There appears to be a technical issue with your browser

This issue is preventing our website from loading properly. Please review the following troubleshooting tips or contact us at [email protected] .

Create an FP account to save articles to read later.

ALREADY AN FP SUBSCRIBER? LOGIN

Downloadable PDFs are a benefit of an FP subscription.

Subscribe Now

- Preferences

- Saved Articles

- Newsletters

- Magazine Archive

- Subscription Settings

World Brief

- Editors’ Picks

- Africa Brief

China Brief

- Latin America Brief

South Asia Brief

Situation report.

- Flash Points

- War in Ukraine

- Crisis in the Middle East

- U.S. election 2024

- U.S. foreign policy

- Trade and economics

- U.S.-China competition

- Artificial intelligence

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

NATO’s Future

Ones and tooze, foreign policy live.

Summer 2024 Issue

Print Archive

FP Analytics

- In-depth Special Reports

- Issue Briefs

- Power Maps and Interactive Microsites

- FP Simulations & PeaceGames

- Graphics Database

Catalysts for Change

Webinar: how to create a successful podcast, fp @ unga79, ai for healthy cities, her power @ unga79, why corruption thrives in the philippines, a marcos might soon be back in power in manila. that’s because political dynasties are more powerful than parties..

- Southeast Asia

With Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte ineligible for reelection, Ferdinand Marcos Jr.—widely known as “Bongbong”—is poised to win a landslide victory at the polls on May 9. His father, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., who ruled as a dictator for 14 years under martial law, was known for his big infrastructure projects but also for his enormous corruption. (The World Bank estimates he stole between $5 billion and $10 billion over the course of his rule.) Marcos Jr., in turn, has been accused of graft and convicted of tax evasion.

So what accounts for Marcos Jr.’s popularity in spite of his legacy of malfeasance? Like voters everywhere, Filipinos say they don’t support corruption. In fact, 86 percent of Filipinos surveyed in 2020 by Transparency International called corruption in government a big problem. One famous scandal involved members of congress funneling money to phony nongovernmental organizations in exchange for kickbacks in what is known widely as the pork barrel scam and which came to light in July of 2013. Janet Lim-Napoles, a businesswoman and the convicted ringleader of the scheme, claimed Marcos Jr. was involved, although he denied any knowledge and said his signature on forms releasing money to fake NGOs was forged.

In a political system dominated by powerful families, corrupt politicians can still succeed. Dynasties are so influential that they have largely replaced political parties as the bedrock of Philippine politics. Politicians commonly jump from one party to another, making party labels meaningless. In a country where parties come and go overnight, voters look to families to evaluate candidates.

The history of the Philippine elite—and why voters continue to uphold their power—has colonial roots.

Over the past four years, I have examined the impact of political dynasties on election outcomes in the Philippines and analyzed the results of 10 election cycles since 1992 involving 500,000 candidates. The results may help explain the Marcos family’s political staying power. Despite being chased out of the country when Marcos Sr. fell from power in 1986, the family bounced back to political prominence in only a few years: Marcos Jr. became a governor in 1998 and a senator in 2010. Imee Marcos later took on his former role as governor and is currently a senator, having been succeeded as governor by her own son Matthew Manotoc in 2019.

My research shows that, when given a choice, Philippine voters are less likely to vote for corrupt politicians. After accounting for a candidate previously holding office—since incumbents are more likely to be reelected and more likely to face corruption charges—candidates indicted for corruption are 5 percent to 7 percent less likely to be elected. This is similar to how voters react to corruption in other countries. In Brazil, which also suffers from substantial corruption, researchers Claudio Ferraz and Frederico Finan showed that in the 2004 election, when there was evidence that a mayor had engaged in corruption on one occasion, that mayor was 4.6 percent less likely to be reelected.

A supporter holds pictures of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his wife Imelda Marcos as Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and Sara Duterte-Carpio take part in an election rally in Caloocan, Philippines, on Feb. 19. Ezra Acayan/Getty Images

But Philippine voters don’t punish politicians from large political dynasties even when they’ve been indicted for corruption. Ronald Mendoza and researchers at the Ateneo School of Government calculated that, as of 2019, 80 percent of governors, 67 percent of members of the House of Representatives, and 53 percent of mayors had at least one relative in office. These rich and powerful family networks can protect politicians from real accountability and keep reform at bay.

The history of the Philippine elite—and why voters continue to uphold their power—has colonial roots. When the United States seized control of the Philippines in 1898, it pledged to give land to the poor. The opposite happened. The United States spent $7 million—almost as much as it paid for Alaska in the 1860s—to buy land from Catholic friars who had run much of the country. But the land was sold at prices well above what the poor could afford. The United States also instituted a system of land titles. This could have helped protect poor farmers from being dispossessed, but the land titles were so expensive and complicated to acquire that only the well-off got titles. The rich were able to buy up more land, while the poor were left without titles or access to the best land. My research shows that areas in the Philippines with more land inequality and where more of these titles were issued by 1918 have a higher concentration of dynasties today.

The United States created a system where only property owners could vote, limiting the franchise to 1 percent of the population in the 1907 legislative elections. Wealthy landowners appointed allies to run the civil service and passed laws to cement their power. For example, in 1912, the Philippine Assembly made it a crime to break a labor contract, which effectively forced sharecroppers to stay on large plantations. Don Joaquín Ortega was appointed the first governor of La Union in 1901, and 120 years later his descendants are still governors.

Voters turn to political dynasties for a variety of reasons. Familiarity certainly helps. Families are also known for delivering pork barrel projects and even direct payouts before elections. Vote buying in the form of gifts or cash is common in the Philippines. Some dynasties have also used force to turn out votes of limited competition. In return, the ruling families tend to commission populist projects. Jinggoy Estrada, son of former President Joseph Estrada, helped build day care centers when he was mayor of San Juan. He also was twice indicted for corruption but never convicted.

The youthfulness of the Philippine population helps obscure the truth of the Marcos dictatorship. About 70 percent are under 40 years old, compared to 51 percent in the United States. Marcos Sr. was forced out of office 36 years ago, which is well before much of the electorate was even born. Few have a recollection of martial law.

Deeply entrenched political dynasties have hollowed out the political process, making elections not about parties or ideas but about family names.

Over the intervening years, the Marcos clan has spruced up its image: Marcos Jr. appeared as a child in a movie glorifying his father. His older sister ran a children’s TV show when Marcos Sr. was in power. Marcos Sr. projected an air of power and pride that older voters remember. In addition, current Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte gave the clan a boost in 2016 when he had Marcos Sr. reburied in the “Cemetery of Heroes” in Manila.

Marcos Jr.’s campaign also appeals to nostalgia among voters who lived during the era when Marcos Sr. built new rail lines, cultural centers, hospitals, and other infrastructure projects, as well as among younger voters who have been sold on this sanitized image of the Marcos era. Some recall the martial law period as one of peace (although not for the 34,000 political dissenters whom Amnesty International estimates were tortured by the government). The Philippine economy grew rapidly during much of the Marcos period, though it ended in a steep downturn in GDP and a huge increase in government debt.

The other major candidates running against Marcos Jr. don’t come from such important families with such deep political connections. Marcos Jr. has avoided saying much about his opponents who have attacked him and his revisionist Marcos history. This has made the campaign all about him and left his opponents looking small. Marcos Jr. has also played up his alliance with the Duterte family, as the outgoing president remains widely popular despite the brutal violence of his anti-drug campaign. Duterte’s daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio is running for vice president, further cementing a Duterte-Marcos alliance.

Across generations, the deeply entrenched political dynasties of the Philippines have hollowed out the political process, making elections not about parties or ideas but about family names. Powerful families date back to the Spanish period and have cemented their hold on power. While voters categorically oppose corruption, they continue to support families who deliver pork spending but do little for the long-term health of the country. Marcos Jr. has traded on carefully curated nostalgia about his father’s reign to propel himself to the presidency.

Daniel Bruno Davis is a Ph.D. graduate from the University of Virginia, where he studied Philippine politics and corruption. X: @Daniel_B_Davis

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Not your account? Log out

Please follow our comment guidelines , stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username:

I agree to abide by FP’s comment guidelines . (Required)

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.

