Action explores the introduction of the case method in the teaching of business administration and highlights the School’s early contributions that have led to the enduring influence of this participant-centered teaching practice.

Homepage Section2

Business education, general shoe.

"The General Shoe Company," 1921

Case Writing

Expansion of The Case Method

Homepage section3

1 Dean Srikant Datar in “Dean Datar Introduces the Case Method Centennial,” 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iI1-K2nECTo. Accessed 2/2/22.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

Learn more about HBS Online's approach to the case method in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span eight subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Digital transformation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

Case Method 100 Years

- Harvard Business School →

- Case Method 100 Years →

Celebrating 100 Years of Case Method Teaching & Learning

Videos .

- 01 NOV 2021

- Harvard Business School

Dean Srikant Datar Introduces the Case Method Centennial

- 30 JAN 2014

Alumni Recall Their First Cold Call

In the News

How the U.S. Government Is Innovating in Its Efforts to Fund Semiconductor Manufacturing

- 03 Sep 2024

Angel City Football Club: A New Business Model for Women’s Sports

- 20 Aug 2024

How EdTech Firm Coursera Is Incorporating GenAI into Its Products and Services

- 06 Aug 2024

The First Case: General Shoe Company

10 may 1922, the case system named.

Universities Adopt HBS Casebooks

Case Research Funded at General Electric

Case Method Catches On

Business Schools Debate Use of the Case Method

Teaching by the Case Method at Radcliffe

15K Cases Produced in 18 Years

Case Method Flexibility Allows for Transition to Wartime Curriculum

600 Cases Written for Military

Industrial Films Introduced in the Classroom

Task force created for case writers, office of case development established, 11 jun 1953.

Aldrich Hall Dedicated

Summer Case Writing Programs Begins

The Case Method Goes Global

Number of Cases and Collections in Print Grows

Annual Goal Set for Case Writing

Groundbreaking Case Series on Swiss Watch Industry

Cases Jump from Paper to Screen

First Directory of Cases Published with 32 Business Schools

Intercollegiate Clearing House for the Distribution of Cases Developed

Learning to Teach by the Case Method

Intercollegiate case bibliography volume iv published.

Experimenting with Case Discussion Simulator

Stimulating Global Case Development

Case clearing house sells enough to break even.

Dynamic Case Series Introduced

Case Method Enters Digital Era

Ford foundation grant supports case materials in developing countries.

First Use of “Tele-Case Discussions”

Prolific Case Author Ruth Hetherston Retires

Ford foundation supports case method teachers.

AASU Founded with Call for More Black Case Protagonists

Doctoral Students Introduced to Case Method Teaching

Cases grouped in course modules.

Using Personal Computers to Analyze Case Materials

Case publishing shifts to computer fulfillment.

Teaching by the Case Method Published

Christensen named university professor.

Work Begins to Put 7K Active Cases Online

Harvard Business School Publishing Created

First Multi-media Case on Pacific Dunlop

Educational technology group founded.

California Research Center Established

Executive Education Establishes Research & Development Group

Making a case for women, research & development focuses on international cases, christensen center founded.

HBS Turns 100 and Looks to the Future of the Case Method

Shanghai Center Opens

HBS Online Introduced

Global research group becomes case research & writing group (crg).

Cold Call Podcast Launched

Collection of cases featuring women developed.

Bringing the Case Method Online During COVID-19 Pandemic

Racial equity plan calls for more black protagonists in case studies.

Celebrating 100 Years of the Case Method

- --> Login or Sign Up

The Case Study Teaching Method

It is easy to get confused between the case study method and the case method , particularly as it applies to legal education. The case method in legal education was invented by Christopher Columbus Langdell, Dean of Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895. Langdell conceived of a way to systematize and simplify legal education by focusing on previous case law that furthered principles or doctrines. To that end, Langdell wrote the first casebook, entitled A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts , a collection of settled cases that would illuminate the current state of contract law. Students read the cases and came prepared to analyze them during Socratic question-and-answer sessions in class.

