- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

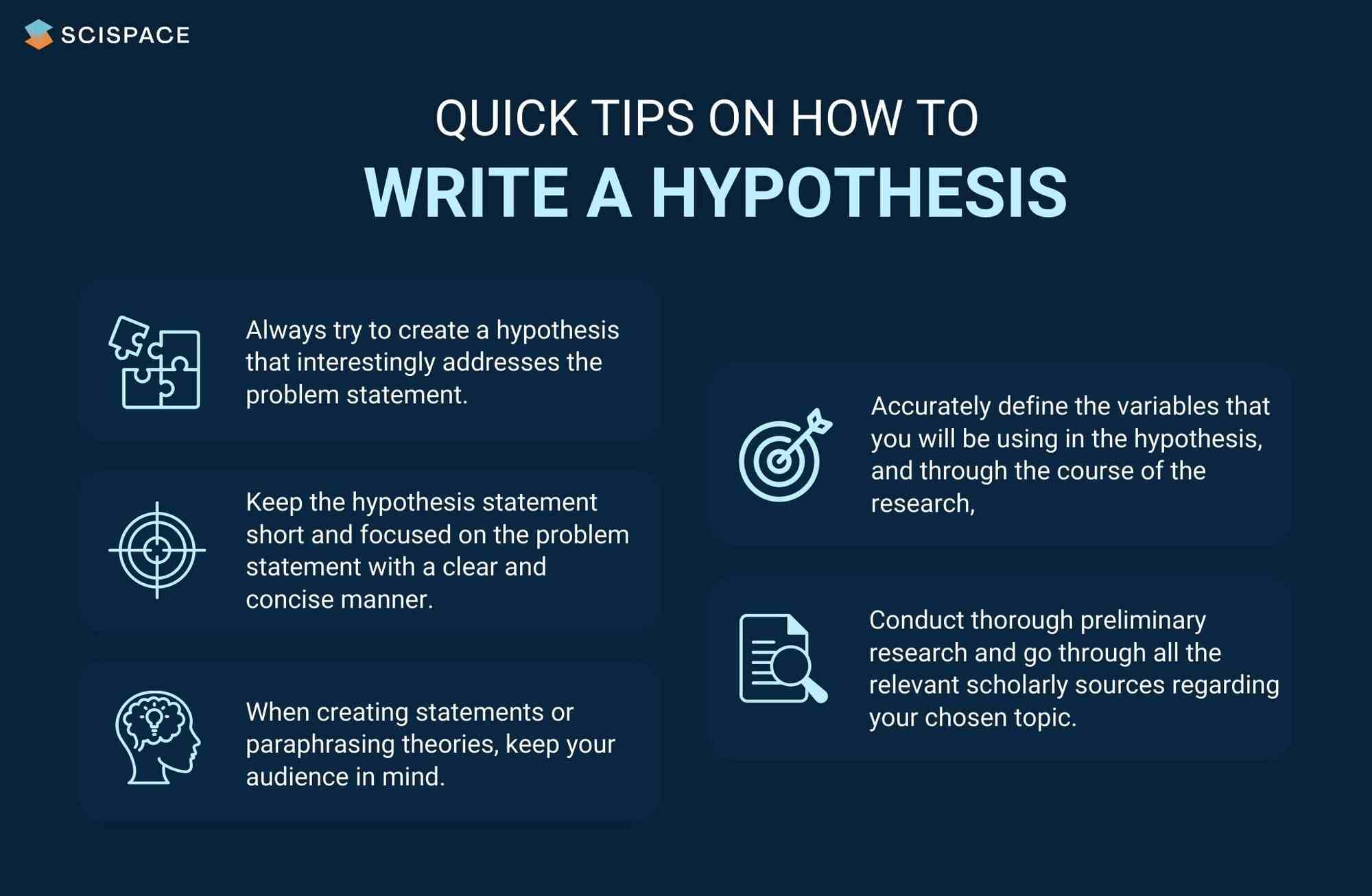

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

Published on November 2, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on May 31, 2023.

A research problem is a specific issue or gap in existing knowledge that you aim to address in your research. You may choose to look for practical problems aimed at contributing to change, or theoretical problems aimed at expanding knowledge.

Some research will do both of these things, but usually the research problem focuses on one or the other. The type of research problem you choose depends on your broad topic of interest and the type of research you think will fit best.

This article helps you identify and refine a research problem. When writing your research proposal or introduction , formulate it as a problem statement and/or research questions .

Table of contents

Why is the research problem important, step 1: identify a broad problem area, step 2: learn more about the problem, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research problems.

Having an interesting topic isn’t a strong enough basis for academic research. Without a well-defined research problem, you are likely to end up with an unfocused and unmanageable project.

You might end up repeating what other people have already said, trying to say too much, or doing research without a clear purpose and justification. You need a clear problem in order to do research that contributes new and relevant insights.

Whether you’re planning your thesis , starting a research paper , or writing a research proposal , the research problem is the first step towards knowing exactly what you’ll do and why.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

As you read about your topic, look for under-explored aspects or areas of concern, conflict, or controversy. Your goal is to find a gap that your research project can fill.

Practical research problems

If you are doing practical research, you can identify a problem by reading reports, following up on previous research, or talking to people who work in the relevant field or organization. You might look for:

- Issues with performance or efficiency

- Processes that could be improved

- Areas of concern among practitioners

- Difficulties faced by specific groups of people

Examples of practical research problems

Voter turnout in New England has been decreasing, in contrast to the rest of the country.

The HR department of a local chain of restaurants has a high staff turnover rate.

A non-profit organization faces a funding gap that means some of its programs will have to be cut.

Theoretical research problems

If you are doing theoretical research, you can identify a research problem by reading existing research, theory, and debates on your topic to find a gap in what is currently known about it. You might look for:

- A phenomenon or context that has not been closely studied

- A contradiction between two or more perspectives

- A situation or relationship that is not well understood

- A troubling question that has yet to be resolved

Examples of theoretical research problems

The effects of long-term Vitamin D deficiency on cardiovascular health are not well understood.

The relationship between gender, race, and income inequality has yet to be closely studied in the context of the millennial gig economy.

