410.531.1610 | [email protected]

- Search Search for:

Performance Task Blog Series # 1 – What is a performance task?

A performance task is any learning activity or assessment that asks students to perform to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding and proficiency. Performance tasks yield a tangible product and/or performance that serve as evidence of learning. Unlike a selected-response item (e.g., multiple-choice or matching) that asks students to select from given alternatives, a performance task presents a situation that calls for learners to apply their learning in context.

Performance tasks are routinely used in certain disciplines, such as visual and performing arts, physical education, and career-technology where performance is the natural focus of instruction. However, such tasks can (and should) be used in every subject area and at all grade levels.

Characteristics of Performance Tasks

While any performance by a learner might be considered a performance task (e.g., tying a shoe or drawing a picture), it is useful to distinguish between the application of specific and discrete skills (e.g., dribbling a basketball) from genuine performance in context (e.g., playing the game of basketball in which dribbling is one of many applied skills). Thus, when I use the term performance tasks, I am referring to more complex and authentic performances.

Here are seven general characteristics of performance tasks:

- Performance tasks call for the application of knowledge and skills, not just recall or recognition.

In other words, the learner must actually use their learning to perform . These tasks typically yield a tangible product (e.g., graphic display, blog post) or performance (e.g., oral presentation, debate) that serve as evidence of their understanding and proficiency.

- Performance tasks are open-ended and typically do not yield a single, correct answer.

Unlike selected- or brief constructed- response items that seek a “right” answer, performance tasks are open-ended. Thus, there can be different responses to the task that still meet success criteria. These tasks are also open in terms of process; i.e., there is typically not a single way of accomplishing the task.

- Performance tasks establish novel and authentic contexts for performance.

These tasks present realistic conditions and constraints for students to navigate. For example, a mathematics task would present students with a never-before-seen problem that cannot be solved by simply “plugging in” numbers into a memorized algorithm. In an authentic task, students need to consider goals, audience, obstacles, and options to achieve a successful product or performance. Authentic tasks have a side benefit – they convey purpose and relevance to students, helping learners see a reason for putting forth effort in preparing for them.

- Performance tasks provide evidence of understanding via transfer.

Understanding is revealed when students can transfer their learning to new and “messy” situations. Note that not all performances require transfer. For example, playing a musical instrument by following the notes or conducting a step-by-step science lab require minimal transfer. In contrast, rich performance tasks are open-ended and call “higher-order thinking” and the thoughtful application of knowledge and skills in context, rather than a scripted or formulaic performance.

- Performance tasks are multi-faceted.

Unlike traditional test “items” that typically assess a single skill or fact, performance tasks are more complex. They involve multiple steps and thus can be used to assess several standards or outcomes.

- Performance tasks can integrate two or more subjects as well as 21 st century skills.

In the wider world beyond the school, most issues and problems do not present themselves neatly within subject area “silos.” While performance tasks can certainly be content-specific (e.g., mathematics, science, social studies), they also provide a vehicle for integrating two or more subjects and/or weaving in 21 st century skills and Habits of Mind. One natural way of integrating subjects is to include a reading, research, and/or communication component (e.g., writing, graphics, oral or technology presentation) to tasks in content areas like social studies, science, health, business, health/physical education. Such tasks encourage students to see meaningful learning as integrated, rather than something that occurs in isolated subjects and segments.

- Performances on open-ended tasks are evaluated with established criteria and rubrics.

Since these tasks do not yield a single answer, student products and performances should be judged against appropriate criteria aligned to the goals being assessed. Clearly defined and aligned criteria enable defensible, judgment-based evaluation. More detailed scoring rubrics, based on criteria, are used to profile varying levels of understanding and proficiency.

Let’s look at a few examples of performance tasks that reflect these characteristics:

Botanical Design (upper elementary)

Check out the full performance task at: http://dlrn.us?bdrhs

Evaluate the Claim (upper elementary/ middle school)

Moving to South America (middle school)

Your task is to research potential home locations by examining relevant geographic, climatic, political, economic, historic, and cultural considerations. Then, write a letter to your aunt and uncle with your recommendation about a place for them to move. Be sure to explain your decision with reasons and evidence from your research.

Accident Scene Investigation (high school)

Your team will share this information with the public through the various media resources owned and operated by the newspaper.

Check out the full performance task at: http://dlrn.us?qfl3p

In sum, performance tasks like these can be used to engage students in meaningful learning. Since rich performance tasks establish authentic contexts that reflect genuine applications of knowledge, students are often motivated and engaged by such “real world” challenges.

When used as assessments, performance tasks enable teachers to gauge student understanding and proficiency with complex processes (e.g., research, problem solving, and writing), not just measure discrete knowledge. They are well suited to integrating subject areas and linking content knowledge with the 21st Century Skills such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, communication, and technology use. Moreover, performance-based assessment can also elicit Habits of Mind, such as precision and perseverance.

See original post at: http://www.performancetask.com/what-is-a-performance-task/

Upcoming Conferences & Workshops

Teaching for deeper learning – 4-day virtual academy , creating an understanding-based curriculum and assessment system for modern learning, learn more about jay mctighe’s latest book.

Watch Book Chat Video

Get instant access to detailed competitive research, SWOT analysis, buyer personas, growth opportunities and more for any product or business at the push of a button, so that you can focus more on strategy and execution.

Table of contents, exploring effective performance task examples.

- 8 May, 2024

Introduction to Performance Based Assessment

Performance based assessment is a valuable approach in education that goes beyond traditional methods of evaluating student learning. It provides a more comprehensive and authentic measurement of students’ knowledge, skills, and abilities. This section will delve into understanding performance tasks and highlight the importance of performance assessment.

Understanding Performance Tasks

Performance tasks are assessments that require students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills by completing real-world tasks or projects. Unlike traditional assessments that rely on multiple-choice questions or written exams, performance tasks allow students to apply their learning in practical and meaningful ways.

These tasks often require students to solve problems, analyze information, conduct experiments, create products, or deliver presentations. By engaging in these hands-on activities, students can showcase their understanding, critical thinking abilities, and creativity. Performance tasks provide a more accurate representation of students’ abilities and allow for a deeper understanding of their strengths and areas for growth.

Importance of Performance Assessment

Performance assessment plays a crucial role in evaluating students’ learning outcomes and informing instructional practices. Here are some key reasons why performance assessment is important:

Authentic Assessment : Performance tasks provide a more authentic assessment of students’ abilities as they mirror real-world scenarios and tasks. This authenticity allows students to demonstrate their skills and knowledge in a context that closely resembles what they will encounter in their future endeavors.

Holistic Evaluation : Performance tasks enable educators to assess multiple dimensions of student learning, including content knowledge, problem-solving abilities, communication skills, and collaboration. This holistic evaluation provides a more comprehensive understanding of students’ overall performance.

Higher-order Thinking Skills : Performance tasks emphasize higher-order thinking skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. These skills are essential for success in the 21st century, where students need to apply their knowledge to real-world situations and think critically to solve complex problems.

Engagement and Motivation : Performance tasks often require active participation and engagement from students. By working on meaningful and relevant tasks, students are more likely to be motivated and invested in their learning. This can lead to increased retention of knowledge and deeper understanding of concepts.

By incorporating performance based assessment into educational practices, educators can gain a more comprehensive picture of students’ abilities, foster deeper learning, and prepare students for success in the real world. In the upcoming sections, we will explore different types of performance tasks and provide examples to illustrate their application in various subjects.

Types of Performance Tasks

Performance tasks are a valuable form of performance assessment in education that allow students to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities in real-world contexts. They provide a more authentic and holistic view of a student’s capabilities compared to traditional tests and exams. In this section, we will explore three common types of performance tasks: project-based assessments, portfolio assessments, and presentation assessments.

Project-Based Assessments

Project-based assessments require students to complete a hands-on project that demonstrates their understanding and application of key concepts. These projects can be interdisciplinary and allow students to showcase their creativity, problem-solving skills, and critical thinking abilities. Examples of project-based assessments include:

- Designing and building a model of a sustainable city to showcase knowledge of urban planning, environmental science, and engineering.

- Creating a multimedia presentation on a historical event, incorporating research, analysis, and communication skills.

Project-based assessments often involve multiple steps, from planning and research to execution and presentation. They provide students with an opportunity to engage in meaningful and relevant tasks, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Portfolio Assessments

Portfolio assessments involve the collection and evaluation of a student’s work over a period of time. Students compile samples of their best work, which may include essays, projects, artwork, or other artifacts that demonstrate their growth and proficiency in specific areas. These portfolios serve as a reflection of a student’s progress and allow for self-assessment. Examples of portfolio assessments include:

- A writing portfolio showcasing a student’s growth in writing skills over the course of a semester or academic year.

- An art portfolio displaying a student’s development of artistic techniques and creativity.

Portfolio assessments provide a comprehensive view of a student’s abilities and growth over time. They offer opportunities for self-reflection and self-assessment, as well as the chance for educators to provide meaningful feedback.