Sign up for Editors' Picks

A curated selection of fp’s must-read stories..

You’re on the list! More ways to stay updated on global news:

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Israel’s Military Pulls Out of Jenin

Politics is tiktok’s newest dance move, what in the world, russia is no conservative haven, the many faces of abiy ahmed, editors’ picks, israeli military pulls out of jenin after deadly west bank raid, how tiktok is influencing the 2024 u.s. presidential election, israeli protests and german elections: foreign policy's weekly international news quiz, putin's russia is no conservative haven, is abiy ahmed a peacemaker or a warmonger, more from foreign policy, how the russian establishment really sees the war ending.

An inside look at what Russia expects—and doesn’t—in a cease-fire with Ukraine.

Trump’s Foreign-Policy Influencers

Meet the 11 men whose worldviews are shaping the 2024 Republican ticket.

The Murky Meaning of Ukraine’s Kursk Offensive

A short-term success doesn’t necessarily have any long-term effects.

Inside the White House Effort to Prevent a Coup in Guatemala

Kamala Harris’s team helped deliver an overlooked foreign-policy win.

A Fight Is Brewing Over Chinese Money in Norway

U.s. strategy should be europe first, then asia, how the hundred years’ war explains ukraine’s invasion of russia, insider | decoding trump’s foreign policy by ravi agrawal.

Sign up for World Brief

FP’s flagship evening newsletter guiding you through the most important world stories of the day, written by Alexandra Sharp . Delivered weekdays.

Other subscription options, academic rates.

Start the school year with an extra 67% off.

Lock in your rates for longer.

Unlock powerful intelligence for your team.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

A look at how corruption works in the Philippines

The Philippines is perceived to be one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Of 180 countries, the Philippines ranked 116 in terms of being least corrupt. This means that the country is almost on the top one-third of the most corrupt countries, based on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) published by Transparency International.

According to CPI, the Philippines scored a total of 33 points out of 100. Even as far back as 2012, it has fluctuated around the same CPI score, with the highest score being 38 points in 2014 and the lowest being 33 points in 2021 and 2022. To further contextualize how low it scored, the regional average CPI score for the Asia-Pacific region is 45, with zero as highly corrupt. And of the 31 countries and territories in the region, the Philippines placed 22nd (tied with Mongolia).

It must be noted, however, that CPI measures perceptions of corruption and is not necessarily the reality of the state of corruption. CPI reflects the views of experts or surveys of business people on a number of corrupt behavior in the public sector (such as bribery, diversion of public funds, nepotism in the civil service, use of public office for private gain, etc.). CPI also measures the available mechanisms to prevent corruption, such as enforcement mechanisms, effective prosecution of corrupt officials, red tape, laws on adequate financial disclosure and legal protection for whistleblowers.

These data are taken from other international organizations, such as the World Bank, World Economic Forum, private consulting companies and think tanks.

Of course, measuring actual corruption is quite difficult, especially as it involves under-the-table activities that are only discovered when they are prosecuted, like in the case of the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses, which was estimated to be up to $10 billion based on now-deleted Guinness World Records and cited as the “biggest robbery of a government.” Nevertheless, there still exists a correlation between corruption and corruption perceptions.

4 Syndromes

Corruption does not come in a single form as well. In a 2007 study, Michael Johnston, a political scientist and professor emeritus at Colgate University in the United States, studied four syndromes (categories) of corruption that were predominant in Asia, citing Japan, Korea, China and the Philippines as prime examples of each category.

The first category is Influence Market Corruption, wherein politicians peddle their influence to provide connections to other people, essentially serving as middlemen. The second category is Elite Cartel Corruption, wherein there exist networks of elites that may collude to protect their economic and political advantages. The third form of corruption is the Official Mogul Corruption, wherein economic moguls (or their clients) are usually the top political figures and face few constraints from the state or their competitors.

Finally, there is the form of corruption that the Philippines is familiar with. Oligarch-and-Clan Corruption is present in countries with major political and economic liberalization and weak institutions. Corruption of this kind has been characterized by Johnston as having “disorderly, sometimes violent scramble among contending oligarchs seeking to parlay personal resources into wealth and power.” Other than the Philippines, corruption in Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka falls under the same syndrome.

In the Philippines, Oligarch-and-Clan Corruption manifests itself in the political system. As Johnston noted, in this kind of corruption, there is difficulty in determining what is public and what is private (i.e., who is a politician and who is an entrepreneur). Oligarchs attempt to use their power for their private benefit or the benefit of their families. From the Aquinos, Binays, Dutertes, Roxases and, most notoriously, the Marcoses, the Philippines is no stranger to political families. In a 2017 chart by Todd Cabrera Lucero, he traced the lineage of Philippine presidents and noted them to be either related by affinity or consanguinity.

Corruption in the Philippines by oligarch families is not unheard of. In fact, the most notable case of corruption in the Philippines was committed by an oligarchic family—the Marcos family. The extent of the wealth stolen by former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his wife has been well-documented. In fact, several Supreme Court cases clearly show the extent of the wealth that the Marcoses had stolen.

In an Oligarch-and-Clan system of corruption, oligarchs will also leverage whatever governmental authority they have to their advantage. Going back to the Marcos example, despite their convictions, the Marcoses have managed to weasel their way back into power, with Ferdinand Marcos Jr. becoming the 17th President despite his conviction for tax violation. Several politicians have also been convicted of graft and corruption (or have at least been hounded by allegations of corruption) and still remain in politics. As observed by Johnston in his article, though Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos are the popular images of corruption in the Philippines, he also noted other entrenched oligarchs throughout the country.

Finally, factions also tend to be “unstable and poorly disciplined.” The term “balimbing” is often thrown around in local politics but, more than that, the Philippines is also familiar with politically-motivated violence and disorder.

All these features are characteristics of Oligarch-and-Clan corruption, where these oligarchic families continue to hold power and politicians exploit their positions to enrich themselves or their families.

Corruption, no matter what kind, needs to be curbed. It results in loss of government money, which could have been used to boost the economy and help ordinary citizens, especially those from the lower income sectors.

According to the 2007 study, the Office of the Ombudsman had, in 1999, pegged losses arising from corruption at P100 million daily, whereas the World Bank estimates the losses at one-fifth of the national government budget. For relatively more updated figures, former Deputy Ombudsman Cyril Ramos claimed that the Philippines had lost a total of P1.4 trillion in 2017 and 2018. These estimates are in line with the World Bank estimates of one-fifth (or 20 percent) of the national budget.

So grave is the adverse effect of corruption that the international community recognized it as an international crime under the United Nations Convention Against Corruption where perpetual disqualification of convicted officials is recommended.

But the question stands: can corruption be eradicated in developing countries like the Philippines? Many Philippine presidents promised to end corruption in their political campaigning, but none has achieved it so far. If the government truly wants to end corruption, it must implement policies directed against corruption, such as lifting the bank secrecy law, prosecuting and punishing corrupt officials, increasing government transparency and more. INQ

This is part of the author’s presentation at DPI 543 Corruption: Finding It and Fixing It course at Harvard Kennedy School, where he is MPA/Mason fellow.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

This article reflects the personal opinion of the author and not the official stand of the Management Association of the Philippines or MAP. He is a member of MAP Tax Committee and MAP Ease of Doing Business Committee, co-chair of Paying Taxes on Ease of Doing Business Task Force and chief tax advisor of Asian Consulting Group. Feedback at [email protected] and [email protected] .

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

This is an information message

We use cookies to enhance your experience. By continuing, you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more here.

- Top Stories

- Stock Market

- BUYING RATES

- FOREIGN INTEREST RATES

- Philippine Mutual Funds

- Leaders and Laggards

- Stock Quotes

- Stock Markets Summary

- Non-BSP Convertible Currencies

- BSP Convertible Currencies

- US Commodity futures

- Infographics

- B-Side Podcasts

- Agribusiness

- Arts & Leisure

- Special Features

- Special Reports

- BW Launchpad

- Editors' Picks

The problem of corruption and corruption of power

Thinking beyond politics.

