Parasite Movie Analysis, Synopsis and Ending Explained (Video Essay)

P arasite director Bong Joon-ho’s insightful and engaging comedy/thriller became one of the most talked-about films of the year and set a new precedent for the mark a South Korean movie can leave on United States’ movie-going audiences. The film is packed with social commentary, thrilling moments, and plenty of meaty writing worthy of a full ‘ Parasite movie analysis’.

Watch: Parasite Explained in 15 Story Beats

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

Parasite Movie Synopsis - what is Parasite about

Parasite synopsis: pulling off the con.

What is Parasite about? The first half of Parasite plays out largely as a comedy-drama with a compelling narrative and thought-provoking themes. We’ll be taking a look at all of the ingredients to made Parasite one of the best films of 2019 and one of the best South Korean films ever made , but first, let’s get started with a Parasite synopsis.

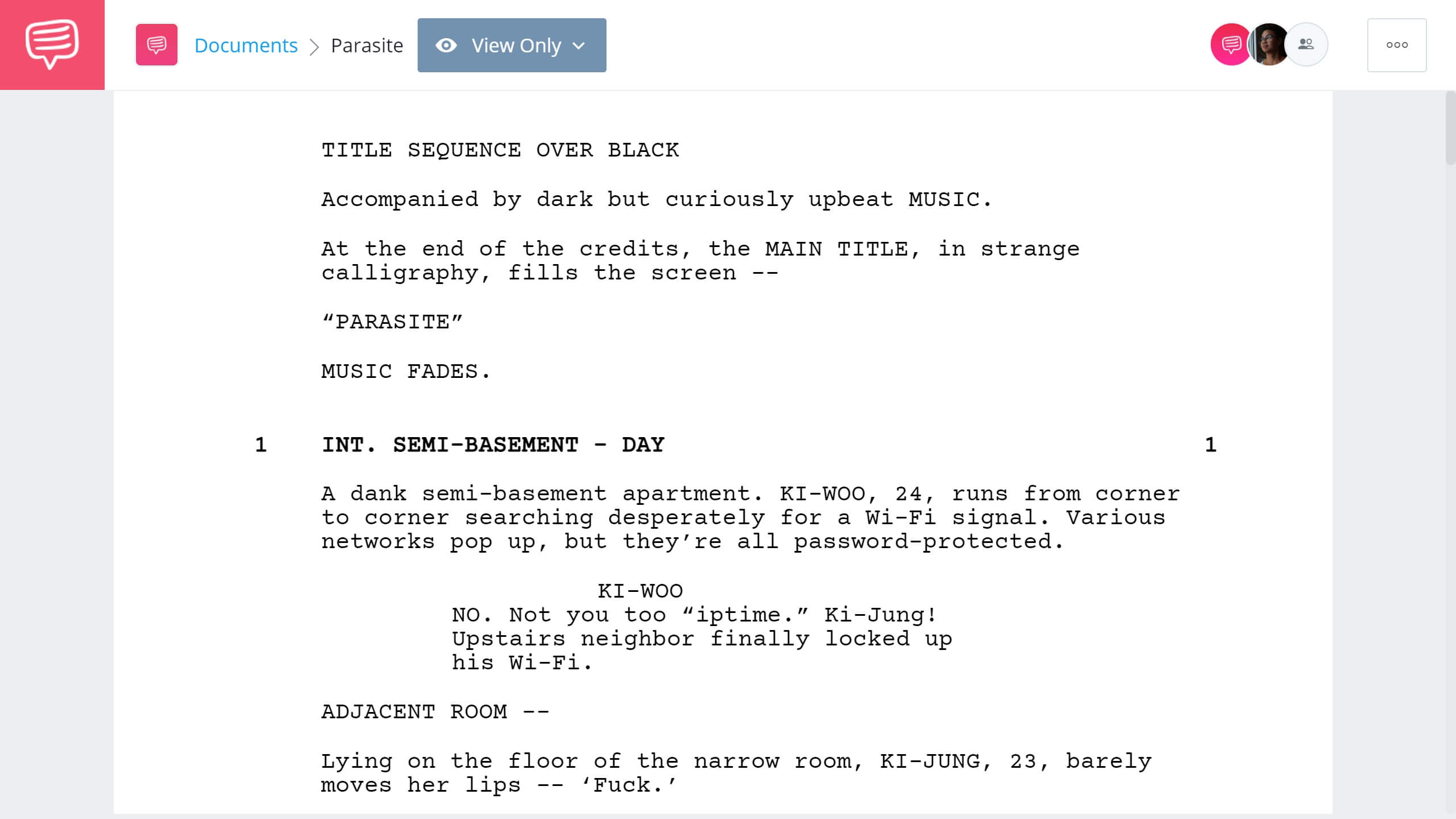

The Kim family lives in a semi-basement and struggles to keep food on the table. They take on odd jobs for cash like folding pizza boxes, and they rely on unprotected wi-fi networks and street-cleaning pesticides to keep their home insect-free.

Parasite movie synopsis • street-cleaning pesticides

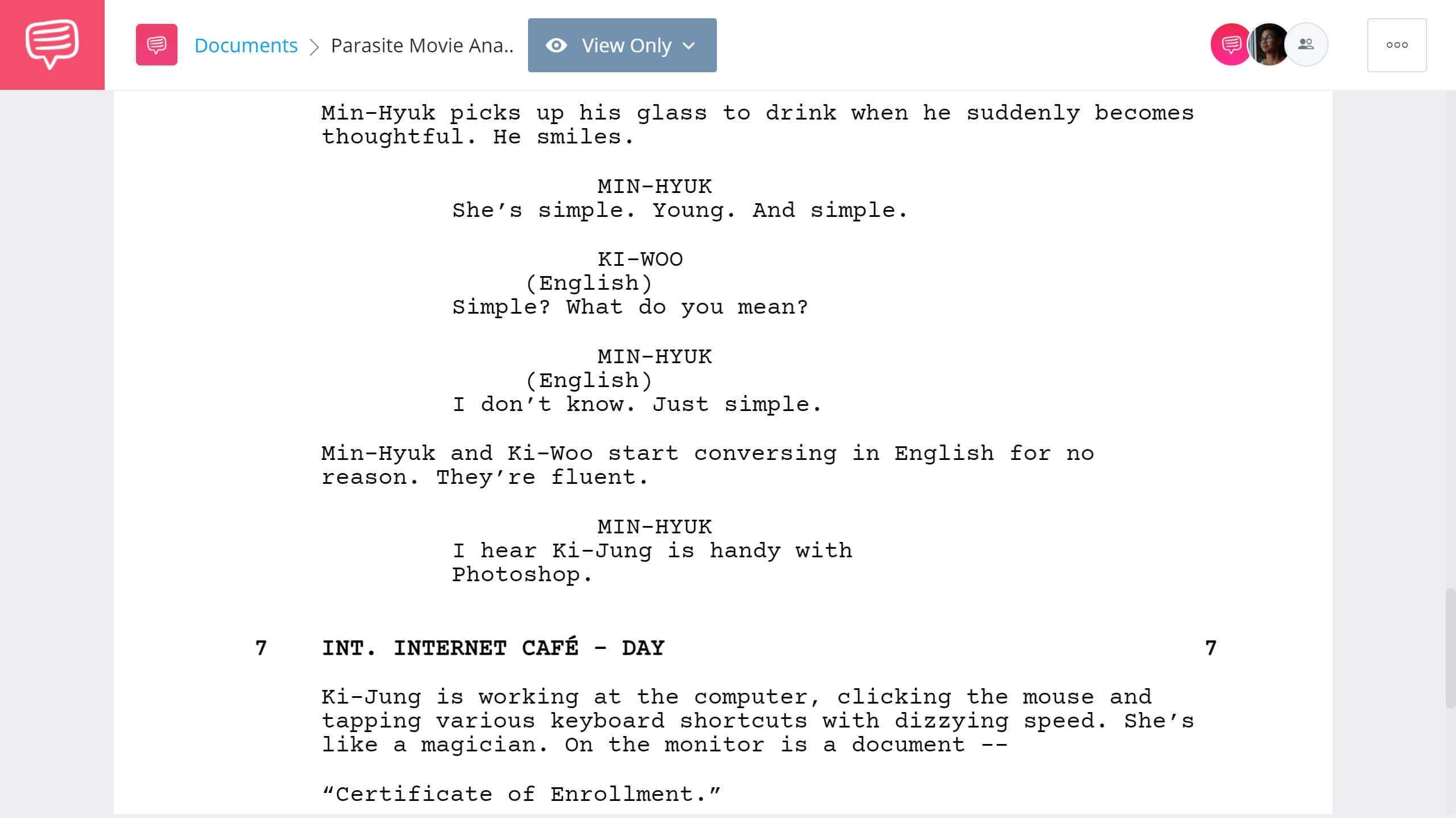

Ki-woo, the son, is gifted a scholar’s stone or suseok by a friend and given a recommendation for a tutoring job with a wealthy family. Ki-woo and his sister Ki-jung forge credentials for the job, and thus begins the long-con that sees each member of the Kim family infiltrating the upper-class Park family one-by-one. There are plenty of examples of subtle foreshadowing all throughout this opening act that circle back around by the end of the film.

Parasite meaning conveyed in screenplay excerpt

If you are interested in reading through the rest of the script, you can find it below. And, if you would like a deep-dive into the inner workings of the screenplay, be sure to read our Parasite script teardown.

Full Script PDF Download

Ki-jung begins working for the parks under the guise of an art-therapy teacher. Ki-taek, the father, begins working as the Park family chauffeur after the Kims have removed their previous chauffeur from his position, and similarly Chung-sook, the mother, replaces Moon-gwang, the housekeeper who has served the home longer than the Park’s have even lived there. Chung-sook is framed as deceiving the family by hiding a dangerous illness. The real deception is carried out by the Kims, and it works flawlessly.

Ki-taek with the scholar’s stone

The contrast in appearance between the Kims’ semi-basement home and the lavish home of the Park family is impossible to miss. The brilliant set dressing of Parasite combined with the striking architectural-design choices perfectly reinforce the themes of the film, but more on the themes after we finish our Parasite summary.

For some Parasite movie analysis straight from the auteur himself, check out this scene breakdown from Bong Joon-ho . Alongside actor Choi Woo-sik, he explains the significance of production design elements from the beginning of the film, such as the cultural context of scholar’s stones in South Korea and the idea of distant hope conveyed by the semi-basement window.

What is Parasite about? Parasite analysis straight from the director

Once the entire Kim family is employed in the Park household, the lower-class con-artists begin to assume more and more of this fabricated identity of wealth. They take the affluent home as their own while the Parks are away… and that’s when Moon-gwang shows back up and everything changes. Let’s shift gears from a Parasite summary to a Parasite movie analysis.

Related Posts

- Revisiting Road to Perdition →

- Collateral Movie Breakdown →

- FREE: StudioBinders Screenwriting Software →

What is Parasite About?

Parasite analysis: navigating the shift.

At its exact mid-point, Parasite undergoes a massive tonal shift. In our Parasite movie analysis video, this mid-point scene was the focus.

Be sure to watch our video essay on the scene for more detail and deeper Parasite analysis.