Presentation Assessments

Presentation assessments require students to deliver a formal presentation or demonstration of their knowledge and skills. Students must effectively communicate their ideas, engage their audience, and showcase their understanding of the subject matter. Examples of presentation assessments include:

- Delivering a persuasive speech on a social issue, incorporating research, evidence, and persuasive techniques.

- Presenting a science experiment and explaining the scientific principles behind it.

Presentation assessments not only assess a student’s knowledge and understanding but also focus on their communication and presentation skills. They promote effective communication, public speaking abilities, and the ability to synthesize and present information in a clear and engaging manner.

By incorporating these various types of performance tasks into the curriculum, educators can create a more engaging and authentic learning experience for students. It allows students to apply their knowledge and skills in meaningful ways, preparing them for real-world challenges. To explore more examples of performance-based assessment, refer to our article on performance-based assessment examples .

Examples of Performance Tasks

Performance tasks provide students with opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge and skills in real-world contexts. Here are three examples of performance tasks across different subject areas:

Science Performance Task Example

Title: Investigating Water Quality in Local Streams

Description: In this science performance task, students will be tasked with investigating the water quality of local streams in their community. They will design and conduct experiments, collect and analyze water samples, and interpret the data to evaluate the overall health of the streams. Students will also identify potential sources of pollution and propose strategies for improving water quality.

Assessment Criteria:

- Experimental design and methodology

- Data collection and analysis

- Interpretation of results

- Identification of pollution sources

- Proposed strategies for improving water quality

To learn more about performance assessment in education, visit our article on performance assessment .

Math Performance Task Example

Title: Designing a Sustainable Garden

Description: In this math performance task, students will apply their mathematical skills to design a sustainable garden. They will calculate the area of the garden, determine the optimal placement of plants, plan irrigation systems, and estimate the cost of materials. Students will also analyze the environmental impact of their design and propose ways to minimize water usage and waste.

- Accuracy of area calculations

- Design layout and organization

- Efficiency of irrigation system

- Cost estimation and budgeting

- Consideration of environmental factors

For more authentic assessment examples, including performance-based assessment, visit our article on authentic assessment .

Language Arts Performance Task Example

Title: Creating a Podcast on Social Issues

Description: In this language arts performance task, students will create a podcast that addresses a social issue of their choice. They will conduct research, develop a script, and record an engaging podcast episode. Students will demonstrate their ability to effectively communicate their ideas, use persuasive language, and engage with their audience. They will also incorporate relevant evidence and examples to support their arguments.

- Clarity and coherence of ideas

- Use of persuasive language

- Effective use of evidence and examples

- Organization and structure of the podcast

- Engagement with the audience

To explore more performance-based assessment examples, including project-based assessments, visit our article on performance-based assessment .

These examples highlight the diverse ways in which performance tasks can be implemented across different subjects. By providing students with authentic and meaningful tasks, educators can assess their knowledge, skills, and abilities in a way that goes beyond traditional tests and exams.

Designing Effective Performance Tasks

When it comes to designing effective performance tasks, there are two key factors to consider: clear objectives and criteria, as well as authenticity and relevance.

Clear Objectives and Criteria

One of the most important aspects of designing effective performance tasks is to establish clear objectives and criteria. This involves defining what students are expected to know and be able to do, as well as the specific criteria by which their performance will be assessed.

Clear objectives help provide a focus for both teachers and students, ensuring that the task aligns with the desired learning outcomes. Objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). By clearly articulating the goals of the task, teachers can guide students towards success and provide meaningful feedback based on the established criteria.

In addition to clear objectives, well-defined criteria are essential for effective performance assessment. Criteria outline the specific qualities or characteristics that will be evaluated during the task. These criteria can include elements such as content knowledge, problem-solving skills, creativity, communication, and collaboration. By explicitly stating the criteria, teachers provide students with a clear understanding of what is expected and enable consistent and fair evaluation.

Authenticity and Relevance

Another crucial aspect of designing effective performance tasks is ensuring authenticity and relevance. Performance tasks should reflect real-world scenarios and situations, allowing students to apply their knowledge and skills in meaningful ways. Authentic tasks provide opportunities for students to demonstrate their abilities in contexts that mirror the complexities of the world beyond the classroom.

By incorporating authentic and relevant tasks, students can develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter and its practical applications. This approach also helps foster engagement and motivation, as students can see the direct relevance and value of what they are learning.

When designing performance tasks, consider real-world examples and contexts that allow students to showcase their knowledge and skills. For example, in a science class, students could design and conduct experiments to investigate a specific scientific phenomenon. In mathematics, students could solve real-life problems that require the application of mathematical concepts.

By designing tasks that have clear objectives and criteria, as well as authenticity and relevance, educators can create meaningful and effective performance assessments. These assessments not only measure students’ understanding and abilities but also provide valuable learning experiences that prepare them for real-world challenges. For more examples of performance-based assessment, be sure to check out our article on performance based assessment examples .

Implementing Performance Tasks

Once you have selected the appropriate performance tasks for your curriculum, it’s important to consider how to effectively implement them. This involves determining the assessment methods and developing rubrics to evaluate student performance.

Assessment Methods

Implementing performance tasks requires careful consideration of assessment methods. These methods should align with the nature of the task and provide valuable insights into student learning and growth.

There are various assessment methods that can be used to evaluate performance tasks, including:

Direct Observation : This method involves observing students as they engage in the performance task. It allows for real-time assessment of skills, knowledge, and application. Direct observation is particularly effective for tasks that involve hands-on activities or presentations.

Product Evaluation : In this method, student work or products are evaluated based on predetermined criteria. This could involve assessing the quality, creativity, and completeness of a project or portfolio. Product evaluation is commonly used in project-based assessments and portfolio assessments.

Self-Assessment and Reflection : Encouraging students to reflect on their own performance can be a valuable assessment method. Through self-assessment, students develop metacognitive skills and gain a deeper understanding of their strengths and areas for improvement. This method can be incorporated into performance tasks through self-reflection prompts and portfolios.

Peer Assessment : Peer assessment involves students assessing the work of their classmates. This method encourages students to actively engage in the evaluation process, develop critical thinking skills, and provide constructive feedback. Peer assessment can be beneficial for performance tasks that involve group work or presentations.

By employing a combination of these assessment methods, educators can gain a comprehensive understanding of student performance and progress in relation to the performance tasks.

Rubric Development

Developing clear and comprehensive rubrics is crucial for effective evaluation of performance tasks. A rubric provides a set of criteria and performance levels that guide the assessment process and ensure consistency and fairness.

When developing a rubric for performance tasks, consider the following:

Clear Criteria : Clearly define the criteria for evaluation, ensuring they align with the learning objectives of the task. Break down the criteria into specific components or skills that will be assessed.

Performance Levels : Establish different performance levels that reflect varying degrees of mastery. These levels should be descriptive and provide a clear understanding of what constitutes each level of performance.

Descriptors : Provide descriptors or indicators for each performance level to guide evaluators in assigning scores. These descriptors should be specific and measurable, allowing for objective assessment.

Weighting : Assign appropriate weights to different criteria or components based on their relative importance. This helps ensure that each aspect of the performance task is given proper consideration during evaluation.

Effective rubrics not only provide guidance for educators during the assessment process but also offer students a clear understanding of expectations and areas for improvement. Well-designed rubrics help promote consistency in evaluation and ensure that all students are assessed fairly.

By implementing appropriate assessment methods and developing robust rubrics, educators can effectively evaluate student performance and provide meaningful feedback to support growth and learning.

Benefits of Performance Based Assessment

Performance based assessment offers numerous benefits in evaluating student learning and development. This section explores two key advantages: enhancing critical thinking and fostering real-world skills.

Enhancing Critical Thinking

Performance based assessment tasks encourage students to apply their knowledge and skills in real-life scenarios. By engaging in hands-on activities and solving complex problems, students develop and enhance their critical thinking skills.

Through performance tasks, students are required to analyze information, evaluate different perspectives, and make informed decisions. These tasks often involve open-ended questions or real-world scenarios, allowing students to think critically and creatively to arrive at solutions.

By challenging students to think beyond memorization and recall, performance based assessment promotes higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Students are encouraged to demonstrate their ability to reason, problem-solve, and justify their solutions, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Fostering Real-World Skills

One of the key advantages of performance based assessment is its ability to foster real-world skills. By engaging in tasks that mirror authentic situations and challenges, students develop skills that are relevant and applicable beyond the classroom.

Performance tasks often require students to collaborate, communicate effectively, and demonstrate their ability to work in teams. These skills are essential in today’s professional world, where teamwork and effective communication are highly valued.

Furthermore, performance based assessment encourages students to develop self-management skills, such as time management and organization. Students are given the opportunity to plan and execute tasks within a given timeframe, helping them develop skills that are crucial for success in various aspects of life.

By integrating real-world skills into the assessment process, performance based assessment prepares students for future challenges and empowers them with the skills necessary for success in their academic and professional journeys.

