Search by category

Popular searches.

Eating disorder case study

Discover another eating disorder recovery story

"eating disorders tend to hide and they don't want to be seen, and if somebody else can see it ... it's a lot harder to hide".

Contact us to make an enquiry or for more information

Antonella: ‘A Stranger in the Family’—A Case Study of Eating Disorders Across Cultures

- Open Access

- First Online: 12 December 2020

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Vincenzo Di Nicola 6 , 7

8115 Accesses

2 Citations

7 Altmetric

The story of Antonella illustrates the way in which cultural and other values impact on the presentation and treatment of eating disorders. Displaced from her European home culture to live in Canada, Antonella presents with an eating disorder and a fluctuating tableau of anxiety and mood symptoms linked to her lack of a sense of identity. These arose against a background of her adoption as a foundling child in Italy and her attachment problems with her adoptive family generating chronically unfixed and unstable identities, resulting in her cross-cultural marriage as both flight and refuge followed by intense conflicts. Her predicament is resolved only when after an extended period in cultural family therapy she establishes a deep cross-species identification by becoming a breeder of husky dogs. The wider implications of Antonella’s story for understanding the relationship between cultural values and mental health are briefly considered.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Overlaps and Disjunctures: A Cultural Case Study of a British Indian Young Woman’s Experiences of Bulimia Nervosa

René girard and the mimetic nature of eating disorders, the rise of eating disorders in asia: a review.

- Eating disorders

- Anorexia multiforme

- Cultural values

- Uniqueness of the individual

- Role of animals

- Cross-species identification

- Cultural family therapy

1 Introduction

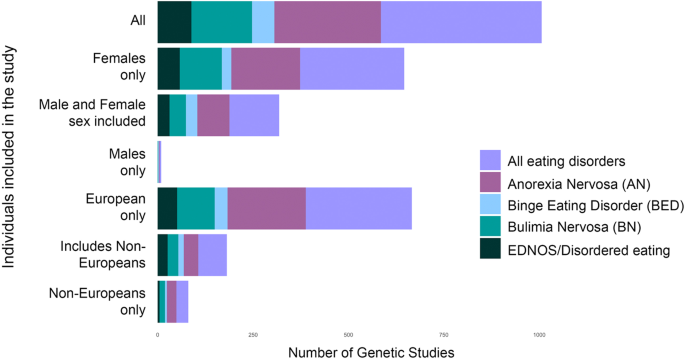

Eating disorders are a potentially fruitful area of study for understanding the links between values—in particular cultural values—and mental distress and disorder. Eating disorders show widely different prevalence rates across cultures, and much attention has been given to theories linking these differences with variations in cultural values. In particular, the cultural value placed on ‘fashionable slimness’ in the industrialised world has for some time been identified with the greater prevalence of eating disorders among women in Western societies [ 1 ]. Consistently with this view, the growing prevalence of eating disorders in other parts of the world does seem to be correlated with increasing industrialisation [ 2 , 3 ]. In my review of cultural distribution and historical evolution of eating disorders , I was so struck by its protean nature and its variability of clinical presentations of anorexia nervosa that I renamed this predicament ‘anorexia multiforme’ [ 4 , 5 ].

The story of Antonella that follows illustrates the potential importance of contemporary theories linking cultural values with eating disorders though also some of their limitations.

2 Case Narrative: Antonella’s Story

Ottawa in the early 1990s. Antonella Trevisan, a 24-year-old woman, was referred to me by an Italian psychiatrist and family therapist, Dr. Claudio Angelo, who had treated her in Italy [ 6 ] . When Antonella came to Canada to live with a man she had met through her work, Dr. Angelo referred her to me. Antonella’s presenting problems concerned two areas of her life: her eating problems, which emerged after her emigration from Italy, and her relationship with her partner in Canada.

2.1 Antonella’s Predicament

My initial psychiatric consultation (conducted in Italian) revealed the complexities of Antonella’s life. This was reflected in the difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis. Her food-related problems had some features of eating disorders , such as restriction of intake, the resulting weight loss, and a history of weight gain and being teased for it. What was missing was the ‘psychological engine’ of an eating disorder: a drive for thinness or a morbid fear of fatness. Her problem was perhaps better understood as a food-related anxiety arising from a ‘globus’ sensation (lump in the throat) and a learned avoidance response that generalized from one specific situation to eating in any context.

Although it was clear that her weight gain in late adolescence and the teasing and insults from her mother had sensitized her, other factors had to be considered. Antonella showed an exquisite rejection sensitivity that both arose from and was a metaphor for the circumstances of her birth and adoption. Her migration to Canada also seemed to generate anxieties and uncertainties, and there were hints of conflicts with her partner. Was she also re-enacting another, earlier trauma? In the first journey of her life, she was given up by her birth mother (or taken away?) and left on the steps of a foundry. In the first year of her life, Antonella had shown failure to thrive and developmental delays. And she had, at best, an insecure attachment to her adoptive family, predisposing her to lifelong insecurities.

2.2 A Therapeutic Buffet

After my assessment, we faced a choice: whether to treat the eating problem concretely, in purely behavioral terms, or more metaphorically, with some form of psychotherapy. Given the stabilization of her eating pattern and her weight and the larger context of her predicament, we negotiated to do psychotherapy. There were several components to her therapy. Starting with a psychiatric consultation, three types of therapy were negotiated, with Antonella sampling a kind of ‘therapeutic buffet’ over a period of some 2 years: individual therapy for Antonella, couple therapy for Antonella and Rick, and brief family therapy with Antonella’s adoptive family visiting from Italy.

The individual work with Antonella was at first exploratory, getting to know the complex bicultural world of the Italian Alps, how she experienced the move to Canada, examining her choices to move here and live with Rick. Sessions were conducted in a mix of Italian and English. At first, the Italian language was like a ‘transitional object’ in her acculturation process; slowly, as she gained confidence in her daily life, English began to dominate her sessions. Under stress, however, she would revert to Italian. I could follow her progress just by noting the balance of Italian and English in each session. This does not imply any superiority of English or language preferences; rather, it acknowledges the social realities of culture making its demands felt even in private encounters. This is the territory of sociolinguistics [ 7 , 8 ] . Like Italian, these individual sessions were a secure home base to which Antonella returned during times of stress or between other attempts to find solutions.

After some months in Canada and the stabilization of her eating problems, Antonella became more invested in examining her relationship to Rick. They had met through work while she was still in Italy. After communicating on the telephone, she daringly took him up on an offer to visit. During her holiday in Canada, a romance developed. After her return to Italy, Antonella made the extraordinary decision to emigrate, giving up an excellent position in industry, leaving her family for a country she did not know well. Rick is 22 years her senior and was only recently separated from his first wife.

In therapy she not only expressed ambivalence about her situation with Rick but enacted it. She asked for couple sessions to discuss some difficulties in their relationship. Beyond collecting basic information, couple sessions were unproductive. While Rick was frank about his physical attraction to her and his desire to have children, Antonella talked about their relationship in an oddly detached way. She could not quite articulate her concerns. As we got closer to examining the problems of their relationship, Antonella abruptly announced that they were planning their wedding. The conjoint sessions were put on hold as they dealt with the wedding arrangements.

Her parents did not approve of the marriage and boycotted the wedding. Her paternal aunt, however, agreed to come to Canada for the wedding. Since I was regarded by Antonella as part of her extended family support system, she brought her aunt to meet me. It gave me another view of Antonella’s family. Her aunt was warm and supportive of Antonella, trying to smooth over the family differences. A few months later, at Christmas time, her parents and sister visited, and Antonella brought them to meet me. To understand these family meetings, however, it is necessary to know Antonella’s early history.

2.3 A Foundling Child

Antonella was a foundling child. Abandoned on the steps of a foundry in Turin as a newborn, she was the subject of an investigation into the private medical clinics of Turin. This revealed that the staff of the clinic where she was born was ‘paid off to hide the circumstances of my birth.’ As a result, her date of birth could only be presumed because the clinic staff destroyed her birth records. She was taken into care by the state and, as her origins could not be established, she was put up for adoption.

Antonella has always tried to fill in this void of information with meaning that she draws from her own body. She questions me closely: ‘Just look at me. Don’t you think I look like a Japanese?’ She feels that her skin tone is different from other Italians, that her facial features and eyes have an ‘Asian’ cast. With a few, limited facts, and some speculation, she has constructed a personal myth: that she is the daughter of an Italian mother from a wealthy family (hence her hidden birth in a private clinic) and a Japanese father (hence her ‘Asian’ features). It is oddly reassuring to her, but also perhaps a source of her alienation from her family.

At about 6 months of age, Antonella was adopted into a family in the Italian Alps, near the border with Austria. This is a bicultural region where both Italian and German are spoken and services are available in both languages (much like Ottawa, which is bilingually English and French). Her father, Aldo, who is Italian, is a retired FIAT factory worker. Annalise, her mother, who is a homemaker, had an Italian father and an Austrian mother. About her family she said, ‘I had a wonderful childhood compared to what came afterwards.’ Years after her adoption, her parents had a natural child, Oriana, who is 15.

She describes her mother as the disciplinarian at home. Her mother, she said, was ‘tough, German.’ When she visited her Austrian grandmother, no playing was allowed in that strict home. Her own mother allowed her ‘no friends in the house,’ but her father ‘was my pal when I was a kid.’ Although she had a good relationship with her father, he became ‘colder’ when she turned 13. Her parents’ relationship is remembered as cordial, but she later learned that they had many marital problems. Mother told her that she married to get away from home, but in fact she was in love with someone else. Overall, the feeling is of a rigid family organization. Her father is clearly presented by Antonella as warmer and more sociable. She experiences her mother as being ‘tough’. But she is crying all the time, feeling betrayed by everybody.

2.4 A Family Visit from the Italian Alps

When her family finally came to visit, Antonella brought them to see me. At first, the session had the quality of a student introducing out-of-town parents to her college teacher. They were pleased that I spoke Italian and knew Dr. Angelo, who they trusted. I soon found that the Trevisans were hungry to tell their story. Instead of a social exchange of pleasantries, this meeting turned into the first session of an impromptu course of brief family therapy.

