How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

How to formulate a research strategy?

A research strategy refers to a step-by-step plan of action that gives direction to the researcher’s thought process. It enables a researcher to conduct the research systematically and on schedule. The main purpose is to introduce the principal components of the study such as the research topic, areas, major focus, research design and finally the research methods.

An appropriate strategy has to be selected on the basis of the following:

- Research questions.

- Research objectives.

- Amount of time available.

- Resources at the researcher’s disposal.

- Philosophical underpinnings of the researcher.

Types of research strategies

Research strategy helps a researcher choose the right data collection and analysis procedure. Thus, it is of utmost importance to choose the right strategy while conducting the research. The following section will focus on the different types of strategies that can be used.

- Qualitative: This strategy is generally used when to understand the underlying reasons or the opinion of the people on certain facts or a problem. It does not involve numerical data. It provides insights into the research problem and hence helps in achieving the research objectives. Various methods that can be used include interviews, observations, open-ended surveys and focus group discussions.

- Quantitative: It involves the collection of primary or secondary data which is in numerical form. Under this strategy, the researcher can collect the data by using questionnaires, polls and surveys or through secondary sources. This strategy mainly focuses on when, where, what and how often a specific phenomenon occurs.

- Descriptive: This is generally used when the researcher wants to describe a particular situation. This involves observing and describing the behaviour patterns of either an individual, community or any group. One thing that distinguishes it from other forms of research strategies is that subjects are observed in a completely unchanged environment. Under this approach surveys, observations and case studies are mainly used to collect the data and to understand the specific set of variables.

- Analytical: This involves the use of already available information. Here the researcher in an attempt to understand the complex problem set, studies and analyses the available data. It majorly concerns the cause-and-effect relationship. The scientifically based problem-solving approaches mainly use this strategy.

- Action: This strategy aims at finding solutions to an immediate problem. It is generally applied by an agency, company or by government in order to address a particular problem and find possible solutions to it. For example, finding which strategy could best work out to motivate physically challenged students.

- Basic: According to this strategy no generalizations are made in order to understand the subject in a better and more precise way. Thus, it involves investigation and the analysis of a phenomenon. Although their findings are not directly applicable in the real world, they work towards enhancing the knowledge base.

- Critical: It works towards analyzing the claims regarding a particular society. For example, a researcher can focus on any conclusion or theory made regarding a particular society or culture and test it empirically through a survey or experiment.

- Interpretive: this strategy is similar to the qualitative research strategy. However, rather than using hypothesis testing, interpretation is done through the sense-making process. In simple terms, this strategy uses human experience in order to understand the phenomena.

- Exploratory: It is mainly used to gain insights into the problem or regarding certain situations but does work towards providing the solution to the research problem. This research strategy is generally undertaken when there is very little or no earlier study on the research topic.

- Predictive: It deals with developing an understanding of the future of the research problem and has its foundation based on probability. This is generally very popular among companies and organizations.

Difference between the types of research strategy

| Strategy | Definition | Purpose | Example aim |

|---|---|---|---|

| strategy | A method of observation to collect non-numerical data. | It is useful when the researcher wants to understand the underlying reasons or the opinion of the people on certain facts or the problem. | An in-depth analysis of perceptions of occupants in an old-age home regarding the quality of service. |

| strategy | Research involves the collection of numerical data in the form of surveys or through secondary sources. | To investigate when, where, what and how often a specific phenomenon occurs. | A survey on the effectiveness of online marketing strategies on consumer satisfaction of Unilever in India. |

| Descriptive research strategy | This majorly involves observing and describing the behaviour pattern of either an individual, community or any group to be specific. | Generally used when the researcher wants to describe a particular situation. | To understand the social status of working women in a specific region of a country. |

| Analytical research strategy | This form of research strategy involves the use of already available information. | To examine the cause-and-effect relationship between two or more variables. | To understand the impact of certain policy decisions on the gross domestic product of an economy. |

| Action research strategy | It aims at finding solutions to an immediate problem. | Applied by agencies, companies or governments in order to address a problem and find possible solutions. | Determining which strategy would work best to motivate physically challenged students. |

| Basic research strategy | Involves investigation and the analysis of a phenomenon. | Works towards enhancing the existing knowledge base. | To identify the reason behind the breakout of certain epidemics in certain regions. |

| strategy | The strategy focuses on critically analyzing prior findings of a research. | Works towards analyzing the claims regarding a particular society or phenomenon. | To analyze the claims made by another study regarding the temperature conditions in the next 10 years. |

| Interpretive research strategy | This strategy uses human experience in order to understand a research problem. | Applicable when the researcher wants to understand the underlying reasons or the opinion of the people on certain facts or the problem. | To determine and analyse the problems faced by women in their society or household. |

| Exploratory research strategy | Used to gain insights into the problem or regarding certain situations but works towards providing the solution to the research problem. | Undertaken when there is very little or no earlier study on the research topic. | To understand in depth the problems faced by working women in Northern India. |

| Predictive research strategy | This form of research strategy deals with developing an understanding of the future of a research problem and has its foundation based on probability. | Used for studies and problems that require prediction of future trends. | To predict future sales or increase in customers before the launch of certain new products. |

How to write a research strategy

The main components of a research strategy include the research paradigm, research design, research method and sampling strategy. It should be in a form such that your research paradigm should guide your research design. Which in turn should lead to the appropriate selection of the research methods along with the correct sampling strategy. It is applicable to different kinds of research such as exploratory, explanatory and descriptive.

Step1: Defining the research paradigm

This involves a basic set of beliefs that guides the researcher regarding the way of performing the research. There are various types of research paradigms, including positivism, post-positivism or constructivism.

Step 2: Defining the research design

The research paradigm and the type of research mainly guide the choice of research design. For example, some researches that include experiments lean quantitative research design. On the other hand, exploratory research in social sciences often uses a qualitative research design. This must be done very carefully because the research design will eventually impact the choice of research method and sampling strategy.

Step 3: Defining research methods

This step helps the researcher to explain the potential methods that can be used for carrying out the research. The choice here also depends on the research paradigm and research design selected in the above steps. For example, if a researcher followed a constructivist paradigm using a qualitative research design, then the data collection method can be interviews, observation or focus group discussions.

Step 4: Defining the sampling strategy

This step involves specifying the population, sample size and sampling type for a study. In the population, the researcher defines the profile of respondents and justifies their suitability for the study. For defining the sample size , a specific formula can be applied. Finally, there are many sampling types for a researcher to choose from.

Things to keep in mind while writing research strategies

As there exist different types of research strategies, for the researcher, order to embark according to the study needs he or must identify the three main questions in order to write an appropriate strategy.

Is it suitable for the research aim?

As shown in the figure above the first thing that needs to be kept in mind is that the strategy should be suitable with respect to the purpose of the study i.e. it should rather support the researcher in finding the answers to the research questions which are under the consideration.

For example, a case study may be considered the right choice when investigating the social relationship in some specific setting, while it might be probably inappropriate when it comes to measuring the attitude of a large population.

Feasibility as per available sources

The second point that needs to be considered, is that it should be feasible from the practical point of view. The researcher should formulate the strategy so that he or she had complete access to data sources. Also, some of the research strategies like action research which are generally highly time-consuming, thus the researcher must consider all these aspects while preparing the strategy.

Ethical considerations

Also, another point that needs to be considered, is that the researcher should ensure that the strategy chosen must be followed in a responsible way. For example, in social science research participants of the study should be allowed to remain anonymous.

- Priya Chetty

- Ashni walia

I am a management graduate with specialisation in Marketing and Finance. I have over 12 years' experience in research and analysis. This includes fundamental and applied research in the domains of management and social sciences. I am well versed with academic research principles. Over the years i have developed a mastery in different types of data analysis on different applications like SPSS, Amos, and NVIVO. My expertise lies in inferring the findings and creating actionable strategies based on them.

Over the past decade I have also built a profile as a researcher on Project Guru's Knowledge Tank division. I have penned over 200 articles that have earned me 400+ citations so far. My Google Scholar profile can be accessed here .

I now consult university faculty through Faculty Development Programs (FDPs) on the latest developments in the field of research. I also guide individual researchers on how they can commercialise their inventions or research findings. Other developments im actively involved in at Project Guru include strengthening the "Publish" division as a bridge between industry and academia by bringing together experienced research persons, learners, and practitioners to collaboratively work on a common goal.

I am a master's in Economics from Amity university. Besides my keen interest in Economics i have been an active member of the team Enactus. Apart from the academics i love reading fictions.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

proofreading

How to Conduct a Strategic Research Project

The best way to reach the goals you set for your business is to implement corresponding strategies. While you can easily set ambitious objectives, working out the details of how to achieve them requires research into your business environment. A strategic research project aimed at exploring possible strategies and their chances for success is an effective approach. It can match your strengths and capabilities to the opportunities presented by your market to show you how best to proceed.

Find Reliable Sources of Information

Three factors that affect the success of possible strategies are the attitudes of your customers, the actions of your competitors and any regulatory or legal restrictions you may encounter. You can find out what customers think about your company, your products and your competitors by carrying out customer surveys and by asking your sales and service staff what customer feedback they have received. You can obtain information about other companies through their websites and their annual reports. Government publications and websites tell you whether there are regulations and legal constraints that apply to your area of activity. You can focus your strategic research on the direction you want to take, or you can gather general information to guide you in finding an effective strategy.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

More For You

How to increase company growth, what should an objective statement of a company describe, difference between qualitative & quantitative analysis for managerial decision making, how to analyze the effects of channel management, product diversification strategy, quantitative and qualitative data.

The information you obtain is both qualitative and quantitative, and you have to separate the two kinds of data to analyze them independently. For example, interviews with customers yield qualitative data based on what your customers are saying. You might find out that your customers think highly of your company, like one of your products, think another one is of poor quality and like the service of a competitor. You can use quantitative data to check whether your information is correct. For example, if the poor-quality product has high rates of return and high warranty claims, that's quantitative data that backs up the information from your interviews.

Explore Company Relationships

Implementing a new strategy sometimes involves other organizations with which you have relationships. You should talk with your bank, because your strategy might need additional financing. If your new strategy could lead to rapid expansion of a particular product line, explore whether your major suppliers can handle the extra business. Look at forming new partnerships with successful businesses in areas that complement your own. Evaluating existing business relationships and researching new opportunities may influence your strategic direction.

Use Goals to Guide Strategy

You can complete your project by evaluating how the research you have done supports company goals. Your research shows you what your company does well, where your business can improve and where in your business environment you should focus your strategic efforts. For example, if your customers don't like one of your products, a strategy to promote it makes no sense. Instead, you can implement a strategy to improve the product, replace it, or promote another, more popular product. Which of these strategies you choose depends on your company's goals. If you want to increase sales, you have to improve the product or promote another one. If your goal is to be known for high-quality products, you should drop the product or replace it.

- Corporate Research Project: How to Do Corporate Research

- Blackwell's: Business Research Strategies

- Texas A&M Transportation Institute: Innovative Finance - Strategic Research Project

Bert Markgraf is a freelance writer with a strong science and engineering background. He started writing technical papers while working as an engineer in the 1980s. More recently, after starting his own business in IT, he helped organize an online community for which he wrote and edited articles as managing editor, business and economics. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree from McGill University.

Writing a Research Strategy

This page is focused on providing practical tips and suggestions for preparing The Research Strategy, the primary component of an application's Research Plan along with the Specific Aims. The guidance on this page is primarily geared towards an R01-style application, however, much of it is useful for other grant types as well.

Developing the Research Strategy

The primary audience for your application is your peer review group. When writing your Research Strategy, your goal is to present a well-organized, visually appealing, and readable description of your proposed project and the rationale for pursuing it. Your writing should be streamlined and organized so your reviewers can readily grasp the information. If it's a key point, repeat it, then repeat it again. Add more emphasis by putting the text in bold , or bold italics . If writing is not your forte, get help. For more information, please visit W riting For Reviewers .

How to Organize the Research Strategy Section

How to organize a Research Strategy is largely up to the applicant. Start by following the NIH application instructions and guidelines for formatting attachments such as the research plan section.

It is generally structured as follows:

Significance

For Preliminary Studies (for new applications) or a Progress Report (for renewal and revision applications).

- You can either include preliminary studies or progress report information as a subsection of Approach or integrate it into any or all of the three main sections.

- If you do the latter, be sure to mark the information clearly, for example, with a bold subhead.

Helpful tips to consider when formatting:

- Organize using bold headers or an outline or numbering system—or both—that are used consistently throughout.

- Start each section with the appropriate header: Significance, Innovation, or Approach.

- Organize the Approach section around the Specific Aims.

For most applications, you need to address Rigor ous Study Design by describing the experimental design and methods you propose and how they will achieve robust and unbiased results. See the NIH guidance for elaboration on the 4 major areas of rigor and transparency emphasized in grant review. These requirements apply to research grant, career development, fellowship, and training applications.

Tips for Drafting Sections of the Research Strategy

Although you will emphasize your project's significance throughout the application, the Significance section should give the most details. The farther removed your reviewers are from your field, the more information you'll need to provide on basic biology, importance of the area, research opportunities, and new findings. Reviewing the potentially relevant study section rosters may give you some ideas as to general reviewer expertise. You will also need to describe the prior and preliminary studies that provide a strong scientific rationale for pursuing the proposed studies, emphasizing the strengths and weaknesses in the rigor and transparency of these key studies.

This section gives you the chance to explain how your application is conceptually and/or technically innovative. Some examples as to how you might do this could include but not limited to:

- Demonstrate the proposed research is new and unique, e.g., explores new scientific avenues, has a novel hypothesis, will create new knowledge.

- Explain how the proposed work can refine, improve, or propose a new application of an existing concept or method.

If your proposal is paradigm-shifting or challenges commonly held beliefs, be sure that you include sufficient evidence in your preliminary data to convince reviewers, including strong rationale, data supporting the approach, and clear feasibility. Your job is to make the reviewers feel confident that the risk is worth taking.

For projects predominantly focused on innovation and outside-the-box research, investigators may wish to consider mechanisms other than R01s for example (e.g., exploratory/developmental research (R21) grants, NIH Director's Pioneer Award Program (DP1), and NIH Director's New Innovator Award Program (DP2).

The Approach section is where the experimental design is described. Expect your assigned reviewers to scrutinize your approach: they will want to know what you plan to do, how you plan to do it, and whether you can do it. NIH data show that of the peer review criteria, approach has the highest correlation with the overall impact score. Importantly, elements of rigorous study design should be addressed in this section, such as plans for minimization of bias (e.g. methods for blinding and treatment randomization) and consideration of relevant biological variables. Likewise, be sure to lay out a plan for alternative experiments and approaches in case you get uninterpretable or surprising results, and also consider limitations of the study and alternative interpretations. Point out any procedures, situations, or materials that may be hazardous to personnel and precautions to be exercised. A full discussion on the use of select agents should appear in the Select Agent Research attachment. Consider including a timeline demonstrating anticipated completion of the Aims.

Here are some pointers to consider when organizing your Approach section:

- Enter a bold header for each Specific Aim.

- Under each aim, describe the experiments.

- If you get result X, you will follow pathway X; if you get result Y, you will follow pathway Y.

- Consider illustrating this with a flowchart.

Preliminary Studies

If submitting a new application to a NOFO that allows preliminary data, it is strongly encouraged to include preliminary studies. Preliminary studies demonstrate competency in the methods and interpretation. Well-designed and robust preliminary studies also serve to provide a strong scientific rationale for the proposed follow-up experiments. Reviewers also use preliminary studies together with the biosketches to assess the investigator review criterion, which reflects the competence of the research team. Provide alternative interpretations to your data to show reviewers you've thought through problems in-depth and are prepared to meet future challenges. As noted above, preliminary data can be put anywhere in the Research Strategy, but just make sure reviewers will be able to distinguish it from the proposed studies. Alternatively, it can be a separate section with its own header.

Progress Reports

If applying for a renewal or a revision (a competing supplement to an existing grant), include a progress report for reviewers.

Create a header so reviewers can easily find it and include the following information:

- Project period beginning and end dates.

- Summary of the importance and robustness of the completed findings in relation to the Specific Aims.

- Account of published and unpublished results, highlighting progress toward achieving your Specific Aims.

Other Helpful Tips

Referencing publications.

References show breadth of knowledge of the field and provide a scientific foundation for your application. If a critical work is omitted, reviewers may assume the applicant is not aware of it or deliberately ignoring it.

Throughout the application, reference all relevant publications for the concepts underlying your research and your methods. Remember the strengths and weaknesses in the rigor of the key studies you cite for justifying your proposal will need to be discussed in the Significance and/or Approach sections.

Read more about Bibliography and References Cited at Additional Application Elements .

Graphics can illustrate complex information in a small space and add visual interest to your application. Including schematics, tables, illustrations, graphs, and other types of graphics can enhance applications. Consider adding a timetable or flowchart to illustrate your experimental plan, including decision trees with alternative experimental pathways to help your reviewers understand your plans.

Video may enhance your application beyond what graphics alone can achieve. If you plan to send one or more videos, you'll need to meet certain requirements and include key information in your Research Strategy. State in your cover letter that a video will be included in your application (don't attach your files to the application). After you apply and get assignment information from the Commons, ask your assigned Scientific Review Officer (SRO) how your business official should send the files. Your video files are due at least one month before the peer review meeting.

However, you can't count on all reviewers being able to see or hear video, so you'll want to be strategic in how you incorporate it into your application by taking the following steps:

- Caption any narration in the video.

- Include key images from the video

- Write a description of the video, so the text would make sense even without the video.

Tracking for Your Budget

As you design your experiments, keep a running tab of the following essential data:

- Who. A list of people who will help (for the Key Personnel section later).

- What. A list of equipment and supplies for the experiments

- Time. Notes on how long each step takes. Timing directly affects the budget as well as how many Specific Aims can realistically be achieved.

Jotting this information down will help when Creating a Budget and complete other sections later.

Review and Finalize Your Research Plan

Critically review the research plan through the lens of a reviewer to identify potential questions or weak spots.

Enlist others to review your application with a fresh eye. Include people who aren't familiar with the research to make sure the proposed work is clear to someone outside the field.

When finalizing the details of the Research Strategy, revisit and revise the Specific Aims as needed. Please see Writing Specific Aims .

Want to contact NINDS staff? Please visit our Find Your NINDS Program Officer page to learn more about contacting Program Officer, Grants Management Specialists, Scientific Review Officers, and Health Program Specialists. Find NINDS Program Officer

Strategic Analysis

The process of conducting research on a company and its operating environment to formulate a strategy

What is Strategic Analysis?

Strategic analysis refers to the process of conducting research on a company and its operating environment to formulate a strategy. The definition of strategic analysis may differ from an academic or business perspective, but the process involves several common factors:

- Identifying and evaluating data relevant to the company’s strategy

- Defining the internal and external environments to be analyzed

- Using several analytic methods such as Porter’s five forces analysis, SWOT analysis , and value chain analysis

What is Strategy?

A strategy is a plan of actions taken by managers to achieve the company’s overall goal and other subsidiary goals. It often determines the success of a company. In strategy, a company is essentially asking itself, “Where do you want to play and how are you going to win?” The following guide gives a high-level overview of business strategy, its implementation, and the processes that lead to business success.

Vision, Mission, and Values

To develop a business strategy, a company needs a very well-defined understanding of what it is and what it represents. Strategists need to look at the following:

- Vision – What it wants to achieve in the future (5-10 years)

- Mission Statement – What business a company is in and how it rallies people

- Values – The fundamental beliefs of an organization reflecting its commitments and ethics

After gaining a deep understanding of the company’s vision, mission, and values, strategists can help the business undergo a strategic analysis. The purpose of a strategic analysis is to analyze an organization’s external and internal environment, assess current strategies, and generate and evaluate the most successful strategic alternatives.

Strategic Analysis Process

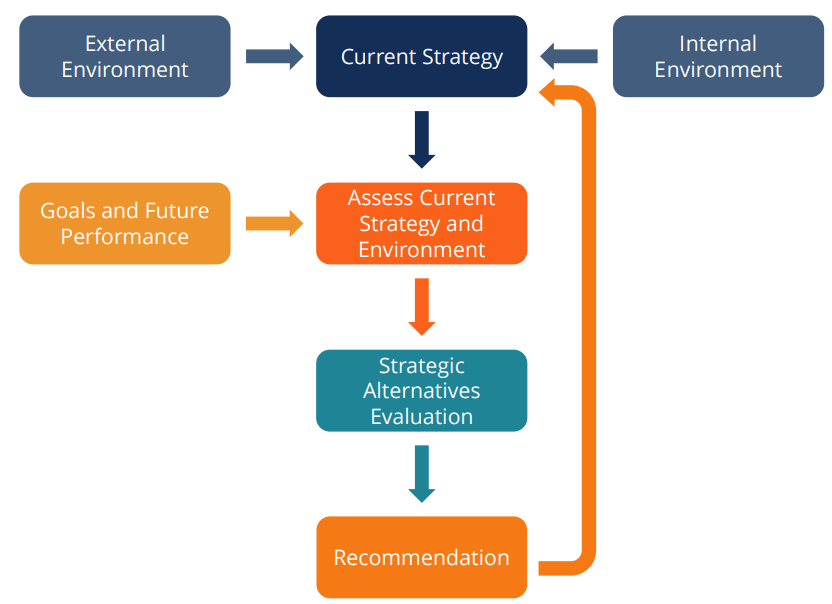

The following infographic demonstrates the strategic analysis process:

1. Perform an environmental analysis of current strategies

Starting from the beginning, a company needs to complete an environmental analysis of its current strategies. Internal environment considerations include issues such as operational inefficiencies, employee morale, and constraints from financial issues. External environment considerations include political trends, economic shifts, and changes in consumer tastes.

2. Determine the effectiveness of existing strategies

A key purpose of a strategic analysis is to determine the effectiveness of the current strategy amid the prevailing business environment. Strategists must ask themselves questions such as: Is our strategy failing or succeeding? Will we meet our stated goals? Does our strategy align with our vision, mission, and values?

3. Formulate plans

If the answer to the questions posed in the assessment stage is “No” or “Unsure,” we undergo a planning stage where the company proposes strategic alternatives. Strategists may propose ways to keep costs low and operations leaner. Potential strategic alternatives include changes in capital structure, changes in supply chain management, or any other alternative to a business process.

4. Recommend and implement the most viable strategy

Lastly, after assessing strategies and proposing alternatives, we reach a recommendation. After assessing all possible strategic alternatives, we choose to implement the most viable and quantitatively profitable strategy. After producing a recommendation, we iteratively repeat the entire process. Strategies must be implemented, assessed, and re-assessed. They must change because business environments are not static.

Levels of Strategy

Strategic plans involve three levels in terms of scope:

1. Corporate-level (Portfolio)

At the highest level, corporate strategy involves high-level strategic decisions that will help a company sustain a competitive advantage and remain profitable in the foreseeable future. Corporate-level decisions are all-encompassing of a company.

2. Business-level

At the median level of strategy are business-level decisions. The business-level strategy focuses on market position to help the company gain a competitive advantage in its own industry or other industries.

3. Functional-level

At the lowest level are functional-level decisions. They focus on activities within and between different functions, aimed at improving the efficiency of the overall business. These strategies are focused on particular functions and groups.

Related Readings

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide to Strategic Analysis. To keep learning and advancing your career, the following CFI resources will be helpful:

- Business Life Cycle

- Competitive Advantage

- Industry Analysis

- Types of Financial Analysis

- See all management & strategy resources

- Share this article

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

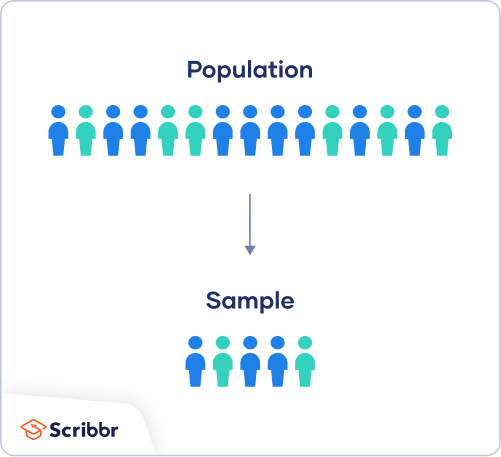

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

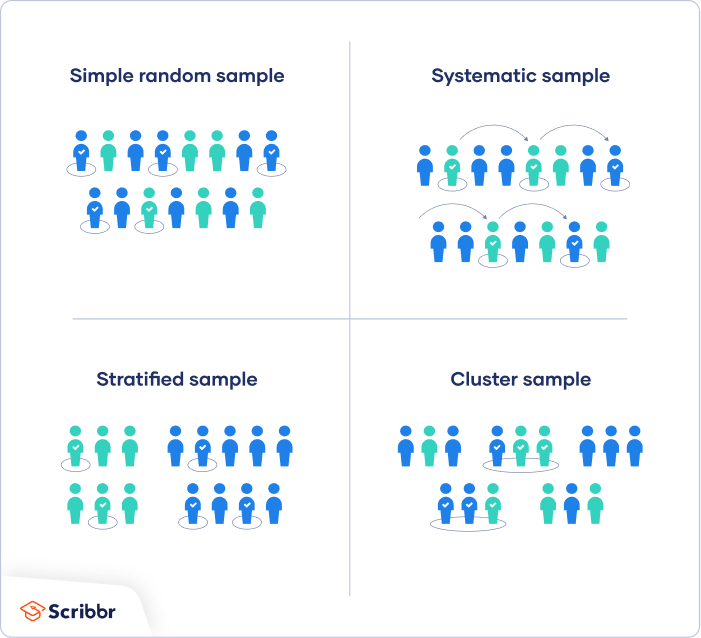

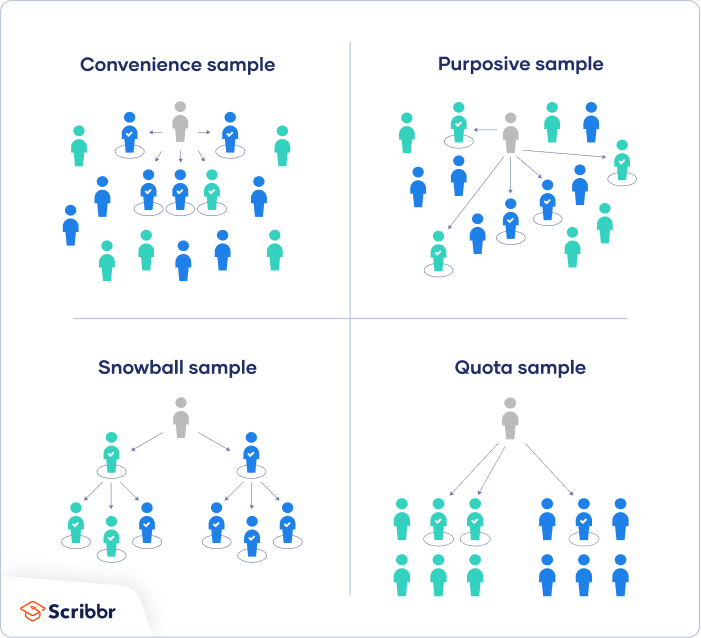

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

| Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

| Approach | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | |

| Discourse analysis |

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Research Strategies and Methods

- First Online: 22 July 2021

Cite this chapter

- Paul Johannesson 3 &

- Erik Perjons 3

3129 Accesses

Researchers have since centuries used research methods to support the creation of reliable knowledge based on empirical evidence and logical arguments. This chapter offers an overview of established research strategies and methods with a focus on empirical research in the social sciences. We discuss research strategies, such as experiment, survey, case study, ethnography, grounded theory, action research, and phenomenology. Research methods for data collection are also described, including questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, observations, and documents. Qualitative and quantitative methods for data analysis are discussed. Finally, the use of research strategies and methods within design science is investigated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bhattacherjee A (2012) Social science research: principles, methods, and practices, 2 edn. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Tampa, FL

Google Scholar

Blake W (2012) Delphi complete works of William Blake, 2nd edn. Delphi Classics

Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B (2004) Asking questions: the definitive guide to questionnaire design – for market research, political polls, and social and health questionnaires, revised edition. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Bryman A (2016) Social research methods, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Charmaz K (2014) Constructing grounded theory, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Coghlan D (2019) Doing action research in your own organization, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

MATH Google Scholar

Denscombe M (2017) The good research guide, 6th edn. Open University Press, London

Dey I (2003) Qualitative data analysis: a user friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge, London

Book Google Scholar

Fairclough N (2013) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language, 2 edn. Routledge, London

Field A, Hole GJ (2003) How to design and report experiments, 1st edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Fowler FJ (2013) Survey research methods, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Glaser B, Strauss A (1999) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, London

Kemmis S, McTaggart R, Nixon R (2016) The action research planner: doing critical participatory action research, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin

Krippendorff K (2018) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 4th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ (2010) Designing and conducting ethnographic research: an introduction, 2nd edn. AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD

McNiff J (2013) Action research: principles and practice, 3rd edn. Routledge, London

Oates BJ (2006) Researching information systems and computing. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Peterson RA (2000) Constructing effective questionnaires. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Prior L (2008) Repositioning documents in social research. Sociology 42(5):821–836

Article Google Scholar

Seidman I (2019) Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and the social sciences, 5th edn. Teachers College Press, New York

Silverman D (2018) Doing qualitative research, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Stephens L (2004) Advanced statistics demystified, 1st edn. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York

Urdan TC (2016) Statistics in plain English, 4th ed. Routledge, London

Yin RK (2017) Case study research and applications: design and methods, 6th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm University, Kista, Sweden

Paul Johannesson & Erik Perjons

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Johannesson, P., Perjons, E. (2021). Research Strategies and Methods. In: An Introduction to Design Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78132-3_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78132-3_3

Published : 22 July 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-78131-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-78132-3

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Main navigation

- Meet the Vice-President

- Meet the Executive Team

- Research Advisory Council

- Office of the Vice-President

- Office of Sponsored Research

- Innovation + Partnerships

- Ethics and Compliance

- Research Security and Compliance

- Research Integrity Office

- Mission and Vision

Strategic Research Plan

- Annual Report

- Research Administration Network (RAN)

- McGill Affiliated Hospitals

- Research Units

- McGill Research Chairs

- Research Funding

- Funding Opportunities Database

- Applications and Proposals

- Forms and Resources

- Research Funding Checklist

- Award Management and Reporting

- Contracts and Agreements

- Policies, Regulations, and Guidelines

- Research Involving Animals

- Standard Operating Procedures (Animals)

- Research Involving Humans (REB)

- Regulations and Safety

- Technology Transfer

- Working with Industry

- Protecting and Commercializing IP

- Equity, Diversity and Integrity

- Research Security

- Digital Research Services

- Prizes and Awards

- Special Features

- Workshops and Events

For close to two centuries, McGill University has attracted some of the world’s brightest researchers and young minds. Today, McGill remains dedicated to the transformative power of ideas and research excellence as judged by the highest international standards. The Strategic Research Plan (SRP) expresses McGill’s commitments to fostering creativity; promoting innovation; problem-solving through collaboration and partnership; promoting equity, diversity and inclusion; and serving society through seven identified Thematic Areas of Research Excellence.

Research Excellence Themes

The seven Research Excellence Themes group McGill researchers into broad areas of strategic importance. Together the themes will be used as a roadmap for setting institutional-level objectives and supporting both disciplinary and interdisciplinary research. Our classification is designed to help generate and reinforce novel linkages that address issues of local, regional, and global importance.

The Research Excellence Themes are, by necessity, broad ways of grouping areas of strength and strategic importance and so our researchers have written a few emblematic examples of research areas that fit within the themes. These examples are by no means exhaustive - they are intended to allow the reader insight into some of McGill's varied research endeavours within the themes. Click on the images or text below to explore the seven Research Excellence Themes.

1. Develop knowledge of the foundations, applications, and impacts of technology in the Digital Age

The Unique Character of McGill

McGill's researchers are known around the world for their discoveries and innovations. Learn more about McGill's vision, commitments, and objectives for sustained research excellence in the Strategic Research Plan (SRP) . McGill is a large, diverse institution with research activities spanning two campuses, 10 Faculties, multiple hospitals, research centres and institutes. It is home to more than 1,700 tenured or tenure-track faculty members. Defining Research Excellence Themes that cut across these entities is a difficult but necessary challenge to promote areas of collaboration with partners, attract people and resources, and envision a research future emerging from existing strengths. To that end, we have identified seven Research Excellence Themes.

The SRP lays the groundwork for McGill to reach into the future by enhancing its research capabilities, building and strengthening its strategic relationships, and growing its societal impact through knowledge mobilization beyond academia. The SRP also aims to promote exciting and creative responses to new challenges and opportunities as the research landscape and the social, cultural, economic, and technological realities of our world change.

Image: In the lab of Professor Tomislav Friščić (Normand Blouin)

Our vision, goals and culture

McGill is a world-class research-intensive, student-centred university with an enduring sense of public purpose. We are guided by our mission to carry out research and scholarly activities that are judged to be excellent by the highest international standards. Our researchers ask important questions and contribute within and across disciplines to address the most pressing and complex challenges facing humanity and the natural environment in the 21st century.

Fundamental to realizing this vision is the expansion of a culture that nurtures and facilitates research excellence, enabling faculty and student researchers to explore rich intellectual pursuits, respond to new global realities and co-create knowledge with partners that will have impacts at local, national, and global scales.

This Strategic Research Plan (SRP) expresses McGill’s core commitments to research, identifies ongoing Research Excellence Themes, and outlines our implementation strategy and objectives over the next five years.

Image: The McGill Space Institute (Olivier Blouin)

Achieving Our Goals

McGill has a strong history of achievement, consistently ranking as one of the top universities in the world across a wide range of disciplines and subject areas. We are renowned for attracting some of the brightest researchers and young thinkers, who contribute immensely to the advancement of knowledge.

This SRP reaffirms our dedication to the transformative power of ideas and research excellence. To these ends, we commit to:

- Fostering creativity

- Promoting innovation

- Problem solving through collaboration and partnership

- Promoting equity, diversity and inclusion

- Serving society