Parasite Genre Shift • Subscribe on YouTube

A tonal shift this extreme could easily take viewers out of the film or feel like a jumping-the-shark moment, but in the hands of Bong Joon-ho, this shift is portrayed in a way that not only feels effortless but greatly enhances each half of the film that preceded and follows it.

What is Parasite about? This excerpt reveals the script’s major plot twist

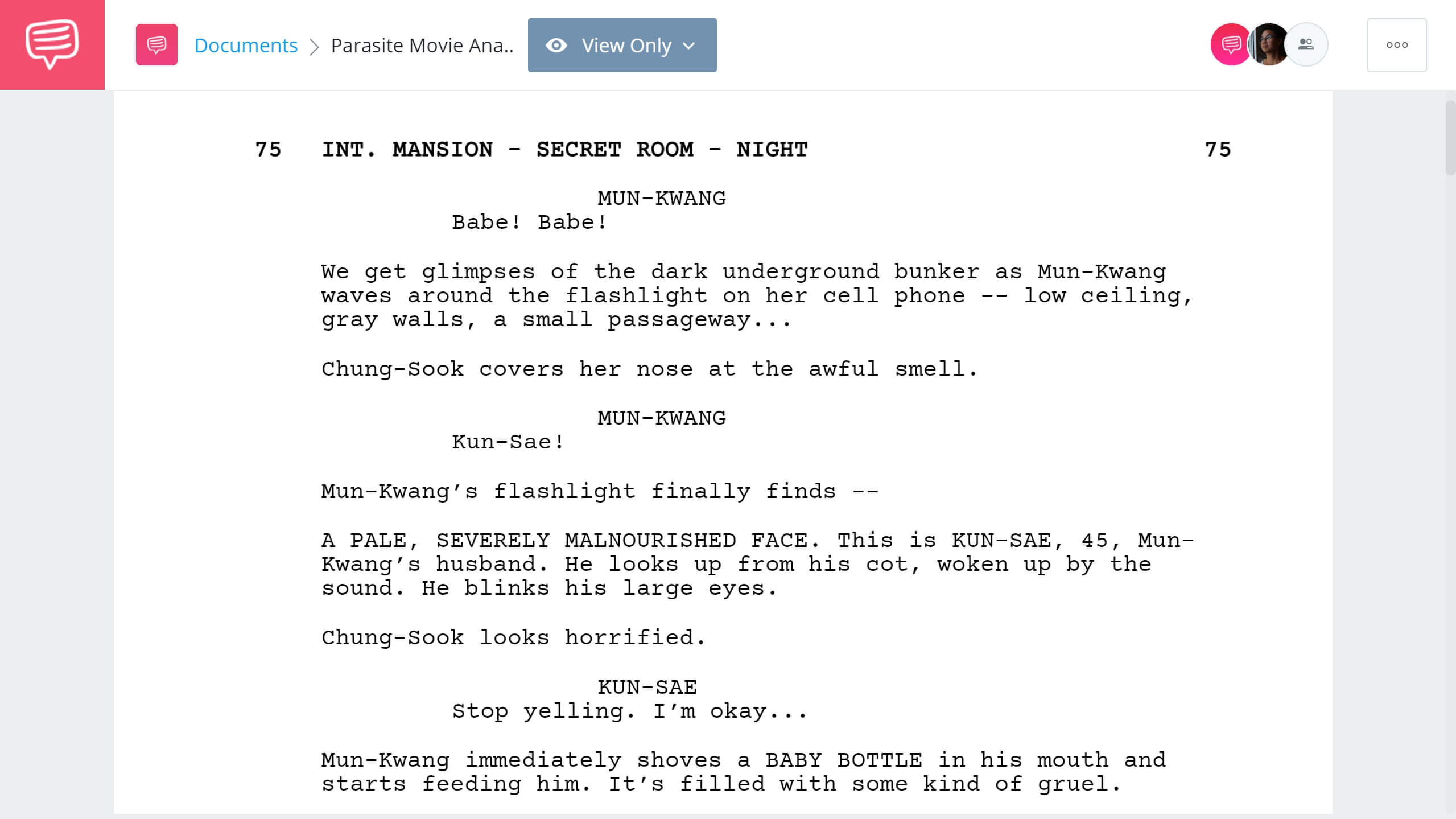

Moon-Gwang’s return to the house and eventual reveal of the secret basement keeps us on the edges of our seats as viewers and seamlessly blends from the drama/comedy centered first half into the thriller/tragedy centered latter half. Bong Joon-ho displays a mastery over genres and tones with this mid-point shift.

Did You Know?

Lee Jeong-eun, who plays Moon-Gwang the housekeeper, also provided the vocalization for Okja the super pig in Bong Joon-ho’s previous film.

Parasite synopsis

Parasite ending: orchestrating chaos.

Following the film’s major twist, Parasite continues in a far darker tone until it’s ending. In our Parasite movie analysis, we found that although the tone and style change, the themes at play remain consistent from the first half to the second half, and continue to be developed further as the film progresses.

Parasite’s final scene, in case you want a refresher on the chaos

For additional insights into director Bong Joon-ho’s creative process, listen to him discuss his decisions and directorial style with the other 2019 DGA nominees for best director including Martin Scorsese , Quentin Tarantino , Taika Waititi , and Sam Mendes :

Parasite summary and meaning discussed by filmmakers

Power shifts from Moon-gwang and her incognito husband to the Kim family as both lower-class families fight for leverage over each other. Both parties have dark secrets, and both threaten to expose the other to the Park family, who remain above all the drama, currently unaware. The film’s social commentary on class is at its strongest in this depiction of the lower classes fighting against each other rather than against the 1% who truly hold more accountability.

Outside of the sub-basement, violence erupts, and the prophetic scholar’s stone becomes an instrument of violence. Blood is shed and deaths are cast at the birthday party of the Park family’s youngest child.

All three families at play are damaged by this explosive act of violence. The Kim family is destroyed; Ki-jung is killed, Ki-woo is left brain-damaged, and Ki-taek is forced into hiding after he snaps and acts out a classism-driven murder in the chaos of the birthday party. The metaphorical themes are presented in as literal a way as possible with the act of this stabbing.

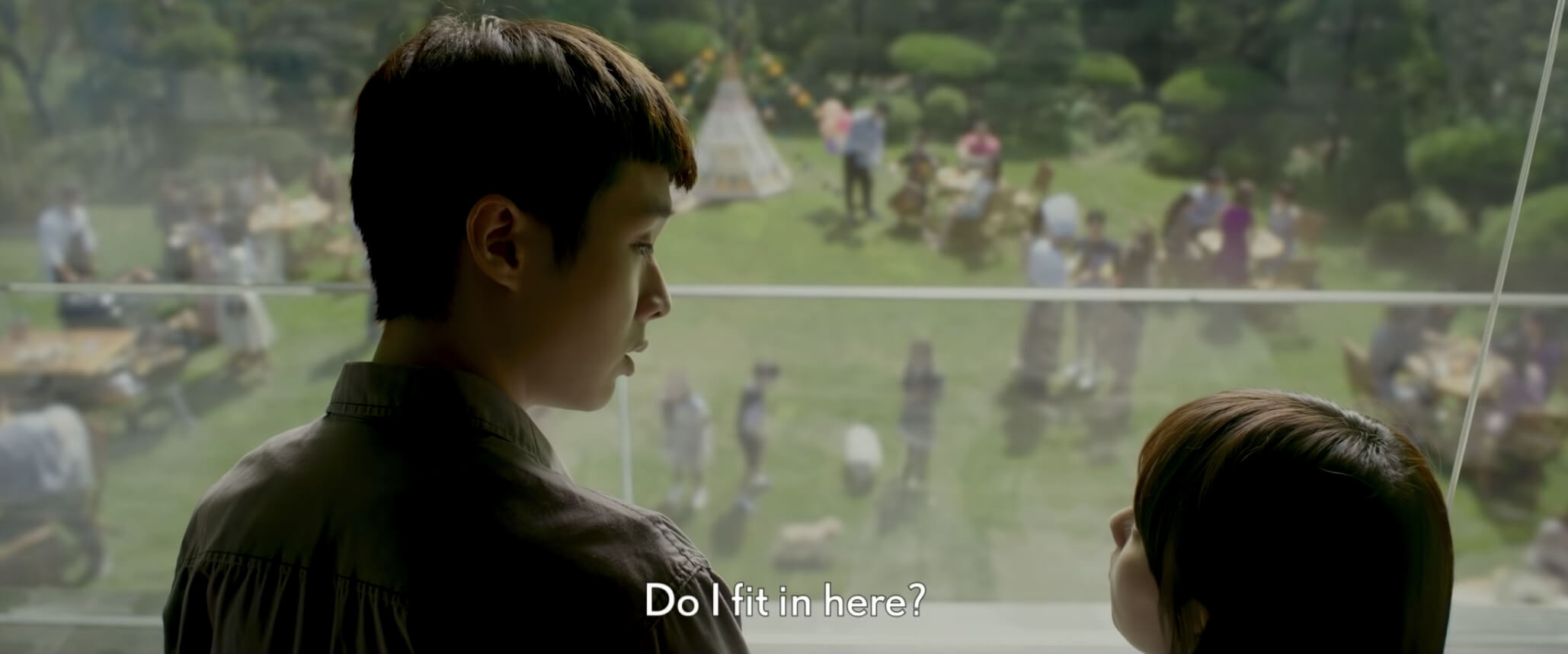

Ki-woo questions if his class prevents him from fitting in

Parasite’s ending features a sequence of Ki-woo’s plan to work hard, buy the house under which his own father now hides, and reunite the family… but this plan is nothing but a fantasy. The real Parasite movie ending is more bleak and, unfortunately, more realistic.

To explain Parasite’ s ending, we turn to the director’s own words: “You know and I know - we all know that this kid isn't going to be able to buy that house. I just felt that frankness was right for the film, even though it's sad." The emotionally-affecting resonance of the ending is the perfect cap to the wonderfully layered social commentary spread throughout the film.

But, before we dig deeper into the social commentary, let’s take a look at how the film managed to break through to an unmatched audience size.

- What is a motif in film? →

- The best movies of 2019, ranked →

- How to set dress like Bong Joon-ho →

Parasite 2019 Film

The spread of parasite.

Parasite has proven to be a groundbreaking achievement for South Korean movies. For years the country has been producing some of the finest films and directors in the world of cinema, but Parasite has crossed new milestones in terms of global impact.

Parasite director Bong Joon-ho became the first South Korean filmmaker to win best director at the academy awards. Has also tied the record with Walt Disney for most Oscars awarded to an individual at a single ceremony. This is especially impressive given how ethnocentric the Academy Awards often unfold, prioritizing English-language films over foreign-language films much of the time.