Present were Antonella’s parents, Aldo and Annalise, and her sister, Oriana. Annalise led the conversation. Relegating Aldo to a support role. Oriana alternated between disdain and agitation, punctuated by bored indifference. Annalise had much to complain about: her own troubled childhood, her sense of betrayal and abandonment, heightened by Antonella’s departure from the family and from Italy. I was struck by the parallel themes of abandonment in mother and daughter. Mother clearly needed to tell this story, so I tried to set the stage for the family to hear her, what narrative therapists call ‘recruiting an audience’ [ 9 ] . I used Antonella, who I knew best, as a barometer of the progress of the session, and by that indicator, believed it had gone well.

When I saw them again some 10 days later, I was stunned by the turn of events. Oriana had assaulted her parents. The father had bandages over his face and the mother had covered her bruises with heavy make-up and dark glasses. Annalise was very upset about Oriana, who was defiant and aggressive at home. For her part, Oriana defended herself by saying she had been provoked and hit by her mother. Worried by this dangerous escalation, I tried to open some space for a healthy standoff and renegotiation.

Somehow, the concern had shifted away from Antonella to Oriana. Antonella was off the hook, but I waited for an opening to deal with this. I first tried to explore the cultural attitudes to adolescence in Italy by asking how the Italian and the German subcultures in their area understood teenagers differently. What were Oriana’s concerns? Had they seen this outburst coming? The whole family participated in a kind of sociological overview of Italian adolescence, with me as their grateful audience. The parents demonstrated keen insight and empathy. Concerned about Oriana’s experience of the session, I made a concerted effort to draw her into it. Eventually, the tone of the session lightened. Knowing they would return to Italy soon, I explored whether they had considered family work. Since they had met a few times with Dr. Angelo over Antonella’s eating problems, they were comfortable seeing Dr. Angelo as a family to find ways to understand Oriana and her concerns and for Oriana to explore other, nonviolent ways to be heard in the family. I agreed to meet them again before their departure and to communicate with Dr. Angelo about their wishes. On their way out, I wondered aloud about the apparent switch in their focus from Antonella to Oriana. The parents reassured me that they were ready to let Antonella live her own life now.

When they returned to say goodbye, we had a brief session. Oriana and Antonella were oddly buoyant and at ease. The parents were relieved. Antonella had offered the possibility of Oriana returning to spend the summer in Canada with her. I tried to connect this back to the previous session, wondering how much the two sisters supported each other. I was delighted, I said emphatically, by the family’s apparent approval of Antonella’s marriage to Rick. It was striking that, even from a distance of thousands of miles away, Antonella was still a part of the Trevisan family. And Rick was still not in the room.

3 Discussion

In this section, I will consider the impact of cultural and other values on Antonella and those around her and then look briefly at the wider implications of her story for our understanding not only of eating disorders but of mental distress and disorders in general.

3.1 Antonella: Life Before Man

The key to understanding Antonella’s attachments was her passion for her Siberian huskies. In the language of values-based practice , it was above all her huskies that mattered or were important to her. And it is not hard to see why. From the beginning of her relationship with Rick, she used her interest in dogs as a way for them to be more socially active as a couple, getting them out of the house to go to dog shows, for example. As her interests expanded, she wanted to buy bitches for breeding and to set up a kennel. Rick was only reluctantly supportive in this. Nonetheless, they ended up buying a home in the country where she could establish a kennel. Her haggling with Rick over the dogs was quite instrumental on her part, representing her own choices and interests and a test of the extent to which Rick would support her.

Yet the importance to Antonella of her huskies rests I believe on deeper cultural factors, both negative and positive. As to negative factors , these are evident in the fact that from the first days of her life, Antonella was rejected by her birth parents, literally abandoned and exposed, and later adopted by what she experienced as a non-nurturing family. Positive cultural factors , on the other hand, are evident in the way that having thrown her net wider afield, she looked initially to Canada, and to Rick, for nurturance and for identity. Then, finding herself only partly satisfied, she turned to the nonhuman world for the constancy of affection she could not find with people. Her huskies gave her pleasure, a task, and an identity. She spent many sessions discussing their progress, showing me pictures of her dogs and their awards. As it happened, my secretary at the time was also a dog lover who raised Samoyed dogs (related to huskies) and the two of them exchanged stories of dog lore.

As to positive factors , again, is there something, too, in the mythology of Canada that helps us understand Antonella? Does Canada still hold a place in the European imagination as a ‘New World’ for radical departures and identity makeovers? Or does Canada specifically represent the ‘malevolent North,’ as Margaret Atwood [ 10 ] calls it in her exploration of Canadian fiction? Huskies are a Northern animal, close to the wolf in their origins and habits. Bypassing the human world, Antonella finds her identity within a new world through its animals. If people have failed her, then she will leave not only her own tribe (Italy), but skip the identification with Canada’s Native peoples, responding to the ‘call of the wild’ to identify with a ‘life before man’ (to use another of Atwood’s evocative phrases, [ 11 ]), finding companionship and solace with her dogs.

3.2 Wider Implications of Antonella’s Story

Antonella may seem on first inspection something of an outlier to the human tribe. Orphaned from her culture of origin, she finds her place not in another country but by identification with another and altogether wilder species, her husky dogs. Yet, understood through the lens of values-based practice Antonella’s story has, I believe, wider significance at a number of levels.

First, Antonella’s story is significant for our understanding of the role of values – of what is important or matters to the individual concerned – in the presentation and treatment of eating disorders , and, by extension, of perhaps many other forms of mental distress and disorder. Specifically, her story provides at least one clear ‘proof of principle’ example supporting the role of cultural values.

As noted in my introduction, much attention has been given in the literature to the correlations between the uneven geographical distribution of eating disorders and cultural values. Correlations are of course no proof of causation. But in Antonella’s story at least the role of cultural values seems clearly evident. They were key to understanding her presenting problems. And this understanding in turn proved to be key to the cultural family therapy [ 12 ] through which these problems were, at least to the extent of her presenting eating disorder, resolved.

The cultural values involved, it is true, were not those of fashionable slimness so widely discussed in the literature. But this takes us to a second level at which Antonella’s story has wider significance. For it shows that to the extent that cultural values are important in eating disorders , their importance plays out at the level of individually unique persons. In this sense, social stresses and cultural values are played out in the body of the individual suffering with an eating disorder, making her body the ‘final frontier’ of psychiatric phenomenology [ 13 ]. Yes, there are no doubt valid cultural generalisations to be made about eating disorders and mental disorders of other kinds. And yes, these generalisations no doubt include generalisations about cultural values—about things that matter or are important to this or that group of people as a whole. Yet, this does not mean that we can ignore the values of the particular individual concerned. It has been truly said in values-based practice that as to their values, everyone is an ‘ n of 1’ [ 14 ]. Antonella, then, in the very idiosyncrasies of her story, reminds us of the idiosyncrasies of the stories of each and every one of us, whatever the culture or cultures to which we belong.

Antonella’s identification with animals , furthermore, to come to yet another level at which her story has wider significance, was a strongly positive factor in her recovery. As with other areas of mental health, it is with the negative impact of cultural values that the literature has been largely concerned: the pathogenetic influences of cultural values of slimness being a case in point in respect of eating disorders . Antonella’s story illustrates what has been clear for some time in the ‘recovery movement’, that positive values are often the very key to recovery. Not only that, but as Antonella’s passion for her husky dogs illustrates, the particular positive values concerned may, and importantly often are, individually unique.

Not, it is worth adding finally, that Antonella’s values were in this respect entirely unprecedented. Animals , after all, are widely valued, positively and negatively, and for many different reasons, in many cultures [ 11 ]. Their healing powers are indeed acknowledged. Just how far these powers depend on the kind of cross-species identification shown by Antonella, remains a matter for speculation. But, again, her story even in this respect is far from unique. Elsewhere, I have described the story of a white boy with what has become known as the ‘Grey Owl Syndrome’ , wishing to be native [ 12 , chapter 5 ]. Similarly, in Bear , Canadian novelist Marion Engel [ 15 ] portrays Lou, a woman who lives in the wilderness and befriends a bear. Lou seeks her identity from him: ‘Bear, make me comfortable in the world at last. Give me your skin’ [ 15 , p. 106]. After some time with the bear, the woman changes: ‘What had passed to her from him she did not know…. She felt not that she was at last human, but that she was at last clean’ [ 15 , p. 137]. It was perhaps to some similarly partial resolution that Antonella came.

4 Conclusions

Antonella’s story as set out above goes to the heart of the importance of cultural values in mental health. Her presenting eating disorder develops when, displaced from her culture of origin in Italy, and in effect rejected by her birth family, she finds healing only through cross-species identification with the wildness of husky dogs in her adoptive country of Canada. Although somewhat unusual in its specifics, her story illustrates the importance of cultural values at a number of levels in the presentation and management of eating and other forms of mental distress disorder.

And Antonella? I met her again in a gallery in Ottawa, rummaging through old prints. She was asking about prints of dogs; I was looking for old prints of Brazil where my father had made a second life. How was she, I asked? ‘Well …,’ she said hesitantly. Was that a healthy ‘well’ or the start of an explanation? ‘Me and Rick are splitting up,’ she said without ceremony, ‘but I still have the huskies.’ For each of us, the prints represented another world of connections.

Makino M, Tsuboi K, Denerson L. Prevalence of eating disorders: a comparison of Western and non-Western countries. MedGenMed. 2004;6(3):49. Published online 2004 Sep 27 at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed .

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Erskine HE, Whiteford HA, Pike KM. The global burden of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):346–53.

Article Google Scholar

Selvini Palazzoli M. Anorexia nervosa: a syndrome of the affluent society. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1985;22( 3 ):199–205.

Google Scholar

Di Nicola VF. Overview: anorexia multiforme: self-starvation in historical and cultural context. I: self-starvation as a historical chameleon. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1990;27(3):165–96.

Di Nicola VF. Overview: anorexia multiforme: self-starvation in historical and cultural context. II: anorexia nervosa as a culture-reactive syndrome. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1990;27(4):245–86.

