- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 22 November 2023

Severe-Enduring Anorexia Nervosa (SE-AN): a case series

- Federica Marcolini 1 ,

- Alessandro Ravaglia 1 ,

- Silvia Tempia Valenta 1 ,

- Giovanna Bosco 2 ,

- Giorgia Marconi 3 ,

- Federica Sanna 1 ,

- Giulia Zilli 1 ,

- Enrico Magrini 1 ,

- Flavia Picone 1 ,

- Diana De Ronchi 1 &

- Anna Rita Atti 1

Journal of Eating Disorders volume 11 , Article number: 208 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2300 Accesses

5 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) poses significant therapeutic challenges, especially in cases meeting the criteria for Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa (SE-AN). This subset of AN is associated with severe medical complications, frequent use of services, and the highest mortality rate among psychiatric disorders.

Case presentation

In the present case series, 14 patients were selected from those currently or previously taken care of at the Eating Disorders Outpatients Unit of the Maggiore Hospital in Bologna between January 2012 and May 2023. This case series focuses on the effects of the disease, the treatment compliance, and the description of those variables that could help understand the great complexity of the disorder.

This case series highlights the relevant issue of resistance to treatment, as well as medical and psychological complications that mark the life course of SE-AN patients. The chronicity of these disorders is determined by the overlapping of the disorder's ego-syntonic nature, the health system's difficulty in recognizing the problem in its early stages, and the presence of occupational and social impairment.

Introduction

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) constitutes a complex eating disorder (ED) characterized by low caloric intake, fear of gaining weight, dysfunctional behavior impeding weight gain, and misperceptions about one’s own body shape and weight [ 1 ]. The intricate nature of AN can lead to severe difficulties in the treatment, and patients may not necessarily benefit from conventional approaches. Most AN patients reach partial or complete remission only after several years from the development of the first symptoms [ 2 ]. Despite substantial intervention efforts, an estimated 20% of AN patients show limited improvements and, over time, become chronic [ 3 , 4 ]. Despite that, there are very few studies on chronic AN, especially in older populations, probably due to the relatively high drop out rate after a few years of treatment [ 5 , 6 ].

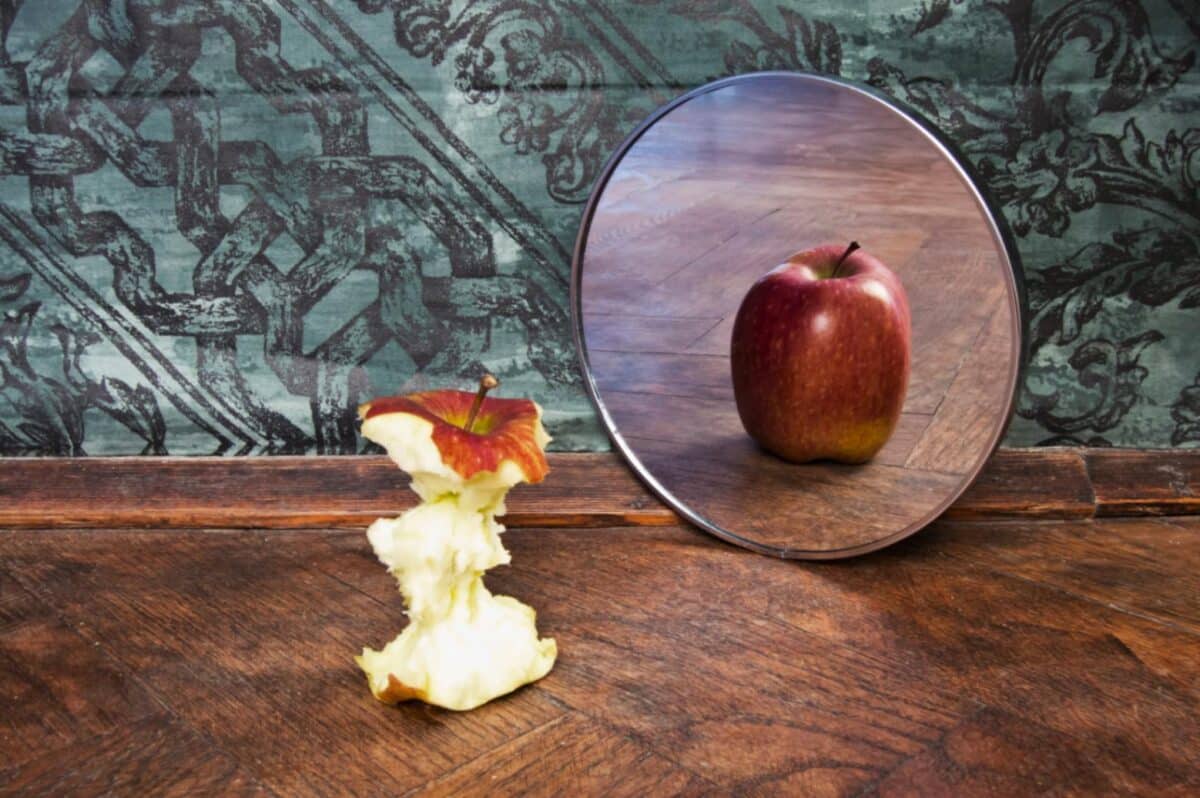

To delineate the domain of chronic AN, the definition of Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa (SE-AN) had been proposed [ 7 ] (Table 1 ), accompanied by suggested maintenance factors [ 8 ]. This definition is useful to describe and analyze the peculiarities of chronic patients, to improve the relatively broad criteria for SE-AN definition and to better understand the clinical development of this ED. The search for a precise terminological framework has shown that the quality of the words used in the definitions, in addition to carrying the risk of stigmatizing patients, can influence the way patients and their families experience ED. Moreover, it can have a significant impact on the perspectives that clinicians have on treatment. For instance, the labels 'chronic' and 'treatment resistant' can both affect clinicians' perspective on a patient's curability or their willingness to engage cooperatively during the treatment. Other terms, such as 'severe and enduring’, 'long-lasting' and similar expressions relating to the severity and duration variation of the disease, may favor a lesser focus on the curability of an individual.

In the present case series, we aim to provide an overview of the possible associations that exist among the multiple variables, causal or consequential, peculiar to SE-AN. The search for common causal factors, although within a small population of patients with SE-AN, may facilitate a better understanding of the disorder and its main determinants in order to intercept cases that are more likely to develop a long history of illness or severe forms that would necessitate intensive treatment. It could also help to improve and personalize the therapeutic approach towards this specific population, considering that even today the available treatments do not always guarantee a positive outcome. In addition, this case series directs its focus on the effects of the disease, treatment compliance, and the description of variables that could contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of the disorder.

Materials and methods

In the present case series, 14 patients were selected from those currently or previously taken care of at the ED Outpatients Unit of the Maggiore Hospital in Bologna between January 2012 and May 2023. To make the sample more homogeneous, we selected only adult patients (age > 18 years, by Italian law) who fully fit the eligibility criteria for SE-AN, as proposed by Hay and Touyz in 2018 [ 7 ].

Information on individual patients was obtained through data collection from several available sources: Electronic Medical Records (EMR), paper records, and other documents available in the psychiatric department.

Demographic characteristics

A total of 14 patients were enrolled, all from Bologna and its province, and all with a history of admission to Public Psychiatric Services (100%). Five patients (35.7%) were still in psychiatric service care, while four patients dropped out of services (28.6%). One patient had died. At the time of data collection, four patients (8.6%) were no longer followed within a psychiatric pathway. A summary of the main clinical and social characteristics of the patients is presented in Tables 2 and 3 .

