Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.3 Causation and Harm

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between factual and legal cause.

- Define intervening superseding cause, and explain the role it plays in the defendant’s criminal liability.

- Define one and three years and a day rules.

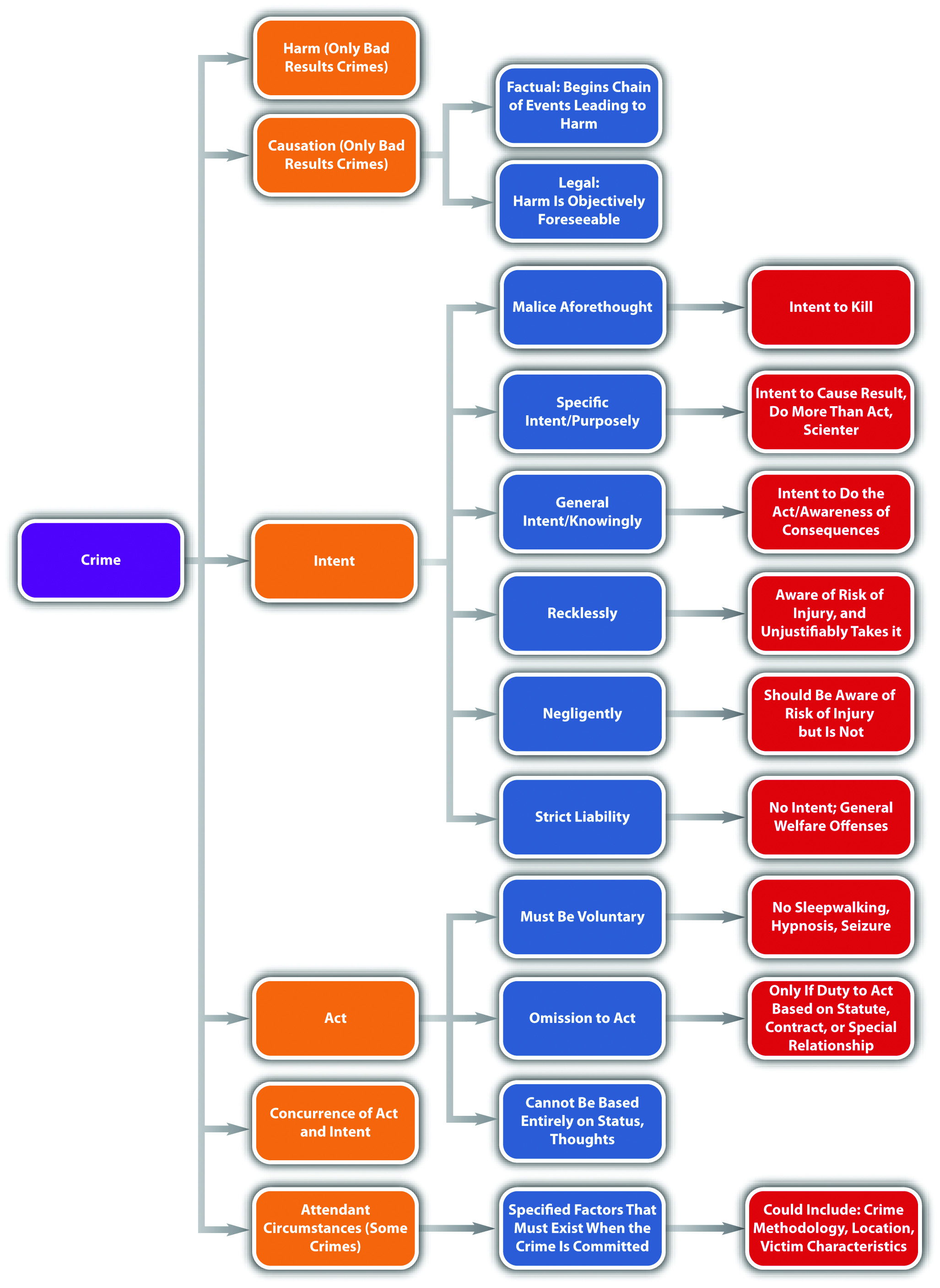

As stated previously, causation and harm can also be elements of a criminal offense if the offense requires a bad result. In essence, if injury is required under the statute, or the case is in a jurisdiction that allows for common-law crimes, the defendant must cause the requisite harm . Many incidents occur when the defendant technically initiates circumstances that result in harm, but it would be unjust to hold the defendant criminally responsible. Thus causation should not be rigidly determined in every instance, and the trier of fact must perform an analysis that promotes fairness. In this section, causation in fact and legal causation are examined as well as situations where the defendant may be insulated from criminal responsibility.

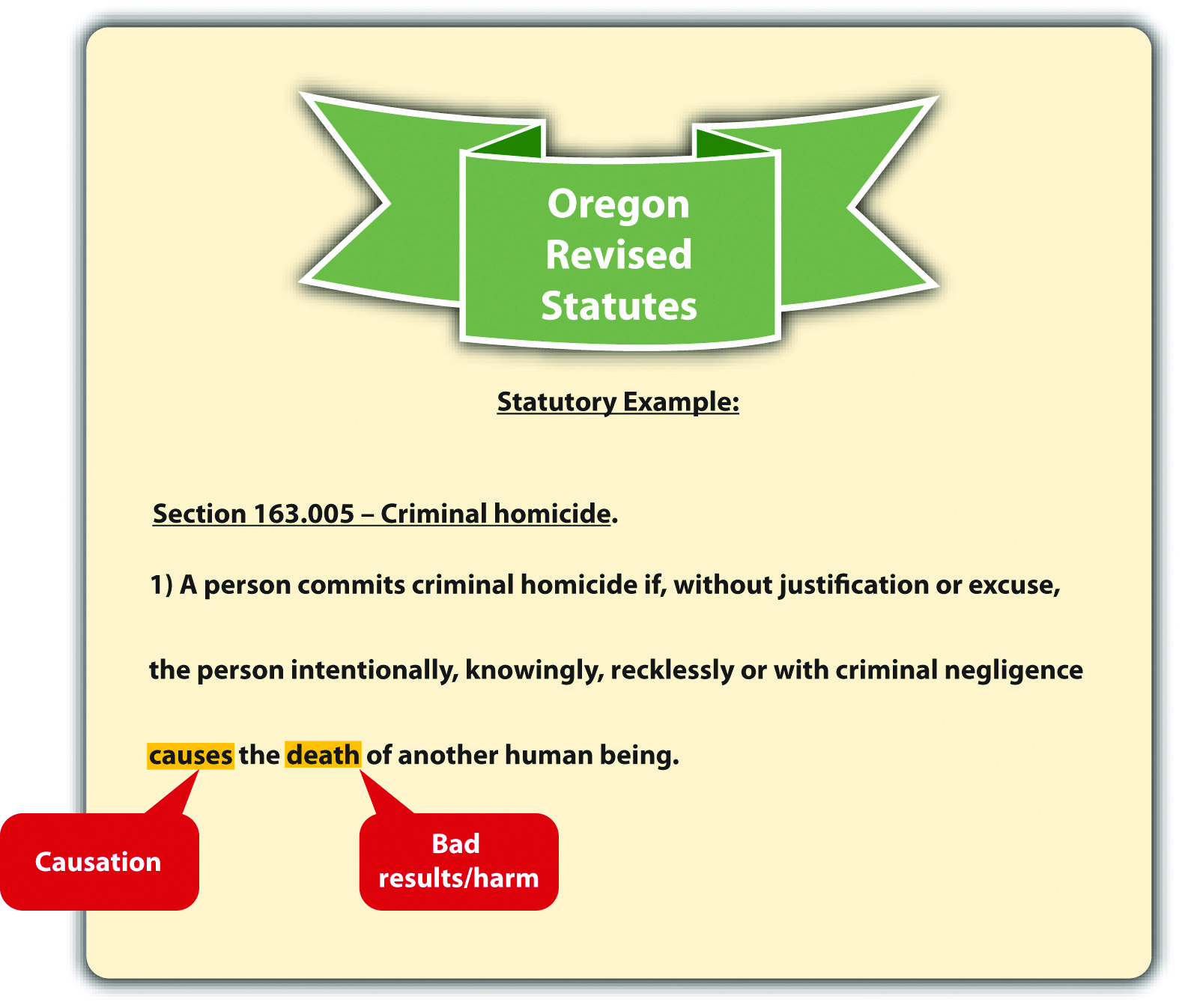

Figure 4.9 Oregon Revised Statutes

Causation in Fact

Every causation analysis is twofold. First, the defendant must be the factual or but for cause of the victim’s harm. The but for term comes from this phrase: “but for the defendant’s act, the harm would not have occurred” (Del. Code Ann. tit. II, 2011). As the Model Penal Code states, “[c]onduct is the cause of a result when…(a) it is an antecedent but for which the result in question would not have occurred” (Model Penal Code § 2.03(1)(a)). Basically, the defendant is the factual or but for cause of the victim’s harm if the defendant’s act starts the chain of events that leads to the eventual result.

Example of Factual Cause

Henry and Mary get into an argument over their child custody agreement. Henry gives Mary a hard shove. Mary staggers backward, is struck by lightning, and dies instantly. In this example, Henry’s act forced Mary to move into the area where the lighting happened to strike. However, it would be unjust to punish Henry for Mary’s death in this case because Henry could not have imagined the eventual result. Thus although Henry is the factual or but for cause of Mary’s death, he is probably not the legal cause .

