Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

Apply now and work for two to five years. We'll save you a seat in our MBA class when you're ready to come back to campus for your degree.

Executive Programs

The 20-month program teaches the science of management to mid-career leaders who want to move from success to significance.

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Credit: Pixabay

Social Media

MIT Sloan study finds thinking style impacts how people use social media

MIT Sloan Office of Communications

Feb 11, 2021

Critical thinkers share higher quality content and information than intuitive thinkers

CAMBRIDGE, Mass., Feb. 11, 2021 – Social media has become a significant channel for social interactions, political communications, and marketing. However, little is known about the effect of cognitive style on how people engage with social media. A new study by MIT Sloan Research Affiliate Mohsen Mosleh , MIT Sloan School of Management Prof. David Rand , and their collaborators shows that people who engage in more analytical thinking are more discerning in their social media use, sharing news content from more reliable sources and tweeting about more substantial topics like politics.

“It’s important to understand how people interact on social media and what influences their decisions to share content and follow different accounts. Prior studies have explored the relationship between social media use and personality and demographic measures, but this is the first study to show the connection with cognitive style,” says Rand.

Mosleh, a professor at the University of Exeter Business School, explains, “In the field of cognitive science, some argue that critical thinking doesn’t have much to do with our daily life, but this study shows that it matters – critical thinkers are better able to use social media in meaningful ways, which has become an important part of modern life.”

In their study, the researchers measure Twitter-users cognitive style using the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), which is a set of questions with intuitively compelling but incorrect answers. For example, participants might be asked” If you are running a race and you pass the person in second place, what place are you in? The answer that intuitively comes to mind for many people is “first place,” however “second place” is the correct answer.

Mosleh points out that there is disagreement in the field of cognitive science about the relative roles of intuition and reflection in people’s everyday lives. Some say humans’ capacity to reflect is underused, and that critical thinking is mostly used to justify our intuitive judgments. Others maintain that critical thinking does have a meaningful impact on beliefs and behaviors and that it increases accuracy.

Their Twitter study confirmed that critical thinking has a significant impact on how users interact on social media. People in the sample who engaged in more cognitive reflection were more discerning in their social media use. They followed more selectively, shared higher quality content from more reliable sources, and tweeted about weightier subjects, particularly politics.

The researchers also found evidence of cognitive “echo chambers,” says Rand. “More intuitive users tended to follow similar types of accounts, which were notably avoided by more analytical users. They also tended to share content related to scams and sales promotions.”

He notes, “This study sheds light on how misinformation and scams are spread on social media, suggesting that lack of thinking is an important contributor to undesirable behavior. It also highlights the type of users at risk of falling for scams.”

As for the importance of cognitive style for everyday behaviors, Rand call this an “important new piece of evidence for the consequences of analytic thinking.”

Rand and Mosleh are coauthors of “Cognitive reflection correlates with behavior on Twitter,” along with MIT Research Associate Antonio Arechar and University of Regina Assistant Professor Gordon Pennycook,which was published in Nature Communications.

About the MIT Sloan School of Management

The MIT Sloan School of Management is where smart, independent leaders come together to solve problems, create new organizations, and improve the world. Learn more at mitsloan.mit.edu .

Related Articles

Does social media affect critical thinking skills?

The emergence of social media and the reliance on various platforms is increasingly impacting the way in which we interact with each other and the world as a whole. We know that our virtual network is oftentimes as important to us as our physical network and that the information we digest online is significantly influential, but is social media affecting our critical thinking skills? The answer is, yes. Although, for better or worse is the question.

How is social media affecting critical thinking skills?

In a nutshell, critical thinking skills refer to our ability to analyze, interpret, infer, and problem-solve. These skills typically present themselves in the order of identifying a problem, gathering the data relevant to that problem, analyzing the information we gathered, and making a decision or coming to a solution.

In addition to the negative impacts of multi-tasking, social media tends to prey on emotion rather than reason. You can thank the algorithms behind your preferred platform for this, as these algorithms deliberately put information in front of you that is targeted to your interest and leanings in any easily digestible format. By seeing information that you already tend to agree with or favor more often than you see information that counters your beliefs, you are being denied the ability to gather all information, analyze appropriately, and come to a more well-informed conclusion.

Does social media affect the critical thinking skills of one group more than another?

The most susceptible to the cognitive and behavioral downfalls of social media use are youth and young adults because they are at an age when their emotional intelligence and critical thinking skills are still immature.

The young are particularly reliant on the positive feedback received through social media, which makes them less likely to be critical of information presented, as they do not want to appear like they are rocking the boat or going against their friends.

Although the younger population is more susceptible to conforming to popular opinions, a 2019 Science Advances study showed that older people, those 65 years old and older, are four times more likely to spread misinformation on social media. Thus, proving that a failure to employ critical thinking skills when using social media is not isolated to the younger population. It is a problem shared by many.

Is there an upside to social media when it comes to critical thinking skills?

In order to do this, one needs to be resistant to accepting the first piece of information as the truth before having a chance to validate that information.

What can I do to strengthen my critical thinking skills on social media?

In a time when information is king and social media is a big player in spreading that information, it is essential to remain vigilant to the information we are taking in. Questioning what is presented as fact and utilizing the amazing tool that is the web to develop well-informed opinions is the key to honing your critical thinking skills on social media.

You may also like

Best apps for problem solving: top picks for effective solutions, critical thinking brain teasers: enhance your cognitive skills today, why podcasts are killing critical thinking: assessing the impact on public discourse, divergent thinking vs brainstorming: how to use these techniques to get better ideas, download this free ebook.

- Center for Science, Technology, Ethics and Society (STES)

- social-media.pcf

Introduction to Critical Thinking About Social Media

What is critical thinking and why should we think critically about social media? The materials below are to help provide students with a foundation of critical thinking terms and concepts and some reasons why we might think that we should all have a dialogue about the potential benefits and harms of social media and how we might use it responsibly.

Topics:

Why should we think critically about social media.

- Lesson Plan One - Introduction to Critical Thinking about Social Media (accessible online version).

Downloadable version

What is critical thinking?

- Lesson Plan Two - What IS Critical Thinking? (accessible online version).

What does it mean to engage "socially" with each other?

- Lesson Plan Three - What does it mean to engage "socially"? (accessible online version).

How can we better understand "identity" and "community"?

Lesson Plan Four: Identity and Community

Center for Science, Technology, Ethics and Society Montana State University Wilson 2-152 Bozeman, MT 59717

[email protected]

Director: Kristen Intemann [email protected]

The impact of social media on critical thinking

by Open Minds Foundation | Uncategorized

Social media can be a wonderful thing, but it can also be a tool used to spread misinformation and disinformation by bad actors. With studies showing that around 80% of young people, aged 18 to 24, receive all of their news from social media , it is not surprising that research by YouGov indicates that people who use social media as a news source do not perform as well on the Misinformation Susceptibility Test (MIST) .

People who spend two hours or less of recreational time online each day are twice as likely to be in the highest-scoring category (30% vs. 15%) as people who spend 9 or more hours online per day.

Social media platforms such as X or Facebook, use algorithms to determine the content that is prioritised in your social media feeds. Unfortunately, disinformation and fake news are likely to be more sensational, outrageous, or attention-grabbing so get amplified, drowning out credible information and sources. People act based on the information they are exposed to, so when this information is false or misleading, disastrous results can ensue.

With news spreading quickly, it is difficult to separate fact from fiction in such an emotive and high-tension atmosphere. For example, there is a lot of noise on social media currently around the conflict happening between Israel and Hamas, with Elon Musk sharing accounts described as “ well-known spreaders of disinformation .”

But with social media being an everyday part of many people’s lives, how can you think critically and use it more effectively?

Use the SIFT method:

S: Stop to check for accuracy before you hit share. I: Investigate the source. Is it a reputable news outlet or account? F: Find better coverage. Are multiple outlets sharing the same story, where did this story originate from? T: Trace claims, quotes, and media to their original source

Try inverting the problem

It is also a good idea to deliberately diversify your sources or try the inversion technique .

Inversion thinking encourages us to deliberately approach information in a contrary way. By envisioning an alternative scenario, or ‘playing devil’s advocate’, to actively challenge our biases and finding alternative sources, it makes our reasoning much stronger. It helps us to determine fact from fiction and recognise how our own biases can stand in the way of us thinking critically.