Parasite 2019 cleans up at the Academy Awards

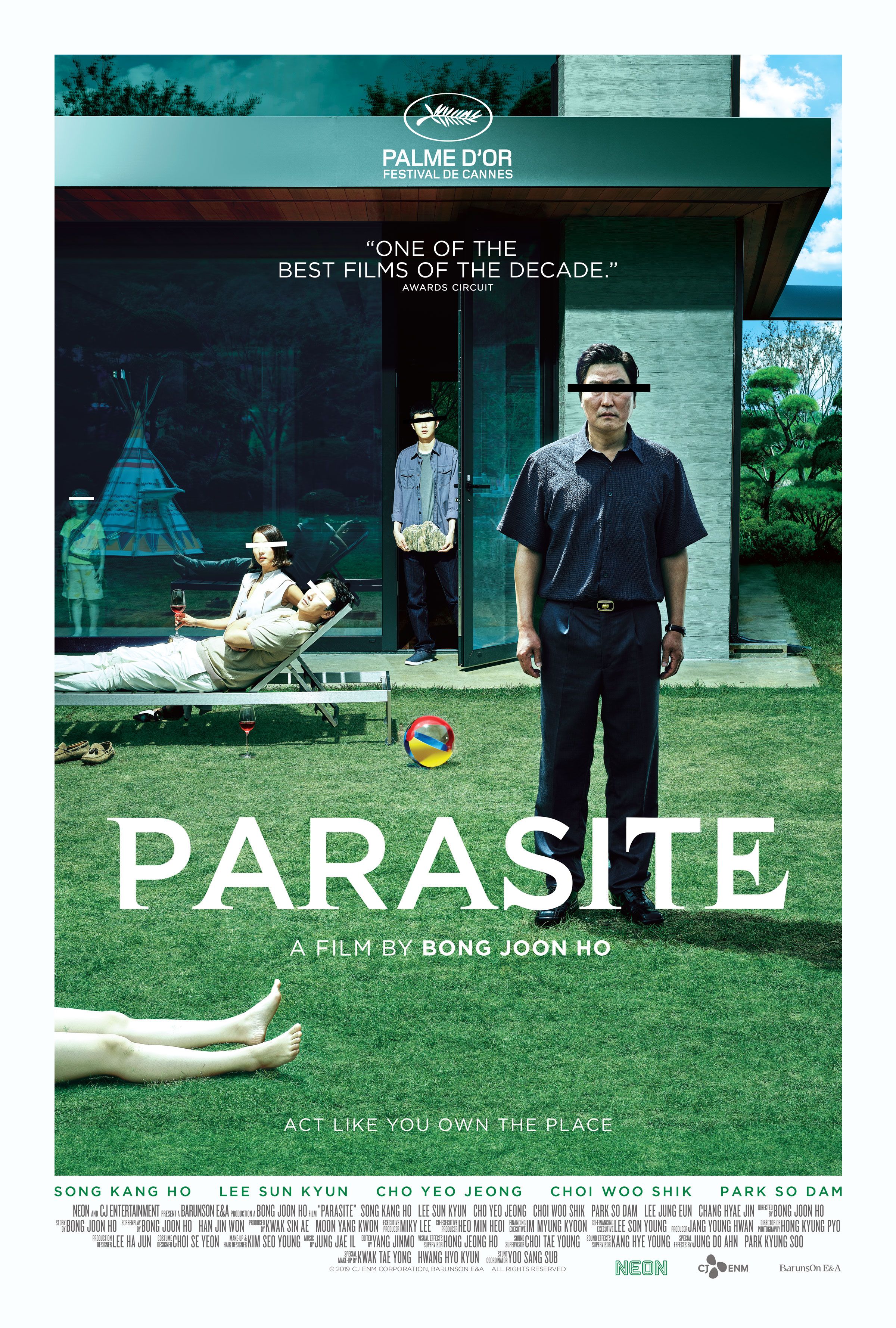

Parasite was not just the first South Korean film to win the foreign language prize at the Oscars but also the first foreign language film from any country to win the overall best picture prize. Equally impressive was Parasite becoming the first South Korean movie to win the Palme d’Or, which is the top prize at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival.

Parasite makes history by winning the Palme d’Or

Parasite was the first film since Marty in 1955 to win the top prize of both The Oscars and the Cannes Film Festival. These two powerhouse awards ceremonies rarely overlap and are comprised of entirely different audiences and judges and with entirely different viewing criteria and preferences. It speaks wonders to Parasite’s accessibility that it was received so well with such widely varying viewers.

The 2012 Academy Awards:

The Artist , a French and Belgian production, won best picture at the 2012 Academy Awards but was ineligible for the best foreign language film category as it is a silent film.

It wasn’t just awards records that Parasite broke in 2019. Parasite broke a number of financial records as well, including the highest foreign film opening weekend of all time for the UK box office, and a number of records with the Indie Box Office.

The record-setting trend continued for the Parasite film. After being added Hulu’s catalogue for exclusive streaming, it became the platform’s most streamed film in both the independent and foreign film categories, reaching even more audience members and wowing them with its immaculate presentation and resonant themes.

The cultural swell around Parasite is much deserved and hopefully leads more audience members to check out Parasite director Bong Joon-ho’s previous films and more South Korean cinema in general.

Parasite 2019 Meaning

Perfecting social commentary.

“What is the movie Parasite about?” has many answers. One clear way to explain the movie is: “ Parasite is about class.” Class is the primary target of social commentary within Parasite.

And every single element of the film from the scholar’s stone, to the architecture of the homes, to the very names of the families all contribute to this central theme. It’s no accident that the lower-class protagonists happen to have the single most common surname in South Korea.

Parasite 2019: The Kim family

It is one of the most effective satires in recent memory. For a quick breakdown on satire, including a segment on Parasite , here's an explainer that will answer all your questions about how satire works.

3 Types of Satire Explained • Subscribe on YouTube

Parasite has a lot worthy of analysis and it has a lot to say. One of the main reasons why Parasite was such a massive success around the whole world in 2019 is because of its themes and messages of classism and the wealth divide, which are truly universal. These themes cross all cultural-barriers and can speak to the 99% anywhere in the world.

The topic of class is one that Bong Joon-ho has a clear fascination with. He’s skewered classicism in all of his films to some degree. Prior to Parasite in 2019, his most focused social commentary on class was found in his 2013 film Snowpiercer which saw the lower class positioned at the back of a train in squalid conditions while the wealthy lived large at the head of the train.

This same subject of class is less overt in Parasite but far more grounded and effectively subtle to the point of never overshadowing the story being told for the sake of its themes.

Tilda Swinton monologues about class in Snowpiercer • 2013

For a full deep-dive analysis into how the themes of Parasite were previously tackled in Bong Joon-ho’s other films, check out this video essay on the subject:

Parasite 2019 movie analysis

The Kim family may be below the Parks in status, but even they can look down on Moon-gwang and her husband. This secret basement reveals an even lower level of status below what we had thought was the floor with the Kim family.

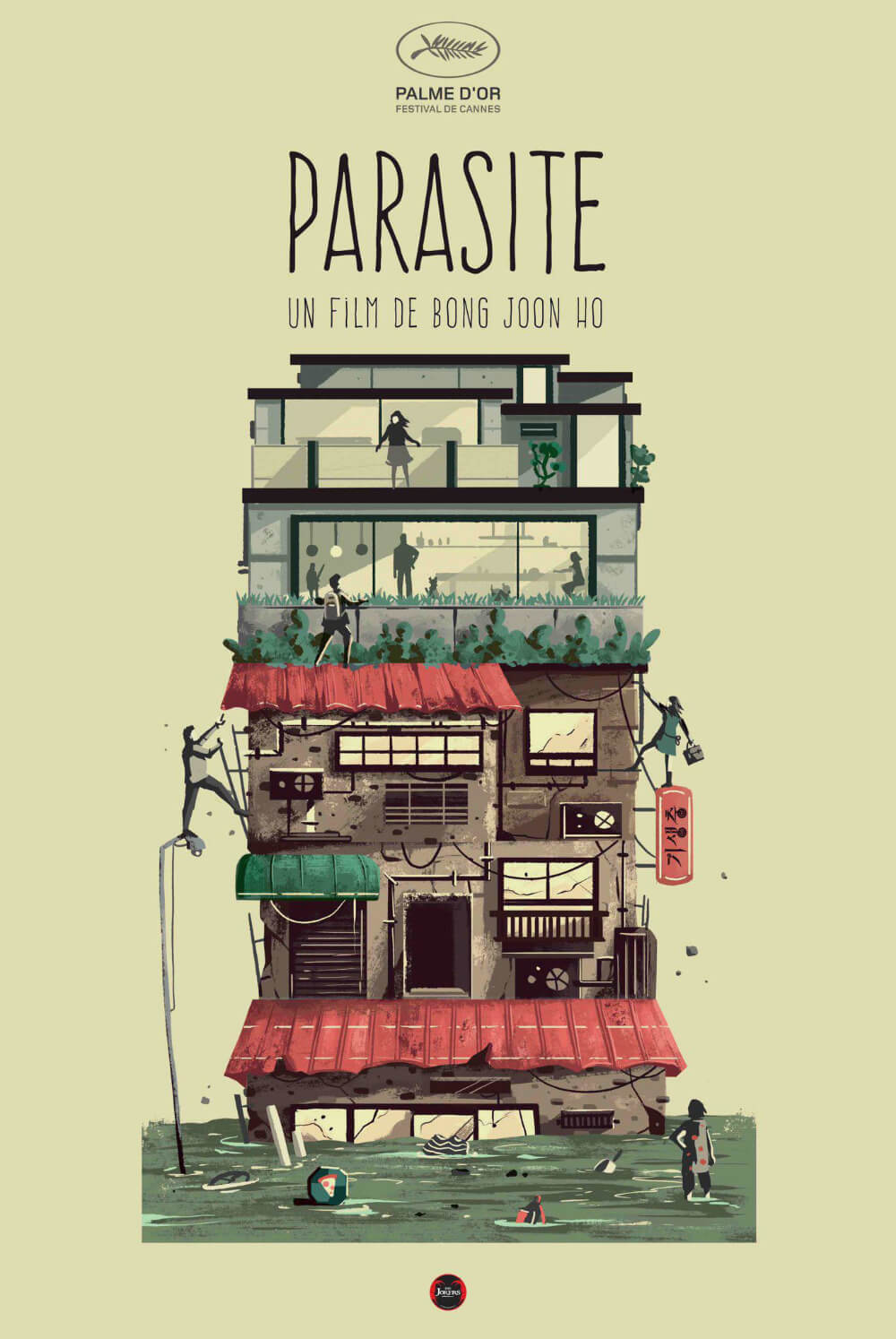

Elevation clearly equates to status; the park’s have a multi-level home at the top of the hill while the Kim’s live below street level in a semi-basement, and the surprise 3rd party lives deep underground in a sub-basement. This vertical comment on status is illustrated cleanly in this alternate poster for the film, without spoiling the sub-basement reveal.

The flooding sequence, as depicted on the poster, also illustrates how the wealthy are unaffected by many of the debilitating circumstances that affect the lower classes as they are, quite literally, above the trouble.

Parasite movie analysis in poster form

Parasite represents the most focused and refined approach to class as a subject that Bong Joon-ho has achieved, and that’s certainly saying something given his impressive body of work.

How to set-dress like Bong Joon-ho

For more Parasite movie analysis, check out our article on how Bong Joon-ho creates meaning through set dressing. The article breaks down how to identify and breakdown set elements in a screenplay. Follow along with the Parasite script as StudioBinder is used to recreate what the actual script breakdown may have looked like.

