What is a nonverbal learning disorder? Tim Walz’s son Gus’ condition, explained

Gus Walz stole the show Wednesday when his father, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, officially accepted the vice presidential nomination on the third night of the Democratic National Convention.

The 17-year-old stood up during his father’s speech and said, “That’s my dad,” later adding, “I love you, Dad.”

The governor and his wife, Gwen Walz, revealed in a People interview that their son was diagnosed with nonverbal learning disability as a teenager.

A 2020 study estimated that as many as 2.9 million children and adolescents in North America have nonverbal learning disability, or NVLD, which affects a person’s spatial-visual skills.

The number of people who receive a diagnosis is likely much smaller than those living with the disability, said Santhosh Girirajan, the T. Ming Chu professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and professor of genomics at Penn State.

“These individuals are very intelligent and articulate well verbally, but they are typically clumsy with motor and spatial coordination,” he told NBC News. “It’s called a learning disorder because there are a lot of cues other than verbal cues that are necessary for us to keep information in our memory.”

People with NVLD often struggle with visual-spatial skills, such as reading a map, following directions, identifying mathematical patterns, remembering how to navigate spaces or fitting blocks together. Social situations can also be difficult.

“Body language and some of the things we think about with day-to-day social norms, they may not be able to catch those,” Girirajan said.

Unlike other learning disabilities such as dyslexia, signs of the disability typically don't become apparent until adolescence.

Early in elementary school, learning is focused largely on memorization — learning words or performing straightforward mathematical equations, at which people with NVLD typically excel. Social skills are also more concrete, such as playing a game of tag at recess.

“But as you get older, there’s a lot more subtlety, like sarcasm, that you have to understand in social interactions, that these kids might not understand,” said Laura Phillips, senior director and senior neuropsychologist of the Learning and Development Center at the Child Mind Institute, a nonprofit organization in New York.

In her own practice, she typically sees adolescents with NVLD, who usually have an average or above average IQ, when school demands more integrated knowledge and executive functioning, such as reading comprehension or integrating learning between subjects. They also usually seek help for something else, usually anxiety or depression, which are common among people with NVLD.

Sometimes misdiagnosed as autism

Amy Margolis, director of the Environment, Brain, and Behavior Lab at Columbia University, is part of a group of researchers that is beginning to call the disability “developmental visual-spatial disorder” in an effort to better describe how it affects people who have it.

People with NVLD are “very much verbal,” Margolis said, contrary to what the name suggests.

The learning disability is sometimes misdiagnosed as autism spectrum disorder. Margolis led a 2019 study that found that although kids with autism spectrum disorder and NVLD often have overlapping traits, the underlying neurobiology — that is, what’s happening in their brains to cause these traits — is unique between the two conditions.

Margolis is trying to get NVLD recognized by the DSM-5, the handbook health care providers use to diagnose mental health conditions. Without such official recognition, people with NVLD can struggle to get the resources they need, such as special class placements or extra support in school.

“Without an officially recognized diagnosis, it’s hard for parents to understand how to seek information, and then communicate to other people what kinds of things might be challenging for their kid,” Phillips said, adding that widespread awareness is key to helping these families navigate NVLD.

Kaitlin Sullivan is a contributor for NBCNews.com who has worked with NBC News Investigations. She reports on health, science and the environment and is a graduate of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at City University of New York.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

NPR's Book of the Day

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

'Hurdles in the Dark' is a memoir about a kidnapping, juvenile detention and racing

Elvira K. Gonzalez says there was a lot of beauty to growing up in the culturally rich border town of Laredo, Texas. But there were some challenges, too. Her new memoir, Hurdles in the Dark , chronicles some of the more difficult aspects of her adolescence — her mom was kidnapped, Gonzalez was sent to juvenile detention, and she was preyed upon by her hurdling coaches. In today's episode, the author speaks with Here & Now's Deepa Fernandes about the resilience and optimism she carried through all of that, and how it's gotten her to where she is today.

To listen to Book of the Day sponsor-free and support NPR's book coverage, sign up for Book of the Day+ at plus.npr.org/bookoftheday

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

As a Teenager in Europe, I Went to Nudist Beaches All the Time. 30 Years Later, Would the Experience Be the Same?

In July 2017, I wrote an article about toplessness for Vogue Italia. The director, actor, and political activist Lina Esco had emerged from the world of show business to question public nudity laws in the United States with 2014’s Free the Nipple . Her film took on a life of its own and, thanks to the endorsement from the likes of Miley Cyrus, Cara Delevingne, and Willow Smith, eventually developed into a whole political movement, particularly on social media where the hashtag #FreeTheNipple spread at lightning speed. The same year as that piece, actor Alyssa Milano tweeted “me too” and encouraged others who had been sexually assaulted to do the same, building on the movement activist Tarana Burke had created more than a decade earlier. The rest is history.

In that Vogue article, I chatted with designer Alessandro Michele about a shared memory of our favorite topless beaches of our youth. Anywhere in Italy where water appeared—be it the hard-partying Riviera Romagnola, the traditionally chic Amalfi coast and Sorrento peninsula, the vertiginous cliffs and inlets of Italy’s continuation of the French Côte d’Azur or the towering volcanic rocks of Sicily’s mythological Riviera dei Ciclopi—one was bound to find bodies of all shapes and forms, naturally topless.

In the ’90s, growing up in Italy, naked breasts were everywhere and nobody thought anything about it. “When we look at our childhood photos we recognize those imperfect breasts and those bodies, each with their own story. I think of the ‘un-beauty’ of that time and feel it is actually the ultimate beauty,” Michele told me.

Indeed, I felt the same way. My relationship with toplessness was part of a very democratic cultural status quo. If every woman on the beaches of the Mediterranean—from the sexy girls tanning on the shoreline to the grandmothers eating spaghetti al pomodoro out of Tupperware containers under sun umbrellas—bore equally naked body parts, then somehow we were all on the same team. No hierarchies were established. In general, there was very little naked breast censorship. Free nipples appeared on magazine covers at newsstands, whether tabloids or art and fashion magazines. Breasts were so naturally part of the national conversation and aesthetic that Ilona Staller (also known as Cicciolina) and Moana Pozzi, two porn stars, cofounded a political party called the Love Party. I have a clear memory of my neighbor hanging their party’s banner out his window, featuring a topless Cicciolina winking.

A lot has changed since those days, but also since that initial 2017 piece. There’s been a feminist revolution, a transformation of women’s fashion and gender politics, the absurd overturning of Harvey Weinstein’s 2020 rape conviction in New York, the intensely disturbing overturning of Roe v Wade and the current political battle over reproductive rights radiating from America and far beyond. One way or another, the female body is very much the site of political battles as much as it is of style and fashion tastes. And maybe for this reason naked breasts seem to populate runways and street style a lot more than they do beaches—it’s likely that being naked at a dinner party leaves more of a permanent mark than being naked on a glamorous shore. Naked “dressing” seems to be much more popular than naked “being.” It’s no coincidence that this year Saint Laurent, Chloé, Ferragamo, Tom Ford, Gucci, Ludovic de Saint Sernin, and Valentino all paid homage to sheer dressing in their collections, with lacy dresses, see-through tops, sheer silk hosiery fabric, and close-fitting silk dresses. The majority of Anthony Vaccarello’s fall 2024 collection was mostly transparent. And even off the runway, guests at the Saint Laurent show matched the mood. Olivia Wilde appeared in a stunning see-through dark bodysuit, Georgia May Jagger wore a sheer black halter top, Ebony Riley wore a breathtaking V-neck, and Elsa Hosk went for translucent polka dots.

In some strange way, it feels as if the trends of the ’90s have swapped seats with those of today. When, in 1993, a 19-year-old Kate Moss wore her (now iconic) transparent, bronze-hued Liza Bruce lamé slip dress to Elite Model Agency’s Look of the Year Awards in London, I remember seeing her picture everywhere and feeling in awe of her daring and grace. I loved her simple sexy style, with her otherworldly smile, the hair tied back in a bun. That very slip has remained in the collective unconscious for decades, populating thousands of internet pages, but in remembering that night Moss admitted that the nude look was totally unintentional: “I had no idea why everyone was so excited—in the darkness of Corinne [Day’s] Soho flat, the dress was not see-through!” That’s to say that nude dressing was usually mostly casual and not intellectualized in the context of a larger movement.