How you can help us combat coercive control

- Stop Mandated Shunning: announcement

- Developing critical thinking in primary schools, with the Open Minds Foundation

- Developing critical thinking through play

- How individuals can avoid sharing mis- and disinformation

- The Martyr Complex and Conspiracy Theorists

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Use of Critical Thinking to Identify Fake News: A Systematic Literature Review

Paul machete.

Department of Informatics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa

Marita Turpin

With the large amount of news currently being published online, the ability to evaluate the credibility of online news has become essential. While there are many studies involving fake news and tools on how to detect it, there is a limited amount of work that focuses on the use of information literacy to assist people to critically access online information and news. Critical thinking, as a form of information literacy, provides a means to critically engage with online content, for example by looking for evidence to support claims and by evaluating the plausibility of arguments. The purpose of this study is to investigate the current state of knowledge on the use of critical thinking to identify fake news. A systematic literature review (SLR) has been performed to identify previous studies on evaluating the credibility of news, and in particular to see what has been done in terms of the use of critical thinking to evaluate online news. During the SLR’s sifting process, 22 relevant studies were identified. Although some of these studies referred to information literacy, only three explicitly dealt with critical thinking as a means to identify fake news. The studies on critical thinking noted critical thinking as an essential skill for identifying fake news. The recommendation of these studies was that information literacy be included in academic institutions, specifically to encourage critical thinking.

Introduction

The information age has brought a significant increase in available sources of information; this is in line with the unparalleled increase in internet availability and connection, in addition to the accessibility of technological devices [ 1 ]. People no longer rely on television and print media alone for obtaining news, but increasingly make use of social media and news apps. The variety of information sources that we have today has contributed to the spread of alternative facts [ 1 ]. With over 1.8 billion active users per month in 2016 [ 2 ], Facebook accounted for 20% of total traffic to reliable websites and up to 50% of all the traffic to fake news sites [ 3 ]. Twitter comes second to Facebook, with over 400 million active users per month [ 2 ]. Posts on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter spread rapidly due to how they attempt to grab the readers’ attention as quickly as possible, with little substantive information provided, and thus create a breeding ground for the dissemination of fake news [ 4 ].

While social media is a convenient way of accessing news and staying connected to friends and family, it is not easy to distinguish real news from fake news on social media [ 5 ]. Social media continues to contribute to the increasing distribution of user-generated information; this includes hoaxes, false claims, fabricated news and conspiracy theories, with primary sources being social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter [ 6 ]. This means that any person who is in possession of a device, which can connect to the internet, is potentially a consumer or distributor of fake news. While social media platforms and search engines do not encourage people to believe the information being circulated, they are complicit in people’s propensity to believe the information they come across on these platforms, without determining their validity [ 6 ]. The spread of fake news can cause a multitude of damages to the subject; varying from reputational damage of an individual, to having an effect on the perceived value of a company [ 7 ].

The purpose of this study is to investigate the use of critical thinking methods to detect news stories that are untrue or otherwise help to develop a critical attitude to online news. This work was performed by means of a systematic literature review (SLR). The paper is presented as follows. The next section provides background information on fake news, its importance in the day-to-day lives of social media users and how information literacy and critical thinking can be used to identify fake news. Thereafter, the SLR research approach is discussed. Following this, the findings of the review are reported, first in terms of descriptive statistics and the in terms of a thematic analysis of the identified studies. The paper ends with the Conclusion and recommendations.

Background: Fake News, Information Literacy and Critical Thinking

This section discusses the history of fake news, the fake news that we know today and the role of information literacy can be used to help with the identification of fake news. It also provides a brief definition of critical thinking.

The History of Fake News

Although fake news has received increased attention recently, the term has been used by scholars for many years [ 4 ]. Fake news emerged from the tradition of yellow journalism of the 1890s, which can be described as a reliance on the familiar aspects of sensationalism—crime news, scandal and gossip, divorces and sex, and stress upon the reporting of disasters, sports sensationalism as well as possibly satirical news [ 5 ]. The emergence of online news in the early 2000s raised concerns, among them being that people who share similar ideologies may form “echo chambers” where they can filter out alternative ideas [ 2 ]. This emergence came about as news media transformed from one that was dominated by newspapers printed by authentic and trusted journalists to one where online news from an untrusted source is believed by many [ 5 ]. The term later grew to describe “satirical news shows”, “parody news shows” or “fake-news comedy shows” where a television show, or segment on a television show was dedicated to political satire [ 4 ]. Some of these include popular television shows such as The Daily Show (now with Trevor Noah), Saturday Night Live ’s “The Weekend Update” segment, and other similar shows such as Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and The Colbert Report with Stephen Colbert [ 4 ]. News stories in these shows were labelled “fake” not because of their content, but for parodying network news for the use of sarcasm, and using comedy as a tool to engage real public issues [ 4 ]. The term “Fake News” further became prominent during the course of the 2016 US presidential elections, as members of the opposing parties would post incorrect news headlines in order to sway the decision of voters [ 6 ].

Fake News Today

The term fake news has a more literal meaning today [ 4 ]. The Macquarie Dictionary named fake news the word of the year for 2016 [ 8 ]. In this dictionary, fake news is described it as a word that captures a fascinating evolution in the creation of deceiving content, also allowing people to believe what they see fit. There are many definitions for the phrase, however, a concise description of the term can be found in Paskin [ 4 ] who states that certain news articles originating from either social media or mainstream (online or offline) platforms, that are not factual, but are presented as such and are not satirical, are considered fake news. In some instances, editorials, reports, and exposés may be knowingly disseminating information with intent to deceive for the purposes of monetary or political benefit [ 4 ].

A distinction amongst three types of fake news can be made on a conceptual level, namely: serious fabrications, hoaxes and satire [ 3 ]. Serious fabrications are explained as news items written on false information, including celebrity gossip. Hoaxes refer to false information provided via social media, aiming to be syndicated by traditional news platforms. Lastly, satire refers to the use of humour in the news to imitate real news, but through irony and absurdity. Some examples of famous satirical news platforms in circulation in the modern day are The Onion and The Beaverton , when contrasted with real news publishers such as The New York Times [ 3 ].

Although there are many studies involving fake news and tools on how to detect it, there is a limited amount of academic work that focuses on the need to encourage information literacy so that people are able to critically access the information they have been presented, in order to make better informed decisions [ 9 ].

Stein-Smith [ 5 ] urges that information/media literacy has become a more critical skill since the appearance of the notion of fake news has become public conversation. Information literacy is no longer a nice-to-have proficiency but a requirement for interpreting news headlines and participation in public discussions. It is essential for academic institutions of higher learning to present information literacy courses that will empower students and staff members with the prerequisite tools to identify, select, understand and use trustworthy information [ 1 ]. Outside of its academic uses, information literacy is also a lifelong skill with multiple applications in everyday life [ 5 ]. The choices people make in their lives, and opinions they form need to be informed by the appropriate interpretation of correct, opportune, and significant information [ 5 ].

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking covers a broad range of skills that includes the following: verbal reasoning skills; argument analysis; thinking as hypothesis testing; dealing with likelihood and uncertainties; and decision making and problem solving skills [ 10 ]. For the purpose of this study, where we are concerned with the evaluation of the credibility of online news, the following definition will be used: critical thinking is “the ability to analyse and evaluate arguments according to their soundness and credibility, respond to arguments and reach conclusions through deduction from given information” [ 11 ]. In this study, we want to investigate how the skills mentioned by [ 11 ] can be used as part of information literacy, to better identify fake news.

The next section presents the research approach that was followed to perform the SLR.

Research Method

This section addresses the research question, the search terms that were applied to a database in relation to the research question, as well as the search criteria used on the search results. The following research question was addressed in this SLR:

- What is the role of critical thinking in identifying fake news, according to previous studies?

The research question was identified in accordance to the research topic. The intention of the research question is to determine if the identified studies in this review provide insights into the use of critical thinking to evaluate the credibility of online news and in particular to identify fake news.

Delimitations.

In the construction of this SLR, the following definitions of fake news and other related terms have been excluded, following the suggestion of [ 2 ]:

- Unintentional reporting mistakes;

- Rumours that do not originate from a particular news article;

- Conspiracy theories;

- Satire that is unlikely to be misconstrued as factual;

- False statements by politicians; and

- Reports that are slanted or misleading, but not outright false.