|

|

|

The Harvard Business School case study approach grew out of the Langdellian method. But instead of using established case law, business professors chose real-life examples from the business world to highlight and analyze business principles. HBS-style case studies typically consist of a short narrative (less than 25 pages), told from the point of view of a manager or business leader embroiled in a dilemma. Case studies provide readers with an overview of the main issue; background on the institution, industry, and individuals involved; and the events that led to the problem or decision at hand. Cases are based on interviews or public sources; sometimes, case studies are disguised versions of actual events or composites based on the faculty authors’ experience and knowledge of the subject. Cases are used to illustrate a particular set of learning objectives; as in real life, rarely are there precise answers to the dilemma at hand.

|

|

|

Our suite of free materials offers a great introduction to the case study method. We also offer review copies of our products free of charge to educators and staff at degree-granting institutions.

For more information on the case study teaching method, see:

- Martha Minow and Todd Rakoff: A Case for Another Case Method

- HLS Case Studies Blog: Legal Education’s 9 Big Ideas

- Teaching Units: Problem Solving , Advanced Problem Solving , Skills , Decision Making and Leadership , Professional Development for Law Firms , Professional Development for In-House Counsel

- Educator Community: Tips for Teachers

Watch this informative video about the Problem-Solving Workshop:

<< Previous: About Harvard Law School Case Studies | Next: Downloading Case Studies >>

Business Case Studies

- Article Databases for Case Studies

- Case Study Database

- Commercial and Free Case Websites

- For Faculty: Teaching with Cases

How to write a case analysis

Suggestions from your librarians.

When you begin writing the analysis, follow any instructions your professor has given . Below are just a few resources that may provide more guidance.

- Business Case Studies for Students For students: How to read & analyze a case and write a case analysis. From Cengage Learning.

- Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?: A Framework for Using Cases to Help Students Become Better Decision Makers This article from Harvard Business Publishing Education is written for faculty but may be useful for students when analyzing Harvard Business School case studies. Outlines the "PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights." more... less... Weinstein, A., Brotspies, H.V., & Gironda, J.T. (2020, September 7). Do your students know how to analyze a case—really?: A framework for using cases to help students become better decision makers. Harvard Business Publishing Education. https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/a-framework-for-using-cases-to-help-students-become-better-decision-makers

- << Previous: For Faculty: Teaching with Cases

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2024 9:31 PM

- URL: https://library.webster.edu/businesscasestudies

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Exhibitions

- Visit and Contact

- UCD Library

- Current Students

- News & Opinion

- Staff Directory

- UCD Connect

Harvard Style Guide: Case studies

- Introduction

- Harvard Tutorial

- In-text citations

- Book with one author

- Book with two or three authors

- Book with four or more authors

- Book with a corporate author

- Book with editor

- Chapter in an edited book

- Translated book

- Translated ancient texts

- Print journal article, one author

- Print journal article, two or three authors

- Print journal article, four or more authors

- eJournal article

- Journal article ePublication (ahead of print)

- Secondary sources

- Generative AI

- Images or photographs

- Lectures/ presentations

- Film/ television

- YouTube Film or Talk

- Music/ audio

- Encyclopaedia and dictionaries

- Email communication

- Conferences

- Official publications

- Book reviews

Case studies

- Group or individual assignments

- Legal Cases (Law Reports)

- No date of publication

- Personal communications

- Repository item

- Citing same author, multiple works, same year

Back to Academic Integrity guide

Reference : Author/editor Last name, Initials. (Year) 'Title of case study' [Case Study], Journal Title, Volume (Issue), pp. page numbers. Available at: URL [Accessed Day Month Year].

Ofek, E., Avery, J., Rudolph, S., Martins Gomes, V., Saadat, N., Tsui, A., & Shroff, Y. (2014) 'Case study second thoughts about a strategy shift' [Case Study], Harvard Business Review , 92(12), pp. 125-129. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=99621003&site=ehost-live [Accessed 10 December 2014].

In-Text-Citation :

- (Author last name, Year)

- Author last name (Year)...

- In their case study Ofek et al. (2014) describe how marketing to the young generation...

