Funding opportunities for research, knowledge exchange and impact

Finding the right funding opportunity for you.

Here we share a range of popular internal and external funding opportunities for social sciences researchers and academics. These funding schemes are either managed internally or externally, and are either open to applications, and/or further rounds may be open to applications in future.

John Fell Fund

To foster creativity and a proactive approach to research opportunities in all subject areas, particularly interdisciplinary fields.

Strategic Research Fund

To build lasting research capacity through major transformative investments in researchers and research, and impact at scale.

To accelerate research and innovation, resulting in impact on a local level to a global scale.

Business Engagement Seed Fund

A flexible fund, designed for those who are starting to think about collaborating with businesses.

Engagement Fellowships

To enable social scientists to engage with non-academic stakeholders and build lasting partnerships and research impact.

Interdisciplinary Hubs

To establish, organise and/ or catalyse interdisciplinary communities ready to apply for significant external research funding in the relevant subject area.

Fixed-term Researchers Support Fund

To support fixed-term research staff with career development, and research and impact-related activities.

Stay up to date with the latest opportunities

Monthly funding and opportunities digest.

The Social Sciences Research, Impact, and Engagement (RIE) Team curates and circulates the latest opportunities in an easy to read monthly newsletter. It primarily focuses on research, impact, and engagement funding suitable for researchers in the social sciences but also includes regular calls, annual competitions, prizes, and one-off funding schemes. Simply select your career stage and preferences when you subscribe to receive opportunities of most interest to you or visit the RIE SharePoint to browse all items.

Subscribe to the Funding and Opportunities Digest

Browse all open and upcoming opportunities on the RIE SharePoint

All the information in the Funding and Opportunities Digest is accessible anytime on our SharePoint site too, along with resources and guidance on how to apply. Don't forget, the RIE team are available to help with applications, advice and more details.

Explore the latest funding opportunities and guidance on our SharePoint

For bespoke funding opportunities, we also suggest logging on to Research Professional using your University email address, where you can set up your own, regularly updated, funding email alerts. Information on using Research Professional can be found here . We also advise you to subscribe to the mailing lists of key funders: Research England , UKRI , ESRC , Leverhulme Trust , and the British Academy .

Funding support

Support for researchers in the Social Sciences Division is provided locally in each department; from the Research, Impact and Engagement (RIE) team in the Division; and centrally in the Research Services Grants team:

Departmental support

All departments in the Social Sciences Division have staff providing support and guidance for researchers making a funding application. Researchers are advised to contact their department in the first instance to discuss their proposed application, develop the associated budget, and obtain departmental approval prior to submission.

Find your departmental research support staff

Divisional support

Members of the Division’s Research, Impact and Engagement (RIE) team specialise in providing guidance and support on various aspects of research funding. The RIE team also provides bespoke training, advice, and funding information seminars for departments, research centres and researchers at particular career stages. Please contact:

Dr Alex Martalogu

Sarah Mallet (on maternity leave)

For planning of impact and non-academic engagement within your research design, contact:

Tom Korff - Senior Impact and Engagement Manager

Samantha Harper - Research Impact Facilitator

Key contact point for DSPI, Sociology and Education

Francesca Richards - Research Impact Facilitator

Key contact for SAME and SOGE

Rebecca Jones - Research Impact Facilitator

Key contact for Economics, ODID and OSGA

Becky Launchbury - ESRC IAA Manager

For support with ESRC Impact Acceleration Account applications and HEIF Social Science Engagement Fellowships

Simon Guillaume - Innovation and Business Partnerships Manager

For support with business engagement and innovation/commercialisation of research, Strategic Innovation Fund and BE Seed Fund

Noora Kanfash - Public Policy Facilitator

For support with research engagement with public policy

University support

University central support teams provide specialist advice and guidance about research funding, application submission, contract negotiation and post-award management to departments and Principal Investigators through:

Research Services

Finance division: research accounts.

Oxford University Innovation Ltd

Before you apply.

Please speak to your departmental research support team in the first instance. Each department may have an internal selection process for particular funding opportunities with a bespoke deadline. If you are considering applying through Oxford, please contact the appropriate department. Before you apply, consider...

- The funder: Every funder has its own aims for investing in research. Discuss your research design with your departmental research support staff to make sure it aligns with the funder’s aims, in order to increase your chance of success.

- Eligibility: Many funding schemes have applicant eligibility criteria, so make sure you comply before you apply.

- Resources: Many funding schemes will have a defined envelope of funds available, and some will have rules about what this can be spent on. It is worth checking the resource implications for your research design.

- Research design: Make sure your research is designed to answer the questions/objectives of the research, and with sufficient resource to management for successful delivery.

- Career stage: Research funding can be used to develop and demonstrate your career trajectory, build a portfolio with credible levels of management for successful delivery.

- Reviewing the application: Every successful research application has been reviewed. This is useful both within your discipline to recognise any gaps in knowledge, but also outside of your discipline to ensure that you have made a coherent argument that a multi-disciplinary panel would appreciate.

- How to Apply for Research Funding at Oxford

The Faculty of Law welcomes enquiries from all legal researchers interested in applying for funding through the University of Oxford. The faculty’s team of research facilitators can support high-quality applications, whether you’re an internal or external candidate, an early career researcher or established professor.

The majority of funding for research in the faculty is provided by external sources, though small activities can be funded internally. Applications for longer term (1 year+) research activities will generally need to be funded by external grants, though there are also smaller internal funding schemes that may be useful.

Main types of research grant

Fellowships – fixed-term grants for individuals to conduct independent research as an employee at Oxford.

Projects – funding for a small team of researchers led by a Principal Investigator (PI). Usually for multi-year projects with phased activities.

Events – grants for organising academic workshops and conferences, or public engagement events.

Research grant aims

Some research grants have specific aims, such as:

Early Career – the definition of an early-career scholar differs between funders, but typically such schemes focus on funding researchers moving on from their doctorate and seeking to establish themselves in academia.

Collaboration – grants specifically designed to build research collaboration across different institutions, either nationally or internationally.

Impact / Knowledge Exchange / Public Engagement – schemes to make difference beyond academia, promote mutual exchange between academia and industry, or the dissemination of academic research.

Capacity Building – This could be defined as building the skills and experience of individual researchers or building research capacity institutionally or nationally.

Career Development – some fellowships can be aimed at career development specifically, while project grants can include the aim of career development for junior researchers employed on the project.

Seed Funding – small grants to kick-start research projects or collaborations, in the hope they lead to bigger things.

Small Grants – there are numerous small grants available for a variety of research activities. Internal opportunities are available from the Faculty website and external grants via Research Professional .

Each funding scheme has its own rules, eligibility criteria, duration, and award amount, depending on the funder and the purpose behind the grant. Many early career grants require applicants to have an institutional mentor , who will support the application and provide mentoring should it be funded. It is important to read the guidance notes which accompany all funding schemes to check these details before starting an application.

Post Doctoral Fellowships

Managing research posts in the faculty of law, research posts in the faculty of law: mentoring, types of funders.

There are many different bodies who provide research funding. Below are a few of the common funders that you could apply to through the Faculty of Law.

UK Research and Innovation

- Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

- Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)

Government Departments

- Independent Social Research Foundation

- Leverhulme Trust

- Nuffield Foundation

- Wellcome Trust

British Academy

European union.

- European Research Council

- Horizon Europe

- Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship

University of Oxford

Application process.

Idea - Think about what sort of research you want to conduct and the research questions you want to answer. Research potential funding schemes which might be suitable, either on our listing pages, or through funder websites. Some regular calls require expressions of interest and may have an internal selections process. If you’re an early career researcher, you’ll need to find a mentor in Oxford, who is willing to support your application and your research.

Enquiry - Contact research support and submit a formal or informal expression of interest, on applying for funding. They will then advise on funding opportunities and explain the process of applying through Oxford.