Search Terms.

The database tool used to extract sources to conduct the SLR was Google Scholar ( https://scholar.google.com ). The process for extracting the sources involved executing the search string on Google Scholar and the retrieval of the articles and their meta-data into a tool called Mendeley, which was used for reference management.

The search string used to retrieve the sources was defined below:

(“critical think*” OR “critically (NEAR/2) reason*” OR “critical (NEAR/2) thought*” OR “critical (NEAR/2) judge*” AND “fake news” AND (identify* OR analyse* OR find* OR describe* OR review).

To construct the search criteria, the following factors have been taken into consideration: the research topic guided the search string, as the key words were used to create the base search criteria. The second step was to construct the search string according to the search engine requirements on Google Scholar.

Selection Criteria.

The selection criteria outlined the rules applied in the SLR to identify sources, narrow down the search criteria and focus the study on a specific topic. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1 to show which filters were applied to remove irrelevant sources.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for paper selection

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Publications related to alternative facts, fake news and fabrications | Publications related to alternative facts, fake news and fabrications |

| Academic journals published in information technology and related fields | Academic journals published in information technology and related fields |

| Academic journals should outline critical thinking, techniques of how to identify fake news or reviewing fake news using critical thinking | Academic journals should outline critical thinking, techniques of how to identify fake news or reviewing fake news using critical thinking |

| Academic journals should include an abstract | Academic journals should include an abstract |

| Publications related to alternative facts, fake news and fabrications |

Source Selection.

The search criteria were applied on the online database and 91 papers were retrieved. The criteria in Table 1 were used on the search results in order to narrow down the results to appropriate papers only.

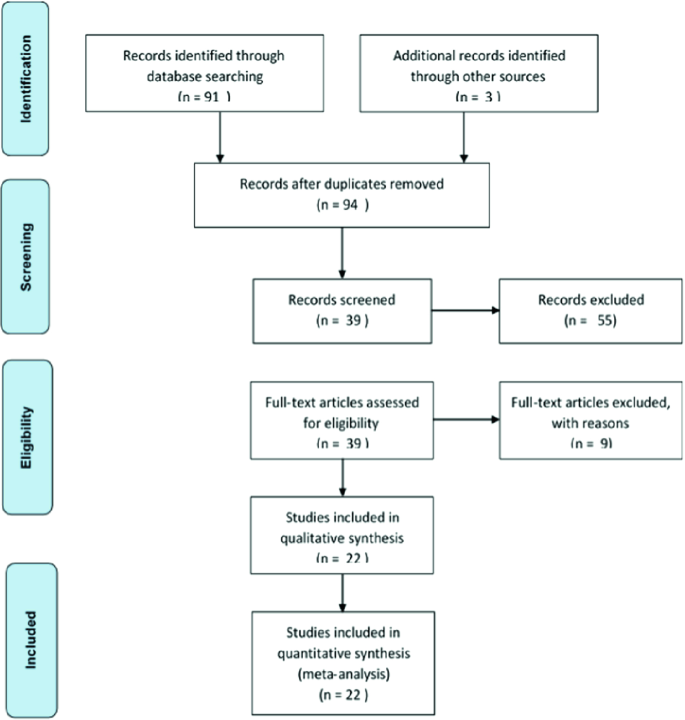

PRISMA Flowchart.

The selection criteria included four stages of filtering and this is depicted in Fig. 1 . In then Identification stage, the 91 search results from Google Scholar were returned and 3 sources were derived from the sources already identified from the search results, making a total of 94 available sources. In the screening stage, no duplicates were identified. After a thorough screening of the search results, which included looking at the availability of the article (free to use), 39 in total records were available – to which 55 articles were excluded. Of the 39 articles, nine were excluded based on their titles and abstract being irrelevant to the topic in the eligibility stage. A final list of 22 articles was included as part of this SLR. As preparation for the data analysis, a data extraction table was made that classified each article according to the following: article author; article title; theme (a short summary of the article); year; country; and type of publication. The data extraction table assisted in the analysis of findings as presented in the next section.

PRISMA flowchart

Analysis of Findings

Descriptive statistics.

Due to the limited number of relevant studies, the information search did not have a specified start date. Articles were included up to 31 August 2019. The majority of the papers found were published in 2017 (8 papers) and 2018 (9 papers). This is in line with the term “fake news” being announced the word of the year in the 2016 [ 8 ].

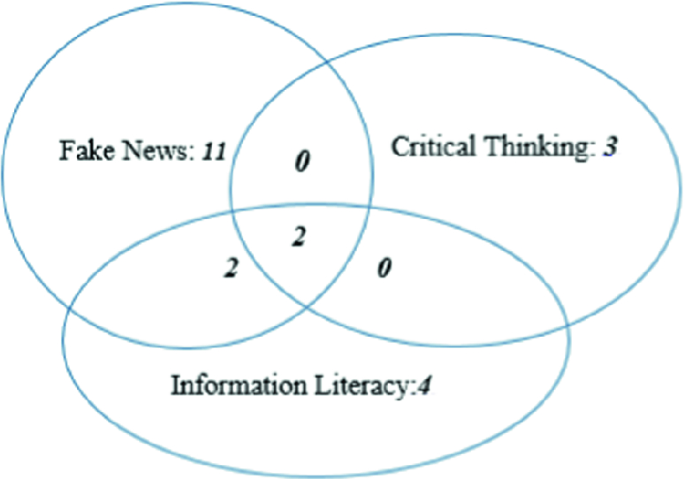

The selected papers were classified into themes. Figure 2 is a Venn diagram that represents the overlap of articles by themes across the review. Articles that fall under the “fake news” theme had the highest number of occurrences, with 11 in total. Three articles focused mainly on “Critical Thinking”, and “Information Literacy” was the main focus of four articles. Two articles combined all three topics of critical thinking, information literacy, and fake news.

Venn diagram depicting the overlap of articles by main focus

An analysis of the number of articles published per country indicate that the US had a dominating amount of articles published on this topic, a total of 17 articles - this represents 74% of the selected articles in this review. The remaining countries where articles were published are Australia, Germany, Ireland, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Sweden - with each having one article published.

In terms of publication type, 15 of the articles were journal articles, four were reports, one was a thesis, one was a magazine article and one, a web page.

Discussion of Themes

The following emerged from a thematic analysis of the articles.

Fake News and Accountability.

With the influence that social media has on the drive of fake news [ 2 ], who then becomes responsible for the dissemination and intake of fake news by the general population? The immediate assumption is that in the digital age, social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter should be able to curate information, or do some form of fact-checking when posts are uploaded onto their platforms [ 12 ], but that leans closely to infringing on freedom of speech. While different authors agree that there need to be measures in place for the minimisation of fake news being spread [ 12 , 13 ], where that accountability lies differs between the authors. Metaxas and Mustafaraj [ 13 ] aimed to develop algorithms or plug-ins that can assist in trust and postulated that consumers should be able to identify misinformation, thus making an informed decision on whether to share that information or not. Lazer et al. [ 12 ] on the other hand, believe the onus should be on the platform owners to put restrictions on the kind of data distributed. Considering that the work by Metaxas and Mustafaraj [ 13 ] was done seven years ago, one can conclude that the use of fact-checking algorithms/plug-ins has not been successful in curbing the propulsion of fake news.

Fake News and Student Research.

There were a total of four articles that had a focus on student research in relation to fake news. Harris, Paskin and Stein-Smith [ 4 , 5 , 14 ] all agree that students do not have the ability to discern between real and fake news. A Stanford History Education Group study reveals that students are not geared up for distinguishing real from fake news [ 4 ]. Most students are able to perform a simple Google search for information; however, they are unable to identify the author of an online source, or if the information is misleading [ 14 ]. Furthermore, students are not aware of the benefits of learning information literacy in school in equipping them with the skills required to accurately identify fake news [ 5 ]. At the Metropolitan Campus of Fairleigh Dickson University, librarians have undertaken the role of providing training on information literacy skills for identifying fake news [ 5 ].

Fake News and Social Media.