Legal Causation

It is the second part of the analysis that ensures fairness in the application of the causation element. The defendant must also be the legal or proximate cause of the harm. Proximate means “near,” so the defendant’s conduct must be closely related to the harm it engenders. As the Model Penal Code states, the actual result cannot be “too remote or accidental in its occurrence to have a [just] bearing on the actor’s liability” (Model Penal Code § 2.03 (2) (b)).

The test for legal causation is objective foreseeability (California Criminal Jury Instructions No. 520, 2011). The trier of fact must be convinced that when the defendant acted, a reasonable person could have foreseen or predicted that the end result would occur. In the example given in Section 4 “Example of Factual Cause” , Henry is not the legal cause of Mary’s death because a reasonable person could have neither foreseen nor predicted that a shove would push Mary into a spot where lightning was about to strike.

The Model Penal Code adjusts the legal causation foreseeability requirement depending on whether the defendant acted purposely, knowingly, recklessly, or negligently. If the defendant’s behavior is reckless or negligent, the legal causation foreseeability requirement is analyzed based on the risk of harm, rather than the purpose of the defendant.

Example of Legal Causation

Imagine that Henry and Mary get into the same argument over their child custody agreement, but this time they are in their garage, which is crowded with furniture. Henry gives Mary a hard shove, even though she is standing directly in front of a large entertainment center filled with books and a heavy thirty-two-inch television set. Mary staggers backward into the entertainment center and it crashes down on top of her, killing her. In this situation, Henry is the factual cause of Mary’s death because he started the chain of events that led to her death with his push. In addition, it is foreseeable that Mary might suffer a serious injury or death when shoved directly into a large and heavy piece of furniture. Thus in this example, Henry could be the factual and legal cause of Mary’s death. It is up to the trier of fact to make this determination based on an assessment of objective foreseeability and the attendant circumstances.

Intervening Superseding Cause

Another situation where the defendant is the factual but not the legal cause of the requisite harm is when something or someone interrupts the chain of events started by the defendant. This is called an intervening superseding cause . Typically, an intervening superseding cause cuts the defendant off from criminal liability because it is much closer, or proximate , to the resulting harm (Connecticut Jury Instructions No. 2.6-1, 2011). If an intervening superseding cause is a different individual acting with criminal intent, the intervening individual is criminally responsible for the harm caused.

Example of an Intervening Superseding Cause

Review the example with Henry and Mary in Section 4 “Example of Legal Causation” . Change the example so that Henry pulls out a knife and chases Mary out of the garage. Mary escapes Henry and hides in an abandoned shed. Half an hour later, Wes, a homeless man living in the shed, returns from a day of panhandling. When he discovers Mary in the shed, he kills her and steals her money and jewelry. In this case, Henry is still the factual cause of Mary’s death, because he chased her into the shed where she was eventually killed. However, Wes is probably the intervening superseding cause of Mary’s death because he interrupted the chain of events started by Henry. Thus Wes is subject to prosecution for Mary’s death, and Henry may be prosecuted only for assault with a deadly weapon.

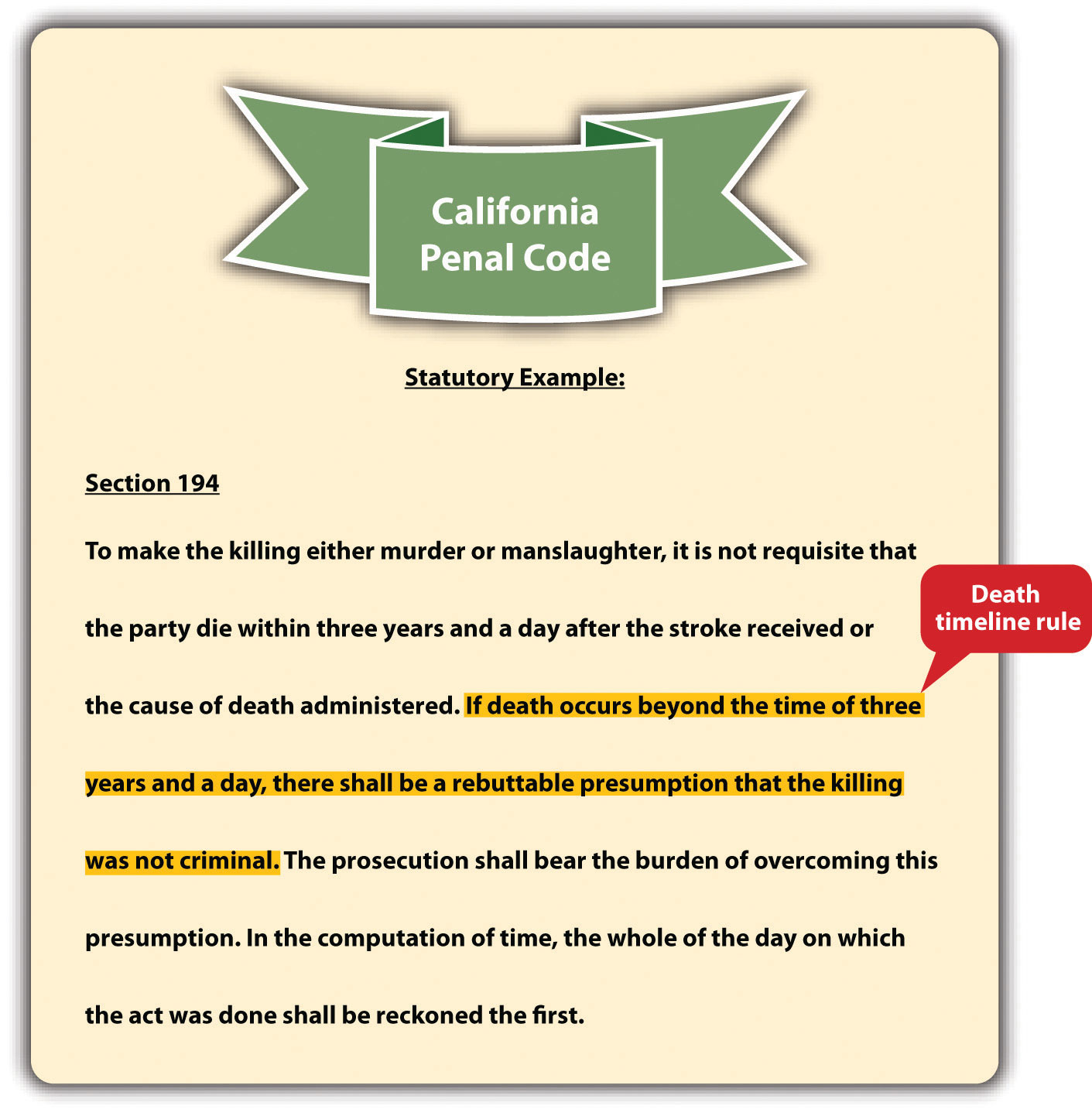

One and Three Years and a Day Rules

In criminal homicide cases, the causation analysis could be complicated by a victim’s survival for an extended time period. Because of modern technology, victims often stay alive on machines for many years after they have been harmed. However, it may be unreasonable to hold a defendant responsible for a death that occurs several years after the defendant’s criminal act. A few states have rules that solve this dilemma.

Some states have either a one year and a day rule or a three years and a day rule (S.C. Code Ann., 2011). These rules create a timeline for the victim’s death that changes the causation analysis in a criminal homicide case. Under one or three years and a day rules, the victim of a criminal homicide must die within the specified time limits for the defendant to be criminally responsible. If the victim does not die within the time limits, the defendant may be charged with attempted murder , rather than criminal homicide. California makes the timeline a rebuttable presumption that can be overcome with evidence proving that the conduct was criminal and the defendant should still be convicted (Cal. Penal Code, 2011).

Figure 4.10 California Penal Code

Death timeline rules are often embodied in a state’s common law and have lost popularity in recent years (Key v. State, 2011). Thus many states have abolished arbitrary time limits for the victim’s death in favor of ordinary principles of legal causation (Rogers v. Tennessee, 2011). Death timeline rules are not to be confused with the statute of limitations , which is the time limit the government has to prosecute a criminal defendant.

Figure 4.11 Diagram of the Elements of a Crime

Key Takeaways

- Factual cause means that the defendant starts the chain of events leading to the harm. Legal cause means that the defendant is held criminally responsible for the harm because the harm is a foreseeable result of the defendant’s criminal act.

- An intervening superseding cause breaks the chain of events started by the defendant’s act and cuts the defendant off from criminal responsibility.

- One and three years and a day rules create a timeline for the victim’s death in a criminal homicide.

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Phillipa sees Fred picking up trash along the highway and decides she wants to frighten him. She drives a quarter of a mile ahead of Fred and parks her car. She then hides in the bushes and waits for Fred to show up. When Fred gets close enough, she jumps out of the bushes screaming. Frightened, Fred drops his trash bag and runs into the middle of the highway where he is struck by a vehicle and killed. Is Phillipa’s act the legal cause of Fred’s death? Why or why not?

- Read Bullock v. State , 775 A.2d. 1043 (2001). In Bullock , the defendant was convicted of manslaughter based on a vehicle collision that occurred when his vehicle hit the victim’s vehicle in an intersection. The defendant was under the influence of alcohol and traveling thirty miles per hour over the speed limit. The victim was in the intersection unlawfully because the light was red. The defendant claimed that the victim was the intervening superseding cause of her own death. Did the Supreme Court of Delaware agree? The case is available at this link: http://caselaw.findlaw.com/de-supreme-court/1137701.html .

- Read Commonwealth v. Casanova , 429 Mass. 293 (1999). In Casanova , the defendant shot the victim in 1991, paralyzing him. The defendant was convicted of assault with intent to murder and two firearms offenses. In 1996, the victim died. The defendant was thereafter indicted for his murder. Massachusetts had abolished the year and a day rule in 1980. Did the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court uphold the indictment, or did the court establish a new death timeline rule? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=16055857562232849296&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr .

Cal. Penal Code § 194, accessed February 14, 2011, http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/cacode/PEN/3/1/8/1/s194 .

California Criminal Jury Instructions No. 520, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.justia.com/criminal/docs/calcrim/500/520.html .

Connecticut Jury Instructions No. 2.6-1, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.jud.ct.gov/ji/criminal/part2/2.6-1.htm .

Del. Code Ann. tit. II, § 261, accessed February 14, 2011, http://delcode.delaware.gov/title11/c002/index.shtml#261 .

Key v. State , 890 So.2d 1043 (2002), accessed February 15, 2011, http://www.lexisone.com/lx1/caselaw/freecaselaw?action= OCLGetCaseDetail&format=FULL&sourceID=beehed&searchTerm= efiQ.QLea.aadj.eaOS&searchFlag=y&l1loc=FCLOW .

Rogers v. Tennessee , 532 U.S. 541 (2001), accessed February 14, 2011, http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=000&invol=99-6218 .

S.C. Code Ann. § 56-5-2910, accessed February 15, 2011, http://www.scstatehouse.gov/code/t56c005.htm .

Criminal Law Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Causation, Fault, and Fairness in the Criminal Law

Over the past two decades, the Supreme Court of Canada has developed an overarching account of causation rooted in the need to prevent the conviction of the morally innocent. Despite these valuable contributions, there are certain limitations to the way causation is currently conceptualized in Canadian criminal law. This article aims to address those limitations and offer a plausible alternative account of causation and its underlying rationale. It advances three core arguments. First, it explains why judges should employ one uniform formulation of the factual causation standard: significant contributing cause. Second, it offers a new account of legal causation that distinguishes foreseeability as part of the actus reus from foreseeability inherent to mens rea. In doing so, it sets out why legal causation is primarily concerned with fairly ascribing ambits of risk to individuals. Third, it refutes the Supreme Court of Canada’s underlying justification for the causation requirement. Contrary to the Court’s invocation of the importance of moral innocence, this article demonstrates that causation principles actually tend to concede the accused’s moral fault while still providing reasons for withholding blame for a given consequence. This reveals that causation’s underlying rationale is more closely related to concerns about fair attribution rather than moral innocence. Ultimately, this article reframes causation to better answer one of the most basic questions in the criminal law: Why am I being blamed for this?

Au cours des deux dernières décennies, la Cour suprême du Canada a élaboré une explication générale de la causalité ancrée dans la nécessité d’éviter la condamnation de personnes moralement innocentes. Malgré ces contributions importantes, il existe certaines limites à la façon dont la causalité est présentement conceptualisée en droit criminel canadien. Cet article aborde ces limites et propose une alternative plausible pour expliquer la causalité et sa justification sous-jacente. Il met de l’avant trois arguments principaux. Premièrement, il explique pourquoi les juges devraient employer une formulation uniforme de la norme de causalité factuelle : la cause à la contribution significative. Deuxièmement, il propose une nouvelle définition de la causalité juridique qui distingue la prévisibilité faisant partie de l’actus reus de la prévisibilité inhérente à la mens rea. Ce faisant, il expose les raisons pour lesquelles la causalité juridique a pour objet principal d’attribuer équitablement les étendues des risques aux individus. Troisièmement, il réfute la justification sous-jacente à l’exigence de causalité donnée par la Cour suprême du Canada. Contrairement à la Cour, qui invoque l’importance de l’innocence morale, cet article démontre que les principes de causalité tendent en fait à admettre la faute morale de l’accusé tout en fournissant des motifs pour ne pas porter de blâme relativement à une conséquence donnée. Cela révèle que le raisonnement sous-jacent à la causalité est plus étroitement lié aux préoccupations concernant l’aspect équitable de l’attribution du blâme qu’à l’innocence morale de l’accusé. En fin de compte, cet article reformule la causalité pour mieux répondre à l’une des questions les plus fondamentales du droit criminel : pourquoi suis-je tenu responsable de cela?

* Assistant professor, University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law, Civil Law Section. I thank Professors Don Stuart and Graham Mayeda for their comments on prior drafts. I also thank Anna Maria Konewka, Edward Béchard-Torres, Olga Redko, Will Colish, Jessy Héroux, Michelle Biddulph, Hadi Ghobril, Bilal Amani, Nadreyh Vagba, Rayene Bouzitoun, and the anonymous reviewers for helping refine my arguments and commenting on earlier versions of this article. All mistakes are my own. Lastly, I thank the MLJ editorial team for their excellent work that improved this article significantly.

Table of Contents

Introduction.

Suppose that the accused points a gun at the victim and shoots several times. The victim dies immediately. In such contexts, the causal chain between the accused’s conduct and the victim’s death is clear. The accused’s actions contributed to the victim’s death in a physical, medical, or mechanistic sense—the threshold question of factual causation (or cause in fact). [1] That, however, is not the end of the causation inquiry in Canadian criminal law. There must also be legal causation (or cause in law), meaning that it is fair to ascribe the victim’s death to the accused’s conduct—or, in other words, that the accused is morally responsible for the victim’s death. [2]

In other cases, causation is less evident. A third party may attack the victim between the time of the accused’s initial assault and the victim’s death. [3] Some natural cause or event may also play a role in the victim’s death. [4] Third parties may apply some form of negligent care that also contributes to the victim’s death. [5] The victim may die after refusing life-saving care for injuries inflicted by the accused. [6] In all of these cases, some type of intervening event, cause, or act (a novus actus interveniens ) obscures causation. [7]

The causation inquiry is fundamental in the criminal law for a variety of reasons. Intervening acts raise concerns that touch on issues of fair labelling, culpability, and punishment. [8] These concerns are at the forefront when an accused risks being stigmatized for causing an injury or death for which they are not uniquely responsible. [9] Despite the persistence and importance of these issues, courts and scholars correctly point out that causation is notoriously complex and difficult to articulate. [10] It involves the interplay between metaphysical, scientific, moral, and legal considerations. [11]

This article aims to advance a more cogent and clear conception of the causation requirement in Canadian criminal law. Its principal arguments and structure are as follows.

Part I describes the distinction between factual and legal causation as articulated by the Supreme Court of Canada. Building on Jeremy Butt’s recent scholarship, Part II argues that judges should use a uniform formulation of the factual causation standard: significant contributing cause. [12] It also shows why the but-for test is unhelpful except in the easiest of cases. [13] Part II provides the groundwork for this article’s core argument about the role of factual causation—ascribing negative changes in the world to individuals. This Part demonstrates why the significant contributing cause test helps ensure a strong ascriptive link between the defendant’s conduct and its role in worsening others’ plights.

Part III then sets out a plausible account of legal causation’s function as part of a broader causation analysis. It first shows how Canadian criminal law tends to assess an intervening act’s reasonable foreseeability rather than its independence, and how the latter test is subsumed by the former. It then argues that the doctrine of reasonable foreseeability is distinct from the question of foreseeability of bodily harm when assessing moral fault. The doctrine remains useful as an analytical tool to evaluate legal causation, serving to limit criminal liability where unforeseeable contributing causes fall outside the ambit of risk associated with the accused’s initial conduct.

Part IV then challenges the Supreme Court of Canada’s account of the role of factual and legal causation in the criminal law (namely, that they aim to prevent the conviction of morally innocent persons). [14] This Part shows why legal causation can concede the moral culpability of individuals who significantly contribute to the victim’s death, yet withhold blame due to concerns that are rooted in principles of ascription and fair labelling—rationales that are distinct from moral innocence. [15] Ultimately, this article explains why, like other legal doctrines, causation touches on one of the most crucial issues in the criminal law: Who is responsible for what ?

I. Factual and Legal Causation Generally

Causation is a necessary component of the actus reus for result crimes, [16] meaning crimes that are “in part defined by certain consequences which follow an act.” [17] Those results or consequences include death (e.g., for the crimes of manslaughter, criminal negligence causing death, or murder) or bodily harm (e.g., for the offences of assault causing bodily harm or criminal negligence causing bodily harm). [18] The causation component of the actus reus for result crimes is divided into a two-step inquiry. First, there must be factual causation between the accused’s conduct and the consequence. [19] If the first step is satisfied, the second step examines legal causation—whether the accused is morally responsible for the victim’s death. [20]

A. Factual Causation

The Supreme Court of Canada explains that factual causation (or cause in fact) implies the accused’s “medical, mechanical, or physical” contribution to the victim’s injury or death . [21] Cause in fact is a necessary precondition that ties the accused’s conduct to the consequence. [22] While medical expert reports and testimony can assist in establishing factual causation, [23] the trier of fact ultimately determines whether cause in fact is established and is not restricted to a medical expert’s conclusion on that point. [24] In clear cases, the cause in fact inquiry is often framed in counterfactual terms: the victim would not have died or suffered gross bodily harm but for the accused’s contribution to that result. [25]

The Supreme Court of Canada initially explored the requisite degree of factual causation in Smithers . [26] Writing on behalf of the unanimous Court, Justice Dickson (as he then was) concluded that the accused’s conduct must contribute to the victim’s injury or death “outside the de minimis range.” [27] Consistent with the causation test in other countries, it is not necessary that the accused’s act be the sole cause of the victim’s injury or death. [28] The Court also affirmed the longstanding “thin skull principle” applicable in civil and criminal law. [29] According to that principle, causation subsists where the victim had a pre-existing medical condition (e.g., hemophilia, a thin skull, or low bone density) that increased the likelihood of death. [30] The accused thus takes the victim as they find them. [31]