Historians of Scottish nationalism disagree about the role of the British Empire in the development of Scotland’s national identity.

Next, you have to find out what is already known about the problem, and pinpoint the exact aspect that your research will address.

Context and background

- Who does the problem affect?

- Is it a newly-discovered problem, or a well-established one?

- What research has already been done?

- What, if any, solutions have been proposed?

- What are the current debates about the problem? What is missing from these debates?

Specificity and relevance

- What particular place, time, and/or group of people will you focus on?

- What aspects will you not be able to tackle?

- What will the consequences be if the problem is not resolved?

Example of a specific research problem

A local non-profit organization focused on alleviating food insecurity has always fundraised from its existing support base. It lacks understanding of how best to target potential new donors. To be able to continue its work, the organization requires research into more effective fundraising strategies.

Once you have narrowed down your research problem, the next step is to formulate a problem statement , as well as your research questions or hypotheses .

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

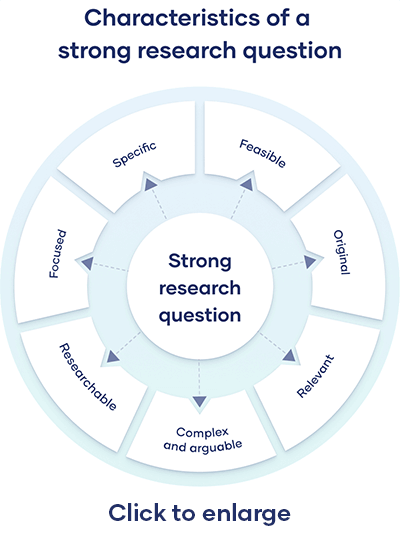

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them.

In general, they should be:

- Focused and researchable

- Answerable using credible sources

- Complex and arguable

- Feasible and specific

- Relevant and original

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, May 31). How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-problem/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a strong hypothesis | steps & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Research Questions & Hypotheses

Generally, in quantitative studies, reviewers expect hypotheses rather than research questions. However, both research questions and hypotheses serve different purposes and can be beneficial when used together.

Research Questions

Clarify the research’s aim (farrugia et al., 2010).

- Research often begins with an interest in a topic, but a deep understanding of the subject is crucial to formulate an appropriate research question.

- Descriptive: “What factors most influence the academic achievement of senior high school students?”

- Comparative: “What is the performance difference between teaching methods A and B?”

- Relationship-based: “What is the relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement?”

- Increasing knowledge about a subject can be achieved through systematic literature reviews, in-depth interviews with patients (and proxies), focus groups, and consultations with field experts.

- Some funding bodies, like the Canadian Institute for Health Research, recommend conducting a systematic review or a pilot study before seeking grants for full trials.

- The presence of multiple research questions in a study can complicate the design, statistical analysis, and feasibility.

- It’s advisable to focus on a single primary research question for the study.

- The primary question, clearly stated at the end of a grant proposal’s introduction, usually specifies the study population, intervention, and other relevant factors.

- The FINER criteria underscore aspects that can enhance the chances of a successful research project, including specifying the population of interest, aligning with scientific and public interest, clinical relevance, and contribution to the field, while complying with ethical and national research standards.

| Feasible | ||

| Interesting | ||

| Novel | ||

| Ethical | ||

| Relevant |

- The P ICOT approach is crucial in developing the study’s framework and protocol, influencing inclusion and exclusion criteria and identifying patient groups for inclusion.

| Population (patients) | ||

| Intervention (for intervention studies only) | ||

| Comparison group | ||

| Outcome of interest | ||

| Time |

- Defining the specific population, intervention, comparator, and outcome helps in selecting the right outcome measurement tool.

- The more precise the population definition and stricter the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the more significant the impact on the interpretation, applicability, and generalizability of the research findings.

- A restricted study population enhances internal validity but may limit the study’s external validity and generalizability to clinical practice.

- A broadly defined study population may better reflect clinical practice but could increase bias and reduce internal validity.

- An inadequately formulated research question can negatively impact study design, potentially leading to ineffective outcomes and affecting publication prospects.