By Prof. Victor Andres Manhit

Transparency International (TI) has been fighting corruption for 27 years in over 100 countries. Here in the Philippines, I remember their prominent voices such as Randy David, Solita Monsod, Attorney Lilia de Lima, and Judge Dolores Español — all passionate advocates for transparency and accountability, issues that are still very relevant in our society.

Accordingly, TI defines corruption as “the abuse of power for private gain.” By this, corruption has deprived countless citizens around the globe of much-needed public services and benefits of development.

Under the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), corruption indicators pertain to “bribery; the diversion of public funds; the effective prosecution of corruption cases; adequate legal frameworks, access to information; and legal protections to whistleblowers, journalists and investigators.”

But what has corruption caused us?

In September 2018, the United Nations (UN), citing World Economic Forum (WEF) data, expressed that global corruption eats up 5% of the world’s gross domestic product; in November, the World Financial Review stated that Philippines had lost $10 BILLION annually due to illicit financial flows; in December, the UN and the WEF disclosed that $3.6 TRILLION had been lost due to bribes and stolen money; and in December 2019, the WEF published that “corruption, bribery, theft and tax evasion, and other illicit financial flows cost developing countries $1.26 TRILLION a year.”

In the Philippines, an estimated P1.4 TRILLION has been lost to corruption in the years 2017 (P670 BILLION) and 2018 (P752 BILLION), Deputy Ombudsman Cyril Ramos said, where around 20% of the annual government appropriation goes to corruption. Also, according to a study by Carandang and Balboa-Cahig (2020), “some of the more notable typologies and their accompanying corruption cases in the Philippine context are as follows: non-Compliance with the Government Procurement Reform, technical malversation, political dynasty, ghost project, income and asset misdeclaration, red tape, influencing a subordinate to defy order and protocol, bribery, connivance of government officials with drug lords.”

Further, the wide-ranging impact of corruption could result in a myriad of outcomes. In April 2020, the Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Center (GIACC) said that corruption may cause

“inadequate infrastructure, dangerous infrastructure, displacement of people, damage to the environment, reduced spending in infrastructure, reduced public expenditure, and reduced foreign investment.”

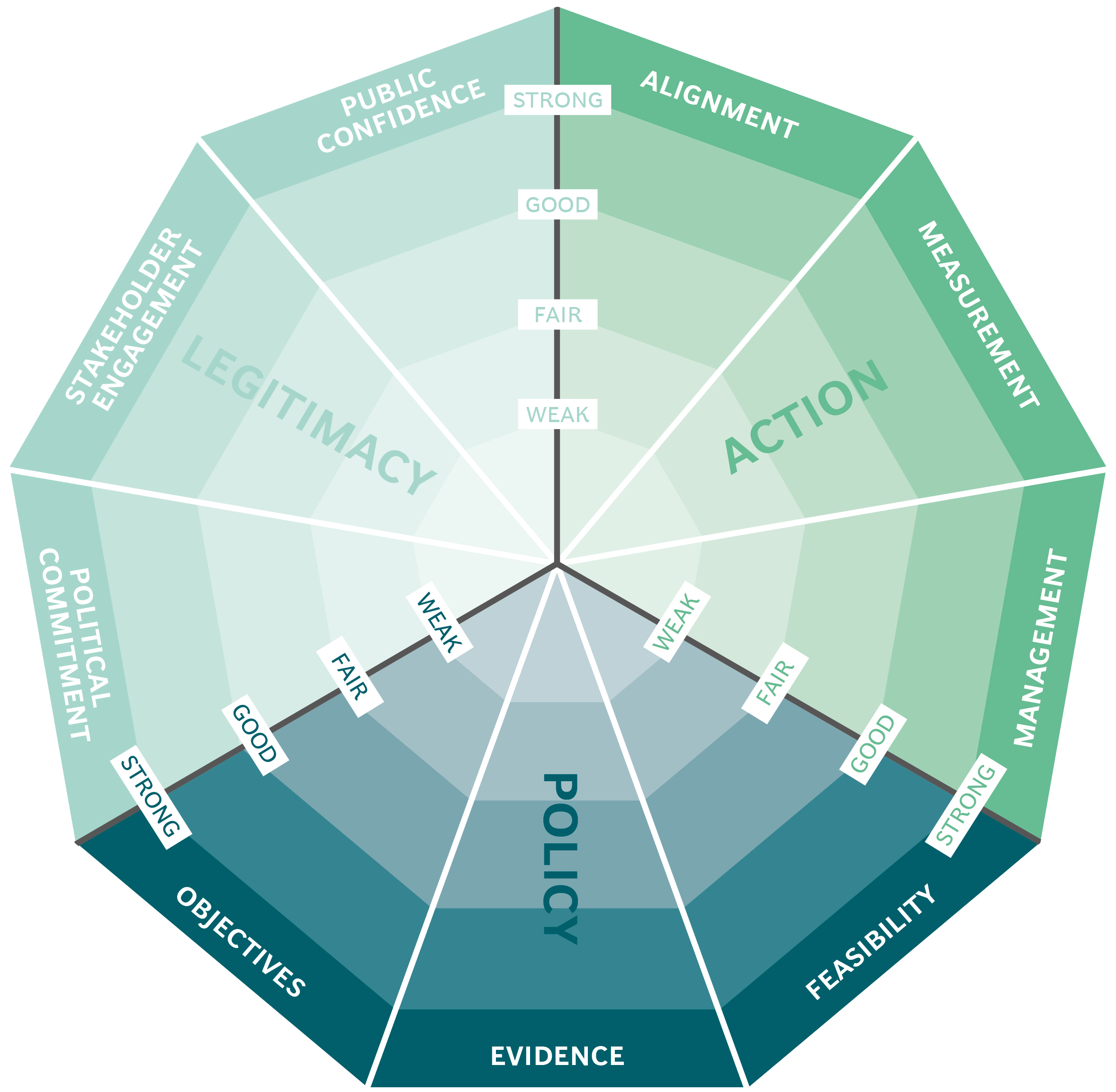

The said CPI indicators and data culled to substantiate them, and the gargantuan multi-level impact of corruption represent a formidable platform in instigating institutional reforms to achieve bureaucratic coherence and improve the development capacity of the state. With a multi-stakeholder roadmap against corruption, the plans and investments for economic recovery and development in the new normal will not be for naught. In turn, succeeding economic growths could be dispersed effectively.

Specifically, combating corruption in our country instantly augments the chance of helping the following: the 1.3 million people who have perceived themselves as poor in 2019 (self-rated poverty) and the families suffering from hunger (20.9%) during the pandemic, according to an SWS survey; the 16.7% of the population in poverty (Philippine Statistics Authority); and the additional 1.5 million Filipinos pushed into poverty by the pandemic (Philippine Institute for Development Studies).

But the problem of corruption could dangerously be translated into corruption of power. This happens if political opportunism becomes a trend. Rather than harmonize national unity in a pandemic-ravaged country, division and confusion among the population or a particular sector is instead espoused. In turn, false promises and hopes could frustrate the holistic approach being forged by a wide-range of social actors attuned to the long-standing battle against corruption.

More so, corruption of power could be exacerbated whenever the law is weaponized and used to benefit a new or selected few. Empirically, two examples could be cited. First if more than half of Filipinos agree that “It is dangerous to print or broadcast anything critical of the administration, even if it is the truth,” (SWS, July 3-6, 2020 survey), then what we have now is a terrified citizenry.

Second, the latest political charade in “handling” the country’s elite is not really about dismantling the oligarchy as pronounced. What’s happening is a mere changing of the old guards; the overt creation and empowerment of a new oligarchy, the “Dutertegarchs,” as William Pesek has pointedly raised.

To address corruption, political-institutional and economic reforms beg to be independently and holistically crafted and implemented.