The causation threshold established in Smithers was revisited in R. v. Nette . The Court affirmed that in assessing causation in the criminal law, the concept of contributory negligence does not apply. [32] The majority of the Court also reformulated the terminology for factual causation, holding that the accused’s conduct must be a “significant contributing cause” of the victim’s injury or death. [33] In the Court’s view, it was simpler for triers of fact to understand causation described in positive terms (e.g., a significant contribution) as opposed to in negative terms (e.g., a not insignificant contribution). [34] The majority held that trial judges nonetheless can instruct juries using either formulation—an approach that is criticized below in Part II. [35]

B. Legal Causation

Legal causation (or cause in law) concerns the legitimacy of holding an accused morally responsible for a given result. [36] In contexts where the defendant contributes significantly to the victim’s death and there is no intervening act or event, legal causation is relatively simple. Cause in law is more difficult to ascertain when another event or act also contributes to the victim’s death. Such cases raise concerns about whether it is fair to blame the accused for that result. [37] The second prong of the causation analysis therefore helps ensure that the victim’s injury or death is morally attributable to the actor’s role in producing those consequences. [38]

Both the Criminal Code and the common law provide rules governing legal causation. [39] Certain Criminal Code provisions maintain cause in law despite the acts of a third party or the victim that play some role in the latter’s death. Section 224 establishes that if the defendant injures the victim, causation subsists despite the victim’s failure to resort to proper means that would have prevented their death. [40] Notably, legal causation remains intact where the victim refuses life-saving treatment, for either religious or other reasons. [41] Section 225 affirms legal causation where the victim dies as a result of good faith but inappropriately applied medical care. [42]

The common law rules from the Maybin decision set out two analytical tools that assist courts in determining whether an intervening act undermines cause in law. [43] The first analytical tool assesses whether the general nature of the intervening act and its accompanying risk of harm were reasonably foreseeable at the time of the accused’s initial conduct (“reasonably foreseeable intervening acts”). [44] Where that threshold is met, legal causation is generally maintained. [45] The intervening act’s reasonable foreseeability famously justified maintaining causation in the Supreme Court of South Australia’s decision Hallett . [46] In that case, the accused attacked the victim and left him unconscious on a beach. The tide rose and the victim drowned. The Court held that the rising tide was reasonably foreseeable, and the accused was convicted of manslaughter. [47]

The same test justified maintaining legal causation in the Ontario Court of Appeal decision R. v. Shilon . [48] In that case, an individual stole a motorcycle. A high-speed car chase ensued, involving the stolen motorcycle’s owner (Trakas) and the accused (Shilon), who participated in the motorcycle theft but escaped in another vehicle. While chasing Shilon, Trakas’s car struck and killed a police officer who was laying down a stop-stick. Both Trakas and Shilon were accused of criminal negligence causing death. At issue was whether Trakas’s conduct was an intervening act that undermined Shilon’s responsibility for causing the officer’s demise. [49] The Court upheld Shilon’s conviction, concluding that Trakas’s actions and the risk of harm were reasonably foreseeable consequences of Shilon’s conduct. [50]

The second analytical tool assesses whether the intervening act was independent of the accused’s conduct and deemed to be the sole legal cause of the victim’s death (“independent intervening acts”). [51] Such acts are generally associated with voluntary conduct of a third party or of the victim that also played some role in the latter’s injury or death. [52] Independent acts are said to create new causal chains and sever the accused’s legal responsibility for a given result. [53]

Independent intervening acts imply that the accused’s conduct only set the scene for some other act to cause the victim’s death and therefore was not instrumental in causing it. [54] Where the accused’s actions are merely part of the background, history, or context for the intervening act, the accused is absolved of blame for having caused the relevant result. [55] Where the intervening act is a direct or immediate response to the accused’s actions, the accused is still held responsible in law for that result. [56]

II. Toward a Uniform Formulation for Factual Causation

A. “beyond de minimis” versus “significant contributing cause”.

The Supreme Court of Canada accepts that judges possess discretion with respect to the formulation of the factual causation standard. [57] This Part discusses the problems associated with varying terminology of that standard. It argues that the beyond de minimis test, but-for test, and significant contributing cause test are different and should not be used interchangeably. It then provides reasons why only the “significant contributing cause” formulation should be used in Canadian criminal law.

In the Supreme Court of Canada decision R. v. Nette , Justice Arbour wrote that trial judges are afforded significant latitude in describing the factual causation test. She explained:

As I discussed in Cribbin , while different terminology has been used to explain the applicable standard in Canada, Australia and England, whether the terminology used is “beyond de minimis ”, “significant contribution” or “substantial cause”, the standard of causation which this terminology seeks to articulate, within the context of causation in homicide, is essentially the same. [58]

Some scholars disagree that both formulations for cause in fact—beyond de minimis and significant contributing cause—are interchangeable. Stanley Yeo posits that a not insignificant contribution does not equate to a significant contribution. [59] He remarks: “[W]hen Mary says that she does not dislike John, she means, at most, that she is impartial towards him rather than that she likes him.” [60] Four out of the nine Supreme Court Justices in Nette shared a similar view. They explained: “To claim that something not unimportant is important would be a sophism. Likewise, to consider things that are not dissimilar to be similar would amount to an erroneous interpretation.” [61] Hugues Parent also rejects the equivalency between both standards. In his view, the significant contributing cause standard in Nette is more demanding than the beyond the de minimis range standard in Smithers . [62]

In light of the plausible difference between both formulations for cause in fact, scholars argue against allowing judges to employ different terminology interchangeably. Many criticize the continued use of the beyond the de minimis threshold on the grounds that virtually any contribution by the accused will satisfy the test’s demands. [63] In support of that contention, Jill Presser notes:

[V]irtually all conditions that are precipitating factors of a consequence may be said to be causes. The de minimis threshold is set so low that there is no need to stipulate the requirement of a direct causal relationship between the unlawful act and the proscribed harm. [64]

David Tanovich and James Lockyer agree with that position. In line with certain judicial decisions, they characterize the Smithers causation standard as “sweeping.” [65]

Anne-Marie Boisvert, for her part, contends that one better understands the lax standard set out in Smithers by also considering the range of circumstances that fail to break the causal chain. [66] She points out that the beyond de minimis test not only requires little contribution from the accused to meet that threshold, but dismisses an array (or combination) of relevant contributing circumstances as irrelevant. [67] Those circumstances can include the victim’s pre-existing medical condition, their refusal to receive life-saving care, negligent medical treatment provided by others, and contributory negligence. [68]

For similar reasons, the Law Reform Commission of Canada contended that the but-for and beyond de minimis standards could produce irrational conclusions––for example, that marriage is a cause of divorce. [69] The Commission ultimately argued in favour of a causation test requiring the accused to contribute significantly to the result. [70]

Don Stuart posits that it is plausible that the adoption of the beyond de minimis standard can lead to convictions where the significant contributing cause standard can result in acquittals. [71] He offers the example of the Ontario Court of Appeal decision R. v. Shanks . [72] During a brief altercation, the defendant threw the elderly victim to the ground. The victim, who suffered from a range of pre-existing medical conditions, died later that evening from a heart attack after coronary plaque dislodged and obstructed one of his arteries. Expert evidence revealed that there was an 80–90 per cent chance that the heart attack would have occurred even without the assault. The trial judge still convicted the accused of manslaughter, concluding that he contributed to the victim’s death beyond the de minimis range. [73] The Ontario Court of Appeal upheld the conviction. Don Stuart suggests that the trier of fact may have acquitted the defendant had the significant contributing cause standard been employed. [74]

B. Toward the Uniform Standard of Significant Contributing Cause

There are certain advantages to uniformly employing the significant contributing cause test for factual causation, rather than allowing judges to use different terminology, including “beyond de minimis .” First, the significant contributing cause threshold may promote fair labelling and proportionate stigmatization, especially in cases where the defendant’s contribution to the victim’s death is questionable. [75] For some result crimes other than murder—such as manslaughter or criminal negligence—the defendant risks being stigmatized for causing another’s death. [76] If convicted of those offences, defendants can be sentenced to life imprisonment. [77] The dangers of unfair attribution become particularly prominent in contexts where pre-existing medical conditions or vulnerabilities significantly increase the chance of victims’ suffering injury or death from relatively banal acts. The greater the victim’s vulnerability, the easier it is for the accused’s act to injure the victim or cause their death. Given those risks, the significant contribution test may better protect against unfair attribution of certain results to the accused.

Second, a more demanding causation standard is consistent with other principles that favour fair blaming and punishment practices, such as the principle of lenity (or strict construction) applicable to the statutory interpretation of criminal laws. [78] Strict construction governs the circumstances in which ambiguous criminal law statutes are interpreted in the defendant’s favour. [79] Lenity is not a freestanding principle that automatically applies to penal statutes. [80] Rather, as Glanville Williams explains, it is employed where a penal statute gives rise to more than one reasonable interpretation that is nonetheless consistent with the legislator’s objective. [81] Lenity aims to protect individuals against disproportionate attributions of blame, stigma, or punishment in light of the defendant’s actual culpability. [82] Admittedly, the causation standard is not a statutory creation or an ambiguous penal statute; it is a common law creation. Yet ambiguity about the appropriate causation standard raises the same concern that underpins the lenity principle: fair labelling. Supreme Court judges’ disagreement in Nette as to whether non-insignificance equates to significance exemplifies the type of ambiguity that militates in favour of lenity in other contexts.

