Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

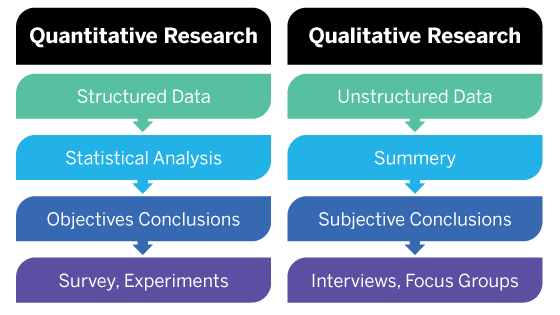

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

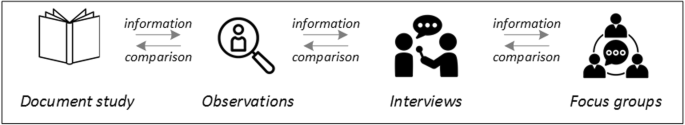

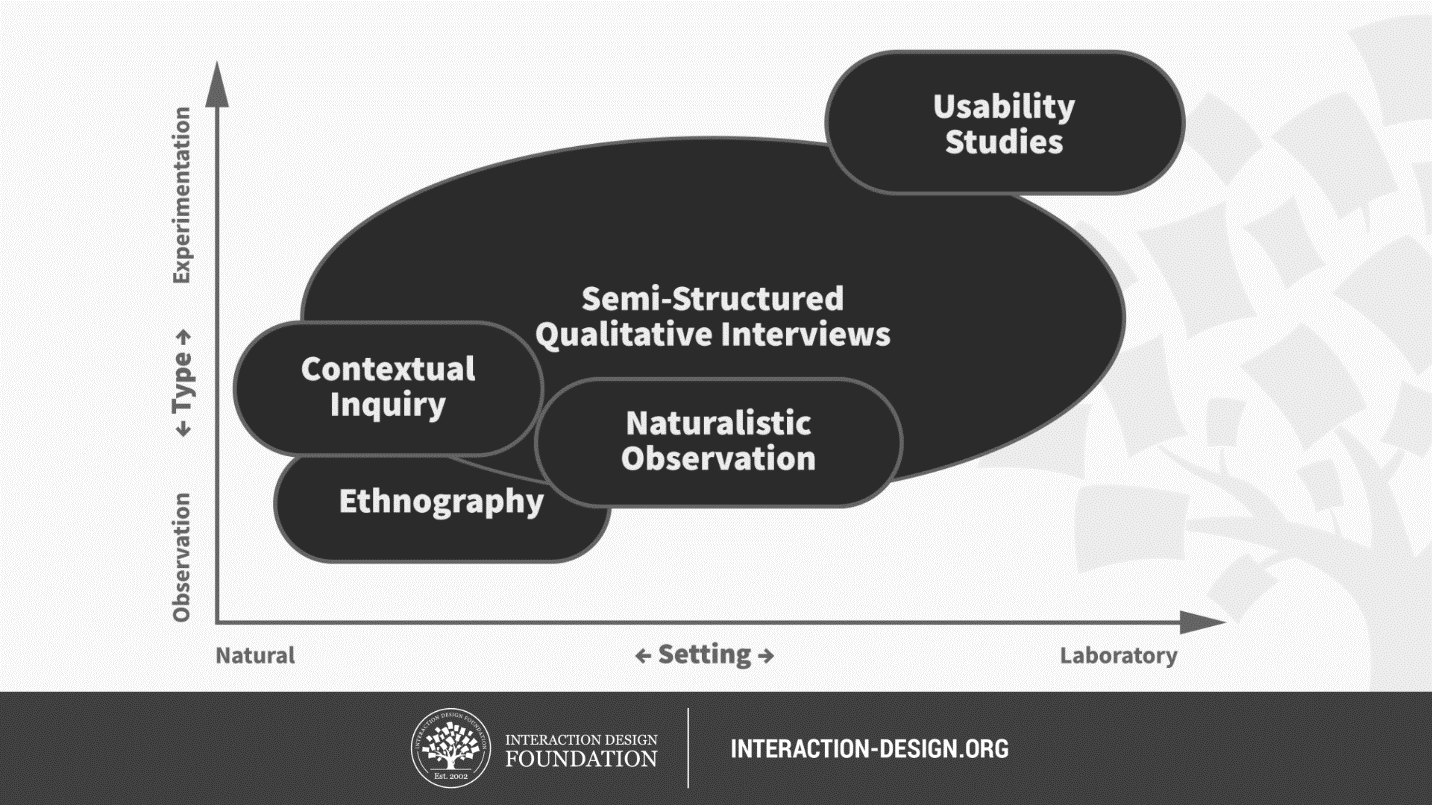

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

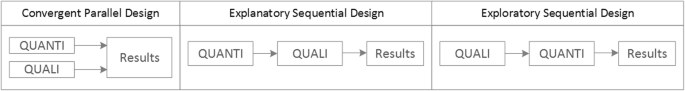

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 6, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

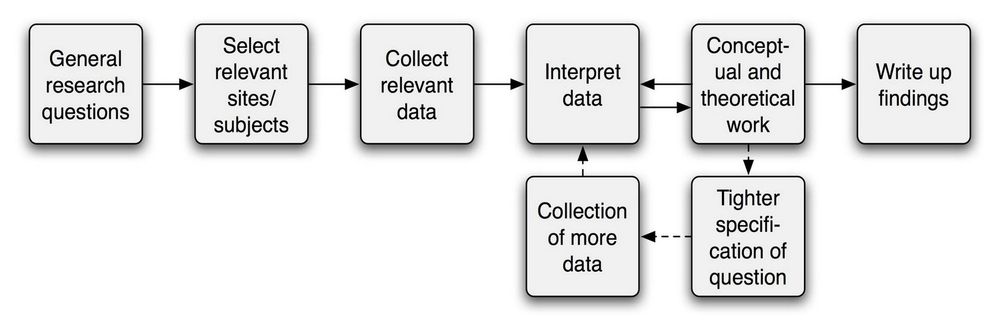

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

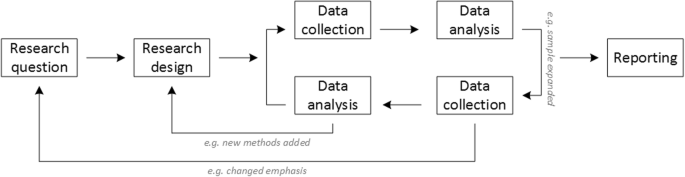

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research: Characteristics, Design, Methods & Examples

Lauren McCall

MSc Health Psychology Graduate

MSc, Health Psychology, University of Nottingham

Lauren obtained an MSc in Health Psychology from The University of Nottingham with a distinction classification.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on gathering and analyzing non-numerical data to gain a deeper understanding of human behavior, experiences, and perspectives.

It aims to explore the “why” and “how” of a phenomenon rather than the “what,” “where,” and “when” typically addressed by quantitative research.

Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on gathering and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis, qualitative research involves researchers interpreting data to identify themes, patterns, and meanings.

Qualitative research can be used to:

- Gain deep contextual understandings of the subjective social reality of individuals

- To answer questions about experience and meaning from the participant’s perspective

- To design hypotheses, theory must be researched using qualitative methods to determine what is important before research can begin.

Examples of qualitative research questions include:

- How does stress influence young adults’ behavior?

- What factors influence students’ school attendance rates in developed countries?

- How do adults interpret binge drinking in the UK?

- What are the psychological impacts of cervical cancer screening in women?

- How can mental health lessons be integrated into the school curriculum?

Characteristics

Naturalistic setting.

Individuals are studied in their natural setting to gain a deeper understanding of how people experience the world. This enables the researcher to understand a phenomenon close to how participants experience it.

Naturalistic settings provide valuable contextual information to help researchers better understand and interpret the data they collect.

The environment, social interactions, and cultural factors can all influence behavior and experiences, and these elements are more easily observed in real-world settings.

Reality is socially constructed

Qualitative research aims to understand how participants make meaning of their experiences – individually or in social contexts. It assumes there is no objective reality and that the social world is interpreted (Yilmaz, 2013).

The primacy of subject matter

The primary aim of qualitative research is to understand the perspectives, experiences, and beliefs of individuals who have experienced the phenomenon selected for research rather than the average experiences of groups of people (Minichiello, 1990).

An in-depth understanding is attained since qualitative techniques allow participants to freely disclose their experiences, thoughts, and feelings without constraint (Tenny et al., 2022).