Still unsure what in-text citation and referencing mean? Check here .

Still unsure why you need to reference all this information? Check here .

- << Previous: Book reviews

- Next: Datasets >>

- Last Updated: Jul 9, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucd.ie/harvardstyle

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Discount Dozen

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

| Our Shelves |

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

| Gift Cards |

The Case Study Handbook: How to Read, Discuss, and Write Persuasively About CasesIf you're enrolled in an executive education or MBA program, you've probably encountered a powerful learning tool: the business case. But if you're like many people, you may find interpreting and writing about cases mystifying, challenging, or downright frustrating. In "The Case Study Handbook", William Ellet presents a potent new approach for analyzing, discussing, and writing about cases. Early chapters show how to classify cases according to the analytical task they require (solving a problem, making a decision, or forming an evaluation) and quickly establish a base of knowledge about a case. Strategies and templates, in addition to several sample Harvard Business School cases, help you apply the author's framework. Later in the book, Ellet shows how to write persuasive case-analytical essays based on the process laid out earlier. Extensive examples of effective and ineffective writing further reinforce your learning. The book also includes a chapter on how to talk about cases more effectively in class. Any current or prospective MBA or executive education student needs to read this book. There are no customer reviews for this item yet. Classic Totes Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more! Shipping & Pickup We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail! Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club! Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.  Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore © 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected] View our current hours » Join our bookselling team » We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily. Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual. Map Find Harvard Book Store » Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy » Harvard University harvard.edu »