But today nudity feels loaded in different ways. In April, actor and author Julia Fox appeared in Los Angeles in a flesh-colored bra that featured hairy hyper-realist prints of breasts and nipples, and matching panties with a print of a sewn-up vagina and the words “closed” on it, as a form of feminist performance art. Breasts , an exhibition curated by Carolina Pasti, recently opened as part of the 60th Venice Biennale at Palazzo Franchetti and showcases works that span from painting and sculpture to photography and film, reflecting on themes of motherhood, empowerment, sexuality, body image, and illness. The show features work by Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Louise Bourgeois, and an incredible painting by Bernardino Del Signoraccio of Madonna dell’Umiltà, circa 1460-1540. “It was fundamental for me to include a Madonna Lactans from a historical perspective. In this intimate representation, the Virgin reveals one breast while nurturing the child, the organic gesture emphasizing the profound bond between mother and child,” Pasti said when we spoke.

Through her portrayal of breasts, she delves into the delicate balance of strength and vulnerability within the female form. I spoke to Pasti about my recent musings on naked breasts, which she shared in a deep way. I asked her whether she too noticed a disparity between nudity on beaches as opposed to the one on streets and runways, and she agreed. Her main concern today is around censorship. To Pasti, social media is still far too rigid around breast exposure and she plans to discuss this issue through a podcast that she will be launching in September, together with other topics such as motherhood, breastfeeding, sexuality, and breast cancer awareness.

With summer at the door, it was my turn to see just how much of the new reread on transparency would apply to beach life. In the last few years, I noticed those beaches Michele and I reminisced about have grown more conservative and, despite being the daughter of unrepentant nudists and having a long track record of militant topless bathing, I myself have felt a bit more shy lately. Perhaps a woman in her 40s with two children is simply less prone to taking her top off, but my memories of youth are populated by visions of bare-chested mothers surveilling the coasts and shouting after their kids in the water. So when did we stop? And why? When did Michele’s era of “un-beauty” end?

In order to get back in touch with my own naked breasts I decided to revisit the nudist beaches of my youth to see what had changed. On a warm day in May, I researched some local topless beaches around Rome and asked a friend to come with me. Two moms, plus our four children, two girls and two boys of the same ages. “Let’s make an experiment of this and see what happens,” I proposed.

The kids all yawned, but my friend was up for it. These days to go topless, especially on urban beaches, you must visit properties that have an unspoken nudist tradition. One of these in Rome is the natural reserve beach at Capocotta, south of Ostia, but I felt a bit unsure revisiting those sands. In my memory, the Roman nudist beaches often equated to encounters with promiscuous strangers behind the dunes. I didn’t want to expose the kids, so, being that I am now a wise adult, I went ahead and picked a compromise. I found a nude-friendly beach on the banks of the Farfa River, in the rolling Sabina hills.

We piled into my friend’s car and drove out. The kids were all whining about the experiment. “We don’t want to see naked mums!” they complained. “Can’t you just lie and say you went to a nudist beach?”

We parked the car and walked across the medieval fairy-tale woods until we reached the path that ran along the river. All around us were huge trees and gigantic leaves. It had rained a lot recently and the vegetation had grown incredibly. We walked past the remains of a Roman road. The colors all around were bright green, the sky almost fluorescent blue. The kids got sidetracked by the presence of frogs. According to the indications, the beach was about a mile up the river. Halfway down the path, we bumped into a couple of young guys in fanny packs. I scanned them for signs of quintessential nudist attitude, but realized I actually had no idea what that was. I asked if we were headed in the right direction to go to “the beach”. They nodded and gave us a sly smile, which I immediately interpreted as a judgment about us as mothers, and more generally about our age, but I was ready to vindicate bare breasts against ageism.

We reached a small pebbled beach, secluded and bordered by a huge trunk that separated it from the path. A group of girls was there, sharing headphones and listening to music. To my dismay they were all wearing the tops and bottoms of their bikinis. One of them was in a full-piece bathing suit and shorts. “See, they are all wearing bathing suits. Please don’t be the weird mums who don’t.”

At this point, it was a matter of principle. My friend and I decided to take our bathing suits off completely, if only for a moment, and jumped into the river. The boys stayed on the beach with full clothes and shoes on, horrified. The girls went in behind us with their bathing suits. “Are you happy now? my son asked. “Did you prove your point?”

I didn’t really know what my point actually was. I think a part of me wanted to feel entitled to those long-gone decades of naturalism. Whether this was an instinct, or as Pasti said, “an act that was simply tied to the individual freedom of each woman”, it was hard to tell. At this point in history, the two things didn’t seem to cancel each other out—in fact, the opposite. Taking off a bathing suit, at least for my generation who never had to fight for it, had unexpectedly turned into a radical move and maybe I wanted to be part of the new discourse. Also, the chances of me going out in a fully sheer top were slim these days, but on the beach it was different. I would always fight for an authentic topless experience.

After our picnic on the river, we left determined to make our way—and without children—to the beaches of Capocotta. In truth, no part of me actually felt very subversive doing something I had been doing my whole life, but it still felt good. Once a free breast, always a free breast.

This article was originally published on British Vogue .

More Great Living Stories From Vogue

Meghan Markle Is Returning to Television

Is Art Deco Interior Design Roaring Back Into Style?

Kate Middleton and Prince William Share a Never-Before-Seen Wedding Picture

Sofia Richie Grainge Has Given Birth to Her First Child—And the Name Is…

The 10 Best Spas in the World

Never miss a Vogue moment and get unlimited digital access for just $2 $1 per month.

Vogue Daily

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Vogue. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

International Spillovers of U.S. Fiscal Challenges

Expansionary fiscal policies have increased significantly following the subprime crisis in 2007 and the COVID-19 crisis, leading to fiscal dominance concerns, where a growing share of monetary authorities may be forced to deviate from policy targets to accommodate fiscal policies. Meanwhile, peripheral economies are constantly influenced by monetary and fiscal conditions in center economies, with the United States (U.S.) as the predominant force. In light of these developments, we examine the potential international spillovers from U.S. inflationary spells and growing fiscal concerns to the policy interest rates in Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) and Developed Economies (DEs). We introduce a new index of fiscal dominance concerns using Principal Components Analysis, and extend the concept to an international perspective, as opposed to previous literature examining fiscal dominance in a domestic environment. The results are confirmed by robustness analysis and show that greater U.S. fiscal challenges affect negatively the policy rates in both EMEs and DEs, with a greater impact observed in EMEs. Moreover, a low degree of financial repression is associated with more significant spillover effects from greater U.S. fiscal challenges.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the economics division of Linköping University, Sweden. The authors are deeply grateful to Bo Sjö, Donghyun Park, Jamel S., Ayhan Kose, Franziska Ohnsorge, and Naotaka Sugawara for sharing the fiscal space data. Joshua Aizenman gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Dockson Chair at the University of Southern California The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research and the Asian Development Bank.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Essay Service Examples Psychology Adolescence

Understanding Adolescence Essay: Challenges and Solutions in the USA

Table of contents

What is adolescence, problems of adolescence, how can these problems be solved.

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

Our writers will provide you with an essay sample written from scratch: any topic, any deadline, any instructions.

Cite this paper

Related essay topics.

Get your paper done in as fast as 3 hours, 24/7.

Related articles

Most popular essays

- Adolescence

Every 40 seconds an individual commits suicide, making it the tenth leading cause of death...

- Self Esteem

There are two critical aspects of personality that can determine a person’s self worth - self...

Lito is an eighteen-year-old male. He claims he plays electronic sports for four to five hours a...

Rena has a height of 5’5” while Ashley has a height of 5’6”. They are 17 years old and on their 12...

Sleep is vital for the human body to function but due to the stressful and busy life of...

Did you know that archery is the second oldest sport in the world? This fact proves that sport...

- Juvenile Delinquency

Juvenile Delinquency has been an ongoing phenomenon for years and will unfortunately continue in...

This criminal justice research paper is an analysis of the family dynamics affecting juvenile...

Body image dissatisfaction continues to be a major concern in America’s youth, especially in...

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via [email protected].

We are here 24/7 to write your paper in as fast as 3 hours.

Provide your email, and we'll send you this sample!

By providing your email, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy .

Say goodbye to copy-pasting!

Get custom-crafted papers for you.

Enter your email, and we'll promptly send you the full essay. No need to copy piece by piece. It's in your inbox!