A number of authors [ 6 , 15 ] are in agreement that social media, the leading source of news, is the biggest driving force for fake news. It provides substantial advantage to broadcast manipulated information. It is an open platform of unfiltered editors and open to contributions from all. According to Nielsen and Graves as well as Janetzko, [ 6 , 15 ], people are unable to identify fake news correctly. They are likely to associate fake news with low quality journalism than false information designed to mislead. Two articles, [ 15 ] and [ 6 ] discussed the role of critical thinking when interacting on social media. Social media presents information to us that has been filtered according to what we already consume, thereby making it a challenge for consumers to think critically. The study by Nielsen and Graves [ 6 ] confirm that students’ failure to verify incorrect online sources requires urgent attention as this could indicate that students are a simple target for presenting manipulated information.

Fake News That Drive Politics.

Two studies mention the effect of social and the spread of fake news, and how it may have propelled Donald Trump to win the US election in 2016 [ 2 , 16 ]. Also, [ 8 ] and [ 2 ] mention how a story on the Pope supporting Trump in his presidential campaign, was widely shared (more than a million times) on Facebook in 2016. These articles also point out how in the information age, fact-checking has become relatively easy, but people are more likely to trust their intuition on news stories they consume, rather than checking the reliability of a story. The use of paid trolls and Russian bots to populate social media feeds with misinformation in an effort to swing the US presidential election in Donald Trump’s favour, is highlighted [ 16 ]. The creation of fake news, with the use of alarmist headlines (“click bait”), generates huge traffic into the original websites, which drives up advertising revenue [ 2 ]. This means content creators are compelled to create fake news, to drive ad revenue on their websites - even though they may not be believe in the fake news themselves [ 2 ].

Information Literacy.

Information literacy is when a person has access to information, and thus can process the parts they need, and create ways in which to best use the information [ 1 ]. Teaching students the importance of information literacy skills is key, not only for identifying fake news but also for navigating life aspects that require managing and scrutinising information, as discussed by [ 1 , 17 ], and [ 9 ]. Courtney [ 17 ] highlights how journalism students, above students from other disciplines, may need to have some form of information literacy incorporated into their syllabi to increase their awareness of fake news stories, creating a narrative of being objective and reliable news creators. Courtney assessed different universities that teach journalism and media-related studies, and established that students generally lack awareness on how useful library services are in offering services related to information literacy. Courtney [ 17 ] and Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] discuss how the use of library resources should be normalised to students. With millennials and generation Z having social media as their first point of contact, Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] urges universities, colleges and other academic research institutes to promote the use of more library resources than those from the internet, to encourage students to lean on reliable sources. Overall, this may prove difficult, therefore Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] proposes that by teaching information literacy skills and critical thinking, students can use these skills to apply in any situation or information source.

Referred to as “truth decay”, people have reached a point where they no longer need to agree with facts [ 18 ]. Due to political polarisation, the general public hold the opinion of being part of an oppressed group of people, and therefore will believe a political leader who appeals to that narrative [ 18 ]. There needs to be tangible action put into driving civil engagement, to encourage people to think critically, analyse information and not believe everything they read.

Critical Thinking.

Only three of the articles had critical thinking as a main theme. Bronstein et al. [ 19 ] discuss how certain dogmatic and religious beliefs create a tendency in individuals to belief any information given, without them having a need to interrogate the information further and then deciding ion its veracity. The article further elaborates how these individuals are also more likely to engage in conspiracy theories, and tend to rationalise absurd events. Bronstein et al.’s [ 19 ] study conclude that dogmatism and religious fundamentalism highly correlate with a belief in fake news. Their study [ 19 ] suggests the use of interventions that aim to increase open-minded thinking, and also increase analytical thinking as a way to help religious, curb belief in fake news. Howlett [ 20 ] describes critical thinking as evidence-based practice, which is taking the theories of the skills and concepts of critical thinking and converting those for use in everyday applications. Jackson [ 21 ] explains how the internet purposely prides itself in being a platform for “unreviewed content”, due to the idea that people may not see said content again, therefore it needs to be attention-grabbing for this moment, and not necessarily accurate. Jackson [ 21 ] expands that social media affected critical thinking in how it changed the view on published information, what is now seen as old forms of information media. This then presents a challenge to critical thinking in that a large portion of information found on the internet is not only unreliable, it may also be false. Jackson [ 21 ] posits that one of the biggest dangers to critical thinking may be that people have a sense of perceived power for being able to find the others they seek with a simple web search. People are no longer interested in evaluation the credibility of the information they receive and share, and thus leading to the propagation of fake news [ 21 ].

Discussion of Findings

The aggregated data in this review has provided insight into how fake news is perceived, the level of attention it is receiving and the shortcomings of people when identifying fake news. Since the increase in awareness of fake news in 2016, there has been an increase in academic focus on the subject, with most of the articles published between 2017 and 2018. Fifty percent of the articles released focused on the subject of fake news, with 18% reflecting on information literacy, and only 13% on critical thinking.

The thematic discussion grouped and synthesised the articles in this review according to the main themes of fake news, information literacy and critical thinking. The Fake news and accountability discussion raised the question of who becomes accountable for the spreading of fake news between social media and the user. The articles presented a conclusion that fact-checking algorithms are not successful in reducing the dissemination of fake news. The discussion also included a focus on fake news and student research , whereby a Stanford History Education Group study revealed that students are not well educated in thinking critically and identifying real from fake news [ 4 ]. The Fake news and social media discussion provided insight on social media is the leading source of news as well as a contributor to fake news. It provides a challenge for consumers who are not able to think critically about online news, or have basic information literacy skills that can aid in identifying fake news. Fake news that drive politics highlighted fake news’ role in politics, particularly the 2016 US presidential elections and the influence it had on the voters [ 22 ].

Information literacy related publications highlighted the need for educating the public on being able to identify fake news, as well as the benefits of having information literacy as a life skill [ 1 , 9 , 17 ]. It was shown that students are often misinformed about the potential benefits of library services. The authors suggested that university libraries should become more recognised and involved as role-players in providing and assisting with information literacy skills.

The articles that focused on critical thinking pointed out two areas where a lack of critical thinking prevented readers from discerning between accurate and false information. In the one case, it was shown that people’s confidence in their ability to find information online gave made them overly confident about the accuracy of that information [ 21 ]. In the other case, it was shown that dogmatism and religious fundamentalism, which led people to believe certain fake news, were associated with a lack of critical thinking and a questioning mind-set [ 21 ].

The articles that focused on information literacy and critical thinking were in agreement on the value of promoting and teaching these skills, in particular to the university students who were often the subjects of the studies performed.

This review identified 22 articles that were synthesised and used as evidence to determine the role of critical thinking in identifying fake news. The articles were classified according to year of publication, country of publication, type of publication and theme. Based on the descriptive statistics, fake news has been a growing trend in recent years, predominantly in the US since the presidential election in 2016. The research presented in most of the articles was aimed at the assessment of students’ ability to identify fake news. The various studies were consistent in their findings of research subjects’ lack of ability to distinguish between true and fake news.

Information literacy emerged as a new theme from the studies, with Rose-Wiles [ 9 ] advising academic institutions to teach information literacy and encourage students to think critically when accessing online news. The potential role of university libraries to assist in not only teaching information literacy, but also assisting student to evaluate the credibility of online information, was highlighted. The three articles that explicitly dealt with critical thinking, all found critical thinking to be lacking among their research subjects. They further indicated how this lack of critical thinking could be linked to people’s inability to identify fake news.

This review has pointed out people’s general inability to identify fake news. It highlighted the importance of information literacy as well as critical thinking, as essential skills to evaluate the credibility of online information.

The limitations in this review include the use of students as the main participants in most of the research - this would indicate a need to shift the academic focus towards having the general public as participants. This is imperative because anyone who possesses a mobile device is potentially a contributor or distributor of fake news.

For future research, it is suggested that the value of the formal teaching of information literacy at universities be further investigated, as a means to assist students in assessing the credibility of online news. Given the very limited number of studies on the role of critical thinking to identify fake news, this is also an important area for further research.

Contributor Information

Marié Hattingh, Email: [email protected] .

Machdel Matthee, Email: [email protected] .

Hanlie Smuts, Email: [email protected] .

Ilias Pappas, Email: [email protected] .

Yogesh K. Dwivedi, Email: moc.liamg@ideviwdky .

Matti Mäntymäki, Email: [email protected] .

How Can Social Media be Used for Critical Thinking Practice?

In today’s digitally saturated world, social media reigns supreme. Students navigate a constant stream of information, opinions, and imagery. While this constant connection offers a wealth of knowledge and fosters social interaction, it also presents a challenge: developing critical thinking skills in a landscape rife with misinformation and echo chambers.