Up Next: Set dressing in Parasite →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is a Femme Fatale — Definition, Characteristics, Examples

- What is Method Acting — 3 Different Types Explained

- How to Make a Mood Board — A Step-by-Step Guide

- What is a Mood Board — Definition, Examples & How They Work

- How to Make a Better Shooting Schedule with a Stripboard

- 96 Facebook

- 1.2K Pinterest

- 36 LinkedIn

87 Parasite (2019)

Class, colonialism, and gender in parasite (2019).

By Colson Legras

Throughout the history of cinema, especially in our modern, information-saturated, on-demand world, the English language has dominated the film industry and all forms of media at large. This has made the average person prone to becoming overly accustomed to a predominantly English-language media environment at the cost of exposing them to works from languages and cultures outside the Anglosphere’s influence. As a result, it is very common for English-speaking viewers to have more difficulty connecting or relating to stories that aren’t in the English language and require subtitles. This too often leads to a clunky and disconnected viewing experience.

The 2019 Korean genre-hybrid film Parasite breaks free from those typical restraints by offering a compelling and captivating narrative experience combined with a universally relatable message of the injustice of increasing class and wealth inequality in the world, while also touching on issues of gender and colonialism. More than anything else, the film presents its social message in a way that seamlessly translates across language and cultural barriers thanks to its masterful editing, mise-en-scene, cinematography, music, acting, and writing. Interspersed throughout the film are countless implementations of these elements of film form to illustrate the differences between two South Korean families, how their interactions highlight the power dynamic between them, and the distinct ways they each interact with society due to these differences.

Parasite entered the public consciousness among growing awareness and frustration with the rise of wealth inequality and its perverse effects on governments, individuals, and society as a whole, which if anything, have only gotten worse since the pandemic. The film echoes the grievances many people hold with capitalism, poverty, and the existing social order. Its setting in South Korea is relevant, although not integral, to the films’ overall purpose of portraying inequality and social mobility in a very cynical and pessimistic light. In her review of the film, The New York Times’s Michelle Goldberg calls this approach “bracing” due to its raw and honest presentation of these themes and stark contrast with typical sensibilities about class distinction and social mobility in America, which tend to depict differences in social class in either a positive light or as a necessary evil (Goldberg).

Bong Joon-ho, the director and co-writer of Parasite , is no stranger to depictions of class differences on screen. As film critic Mark Kermode points out in his review in The Guardian , Bong’s back catalog of films, including Memories of Murder, The Host , and Snowpiercer , is well-known for not-so-subtle commentaries on wealth, power, and authority (Kermode). Parasite ’s rendition of this class dynamic focuses on two Seoul families: the Kims, a poor and desperate family living in a basement apartment, and their goal of infiltrating and each becoming employed by the Parks, a very wealthy family led by the head of a successful tech company. Bong in several instances highlights the two families’ differences in wealth and social standing using a variety of methods. The first instance of this occurs very early in the film when we see the Kim family search all around their small apartment for a stray wifi signal (2:55). Most of the camera shots in this scene are medium to close-up shots meant to invoke a claustrophobic feeling from being in the tiny basement apartment, as well as to get a more intimate feel with the characters.

Mise-en-scene is very important in this scene as well, as we see just how small, cramped, and messy the Kim family’s apartment is, which is indicative of their social class. This can be contrasted with the portion of the film revealing the Park residence, which uses wide establishing shots (13:00) and camera panning around the entirety of the property (13:45) to give a sense of spaciousness, privacy, and pristineness, characteristics more associated with the upper-class. Kermode also mentions in his review the use of staircases and escalators to mirror the ascent and descent of the social ladder. During the Kim family’s infiltration into the rich Park household, the Kims’ father Ki-taek is shown ascending an escalator with the Parks’ mother (41:00), showing the Kim family’s ascent into a higher level of class and opportunity. In the second half of the film as their plan starts to fall apart, they are forced to return home in the middle of the night during a thunderstorm, scaling down several flights of stairs in the pouring rain (1:33:10). Using a series of wide shots, the Kim family descending the flights of stairs reflects their descending of the social hierarchy as their position in the Park household, and in turn their economic security, is compromised (Kermode). Another example that stands out is the difference in the diets of the Parks and Kims. The top-down camera angles and jump-cut edits at (39:50, 40:25) contrast the fresh fruit eaten at the Park household with the cheap, greasy pizza that the Kims eat together. Editing is also used effectively to highlight the difference in abundance and material wealth, when the Parks’ huge walk-in closet and wide selection of high-end clothes is juxtaposed with the Kims choosing from a pile of secondhand charity clothes (1:43:00).

With any story of class differences come the varying levels of power that the members of each class have, and in fact, the amount of power one has in society is a defining characteristic of one’s social class. In Parasite , the power of the Park family is evident throughout the film, as is the Kim family’s lack thereof. One of the ways Bong Joon-ho emphasizes the power that comes with elevated social status is through physical elevation. For example, the Parks have a housekeeper who lives at the residence with them and will do any chore and favor desired by the Parks on a whim, and is both physically and financially subservient to them. Her room is shown as being on the first floor (44:30), while each of the members of the Park family all sleep on the top floor, showing their position above the working-class housekeeper socially and literally. This is also echoed later in the film when it is revealed the housekeeper’s husband has been living beneath the house in a secret bunker. The Kim family’s overwhelming lack of power is on display as well. They find it difficult to persuade even a pizza shop worker to hire Ki-woo as a part-time worker (5:20), even as they all surround her. With a medium shot that gradually zooms in on the pizza worker, this is also an example of how the limited amount of power the Kim family does have is from their strength in numbers and ability to coordinate and work together, which is further explored later in the film.

As the narrative of Parasite progresses, so does the tension between the Kim family and the Park family, as well as between them and the housekeeper and her husband. As this conflict plays out in the foreground, a conflict rooted in class stirs up in the background, leading up to an explosive conclusion. Throughout the film, the Parks, particularly the patriarch Mr. Park, draw distinctions between themselves and their ilk and those below them on the totem pole, and discriminate based on those class distinctions. He emphasizes the value of subordinates who don’t “cross the line” (43:40) by involving themselves too much in his business or positioning themselves as his peers. In another scene, Mr. Park distastefully recounts to his wife the pungent smell which emanates from Ki-taek and “people who ride the subway” (1:28:40). This scene is particularly illuminating into the differences between the classes which the Kims and Parks are a part of and the attitudes and resentments they hold towards each other. While Mr. and Mrs. Park are shown lying together on their couch, the camera moves down to a low shot to show the Kims under a table within earshot (1:27:40). This repeats the allegory of representing class with one literally being physically above the other, while emphasizing the powerlessness of the Kims beneath them who are forced to stay silent and undetected.

The metaphor of smell to illustrate revulsion towards lower-class people is exhibited again in a later scene, when the Park family is preparing for an impromptu birthday party for their son, Da-song. The mother runs errands while being driven around by Ki-taek. In part due to the flood of sewage water which ravaged their home the night before, his smell was particularly noticeable to Mrs. Park, which elicited visible disgust from her. At the party, a dramatic and hectic scene played out in which the housekeeper’s husband, Geun-se, goes on a violent rampage which, among other things, results in himself being fatally stabbed. While trying to reach his car keys which became lodged under Geun-se, Mr. Park attempts to grab them but is visibly taken aback and disgusted by his smell (1:54:20). He also completely ignores both Ki-jung and Ki-woo, who are both bleeding profusely and need immediate medical attention, instead prioritizing the unconscious Da-song. This is emblematic of the apathy that Mr. Park has for those from a lower social class. In retaliation for his contempt and carelessness, Ki-taek spontaneously stabs Mr. Park in the chest, killing him.

Although the film is primarily a critique of class stratification and inequality, there certainly are other elements present. For instance, gender relations and roles are relevant to many of the characters’ identities, such as the Park’s daughter Da-hye and her ensuing relationship with the significantly older Ki-woo. The roles the female characters generally take on in the film when it comes to family life are relevant as well. The members of the Kim family all seem to consider themselves as equals, no matter the gender. A very insular and close-knit family, they prefer to cooperate and work together, each taking on a roughly equal role in the household. It isn’t until they immerse themselves in the household of the Parks and their upper-class environment that they begin to replicate gendered norms, such as the mother becoming the new housekeeper. The Park family, on the other hand, is much more patriarchal. The mother stays at home and takes care of the kids, while the father is the sole breadwinner of the household. He also seems to give preferential treatment to his younger son as opposed to his high school-aged daughter, only ever interacting with her to scold her. This depiction of gender in the film is representative of the notion that higher social class and wealth are often closely tied with male power in society and the fact that the higher up the social ladder you go, the more patriarchal it generally becomes. This is backed by data as well; CNBC’s Zameena Maija pointed out that in 2018, only 4.8% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies were female (Maija).

However, what strikes me as a particularly interesting element intertwined with the film’s themes of class and capitalism that lies in the background of the film is racial: the odd focus on Native Americans on the part of Da-song. He has a strange obsession with Native American tropes, carrying a toy bow and arrow, wearing a headdress, and camping outside in a teepee. His parents even theme his birthday party around them. Native Americans obviously don’t have a significant place among Korean race relations, so it seems odd to include in a Korean blockbuster film. I hadn’t even given this part of the film a second thought until it had been pointed out to me by a friend. Its symbolism becomes clearer upon noticing that every time that Da-song’s toys are brought up, his mother mentions that she “ordered it from the U.S.” (18:40, 1:27:20). The specificity of that phrase suggests it’s much more than a nod towards the perceived quality of American-manufactured goods. It seems to be a broader commentary on colonialism and imperialism, and how the United States expanded and exported these behaviors and ideologies along with capitalism during its 19th century westward expansion in Native American territory, as well as its postwar rise to global superpower status. This is specifically relevant to South Korea, which owes much of its existence and success to its alliance to U.S. political and military interests and adoption of neoliberal economic policy. In the same way that the Parks imported the teepee and bow and arrow as consumer products from America, South Korea imported America’s capitalistic, stratified social order, in addition to its commodification of cultures like we see with Da-song’s obsession with Native Americans. The climactic birthday party scene explores this concept further. Mr. Park and Ki-taek, both in Native headdresses, are about to surprise Da-song by pretending to ambush Ki-jung with tomahawks and “battle” with Da-song (1:48:00). This choice to portray Native Americans not as a group of people to be understood, but as a vague, faceless idea of antagonistic, warmongering savages is deliberate. It reflects the broader history of Native Americans on film and their legacy in general: the tendency of other more powerful groups to determine their stories and fate for them, rather than letting them determine it for themselves. In replicating this dynamic, the film does not endorse it; rather, it critiques it through imitation.

Social messaging aside, the film is also extremely engaging and enthralling and stands on its own even without the subtext of critique of inequality. All that said, I would instantly recommend this film to anyone, regardless of their interest in foreign films or desire to read subtitles, because in the case of Parasite , it easily ranks as one of the greatest films of the decade.

If there’s one thing Parasite does best of all, it’s bringing attention to a pressing social issue in a way that dissolves cultural and language boundaries and reaches a wide audience without compromising its cinematic complexity. It achieves this goal in a variety of ways; realizing its wider audience likely isn’t fluent in Korean, its acting, writing, and subtitling allows the viewer to effortlessly immerse themselves in the film’s world, making the cultural setting and language function more as a backdrop than as an obstacle. Most importantly, Parasite ’s main takeaways, that wealth inequality is the result of factors largely outside one’s control, that class differences aren’t totally earned, and social mobility is a bygone dream for many, all have the potential to resonate with audiences from all cultural backgrounds. This is at the heart of why the film is so impactful both emotionally and culturally.