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- Adolescent Psychology

Challenges of Adolescence

Recognizing adolescence

Adolescence is a period of life with specific health and developmental needs and rights. It is also a time to develop knowledge and skills, learn to manage emotions and relationships, and acquire attributes and abilities that will be important for enjoying the adolescent years and assuming adult roles.

All societies recognize that there is a difference between being a child and becoming an adult. How this transition from childhood to adulthood is defined and recognized differs between cultures and over time. In the past it has often been relatively rapid, and in some societies it still is. In many countries, however, this is changing.

Age: not the whole story

Age is a convenient way to define adolescence. But it is only one characteristic that delineates this period of development. Age is often more appropriate for assessing and comparing biological changes (e.g. puberty), which are fairly universal, than the social transitions, which vary more with the socio-cultural environment.

CHALLENGES OF ADOLESCENCE

Adolescence is a time in a young person’s life where they move from dependency on their parents to independence, autonomy and maturity. The young person begins to move from the family group being their major social system, to the family taking a lesser role and being part of a peer group becomes a greater attraction that will eventually lead to the young person to standing alone as an adult.

No-one can deny that for any one person facing changes in their lives in the biological, cognitive, psychological, social, moral and spiritual sense, could find this time both exciting and daunting. With the increase in independence comes increases in freedom, but with that freedom, comes responsibilities. Attitudes and perspectives change and close family members often feel they are suddenly living with a stranger.

Biological Challenges

Adolescence begins with the first well-defined maturation event called puberty. Included in the biological challenges are the changes that occur due to the release of the sexual hormones that affect emotions. Mood changes can increase, which can impact on relationships both at home with parents and siblings and socially or at school.

Cognitive Challenges

Piaget, in his theory of social development believed that adolescence is the time when young people develop cognitively from “concrete operations” to “formal operations”. So they are able to deal with ideas, concepts and abstract theories. It takes time for confidence to build with using these newly acquired skills, and they may make mistakes in judgement. Learning through success and failure is part of the challenge of the learning process for the adolescent.

Adolescents are egocentric, they can become self-conscious; thinking they are being watched by others, and at other times want to behave as if they were on a centre stage and perform for a non-existent audience. For example, acting like a music idol, singing their favourites songs in their room, with all the accompanying dance steps.

Psychological Challenges

The psychological challenges that the adolescent must cope with are moving from childhood to adulthood. A new person is emerging, where rules will change, maybe more responsibilities will be placed on him/her so that a certain standard of behaviour is now required to be maintained. Accountability is becoming an expectation from both a parental and legal concept.

As adolescents continue their journey of self-discovery, they continually have to adjust to new experiences as well as the other changes happening to them biologically and socially. This can be both stressful and anxiety provoking. It therefore is not surprising that adolescents can have a decreased tolerance for change; hence it becomes increasingly more difficult for them to modulate their behaviours which are sometimes displayed by inappropriate mood swings and angry outbursts.

Health Issues of adolescence:

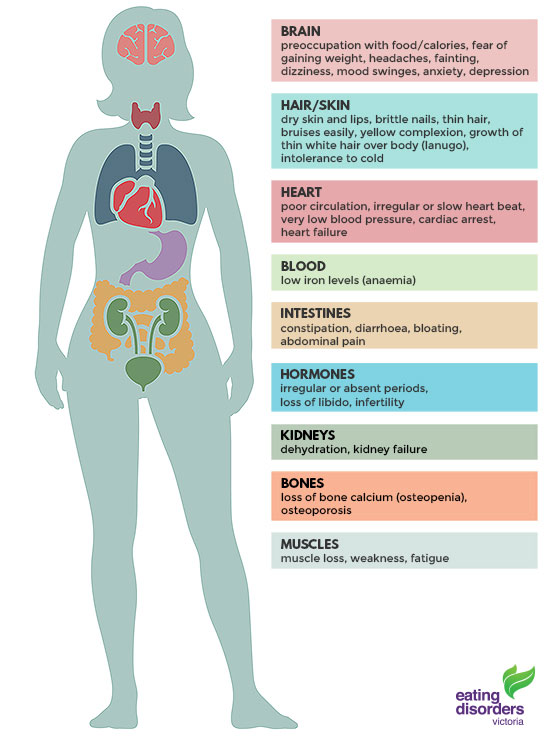

Eating Disorders

An eating disorder is a serious mental illness, characterised by eating, exercise and body weight or shape becoming an unhealthy preoccupation of someone's life. Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice, a diet gone wrong or a cry for attention. Eating disorders can take many different forms and interfere with a person’s day to day life.

Types of Eating Disorders

An eating disorder is commonly defined as an all-consuming desire to be thin and/or an intense fear of weight gain. The most common eating disorders among adolescents are anorexia, bulimia and binge-eating disorder. Even patients that do not meet all of the clinical criteria for an eating disorder can be at serious risk and should seek medical treatment.

Anorexia Nervosa

Teenagers with anorexia may take extreme measures to avoid eating and control the quantity and quality of the foods they do eat. They may become abnormally thin, or thin for their body, and still talk about feeling fat. They typically continue to diet even at very unhealthy weights because they have a distorted image of their body.

Signs of anorexia nervosa

- A distorted view of one’s body weight, size or shape; sees self as too fat, even when very underweight

- Hiding or discarding food

- Obsessively counting calories and/or grams of fat in the diet

- Denial of feelings of hunger

- Developing rituals around preparing food and eating

- Compulsive or excessive exercise

- Social withdrawal

- Pronounced emotional changes, such as irritability, depression and anxiety

Physical signs of anorexia include rapid or excessive weight loss; feeling cold, tired and weak; thinning hair; absence of menstrual cycles in females; and dizziness or fainting.

Teenagers with anorexia often restrict not only food, but relationships, social activities and pleasurable experiences.

Physical Signs and Effects of Anorexia Nervosa

Bulimia Nervosa

Teenagers with bulimia nervosa typically ‘binge and purge’ by engaging in uncontrollable episodes of overeating (bingeing) usually followed by compensatory behavior such as: purging through vomiting, use of laxatives, enemas, fasting, or excessive exercise. Eating binges may occur as often as several times a day but are most common in the evening and night hours.

Teenagers with bulimia often go unnoticed due to the ability to maintain a normal body weight.

Bulimia Nervosa often starts with weight-loss dieting. The resulting food deprivation and inadequate nutrition can trigger what is, in effect, a starvation reaction - an overriding urge to eat. Once the person gives in to this urge, the desire to eat is uncontrollable, leading to a substantial binge on whatever food is available (often foods with high fat and sugar content), followed by compensatory behaviours. A repeat of weight-loss dieting often follows, leading to a binge/purge/exercise cycle which becomes more compulsive and uncontrollable over time.

Signs of bulimia nervosa

- Eating unusually large amounts of food with no apparent change in weight

- Hiding food or discarded food containers and wrappers

- Excessive exercise or fasting

- Peculiar eating habits or rituals

- Frequent tips to the bathroom after meals

- Inappropriate use of laxatives, diuretics, or other cathartics

- Overachieving and impulsive behaviors

- Frequently clogged showers or toilets

Physical signs of bulimia include discolored teeth, odor on the breath, stomach pain, calluses/scarring on the hands caused by self-inducing vomiting, irregular or absent menstrual periods, and weakness or fatigue.

Teenagers with bulimia often have a preoccupation with body weight and shape, as well as a distorted body image. The clinical diagnosis commonly defines a teenager as having bulimia if they binge and purge on average once a week for at least three consecutive months.

Physical Signs and Effects of Bulimia Nervosa

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are infections that are passed from one person to another through sexual contact. The causes of STDs are bacteria, parasites, yeast, and viruses. There are more than 20 types of STDs, including

Genital herpes

- Trichomoniasis

Most STDs affect both men and women, but in many cases the health problems they cause can be more severe for women. If a pregnant woman has an STD, it can cause serious health problems for the baby.

Antibiotics can treat STDs caused by bacteria, yeast, or parasites. There is no cure for STDs caused by a virus, but medicines can often help with the symptoms and keep the disease under control.

Correct usage of latex condoms greatly reduces, but does not completely eliminate, the risk of catching or spreading STDs. The most reliable way to avoid infection is to not have anal, vaginal, or oral sex.

Chlamydia is an STD caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis). This bacterium only infects humans. Chlamydia is the most common infectious cause of genital and eye diseases globally. It is also the most common bacterial STD.