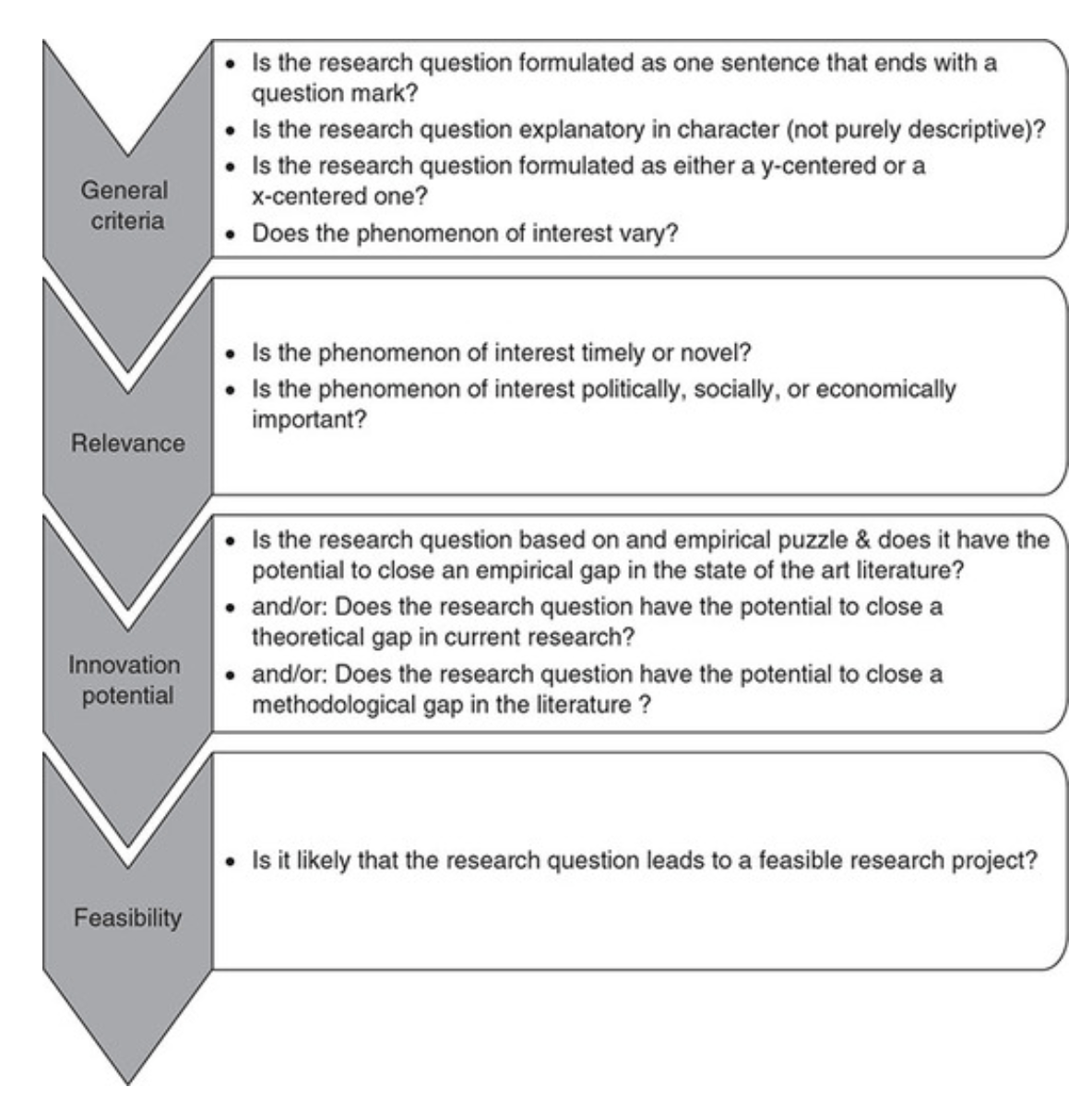

Checklist: Good research questions for social science projects (Panke, 2018)

Research Hypotheses

Present the researcher’s predictions based on specific statements.

- These statements define the research problem or issue and indicate the direction of the researcher’s predictions.

- Formulating the research question and hypothesis from existing data (e.g., a database) can lead to multiple statistical comparisons and potentially spurious findings due to chance.

- The research or clinical hypothesis, derived from the research question, shapes the study’s key elements: sampling strategy, intervention, comparison, and outcome variables.

- Hypotheses can express a single outcome or multiple outcomes.

- After statistical testing, the null hypothesis is either rejected or not rejected based on whether the study’s findings are statistically significant.

- Hypothesis testing helps determine if observed findings are due to true differences and not chance.

- Hypotheses can be 1-sided (specific direction of difference) or 2-sided (presence of a difference without specifying direction).

- 2-sided hypotheses are generally preferred unless there’s a strong justification for a 1-sided hypothesis.

- A solid research hypothesis, informed by a good research question, influences the research design and paves the way for defining clear research objectives.

Types of Research Hypothesis

- In a Y-centered research design, the focus is on the dependent variable (DV) which is specified in the research question. Theories are then used to identify independent variables (IV) and explain their causal relationship with the DV.

- Example: “An increase in teacher-led instructional time (IV) is likely to improve student reading comprehension scores (DV), because extensive guided practice under expert supervision enhances learning retention and skill mastery.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The dependent variable (student reading comprehension scores) is the focus, and the hypothesis explores how changes in the independent variable (teacher-led instructional time) affect it.

- In X-centered research designs, the independent variable is specified in the research question. Theories are used to determine potential dependent variables and the causal mechanisms at play.

- Example: “Implementing technology-based learning tools (IV) is likely to enhance student engagement in the classroom (DV), because interactive and multimedia content increases student interest and participation.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The independent variable (technology-based learning tools) is the focus, with the hypothesis exploring its impact on a potential dependent variable (student engagement).

- Probabilistic hypotheses suggest that changes in the independent variable are likely to lead to changes in the dependent variable in a predictable manner, but not with absolute certainty.

- Example: “The more teachers engage in professional development programs (IV), the more their teaching effectiveness (DV) is likely to improve, because continuous training updates pedagogical skills and knowledge.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis implies a probable relationship between the extent of professional development (IV) and teaching effectiveness (DV).

- Deterministic hypotheses state that a specific change in the independent variable will lead to a specific change in the dependent variable, implying a more direct and certain relationship.

- Example: “If the school curriculum changes from traditional lecture-based methods to project-based learning (IV), then student collaboration skills (DV) are expected to improve because project-based learning inherently requires teamwork and peer interaction.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis presumes a direct and definite outcome (improvement in collaboration skills) resulting from a specific change in the teaching method.

- Example : “Students who identify as visual learners will score higher on tests that are presented in a visually rich format compared to tests presented in a text-only format.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis aims to describe the potential difference in test scores between visual learners taking visually rich tests and text-only tests, without implying a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

- Example : “Teaching method A will improve student performance more than method B.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis compares the effectiveness of two different teaching methods, suggesting that one will lead to better student performance than the other. It implies a direct comparison but does not necessarily establish a causal mechanism.

- Example : “Students with higher self-efficacy will show higher levels of academic achievement.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis predicts a relationship between the variable of self-efficacy and academic achievement. Unlike a causal hypothesis, it does not necessarily suggest that one variable causes changes in the other, but rather that they are related in some way.

Tips for developing research questions and hypotheses for research studies

- Perform a systematic literature review (if one has not been done) to increase knowledge and familiarity with the topic and to assist with research development.

- Learn about current trends and technological advances on the topic.

- Seek careful input from experts, mentors, colleagues, and collaborators to refine your research question as this will aid in developing the research question and guide the research study.

- Use the FINER criteria in the development of the research question.

- Ensure that the research question follows PICOT format.

- Develop a research hypothesis from the research question.

- Ensure that the research question and objectives are answerable, feasible, and clinically relevant.

If your research hypotheses are derived from your research questions, particularly when multiple hypotheses address a single question, it’s recommended to use both research questions and hypotheses. However, if this isn’t the case, using hypotheses over research questions is advised. It’s important to note these are general guidelines, not strict rules. If you opt not to use hypotheses, consult with your supervisor for the best approach.