First draft - Write out a first draft of your application. Be sure to ask peers and senior academics to review it, and ask the advice of your research facilitator.

Internal selection (if required) - Some funding schemes limit the number of applicants from one institution, so you may have to pass internal selection.

Redraft - Continue to hone your application with the help of your research facilitator.

Budget - You will need your research facilitator's help to draw up a budget, based on the research you want to conduct. These can be simple or complex depending on the project. But keep in mind a rough budget from the start, as this will shape your research plan.

Submit - The final version of the application and budget are then submitted to the faculty for internal validation and adding any support statements required. This is forwarded to Research Services for review. Depending on the funder, the applicant or Research Services (on behalf of applicant) submit the final application.

Award - The funder will then make a decision. If you receive an award, this will usually go to the University directly, who will then get everything in place so you can carry out the proposed research.

Research - Carry out the proposed research at the Faculty of Law.

More details about the application process can be found on the Research Services webpages .

Search our current funding opportunities

- Upcoming Research Funding Opportunities

Funding Opportunities with no deadline - Open Calls

Oxford internal research funding opportunities.

- Funding and Managing Projects

On this page

Related information, related websites.

- Our research

- Our research groups

- Our research in action

- Research funding support

- Summer internships for undergraduates

- Undergraduates

- Postgraduates

- For business

- For schools

- For the public

- Fellowship applications

We have a team of in-house experts, our research facilitators, that support researchers with every step of the application process for research funding – from identifying opportunities to advising on content, checking compliance and costing projects.

Securing ongoing funding for research is an essential part of a researcher’s job – but it can be time-consuming and, often, overwhelming. Our research facilitators work closely with funding bodies and researchers alike; they have extensive experience of the funding landscape and the complexities of submitting timely and successful proposals. The team works with both members of the Department of Physics as well as external fellowship applicants and submits some 250 grant applications every year, of which around 100 are fellowship applications.

You are very welcome to meet with a member of the facilitation team at any time for a one-to-one discussion about funding and grant applications. Please do get in touch to arrange a meeting through [email protected] or [email protected] .

Meet the team

Head of Research Facilitation: Hannah Lingard

Senior Research Facilitator: Bryony Elbert

Senior Research Facilitator and Mentoring Coordinator (MHFA): Jenny Woods

Research Facilitator (MHFA and EDI Champion): Nicole Malloy

Research Facilitator: Charlie Garner

Supporting fellowship applications

We support candidates with a range of postdoctoral and early career fellowship applications; if you would like to apply for a fellowship within the Department of Physics, please contact us at [email protected] referencing the particular scheme you are interested in.

For details about DPhil admissions and funding please refer to the department and university graduate admissions and funding pages. This is outside of the remit of our team.

https://www.ox.ac.uk/admissions/graduate

https://www.ox.ac.uk/admissions/graduate/courses/mpls/physics

- News & Comment

- Our facilities & services

- Current students

- Staff intranet

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

- Accessibility

Research Strategy and Funding

Our mission is to enhance and enable high quality, impactful research

In the Research Strategy and Funding Team, we create and enrich opportunities for researchers to apply for funding, and to collaborate and engage with stakeholders. We develop strategy, policy and processes that advance excellence in research and the research environment. Our team is a trusted source of information and expertise; we work to promote connectivity and drive progress in the research ecosystem.

For research enquiries please contact Leila Whitworth in the first instance. For enquiries about internal funding opportunities please email [email protected] .

Strategy and Support

- Research themes and research partnerships

- Advancing positive research culture

- Research assessment, including the Research Excellence Framework

- Engagement, including public engagement, policy engagement, innovation and knowledge exchange

- Major prize nominations

- Policy for naming new research centre (SSO required)

- Researcher's Toolkit

Facilitating external research funding

- Coordinating and supporting major bids to external funders including:

- Large strategic bids and calls that require a single institutional bid

- Calls that have a cap on the number of applications

- Supporting strategic bids with institutional commitment and letters of support

- Relationship management for key research funders

Managing internal research funding

- John Fell Fund

- Medical Sciences Internal Fund: Pump Priming

- MSD Bridging Salary Scheme

- Supporting and assessing bids to other centrally managed internal funds

Academic Lead

Heidi Johansen-Berg

Associate Head of Division (Research)

Head of Research

Leila Whitworth

Head of Research Strategy and Funding Team

Research Team

Goher Ayman

Governance Manager

Research Strategy & Funding Administrator

Regula Dent

Executive Assistant to the Director of Global Health

Naomi Gibson

Public and Policy Engagement Facilitator

Eliya Lucks

Communications Officer (Research)

Joanna Miller

Global Health Facilitator

Maddie Mitchell

Leadership Development Officer

Research Culture Facilitator

Sally Pelling-Deeves

Immunology Research Facilitator

Shelly Stringer

Research Evaluation Manager

Afroditi Tsourgianni

Translational Research Funding Administrator

Michelle Wilson

Research Culture Project Officer

Adelyn Wise

Research Funding Manager

Michael Youdell

Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre Director of Translational Research ...

SUPPORT AVAILABLE IN RESEARCH SERVICES

ODA funding

Which calls are available for oda research.

GCRF calls from the Research Councils are published on Research Professional. Visit Research Professional for an up to date list of current and upcoming opportunities

Other ODA funding opportunities

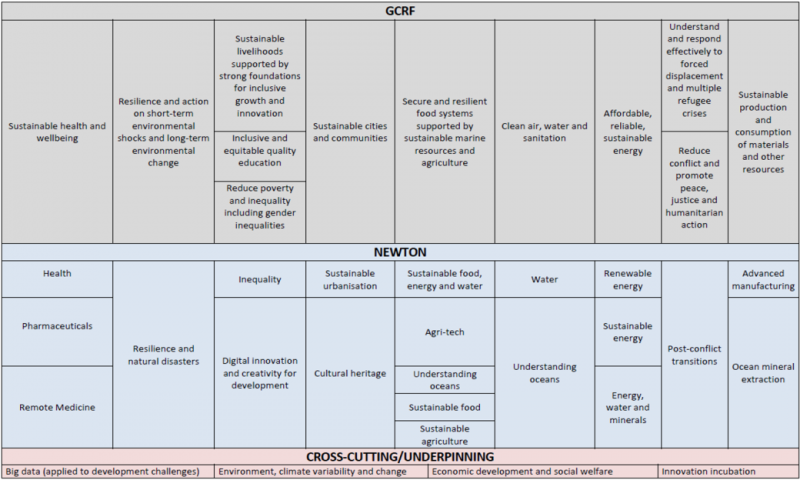

GCRF forms a portfolio with other funding sources such as UK Department for International Development (DfID), Ross Fund, Global Health Research and Grand Challenges. More information can be found in UK Research for Sustainable Development (PowerPoint) and DFID health research funding (PowerPoint). Newton Fund has previously been referred to as the ‘little brother’ of GCRF and could be used as pump priming for GCRF.

Please note that there are different geographical constraints on different funding sources. Particularly, Newton Fund largely focuses on specific middle-income countries and European funding usually requires a minimum of three partners in EU or associated countries in an application.

UKCDR lists funding opportunities across many of the UK ODA funders, and provides a lot of resources.

UUK also has a Gateway to International Opportunities

Research Professional also has a list of development funding for Africa and the Caribbean . Note that the primary scope is international development funding, not research, but there may be opportunities for academic institutions to apply.

Please check the Research Support funding pages for more information on funding.

Newton Fund

For full listings of Newton Fund opportunities, see the Newton Fund website .

Newton Fund funds people and capacity building, research collaboration and translation into capacity building.

Although it varies by call, countries Newton Fund are partnering with are: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, South Africa and wider Africa, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam.