The patients were all female (100%). The sample had an average age of 42.2 years old (ranging from 24 to 63 years old). Only four out of 14 patients (28.6%) were married and none of them had gone through a divorce. Three patients (21.4%) had at least one child, and only one had more than one. Therefore, the majority of candidates with SE-AN were not married (71.4%) and had no children (78.6%). However, 86% of the patients lived with someone: six lived with their partner/husband, and six with the family of origin.

Almost all of the patients had a job during their lifetime (78.6%), including seven employees (who carried out office work, without any specific responsibility), two hairdressers, one bartender, and one lawyer. Among those who had never worked, two were University students. Therefore, only one out of 14 patients never worked or pursued a college career. Among the 11 individuals who had had a job, however, only three people were known to be employed at the time of the analysis (27.3%). For two people, no data regarding their working life were available on their medical records.

Among the 14 patients, seven (50%) had a cigarette smoking habit, while two (14.2%) had a history of alcohol abuse. Three (21.4%) had a history of self-injury.

Clinical characteristics

The average age of onset of ED symptoms in our sample was 22.7 years (range 11–47), while the average age at which a diagnosis of AN was made in public services (Psychiatry or Dietetics) was 31.5 years (range 16–51). The patients had a mean disease duration of 17 years (range 8–31) combined, in the vast majority of cases (85.7%), with a series of unsuccessful therapeutic attempts. The latency period between the onset of the disease and its recognition by public health services was 8.79 years (range 1–34 years); in nine out of 12 cases (64.3%) the diagnosis was made after at least three years of illness, while in 6 cases (42.9%) after at least seven years.

The most frequent AN subtype in the considered sample was AN-Restrictive (85.7%), while only two patients (14.3%) suffered from the AN-Binge/Purging subtype. The most frequently reported caloric restriction methods were reduced caloric intake and intense physical exercise; this was followed by laxative use, self-induced vomiting, and diuretic use.

The average patient’s Body Mass Index (BMI) reported was 13.43 kg/m 2 (range 7.53–16.94 kg/m 2 ), highlighting the extreme severity of the cases described (according to the DSM-5 [ 1 ], AN patients with BMI < 15 kg/m 2 are classified as showing “extreme severity”). The patient with the lowest BMI included in the case series reached a value of 7.15 kg/m 2 .

Eleven patients (78.6%) had been hospitalized at least once in an internal medicine department because of their ED, due to their severe malnutrition; in addition, among the three patients who had never faced hospitalization, two had previously refused it several times despite the need expressed by their caregivers. In contrast, at least two out of 14 (14.3%) had multiple accesses and one patient was hospitalized at the time of data collection. In parallel, seven of the patients (50%) were admitted at least once to a psychiatric department to manage their disorder. In the examined clinical context, six patients (42.9%) received enteral nutrition through nasogastric tube administration on at least one occasion, while an additional six patients (42.9%) required parenteral nutrition. The purpose of the parenteral nutrition intervention was to augment daily caloric intake and provide supplementary support to oral nutrition exclusively.

Common complications of AN, such as anemia and hypokalemia, and their treatment needs, were also investigated. In 50% of the patients, the occurrence of at least one episode of anemia during the natural history of the disease was reported. Anemia was most commonly macrocytic (57%). Regarding treatment, at least 42.9% of anemia cases were of such severity that they required blood transfusion, 28.6% required only iron and vitamin supplementation. 21.4% had no history of anemia. For the 28.6% no data about the occurrence of anemia as a complication of their disorder was found examining the available clinical records, while several patients refused to take blood tests. At least one episode of hypokalemia was reported in 50% of cases. Of the seven confirmed cases of hypokalemia, 100% required treatment, and at least three were of such severity as to require intravenous infusion therapy.

Other ED complications present within the considered sample, consequences of persistent malnutrition and secondary hormonal disorders typical of AN, included osteoporosis and secondary amenorrhea. In 57.1% of the cases frank osteoporosis was shown and in 28.6% osteopenia was demonstrated. In 93% of patients there was at least one period of secondary amenorrhea during the natural history of the disease (no data regarding one individual); these included two patients taking an Estrogen-Progestin (EP) pill and two who reached menopause before having the diagnosis of AN (one of whom was in early menopause).

The presence of psychiatric comorbidities in the history of these subjects was assessed (Table 4 ), founding that 100% had at least one other psychiatric diagnosis in comorbidity to the ED (not necessarily present to date); three out of 14 patients (21.4%) had only one psychiatric comorbidity, nine (64.3%) had two, and two patients (14.2%) had up to three psychiatric disorders in addition to AN.

It was reported that 50% of patients had a history of familial psychiatric illness, and 14.2% had a parent with severe obesity.

With respect to the therapeutic approaches used for these patients, previous drug therapy attempts employed in ED treatment (in part related to the management of the various psychiatric comorbidities present in the individual cases), and the execution of ED-specific therapeutic pathways (e.g., Dietary care), were evaluated as far as possible.

Nine patients had experienced at least one ED-specific pathway, while five had never been through one; among the latter, four out of five had rejected the proposed ED treatment course, while one was considering the proposal at the time of the data collection. The setting most frequently used by those who had embarked on an ED treatment course was outpatient (100%), followed by semi-residential and residential (44.4%). Among those who started an ED pathway: six completed it, two dropped out, and one moved away.

Regarding the pharmacological therapies taken by patients during their treatment course, the use of three pharmacological classes mainly used in AN treatment (antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines) was analyzed, also considering the possible combined therapeutic indication with respect to the individuals' psychiatric comorbidities.

Nine out of 14 (64.3%) patients used at least one antipsychotic drug, while 28.6% never used antipsychotics; of one out of 14 patients no data were found about antipsychotic administration from the examined clinical documentations. Among users, at least three used more than one antipsychotic in their history, and the most frequently prescribed drug was olanzapine (66.7%), followed by risperidone (22%) and aripiprazole (22%).

11 of 14 patients (78.6%) used at least one antidepressant drug to manage their psychiatric disorders; two patients never used it (n = 14.3%), and one rejected the suggested treatment. Among antidepressant users, 36.4% used more than one. The most commonly prescribed antidepressant was sertraline (77.8%), followed by venlafaxine (44.4%).

Nine out of 14 individuals (64.3%) used at least one benzodiazepine during their course of treatment in psychiatric services. Four patients (28.6%) never used benzodiazepines: three had not been prescribed and one refused to take them. There was one reported case of benzodiazepine abuse, while for one patient no data was found in the available clinical records regarding sedative medications. The most commonly used benzodiazepine appears to be alprazolam (40%).

Lastly, the information obtained showed that all patients (100%) undertook individual psychotherapy during their treatment process, even though duration, frequency, and type of psychotherapeutic courses were not reported in the records.

The present work gives an insight into SE-AN, analyzing clinical features, treatment approaches, and risk factors that might contribute to the persistence of this disorder. Our patients showed a long history of illness, with an average duration of 17 years, punctuated by therapeutic failures. The majority of patients were diagnosed with the restrictive subtype of AN, characterized by caloric restriction methods, including reduced intake and intense physical exercise. The BMI average was 13.43 kg/m 2 , data highlighting the extreme severity of this clinical sample, aligning with the DSM-5 classification of extreme severity for AN patients with BMI < 15 kg/m 2 [ 1 ]. We identified a high prevalence of hospitalizations due to severe malnutrition or the occurrence of medical complications (i.e., anemia, hypokalemia, osteoporosis, amenorrhea). Moreover, the majority of the sample also suffered from psychiatric comorbidities. The presence and severity of these aspects confirms the condition of intense medical and psychological burden faced by these patients [ 9 , 10 ].