Farrugia, P., Petrisor, B. A., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2010). Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie , 53 (4), 278–281.

Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D., & Newman, T. B. (2007). Designing clinical research. Philadelphia.

Panke, D. (2018). Research design & method selection: Making good choices in the social sciences. Research Design & Method Selection , 1-368.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Problem? Characteristics, Types, and Examples

A research problem is a gap in existing knowledge, a contradiction in an established theory, or a real-world challenge that a researcher aims to address in their research. It is at the heart of any scientific inquiry, directing the trajectory of an investigation. The statement of a problem orients the reader to the importance of the topic, sets the problem into a particular context, and defines the relevant parameters, providing the framework for reporting the findings. Therein lies the importance of research problem s.

The formulation of well-defined research questions is central to addressing a research problem . A research question is a statement made in a question form to provide focus, clarity, and structure to the research endeavor. This helps the researcher design methodologies, collect data, and analyze results in a systematic and coherent manner. A study may have one or more research questions depending on the nature of the study.

Identifying and addressing a research problem is very important. By starting with a pertinent problem , a scholar can contribute to the accumulation of evidence-based insights, solutions, and scientific progress, thereby advancing the frontier of research. Moreover, the process of formulating research problems and posing pertinent research questions cultivates critical thinking and hones problem-solving skills.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Problem ?

Before you conceive of your project, you need to ask yourself “ What is a research problem ?” A research problem definition can be broadly put forward as the primary statement of a knowledge gap or a fundamental challenge in a field, which forms the foundation for research. Conversely, the findings from a research investigation provide solutions to the problem .

A research problem guides the selection of approaches and methodologies, data collection, and interpretation of results to find answers or solutions. A well-defined problem determines the generation of valuable insights and contributions to the broader intellectual discourse.

Characteristics of a Research Problem

Knowing the characteristics of a research problem is instrumental in formulating a research inquiry; take a look at the five key characteristics below:

Novel : An ideal research problem introduces a fresh perspective, offering something new to the existing body of knowledge. It should contribute original insights and address unresolved matters or essential knowledge.

Significant : A problem should hold significance in terms of its potential impact on theory, practice, policy, or the understanding of a particular phenomenon. It should be relevant to the field of study, addressing a gap in knowledge, a practical concern, or a theoretical dilemma that holds significance.

Feasible: A practical research problem allows for the formulation of hypotheses and the design of research methodologies. A feasible research problem is one that can realistically be investigated given the available resources, time, and expertise. It should not be too broad or too narrow to explore effectively, and should be measurable in terms of its variables and outcomes. It should be amenable to investigation through empirical research methods, such as data collection and analysis, to arrive at meaningful conclusions A practical research problem considers budgetary and time constraints, as well as limitations of the problem . These limitations may arise due to constraints in methodology, resources, or the complexity of the problem.

Clear and specific : A well-defined research problem is clear and specific, leaving no room for ambiguity; it should be easily understandable and precisely articulated. Ensuring specificity in the problem ensures that it is focused, addresses a distinct aspect of the broader topic and is not vague.

Rooted in evidence: A good research problem leans on trustworthy evidence and data, while dismissing unverifiable information. It must also consider ethical guidelines, ensuring the well-being and rights of any individuals or groups involved in the study.

Types of Research Problems

Across fields and disciplines, there are different types of research problems . We can broadly categorize them into three types.

- Theoretical research problems

Theoretical research problems deal with conceptual and intellectual inquiries that may not involve empirical data collection but instead seek to advance our understanding of complex concepts, theories, and phenomena within their respective disciplines. For example, in the social sciences, research problem s may be casuist (relating to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience), difference (comparing or contrasting two or more phenomena), descriptive (aims to describe a situation or state), or relational (investigating characteristics that are related in some way).

Here are some theoretical research problem examples :

- Ethical frameworks that can provide coherent justifications for artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, especially in contexts involving autonomous decision-making and moral agency.

- Determining how mathematical models can elucidate the gradual development of complex traits, such as intricate anatomical structures or elaborate behaviors, through successive generations.

- Applied research problems

Applied or practical research problems focus on addressing real-world challenges and generating practical solutions to improve various aspects of society, technology, health, and the environment.

Here are some applied research problem examples :

- Studying the use of precision agriculture techniques to optimize crop yield and minimize resource waste.

- Designing a more energy-efficient and sustainable transportation system for a city to reduce carbon emissions.

- Action research problems

Action research problems aim to create positive change within specific contexts by involving stakeholders, implementing interventions, and evaluating outcomes in a collaborative manner.

Here are some action research problem examples :

- Partnering with healthcare professionals to identify barriers to patient adherence to medication regimens and devising interventions to address them.

- Collaborating with a nonprofit organization to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs aimed at providing job training for underserved populations.

These different types of research problems may give you some ideas when you plan on developing your own.

How to Define a Research Problem

You might now ask “ How to define a research problem ?” These are the general steps to follow:

- Look for a broad problem area: Identify under-explored aspects or areas of concern, or a controversy in your topic of interest. Evaluate the significance of addressing the problem in terms of its potential contribution to the field, practical applications, or theoretical insights.

- Learn more about the problem: Read the literature, starting from historical aspects to the current status and latest updates. Rely on reputable evidence and data. Be sure to consult researchers who work in the relevant field, mentors, and peers. Do not ignore the gray literature on the subject.

- Identify the relevant variables and how they are related: Consider which variables are most important to the study and will help answer the research question. Once this is done, you will need to determine the relationships between these variables and how these relationships affect the research problem .

- Think of practical aspects : Deliberate on ways that your study can be practical and feasible in terms of time and resources. Discuss practical aspects with researchers in the field and be open to revising the problem based on feedback. Refine the scope of the research problem to make it manageable and specific; consider the resources available, time constraints, and feasibility.

- Formulate the problem statement: Craft a concise problem statement that outlines the specific issue, its relevance, and why it needs further investigation.

- Stick to plans, but be flexible: When defining the problem , plan ahead but adhere to your budget and timeline. At the same time, consider all possibilities and ensure that the problem and question can be modified if needed.