Synergies between GCRF and Newton Fund themes

Created by Dr Carolyn Barker at the University of Kent. This provides a useful breakdown of current funding for Newton Fund and GCRF. Source: https://sciencefundingblog.wordpress.com/2017/07/27/navigating-the-latest-gcrf-and-newton-funding-calls-july-2017/

Department for International Development

Department for International Development (see also UKCDR information on DfID funding ) funds research in LMICs. The DFID Research Review (October 2016) sets out DfID's planned investment of approximately £390 million per year over the next four years.

Their current priority areas are:

- Fragile and conflict states

- Climate, energy and water

- Agriculture

- Economic development

Ross Fund (see also the UKCDR page on the Ross Fund ): This is managed by DfID and the Department of Health and is a £1 billion fund for research and development in products for infectious diseases. Particularly: antimicrobial resistance, diseases with epidemic potential, and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

European Commission

Some EC-funded calls are relevant specifically to LMICs, and others may be applicable.

Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme : this programme (2014-2020) funds research across all disciplines. A large portion of the H2020 budget is directed to multi-institution, multi-country collaborative projects under the Societal Challenges pillars.

A key tenet of the GCRF programme is that the work is carried out in a country or countries on the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) list . Most, but not all, of the countries on the DAC list are eligible to receive funds directly from the European Commission. The countries that are eligible to receive funding are:

- Any of the current 27 EU member states

- Any of the countries who are currently associated to Horizon 2020

- Any overseas territories or countries on this list

For more information on eligibility and EC funding, see the GCRF/EC factsheet .

For more information on EC funding, see the European Research Funding pages .

Wellcome Trust

Wellcome Trust offer funding for different levels of research (individual, groups, major initiatives etc) in: biomedical science; population health; product development and applied research; humanities and social science; and public engagement and creative industries. Much of the funding is available for ODA-related research.

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funds research in global health (HIV, malaria, NTDs, pneumonia, TB) and development (agricultural, emergency, family planning, global libraries, maternal, newborn and child health, nutrition, polio, vaccine and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Other ODA funders

Elrha - Research for health in humanitarian crises : Elrha funds research to improve health outcomes by strengthening the evidence base for public health interventions in humanitarian crises.

EqUIP - EU-India Social Science and Humanities Platform : This platform funds collaborative research between EU countries and India. The research priority themes are: sustainable prosperity, well-being and innovation; inequalities, growth and place/space; social transformation, cultural expressions, cross-cultural connections and dialogue; power structures, conflict resolution and social justice; and digital archives and databases as a source of mutual knowledge.

Grand Challenges Canada : Eligibility for UK institutions varies, so check details of individual calls.

NORFACE ERA-NET : Focusing on Europe, with some ODA relevant funding, NORFACE is a collaborative partnership between national research funding agencies (including RCUK).

NB: This is not intended to be a comprehensive list.

How to apply

Refer to the Application pages on the Research Support website for details of the funding application process at Oxford.

Related links

- Research Professional - GCRF search

- Newton Fund partner country information

- UKCDR website - funding opportunities

- UUKi webpages - International funding opportunities

- Oxford Research Support website - funding information

Oxford's International Research

COVID-19 FUNDER GUIDANCE

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Science and Public Policy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. background, 5. discussion, 6. conclusions, acknowledgements, supplementary data, conflict of interest statement., data availability, the impact of winning funding on researcher productivity, results from a randomized trial.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Adrian Barnett, Tony Blakely, Mengyao Liu, Luke Garland, Philip Clarke, The impact of winning funding on researcher productivity, results from a randomized trial, Science and Public Policy , 2024;, scae045, https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scae045

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The return on investment of funding science has rarely been accurately measured. Previous estimates of the benefits of funding have used observational studies, including regression discontinuity designs. In 2013, the Health Research Council of New Zealand began awarding funding using a modified lottery, with an initial peer review stage followed by funding at random for short-listed applicants. This allowed us to compare research outputs between those awarded funding or not using a randomized experimental study design. The analysis included eighty-eight researchers who were followed for an average of 3.8 years of follow-up. The rate ratios (and 95 per cent credible intervals (CI)) for funding were 0.95 (95 per cent CI 0.67 to 1.39) for publications and 1.06 (95 per cent CI 0.79 to 1.43) for citations, showing no clear impact of funding on research outputs. The wider use of funding lotteries could provide robust estimates of the benefits of research funding to better inform science policy.

Public and philanthropic funding for health and medical research has been estimated to exceed more than $100 billion annually, with the ten largest research organizations contributing around 40 per cent of this funding ( Viergever and Hendriks 2016 ). Given the size of this investment, there has been much interest in quantifying both the private and social returns from medical research ( Murphy and Topel 2010 ) and medical innovation more generally ( Jones and Summers 2020 ).

Over the last two decades, the credibility revolution has led to the widespread use of quasi-experimental methods to measure policy impact, including research funding. A range of studies, mainly exploiting the regression discontinuity design, have been used to look at the impact of research funding on productivity-related outcomes ( Jacob and Lefgren 2011 ; Benavente et al. 2012 ; Yang, Jones, and Wang 2019 ). In this study, we take a different approach, in which we take advantage of the use by a funding agency of a modified lottery, in which they randomly assigned funding to projects deemed to be of sufficient quality to be worth funding.

Our paper has four sections. After reviewing relevant literature on measuring research productivity and the increasing use of modified lotteries as a rationing allocation mechanism, we detail and analyse outcomes from a randomized policy experiment. Our study takes advantage of the Health Research Council (HRC) of New Zealand Explorer Grant scheme, which was the first in the world to use a modified lottery to allocate research funding ( Liu et al. 2020 ). The methods used, which were based on prespecified protocol ( Barnett et al. 2022 ), are then outlined. We then present the results from eighty-eight researchers who were followed for a total of 331 researcher years (average of 3.8 years per researcher; see Supplementary material S.1 ). In our final section, we discuss the key results as well as practical aspects of the experiment and implications for future randomized funding trials to measure the impact of research funding.

2.1 Quantifying research productivity

There has long been interest in finding ways to measure the impact of funding on research productivity, including Jaffe (2002) who set a framework that was an adaption of the standard panel data model:

where Y i, t is a measure of research output (e.g. count of peer-review papers) by researcher i in time period t . This output is dependent on multiple factors related to the researcher and time. The D i is a dummy variable indicating if the researcher received grant funding (in which case D i = 1, otherwise D i = 0). The effect of funding for researcher i is β i , which in practice is often estimated as an overall average ( β ). The X i, t is a vector of observable and time-dependent characteristics of the researcher; α i is the researcher fixed effect and µ t is the time period effect. Jaffe adds ω i, t , which like X i, t is a time-dependent characteristic of the researcher but is unobservable. Finally, there is an error term ϵ i, t with the usual properties of independence and homoscedasticity.

Jaffe notes that attempts to measure productivity by comparing the outputs ( Y i, t ) of funded and unfunded researchers are problematic, as the productivity impact of funding β i is likely to be correlated with α i and ω i, t , which are unobservable. This is because decisions about research grants can be influenced by factors such as the researchers’ experience and prestige ( Hultgren, Patras, and Hicks 2024 ), so estimates of β i using observational data would likely suffer from selection bias.

Jaffe proposes two approaches to creating unbiased estimates of β i . The first is random allocation in which the funding agency would have a process that identifies a group of potential grantees based on α i and ω i, t , and randomly award grants within this group. As the effect of grant funding β i is no longer correlated with α i and ω i, t , equation (1) can be used to estimate the impact of winning funding ( D i ) on outputs ( Y i, t ). While Jaffe regards random allocation as the ‘gold standard’ for the evaluation of research funding, the reluctance of funding agencies (at that time) to implement it means that instead he focused on quasi-experimental methods such as use of regression discontinuity designs for quantifying the impact of funding ( Jaffe 2002 ).