Find anything you save across the site in your account  How a Scientific Dispute Spiralled Into a Defamation LawsuitWhat does a Harvard Business School professor’s decision to sue the professors who raised questions about her research bode for academic autonomy? Over the spring and summer of 2021, three behavioral scientists, acting on a tip, uncovered multiple instances of apparent data manipulation in the work of Francesca Gino , a celebrated Harvard Business School professor. Although the trio held regular academic posts—Joe Simmons, at Wharton; Leif Nelson, at Berkeley; and Uri Simonsohn, at Esade, in Barcelona—they occasionally moonlighted as a kind of informal internal-affairs bureau for the behavioral sciences, a discipline that had never done a particularly good job of policing its own research practices. Although they had come to enjoy some grudging respect, their probes did not earn them many friends. They saw themselves as decent guys—which, despite a measure of pugnacity, they are—and the Gino investigation afforded them an opportunity to demonstrate that their reputation for vigilantism was unfair. In the past, their standard protocol had been to solicit comment from the subject of a critique, and then to publish their findings on their blog, Data Colada. This time, they decided, they would step aside in favor of a proper institutional process. This was something of a gamble. Universities had plenty of incentives to bury evidence of academic misconduct and allow the offender to slip quietly away. Gino’s status made this especially likely: although not quite a household name, she was a tenured, titled professor; a lively contributor to the TED -industrial complex; the author of two self-help guides for the aspiring entrepreneur and goal setter; and a consultant for companies such as Disney and Procter & Gamble. She was an ideal ambassador for the H.B.S. brand—confident, prolific, and sufficiently vague in her pronouncements that an executive could come away from one of her business-lite talks feeling affirmed in whatever previous beliefs he happened to entertain. Her extreme productivity, mostly untroubled by memorable ideas, was self-endorsing. Big Little Lies Gideon Lewis-Kraus on how two academics who studied dishonesty came to be accused of fabricating data. The nature of this investigation was unusual. Often, Data Colada’s findings were inferential—the trio could identify fishy data, even if they couldn’t quite reconstruct what had happened to it—but the results of the Gino audit seemed more difficult to question. Proof, for Harvard, would be relatively easy to secure. University administrators usually have access to researchers’ original data files, which, in some cases, can be at risk of becoming conveniently misplaced. A lot of Gino’s data had been collected with the online survey platform Qualtrics, and Harvard had only to compare the original versions with those which had been attached to the papers. In the estimation of the Data Colada team, this could be largely accomplished in the course of an afternoon. They compiled a single-spaced, eighteen-page dossier and dispatched it in confidence to an H.B.S. administrator. On October 27, 2021, Gino received official notice of an inquiry, and was instructed to come to campus and turn over all “HBS-issued devices” by the end of the business day. Harvard’s investigation (for reasons that Data Colada could not fathom) lumbered on for the next eighteen months. I was in touch with the Data Colada members for much of this time, initially about a separate but related case, but they spoke to me only on the condition that I not pursue any additional reporting until the Gino inquiry had culminated in a final report. In the meantime, Gino continued to advise students, teach classes, and publish papers. Harvard had given her a handsome salary. (She owned a house in Cambridge worth almost four million dollars, on top of a two-and-a-half-million-dollar house next door, which she originally planned to demolish; she withdrew her application to the city’s historical commission about ten days after she was notified of the investigation.) In June, 2023, she was placed on administrative leave, without pay or access to campus, for two years. Her named professorship got rescinded, and the H.B.S. dean sought to initiate the lengthy process required to revoke her tenure. Her colleagues were notified, and journal editors who had published her work were contacted about the various data infidelities, as a first step to retraction. In the weeks to follow, Data Colada rolled out a series of posts in which its members offered their own analysis of the papers in question. Three of the four papers were, in relatively short order, retracted. (The fourth had already been retracted following the discovery of a separate apparent fraud.) On LinkedIn, Gino posted that she was “limited into what I can say publicly,” but that “there will be more to come on all of this.” A few weeks later, Gino filed a twenty-five-million-dollar lawsuit—for defamation, among other things—against Data Colada and Harvard. Gino’s initial complaint suggests that there were perfectly innocent explanations for all the alleged anomalies in the data sets and, furthermore, that if there were in fact no innocent explanations she was not the one holding the bag. (Gino has never wavered in her denial of any wrongdoing. In April, one of her lawyers noted that the idea that “she engaged in fraud is verifiably false.” ) As her attorney told the investigators, “In all four of the studies in question, Professor Gino had relied on the help of research assistants on any given project.” Several months ago, despite the objections of Gino and her attorneys, Judge Myong J. Joun, of the Massachusetts district court, ruled that a redacted version of Harvard’s full investigation report be unsealed. ( The