Key Takeaways

- A research problem concerns an area of interest, a situation necessitating improvement, an obstacle requiring eradication, or a challenge in theory or practical applications.

- The importance of research problem is that it guides the research and helps advance human understanding and the development of practical solutions.

- Research problem definition begins with identifying a broad problem area, followed by learning more about the problem, identifying the variables and how they are related, considering practical aspects, and finally developing the problem statement.

- Different types of research problems include theoretical, applied, and action research problems , and these depend on the discipline and nature of the study.

- An ideal problem is original, important, feasible, specific, and based on evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it important to define a research problem?

Identifying potential issues and gaps as research problems is important for choosing a relevant topic and for determining a well-defined course of one’s research. Pinpointing a problem and formulating research questions can help researchers build their critical thinking, curiosity, and problem-solving abilities.

How do I identify a research problem?

Identifying a research problem involves recognizing gaps in existing knowledge, exploring areas of uncertainty, and assessing the significance of addressing these gaps within a specific field of study. This process often involves thorough literature review, discussions with experts, and considering practical implications.

Can a research problem change during the research process?

Yes, a research problem can change during the research process. During the course of an investigation a researcher might discover new perspectives, complexities, or insights that prompt a reevaluation of the initial problem. The scope of the problem, unforeseen or unexpected issues, or other limitations might prompt some tweaks. You should be able to adjust the problem to ensure that the study remains relevant and aligned with the evolving understanding of the subject matter.

How does a research problem relate to research questions or hypotheses?

A research problem sets the stage for the study. Next, research questions refine the direction of investigation by breaking down the broader research problem into manageable components. Research questions are formulated based on the problem , guiding the investigation’s scope and objectives. The hypothesis provides a testable statement to validate or refute within the research process. All three elements are interconnected and work together to guide the research.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

How Does R Discovery’s Interplatform Capability Enhance Research Accessibility

What is Convenience Sampling: Definition, Method, and Examples

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg

- v.24(1); Jan-Mar 2019

Formulation of Research Question – Stepwise Approach

Simmi k. ratan.

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India

1 Department of Community Medicine, North Delhi Municipal Corporation Medical College, New Delhi, India

2 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Batra Hospital and Research Centre, New Delhi, India

Formulation of research question (RQ) is an essentiality before starting any research. It aims to explore an existing uncertainty in an area of concern and points to a need for deliberate investigation. It is, therefore, pertinent to formulate a good RQ. The present paper aims to discuss the process of formulation of RQ with stepwise approach. The characteristics of good RQ are expressed by acronym “FINERMAPS” expanded as feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant, manageable, appropriate, potential value, publishability, and systematic. A RQ can address different formats depending on the aspect to be evaluated. Based on this, there can be different types of RQ such as based on the existence of the phenomenon, description and classification, composition, relationship, comparative, and causality. To develop a RQ, one needs to begin by identifying the subject of interest and then do preliminary research on that subject. The researcher then defines what still needs to be known in that particular subject and assesses the implied questions. After narrowing the focus and scope of the research subject, researcher frames a RQ and then evaluates it. Thus, conception to formulation of RQ is very systematic process and has to be performed meticulously as research guided by such question can have wider impact in the field of social and health research by leading to formulation of policies for the benefit of larger population.

I NTRODUCTION

A good research question (RQ) forms backbone of a good research, which in turn is vital in unraveling mysteries of nature and giving insight into a problem.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] RQ identifies the problem to be studied and guides to the methodology. It leads to building up of an appropriate hypothesis (Hs). Hence, RQ aims to explore an existing uncertainty in an area of concern and points to a need for deliberate investigation. A good RQ helps support a focused arguable thesis and construction of a logical argument. Hence, formulation of a good RQ is undoubtedly one of the first critical steps in the research process, especially in the field of social and health research, where the systematic generation of knowledge that can be used to promote, restore, maintain, and/or protect health of individuals and populations.[ 1 , 3 , 4 ] Basically, the research can be classified as action, applied, basic, clinical, empirical, administrative, theoretical, or qualitative or quantitative research, depending on its purpose.[ 2 ]

Research plays an important role in developing clinical practices and instituting new health policies. Hence, there is a need for a logical scientific approach as research has an important goal of generating new claims.[ 1 ]

C HARACTERISTICS OF G OOD R ESEARCH Q UESTION

“The most successful research topics are narrowly focused and carefully defined but are important parts of a broad-ranging, complex problem.”

A good RQ is an asset as it:

- Details the problem statement

- Further describes and refines the issue under study

- Adds focus to the problem statement

- Guides data collection and analysis

- Sets context of research.

Hence, while writing RQ, it is important to see if it is relevant to the existing time frame and conditions. For example, the impact of “odd-even” vehicle formula in decreasing the level of air particulate pollution in various districts of Delhi.

A good research is represented by acronym FINERMAPS[ 5 ]

Interesting.

- Appropriate

- Potential value and publishability

- Systematic.

Feasibility means that it is within the ability of the investigator to carry out. It should be backed by an appropriate number of subjects and methodology as well as time and funds to reach the conclusions. One needs to be realistic about the scope and scale of the project. One has to have access to the people, gadgets, documents, statistics, etc. One should be able to relate the concepts of the RQ to the observations, phenomena, indicators, or variables that one can access. One should be clear that the collection of data and the proceedings of project can be completed within the limited time and resources available to the investigator. Sometimes, a RQ appears feasible, but when fieldwork or study gets started, it proves otherwise. In this situation, it is important to write up the problems honestly and to reflect on what has been learned. One should try to discuss with more experienced colleagues or the supervisor so as to develop a contingency plan to anticipate possible problems while working on a RQ and find possible solutions in such situations.

This is essential that one has a real grounded interest in one's RQ and one can explore this and back it up with academic and intellectual debate. This interest will motivate one to keep going with RQ.

The question should not simply copy questions investigated by other workers but should have scope to be investigated. It may aim at confirming or refuting the already established findings, establish new facts, or find new aspects of the established facts. It should show imagination of the researcher. Above all, the question has to be simple and clear. The complexity of a question can frequently hide unclear thoughts and lead to a confused research process. A very elaborate RQ, or a question which is not differentiated into different parts, may hide concepts that are contradictory or not relevant. This needs to be clear and thought-through. Having one key question with several subcomponents will guide your research.