Variables are complex, interwoven, and difficult to measure

Factors such as experiences, behaviors, and attitudes are complex and interwoven, so they cannot be reduced to isolated variables , making them difficult to measure quantitatively.

However, a qualitative approach enables participants to describe what, why, or how they were thinking/ feeling during a phenomenon being studied (Yilmaz, 2013).

Emic (insider’s point of view)

The phenomenon being studied is centered on the participants’ point of view (Minichiello, 1990).

Emic is used to describe how participants interact, communicate, and behave in the research setting (Scarduzio, 2017).

Interpretive analysis

In qualitative research, interpretive analysis is crucial in making sense of the collected data.

This process involves examining the raw data, such as interview transcripts, field notes, or documents, and identifying the underlying themes, patterns, and meanings that emerge from the participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Collecting Qualitative Data

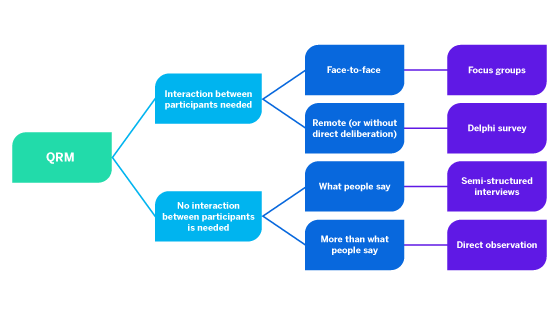

There are four main research design methods used to collect qualitative data: observations, interviews, focus groups, and ethnography.

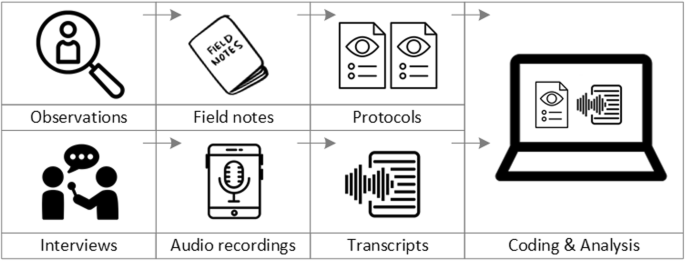

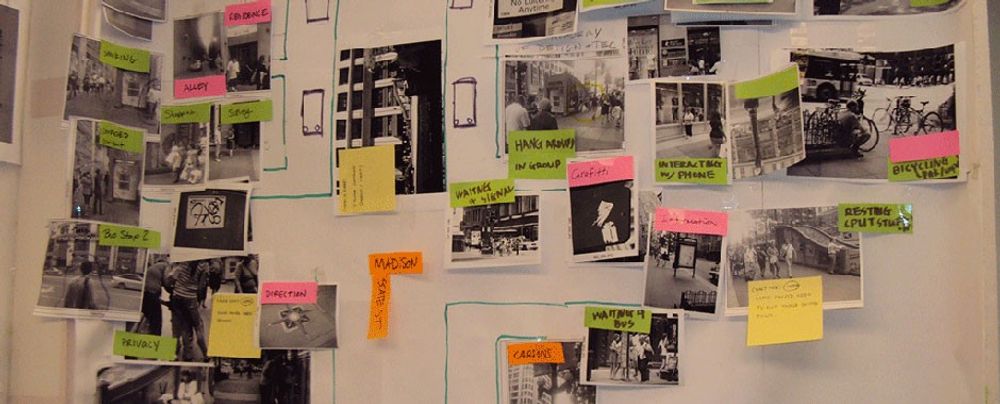

Observations

This method involves watching and recording phenomena as they occur in nature. Observation can be divided into two types: participant and non-participant observation.

In participant observation, the researcher actively participates in the situation/events being observed.

In non-participant observation, the researcher is not an active part of the observation and tries not to influence the behaviors they are observing (Busetto et al., 2020).

Observations can be covert (participants are unaware that a researcher is observing them) or overt (participants are aware of the researcher’s presence and know they are being observed).

However, awareness of an observer’s presence may influence participants’ behavior.

Interviews give researchers a window into the world of a participant by seeking their account of an event, situation, or phenomenon. They are usually conducted on a one-to-one basis and can be distinguished according to the level at which they are structured (Punch, 2013).

Structured interviews involve predetermined questions and sequences to ensure replicability and comparability. However, they are unable to explore emerging issues.