Third, the importance of predictability and uniformity in the criminal law supports the adoption of one single formulation for factual causation. If nearly half the Supreme Court judges in Nette perceived a meaningful difference between different formulations of the causation test, it is conceivable that other judges or jury members do as well. [83]

Fourth, the sole use of the significant contributing cause test would standardize the factual causation threshold in cases with and without intervening acts. In Nette , the Supreme Court of Canada held that judges have discretion to determine the formulation of the causation standard. [84] Yet several years later in Maybin , the Court was more explicit about the formulation of the causation standard in the presence of intervening acts: it was significant contributing cause. [85] Canadian courts as well as the England and Wales Court of Appeal (citing Maybin and prior English cases) affirmed that approach in homicide cases, highlighting the need to ensure that the accused’s contribution to the victim’s death is significant. [86] Where causation issues arise, the core question is always the same: whether the accused contributed significantly to the victim’s death in fact and in law. [87] This remains the fundamental question irrespective of some intervening act, where courts militate strongly in favour of the sole formulation of significant contributing cause. For that reason, the causation formulation applicable in contexts of novus actus interveniens should also be used in contexts where there is no intervening act.

C. Limitations to But-For Causation

Factual causation generally involves the counterfactual but-for inquiry: but for the accused’s act, the victim would not be injured or deceased. [88] As reiterated on numerous occasions, the accused’s contribution need not be the predominant, most significant, or most direct cause of death. [89] In many contexts, but-for causation is unhelpful and inevitably requires an assessment of significant contributing cause––a factor that further militates in favour of employing one formulation of the factual causation threshold. [90]

Ernest Weinrib explains that the but-for test is a speculative process that considers “what did not happen or rather what would have happened if what had happened had not happened.” [91] As is the case in tort law jurisprudence, certain scenarios render the but-for test futile . [92] The test is ill-suited where multiple defendants contribute to some extent to the victim’s death and it is unclear what would have transpired but for a particular defendant’s involvement. [93] Furthermore, the but-for test is unhelpful where death would have ensued even without the accused’s act, such as in cases where the accused prematurely kills a victim that is on the verge of death. [94] The test is also inadequate in the presence of intervening acts, where courts must engage in a form of contrastive causation that necessarily assesses the significance of the accused’s contribution to the victim’s death. [95]

Michael Moore argues that but-for causation can be problematic because it does not generally consider the intensity of one’s contribution to a result. [96] Consequently, in hard cases, courts must necessarily depart from but-for causation and examine whether the accused contributed significantly to the victim’s death—the precise approach adopted by the Supreme Court of Canada in Nette and Maybin . [97] In a similar vein, Butt points out that courts convict defendants where they contribute significantly to the victim’s death despite not being the but-for cause of that result. This is notably the case where multiple co-principals attack a victim, yet each attack is sufficient to cause death. [98]

Similarly, courts assess the significance of the defendant’s contribution to a result in contexts where several co-principals mutually engage in some conduct that creates serious risks of harm and results in death. For instance, in R. v. Menezes , the defendant was street racing against another vehicle, driven by Meuszynski. [99] At some point, Meuszynski’s car left the roadway and collided with a utility pole. He died in the accident. At issue was whether Menezes could be convicted of criminal negligence causing death for having co-participated in the street race. [100] Justice Hill Jr. declared that the defendant could not exculpate himself on the basis of the victim’s contributory negligence, [101] observing that factual causation could be satisfied even though the defendant did not physically collide with the deceased’s vehicle. [102] The judge applied the significant contributing cause test, interrogating whether the defendant’s contribution to the death was sufficiently material as opposed to collateral. [103] Justice Hill Jr. reasoned that co-participants in a street race both assume responsibility for the danger created by this jointly maintained activity, including for the death of one of the drivers—an approach adopted by other courts in similar cases. [104] Likewise, in contexts involving shootouts between co-principals, courts have held that one co-principal factually contributes to a victim’s death resulting from the other co-principal’s gunshot. [105] In these types of cases, courts evaluate the accused’s factual involvement in bringing about a consequence by looking at its intensity—whether the contribution is so significant that it cannot logically be divorced from the consequence.

These types of concerns lead some scholars to observe that the but-for test is most useful only in the easiest cases, where it is least needed. [106] Recognizing that harder cases inevitably require a consideration of the extent of the accused’s contribution to a result, Weinrib suggests that courts could avoid using but-for causation in many cases. [107] He remarks: “[I]t may be best to acknowledge that we can come no closer to an adequate solution of the cause in fact problem than to confront it directly by asking simply whether the defendant’s conduct was a substantial factor in producing the injury” [108] —a suggestion that acknowledges the necessity of examining significant contributing cause in hard cases. Butt contends that such a charge would be more consistent with how juries are actually instructed when evaluating causation: to ask themselves, “Did the accused contribute significantly to the victim’s death?” [109]

In complicated cases with either multiple contributing causes or intervening acts, courts routinely hold that the ultimate causation question is whether the accused contributed significantly to the victim’s death—an inquiry that places greater importance on the requisite strength of the accused’s contribution to a result as opposed to a counterfactual assessment about their involvement. [110]

III. Rethinking Intervening Acts and Legal Causation

Conceptions of legal causation in Canadian criminal law similarly require rethinking. The doctrine of independent intervening acts applies only in restricted circumstances and has largely been overshadowed by the doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts. The latter remains useful and is distinct from the foreseeability inquiry under mens rea; it serves to limit criminal liability where unforeseeable contributing causes fall outside the ambit of risk associated with the accused’s initial conduct.

A. The Limited Role of Independent Intervening Acts in Canadian Law

The Supreme Court of Canada has alluded to different decisions as examples of judges employing the doctrine of independent intervening acts. In Maybin , the Court cited Shilon (the car-chase case) and Hallett (the rising tide case) as examples where courts maintained legal causation because the intervening act was not independent. [111] However, those decisions are unhelpful in illuminating the doctrine of independent intervening acts because they were resolved on the basis of the intervening act’s reasonable foreseeability.

Due to a combination of factors, the independent intervening act doctrine has been interpreted restrictively by Canadian courts compared to the doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts. Those same factors also account for why the doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts has largely overshadowed the doctrine of independent intervening acts.

First, Canadian courts tend to recognize that the victim’s own voluntary, deliberate, and informed conduct does not constitute an independent intervening act that breaks legal causation. [112] This is most notably the case where the victim dies after consuming drugs or some other harmful substance that the accused provided. In the Manitoba Court of Appeal decision R. v. Haas (CJ) , the accused gave the victim morphine pills. [113] She consumed the pills and died of a drug overdose. Haas was convicted of unlawful act manslaughter. The Court of Appeal upheld the conviction. The judges concluded that the accused’s conduct was an instrumental and significant cause of death, notwithstanding the victim’s voluntary decision to consume the drugs. [114] Other Canadian courts have arrived at the same conclusion in similar cases. [115]

The doctrine of independent intervening acts plays a greater role in England and other jurisdictions, where courts hold that the victim’s voluntary, informed, and deliberate conduct can sever causation. [116] In the UK House of Lords decision R. v. Kennedy , the defendant was a drug dealer who provided the victim with an opioid-filled syringe. [117] The victim injected the substance into his arm and died of a drug overdose. The defendant was convicted at trial of manslaughter, and the conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeal. The House of Lords substituted an acquittal, concluding that the victim’s autonomous act broke the causal chain. [118] By rejecting Kennedy ’s application in Canada, Canadian courts have largely restricted the use of the independent intervening acts doctrine. [119]

Second, certain Criminal Code provisions and common law rules restrict the application of independent intervening acts as an analytical tool. The victim’s refusal to receive life-saving care does not constitute an independent intervening act [120] —and neither does a third party’s good faith, although improper, medical treatment applied to a victim injured by the accused. [121]

Third, the criminal law’s rejection of contributory negligence and apportionment of liability also confines the doctrine of independent intervening acts. [122] This analytical tool serves to absolve the accused of responsibility only where a third party’s conduct or the victim’s own act is deemed to be the sole legal cause of the latter’s death. [123]

In Canadian criminal law, the doctrine of independent acts is generally subsumed by the test for reasonably foreseeable intervening acts. When courts inquire whether an independent act severs causation because its occurrence is extraordinary, they are inquiring whether the act is reasonably foreseeable. [124] The latter analytical tool will generally do the necessary legwork. The same is true where the accused’s conduct sets the scene for a third party’s assault, making the latter’s act the exclusive legal cause of the victim’s death. [125] In such contexts, the criminal law withholds the defendant’s liability for the victim’s death due to concerns about fair attribution.

Like in ordinary life, the criminal law recognizes that defendants exert meaningful control over their own conduct and its potential risks. An accused tends to exert less control, however, over others’ autonomous acts and the sphere of risks that others create. [126] When the general nature of others’ acts and their inherent risks are unforeseeable and too removed from the defendant’s autonomous conduct, those acts are deemed to be independent. In such cases, the harm that claims the victim’s life falls within an unanticipated sphere of risk that is more properly attributable to someone other than the accused. Here too, an analysis of the act’s independence collapses into an inquiry into its reasonable foreseeability. In other words, when assessing the general nature of the novus actus , courts evaluate whether something about the intervening act—its likelihood, type, scope, temporal remoteness, or surprising nature—undermines the intervening act’s reasonable foreseeability.

B. Why Reasonably Foreseeable Intervening Acts Matter for Causation

The doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts plays a more prominent role in assessing legal causation within Canadian criminal law. This section argues that the doctrine’s purpose is distinct from the reasonable foreseeability inquiry as part of mens rea . It shows why an intervening act’s reasonable foreseeability acts as a heuristic (or rule of thumb) that is used to assess whether an ambit of risk can be fairly ascribed to the accused.