As educators and curriculum developers, it is important to recognize the benefits of performance based assessment in promoting critical thinking and real-world skill development. By incorporating performance tasks into the assessment framework, we can provide a more comprehensive evaluation of student learning and better prepare them for the challenges they will encounter beyond the classroom.

Perform Deep Market Research In Seconds

Automate your competitor analysis and get market insights in moments

Create Your Account To Continue!

Automate your competitor analysis and get deep market insights in moments, stay ahead of your competition. discover new ways to unlock 10x growth., just copy and paste any url to instantly access detailed industry insights, swot analysis, buyer personas, sales prospect profiles, growth opportunities, and more for any product or business..

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Knowledge Base

- Extended Learning

Performance Tasks

A performance task is any learning activity or assessment that asks students to perform to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding and proficiency. Performance tasks yield a tangible product and/or performance that serve as evidence of learning. Unlike a selected-response item (e.g., multiple-choice or matching) that asks students to select from given alternatives, a performance task presents a situation that calls for learners to apply their learning in context.

For more information of the design and use of performance tasks and performance task assessment, we’ve published a seven part series at https://blog.performancetask.com/ , authored by Jay McTighe.

Defined STEM Performance Task Project Outline

Set the stage.

- Introduction

- Career Video & Guiding Questions

Explore the Background ( GRASP)

- Goal – Each performance task begins with a Goal. The goal provides the student with the outcome of the learning experience and the contextual purpose of the experience and product creation.

- Role – The Role is meant to provide the student with the position or individual persona that they will become to accomplish the goal of the performance task. The majority of roles found within the tasks provide opportunities for students to complete real-world applications of standards-based content. The role may be for one student or in many instances can serve as a small group experience. Students may work together or assume a part of the role based upongroup dynamics. These roles will require student(s) to develop creative and innovative products demonstrating their understanding of the content through the application of the content and a variety of skills across disciplines.

- Audience – The performance tasks contain an Audience component. The audience is the individual(s) who are interested in the findings and products that have been created. These people will make a decision based upon the products and presentations created by the individual(s) assuming the role within the task. Click here for an article on the importance of audience within a performance task.

- Situation – The Situation provides the participants with a contextual background for the task. Students will learn about the real-world application for the task. Additionally, this section builds connections with other sections of Defined STEM. This is the place that may invite students to consider various video resources, simulations, language tasks, and associated websites when appropriate. This section of the performance task will help the students connect the authentic experience with content and concepts critical to understanding.

- having a student complete all products within a task;

- having students complete a number of products based upon content application and/or student interest;

- having a student complete certain products based upon the educator’s decision to maximize content, concept, and skill application;

- having student work as part of a cooperative group to complete a product or the products; and/or

- having students complete products based upon the strength of their multiple intelligences.

Do the Research

- Learning Objects

- Research Resources

- Constructed Response

Design Process & Product Creation

- The Design Process

- Submitting your work

Final Reflections

Was this article helpful, related articles.

- What We Offer

Connect With Us!

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Instructional Materials

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

- NCCSTS Case Collection

- Science and STEM Education Jobs

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Submit Book Proposal

- Web Seminars

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Leaders Institute • New Orleans 24

- National Conference • Philadelphia 25

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Submit a Proposal

- Conference Reviewers

- Past Conferences

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

How to Design a Performance Task

Share Start a Discussion

Follow a sequence of steps to develop an authentic performance task.

Performance tasks enable teachers to gather evidence not just about what a student knows, but also what he or she can do with that knowledge ( Darling-Hammond and Adamson 2010 ). Rather than asking students to recall facts, performance tasks measure whether a student can apply his or her knowledge to make sense of a new phenomenon or design a solution to a new problem. In this way, assessment becomes phenomenon-based and multidimensional as it assesses both scientific practices and content within a new context ( Holthuis et al. 2018 ).

As we move away from traditional testing, the purpose of assessment begins to shift. Instead of only measuring students’ performance, we also strive to create an opportunity for students to learn throughout the process. Not only are students learning more as they are being assessed, but the feedback you gain as a teacher is far richer than traditional assessment ( Wei, Schultz, and Pecheone 2012 ). This allows teachers to gather more information about what students do and do not know in order to better inform meaningful next steps in their teaching.

The design process

In the next sections, we describe a sequence of steps to design performance tasks for a science course using a sample middle school performance task, titled “Deer Population in Colorado.” Performance tasks are intended to assess individual student performance and can be administered at points that make sense for your instruction, either within or at the end of a unit. While we have defined a clear and meaningful sequence for this process, we want to emphasize that it is iterative in nature and often requires returning to earlier steps.

Step 1: Unpack the performance expectation

The first step of designing a performance task is to unpack the performance expectation (PE). “Unpacking” means digging into the Next Generation Science Standards ( NGSS ) documents to interpret what the PE really means; this ensures that your performance task assesses what you want it to assess.

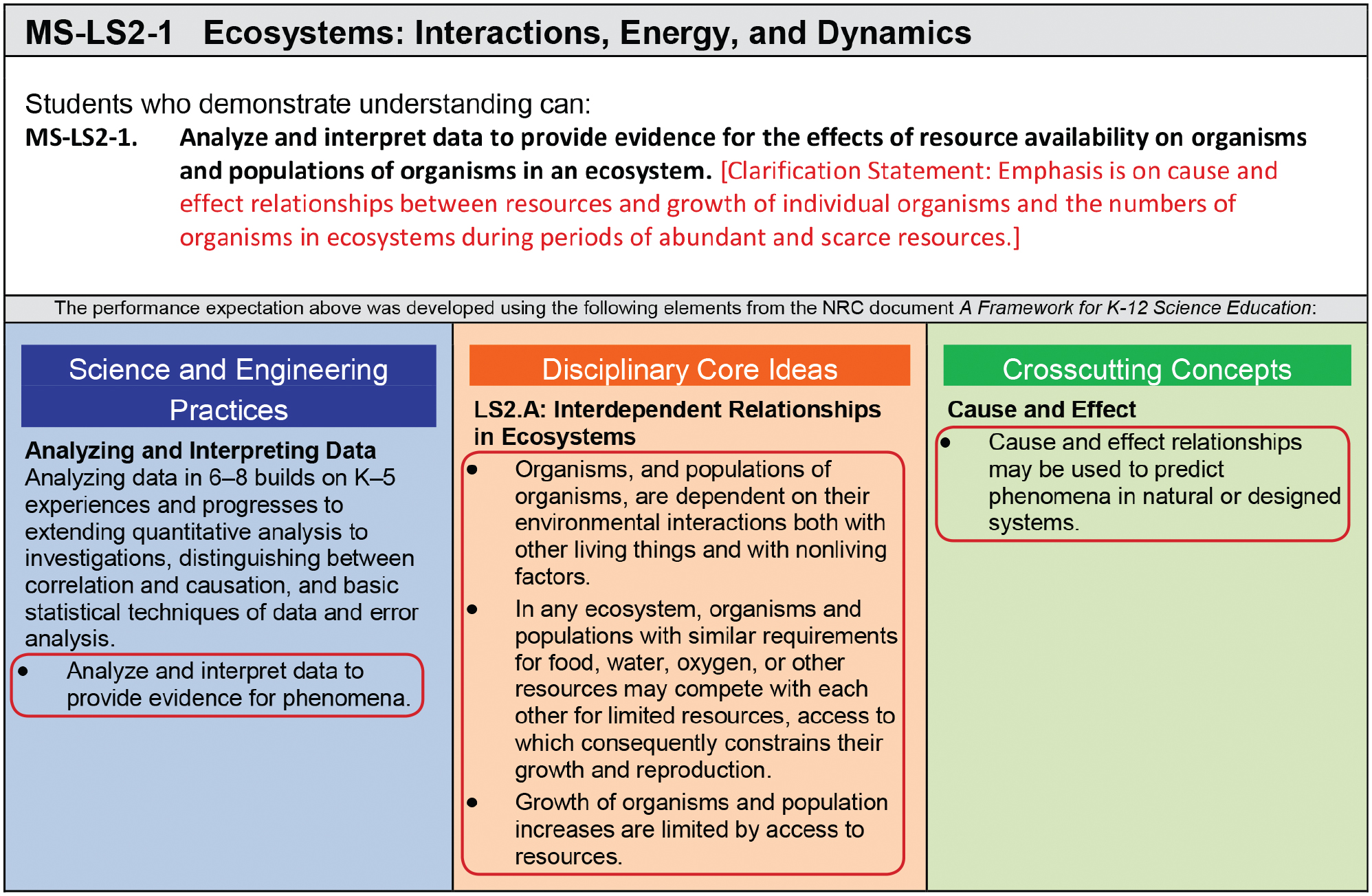

Imagine you are planning a unit on interactions within ecosystems and you would like to write a performance task that assesses students on the life science PE MS-LS2-1. Take a look at the NGSS document pictured ( Figure 1 ). The first step is to read the PE at the top, which also includes an important clarification statement that lends more detail. This is where many of us will stop; however, it is critical you continue to unpack the three dimensions listed below the PE.

