Myanmar’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Subscribe to global connection, ashwini deshpande , ashwini deshpande associate in research at the center for policy impact in global health - duke university khaing thandar hnin , and khaing thandar hnin director - strategy, technical, policy and research unit - community partners international tom traill tom traill policy and research director - community partners international.

December 1, 2020

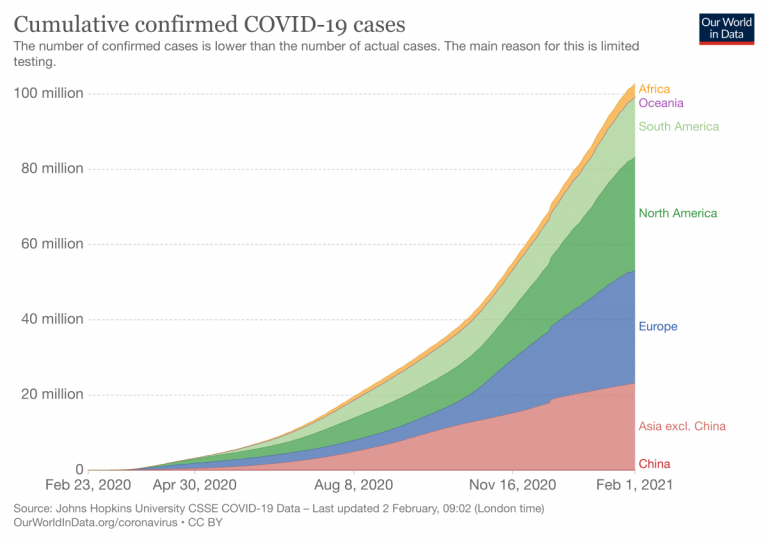

During the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, from late March to early August, Myanmar recorded just 360 cases and 6 deaths. Early in the crisis, the government rapidly implemented measures to contain the virus. Just as it started easing them though, the country was hit by a major second wave in mid-August. Daily cases increased from less than 10 per day in early August to over 1,000 per day in mid-October . This wave has overwhelmed Myanmar’s inadequate and understaffed health infrastructure. By November 20, there were 76,414 confirmed cases and 1,695 deaths (Figure 1).

Figure 1 a. Cumulative active confirmed cases, discharged patients and deaths

Figure 1b. COVID-19 cases by region

Source: Ministry of Health and Sports, Myanmar . Note: Data as of November 20, 2020 .

In the November 2020 national elections, Myanmar civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won comfortably to stay in power. The government now faces the task of stemming the rapid increase in cases. What can the country do to quickly contain COVID-19? Duke University’s Center for Policy Impact in Global Health and Community Partners International in Yangon analyzed Myanmar’s pandemic preparedness and its policy response to provide an answer to this question. Besides summarizing the current situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, our recent policy report identifies policy gaps that the new government has to plug.

Weaknesses: Testing capacity, health infrastructure, income security, and domestic stability

A day after the World Health Organization notified governments about the unexplained pneumonia cases in Wuhan in January, Myanmar set up surveillance at points of entry to the country. Since March, it has implemented domestic and international travel restrictions while issuing guidance on personal hygiene, COVID-19 symptoms, and social restrictions in public spaces (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Timeline of the policy and coordination measures by the Myanmar government

Key: blue indicates public health policies; green indicates social and economic measures; orange indicates health system respo nse

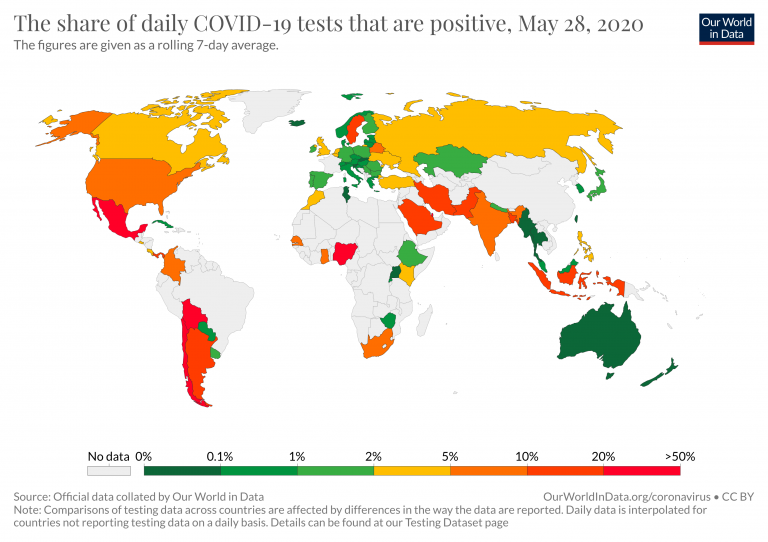

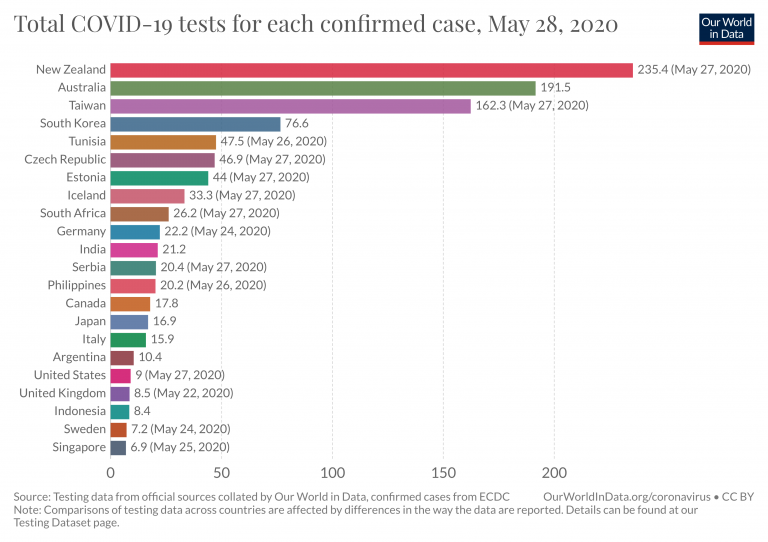

Inadequate testing capacity. Since the start of the pandemic, the government took steps to expand its testing capacity. In early October, it could conduct over 10,000 tests daily, a substantial rise from the 380 tests per day in March. But this is not enough to keep pace with the soaring second wave. Since mid-October, the rate of positive tests has been about 10 percent —implying that the confirmed cases represent only a small fraction of infected people. As of November 22, Myanmar had conducted 1,998.7 tests per 100,000 people . Limited availability of detection systems, dependence on other countries for testing kits, and shortages of human resources such as trained laboratory technicians and logistics and data managers are some of the main factors compromising laboratory testing.

Unprepared health system. According to the 2019 Global Health Security Index , Myanmar was least prepared in terms of the availability of health systems to treat the sick and protect health care workers. Myanmar had just 6.7 physicians per 10,000 people in 2018, significantly lower than the global average of 15.6 physicians per 10,000 people in 2017. Besides, it only had 10.4 hospital beds per 10,000 people. In March 2020, Myanmar reported just 0.71 intensive care unit beds and 0.46 ventilators per 100,000 population, which were insufficient to deal with even a moderate outbreak. The government has increased surge capacity by constructing makeshift hospitals, quarantine centers, and clinics; and procuring ventilators and securing funding for ICU units. But these efforts are compromised by the scarcity of medical staff . The government has called upon volunteers to work at state quarantine centers, but mandatory 14-day quarantine and increasing caseloads have stressed volunteers. In addition, some of the quarantine centers are reportedly poorly managed , increasing the transmission risk in centers; 10 percent of the total confirmed cases in the second wave are among health care workers.

Income and food shortages . Myanmar’s economy has been hurt badly by the pandemic, giving rise to income and food insecurity. The sharp decline in remittances due to the pandemic is likely to reduce household income. Eighty percent of Myanmar’s workforce is informal. Scores of day laborers have lost their jobs. Women constitute a majority of the hospitality and garment sectors, so they have been disproportionately affected by factory closures. About 4 out of 5 households reported skipping meals, and others have incurred debt to buy food. The government implemented several measures under the COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP) such as unemployment benefits to registered workers, targeted cash assistance, and a one-time food distribution to households without a regular income. It established a fund of 400 billion kyat (around $309 million) to support garment, tourism, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) via soft loans. Soft loans were also extended to farmers, roadside vendors, and the microfinance sector. But the current cash transfer of MMK40,000 per household translates to a daily income equivalent that is below the poverty line . Besides, the CERP lacks policies that target women who have lost their livelihoods due to the pandemic.