Women with chlamydia do not usually show symptoms. Any symptoms are usually non-specific and may include:

- bladder infection

- a change in vaginal discharge

- mild lower abdominal pain

If a person does not receive treatment for chlamydia, it may lead to the following symptoms:

- pelvic pain

- painful sexual intercourse, either intermittently or every time

- bleeding between periods

This STD is caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). The virus affects the skin, cervix, genitals, and some other parts of the body. There are two types:

- HSV-1, also known as herpes type 1

- HSV-2, also known as herpes type 2

Herpes is a chronic condition. A significant number of individuals with herpes never show symptoms and do not know about their herpes status.

HSV is easily transmissible from human to human through direct contact. Most commonly, transmission of type 2 HSV occurs through vaginal, oral, or anal sex. Type 1 is more commonly transmitted from shared straws, utensils, and surfaces.

In most cases, the virus remains dormant after entering the human body and shows no symptoms.

Symptoms of genital herpes

- blisters and ulceration on the cervix

- vaginal discharge

- pain on urinating

- generally feeling unwell

- cold sores around the mouth in type 1 HSV

This sexually transmitted bacterial infection usually attacks the mucous membranes. It is also known as the clap or the drip. The bacterium, which is highly contagious, stays in the warmer and moister cavities of the body.

The majority of women with gonorrhea show no signs or symptoms. If left untreated, females may develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Males may develop inflammation of the prostate gland, urethra, or epididymis.

The disease is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The bacteria can survive in the vagina, penis, mouth, rectum, or eye. They can be transmitted during sexual contact.

Symptoms of gonorrhea may occur between 2 to 10 days after initial infection, in some cases, it may take 30 days. Some people experience very mild symptoms that lead to mistaking gonorrhea for a different condition, such as a yeast infection.

Males may experience the following symptoms:

- burning during urination

- testicular pain or swelling

- a green, white, or yellow discharge from the penis

Females are less likely to show symptoms, but if they do, these may include:

- spotting after sexual intercourse

- swelling of the vulva, or vulvitis

- irregular bleeding between periods

- pink eye, or conjunctivitis

- pain in the pelvic area

- burning or pain during urination

HIV and AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) attacks the immune system, leaving its host much more vulnerable to infections and diseases. If the virus is left untreated, the susceptibility to infection worsens.

HIV can be found in semen, blood, breast milk, and vaginal and rectal fluids. HIV can be transmitted through blood-to-blood contact, sexual contact, breast-feeding, childbirth, the sharing of equipment to inject drugs, such as needles and syringes, and, in rare instances, blood transfusions.

With treatment, the amount of the virus present within the body can be reduced to an undetectable level. This means the amount of HIV virus within the blood is at such low levels that it cannot be detected in blood tests. It also means that HIV cannot be transmitted to other people. A person with undetectable HIV must continue to take their treatment as normal, as the virus is being managed, not cured.

HIV is a virus that targets and alters the immune system, increasing the risk and impact of other infections and diseases. Without treatment, the infection might progress to an advanced disease stage 3 called AIDS. However, modern advances in treatment mean that people living with HIV in countries with good access to healthcare very rarely develop AIDS once they are receiving treatment.

Mental Health Disorder

1.Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders characterized by significant feelings of anxiety and fear. Anxiety is a worry about future events, and fear is a reaction to current events. These feelings may cause physical symptoms, such as a fast heart rate and shakiness.

Occasional anxiety is an expected part of life. You might feel anxious when faced with a problem at work, before taking a test, or before making an important decision. But anxiety disorders involve more than temporary worry or fear. For a person with an anxiety disorder, the anxiety does not go away and can get worse over time. The symptoms can interfere with daily activities such as job performance, school work, and relationships.

There are several types of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and various phobia-related disorders.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

People with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) display feel excessive, unrealistic worry and tension with little or no reason , most days for atleast 6 months, about a number of things such as personal health, work, social interactions, and everyday routine life circumstances. The fear and anxiety can cause significant problems in areas of their life, such as social interactions, school, and work.

Generalized anxiety disorder symptoms include:

- Feeling restless, wound-up, or on-edge

- Being easily fatigued

- Having difficulty concentrating; mind going blank

- Being irritable

- Having muscle tension

- Difficulty controlling feelings of worry

- Having sleep problems, such as difficulty falling or staying asleep, restlessness, or unsatisfying sleep

Panic Disorder

People with panic disorder have recurrent unexpected panic attacks. Panic attacks are sudden periods of intense fear that come on quickly and reach their peak within minutes. Attacks can occur unexpectedly or can be brought on by a trigger, such as a feared object or situation.

During a panic attack, people may experience:

- Heart palpitations ( unusually strong or irregular heartbeats) , a pounding heartbeat, or an accelerated heart rate.

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath, smothering, or choking

- Feelings of impending doom

- Feelings of being out of control

People with panic disorder often worry about when the next attack will happen and actively try to prevent future attacks by avoiding places, situations, or behaviors they associate with panic attacks. Worry about panic attacks, and the effort spent trying to avoid attacks, because significant problems in various areas of the person’s life, including the development of agoraphobia - People with agoraphobia have an intense fear of two or more of the following situations:

- Using public transportation

- Being in open spaces

- Being in enclosed spaces

- Standing in line or being in a crowd

- Being outside of the home alone

2. Mood Disorders

The development of emotional or behavioral symptoms in response to an identifiable stressors that occur within 3 months of the onset of the stressors in which low mood, tearfulness, or feelings of hopelessness are predominant.

3. Major Depressive Disorder (MDD):

A period of atleast 2 weeks during which there is either depressed mood or the loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities. In children and adolescents, the mood may be irritable rather than sad.

4. Bipolar Disorder:

A period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and abnormally and persistency increased activity or energy, lasting at least 4 consecutive days and present most of the day, nearly every day, or that requires hospitalization.

5. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Definitions of the symptom complex known as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) differ, but severe problems with concentration or attention and/or hyperactivity are estimated to affect adolescents. Six times as many boys as girls are affected. The main consequences of ADHD are poor academic performance and behavioural problems, although adolescents with ADHD are at substantially higher risk of serious accidents, depression, and other psychological problems. About 80% of children with ADHD continue to have the disorder during adolescence, and as many as 50% of adolescents still do throughout adulthood.

6. School phobia

School phobia also called school refusal, is defined as a persistent and irrational fear of going to school. It must be distinguished from a mere dislike of school that is related to issues such as a new teacher, a difficult examination, the class bully, lack of confidence, or having to undress for a gym class. The phobic adolescent shows an irrational fear of school and may show marked anxiety symptoms when in or near the school.

7. Learning disabilities

Learning abilities encompasses disorders that affect the way individuals with normal or above normal intelligence receive, store, organize, retrieve, and use information. Problems included dyslexia and other specific learning problems involving reading, spelling, writing, reasoning, and mathematics. Undiagnosed learning disabilities are a common but managerable cause of young people deciding to leave school at the earliest opportunity.

Social Issues

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse is sexual behavior or a sexual act forced upon a woman, man or child without their consent. Sexual abuse includes abuse of a woman, man or child by a man, woman or child.

Sexual abuse or violence against children and adolescents is defined as a situation in which children or adolescents are used for the sexual pleasure of an adult or older adolescent, (legally responsible for them or who has some family relationship, either current or previous), which ranges from petting, fondling of genitalia, breasts or anus, sexual exploitation, voyeurism, pornography, exhibitionism, to the sexual intercourse itself, with or without penetration.

Sexual abuse in childhood may result in problems of depression and low self-esteem as well as in sexual difficulties, either avoidance of sexual contact or, on the other hand, promiscuity or prostitution. Research studies suggest that the kinds of abuse that appear to be the most damaging are those that involve father figures, genital contact, and force.

As reports of sexual abuse of children have increased, ways to protect children are now being carried out. Some information campaigns have concentrated on children’s contacts with strangers-for example, “Never get into a car with anyone you don’t know, “Never go with someone who says he or she has some candy for you”. However, in the majority of reported assaults children are victimized by people they know. To prevent this kind of assaults, children need to be taught to recognize signs of trouble and to be assertive enough to report them to a responsible adult. How to accomplish this task represents an important challenge to prevention-oriented researchers.

Sexual abuse of children is regarded by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the major public health problems. Studies conducted in different countries suggest that 7-36% of girls and 3-29% of boys suffered sexual abuse.