By leveraging its interactive nature and fostering a culture of questioning, educators can transform these social media into powerful tools for critical thinking development.

1. Deconstructing the Stream: Source Verification and Bias Awareness

The firehose of information on social media can be overwhelming. Students need to be equipped to identify reliable sources. Educators can create activities that involve:

- Dissecting Posts: Start by examining a social media post together. Ask students to identify the source, the type of content (image, video, text), and the intended audience. Discuss the purpose of the post – is it informative, persuasive, or entertaining?

- Following the Trail: Encourage students to track the source of information. Is it a recognized news outlet? Can they find the original creator of an image or video? This teaches them to source checks and avoid blindly accepting information at face value.

- Identifying Bias: Social media algorithms personalize content based on user preferences, creating echo chambers. Help students recognize bias by analyzing how different sources approach the same topic. Encourage them to seek out diverse perspectives actively.

2. Fact-Check Frenzy: Combating Misinformation and Fake News

The spread of misinformation is a major concern on social media. Here are some strategies to combat it:

- Fact-Checking Activities: Present students with a social media post containing controversial or potentially false information. Task them with using fact-checking websites like Snopes or PolitiFact to verify the information. Discuss the techniques used to identify misinformation.

- Create Counter-Narratives: Challenge students to create their own social media posts debunking common myths or misconceptions related to a particular topic. This encourages research and critical analysis.

- Healthy Skepticism: Promote a culture of healthy scepticism in the classroom. Encourage students to question everything they see online and not take information at face value.

3. The Power of Debate: Engaging in Civil Discourse

Social media fosters discussion, but these discussions can quickly devolve into heated arguments. Use social media to promote civil discourse:

- Online Debates: Set up online debates on social media platforms (e.g., closed Facebook groups) where students can discuss opposing viewpoints on a current event or historical issue. Provide guidelines for respectful communication and evidence-based arguments.

- Hashtags for Discussion: Develop classroom hashtags on platforms like Twitter to create a focused space for students to share perspectives and engage in respectful debates.

- Empathy and Understanding: Discuss the importance of listening to understand, not just to respond. Help students identify logical fallacies and emotional manipulation tactics used in online arguments.

4. Critical Consumers, Creative Creators:

Social media isn’t just about consuming information; it’s also about creating content. Empower students to become critical consumers and responsible creators:

- Analysing Social Media Ads: Social media advertising is a powerful tool. Guide students in deconstructing targeted ads by analysing the message, target audience, and persuasive techniques used. This helps them become more discerning consumers.

- Creating Responsible Content: Challenge students to create social media content that promotes critical thinking. This could involve infographics explaining complex topics, short videos debunking myths, or educational content on responsible social media usage.

- Digital Citizenship: Embed discussions about digital citizenship and online safety in your curriculum. Discuss topics like cyberbullying, privacy concerns, and responsible online behaviour.

5. Moderating and Facilitating Discussions

Educators are crucial in creating a safe and constructive learning environment within social media. Here’s how:

- Establish Ground Rules: Create clear guidelines for online discussions, emphasizing respect, evidence-based arguments, and avoiding personal attacks.

- Moderating Discussions: Actively monitor online discussions initiated by the class and intervene if necessary. Guide students back to respectful discourse and critical thinking practices.

- Amplifying Diverse Voices: Actively seek out and share diverse perspectives on social media platforms. Follow subject matter experts, scholars, and journalists who present a variety of viewpoints.

Social media isn’t inherently detrimental to critical thinking. By fostering a culture of questioning, analysis, and responsible content creation, educators can leverage these platforms to equip students with the tools they need to navigate the information age. In a world overflowing with digital noise, critical thinking is no longer a luxury; it’s a necessity. By harnessing the power of social media, we can empower students to become discerning consumers of information, responsible creators of content, and, most importantly, critical thinkers who can navigate the complexities of our digital world.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The State of Critical Thinking 2021

Introduction.

Social media’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric. In 2005, Facebook had around 5 million active users . As of 2020, more than 2.7 billion use the platform actively. Social media has inserted itself into almost every facet of human life. People use it to maintain relationships with family and friends, to share information on the tiniest aspects of daily life, such as the length of the grass in their lawn, and to get informed about what’s going on in the world.

Simply put, the adoption of social media is one of the most widespread and rapid changes in communications in human history. It shouldn’t be surprising, therefore, that it has come along with a number of drawbacks and challenges — not least of all to the way we think. The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated our use of social media, of course, making us far more likely to be on Twitter or Facebook. The pandemic has also exacerbated some of the challenges that come with social media, particularly around critical thinking and disinformation.

For these reasons, in our annual survey on the state of critical thinking, the Reboot Foundation asked people about their use of and views on social media, particularly as it related to their mental health. In the survey, our research team also asked questions about reasoning, media literacy, and critical thinking. Our goal was to take the temperature of popular opinion about social media and to gauge what, if anything, people think should be done to change their relationship with it.

Overall Findings

As social media use rises due to the pandemic, people are increasingly concerned about its impact on mental health.

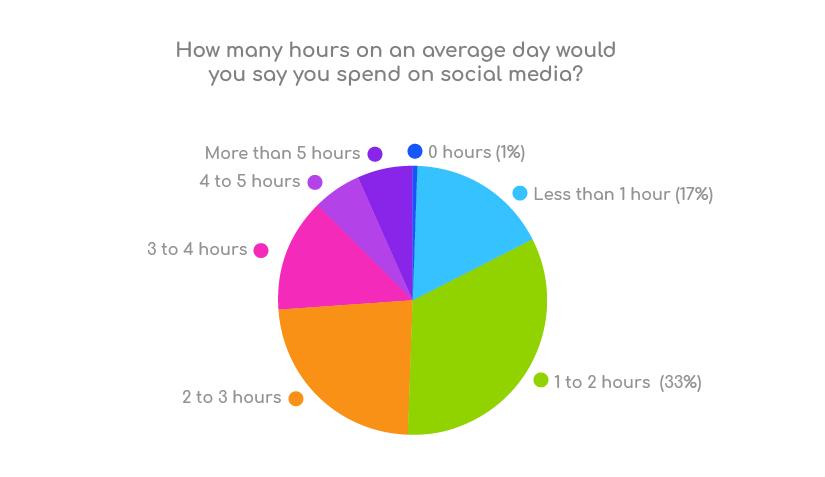

Over 60 percent of respondents said their social media use had gone up since the onset of COVID-19 lockdowns, while around half of respondents said they spend more than two hours a day on social media.

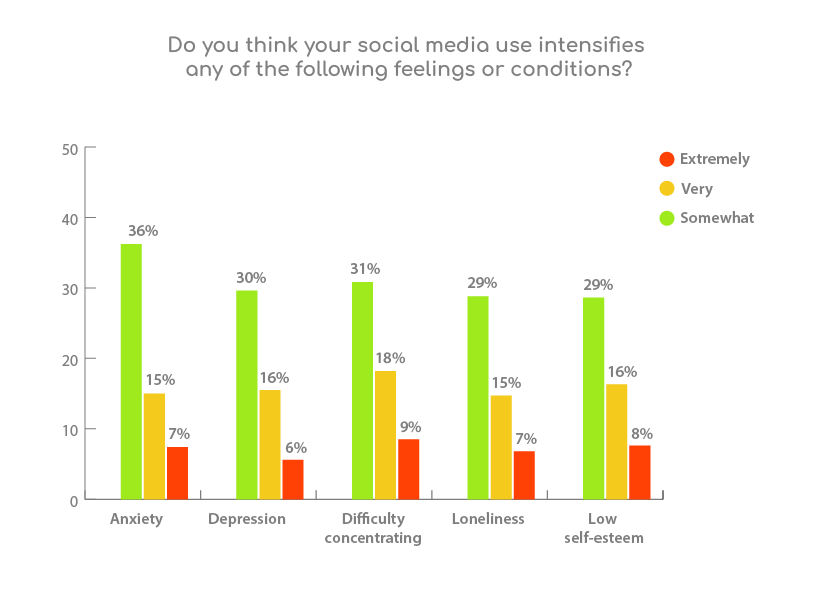

It is not surprising that people reported using social media more during the pandemic. Afterall, people have been asked to physically disconnect from family, friends, and coworkers. But the survey also showed that the public is deeply concerned about the mental health ramifications of rampant social media use. More than half said their social media use intensified feelings of anxiety and hindered their ability to concentrate.