Parasite is uniquely significant for several reasons, many of which have more to do with public perception than the actual filmmaking process. The biggest reason this film is relevant to the public, myself included, is largely because of deep dissatisfaction with the effects of social stratification and a capitalistic culture on society. In particular, Hollywood, with its endless sequels, remakes, and the concentration of production rights into the hands of fewer and fewer media companies, is certainly a prime example of this. Filmgoers have noticed, and Parasite , both as a foreign film which turns genre conventions upside-down and as a critique of the typical cultural assumptions that Hollywood helps perpetuate, is a breath of fresh air from the fumes of Hollywood. The fact that, despite its language barrier, the film easily plowed through the Oscars to receive Best Picture and became many fans’ favorite film of the year proves that its idea of class inequality being arbitrary, unmerited, and unjust is resonating with more and more people each day. In many ways, Parasiteand the success it has spawned represent a massive ongoing paradigm shift in how we talk about issues like class, inequality, and the film industry: one that we’ll be feeling the ripple effects from for decades to come.

Goldberg, Michelle. “Class War at the Oscars.” The New YorkTimes, 11 Feb. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/opinion/parasite-movie-oscar-inequality.html.

Kermode, Mark. “Parasite Review – a Gasp-Inducing Masterpiece.” The Guardian, 10 Feb. 2020, www.theguardian.com/film/2020/feb/09/parasite-review-bong-joon-ho-tragicomic-master piece.

Mejia, Zameena. “Just 24 Female CEOs Lead the Companies on the 2018 Fortune 500-Fewer than Last Year.” CNBC, 21 May 2018, www.cnbc.com/2018/05/21/2018s-fortune-500-companies-have-just-24-female-ceos.html.

Difference, Power, and Discrimination in Film and Media: Student Essays Copyright © by Students at Linn-Benton Community College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

It’s so clichéd at this point in the critical conversation during the hot take season of festivals to say, “You’ve never seen a movie quite like X.” Such a statement has become overused to such a degree that it’s impossible to be taken seriously, like how too many major new movies are gifted the m-word: masterpiece. So how do critics convey when a film truly is unexpectedly, brilliantly unpredictable in ways that feel revelatory? And what do we do when we see an actual “masterpiece” in this era of critics crying wolf? Especially one with so many twists and turns that the best writing about it will be long after spoiler warnings aren’t needed? I’ll do my best because Bong Joon-ho ’s “Parasite” is unquestionably one of the best films of the year. Just trust me on this one.

Bong has made several films about class (including “ Snowpiercer ” and “ Okja “), but “Parasite” may be his most daring examination of the structural inequity that has come to define the world. It is a tonal juggling act that first feels like a satire—a comedy of manners that bounces a group of lovable con artists off a very wealthy family of awkward eccentrics. And then Bong takes a hard right turn that asks us what we’re watching and sends us hurtling to bloodshed. Can the poor really just step into the world of the rich? The second half of “Parasite” is one of the most daring things I’ve seen in years narratively. The film constantly threatens to come apart—to take one convoluted turn too many in ways that sink the project—but Bong holds it all together, and the result is breathtaking.

Kim Ki-woo (Choi Woo-sik) and his family live on the edge of poverty. They fold pizza boxes for a delivery company to make some cash, steal wi-fi from the coffee shop nearby, and leave the windows open when the neighborhood is being fumigated to deal with their own infestation. Kim Ki-woo’s life changes when a friend offers to recommend him as an English tutor for a girl he’s been working with as the friend has to go out of the country for a while. The friend is in love with the young girl and doesn’t want another tutor “slavering” over her. Why he trusts Kim Ki-woo given what we know and learn about him is a valid question.

The young man changes his name to Kevin and begins tutoring Park Da-hye (Jung Ziso), who immediately falls for him, of course. Kevin has a much deeper plan. He’s going to get his whole family into this house. He quickly convinces the mother Yeon-kyo, the excellent Jo Yeo-jeong, that the son of the house needs an art tutor, which allows Kevin’s sister “Jessica” ( Park So-dam ) to enter the picture. Before long, mom and dad are in the Park house too, and it seems like everything is going perfectly for the Kim family. The Parks seem to be happy too. And then everything changes.

The script for “Parasite” will get a ton of attention as it’s one of those clever twisting and turning tales for which the screenwriter gets the most credit (Bong and Han Jin-won , in this case), but this is very much an exercise in visual language that reaffirms Bong as a master. Working with the incredible cinematographer Kyung-pyo Hong (“ Burning ,” “Snowpiercer”) and an A-list design team, Bong’s film is captivating with every single composition. The clean, empty spaces of the Park home contrasted against the tight quarters of the Kim living arrangement isn’t just symbolic, it’s visually stimulating without ever calling attention to itself. And there’s a reason the Kim apartment is halfway underground—they’re caught between worlds, stuck in the growing chasm between the haves and the have nots.

“Parasite” is a marvelously entertaining film in terms of narrative, but there’s also so much going on underneath about how the rich use the poor to survive in ways that I can’t completely spoil here (the best writing about this movie will likely come after it’s released). Suffice to say, the wealthy in any country survive on the labor of the poor, whether it’s the housekeepers, tutors, and drivers they employ, or something much darker. Kim’s family will be reminded of that chasm and the cruelty of inequity in ways you couldn’t possibly predict.

The social commentary of “Parasite” leads to chaos, but it never feels like a didactic message movie. It is somehow, and I’m still not even really sure how, both joyous and depressing at the same time. Stick with me here. “Parasite” is so perfectly calibrated that there’s joy to be had in just experiencing every confident frame of it, but then that’s tempered by thinking about what Bong is unpacking here and saying about society, especially with the perfect, absolutely haunting final scenes. It’s a conversation starter in ways we only get a few times a year, and further reminder that Bong Joon-ho is one of the best filmmakers working today. You’ve never seen a movie quite like “Parasite.” Dammit. I tried to avoid it. This time it’s true.

This review was filed from the Toronto International Film Festival on September 7th.

Brian Tallerico

Brian Tallerico is the Managing Editor of RogerEbert.com, and also covers television, film, Blu-ray, and video games. He is also a writer for Vulture, The Playlist, The New York Times, and GQ, and the President of the Chicago Film Critics Association.

- Song Kang-Ho as Kim Ki-taek

- Lee Sun-Kyun as Park Dong-ik

- Cho Yeo-jeong as Yeon-kyo ( Mr. Park's wife )

- Choi Woo-shik as Ki-woo ( Ki-taek's son )

- Park So-dam as Ki-jung ( Ki-taek's daughter )

- Lee Jung-eun as Moon-gwang

- Chang Hyae-jin as Chung-sook ( Ki-taek's wife )

- Bong Joon-ho

- Han Jin-won

Director of Photography

- Hong Kyung-pyo

Original Music Composer

- Jung Jae-il

- Yang Jin-mo

Leave a comment

Now playing.

We Live in Time

Look Into My Eyes

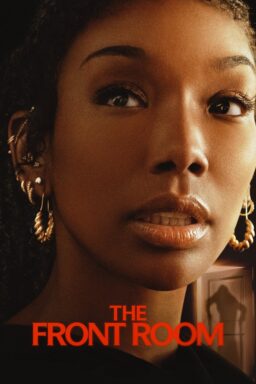

The Front Room

Matt and Mara

The Thicket

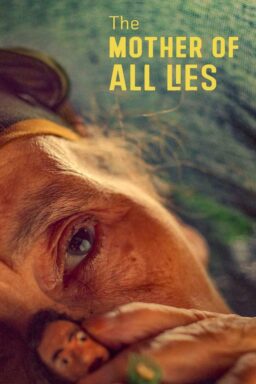

The Mother of All Lies

The Paragon

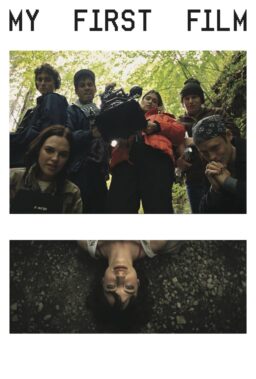

My First Film

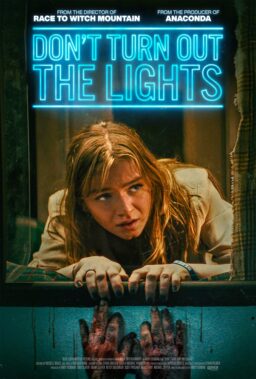

Don’t Turn Out the Lights

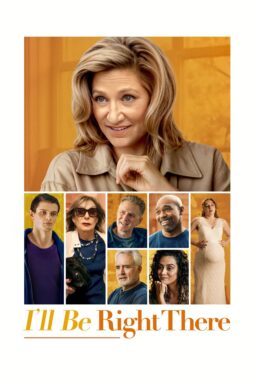

I’ll Be Right There

The Greatest of All Time

Latest articles.

TIFF 2024: Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, Sharp Corner, The Quiet Ones

TIFF 2024: Dahomey, Bird, Oh Canada

TIFF 2024: The Cut, The Luckiest Man in America, Nutcrackers

The Telluride Tea: My Diary of the 2024 Telluride Film Festival

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

The Criterion Collection

- My Collection

Parasite: Notes from the Underground

By Inkoo Kang

Oct 30, 2020

- Icon/Share/Facebook

- Icon/Share/Twitter

- Icon/Share/Email

F or a film that ultimately delivers such an outraged, sorrowful, and incisive message about class inequity and the humanity-crushing mechanisms needed to maintain it, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite (2019) begins with surprising levity, with a twist on a classic heist. The plot is set in motion by a tiny ruse—on the misleading recommendation of a college-student friend, Kim Ki-woo (Choi Woo Shik) gets himself hired as an English tutor for Park Da-hye (Jung Ziso), the teenage daughter of a well-heeled family—that snowballs into a daring swindle. Although early in the film we see Ki‑woo beg unsuccessfully for a part-time job at a pizzeria, his (forged) degree and nom de guerre, Kevin, make him not just worthy but above suspicion in the Parks’ rarefied Seoul neighborhood.

When Ki-woo first arrives at the Parks’ urban estate—its expansive, verdant yard a shocking oasis within ultradense Seoul—he is uninitiated enough in the customs of the jet set to mistake the uniformed housekeeper, Moon-gwang (Lee Jung Eun), for the lady of the house. He recovers quickly. Ki-woo’s performance of affluence and exclusivity—which, as much as the English lessons, is what Mrs. Park (Cho Yeo Jeong) is paying for—soon rivals in sneaky mischief the “chain of recommendations” that follows. Ki-woo gets his younger sister, Ki‑jung (Park So Dam), seemingly just out of high school, appointed as an art therapist for the Parks’ young son, Da-song (Jung Hyeon Jun), by passing her off as an acquaintance named Jessica and credentialing her with an American education. The Kim siblings then scheme to oust the Parks’ driver and housekeeper and replace them with their father (Song Kang Ho) and mother (Chang Hyae Jin), both posing as strangers to each other and to their children under the Parks’ roof.