Substance Abuse

Many communities are plagued with problems of substance abuse among youth. Some children start smoking or chewing tobacco at an early age, aided by easy access to tobacco products. Many of our youth, with limited supervision or few positive alternatives, drink too much beer and liquor. Other youth, influenced by their peers, use other illegal drugs. Our youth suffer from substance abuse in familiar ways: diminished health, compromised school performance, and reduced opportunities for development. Our communities also bear a heavy burden for adolescent substance abuse. Widespread use and abuse of tobacco, alcohol, and illegal drugs by teens can result in increased accidents, health costs, violence, crime, and an erosion of their future potential as workers and citizens.

Protective factors are personal and environmental factors that decrease the likelihood that a person may experience a particular problem. Protective factors act as buffers against risk factors and are frequently the inverse of risk factors.

Personal risk factors for substance abuse include: poor school grades, low expectations for education, school dropout, poor parent communication, low self-esteem, strong negative peer influences, peer use, lack of perceived life options, low religiosity, lack of belief about risk, and involvement in other high-risk behaviours. Environmental risk factors include: lack of parental support, parental practice of high-risk behaviors, lack of resources in the home, living in an urban area, poor school quality, availability of substances, community norms favorable to substance use, extreme economic deprivation, and family conflict.

Protective factors may include peer tutoring to improve school grades, mentoring and scholarship programs to increase educational opportunities, programs to build strong communication and refusal Preface Work Group for Community Health and Development iv skills, information to increase understanding about risk, and the enforcement of local laws prohibiting the illegal sale of tobacco and alcohol products to youth.

Influence of Electronic Media

Electronic devices are an integral part of adolescent's lives in the twenty-first century. The world of electronic devices, however, is changing dramatically. Television, which dominated the media world through the mid-1990s, now competes in an arena crowded with cell phones, computers, iPods, video games, instant messaging, interactive multiplayer video games, virtual reality sites, Web social networks, and e-mail.

Electronic devices are defined as any object or process of human origin that can be used to convey media as books, films, mobiles, television, and the Internet. With respect to education, communication or play.

Adolescents, in particular, spend a significant amount of time in viewing and interacting with electronic devices in the form of TV, video games, music, and the Internet. Considering all of these sources together, adolescence spend more than six hours per day using media. Nearly half of that time is spent in watching TV, playing, or studying with computer. The remainder of the time is spent using other electronic media alone or in combination with TV.

The electronic media mainly consist of radio, television, and movies, and are actually classrooms without four walls. Media is an important source of shared images and messages relating to political and social context. Technology of media is an important part of student’s lives in the twenty-first century and play very important role in creating awareness related various aspects of life and personality as found. The world of electronic media, however, is changing dramatically. Television, which dominated the media world through the mid-1990s, now competes with cell phones, iPods, video games, instant messaging, interactive multiplayer video games, Web social networks, and e-mail. We learn skills, values and patterns of behavior from the media both directly and indirectly. There is no doubt that electronic media have a important influence on children from a very early age, and that it will continue to affect children's cognitive and social development. Electronic media activate and reinforce attitude and contribute significantly in the formation of new attitudes.

Effects of Technology on Adolescence

Technology and internet addiction in adolescence can have far reaching effects on the addict and his family. Adolescence with technology addiction can suffer from a variety of physical and psychological health problems.

General Effects

- Poor eating habits

- Increased obesity

- Attention problems in school, low attention span

- Lack of empathy

- Poor academic performance

- Social phobia

- Increased instances of cyberbullying

- Increased instances of substance abuse

- Growth issues

- Unable to control impulse to use the Internet/technology

- Feelings of happiness when using Internet or thinking about using the Internet

Negative effects of video games on adolescence's physical health, including obesity, video-induced seizures and postural, muscular and skeletal disorders, such as tendonitis, nerve compression, and carpal tunnel syndrome as well as delayed school achievement. However, these effects are not likely to occur for most adolescence. Parents should be most concerned about two things: the amount of time that adolescence play, and the content of the what to be play or watching.

In addition, symptoms associated with using mobile phones most commonly include headaches, earache, warmth sensations and sometimes also perceived concentration difficulties as well as fatigue However, over exposure to mobile phone use is not currently known to have major health effects. Another aspect of exposure is ergonomics. Musculoskeletal symptoms due to intensive texting on a mobile phone have been reported and techniques used for text entering have been studied in connection with developing musculoskeletal symptoms. The central factors appearing to explain high quantitative use were personal dependency, and demands for achievement and availability originating from domains of work,

To protect adolescence from harm, all health staff must have the competences to recognize adolescence maltreatment and to take effective action as appropriate to their role. They must also clearly understand their responsibilities, and should be supported by their employing organization. In addition, Parents have no idea about electronic devices effects on adolescence. So, parents need to understand that electronic devices can have an impact on everything they are concerned about with their adolescence's health and development, school performance, learning disabilities, sex, drugs, and aggressive behavior.

Preventive Measures

- Set strict time limit for phone use at home.

- Restrict the use of video games, television and other gadgets.

- Ask your teens to use only the family computer for all their online activities at home.

- Supervise the time your teens spend on the Internet.

- Spend time with your child to understand the source of his addiction. It is important for parents to know what makes their children find solace on the Internet.

- Talk to your teen’s teachers to understand problems at school, if any.

- Create positive environment at home. Your teen could be spending excessive time on the Internet to escape the problems at home. This excessive time spend on technology can easily turn into an addiction.

- Enforce no-Internet time at home or consequences for breaking rules about using technology at home.

Version History

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

The concerns and challenges of being a U.S. teen: What the data show

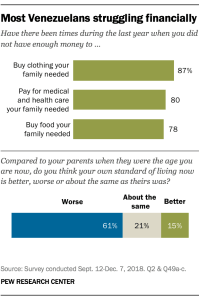

American teens have a lot on their minds. Substantial shares point to anxiety and depression, bullying, and drug and alcohol use (and abuse) as major problems among people their age, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of youth ages 13 to 17.

How common are these and other experiences among U.S. teens? We reviewed the most recent available data from government and academic researchers to find out:

Anxiety and depression

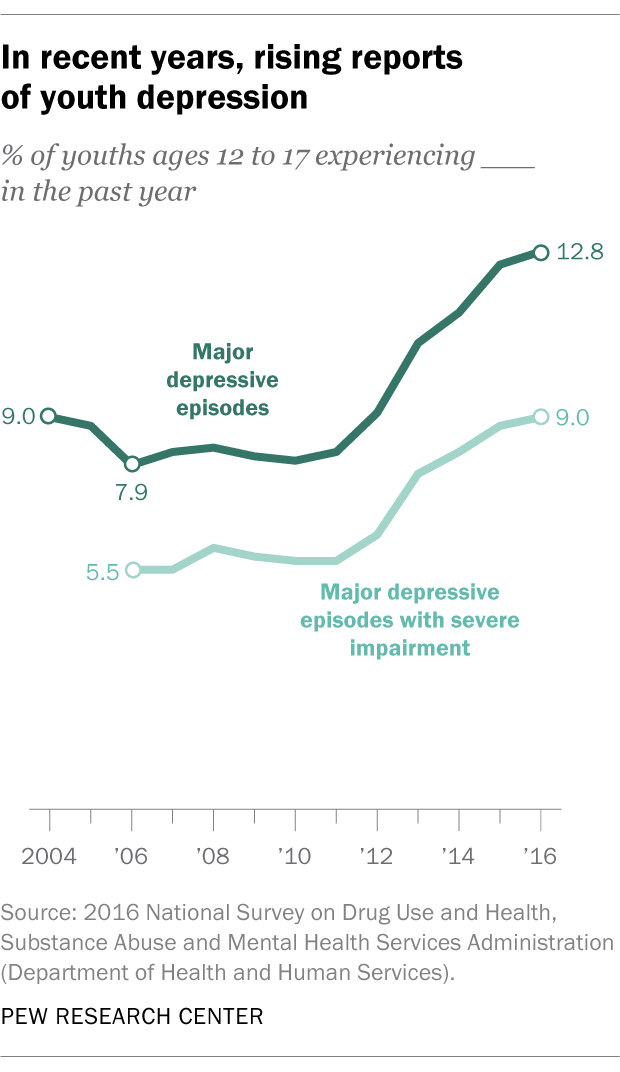

Serious mental stress is a fact of life for many American teens. In the new survey, seven-in-ten teens say anxiety and depression are major problems among their peers – a concern that’s shared by mental health researchers and clinicians .