Notice that we have circled the bullet points underneath the science and engineering practice (SEP), disciplinary core idea (DCI), and crosscutting concept (CCC). If you need more specific information for each dimension, you can click on the bulleted language, which will take you to the NGSS K–12 framework. By unpacking each dimension to this element level, we ensure that we are addressing these dimensions at the correct grade level for this PE. This ensures that we create a meaningful spiral for students throughout their K–12 education as they build complexity within these three dimensions over time. For example, with MS-LS2-1, we will not just ask students to identify cause-and-effect relationships, which would be at the 3–5 grade band level; we actually need to ask students to use cause-and-effect relationships to predict phenomena.

Keep in mind that this process also provides the flexibility to incorporate NGSS dimensions that are not specifically associated with a PE; we will show an example of this in step 3 of the process. By doing a thorough analysis and asking yourself these critical questions during the unpacking process, you will avoid major revisions later.

Step 2: Identify a rich and authentic phenomenon

The second step is to identify a rich and authentic phenomenon or an engineering problem that fits the performance expectation you are trying to assess. The NGSS community defines a phenomenon as an observable event that occurs in the universe; students then use their science knowledge to make sense of the selected phenomenon.

The phenomenon is the foundation of the task, and it is often where teachers experience the most frustration because it is challenging to find an actual phenomenon that truly fits the performance expectation. To begin the process of brainstorming a suitable phenomenon, we often start by looking at the elements of the DCI and connecting these concepts to anything we have seen or done in the past—for example, a cool video we saw, an interesting article we read, an intriguing podcast we listened to, or a great activity we have used in our classroom. These phenomena might be big and exciting—such as the Mount Tambora eruption that led to the “Year Without Summer”—or they could be smaller and more prevalent in everyday life—such as two pumpkins that grew to different sizes in the school garden.

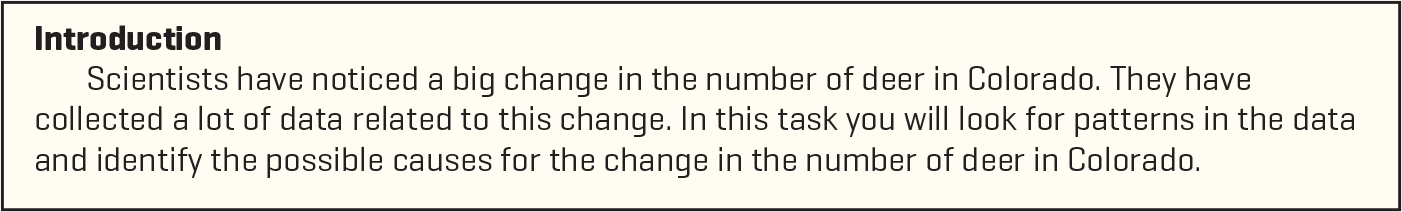

Examining the DCI of MS-LS2-1, we noticed themes of competition, limited access to resources, and population size. This triggered a memory of a research study about a huge decline in the deer population in Colorado. Upon further investigation, we found that this phenomenon aligned with all three dimensions of the PE; it had multiple sources for data analysis to assess the SEP, it showcased each element of the DCI, and it provided opportunities to use cause-and-effect relationships. See Figure 2 for an example of how we engage students with this phenomenon at the beginning of the Deer Population in Colorado performance task, using key words such as “data” and “cause” to introduce students to the NGSS dimensions they will be performing in this task. You will see this phenomenon weaved throughout the rest of the performance task.

In this process, we learned that a lot of interesting phenomena may seem initially applicable, but upon further investigation, they are not well-aligned with the PE and the corresponding dimensions we are trying to assess. For example, a common pitfall is selecting a phenomenon that initially seems to match the language of the PE but, in the end, does not apply to a majority of the elements of the DCI. The key to this step is to keep an open mind and remain willing to change the phenomenon if your first idea does not quite fit.

Step 3: Develop prompts

The next design step is to develop prompts—questions or instructions—that focus on the phenomenon and will elicit evidence of all three dimensions of the PE. In alignment with the SEP of MS-LS2-1, Analyzing and Interpreting Data, we first gathered data relevant to the phenomenon. The research study that inspired our choice in phenomena provided us with graphs that showed the change in the number of deer in Colorado, yearly rainfall, amounts of cheatgrass and sagebrush, population sizes of deer and elk, and causes of fawn deaths. While the data for this task came in a traditional format and was easily accessible from one source, data can come in many different forms (e.g., videos, images, data tables, graphs) and often this data collection process will require much more time and internet research. If data are not available in a form that is accessible to your group of students, you may also consider adapting existing data or using scientific concepts to manufacture your own mock data sets. In some cases, students can also generate data for themselves in the form of observations, measurements, and calculations as a result of carrying out an investigation or doing a simulation.

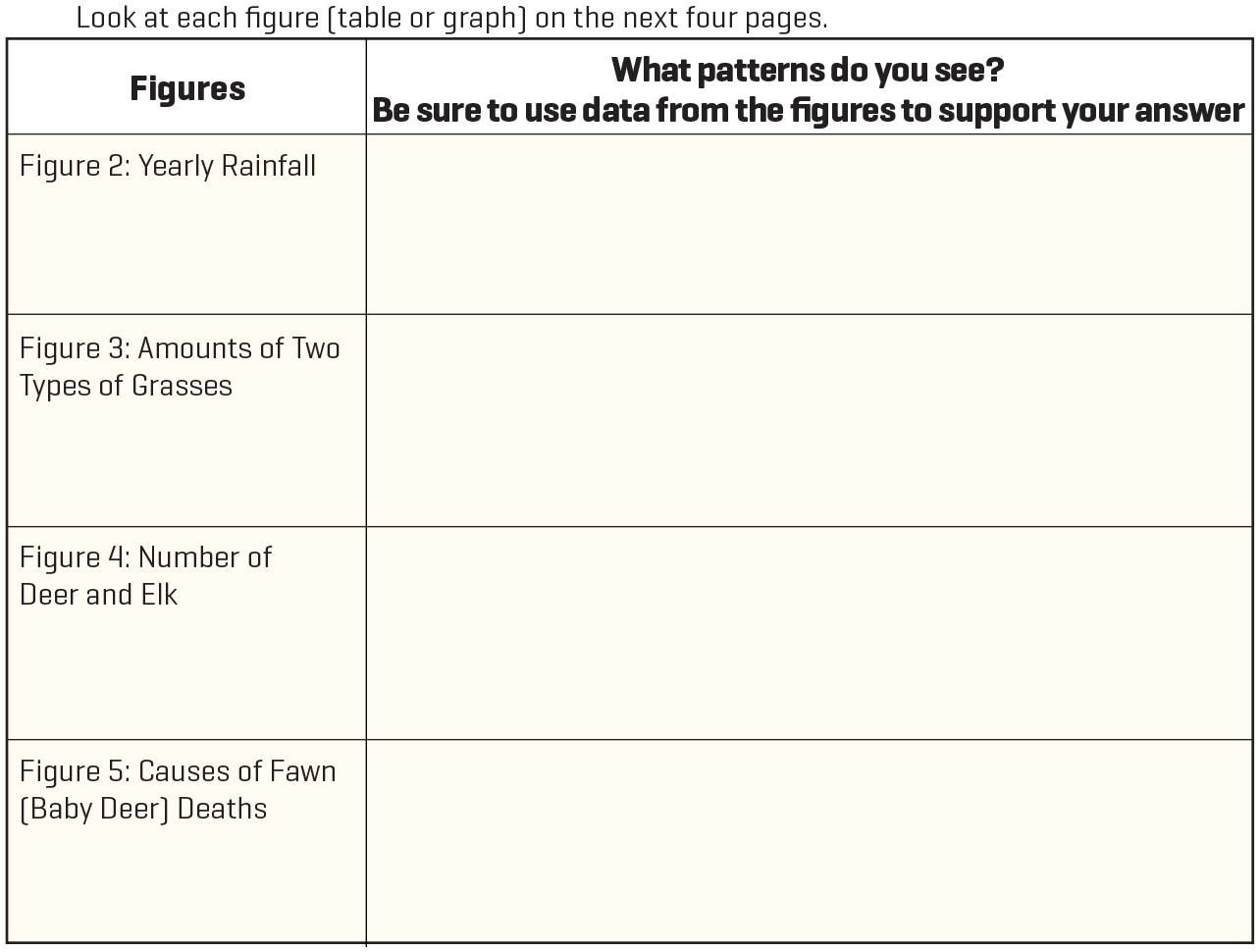

As we begin to write prompts, we must always remember that this type of assessment asks students to engage in a new and very complex thought process. In order to help students understand the phenomenon of the task and engage with difficult multidimensional questions, we also need to build in scaffolding questions that provide all students access to the assessment. If, for example, we ask students to analyze five different sources of data to use as evidence, we should provide them with a graphic organizer to help them organize their data analysis (see Figure 3 ). This is not only a tool to help each student organize and make sense of data as he or she independently completes this performance task, but it also offers another assessment opportunity for teachers to determine each student’s ability to read, analyze, and interpret data.