New Yorker had filed a motion in support.) This was the result of something of an unforced error on Gino’s part. In various public forums, she had criticized the report’s procedures and conclusions. The university’s lawyers argued that her repeated public references to select portions of the report’s contents had given the court no choice but to make the entirety of it available; the judge agreed. Perhaps the least interesting aspect of the report is that a protracted process—of interviews with Gino and her collaborators, and forensic analyses of dozens of files found in her work e-mails, on her hard drive, and in her Qualtrics account—not only vindicated but expanded on the claims made by Data Colada. None of the data interventions were subtle. On the first allegation: Harvard found that twenty-eight per cent of survey responses had been manipulated manually to support the hypothesis. On the second: dummy survey responses, absent from the original files, seemed to have spontaneously materialized in the final data set. In perhaps the most comically inept example of alleged misconduct, the apparently falsified data in a file had been deliberately highlighted in gray. In one case, the description of a study had been revised, over several successive drafts and in plain sight of the co-authors, seemingly to compensate for fatal flaws that had been pointed out in the original design. Gino’s defense against this allegation is that the research team hadn’t kept careful track of which version of the paper they were working on—in other words, that an entire group of élite business-school academics was, when it came to basic project management, functionally incompetent. The report itself concedes that the investigation was, if anything, underpowered: after having found Gino guilty of “multiple instances of research misconduct” in four papers that spanned eight years and a passel of co-authors, “the Committee is concerned about other possible instances of research misconduct in Professor Gino’s studies.” The identification of additional examples would not have required heroic exertion. In April, Science magazine published an exposé of what appeared to be repeated instances of plagiarism in Gino’s work; the Montreal-based postdoc Erinn Acland, who, out of idle curiosity, had looked into the matter, found a case of uncredited verbatim reproduction in the first sentence of Gino’s that she happened to examine. In the introduction to Gino’s book “ Rebel Talent: Why It Pays to Break the Rules at Work and in Life ,” the author writes, “Rule breaking does not have to get us into trouble, if done correctly and in the right doses—in fact, it can help us get ahead.” About fifteen pages later, Gino seems to have helped herself along by lifting a banal description of Milan’s fashion district from an Anglophone travel Web site. (One of Gino’s lawyers responded that she is “steadfast in her commitment to uncovering the truth in each instance, responding decisively and correcting the record if necessary,” and that it isn’t fair to litigate such accusations in “the volatile domain of public opinion.”) What’s most remarkable about the report is the emotional tenor. The interviews with Gino’s co-authors, who are rendered speechless by the evidence of betrayal, are painful to read. In the transcripts of her appearances before the committee, its members seem desperate to solicit from Gino some excuse or alibi that will make the whole sorry episode go away. They repeatedly ask her to produce any explanation of the anomalies that would allow the business school to send her back to her post with instructions to exercise a little more oversight in the future. Gino, for her part, seems unaware that the members of the committee will not remain her colleagues for long. She is consistently ingratiating, thanking them profusely for their diligence—“I know this is not part of the job, and so I am just very grateful that you paid so close attention to everything”—and swearing that from this point on she’ll “continue to evolve in my lab practices as necessary over time to ensure accuracy in my work.” The questioning of Gino is polite and collegial, but the final report gives vent to an exasperation with her refusal either to admit wrongdoing or to mount a defense the committee can take seriously. Many of her responses—that, say, “she wasn’t placing a high priority” on the publication of a particular paper, or that she had abandoned work that didn’t pan out—are wholly irrelevant. Others, including that she never had access to the analyses provided by an outside forensic firm hired by Harvard, are inaccurate. Her most robust explanation for the malfeasance is that she may have been set up by a conspiracy of former research assistants, resentful co-authors, and Data Colada. Eight pages of the report are devoted to this “malicious actor” theory. Any such party would have required access to both her Qualtrics account and her hard drive. The same party, or perhaps an additional one, would also have needed access to either the personal computer of a former research assistant or to the research assistant herself, who long ago left academia. In the latter case, the report continues, “they would have needed the ability to convince [the research assistant] to collude with them in falsifying data, and the ability to either instruct her in how to falsify the data or obtain the data from her, falsify it, and then return it to her before she forwarded it to us in May 2022 (accomplishing all of this in the relatively short timeframe—one week—between our request for [the research assistant’s] records from this study and her submission of those records).” It further notes that this would have required not just “great expertise” but the kind of perfect timing found only in “Ocean’s Eleven.” Gino’s insistence that she was framed, the report