The treatment history of these individuals has often proven to be complex and ineffective, despite the multitude of approaches used, including outpatient, semi-residential, or residential treatment. In addition, this work has highlighted a difficulty on the part of the health care system in identifying the disease at the time of its presentation, leading to diagnostic delays and higher therapeutic resistance. In fact, consolidation of the symptoms and psychopathological mechanisms over time in AN patients reduces the likelihood of positive outcomes following treatments, consequently limiting the chances of recovery for these individuals [ 11 ]. There is growing bio‐behavioral evidence in EDs that the disease changes over time, with maladaptive eating and weight control behaviors becoming more automatic and entrenched [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Consistent with these results, many clinical studies suggest that response to treatment is more positive in the early stages of the disease (i.e., within the first three years of ED onset), and decreases the longer the condition persists [ 18 , 19 ] .

Likewise, it has been reported that, during early-stage ED, longer disease duration is associated with higher psychological distress and occupational and social impairment [ 9 , 20 ] . Therefore, the lack of—or delay in access to—treatment during the early-stage ED may facilitate chronicity, negatively impact the chances of recovery, impair social and occupational accomplishment [ 21 ]. In fact, from an environmental point of view, our sample showed relatively poor social and occupational adjustment, most of the patients not being married (71.4%), without children (78.6%), and unemployed (72.7%) at the time of data collection. These findings are in line with recent studies in the field, which characterizes individuals with SE-AN as impoverished in terms of intimacy and relationships [ 3 , 22 ], and exhibiting a propensity for economic frugality, some living below the poverty line, without well-remunerated employment behind them [ 22 , 23 ].

The duration of untreated ED (DUED) is the period of time between disease onset and the start of evidence‐based treatment. In the existing literature, the average DUED is reported to be between two and three years for anorexia nervosa (AN) [ 24 ] . However, it is noteworthy that our study yielded different findings, as we observed an average DUED of 8.79 years in our sample, with a wide-ranging variation from as short as 1 year to as long as 39 years. This significant deviation from the established averages underscores the heterogeneity and complexity of DUED across different populations, warranting further exploration to elucidate the contributing factors.

DUED can be divided into two distinct stages [ 25 ] . The initial stage is characterized by delays mostly driven by patient‐related factors, wherein individuals may experience symptoms but fail to recognize the presence of a problem or may not be prepared to seek help. In the second stage, individuals seek treatment, but they encounter service‐level delays, further prolonging the untreated illness period.

Flynn et al. [ 21 ] evaluated the role of First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for ED (FREED), finding that FREED, significantly reducing the DUED, is associated with significantly shorter wait times for both assessment and treatment, higher patients compliance to treatment, and possible distress reduction and deterioration prevention. The same results are suggested by Andrés-Pepiñá et al. [ 26 ], reporting that a substantial percentage of patients with adolescence-onset AN achieve complete remission of the disorder when they undergo specialist treatment, and an early intervention in AN may help to improve the disorder course. Also, Austin et al. [ 24 ] suggested that DUED may be a modifiable factor influencing EDs outcomes and that a shorter DUED may be related to a higher probability of remission.

Diagnostic and treatment delays appear to be partly attributable to gaps in the health system and scarce economic resources, and partly attributable to the ego-syntonic nature of the disorder itself. The treatment refractoriness, pushing the patient away from the therapeutic paths taken, if not rejected out of hand, is usually a result of an incomplete understanding of their disease state [ 25 , 27 ]. People with AN tend to hide their state of emaciation, avoiding an established relationship with primary care and resorting to emergency departments only when medical problems arise [ 28 ], leading in some cases to hospitalization. The prevalence of untreated individuals with EDs is estimated to be as high as 75% [ 29 ]. This considerable percentage may be attributed, in part, to comorbid conditions that influence motivation, scheduling constraints, or the need for clinical prioritization within general mental health services. These factors can result in delayed or hindered access to specialized ED services, particularly in cases where individuals with EDs also present with concurrent issues such as self-harm or suicidal behaviors [ 30 ].

Diagnostic-therapeutic delays thus lead to high rate of medical comorbidities due to malnutrition, the need for internal medicine/psychiatric hospitalization, as well as the substantial burden of psychiatric comorbidities [ 9 , 10 , 20 , 31 ]. Medical comorbidities and complications associated with EDs can range from mild to severe and life-threatening, potentially involving all body systems and placing people at increased risk of medical instability and death [ 32 ]. Therefore, understanding how comorbidities and co-occurring medical complications impact EDs is fundamental to treatment and recovery. In addition to the ED-associated medical comorbidities, EDs often occur together with other psychiatric conditions. Psychiatric comorbidities in people with EDs are associated with higher emergency department presentations and hospitalizations and health system costs [ 33 ]. Comorbidities may result from symptoms and behaviors associated with the ED, be co-occurring, or precede the ED onset [ 34 , 35 ]. People with an ED, their caregivers and care providers often face a complex dilemma: the individual with ED needs treatment for not only for their ED but also for their psychiatric comorbidities, and it can be hard to determine which is the clinical priority. This is further complicated because EDs and comorbidities may have a reciprocal relationship of mutual worsening, exacerbating each other's symptoms and negatively impacting treatments and outcomes.

The case series also confirms what literature shows about how the severity of SE-AN cannot be defined solely by BMI value and resistance to treatment [ 36 , 37 , 38 ], but also by the multiplicity of possible negative consequences that mark the life course of these patients, and the increasing consolidation of ED related psychopathology [ 39 ]. Repeated hospitalizations, severe complications, frequent comorbidities, a variety of unproven drug treatments are all equally present variables that indelibly mark the very long history of the disease.

This case series presented 14 cases of adult patients affected by SE-AN. It highlighted the relevant issue of resistance to treatment that marks the life course of these subjects, as well as the prospect of a variety of complications, both medical, psychological as well as social. The chronicity of this disorder is determined by the overlapping of numerous elements. First of all, the very nature of the disorder, which often makes the patient less likely to seek treatment, the difficulty of the health system in recognizing the problem in its early stages, but also the presence of an occupational and social impairment. Further studies on the topic are needed to broaden the knowledge of this disorder and its pathogenesis. This will enable us to develop more precise and effective interventions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author following a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Anorexia Nervosa

Body Mass Index

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition

duration of untreated eating disorder

Eating Disorder

Estrogen-progestin

First episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders

Obsessive compulsive disorder

Personality disorder

Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa

DSM Library [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Dobrescu SR, Dinkler L, Gillberg C, Råstam M, Gillberg C, Wentz E. Anorexia nervosa: 30-year outcome. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2020;216(2):97–104.

Article Google Scholar

Kiely L, Conti J, Hay P. Conceptualisation of severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):606.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, Murray HB, Keshaviah A, Hastings E, et al. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(2):184–9.

Steinhausen HC. Outcome of eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(1):225–42.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Crosby RD, Koch S. Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa: results from a large clinical longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1018–30.

Hay P, Touyz S. Classification challenges in the field of eating disorders: can severe and enduring anorexia nervosa be better defined? J Eat Disord. 2018;6:41.

Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Serious and enduring anorexia nervosa from a developmental point of view: how to detect potential risks at an early stage and prevent chronic illness? Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1313–4.

Davidsen AH, Hoyt WT, Poulsen S, Waaddegaard M, Lau M. Eating disorder severity and functional impairment: moderating effects of illness duration in a clinical sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(3):499–507.

van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):521–7.

Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1284–93.

Berner LA, Marsh R. Frontostriatal circuits and the development of bulimia nervosa. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:395.

Dalton B, Foerde K, Bartholdy S, McClelland J, Kekic M, Grycuk L, et al. The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on food choice-related self-control in patients with severe, enduring anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1326–36.

Fladung AK, Schulze UME, Schöll F, Bauer K, Grön G. Role of the ventral striatum in developing anorexia nervosa. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3(10):e315.