In Maybin , the Supreme Court of Canada observed that the analytical tool of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts closely aligns with the mens rea for manslaughter. [127] Yet to distinguish causation from the moral fault requirement for that crime, the Court held that the general nature of the intervening act and its accompanying risk of harm must be reasonably foreseeable at the time of the accused’s unlawful conduct. [128] As Justice Karakatsanis explained, causation generally remains intact where the intervening act and accompanying harm reasonably flow from the accused’s conduct. [129]

Butt argues that it is redundant to analyze the reasonable foreseeability of intervening acts because mens rea already requires proof of objective foresight of bodily harm. [130] In his view, the causation analysis should remove moral fault considerations. [131] Rather, courts should resort to the independent act tool and examine whether the intervening act is so proximally remote that it overshadows the accused’s behaviour as the sole cause in law of the victim’s death. [132] Certain courts share a somewhat similar view, observing that reasonable foreseeability is generally associated with moral fault and should be kept separate from causation and actus reus. [133]

The doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts, however, plays a role that is distinct from foreseeability with respect to mens rea. As explained further below, it acts as a safety valve to prevent unfair labelling. The doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts assesses the relationship between the accused’s wrongful conduct and the victim’s death, even where the accused possesses sufficient moral fault. [134] The doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts provides a legal heuristic for evaluating whether a contributing cause fell within the ambit of risk inherent to the accused’s wrongful and dangerous behaviour. [135] The term “ambit of risk” does not merely allude to the reasonable foreseeability of the intensity of certain risks or the possibility of some result materializing. Rather, it also encompasses the origin of certain risks and the kind of risks that reasonably flow from one’s conduct in a given circumstance.

Where causation is a significant issue, most cases turn on the fact that the victim suffered greater harm because of an intervening act than they would have experienced without its occurrence. For instance, an unconscious victim left face down on the pavement is not subject to a risk of drowning. An unconscious victim left face down on a beach and submerged in water (like in Hallett ) is subject to that added risk. In a similar vein, one-on-one fights in an isolated setting do not create additional risks that others will become involved and unfairly gang up on the victim. As was the case in Maybin , barfights do create that added risk. Intervening acts matter because the additional risks that those acts generate are often the difference between life and death. The scope of risk is therefore greater where the accused’s unlawful conduct exposes the victim to additional contributory sources of harm that otherwise would not arise.

Legal causation assesses whether additional contributory causes fall within the range of risks associated with the accused’s conduct and are therefore fairly ascribable to them. [136] In some contexts, unchosen and completely unforeseeable intervening causes play the predominant role in the victim’s death. Those contributory causes fall outside of the ambit of risk attributable to the accused. Such cases create a logical gap between the sphere of risk created by the accused’s behaviour and some tragic result.

Where such logical gaps are formed, the doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts withholds blaming the accused for the victim’s death due to fairness concerns related to both culpability and punishment. When the intervening act was unchosen, unforeseeable, and outside the scope of risks that flow from the accused’s conduct, it is difficult to justify punishing them for causing the victim’s death on the basis of desert or deterrence principles. [137] The upshot is that it is fairer to blame and punish defendants for reasonably foreseeable contributing causes that fall within the range of risks that they create. Legal causation recognizes that although defendants lack control over the consequences of creating a certain sphere of risk, they maintain greater control over their initial creation.

Legal causation—and the doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts—thus corrects for potential unfair blaming practices in the criminal law. [138] For instance, an accused’s dangerous and unlawful act might create a reasonably foreseeable risk of bodily harm. That very act may cause minor injuries to the victim. Suppose the victim decides to go to the hospital by ambulance as a precautionary measure. The ambulance is struck by a reckless driver and the victim dies. Causation ensures that the accused is not blamed for causing the victim’s death despite the fact that their act could have led to the same result. [139] Legal causation recognizes that an unforeseeable car accident caused by a reckless driver is a contributory cause that falls outside the realm of risk created by the accused’s initial assault—the doctrine excludes the accused’s conduct as an instrumentally salient cause of death.

In this way, legal causation acts as an additional fairness constraint that promotes fair labelling, especially in contexts where the accused satisfies a low-level mens rea requirement. [140] Cause in law blocks tempting, but inappropriate, desert-based inferential reasoning where the accused possessed sufficiently reprehensible mens rea. As an ascriptive constraint, it counteracts the enticement to attribute bad outcomes to the accused based on intuitions about what they deserve given their moral fault. Legal causation excludes ascribing certain results to the accused where their culpable and wrongful acts are simply a condition but not an instrumental and salient legal cause of the victim’s death. [141] The doctrine of reasonably foreseeable intervening acts affirms that certain unforeseeable contributing causes are not fairly ascribable to the accused because they fall outside the sphere of risk created by their conduct.

IV. Causation and Fair Attribution

The previous Parts highlighted certain limitations to the Supreme Court of Canada’s conceptions of factual causation, legal causation, and intervening acts. Building on Andrew Simester’s work, this Part provides an account of causation that is rooted primarily in the notions of attribution and fair labelling, as opposed to moral innocence. [142] It shows how attribution is concerned with connecting negative changes in the world and the creation of certain risks to some individuals at the exclusion of others. [143] Having set out that account, it then challenges the Supreme Court of Canada’s rationale for causation as necessary to prevent the conviction of morally innocent persons.

A. Factual Causation: An Ascriptive Approach

In Nette , Justice Arbour observed that factual causation “is concerned with an inquiry about how the victim came to his or her death, in a medical, mechanical, or physical sense, and with the contribution of the accused to that result.” [144] Later, in Maybin , the Court added that factual causation is inclusive in scope—it determines who can be deemed to have factually contributed to some result. [145]

One shortfall of that view is that it cannot provide an account of causation for omissions, whose hallmark is the defendant’s inaction or non-intervention in the face of a duty to act. [146] The lack of a physical act implies that the defendant does not, in any positive sense, medically, physically, or mechanically contribute to the victim’s death. [147] Yet the criminal law still recognizes causal relations between a defendant’s inaction and the victim’s worsened plight, such as a parent’s failure to feed their child, resulting in the child’s injury or death. [148] Scholars such as George Fletcher, Arthur Leavens, and John Kleinig argue that factual causation is grounded in the existence of some pre-existing duty that creates a form of reliance between the defendant and the victim, making the accused responsible in fact for the victim’s plight. [149] The nature of the relationship between accused and victim is at the root of causation. [150] The notion of duties to act recognizes that defendants are responsible both for actions that intrude upon another’s interests as well as for inactions that deprive others of their interests. [151] Factual causation therefore must be concerned with something more than physical, medical, or mechanical contributions to results.

One way of addressing that shortfall is by thinking about factual causation in terms of ascription —the practice of attributing changes that take place in the world to particular individuals. Factual causation is largely concerned with tying events or states of affairs to individuals, be it through their actions or inactions. It links an individual to the changes that they effectuate in the world and that are properly attributable to them. [152] In the realm of criminal law, defendants’ conduct characteristically effectuates changes that worsen the victim’s plight or creates unreasonable risks to others. [153] As a heuristic used to draw inferences between conduct and outcomes, factual causation assesses whether some individual’s conduct is responsible for causing states of affairs to change for the worse. [154] Legal causation serves to ascribe prima facie moral responsibility in the form of a connection between the actor’s conduct and negative changes, to the exclusion of other persons . [155] For that reason, Simester observes that factual causation acts as a form of “boundary rule.” [156]

The more significant the accused’s contribution to some state of affairs, the greater the connection (or the stronger the inference) between their conduct and negative changes that occur in the world. Factual causation thus requires the state to provide a public account of why that individual is being singled out as a subject of potential criminal liability. The cause in fact inquiry answers one of the most basic questions at the heart of criminal liability: Why me ?

B. Legal Causation and Fair Attribution

In Canadian law, courts justify legal causation primarily on the basis that it prevents the conviction of morally innocent persons. That rationale was first advanced in the Ontario Court of Appeal decision R. v. Cribbin and was later affirmed in Nette and Maybin . [157] In Cribbin , Justice Arbour explained:

I refer to the link between causation and the fault element in crime, represented in homicide by foresight of death or bodily harm, whether subjective or objective, because it serves to confirm that the law of causation must be considered to be a principle of fundamental justice akin to the doctrine of mens rea . The principle of fundamental justice which is at stake in the jurisprudence dealing with the fault element in crime is the rule that the morally innocent should not be punished. [158]

Justice Arbour reiterated that position in Nette , where she observed:

Legal causation, which is also referred to as imputable causation, is concerned with the question of whether the accused person should be held responsible in law for the death that occurred. It is informed by legal considerations such as the wording of the section creating the offence and principles of interpretation. These legal considerations, in turn, reflect fundamental principles of criminal justice such as the principle that the morally innocent should not be punished. [159]

The Supreme Court of Canada unanimously endorsed that statement in Maybin , observing that “[a]ny assessment of legal causation should maintain focus on whether the accused should be held legally responsible for the consequences of his actions, or whether holding the accused responsible for the death would amount to punishing a moral innocent.” [160] The argument that legal causation is necessarily justified by the need to prevent the conviction of morally innocent persons, however, is problematic for several reasons.