Domestic unrest. Conflict between the government and the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) makes it hard to organize an effective pandemic response. The conflict has led to the displacement of the population as well as the disruption of transport routes and supply chains. In May, the committee that coordinates and collaborates with EAOs to control and treat COVID-19 announced a unilateral ceasefire with EAOs, but the strife between the military and the Arakan Army continues in Rakhine and Chin. As of November 20, Rakhine had the fourth-highest confirmed cases in the country, and they continue to grow. The government has supplied personal protective equipment at campsites for internally displaced persons (IDPs), but congestion and poor living conditions in IDP camps heighten transmission risk.

Solutions: More testing, better quarantine facilities, and critical care in conflict zones

Myanmar is yet to reach the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak, so the full scale of responses to tackle the pandemic is still not clear. But the current state of the pandemic, the government’s responses, and lessons from other countries point to three areas that need attention.

- Increase testing capacity. Myanmar has to build capacity and forge connections with local clinicians and businesses to make affordable testing kits and essential supplies. The state should train nongovernment health care workers to test for COVID-19 and permit nongovernment laboratories to analyze swabs.

- Improve the quarantine facility model. Myanmar might consider incorporating the Fangcang shelter model into new quarantine centers. This model has been proven to provide critical functions of isolation, triage, basic medical care, frequent monitoring, rapid referral, and essential living and social engagement to manage COVID-19 patients effectively.

- Mitigate economic impacts on vulnerable populations. The government is currently drafting the Myanmar Economic Recovery and Reform Plan (MERRP). The plan needs to consider household size, cost of living, and vulnerabilities in determining the transfer amount and frequency. To alleviate food insecurity and circumvent problems related to in-kind distribution, it should include a food allowance in the direct cash transfer. The government also needs to ensure adequate access to loans, grants, or credit to sectors that predominantly employ women.

- Ensure critical health care in conflict regions. The government needs to increase its reach in conflict regions to disseminate vital information on COVID-19. This can best be done by providing more autonomy to Ethnic Health Organizations (EHOs). It needs to improve existing processes for transporting swab samples from the conflict areas to laboratories and regularly exchanging information on testing, contact tracing, and delivery of other essential health services. The government needs to build on the existing cooperation with EHOs and other nonstate actors to plan for large scale vaccination of vulnerable populations in 2021.

- Continue provision of other essential health services. The pandemic has disrupted the provision of other essential health services, including antiretroviral therapy for HIV, the expanded program on immunization, family planning, and maternal health services. The government should seek investments for key health services from public-private partnerships, and international development organizations, increase human resources in the health sector, and consider moving appropriate health services to virtual platforms.

Related Content

Jonathan Stromseth, Thant Myint-U, Fred Dews

December 13, 2019

Massimiliano Cali

November 20, 2020

Myanmar Southeast Asia

Global Economy and Development

Asia & the Pacific Myanmar Southeast Asia

The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.

11:30 am - 12:30 pm EDT

Sudha Ghimire

August 22, 2024

Michael E. O’Hanlon

August 15, 2024

Learn about our mission, our charter and principles, and who we are.

See what triggers an intervention and how supply and logistics allow our teams to respond quickly.

Discover our governance and what it means to be an association. Find a quick visual guide to our offices around the world.

Read through our annual financial and activity reports, and find out about where our funds come from and how they are spent.

Visit this section to get in touch with our offices around the world.

Médecins Sans Frontières brings medical humanitarian assistance to victims of conflict, natural disasters, epidemics or healthcare exclusion.

Learn about how, why, and where MSF teams respond to different diseases around the world, and the challenges we face in providing treatment.

Learn about the different contexts and situations in which MSF teams respond to provide care, including war and natural disaster settings, and how and why we adapt our activities to each.

Learn about our response and our work in depth on specific themes and events.

Where we work

In more than 70 countries, Médecins Sans Frontières provides medical humanitarian assistance to save lives and ease the suffering of people in crisis situations.

MSF Websites

- Czech Republic

- Eastern Africa

- New Zealand

- Philippines

- Russian Federation

- Southern Africa

- South Korea

- Switzerland

Our staff “own” and manage MSF, making sure that we stay true to our mission and principles, through the MSF Associations.

We set up the MSF Access Campaign in 1999 to push for access to, and the development of, life-saving and life-prolonging medicines, diagnostic tests and vaccines for people in our programmes and beyond.

Read stories from our staff as they carry out their work around the world.

Hear directly from the inspirational people we help as they talk about their experiences dealing with often neglected, life-threatening diseases.

Based in Paris, CRASH conducts and directs studies and analysis of MSF actions. They participate in internal training sessions and assessment missions in the field.

Based in Geneva, UREPH (or Research Unit) aims to improve the way MSF projects are implemented in the field and to participate in critical thinking on humanitarian and medical action.

Based in Barcelona, ARHP documents and reflects on the operational challenges and dilemmas faced by the MSF field teams.

Based in Brussels, MSF Analysis intends to stimulate reflection and debate on humanitarian topics organised around the themes of migration, refugees, aid access, health policy and the environment in which aid operates.

This logistical and supply centre in Brussels provides storage of and delivers medical equipment, logistics and drugs for international purchases for MSF missions.

This supply and logistics centre in Bordeaux, France, provides warehousing and delivery of medical equipment, logistics and drugs for international purchases for MSF missions.

This logistical centre in Amsterdam purchases, tests, and stores equipment including vehicles, communications material, power supplies, water-processing facilities and nutritional supplements.

SAMU provides strategic, clinical and implementation support to various MSF projects with medical activities related to HIV and TB. This medical unit is based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Regional logistic centre for the whole East Africa region

BRAMU specialises in neglected tropical diseases, such as dengue and Chagas, and other infectious diseases. This medical unit is based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Our medical guidelines are based on scientific data collected from MSF’s experiences, the World Health Organization (WHO), other renowned international medical institutions, and medical and scientific journals.

Find important research based on our field experience on our dedicated Field Research website.

The Manson Unit is a London, UK-based team of medical specialists who provide medical and technical support, and conduct research for MSF.

Providing epidemiological expertise to underpin our operations, conducting research and training to support our goal of providing medical aid in areas where people are affected by conflict, epidemics, disasters, or excluded from health care.

Evaluation Units have been established in Vienna, Stockholm, and Paris, assessing the potential and limitations of medical humanitarian action, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of our medical humanitarian work.

MSF works with LGBTQI+ populations in many settings over the last 25-30 years. LGBTQI+ people face healthcare disparities with limited access to care and higher disease rates than the general population.

The Luxembourg Operational Research (LuxOR) unit coordinates field research projects and operational research training, and provides support for documentation activities and routine data collection.

The Intersectional Benchmarking Unit collects and analyses data about local labour markets in all locations where MSF employs people.

To upskill and provide training to locally-hired MSF staff in several countries, MSF has created the MSF Academy for Healthcare.

This Guide explains the terms, concepts, and rules of humanitarian law in accessible and reader-friendly alphabetical entries.

The MSF Paediatric Days is an event for paediatric field staff, policy makers and academia to exchange ideas, align efforts, inspire and share frontline research to advance urgent paediatric issues of direct concern for the humanitarian field.

The MSF Foundation aims to create a fertile arena for logistics and medical knowledge-sharing to meet the needs of MSF and the humanitarian sector as a whole.

A collaborative, patients’ needs-driven, non-profit drug research and development organisation that is developing new treatments for neglected diseases, founded in 2003 by seven organisations from around the world.

View Resource Centre

- Responding to COVID-19 during political crisis in Myanmar

Political turmoil and the arrival of COVID-19 has left Myanmar's healthcare system shattered. With 2021 coming to an end, our team on the ground look back at our COVID-19 response, reflecting on what we can be proud of and what we could have done better; the dilemmas, limits and the sometimes-uncomfortable solutions.