Using a regression discontinuity design to estimate the impacts of funding was originally proposed by Thistlethwaite and Campbell (1960) and has been adopted in several studies for measuring the effect of both research funding and more generally research and development expenditure. As Jacob and Lefgren (2011) note, ‘the intuition behind the regression discontinuity design is that if one compares applicants just above and just below some prespecified cut-off, there will be little, if any, difference in unobservable determinants of productivity, but a large difference in the likelihood of receiving funding’.

Regression discontinuity designs have been used in several empirical studies, including Chile’s FONDECYT programme, which has a positive impact (of around two additional publications in 6 years) ( Benavente et al. 2012 ). Jacob and Lefgren (2011) , using US data, find similar or smaller returns for National Institute of Health postdocs. A more recent analysis of NIH R01 grants actually shows the opposite, as near-miss applicants who stay in academia had similar productivity in terms of numbers of papers but actually performed better on other metrics, such as citations per paper, with the authors speculating that an early career setback may actually have a positive impact on productivity ( Yang, Jones, and Wang 2019 ).

2.2 Rise of modified lotteries

Lotteries have long been advocated for the allocation and financing of public goods ( Franke and Leininger 2014 ) and of indivisible goods ( Sher 1980 ). Historically, lotteries have been used in a surprising number of different contexts, including to select political and religious leaders ( Huntsman 1996 ; Taylor 2007 ), to choose marriage partners in some religions ( Sommer 1998 ), and even allocate the death penalty in Sweden among multiple felons ( Binde 2014 ). In recent years, lotteries have been used in the allocation of scarce products and services, including vehicle licences in polluted cities ( Li 2018 ) and health insurance ( Baicker and Finkelstein 2011 ).

Over the last two decades, lotteries have been increasingly advocated in the allocation of research funding ( Avin 2019 ; Shaw 2022 ). Such proposals follow Jaffe’s earlier proposal in which grant applications are assessed in a first stage to find those that are considered meritorious in terms of meeting or exceeding a certain threshold. In a second stage, meritorious grant applications are entered into a lottery to determine which ones are funded ( Fang and Casadevall 2016 ). A variation on a simple modified lottery is to assign applications to one of three categories: fund; do not fund; and third middle category that involves allocation by lottery; this approach has recently been supported by a Nature editorial ( Editorial 2022 ).

Research funders have implemented various modified lotteries, starting with the HRC of New Zealand in 2013. This has been followed by at least four European funders, including the Volkswagen Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Austrian Science Fund FWF, and the British Academy. While the lotteries differ in design, all use a modified lottery to allocate research funds.

Why are lotteries now starting to be used by research funders? Although there are likely a variety of objectives, there are some elements of the funding environment which suggest that lotteries are likely to be an increasingly efficient mechanism for allocating research funding. Consider Fig. 1 , which presents two hypothetical grant assessment processes in which research allocations are assessed by a funding organization using criteria that are intended to reveal researcher ‘quality’ ( ω ). We assume that after an assessment process, the applications are ranked from lowest to highest ω , and we also assume that there is a threshold ω * , which is a ‘quality’ threshold above which the funding organization deems that the proposal would be worth funding. Note, for this illustration, we ignore any error in measuring ω .

Hypothetical curves showing researcher quality against the ranking of their applications.

In Fig. 1a , we represent the case where there are two distinct types of grant applications, high quality and low quality. If there are no funding constraints, it would make sense for the funding organization to fund all projects ranked above the N %.

A widespread recent feature of the research funding environment has been declines in the proportion of applications receiving funding. Typically, this has been attributed to the large increase in the number of applications combined with stable budgets. Funding success percentages of 20 per cent or below are common across many medical schemes ( Herbert et al. 2013 ; Narahari et al. 2018 ); this funding environment is characterized by Fig. 1b . Here, a high proportion of grant applications exceed N %, but the funding organization only has a budget to support applications above N * %. In this competitive environment, with many applicants having a similar quality, there are potential advantages of allocation via a modified lottery, i.e. randomly draw applications that exceed ω * until the budget is expended. One potential advantage is the time saving for peer reviewers, who now only need to assess if an application is fundable rather than a more delineated score or categorical rating.

2.3 Modified lottery used by the HRC of New Zealand

In 2013, the HRC of New Zealand began using a modified lottery to award fellowship funding for health researchers for their Explorer Grant scheme. These grants provide seed support for researchers with transformative, innovative, exploratory, or unconventional research ideas that have a good chance of making a revolutionary change to health in Aotearoa New Zealand. Applicants are awarded NZD $150,000 (approximately USD $95,000) for up to 2 years. The funding amount is fixed and for research working expense only. New Zealand must be the principal domicile and principal place of employment for the first named investigators. The application must have host institution support to cover research costs (e.g. salary) other than the research working expense supported by the HRC. Each application has a first named investigator, with the option to add other named investigators as part of the research team. The median number of Explorer Grants funded per year during 2015–2022 was thirteen with an annual budget of NZD $1.9 million.

Written applications undergo peer review, with the assessing committee members asked to confirm (Yes/No) two criteria: the research is potentially transformative and the proposal is exploratory but viable. Applications for which there is a majority agreement that the transformative and viability criteria are met will be considered as potentially fundable. These short-listed applications are funded at random until the annual budget is exhausted.

This modified lottery offered a world-first opportunity to study the impacts of research funding using a randomized controlled trial, where researchers were randomized to funding (treatment) or no funding (control). Awarding funding at random is novel and potentially controversial but the scheme has been generally well accepted by applicants ( Liu et al. 2020 ). Modified lotteries are increasingly being used in research, as funders and applicants appreciate that decisions in such a highly competitive system are already somewhat random ( Frey, Osterloh, and Rost 2023 ).

In this paper, we examine the careers of applicants who were and were not funded at random, creating the world’s first randomized trial of funding. We also comment on the differences between a randomized trial and regression discontinuity design.

This is a parallel group randomized trial. Researchers were randomized in annual application rounds. The single inclusion criterion was New Zealand researchers short-listed for the Explorer Grant scheme between 2015 and 2021. The single exclusion criterion was researchers who did not consent to our research team following their career and did not receive funding.

3.1 Allocation

Short-listed applications were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and randomized numbers were generated by New Zealand HRC staff using the ‘Rand’ function. The staff undertaking this randomization were not involved in the management of the Explorer Grant Round. Applicants were selected for funding up to the available budget in the order of smallest to largest random number.

The allocation ratio of funded to not funded was determined by the number of applicants who were short-listed and the available budget. Hence the allocation ratio varied from year to year, and in some years, all short-listed applicants were funded (see Supplementary material S.2 ). Receiving funding could not be blinded.

3.2 Consent

As part of their application, all applicants were asked if they were willing for our research team to follow their career if they did not win funding. The names of consenting applicants were given to the research team after each round was completed. We also included those who won funding, and applicants were informed that all publicly available data would be included.

Nonconsent could create bias if researchers who consented differed from those who did not consent. As the winners’ names are publicly available, we checked for any difference by comparing the previous research output of those who did and did not consent. No information was available on those who did not consent and did not win funding, but as funding was randomly allocated, we assumed that the available nonconsenting researchers represent all nonconsenting researchers. We compared consenters and nonconsenters by comparing their data at the time of their application. We compared their total number of papers and their time in research based on the year of their first publication.

The study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics committee and the University of Otago Human Ethics committee. The trial protocol was published online ( Barnett et al. 2022 ).

3.3 Outcomes

The list of primary and secondary outcomes is given in Table 1 .