Data on the prevalence of anxiety disorders is hard to come by among teens specifically. But 7% of youths ages 3 to 17 had such a condition in 2016-17, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health. Serious depression, meanwhile, has been on the rise among teens for the past several years, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health , an ongoing project of the federal Department of Health and Human Services. In 2016, 12.8% of youths ages 12 to 17 had experienced a major depressive episode in the past year, up from 8% as recently as 2010. For 9% of youths in 2016, their depression caused severe impairment. Fewer than half of youths with major depression said they’d been treated for it in the past year.

Alcohol and drugs

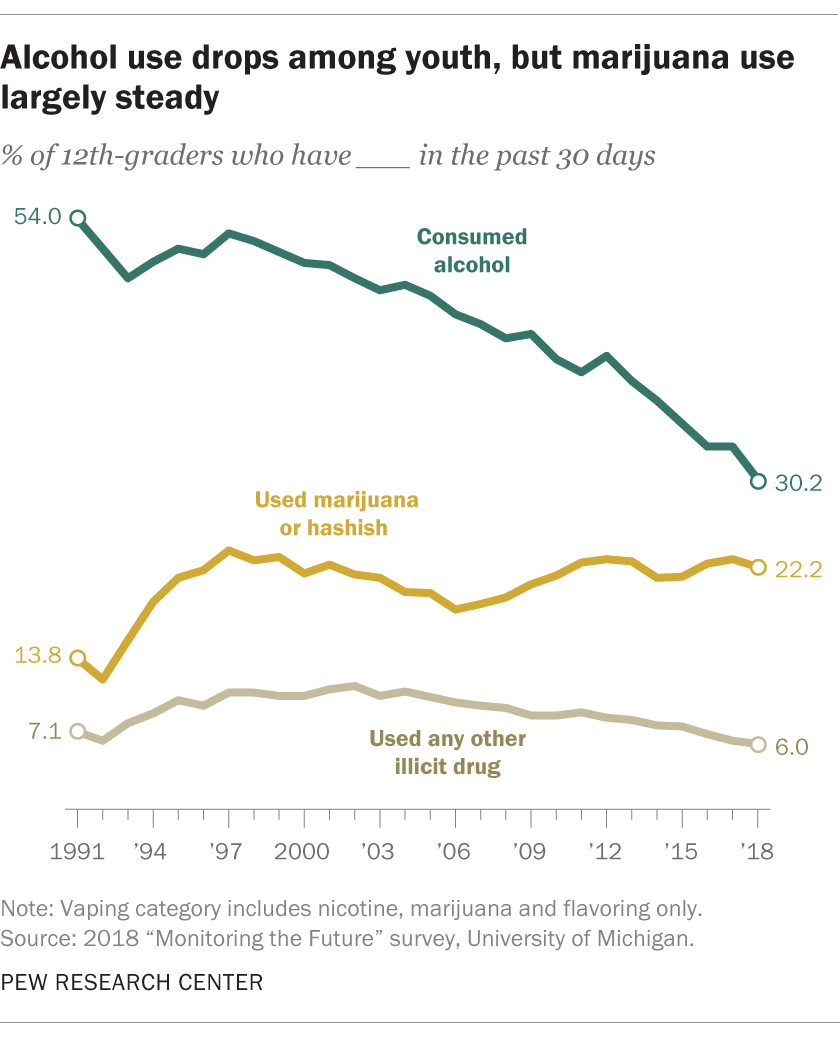

Anxiety and depression aren’t the only concerns for U.S. teens. Smaller though still substantial shares of teens in the Pew Research Center survey say drug addiction (51%) and alcohol consumption (45%) are major problems among their peers.

Fewer teens these days are drinking alcohol, according to the University of Michigan’s long-running Monitoring the Future survey, which tracks attitudes, values and behaviors of American youths, including their use of various legal and illicit substances. Last year, 30.2% of 12th-graders and 18.6% of 10th-graders had consumed alcohol in the past 30 days. Two decades earlier, those figures were 52% and 38.8%, respectively. (In the Center’s new survey, 16% of teens said they felt “a lot” or “some” pressure to drink alcohol.)

But the Michigan survey also found that, despite some ups and downs, use of marijuana (or its derivative, hashish) among 12th-graders is nearly as high as it was two decades ago. Last year, 22.2% reported using marijuana in the past 30 days, versus 22.8% in 1998. Past-month marijuana use among 10th-graders has declined a bit over that same period, from 18.7% to 16.7%, but is up from 14% in 2016.

Marijuana was by far the most commonly used drug among teens last year, as it has been for decades. While more than 10% of 12th-graders reported using some illicit drug other than marijuana in the late 1990s and early 2000s, that figure had fallen to 6% by last year.

The Michigan researchers noted that vaping, of both nicotine and marijuana, has jumped in popularity in the past few years. In 2018, 20.9% of 12th-graders and 16.1% of 10th-graders reported vaping nicotine in the past 30 days, about double the 2017 levels. By comparison, only 7.6% of 12th-graders and 4.2% of 10th-graders had smoked a cigarette in that time. And 7.5% of 12-graders and 7% of 10th-graders said they’d vaped marijuana within the past month, up from 4.9% and 4.3%, respectively, in 2017.

Bullying and cyberbullying

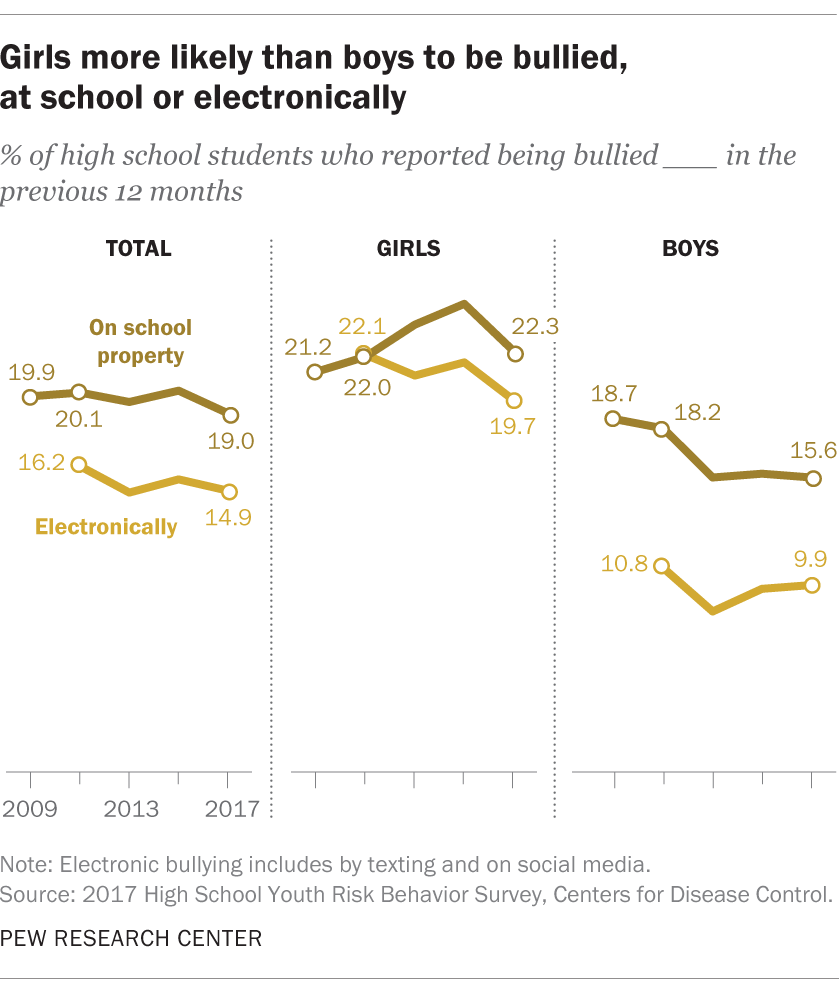

Issues of personal safety also are on U.S. teens’ minds. The Center’s survey found that 55% of teens said bullying was a major problem among their peers, while a third called gangs a major problem.

Bullying rates have held steady in recent years, according to a survey of youth risk behaviors by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About a fifth of high school students (19% in 2017) reported being bullied on school property in the past 12 months, and 14.9% said they’d experienced cyberbullying (via texts, social media or other digital means) in the previous year. In both cases, girls, younger students, and students who identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual were more likely to say they’d been bullied.