Myanmar’s public healthcare system is in disarray. Days after the military seized power on 1 February, medical staff walked out of their jobs, spearheading the civil disobedience movement that saw government employees of all stripes go on strike. Most have not returned. Those on strike who continue to practice in underground clinics risk being attacked and detained by the authorities. At least 28 healthcare professionals have been killed since 1 February, and nearly 90 remain arrested. When Myanmar’s beleaguered public healthcare system met with the COVID-19 outbreak, hospitals were quickly overwhelmed.

Overcrowded crematoriums and empty shelves

As COVID-19 infections peaked, beds in hospitals were often impossible to come by and untold numbers of people were scrambling around towns and cities in Myanmar to source their own supplies of oxygen to administer at home. Crematoriums could not process the bodies fast enough. Routine consultations, surgeries and vaccinations were cancelled while the skeleton medical workforce responded to the outbreak. Panic buying led to empty shelves in pharmacies. Myanmar’s Ministry of Health counts nearly 20,000-recorded deaths from COVID-19 up to the end of 2021 – the fourth highest mortality rate in south-east Asia. But this figure is misleading – only counting people who died in hospitals. Countless individuals passed away in their homes while facilities were full.

How did MSF respond?

We were granted permission to open three independent COVID-19 treatment centres to receive patients with moderate to severe symptoms in Myanmar’s biggest city Yangon, and Kachin state’s Myitkyina and Hpakant townships. Remarkably, while some of us fell seriously ill with the virus, no one on the team lost their life to COVID-19, but many of our family members did. Despite this, we pulled together and looked after each other, working overtime to get the centres up-and-running for people we knew were in urgent need of its services. Although we could not save some patients admitted in very critical condition, some people made remarkable recoveries. One woman living with HIV could barely breathe when she arrived at our facility. But in five days she was off oxygen and could be discharged, making way for another patient. For others, the progress is slow and steady. One 64-year-old woman was in our Myitkyina clinic for 46 days, slowly improving her lung capacity until her oxygen levels were good enough for her to go home.

When there are no acceptable solutions

Our response could have and should have been bigger. While we had permissions to run independent COVID-19 responses in three locations, not all local health authorities were on the same page. We had begun supporting a facility in Lashio, the capital of northern Shan state, on 11 August, but one person within the Lashio healthcare structure ordered us to close it down on 15 August. Days after receiving our first patients, we were forced to transfer six people receiving treatment to the military government’s treatment centre, despite their preference to receive care from MSF.

Did we respond in time?

By the time our first treatment centre was up-and-running in early August, COVID-19 was already devastating the country. If we had been better prepared and more reactive, could we have responded sooner and saved more lives? The answer is an uncomfortable yes. The Delta variant had overwhelmed India and Bangladesh in the months before – two countries that share a 2,000-kilometre border with Myanmar. Its arrival was inevitable. We could have used that time to prepare and equip ourselves, and to have learned from the challenges our colleagues had faced in India where access to oxygen was one of the biggest issues. When the third wave hit, Myanmar was six months into the military takeover. The team was already working at full stretch to maintain existing activities and fill the gaps left in the struggling public healthcare system, in particular taking on thousands of HIV patients from the state’s National AIDS Programme . By the time we initiated our response in the middle of July, we were already on the back foot.

We did not always get it right

There was a belief that we could simply put people on oxygen and save lives. This was not the reality of treating COVID-19 patients. Those who are hospitalised with severe symptoms often have underlying conditions, exacerbating their symptoms and complicating their treatment. We needed essential drugs like insulin and basic cardiovascular medication, but they were not in our warehouse and we could not get them into the country due to convoluted internal processes and difficulties obtaining import permits. We had an emergency preparation kit for COVID-19, but what we had expected to be there was missing, such as medicine to treat blood clots, and the supplies that were included were quickly exhausted.

Committed and ready

Although internal and external constraints and challenges caused difficulties, our COVID-19 facilities are now much more than field clinics – they are excellent hospitals that have saved many lives and will save many more to come. Only around 13 million people in Myanmar are fully vaccinated – around a quarter of the population. If another wave of infections spreads, the public healthcare system risks being overwhelmed once again. With that in mind, we are maintaining our COVID-19 infrastructure and keeping medical staff on-hand should there be another outbreak. Although our supplies of essential medicines have improved, importing them remains an issue. Permissions are currently under more scrutiny than prior to the military takeover, delaying shipments. Furthermore, internal MSF processes and policies for local or regional procurement of medicines have not adapted well to the global supply crisis and often hinder emergency purchases. We have learned many lessons from the challenges we faced the first time round and remain committed and ready to respond to new and unexpected challenges to come.

Lack of a real IP waiver on COVID-19 tools is a disappointing failure for people

“Broken” humanitarian COVID-19 vaccine system delays vaccinations

Vaccinating people with comorbidities in South Africa

- News releases

- Report an incident of misconduct

- Work with us

- ICRC Supply Chain

Myanmar: ICRC strives to ensure ample COVID-19 response

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Protected persons: Internally displaced persons

- Helping detainees

In Myanmar, and many other countries where the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is present, the threat of COVID-19 is particularly acute for communities living in areas affected by armed conflict and other situations of violence, as well as for some particularly vulnerable groups such as internally displaced persons (IDP), people deprived of freedom, or migrants.

In support of the Myanmar government's actions to prevent and mitigate the risks associated with COVID-19, the ICRC, along with the Myanmar Red Cross Society (MRCS) and its other partners from the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, is striving to ensure that people affected by armed conflict and other situations of violence are not left behind, and they receive the assistance and protection to which they are entitled in line with the international humanitarian law.

Between March and mid-June 2020, Myanmar's Ministry of Health and Sports has confirmed over 300 positive COVID-19 cases. Despite the low-infection rate in the country, the ICRC remains concerned for tens of thousands of families affected by armed conflict and violence, including displaced people living in temporary shelters and IDP sites.

In response to these concerns, across the country, the MRCS, as an auxiliary to the public authorities, is providing valuable support to the national COVID-19 response through its network of staff and volunteers activated in 277 townships.

Hygiene kit donation in Myitkyina, Kachin

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) - with the mandate to scale up for disasters and pandemics - is supporting the MRCS through the international mobilization of financial, technical and logistics resources.

For the ICRC, ongoing programmes have been swiftly adapted to the new realities of the virus in order to ensure the continuity of life-saving activities such as food distributions, or the evacuations of weapon-wounded civilians in areas affected by conflict.

At the same time, in coordination with the relevant authorities and the MRCS, the ICRC rapidly developed a wide range of COVID-19-prevention activities in the areas of health care, water and habitat, or protection.

The ICRC has also engaged non-state armed groups, ethnic health organizations, religious leaders and local media to provide assistance and convey COVID-19 prevention messages to communities.

Lashio prison donation

The ICRC also considers that special attention is required for prison populations who face a higher risk of contamination when facilities are overcrowded, have poor hygiene, or lack ventilation. The ICRC supported prison authorities for prevention and infection control in detention facilities, as well as the organization of the safe return home of 2,500 detainees released following the annual presidential pardon.

ICRC COVID-19 response in Myanmar from ICRC on Vimeo .

Our teams are working to improve living conditions in existing and new IDP sites by improving basic shelter, access to safe water, and building basic latrines for better hygiene.

The ICRC plans to adjust its economic security programmes to contribute to addressing these gaps in the coming months, whether through cash programming or covering basic humanitarian needs, so that those who are most affected and exposed to the impacts of COVID-19 are less vulnerable.

"In the new context of COVID-19, it remains a top priority for the ICRC to continue protecting and assisting people affected by armed conflict and violence while reminding all parties of their obligation, under the International Humanitarian Law, to ensure access to health care to all communities," explains Stephan Sakalian, resident representative for the ICRC in Myanmar.

"It is the responsibility of everyone to act when faced with such a global and far-reaching crisis."

Sittwe prison donation

"We also need to join the efforts of the authorities, Myanmar Red Cross Society, civil society and the whole humanitarian and development community to prevent and mitigate the risks associated with COVID-19 in Myanmar. It is the responsibility of everyone to act when faced with such a global and far-reaching crisis," he added.

"It is the responsibility of everyone to act when faced with such a global and far-reaching crisis"

Myanmar: ICRC Response to COVID-19 in 2020

Related articles.