Primary and secondary outcomes.

| Level . | Dependent variable . | Baseline adjustment . |

|---|---|---|

| Yearly paper counts | Total paper counts prior to randomization | |

| Yearly citation counts | Total citations prior to randomization | |

| Citations per paper as an annual average | Average citations per paper prior to randomization | |

| Altmetric score as an annual average | Average Altmetric score per paper prior to randomization |

| Level . | Dependent variable . | Baseline adjustment . |

|---|---|---|

| Yearly paper counts | Total paper counts prior to randomization | |

| Yearly citation counts | Total citations prior to randomization | |

| Citations per paper as an annual average | Average citations per paper prior to randomization | |

| Altmetric score as an annual average | Average Altmetric score per paper prior to randomization |

The predefined primary outcome is the number of published papers per year, which indicates the activity and output of researchers, and is a commonly used outcome in previous studies of research productivity (e.g. Gush et al. 2017 ). We acknowledge that annual paper counts are a relatively blunt outcome and do not measure the quality of the research.

We hypothesized that researchers with more funding would have more time to spend on research and be able to employ research assistants, meaning they would have more papers. Conversely, researchers who did not win funding may need to spend more time reapplying for funding and on teaching or service, giving them less time for research.

We extracted the researchers’ publication counts from three databases: Scopus, Google Scholar , and ResearchGate . Over 95 per cent of publications were journal articles, but other types were included (see Supplementary material S.4 ). In a change to the protocol we used the ResearchGate bibliographic database instead of ORCID as it had better coverage of the papers published by our sample.

A secondary outcome is annual citation counts, which aims to capture a researcher’s impact and relevance ( Aksnes, Langfeldt, and Wouters 2019 ). Citations have been used as an outcome in studies of the impact of research funding ( Fang, Bowen, and Casadevall 2016 ; Heyard and Hottenrott 2021 ). However, citations are an imperfect measure and can be bland ( Editorial 2017 ), inaccurate ( Pavlovic et al. 2021 ), manipulated ( Wren and Georgescu 2020 ), and variable between fields ( Aksnes, Langfeldt, and Wouters 2019 ). A related secondary outcome was the average number of citations per paper, which aims to measure a researcher’s relative impact ( Franceschet 2009 ).

Another secondary outcome was the annual average Altmetric score per researcher. Altmetric is an alternative metric for assessing the impact of published papers that include media attention, tweets, and blogs ( Elmore 2018 ). This outcome aims to cover the impact of the researchers’ papers outside of academia.

We examined employment by checking the researchers’ institutional pages and other online sources to discover if they were still employed in research, including at a university or other research organization. This information was collected once in December 2021 by a research assistant who was initially blind to funding but may have seen the researcher’s funding status during searching. We assumed that people were still employed in research if they reapplied and were entered into the lottery. We used a survival analysis to examine whether funding impacted on the chances of remaining employed in research.

3.4 Statistical methods

We changed the proposed statistical model from that planned in the protocol ( Barnett et al. 2022 ) prior to unblinding the data. We planned to examine the trajectory of the researchers’ outputs over their entire careers, including the years prerandomization. However, this created a spurious correlation between funding and annual outputs, because the HRC funding began in 2015, and the years prior to 2015 had generally lower research outputs for this cohort (see Supplementary material S.3 ). To avoid this confounding, we summed each researcher’s output prior to randomization and included this as a baseline predictor to capture prerandomization output ( Lepage et al. 2015 ).

We modelled the researchers’ annual publications in the years postrandomization with the independent variables of prerandomization publications and randomized funding group. The prerandomization publications were positively skewed; hence, we used a base 2 log-transform so that the parameter estimates are the effect of doubling prerandomization publications.

For each outcome, we also considered a delayed effect of funding by allowing a linear interaction between funding and year since randomization. This allowed any effect of funding to become weaker or stronger in the years after funding was awarded.

We jointly modelled all three databases and modelled the correlation between them, which avoided fitting separate models for all three databases that would create multiple testing of the same hypothesis. A benefit of this approach is that it avoided losing the five researchers who were not on Scopus (see Supplementary material S.4 ) as it allows missing data from one or two databases. The bibliometric data were collected mid-way through 2022 (23 July 2022), so we included an offset to account for the shorter follow-up time in the final year.

The annual number of publications and citations were modelled using a Poisson distribution with a log e link function. The results are presented as the rate ratios in publication and citation counts, with a rate ratio above one signifying a benefit to funding. The annual citations per paper and Altmetric outcomes were modelled using a Normal distribution, and the results are presented as absolute changes with positive changes signifying a benefit to funding.

Detailed model equations are in Supplementary material S.5 . We used a Bayesian paradigm, and so the estimates are given as rate ratios or differences with 95 per cent credible intervals and posterior probabilities that the group means do not differ instead of standard P -values ( Gelman et al. 2013 ). The exception is for the citation counts where the Bayesian model did not satisfactorily converge and hence these results are from a standard frequentist approach. We checked the residuals of all models for outliers and approximate normality.

The survival analysis for no longer being employed in research used a Cox model with right-censoring for those still employed at the end of data collection.

Data management and analysis were made using R version 4.3.1 ( R Core Team 2023 ). The code is available online here: https://github.com/agbarnett/hrc_trial .

3.5 Multiple entries

A difference from a standard randomized trial was that researchers could apply in multiple years, so the same researcher could be randomly allocated to both funding and not funding at different times. To account for this, we examined researchers’ outputs from their first to second randomization when they were censored. This censoring was repeated for all subsequent randomizations. This examines the impact of funding up to the next randomization, at which point a new follow-up is started. We included a random intercept for each researcher to allow for within-researcher correlation.

An observational study on the impact of funding avoided the technical issues of dealing with multiple entries by excluding multiple winners ( Benavente et al. 2012 ). However, this could introduce bias into the estimates by excluding highly successful researchers. It also reduces generalizability as the estimates are not applicable to multiple winners.

3.6 Study design: randomization versus regression discontinuity

Randomization adjusts for confounding by design, whereas regression discontinuity uses statistical adjusting to give unbiased estimates—conditional on the key assumptions being satisfied. Control for confounding by design is preferable to using statistical adjustments. We used a simulation study to show the increased statistical power of a randomized trial compared with regression discontinuity in the context of measuring research outputs (see Supplementary material B ).

A regression discontinuity design applied to funding uses the applications’ scores from peer review as the forcing variable. These scores control whether applicants fall above or below the funding line, and it is reasonable to expect that applications on either side of the line are similar up to some distance from the line. Applications within this similar window need to be similar, as if they were randomized. Scores from funding peer review are thought to be noisy ( Osmond 1983 ), which means randomness partly dictates scores, making the design potentially appropriate. A study of the variability in peer reviewers’ scores estimated that only 23 per cent was due to differences in the quality of the application, with the remaining 77 per cent due to noise and differences between reviewers ( Gallo, Sullivan, and Glisson 2016 ). This noise may be greater closer to the funding line, where the differences between applications are often razor-thin ( Osmond 1983 ).

Systematic differences in scores may occur near the funding line; for example, there may be more women just below the line due to gender biases ( Witteman et al. 2019 ). There could also be differences due to unknown or unmeasured characteristics, which would introduce confounding into the regression discontinuity design. For example, scores may be associated with applicants’ age, and although the strength of this association may be relatively weak, it would create differences between winners and losers. The impact of this difference could be minimized by choosing a narrow window around the funding line, but this reduces statistical power and potentially also generalizability.

Measured confounders can be statistically adjusted for, but in a randomized design, this is not required (although adjustments can reduce the overall error variance and hence reduce the uncertainty in estimates of treatment). Unmeasured or unknown confounders cannot be adjusted for in an observational study, but this will not matter in a randomized design.

The regression discontinuity design requires multiple model choices, including the window size in which applications are considered equivalent; what variables to adjust for; and the use of a regression model to adjust for the effect of scores, and the additional choice of whether the regression slope should be linear or smooth ( Cuesta and Imai 2016 ). These model choices can create a ‘garden of forking paths’ with potential multiple comparison issues and the selection of model choices where the results most suit the researchers’ beliefs ( Gelman and Loken 2013 ). The results of a regression discontinuity can be highly dependent on model choices, as shown in a critique of a design applied to election results ( Cuesta and Imai 2016 ). Researchers can use a weighted regression to reduce the importance of the window size but this shifts the arbitrary decision to the functional form of the weights. All these model choices should be prespecified in a protocol.