As for gangs, the share of students ages 12 to 18 who said gangs were present at their school fell from 20.1% in 2001 to 10.7% in 2015, according to a report on school safety from the federal departments of Education and Justice. Black and Hispanic students, as well as students in urban schools, were most likely to report the presence of gangs at school, but even for those groups the shares reporting this fell sharply between 2001 and 2015, the most recent year for which data are available.

Four-in-ten teens say poverty is a major problem among their peers, according to the Center’s new report. In 2017, about 2.2 million 15- to 17-year-olds (17.6%) were living in households with incomes below the poverty level – up from 16.3% in 2009, but down from 18.9% in 2014, based on our analysis of Census data. Black teens were more than twice as likely as white teens to live in households below the poverty level (30.4% versus 14%); however, the share of white teens in below-poverty-level households had risen from 2009 (when it was 12.1%), while the share of black teens in below-poverty-level households was almost unchanged.

Teen pregnancy

Far fewer U.S. teens are having to juggle adolescence and parenthood, as teen births continue their long-term decline . Among 15- to 19-year-olds, the overall birthrate has fallen by two-thirds since 1991 – from 61.8 live births per 1,000 women to 20.3 in 2016 , according to the CDC. All racial and ethnic groups have witnessed teen-birthrate declines of varying degrees: Among non-Hispanic blacks, for example, the rate fell from 118.2 live births per 1,000 in 1991 to 29.3 in 2016 .

- Age & Generations

- Drug Policy

- Health Policy

- Medicine & Health

- Teens & Youth

Drew DeSilver is a senior writer at Pew Research Center .

U.S. adults under 30 have different foreign policy priorities than older adults

Across asia, respect for elders is seen as necessary to be ‘truly’ buddhist, teens and video games today, as biden and trump seek reelection, who are the oldest – and youngest – current world leaders, how teens and parents approach screen time, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Psychology Adolescence

My Adolescent Experience and Development: A Reflection

Table of contents

Adolescent experience in my life, physical development, emotional development.

“Perhaps you looked in the mirror on a daily, or sometimes even hourly, basis as a young teenager to see whether you could detect anything different about your changing body. Preoccupation with one’s body image is strong through adolescence, it is especially acute during puberty, a time when adolescents are more dissatisfied with their bodies than in late adolescence.” (Santrock)

Social changes

- Arnett, J. J. (2015). Adolescence and emerging adulthood : A cultural approach. Pearson Education.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. WW Norton & Company.

- Gullotta, T. P., & Adams, G. R. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems: Evidence-based approaches to prevention and treatment. Springer.

- Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 83-110.

- Suler, J. R. (2018). Adolescent development. In Psychology of Adolescence (pp. 11-38). Springer.

- Rutter, M., & Smith, DJ (1995). Psychosocial disorders in young people: Time trends and their causes. John Wiley & Sons.

- American Psychological Association. (2019). APA handbook of the psychology of adolescence.

- Offer, D., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (1992). Debunking the myths of adolescence: Findings from recent research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(6), 1003-1014.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Confirmation Bias

- Operant Conditioning

- Jean Piaget

- Psychoanalysis

- Reward System

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Psychology Discussion

Essay on adolescence: top 5 essays | psychology.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Adolescence’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Adolescence’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Adolescence

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Meaning of Adolescence

- Essay on the Historical Perspectives of Adolescence

- Essay on the Developmental Model in Adolescence

- Essay on the Factors Influencing Development During Adolescence

- Essay on Developmental Psychopathology during the Period of Adolescence

Essay # 1. Meaning of Adolescence :

Adolescence is a time of rapid physiological and psychological change of intensive readjustment to the family, school, work and social life and of preparation for adult roles.

It starts with puberty and ends with the achievement of an adult work role. It usually begins between 11 and 16 years in boys and between 9 and 16 years in girls. Websters’ dictionary (1977) defines adolescence the ‘process of growing up’ or the ‘period of life from puberty to maturity’. Adolescence has been associated with an age span, varying from 10-13 as the starting age and 19-21 as the concluding age, depending on whose definition is being applied.

Essay # 2. Historical Perspectives of Adolescence :

The concept of adolescence was formally inducted in psychology from 1880. The definitive description of adolescence was given in the two volume work of Stanley Hall in 1904. Hall described adolescence as a period both of upheaval, suffering, passion and rebellion against adult authority and of physical, intellectual and social change.

Anna Freud, Mohr and Despres and Bios have independently affirmed adolescent regression, psychological upheaval, and turbulence as intrinsic to normal adolescence development. Margaret Mead believed adolescence as a ‘cultural invention’.

Albert Bandura said that children and adolescents imitate the behaviour of others especially influential adults ‘entertainment’ heroes and peers. Erikson elaborated the classic psychoanalytic views shifting the emphasis from biological imperatives of the entry into adolescence to focus on psychological challenges in making the transition from adolescence to adulthood (developmental model discussed below).

Piaget proposed a theory of cognitive development describing four major stages in intellectual development. Puberty is a universal process involving dramatic changes in size, shape and appearance. Tanner has described bodily changes of puberty into five stages. The enumeration of Tanner stages is given in Table 28.1.

The relationships between pubertal maturation and psychological development can be considered in two broad models,

(a) The ‘Direct Effect Model’ in which certain psychological effects are directly result of physiological sources,

(b) ‘Mediated Effects Model’ which proposes that the psychological effects of puberty are mediated by complex relations of intervening variables (such as the level of ego development) or are moderated by contexual factors (such as the socio-cultural and socialization practices). In recent days, this model is more favoured.

Essay # 3. Developmental Model in Adolescence :

Developmental theories of adolescence are:

(a) Cognitive development:

Jean Piaget described four distinct stages in the cognitive development from birth to adolescence.

(i) Sensory-motor stage:

Sensory-motor stage (from birth to 18 months) wherein the child acquires numerous basic skills with limited intellectual capacity and is primitive.

(ii) Preoperational or intuitive stage:

Preoperational or intuitive stage roughly starting at about 18 months and ending at 7 years, wherein the child learns to communicate and uses reason in an efficient way. However, he is still inclined to intuition rather than thinking out systematically.

(iii) Concrete-operations stage:

Concrete-operations stage (from 7 to 12 years) where the child becomes capable of appreciating the constancies and develops the concept of volume but thinking is still limited in some respects.

(iv) Formal operations stage:

Formal operations stage, (from 12 years through adulthood) in which the child develops the ability to ponder and deliberate on various alternatives, and begins to approach the problem situation in a truly systematic manner.

(b) Psychosocial development:

‘Identity’ and its precedents in development are the backbone of Erikson’s psychological developmental theory. Erikson’s theory is basically an amplification of Freud’s classical psychoanalytic theory of human development. However, Erikson lays more stress on the social than the biological features in the process of development. This theory is more humanistic and optimistic, and emphasizes the importance of ‘ego’ rather than ‘id’.

Erikson postulated eight stages of development, placing more importance on adolescence (Table 28.2).

His concept of identity crises has been recognised in all the countries faced with racial, national, personal and professional problems.

Psychodynamic Model :

Recent psychodynamic model focuses on adolescent development under various dimensions

Learning Model :

Learning theory has long played an important role in understanding of human behaviour. Three major learning paradigms are: classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning. The concepts of generalization and discrimination illustrate how learning theory can account for individuality of response styles and behaviour.

Phenomenological Model :

There are different schools of approach, including the phenomenological one.

Developmental Phases of Adolescence :

I. Early Adolescence :

Early adolescence is probably the most stressful of all developmental transitions. It is generally acknowledged that within the years of age from 11 to 15, a period of rapid and drastic biological change will be experienced.

The dominant themes of early adolescence are related to the endocrine changes of puberty. There are biological changes in virtually every system of the body, including height, facial contours, fat distribution, muscular development, mood changes, and energy levels.

Early adolescence is a time of sharpest possible discontinuity with the past.

There are two major psychosocial challenges that confront early adolescents:

(1) the transition from elementary to junior high school and

(2) the shift in role status from child to adolescent.

A useful distinction has been made between “hot” and “cold” cognitions. Hot cognitions are those that are highly charged with emotion and are involved in matters of perceived threat or in situations in which cherished goals or values are in conflict or jeopardy.

There is preoccupation with body image, with deep concerns about the normality, attractiveness, and vulnerability of the changing body. Superimposed are the challenges of entry into the new social world of the high school that pose new academic and personal challenges, especially regarding friendships. The early adolescents begin to search for new behaviours, values, and reference persons and to renegotiate relationships with parents. At this time they are particularly receptive to new ideas and risk taking.