Lebanon: ICRC on the ground

Azerbaijan: Activity highlights for the first half of 2024

What does the law say about the responsibilities of the Occupying Power in the occupied Palestinian territory?

Myanmar: COVID-19 third wave has hit like a ‘tsunami’, warns WFP

Facebook Twitter Print Email

The World Food Programme ( WFP ) warned on Friday that it is facing a 70 per cent funding shortfall in Myanmar, where millions face growing food insecurity.

Amid the “triple impact of poverty, the current political unrest and economic crisis”, coupled with the rapidly spreading third wave of COVID-19 , that is “practically like a tsunami that’s hit this country”, the people of Myanmar are “experiencing the most difficult moment in their lives ”, WFP Myanmar Country Director Stephen Anderson said, from Nay Pyi Taw.

Hunger doubles

WFP needs $86 million to help fight hunger in the country over the next six months, amid turmoil since the military ousted the elected government led by Aung San Suu Kyi on 1 February.

World Food Programme

In April, the UN agency estimated that the number of people facing hunger could more than double to 6.2 million in the next six months, up from 2.8 million prior to February.

Subsequent monitoring surveys carried out by WFP have shown that since February, more and more families are being pushed to the edge, struggling to put even the most basic food on the table.

“We have seen hunger spreading further and deeper in Myanmar. Nearly 90 per cent of households living in slum-like settlements around Yangon say they have to borrow money to buy food ; incomes have been badly affected for many,” said Mr Anderson.

Tripling in support

In response, the WFP tripled its planned support to the country and starting in May, launched a new urban food response, targeting 2 million people in Yangon and Mandalay, Myanmar’s two biggest cities.

The majority of people to receive assistance are mothers, children, people with disabilities and the elderly. To date, 650,000 people have been assisted in urban areas .

At the same time, the WFP is “stepping up its operations” to reach newly displaced people affected by the clashes and insecurity in recent months. More than 220,000 people have fled violence since February, and are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance.

WFP has reached 17,500 newly displaced people and is working to assist more in August.

In total, 1.25 million people in Myanmar have received WFP food, cash and nutrition assistance in 2021 across urban and rural areas, including 360,000 food-insecure people in Rakhine, Kachin and Shan states, where there have been longstanding concerns.

Access critical

However, with $86 million more required over the next six months, it is uncertain how far these operations can go.

“It is critically important for us to be able to access to all those in need and receive the funding to provide them with humanitarian assistance,” Anderson explained. “ Now more than ever, the people of Myanmar need our support ,” he added.

Licence or Product Purchase Required

You have reached the limit of premium articles you can view for free.

Already have an account? Login here

Get expert, on-the-ground insights into the latest business and economic trends in more than 30 high-growth global markets. Produced by a dedicated team of in-country analysts, our research provides the in-depth business intelligence you need to evaluate, enter and excel in these exciting markets.

View licence options

Suitable for

- Executives and entrepreneurs

- Bankers and hedge fund managers

- Journalists and communications professionals

- Consultants and advisors of all kinds

- Academics and students

- Government and policy-research delegations

- Diplomats and expatriates

How is Covid-19 transforming Myanmar’s digital economy?

Covid-19 has shaken up the development of the digital economy in Myanmar, with the pandemic leading to a rise in demand for home broadband in this traditionally mobile-first market.

As various containment measures were imposed, companies located in the main business hubs scrambled to ensure that employees were able to work remotely .

“Household broadband demand increased because businesses were afraid that their workers would not be connected. We have very good mobile coverage in Myanmar, but this system is not designed for working from home for 10 hours per day,” Shane Thu Aung, co-founder and chairman of the Yangon-based Global Technology Group – which includes high-speed broadband service 5BB – told OBG.

In addition to simply improving internet connectivity in the home, virus-related disruptions have also seen companies look to different products to enable a smooth transition for those working remotely .

In particular, cloud services are being utilised to help cope with spikes in data demand.

“Almost all companies are now using video conferencing tools, and they have also explored cloud services so they can access their work systems from home,” Aung said. “They need to connect through the cloud due to heavy user traffic. Most government and private sector applications are also going over to the cloud.”

Aside from a shift towards home broadband in a country that has traditionally focused on developing strong mobile internet connectivity, businesses have also sought to adapt to increased demand for digital payments – further accelerating the demand for internet services.

In order to avoid cash transactions, a number of restaurants and shops have pivoted towards e-commerce platforms.

These shifts in consumer demand and behaviour have led to fresh investment in the sector, with Singapore-registered, Myanmar-focused Ascent Capital Partners committing $26m to local internet service provider Frontiir.

The funding, announced in late June, will help Frontiir expand its internet services across the country. The company currently serves 1.6m consumers across 360,000 households in four states and regions.

In addition to this investment, Ascent Capital Partners has also set aside additional financing towards mitigating the economic fallout of the virus in Myanmar.

Government-driven digital expansion

The increased uptake of digital products and platforms has also been supported by Myanmar’s post-pandemic recovery strategy.

Among the seven goals that comprise its Covid-19 Economic Relief Plan, announced in late April, the government prioritised the promotion of “innovative products and platforms”.

This includes encouraging the use of mobile payment services, bank transfers and card payments for e-commerce sales, as well as increasing the uptake of e-commerce options among businesses.

Such measures will build on previous efforts to improve the country’s ICT infrastructure and connectivity, which in recent years have focused on liberalising the industry and incentivising private investors.

In terms of internet coverage, the country’s Myanmar Digital Economy Roadmap aims to increase internet penetration from 40% in 2019 to 50% by 2025.

However, much of this coverage stems from mobile internet, with fixed broadband penetration still in the single digits, indicating significant room for further growth.

Cybersecurity in the spotlight

While the virus spurred plans to upgrade ICT infrastructure amid the increased uptake of digital platforms and services, there are nevertheless some concerns about the country’s capacity to legislate for the digital transformation.

“Many small businesses are considering how to digitalise their businesses, including trade and import procedures. However, regulations do not really reflect this, particularly for trade and Customs,” Aung told OBG. “Some government officials are responsive to the need for change, but more needs to be done. If Myanmar’s laws do not reflect these changes we will fall behind. There is a time gap and Myanmar is losing its advantage.”

One particular area of concern amid the rapid shift online is that of data protection, with fears that many companies may be unprepared to address cyber risks.

The government has been working on developing a dedicated cybersecurity law since 2018, and while there have been efforts to increase awareness through the opening of the National Cybersecurity Centre, some believe the country remains exposed to a significant level of threat.

“Suddenly everyone is worried about data security, and the government is alarmed about data classification and storage. This shows the need for a comprehensive cybersecurity law,” Aung said.

Request Reuse or Reprint of Article

Read More from OBG

Construction – and infrastructure development in particular – is expected to be a key driver of economic growth across ASEAN from 2021. The bloc, home to some of the world’s fastest-growing economies and lowest unemployment rates, faced the novel coronavirus after years of health care infrastructure improvements, with much of the group reporting Covid-19 case-fatality rates below the global mean in 2020.

Report: Oman’s digital economy and its transformative potential Oman's digital transformation is revolutionising its economy and society. With the National Programme for Digital Economy driving progress, the country is bolstering its telecommunications infrastructure, expanding e-government services, developing a competitive space industry and embracing cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI). This report provides insights into Oman's digital journey, highlighting advancements in connectivity, AI innovation, cybersecurity a…

Informe: Corredor Interoceánico de México como alternativa al Canal de Panamá In English El Corredor Interoceánico de México y el complejo industrial de Texistepec están emergiendo como un nodo de desarrollo clave que conecta el Océano Pacífico y el Océano Atlántico, y como un centro para el transporte y el comercio internacional. El corredor, que abarca 300 km y une dos de los principales puertos del país, ofrece importantes oportunidades para el desarrollo económico en las regiones menos desarrolladas del sur y sureste de México. Este informe, e…

Register for free Economic News Updates on Myanmar

“high-level discussions are under way to identify how we can restructure funding for health care services”, related content.