There were 123 applications to the HRC of New Zealand scheme over the 7 years that were deemed fundable . All 123 were eligible for inclusion in the trial and eighty-one (66 per cent) consented to be followed by the research team. Researchers who consented had 52 per cent more publications than those who did not consent (95 per cent credible interval (CI) 5 per cent to 121 per cent). The mean years of experience was seventeen for those who consented and fourteen for those who did not, with a 0.10 probability that the groups’ experience did not differ.

Eighty-one applications were randomly awarded funding and forty-two to no funding. There were 2 years with no randomization, as there was enough funding to award all applicants who were short-listed. The flow chart of participants is shown in Fig. 2 .

Flow chart of participants from the HRC of New Zealand trial.

Characteristics of the participants at the time of randomization are given in Table 2 , showing similar summary statistics in the funded and not funded groups.

Descriptive statistics for the participants at randomization.

| . | Funded . | Not funded . |

|---|---|---|

| 79 | 26 | |

| 2019 [2017, 2020] | 2020 [2019, 2020] | |

| 2001 [1993, 2008] | 1998[1989, 2006] | |

| publications | 52 [21, 93] | 55[30, 124] |

| publications | 30 [16, 62] | 46[27, 75] |

| publications | 29 [15, 59] | 40 [25, 69] |

| . | Funded . | Not funded . |

|---|---|---|

| 79 | 26 | |

| 2019 [2017, 2020] | 2020 [2019, 2020] | |

| 2001 [1993, 2008] | 1998[1989, 2006] | |

| publications | 52 [21, 93] | 55[30, 124] |

| publications | 30 [16, 62] | 46[27, 75] |

| publications | 29 [15, 59] | 40 [25, 69] |

The cells show the median [first quartile, third quartile]. The paper numbers are the totals at the time the applicant was randomized. The table includes all researchers who consented or were funded. Some participants were randomized more than once.

The estimated differences between researchers who were funded and not funded are given in Table 3 . There were no clear main effects of funding on any of the outcomes. For example, for yearly publication counts without a delayed funding effect, there is a mean rate ratio below one of 0.95 (95 per cent CI 0.67–1.39). For citations per paper and Altmetric , the mean differences showed a benefit to funding but with wide credible intervals.

Estimated differences between funded and not funded researchers from the HRC of New Zealand trial.

| Outcome . | Estimate . | With delay . | Mean . | 95% CI . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian | |||||

| Rate ratio | No | 0.95 | 0.67 to 1.39 | .73 | |

| Rate ratio | Yes | 0.97 | 0.66 to 1.44 | .86 | |

| Rate ratio | Yes | 0.95 | 0.71 to 1.28 | .75 | |

| Absolute | No | 1.4 | −4.5 to 7.5 | .66 | |

| Absolute | Yes | 0.8 | −5.1 to 6.8 | .79 | |

| Absolute | No | 4.3 | −5.9 to 14.4 | .41 | |

| Absolute | Yes | 2.9 | −7.7 to 13.4 | .59 | |

| Non-Bayesian | |||||

| Rate ratio | No | 1.06 | 0.79 to 1.43 | .68 |

| Outcome . | Estimate . | With delay . | Mean . | 95% CI . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian | |||||

| Rate ratio | No | 0.95 | 0.67 to 1.39 | .73 | |

| Rate ratio | Yes | 0.97 | 0.66 to 1.44 | .86 | |

| Rate ratio | Yes | 0.95 | 0.71 to 1.28 | .75 | |

| Absolute | No | 1.4 | −4.5 to 7.5 | .66 | |

| Absolute | Yes | 0.8 | −5.1 to 6.8 | .79 | |

| Absolute | No | 4.3 | −5.9 to 14.4 | .41 | |

| Absolute | Yes | 2.9 | −7.7 to 13.4 | .59 | |

| Non-Bayesian | |||||

| Rate ratio | No | 1.06 | 0.79 to 1.43 | .68 |

The table includes 95 per cent credible interval and estimated probability that the groups differ ( P ). The results are shown for models that did and did not assume a delayed effect of funding. The citation results use a non-Bayesian confidence interval and P -value.

In a sensitivity analysis, we used the publication counts from Scopus only, and the rate ratio for funding was 1.13 (95 per cent CI 0.77–1.66), which is similar to the results using all three databases, but with a wider credible interval due to the reduced data.

The estimated delayed differences between researchers who were funded and not funded are given in Table 4 . There was a delayed effect of funding on citations, with an increasing gap between the funded and not funded groups by time since randomization. This difference is visualized in Fig. 3 . Five years after funding, the estimated absolute difference in annual citations is eighteen.

Estimated citations over time by funding status from a model with time-varying citations. Estimates for a researcher with the median number of prerandomization citations. The shaded areas are 80 per cent confidence intervals. Citations increase over time in both groups, but with a stronger increase in the funded group.

Estimated delayed mean percentage differences between funded and not funded researchers from the HRC of New Zealand trial.

| Outcome . | Estimate . | Mean . | 95% CI . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian | ||||

| Rate ratio | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.12 | .82 | |

| Absolute | −0.5 | −1.1 to 0.1 | .09 | |

| Absolute | 2.4 | −3.8 to 8.5 | .46 | |

| Non-Bayesian | ||||

| Rate ratio | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.04 | .0001 |

| Outcome . | Estimate . | Mean . | 95% CI . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian | ||||

| Rate ratio | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.12 | .82 | |

| Absolute | −0.5 | −1.1 to 0.1 | .09 | |

| Absolute | 2.4 | −3.8 to 8.5 | .46 | |

| Non-Bayesian | ||||

| Rate ratio | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.04 | .0001 |

The table includes 95 per cent credible interval for the difference, and estimated probability that the groups differ ( P ). The citation results use a non-Bayesian confidence interval and P -value. The estimates are a linear change in each year after funding.

A sensitivity analysis using just those researchers who consented gave similar results (see Supplementary material S.6 ).

Almost all researchers were still working in research in December 2021, with eighty-three (94 per cent) confirmed as still working in research. A survival analysis showed no difference in employment between the two groups; the hazard ratio for no longer working in research was 0.91 for funded researchers compared with nonfunded researchers, with a wide 95 per cent CI from 0.11 to 7.5.

The results of this first randomized trial of funding were equivocal. There was no clear benefit to winning funding on multiple outcomes, but the 95 per cent credible/confidence intervals for most estimates were wide and included differences that would have practical significance. Hence, there could still be a meaningful benefit that our study was unable to detect. There was a delayed benefit to funding on citations, but the average absolute benefit was relatively small at eighteen more citations after 5 years. The mostly inconclusive results of this study indicate that larger randomized experiments are required to reliably measure the productivity impacts of research funding.

The study was impacted by a significant rate of nonconsent, as around one-third of the applicants did not agree to participate, which means that no follow-up could be obtained. This reduction in participants reduces the statistical power and generalizability, as nonconsenters had generally fewer publications and fewer years of experience. Such losses could be avoided if the funding agency integrated the measurement of research productivity as part of a quality improvement process. There was a further loss of power due to 2 years having no randomization, as there was enough funding for all applicants who passed the peer-review stage. A year without randomization delays the accrual of data that could be used to show the effect of funding.

There was a further loss of power due to repeated applications from the same researchers. This is unavoidable given that researchers were allowed to repeatedly apply, but it made for a more complex design than wholly independent applications.