Ki-woo and Ki-jung’s flawless pantomime of prestige is pure genre pleasure, as is the Kims’ masterful manipulation of the Parks’ anxieties about the employees on whom they depend. The wealthy family, so fearful about hiring the wrong people, couldn’t have hired wronger people. But unlike, say, Danny Ocean and his gang in Ocean’s Eleven, the Kims aren’t out for a wad of cash. They may be manufacturing false identities to make more money than they’ve ever dreamed of, but, even in this bit of asymmetrical class warfare, the grand prize they’re after is still just the privilege of being the help. The clever repurposing of blockbuster tropes is a Bong calling card, as is the deep undertow of sociological grimness beneath the tension-filled high jinks. After the Kims’ “heist,” Parasite ’s social satire, tightly plotted caper, and character-based comedy give way to action sequences, horrorlike starts and stabs, and, ultimately, stinging tragedy. The epistolary coda makes the act of hope pitiable.

Often described as South Korea’s Steven Spielberg—a crowd-pleasing filmmaker who has enjoyed wide critical acclaim and astronomical box-office success—Bong is an artist remarkably at ease in an array of tones and registers, and is boyishly gleeful in mixing them to unnerving ends. Despite his genial public appearances, it’s easy to take the director at his word when he describes himself as a weirdo and a misfit, as he often does in interviews. After spending part of his childhood in conservative Daegu, in southeastern South Korea, he moved with his family to Seoul and then became a university student there in the late 1980s, and soon a left-leaning, pro-democracy activist—one who would also occasionally abandon a protest in order to go watch a movie. With tear gas unleashed on his campus just about every day during his first two years of college, Bong, a sociology student at the time, became well acquainted with the violence with which unjust systems often defend themselves.

In the early nineties, Bong dedicated himself to film, and after a decade of odd jobs in the South Korean film industry, he shot to the top of the field with three consecutive masterpieces: Memories of Murder (2003), a deglamorized serial-killer mystery that uncomfortably confounds expectations; The Host (2006), a searing, Godzilla-inspired political satire that became Bong’s international breakthrough; and Mother (2009), another formula-eschewing procedural that doubles as a study of social vulnerability, about a late-middle-aged woman determined to exonerate her intellectually disabled son from a homicide charge. As it happens, the closest antecedent to Parasite is the similarly titled The Host, with both films using familial tragedy to launch larger political critiques.

Then came his international projects, with big budgets, big stars (like Chris Evans, in 2013’s dystopian sci-fi thriller Snowpiercer ), and instant worldwide distribution through the likes of Netflix, which released the E.T. -esque animal-rights action adventure Okja (2017). Ironic, then, that it was his homecoming film, Parasite —his first fully South Korean–set feature in a decade—that really seized the world’s attention, winning Bong his country’s first Palme d’Or, as well as the first-ever best picture Academy Award for a non-English-language movie.

“Parasite stands out in Bong’s filmography for the severity of its conclusion, but in most ways it is the apotheosis of the auteur’s signature concerns and techniques.”

P arasite stands out in Bong’s filmography for the severity of its conclusion, but in most ways it is the apotheosis of the auteur’s signature concerns and techniques. Like many of his compatriot directors, Bong is preoccupied with the chasm between the haves and the have-nots. (Despite his towering status in the South Korean film industry even before Parasite ’s four Oscar wins, his ideological convictions got him temporarily blacklisted, along with more than nine thousand other writers and artists, from receiving state subsidies by the conservative administration of since-impeached president Park Geun-hye. Korean audiences apparently missed him; Parasite was a notable critical hit and reportedly seen by a fifth of the country.) But Bong seldom lets his proles rest easy in their righteous victimhood. In many of his films, the downtrodden bully the abject, their valid resentments blinding them to their own exploitations of power. In Parasite, it’s not the wealthy Parks who pose the greatest danger to Moon-gwang and her bunker-dwelling husband (Park Myung Hoon) but rather the hardscrabble Kims. In fact, the Parks don’t know—may never know—how viciously the two struggling families have to vie with each other for steady paychecks. Wealth buys the Parks an ignorance of hardship—and a kind of untested virtue. After Mr. Kim notes that Mrs. Park is “rich but still nice,” he is swiftly corrected by his wife. Mrs. Park is “nice because she’s rich,” explains Mrs. Kim; she hasn’t ever had to harden herself. Forget her three Birkin bags; Mrs. Park’s gullibility is the film’s ultimate status symbol.

What is new to Bong’s analyses of class friction in Parasite is the film’s disillusionment with the promise of social mobility, particularly for young adults—as symbolized by the scholar’s stone, a talisman that was gifted to the Kims and is meant to bring wealth to its possessor, to which Ki-woo displays an irrational attachment. ( Burning, the 2018 Lee Chang-dong thriller about a twentysomething deliveryman who suspects that a deep-pocketed acquaintance has killed for sport the woman they were competing to romance, also channels this kind of economic rage.) It is perhaps precisely this naked despair about a vanished social ladder that has found such resonance with American audiences, whose faith in their institutions continues to reach new lows. Hollywood movies are still largely built around exceptional individuals who can overcome any obstacle in their path. Bong’s protagonists, in contrast, seldom get to fulfill their cinematic destinies: the cops don’t catch the bad guy, the everydad doesn’t rescue his kidnapped daughter. Parasite lets Ki-woo dream that he, too, can be a film protagonist, the heroic anomaly—then exposes his self-delusion for what it is.

Parasite isn’t a boastfully beautiful picture, but it does supply us with an indelible visual contrast between the Kims’ overpacked, wire-festooned semibasement apartment and the Parks’ honey-toned but aggressively rectangular designer home. Both domiciles feature living rooms with wide windows (which parallel each other in “aspect ratio”), but the Kims literally look up at the world when they gaze out through theirs (and frequently see a sot pissing on the street beside the glass), while the Parks, who live behind a wall on top of a hill, have their view of the rest of the city occluded by dense panels of trees. In the back of every Korean viewer’s mind would be Seoul’s mountainous topography, which doesn’t need to be seen to expand the metaphor of the wealthy above and the poor below.

To get to their neighborhood from the Parks’ bespoke abode, the Kims must walk down many flights of grimy stairs. Their sunken apartment was apparently built in such slapdash fashion that the toilet is perched on a platform, comically making it the highest-situated spot in the home. When a storm hits, the Kims’ subterranean dwelling is flooded with sewage water; Mrs. Park, on the other hand, is so cheered by the fresh morning-after air that she throws an impromptu party for her son.

Even lower-lying than the semibasement apartment, of course, is the bunker in which some of the greatest horrors of the film take place. Part of the suspense of Parasite is watching the disparity between upstairs and downstairs grow untenably vast. When the Parks return home from an aborted camping trip, their biggest worry is that their son, who insists on sleeping in the yard in a tepee, will catch a cold. Several feet below, the original housekeeper’s husband, Geun-se, watches his beloved wife die after the Kims’ attack. By the end of the film, when Geun-se decides he can’t stay underground anymore, he hurls the scholar’s stone at Ki-woo’s already bleeding head (unaware of how aptly he is punishing the young man for his rags-to-riches fantasies), even as the Parks and their friends are making up the very picture of decadence above, picnicking on exotic foods in posh outfits, regaled by the favored musical genre of movie villains everywhere: opera.

“Much of Parasite ’s appeal, though, is that Bong’s humor keeps the class allegory from ever feeling self-important or didactic.”

Much of Parasite ’s appeal, though, is that Bong’s humor keeps the class allegory from ever feeling self-important or didactic. The genre subversions do much of this leavening work. Moon-gwang wields her cell phone, with its extortionate material, like a gun against the Kims, and when the two lower-class families tumble into a melee, the deciding weapon—in lieu of, perhaps, a firearm discharged into the air—is a bag of peaches.

Parasite exemplifies Bong’s often earthy, occasionally envelope-pushing jokes, which are deployed here to add intersectional nuance to the film’s class critique. The exquisitely awkward sex scene between Mr. and Mrs. Park that happens just a few feet away from the hiding Kims is made funnier first by the wife’s mewling, then by the bougie couple, in matching pajama sets, getting turned on by role-playing as their former driver and his imagined lover. (After baselessly speculating that their ex-employee must’ve been on cocaine or meth to bonk in the back seat, Mrs. Park, as part of their lovemaking game, moans, “Buy me drugs!”) But the film’s most daring gag occurs several minutes earlier, when Mrs. Kim makes a crack at her husband’s expense in front of their kids, and he grabs her shirt, threatening violence. Their children talk him down, and the couple dissolve into almost simultaneous giggles. The mere idea of spousal abuse—an epidemic in South Korea—is laughable between this pair. Their egalitarianism, however roguishly expressed, jars with the mutually discomfiting inequity that exists between the Parks, which causes the wealthy housewife to live in fear of the flimsiness of her position, and her husband to have to tell himself that he’s in love with a woman he doesn’t seem to respect.

B ong found the one actor who could match his virtuosic elasticity two decades ago, near the start of his career. Song Kang Ho—whose first film with Bong was Memories of Murder, in which he plays a provincial detective—has since starred in the majority of the director’s films, always in common-man roles that undermine traditional masculine authority without sacrificing the characters’ dignity. In Parasite, he plays his darkest Bong character—the Kim family member least able to muster up sympathy for the bunker couple, and the one who ends up taking their place.

One of the most pivotal scenes in Parasite is also its most unassuming. At a school gymnasium, amid dozens of other people rendered homeless by a flood, the two Kim men speak quietly on their cots. Ki-woo asks his father what he plans to do about Moon-gwang and her husband, whom the Kims have left behind, gravely injured or tied up, to die. Seeing an opportunity to impart a life lesson to his devoted son, Mr. Kim embarks on a gallingly nihilistic monologue, informing his firstborn that “none of it fucking matters.” He places his forearm across his face, as if to keep his eyes from seeing the consequences of his decisions. It’s the film’s most pointed accusation of moral complacency on the part of the Kims, though that was previously suggested in their (hilarious) inability to acknowledge their con artistry as such. And yet the anger-tinged world-weariness that Song endows his character with thoroughly humanizes Mr. Kim’s refusal to give up any of the hard-won gains he and his family have made within the Park household. His impassivity betrays his determination to keep his position, no matter the cost.

If genre blueprints make certain story beats feel predestined, Bong’s unique gift lies in making the prediction-defying swerves in his films feel like new inevitabilities. That’s never truer than in his continued reimagining of the cinematic underdog. Parasite is clear-eyed about the illusions that inequality needs in order to perpetuate itself, and about the many systems that shield one-percenters like the Parks from having to get their own hands dirty while engaged in the project of oppression. But it also reveals the Kims, as sympathetic and unfairly treated as they are, as utterly capable of the banality of evil, in part because of their own overidentification with underdogs, and the inherent goodness they assume they can lay claim to. The layers of self-deception build on top of one another until, finally, it all comes crashing down.

More: Essays

Mother: Look, Ma, No Therapist!

Albert Brooks and Debbie Reynolds are at their comedic best in this tale of parent-child bonding filled with Oedipal humor and emotional insight.