Featured Sectors in Myanmar

- Myanmar Agriculture

- Myanmar Banking

- Myanmar Construction

- Myanmar Cybersecurity

- Myanmar Digital Economy

- Myanmar Economy

- Myanmar Education

- Myanmar Energy

- Myanmar Environment

- Myanmar Financial Services

- Myanmar Health

- Myanmar ICT

- Myanmar Industry

- Myanmar Insurance

- Myanmar Legal Framework

- Myanmar Logistics

- Myanmar Media & Advertising

- Myanmar Real Estate

- Myanmar Retail

- Myanmar Safety and Security

- Myanmar Saftey and ecurity

- Myanmar Tax

- Myanmar Tourism

- Myanmar Transport

Featured Countries in ICT

Popular Sectors in Myanmar

Popular Countries in ICT

- Indonesia ICT

- The Philippines ICT

- Saudi Arabia ICT

- UAE: Abu Dhabi ICT

Featured Reports in Myanmar

Recent Reports in Myanmar

- The Report: Myanmar 2020

- The Report: Myanmar 2019

- The Report: Myanmar 2018

- The Report: Myanmar 2017

- The Report: Myanmar 2016

- The Report: Myanmar 2015

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Myanmar’s Economy Severely Impacted by COVID-19: Report

YANGON, June 25, 2020 – The global COVID-19 pandemic is dealing a severe blow to Myanmar’s economy. Economic growth in a baseline scenario is projected to drop from 6.8 percent in FY18/19 to just 0.5 percent in FY2019/20, according to the World Bank’s Myanmar Economic Monitor , released today.

If the pandemic is protracted, the economy could contract by as much as 2.5 percent in FY2019/20, with the expected recovery in 2020/21 subject to further downside risks.

The slowing economic growth threatens to partially reverse Myanmar’s recent progress in poverty reduction while reducing the incomes of households that are already poor. Under the baseline scenario, in which the domestic spread of the coronavirus is brought under control, the global economy swiftly recovers, and Myanmar’s GDP growth rate is projected to bounce back to 7.2 percent in FY2020/21, poverty rates would increase in the short term and will not return to pre-crisis levels until FY2021/22. Under the downside scenario, poverty rates would remain above their pre-crisis level until at least FY2022/23.

The report also looks at the Myanmar government’s response to the crisis through the COVID-19 fund and Economic Relief Plan (CERP), which includes measures to offer relief and initiate a resilient recovery - including tax relief, credit for businesses, food and cash to households, as well as policies to facilitate trade and investment.

“At the moment the medium-term outlook for Myanmar’s economy is positive, but there are significant downside risks due to the unpredictable evolution of the pandemic. Robust policy actions are urgently needed. It will be important for the government to boost the effectiveness of the CERP by ensuring flexibility in spending targets, extending support to smaller enterprises and ensuring all poor households can benefit from the plan,” said Mariam Sherman, World Bank Country Director for Myanmar, Cambodia and Lao PDR.

The report highlights that the effects of the crisis are not being evenly felt across sectors. Industrial production is expected to contract by 0.2 percent in FY2019/20 as lockdown measures restrict access to labor, the closure of the overland border with China disrupts the supply of industrial inputs, and consumer demand—both domestic and international—remains soft. Precautionary behavior and travel bans continue to negatively impact wholesale and retail trade, tourism-related services, and transportation. Due to the ongoing disruption of supply chains and weakening external demand, exports are expected to remain weak over the rest of the fiscal year. Tax revenues are projected to decline by 6.0 percent, year-on-year, in FY2019/20.

Meanwhile the agriculture sector has so far proven to be more resilient, and the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) sector is experiencing a surge of activity driven by a sharp increase in telecommuting and e-commerce. Falling consumer demand under COVID-19 is moderating inflation.

The Myanmar Economic Monitor is a biannual analysis of economic developments, economic prospects and policy priorities in Myanmar. The publication draws on available data reported by the Government of Myanmar and additional information collected as part of the World Bank Group’s regular economic monitoring and policy dialogue.

- Press release (Burmese)

- Key findings: Myanmar Economic Monitor June 2020

- Video: The Impact of COVID-19 on Myanmar's Economy

- Download report

- Executive summary

- Presentation (ppt)

- Myanmar COVID-19 Monitoring Platform

- Myanmar Economic Monitors

- Full launch video

Myanmar: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile

Research and data: Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Daniel Gavrilov, Charlie Giattino, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Saloni Dattani, Diana Beltekian, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, and Max Roser

- Coronavirus

- Data explorer

- Hospitalizations

Vaccinations

- Mortality risk

- Excess mortality

- Policy responses

Build on top of our work freely

- All our code is open-source

- All our research and visualizations are free for everyone to use for all purposes

Select countries to show in all charts

Confirmed cases.

- What is the daily number of confirmed cases?

- Daily confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

- What is the cumulative number of confirmed cases?

- Cumulative confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

- Biweekly cases : where are confirmed cases increasing or falling?

- Global cases in comparison: how are cases changing across the world?

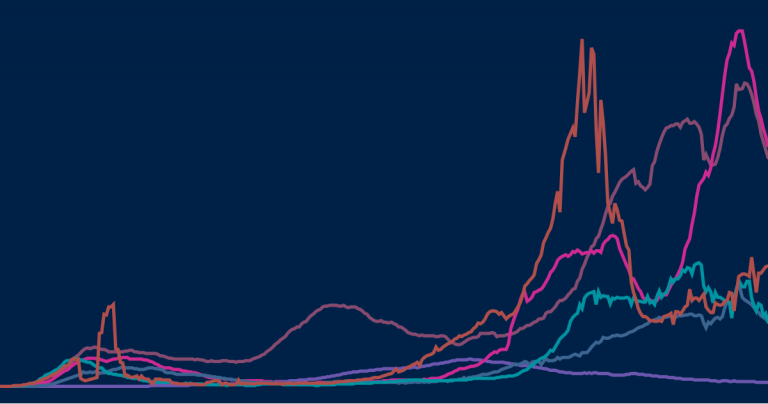

Myanmar: What is the daily number of confirmed cases?

Related charts:.

Which world regions have the most daily confirmed cases?

This chart shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per day . This is shown as the seven-day rolling average.

What is important to note about these case figures?

- The reported case figures on a given date do not necessarily show the number of new cases on that day – this is due to delays in reporting.

- The number of confirmed cases is lower than the true number of infections – this is due to limited testing. In a separate post we discuss how models of COVID-19 help us estimate the true number of infections .

→ We provide more detail on these points in our page on Cases of COVID-19 .

Five quick reminders on how to interact with this chart

- By clicking on Edit countries and regions you can show and compare the data for any country in the world you are interested in.

- If you click on the title of the chart, the chart will open in a new tab. You can then copy-paste the URL and share it.

- You can switch the chart to a logarithmic axis by clicking on ‘LOG’.

- If you move both ends of the time-slider to a single point you will see a bar chart for that point in time.

- Map view: switch to a global map of confirmed cases using the ‘MAP’ tab at the bottom of the chart.

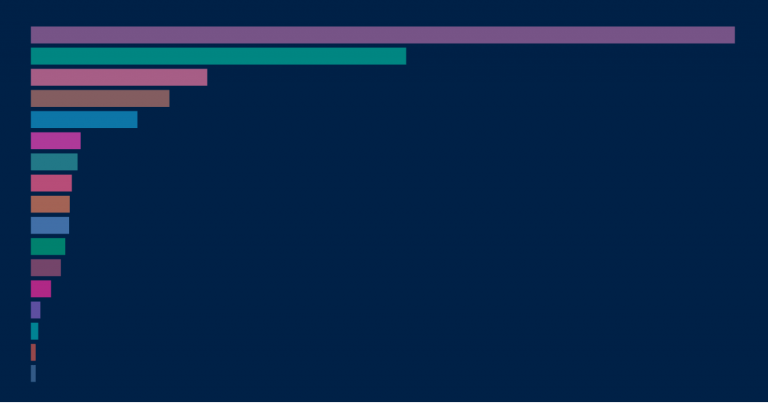

Myanmar: Daily confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

Differences in the population size between different countries are often large. To compare countries, it is insightful to look at the number of confirmed cases per million people – this is what the chart shows.

Keep in mind that in countries that do very little testing the actual number of cases can be much higher than the number of confirmed cases shown here.

Three tips on how to interact with this map

- By clicking on any country on the map you see the change over time in this country.

- By moving the time slider (below the map) you can see how the global situation has changed over time.

- You can focus on a particular world region using the dropdown menu to the top-right of the map.