II. Middle Adolescence :

It generally encompasses the ages 15 to 17.

The middle adolescents are capable of generalizations, abstract thinking and useful introspections that can be linked to experience. As a result there is less response simply to the novel, exotic, or contradictory aspects of the environment.

The anxious bodily preoccupations of early adolescence have greatly diminished. The power of peer pressure is lessened and more differentiated judgments can now be exercised in seeking and establishing close friendship ties.

The provocative rebelliousness of the early adolescent is no longer prominent. The middle adolescent is beginning to orient more to the larger society and to learn about and to question the workings of society, politics, and government.

III. Late Adolescence :

The ages represented are 17 years through the early 20s. It represents a definitive working through of the recurrent themes of body image, autonomy, achievement, intimacy, and sense of self that, when integrated, come to embody the sense of identity.

Although there may not be a work commitment, it is a time of thoughtful educational and vocational choices that will lead to eventual economic viability. The challenge of intimacy and the establishment of a stable, mature, committed intimate relationship is perceived as critical challenge.

Essay # 4. Factors Influencing Development during Adolescence:

I. Genetic Factors :

Leaving aside major diseases clearly transmitted by genes, such as Huntington’s chorea.

Genetic influences in psychiatry are characterised by:

(a) the inheritance of traits or tendencies rather than specific abnormalities,

(b) polygenic inheritance, that is to say more than one gene being influential,

(c) the concept of threshold effects (i.e., the presence of particular genes does not mean that the characteristic they represent will be exhibited).

II. Neurological Factors :

Brain Damage:

Various degrees of injury to the brain.

Mental Retardation:

Various degrees of intellectual deficit and general mental handicap.

This may or may not be associated with brain damage, mental handicap and psychiatric problems.

Neurological disorder:

Brain disorder, including neurodegenerative disorders.

III. Constitutional and Temperamental Factors :

If by personality, it is meant that more or less characteristic, coherent and enduring set of ways of thinking and behaving that develop through childhood and adolescence, then by constitution it means those inherited (genetic) and acquired physiological qualities that underlie personality.

IV. Family and Social Influences:

(a) Attachment, separation and loss:

Early experience of disrupted or discordant family relationships, or lack of parental affection, increases the incidence of emotional and personality problems later.

(b) Parental care and control:

It is the extremes of parental behaviour, e.g. excessive permissiveness, negligence, over-protectiveness and rigid discipline which tend to be associated with many of the problems in child and adolescent development.

The parental behaviours often associated with adolescent disturbance, and which when modified can help put things right include:

1. Lack of confidence about being adult and weakness at limit-setting;

2. Parental and marital distress;

3. Inability to provide the model of a reasonably competent adult who enjoys life;

4. Difficulty in maintaining appropriate roles and boundaries;

5. Difficulty in getting the balance right between being too protective and intrusive on the one hand or negligent and uninterested on the other;

6. Giving in too readily to adolescent demands, on the one hand, or not listening to the adolescent’s point of view on the other;

7. Becoming so upset by adolescent demands that the parent becomes childishly angry and vulnerable.

(c) Parental mental disorder:

In clinical practice, parental mental illness can have impact in three main ways:

(1) When it has been a feature of family life and interacting with the child’s problems for several years past;

(2) When it interferes with the developmental tasks of adolescence, for example when a depressed parent is thereby too vulnerable to the adolescent’s challenges; and

(3) When it interferes with treatment.

(d) Parental criminal behaviour

There is a strong association between delinquency in the child and criminality in the parent, and where both parents are criminal, the association is even stronger.

Again, poor parenting skills and family discord may be important linking factors. Modelling may be another factor.

(e) Family size and structure:

Children from large families (more than 5 children) tend to show a greater incidence of conduct problems, delinquency, lower verbal intelligence and lower reading attainment.

(f) Family patterns of behaviour:

Confused or conflicting communication in families, problems in resolving arguments or making decisions, and the generation of high levels of tension do seem to be associated with child disturbance in general.

(g) Adoption, fostering and institutional care:

There is an increased rate of psychiatric disorder among adopted children, with conduct disorder among adopted boys being most prominent.

Institutional care, the placement of children and adolescents in children’s homes, is associated with a higher rate of disturbance than in the general population.

(h) The effects of schools:

Wolkind and Rutter have listed features of schools which have a positive effect on their pupils: high expectations for work and behaviour; good models of behaviour from teachers; respect for the children, with opportunities for them to take responsibilities in the school; good discipline, with appropriate praise and encouragement and sparing use of punishment; a pleasant working environment with good teacher-pupil relationships; and a good organizational structure that enables staff to work together with agreed academic and other goals.

(i) Social and transcultural influences:

Life in inner city areas seems in general to increase the rate of behaviour problems compared with small towns and rural areas. Similar influences, plus and effects on the family of immigration and unemployment and prejudice affect adolescents. Unemployment among adolescents is associated with an increase in psychiatric problems.

The effects of film and television violence have now being widely studied. There seems to be a modelling and imitative effect, particularly in younger children and among adolescents who already show conduct problems and delinquency.

Assessment:

Assessment in adolescent psychiatry requires a far wider appraisal of who is concerned about what, and who is in a position to help, than the traditional clinical diagnosis can possibly provide. See Table 28.3.

Prevalence of Disorders in the Community :

The prevalence of adolescent disorder in the community varies from place to place and with age, and depends on the criteria used. The figures given vary between around 10 and 25%. The lower end of the range is associated with younger adolescents with recognised (i.e., known to adults) psychiatric problem in more rural or sub-urban areas, and the upper figures are associated with older adolescents, with industrial and inner-city areas and with the inclusion of problems not so evident to parents and teachers.

Disorders seen in clinical practice :

Table 28.4 is a composite picture of the types of disorder likely to be seen in general psychiatric service for adolescents, and is based on data drawn from several accounts.

(a) Clinical diagnostic categories (in approximate order of frequency) :

Mood disorders:

Emotional or mixed emotional/ contact disorders, or adult-type anxiety or depressive disorders, including obsessive compulsive phobic state.

Conduct Disorders:

Hysterical disorders e.g., with paralysis and serious self-neglect.

Problems of personality development with mood and/or conduct problems, including ‘borderline’ and schizoid personality disorders, and problems of sexual identity.

Schizophrenic, Schizoaffective and affective (manic-depressive) psychoses.

Brain disorder, including epilepsy, and neurodegenerative disorder.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, enuresis, encopresis, and tics

(b) Changes in prevalence with age and sex:

The overall pattern seems to be a gradually increasing prevalence of psychiatric disorder from around 10% in children through 10 to 15% in mid- adolescence to around 20% in adulthood although some studies report a peak of about 20% being reached in adolescence.

In adolescence, enuresis and encopresis are less common than in earlier childhood. Hyperactivity presents less often, but children who have been hyperactive in earlier childhood sometimes present in adolescence with behavioural and other social problems.

In earlier childhood, equal numbers of girls and boys are affected by emotional disorders. In adolescence, however, as in adult life, more girls than boys are affected.

Delinquency increases markedly in adolescence and declines from early adulthood onwards.

Essay # 5. Developmental Psychopathology during the Period of Adolescence :

(a) Mood Fluctuations and Misery :

The general observation that adolescents experience a greater fluctuation of mood that adults has been demonstrated rather consistently. The feelings of transient misery and sadness reported by adolescents can be explained by several bases.

The Offer Self-image Questionnaire, administered to thousands of adolescents from 1962-1980, showed a significant upward shift of scores of depressive mood from the 1960’s to the 1970’s for both boys and girls.

Although relationships with parents may remain intact, the security experienced by identifying with the idealized parental image is sacrificed as the youth moves toward development of a separate identity.

Eventually, with the synthesis of these different value systems, the adolescent’s behaviour takes on an increasingly external and internal consistency. The wide array of conflicting societal values in regard to a youth’s engaging in sex becoming pregnant, having an abortion, bearing a child, or participating in homosexual behaviour provides numerous opportunities for remorse.

An additional factor that may draw the adolescent to a sexual relationship inspite of conflicting values is the relative emotional void produced as some distance is gained from the parent.

Among the adolescents these kinds of temporary setbacks may lead to an array of behaviours that erroneously have been termed clinical depression. These include a hypersensitivity and irritability, with a proneness to overreact to criticism. At times the adolescent may “tune out” temporarily and withdraw into a position of apathy and indifference.