O’Hara CB, Campbell IC, Schmidt U. A reward-centred model of anorexia nervosa: a focussed narrative review of the neurological and psychophysiological literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;52:131–52.

Werthmann J, Simic M, Konstantellou A, Mansfield P, Mercado D, van Ens W, et al. Same, same but different: attention bias for food cues in adults and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(6):681–90.

Steinglass JE, Walsh BT. Neurobiological model of the persistence of anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord. 2016;4:19.

Ambwani S, Cardi V, Albano G, Cao L, Crosby RD, Macdonald P, et al. A multicenter audit of outpatient care for adult anorexia nervosa: symptom trajectory, service use, and evidence in support of “early stage” versus “severe and enduring” classification. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1337–48.

Treasure J, Stein D, Maguire S. Has the time come for a staging model to map the course of eating disorders from high risk to severe enduring illness? An examination of the evidence. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9(3):173–84.

de Vos JA, Radstaak M, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Having an eating disorder and still being able to flourish? Examination of pathological symptoms and well-being as two continua of mental health in a clinical sample. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2145.

Flynn M, Austin A, Lang K, Allen K, Bassi R, Brady G, et al. Assessing the impact of first episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders on duration of untreated eating disorder: a multi-centre quasi-experimental study. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2021;29(3):458–71.

Robinson PH, Kukucska R, Guidetti G, Leavey G. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SEED-AN): a qualitative study of patients with 20+ years of anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2015;23(4):318–26.

Robinson P. Severe and enduring eating disorders: concepts and management. In: Anorexia and bulimia nervosa [Internet]. IntechOpen; 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 23]. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/68319 .

Austin A, Flynn M, Richards K, Hodsoll J, Duarte TA, Robinson P, et al. Duration of untreated eating disorder and relationship to outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2021;29(3):329–45.

Birchwood M, Connor C, Lester H, Patterson P, Freemantle N, Marshall M, et al. Reducing duration of untreated psychosis: care pathways to early intervention in psychosis services. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2013;203(1):58–64.

Andrés-Pepiñá S, Plana MT, Flamarique I, Romero S, Borràs R, Julià L, et al. Long-term outcome and psychiatric comorbidity of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;25(1):33–44.

Starzomska M, Rosińska P, Bielecki J. Chronic anorexia nervosa: patient characteristics and treatment approaches. Psychiatr Pol. 2020;54(4):821–33.

Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm FA, Kraemer HC, Schreiber GB, Crawford PB, Daniels SR. Health services use in women with a history of bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(1):11–8.

Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Myers TC, Kadlec K, Lahaise K, et al. Minimizing and treating chronicity in the eating disorders: a clinical overview. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(4):467–75.

Hay P, Touyz S. Treatment of patients with severe and enduring eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(6):473–7.

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–58.

Mehler PS, Birmingham C, Crow S, Jahraus J. Medical complications of eating disorders. Treat Eat Disord. 2010;1(48):66–80.

Google Scholar

John A, Marchant A, Demmler J, Tan J, DelPozo-Banos M. Clinical management and mortality risk in those with eating disorders and self-harm: e-cohort study using the SAIL databank. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(2):e67.

Monteleone AM, Pellegrino F, Croatto G, Carfagno M, Hilbert A, Treasure J, et al. Treatment of eating disorders: a systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;142:104857.

Van Alsten SC, Duncan AE. Lifetime patterns of comorbidity in eating disorders: an approach using sequence analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28(6):709–23.

Smith KE, Ellison JM, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, et al. The validity of DSM-5 severity specifiers for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1109–13.

Gianini L, Roberto CA, Attia E, Walsh BT, Thomas JJ, Eddy KT, et al. Mild, moderate, meaningful? Examining the psychological and functioning correlates of DSM-5 eating disorder severity specifiers. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(8):906–16.

Engelhardt C, Föcker M, Bühren K, Dahmen B, Becker K, Weber L, et al. Age dependency of body mass index distribution in childhood and adolescent inpatients with anorexia nervosa with a focus on DSM-5 and ICD-11 weight criteria and severity specifiers. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30(7):1081–94.

Krug I, Binh Dang A, Granero R, Agüera Z, Sánchez I, Riesco N, et al. Drive for thinness provides an alternative, more meaningful, severity indicator than the DSM-5 severity indices for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2021;29(3):482–98.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences, University of Bologna, Viale Pepoli 5, 40123, Bologna, Italy

Federica Marcolini, Alessandro Ravaglia, Silvia Tempia Valenta, Federica Sanna, Giulia Zilli, Enrico Magrini, Flavia Picone, Diana De Ronchi & Anna Rita Atti

Department of Clinical Nutrition, AUSL Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Giovanna Bosco

U.O. Cure Primarie, AUSL Area Vasta Romagna, ambito di Rimini, Rimini, Italy

Giorgia Marconi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception of the work: MF, ARA; design of the work: MF, RA; Acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data: BG, MG, SF, ZG, ME, PF; Drafted the work: MF, TVS; Revision of the work: ARA, DRD.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Federica Marcolini .

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement and consent for publication.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Marcolini, F., Ravaglia, A., Tempia Valenta, S. et al. Severe-Enduring Anorexia Nervosa (SE-AN): a case series. J Eat Disord 11 , 208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00925-6

Download citation

Received : 04 July 2023

Accepted : 03 November 2023

Published : 22 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00925-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Eating disorders

- Severe-enduring

- Case series

Journal of Eating Disorders

ISSN: 2050-2974

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2020

Case report: cognitive performance in an extreme case of anorexia nervosa with a body mass index of 7.7

- Simone Daugaard Hemmingsen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6789-7105 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Mia Beck Lichtenstein ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7885-9187 6 , 7 ,

- Alia Arif Hussain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1011-5165 8 , 9 ,

- Jan Magnus Sjögren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2060-1914 8 , 9 &

- René Klinkby Støving ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4255-5544 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

BMC Psychiatry volume 20 , Article number: 284 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

4253 Accesses

7 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Studies show that adult patients with anorexia nervosa display cognitive impairments. These impairments may be caused by illness-related circumstances such as low weight. However, the question is whether there is a cognitive adaptation to enduring undernutrition in anorexia nervosa. To our knowledge, cognitive performance has not been assessed previously in a patient with anorexia nervosa with a body mass index as low as 7.7 kg/m2.

Case presentation

We present the cognitive profile of a 35-year-old woman with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa who was diagnosed at the age of 10 years. She was assessed with a broad neuropsychological test battery three times during a year. Her body mass index was 8.4, 9.3, and 7.7 kg/m 2 , respectively. Her general memory performance was above the normal range and she performed well on verbal and design fluency tasks. Her working memory and processing speed were within the normal range. However, her results on cognitive flexibility tasks (set-shifting) were below the normal range.

Conclusions

The case study suggests that it is possible to perform normally cognitively despite extreme and chronic malnutrition though set-shifting ability may be affected. This opens for discussion whether patients with anorexia nervosa can maintain neuropsychological performance in spite of extreme underweight and starvation.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02502617 . Registered 20 July 2015.

Peer Review reports

A growing amount of evidence indicate that anorexia nervosa (AN) is associated with impaired or inefficient neuropsychological performance in relation to healthy control subjects, regarding attention [ 1 , 2 ], memory [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ], processing speed [ 4 ], and especially the executive functions [ 5 ] central coherence [ 6 ], decision-making [ 6 , 7 ], and cognitive flexibility [ 8 , 9 ]. It has been debated whether this is related to state (due to factors such as malnutrition) or trait (a premorbid trait or endophenotype of the disorder [ 10 ]). Some studies have found that patients who recovered from AN have impaired cognitive performance compared to healthy control subjects [ 11 , 12 ], supporting the trait theory of the disorder. However, longitudinal studies have found that executive functions can be normalized following weight stabilization in patients with AN [ 13 , 14 ], supporting the state theory.