Andolfi M, Angelo C, de Nichilo M. The myth of atlas: families and the therapeutic story. Edited & translated by Di Nicola VF. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 1989.

Douglas M. Humans speak. Ch 11. In: Implicit meanings: essays in anthropology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1975. p. 173–80.

Crystal D. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

Parry A, Doan RE. Story re-visions: narrative therapy in the postmodern world. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Atwood M. Strange things: the malevolent north in Canadian literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Atwood M. Life before man: a novel. New York: Anchor Books; 1998.

Di Nicola VF. A stranger in the family: culture, families, and therapy. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; 1997.

Nasser M, Di Nicola V. Changing bodies, changing cultures: an intercultural dialogue on the body as the final frontier. Ch 9. In: Nasser M, Katzman MA, Gordon RA, editors. Eating disorders and cultures in transition. East Sussex: Brunner-Routledge; 2001. p. 171–93.

Fulford KWM, Peile E, Carroll H. A smoking enigma: getting and not getting the knowledge. Ch 6. In: Fulford KWM, Peile E, Carroll H, editors. Essential values-based practice: clinical stories linking science with people. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. p. 65–82.

Chapter Google Scholar

Engel M. Bear: a novel. Toronto: Emblem (Penguin Random House Books); 2009.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The story of Antonella was first published in reference [ 12 ] (pp. 214–220) and presented at the Advanced Studies Seminar of the Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice in Health and Social Care at St Catherine’s College, Oxford in October 2019. The names and other details of the case have been altered to maintain confidentiality. Parts of the discussion are adapted from that publication and the Oxford seminar. I am grateful to the publishers for permission to reproduce these materials here and to Professor Fulford and the members of the Advanced Studies Seminar for their stimulating exchanges. The subheading to the discussion of Antonella’s story (‘Life before Man’) was inspired by Margaret Atwood’s novel, Life Before Man [ 11 ].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Canadian Association of Social Psychiatry (CASP), World Association of Social Psychiatry (WASP), Department of Psychiatry and Addictions, University of Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Vincenzo Di Nicola

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vincenzo Di Nicola .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Medical University Plovdiv, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Drozdstoy Stoyanov

St Catherine’s College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Bill Fulford

Department of Psychological, Health & Territorial Sciences, “G. D’Annunzio” University, Chieti Scalo, Italy

Giovanni Stanghellini

Centre for Ethics and Philosophy of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Werdie Van Staden

Department of Psychiatry, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Michael TH Wong

Guide to Further Sources

For a more extended treatment of the role of culture in eating disorders and family therapy see:

Di Nicola VF (1990a) Overview: Anorexia multiforme: Self-starvation in historical and cultural context. I: Self-starvation as a historical chameleon. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 27(3): 165–196.

Di Nicola VF (1990b) Overview: Anorexia multiforme: Self-starvation in historical and cultural context. II: Anorexia nervosa as a culture-reactive syndrome. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 27(4): 245–286.

Di Nicola, V (1997) A Stranger in the Family: Culture, Families, and Therapy . New York & London: W.W. Norton & Co.

Nasser M and Di Nicola, V. (2001) Changing bodies, changing cultures: An intercultural dialogue on the body as the final frontier. In: Nasser M, Katzman M A, and Gordon R A, eds. Eating Disorders and Cultures in Transition . East Sussex, UK: Brunner-Routledge, pp. 171–193.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Di Nicola, V. (2021). Antonella: ‘A Stranger in the Family’—A Case Study of Eating Disorders Across Cultures. In: Stoyanov, D., Fulford, B., Stanghellini, G., Van Staden, W., Wong, M.T. (eds) International Perspectives in Values-Based Mental Health Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47852-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47852-0_3

Published : 12 December 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-47851-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-47852-0

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Toward a biological, psychological and familial approach of eating disorders at onset: case-control anobas study.

- 1 Department of Biological and Health Psychology, School of Psychology, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- 2 Department of Cognitive Psychology, School of Psychology, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- 3 Immunonutrition Research Group, Department of Metabolism and Nutrition, Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition (ICTAN), Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Madrid, Spain

- 4 Pediatric Pneumology, Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital, Madrid, Spain

- 5 Psychiatry Service, Hospital Universitario del Sureste, Arganda del Rey, Spain

- 6 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital, Madrid, Spain

- 7 CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain

Eating disorders (ED) are considered as heterogeneous disorders with a complex multifactor etiology that involves biological and environmental interaction.

Objective: The aim was to identify specific ED bio-psychological-familial correlates at illness onset.

Methods: A case-control (1:1) design was applied, which studied 50 adolescents diagnosed with ED at onset (12–17 years old) and their families, paired by age and parents’ socio-educational level with three control samples (40 with an affective disorder, 40 with asthma, and 50 with no pathology) and their respective families. Biological, psychological, and familial correlates were assessed using interviews, standardized questionnaires, and a blood test.

Results: After performing conditional logistic regression models for each type of variable, those correlates that showed to be specific for ED were included in a global exploratory model ( R 2 = 0.44). The specific correlates identified associated to the onset of an ED were triiodothyronine (T3) as the main specific biological correlate; patients’ drive for thinness, perfectionism and anxiety as the main psychological correlates; and fathers’ emotional over-involvement and depression, and mothers’ anxiety as the main familial correlates.

Conclusion: To our knowledge, this is the first study to use three specific control groups assessed through standardized interviews, and to collect a wide variety of data at the illness onset. This study design has allowed to explore which correlates, among those measured, were specific to EDs; finding that perfectionism and family emotional over-involvement, as well as the T3 hormone were relevant to discern ED cases at the illness onset from other adolescents with or without a concurrent pathology.

Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are severe psychiatric disorders characterized by pathological attitudes and behaviors related to food. All of them share a common major characteristic: the over-evaluation of shape and weight, and their control. Other common traits are body dissatisfaction and a persistent desire for thinness, which are present throughout the course of the illness [ American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013 ]. EDs usually begin in early adolescence, being the most frequent diagnosis among adolescents in mental health inpatient units and the third most common chronic illness in female adolescents ( Nicholls et al., 2011 ). Although previous studies have expanded our knowledge about risk factors associated with ED, few have been able to answer whether those risk factors were general or specific to ED psychopathology ( Fairburn et al., 1999 ; Pike et al., 2008 ; Machado et al., 2014 ; Gonçalves et al., 2016 ).

Regarding biological variables, pubertal status, excess body fat mass, and fluctuations in weight are factors associated with ED ( Bakalar et al., 2015 ). Changes in biological variables have been broadly related to homeostatic adaptations to malnutrition, although previous studies have also proposed that some of these, such as appetite-regulating hormones, also contribute to the development and maintenance of different behaviors related to ED ( Monteleone and Maj, 2013 ; Misra and Klibanski, 2014 ). Peripheral signals, such as fat mass derived hormones and gastrointestinal peptides may act on the central nervous system to influence eating behaviors, energy balance, and mood. In addition, the interactions between leptin, cortisol, and cytokine levels appear to be important mediators in an ED onset and its course, but their true relevance as primary or secondary alterations is mostly unknown ( Elegido et al., 2017 ).

Regarding psychological variables, multiple studies have identified perfectionism as one of the most relevant risk factors of this population ( Culbert et al., 2015 ). Another well-known risk factor for ED is negative affectivity ( Dakanalis et al., 2017 ) which has been shown to persist even after recovery ( Klump et al., 2000 ). However, whereas Fairburn et al. (1999) and Stice (2002) identified perfectionism and negative affectivity as specific risk factors for ED, another study considered perfectionism as a correlate and negative affectivity as a non-specific risk factor ( Jacobi et al., 2004 ). Body dissatisfaction was also found to be an important predictor of ED ( Stice et al., 2011 ; Jacobi and Fittig, 2012 ). Related to it, shape and weight concern has been confirmed as one of the most potent factors for the onset of an ED ( Keel and Forney, 2013 ).

On the other hand, different familial factors have been identified, such as familial pressure and discord ( Fairburn et al., 1999 ; Pike et al., 2008 ), teasing ( Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007 ), negative perception of parental attitudes ( Kluck, 2010 ; Parks et al., 2017 ), high expressed emotion, and family history of ED ( Sepúlveda et al., 2012 , 2014 ; Hilbert et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, other authors ( Le Grange et al., 2010 ; Machado et al., 2014 ) have found that familial factors, except family history of ED, were non-specific factors as they were related to increased risk of general psychopathology. Moreover, one of the inherent difficulties of research on familial risk factors of ED is the overrepresentation of mothers’ data, as analyzing the contribution of each parent separately could improve the knowledge about the whole family system ( Anastasiadou et al., 2014 ; Gonçalves et al., 2016 ).

Previous ED etiological models have agreed that the etiology is complex, and includes biological, psychological, and socioenvironmental factors interacting at the onset and maintenance of the ED ( Treasure et al., 2008 , 2020 ). The aim of this article was to identify specific biological, psychological, and familial ED correlates associated with the onset of the disorder. Following the Kraemer et al. (1997) ’s risk factors classification, correlates are the kind of factors that cannot demonstrate precedence over the outcome. To evaluate the specificity of these correlates, three control samples were chosen: affective disorders (AD group), asthma pathology (AP group), and a non-pathological group (NP group). EDs present high comorbidity with affective disorders ( Ferreiro et al., 2011 ), suggesting that common and specific ED factors could be pointed out. Asthma sufferers present similarities on the familial level, as both disorders are considered chronic psychosomatic diseases, present severe attacks, which can be life-threatening, and pose high demands of care representing a significant impact on the physical and psychological wellbeing of the families ( Theodoratou-Bekou et al., 2012 ; Verkleij et al., 2015 ). A control group without pathology was selected in order to control the role of the adolescence as an important risk factor for an ED ( Keel and Forney, 2013 ). Consistent with the scientific literature, we hypothesized that some biological correlates (biochemical, neuroendocrine, and immunological), some psychological correlates (attitudes and behaviors related to eating psychopathology, body dissatisfaction, perfectionism and anxious, depressive, and obsessive symptomatology), and some familial correlates (family functioning, expressed emotion and anxious, depressive, and obsessive symptomatology) were specific correlates associated with the onset of an ED. We also hypothesized that an exploratory bio-psycho-familiar model based on these specific correlates would allow to identify the ED group.