Victor Andres “Dindo” C. Manhit is the President of Stratbase ADR Institute.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

PHL inflation cools in boon for rate cuts

Talent shortage may hamper adoption of AI among Philippine BPO firms

ADB to boost infrastructure support for Philippines under six-year plan

The Philippines: a social structure of corruption

- Published: 06 February 2024

- Volume 82 , pages 223–247, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Andrew Guth ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6247-4955 1

375 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The anticorruption community largely views corruption as a government or development issue. But in the Philippines, corruption is a social structure. The very social bonds and social structures that are good at building civic unity and solidarity are also good at spreading and maintaining corruption, and this is why corruption is so difficult to remove. Patrons use these societal features to implement a ubiquitous social structure of corruption by means of maneuvered friendships that makes it difficult for the masses to know when a patron is acting as a friend or foe. The social structure encompasses the whole of society and corrupts the encircled government, political, and development systems as easily as it infiltrates all other segments of society. It is why oversight and sector-based anticorruption initiatives underperform, and why initiatives must pivot towards addressing this social structure.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Anti-corruption Institutions: Some History and Theory

Corruption as a political phenomenon.

International Anti-Corruption Initiatives: a Classification of Policy Interventions

Data availability.

The author’s interview notes generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to help ensure confidentiality of the interviewees, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Pronounced ‘leader’ in English, lider is a term used in the Philippines specifically referring to individuals (or leaders) in the community that are sought by candidates to convince the electorate to vote for that particular candidate. Liders are the individuals that perform the physical exchange of money for votes with the electorate.

A barangay is the lowest level of elected government. Each city or municipality is comprised of multiple barangays (villages).

See Appendix for a full list of respondents.

Interviews 2–3, 6, 14–16, 18–20, 22, 25, 39, 41–42, 44–50.

Utang na loob is usually translated as “debt of gratitude.” The literal translation is “debt of inside” or “internal debt.” It can also be translated as “reciprocity” or “lifelong reciprocation.”

Interviews 1,14,21,24,42–44.

The paper uses the term ‘client’ to represent the economically lower-class voters who are in clientelistic relationships with political families/candidates (patrons).

Interviews 1,14,24,42–44.

Clans are a connection of least ten extended families – usually more – where each extended family could have more than a hundred members. Clans then have a minimum of a thousand members and usually much more.

Interviews 2,5–6,9–10,14–51.

Interviews 3–6,9–10,12,14–23,25–26,27–51.

Interviews 3–6, 9–10,12,14–23,25–26,27–51.

Interviews 14–22,25–26,39,47–50.

Interviews 16,22,27–38.

Interviews 14,16,21,24,39,42–44.

Interviews 16,22.

Interview 22.

Interview 23.

Interviews 1,20.

Interviews 2,5,14–23,26,32–39,41,45,47–51.

Interviews 15–16,20,22.

Interviews 27–31.

Interview 24.

Interviews 2,6,10.

Interview 22–23.

Interviews 14,18,32–38.

Interviews 32–38.

Interviews 1,10,18–22,32–38,47–49,50–51.

Interviews 2–4,6,14–15,20,22,40,45–49.

Interview 16.

Interviews 2–3.

Interview 3.

Interviews 1,3–6,10,12,15,50.

Interview 15.

Interviews 2–3,6,15.

BARMM consists of the region formally known as the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) plus the addition of Cotabato City and villages in northern Cotabato.

Interviews 3–4.

Interview 1.

Interview 3–4,6,10,12.

Interview 7.

Interviews 2–3,6,14–16,18–20,22,25,39,41–42,44–50.

Interviews 1,3–7,10,12,14–15.

Interviews 1,3–4,6,9–10,14,16–18,24.

Interviews 1, 3–4,6,9–10,14,16–18,24.

COMELEC is the Commission on Elections in charge of ensuring fair and free elections.

Interviews 3–4,6–7.

Interview 6.

Interviews 14–15,25–26.

Interviews 14–16,25–26,32–38.

Interviews 14–15,25–26,32–38.

Interviews 14–16,20,22–23,25–38.

Interview 21.

Interview 2.

Interview 14,21,49.

Interviews 2,16,20,22–23,27–31.

Interviews 1,2.

Interviews 52,54–59,61–64,66–67.

Interviews 6,14,16,18–19,21–23,25,50.

Interviews 3–4,18,52,54–59,61–64,66–67.

Interviews 3–4,6–8,52,54–55,56–58,61,64.

Interviews 2–3,6,14–16,18–22,25,39,41–42,44–50.

Alejo, M. J., Rivera, M. E. P., & Valencia, N. I. P. (1996). [De]scribing elections: A study of elections in the lifeworld of San Isidro . Institute for Popular Democracy.

Google Scholar

Andreas, P., & Duran-Martinez, A. (2013). The International Politics of Drugs and Illicit Trade in the Americas (Working Paper No. 2013-05). Brown University: The Watson Institute for International Studies.

Auyero, J. (2000). The logic of clientelism in Argentina: An Ethnographic Account. Latin American Research Review, 35 (3), 55–81.

Article Google Scholar

Auyero, J. (2001). Poor people’s politics: Peronist Survival Networks and the legacy of Evita . Duke University Press.

Bacchus, E. B., & Boulding, C. (2022). Corruption perceptions: Confidence in elections and evaluations of clientelism. Governance, 35 (2), 609–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12598

Balotol, R. O., Jr. (2021). Ideology in the time of pandemic: A Filipino experience. Discusiones Filosóficas, 22 (38), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.17151/difil.2021.22.38.3

Bardhan, P. (2022). Clientelism and governance. World Development, 152 , 105797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105797

Benstead, L., Atkeson, L. R., & Shahid, M. A. (2019). Does wasta undermine support for democracy? Corruption, clientelism, and attitudes toward political regimes. Corruption and Informal practices in the Middle East and North Africa . Routledge.

Berenschot, W., & Aspinall, E. (2020). How clientelism varies: Comparing patronage democracies. Democratization, 27 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1645129

Bobonis, G. J., Gertler, P. J., Gonzalez-Navarro, M., & Nichter, S. (2019). Government transparency and political clientelism: Evidence from randomized anti-corruption audits in Brazil [workingPaper]. CAF. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://cafscioteca.azurewebsites.net/handle/123456789/1463

Boissevain, J. (1966). Patronage in Sicily. Man, 1 (1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/2795898

Bosworth, J. (2010). Honduras: Organized Crime Gaining Amid Political Crisis (Working Paper Series on Organized Crime in Central America, p. 33). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Brun, D. A. (2014). Evaluating political clientelism. In L. Diamond, & D. A. Brun (Eds.), Clientelism, Social Policy, and the quality of democracy (pp. 1–14). JHU Press.

Canare, T., & Mendoza, R. U. (2022). Access to Information and other correlates of Vote Buying and Selling Behaviour: Insights from Philippine Data. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 34 (2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/02601079211034607

Cantú, F. (2019). Groceries for votes: The Electoral returns of vote buying. The Journal of Politics, 81 (3), 790–804. https://doi.org/10.1086/702945

Co, E. A., Lim, M., Jayme-Lao, M. E., & Juan, L. J. (2007). Philippine Democracy Assessment: Minimizing corruption . FES Philippine Office.

Co, E. A., Tigno, J. V., Lao, M. E. J., & Sayo, M. A. (2005). Philippine Democracy Assessment: Free and Fair elections and the democratic role of political parties . Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES).

Coronel, S. (2004). How Representative is Congress? Retrieved November 8, 2013, from http://pcij.org/stories/print/congress.html

Dancel, F. (2005). Chapter V - Utang na Loob (Debt of Goodwill): A Philosophical Analysis. In Filipino Cultural Traits: Claro R. Ceniza Lectures (Vol. 4, pp. 109–128). The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. Retrieved May 7, 2017, from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hXJe6vKMjroC&oi=fnd&pg=PA109&dq=utang+na+loob&ots=IweNAplUNn&sig=PIltD0241NiXFkfyit-XHnsJPVs#v=onepage&q=utang%20na%20loob&f=false

Dressler, W. (2021). Defending lands and forests: NGO histories, everyday struggles, and extraordinary violence in the Philippines. Critical Asian Studies, 53 (3), 380–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2021.1899834

Eaton, K. (2006). The downside of decentralization: Armed Clientelism in Colombia. Security Studies, 15 (4), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636410601188463

Eaton, K., & Chambers-Ju, C. (2014). Teachers, mayors, and the transformations of Cleintelism in Colombia. In D. A. Brun & L. Diamond (Eds.), Clientelism, Social Policy, and the quality of democracy (pp. 88–113). JHU Press.