Informal interviews consist of spontaneous, casual conversations which are closer to the truth of a phenomenon. However, information is gathered using quick notes made by the researcher and is therefore subject to recall bias.

Semi-structured interviews have a flexible structure, phrasing, and placement so emerging issues can be explored (Denny & Weckesser, 2022).

The use of probing questions and clarification can lead to a detailed understanding, but semi-structured interviews can be time-consuming and subject to interviewer bias.

Focus groups

Similar to interviews, focus groups elicit a rich and detailed account of an experience. However, focus groups are more dynamic since participants with shared characteristics construct this account together (Denny & Weckesser, 2022).

A shared narrative is built between participants to capture a group experience shaped by a shared context.

The researcher takes on the role of a moderator, who will establish ground rules and guide the discussion by following a topic guide to focus the group discussions.

Typically, focus groups have 4-10 participants as a discussion can be difficult to facilitate with more than this, and this number allows everyone the time to speak.

Ethnography

Ethnography is a methodology used to study a group of people’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment (Reeves et al., 2008).

Data are collected using methods such as observations, field notes, or structured/ unstructured interviews.

The aim of ethnography is to provide detailed, holistic insights into people’s behavior and perspectives within their natural setting. In order to achieve this, researchers immerse themselves in a community or organization.

Due to the flexibility and real-world focus of ethnography, researchers are able to gather an in-depth, nuanced understanding of people’s experiences, knowledge and perspectives that are influenced by culture and society.

In order to develop a representative picture of a particular culture/ context, researchers must conduct extensive field work.

This can be time-consuming as researchers may need to immerse themselves into a community/ culture for a few days, or possibly a few years.

Qualitative Data Analysis Methods

Different methods can be used for analyzing qualitative data. The researcher chooses based on the objectives of their study.

The researcher plays a key role in the interpretation of data, making decisions about the coding, theming, decontextualizing, and recontextualizing of data (Starks & Trinidad, 2007).

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967 (Glaser & Strauss, 2017).

This methodology aims to develop theories (rather than test hypotheses) that explain a social process, action, or interaction (Petty et al., 2012). To inform the developing theory, data collection and analysis run simultaneously.

There are three key types of coding used in grounded theory: initial (open), intermediate (axial), and advanced (selective) coding.

Throughout the analysis, memos should be created to document methodological and theoretical ideas about the data. Data should be collected and analyzed until data saturation is reached and a theory is developed.

Content analysis

Content analysis was first used in the early twentieth century to analyze textual materials such as newspapers and political speeches.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify and analyze the presence and patterns of themes, concepts, or words in data (Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

This research method can be used to analyze data in different formats, which can be written, oral, or visual.

The goal of content analysis is to develop themes that capture the underlying meanings of data (Schreier, 2012).

Qualitative content analysis can be used to validate existing theories, support the development of new models and theories, and provide in-depth descriptions of particular settings or experiences.

The following six steps provide a guideline for how to conduct qualitative content analysis.

- Define a Research Question : To start content analysis, a clear research question should be developed.

- Identify and Collect Data : Establish the inclusion criteria for your data. Find the relevant sources to analyze.

- Define the Unit or Theme of Analysis : Categorize the content into themes. Themes can be a word, phrase, or sentence.

- Develop Rules for Coding your Data : Define a set of coding rules to ensure that all data are coded consistently.

- Code the Data : Follow the coding rules to categorize data into themes.

- Analyze the Results and Draw Conclusions : Examine the data to identify patterns and draw conclusions in relation to your research question.

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis is a research method used to study written/ spoken language in relation to its social context (Wood & Kroger, 2000).

In discourse analysis, the researcher interprets details of language materials and the context in which it is situated.

Discourse analysis aims to understand the functions of language (how language is used in real life) and how meaning is conveyed by language in different contexts. Researchers use discourse analysis to investigate social groups and how language is used to achieve specific communication goals.

Different methods of discourse analysis can be used depending on the aims and objectives of a study. However, the following steps provide a guideline on how to conduct discourse analysis.

- Define the Research Question : Develop a relevant research question to frame the analysis.

- Gather Data and Establish the Context : Collect research materials (e.g., interview transcripts, documents). Gather factual details and review the literature to construct a theory about the social and historical context of your study.