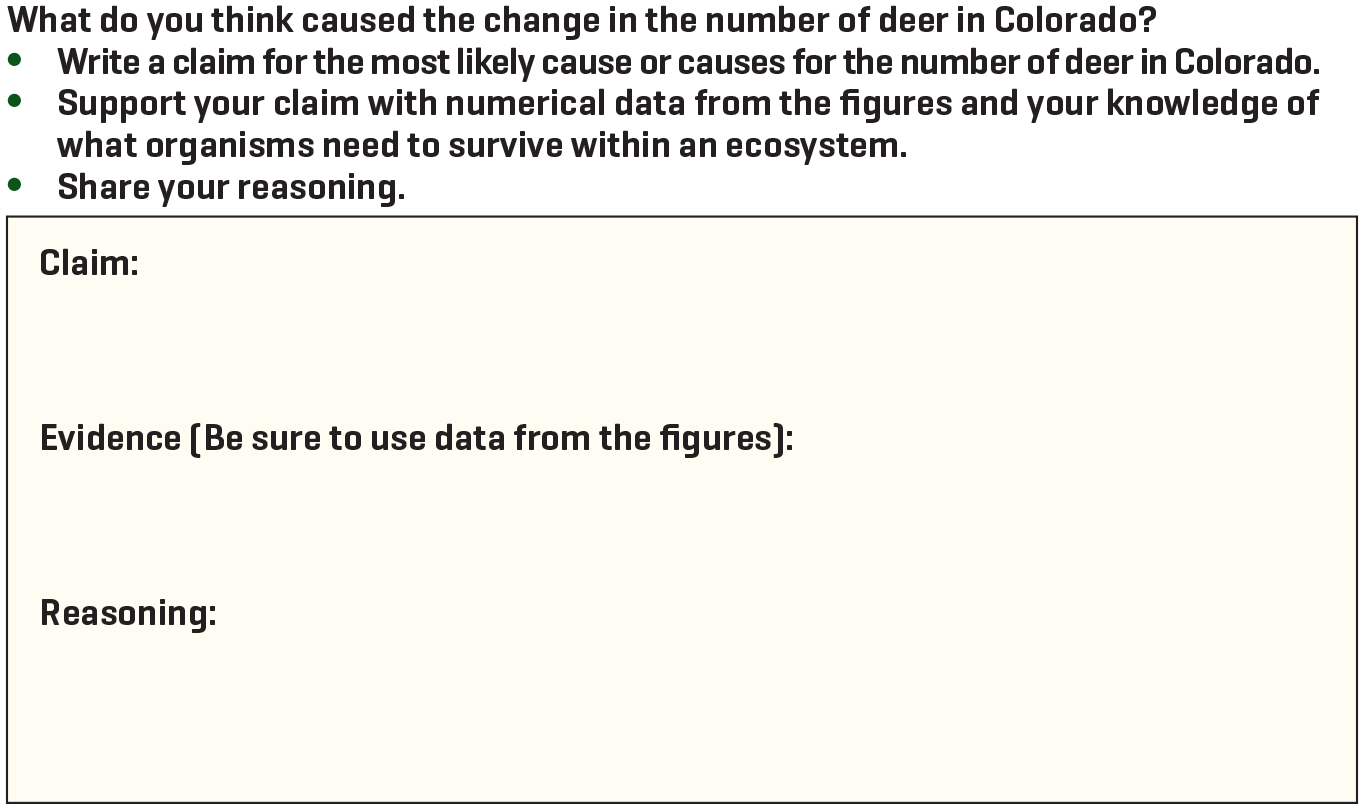

In line with this goal, we also want to make sure that our prompts are aligned with the NGSS vision of assessing the integration of relevant practices, knowledge, and concepts. For example, the above prompt was multidimensional because it asked students to show evidence of the SEP, Analyzing and Interpreting Data, and the DCI, LS2.A Interdependent Relationships in Ecosystems. As another example, take a look at the final prompt of this performance task ( Figure 4 ).

This prompt asks students to use their data analysis and their cause-and-effect relationships to make a claim about the phenomenon—the cause of the change in the deer population in Colorado. Notice we are not only assessing the relevant DCI LS2.A and CC of Cause and Effect for MS-LS2-1, but we are also choosing to assess an additional SEP element of Constructing Explanations: “Construct a scientific explanation based on valid and reliable evidence obtained from sources (including the students’ own experiments) and the assumption that theories and laws that describe the natural world operate today as they did in the past and will continue to do so in the future” ( Appendix F 2013 ).

To decide which SEP to assess, we needed to hone in on the distinction between Constructing Explanations and Engaging in Argument From Evidence—two SEPs that are so similar, they are often used interchangeably. For this particular prompt, students are required to construct a causal explanation of a phenomenon—which the NGSS defines as Constructing Explanations. This prompt focuses on assessing how students can use the provided sources of evidence as well as their understanding of appropriate scientific concepts in order to support one primary explanation for the number of deer in Colorado—lack of food.

This final prompt not only showcases this emphasis on the NGSS and multidimensionality, but it also reinforces that when we write performance tasks, it is essential that our prompts keep returning to the phenomenon—in this case, the change in the number of deer in Colorado. If this connection is not maintained, it is no longer a performance task, but rather a series of content-focused questions.

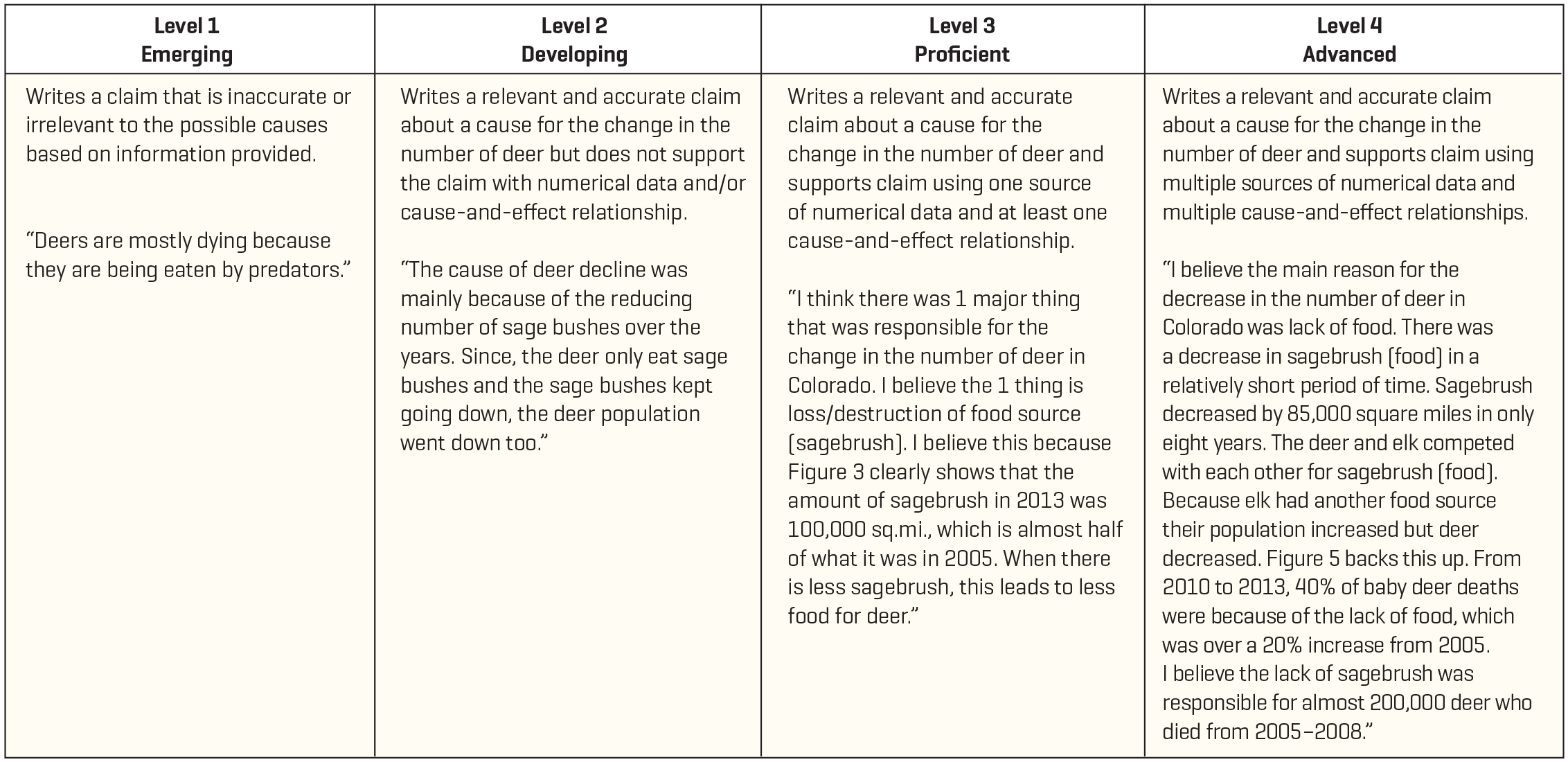

Step 4: Create scoring guides

Upon drafting a performance task, the next step is to create a scoring guide that includes rubrics that clearly assess the three dimensions of the PE. We will summarize the key components here.