concludes with some bitterness, “leads us to doubt the credibility of her written and oral statements to this Committee more generally.” Aside from an interview published in the Times last September, Gino has not spoken publicly to the Anglophone media. In April, however, she sat down with a reporter, whom she had known since high school, from the Torinese daily La Stampa . In this interview, she no longer flogs the malicious-actor theory; instead, she argues that the anomalous data in one of the four papers were due to spammy survey responses, and that the report was compromised by the inability of the forensic team to examine the correct files on her hard drive. These explanations are difficult to square with the evidence, and it seems more or less inconceivable that anyone could come away from the report with the notion that Gino had been subjected to punitive sham proceedings. Yet, according to Gino, it was in part at the recommendation of an unnamed Harvard colleague that she decided to file the twenty-five-million-dollar defamation lawsuit. The Italian reporter asks, “On the 26th of April there’s the first court hearing. The judge will decide which parts of the suit will be dismissed and which will go to trial. Why did you decide to sue?” Gino replies, “The evening of June 13th, 2023, a Harvard professor was given instructions to tell me, ‘Hey, step aside, resign, it’s the best choice for you and your family.’ But she did the opposite. She bothered to read the twelve hundred and eighty-one pages and to ask herself some questions. She had her doubts, contacted me, and told me, ‘It seems like an injustice, you should resist, file a suit.’ That’s how it happened.” Gino doesn’t explain how this colleague obtained the report, which at the time almost no one had seen, although the idea that some emissary had been tasked with a diplomatic approach isn’t wholly far-fetched. (Harvard declined to comment on the facts of the case.) Still, the broader claim follows the pattern of her responses to the committee: the lawsuit, like the data manipulation, was apparently someone else’s fault. At a Boston courthouse, on the day of the hearing, I squeezed into an elevator alongside a large group of suited figures, all of them preternaturally dour. I turned to one of them and asked, “You’re Harvard’s lawyers, right?” He didn’t look at me or smile. “We’re Harvard’s lawyers,” he said. The courtroom, a windowless box laced with a vaguely acorn-like pattern in an autumnal palette, was empty, aside from Data Colada and the trio’s lawyer, Jeffrey Pyle. The Data Colada guys aren’t accustomed to formality; both Joe Simmons and Uri Simonsohn looked as though they’d briefly glanced at a YouTube tutorial before giving up and just looping their ties decoratively around their necks. Leif Nelson, who seemed more familiar with neckwear, wore a blazer over weathered black jeans and cap-toe leather sneakers. Pyle, who appeared not only professionally but personally incensed by the fact of the lawsuit, wore cufflinks. Gino filed in with a phalanx of counsel and sat alone, in the second row of the gallery. She looked wan in a loose cardigan over a greenish blouse, and took notes solemnly on a legal pad; her hair seemed slightly damp, as it tends to in her various TED -style appearances. Pyle’s oral arguments were short and to the point. When presented with evidence of purported fraud, he said, Gino “could have responded to this circumstance in the Marketplace of Ideas. . . . Instead, she has sued my clients for $25 million dollars, and for what? For identifying data anomalies to Harvard and writing publicly about those anomalies after, after Harvard confirmed that everything they said was right. The chilling effect of a lawsuit on science is obvious.” He continued, “A scientific disagreement isn’t a proper subject for a defamation claim. Courts and lawyers and juries . . . are ill-equipped to referee scientific controversies.” For Data Colada’s purposes, one of the major questions to be resolved was Gino’s position as a public figure, in which case her lawyers would have to prove that Data Colada acted with malice or reckless disregard for the truth. Gino’s original complaint, unfortunately for her, went out of its way to establish that her reputation precedes her: “Plaintiff is an internationally renowned behavioral scientist, author, and teacher. She has written over 140 academic articles, both as an author and as a co-author, exploring the psychology of people’s decision-making.” Now, however, Gino’s lawyer, Julie A. Sacks, described all this as merely a description of a bog-standard academic. Judge Joun, who spent most of the hearing trying to stifle a yawn, seemed indisposed to this argument, interrupting to say, “We have a little bit more than that here. The complaint itself describes her as an internationally renowned scientist.” As she continued, Sacks did her client no favors. In her attempt to establish that Data Colada had published its blog posts with a reckless disregard for the truth, Sacks misquoted something that Simonsohn had said in a Webinar the previous summer. Pyle rose to correct the record. In closing, Pyle referred to a recent case in the Southern District of New York, in which a group of scientists stood accused of defamation for the claim that there was something amiss in the F.D.A. trial data for an Alzheimer’s drug. The judge in that case had thrown out the defamation claim on the ground that scientific disagreements were scientific disagreements. When Sacks led an ashen Gino out of the courtroom, she didn’t turn, as is common, to shake the hands of any of the other lawyers. (Gino declined to comment on the facts of the case while it was ongoing.) But one of her lawyers has noted that the team was “pleased that Professor Gino’s story was shared in a venue where process is upheld and evaluated