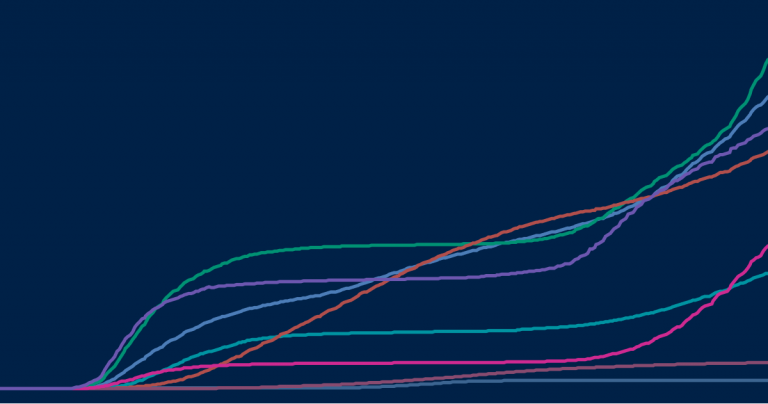

Myanmar: What is the cumulative number of confirmed cases?

Which world regions have the most cumulative confirmed cases?

How do the number of tests compare to the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases?

The previous charts looked at the number of confirmed cases per day – this chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed cases since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In all our charts you can download the data

We want everyone to build on top of our work and therefore we always make all our data available for download. Click on the ‘Download’-tab at the bottom of the chart to download the shown data for all countries in a .csv file.

Myanmar: Cumulative confirmed cases: how do they compare to other countries?

This chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed cases per million people.

Myanmar: Biweekly cases : where are confirmed cases increasing or falling?

Why is it useful to look at biweekly changes in confirmed cases.

For all global data sources on the pandemic, daily data does not necessarily refer to the number of new confirmed cases on that day – but to the cases reported on that day.

Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of cases – it is helpful to look at a longer time span that is less affected by the daily variation in reporting. This provides a clearer picture of where the pandemic is accelerating, staying the same, or reducing.

The first map here provides figures on the number of confirmed cases in the last two weeks. To enable comparisons across countries it is expressed per million people of the population.

And the second map shows the percentage change (growth rate) over this period: blue are all those countries in which the case count in the last two weeks was lower than in the two weeks before. In red countries the case count has increased.

What is the weekly number of confirmed cases?

What is the weekly change (growth rate) in confirmed cases?

Myanmar: Global cases in comparison: how are cases changing across the world?

In our page on COVID-19 cases , we provide charts and maps on how the number and change in cases compare across the world.

Confirmed deaths

- What is the daily number of confirmed deaths?

- Daily confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

- What is the cumulative number of confirmed deaths?

- Cumulative confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

- Biweekly deaths : where are confirmed deaths increasing or falling?

- Global deaths in comparison: how are deaths changing across the world?

Myanmar: What is the daily number of confirmed deaths?

Which world regions have the most daily confirmed deaths?

This chart shows t he number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths per day .

Three points on confirmed death figures to keep in mind

All three points are true for all currently available international data sources on COVID-19 deaths:

- The actual death toll from COVID-19 is likely to be higher than the number of confirmed deaths – this is due to limited testing and challenges in the attribution of the cause of death. The difference between confirmed deaths and actual deaths varies by country.

- How COVID-19 deaths are determined and recorded may differ between countries.

- The death figures on a given date do not necessarily show the number of new deaths on that day, but the deaths reported on that day. Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of deaths – it is helpful to view the seven-day rolling average of the daily figures as we do in the chart here.

→ We provide more detail on these three points in our page on Deaths from COVID-19 .

Myanmar: Daily confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

This chart shows the daily confirmed deaths per million people of a country’s population.

Why adjust for the size of the population?

Differences in the population size between countries are often large, and the COVID-19 death count in more populous countries tends to be higher . Because of this it can be insightful to know how the number of confirmed deaths in a country compares to the number of people who live there, especially when comparing across countries.

For instance, if 1,000 people died in Iceland, out of a population of about 340,000, that would have a far bigger impact than the same number dying in the United States, with its population of 331 million. 1 This difference in impact is clear when comparing deaths per million people of each country’s population – in this example it would be roughly 3 deaths/million people in the US compared to a staggering 2,941 deaths/million people in Iceland.

Myanmar: What is the cumulative number of confirmed deaths?

Which world regions have the most cumulative confirmed deaths?

The previous charts looked at the number of confirmed deaths per day – this chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed deaths since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Myanmar: Cumulative confirmed deaths: how do they compare to other countries?

This chart shows the cumulative number of confirmed deaths per million people.

Myanmar: Biweekly deaths : where are confirmed deaths increasing or falling?

Why is it useful to look at biweekly changes in deaths.

For all global data sources on the pandemic, daily data does not necessarily refer to deaths on that day – but to the deaths reported on that day.

Since reporting can vary significantly from day to day – irrespectively of any actual variation of deaths – it is helpful to look at a longer time span that is less affected by the daily variation in reporting. This provides a clearer picture of where the pandemic is accelerating, staying the same, or reducing.

The first map here provides figures on the number of confirmed deaths in the last two weeks. To enable comparisons across countries it is expressed per million people of the population.

And the second map shows the percentage change (growth rate) over this period: blue are all those countries in which the death count in the last two weeks was lower than in the two weeks before. In red countries the death count has increased.

What is the weekly number of confirmed deaths?

What is the weekly change (growth rate) in confirmed deaths?

Myanmar: Global deaths in comparison: how are deaths changing across the world?

In our page on COVID-19 deaths , we provide charts and maps on how the number and change in deaths compare across the world.

- How many COVID-19 vaccine doses are administered daily ?

- How many COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in total ?

- What share of the population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine?

- What share of the population has completed the initial vaccination protocol ?

- Global vaccinations in comparison: which countries are vaccinating most rapidly?

Myanmar: How many COVID-19 vaccine doses are administered daily ?

How many vaccine doses are administered each day (not population adjusted)?

This chart shows the daily number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people in a given population . This is shown as the rolling seven-day average. Note that this is counted as a single dose, and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific dose regime (e.g., people receive multiple doses).

Myanmar: How many COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in total ?

How many vaccine doses have been administered in total (not population adjusted)?

This chart shows the total number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people within a given population. Note that this is counted as a single dose, and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific dose regime as several available COVID vaccines require multiple doses.

Myanmar: What share of the population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine?

How many people have received at least one vaccine dose?

This chart shows the share of the total population that has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. This may not equal the share with a complete initial protocol if the vaccine requires two doses. If a person receives the first dose of a 2-dose vaccine, this metric goes up by 1. If they receive the second dose, the metric stays the same.

Myanmar: What share of the population has completed the initial vaccination protocol ?

How many people have completed the initial vaccination protocol?

The following chart shows the share of the total population that has completed the initial vaccination protocol. If a person receives the first dose of a 2-dose vaccine, this metric stays the same. If they receive the second dose, the metric goes up by 1.

This data is only available for countries which report the breakdown of doses administered by first and second doses.

Myanmar: Global vaccinations in comparison: which countries are vaccinating most rapidly?

In our page on COVID-19 vaccinations, we provide maps and charts on how the number of people vaccinated compares across the world.

Testing for COVID-19

- The positive rate

- The scale of testing compared to the scale of the outbreak

- How many tests are performed each day ?

- Global testing in comparison: how is testing changing across the world?

Myanmar: The positive rate

Here we show the share of reported tests returning a positive result – known as the positive rate.

The positive rate can be a good metric for how adequately countries are testing because it can indicate the level of testing relative to the size of the outbreak. To be able to properly monitor and control the spread of the virus, countries with more widespread outbreaks need to do more testing.

It can also be helpful to think of the positive rate the other way around:

How many tests have countries done for each confirmed case in total across the outbreak?

Myanmar: The scale of testing compared to the scale of the outbreak

How do daily tests and daily new confirmed cases compare when not adjusted for population ?

This scatter chart provides another way of seeing the extent of testing relative to the scale of the outbreak in different countries.

The chart shows the daily number of tests (vertical axis) against the daily number of new confirmed cases (horizontal axis), both per million people.

Myanmar: How many tests are performed each day ?