Materials and Methods

Design and procedure.

The current research follows a cross-sectional case-control design, using an ED group as the case group and matching with three control groups by sex and age of the patients and socioeconomic status of the parents, following the Hollingshead Redlich Scale ( Hollingshead and Redlich, 1953 ). A complete sample description of the ANOBAS protocol and a detailed explanation of the suitability of the study control groups is provided in Sepulveda et al. (2021) .

The recruitment was carried out during 4 years. Firstly, the ED sample was recruited at the outpatient Eating Disorders Unit at the Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital in Madrid, Spain. The samples for the three control groups was then recruited, in order to match the characteristics of each ED adolescent (1:1). The AD sample was recruited at different Mental Health Centers in the Community of Madrid. In both psychiatric groups, patients had been diagnosed by mental health professionals. In addition, AP participants were recruited at the Pneumology Department at the Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital and the NP group was recruited at different schools in the Community of Madrid. Short telephone interviews were conducted to confirm the sociodemographic variables, and once informed written consent was obtained from adolescents and their parents, the cases were matched. The first assessment included a socio-demographic interview, a semi-structured psychiatric interview to confirm the previous diagnoses and to assess new possible comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, and a battery of questionnaires for both parents and daughters. Participants had 1 week to complete the questionnaires. This assessment was followed by a full blood test. The blood sample was collected at the Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital and evaluated by the Immunonutrition Group at the Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition (ICTAN-CSIC). Fasting venous blood samples were collected between 8 and 9 AM from patients and controls in an EDTA-K3E Vacutainer (BD Biosciences) tubes. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation during 15 min at 1,300 g and 4°C. Aliquots were frozen at −80°C until analysis.

Confidentiality was guaranteed for all the participants. The study received ethical approval by the Hospital Ethics Committee (Ref. Code, R-0009/10), and the corresponding University Research Ethics Committee (UAM, CEI 25-673).

Participants

The sample was made up by 180 females, with ages between 12 and 17 years, and their parents. Four groups were recruited: 50 adolescents diagnosed with an ED at onset of the illness, 40 adolescents diagnosed with an affective disorder at onset (AD group), 40 adolescents diagnosed with severe asthma pathology (AP group), and 50 adolescents without a pathology (NP group). Depending on the sample, data was collected from between 30 and 40 fathers, and 40 and 50 mothers.

Exclusion criteria for all groups were to suffer any metabolic conditions known to influence Body Mass Index (BMI) or a psychotic disorder, and for the three control groups, to present an ED or a BMI above 30 or below 17.5. Inclusion criteria for the ED and AD group were to present an early stage of the illness at first diagnosis (a year or less of illness duration). Inclusion criteria for the AD group were to present a diagnosis of an affective disorder without ED diagnosis. Inclusion criteria for the AP group were to have been diagnosed before the age of 7 with asthma and to have visited at least three times an emergency service, which allowed us to select more severe asthma cases. Overall, nine participants were excluded from the study after the assessment because of co-occurrence of ED and AD ( n = 2), co-occurrence of ED or AP ( n = 2), presence of psychosis ( n = 1), presence of a metabolic disorder ( n = 1), and ED pathology in the NP group ( n = 3). All of the excluded participants were not considered for matching.

Regarding the sample size, taking into account weight concerns assessed through the Eating Disorders Inventory ( Garner, 1991 ), considered as one of the most well-supported risk factor for ED, a mean effect size of AUC = 0.746 was found in one of the main reviews about risk factors in this pathology ( Jacobi et al., 2004 ). Based on that mean effect size, the Cohen’s d was calculated ( d = 0.936). The G ∗ Power program was used in order to calculate the sample size needed to detect this effect, obtaining an estimated sample size per group of 27. Based on these suggestions, a sample size of 40 or 50 was considered enough to reach good effect sizes.

Diagnostic Assessment

Current and lifetime psychiatric disorders were evaluated with the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Interview (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997 ); a semi-structured interview developed to diagnose children and adolescents using DSM-IV diagnoses. Diagnoses were adapted to the DSM-5 [ American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013 ].

Biological Assessment

A physical examination and laboratory analysis of blood markers related to nutritional and immunological status were assessed, including the following types of variables:

(a) Anthropometric variables: weight, height, and BMI.

(b) Biochemical variables: alkaline phosphatase, total cholesterol, ferritin, vitamin B12, with automated analyzer using colorimetric and nephelometric techniques and by electric potential using a selective electrode (Na, K).

(c) Neuroendocrine and Immunological variables: free tetra-iodothyronine (T4), tri-iodothyronine (T3), cortisol, estradiol, insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF1), IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP3), complement component 3 (C3), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), leptin, soluble leptin receptor, adiponectin, by RIA, ELISA, and xMAP Technology for immunoassay of multiple analyses (Millipore).

Blood collected in EDTA-K3 vacumtainers was used for a lymphocyte subset analysis. Immediately after collection, 1 mL of blood was mixed with an equal volume (1 mL) of preservative solution and refrigerated for 2–6 days for processing and flow cytometry analysis. Unfortunately, due to budget limitations, the asthma group did not have their immunological variables measured.

Psychological Correlates Assessment

Each adolescent completed a battery of different instruments, which have shown adequate psychometric validity in Spanish adolescent samples (in the current study Cronbach α ranged between 0.81 and 0.98). Attitudes and behaviors related to eating psychopathology were assessed with the Eating Disorders Inventory-II (EDI-II; Garner, 1991 ). Body dissatisfaction was evaluated with the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ; Cooper et al., 1987 ). Depression was assessed with the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992 ); anxiety with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC; Spielberger et al., 1973 ) and obsessiveness with the Leyton Obsessional Inventory-Child Version (LOI-CV; Berg et al., 1986 ). Lastly, we used the Child Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS; Flett et al., 2000 ) to evaluate perfectionism.

Familial Correlates Assessment

The parents of each participant completed a battery of five questionnaires. These measures have shown adequate psychometric validity across Spanish populations (in the current study Cronbach α ranged between 0.78 and 0.92). To evaluate the psychological well-being of the parents we used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961 ) to assess depressive symptoms, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Spielberger et al., 1970 ) to assess the level of anxiety, and the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002 ) to assess obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Regarding family functioning variables, we used the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES-II; Olson et al., 1982 ) to assess adaptability and cohesion, and the Family Questionnaire (FQ; Wiedemann et al., 2002 ) to evaluate critical comments (CC) and emotional over-involvement (EOI).

Data Analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed with R software.

Firstly, conditional logistic regressions were conducted for each risk factor using the survival package. Conditional logistic regressions compare each ED participant with her matching case-control participant from the AD, AP, and NP groups. More specifically, each ED participant was compared with a strata of her matching case-control AD, AP, and NP participants. Conditional logistic regressions were then conducted for each group of biological, psychological, and familial correlates where a stepwise model selection was applied to select the most relevant correlates in the model using the AIC indices of the MASS package. The statistical significance of individual correlates was corrected using Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. All the variables were standardized and no multicollinearity was observed, neither in biological, familial nor psychological models.

Secondly, the same conditional logistic regressions procedure was followed to estimate an exploratory bio-psycho-familial model. In this case, the complexity and the computational burden of the statistical model forced us to impute missing values by the mean of each group (missing patterns were isolated to specific cases, but listwise deletion inherent to conditional logistic regressions would considerably reduce the number of observations). In the bio-psycho-familial model, we only included those correlates that were previously conserved by stepwise model selections using the AIC indices. All the variables were standardized to estimate the bio-psycho-familial model because they had different score ranges. Finally, a stepwise model selection was applied in this model in order to determine the most relevant correlates to discriminate between ED and the control groups (AD, AP, and NP participants).