First, it ignores contexts where courts concede that the accused contributed to the victim’s death but withhold blame for that result nonetheless. Consider the following hypothetical. [161] Suppose that the accused intentionally causes low-level, objectively foreseeable bodily harm to the victim. [162] The victim is subsequently transported to a hospital for precautionary treatment. The ambulance is involved in a car accident and the victim dies. The accused’s dangerous and unlawful act was a significant factual contribution to the victim’s eventual death, meaning that the accused shares some responsibility for its occurrence. Yet because the accused only caused low-level bodily harm and the range of risk created by their conduct did not encompass a car accident, it is unjust to blame them for that death. [163]

In such cases, the law does not construe the accused as morally innocent, especially if they intended to cause bodily harm and succeeded. [164] Rather, it concedes the accused’s culpable contribution to the victim’s death but withholds blame for reasons more closely tied to the principles of attribution and fair labelling. [165] As described by Antony Duff, the core problem with blaming the accused for death in such contexts is not that the accused is innocent, but that they are “not that guilty.” [166] Fair labelling is violated where the accused is punished for something other than what they did or caused, because they are wrongly blamed for conduct or consequences that are not fairly attributable to them. [167] Legal causation therefore acts as a moral constraint that legitimates blaming practices in the criminal law. It draws a boundary between moral fault and attribution of results to individuals. [168]

Second, the need to protect morally innocent persons from conviction and punishment is generally rooted in incapacity or lack of moral fault. Various criminal law doctrines illustrate this point. [169] In Reference Re B.C. Motor Vehicle Act , the Supreme Court of Canada recognized a principle of fundamental justice that absolute liability offences cannot be combined with imprisonment. [170] Chief Justice Lamer explained that the provision in question was problematic because morally innocent individuals could be convicted and punished despite their due diligence, accident, or mistake of fact—all of which suggest a lack of moral fault. [171] Capacity-based concerns underlie the requisite degree of fault for objective mens rea . [172] Individuals must at least have the capacity to appreciate the risks inherent to their conduct to satisfy the objective standard of fault. [173] These criminal law doctrines generally aim to prevent the conviction of the morally innocent on the basis of physical or mental incapacity, or on the basis of a lack of moral fault.

Causation, on the other hand, is more concerned with fair attribution and accepts the defendant’s capacity and culpable state of mind. [174] Yet blame is withheld for an entirely different reason: that it is unfair to blame the accused for harms, risks, or consequences that are not ascribable to them. [175] As Simester explains:

Rather than culpability, the primary role of a finding of causation concerns ascriptive responsibility. It identifies D as an author of the relevant event. In turn, the primary legal role of causation is to identify defendants (and plaintiffs) and, where appropriate, to link defendants to plaintiffs, victims, and harms. [176]

Third, much like legal causation, other criminal law doctrines affirm that actors may act culpably but that it is unjust to blame and punish them due to concerns about fair attribution, rather than moral innocence. In R. v. Ruzic , the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that the basis of excuses is moral involuntariness and not moral innocence. [177] The Court explained that it would be unjust to attribute criminal responsibility to defendants who culpably commit crimes under duress. [178] In the Court’s view, moral involuntariness undermines fair attribution—a principle that is distinct from moral innocence. [179] Thus, when the accused is excused under the doctrine of duress, conviction and punishment are inappropriate despite blameworthy conduct. [180] The causation requirement is more plausibly justified by similar rationales that acknowledge fault but withhold blame.

Comparable concerns animate blaming practices for inchoate offences, where the accused does not successfully commit the crime or produce certain harms, as is the case for attempts and conspiracy. Sanford Kadish remarks that criminal law differentiates between blame for complete versus incomplete acts and materialized versus unmaterialized harms; [181] for inchoate offences, fair labelling recognizes the ascriptive connection between a person’s act and the completeness of that act or outcome. [182]

Cause in law thus acknowledges that an individual’s conduct significantly contributed to effectuating negative changes in the world. But it does not inquire specifically whether the harm that flowed from the accused’s conduct was reasonably foreseeable—a question that falls more within mens rea . Rather, legal causation assesses whether an additional contributing cause can fairly be ascribed to the accused because it fell within the ambit of risk generated by their initial wrongful conduct. [183] Thus, while factual causation ties changes in the world to individuals, legal causation ascribes scopes of risk to those individuals. Cause in law strives to answer a fundamental question rooted in fidelity to fair labelling practices: Why am I being blamed for this ?

This article advances an account of causation rooted in principles of ascription and fair labelling. It challenges the Supreme Court of Canada’s conception of factual and legal causation and their underlying rationales. It argues that causation is less concerned with avoiding the conviction of morally innocent individuals than with fairly attributing changes in the world and scopes of risk to some individuals while excluding others. The need to prove causation imposes a duty on the state to provide an account of why X (and not someone else) is blamed for Y (and not something else) . To that end, factual causation assesses whether one’s conduct significantly contributes to worsening the victim’s situation. Legal causation then evaluates whether individuals—including those with sufficient moral fault—can be fairly blamed for the materialization of risks that are properly ascribable to them.

This article admittedly leaves some questions unanswered—questions that most certainly merit to be explored in the near future. Most notably, one might inquire whether we should simply do away with the distinction between factual and legal causation altogether. As some judicial decisions point out, the ultimate causation question might be whether the accused contributed significantly to the result—an approach that is consistent with how juries ought to be instructed when causation is a live issue. [184] If that is the case, then why distinguish between factual and legal causation at all? Insofar as the answer to that question is more rooted in a commitment to experience rather than logic, it may be time to seriously reconsider our approach to causation in the criminal law altogether. [185] Yet it is also unclear whether a unified approach to causation—one that merges both factual and legal causation—will truly provide a more coherent path forward.

Indeed, like so many other complex areas of human life, we struggle to understand how things come to be and what our role is in effectuating changes in the world. In many respects, the law of causation, as well as the elusive attempt to simplify its principles and avoid mistakes, reflects this challenge. Although causation within the criminal law marks a noble attempt to fairly single out actors for changing others’ lives for the worse, it remains a heuristic that is itself vulnerable to constant questioning, criticism, and potential error. Like the human beings subject to its principles, causation in the law remains imperfect.

[1] See R v Maybin , 2012 SCC 24 at para 15 [ Maybin ]; R v Nette , 2001 SCC 78 at para 44 [ Nette ].

[2] See Nette , supra note 1 at para 45, citing Glanville Williams, Textbook of Criminal Law , 2nd ed (London, UK: Stevens & Sons, 1983) at 381–82. See also Maybin , supra note 1 at paras 15–16; Larry Alexander, “Michael Moore and the Mysteries of Causation in the Law” (2011) 42:2 Rutgers LJ 301 at 301–02.

[3] See e.g. Maybin , supra note 1.

[4] See e.g. R v Hallett (1969), SASR 141 (SA Sup Ct) [ Hallett ].

[5] See e.g. R v Reid , 2003 NSCA 104.

[6] See e.g. R v Blaue , [1975] EWCA Crim 3, [1975] 1 WLR 1411 (CA) [ Blaue ]; R v Tower , 2008 NSCA 3 [ Tower ]. See also Olga Redko, “Religious Practice as a ‘Thin Skull’ in the Context of Civil Liability” (2014) 72:1 UT Fac L Rev 38 at 52–53, 66–67.

[7] See Glanville Williams, “Finis for Novus Actus ? ” (1989) 48:3 Cambridge LJ 391 at 391.

[8] See Douglas Husak, “Abetting a Crime” (2014) 33:1 Law & Phil 41 at 68–71; Terry Skolnik, “Responsibility and Intervening Acts: What ‘ Maybin ’ an Overbroad Approach to Causation” (2014) 44:2 RGD 557 at 567. On the notion of moral luck, see Thomas Nagel, Mortal Questions (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1979) ch 3.

[9] On the relationship between fault and stigma, see Kent Roach, “Mind the Gap: Canada’s Different Criminal and Constitutional Standards of Fault” (2011) 61:4 UTLJ 545 at 546, 556–59, 566–67.

[10] See R v Wallace , [2018] EWCA Crim 690 at para 52 [ Wallace ]; Russell Brown, “The Possibility of ‘Inference Causation’: Inferring Cause-in-Fact and the Nature of Legal Fact-Finding” (2010) 55:1 McGill LJ 1 at 33.

[11] See Fleming James Jr & Roger F Perry, “Legal Cause” (1951) 60:5 Yale LJ 761 at 763; Husak, supra note 8 at 66–71.

[12] See Jeremy Butt, “Removing Fault from the Law of Causation” (2018) 65 Crim LQ 72 at 80–83.

[13] See ibid at 89–90 .

[14] See Nette , supra note 1 at para 45; Maybin , supra note 1 at paras 16, 57, 59.

[15] On fair labelling, see AJ Ashworth, “The Elasticity of Mens Rea ” in CFH Tapper, ed, Crime, Proof and Punishment: Essays in Memory of Sir Rupert Cross (London, UK: Butterworths & Co, 1981) 45 at 53–56.

[16] See David Ormerod & Karl Laird, eds, Smith, Hogan, and Ormerod’s Criminal Law , 15th ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) at 29.

[17] Don Stuart, Canadian Criminal Law , 7th ed (Toronto: Carswell, 2014) at 142.

[18] See ibid .

[19] See Alexander, supra note 2 at 301.

[20] See ibid.

[21] Nette , supra note 1 at para 44.

[22] See James & Perry, supra note 11 at 762–63.

[23] See Smithers v R (1977), [1978] 1 SCR 506 at 518, 75 DLR (3d) 321 [ Smithers ].

[24] See The Honourable S Casey Hill, David M Tanovich & Louis P Strezos, McWilliams’ Canadian Criminal Evidence , 5th ed (Toronto: Thompson Reuters, 2019) vol 2 at 12:30.60.10. See e.g. Smithers , supra note 23; R v Shanks (1996), 4 CR (5th) 79 at para 10, 1996 CanLII 2080 (ONCA) [ Shanks ]; R v Pimentel , 2000 MBCA 35 at para 63.