When writing rubrics, we first need to identify the dimensions addressed in the prompt. Take the example of the final prompt of the Deer Population in Colorado task ( Figure 4 ). In this prompt, students are asked to show evidence of the SEP of Constructing Explanations, the DCI of Resource Availability and Populations, and the CC of Cause and Effect. Using the NGSS language of each of these dimensions, we write a specific statement, known as the rubric construct, that helps clarify what we are trying to assess in that prompt (see Figure 5 ).

Once we have an idea of what we are looking for, we can look at student work to identify a range of exemplars and use these to write descriptions for each level of performance. By including a student sample for each level of performance (see the last row of the rubric in Figure 5 ), we also provide teachers a range of authentic examples to know what student performance looks like for that prompt. Using this approach ensures that we create what is known as a multidimensional rubric, meaning it assesses the integration of multiple NGSS dimensions, rather than assessing only content. Keep in mind that writing rubrics is a very iterative process. At each step, you will want to stop and reflect on the alignment, and you will often return to previous steps to make adjustments.

Step 5: Pilot, score, and revise

Step 5 is often skipped due to time constraints, but it is the most essential. Piloting the task with students at the appropriate grade level and scoring student responses will help you identify prompts and rubrics that need to be revised.

In the case of the Deer Population in Colorado performance task, we learned that if we want students to show evidence of knowledge and practices, we must ask for it explicitly in the prompt. As we scored student samples for the final prompt, we noticed that students were able to demonstrate their ability to analyze data, but rarely included numerical data in their responses. To remedy this, we returned to the task itself and revised the prompts to specifically ask students to cite numerical data. We must remember that this kind of assessment is new for many students, so we need our expectations to be as clear and explicit as possible to give every student the best opportunity for success.

The most important step

While understanding the steps of the design process is essential, you will also find that support and collaboration are integral parts of the process. Remember that like any new process, designing performance tasks is going to be challenging. As you prepare to make the shift to NGSS -designed performance tasks, we highly recommend you put together a team of forward-thinking teachers like yourself, and seek out professional development to guide you through this new process.

For more information on the support SCALE Science provides around performance task design, please visit our website at scienceeducation.stanford.edu or contact us at [email protected] .

Darling-Hammond L. and Adamson F. 2010. Beyond basic skills: The role of performance assessment in achieving 21st century standards of learning. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Holthuis N., Deutscher R., Schultz S.E., and Jamshidi A. 2018. The new NGSS classroom: A curriculum framework for project-based science learning. American Educator 42 (2): 23–27.

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For states, by states. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. .

Wei R.C., Schultz S.E., and Pecheone R. 2012. Performance assessments for learning: The next generation of state assessments. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, British Columbia.

You may also like

Reports Article

What Is Performance Assessment?

- Share article

Project-based learning is nothing new. More than 100 years ago, progressive educator William Heard Kilpatrick published “The Project Method,” a monograph that took the first stab at defining alternatives to direct instruction. Predictably, the document sparked a squabble over definitions and methods—between Kilpatrick and his friend and colleague John Dewey.

Not much has changed. Today, despite major advances in ways to measure learning, we still don’t have common definitions for project-based learning or performance assessment.

Sometimes, for example, performance assessment is framed as the opposite of the dreaded year-end, state-required multiple-choice tests used to report on schools’ progress. But in fact, many performance assessments are standardized and can—and do—produce valid and reliable results.

Experts also emphasize the “authentic” nature of performance assessment and project-based learning, although “authentic” doesn’t always mean lifelike: A good performance assessment can use simulations, as long as they are faithful to real-world situations. (An example: In science class, technology can simulate plant growth or land erosion, processes that take too long for a hands-on experiment.)

In the absence of agreed-upon definitions for this evolving field, Education Week reporters developed a glossary based on interviews with teachers, assessment experts, and policy analysts. They’ve organized the terms here generally from less specific to more specific. These terms aren’t mutually exclusive. (A performance assessment, for instance, may be one element of a competency-based education program.)

Proficiency-based or competency-based learning: These terms are interchangeable. They refer to the practice of allowing students to progress in their learning as they master a set of standards or competencies. Students can advance at different rates. Typically, there is an attempt to build students’ ownership and understanding of their learning goals and often a focus on “personalizing” students’ learning based on their needs and interests.

Project-based learning: Students learn through an extended project, which may have a number of checkpoints or assessments along the way. Key features are inquiry, exploration, the extended duration of the project, and iteration (requiring students to revise and reflect, for example). A subset of project-based learning is problem-based learning, which focuses on a specific challenge for which students must find a solution.

Standards-based grading: This refers to the practice of giving students nuanced and detailed descriptions of their performance against specific criteria or standards, not on a bell curve. It can stand alone or exist alongside traditional letter grading.

Performance assessment: This assessment measures how well students apply their knowledge, skills, and abilities to authentic problems. The key feature is that it requires the student to produce something, such as a report, experiment, or performance, which is scored against specific criteria.

Portfolio: This assessment consists of a body of student work collected over an extended period, from a few weeks to a year or more. This work can be produced in response to a test prompt or assignment but is often simply drawn from everyday classroom tasks. Frequently, portfolios also contain an element of student reflection.

Exhibition: A type of performance assessment that requires a public presentation, as in the sciences or performing arts. Other fields can also require an exhibition component. Students might be required, for instance, to justify their position in an oral presentation or debate.

Performance task: A piece of work students are asked to do to show how well they apply their knowledge, skills, or abilities—from writing an essay to diagnosing and fixing a broken circuit. A performance assessment typically consists of several performance tasks. Performance tasks also may be included in traditional multiple-choice tests.

With thanks to: Paul Leather, director for state and local partnerships at the Center for Innovation in Education; Mark Barnes, founder of Times 10 Publications; Peter Ross, principal at Education First; Scott Marion, executive director at the Center for Assessment; Sean P. “Jack” Buckley, president, Imbellus; Starr Sackstein, an educator and opinion blogger at edweek.org; and Steve Ferrara, senior adviser at Measured Progress.

Have we missed any terms that confuse you? Why not write and tell us?

A version of this article appeared in the February 06, 2019 edition of Education Week as Performance Assessment: A Guide to the Vocabulary

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- What Is a Performance Task?

A performance task is any learning activity or assessment that asks students to perform to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding and proficiency. Performance tasks yield a tangible product and/or performance that serve as evidence of learning. Unlike a selected- response item (e.g., multiple-choice or matching) that asks students to select from given alternatives, a performance task presents a situation that calls for learners to apply their learning in context.

Performance tasks are routinely used in certain disciplines, such as visual and performing arts, physical education, and career-technology where performance is the natural focus of instruction. However, such tasks can (and should) be used in every subject area and at all grade levels.

Characteristics of Performance Tasks

While any performance by a learner might be considered a performance task (e.g., tying a shoe or drawing a picture), it is useful to distinguish between the application of specific and discrete skills (e.g., dribbling a basketball) from genuine performance in context (e.g., playing the game of basketball in which dribbling is one of many applied skills). Thus, when I use the term performance tasks, I am referring to more complex and authentic performances.

Here are seven general characteristics of performance tasks :

1. Performance tasks call for the application of knowledge and skills, not just recall or recognition.

In other words, the learner must actually use their learning to perform. These tasks typically yield a tangible product (e.g., graphic display, blog post) or performance (e.g., oral presentation, debate) that serve as evidence of their understanding and proficiency.

2. Performance tasks are open-ended and typically do not yield a single, correct answer.

Unlike selected- or brief constructed- response items that seek a “right” answer, performance tasks are open-ended. Thus, there can be different responses to the task that still meet success criteria. These tasks are also open in terms of process; i.e., there is typically not a single way of accomplishing the task.

3. Performance tasks establish novel and authentic contexts for performance.

These tasks present realistic conditions and constraints for students to navigate. For example, a mathematics task would present students with a never-before-seen problem that cannot be solved by simply “plugging in” numbers into a memorized algorithm. In an authentic task, students need to consider goals, audience, obstacles, and options to achieve a successful product or performance. Authentic tasks have a side benefit – they convey purpose and relevance to students, helping learners see a reason for putting forth effort in preparing for them.

4. Performance tasks provide evidence of understanding via transfer.

Understanding is revealed when students can transfer their learning to new and “messy” situations. Note that not all performances require transfer. For example, playing a musical instrument by following the notes or conducting a step-by-step science lab require minimal transfer. In contrast, rich performance tasks are open-ended and call “higher-order thinking” and the thoughtful application of knowledge and skills in context, rather than a scripted or formulaic performance.