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

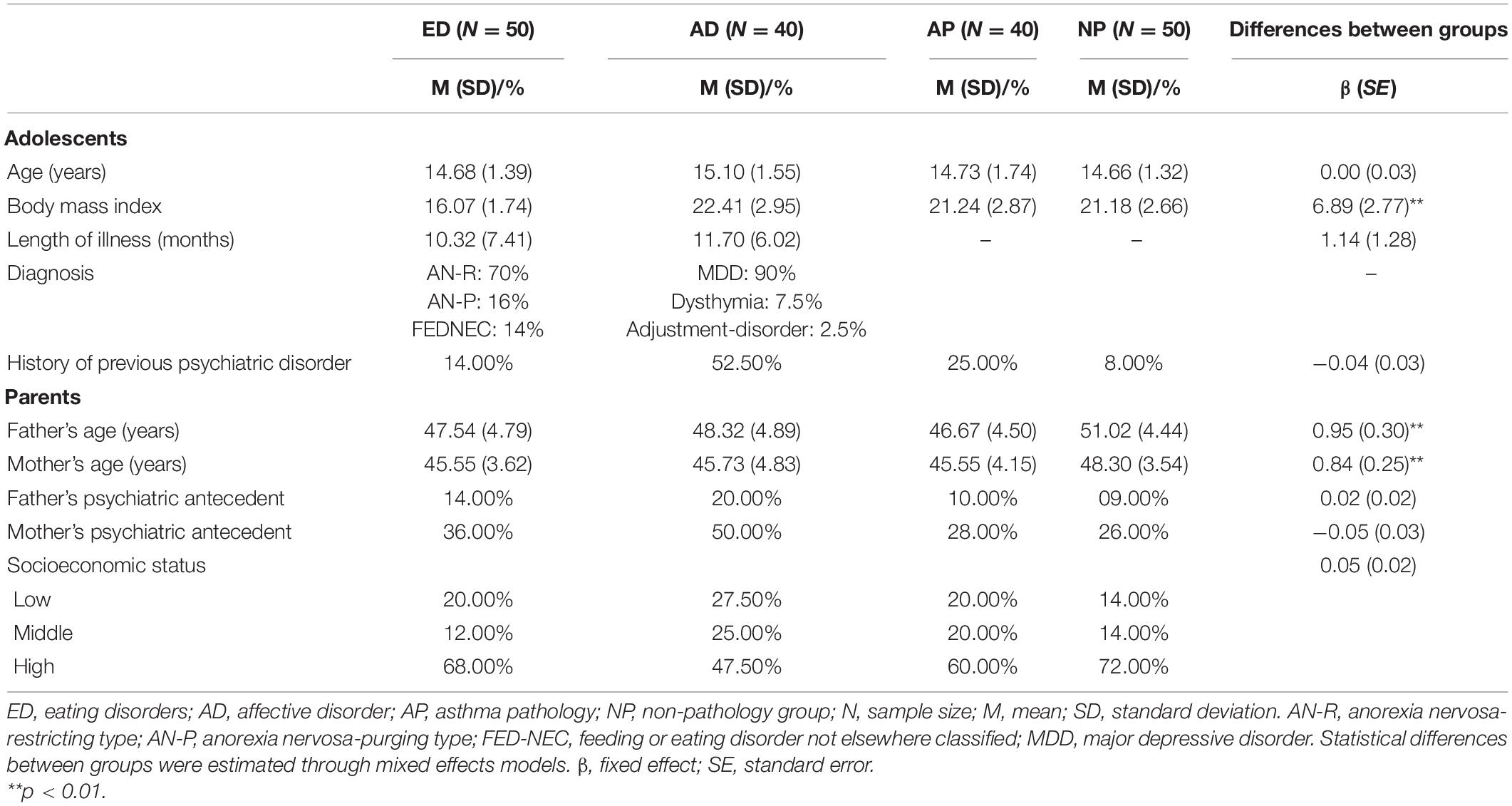

Participants’ sociodemographics are described in Table 1 , in which each control sample is compared with the ED sample. Given the design, no differences were found for participants’ age and socioeconomic status of the parents. In addition, no differences were found between the psychiatric groups (ED and AD) for illness duration. We only found statistically significant differences between the groups controlling by their case-control matching in the patients’ BMI. ED participants presented the following diagnoses: anorexia nervosa (AN) restrictive subtype (70%); AN purgative subtype (16%) and other specified feeding and eating disorder (14%). AD participants presented the following diagnoses: major depressive disorder (90%); dysthymia (7.5%); adjustment disorder with depressive symptoms (2.5%).

Table 1. Descriptive analyses of the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, and mixed-effects results to test the differences between case-control with individual matching.

Examining Biological Correlates for Eating Disorders

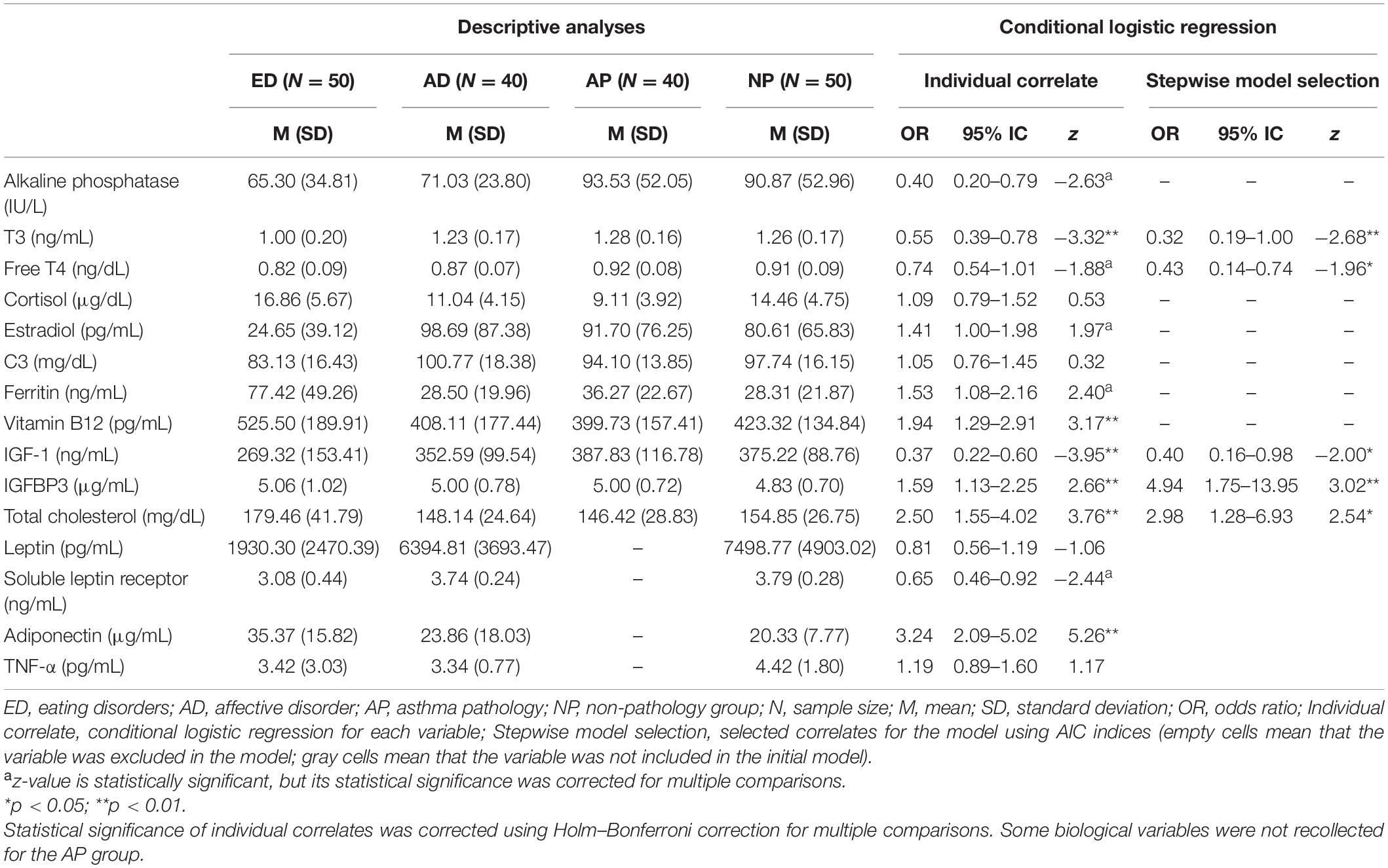

Conditional logistic regressions were computed for each biological correlate (see Table 2 ). Results showed that higher values of vitamin B12, IGFBP3, total cholesterol, and adiponectin were relevant to differentiate the ED group with the control groups. On the other hand, the reduced values of T3 and IGF-1 were also relevant to differentiate the ED group with the control groups.

Table 2. Descriptive analyses and conditional logistic regressions for biological correlates.

A conditional logistic regression was estimated using all of the biological correlates (except leptin, soluble leptin receptor, adiponectin, and TNF-α because they were not collected in the AP group) as covariates. Stepwise model selection showed that the most relevant variables to differentiate the ED group with the control groups were T3, free T4, IGF-1, IGFBP3, and total cholesterol.

Examining Psychological Correlates for Eating Disorders

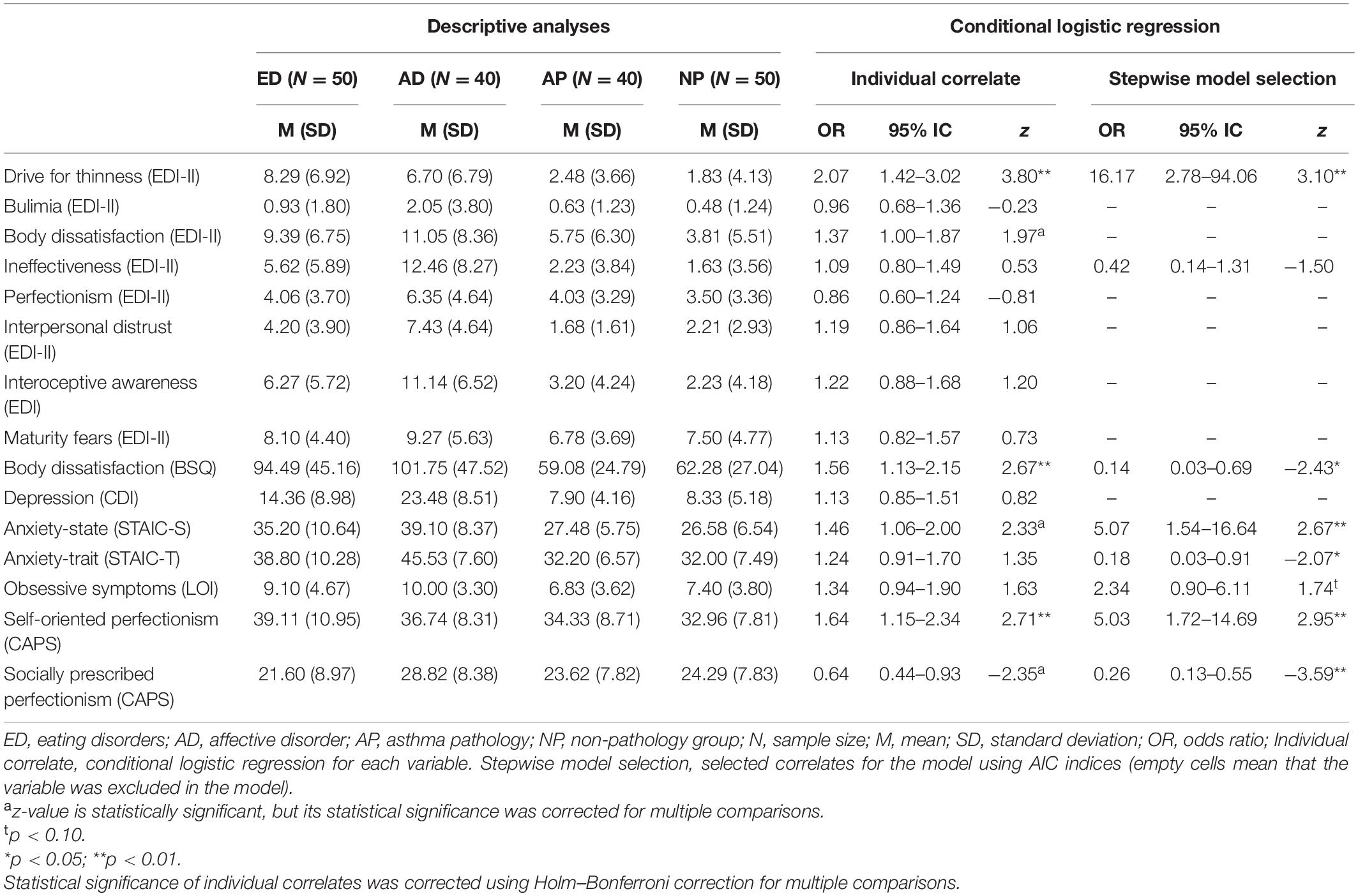

Conditional logistic regressions were computed for each psychological correlate (see Table 3 ). Results showed that the ED group reported more drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction (BSQ) and self-directed perfectionism than control groups.