Heydarian, R. J. (2018). The rise of Duterte: A Populist revolt against Elite Democracy . Palgrave MacMillan.

Book Google Scholar

Hicken, A. (2011). Clientelism. Annual Review of Political Science, 14 (1), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220508

Hilgers, T. (2011). Clientelism and conceptual stretching: Differentiating among concepts and among analytical levels. Theory & Society, 40 (5), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-011-9152-6

Hollnsteiner, M. R. (1963). The Dynamics of Power in a Philippine Municipality . Community Development Research Council, University of the Philippines.

Institute of Philippine Culture. (2005). The vote of the poor: Modernity and tradition in people’s views of Leadership and elections . Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University.

Karhunen, P., Kosonen, R., McCarthy, D. J., & Puffer, S. M. (2018). The darker side of Social Networks in transforming economies: Corrupt Exchange in Chinese Guanxi and Russian Blat/Svyazi. Management and Organization Review, 14 (2), 395–419.

Kerkvliet, B. J., & Mojares, R. B. (Eds.). (1991). From Marcos to Aquino: Local perspectives on political transition in the Philippines . University of Hawaii Press.

Kingston, P. (2001). Patrons, clients and civil society: A Case Study of Environmental politics in Postwar Lebanon. Arab Studies Quarterly, 23 (1), 55.

Kitschelt, H., & Wilkinson, S. (2007). Patrons, clients and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition . Cambridge University Press.

Klíma, M. (2019). Political parties, clientelism and state capture. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203702031

Krug, E., Dahlberg, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A., & Lozano, R. (Eds.). (2002). World Report on Violence and Health . WHO.

Krznaric, R. (2006). The limits on Pro-poor Agricultural Trade in Guatemala: Land, Labour and Political Power. Journal of Human Development, 7 (1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880500502144

Landé, C. H. (1965). Leaders, factions, and parties: The structure of Philippine politics . Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University.

Li, L. (2018). The moral economy of guanxi and the market of corruption: Networks, brokers and corruption in China’s courts. International Political Science Review, 39 (5), 634–646.

Liu, X. X., Christopoulos, G. I., & Hong, Y. (2017). Beyond Black and White: Three decision frames of Bribery. In D. C. Robertson & P. M. Nichols (Eds.), Thinking about Bribery: Neuroscience, Moral Cognition and the psychology of Bribery (pp. 121–122). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316450765.006

Chapter Google Scholar

Lyne, M. M. (2007). Rethinking economies and institutions: The voter’s dilemma and democratic accountability. In H. Kitschelt & S. I. Wilkinson (Eds.), Patrons, clients and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition (pp. 159–181). Cambridge University Press.

Magaloni, B., Diaz-Cayeros, A., & Estevez, F. (2007). Clientelism and portfolio diversification: A model of electoral investment with applications to Mexico. In H. Kitschelt, & S. I. Wilkinson (Eds.), Patrons, clients and policies: Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition (pp. 182–205). Cambridge University Press.

Mendoza, R. U., Yap, J. K., Mendoza, G. A. S., Pizzaro, A. L. J., & Engelbrecht, G. (2022). Political dynasties and Terrorism: An empirical analysis using data on the Philippines. Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 10 (2), 435–459. https://doi.org/10.18588/202210.00a266

Mişcoiu, S., & Kakdeu, L. M. (2021). Authoritarian clientelism: The case of the president’s ‘creatures’ in Cameroon. Acta Politica, 56 (4), 639–657. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00188-y

Montiel, C. J. (2014). Philippine Political Culture and Governance . Retrieved June 8, 2016, from http://www.ombudsman.gov.ph/UNDP4/philippine-political-culture-view-from-inside-the-halls-of-power/index.html

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2006). Corruption: Diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Democracy, 17 (3), 86–99.

Muno, W. (2010). Conceptualizing and Measuring Clientelism . Retrieved February 25, 2014, from http://www.academia.edu/3024122/Conceptualizing_and_Measuring_Clientelism

Norton, A. R. (2007). The role of Hezbollah in Lebanese domestic politics. The International Spectator, 42 (4), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932720701722852

Persson, A., Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2013). Why Anticorruption reforms fail—systemic corruption as a collective action problem. Governance, 26 (3), 449–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2012.01604.x

Persson, A., Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2019). Getting the basic nature of systemic corruption right: A reply to Marquette and Peiffer. Governance, 32 (4), 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12403

Piattoni, S. (2001). Clientelism in historical and compartive perspective. Clientelism, interests, and democratic representation: The European experience in historical and comparative perspective (pp. 1–30). Cambridge University Press.

Pitt-Rivers, J. A. (1954). The people of the Sierra . Criterion Books. Retrieved February 24, 2014, from http://archive.org/details/peopleofthesierr001911mbp

Quah, J. S. T. (2010). Curbing corruption in the Philippines: Is this an impossible dream? Philippine Journal of Public Administration, 54 (1–2), 1–43.

Quah, J. S. T. (2019). Combating police corruption in five Asian countries: A comparative analysis. Asian Education and Development Studies, 9 (2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-06-2019-0100

Quah, J. S. T. (2021). Breaking the cycle of failure in combating corruption in Asian countries. Public Administration and Policy, 24 (2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAP-05-2021-0034

Republic Act 7160: The Local Government Code of the Philippines, & 7160, R. A. (1991). Congress of the Philippines , Book III. Retrieved October 27, 2015, from http://www.dilg.gov.ph/LocalGovernmentCode.aspx

Radeljić, B., & Đorđević, V. (2020). Clientelism and the abuse of power in the Western Balkans. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 22 (5), 597–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2020.1799299

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1978). Corruption: A study in Political Economy . Academic Press: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Rothstein, B. (2011). Anti-corruption: The indirect ‘big bang’ approach. Review of International Political Economy, 18 (2), 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692291003607834

Sarkar, R. (2020). Corruption and Its Consequences. In R. Sarkar (Ed.), International Development Law: Rule of Law, Human Rights and Global Finance (pp. 355–418). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40071-2_8

Schaffer, F. C. (2002). What is Vote Buying? Empirical Evidence . Retrieved March 27, 2017, from http://web.mit.edu/CIS/pdf/Schaffer_2.pdf

Scott, J. C., & Kerkvliet, B. J. (1973). How traditional rural patrons lose legitimacy: A theory with special reference to Southeast Asia . Université catholique de Louvain.

Scott, J. C. (1972). Patron-client politics and political change in Southeast Asia. The American Political Science Review, 66 (1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.2307/1959280

Sidel, J. (1999). Capital, Coercion, and crime: Bossism in the Philippines . Stanford University Press.

Stokes, S., Dunning, T., Nazareno, M., & Brusco, V. (2013). Brokers, voters, and clientelism: The puzzle of Distributive politics . Cambridge University Press.

Tanaka, M., & Melendez, C. (2014). The future of Peru’s brokered democracy. In L. Diamond & D. A. Brun (Eds.), Clientelism, Social Policy, and the quality of democracy (pp. 1–14). JHU Press.

Thompson, M., & Batalla, E. V. C. (Eds.). (2018). Introduction. Routledge Handbook of the Contemporary Philippines (pp. 26–37). Taylor & Francis.

Transparency International (2023). 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index . Transparency.Org. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021

US Department of State (2022). 2022 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report: Volume I - Drug and Chemical Control (As submitted to Congress) . Retrieved March 30, 2022, from https://www.state.gov/2022-incsr-volume-i-drug-and-chemical-control-as-submitted-to-congress/

Varraich, A. (2014). Corruption: An Umbrella Concept (Working Paper Series 2014: 05 ) . The Quality of Government Institute.

Vuković, V. (2019). Political Economy of Corruption, Clientelism and Vote-Buying in Croatian Local Government. In Z. Petak & K. Kotarski (Eds.), Policy-Making at the European Periphery: The Case of Croatia (pp. 107–124). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73582-5_6

Weingrod, A. (1968). Patrons, patronage, and political parties. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 10 (4), 377–400.