The trial has still been useful. It has demonstrated that randomized trials can be incorporated into funding systems and highlighted several design issues that should be taken into account in future research. A recent review of the evidence for funding systems advocated that funders should work together on comparative analysis ( Guthrie, Ghiga, and Wooding 2018 ). This could include collecting comparable outcomes and researcher characteristics across all schemes using modified lotteries. Combining experiments across funders can greatly increase the statistical power, providing answers that will inform policy with greater confidence. This expanded evidence base should help identify the elements and factors that increase research productivity and reduce waste. Combining data would be in line with the growing ‘big team science’ movement ( Forscher et al. 2023 ).

Randomized trials are superior to regression discontinuity designs. It is the difference between random and as-if random, or experimental and quasi-experimental. Randomization eliminates bias from known and unknown confounders and simplifies the study design. For research questions where randomization is impossible, the regression discontinuity design remains a useful option. But once randomization is feasible—as it now is with research funding—it becomes an inferior design.

While this study used the number of publications, citations, and Altmetric scores as the key outcomes, future experiments could capture a wider range of outcomes. For example, patent applications or spin-out companies, open science practices, and citation of research findings in clinical or health policy guidelines could be measurable outcomes for medical and science funding. It would also be possible to incorporate more subjective outcomes (e.g. level of innovation). Here, peer reviewers that are blinded to the allocation of funding could evaluate a researcher’s publications and nontraditional research outputs on a range of criteria, and these scores could then be used as outcomes.

5.1 Related research

We are not aware of any results from previous randomized experiments. A case–control analysis of funding at the Swiss National Science Foundation found one additional article in each of the 3 years following project funding, plus increased citations and Altmetric scores ( Heyard and Hottenrott 2021 ). An observational analysis of National Institutes of Health funding estimated 0.8 more publications for each additional $100,000 in funding ( Sattari et al. 2022 ). An observational analysis from New Zealand found that funding was associated with a 6–15 per cent increase in publications and an 11–22 per cent increase in citation-weighted papers ( Gush et al. 2017 ). A difference-in-difference analysis of professors at the University of Luxembourg found an increase in publications of 31 per cent associated with funding ( Hussinger and Carvalho 2021 ). A study of travel funding in Switzerland found that funding increased the number of new research collaborations but had no effect on publication counts ( Baruffaldi, Marino, and Visentin 2020 ). A study of the long-term effects of the European Research Council funding found a positive effect using a difference-in-difference design but no effect using regression discontinuity ( Ghirelli et al. 2023 ). None of these studies used a randomized design and hence are prone to selection bias.

The British Academy has recently employed a modified lottery in a scheme for early career researchers. While the level of funding (up to £10,000) is smaller than the Explorer Grant Scheme, several hundred applicants are being randomized each year providing much greater power to detect impacts. It is also subject to an evaluation via an integrated experiment ( Swain 2022 ).

5.2 Limitations

This is not a typical parallel group randomized trial where participants are randomized in a fixed ratio, usually 1:1. Instead, the randomization was used to separate equally meritorious applications, and so depended on the number and quality of applications each year.

Papers and citations are coarse outcomes of productivity and do not measure research quality. Future studies could use more insightful outcomes, such as estimates of the quality of the work from expert reviewers. However, this requires additional expert review with increased costs, and expert reviews will include noise.

The generalizability of the results is somewhat limited and may not be applicable outside New Zealand or to different amounts of funding. The funding amount of NZD $150,000 was potentially not large enough to greatly change researchers’ careers, although funding can be used to leverage promotions ( Rice et al. 2020 ).

In this novel small randomized trial, research funding did not have a clear impact on researcher productivity. However, the expanded use of modified lotteries in the allocation of grant funding has the potential to revolutionize the measurement of research productivity. If widely used by research funding agencies, it will be possible to routinely measure the impact of funding across a wide range of schemes and for different outcomes. This will provide a substantive evidence base to inform policies to reduce the level of waste in research, which occurs when the allocated funding does not produce any impact on research outputs or outcomes ( Ross et al. 2012 ).

We thank Altmetric for allowing the use of their data ( www.altmetric.com ).

Supplementary data is available at SCIPOL Journal online.

Authors M.L. and L.G. are employees of the HRC of New Zealand, which manages the Explorer Grant scheme.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1117784 to A.B.) and NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (to P.C.).

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly as the applicants were consented on the understanding that their data would not be shared with other researchers.

Aksnes D. W. , Langfeldt L. , and Wouters P. ( 2019 ) ‘ Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic Concepts and Theories ’, SAGE Open , 9 : 215824401982957.

Google Scholar

Avin S. ( 2019 ) ‘ Mavericks and Lotteries ’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A , 76 : 13 – 23 .

Baicker K. , and Finkelstein A. ( 2011 ) ‘ The Effects of Medicaid Coverage — Learning from the Oregon Experiment ’, New England Journal of Medicine , 365 : 683 – 5 .

Barnett A. et al. . ( 2022 ) ‘ What Is the Impact of Research Funding on Research Productivity? Protocol ’, https://osf.io/kmzjn , accessed 10 May 2025.

Baruffaldi S. H. , Marino M. , and Visentin F. ( 2020 ) ‘ Money to Move: The Effect on Researchers of an International Mobility Grant ’, Research Policy , 49 : 104077.

Benavente J. M. et al. ( 2012 ) ‘ The Impact of National Research Funds: A Regression Discontinuity Approach to the Chilean FONDECYT ’, Research Policy , 41 : 1461 – 75 .

Binde P. ( 2014 ) ‘ Games of Life and Death: The Judicial Uses of Dice in Eighteenth and Nineteenth-century Sweden ’, UNLV Gaming Research and Review Journal , 18 : 1.

Cuesta B. D. L. , and Imai K. ( 2016 ) ‘ Misunderstandings about the Regression Discontinuity Design in the Study of Close Elections ’, Annual Review of Political Science , 19 : 375 – 96 .

Editorial . ( 2017 ) ‘ Neutral Citation Is Poor Scholarship ’, Nature Genetics , 49 : 1559.

Editorial . ( 2022 ) ‘ The Case for Lotteries as a Tiebreaker of Quality in Research Funding ’, Nature , 609 : 653.

Elmore S. A. ( 2018 ) ‘ The Altmetric Attention Score: What Does It Mean and Why Should I Care? ’, Toxicologic Pathology , 46 : 252 – 5 .

Fang F. C. , Bowen A. , and Casadevall A. ( 2016 ) ‘ NIH Peer Review Percentile Scores are Poorly Predictive of Grant Productivity ’, eLife , 5 : e13323.

Fang F. C. , and Casadevall A. ( 2016 ) ‘ Grant Funding: Playing the Odds ’, Science , 352 : 158.

Forscher P. S. et al. ( 2023 ) ‘ The Benefits, Barriers, and Risks of Big-Team Science ’, Perspectives on Psychological Science , 18 : 607 – 23 .

Franceschet M. ( 2009 ) ‘ A Cluster Analysis of Scholar and Journal Bibliometric Indicators ’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology , 60 : 1950 – 64 .

Franke J. , and Leininger W. ( 2014 ) ‘ On the Efficient Provision of Public Goods by Means of Biased Lotteries: The Two Player Case ’, Economics Letters , 125 : 436 – 9 .

Frey B. S. , Osterloh M. , and Rost K. ( 2023 ) ‘ The Rationality of Qualified Lotteries ’, European Management Review , 20 : 698 – 710 .

Gallo S. A. , Sullivan J. H. , and Glisson S. R. ( 2016 ) ‘ The Influence of Peer Reviewer Expertise on the Evaluation of Research Funding Applications ’, PLoS ONE , 11 : 1 – 18 .

Gelman A. et al. ( 2013 ) Bayesian Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC Texts in Statistical Science . Boca Raton : CRC .

Google Preview

Gelman A. , and Loken E. ( 2013 ) ‘ The Garden of Forking Paths: Why Multiple Comparisons Can Be a Problem, Even When There Is No Fishing Expedition ’, https://tinyurl.com/mr23jx5w , accessed 10 May 2025.