Table 3. Descriptive analyses and conditional logistic regressions for psychological correlates.

Also, a conditional logistic regression was estimated using all of the psychological correlates as covariates. A stepwise model selection showed that patients with ED reported more drive for thinness, anxiety-state, obsessive symptoms, and self-oriented perfectionism. However, patients with ED reported less body dissatisfaction, trait-anxiety, and socially prescribed perfectionism than the control groups.

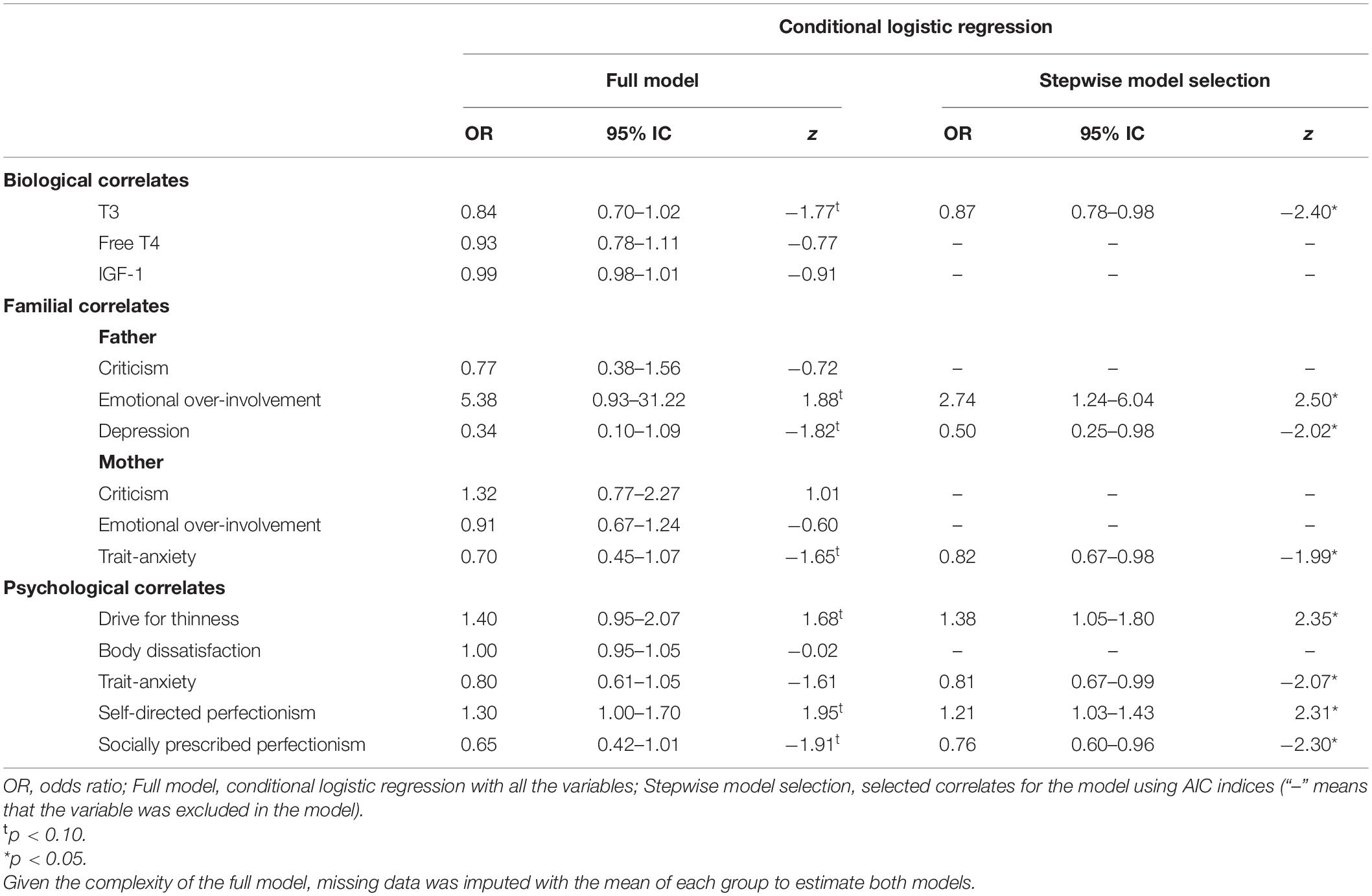

Examining Familial Correlates for Eating Disorders

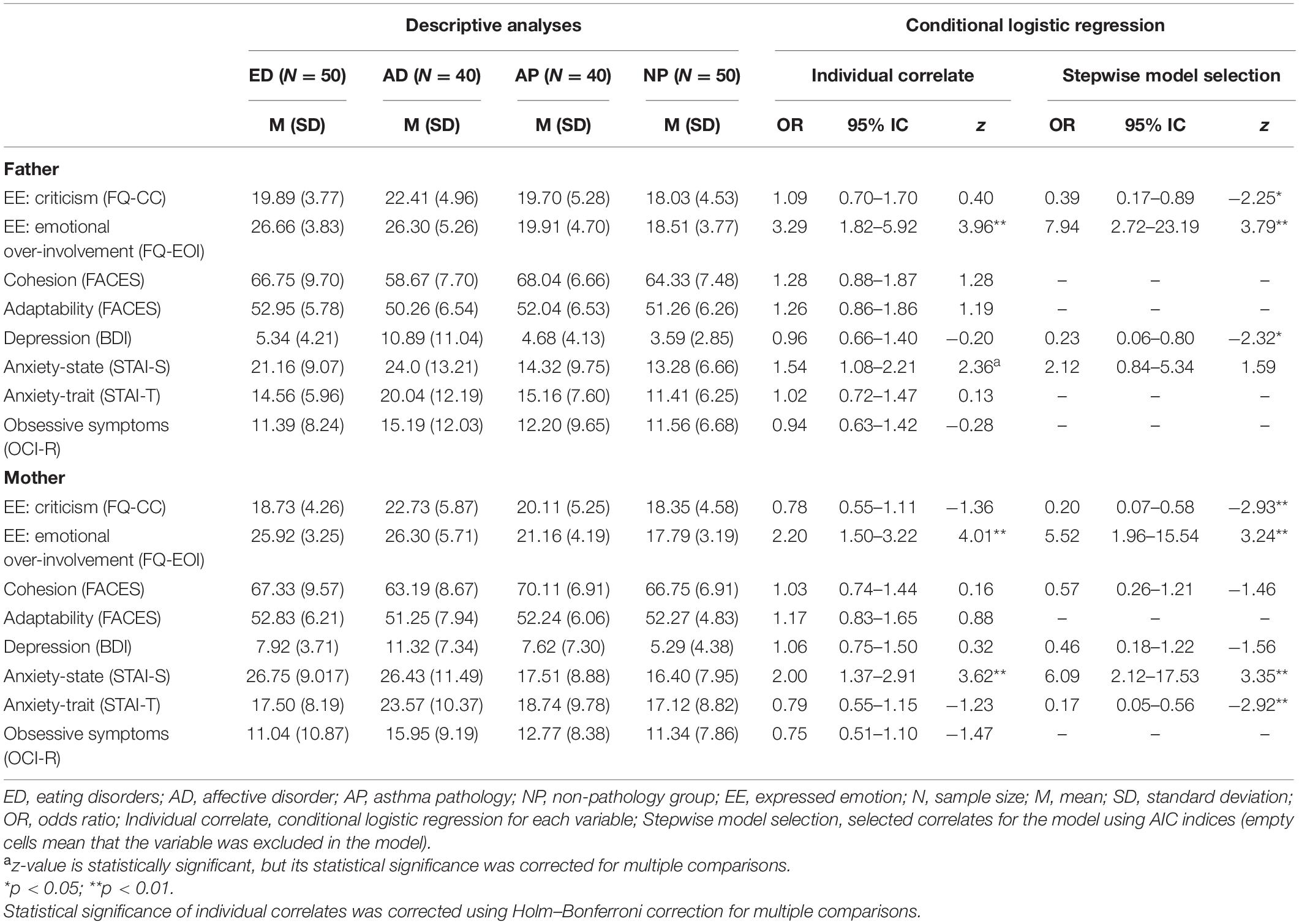

Conditional logistic regressions were computed for each familial correlate (see Table 4 ). Results showed that the ED group was more exposed to both fathers’ and mothers’ emotional over-involvement and mothers’ anxiety-state compared to the control groups.

Table 4. Descriptive analyses and conditional logistic regressions for family correlates.

A conditional logistic regression was then estimated using all the familial correlates as covariates. A stepwise model selection showed that patients with an ED were more exposed to fathers’ EOI, mothers’ EOI, and mother’s anxiety-state. However, patients with ED were less exposed to fathers’ criticism and mothers’ criticism, fathers’ depression, and mothers’ trait-anxiety than the control groups.