This chart shows the number of daily tests per thousand people. Because the number of tests is often volatile from day to day, we show the figures as a seven-day rolling average.

What is counted as a test?

The number of tests does not refer to the same thing in each country – one difference is that some countries report the number of people tested, while others report the number of tests (which can be higher if the same person is tested more than once). And other countries report their testing data in a way that leaves it unclear what the test count refers to exactly.

We indicate the differences in the chart and explain them in detail in our accompanying source descriptions .

Myanmar: Global testing in comparison: how is testing changing across the world?

In our page on COVID-19 testing , we provide charts and maps on how the number and change in tests compare across the world.

Case fatality rate

- What does the data on deaths and cases tell us about the mortality risk of COVID-19?

- The case fatality rate

- Learn in more detail about the mortality risk of COVID-19

Myanmar: What does the data on deaths and cases tell us about the mortality risk of COVID-19?

To understand the risks and respond appropriately we would also want to know the mortality risk of COVID-19 – the likelihood that someone who is infected with the disease will die from it.

We look into this question in more detail on our page about the mortality risk of COVID-19 , where we explain that this requires us to know – or estimate – the number of total cases and the final number of deaths for a given infected population.

Because these are not known , we discuss what the current data on confirmed deaths and cases can and can not tell us about the risk of death. This chart shows both those metrics.

Myanmar: The case fatality rate

Related chart:.

How do the cumulative number of confirmed deaths and cases compare?

The case fatality rate is simply the ratio of the two metrics shown in the chart above.

The case fatality rate is the number of confirmed deaths divided by the number of confirmed cases.

This chart here plots the CFR calculated in just that way.

During an outbreak – and especially when the total number of cases is not known – one has to be very careful in interpreting the CFR . We wrote a detailed explainer on what can and can not be said based on current CFR figures.

Myanmar: Learn in more detail about the mortality risk of COVID-19

Learn what we know about the mortality risk of COVID-19 and explore the data used to calculate it.

Government Responses

- Government Stringency Index

To understand how governments have responded to the pandemic, we rely on data from the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), which is published and managed by researchers at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford.

This tracker collects publicly available information on 17 indicators of government responses, spanning containment and closure policies (such as school closures and restrictions in movement); economic policies; and health system policies (such as testing regimes).

How have countries responded to the pandemic?

Travel bans, stay-at-home restrictions, school closures – how have countries responded to the pandemic? Explore the data on all policy measures.

Myanmar: Government Stringency Index

The chart here shows how governmental response has changed over time. It shows the Government Stringency Index – a composite measure of the strictness of policy responses.

The index on any given day is calculated as the mean score of nine policy measures, each taking a value between 0 and 100. See the authors’ full description of how this index is calculated.

A higher score indicates a stricter government response (i.e. 100 = strictest response).

The OxCGRT project calculates this index using nine specific measures, including:

- school and workplace closures;

- restrictions on public gatherings;

- transport restrictions;

- and stay-at-home requirements.

You can see all of these separately on our page on policy responses . There you can also compare these responses in countries across the world.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- Get involved

Seven simple steps to protect yourself and others from COVID-19

March 10, 2020.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is the infectious disease caused by the most recently discovered coronavirus. Most people who become infected experience mild illness and recover, but it can be more severe for others, particularly older people and those with underlying medical conditions. Here are some simple steps you can take to protect your health and the health of other people.

Everyone can follow these recommendations, but they are particularly important if you are in an area where people are known to have COVID-19.

1. Wash your hands frequently

Regularly and thoroughly clean your hands with an alcohol-based hand rub or wash them with soap and water.

Why? We frequently use our hands to touch objects and surfaces that may be contaminated. Without realizing it, we then touch our faces, transferring viruses to our eyes, nose and mouth where they can infect us. Washing your hands with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand rub kills viruses that may be on your hands — including the virus that causes COVID-19.

2. Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth

We often touch our faces without noticing it. Be aware of this, and avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

Why? Hands touch many surfaces and can pick up viruses. Once contaminated, hands can transfer the virus to your eyes, nose or mouth and can then enter your body and make you sick.

3. Cover your cough

Make sure that you, and the people around you, follow good respiratory hygiene. This means covering your mouth and nose with the bend of your elbow or with a tissue when you cough or sneeze. Dispose of the used tissue immediately into a closed bin and wash your hands.

Why? When someone coughs or sneezes they spray small liquid droplets from their nose or mouth which may contain virus. By covering your cough or sneeze you avoid spreading viruses and other germs to other people. By using the bend of your elbow or a tissue and not your hands to cover your cough or sneeze, you avoid transferring contaminated droplets to your hands. This prevents you from contaminating a person or a surface through touching them with your hands.

4. Avoid crowded places and close contact with anyone that has fever or cough

Avoid crowded places, especially if you are over 60 or have an underlying health condition such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart and lung diseases or cancer. Maintain at least 1 metre of distance between yourself and anyone who has a fever or cough.

Why? COVID-19 spreads mainly by respiratory droplets that come out of the mouth or nose when a person who has the disease coughs. By avoiding crowded places, you keep yourself distant (at least 1 metre) from people who may be infected with COVID-19 or any other respiratory disease.

5. Stay at home if you feel unwell

Stay at home if you feel unwell, even with a slight fever and cough.

Why? By staying home and not going to work or other places, you will recover faster and will avoid transmitting diseases to other people.

6. If you have a fever, cough and difficulty breathing, seek medical care early — but call first

If you have a fever, cough and difficulty breathing, seek medical care early — if you can, call your hospital or health centre first so that they can tell you where you should go.

Why? This will help to make sure you get the right advice, are directed to the right health facility, and will prevent you from infecting others.

7. Get information from trusted sources

Stay informed about the latest information from about about COVID-19 from trusted sources. Make sure your information comes from reliable sources — your local or national public health agency, the World Health Organization (WHO) website, or your local health professional. Everyone should know the symptoms — for most people, it starts with a fever and a dry cough.

Why? Local and national authorities will have the most up-to-date information on whether COVID-19 is spreading in your area. They are best placed to advise on what people in your area should be doing to protect themselves. For more information from WHO, visit:

- WHO COVID-19 main page

- Advice for the public

- When and how to use masks

- COVID-19 myth-busters

- Q&A videos

- Travel advice

- Training and e-learning

Related Content

Publications

Mired in uncertainty: the trend of high frequency indicators in myanmar (december 2021-january 2022).

The Myanmar military's 1 February coup d’état exacerbated the already challenging economic situation in the country that had been driven by the COVID-19 pandemic....

Impact of the twin crises on human welfare in Myanmar

The report details the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and February 2021 coup d’état in Myanmar. It builds on the report released by UNDP in early April this year...

COVID-19, coup d'état and poverty: compounding negative shocks and their impact on human development in Myanmar

This report presents UNDP research findings and analysis of data collected prior and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Myanmar on the socioeconomic impacts of both ...

Household Vulnerability Survey 2020

The COVID 19 pandemic is having significant and, probably, lasting consequences on the Myanmar economy. The effects of the pandemic have resonated well beyond the...

The Critical Value of PPE in Myanmar’s Mon State

To cope with the situation, Mon State has been working with the UN Development Programme, to try to control the spread of the virus through an Awareness Raising a...

- Myanmar’s Crisis & the World

- Ethnic Issues

- War Against the Junta

- Junta Cronies

- Conflicts In Numbers

- Junta Watch

- Investigation

- Myanmar-China Watch

- Guest Column

Myanmar’s Third Wave of COVID-19 Spreads to Almost 90% of Townships

A charity organizing funerals for COVID-19 patients at a cemetery in Kale, Sagaing Region. / CJ

Nearly 90 percent of the country has been affected by Myanmar’s third wave of coronavirus infections, with 296 of 330 townships nationwide reporting COVID-19 cases since May.

Addressing a meeting on COVID-19 prevention and control measures on Friday, coup leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing admitted that “the current infection [outbreak] in Myanmar is serious” and was spreading faster than the first and second waves of the coronavirus epidemic in Myanmar.

“If necessary, restrictions should be tightened so the people strictly follow the orders related to COVID-19,” he said.

The junta’s Health Ministry said in mid-June that three mutant strains of the coronavirus have been detected in Myanmar, including the Delta strain, which was first detected in India.