in a full and fair manner,” adding, “Professor Gino’s case is strong and the facts support her innocence against these unfounded claims. Professor Gino’s reputation has been tarnished by this unfair process and we hope this case can help set the record straight.”) Last fall, I attended the high-profile fraud trial of Sam Bankman-Fried . Although that case, in the end, was legally simple—the jury found that Bankman-Fried had misappropriated customer funds and then repeatedly lied about it—it was, and remains, intellectually and morally complex. What role, for example, did Bankman-Fried’s commitment to utilitarianism play in his calculations? The Gino hearing—that of an extremely successful dishonesty researcher accused of having conducted her research dishonestly—augured something similarly invigorating. But, as it was, there appeared little to be learned aside from the fact that even once you take away someone’s shovel they will look down at their hole and use their bare hands to keep digging. The proceedings seemed terminally petty, an embarrassing dissipation of everyone’s time and resources. It was hard not to take the whole thing as evidence that a peerage of researchers had somehow been overcome by a cartel of litigants, a scientific culture easily derailed by the vanity and entitlement of the wealthy. Administrative bloat already threatens to turn the professoriate into a university rump; a case like this, in which one aggrieved actor plays to the refs of not merely the managerial bureaucracy but of the state itself, only further undermines the necessary defense of academic autonomy. About two weeks after the hearing, the Data Colada team posted an update to their blog. They used, as an illustration, an A.I.-generated image in the sepia-toned style of a lurid mid-century courtroom drama: the three of them and their lawyer, now with fitted suits and ties knotted properly, solemnly enjoying their namesake fruity cocktails in front of a packed gallery. They hoped that the case would be dismissed. But, they continued, “if the case is not dismissed, then we go to discovery.” A lot of new data would emerge. In that eventuality, they concluded, with barely suppressed gaiety, “it is possible we would discover things that merit an additional blog post.” The court, it turned out, was operating on an academic calendar, and the summer passed with no news. In the early afternoon of September 11th, the judge at last issued his decision. Several of the counts against Harvard itself, which related to the terms of Gino’s employment contract, would be allowed to proceed, and seem unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. (After the decision came out, one of Gino’s lawyers said, “Today’s decision clearly demonstrates Harvard treated Professor Gino differently from other misconduct investigations and their own stated policies. . . . We are pleased with the court’s decision to allow this litigation to continue and that Harvard will have to answer for how they have destroyed her career and put every member of the Harvard faculty at risk.” Harvard did not respond to a request for comment on the ruling.) The judge agreed, however, with Pyle’s arguments on behalf of Data Colada; he suggests that even a casual reading of their blog posts, which were never presented as anything but their reasonable opinion of the integrity of Gino’s work, rendered the defamation claims spurious. As the judge put it, “the sum effect of the blog posts makes plain that they represent the Data Colada Defendants’ subjective interpretation of the disclosed facts.” Science, in other words, could remain in the trust of scientists. All of the counts against them were dismissed. New cases, one can unfortunately presume, awaited them. ♦ New Yorker FavoritesThey thought that they’d found the perfect apartment. They weren’t alone . The world’s oldest temple and the dawn of civilization . What happened to the whale from “Free Willy.” It was one of the oldest buildings left downtown. Why not try to save it ? The religious right’s leading ghostwriter . After high-school football stars were accused of rape, online vigilantes demanded that justice be served . A comic strip by Alison Bechdel: the seven-minute semi-sadistic workout . Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .   |

COMMENTS

Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful. Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria. Step 6: Implementation plan.

Read and analyze the case. Each case is a 10-20 page document written from the viewpoint of a real person leading a real organization. In addition to background information on the situation, each case ends in a key decision to be made. ... Harvard Business School Spangler Welcome Center (Spangler 107) Boston, MA 02163 Phone: 1.617.495.6128

The Case Analysis Coach is an interactive tutorial on reading and analyzing a case study. The Case Study Handbook covers key skills students need to read, understand, discuss and write about cases. The Case Study Handbook is also available as individual chapters to help your students focus on specific skills.

In The Case Study Handbook, Revised Edition, William Ellet presents a potent new approach for efficiently analyzing, discussing, ... Teaching notes are available as supporting material to many of the cases in the Harvard Chan Case Library. Teaching notes provide an overview of the case and suggested discussion questions, as well as a roadmap ...

How to Analyze a Case. By: William Ellet. A case is a text that refuses to explain itself. How do you construct a meaning for it? This chapter discusses in depth a case situation approach that identifies features of a case that can be…. Length: 19 page (s) Publication Date: Apr 17, 2007. Discipline: Teaching & the Case Method.

It's been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students ...