Research on cognitive performance before and after re-nutrition in adult patients with extreme and chronic AN is sparse. Some studies have examined cognitive performance in patients with AN with a mean body mass index (BMI) below 15 kg/m2 (e.g. [ 10 ]), corresponding to extreme AN severity according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5) [ 15 ]. However, it is unclear if patients with AN with BMI below 10 kg/m2 will display the same cognitive profile.

It has been suggested that malnutrition might affect cognitive performance since the classic Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment [ 16 ], where cognitive functions were studied in 36 healthy military objectors with normal weight before and after semistarvation with 25% weight-loss over a 24-week period. The men reported decline in concentration. However, the standardized tests that were administered did not confirm measurable alterations. Newer research on healthy subjects, although somewhat inconclusive, indicates affected psychomotor speed and executive functions following short-term semi-starvation [ 17 ].

However, other factors than malnutrition or weight-loss have been suggested to affect cognitive performance in patients with AN, such as long illness duration [ 18 ] and age [ 18 ]. This could explain a difference in results for children/adolescents and adults with AN mentioned in the literature [ 19 , 20 ], which cannot be explained by the trait theory.

The current case report was part of an ongoing longitudinal research project investigating the effect of re-nutrition on cognitive performance in patients with severe AN. The aim of the case study was to present the neuropsychological performance of a patient with chronic AN and extremely low BMI in order to discuss whether extremely low weight and long duration of illness are associated with cognitive impairment and if cognitive adaptation takes place. No study to our knowledge has previously reported on the cognitive profile of a patient with AN with a BMI as low as 7.7 kg/m2.

We want to introduce the idea of cognitive adaptation to severe malnutrition as a supplement to the discussion on cognitive impairment in AN. However, this idea should not be confused with Taylor’s Theory of Cognitive Adaptation [ 21 ]. The presented idea of cognitive adaptation is the idea that cognitive functions can adapt to persisting low weight in AN, i.e. cognitive performance can remain normal or regain normality in severe and enduring AN. The adaptation does not exclude specific cognitive impairment.

The current case report investigates the cognitive profile of a 35-year-old Caucasian woman with extremely severe and enduring AN who was diagnosed at the age of 10 years. The patient’s weight loss is accomplished through fasting. According to the DSM-5 [ 15 ], the patient’s symptoms are in accordance with the restricting type and the severity of AN for the patient is categorized as extreme. The patient has had low body weight since the onset of the disease 25 years ago. Consequently, she is still prepubescent.

The patient’s extreme malnutrition, the medical complications, and the refeeding treatment has previously been described in a case report [ 22 ]. Since the previous report [ 22 ], she has survived another 5 years, living in her own residence with several stabilizing hospitalizations. Her nadir BMI, defined as the lowest registered BMI, has decreased further to 7.2 kg/m2. To our knowledge, this is the lowest BMI reported in AN in the literature. During her long and severe illness course, she has participated in psychotherapy for years. However, during the past few years, she has refused to participate in psychotherapy, while she has continued the harm-reducing treatment in the nutrition department. No cognitive profile has been assessed before the current report.

She has continuously been provided supplementation with vitamins and minerals. At the present admission, she weighed 20.2 kg, including edema corresponding to at least 2 kg, and her height was 1.55 m, corresponding to a BMI of 8.41 kg/m 2 . After life-saving and stabilizing fluid and electrolyte correction, and refeeding according to guidelines [ 23 ] during 2 weeks of hospitalization, we tested her with a neuropsychological test battery (2 weeks after admission: T 0 ). After an additional 2 months of hospitalization, she could not be motivated to continue the treatment any longer. Due to years of history with rapid relapse after prolonged forced treatment, she was allowed to be discharged to outpatient follow-up. She was re-tested in the outpatient clinic 6 days following dropout from inpatient treatment and approximately 3 months after admission, (re-test: T 1 ) with a weight of 22.4 kg (BMI: 9.3 kg/m 2 ), and again at 12 months from T 0 , during a re-hospitalization, 7 days after admission (follow-up: T 2 ), with BMI 7.7 kg/m 2 . Thus, T 0 and T 2 were done at the hospital after initial stabilizing glycemic, fluid- and electrolyte correction, whereas T 1 was done in an outpatient setting, where she was in a clinically stable condition, but without the initial stabilizing treatment.

The psychopathological profile of the patient

The patient scored 21 on the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II [ 24 ];) indicating moderate depression at 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ). Her scores on the Eating Disorder Inventory 3 (EDI-3 [ 25 ];) at T 0 are presented in Table 1 below. Compared to the Danish validation of EDI-3 for patients with AN ( [ 26 ]; Table 1 ), her low scores on the Drive for Thinness, the Interoceptive Deficits, the Perfectionism, and the Asceticism subscales are of interest.

Qualitative observations

During the first 2 weeks after admission, the patient was unable to participate in the neuropsychological assessment due to fatigue. Two weeks after admission, when the baseline assessment took place (T 0 ), the patient was lying down during the assessment and was noticeably tired. This was neither the case at retest (T 1 ) nor at follow-up (T 2 ) where the patient was sitting at a table. Her alertness and energy level at follow-up (T 2 ) were notable in light of her low BMI. The patient was calm during all three assessments (divided into six sessions) and expressed that the tests were fun. The aim of the study was explained to the patient before the first administration. However, only information written in the test manuals was given during each assessment.

The following validated neuropsychological tests were selected in cooperation with an experienced neuropsychologist to examine a wide range of cognitive functions: the Wechsler Memory Scale III (WMS-III) [ 27 ]; the d2-R Test of Attention – Revised [ 28 , 29 ]; the Processing Speed Index (PSI) of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV (WAIS-IV) [ 30 ]; the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) [ 31 ], Verbal Fluency Test, Design Fluency Test and Trail Making Test; and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Revised and Expanded (WCST) [ 32 ] (only administered at T 0 ). Information on each test variable, including internal consistency and test-retest reliability, are presented in Table 2 . The test battery can be administered in approximately 2 h. For all three administrations, the test battery was divided into two sessions (1 h per session) 1 day apart.

Neuropsychological findings

Table 3 gives an overview of the timeline of the patient’s raw scores and scaled scores on the test battery. Table 4 presents the patient’s norm scores and percentiles on the WMS-III, the WAIS-IV PSI, and the d2-R. Table 5 presents the patient’s WCST scores at 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ). Information on scoring are presented below each of the tables.

Memory performance on WMS-III

The patient’s scores on WMS-III indicate average to very superior auditory, visual, immediate and general memory performance (108 to 142; Mean: 100), and low average to average working memory (Table 4 ). The technical manual for WMS-III reports adequate test – retest reliability for all indexes in the age group 16–54 years, except for the Auditory Recognition Delayed Index ( [ 33 ]; Table 2 ). Estimated standard error of difference (S Diff ) scores were calculated based on Iverson and Grant ( [ 34 ]; Table 2 ). Differences between the three assessments are outlined here. Her scores on the Auditory Delayed Index decreased more than S diff : 6.70 from 132 (very superior) at 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ) to 108 (average) at re-test (T 1 ) and increased again to 132 (very superior) at follow-up (T 2 ). Her scores on the Visual Immediate Index increased slightly more than S diff : 6.70 from 118 (high average) at re-test (T 1 ) to 127 (superior) at follow-up (T 2 ). Her scores on the Visual Delayed Index decreased more than S diff : 7.65 from 125 (superior) at re-test (T 1 ) to 109 (average) at follow-up (T 2 ). Her scores on the Immediate Memory Index increased more than S diff : 3.17 from 134 (very superior) at re-test (T 1 ) to 142 (very superior) at follow-up (T 2 ). Her scores on the Working Memory Index decreased more than S diff : 8.22 from 102 (average) at 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ) to 88 (low average) at re-test (T 1 ). The scores on the rest of the indexes did not change more than the estimated S diff scores between time points.