This is the foremost requirement of any RQ and is mandatory to get clearance from appropriate authorities before stating research on the question. Further, the RQ should be such that it minimizes the risk of harm to the participants in the research, protect the privacy and maintain their confidentiality, and provide the participants right to withdraw from research. It should also guide in avoiding deceptive practices in research.

The question should of academic and intellectual interest to people in the field you have chosen to study. The question preferably should arise from issues raised in the current situation, literature, or in practice. It should establish a clear purpose for the research in relation to the chosen field. For example, filling a gap in knowledge, analyzing academic assumptions or professional practice, monitoring a development in practice, comparing different approaches, or testing theories within a specific population are some of the relevant RQs.

Manageable (M): It has the similar essence as of feasibility but mainly means that the following research can be managed by the researcher.

Appropriate (A): RQ should be appropriate logically and scientifically for the community and institution.

Potential value and publishability (P): The study can make significant health impact in clinical and community practices. Therefore, research should aim for significant economic impact to reduce unnecessary or excessive costs. Furthermore, the proposed study should exist within a clinical, consumer, or policy-making context that is amenable to evidence-based change. Above all, a good RQ must address a topic that has clear implications for resolving important dilemmas in health and health-care decisions made by one or more stakeholder groups.

Systematic (S): Research is structured with specified steps to be taken in a specified sequence in accordance with the well-defined set of rules though it does not rule out creative thinking.

Example of RQ: Would the topical skin application of oil as a skin barrier reduces hypothermia in preterm infants? This question fulfills the criteria of a good RQ, that is, feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant.

Types of research question

A RQ can address different formats depending on the aspect to be evaluated.[ 6 ] For example:

- Existence: This is designed to uphold the existence of a particular phenomenon or to rule out rival explanation, for example, can neonates perceive pain?

- Description and classification: This type of question encompasses statement of uniqueness, for example, what are characteristics and types of neuropathic bladders?

- Composition: It calls for breakdown of whole into components, for example, what are stages of reflux nephropathy?

- Relationship: Evaluate relation between variables, for example, association between tumor rupture and recurrence rates in Wilm's tumor

- Descriptive—comparative: Expected that researcher will ensure that all is same between groups except issue in question, for example, Are germ cell tumors occurring in gonads more aggressive than those occurring in extragonadal sites?

- Causality: Does deletion of p53 leads to worse outcome in patients with neuroblastoma?

- Causality—comparative: Such questions frequently aim to see effect of two rival treatments, for example, does adding surgical resection improves survival rate outcome in children with neuroblastoma than with chemotherapy alone?

- Causality–Comparative interactions: Does immunotherapy leads to better survival outcome in neuroblastoma Stage IV S than with chemotherapy in the setting of adverse genetic profile than without it? (Does X cause more changes in Y than those caused by Z under certain condition and not under other conditions).

How to develop a research question

- Begin by identifying a broader subject of interest that lends itself to investigate, for example, hormone levels among hypospadias

- Do preliminary research on the general topic to find out what research has already been done and what literature already exists.[ 7 ] Therefore, one should begin with “information gaps” (What do you already know about the problem? For example, studies with results on testosterone levels among hypospadias

- What do you still need to know? (e.g., levels of other reproductive hormones among hypospadias)

- What are the implied questions: The need to know about a problem will lead to few implied questions. Each general question should lead to more specific questions (e.g., how hormone levels differ among isolated hypospadias with respect to that in normal population)

- Narrow the scope and focus of research (e.g., assessment of reproductive hormone levels among isolated hypospadias and hypospadias those with associated anomalies)

- Is RQ clear? With so much research available on any given topic, RQs must be as clear as possible in order to be effective in helping the writer direct his or her research

- Is the RQ focused? RQs must be specific enough to be well covered in the space available

- Is the RQ complex? RQs should not be answerable with a simple “yes” or “no” or by easily found facts. They should, instead, require both research and analysis on the part of the writer

- Is the RQ one that is of interest to the researcher and potentially useful to others? Is it a new issue or problem that needs to be solved or is it attempting to shed light on previously researched topic

- Is the RQ researchable? Consider the available time frame and the required resources. Is the methodology to conduct the research feasible?

- Is the RQ measurable and will the process produce data that can be supported or contradicted?

- Is the RQ too broad or too narrow?

- Create Hs: After formulating RQ, think where research is likely to be progressing? What kind of argument is likely to be made/supported? What would it mean if the research disputed the planned argument? At this step, one can well be on the way to have a focus for the research and construction of a thesis. Hs consists of more specific predictions about the nature and direction of the relationship between two variables. It is a predictive statement about the outcome of the research, dictate the method, and design of the research[ 1 ]

- Understand implications of your research: This is important for application: whether one achieves to fill gap in knowledge and how the results of the research have practical implications, for example, to develop health policies or improve educational policies.[ 1 , 8 ]

Brainstorm/Concept map for formulating research question

- First, identify what types of studies have been done in the past?

- Is there a unique area that is yet to be investigated or is there a particular question that may be worth replicating?

- Begin to narrow the topic by asking open-ended “how” and “why” questions

- Evaluate the question

- Develop a Hypothesis (Hs)

- Write down the RQ.

Writing down the research question

- State the question in your own words

- Write down the RQ as completely as possible.

For example, Evaluation of reproductive hormonal profile in children presenting with isolated hypospadias)

- Divide your question into concepts. Narrow to two or three concepts (reproductive hormonal profile, isolated hypospadias, compare with normal/not isolated hypospadias–implied)

- Specify the population to be studied (children with isolated hypospadias)

- Refer to the exposure or intervention to be investigated, if any

- Reflect the outcome of interest (hormonal profile).

Another example of a research question

Would the topical skin application of oil as a skin barrier reduces hypothermia in preterm infants? Apart from fulfilling the criteria of a good RQ, that is, feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant, it also details about the intervention done (topical skin application of oil), rationale of intervention (as a skin barrier), population to be studied (preterm infants), and outcome (reduces hypothermia).