Despite the general acknowledgment that social media is contributing to symptoms of poor mental health, a significant percentage of people aren’t willing to stop scrolling or to put down their screens.

There is a disconnect between how people see the impact of social media on society and how they view it on an individual level. Despite their concern about social media’s impact on public mental health, most individuals seem ambivalent about the role of social media in their own lives. To put it bluntly, everyone seems to think their own relationship to social media is healthier than the average.

This was clear in the survey. Over 70 percent of users said they would not give up their social media accounts for less than $10,000. Even more surprising, more than 40 percent said they would give up their TV, car, or pet before they disabled their social media pages.

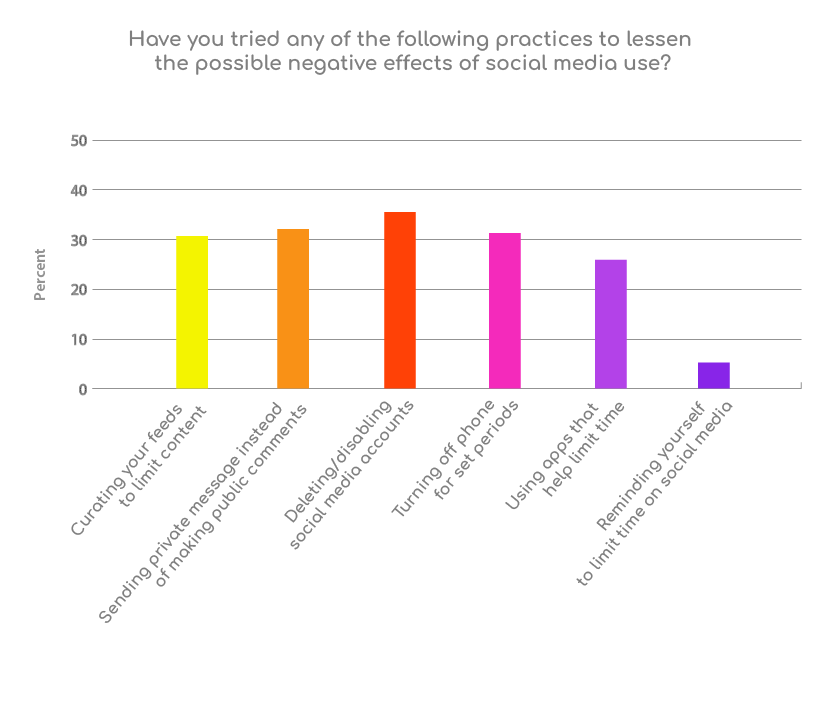

But despite being open to giving up Fido for Facebook, only about a third of respondents reported taking steps to limit their social media use, like turning off phones periodically or limiting content on their feeds.

When it comes to the impact of social media on political discourse, the public is similarly ambivalent. While many found social media damaging to their political reasoning, others thought they benefited from being exposed to new ideas online.

A related area of concern with social media is its impact on public discourse. In the survey, the public shows a lot of concern here as well, but, again, on an individual level people seem to view their own use of social media relatively positively.

While social media has contributed to polarization , exacerbated political biases , and even helped foster radicalism and violence , the survey found that individual users often think social media has helped expose them to alternative viewpoints, become better informed, and even articulate their own political views better.

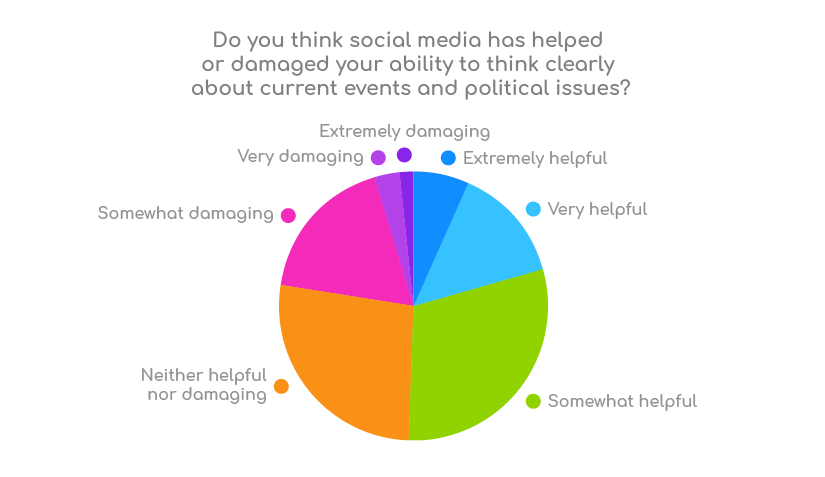

Slight majorities indicated that social media had a positive effect on their ability to assess sources of information and articulate their views clearly to others. And some 30 percent deemed social media “somewhat helpful” to their thinking about public issues.

These results suggest that efforts to improve public discourse online must be cognizant of social media’s real and perceived benefits, and focus on ways to preserve and amplify those benefits, while remediating the problems.

Support for critical thinking skills remains nearly universal, with equally strong support for the teaching of critical thinking at all levels of education.

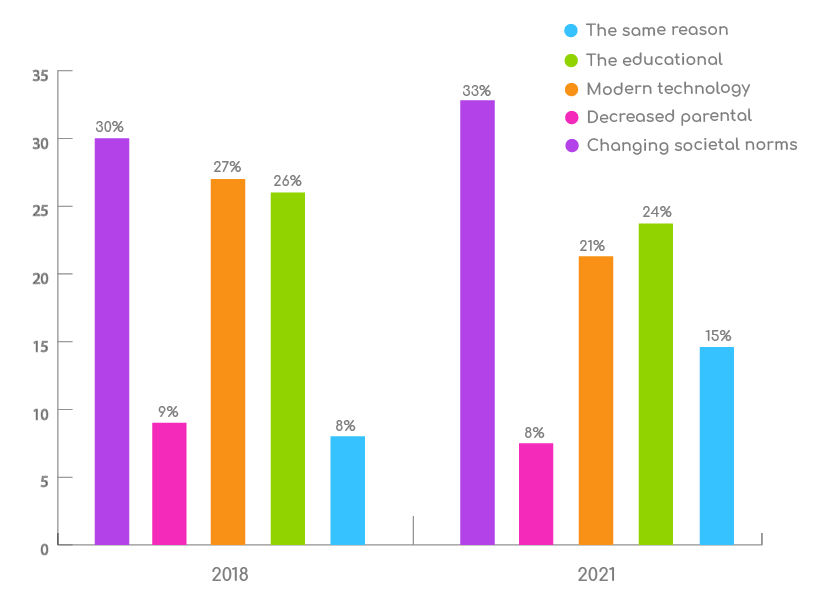

In the survey, 95 percent affirmed that critical thinking skills are important in today’s world, and an equal number said they believed those skills should be taught in K-12 schools. Another 85 percent of our respondents said critical thinking skills are generally lacking in the public. “Changing societal norms” was the most commonly cited reason for the lack of critical thinking skills.

When it comes to addressing some of the problems with social media, the good news is that support for critical thinking, in all sectors of society, is high, and people recognize these skills are lacking in the general population. Survey respondents also generally support dedicated critical thinking education, beginning at a young age. Coupled with the public’s understandable attachment to social media, this continued support for critical thinking suggests that the best avenue for addressing the problems with social media is better education at all levels of the society.

The survey was conducted through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) from March 3 to March 14, 2021.

Participants were recruited using methods that ensure high data quality. Only those with a 95 percent or higher approval rating on the service were permitted to participate, and they were compensated at a fair rate equal to at least $15 an hour. Furthermore, in order to prevent inattentive or overhasty answers, the team included an “attention check” question that filtered out respondents who were not answering thoughtfully.

Participants completed three sets of questions: first, a survey module on their social media use and opinions; second, a module on critical thinking; and last, a set of demographic questions. Questions with unordered (i.e., categorical) response sets had responses presented in a randomized order to each participant, in order to reduce question ordering effects.

Forty-four percent of our sample self-reported as female, 55 percent as male, and 1 percent as non-binary. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 78, with a modal age of 35. Sixty-six percent of participants had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. All participants were located in the United States. We sampled about equally from each US state to ensure a balanced geographic distribution.