By Carrie Rickey

Real Life: A Young, Honest Guy Like Himself

A brilliant satire, inspired by a 1973 PBS documentary series that gave rise to the reality-television genre, Albert Brooks’s first feature film examines the ethical dilemmas of combining cheap entertainment and sociological experiment.

By A. S. Hamrah

Not a Pretty Picture: An Act of Reckoning

In her formally daring debut feature, Martha Coolidge stages a confrontation with the subject of date rape that questions the kind of “closure” required in conventional storytelling.

By Molly Haskell

Two Films by Kira Muratova: Restless Moments

In films that elude categorization, the Ukrainian director developed a boldly experimental aesthetic that evokes her mercurial inner dialogue and the leaps and stutters of her imagination.

By Jessica Kiang

You have no items in your shopping cart

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Movie Reviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

'Parasite' Hooks You With Its Emotional Power And Extraordinary Cunning

Justin Chang

Lee Sun-kyun and Cho Yeo-jeong play Mr. and Mrs. Park, a wealthy couple whose hired help isn't quite what it seems, in Bong Joon-ho's thriller Parasite . Courtesy of NEON CJ Entertainment hide caption

Lee Sun-kyun and Cho Yeo-jeong play Mr. and Mrs. Park, a wealthy couple whose hired help isn't quite what it seems, in Bong Joon-ho's thriller Parasite .

I was fortunate enough to go into Parasite knowing almost nothing about it. Bong Joon-ho's brilliant new movie packs the kinds of stunning, multi-layered surprises that deserve to be experienced as fresh as possible. I'll tread as cautiously as I can, but suffice to say that Parasite is a darkly comic thriller about two families: the Parks, who are very rich, and the Kims, who are very poor.

Mr. and Mrs. Kim live with their son, Ki-woo, and their daughter, Ki-jung, in a cramped apartment in Seoul. Years of poverty have made them shrewd, resilient and tough — and not above the occasional petty theft. Like the family in last year's great Japanese drama Shoplifters , they've managed to survive by relying on their wits and on each other.

One day Ki-woo, a high-school graduate, gets a job as an English tutor for an upper-class teenage girl named Da-hye. Her father, Mr. Park, is a millionaire tech titan, and they live in a gated modernist fortress of a house designed by a famous architect.

Ki-woo begins visiting the house to give his English lessons, and it's there that he meets Mrs. Park, who lets slip that she's looking for an art teacher for her mischief-making young son. Thinking fast, Ki-woo mentions a distant acquaintance who might be good for the job — and within days, his sister Ki-jung has been hired as a very expensive tutor.

The Kims enjoy their sudden boost in income, even as they strain to keep the Parks in the dark about their family connection and their lack of proper credentials. But the lies don't end there, and their scheme grows only more dangerous in its ambition.

For roughly its first hour, Parasite is the most deviously entertaining con-artist thriller I've seen in years. Director Bong pulls the pieces together with the elegance and flair of a conductor attacking a great symphony. Inch by inch, the Kims expand their domain. No piece of information, whether it's the matter of the housekeeper's allergy or the sexual habits of Mr. Park's driver, is too trivial to be used to their advantage.

From Korea, A Thriller Hitchcock Would Admire

Bong Joon-Ho's 'Okja' Is As Weird A Hybrid As Its Porcine Star

Bong draws us into a wicked sense of complicity with the Kims, who, for all their duplicity, are never hard to root for. But as fun as it is to see the Parks get hoodwinked, Bong doesn't turn them into easy villains. We see how gullible and vulnerable they are behind their bolted doors and high-tech security system. We see the cracks in their perfect-family facade: The actress Cho Yeo-jeong gives an especially nuanced performance as Mrs. Park, who, for all her breezy entitlement, lives in the shadow of her cold, unfeeling husband.

The Kims, by contrast, are a model of intimacy and fairness: When money and space are this tight, everyone has to pull their weight. They depend on each other so completely that they seem to function less like individuals than like a single organism. Maybe that makes them the "parasite" of the title, or maybe not. As the movie races toward a suspenseful and terrifying conclusion, it leaves little doubt as to whether the haves or the have-nots represent the greater scourge in a capitalist society.

Bong has always been deft at synthesizing thrills and politics. He previously tackled class warfare in his English-language thriller Snowpiercer , but Parasite feels even more closely related to his wonderful 2006 monster movie The Host , which also followed a desperate family trying to survive. The star of The Host was the popular actor Song Kang-ho, who returns in Parasite as Mr. Kim and gradually becomes the movie's angry moral center. More than his wife or kids, he understands what it means to be looked down on by people like the Parks and regarded as less than human.

At first you're right there with the Kims, until the story takes the first of many jaw-dropping turns. Parasite is seamless in the way it shuffles moods, tones and genres, and downright Hitchcockian in the way it manipulates your sympathies. It's a movie of extraordinary cunning and devastating emotional power, and after three viewings I'm still not sure quite how to classify it. Is it a comedy or a tragedy, a thriller or a satire, an art film or a popular entertainment? Maybe it's best to simply call it what it is: a masterpiece.

Correction Oct. 24, 2019

An earlier photo caption misstated Lee Sun-kyun's name as Sun Kyun-lee.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How “Parasite” Falls Short of Greatness

Of the two current movies in which a young man who has been severely harmed by the inequalities of money and power preys upon the wealthy, looks nihilistically at the social order, turns to violence, and is given to fits of compulsive laughter, the Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s “ Parasite ” is by far the better one, but the contrast between that film and “ Joker ” is nonetheless revealing. “Joker” takes off from a facile premise and descends into incoherent political trolling as a result of scattershot plotting and antics—its director, Todd Phillips, appears not to see what he’s doing. Bong, by contrast, is a far more skillful and thoughtful filmmaker. He has a very clear purpose, sees exactly what he’s doing, and does it with a directness that is itself deadening: his messaging is so on point, his rhetoric so rigid, that there’s hardly anything left untethered to allow the viewer imaginative freedom.

“Parasite” seems, for the most part, to fulfill Bong’s strong and admirable intentions. It conveys the sense that he made the movie with the desire, the will, to show something that he has in mind, that troubles him, and that ought to trouble viewers—and to show it in a form that’s sufficiently entertaining, sufficiently within the standards and codes of genre films, that significant numbers of viewers will trouble themselves to see it and make note of what they’ve seen. “Parasite” is a satirically comedic thriller about poverty, about the contrast between the rich and the poor, about the injustice of inequality, that avoids the conventions and habits of realistic social dramas. The settings are crucial to the movie. Bong wants to show specific places that stand in for many others of the same sort. One is a cramped, substandard, subterranean “semi-basement” apartment in which a poor family of four lives, at the end of a dead end, where they’re vulnerable both to social and environmental hazards. He contrasts that with a rich and frivolous family’s lavish, well-protected, spacious, comfortable, architecturally distinguished and aesthetically pleasing villa that, nonetheless, conceals and symbolizes the agony of the deprived and the despised.

The despairing young man, Kim Ki-woo, lives in the tiny semi-basement apartment, which yields a ground-level view of the street from a ceiling-high window. He lives with his sister, Ki-jung, a talented graphic artist; his father, Ki-taek, an out-of-work driver; and his mother, Chung-sook, a former star of track and field. The four members of the Kim family are all unemployed; their search for work is further thwarted when a neighbor slaps a password on the Wi-Fi that they’ve been piggybacking on. A piecework job folding pizza boxes comes to nought; then Ki-woo’s friend Min, a college student, comes to the rescue. Min is tutoring a high-school student who’s the daughter of the wealthy Park family, but he’s leaving, to study in the United States. He offers the part-time gig to Ki-woo, who wanted to go to college, too, but couldn’t pass the rigorous entrance exams—because, it’s said, he was too busy working.

Ki-jung, a talented artist, goes to an Internet café and forges university certificates for Ki-woo, who’s hired by the Park family—the father, Dong-ik (who also calls himself Nathan), is the head of a software company; the mother, Yeon-kyo, doesn’t work outside the home—to teach the girl, Da-hye, who’s fifteen. Min has an incipient romance with her, and hopes to marry her. But Ki-woo—who is introduced to the Americanophilic household as Kevin—lets a mutual flirtation develop, and himself imagines ultimately marrying her and moving into the lavish home. Meanwhile, Ki-woo sees an opening: the Parks’ young son, Da-song, has emotional issues, and Ki-woo recommends his sister—passing her off as a friend—as an art teacher. Once she arrives (under the name of Jessica and the guise of a onetime student in the United States), she sees another opening: she contrives to get Nathan’s chauffeur fired and her father (also presented as a friend) hired in his stead; then the three Kims manage to get the Parks’ live-in housekeeper, Moon-kwang, fired and replaced by their mother, Chung-sook. The Kims more or less take over the Park household—in the process, exposing underlying tensions and unresolved conflicts that lead to violence of a Grand Guignol extravagance.

The chaotic “Joker” feeds red meat to conflicting strains of political tantrum-throwers, from Bernie bros (by exulting in violence against the rich) to the alt-right (by exulting in a mainstream-media figure being shot in the head), and to critics who mistake such button-pushing for seriousness. “Parasite,” by contrast, is consistent, all too consistent; it focusses its messaging to wreak a devastating twist on a dark truth of capitalism. Where the nineteenth-century robber baron Jay Gould infamously said “I can hire one half of the working class to kill the other half,” Bong suggests, in his whiplash-sardonic satire, that by hiring only one half of the working class, the rich are already in effect killing the other half—that, in the very search for work, the working class can be relied on to kill each other unbidden. The subject of the film is the nexus of unemployment, of gross inequality of opportunity, and of a system of competition that is designed to be fiercest at the bottom, where those with the least also have the strongest incentive to claw against each other in a struggle for survival.

In “Parasite,” Bong dramatizes, with genre-contrived antics, the daily indignities to which the poor are subjected—cut off from digital society as if from society at large, deprived of educational opportunities by a pseudo-meritocracy that rewards the lavishly tutored, dilapidated surroundings that others think they can both metaphorically and literally piss on, unmaintained infrastructure that leaves them most cruelly vulnerable to the elements and to crises of sanitation and hygiene. He contrasts their lives with those of the rich, whose money buys elaborate defenses against a wide range of dangers, whose leisure and surfeit of wealth enables them both to devote outsized attention to frivolities and comforts while also indulging their children’s whims and idiosyncrasies to the point of stunting them—creating a new generation of the warped, the undeserving, and the incompetent to lord over a new generation of embittered and marginalized strugglers.

It’s precisely this plugged-in sense of spot-on messaging and calculated talking points, aimed at critics and viewers who share this clearly defined perspective, that makes “Parasite,” for all its cleverness, the art-house equivalent of the fan service delivered by studios to devotees of franchises. Which is to say that the action, alternating between surprising twists and blatant affirmations, is filled with shovelled-in details that, despite apparent peculiarity and singularity, link up all too perfectly—that are seemingly dropped in solely for the purpose of creating a plot point later on in the film. (A decorative stone that is seen in the first act will surely go off in the third.) “Parasite” is scripted to the vanishing point: for all the desire to show, its images are more like realizations of a plot point or a premise than events themselves.