Other important points to be heeded to while framing research question

- Make reference to a population when a relationship is expected among a certain type of subjects

- RQs and Hs should be made as specific as possible

- Avoid words or terms that do not add to the meaning of RQs and Hs

- Stick to what will be studied, not implications

- Name the variables in the order in which they occur/will be measured

- Avoid the words significant/”prove”

- Avoid using two different terms to refer to the same variable.

Some of the other problems and their possible solutions have been discussed in Table 1 .

Potential problems and solutions while making research question

G OING B EYOND F ORMULATION OF R ESEARCH Q UESTION–THE P ATH A HEAD

Once RQ is formulated, a Hs can be developed. Hs means transformation of a RQ into an operational analog.[ 1 ] It means a statement as to what prediction one makes about the phenomenon to be examined.[ 4 ] More often, for case–control trial, null Hs is generated which is later accepted or refuted.

A strong Hs should have following characteristics:

- Give insight into a RQ

- Are testable and measurable by the proposed experiments

- Have logical basis

- Follows the most likely outcome, not the exceptional outcome.

E XAMPLES OF R ESEARCH Q UESTION AND H YPOTHESIS

Research question-1.

- Does reduced gap between the two segments of the esophagus in patients of esophageal atresia reduces the mortality and morbidity of such patients?

Hypothesis-1

- Reduced gap between the two segments of the esophagus in patients of esophageal atresia reduces the mortality and morbidity of such patients

- In pediatric patients with esophageal atresia, gap of <2 cm between two segments of the esophagus and proper mobilization of proximal pouch reduces the morbidity and mortality among such patients.

Research question-2

- Does application of mitomycin C improves the outcome in patient of corrosive esophageal strictures?

Hypothesis-2

In patients aged 2–9 years with corrosive esophageal strictures, 34 applications of mitomycin C in dosage of 0.4 mg/ml for 5 min over a period of 6 months improve the outcome in terms of symptomatic and radiological relief. Some other examples of good and bad RQs have been shown in Table 2 .

Examples of few bad (left-hand side column) and few good (right-hand side) research questions

R ESEARCH Q UESTION AND S TUDY D ESIGN

RQ determines study design, for example, the question aimed to find the incidence of a disease in population will lead to conducting a survey; to find risk factors for a disease will need case–control study or a cohort study. RQ may also culminate into clinical trial.[ 9 , 10 ] For example, effect of administration of folic acid tablet in the perinatal period in decreasing incidence of neural tube defect. Accordingly, Hs is framed.

Appropriate statistical calculations are instituted to generate sample size. The subject inclusion, exclusion criteria and time frame of research are carefully defined. The detailed subject information sheet and pro forma are carefully defined. Moreover, research is set off few examples of research methodology guided by RQ:

- Incidence of anorectal malformations among adolescent females (hospital-based survey)

- Risk factors for the development of spontaneous pneumoperitoneum in pediatric patients (case–control design and cohort study)

- Effect of technique of extramucosal ureteric reimplantation without the creation of submucosal tunnel for the preservation of upper tract in bladder exstrophy (clinical trial).

The results of the research are then be available for wider applications for health and social life

C ONCLUSION

A good RQ needs thorough literature search and deep insight into the specific area/problem to be investigated. A RQ has to be focused yet simple. Research guided by such question can have wider impact in the field of social and health research by leading to formulation of policies for the benefit of larger population.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

R EFERENCES

- How To Formulate A Research Problem

Introduction

In the dynamic realm of academia, research problems serve as crucial stepping stones for groundbreaking discoveries and advancements. Research problems lay the groundwork for inquiry and exploration that happens when conducting research. They direct the path toward knowledge expansion.

In this blog post, we will discuss the different ways you can identify and formulate a research problem. We will also highlight how you can write a research problem, its significance in guiding your research journey, and how it contributes to knowledge advancement.

Understanding the Essence of a Research Problem

A research problem is defined as the focal point of any academic inquiry. It is a concise and well-defined statement that outlines the specific issue or question that the research aims to address. This research problem usually sets the tone for the entire study and provides you, the researcher, with a clear purpose and a clear direction on how to go about conducting your research.

There are two ways you can consider what the purpose of your research problem is. The first way is that the research problem helps you define the scope of your study and break down what you should focus on in the research. The essence of this is to ensure that you embark on a relevant study and also easily manage it.

The second way is that having a research problem helps you develop a step-by-step guide in your research exploration and execution. It directs your efforts and determines the type of data you need to collect and analyze. Furthermore, a well-developed research problem is really important because it contributes to the credibility and validity of your study.

It also demonstrates the significance of your research and its potential to contribute new knowledge to the existing body of literature in the world. A compelling research problem not only captivates the attention of your peers but also lays the foundation for impactful and meaningful research outcomes.

Identifying a Research Problem

To identify a research problem, you need a systematic approach and a deep understanding of the subject area. Below are some steps to guide you in this process:

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before you dive into your research problem, ensure you get familiar with the existing literature in your field. Analyze gaps, controversies, and unanswered questions. This will help you identify areas where your research can make a meaningful contribution.

- Consult with Peers and Mentors: Participate in discussions with your peers and mentors to gain insights and feedback on potential research problems. Their perspectives can help you refine and validate your ideas.

- Define Your Research Objectives: Clearly outline the objectives of your study. What do you want to achieve through your research? What specific outcomes are you aiming for?

Formulating a Research Problem

Once you have identified the general area of interest and specific research objectives, you can then formulate your research problem. Things to consider when formulating a research problem:

- Clarity and Specificity: Your research problem should be concise, specific, and devoid of ambiguity. Avoid vague statements that could lead to confusion or misinterpretation.

- Originality: Strive to formulate a research problem that addresses a unique and unexplored aspect of your field. Originality is key to making a meaningful contribution to the existing knowledge.

- Feasibility: Ensure that your research problem is feasible within the constraints of time, resources, and available data. Unrealistic research problems can hinder the progress of your study.

- Refining the Research Problem: It is common for the research problem to evolve as you delve deeper into your study. Don’t be afraid to refine and revise your research problem if necessary. Seek feedback from colleagues, mentors, and experts in your field to ensure the strength and relevance of your research problem.