[25] See Michael Moore, “Causation in the Criminal Law” in John Deigh & David Dolinko, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Criminal Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011) 168 at 170–71. See e.g. R v Sinclair (T) , 2009 MBCA 71 at para 38 [ Sinclair ], rev’d on other grounds 2011 SCC 40.

[26] Supra note 23 at 519.

[27] Ibid .

[28] See David Ormerod & Karl Laird, eds, Smith and Hogan’s Criminal Law , 14th ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) at 91–92.

[29] See HLA Hart & Tony Honoré, Causation in the Law , 2nd ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985) at 172–73 (the authors use the alternate term “eggshell skull”). See e.g. Athey v Leonati , [1996] 3 SCR 458 at paras 34–35, 140 DLR (4th) 235. The thin skull principle was entrenched in the common law and recognized by scholars such as Hale and Stephen: see Sir Matthew Hale, Historia Placitorum Coronae: The History of the Pleas of the Crown (London, UK: Nutt & Gosling, 1736) vol 1 at 428; Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England (London, UK: MacMillan & Co, 1883) vol 3 at 5–7. Stephen, however, cautioned that causation would be negated where the relationship between the defendant’s act and the consequence was too “obscure” ( ibid at 3).

[30] See Dennis Klimchuk, “Causation, Thin Skulls and Equality” (1998) 11:1 Can JL & Jur 115 at 124 [Klimchuk, “Thin Skulls”]; M Anne Stalker, “Chief Justice Dickson’s Principles of Criminal Law” (1991) 20:2 Man LJ 308 at 309–11.

[31] See e.g. Nette , supra note 1 at para 79.

[32] See ibid at para 49.

[33] Ibid at para 71. Many courts suggest that the significance of the defendant’s contribution to the result is part of factual rather than legal causation (see e.g. R v Kippax , 2011 ONCA 766 at para 24 [ Kippax ]; Cormier c R , 2019 QCCA 76 at para 16; R v Romano , 2017 ONCA 837 at paras 27–28; Sarazin c R , 2018 QCCA 1065 at para 21). This article adopts that position. Some decisions, however, suggest that an intervening act cancels the significance of the defendant’s contribution to a result, which seems to suggest that the significance of the defendant’s contribution to a result is part of legal rather than factual causation (see e.g. Maybin , supra note 1 at paras 5, 29). Lastly, other decisions seem to suggest that the ultimate question that both factual and legal causation must address is whether the defendant contributed significantly to the result, making it unclear whether the significance of the contribution is part of factual or legal causation (see e.g. R v Talbot , 2007 ONCA 81 at para 81 [ Talbot ]; Sinclair , supra note 25 at para 39).

[34] See Nette , supra note 1 at para 71 .

[35] See ibid at para 72. Some scholars have also argued that the term “beyond the de minimis range” is not fixed, but depends on the circumstances of the case: see e.g. Hillel David, W Paul McCague & Peter F Yaniszewski, “Proving Causation Where the But For Test is Unworkable” (2005) 30:2 Adv Q 216 at 223.

[36] See Maybin , supra note 1 at para 16; Eric Colvin, “Causation in Criminal Law” (1989) 1:2 Bond L Rev 253 at 254.

[37] See Tower , supra note 6 at para 25 (cited with approval in Maybin , supra note 1 at para 23).

[38] See Sanford H Kadish, “Complicity, Cause and Blame: A Study in the Interpretation of Doctrine” (1985) 73:2 Cal L Rev 323 at 407 [Kadish, “Complicity, Cause and Blame”].

[39] See Criminal Code , RSC 1985, c C-46, ss 222(5)(c), 224, 225, 226.

[40] See ibid , s 224.

[41] See Tower , supra note 6 at para 31 (manslaughter conviction upheld despite the victim’s refusal of medical care after being injured by the accused, who had attacked him with long-handed pruning shears); R c Gosselin , 2011 QCCQ 7696 [ Gosselin ] (manslaughter conviction entered where the victim was stabbed by the accused and refused to go the hospital); Blaue , supra note 6 at 1414–15 (causation maintained despite the victim’s refusal of a blood transfusion on religious grounds).

[42] See Criminal Code , supra note 39, s 225.

[43] See s upra note 1 at para 5.

[44] See ibid at paras 30–44; Jonathan Herring, Criminal Law: Text, Cases, and Materials , 6th ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) at 124–26, citing Klimchuk, “Thin Skulls”, supra note 30 at 129–35.

[45] See Maybin , supra note 1 at paras 45–59.

[46] S upra note 4 at 155.

[47] For a similar decision, see R v Hart , [1986] 2 NZLR 408 (CA).

[48] (2006), 240 CCC (3d) 401, [2006] OJ 4896 (QL) (Ont CA).

[49] See ibid at para 41 .

[50] See ibid at paras 38–39 .

[51] See Maybin , supra note 1 at para 27, citing R v Pagett , [1983] EWCA Crim 1 [ Pagett ].

[52] See Maybin , supra note 1 at para 50.

[53] See ibid at para 51.

[54] See ibid.

[55] See Gerry Ferguson, “Causation and the Mens Rea for Manslaughter: A Lethal Combination” (2013) 99 CR (6th) 351 at 351–53.

[56] See Maybin , supra note 1 at para 57; R v Leroux , 2018 BCSC 1429 at para 44 [ Leroux ].

[57] See Nette , supra note 1 at para 72.

[58] Ibid.

[59] See Stanley Yeo, “Giving Substance to Legal Causation” (2000) 29 CR (5th) 215 at 218–20.

[60] Ibid at 219 .

[61] Nette , supra note 1 at para 7.

[62] See Hugues Parent, Traité de droit criminel, t 2, 2nd ed (Montreal: Thémis, 2007) at para 74.

[63] See e.g. ibid ; Jill Presser, “All for a Good Cause: The Need for Overhaul of the Smithers Test of Causation” (1994) 28 CR (4th) 178 at 178–83, cited in Stuart, Canadian Criminal Law , supra note 17 at 151.

[64] Presser, supra note 63 at 183.

[65] David M Tanovich & James Lockyer, “Revisiting Harbottle: Does the ‘Substantial Cause’ Test Apply to All Murder Offences?” (1996) 38:3 Crim LQ 322 at 332. See also R v F(D) (1989), 52 CCC (3d) 357 at 365, ( sub nom R v DLF ) 1989 ABCA 286 (CanLII).

[66] See Anne-Marie Boisvert, “La responsabilité versant acteurs : vers une redécouverte, en droit canadien, de la notion d’imputabilité” (2003) 33:2 RGD 271 at 288.

[67] See ibid.

[68] See ibid . See also Nette , supra note 1 at para 49.

[69] See Law Reform Commission of Canada, Report on Recodifying Criminal Law , Report 31 (Ottawa: Law Reform Commission of Canada, 1987) at 28, cited in Donald Galloway, “Causation in Criminal Law: Interventions, Thin Skulls and Lost Chances” (1989) 14:1 Queen’s LJ 71 at 80. Note that Galloway disagrees with the Law Reform Commission’s definition of the causation standard.

[70] See s upra note 69 at 28 .

[71] See Don Stuart, “ Nette : Confusing Cause in Reformulating the Smithers Test” (2002) 46 CR (5th) 230 at 230–31 [Stuart, “Confusing Cause”].

[72] Supra note 24.

[73] See ibid at para 8 .

[74] See Stuart , “Confusing Cause”, supra note 71 at 230–31.

[75] See Glanville Williams, “Convictions and Fair Labelling” (1983) 42:1 Cambridge LJ 85 at 85.

[76] See Joseph J Arvay & Alison M Latimer, “The Constitutional Infirmity of the Laws Prohibiting Criminal Negligence” (2016) 63 Crim LQ 324 at 344.

[77] See Criminal Code , supra note 39, ss 220, 236.

[78] See generally Lawrence M Solan, “Law, Language, and Lenity” (1998) 40:1 Wm & Mary L Rev 57 at 58; Stephen Kloepfer, “The Status of Strict Construction in Canadian Criminal Law” (1983) 15:3 Ottawa L Rev 553 at 553 . For an overview of lenity in criminal law, see Kent Roach, Criminal Law , 7th ed (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2018) at 92, 100, 102.

[79] See William J Stuntz, “The Pathological Politics of Criminal Law” (2001) 100:3 Mich L Rev 505 at 561.

[80] See R v Hasselwander , [1993] 2 SCR 398 at 411–13, 81 CCC (3d) 471.

[81] See Glanville Williams, Criminal Law: The General Part , 2nd ed (London, UK: Stevens & Sons, 1961) at 588–89.

[82] See Livingston Hall, “Strict or Liberal Construction of Penal Statutes” (1935) 48:5 Harv L Rev 748 at 763–64; Zachary Price, “The Rule of Lenity as a Rule of Structure” (2004) 72:4 Fordham L Rev 885 at 912–25; Peter Westen, “Two Rules of Legality in Criminal Law” (2007) 26:3 Law & Phil 229 at 281–83.

[83] See e.g. R v Mankda, 2017 ONSC 5745 at para 19; R v Boffa, 2018 BCSC 768 at para 80; R v Bridle , 2007 BCSC 1100 at paras 24–25 (all using the beyond de minimis range test). See also the review of the trial judge’s instructions in Sinclair , supra note 25 at paras 22, 42. Other courts hold that judges may employ either the beyond the de minimis range test or the significant contributing cause test: see e.g. R v Harvey , 2016 BCCA 149 at para 20.

[84] See supra note 1 at para 72.

[85] See Maybin , s upra note 1 at paras 5, 7, 23, 28, 29, 38, 44, 59–61.