An Exploratory Bio-Psycho-Familial Model of Specific Correlates for Eating Disorders

Once all the relevant variables were selected in the previous analyses, a bio-psycho-familial model was estimated (see Table 5 ). The complexity and thus the computational burden of the full model forced us to remove total cholesterol, IGFBP3, and mothers’ state-anxiety from the full model. The most relevant variables of this full model were selected by a stepwise model selection using the AIC indices. This model was composed by biological, psychological and familial correlates that explained a considerable part of the variance of the dependent variable ( R 2 = 0.44). In the case of biological correlates, the reduction in T3 was relevant to differentiate between case-control groups. In the case of familial correlates, we found that the ED group was more exposed to fathers’ emotional over-involvement, and less exposed to fathers’ depression and mothers’ trait-anxiety, compared to control groups. In the case of psychological correlates, we found that the ED group reported more drive for thinness and self-oriented perfectionism, and that they reported less trait-anxiety and socially prescribed perfectionism, compared to the control groups.

Table 5. Conditional logistic regressions to determine a bio-psycho-familial model of correlates for eating disorders.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use three specific control groups, with standardized interviews for all the participants, collecting wide variety of data that included the capture of family functioning from both parents’ perspectives. Furthermore, ED patients were recruited at the onset of their illness, something that helped us to identify specific correlates associated with the development of an ED, in order to generate an exploratory bio-psychological-familial model.

Regarding biological variables, the biochemical variables vitamin B12 and total cholesterol, as well as the neuroendocrine variables T3, IGF1, IGFBP, and adiponectin, were relevant to differentiate the ED group with the control groups. However, when all the biological variables were considered conjointly, all these variables except vitamin B12 and adiponectin, appeared with free T4 to be the most relevant specific correlates associated with the onset of an ED. These are all endocrine variables directly related to energy availability for metabolic functions. T3 and Free T4 are usually low in AN patients in order to decrease energy requirements, while IGF-1 is a hormone produced in many cells in response to the growth hormone, it has widespread metabolic functions and is greatly involved in the adaptation to starvation ( Misra and Klibanski, 2014 ). IGF-1 has been shown to decrease in acute stages of AN, IGFBP-1 is increases, and IGFBP-3 levels are less clear. The high levels of cholesterol has been related to the decrease of T3 and T4 ( Matzkin et al., 2007 ; Himmerich et al., 2019 ). In addition, a trend toward the normalization of these molecules with anthropometrical recovery has been shown ( Støving et al., 2007 ). Thus, it appears that these molecules are good correlates to identify ED patients with a low BMI who have been recently diagnosed, and are, thus, under the effects of maintained restrictive behaviors. However, their usefulness as a potential predictor is low since their alteration is believed to be secondary to malnutrition.

The psychological correlates that have shown to be specific correlates for ED were drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and self-oriented perfectionism. However, when all the psychological variables were considered conjointly, the role of body dissatisfaction was not maintained and other correlates, such as obsessive symptoms, anxiety, and socially prescribed perfectionism, appeared as important correlates. Whereas body dissatisfaction was found as an important predictor for ED ( Stice et al., 2011 ), it could also act as a predictor for an affective disorder ( Ferreiro et al., 2011 ; Bornioli et al., 2021 ). In addition, their prevalence is high in adolescence ( Stice, 2002 ) and mainly in females ( Al Sabbah et al., 2009 ), and it appears to not be a specific correlate. Furthermore, other researchers’ findings underline the role of perfectionism in ED ( Fairburn et al., 1999 ; Pike et al., 2008 ; Machado et al., 2014 ), similar to our findings. Nevertheless, an important difference was found between self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism. Castro-Fornieles et al. (2007) found that self-oriented perfectionism was more specific for EDs and socially prescribed perfectionism appeared in similar levels in other psychiatric disorders.

On the other hand, emotional over-involvement of both parents and mother state-anxiety emerged as specific familial correlates for an ED. When all the familial variables were considered conjointly, the reduction of both parents’ criticism, fathers’ depression and mothers’ trait-anxiety appeared as specific correlates for ED. These results may suggest that psychological distress (characterized by severe depression and trait-anxiety) and high expressed emotion of family members may be associated with an ED, consistent with the review done by Zabala et al. (2009) . Likewise, the difference in the dimensions of expressed emotion is in accordance with the tendency of higher levels of EE-EOI compared to EE-CC in families with an ED, a finding which was reported by Anastasiadou et al. (2016) .

The exploratory bio-psychological-familial model showed that the increase of fathers’ EOI, patients’ drive of thinness and self-oriented perfectionism together with the decrease of T3, anxiety and socially prescribed perfectionism of the adolescents as well as the decrease of fathers’ depression and mothers’ anxiety were specifically associated to the onset of an ED. The fathers’ EOI appeared as a robust specific correlate, in contrast to a recent systematic review which proposed that mothers were more emotionally over-involved than fathers, who tend to be more critical ( Anastasiadou et al., 2014 ). However, in this review several studies did not include comparison groups. In our research, mothers of the AD group showed higher levels of emotional over-involvement as well as fathers for the AD group showed higher levels of criticism compared to parents with ED. It seems that in the ED group, fathers play an important role, which can differentiate this group from other control groups even better than mothers, suggesting that future research should include them in the assessment.

These results also contrast with the studies that have suggested that familial factors are non-specific factors for the onset of an ED ( Le Grange et al., 2010 ; Herpertz-Dahlmann et al., 2011 ; Machado et al., 2014 ). Indeed, some authors have emphasized the possibility that these factors would be an accommodation to the illness rather than predisposing factors that explain it ( Le Grange et al., 2010 ). Regardless of their role, expressed emotion is a potential prognostic indicator, that is stable in periods of up to 2 years and that predicts poor outcomes for treatment ( Peris and Miklowitz, 2015 ). Further studies are needed in order to clarify the role of familial correlates in ED.

In addition, the decrease of fathers’ levels of depression and mothers’ trait anxiety followed a similar tendency as the adolescents’ decreased in the trait-anxiety. Several studies have examined the similarities between the negative affectivity dimension and the factors measured by BDI or STAI scales, and have concluded that they should be considered as a measure of general negative affect ( Balsamo et al., 2013 ). Therefore, our findings do not support the centrality of negative affectivity as a specific correlate for ED, in concordance with similar recent studies that have considered it as a general psychopathological risk factor ( Jacobi and Fittig, 2012 ; Machado et al., 2014 ).

Lastly, two psychological variables, perfectionism and drive for thinness, and one biological variable, T3, appeared to be specific correlates associated with the onset of an ED. The literature broadly supports the role of these variables. Indeed, a recent study has revealed that Free-T3 is a specific and sensitive correlate in distinguishing constitutional thinness and AN groups, showing significantly lower values in the latter with similar BMI between groups ( Estour et al., 2017 ). Thus, although the low levels are thought to normalize with weight gain, evidence shows its relevance in AN patients and therefore, an early assessment in adolescents with a suspected ED is advisable.

The current study presents several limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional case-control nature of the study does not allow inferring causality. However, Jacobi et al. (2004) suggested that using a case-control study is a good way to analyze correlates in a wide sample that can then be contrasted in a longitudinal study. Secondly, we only considered patients with a maximum of a 1-year course in order to reduce bias due to retrospective recall, although some of them had a history of a previous psychiatric disorders. Consequently, the involvement of other informants, such as parents, is important to contrast the information given by the adolescents. Thirdly, females with high socioeconomic status were predominant in this sample. Although it may be a limitation for the generalization of the results, high socioeconomic status is also frequent in EDs ( Striegel-Moore and Bulik, 2007 ), and matching for parental socioeconomic status reduces differences in family experiences related to the availability of resources.

To summarize, this study proposes a complex model, which shows the importance of different correlates that are associated with the onset of an ED, although our findings require further research that can be contrasted in longitudinal studies and assessed in comparison with other control groups in order to confirm the specificity of the correlates. Most of the correlates found in this study are a replication of previously found risk factors in the literature, whereas the specificity and their relation have not been fully investigated. All of the participants have been assessed with reliable measures (blood test, clinical interview, and questionnaires). In our bio-psycho-familial model, eight correlates were specifically related to ED, therefore, the study confirms the importance of these three types of variables, which could be the target of future prevention and treatment interventions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by approval was granted by the Ethic Committee of the Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital (Ref Code. R-0009/10) and by the Autonomous University of Madrid Ethic Research Committee (UAM, CEI 25-673). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

AS, EN, AM, JV-A, EM, and MG contributed to conception and design of the study. DA, SG-M, and AM organized the database. JMH performed the statistical analysis. AM wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RYC-2009-05092 and PSI2011-23127) and the Education Ministry of Spain (FPU15/05783).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all the families, staff hospital, and psychiatrists from the Mental Health Centers who helped us in the recruitment process. Likewise, we are very grateful to the headmasters and teachers from this three Secondary Schools: IES La Estrella, IES Las Musas, and IES Alameda de Osuna, that facilitated the recruitment stage. We would finally like to express our gratitude to T. Alvarez, L. Gonzalez, and C. Bustos.

Al Sabbah, H., Vereecken, C. A., Elgar, F. J., Nansel, T., Aasvee, K., Abdeen, Z., et al. (2009). Body weight dissatisfaction and communication with parents among adolescents in 24 countries: international cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 9:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-52

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th Edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric.

Google Scholar

Anastasiadou, D., Medina-Pradas, C., Sepulveda, A. R., and Treasure, J. (2014). A systematic review of family caregiving in eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 15, 464–477. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.06.001

Anastasiadou, D., Sepulveda, A. R., Sánchez, J. C., Parks, M., Álvarez, T., and Graell, M. (2016). Family functioning and quality of life among families in eating disorders: a comparison with substance-related disorders and healthy controls. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 24, 294–303. doi: 10.1002/erv.2440

Bakalar, J. L., Shank, L. M., Vannucci, A., Radin, R. M., and Tanofsky-Kraff, M. (2015). Recent Advances in Developmental and Risk Factor Research on Eating Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 17:42. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0585-x

Balsamo, M., Romanelli, R., Innamorati, M., Ciccarese, G., Carlucci, L., and Saggino, A. (2013). The state-trait anxiety inventory: shadows and lights on its construct validity. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 35, 475–486. doi: 10.1007/s10862-013-9354-5

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., and Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 4, 561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

Berg, C. J., Rapoport, J. L., and Flament, M. (1986). The Leyton Obsessional Inventory-Child Version. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry 25, 84–91. doi: 10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60602-6

Bornioli, A., Lewis-Smith, H., Slater, A., and Bray, I. (2021). Body dissatisfaction predicts the onset of depression among adolescent females and males: a prospective study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 75, 343–348. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-213033

Castro-Fornieles, J., Gual, G., Lahortiga, F., Gila, A., Casulà, V., Fuhrmann, C., et al. (2007). Self-Oriented Perfectionism in Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 40, 562–658.