Weiss, M. (2019). Chapter 8: Patranage Politics and parties in the Philippines: Insights from the 2016 elections. In P. D. Hutchcroft (Ed.), Strong Patronage, weak parties: The Case for Electoral System Redesign in the Philippines . Co Published With World Scientific. Retrieved January 23, 2023, from https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/9789811212604_0008

WHO (2014). Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 . World Health Organization. Retrieved November 8, 2017, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564793

Wolf, S. (2009). Subverting democracy: Elite rule and the limits to political participation in post-war El Salvador. Journal of Latin American Studies, 41 (3), 429–465.

Zeidan, D. (2017). Municipal Management and Service Delivery as Resilience Strategies: Hezbollah’s Local Development Politics in South-Lebanon. In Islam in a Changing MIddle East: Local Politics and Islamist Movements (pp. 37–40). The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS). Retrieved December 2, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Melissa_Marschall/publication/320592315_Municipal_Service_Delivery_Identity_Politics_and_Islamist_Parties_in_Turkey/links/59ef4946a6fdccd492871a9f/Municipal-Service-Delivery-Identity-Politics-and-Islamist-Parties-in-Turkey.pdf#page=38

Download references

No funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Overseas Education, Chengdu University, 2025 Chengluo Avenue, Longquanyi District, Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, China

Andrew Guth

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The sole author (Dr. Andrew Guth) performed all work for the paper, including conception and design; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafting and revising; final approval for publication; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrew Guth .

Ethics declarations

No prior presentation of the paper.

Ethical approval

Research adheres to the principles and guidance for human subjects research. Research was reviewed by the appropriate ethics committee on human subjects research (i.e., interviews). Committee deemed the research exempt from review.

Informed consent

Informed consent forms were given and discussed with each interviewee, included that there were no benefits to the interviewee other than helping the research and that there were no foreseen risks due to the confidentiality of the interview. Data collection procedures are discussed further in the methods section of the paper.

Human subjects research

All human subjects (interviewees) are protected by confidentiality.

Competing interests

No known conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: List of interviews

All identifying markers were removed to help ensure confidentiality. Interviews performed from 2013 to 2015.

Number | Occupation |

|---|---|

1 | Executive Director - Pro-democracy NGO |

2 | Professor |

3 | Secretary General - National Pro-democracy NGO |

4 | Chairperson - International Pro-democracy NGO |

5 | Chairperson - National Pro-democracy NGO |

6 | Executive Director - Pro-democracy NGO |

7 | Assistant Professor |

8 | Former Director - Teaching Institution |

9 | Professor |

10 | Professor |

11 | Corporate Secretary - Pro-democracy NGO for Western Mindanao |

12 | President - Pro-democracy NGO for Western Mindanao |

13 | Executive Director - Anticorruption NGO |

14 | Nobel Peace Prize Nominee (former) |

15 | Founder & Director - Development NGO for Western Mindanao |

16 | University President (ret.) |

17 | Congressperson of the Philippines |

18 | Political family member |

19 | Campaign Manager |

20 | Anticorruption Grass Roots Advocate |

21 | Former Candidate for Governor |

22 | City Councilor |

23 | Provincial Judge |

24 |

|

25 | Treasurer / |

26 | Captain |

27 | Farmer |

28 | Farmer |

29 | Farmer |

30 | Farmer |

31 | Farmer |

32 | Farmer |

33 | Farmer |

34 | Farmer |

35 | Farmer |

36 | Farmer |

37 | Farmer |

38 | Farmer |

39 | Student |

40 | Student |

41 | Student |

42 | Student |

43 | Student |

44 | Student |

45 | School Teacher (ret.) |

46 | Farmer |

47 | Restaurant Employee |

48 | Housewife |

49 | Singer/Musician |

50 | Chaplain |

51 | Secretary |

52 | Philippine National Police (PNP) – Chairman Level |

53 | Member of Government Peace Panel for MILF Talks |

54 | Professor |

55 | Professor |

56 | Asian Institute of Management (AIM) Policy Center |

57 | United States Agency of International Development (USAID) |

58 | Assistant Ombudsman |

59 | Former Secretary of the Interior and Local Government – Cabinet Member in charge of Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) |

60 | Professor |

61 | Professor |

62 | Institute for Popular Democracy (IPD) |

63 | Mayor of a Metro Manila city |

64 | Philippine National Police (PNP) – Deputy Director Level |

65 | Community Development Foundation |

66 | Former Mayor of Metro Manila city |

67 | Asian Development Bank – Director’s Office of Anticorruption and Integrity (OAI) |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Guth, A. The Philippines: a social structure of corruption. Crime Law Soc Change 82 , 223–247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-024-10140-2

Download citation

Accepted : 16 January 2024

Published : 06 February 2024

Issue Date : September 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-024-10140-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social bonds

- Vote buying

- Clientelism

- Philippines

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Invisible no more: Shedding light on police violence and corruption in the Philippines

The Philippines was romanticized and dubbed the “ Pearl of the Orient Seas ” by national hero and writer José Rizal due to the country’s elegant organic beauty. However, the pearl’s beauty has been tainted by increasing police brutality, accelerated in recent years.

After becoming the 16th President of the Philippines in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte was quick and adamant about carrying out a “ war on drugs ” campaign. Duterte implemented extreme measures targeting criminals and non-compliant citizens from impoverished communities to restore peace and order in the country.

In his first press conference after being elected as president, Duterte pledged to end crime, corruption, and the illegal drug trade within three to six months of being elected. However, Duterte implemented this pledge through the promotion of a new measure: “shoot-to-kill” orders.

“What I will do is urge Congress to restore [the] death penalty by hanging,” Duterte said in his first press conference. “If you resist, show violent resistance, my order to police [will be] to shoot to kill. Shoot to kill for organized crime. You heard that? Shoot to kill for every organized crime.”

Unfortunately, Duterte’s strategies to combat the issues faced by Filipinos have conditioned and emboldened the police, creating a sense of invincibility. The implications of Duterte’s extreme strategies include the manslaughter of innocent citizens and the manifestation of police corruption in the country. However, as a new president leads the country, the future of the Philippines’ criminal justice system seems committed to less violent means.

‘Shoot-To-Kill’

Duterte’s shoot-to-kill orders evolved dangerously, putting more innocent Filipino lives at risk and perpetuating the human rights crisis in the country. The global COVID-19 pandemic was not a barrier to Duterte’s anti-crime operations.

Amidst the pandemic, the government implemented an “ Enhanced Community Quarantine ” (ECQ) for the country’s capital, Manila, as well as the entire island of Luzon in an effort to mitigate the spread of the virus. During the lockdown, Filipinos were confined in their homes, transportation was suspended, food and health services were regulated, and uniformed personnel patrolled the streets to enforce strict quarantine measures.

During the ECQ, the government did not fulfill its promises as residents did not receive relief support. On April 1, 2020, frustration from community members erupted into political demonstrations in the streets of San Roque, Quezon City. Advocates and protestors asked for answers from the government in regard to their promised supplies and food aid.

Duterte’s response? “ Shoot them dead .”

In a televised address on the same day as the protests, Duterte ordered the police and military to shoot troublemakers if they felt their lives were in danger. “My orders are to the police and military, also village officials, that if there is trouble or the situation arises that people fight and your lives are on the line, shoot them dead,” Duterte said.

According to the World Population Review’s most recent annual data, the Philippines is the country with the world’s highest number of police killings, with over 6,000 between 2016 and 2021.

As of February 2022, based on the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency’s (PDEA) Real Numbers PH data , since Duterte took office in 2016, the government implemented 229,868 operations against illegal drugs, which resulted in the arrest of a total of 331,694 suspects. Beyond this, according to the PDEA, the total number of killings during anti-drug operations reached 6,235.

In November 2021, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project published a comprehensive database of the Philippines revealing that since 2016, at least 7,742 civilians have been killed in anti-drug raids, which is approximately 25 percent higher than the figure issued by the government.