To maintain consistency with the prior survey and to explore relationships across time, many of the questions remained the same from the 2018 and 2020 versions of the survey. In some cases, following best practices in questionnaire design, we revamped questions to improve clarity and increase the validity and reliability of the responses.

The survey was completed by 1,010 respondents. Its margin of error is 3 percent. The complete set of questions for each survey is available upon request.

Detailed Findings and Discussion

Social media use is up due to the pandemic, and people are concerned about its impact on mental health.

Unsurprisingly, COVID-19 lockdowns seem to have boosted people’s general social media use. Over 60 percent of respondents said their social media usage went up since COVID-19 lockdowns began in March 2020. Of those, around 36 percent said their usage had increased by an hour or more.

As other surveys have found, social media usage can end up taking up a large portion of people’s day. Around half of the respondents to Reboot’s survey said they spent more than 2 hours a day on social media, with 12 percent indicating they spend more than 4 hours a day on social media.

These estimates are in line with research that indicates Americans spent an average of 82 minutes a day on social media in 2020, up from 75 minutes in 2019.

None of this is particularly surprising. During a year when in-person social contact was dramatically constrained by COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions, stromectol , people took to social media more than ever before to keep up-to-date with family and friends, as well as to pass the time at home.

There is some evidence that this newfound reliance on social media may have prevented growth in social media use from stalling, as well as helped deflect some negative attention around social media.

Before the pandemic new user numbers were actually stagnant or even in decline in the United States. And during the worldwide political upheaval since the rise of right-wing populism around 2016, social media has taken much of the blame for extremism and a generally toxic political discourse. It will be interesting to see if negative social media sentiment rebounds and usage dips in a post-pandemic environment, or, whether, conversely, a year plus of using social media more has changed people’s habits in the long run.

The Reboot survey also asked participants to evaluate the impact of social media on their own mental health. Of course, self-reports of mental health outcomes have limitations. These results aren’t close to as reliable as a diagnosis by a medical professional. Still, they can help understand public sentiment on the issue, especially as social media and the problems around it become more prominent, both in public discourse and in social science research.

The most striking results came on questions about specific mental-health impacts. Participants were asked whether they thought their social media use intensified any of the following feelings or conditions: anxiety, depression, difficulty concentrating, loneliness, or low self-esteem.

For each of these conditions, more than 50 percent of respondents indicated those feelings were at least “somewhat” intensified by social media, while at least 20 percent for each option indicated they were “very” or “extremely” intensified. People seemed to have the most trouble with anxiety and difficulty concentrating, with nearly 60 percent in both cases reporting some negative effects from social media usage.

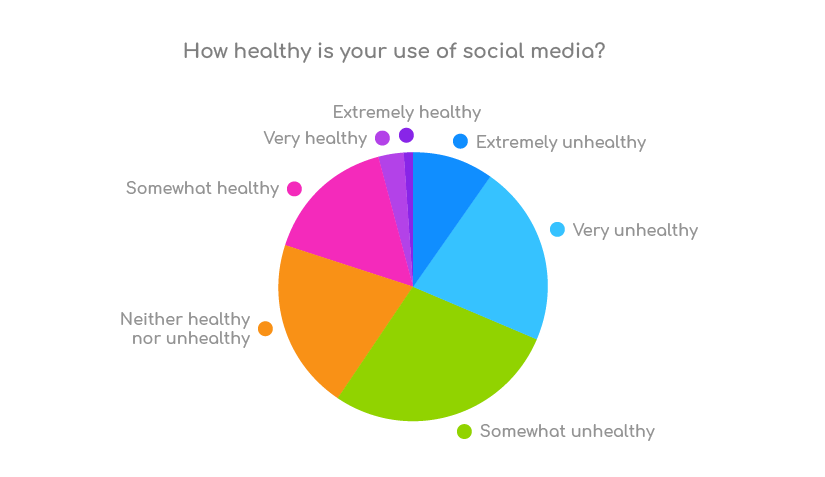

A substantial number of those surveyed also expressed general concern about social media’s mental health impacts. Around 20 percent described their social media use as somewhere on the range of “unhealthy.” Given people’s natural proclivity against admitting to unhealthy behavior, that number is significant. That said, more than half described their use as “somewhat,” “very,” or “extremely healthy.”

Meanwhile, when asked to evaluate the overall impact of social media on their mental health, around a third of respondents said social media had a “somewhat,” “very,” or “extremely” negative impact. Overall, the survey paints a picture of a majority of users who feel they are able to use social media without doing serious harm to their mental health, but nonetheless do experience negative impacts. There is also a significant minority that is more concerned about the impact of social media usage on their mental health.

Participants expressed even more concern when asked about the impact of social media on the public at large, instead of on their own personal lives. Over 80 percent reported a “moderate” level of concern or greater, with over 50 percent indicating they were “very” or “extremely” concerned.

Despite the general acknowledgement that social media is contributing to symptoms of poor mental health, a significant percentage of people still aren’t willing to stop scrolling or to put down their screens.

Social media addiction — and technology addiction more broadly — are also areas where further research is needed. Although survey participants reported concern about their own social media use, they were generally more concerned about the impact on society. This suggests that despite high levels of concern about social media overuse and addiction generally, many people might not see the problem as significant enough in their own lives to take action on an individual level.

Indeed, the survey found mixed results when it came to participants taking steps to limit social media use in participants’ personal lives. Only about a third or less of respondents reported that they had taken concrete steps to limit their social media use, like deleting or suspending social media accounts, turning off their phones, or limiting content on their feeds.

Moreover, when asked hypothetically how much money at minimum they would require to delete all their social media accounts permanently, over 70 percent said it would take $10,000 or more, with 20 percent saying it would take at least $1 million. Similarly, 42 percent said they’d give up their TV, pet, or car before giving up their social media accounts.

The survey’s results parallel a growing, but still inconclusive, body of social science research into the effects of social media on mental health. A number of studies suggest links between adolescent anxiety and depression, especially among girls, and social media use. (1) Other research has explicitly focused on social media addiction and its connections to mental health disorders. (2) More specifically, researchers have linked depression to social media behaviors like comparing oneself to others who seem better off and worrying about being tagged in unflattering pictures.

But the research is by no means settled, especially since many of social media’s most addictive features, like “like” buttons and feeds with sophisticated algorithms based on user data , have only become widespread over the last decade or so. A number of methodological issues complicate research in this area: studies to date tend to focus too much on self-reports; social media companies themselves control the bulk of the data ; negative mental health outcomes tend to be complicated and multi-factor. Good data that can support solid, statistically significant conclusions remains, therefore, hard to come by.

Moreover, other studies have found little or no reason to conclude that social media has a negative impact on mental health, (3) including adolescent mental health. Some researchers have even gone so far as to compare current levels of concern about social media and mental health to prior “ technology panics .” (4) For example, widespread concern about links between real-world violence and violent video games in the 1990s hasn’t been borne out by research.

It is important to study the issue with care, then, and to remain aware of positive impacts social media can have. More research needs to be done, among different population types, before any definitive conclusions can be ventured.

Still, given the significant changes to social life brought about social media, especially among young people and especially during the pandemic, it would also be a mistake to ignore these concerns. The internet and social media clearly foster radically new kinds of social interaction and communication, while enabling new kinds of manipulation and addiction. That doesn’t mean an outright panic is justified, but it does mean social media’s social impact — both negative and positive — is well-worth concern and study.

When it comes to the impact of social media on political discourse, the public is ambivalent. While many found social media damaging to their political reasoning; others thought the way it had exposed them to new ideas was beneficial.

In addition to mental health impacts, commentators and researchers have long been concerned about the impact of social media on our political discourse. More specifically, social media has been implicated in the rise of racist and authoritarian ideas and conspiracy theories , initially on less mainstream forums like 4chan , but later on mainstream social media like Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter. It has contributed heavily to shocking democratic outcomes , including Brexit and Donald Trump’s election in 2016. (5) It’s also contributed to violence around the world , from countries with authoritarian governments like the Philippines to democracies like the United States, where social media activity fueled the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Furthermore, social media is typically cited, with good reason, as a cause of polarization and dysfunction in democratic discourse. (6) Social media enables structures that tend to decrease the quality and increase the intensity of debate : these include filter bubbles that expose users to only viewpoints they already agree with; Twitter dynamics that fuel pile-on and extremism; and algorithms that prioritize sensationalistic and personalized content that keeps users scrolling.