Cognitive flexibility on D-KEFS and WCST

Overall, she performed above average on the Verbal Fluency Test (Table 3 ) at all three test times compared to the normative population for age, except for her performance at re-test (T 1 ) on the switching condition, which was decreased more than S diff : 2.42 to average, and the high number of repetition errors (7; below average) at re-test (T 1 ) and (3; average) at follow-up (T 2 ).

She performed average to above average on the Design Fluency Test at all three test sessions (Table 3 ). However, the switching condition score was lower [ 6 ] at follow-up (T 2 ) compared to 8 at 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ) and re-test (T 1 ), though still average.

During follow-up (T 2 ) on the Trail Making Test (Table 3 ), her performance on the Number-Letter Sequencing test, measuring cognitive flexibility, was below average (111 s), in spite of being average at 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ; 90 s) and re-test (T 1 ; 79 s). The numbers condition was very low at T 0 (55 s; below average), improving somewhat at re-test (T 1 ; 46 s; below average) and follow-up (T 3 ; 41 s; below average). We have no explanation for this result. On the other conditions, her performance was average at all three test times on the Trail Making Test.

Her scores on the WCST (Table 5 ) 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ) place her in the mild to moderately-to-severely range of impairment on cognitive flexibility according to this task. She completed one out of six categories (< 1st percentile). She made 52 perseverative responses (< 1st percentile; standard score 55; moderately-to-severely impaired range). She committed 50 errors (8th percentile; standard score 79: mildly impaired range), of which 36 were perseverative errors (1st percentile; standard score 55: moderately impaired range).

WAIS-IV processing speed

The scores on the Processing Speed Index (Table 4 ) were average compared to the normative population for age at all three test times. There were no relevant differences between time points. She scored 93 at admission (T 0 ) and re-test (T 1 ) and 98 at follow-up (T 2 ).

d2-R test of attention

At 2 weeks after admission (T 0 ) and re-test (T 1 ), she had a small number of processed targets (426 and 420), 18th to 21st percentile (Tables 3 and 4 ), her concentration performance was 175 and 176 corresponding to the 42nd percentile and she committed three and no errors respectively (> 90th percentile). At follow-up (T 2 ), her concentration performance was above the mean (185; 54th percentile) but not increased more than S diff : 24.89. The total processed targets score was still low (451; 34th percentile), and she committed few errors (four; 90th percentile).

Discussion and conclusions

The patient exhibited average to very superior performance on verbal fluency, design fluency, processing speed, and memory. However, her working memory performance was low average. Her attention and concentration performance were below average to average, and her performance on cognitive flexibility tasks were average to moderately-to-severely impaired.

The present case report demonstrates surprisingly good cognitive performance in a patient with severe and enduring AN with extremely low BMI varying between 7.7 and 9.3 during the study period of 1 year. However, some of her executive functions seem to be impaired. This is in line with previous research on patients with AN [ 5 , 8 ]. The present results suggest that her working memory was normal (low average) in line with previous studies [ 35 , 36 ]. However, her working memory performance was lower compared to the rest of her memory performance, which was average to very superior. The results from the D-KEFS indicate average to above-average performance with perhaps somewhat weaker cognitive flexibility (below average to average). On the other hand, the results from the WCST indicate impairment in cognitive flexibility. The overall differences in performance between the three assessments were minimal. This indicates that the minor differences in BMI between the test assessments did not significantly affect her cognitive performance, as expected.

Impaired cognitive flexibility

It could be that impaired cognitive flexibility existed prior to the illness as a premorbid trait as suggested previously [ 10 ], or that the malnutrition has affected the patient’s cognitive flexibility. Since we are missing data on her premorbid level, we cannot draw any firm conclusions.

Impaired cognitive flexibility has previously been reported in patients with AN with higher BMI [ 37 ], indicating that impairments in cognitive flexibility do not necessarily relate to undernutrition. In patients with AN who had recovered from the illness, cognitive flexibility was in the normal range in this study. However, other studies found that individuals who recovered from AN exhibited more or less impaired executive functioning [ 10 ]. Longitudinal research on the relationship between different BMI states and cognitive performance is highly needed.

Impaired cognitive flexibility may also play a role in the perpetuation of AN. Impaired cognitive flexibility has been suggested as a maintenance factor [ 38 ] and a factor related to lack of illness insight characteristic of patients with restrictive AN [ 39 ]. Lack of illness insight could be related to treatment resistance [ 40 ]. The patient’s low scores on EDI-3 subscales also reflect a discrepancy between illness severity and self-reported symptoms. This discrepancy or ambivalence is part of the nature of the disorder reflected in the low motivation for recovery and high number of dropouts from treatment alongside an expressed desire to change [ 41 ].

Cognitive adaptation in anorexia nervosa

Survival of long-term starvation is only possible due to extensive adaptive endocrine and metabolic alterations [ 42 ]. How these alterations affect cognitive functions still remains to be clarified. Well-designed longitudinal studies on severely underweight patients with a long illness duration are lacking. However, the present case report suggests that essential preservation of some cognitive functions occurs even in extreme chronic semi-starvation.

The mechanisms allowing for such preservation remains a subject of speculation. Links can be made to research on neuroplasticity and functional reorganization of cognitive functions after brain injury since patients with AN have white matter alterations [ 43 ]. Research shows that brain maturation processes of especially the prefrontal cortex continue until people are approximately 25 years old [ 44 ]. Nutritional status seems to impact this brain maturation [ 44 ]. Executive functions associated with the prefrontal cortex could therefore be affected by undernutrition during development of prefrontal connections in the brain in adolescence and young adulthood. Thus, impairment on executive functions may not arise until adulthood in patients with AN. This is in line with research that found no cognitive flexibility impairment in children and adolescents with AN but impairments in adults with AN [ 19 , 20 ]. The literature indicates that other cognitive functions associated with the prefrontal cortex, such as memory, are also impaired in adults with AN [ 3 ]. However, overall, this literature is not as explicit as the literature showing cognitive flexibility impairment in adults with AN. The ambiguity in the literature indicates differences between cognitive functions related to the prefrontal cortex in patients with AN. It might be that some prefrontal connections potentially being affected during low weight in adolescence could be reorganized or “compensated for” with time as is possible with reorganization or apparent functional recovery after brain injury [ 45 ]. In that case, cognitive performance could be regained after impairment has occurred. Some dimensions of cognitive flexibility might, however, be more difficult to compensate for. This could explain specific cognitive flexibility impairment in patients recovered from AN [ 10 ] and explain that the patient in the present case report performed normal and superior on some functions associated with prefrontal connections (memory and verbal fluency) but poorer on cognitive flexibility. We therefore suggest that reorganization of some cognitive functions can occur in spite of persisting low weight in patients with AN. In line with the possibility of cognitive reorganization in AN, Cognitive Remediation Therapy seems to improve executive functioning in patients with AN [ 46 ]. The suggested theory of cognitive adaptation may therefore not be specific to persisting low weight in AN. However, fast, substantial weight-loss could affect cognitive performance differently than persisting low weight. Therefore, studies on starving healthy subjects, including the Minnesota Semi-Starvation Experiment [ 16 ], could show different results than studies on patients with severe and enduring AN. Likewise, studies on patients with short illness duration might find different results than studies of patients with enduring AN. It is also unclear if patients developing AN in adulthood will display the same cognitive impairments. In line with these reflections, a case report of a 27-year-old Japanese woman in a coma, with BMI of 8.5 kg/m 2 at admission, describes a patient with AN where the outcome of severe malnutrition was persistent neurologic sequelae [ 47 ]. The woman developed AN at the age of 21 years where the patient in the present case report was diagnosed at the age of 10 years. The difference in age of onset, duration of illness, and/or manner of weight-loss (fast, substantial weight-loss compared to persisting low weight) may have resulted in different outcomes for the women. It is, however, also a possibility that the patient in the present case report might have an extreme phenotype which enables her to perform well in spite of her being extremely underweight.