As described by Eliza Romero, a coordinator for the Malaya Movement , a US-based alliance that advocates for human rights, freedom, and democracy in the Philippines, Duterte’s fierce rhetoric has given an invitation to vigilante and extrajudicial violence among the community.

“The shoot-to-kill order will just encourage more extrajudicial killings and vigilantism,” Romero said in an interview with Foreign Policy. “It will give private citizens and barangay [village] captains impunity to commit more human rights violations with the protection of the law while normalizing carnage.”

Behind every number is a real person—whose story has been invisible and whose life has been reduced by police officers who one day decided to target an innocent victim; a brother or sister; a son or daughter; a husband or wife; a father or mother.

Karla A., daughter of Renato A. who was killed in December 2016, recounts her experiences after losing her father at the age of 10, stating in an interview with the Human Rights Watch (HRW), “I was there when it happened when my papa was shot. I saw everything, how my papa was shot. … Our happy family is gone. We don’t have anyone to call father now. We want to be with him, but we can’t anymore.”

Emboldening the Police

Duterte’s enforcement measures to achieve public order put innocent citizens in a battle they have already lost. What is worse is that Duterte not only normalized but justified the killing of innocent citizens. Duterte assured the police impunity , stating that he would not only protect them from human rights abuses but ultimately pardon them if ever they are convicted for carrying out his anti-drug campaigns. This leads to the intensification of corruption within police departments in the country.

Duterte’s shoot-to-kill orders have not shown mercy to victims as he has always been in favor of the police. He never failed to show support for the police in carrying out his campaigns in his public and televised addresses. For instance, Duterte gave orders to Bureau of Customs Commissioner Rey Leonardo Guerrero stating that “Drugs are still flowing in. I'd like you to kill there [in communities]… anyway, I'll back you up and you won't get jailed. If it's drugs, you shoot and kill. That’s the arrangement,” Duterte said .

Duterte’s vow to protect the police results in police officers feeling emboldened and invincible. Police officers who have followed Duterte’s orders are promoted through the ranks. Police officers are not held accountable for the deaths of innocent civilians; the country’s own President pardons them. On top of this, police officers are falsifying evidence to justify unlawful killings and avoid legal repercussions.

The HRW published a report titled “‘License to Kill’: Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s ‘War on Drugs,” which analyzed a total of 24 incidents that led to 32 deaths, involving Philippine National Police (PNP) personnel between October 2016 and January 2017. The report concluded that police officers would falsely claim self-defense to justify these killings.

To further strengthen their claims, police officers would plant guns, spent ammunition, and drug packets next to the bodies of victims. In turn, the victims would seem more guilty of being part of drug-related activities. Other times, police officers would work closely with masked gunmen to carry out these extrajudicial killings. In other words, police officers have succeeded in rooting their endeavors in deceit.

Fortunately, there have been instances where some police officers were legally prosecuted in police killings. Three police officers were found guilty of murdering a 17-year-old teenager in 2017, the first conviction of officers ever since Duterte launched his war on drugs.

A Look Into the Future

The Philippines as the “Pearl of the Orient Seas” has lost its luster due to the many problems that the nation continues to face—one of the most prominent ones is Duterte’s explicit abuse of police power. Similar to how pearls lose their glow when not provided with the care it needs, the integrity of police officers has dried out and become yellowed over time due to the government’s complicity.

Time and time again, Duterte has remained an instigator in instances relating to police brutality in the country. Luckily, the Philippines can combat pearl discoloration through the implementation of robust policies that would ensure increased transparency within police departments.

Freshly elected Philippine President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. makes the restoration of the yellowed pearl an achievable goal. At the 121st Police Service anniversary celebration held at Camp General Rafael T. Crame in Quezon City—the national headquarters of the PNP—Marcos Jr. brings an opportunity for redemption. Aside from calling the PNP officers “vanguards of peace,” Marcos Jr. urged them to continue serving the community with integrity in order to restore public confidence.

“The use of force must always be reasonable, justifiable, and only undertaken when necessary. Execution of authority must be fair, it must be impartial,” Marcos Jr. said . “It must be devoid of favoritism and discrimination, regardless of race, gender, social economic status, political affiliation, [and] religious belief. It is only then that you can effectively sustain with great respect and wide support the authority that you possess as uniformed servicemen of the Republic.”

Beyond this, Marcos Jr. highlighted his hope for reforming the police system under the leadership of newly installed PNP Chief Police General Rodolfo Azurin Jr. Moreover, Marcos Jr.’s aspirations to increase accountability within police departments will be complemented by Azurin Jr.’s launching of a peace and security framework titled “MKK=K” or “Malasakit + Kaayusan + Kapayapaan = Kaunlaran” which translates to policies founded on “the combination of care, order and peace shall equate to progress.”

On the other hand, it is understandable if Filipino citizens and human rights activists have lost hope for the possibility of achieving meaningful progress in reforming the broken police system. Marcos Jr. is the son of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. , an ousted dictator who infamously declared martial law in the country, and Filipinos are still navigating the trauma of the Marcos era 50 years later.

Currently, Marcos Jr. pledges to continue the campaign against illegal drugs but with an emphasis on drug prevention and rehabilitation . Under this new framework, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) implemented a program dubbed “Buhay Ingatan, Droga’y Ayawan (Value Life, Shun Drugs)” which aims to address the root of the problem by suppressing the demand for illegal drugs. According to DILG Secretary Benjamin ‘Benhur’ Abalos Jr., the initiative needs support and solidarity from all sectors of the community in order to ensure its effectiveness.

Simultaneously, Marcos Jr. has no intention to cooperate with the International Criminal Court (ICC) on their investigation of the country’s drug war killings. Based on the ICC ’s official website, their purpose “is intended to complement, not to replace, national criminal systems; it prosecutes cases only when States do not are unwilling or unable to do so genuinely.” However, Marcos Jr. stated in an interview that “The ICC, very simply, is supposed to take action when a country no longer has a functioning judiciary… That condition does not exist in the Philippines. So I do not see what role the ICC will play in the Philippines.”

Nearly five months into Marcos Jr.’s administration, the University of the Philippines’ Dahas Project revealed that 152 people have died in anti-drug police raids as of Nov. 30. The report further disclosed that the drug casualties under Marcos Jr. “[are] exceeding the 149 killings recorded during the final six months of the Duterte government. During the first half of the year under Duterte, the average daily rate was 0.8. So far under Marcos, the rate stands at one per day.”

In the Philippines, police officers have repeatedly assumed the roles of prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner. HRW Deputy Director for Asia Phil Robertson points out shortcomings in Marcos Jr.’s campaigns describing that “Using a drug rehabilitation approach means little when police and mystery gunmen are still executing suspected drug users and dealers. Law enforcers should receive clear orders to stop the ‘drug war’ enforcement once and for all.” The only way to effectively mitigate police killings in the Philippines is by abandoning violent and punitive measures against illegal drugs.

Ultimately, despite these obstacles, the yellowed pearl can still brighten. Under new leadership for both the national government and police department, the Philippines may embark on a journey of reconstruction and rehabilitation. In this process, the hope is to finally shed light on the issue of police violence in the country, implement fruitful solutions to combat the problem and advocate for innocent victims who might have felt invisible in their battle against police brutality. Once the light has been restored, the Philippines can finally live up to its billing as the beautiful and pure “Pearl of the Orient Seas”.

Laurinne Jamie Eugenio

Recent posts, bridging generations and cultures: interview with aki-matilda høegh-dam, danish-greenlandic politician and youngest member of the danish parliament.

Buzzing Dangers: The Impact of Neonicotinoid Pesticides on Pollinators and the Global Economy

New Horizons in Women’s Health: Insights from PMNCH’s Executive Director Rajat Khosla

The Coldest Geopolitical Hotspot: Global Powers Vie for Arctic Dominance over Greenland

The Black Gold of the Black Market: Russia’s Lucrative (and Illegal) Oil Trades

You Might Be Interested In

Is beijing creating a new sino-russian world order the russian invasion of ukraine might change beijing’s calculus for taiwan and the united states, defying dictatorships: an interview with garry kasparov, cambodia’s triumph and tragedy: the un’s greatest experiment 30 years on.