In this regard, “Parasite” makes for an unfortunate contrast with the great satirical political comedies, whether classic or recent—whether any one of many films by Charlie Chaplin or Jacques Tati or Vera Chytilová, whether Spike Lee’s “ Chi-Raq ” or Jim Jarmusch’s “ The Dead Don’t Die ,” Jordan Peele’s “ Us ,” Boots Riley’s “ Sorry to Bother You ,” Maya Vitkova’s “ Viktoria ,” or Jia Zhangke’s short film “ The Hedonists ”: these films offer a radical sense of materiality, making their exaggerations and contrivances continuous with experience outside the screen. With “Parasite,” the machinery is composed in the script, and what’s filmed is so stringently and narrowly subordinated to realizing those plans—and doing so in a way that’s both designed to reach its audience and that weirdly undercuts the movie’s own tone and design.

On the other hand, “Parasite” offers a twist that’s too good to mention or even to hint at. Suffice it to say that the movie takes off in a direction that’s a shock of narrative inventiveness when it’s first introduced—and that also gets drawn into the movie’s plot mechanism and schematically illustrative direction in a way that undercuts its shock, even as it ramps up the dramatic tension. What’s more, “Parasite” admirably tweaks one of its crucial genre elements, a casually revealed yet significant imagining of a ghost. That spectral conceit has a strong emotional effect on one of the movie’s characters and turns out to have a basis not in the metaphysical realm but in the economic one.

The film is an elegantly realized movie that virtually flaunts its production values, its suave sophistication, its simultaneous knowingness regarding its own messages and its own techniques. Its characters lack density and substance because their traits melt into an unexceptional blandness except when they stand out for derision. There’s a ground state of simple normalcy, free of culture and free of substance and free of ideas, as if personality itself were a luxury; it’s the sort of benign condescension that working-class characters often receive in far worse films than “Parasite,” and that, no less than its elegant and creamy aesthetic, flatters the sophistication of its art-house audience. So, for that matter, does the underlying order that, despite the film’s obvious sympathies and valuable insights, Bong approaches with restraint and leaves largely unchallenged. “Parasite” is essentially a conservative movie, looking with bitter dismay at an order that falls short, a sense of law and of social organization that functions efficiently but misguidedly—that needs, in effect, more and better order.

“Parasite” is far from a comprehensive or complete vision of South Korean society or even of modern capitalism in its over-all social and cultural sense. Rather, it’s a well-tuned mechanism for an ultimately modest and moderate lament, a reasonable filmmaker’s flirtation with extreme modes of expression and emotion that, nonetheless, relentlessly pull back to a moderate norm. It’s neither nihilistic nor utopian, neither revolutionary nor visionary; it wishes and shrugs. For the strength of its concepts and the bravado of its narrative ingenuity, “Parasite” is a good movie—in both senses of the word, both artistically and morally. Where it falls far short of greatness is its inability to contend with society and existence at large—or with its own conservative aesthetic; it doesn’t risk disrupting its own schema in pursuit of more drastic experiences and ideas. As for the young man’s compulsive laughter, it, too, remains incidental and undeveloped; that’s the only thing that “Joker” does better.

Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Movie Review — “Parasite” Movie Review: A Cinematic Masterpiece

"Parasite" Movie Review: a Cinematic Masterpiece

- Categories: Film Analysis Movie Review

About this sample

Words: 768 |

Published: Sep 12, 2023

Words: 768 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

An unforgettable narrative, social commentary at its finest, a global cinematic impact.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 423 words

3 pages / 1360 words

5 pages / 2478 words

3.5 pages / 1685 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Movie Review

Dope, directed by Rick Famuyiwa and released in 2015, is a film that defies convention and takes its audience on a thrilling and thought-provoking cinematic journey. In this movie essay, we will delve into the film's exploration [...]

The Avengers movies are one of the longest and best running movies to ever be put out. Year after year people are expecting a bigger and better movie than the one before it. The movie I will be reviewing is Avengers Endgame. [...]

Crafton, D. (1999). The talkies: American cinema's transition to sound, 1926-1931. University of California Press.Koszarski, R. (2009). An evening's entertainment: The age of the silent feature picture, 1915-1928. University of [...]

Something the Lord Made is a thought-provoking film that chronicles the true story of two medical pioneers, Dr. Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas, and their groundbreaking work in the field of cardiac surgery. Set against the [...]

Gray argues that the definition of a superheroine’s “hotness” is “the establishment of a delicate balance of both sex appeal and physical strength” (Gray 91). This definition is applicable to the superheroine Black Widow in the [...]

Sylvester Stallone’s “Rocky” is universally regarded as a classic film. Winning multiple Oscars, launching the acting career of Stallone himself (perhaps not the best consequence in the long run…), and inspiring several people [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

‘Parasite’ Ending Explained: You Can’t Go Wrong With No Plans

Your changes have been saved

Email is sent

Email has already been sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

The Big Picture

- Parasite explores greed and class divides, showcasing the clash between the wealthy Park family and the struggling Kim family.

- The film's shocking twist reveals a hidden man living in the Park family's basement, leading to chaos and bloodshed.

- Parasite offers a bleak and realistic ending, highlighting the idea of wealth as a prison and economic immobility as the new norm.

Bong Joon-ho ’s masterful Academy Award winner, Parasite , is a brutal satire about wealth disparity and the lengths we're willing to go to for family. One of only three movies to win both the Best Picture Oscar and the Palme d'Or , Parasite shifts from a biting dramedy to a suspenseful thriller in its second act, proving Joon-ho's affinity for humor, horror, and everything in between. Set in Seoul, South Korea, the movie follows the Kim family, who work low-income jobs and struggle to make ends meet. When son Ki-Woo ( Choi Woo-shik ) secures a gig tutoring the wealthy Park family's young daughter ( Jung Ji-so ), the Kims slowly begin to infiltrate the home, enjoying the unfamiliar luxuries afforded to the Parks. However, when the Parks' idyllic lifestyle proves to house a disturbing secret , chaos and bloodshed ensue, and we're left wondering who the parasites really are. So, how does Parasite end, and what does it mean?

Greed and class discrimination threatens the newly formed symbiotic relationship between the wealthy Park family and the destitute Kim clan.

What Is 'Parasite' About?

In Parasite , the Kim family's quest to overtake the Parks' home is no simple feat, and they do so by slyly getting the Parks to hire them without realizing that they're all related. Once Ki-woo gets his foot in the door by becoming Da-hye's tutor — with a certificate forged by his clever sister, Ki-jung ( Park So-dam ) — the pieces begin to fall strategically into place. Ki-woo uses his standing to introduce Ki-jung to the Parks, with her posing as a sought-after art therapist. Mr. and Mrs. Park ( Lee Sun-kyun and Cho Yeo-jeong ) quickly hire Ki-jung to help their young son, Da-song (Jung Hyeon-jun), who has recently been traumatized after seeing a "ghost" in their kitchen.

The Kim kids then frame the Parks’ driver for being a creep, which allows them to bring in their own father, Ki-taek ( Song Kang-ho ), for the job. Finally, the Parks let go of their longtime housekeeper, Moon-gwang ( Lee Jung-eun ), after Ki-jung exploits Moon-gwang's peach allergy to make it look like she has tuberculosis, paving the way for the Kims’ mother, Chung-sook ( Jang Hye-jin ), to get the gig. The Parks don’t learn that the Kims are related , and the Kims enjoy their time in the Park house, particularly when the wealthy family leaves for a trip.

Who Is the Man in the Basement in 'Parasite?'

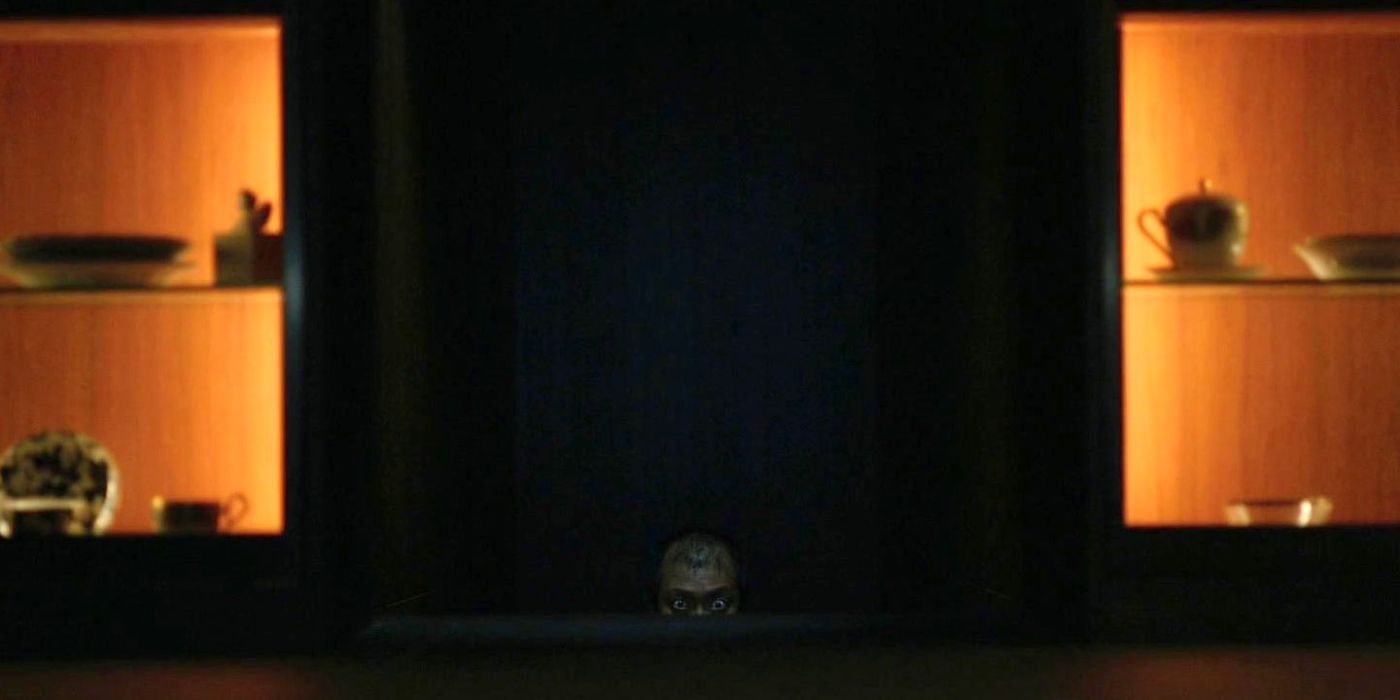

Everything seems to be going fine until Moon-gwang returns to the house, claiming to have left something behind. In Parasite 's iconic, shocking twist , said "something" turns out to be Moon-gwang's husband, Geun-se (Park Myung-hoon), who, unbeknownst to the Parks, is living in a secret bunker in the basement , and is revealed to be the "ghost" that Da-Song saw one night when he was sneaking into the kitchen for food.

When the Kims threaten to expose and expel Geun-se, Moon-gwang in turn threatens to expose their familial status to the Parks, which she learns of after hearing them talk to one another. For a while, Moon-gwang and Geun-se get to live the high life until they are overpowered by the Kims, leading to an altercation that leaves Moon-gwang dead and Geun-se once again left in the basement. The Parks return early from their trip due to a storm, so the Kims are forced to leave and sleep in a gymnasium because their basement apartment has been flooded.

What Happens to the Family in 'Parasite'?