That said, it would perhaps be overhasty to deem that social media’s impact on public discourse has been all negative. In fact, somewhat surprisingly, the respondents to our survey viewed social media’s impact on their own thinking on current events and politics in neutral or even slightly positive ways.

A plurality of 30 percent indicated that social media had been “somewhat helpful,” when asked whether it was helpful or damaging to their thinking about contemporary issues. Only around 5 percent indicated it had been “very” or “extremely damaging,” although nearly 20 percent thought it had been somewhat damaging.

Although it might be taken for granted that social media has been polarizing, respondents’ opinion was split, with 27 percent saying they had become less tolerant due to social media, and 43 percent saying social media had made them more tolerant of different views. Around the same number (46 percent) indicated social media had “somewhat increased” the diversity of the news they consumed. (Again, it is worth keeping in mind that self-reports tend to be more flattering than the actuality.)

In the survey, significant numbers thought social media had positive impacts on their media literacy skills. Thirty-eight percent indicated they engage more deeply with social and political issues due to social media, as opposed to 27 percent saying they engage less deeply. And slight majorities said social media affected their ability to assess sources of information at least “somewhat positively” (51 percent) and made them better able to express their views clearly to others (55 percent).

These mixed opinions reflect the ambiguous place social media holds in our public discourse. People seem to be generally wary of the pitfalls of social media, especially around political content, but are unlikely to completely condemn it, especially when evaluating its impact on them personally.

Other recent research has come to similar conclusions. A Pew survey found that people were optimistic about the role social media can play in building social movements, even while they worried about the distractions it can cause. Another Pew survey , meanwhile, found that 55 percent of Americans describe themselves as feeling “worn out” by political posts and discussions, while 70 percent found it “stressful and frustrating” to discuss politics with those they disagree with on social media.

Given these attitudes, it seems clear that we can neither dismiss the problems associated with social media, nor expect people to simply give up their social media accounts. What is needed is a concerted effort to give people the cognitive tools to manage the dangers of social media addiction; to engage productively with valuable information and opinion they find online; and, perhaps most importantly, to recognize and avoid low-quality information and opinion that is not worth engaging with.

Each year, Reboot takes stock of the public’s attitude towards critical thinking and specific critical thinking practices. This year, as expected, general support for critical thinking remains high. Ninety-five percent of respondents affirm that critical thinking skills are important in today’s world, and, similar to previous years, 85 percent believe that they are generally lacking in the public.

Interestingly, when asked for the main reason for the lack of critical thinking skills, “changing societal norms” took the blame much more than in past years, with almost a third of respondents choosing it. Modern technology (21 percent) and the education system (24 percent), were the other significant targets of blame.

There were some changes over time, as the chart below shows. But none of the shifts were very large, except for a shift in the idea that students have always lacked critical thinking due to the “same reason they always lacked these skills.” That grew by more than 5 percentage points.

The education system, in general, is not highly regarded when it comes to teaching critical thinking, with only a quarter of respondents saying they received an “extremely” or “very” strong background in critical thinking from their schools. About the same number (26 percent) described the background provided as “not strong at all,” with another 23 percent calling it only “slightly strong.” More than half the participants indicated that they did not study critical thinking in school.

| A lot of critical thinking development happens in early childhood. But, unsurprisingly, given people’s experiences with critical thinking in school, there is some uncertainty about when it should be taught. Only about half the respondents thought it best to teach critical thinking skills before the age of 12, despite that these early years are a crucial time to start learning these skills. That number is down significantly from last year’s survey when over 70 percent indicated they thought children were best suited to learn these skills early. Furthermore, just 22.8 percent thought “early childhood” (before the age of 6) was the best age to develop these skills (down from 43 percent in our last survey). Given what we know about the importance of , this is somewhat disconcerting. It may reflect a false belief that critical thinking is a “high-level” skill only suitable for advanced students. In reality, young children do than adults tend to give them credit for. Moreover, children are now being exposed earlier and earlier in their lives to social media and other technology that poses significant challenges to clear thinking. This means early education in critical thinking is more important than ever. |

When people reflect on their critical thinking development after high school, the results are not much better. Only half of the respondents said their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with around 16 percent saying their critical thinking skills had actually deteriorated.

There are some positive signs that education in critical thinking and relative fields like civics and media literacy is becoming a priority. Organizations like NAMLE (National Association for Media Literacy Education) and Media Literacy Now are developing curricula and programs to improve media literacy across grade level and in continuing education. The Department of Education and National Endowment for the Humanities have also recently spearheaded an initiative to reinvigorate civics education. The Reboot Foundation has also developed materials for critical thinking , media literacy , and civics education. But overall, as the survey responses’ confirm, there remains a significant discrepancy between how highly critical thinking skills are valued and how few resources are put to use to advance them.

As behavioral psychologists like Daniel Kahneman have noted , the human brain is a product of evolution that has developed to cope with certain conditions and respond to certain stimuli. (10)

Although the brain has become very sophisticated, this evolutionary process has also left us with certain biases and shortcuts in reasoning that can lead to error, especially in highly complex, information-rich modern societies. By changing the environment in which we reason, social media — and the internet in general — can exacerbate these biases and distort our thought processes in a number of different ways.

For instance, algorithms prioritize “high-engagement,” sensationalized content that can create emotional, irrational responses. Depending on how their feeds are curated, people may end up being exposed only or predominantly to ideas that confirm what they already think, missing out on the challenges to prejudice and preconceptions that are essential to good reasoning. Finally, a flattened-out environment without the depth and texture of face-to-face conversations can lead to misinterpretations and misunderstandings, and cause hostility and conflict.

The distorted thinking that results from the social media environment can have widespread negative social consequences, both in terms of public mental health and public discourse, as the survey respondents recognized.

Critical thinking education, including education in civics and media literacy, is the natural and needed companion to social media. People better trained in good reasoning practices like evaluating sources, weighing opposing views, and formulating logically sound arguments, will also be better able to navigate online life more carefully and thoughtfully. They will be less susceptible to the confirmation bias, groupthink, and ad hominem argumentation that are so widespread in these environments.

Interestingly, many of these critical thinking practices are also relevant to addressing the negative effects of social media on mental health . Adherents of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for example, have emphasized the extent to which anxiety and depression can be caused and exacerbated by negative thinking patterns . To the extent that social media can reinforce or help foster these thinking patterns, it may be contributing to what has been described as a “ mental health crisis ,” especially among adolescents and young adults. CBT, like critical thinking, involves identifying these distortions and developing the habits of mind to resist them. Better integrating these critical thinking practices into our education system will help young people develop the tools they need to navigate the online world in a healthy and productive way.

This does not require a radical overhaul of the curriculum. Instead, what’s needed is a recommitment to the principles of education in the liberal arts and sciences, which already emphasize many of these practices. Too often students are, instead, subjected to a testing-oriented curriculum that gives them a narrow view of thinking and education.

Teaching in these areas gets too bogged down in finding right answers, and applying rote processes to fixed and unrealistic problems. There is not enough open-ended questioning and real-world reasoning and interpretation. Students don’t spend enough time talking about the first principles and logic behind the disciplines they are studying. And they don’t develop skills in articulating their own viewpoints persuasively and cogently, in both writing and speech.

In short, what’s needed is ideas for integrating critical thinking into the curriculum. Reboot has contributed to this mission with its Teachers’ Guide , which offers teachers ideas to inject critical thinking into existing lesson plans. These efforts do not just add needed skills to students’ education; they should also help with motivation and the love of learning, since critical thinking is a creative, open-ended process that builds on students’ own interests and opinions.

The overall goal is a population — and society as a whole — that values patient engagement and reasoned argument over sensationalism and gut responses, and one that is able to use technology mindfully and productively.

To download the PDF of this survey,

(please click here)

(1)* Haidt, J., & Allen, N. (2020). Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health. Nature 578 , 226-227. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x (2)* Robinson, A., Bonnette, A., Howard, K., Ceballos, N., Dailey, S., Lu, Y., & Grimes, T. (2019). Social comparisons, social media addiction, and social interaction: An examination of specific social media behaviors related to major depressive disorder in a millennial population. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12158

(3)* Orben, A., & Przybylski, A.K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour 3 , 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1