On Friday, Myanmar reported 64 fatalities—the highest death toll since the military coup in February—and 4,320 new COVID-19 cases, after testing 15,747 swab samples, according to the ministry.

As of Friday, Myanmar had reported a total of 184,375 COVID-19 cases with 3,685 deaths.

On Thursday, regime-controlled television announced that all schools, including private and monastic schools, will be closed until July 23. The regime reopened schools on June 1 after they had been shuttered for more than a year under the ousted civilian government due to the pandemic.

Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing added that the regime had an agreement with China to buy 5 million doses of vaccines, while Russia was planning to deliver the first batch of 2 million doses purchased from the country.

Additionally, the junta leader said the regime would “arrange for Myanmar Pharmaceutical Industry to manufacture the vaccines” with support from Russia, which has promised to provide technical help on vaccine production.

Myanmar reported its first cases of COVID-19 in March last year, and a second wave followed in August. In both outbreaks, public participation was huge, with healthcare professionals and volunteers at the forefront of measures to prevent and contain the disease.

After Myanmar experienced a second wave of COVID-19 in August last year, the National League for Democracy government began to implement a nationwide vaccination program on Jan. 27, days before the military coup on Feb. 1. Health-care staff and volunteer medical workers were the first to receive shots of the AstraZeneca vaccine donated by India.

In defiance of military rule, thousands of healthcare professionals are taking part in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and refusing to work for the military regime.

COVID-19 testing declined from between about 16,000 and 18,000 swab tests a day in January under the ousted NLD civilian government to fewer than 2,000 per day between February and early June. Swab testing increased again in late June, with over 8,000 tests conducted.

The military regime has imposed stay-at-home orders in 45 townships: three in Sagaing Region; five in Chin State; seven in Bago Region; eight in Mandalay Region; three in Shan State; three in Ayeyarwady Region; two in Naypyitaw; Gangaw in Magwe Region; three in Mon State; and 10 in Yangon Region.

You may also like these stories:

Related Posts

Restoring Ancient City as Regime Crumbles; Building a Mutiny; and More

Myanmar Junta to Double Electricity Rates

China Discusses Military Training with Myanmar Junta

Nearly 1,200 coronavirus-positive myanmar workers in thailand’s tak need help, groups say.

Myanmar Border Town Locked Down by KIA as New COVID-19 Infections Emerge

The Coup China Saw Coming in Myanmar—and Failed to Stop

Silence on Coup Makes Strategic Sense for Myanmar’s Wa

The irrawaddy, similar picks:.

Exodus: Tens of Thousands Flee as Myanmar Junta Troops Face Last Stand in Kokang

Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army troops are opening roads and pathways through forests for people to flee Kokang’s capital as...

Enter the Dragon, Exit the Junta: Myanmar’s Brotherhood Alliance makes Chinese New Year Vow

Ethnic armed grouping says it will continue Operation 1027 offensive until goal of ousting the junta is achieved.

Drone Attack at Myanmar-China Border Gate Causes Over $14m in Losses

Jin San Jiao is latest northern Shan State trade hub in crosshairs of ethnic Brotherhood Alliance.

Arakan Army Captures Myanmar Junta Brigade General in Chin State Rout: Report

Rakhine-based armed group has reportedly detained the chief of 19th Military Operations Command after seizing his base in Paletwa Township.

Brotherhood Alliance Marching Towards Capital of Myanmar’s Kokang Region

Chinese embassy urges citizens to flee Laukkai Town as ethnic armies prepare to drive Myanmar junta troops from Kokang’s capital.

Myanmar Junta Arrests Thai Condo Buyers, Realtors as Currency Crashes

Monday’s arrests follow reports that Myanmar has become one of Thailand’s most lucrative markets for selling condos since the 2021...

Myanmar Suffering From Severe Shortage of Medical Oxygen as COVID-19 Cases Spike

Recommended

Wang Yi Embraced a Pariah in Myanmar: It Will Only Backfire

Increasingly Frantic Recruitment Methods Point to Myanmar Junta’s Frailty

French aircraft are abetting war crimes in myanmar: report, tnla reportedly captures two more junta bases in shan state’s nawnghkio, myanmar junta forces push back in kachin’s bhamo after losing battalion hq, get the irrawaddy’s latest news, analyses and opinion pieces on myanmar in your inbox..

Subscribe here for daily updates.

- Myanmar’s Crisis & the World

- Junta Crony

- Election 2020

- Elections in History

- Myanmar Diary

- Women & Gender

- Places in History

- On This Day

- From the Archive

- Myanmar & COVID-19

- Intelligence

- Fashion & Design

- Photo Essay

About The Irrawaddy

Founded in 1993 by a group of Myanmar journalists living in exile in Thailand, The Irrawaddy is a leading source of reliable news, information, and analysis on Burma/Myanmar and the Southeast Asian region. From its inception, The Irrawaddy has been an independent news media group, unaffiliated with any political party, organization or government. We believe that media must be free and independent and we strive to preserve press freedom.

- Code of Ethics

- Privacy Policy

© 2023 Irrawaddy Publishing Group. All Rights Reserved

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

- Business Roundup

Content Search

Un country team in myanmar steps up covid-19 response efforts.

- UNCT Myanmar

Attachments

(Yangon, 19 July 2021) – The UN Country Team in Myanmar is stepping up its response efforts following an alarming spike in the reported number of COVID-19 cases in the country.

Even with very limited testing and people experiencing difficulties in accessing testing, 5497 new cases were reported on July 17 bringing the test positivity rate to 39.12 per cent compared to 22.34 per cent two weeks earlier. In addition, several COVID-19 variants have been detected, including the highly transmissible Delta variant.

Stay-at-home orders in over 70 townships across Myanmar have been imposed, as well as nationwide public holidays declared from 17-25 July in efforts to curb virus spread. Access to hospital beds and oxygen is limited due to insufficient supplies and manpower.

The UN Country Team is working to address the oxygen shortage through the procurement of oxygen concentrators and other necessary equipment through multiple channels.

The immediate scaling up of the provision of critical health services and COVID-19 vaccination efforts, remains an urgent priority.

WHO, UNICEF and partners are redoubling their efforts to accelerate COVID-19 vaccination availability through multiple channels, including through the COVAX facility. Myanmar is expected to receive enough COVID-19 vaccines through the COVAX facility during 2021 to cover 20 per cent of the population which is required to be distributed according to WHO guidelines for prioritizing vaccination. The first batch of these vaccines is expected in the current round of allocations.

Efforts are underway to re-operationalize testing and COVID-19 treatment centres are being established with available resources and capacities.

Currently, COVID-19 testing is occurring in states and regions at the rate of 12,000-15,000 tests per day. With testing at limited levels, however, many cases are expected to be unreported.

The current outbreak of COVID-19 is expected to have devastating consequences for the health of the population and for the economy. A renewed ‘whole of society’ approach is needed now more than ever, allowing all health professionals to work in safety, and both public and private providers enabled to contribute to the response.

Related Content

Myanmar – eu disaster response emergency fund for flood victims (dg echo) (echo daily flash of 28 august 2024), myanmar toolkit: observational gender review - adapted from the rapid gender assessment tool.

Myanmar + 1 more

Siete años después del desplazamiento forzoso en masa de los rohingya de Myanmar, los niños y niñas siguen sufriendo ataques mortales en el estado de Rakhine

Sept ans après le déplacement massif forcé des rohingya du myanmar, les attaques meurtrières visant les enfants se poursuivent dans l’état rakhine.

Pandemics Don’t Really End—They Echo

T he public health emergency related to the COVID-19 pandemic officially ended on May 11, 2023. It was a purely administrative step. Viruses do not answer to government decrees. Reported numbers were declining, but then started coming up again during the summer. By August, hospital admissions climbed to more than 10,000 a week. This was nowhere near the 150,000 weekly admissions recorded at the peak of the pandemic in January 2022.

The new variant is more contagious. It is not yet clear whether it is more lethal. Nor is it clear whether the recent rise is a mere uptick or foreshadows a more serious surge. More than 50,000 COVID-19 deaths have been reported in the U.S. in 2023. Somehow, this has come to be seen as almost normal.

Even while health authorities are keeping their eyes on new “variables of concern,” for much of the public COVID has been cancelled. The news media have largely moved on to other calamities. The pandemic is over. Is it?