We cannot say how high the patient’s scores on the neuropsychological test battery might be if she had not been as malnourished. We assume the patient would perform better on cognitive flexibility tasks, that her processing speed and working memory would be higher, and that she would be able to concentrate better had she not been malnourished. This is somewhat supported by previous research. Although the literature suggests impaired cognitive performance in patients with AN, the reported impairments were limited compared to healthy subjects [ 8 , 48 ]. Furthermore, it may be that severely underweight patients with AN have a higher verbal IQ [ 49 ], which does not, however, exclude the possibility of specific cognitive impairments [ 50 ]. This could explain the patient’s high memory performance (and probably global IQ) alongside specific impairment in cognitive flexibility on the WCST. This case may therefore not differ from other patients with severe AN regarding cognitive performance. It may be that the superior performance related to some cognitive functions is a trait of severely underweight patients with AN and/or that a cognitive adaptation to enduring AN increases performance to the premorbid level. In this case, (regained) superior performance of some cognitive functions (i.e. memory and verbal IQ) can exist alongside cognitive impairment in others (i.e. cognitive flexibility). This may change our view of the cognitive profile and its development in patients with severe and enduring AN.

Regardless, the fact that we were able to test the patient in the present case, raises a discussion as to whether she and others with extremely low weight may be responsive to psychotherapy as well. In the present case, the patient underwent psychotherapy for several years albeit without any impact on her weight. More research focusing on the validation of neuropsychological tests including investigation of the practice effect in this patient population is needed.

The individual scores on neuropsychological tests should always be interpreted with care. Factors other than persisting low weight may affect neuropsychological performance (e.g. dehydration, stress, depression, and anxiety). In the present case, the patient did express depressive symptoms corresponding to moderate depression, which might have influenced results on impairment in cognitive flexibility. Furthermore, the patient might experience other issues related to cognitive performance in daily life, which cannot be discovered in a neuropsychological assessment context.

Obviously, conclusions can never be drawn from one case. However, since the neuropsychological testing included a broad range of tests and was repeated three times during a year, the present case report is valid as a basis for reflecting on the affected individual’s cognitive performance at this stage. The present case report demonstrates that cognitive functions may be largely preserved under extreme chronic malnutrition or that cognitive functioning may be regained (reorganized) in spite of extreme chronic malnutrition. More research on patients with AN with extremely low BMI (< 10) is needed to determine whether cognitive performance is affected by starvation and malnutrition.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article in tables or text. Raw data in a fully anonymized version is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Anorexia nervosa

Intelligence quotient

Body mass index

The Beck Depression Inventory II

The Eating Disorder Inventory 3

The Wechsler Memory Scale III

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV

The Processing Speed Index

The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Revised and Expanded

Seed JA, Dixon RA, McCluskey SE, Young AH. Basal activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and cognitive function in anorexia nervosa. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;250(1):11–5.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Seed JA, McCue PM, Wesnes KA, Dahabra S, Young AH. Basal activity of the HPA axis and cognitive function in anorexia nervosa. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(1):17–25.

Biezonski D, Cha J, Steinglass J, Posner J. Evidence for Thalamocortical circuit abnormalities and associated cognitive dysfunctions in underweight individuals with anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(6):1560–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kjaersdam Telleus G, Jepsen JR, Bentz M, Christiansen E, Jensen SO, Fagerlund B, et al. Cognitive profile of children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(1):34–42.

Roberts ME, Tchanturia K, Stahl D, Southgate L, Treasure J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of set-shifting ability in eating disorders. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1075–84.

Abbate-Daga G, Buzzichelli S, Marzola E, Aloi M, Amianto F, Fassino S. Does depression matter in neuropsychological performances in anorexia nervosa? A descriptive review. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(6):736–45.

Bodell LP, Keel PK, Brumm MC, Akubuiro A, Caballero J, Tranel D, et al. Longitudinal examination of decision-making performance in anorexia nervosa: before and after weight restoration. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;56:150–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hirst RB, Beard CL, Colby KA, Quittner Z, Mills BM, Lavender JM. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis of executive functioning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:678–90.

Tchanturia K, Davies H, Roberts M, Harrison A, Nakazato M, Schmidt U, et al. Poor cognitive flexibility in eating disorders: examining the evidence using the Wisconsin card sorting task. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28331.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tchanturia K, Morris RG, Anderluh MB, Collier DA, Nikolaou V, Treasure J. Set shifting in anorexia nervosa: an examination before and after weight gain, in full recovery and relationship to childhood and adult OCPD traits. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38(5):545–52.

Danner UN, Sanders N, Smeets PA, van Meer F, Adan RA, Hoek HW, et al. Neuropsychological weaknesses in anorexia nervosa: set-shifting, central coherence, and decision making in currently ill and recovered women. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(5):685–94.

Wu M, Brockmeyer T, Hartmann M, Skunde M, Herzog W, Friederich H-C. Reward-related decision making in eating and weight disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence from neuropsychological studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;61:177–96.

Lozano-Serra E, Andres-Perpina S, Lazaro-Garcia L, Castro-Fornieles J. Adolescent anorexia nervosa: cognitive performance after weight recovery. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(1):6–11.

Firk C, Mainz V, Schulte-Ruether M, Fink G, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K. Implicit sequence learning in juvenile anorexia nervosa: neural mechanisms and the impact of starvation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(11):1168–76.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington: Author; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The biology of human starvation (2 volumes). Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press; 1950.

Benau EM, Orloff NC, Janke EA, Serpell L, Timko CA. A systematic review of the effects of experimental fasting on cognition. Appetite. 2014;77:52–61.

Buhren K, Mainz V, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Schafer K, Kahraman-Lanzerath B, Lente C, et al. Cognitive flexibility in juvenile anorexia nervosa patients before and after weight recovery. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2012;119(9):1047–57.

Article Google Scholar

Telleus GK, Fagerlund B, Jepsen JR, Bentz M, Christiansen E, Valentin JB, et al. Are weight status and cognition associated? An examination of cognitive development in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa 1 year after first hospitalisation. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2016;24(5):366–76.

Lang K, Stahl D, Espie J, Treasure J, Tchanturia K. Set shifting in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa: an exploratory systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(4):394–9.

Taylor SE. Adjustment to threatening events: a theory of cognitive adaptation. Am Psychol. 1983;38(11):1161–73.

Frolich J, Palm CV, Stoving RK. To the limit of extreme malnutrition. Nutrition. 2016;32(1):146–8.

Robinson P, Jones WR. MARSIPAN: management of really sick patients with anorexia nervosa. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(1):20–32.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Google Scholar

Garner DM. Eating disorder Inventory-3. Professional manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2004.

Clausen L, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O, Rokkedal K. Validating the eating disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3): a comparison between 561 female eating disorders patients and 878 females from the general population. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2011;33(1):101–10.

Wechsler D. WAIS-III WMS-III technical manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2002.

Brickenkamp R, Schmidt-Atzert L, Liepmann D. The d2 test of attention – revised. A test of attention and concentration. Oxford: Hogrefe; 2016.