How Do You Write a Research Problem?

Steps to consider in writing a Research Problem:

- Select a Topic: The first step in writing a research problem is to select a specific topic of interest within your field of study. This topic should be relevant, and meaningful, and have the potential to contribute to existing knowledge.

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before formulating your research problem, conduct a thorough literature review to understand the current state of research on your chosen topic. This will help you identify gaps, controversies, or areas that need further exploration.

- Identify the Research Gap: Based on your literature review, pinpoint the specific gap or problem that your research aims to address. This gap should be something that has not been adequately studied or resolved in previous research.

- Be Specific and Clear: The research problem should be framed in a clear and concise manner. It should be specific enough to guide your research but broad enough to allow for meaningful investigation.

- Ensure Feasibility: Consider the resources and constraints available to you when formulating the research problem. Ensure that it is feasible to address the problem within the scope of your study.

- Align your Research Goals: The research problem should align with the overall goals and objectives of your study. It should be directly related to the research questions you intend to answer.

Related: How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Research Problem vs Research Questions

Research Problem: The research problem is a broad statement that outlines the overarching issue or gap in knowledge that your research aims to address. It provides the context and motivation for your study and helps establish its significance and relevance. The research problem is typically stated in the introduction section of your research proposal or thesis.

Research Questions: Research questions are specific inquiries that you seek to answer through your research. These questions are derived from the research problem and help guide the focus of your study. They are often more detailed and narrow in scope compared to the research problem. Research questions are usually listed in the methodology section of your research proposal or thesis.

Difference Between a Research Problem and a Research Topic

Research Problem: A research problem is a specific issue, gap, or question that requires investigation and can be addressed through research. It is a clearly defined and focused problem that the researcher aims to solve or explore. The research problem provides the context and rationale for the study and guides the research process. It is usually stated as a question or a statement in the introduction section of a research proposal or thesis.

Example of a Research Problem: “ What are the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the online retail industry ?”

Research Topic: A research topic, on the other hand, is a broader subject or area of interest within a particular field of study. It is a general idea or subject that the researcher wants to explore in their research. The research topic is more general and does not yet specify a specific problem or question to be addressed. It serves as the starting point for the research, and the researcher further refines it to formulate a specific research problem.

Example of a Research Topic: “ Consumer behavior in the online retail industry.”

In summary, a research topic is a general area of interest, while a research problem is a specific issue or question within that area that the researcher aims to investigate.

Difference Between a Research Problem and Problem Statement

Research Problem: As explained earlier, a research problem is a specific issue, gap, or question that you as a researcher aim to address through your research. It is a clear and concise statement that defines the focus of the study and provides a rationale for why it is worth investigating.

Example of a Research Problem: “What is the impact of social media usage on the mental health and well-being of adolescents?”

Problem Statement: The problem statement, on the other hand, is a brief and clear description of the problem that you want to solve or investigate. It is more focused and specific than the research problem and provides a snapshot of the main issue being addressed.

Example of a Problem Statement: “ The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between social media usage and the mental health outcomes of adolescents, with a focus on depression, anxiety, and self-esteem.”

In summary, a research problem is the broader issue or question guiding the study, while the problem statement is a concise description of the specific problem being addressed in the research. The problem statement is usually found in the introduction section of a research proposal or thesis.

Challenges and Considerations

Formulating a research problem involves several challenges and considerations that researchers should carefully address:

- Feasibility: Before you finalize a research problem, it is crucial to assess its feasibility. Consider the availability of resources, time, and expertise required to conduct the research. Evaluate potential constraints and determine if the research problem can be realistically tackled within the given limitations.

- Novelty and Contribution: A well-crafted research problem should aim to contribute to existing knowledge in the field. Ensure that your research problem addresses a gap in the literature or provides innovative insights. Review past studies to understand what has already been done and how your research can build upon or offer something new.

- Ethical and Social Implications: Take into account the ethical and social implications of your research problem. Research involving human subjects or sensitive topics requires ethical considerations. Consider the potential impact of your research on individuals, communities, or society as a whole.

- Scope and Focus: Be mindful of the scope of your research problem. A problem that is too broad may be challenging to address comprehensively, while one that is too narrow might limit the significance of the findings. Strike a balance between a focused research problem that can be thoroughly investigated and one that has broader implications.

- Clear Objectives: Ensure that your research problem aligns with specific research objectives. Clearly define what you intend to achieve through your study. Having well-defined objectives will help you stay on track and maintain clarity throughout the research process.

- Relevance and Significance: Consider the relevance and significance of your research problem in the context of your field of study. Assess its potential implications for theory, practice, or policymaking. A research problem that addresses important questions and has practical implications is more likely to be valuable to the academic community and beyond.

- Stakeholder Involvement: In some cases, involving relevant stakeholders early in the process of formulating a research problem can be beneficial. This could include experts in the field, practitioners, or individuals who may be impacted by the research. Their input can provide valuable insights that can help you enhance the quality of the research problem.

In conclusion, understanding how to formulate a research problem is fundamental for you to have meaningful research and intellectual growth. Remember that a well-crafted research problem serves as the foundation for groundbreaking discoveries and advancements in various fields. It not only enhances the credibility and relevance of your study but also contributes to the expansion of knowledge and the betterment of society.

Therefore, put more effort into the process of identifying and formulating research problems with enthusiasm and curiosity. Engage in comprehensive literature reviews, observe your surroundings, and reflect on the gaps in existing knowledge. Lastly, don’t forget to be mindful of the challenges and considerations, and ensure your research problem aligns with clear objectives and ethical principles.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- problem statements

- research objectives

- research problem vs research topic

- research problems

- research studies

You may also like:

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Sources of Data For Research: Types & Examples

Introduction In the age of information, data has become the driving force behind decision-making and innovation. Whether in business,...

Defining Research Objectives: How To Write Them

Almost all industries use research for growth and development. Research objectives are how researchers ensure that their study has...

Naive vs Non Naive Participants In Research: Meaning & Implications

Introduction In research studies, naive and non-naive participant information alludes to the degree of commonality and understanding...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25