5. Performance tasks are multi-faceted .

Unlike traditional test “items” that typically assess a single skill or fact, performance tasks are more complex. They involve multiple steps and thus can be used to assess several standards or outcomes.

6. Performance tasks can integrate two or more subjects as well as 21st century skills.

In the wider world beyond the school, most issues and problems do not present themselves neatly within subject area “silos.” While performance tasks can certainly be content-specific (e.g., mathematics, science, social studies), they also provide a vehicle for integrating two or more subjects and/or weaving in 21 st century skills and Habits of Mind. One natural way of integrating subjects is to include a reading, research, and/or communication component (e.g., writing, graphics, oral or technology presentation) to tasks in content areas like social studies, science, health, business, health/physical education. Such tasks encourage students to see meaningful learning as integrated, rather than something that occurs in isolated subjects and segments.

7. Performances on open-ended tasks are evaluated with established criteria and rubrics.

Since these tasks do not yield a single answer, student products and performances should be judged against appropriate criteria aligned to the goals being assessed. Clearly defined and aligned criteria enable defensible, judgment-based evaluation. More detailed scoring rubrics, based on criteria, are used to profile varying levels of understanding and proficiency.

Click here to download this document in PDF .

Click here to search Unit Plans by Big Idea, Competency, Curricular Competency & Content, Subject or Grade

Resources to assist with planning

- How to use the Unit Planner Guide

- UBD Overview

- Website to Classroom Powerpoint

- Sample Year Plan (Grade 4-5)

Stage One - Desired Results

- Big Ideas by Grade

- Combined Grades Big Ideas

- Concept-based Teaching Brief

- Concepts List by Subject

- Transfer Goals Handout

- Essential Questions Explained

- First People's Principles of Learning

Stage Two - Planning for Assessment

- How to do Stage 2 Assessment

- GRASPS Instructions

- GRASPS How Can Educators Design Authentic Performance Tasks

- GRASPS Performance Task Scenario

- AMT Learning Goals and Teaching Roles

- AMT Explained

- AMT Worksheet

Innovative Education in VT

P is for performance tasks, using performance tasks as a way to measure student knowledge.

It’s the “do” in the KUD (know, understand, and do) that so often gets left behind, but is so important in the world of deep learning.

What defines a performance task?

Chun describes the elements of a performance task to include:

- real-world scenarios;

- authentic, complex processes;

- higher order thinking;

- authentic performances; and

- transparent evaluation criteria.

Model Example:

One way to get a grasp on what performance tasks look like is to check out this excellent resource from Steve Bibla and the Toronto District School Board detailing how they created rich performance tasks to teach Ecological Literacy .

Use these resources to start building your own:

Jay McTighe’s article How Can Educators Design Authentic Performance Tasks? provides scaffolded, step-by-step supports in building one from scratch.

But, like all efficient and busy educators, we also know we could save time by searching for existing tasks and adapting them to our specific context/needs.

Enter Ted Curran and his fabulous recycling of existing performance tasks in his post Action-Oriented eLearning with the Humble Webquest. He advocates for revamping the visually dated, but rich in authentic and relevant learning Webquests provide — learning that requires higher order thinking skills and application- – by updating with current technology old Webquests.

Finally, you might find it worth your time to explore the DefinedStem website. While the resources are not free, after seeing the rich resources and performance tasks available, you might find the extra time to write a grant or convince your district to fund access. Check out an example performance task Baseball Bat Analyst (Grade 7) and read a review of the resource here .

But why performance tasks right now?

A sample performance task for middle school

It’s important for young adolescents to have tasks that demonstrate proficiency while simultaneously allowing them:

- the freedom to explore personally meaningful topics

- space to explore and reflect on who they are and who they’re becoming

- activities that have real-world impact and relevance

Following along those precepts, let’s revisit Wiggins & McTighe’s GRASPS framework for an example activity. Goal, role, audience, situation, product/performance/purpose, standards then might look like:

How could you adapt this performance task activity for your next curriculum unit?

Need to catch up on your edtech ABCs? Check out the full series here .

10 thoughts on “P is for Performance Tasks”

Using performance tasks to measure student knowledge #vted http://t.co/P7xkUnyGux http://t.co/9drAxr5Qpp

Thanks for your kind mention of my post on performance assessment, @hennesss! Great article for #k12 lesson design.

http://t.co/hAity9f9Mq

Looking for some frameworks to measure student knowledge? Check out “P is for Performance Tasks” http://t.co/5zBrf933yW

P is for Performance Tasks http://t.co/sAgvhH7I25 via @innovativeEd

P is for Performance Tasks http://t.co/yxhZefhi8U

ABCs of Edtech: P is for Performance Tasks http://t.co/tps7dhruUL

For the evening crowd: using performance tasks to measure student learning http://t.co/P7xkUnh5CZ

RT @innovativeEd: Using performance tasks to measure student knowledge #vted http://t.co/P7xkUnyGux http://t.co/9drAxr5Qpp

Great suggestions for rethinking authentic learning. P is for Performance Tasks http://t.co/zjbyVh2Ugt #vsla #vted #tlchat

The application of Performance Tasks into measuring student knowledge is indeed an innovative stance. This article is very insightful as it demonstrates the minutes of the elements of a performance task. Thanks for sharing the post.

What do you think? Cancel reply

A blog exploring innovative, personalized, student-centered school change, discover more from innovative education in vt.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Performance Tasks or Projects? Complementary Approaches for Student Engagement

Performance Task—or Project?

Eight dimensions for profiling “performance tasks” and “projects”, qualities of effective performance tasks and projects, the stepping stones students need.

- Students play the role of community garden planners in a city. They calculate lot and plot sizes and amounts of soil needed, create a site map, and consider water and fertilizer needs for various plants that could be grown. They create a flyer and a presentation that would be appropriate for an audience of community members. (Source: Defined Learning)

- Students read three fairy tales that all have the same general pattern. They are asked to write a story that includes all the characteristics, and general pattern, of a fairy tale. They then read their story to a kindergarten reading buddy and teach him/her about the characteristics and general pattern of a fairy tale. (Source: Marzano, Pickering, & McTighe, 1993)

- Students act as a consumer advocate researchers who have been asked to evaluate the claim by the Pooper Scooper Kitty Litter Company that their litter is 40 percent more absorbent than other brands. Students develop a plan for conducting the investigation that must be specific enough so that the lab investigators could follow it to evaluate the claim. (Source: McTighe, 2021)

2-4 class periods 5-10 class periods More than 2 weeks

Inauthentic/decontextualized Simulates an authentic context Totally authentic

Single discipline Integrates two subject Multi-disciplinary

Teacher directed Teachers with some student self-direction Student directed

No support Some support Extensive support

Task topic, problem, issue Product(s)/performance(s) Audience(s) How and with whom they work

Individually Some group & some individual work All work done collaboratively

Classroom teacher only Team of teachers External evaluators/experts

Figure 1 – Performance Task Criteria

1. The task aligns with targeted standard(s)/outcome(s) and one or more of the 4 C’s – critical thinking, creativity, communication, collaboration.

2. The task calls for understanding and transfer, not simply recall or a formulaic response.

3. The task requires extended thinking and habits of mind—not just an answer.

4. The task is set in an “authentic” context; i.e., includes a realistic purpose, a target audience, and genuine constraints.

5. The task includes criteria/rubric(s) targeting distinct traits of understanding and transfer; i.e., criteria do not simply focus on surface features of a product or performance.

6. The task directions for students are clear.

7. The task will be feasible to implement.

8. The task allows students to demonstrate their understanding/ proficiency with some appropriate choice/variety (e.g., of products or performances).

9. The task effectively integrates two or more subject areas.

10. The task incorporates appropriate use of technology.

Figure 2 – High-Quality PBL Criteria

1. Intellectual Challenge and Accomplishment: Students learn deeply, think critically, and strive for excellence.

2. Authenticity: Students work on projects that are meaningful and relevant to their culture, their lives, and their future.

3. Public Product: Students’ work is publicly displayed, discussed, and critiqued.

4. Collaboration: Students collaborate with other students in person or online and/or receive guidance from adult mentors and experts.

5. Project Management: Students use a project management process that enables them to proceed effectively from project initiation to completion.

6. Reflection: Students reflect on their work and their learning throughout the project.

- The learning goals—content standards in academic disciplines, competencies identified in a Profile of a Graduate, habits of mind found in a mission statement.

- Age and experience of the learners.

- Organizational factors—available time, schedules for both students and teachers, availability of resources.

- The experience levels of teachers in facilitating tasks and PBL.

Buck Institute for Education. (2017). Framework for high-quality project-based learning .

Defined Learning (2018). Performance task: Community garden coordinator.