Ghirelli C. et al. ( 2023 ) ‘ IZA DP No. 16108: The Long-Term Causal Effects of Winning an ERC Grant ’, IZA Discussion Paper . https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/16108/the-long-term-causal-effects-of-winning-an-erc-grant , accessed 10 May 2025.

Gush J. et al. ( 2017 ) ‘ The Effect of Public Funding on Research Output: The New Zealand Marsden Fund ’, New Zealand Economic Papers , 52 : 227 – 48 .

Guthrie S. , Ghiga I. , and Wooding S. ( 2018 ) ‘ What Do We Know about Grant Peer Review in the Health Sciences? ’, F1000Research , 6 : 1335.

Herbert D. L. et al. ( 2013 ) ‘ On the Time Spent Preparing Grant Proposals: An Observational Study of Australian Researchers ’, BMJ Open , 3 : e002800.

Heyard R. , and Hottenrott H. ( 2021 ) ‘ The Value of Research Funding for Knowledge Creation and Dissemination: A Study of SNSF Research Grants ’, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications , 8 : 1 – 16 .

Hultgren A. E. , Patras N. M. F. , and Hicks J. ( 2024 ) ‘ Meta-Research: Blinding Reduces Institutional Prestige Bias during Initial Review of Applications for a Young Investigator Award ’, eLife , 13 : e92339.

Huntsman E. D. ( 1996 ) ‘ And They Cast Lots: Divination, Democracy, and Josephus ’, Brigham Young University Studies , 36 : 365 – 77 .

Hussinger K. , and Carvalho J. N. ( 2021 ) ‘ The Long-term Effect of Research Grants on the Scientific Output of University Professors ’, Industry and Innovation , 29 : 463 – 87 .

Jacob B. A. , and Lefgren L. ( 2011 ) ‘ The Impact of NIH Postdoctoral Training Grants on Scientific Productivity ’, Research Policy , 40 : 864 – 74 .

Jaffe A. B. ( 2002 ) ‘ Building Programme Evaluation into the Design of Public Research-support Programmes ’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy , 18 : 22 – 34 .

Jones B. F. , and Summers L. H. ( 2020 ) ‘ A Calculation of the Social Returns to Innovation ’, Working Paper 27863 . National Bureau of Economic Research . http://www.nber.org/papers/w27863 , accessed 10 May 2024.

Lepage B. et al. ( 2015 ) ‘ Estimating the Causal Effect of an Exposure on Change from Baseline Using Directed Acyclic Graphs and Path Analysis ’, Epidemiology , 26 : 122 – 9 .

Li S. ( 2018 ) ‘ Better Lucky than Rich? Welfare Analysis of Automobile Licence Allocations in Beijing and Shanghai ’, The Review of Economic Studies , 85 : 2389 – 428 .

Liu M. et al. ( 2020 ) ‘ The Acceptability of Using a Lottery to Allocate Research Funding: A Survey of Applicants ’, Research Integrity and Peer Review , 5 : 1 – 7 .

Murphy K. M. , and Topel R. H. ( 2010 ) Measuring the Gains from Medical Research: An Economic Approach . Chicago : UCP .

Narahari A. K. et al. ( 2018 ) ‘ Surgeon Scientists are Disproportionately Affected by Declining NIH Funding Rates ’, Journal of the American College of Surgeons , 226 : 474 – 81 .

Osmond D. H. ( 1983 ) ‘ Malice’s Wonderland: Research Funding and Peer Review ’, Journal of Neurobiology , 14 : 95 – 112 .

Pavlovic V. et al. ( 2021 ) ‘ How Accurate are Citations of Frequently Cited Papers in Biomedical Literature? ’, Clinical Science , 135 : 671 – 81 .

R Core Team . ( 2023 ) ‘ R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing ’, Vienna . https://www.R-project.org/ , accessed 10 May 2025.

Rice D. B. et al. ( 2020 ) ‘ Academic Criteria for Promotion and Tenure in Biomedical Sciences Faculties: Cross Sectional Analysis of International Sample of Universities ’, BMJ , 369 : m2081.

Ross J. S. et al. ( 2012 ) ‘ Publication of NIH Funded Trials Registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: Cross Sectional Analysis ’, BMJ , 344 .

Sattari R. et al. ( 2022 ) ‘ The Ripple Effects of Funding on Researchers and Output ’, Science Advances , 8 : eabb7348.

Shaw J. ( 2022 ) ‘ Peer Review in Funding-by-lottery: A Systematic Overview and Expansion ’, Research Evaluation , 32 : 86 – 100 .

Sher G. ( 1980 ) ‘ What Makes a Lottery Fair? ’, Nous , 14 : 203.

Sommer E. W. ( 1998 ) ‘ Gambling with God: The Use of the Lot by the Moravian Brethren in the Eighteenth Century ’, Journal of the History of Ideas , 59 : 267 – 86 .

Swain S. ( 2022 ) ‘ The British Academy is Trialling a New, Fairer Method of Selecting Its Small Research Grants - Here’s Why ’, https://tinyurl.com/yc8ff5ht , accessed 18 Sep. 2023 .

Taylor C. ( 2007 ) ‘ From the Whole Citizen Body? The Sociology of Election and Lot in the Athenian Democracy ’, Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens , 76 : 323 – 45 .

Thistlethwaite D. L. , and Campbell D. T. ( 1960 ) ‘ Regression-discontinuity Analysis: An Alternative to the Ex Post Facto Experiment ’, Journal of Educational Psychology , 51 : 309 – 17 .

Viergever R. F. , and Hendriks T. C. C. ( 2016 ) ‘ The 10 Largest Public and Philanthropic Funders of Health Research in the World: What They Fund and How They Distribute Their Funds ’, Health Research Policy and Systems , 14 : 1 – 15 .

Witteman H. O. et al. ( 2019 ) ‘ Are Gender Gaps Due to Evaluations of the Applicant or the Science? A Natural Experiment at A National Funding Agency ’, The Lancet , 393 : 531 – 40 .

Wren J. D. , and Georgescu C. ( 2020 ) ‘ Detecting Potential Reference List Manipulation within a Citation Network ’, bioRxiv .

Yang W. , Jones B. F. , and Wang D. ( 2019 ) ‘ Early-career Setback and Future Career Impact ’, Nature Communications , 10 : 4331.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| August 2024 | 117 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-5430

- Print ISSN 0302-3427

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Applying for funding

How to apply for research funding: the process at oxford, funder guidance and application systems, applying for ethical review.

- Where and how to apply for ethical review

NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre

Enabling translational research through partnership

UK’s most ambitious melanoma research study created for patients, by patients

6 August 2024 · Listed under Cancer

“Any melanoma patient can be part of it. You don’t have to go into a hospital, you don’t have to live near a university that’s active in research, all you need is access to the internet.” Kelly Norman, patient representative

MyMelanoma is an online-based research project for melanoma patients. The study aims to recruit 20,000 UK patients to provide information on their lifestyle, health and treatment outcomes in order to build a unique and innovative resource for research into the disease.

The project, which is led by the University of Oxford, was initiated by melanoma survivors who wanted to give back to research.

This group of patients approached a professor in Leeds with an idea of creating a new, accessible study that could involve anyone diagnosed with melanoma, without the need to go into hospital.

Early support from the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) helped kickstart the project by providing funding for staffing and IT infrastructure.

This data is expected to answer some of the questions that current melanoma studies cannot solve – and help the 50 people in the UK diagnosed with the disease each day.

Kelly Norman, a patient representative on the MyMelanoma study, said: “Not only does the study look at the science, but it looks at the people too, as in how we as melanoma patients are affected not just physiologically but psychologically.

“Any melanoma patient can be part of it. You don’t have to go into a hospital, you don’t have to live near a university that’s active in research. All you need is access to the internet.”