U4 Helpdesk Answer

Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in the philippines.

A more recent publication is available:

The Philippines: Corruption and anti-corruption 2023:18

In collaboration with

Transparency International

Cite this publication

Nawaz, F. (2009) Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in the Philippines . Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute (U4 Helpdesk Answer Helpdesk)

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence ( CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 )

Creative Commons CC Creative Commons BY Creative Commons NC Creative Commons ND

Related Content

Specialised anti-corruption courts: Philippines

Corruption self-assessment tools for the public sector

Harnessing the power of communities against corruption

Corruption in the Philippines: Framework and context

Chat with Paper

Challenging Corruption in Asia: Case Studies and a Framework for Action

Combating corruption in a "failed" state: the nigerian economic and financial crimes commission (efcc), state power and private profit: the political economy of corruption in southeast asia, decentralization and corruption: the bumpy road to public sector integrity in developing countries, policy reforms and institutional weaknesses: closing the gap, institutions, institutional change, and economic performance, corruption and growth, a theory of incentives in procurement and regulation., corruption and development, between miti and the market: japanese industrial policy for high technology, related papers (5), the social context of business and the tax system in nigeria : the persistence of corruption, vertical governance: brokerage, patronage and corruption in indian metropolises, demystifying the concept of state or regulatory capture from a theoretical public economics perspective., planning and the political market: public choice and the politics of government failure, what do good governments actually do: an analysis using european procurement data, trending questions (3).

Not addressed in the paper.

Corruption in the Philippines is viewed as a principal-agent problem influenced by historical and social factors, impacting relationships between public interest, politicians, and bureaucrats within the political context.

The paper explains how corruption in the Philippines has evolved from nepotism to smuggling, public-works contracts, debt-financed schemes, asset privatizations, and recently, underworld-related activities.

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Corruption — The Problem of Corruption and Its Examples in Philippines

The Problem of Corruption and Its Examples in Philippines

- Categories: Corruption Political Corruption

About this sample

Words: 979 |

Published: Mar 19, 2020

Words: 979 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

6 pages / 2760 words

4 pages / 2014 words

4 pages / 1601 words

2 pages / 991 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Corruption

William Shakespeare's Hamlet is a play that is often regarded as one of the greatest tragedies ever written. It delves deep into themes of decay and corruption, depicting a world that is falling apart both morally and [...]

Symbolism Of Poison In HamletIn Shakespeare's renowned play, Hamlet, poison emerges as a powerful symbol that permeates the plot and the characters' lives. While the literal presence of poison is evident in the play, it also [...]

Stalking is a pervasive and dangerous form of interpersonal violence that can have devastating effects on victims. According to the National Institute of Justice, stalking is defined as a pattern of repeated and unwanted [...]

Throughout the play Hamlet, Shakespeare presents a world fraught with moral decay and political manipulation, where characters are consumed by their own desires and ambitions. Corruption, both moral and political, is a pervasive [...]

The purpose of a criminal justice system is to reprimand those who have broken the law while maintaining societal order. However, nothing manufactured by humans is without flaw. There have been countless instances of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Corpus ID: 154421799

Corruption in the Philippines: Framework and context

- E. D. Dios , Ricardo D. Ferrer

- Published 2000

- Political Science

Tables from this paper

27 Citations

Challenging corruption in asia: case studies and a framework for action, philippine technocracy as a bulwark against corruption: the promise and the pitfall, decentralization and corruption: a model of interjurisdictional competition and weakened accountability, state power and private profit: the political economy of corruption in southeast asia.

- Highly Influenced

- 10 Excerpts

Policy transfer in the Philippines: Can it pass the localisation test?

Imposing cooperation: the impact of institutions on the efficiency of cooperatives in the philippines, corruption and development, decentralization and corruption : the bumpy road to public sector integrity in developing countries, corruption and foreign direct investment in the philippines, from protest to participation accountability reform and civil society in the philippines, 27 references, the ‘perverse effects' of political corruption, corruption and the global economy.

- Highly Influential

Corruption and Development: A Review of Issues

Institutions, institutional change and economic performance: economic performance, economic development through bureaucratic corruption, corruption : the boom and bust of east asia, institutions and economic change in southeast asia : the context of development from the 1960s to the 1990s, a theory of incentives in procurement and regulation, the political economy of the rent-seeking society, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

A broken vow: an examination of the cases of Corruption in the Philippines

- Christian Gonzales Isabela State University - Cauayan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7712-359X

The problem of corruption in the Philippines seems to be humongous as if no solution is available for its cure. This study used a descriptive and qualitative research design. It exposed the anti-corruption laws and the cases decided by the various Philippine courts. It found out that even with the existence of laws as well as the removal or the conviction of several government officials and employees, corrupt practices seem to be undeterred. The continuance of corruption in the country resulted to the promise of President Duterte to be a broken vow.

ABS-CBN. (2016, December 17). Duterte fires 2 immigration deputies in bribery scandal. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from ABS-CBN News: https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/12/16/16/duterte-fires-2-immigration-deputies-in-bribery-scandal

Araja, R. N. (2020, October 28). Ombudsman suspends 44 BI execs over ’pastillas’ scam. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from ManilaStandard.Net: https://manilastandard.net/mobile/article/337994

Aranas, A. G. (2016, May 31). Bureaucracy on Trail: Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees. International Journal of Current Research, 32071-32073. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from http://www.journalcra.com/sites/default/files/issue-pdf/14698.pdf

Ballaran, J. (2018, April 6). Aguirre resigned due to public’s loss of trust in him – official. Retrieved December 5, 2020, from Inquirer.Net: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/980581/aguirre-resigned-due-to-publics-loss-of-trust-in-him-official

Batalla, E. V. (2020, June 10). Grand corruption scandals in the Philippines. Emerald Insight, 23(1), 73-86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/PAP-11-2019-0036

Buan, L. (2018, May 8). Ombudsman probes P60-million DOT-Tulfo controversy. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from Rappler: https://www.rappler.com/nation/ombudsman-investigation-wanda-teo-tourism-department-tulfo-controversy

Bueza, M. (2018, June 29). Notable Duterte admin exits and reappointments. Retrieved December 5, 2020, from Rappler: https://specials.rappler.com/newsbreak/videos-podcasts/205964-firing-resignations-reappointments-duterte-administration/index.html

Campanilla, M. B. (2019). Criminal Law Reviewer Volume II. Manila: Rex Printing Company Inc.

Carandang, M. A., & Balboa-Cahig, J. A. (2018). COUNTERING CORRUPTION IN THE PHILIPPINES: PROTOTYPES AND REINFORCING MEASURES. TWELFTH REGIONAL SEMINAR ON GOOD GOVERNANCE FOR SOUTHEAST ASIAN COUNTRIES (pp. 103-113). Tokyo City, Japan: United Nations Asia and Far East Institute for the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://www.unafei.or.jp/publications/pdf/GG12/21_GG12_CP_Philippines.pdf

CNN Philippines Staff. (2018, May 3). President's office investigating officials involved in P60M DOT-PTV deal controversy. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from CNN Philippines: https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2018/05/03/DOT-Tourism-Wanda-Teo-PTV-4-Tulfo.html

CNN Staff, P. (2017, October 23). Malacañang: Bautista's resignation 'effective immediately. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from CNN Philippines: https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2017/10/23/malcanang-andres-bautista-resignation-effective-immediately.html

Conde, C. H. (2007, October 1). Benjamin Abalos, Filipino elections official, resigns in a scandal that may threaten Arroyo. The New York Times, p. not applicable. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/01/world/asia/01iht-phils.1.7696723.html

Coronel, S. S., & Kawal-Tirol, L. (2002). Investigating Corruption: A Do-It-Yourself Guide. Manila: Philipine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Corrales, N. (2016, March 20). Duterte: ‘I can’t promise heaven, but I will stop corruption’. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from Inquirer.Net: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/775352/duterte-i-cant-promise-heaven-but-i-will-stop-corruption