Cooper, P., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., and Fairbum, C. (1987). The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 6, 485–494. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405<3.0.CO;2-O

Culbert, K. M., Racine, S. E., and Klump, K. L. (2015). Research Review: what we have learned about the causes of eating disorders - A synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 56, 1141–1164. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12441

Dakanalis, A., Clerici, M., Bartoli, F., Caslini, M., Crocamo, C., Riva, G., et al. (2017). Risk and maintenance factors for young women’ s DSM-5 eating disorders. Arch. Womens. Ment. Health 20, 721–731. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0761-6

Elegido, A., Graell, M., Andrés, P., Gheorghe, A., Marcos, A., and Nova, E. (2017). Increased naive CD4+ and B lymphocyte subsets are associated with body mass loss and drive relative lymphocytosis in anorexia nervosa patients. Nutr. Res. 39, 43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.02.006

Estour, B., Marouani, N., Sigaud, T., Lang, F., Fakra, E., Ling, Y., et al. (2017). Differentiating constitutional thinness from anorexia nervosa in DSM 5 era. Psychoneuroendocrinology 84, 94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.06.015

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., and Welch, S. L. (1999). Risk Factors for Anorexia Nervosa. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 468–476.

Ferreiro, F., Seoane, G., and Senra, C. (2011). A prospective study of risk factors for the development of depression and disordered eating in adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 40, 500–505. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.563465

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Besser, A., Su, C., Vaillancourt, T., Boucher, D., et al. (2000). The Child-Adolescent Perfectionism Scale. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 34, 634–652. doi: 10.1177/0734282916651381

Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Leiberg, S., Langner, R., Kichic, R., Hajcak, G., et al. (2002). The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol. Assess. 14:485. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485

Garner, D. M. (1991). Eating Disorder Inventory-2 Professional Manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gonçalves, S., Machado, B. C., Martins, C., Hoek, H. W., and MacHado, P. P. P. (2016). Retrospective Correlates for Bulimia Nervosa: a Matched Case-Control Study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 24, 197–205. doi: 10.1002/erv.2434

Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Seitz, J., and Konrad, K. (2011). Aetiology of anorexia nervosa: from a “‘psychosomatic family model”’ to a neuropsychiatric disorder? Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 261, 177–181. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0246-y

Hilbert, A., Pike, K. M., Goldschmidt, A. B., Wilfley, D. E., Fairburn, C. G., Dohm, F. A., et al. (2014). Risk factors across the eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 220, 500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.054

Himmerich, H., Bentley, J., Kan, C., and Treasure, J. (2019). Factores de riesgo genéticos para los trastornos alimentarios: una actualización e información sobre la fisiopatología. Rev. Toxicom. 82, 3–18.

Hollingshead, A. B., and Redlich, F. C. (1953). Social Stratification and Psychiatric Disorders. American Sociological Rev. 18, 163–169.

Jacobi, C., and Fittig, E. (2012). Psychosocial Risk Factors for Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195373622.013.0008

Jacobi, C., Hayward, C., De Zwaan, M., Kraemer, H. C., and Agras, W. S. (2004). Coming to Terms With Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: application of Risk Terminology and Suggestions for a General Taxonomy. Psychol. Bull. 130, 19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U. M. A., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., et al. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 980–998. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

Keel, P. K., and Forney, K. J. (2013). Psychosocial Risk Factors for Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 46, 433–439.

Kluck, A. S. (2010). Family influence on disordered eating: the role of body image dissatisfaction. Body Image 7, 8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.009

Klump, K. L., Bulik, C. M., Pollice, C., Halmi, K. A., Fichter, M. M., Berrettini, W. H., et al. (2000). Temperament and character in women with anorexia nervosa. J. Nervous Ment. Dis. 188, 559–567.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory CDI Manua. New York: Multi-Health Systems.

Kraemer, H. C., Kazdin, A. E., and Offord, D. E. (1997). Coming to Terms With the Terms of Risk. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 54, 337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009

Le Grange, D., Lock, J., Loeb, K., and Nicholls, D. (2010). Academy for eating disorders position paper: the role of the family in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 43, 1–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.20751

Machado, B. C., Gonçalves, S. F., Martins, C., Hoek, H. W., and Machado, P. P. (2014). Risk factors and antecedent life events in the development of anorexia nervosa: a Portuguese case-control study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 22, 243–251. doi: 10.1002/erv.2286

Matzkin, V., Slobodianik, N., Pallaro, A., Bello, M., and Geissler, C. (2007). Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. Res. 13, 1531–1545.

Misra, M., and Klibanski, A. (2014). Endocrine Consequences of Anorexia Nervosa Madhusmita. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 581–592. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70180-3

Monteleone, P., and Maj, M. (2013). Dysfunctions of leptin, ghrelin, BDNF and endocannabinoids in eating disorders: beyond the homeostatic control of food intake. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 312–330. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.021

Neumark-Sztainer, D. R., Wall, M. M., Haines, J. I., Story, M. T., Sherwood, N. E., and van den Berg, P. A. (2007). Shared Risk and Protective Factors for Overweight and Disordered Eating in Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 33, 359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031

Nicholls, D. E., Lynn, R., and Viner, R. M. (2011). Childhood eating disorders: british national surveillance study. Br. J. Psychiatry 198, 295–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081356

Olson, D. H., Portner, J., and Bell, R. Q. (1982). FACES II: family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales. United States: University of Minnesota.

Parks, M., Anastasiadou, D., Sánchez, J. C., Graell, M., and Sepulveda, A. R. (2017). Experience of caregiving and coping strategies in caregivers of adolescents with an eating disorder: a comparative study. Psychiatry Res. 260, 241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.064

Peris, T. S., and Miklowitz, D. J. (2015). Parental Expressed Emotion and Youth Psychopathology: new Directions for an Old Construct. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 46, 863–873. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0526-7

Pike, K. M., Hilbert, A., Wilfley, D. E., Fairburn, C. G., Dohm, F. A., Walsh, B. T., et al. (2008). Toward an understanding of risk factors for anorexia nervosa: a case-control study. Psychol. Med. 38, 1443–1453. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002310

Sepúlveda, A. R., Anastasiadou, D., Rodríguez, L., Almendros, C., Andrés, P., Vaz, F., et al. (2014). Spanish validation of the Family Questionnaire (FQ) in families of patients with an eating disorder. Psicothema 26, 321–327. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2013.310

Sepúlveda, A. R., Graell, M., Berbel, E., Anastasiodou, D., Botella, J., Carrobles, J. A., et al. (2012). Factors Associated with Emotional Wellbeing in Primary and Secondary Caregivers of Patients with Eating Disorders. Eur. Eat. Dis. Rev. 20, e78–84. doi: 10.1002/erv.1118

Sepulveda, A. R., Moreno-Encinas, A., Nova, E., Gomez, S., Carrobles, J. A., and Graell, M. (2021). Biological, psychological and familial specific correlates in eating disorders at onset: a control-case study protocol (ANOBAS). Actas Esp. Psiquiatr.

Spielberger, C. D., Edwards, C. D., Lushene, R. E., Montuori, J., and Platzek, A. (1973). State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R., and Lushene, R. (1970). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 128, 825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825

Stice, E., Marti, C. N., and Durant, S. (2011). Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther. 49, 622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009

Støving, R. K., Chen, J. W., Glintborg, D., Brixen, K., Flyvbjerg, A., Hørder, K., et al. (2007). Bioactive Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) I and IGF-binding protein-1 in anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 2323–2329. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1926

Striegel-Moore, R. H., and Bulik, C. M. (2007). Risk Factors for Eating Disorders. Am. Psychol. 62, 181–198. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181

Theodoratou-Bekou, M., Andreopoulou, O., Andriopoulou, P., and Wood, B. (2012). Stress-related asthma and family therapy: case study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 11, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-11-28

Treasure, J., Duarte, T. A., and Schmidt, U. (2020). Eating disorders. Lancet 395, 899–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30059-3

Treasure, J., Sepúlveda, A. R., Macdonald, P., Whitaker, W., Lopez, C., Zabala, M., et al. (2008). The assessment of the family of people with eating disorders. Eur. Eat. Dis. Rev. 16, 247–255. doi: 10.1002/erv.859

Verkleij, M., Van De Griendt, E.-J., Colland, V., Van Loey, N., Beelen, A., and Geenen, R. (2015). Parenting Stress Related to Behavioral Problems and Disease Severity in Children with Problematic Severe Asthma. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. 22, 179–93. doi: 10.1007/s10880-015-9423-x

Wiedemann, G., Rayki, O., Feinstein, E., and Hahlweg, K. (2002). The Family Questionnaire: development and validation of a new self-report scale for assessing expressed emotion. Psychiatry Res. 109, 265–279. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00023-9

Zabala, M. J., Macdonald, P., and Treasure, J. (2009). Appraisal of caregiving burden, expressed emotion and psychological distress in families of people with eating disorders: a systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 17, 338–349. doi: 10.1002/erv.925

Keywords : eating disorders, case-control study, biological correlates, psychological correlates, familial correlates

Citation: Sepúlveda AR, Moreno-Encinas A, Martínez-Huertas JA, Anastasiadou D, Nova E, Marcos A, Gómez-Martínez S, Villa-Asensi JR, Mollejo E and Graell M (2021) Toward a Biological, Psychological and Familial Approach of Eating Disorders at Onset: Case-Control ANOBAS Study. Front. Psychol. 12:714414. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.714414

Received: 25 May 2021; Accepted: 20 August 2021; Published: 09 September 2021.

Reviewed by: