Reported Speech – Free Exercise

Write the following sentences in indirect speech. Pay attention to backshift and the changes to pronouns, time, and place.

- Two weeks ago, he said, “I visited this museum last week.” → Two weeks ago, he said that . I → he simple past → past perfect this → that last …→ the … before

- She claimed, “I am the best for this job.” → She claimed that . I → she simple present→ simple past this→ that

- Last year, the minister said, “The crisis will be overcome next year.” → Last year, the minister said that . will → would next …→ the following …

- My riding teacher said, “Nobody has ever fallen off a horse here.” → My riding teacher said that . present perfect → past perfect here→ there

- Last month, the boss explained, “None of my co-workers has to work overtime now.” → Last month, the boss explained that . my → his/her simple present→ simple past now→ then

Rewrite the question sentences in indirect speech.

- She asked, “What did he say?” → She asked . The subject comes directly after the question word. simple past → past perfect

- He asked her, “Do you want to dance?” → He asked her . The subject comes directly after whether/if you → she simple present → simple past

- I asked him, “How old are you?” → I asked him . The subject comes directly after the question word + the corresponding adjective (how old) you→ he simple present → simple past

- The tourists asked me, “Can you show us the way?” → The tourists asked me . The subject comes directly after whether/if you→ I us→ them

- The shop assistant asked the woman, “Which jacket have you already tried on?” → The shop assistant asked the woman . The subject comes directly after the question word you→ she present perfect → past perfect

Rewrite the demands/requests in indirect speech.

- The passenger requested the taxi driver, “Stop the car.” → The passenger requested the taxi driver . to + same wording as in direct speech

- The mother told her son, “Don’t be so loud.” → The mother told her son . not to + same wording as in direct speech, but remove don’t

- The policeman told us, “Please keep moving.” → The policeman told us . to + same wording as in direct speech ( please can be left off)

- She told me, “Don’t worry.” → She told me . not to + same wording as in direct speech, but remove don’t

- The zookeeper told the children, “Don’t feed the animals.” → The zookeeper told the children . not to + same wording as in direct speech, but remove don’t

How good is your English?

Find out with Lingolia’s free grammar test

Take the test!

Maybe later

Reported Speech Quiz

Test your understanding of Reported Speech in English with this Reported Speech Quiz. Reported Speech, also known as indirect speech, is used to convey what someone else said without quoting their exact words. It often involves changes in tense, pronouns, and time expressions to suit the reporting context. For example, direct speech: “ I am learning English, ” becomes in reported speech: “ She said she was learning English. ” This quiz has 15 questions and each question will ask you to change the direct speech into reported speech. Take The Quiz Below!

Not learned about reported speech yet? Then check out this Reported Speech Guide which includes lots of examples to help you master this important part of English grammar.

Home » English Grammar Tests » Advanced English Grammar Tests » Reported Speech Test Exercises – Multiple Choice Questions With Answers – Advanced Level 32

Reported Speech Test Exercises – Multiple Choice Questions With Answers – Advanced Level 32

This exercise is an advanced level multiple choice test with multiple choice questions on reported speech (indirect speech) including the topics below.

Reported Speech (Indirect Speech)

- Reporting Statements

- Reporting Questions

- Reporting Imperatives

- Reporting Modals

- Reporting Conditionals, Exclamations

- Reported Speech Mixed Type

Reported Speech Test Exercises - Multiple Choice Questions With Answers - Advanced Level 32

"I'm going to Istanbul tomorrow," he said.

He said ____ going to Istanbul ____.

"I'll give you half of the money if you keep your mouth shut," he said to me.

He ____ mouth shut.

"I am sorry I am late," he said "My car broke down."

He ____ and ____.

He ____ so often in Turkey.

"How far is it?" he said "and how long will it take me to get there?"

He ____ to get there.

"Climb up the tree," he said to me.

He ____ the tree.

The teacher ____ in the exam.

He wanted me to explain ____.

He warned me ____ anyone about the subject we ____ the day before.

"Come in and look round. We do not charge anything for looking," said the shopkeeper. The shopkeeper ____ us to come in and look around ____ us that he didn't require any amount for looking.

"I'll drop you from the team if you don't train harder," said the trainer. The trainer ____ to drop us from the team if we ____ harder.

We ____ all ____ that the meeting would begin in an hour.

"You have been leaking information to the journalists!" said the minister. "No, I haven't," said John. The minister ____ leaking information but John ____ it.

"I won't answer any questions," said the thief. The thief ____ to answer any questions.

"You pressed the wrong button," said the engineer "Don't do it again".

The engineer ____ that I had pressed the wrong button and he ____ it again.

"Yippee! I've passed the final exam," he exclaimed. "Congratulations! " I said.

He ____ that he had passed the final exam and I ____ him.

"Cigarette?" he said. "No, thanks," I said.

He ____ me a cigarette but I ____.

"You have gained weight!" I said. "I am afraid I have," he replied sadly.

I noted that he ____ weight and he admitted that he ____.

He said his car ____.

"I will inform her that I saw you". She said that she ____ her that she ____ me.

They are getting married next week.

She said that they ____.

She said that her dog ____.

"Do you want a cup of coffee?"

He ____ me a cup of coffee.

"Can you lend me some money until next week?"

He ____ some money from me.

"I must confess that I ate the cake last night."

She ____ that she had eaten the cake.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| End |

Download PDF version of this test.

Previous Posts

We welcome your comments, questions, corrections, reporting typos and additional information relating to this content.

Reported Speech Quiz

You can do this grammar quiz online or print it on paper. It tests what you learned on the Reported Speech pages.

1. Which is a reporting verb?

2. He said that it was cold outside. Which word is optional?

3. "I bought a car last week." Last week he said he had bought a car

4. "Where is it?" said Mary. She

5. Which of these is usually required with reported YES/NO questions?

6. Ram asked me where I worked. His original words were

7. "Don't yell!" is a

8. "Please wipe your feet." I asked them to wipe

9. She always asks me not to burn the cookies. She always says

10. Which structure is not used for reported orders?

Your score is:

Correct answers:

- Phrases and Clauses

- Parts of a Sentence

- Modal Verbs

- Relative Clauses

- Confusing Words

- Online Grammar Quizzes

- Printable Grammar Worksheets

- Courses to purchase

- Grammar Book

- Grammar Blog

Reported Speech Quiz

In this reported speech quiz you get to practice online turning direct speech into indirect speech.

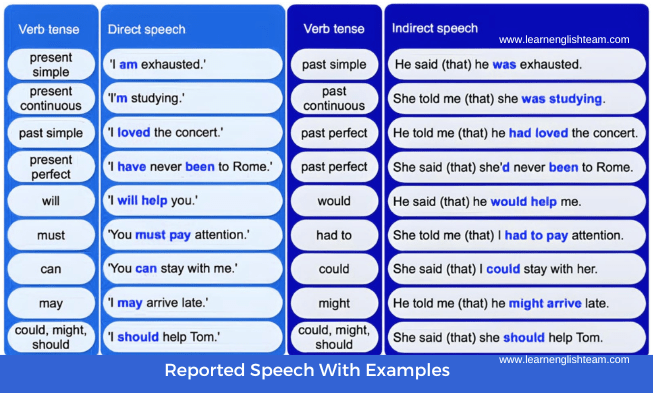

Remember that to turn direct speech to reported speech you need to use backshifting with the tenses. So for example, the present simple turns to the past simple and the past simple turns to the past perfect. Pronouns can also change.

It can be difficult if you are new to it, so if you are unsure of how to do it, before taking the quiz check out the reported speech tense conversion rules .

- John said, "I want to see a film".

- Tina said, "I am tired".

- He said, "Tom hit me very hard".

- I said, "I feel happy".

- She said, "We are learning English".

- Sandra said, "I liked him a lot".

- He said, "We all eat meat".

- Max said, "I will help".

- Gene said, "I must leave early".

- She said, "I had tried everything".

More on Reported Speech:

To vs Too Quiz - Test yourself on the Differences

In this to vs too quiz you can practice online the difference between these words. While to is a preposition used in various ways, too is an adverb.

Types of Adjective Exercise: Multiple Choice

In this types of adjective exercise you need to choose which type the word in capitals represents. It's a multiple choice exercise with answers.

Past Perfect Exercises - Affirmative: Gap Fill

These Past Perfect Exercises focus on the affirmative, interrogative and negative forms. This first quiz is for the affirmative.

Affect Vs Effect Quiz - English Grammar

In this affect vs effect quiz you can test yourself on the difference between these two confusing words. One is a verb whilst the other is a noun.

Modal Verbs Multiple Choice Quiz

In this modal verbs multiple choice quiz, choose which of the three choices of verbs should go into the gap to make a grammatically correct sentence.

Substitution Quiz for English Grammar: Choose the Correct Word

This Substitution Quiz tests your ability to replace words or phrases already used in a sentence with a different word or phrase.

New! Comments

Any questions or comments about the grammar discussed on this page?

Post your comment here.

Sign up for free grammar tips, quizzes and lessons, straight into your inbox

Grammar Rules

Subscribe to grammar wiz:, grammar ebook.

This is an affiliate link

Recent Articles

Gerund or infinitive quiz.

Aug 11, 24 04:34 AM

Use of the Bare Infinitive

Aug 09, 24 01:59 AM

Future Continuous Tense Quiz: Yes/No Questions

Jun 29, 24 11:04 AM

Important Pages

Online Quizzes Grammar Lessons Courses Blog

Connect with Us

Search Site

Privacy Policy / Disclaimer / Terms of Use

Reported Speech Exercise 1

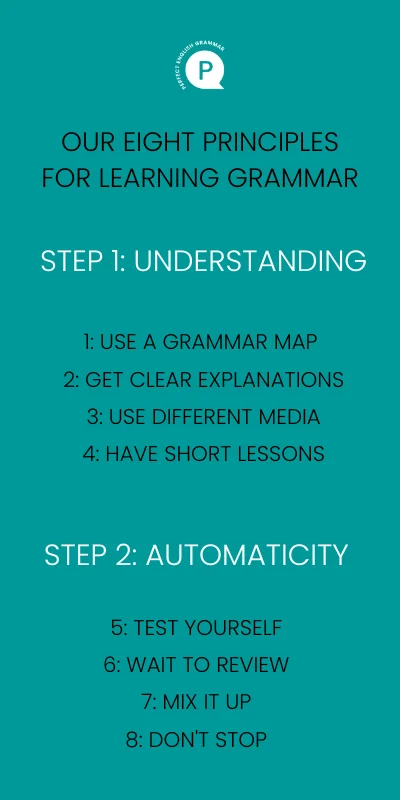

Perfect english grammar.

Here's an exercise about reported statements.

- Review reported statements here

- Download this quiz in PDF here

- More reported speech exercises here

Hello! I'm Seonaid! I'm here to help you understand grammar and speak correct, fluent English.

Read more about our learning method

English Grammar Online Exercises and Downloadable Worksheets

Online exercises.

- Reported Speech

Levels of Difficulty : Elementary Intermediate Advanced

- RS012 - Reported Speech Intermediate

- RS011 - Reported Speech Intermediate

- RS010 - Reporting Verbs Advanced

- RS009 - Reporting Verbs Advanced

- RS008 - Reporting Verbs Advanced

- RS007 - Reporting Verbs Intermediate

- RS006 - Reported Speech Intermediate

- RS005 - Reported Speech - Introductory Verbs Advanced

- RS004 - Reported Speech Intermediate

- RS003 - Reporting Verbs Intermediate

- RS002 - Reported Speech Intermediate

- RS001 - Reported Speech Intermediate

- Gerund - Infinitive

- Adjective - Adverb

- Modal Verbs

- Passive Voice

- Definite and Indefinite Articles

- Prepositions

- Connectives and Linking Words

- Quantifiers

- Question and Negations

- Relative Pronouns

- Indefinite Pronouns

- Possessive Pronouns

- Phrasal Verbs

- Common Mistakes

- Missing Word Cloze

- Word Formation

- Multiple Choice Cloze

- Prefixes and Suffixes

- Key Word Transformation

- Editing - One Word Too Many

- Collocations

- General Vocabulary

- Adjectives - Adverbs

- Gerund and Infinitive

- Conjunctions and Linking Words

- Question and Negation

- Error Analysis

- Translation Sentences

- Multiple Choice

- Banked Gap Fill

- Open Gap Fill

- General Vocabulary Exercises

- Argumentative Essays

- Letters and Emails

- English News Articles

- Privacy Policy

Reported Speech Exercises (With Printable PDF)

| Candace Osmond

| Grammar , Quizzes

Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond studied Advanced Writing & Editing Essentials at MHC. She’s been an International and USA TODAY Bestselling Author for over a decade. And she’s worked as an Editor for several mid-sized publications. Candace has a keen eye for content editing and a high degree of expertise in Fiction.

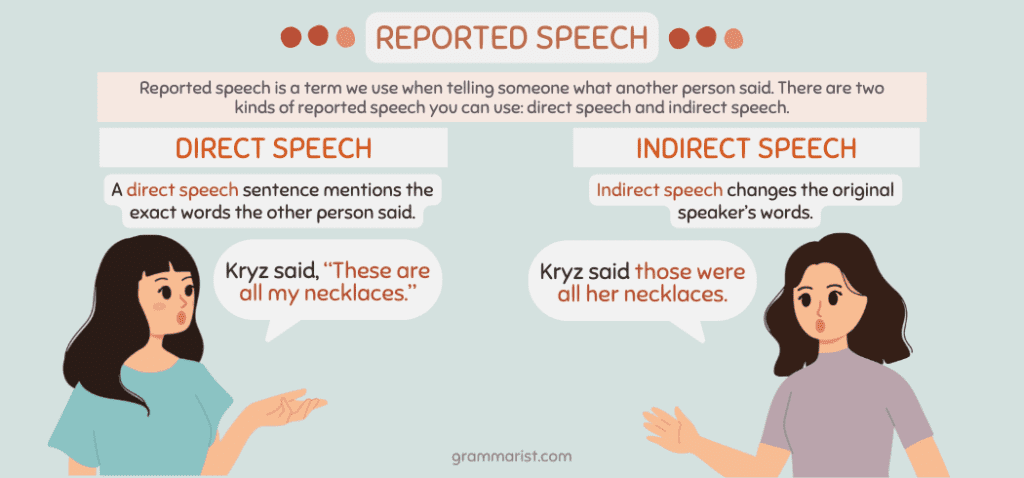

In English grammar, reported speech is used to tell someone what another person said. It takes another person’s words (direct speech) to create a report of what they said (indirect speech.) With the following direct and indirect speech exercises, it will be easier to understand how reported speech works.

Reported Speech Exercise #1

Complete the sentence in the reported speech.

Reported Speech Exercise #2

Fill in the gaps below with the correct pronouns required in reported speech. Ex. Mary said: “I love my new dress!” Sentence: Mary said ____ love ____ new dress. Answer: she, her

Reported Speech Exercise #3

Choose the correct reported speech phrase to fill in the sentences below.

Grammarist is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. When you buy via the links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you.

2024 © Grammarist, a Found First Marketing company. All rights reserved.

Exercise on Reported Speech

Mixed exercise 1.

Complete the sentences in reported speech. Note whether the sentence is a request, a statement or a question.

- He said, "I like this song." → He said

- "Where is your sister?" she asked me. → She asked me

- "I don't speak Italian," she said. → She said

- "Say hello to Jim," they said. → They asked me

- "The film began at seven o'clock," he said. → He said

- "Don't play on the grass, boys," she said. → She told the boys

- "Where have you spent your money?" she asked him. → She asked him

- "I never make mistakes," he said. → He said

- "Does she know Robert?" he wanted to know. → He wanted to know

- "Don't try this at home," the stuntman told the audience. → The stuntman advised the audience

| |

Reported Speech, Indirect Speech – English Grammar Exercises

- You are here:

- Grammar Exercises

Reported speech Multiple choice quiz

- English grammar PDF

- PDF worksheets

- Mixed PDF tests

- Present tenses

- Past tenses

- Future tenses

- Present perfect

- Past perfect

- Future perfect

- Irregular verbs

- Modal verbs

- If-conditional

- Passive voice

- Reported speech

- Time clauses

- Relative clauses

- Indirect questions

- Question tags

- Imperative sentence

- Gerund and infinitive

- Direct | indirect object

Reported speech mcq - exercise 4

Choose the correct endings in the multiple choice test on reported speech (special cases).

"I am reading an interesting book," he told me. He told me that ___ an interesting book. (he's been reading, he was reading)

Check test Answer key Clear test

| "I am waiting at the bus stop number ten," he told me. He told me that at the bus stop number ten. |

| "We will set off tomorrow," they said on Friday. On Friday they said . |

| "Get out of my way!" he ordered us. He ordered us of his way. |

| "I invited Derek to dinner last week," Debbie told me this week. Debbie told me this week that she had invited Derek to dinner . |

| "I will resign today," the minister announced this morning. This morning the minister announced that he would resign . |

| "She'd better refuse this job," insisted my father. My father insisted that she that job. |

| "We used to take the same medicine," she thought. She thought that the same medicine. |

| "It is time we had an agreement," the vice president suggested. The vice president suggested that it was time we an agreement. |

| "We must go skiing to the Alps in winter," he said. He said that they skiing to the Alps in winter. |

| "I wouldn't go to South America if I were you," Betty claimed. Betty claimed she wouldn't go to South America if she me. |

| "I caught a cold while I was waiting at the bus stop," Daniel told us. Daniel told us that he caught a cold while he at the bus stop. |

| "He has fallen in love with Julie," Sam told me about William. Sam told me that in love with Julie. |

Reported speech multiple choice exercises and gap-filling + grammar rules.

For intermediate and advanced learners of English.

Reported Speech with Examples and Test (PDF)

Reported speech is used when we want to convey what someone else has said to us or to another person. It involves paraphrasing or summarising what has been said , often changing verb tenses , pronouns and other elements to suit the context of the report.

| Tense | Direct Speech | Reported Speech |

|---|---|---|

| Present Simple | She sings in the choir. | He said (that) she sings in the choir. |

| Present Continuous | They are playing football. | She mentioned (that) they were playing football. |

| Past Simple | I visited Paris last summer. | She told me (that) she visited Paris last summer. |

| Past Continuous | I was cooking dinner. | He said (that) he had been cooking dinner. |

| Present Perfect | We have finished the project. | They said (that) they had finished the project. |

| Past Perfect* | I had already eaten when you called. | She explained (that) she had already eaten when I called. |

| Will | I will call you later. | She promised (that) she would call me later. |

| Would* | I would help if I could. | He said (that) he would help if he could. |

| Can | She can speak French fluently. | He mentioned (that) she could speak French fluently. |

| Could* | I could run fast when I was young. | She recalled (that) she could run fast when she was young. |

| Shall | Shall we meet tomorrow? | They asked (whether) we should meet the next day. |

| Should* | You should visit the museum. | She suggested (that) I should visit the museum. |

| Might* | It might rain later. | He mentioned (that) it might rain later. |

| Must | I must finish my homework. | She reminded me (that) I must finish my homework. |

*doesn’t change

Formula of Reported Speech

The formula for reported speech involves transforming direct speech into an indirect form while maintaining the meaning of the original statement. In general, the formula includes:

- Choosing an appropriate reporting verb (e.g., say, tell, mention, explain).

- Changing pronouns and time expressions if necessary.

- Shifting the tense of the verb back if the reporting verb is in the past tense.

- Using reporting clauses like “that” or appropriate conjunctions.

- Adjusting word order and punctuation to fit the structure of the reported speech.

Here’s a simplified formula:

Reporting Verb + Indirect Object + Conjunction + Reported Clause

For example:

- She said (reporting verb) to me (indirect object) that (conjunction) she liked ice cream (reported clause).

Here’s how we use reported speech:

Reporting Verbs: We use verbs like ‘say’ or ‘tell’ to introduce reported speech. If the reporting verb is in the present tense, the tense of the reported speech generally remains the same.

| Direct Speech | Reported Speech |

|---|---|

| “I enjoy playing tennis.” | She said (that) she enjoys playing tennis. |

| “We plan to visit Paris.” | They told us (that) they plan to visit Paris. |

| “He loves listening to music.” | She said (that) he loves listening to music. |

| “She bakes delicious cakes.” | He told me (that) she bakes delicious cakes. |

| “They watch movies every weekend.” | She said (that) they watch movies every weekend. |

If the reporting verb is in the past tense , the tense of the reported speech often shifts back in time.

| Direct Speech | Reported Speech (Reporting verb in past tense) |

|---|---|

| “I eat breakfast at 8 AM.” | She said (that) she ate breakfast at 8 AM. |

| “We are going to the beach.” | They told me (that) they were going to the beach. |

| “He speaks Spanish fluently.” | She said (that) he spoke Spanish fluently. |

| “She cooks delicious meals.” | He mentioned (that) she cooked delicious meals. |

| “They play soccer every weekend.” | She said (that) they played soccer every weekend. |

Tense Changes: Tense changes are common in reported speech. For example, present simple may change to past simple, present continuous to past continuous, etc. However, some verbs like ‘would’, ‘could’, ‘should’, ‘might’, ‘must’, and ‘ought to’ generally don’t change.

| Direct Speech | Reported Speech |

|---|---|

| “I like chocolate.” | She said (that) she liked chocolate. |

| “We are watching TV.” | They told me (that) they were watching TV. |

| “He is studying for the exam.” | She mentioned (that) he was studying for the exam. |

| “She has finished her work.” | He said (that) she had finished her work. |

| “They will arrive soon.” | She mentioned (that) they would arrive soon. |

| “You can swim very well.” | He said (that) I could swim very well. |

| “She might be late.” | He mentioned (that) she might be late. |

| “I must finish this by tonight.” | She said (that) she must finish that by tonight. |

| “You should call your parents.” | They told me (that) I should call my parents. |

| “He would help if he could.” | She said (that) he would help if he could. |

Reported Questions: When reporting questions, we often change them into statements while preserving the meaning. Question words are retained, and the tense of the verbs may change.

| Direct Question | Reported Statement (Preserving Meaning) |

|---|---|

| “Where do you live?” | She asked me where I lived. |

| “What are you doing?” | They wanted to know what I was doing. |

| “Who was that fantastic man?” | He asked me who that fantastic man had been. |

| “Did you turn off the coffee pot?” | She asked if I had turned off the coffee pot. |

| “Is supper ready?” | They wanted to know if supper was ready. |

| “Will you be at the party?” | She asked me if I would be at the party. |

| “Should I tell her the news?” | He wondered whether he should tell her the news. |

| “Where will you stay?” | She inquired if I had decided where I would stay. |

Reported Requests and Orders: Requests and orders are reported similarly to statements. Reported requests often use ‘asked me to’ + infinitive, while reported orders use ‘told me to’ + infinitive.

| Direct Request/Order | Reported Speech |

|---|---|

| “Please help me.” | She asked me to help her. |

| “Please don’t smoke.” | He asked me not to smoke. |

| “Could you bring my book tonight?” | She asked me to bring her book that night. |

| “Could you pass the milk, please?” | He asked me to pass the milk. |

| “Would you mind coming early tomorrow?” | She asked me to come early the next day. |

| “Please don’t be late.” | He told me not to be late. |

| “Go to bed!” | She told the child to go to bed. |

| “Don’t worry!” | He told her not to worry. |

| “Be on time!” | He told me to be on time. |

| “Don’t smoke!” | He told us not to smoke. |

Time Expressions: Time expressions may need to change depending on when the reported speech occurred in relation to the reporting moment. For instance, ‘today’ may become ‘that day’ or ‘yesterday’, ‘yesterday’ might become ‘the day before’, and so forth.

| Direct Speech | Reported Speech |

|---|---|

| “I finished my homework.” | She said she had finished her homework. |

| “We are going shopping.” | He told me they were going shopping. |

| “She will call you later.” | They mentioned she would call me later. |

| “I saw him yesterday.” | She said she had seen him the day before. |

| “The party is tonight.” | He mentioned the party would be that night. |

| “The concert was last week.” | She told me the concert had been the previous week. |

Reported Speech with Examples PDF

Reported Speech PDF – download

Reported Speech Test

Reported Speech A2 – B1 Test – download

You May Also Like

British and American English Vocabulary Differences (PDF)

How to Find the Best Online Essay Writer – Guide

Data Science vs. Machine Learning: What’s the Difference?

- I would like books for studying.

Reported speech - 1

Reported speech - 2

Reported speech - 3

Worksheets - handouts

Exercises: indirect speech

- Reported speech - present

- Reported speech - past

- Reported speech - questions

- Reported questions - write

- Reported speech - imperatives

- Reported speech - modals

- Indirect speech - tenses 1

- Indirect speech - tenses 2

- Indirect speech - write 1

- Indirect speech - write 2

- Indirect speech - quiz

- Reported speech - tenses

- Indirect speech – reported speech

- Reported speech – indirect speech

Direct And Indirect Speech Quiz: Test Your Skills

Are you eager to assess your English grammar proficiency in an enjoyable manner? Dive into this Direct and Indirect Speech Quiz to gauge your knowledge of these two forms of reported speech. Reporting speech involves conveying someone else's words, and it can be done in two primary ways: direct and indirect speech. In direct speech, you repeat the speaker's words verbatim. In contrast, indirect speech conveys the speaker's message without using their exact words. This quiz presents an engaging opportunity to test your understanding of these concepts and improve your grammatical skills. By participating in this quiz, you Read more can enhance your grasp of the nuances between direct and indirect speech, which is essential for effective communication and writing. So, are you ready for the challenge? Let's embark on this educational journey and see how well you can navigate the intricacies of reported speech. Best of luck!

Direct And Indirect Speech Questions and Answers

What would the indirect speech be: maria said, "it's my car.".

Maria said that it is my car.

Maria said that it is her car.

Maria said that it was my car.

Maria said that it was her car.

Rate this question:

What would the indirect speech be: Martin said, "I work here every day."?

Martin said that he worked here yesterday.

Martin said that he worked there every day.

Martin said that he works here every day.

Martin said that he worked every day.

What would the indirect speech be: Monica said, "I have finished my homework."?

Monica said that she had finished her homework.

Monica said that she had finished my homework.

Monica said that she has finished her homework.

Monica said that she has finished my homework."

What would the indirect speech be: My daughter said to me, "I can sleep alone."?

My daughter said to me that I can sleep alone.

My daughter told me that she can sleep alone.

My daughter said to me that she would sleep alone.

My daughter told me that she could sleep alone.

What would the indirect speech be: Leo said, "My friend may come tonight."?

Leo said that his friend might come tonight.

Leo said that his friend might come that night.

Leo said that his friend might go that night.

Leo said that his friend might go tonight.

What would the indirect speech be: Jullie said to me, "I have to win this game."?

Jullie told me that she must win this game.

Jullie told me that she had to win that game.

Jullie told me that she had to win this game.

Jullie told me that she must win that game.

What would the indirect speech be: He said, "I am a man."?

He said that he was a man.

He said that he is a man.

He said that I am a man.

He said that I was a man.

What would the indirect speech be: Mary said, "I am coming here."?

Mary said that she was coming there.

Mary said that she is coming there.

Mary insists that she had been coming there.

Mary says that she had come here.

What would the indirect speech be: My brother said, "I went to school yesterday."?

My brother said that he had gone to school today.

My brother said that he had gone to school the day after.

My brother said that he had gone to school the previous day.

My brother said that he had gone to school the next day.

What would the indirect speech be: Mathew said, "I will go to school next year."?

Mathew said that he would go to school the year before.

Mathew said that he would go to school the following year.

Mathew said that he would come to school the year before.

Mathew said that he would come to school the year after.

Quiz Review Timeline +

Our quizzes are rigorously reviewed, monitored and continuously updated by our expert board to maintain accuracy, relevance, and timeliness.

- Current Version

- Aug 22, 2024 Quiz Edited by ProProfs Editorial Team

- May 13, 2015 Quiz Created by Tukkatan64

Related Topics

- Preposition

- Figurative Language

Recent Quizzes

Featured Quizzes

Popular Topics

- Abbreviation Quizzes

- Citation Quizzes

- Linguistics Quizzes

- Phonetics Quizzes

- Poem Quizzes

- Quote Quizzes

- Vocabulary Quizzes

Related Quizzes

Wait! Here's an interesting quiz for you.

https://first-english.org

Reported speech - indirect speech

- English year 1

- English year 2

- English year 3

- English year 4

- You are learning...

- Reported Speech

- 01 Reported Speech rules

- 02 Pronouns change

- 03 Pronouns change

- 04 Change place and time

- 05 Simple Present

- 06 Introduction Simple Pres.

- 07 Backshift

- 08 Backshift Tenses

- 09 Simple Past negative

- 10 Simple Past negative

- 11 Questions

- 12 Questions

- 13 Past - Past Perfect

- 14 Past - Past Perfect

- 15 Past Perfect negative

- 16 Past Perfect negative

- 17 with-out question word

- 18 with-out question word

- 19 Perfect Past Perfect

- 20 Perfect - Past Perfect

- 21 Perfect - Past Perfect

- 22 Perfect - Past Perfect

- 23 Questions without qw.

- 24 Questions with qw.

- 25 will - would

- 26 Will-Future

- 27 Will-Future negative

- 28 Will-Future negatives

- 29 Will-Future Questions

- 30 Will-Future will - would

- 31 Commands

- 32 Commands Reported

- 33 Commands negative

- 34 Commands negative

- 35 Mixed exercises

- 37 Questions all tenses

- 38 Questions all tenses

- 39 Commands all tenses

- 40 Commands all tenses

- 41 all forms all tenses

- 42 all forms all tenses

- 43 Change place and time

- 44 Change place and time

- 45 Test Reported Speech

- English Tenses

- Simple Present Tense

- Simple past Tense

- Present perfect

- Past Perfect

- Simple Future

- Future Perfect

- Going-to-Future

- Continuous Tenses

- Present Continuous

- Past Continuous

- Present perfect Progr.

- Past Perfect Continuous

- Simple Future Continuous

- Future 2 Continuous

- Comparison of Tenses

- Passive exercises

- If clauses - Conditional

Test reported speech

When you report someones words you can do it in 2 ways:

Direct speech

1. You can use direct speech with quotation marks. Example: He said: I work in a bank.

Reported speech

2. You can use reported speech. Example: He said he worked in a bank. The tenses, word-order, pronouns may be different from those in the direct speech sentence.

English Reported speech exercises

Reported speech - indirect speech with free online exercises, Reported speech - indirect speech examples and sentences. Online exercises Reported speech - indirect speech, questions and negative sentences.

Online exercises English grammar and courses Free tutorial Reported speech - indirect speech with exercises. English grammar easy to learn.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- College football

- Auto Racing

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

RFK Jr. suspends his presidential bid and backs Donald Trump before appearing with him at his rally

Robert F. Kennedy said Friday he is suspending his independent presidential bid and is backing Donald Trump. Kennedy said his internal polls had showed that his presence in the race would hurt Trump and help Democratic nominee Kamala Harris.

- Copy Link copied

▶ Follow the AP’s live coverage and analysis from the 2024 Democratic National Convention.

PHOENIX (AP) — Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suspended his independent campaign for the White House and endorsed Donald Trump on Friday, a late-stage shakeup of the race that could give the former president a modest boost from Kennedy’s supporters.

Hours later, Kennedy joined Trump onstage at an Arizona rally, where the crowd burst into “Bobby!” cheers.

Kennedy said his internal polls had shown that his presence in the race would hurt Trump and help Democratic nominee Kamala Harris, though recent public polls don’t provide a clear indication that he is having an outsize impact on support for either major-party candidate.

Kennedy cited free speech, the war in Ukraine and “a war on our children” as among the reasons he would try to remove his name from the ballot in battleground states.

“These are the principal causes that persuaded me to leave the Democratic Party and run as an independent, and now to throw my support to President Trump,” Kennedy said at his event in Phoenix.

However, he made clear that he wasn’t formally ending his bid and said his supporters could continue to back him in the majority of states where they are unlikely to sway the outcome. Kennedy took steps to withdraw his candidacy in at least two states late this week, Arizona and Pennsylvania, but election officials in the battlegrounds of Michigan, Nevada and Wisconsin said it would be too late for him to take his name off the ballot even if he wants to do so.

Kennedy said his actions followed conversations with Trump over the past few weeks. He cast their alliance as “a unity party,” an arrangement that would “allow us to disagree publicly and privately and seriously.” Kennedy suggested Trump offered him a job if he returns to the White House, but neither he nor Trump offered details.

Kennedy’s running mate, Nicole Shanahan, this week entertained the idea that Kennedy could join Trump’s administration as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

The announcement ended days of speculation and landed with heaps of confusion and contradictions from Kennedy’s aides and allies, an emblematic cap for a quixotic campaign.

Shortly before his speech in Phoenix, his campaign had said in a Pennsylvania court filing that he would be endorsing Trump for president. However, a spokesperson for Kennedy said the court filing had been made in error and the lawyer who wrote it said he’d correct it. Kennedy took the stage moments later, aired his grievances with the Democratic Party, the news media and political institutions, and extolled Trump. He spoke for nearly 20 minutes before he said explicitly that he was endorsing Trump.

Kennedy later joined Trump onstage at a rally co-hosted by Turning Point Action in Glendale, where Trump’s campaign had teased he would be joined by “a special guest.”

Kennedy was greeted by thundering applause as he took the stage to the Foo Fighters and a pyrotechnics display after being introduced by Trump as “a man who has been an incredible champion for so many of these values that we all share.”

“We are both in this to do what’s right for the country,” Trump said, later commending Kennedy for having “raised critical issues that have been too long ignored in this country.”

What to know about the 2024 Election

- Today’s news: Follow live updates from the campaign trail from the AP.

- Ground Game: Sign up for AP’s weekly politics newsletter to get it in your inbox every Monday.

- AP’s Role: The Associated Press is the most trusted source of information on election night, with a history of accuracy dating to 1848. Learn more.

With Kennedy standing nearby, Trump invoked his slain uncle and father, John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy, saying he knows “that they are looking down right now and they are very, very proud.”

He said that, if he wins this fall, he will establish a new independent presidential commission on assassination attempts that will release all remaining documents related to John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

And he repeated his pledge to establish a panel — “working with Bobby” — to investigate the increase in chronic health conditions and childhood diseases, including autoimmune disorders, autism, obesity and infertility.

A year ago, some would have thought it inconceivable that a member of arguably the most storied family in Democratic politics would work with Trump to keep a Democrat out of the White House. Even in recent months, Kennedy has accused Trump of betraying his followers, while Trump has criticized Kennedy as “the most radical left candidate in the race.”

Five of Kennedy’s family members issued a statement Friday calling his support for Trump “a sad ending to a sad story” and reiterating their support for Harris.

“Our brother Bobby’s decision to endorse Trump today is a betrayal of the values that our father and our family hold most dear,” read the statement, which his sister Kerry Kennedy posted on X .

Kennedy Jr. acknowledged his decision to endorse Trump had caused tension with his family. He is married to actor Cheryl Hines, who wrote on X that she deeply respects her husband’s decision to drop out but did not address the Trump endorsement.

“This decision is agonizing for me because of the difficulties it causes my wife and my children and my friends,” Kennedy said. “But I have the certainty that this is what I’m meant to do. And that certainty gives me internal peace, even in storms.”

In a statement, Harris campaign chair Jen O’Malley Dillon reached out to Kennedy’s supporters who are “tired of Donald Trump and looking for a new way forward” and said that Harris wanted to earn their backing.

At Kennedy’s Phoenix event, 38-year-old Casey Westerman said she trusted Kennedy’s judgment and had planned to vote for him, but would support Trump if Kennedy endorsed him.

“My decision would really be based on who he thinks is best suited to run this country,” said Westerman, who wore a “Kennedy 2024” trucker hat and voted for Trump in the last two presidential elections.

Kennedy first entered the 2024 presidential race as a Democrat but left the party last fall to run as an independent. He built an unusually strong base for a third-party bid, fueled in part by anti-establishment voters and vaccine skeptics who have followed his anti-vaccine work since the COVID-19 pandemic. But he has since faced strained campaign finances and mounting legal challenges.

At Trump’s event in Las Vegas, Alida Roberts, 49, said Kennedy’s endorsement of Trump spoke volumes about the current state of the Democratic Party.

“It says that he doesn’t trust what’s going on, that it’s not the party he grew up in,” Roberts said.

Roberts, who voted twice for Trump, said she was relieved and excited by the endorsement because she’d been “teeter-tottering” between the two candidates.

Recent polls put Kennedy’s support in the mid-single digits, and it’s unclear if he’d get even that in a general election.

There’s some evidence that Kennedy’s staying in the race would hurt Trump more than Harris. According to a July AP-NORC poll, Republicans were significantly more likely than Democrats to have a favorable view of Kennedy. And those with a positive impression of Kennedy were significantly more likely to also have a favorable view of Trump (52%) than Harris (37%).

Associated Press writers Jill Colvin and Ali Swenson in New York, Rio Yamat in Las Vegas, Marc Levy in Harrisburg, Pa., Meg Kinnard in Chicago and Linley Sanders in Washington contributed to this report.

___ The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here . The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2024

Global perspectives on the management of primary progressive aphasia

- Jeanne Gallée 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Jade Cartwright 3 ,

- Stephanie Grasso 4 ,

- Regina Jokel 5 , 6 ,

- Monica Lavoie 7 , 8 ,

- Ellen McGowan 9 ,

- Margaret Pozzebon 10 ,

- Bárbara Costa Beber 11 ,

- Guillaume Duboisdindien 7 , 8 ,

- Núria Montagut 12 , 13 ,

- Monica Norvik 14 ,

- Taiki Sugimoto 1 , 15 ,

- Rosemary Townsend 16 ,

- Nina Unger 17 ,

- Ingvild E. Winsnes 18 &

- Anna Volkmer 19

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 19712 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Alzheimer's disease

- Health care

Speech-language therapists/pathologists (SLT/Ps) are key professionals in the management and treatment of primary progressive aphasia (PPA), however, there are gaps in education and training within the discipline, with implications for skills, confidence, and clinical decision-making. This survey aimed to explore the areas of need amongst SLT/Ps working with people living with PPA (PwPPA) internationally to upskill the current and future workforce working with progressive communication disorders. One hundred eighty-six SLT/Ps from 27 countries who work with PwPPA participated in an anonymous online survey about their educational and clinical experiences, clinical decision-making, and self-reported areas of need when working with this population. Best practice principles for SLT/Ps working with PwPPA were used to frame the latter two sections of this survey. Only 40.7% of respondents indicated that their university education prepared them for their current work with PwPPA. Competency areas of “knowing people deeply,” “practical issues,” “connectedness,” and “preventing disasters” were identified as the basic areas of priority and need. Respondents identified instructional online courses (92.5%), sample tools and activities for interventions (64.8%), and concrete training on providing care for advanced stages and end of life (58.3%) as central areas of need in their current work. This is the first international survey to comprehensively explore the perspectives of SLT/Ps working with PwPPA. Based on survey outcomes, there is a pressing need to enhance current educational and ongoing training opportunities to better promote the well-being of PwPPA and their families, and to ensure appropriate preparation of the current and future SLT/P workforce.

Introduction

Worldwide, it is estimated that a person receives a diagnosis of dementia every three seconds, and 78 million people are projected to be affected by dementia by 2030 1 . Despite these staggering figures, current infrastructures to provide proactive and longitudinal medical care to this population are frequently insufficient. Between 50–80% of dementia cases go undocumented in primary care in high income countries 2 , a statistic that only rises in countries classified as low to middle income 1 , 2 , 3 . In the words of the World Health Organization (WHO) Director General, dementia is a “looming… public health disaster, ‘a tidal wave’” 3 , 4 .

Dementia is classified as young onset when it occurs before the age of 65 5 , 6 , 7 . A recent systematic review by Hendriks et al. 7 determined that approximately 370,000 people worldwide are diagnosed with young-onset dementia per year. While a much smaller percentage, the prevalence of young-onset dementia and far-reaching societal implications are significant. Young-onset dementias, ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to frontotemporal dementia to Parkinson’s disease, insidiously disrupt mechanisms of communicative competence 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 and therefore warrant speech and language intervention. Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a distinctive subtype of young-onset dementia syndromes that selectively impacts functions of speech and language at the milder stages of the condition 20 , 21 , 22 . Identifying the onset of PPA, or its milder stages, poses significant challenges due to the relative complexity and rarity of the condition 20 , 21 , 22 . In the absence of a one-to-one correspondence between presentation and underlying pathology, PPA can present as one of three established variants (semantic, nonfluent, and logopenic) or heterogeneously, where symptomatology and evolution of presentation can vary starkly 20 , 21 , 22 . Despite these differences, the functional impact of PPA encompasses all variants: a fundamental change and progressive loss to communicative ability.

The capacity to communicate is an imperative feature of the human experience. A behavioral approach to the care of people living with PPA (PwPPA) is paramount to enhance, maintain, or compensate for communication loss. Presently, there is no curative treatment publicly available for this condition 22 . Speech and language therapy is the primary intervention that can slow down the behavioral impact of symptoms, which immediately impacts positive engagement, participation, and quality of life 23 , 24 , 25 . Such intervention has been shown to maintain communication abilities for longer through both compensatory and restitutive approaches 23 , 24 , 25 . Early referral to speech and language therapy is imperative to optimize possible improvements, maintenance, and compensation for decline in linguistic capacity faced by PwPPA 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 . Speech-language therapists/pathologists (SLT/Ps) are recognized as central specialists in the care of PwPPA with roles in the diagnosis and coordinated care of the condition 22 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 . Kate Swaffer, founder of Dementia Alliance International (DAI), and person living with the semantic variant of PPA, has spoken publicly about the pressing need for SLT/Ps to be consistently integrated in the care of those living with the condition.

“People with dementia who will almost all have language and speech changes, need proactive speech pathology after diagnosis, not just a speech pathologist to attend when we can no longer swallow well nearer to the end of life… this is how I have managed to still speak as well as I do.” 32 .

Despite this need, there remains a consequential gap in the number of people living with dementia globally who qualify for speech and language therapy and those that receive this service 27 , 33 , 34 . Evidence demonstrates that PwPPA must begin speech and language intervention as early as possible to avoid the risk of not benefitting from impairment-based or functional interventions 26 , 33 . Furthermore, as highlighted by Swaffer (2019), people living with early-onset dementias, such as PPA, and their families seek support to optimize participation and quality of life outcomes, which is bolstered by appropriate and timely access to SLT/P intervention 31 , 35 . Perhaps more critically, beyond gaps in referrals, SLT/Ps report limited confidence and feel underprepared for working with PwPPA 34 , 36 , 37 .

In response to these concerns, a group of international expert clinician-academic SLT/Ps worked collaboratively to establish best-practice principles to guide SLT/P services for PwPPA and their families 38 . The consensus process culminated in a set of seven best practice principles visualized in the form of the “clock model”. With the aim of promoting autonomy and person-centered care, these principles represent concepts of “knowing people deeply,” “preventing disasters,” “practical issues,” “professional development,” “connectedness,” “barriers and limitations,” and “peer support and mentoring towards a shared understanding” (see Table 1 ). The principles provide a framework for the essential components of SLT/P intervention and can be used to guide clinical decision-making, care coordination and service development in the SLT/P field. Further, use of the principles can be extended to the professional development, training and education needs of the current and future SLT/P workforce. Utilizing the principles of the aforementioned aspects of SLT/P practice has the potential to close the current gap between the expressed need for SLT/P services by PwPPA and their families, and the readiness of SLT/Ps to provide best-practice care and innovation in the PPA field.

Furthermore, the best practice principles can guide the development of educational modules and training tools for future and current SLT/Ps seeking to provide consistent and evidence-based care for PwPPA. They can also serve as a starting point for maximizing the care for communication loss available to the broader spectrum of dementias. However, to optimally apply these principles to a future set of educational resources, a global understanding of future and current providers must be established. There are significant translational applications of this work on PPA as communication challenges are experienced across neurodegenerative conditions 39 , 40 and people with non-language led dementias and their families identify SLT/Ps as essential in providing them with the relevant support 41 . While PPA is currently the only recognized language-led dementia syndrome, enhancing current SLT/P education, training, and services will allow us to upskill capacity within the profession and generalize these skills to a broader population. This is especially relevant as the functional impact of language impairment in dementia has yet to be fully characterized 40 : while decline in linguistic function in progressive conditions is well-documented 42 , 43 , the clinical relevance of these changes, and how these can be addressed through SLT/P intervention, remains to be widely recognized.

To develop a relevant and viable resource, gaps in current educational opportunities and exposure to aspects of the PwPPA care continuum must be addressed. As such, the aim of this study was to investigate a more global perspective on SLT/P confidence in enacting the roles and responsibilities within each of these principles, as well as clinical prioritization and ranking of basic competencies when working with PwPPA. To accomplish this, we conducted a survey to explore the experiences of SLT/Ps working with PwPPA with reference to their clinical settings, educational experiences, clinical decision-making, and self-reported areas of need in current practices of care.

Survey structure

The survey is reported in line with the CHERRIES guidelines for electronic surveys 44 (see Supplementary Table S1). Survey items were developed by a core set of the study authors: JG, JC, RJ, ML, EM, MP, and AV (see Supplementary Table S2). Data was collected anonymously, where IP addresses were suppressed, via the Qualtrics® (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) survey platform and respondents had the option to review their responses and skip over any survey items to maximize responses. Participation was entirely voluntary without provided incentives. Participants could review all responses prior to submitting. For a total of 31 questions, one to five questions were displayed per screen over 10 screens. The open, non-adaptive, survey structure consisted of five parts: (1) identity, (2) clinical setting and exposure to PPA, (3) educational experiences, (4) clinical decision-making, and (5) areas of need (see Supplementary Table S2). The first sections were predominantly open-ended for respondents to fill out. For clinical decision-making, survey items were created to investigate clinician confidence, prioritization, and ratings of basic competency for each of Volkmer et al. 38 best practice principles. Confidence was ranked on a five-point scale (0 = not at all confident, 1 = slightly confident, 2 = somewhat confident, 3 = confident, 4 = entirely confident). Priorities and basic competencies were ranked on a 7-point scale (1 = highest, 7 = lowest). Areas of need included multiple choice questions related to the areas of educational needs and the adaptation of existing tools for PPA, followed by the open-response question, “What are three things you wish you knew when you first started working with PPA?”. Survey items were translated by native speakers of French (ML and GD), German (NU and JG), Japanese (TS), Norwegian (MN and IEW), Portuguese (BCB), and Spanish (SG).

Survey distribution

Ethical clearance for this work (project ID: STUDY00017617, PI: Jeanne Gallée) was obtained on March 23rd, 2023 from the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (HSD). All methods were performed according to relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each study participant. Data collection was conducted by method of network sampling between April 13th, 2023 and January 31st, 2024. SLT/Ps were recruited using a snowball method. Announcements for the study were disseminated on social media platforms (including but not limited to X and relevant speech-language communities on Facebook), American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) Sig 2 online discussion boards, and emails to viable contacts within user networks. Initial distribution of the survey occurred through direct contact with the International SLT/P PPA Network 38 , 45 , where working members shared the survey with their own professional networks in African, European, and North American countries. Professional associations that represented speech-language pathologists around the world were contacted by the first author. These included the 'Adult and Elderly Language Working Group' of the Brazilian Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Society, Colegio de Fonoaudiología de Chile, Colombian Association of Phonoaudiology, Deutscher Bundesverband für Logopädie e.V., Deutschschweizer Logopädinnen- und Logopädenverband, Emirates Speech-Language Pathology Society, Hong Kong Association of Speech Therapists, Indian Speech and Hearing Association, Israeli Speech, Hearing and Language Association, Österreichische Gesellschaft für Logopädie, Phoniatrie und Pädaudiologie, Russian Public Academy of Voice, Saudi Society of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, Speech Pathologists and Audiologist Association in Nigeria (SPAAN), Speech Pathology Australia, Speech-Language and Audiology Association of Trinidad and Tobago (SLAATT), South African Speech Language Hearing Association (SASLHA), and Thai Speech-Language and Hearing Association. Additional centers for speech and language services in Germany, Japan and Kenya were contacted.

Survey analysis

A mixed-methods approach was implemented to analyze the quantitative and open-ended feedback. Descriptive statistics were used to aggregate quantitative survey responses. Open-ended survey responses were initially translated to English via Google Translate and then validated or hand checked and corrected by the writers of the original survey. Three coders (JG, JC, and AV) performed content analyses to identify patterns in reported SLT/P experiences and needs. The best practice principles were used as a predefined set of categories to code for content. Consensus was established on 10% of open-ended responses following independent coding (see Supplementary Table S3). The remainder of the response codes were then collated by the first author (JG).

Three hundred thirty-seven users clicked upon the survey link and 189 provided consent. Where respondents failed to provide consent all consequent responses to any survey items were excluded from the analysis. An additional three respondents who reported to not be SLT/Ps were excluded. Data was collected from 186 respondents across 27 countries (see Table 2 ) in seven languages and included in the analysis. Of the 186 participants included in the analysis, the average survey completion rate was 84.2% (SD: 25.1%), where 100% (186) completed the section on identity, 97.3% (181) on clinical setting and exposure to PPA, 90.9% (169) on educational experiences, 65.1% (121) on clinical decision-making and all areas of need, with exception of the final open-ended question (e.g., “What are three things you wish you knew when you first started working with PPA?; 45.7% [85]). Ninety-eight users completed the survey in English, 29 in French, three in German, 13 in Japanese, 17 in Norwegian, 10 in Portuguese, and 16 in Spanish.

Over half of the respondents (98) reported to be based in Europe, followed by 36 in Northern Anglo-America, 19 in Asia, 13 in Africa, 11 in Latin America, and 9 in Oceania (see Fig. 1 and Table 2 ). The average age was 38.2 years (SD: 11.2). Sixty-six percent of respondents described themselves as monocultural and 47% as monolingual, where the average number of languages spoken was 1.87 (SD: 1.08).

Global distribution of participant sample. Results consisted of 186 respondents from 27 countries from six continents. Map was created through mapchart.net.

Clinical practice

Fifty-eight percent of respondents reported to work in an urban setting that was either private practice (45.0%) or a hospital setting (38.3%). While 47% of participants reported to be multilingual, in these clinical settings, only 22.3% of respondents reported to work in more than one language. Most respondents (62.4%) reported to work in an interdisciplinary team, where 36.5% worked in a team of SLT/Ps and 23.5% as independent/sole charge clinicians (17.8% of respondents reported to work in various configurations). Respondents reported to have worked an average of 11.8 years (SD: 9.56, range: 0–43.0) as SLT/Ps, with 6.00 years (SD: 6.29, range: 0–30.0) of exposure to PwPPA. In their work setting, 81.8% reported to have had a SLT/P mentor, where 31.1% affirmed that this mentor had experience with PwPPA. Respondents reported to know approximately seven other SLT/Ps working with PPA (SD: 7.98), across their local and global networks of colleagues.

Only 59.2% of respondents stated that they first learned about PPA during their university education (either Bachelor’s or Master’s), with almost a quarter (24%) reporting that it was not until their place of work that they received this necessary training. A minority of respondents reported to learn about PPA during a clinical placement (6.51%) or doctoral training (5.91%). Eighteen percent reported that their highest degree was a bachelor’s or vocational equivalent, 53.3% a master’s, and 18.6% a doctoral degree. Most respondents estimated to have received less than two hours of education on PPA during their academic training (52.1%), where only 10.1% affirmed to have received more than 5 h. Thematically, 42.9% stated that these educational hours covered processes of assessment of PwPPA, 30.4% interventions for PPA, and 12.5% counseling specific to the needs of PwPPA (with 32.7% reporting to have learned about counseling more generally). Of these respondents, only 40.7% affirmed that their university-level education was beneficial to their current work with PwPPA and 28.0% to have had a clinical placement with PwPPA in the context of their SLT/P training. Finally, 50.0% disclosed having sought out professional development opportunities specific to PPA and 48.5% shared that they were members of a PPA study group. Global distributions of the topics covered in university-level education for speech and language therapy can be seen in Table 3 . Global regions were defined as the divisions proposed by the United Nations 46 : Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, and Oceania.

Clinical decision-making

The majority of respondents reported being confident to entirely confident on the best practice principles of “knowing people deeply” (69.9%), seeking “professional development” opportunities (60.9%), and “practical issues” (60.2%; see Fig. 2 ). In contrast, the majority of respondents felt somewhat or less confident in “preventing disasters” (65.0%), “barriers and limitations” (56.9%), and “peer support and mentorship towards a shared understanding” (51.5%). Confidence levels varied by years of clinical experience working with PwPPA (see Fig. 3 ). At career onset (0–1 years), confidence averaged at slightly to somewhat confident for all best practice principles (average: 2.59, SD: 0.31, where 0 = not confident, 3 = somewhat confident, 5 = extremely confident). When comparing reported confidence at career onset with 4 to 6 years of experience, the average upwards shift in confidence was 1.15 (SD: 0.26, range: 0.84–1.53), representing a shift from slightly/somewhat confident to confident for “knowing people deeply” and “connectedness,” slightly/somewhat confident to somewhat confident for “preventing disasters,” “practical issues,” “professional development,” “barriers and limitations,” and “peer support and mentorship towards shared understanding.” In comparison, the average shift from career onset to 10 to 15 years of career experience was 1.10 (SD: 0.24, range: 0.82–1.44), representing the same patterns per principle as the comparison to 4 to 6 years. Principle confidence by regional location of respondents can be seen in Table 4 .

Rankings of confidence, priority, competency, and need for the seven best practice principles (1 = highest and 7 = lowest). Percentages indicate the agreement of participants for each numerical rank. Illustrated in the far-left column (red), respondents ranked themselves to be most confident in “Knowing people deeply” and least confident in “Preventing disasters”. In the second column (yellow), the most agreement was found for “knowing people deeply,” “practical issues,” and “connectedness” as top priorities for a SLT/P working with a new client with PPA, with minimal agreement on priorities for the remaining principles. Basic competency rankings of the best practice principles, indicated in the third column (green), revealed strongest support for “knowing people deeply,” “practical issues,” and “connectedness” as top competencies for SLT/Ps working with PwPPA. Finally, thematic analyses of areas of need in the far-right column (blue), revealed that “professional development,” “knowing people deeply,” and “preventing disasters” were ranked as in most critical need of additional support and resources for SLT/Ps.

Reported SLT/P Confidence by Experience. For each best practice principle, SLT/P confidence is represented by the relative years of experience of working with PwPPA. Average reported levels of confidence ranged between slightly confident and confident, with average upwards shifts towards somewhat confident seen by the time 4 to 6 years of experience were gathered.

For clinical prioritization for a new client with PPA, the majority ranked “knowing people deeply” as the top priority (76.4%), “practical issues” as the second (34.1%) and “connectedness” as the third (29.3%). Finally, respondents ranked these same principles as the top three basic competency areas for SLT/Ps working with PwPPA, where “Knowing people deeply” received 60.9% support, “practical issues” 26.8%, and “connectedness” 20.3%.

Areas of need

Where respondents were asked to indicate the areas of their practice in which they may need more knowledge, access to resources, or support in their work with PwPPA, the top two reported areas of need were designing intervention approaches for PwPPA (59.3%) and providing care for advanced stages and end of life (58.3%; see Table 5 ). Furthermore, when asked to choose from a selection of tools that they deemed helpful and used in other areas of practice that they wished to have for their work with PwPPA, the top three choices respondents selected were instructional online video courses (92.5%), sample tools and activities for interventions (64.8%), and sample goal banks delineated by PPA variant (57.5%).

All open-ended responses to the question “What are three things you wish you knew before working with PPA” aligned with one of more of the seven best practice principles, characterizing respondent reported educational and professional development needs by principle. The three most frequent themes of the open-response coding were “professional development” (65.1%), “Knowing people deeply” (39.8%), and “preventing disasters” (38.6%). These were closely followed by “practical issues” (26.5%) and “barriers and limitations” (24.1%). Finally, “connectedness” (13.3%) and “peer support and mentorship towards a shared understanding” (7.23%) were coded least frequently in the qualitative responses.

Coding of open-ended responses

Professional development.

Foundational knowledge about the diagnostic process of PPA, the three variants, and how these fit into the schema of neurodegenerative conditions was highly sought after. Such knowledge is imperative to meet most principles, from “knowing people deeply” to “practical issues” as it relates to tailoring intervention plans for the now and future. Basic educational gaps were highlighted in respondents’ concerns in relation to “what do you wish you’d known?:

“About the condition. The trajectory and natural history of the PPA conditions.”

“I wish I had more basic medical knowledge about the disease because I feel it helps a lot with understanding the symptoms and their evolution, not restricted to language”

“That the diagnostic categories and labels were only provisional. I have seen "atypical dementias" with communication disorders shift their variants not only as the patients progressed but also as the criteria for classification changed. E.g., "logopenic." A little humility would have been welcome - even the acknowledgement that while stroke, tumor and traumatic types of damage resulting in aphasia have had centuries of examination, the progressive neuronal diseases resulting in aphasia were in the infancy of their aphasiology”

Knowing people deeply

Implementing a person-centered approach to speech and language services was a fundamental feature of the responses. Respondents particularly identified professional development needs related to establishing a relationship with a patient and their support systems, as well as how to adapt therapeutic intervention on an individual basis:

“It's about the person, and not only the disease.”

Adjusting to client and support network preferences, as well as the needs of the condition, was also underscored.

“Support is an ongoing and evolving journey. It can take many forms and is shaped by the client and their resources (geographic, financial, familial support, and personal factors that shape their requests, needs, and preferences).”

Promoting the autonomy of PwPPA was also felt to be a critical skill:

“Skills to provide relational care. Coaching skills and how to empower self-management. How to provide education and information in a tailored and enabling way.”

Preventing disasters

The open-ended responses emphasized the complex concerns and needs that must be addressed when building workforce capacity. Many respondents shared apprehension and felt ill-equipped to provide anticipatory care or to respond to the emotional and ethical issues that arise when working with a progressive condition.

“I would have been more upfront about the area of " Preventing disasters " - I was a new clinician at the time and not yet entirely comfortable with broaching subjects related to death and decline. It would have been key to get these conversations and decisions going ASAP before further language decline occurred, making the conversations more difficult.”

Respondents identified specific areas of need as:

“How to provide counselling related to the progressive nature of the disease.” "People have the right to dignity of risk.” “How to provide therapy that focuses on prevention.”

Practical issues

Practical concerns, such as the kinds of goals to target in speech and language therapy, and when to introduce compensatory or functional goals, were among the top concerns voiced by respondents:

“Functional goals trump linguistic ones! These should be introduced in parallel to the possibility of restorative intervention goals and early on, in fact, immediately.”

These responses paralleled the reported need for concrete guidance in the form of sample goals, interventions, activities; similarly, responses mapped on the reported need for professional development modules on informational counseling and education for both patients and families:

“How to provide AAC intervention in a preventative/preparatory manner.” “Functional goals may be very simple but complex to support patients/families.”

Barriers and limitations

The challenge of receiving a diagnosis, and the associated delays, was also mentioned. Responses such as these highlight the necessity for early and accurate diagnosis of the condition, which is dependent on immediate referral to neurology and SLT/P services and the expertise of the SLT/P in identifying progressive language change.

“It is difficult to help … when they are diagnosed late.”

Participants highlighted that the SLT/P is often the provider that connects PwPPA and their support partners to other services or community supports. Furthermore, respondents shared the relative burden of often being the provider with the most knowledge of the functional impact of PPA, whilst also needing to define and advocate for the SLT/P role to other healthcare providers.

“That I as the SLP may be the greatest advocate for my patients and that I may be the expert on the impact of their condition.”

The relative difficulty of explaining a diagnosis, or describing the speech and language concerns of, within the SLT/Ps scope without the support of other providers, was also described.

“How to give a diagnosis when you are the only likely medical professional who knows about the problem.”

Connectedness

Apprehension and inexperience in identifying, establishing, and maintaining connection between a patient and their community and amongst the interdisciplinary healthcare team were common themes relating to responses that fell under the “Connectedness” principle coding.

“I have to work to convince neurologists and other healthcare providers of my role in helping PwPPA.”

“The necessity to connect with the interprofessional team of each client to ensure continuity of care, eliminate miscommunication and delays in service delivery, and enhance shared understanding of the client and their care needs.”

Peer support and mentorship towards a shared understanding

Finally, respondents shared concerns about apparent knowledge gaps about the functional impact of PPA and how this posed challenges their role as SLT/Ps in the context of the multidisciplinary team.

“That the neurologists and neuropsychologists were—as a generalization—over-confident in their state of practice, and that SLPs were not using our voice, nor being given the credibility we had earned.”

Frustration with the perceived lack of support, especially as it pertains to counseling, was reported:

“These people present with great psychological suffering and I often feel helpless. The psychologists around me do not take care of them because of their language disorders, even if an AAC tool is put in place.”

The apparent lack of university-level and ongoing educational resources for SLT/Ps working with PwPPA was also emphasized:

“Where to find a comprehensive set of helpful resources, such as case examples and approaches?”

This study characterizes the international perspectives of the SLT/P workforce and examines its professional development needs in relation to working with PwPPA and their families. The majority of speech-language intervention research for PPA has been undertaken in English-speaking populations 25 . Comparatively, and using novel survey methods, this study has captured views of SLT/Ps across many more linguistic and cultural contexts, thereby further enhancing our understanding of the complex nature of supporting people with PPA and their families. The survey outcomes reveal compelling evidence that current educational, training, and ongoing support opportunities for SLT/Ps to develop their knowledge and skills in working with PwPPA, a clinical syndrome of dementia, necessitate refinement. Our findings demonstrate a shortfall in the preparedness and professional support capacity that SLT/Ps receive internationally, characterized by insufficient time spent on PPA in university courses, infrequent or rare exposure to PPA during clinical placements, limited access to mentors that are experts in the condition, and an expressed need for more functional and specialized resources for the condition. These concerns justify a global need for a more adequately prepared and supported SLT/P workforce to ensure best practice pre and post-diagnostic care for PwPPA and their families. The findings support use of the best practice principles 38 to guide the systematic development of education, training and professional support opportunities for the SLT/P profession. The strong consensus on the kinds of tools that SLT/Ps would like to see made easily available for training purposes (e.g., online video-based modules on designing intervention approaches for PwPPA and providing care for advanced stages and end of life) and clinical practice (e.g., exemplars of goal banks, tools, and activities for intervention) provide immediate directives for the applications of this work. Investing in the SLT/P workforce is timely and significant. With the current and expected global “tidal wave” of people living with dementia 4 , an upscaled framework of support is critical to ensure the needs of PwPPA and their families can be met. In 2023, a holistic roadmap to guide and enhance the SLT/P’s understanding of and approach to working with PwPPA therapeutically was published 28 ; in fact, the need for a care pathway has been consistently called for 31 , 47 , 48 . The best-practice principles and international perspectives shared here are contributing to and shaping that important work. Continuing ahead, future research should focus on the coproduction and evaluation of a comprehensive care pathway for people with different PPA variants at different disease stages.

Our current outcomes represent a global perspective on needs worldwide. Seven of the 27 countries represented in the survey outcomes were low to middle income 49 , globally distributed in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Differences in educational experiences and reported confidence in the best practice principles emerged by region of practice and experience. Respondents from Asia reported the lowest levels of confidence per principle, whereas those from Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, and Oceania consistently reported the highest levels. Confidence levels in Europe fell closely behind these, with respondents from Africa reporting the second-lowest levels. While the relative overrepresentation of European countries must be taken in consideration here, higher levels of usefulness of education were reported by respondents from Europe and North America. Across all participants, confidence increased with experience, peaking after a few years of practice with PwPPA.