Brickenkamp R. d2-testen – en vurdering af opmærksomhed of koncentration. Dansk vejledning. Hogrefe Psykologisk Forlag: Frederiksberg; 2006.

Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale—fourth edition. Technical and interpretive manual. Pearson: San Antonio; 2008.

Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan executive function system - technical manual. Pearson: San Antonio; 2001.

Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual Revised and Expanded. 2nd edition ed. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1993.

Tulsky D, Zhu J, Ledbetter M, editors. WAIS-III WMS-III technical manual (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale & Wechsler Memory Scale) paperback updated. USA: The Psychological Corporation; 2002.

Iverson GL. Interpreting change on the WAIS-III/WMS-III in clinical samples. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2001;16(2):183–91.

Bradley SJ, Taylor MJ, Rovet JF, Goldberg E, Hood J, Wachsmuth R, et al. Assessment of brain function in adolescent anorexia nervosa before and after weight gain. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19(1):20–33.

Lauer CJ, Gorzewski B, Gerlinghoff M, Backmund H, Zihl J. Neuropsychological assessments before and after treatment in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:129–38.

Tenconi E, Santonastaso P, Degortes D, Bosello R, Titton F, Mapelli D, et al. Set-shifting abilities, central coherence, and handedness in anorexia nervosa patients, their unaffected siblings and healthy controls: exploring putative endophenotypes. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(6):813–23.

Steinglass JE, Walsh BT, Stern Y. Set shifting deficit in anorexia nervosa. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12(3):431–5.

Konstantakopoulos G, Tchanturia K, Surguladze SA, David AS. Insight in eating disorders: clinical and cognitive correlates. Psychol Med. 2011;41(9):1951–61.

Abbate-Daga G, Amianto F, Delsedime N, De-Bacco C, Fassino S. Resistance to treatment and change in anorexia nervosa: a clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):294.

Guarda AS. Treatment of anorexia nervosa: insights and obstacles. Physiol Behav. 2008;94(1):113–20.

Stoving RK. Mechanisms In Endocrinology: Anorexia nervosa and endocrinology: a clinical update. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;180(1):R9–r27.

Barona M, Brown M, Clark C, Frangou S, White T, Micali N. White matter alterations in anorexia nervosa: evidence from a voxel-based meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;100:285–95.

Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449–61.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mogensen J. Reorganization of the injured brain: implications for studies of the neural substrate of cognition. Front Psychol. 2011;2:7.

Tchanturia K, Lounes N, Holttum S. Cognitive remediation in anorexia nervosa and related conditions: a systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22(6):454–62.

Bando N, Watanabe K, Tomotake M, Taniguchi T, Ohmori T. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with a hypoglycemic coma in anorexia nervosa. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(5):372–4.

Dobson KS, Dozois DJ. Attentional biases in eating disorders: a meta-analytic review of Stroop performance. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23(8):1001–22.

Schilder CMT, van Elburg AA, Snellen WM, Sternheim LC, Hoek HW, Danner UN. Intellectual functioning of adolescent and adult patients with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(5):481–9.

Lena SM, Fiocco AJ, Leyenaar JK. The role of cognitive deficits in the development of eating disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14(2):99–113.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Jesper Mogensen at the Unit for Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, for his inputs regarding neurocognitive reorganization and the possibility of extending his model to the research field of anorexia nervosa.

The study was supported by government funding: The Psychiatric Research Fund of Southern Denmark (grants for material and PhD salary) and the University of Southern Denmark (faculty scholarship). Furthermore, the study was supported with grants for material by private funds: the Jascha Foundation and the Beckett Foundation. The funding sources had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, analysis, or publication of the study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Eating Disorder, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

Simone Daugaard Hemmingsen & René Klinkby Støving

Research Unit for Medical Endocrinology, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Open Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN), Odense, Denmark

The Research Unit, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Mental Health Services in the Region of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Centre for Telepsychiatry, Mental Health Services in the Region of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Mia Beck Lichtenstein

Department of Psychology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Eating Disorder Unit, Mental Health Centre Ballerup, Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark

Alia Arif Hussain & Jan Magnus Sjögren

Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SDH and RKS completed the data collection. RKS was the initiator of the project. SDH, RKS, and MBL all took part in the design of the study. SDH, RKS, MBL, JMS and AAH were all contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Simone Daugaard Hemmingsen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The research project has been approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for the Region of Southern Denmark and was carried out in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. The authors state that the patient has given written and informed consent for participation in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors state that the patient has given written and informed consent for publication of the case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. None of the authors have received financial support or benefits from commercial sources for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hemmingsen, S.D., Lichtenstein, M.B., Hussain, A.A. et al. Case report: cognitive performance in an extreme case of anorexia nervosa with a body mass index of 7.7. BMC Psychiatry 20 , 284 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02701-1

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2020

Accepted : 28 May 2020

Published : 05 June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02701-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive performance

- Neuropsychology

- Undernutrition

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Eating Disorder Treatment and Recovery

- Bulimia Nervosa: Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment

Helping Someone with an Eating Disorder

- Orthorexia Nervosa: Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment

Binge Eating Disorder

- Body Shaming: The Effects and How to Overcome it

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): What it is, How it Helps

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

- Online Therapy: Is it Right for You?

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness

- Children & Family

- Relationships

Are you or someone you know in crisis?

- Bipolar Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Grief & Loss

- Personality Disorders

- PTSD & Trauma

- Schizophrenia

- Therapy & Medication

- Exercise & Fitness

- Healthy Eating

- Well-being & Happiness

- Weight Loss

- Work & Career

- Illness & Disability

- Heart Health

- Learning Disabilities

- Family Caregiving

- Teen Issues

- Communication

- Emotional Intelligence

- Love & Friendship

- Domestic Abuse

- Healthy Aging

- Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

- End of Life

- Meet Our Team

What is anorexia nervosa?

Types of anorexia, am i anorexic, signs and symptoms of anorexia, anorexia causes and risk factors, effects of anorexia, getting help, anorexia treatment, tip 1: understand this is not really about weight or food, tip 2: learn to tolerate your feelings, tip 3: challenge damaging mindsets, tip 4: develop a healthier relationship with food, helping someone with anorexia, anorexia nervosa: symptoms, causes, and treatment.

Are you or a loved one struggling with anorexia? Explore the warning signs, symptoms, and causes of this serious eating disorder—as well as how to get the help you need.

Anorexia nervosa is a serious eating disorder characterized by a refusal to maintain a healthy body weight, an intense fear of gaining weight, and a distorted body image. Anorexia can result in unhealthy, often dangerous weight loss. In fact, the desire to lose weight may become more important than anything else. You may even lose the ability to see yourself as you truly are.

While it is most common among adolescent women, anorexia can affect women and men of all ages. You may try to lose weight by starving yourself, exercising excessively, or using laxatives, vomiting, or other methods to purge yourself after eating. Thoughts about dieting, food, and your body may take up most of your day—leaving little time for friends, family, and other activities you used to enjoy. Life becomes a relentless pursuit of thinness and intense weight loss. But no matter how skinny you become, it’s never enough.

The intense dread of gaining weight or disgust with how your body looks, can make eating and mealtimes very stressful. And yet, food and what you can and can’t eat is practically all you can think about.

But no matter how ingrained this self-destructive pattern seems, there is hope. With treatment, self-help, and support, you can break the self-destructive hold anorexia has over you, develop a more realistic body image, and regain your health and self-confidence.

There are three types of anorexia:

- Restricting type of anorexia is where your weight loss is achieved by restricting calories (following drastic diets, fasting, exercising to excess).

- Purging type of anorexia is where your weight loss is achieved by vomiting or using laxatives and diuretics.