Educurious. (2021). Project America: Untold stories of the revolution . Course.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & McTighe, J. (1993). Assessing student outcomes: Performance assessment using the dimensions of learning model. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. p. 56

McTighe, J., Doubet, K. & Carbaugh, E. (2020). Designing Authentic Performance Tasks and Projects: Tools for Meaningful Learning and Assessment. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. p. 12.

McTighe, J. (2021). Developing authentic performance tasks . Performance task examples provided in a workshop handout.

Jay McTighe has a varied career in education. He served as director of the Maryland Assessment Consortium, a collaboration of school districts working to develop and share formative performance assessments and helped lead standards-based reforms at the Maryland State Department of Education. Prior to that, he helped lead Maryland’s standards-based reforms, including the development of performance-based statewide assessments.

Well known for his work with thinking skills, McTighe has coordinated statewide efforts to develop instructional strategies, curriculum models, and assessment procedures for improving the quality of student thinking. He has extensive experience as a classroom teacher, resource specialist, program coordinator, and in professional development, as a regular speaker at national, state, and district conferences and workshops.

McTighe is an accomplished author, having coauthored more than a dozen books, including the award-winning and best-selling Understanding by Design® series with Grant Wiggins. He has written more than 50 articles and book chapters and has been published in leading journals, including Educational Leadership (ASCD) and Education Week .

UNDERSTANDING BY DESIGN® and UbD® are registered trademarks of Backward Design, LLC used under license.

John Larmer is an author and internationally-recognized expert in project-based learning (PBL). A speaker, curriculum developer, professional learning designer, innovative educator, writer and editor, he is a long-time advocate of progressive school reform and is dedicated to making learning more meaningful for all students. Larmer was a key builder of PBLWorks and the Buck Institute for Education, serving as its editor in chief, director of publications, and director of product development. He is the co-author of the ASCD books Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning and Project Based Teaching. He is currently Senior Project Based Learning Advisor at Defined Learning.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., related articles.

Adapting Discussions to Unpredictable Attendance

Been to a Good Lecture?

Creating Autonomy Within Fidelity

Taking Risks with Rough Draft Teaching

Reimagining Mathematics to Save the World

Authentic Ways to Develop Performance-Based Activities

Students acquire knowledge, practice skills, and develop work habits

- Assessments & Tests

- Becoming A Teacher

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Performance-based learning is when students participate in performing tasks or activities that are meaningful and engaging. The purpose of this kind of learning is to help students acquire and apply knowledge, practice skills, and develop independent and collaborative work habits. The culminating activity or product for performance-based learning is one that lets a student demonstrate evidence of understanding through a transfer of skills.

A performance-based assessment is open-ended and without a single, correct answer, and it should demonstrate authentic learning , such as the creation of a newspaper or class debate. The benefit of performance-based assessments is that students who are more actively involved in the learning process absorb and understand the material at a much deeper level. Other characteristics of performance-based assessments are that they are complex and time-bound.

Also, there are learning standards in each discipline that set academic expectations and define what is proficient in meeting that standard. Performance-based activities can integrate two or more subjects and should also meet 21st Century expectations whenever possible:

- Creativity and Innovation

- Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

- Communication and Collaboration

There are also Information Literacy standards and Media Literacy standards that require performance-based learning.

Clear Expectations

Performance-based activities can be challenging for students to complete. They need to understand from the beginning exactly what is being asked of them and how they will be assessed.

Examples and models may help, but it is more important to provide detailed criteria that will be used to assess the performance-based assessment. All criteria should be addressed in a scoring rubric.

Observations are an important component and can be used to provide students with feedback to improve performance. Teachers and students can both use observations. There may be peer to peer student feedback. There could be a checklist or a tally to record student achievement.

The goal of performance-based learning should be to enhance what the students have learned, not just have them recall facts. The following six types of activities provide good starting points for assessments in performance-based learning.

Presentations

One easy way to have students complete a performance-based activity is to have them do a presentation or report of some kind. This activity could be done by students, which takes time, or in collaborative groups.

The basis for the presentation may be one of the following:

- Providing information

- Teaching a skill

- Reporting progress

- Persuading others

Students may choose to add in visual aids or a PowerPoint presentation or Google Slides to help illustrate elements in their speech. Presentations work well across the curriculum as long as there is a clear set of expectations for students to work with from the beginning.

Student portfolios can include items that students have created and collected over a period. Art portfolios are for students who want to apply to art programs in college.

Another example is when students create a portfolio of their written work that shows how they have progressed from the beginning to the end of class. The writing in a portfolio can be from any discipline or a combination of disciplines.

Some teachers have students select those items they feel represents their best work to be included in a portfolio. The benefit of an activity like this is that it is something that grows over time and is therefore not just completed and forgotten. A portfolio can provide students with a lasting selection of artifacts that they can use later in their academic career.

Reflections may be included in student portfolios in which students may make a note of their growth based on the materials in the portfolio.

Performances

Dramatic performances are one kind of collaborative activities that can be used as a performance-based assessment. Students can create, perform, and/or provide a critical response. Examples include dance, recital, dramatic enactment. There may be prose or poetry interpretation.

This form of performance-based assessment can take time, so there must be a clear pacing guide.

Students must be provided time to address the demands of the activity; resources must be readily available and meet all safety standards. Students should have opportunities to draft stage work and practice.

Developing the criteria and the rubric and sharing these with students before evaluating a dramatic performance is critical.

Projects are commonly used by teachers as performance-based activities. They can include everything from research papers to artistic representations of information learned. Projects may require students to apply their knowledge and skills while completing the assigned task. They can be aligned with the higher levels of creativity, analysis, and synthesis.

Students might be asked to complete reports, diagrams, and maps. Teachers can also choose to have students work individually or in groups.

Journals may be part of a performance-based assessment. Journals can be used to record student reflections. Teachers may require students to complete journal entries. Some teachers may use journals as a way to record participation.

Exhibits and Fairs

Teachers can expand the idea of performance-based activities by creating exhibits or fairs for students to display their work. Examples include things like history fairs to art exhibitions. Students work on a product or item that will be exhibited publicly.

Exhibitions show in-depth learning and may include feedback from viewers.

In some cases, students might be required to explain or defend their work to those attending the exhibition.

Some fairs like science fairs could include the possibility of prizes and awards.

A debate in the classroom is one form of performance-based learning that teaches students about varied viewpoints and opinions. Skills associated with debate include research, media and argument literacy, reading comprehension, evidence evaluation, public speaking, and civic skills.

There are many different formats for debate. One is the fishbowl debate in which a handful of students form a half circle facing the other students and debate a topic. The rest of the classmates may pose questions to the panel.

Another form is a mock trial where teams representing the prosecution and defense take on the roles of attorneys and witnesses. A judge, or judging panel, oversees the courtroom presentation.

Middle school and high schools can use debates in the classroom, with increased levels of sophistication by grade level.

- Christmas and Winter Holiday Vocabulary 100 Word List

- Thematic Unit Definition and How to Create One

- Elementary School Summer Session Activities by Subject

- Emergency Lesson Plan Ideas

- Bingo Across the Curriculum

- Earth Day Activities and Ideas

- School Testing Assesses Knowledge Gains and Gaps

- May Day Activities for Grades 1-3

- How to Construct a Bloom's Taxonomy Assessment

- Using ABC Countdowns to Summer in School

- Christmas Acrostic Poem Lesson Plan

- How to Celebrate Johnny Appleseed

- Celebrate Dr. Seuss's Birthday with Your Classroom

- What Does a Great Lesson Look Like on the Outside?

- Fun Field Day Activities for Elementary Students

EL Education Curriculum

You are here.

- ELA G4:M1:U3:L11

Performance Task: Presentations

In this lesson, daily learning targets, ongoing assessment.

- Technology and Multimedia

Supporting English Language Learners

Universal design for learning, closing & assessments, you are here:.

- ELA Grade 4

- ELA G4:M1:U3

Like what you see?

Order printed materials, teacher guides and more.

How to order

Help us improve!

Tell us how the curriculum is working in your classroom and send us corrections or suggestions for improving it.

Leave feedback

These are the CCS Standards addressed in this lesson:

- SL.4.4: Report on a topic or text, tell a story, or recount an experience in an organized manner, using appropriate facts and relevant, descriptive details to support main ideas or themes; speak clearly at an understandable pace.

- SL.4.5: Add audio recordings and visual displays to presentations when appropriate to enhance the development of main ideas or themes.

- I can clearly and confidently present my poem and explain what inspired me to write it. ( SL.4.4, SL.4.5 )

- Recorded poetry presentation ( SL.4.4, SL.4.5 )

| Agenda | Teaching Notes |

|---|---|

| A. Reviewing Learning Target (10 minutes)

A. Poetry Presentations (45 minutes)

A. Reflecting on Learning (5 minutes)

A. N/A | ). This may take longer than the allocated 45 minutes, depending on the number of students in the class.

|

- Necessary technology for student presentations (see Technology and Multimedia).

- An order or system for presentations, depending on how students will present.

- Post: Learning targets and Effective Presentations anchor chart.

Tech and Multimedia