- Analyze the Content : Closely examine various components of the text, such as the vocabulary, sentences, paragraphs, and structure of the text. Identify patterns relevant to the research question to create codes, then group these into themes.

- Review the Results : Reflect on the findings to examine the function of the language, and the meaning and context of the discourse.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a method used to identify, interpret, and report patterns in data, such as commonalities or contrasts.

Although the origin of thematic analysis can be traced back to the early twentieth century, understanding and clarity of thematic analysis is attributed to Braun and Clarke (2006).

Thematic analysis aims to develop themes (patterns of meaning) across a dataset to address a research question.

In thematic analysis, qualitative data is gathered using techniques such as interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires. Audio recordings are transcribed. The dataset is then explored and interpreted by a researcher to identify patterns.

This occurs through the rigorous process of data familiarisation, coding, theme development, and revision. These identified patterns provide a summary of the dataset and can be used to address a research question.

Themes are developed by exploring the implicit and explicit meanings within the data. Two different approaches are used to generate themes: inductive and deductive.

An inductive approach allows themes to emerge from the data. In contrast, a deductive approach uses existing theories or knowledge to apply preconceived ideas to the data.

Phases of Thematic Analysis

Braun and Clarke (2006) provide a guide of the six phases of thematic analysis. These phases can be applied flexibly to fit research questions and data.

| Phase | |

|---|---|

| 1. Gather and transcribe data | Gather raw data, for example interviews or focus groups, and transcribe audio recordings fully |

| 2. Familiarization with data | Read and reread all your data from beginning to end; note down initial ideas |

| 3. Create initial codes | Start identifying preliminary codes which highlight important features of the data and may be relevant to the research question |

| 4. Create new codes which encapsulate potential themes | Review initial codes and explore any similarities, differences, or contradictions to uncover underlying themes; create a map to visualize identified themes |

| 5. Take a break then return to the data | Take a break and then return later to review themes |

| 6. Evaluate themes for good fit | Last opportunity for analysis; check themes are supported and saturated with data |

Template analysis

Template analysis refers to a specific method of thematic analysis which uses hierarchical coding (Brooks et al., 2014).

Template analysis is used to analyze textual data, for example, interview transcripts or open-ended responses on a written questionnaire.

To conduct template analysis, a coding template must be developed (usually from a subset of the data) and subsequently revised and refined. This template represents the themes identified by researchers as important in the dataset.

Codes are ordered hierarchically within the template, with the highest-level codes demonstrating overarching themes in the data and lower-level codes representing constituent themes with a narrower focus.

A guideline for the main procedural steps for conducting template analysis is outlined below.

- Familiarization with the Data : Read (and reread) the dataset in full. Engage, reflect, and take notes on data that may be relevant to the research question.

- Preliminary Coding : Identify initial codes using guidance from the a priori codes, identified before the analysis as likely to be beneficial and relevant to the analysis.

- Organize Themes : Organize themes into meaningful clusters. Consider the relationships between the themes both within and between clusters.

- Produce an Initial Template : Develop an initial template. This may be based on a subset of the data.

- Apply and Develop the Template : Apply the initial template to further data and make any necessary modifications. Refinements of the template may include adding themes, removing themes, or changing the scope/title of themes.

- Finalize Template : Finalize the template, then apply it to the entire dataset.

Frame analysis

Frame analysis is a comparative form of thematic analysis which systematically analyzes data using a matrix output.

Ritchie and Spencer (1994) developed this set of techniques to analyze qualitative data in applied policy research. Frame analysis aims to generate theory from data.

Frame analysis encourages researchers to organize and manage their data using summarization.

This results in a flexible and unique matrix output, in which individual participants (or cases) are represented by rows and themes are represented by columns.

Each intersecting cell is used to summarize findings relating to the corresponding participant and theme.

Frame analysis has five distinct phases which are interrelated, forming a methodical and rigorous framework.

- Familiarization with the Data : Familiarize yourself with all the transcripts. Immerse yourself in the details of each transcript and start to note recurring themes.

- Develop a Theoretical Framework : Identify recurrent/ important themes and add them to a chart. Provide a framework/ structure for the analysis.

- Indexing : Apply the framework systematically to the entire study data.

- Summarize Data in Analytical Framework : Reduce the data into brief summaries of participants’ accounts.

- Mapping and Interpretation : Compare themes and subthemes and check against the original transcripts. Group the data into categories and provide an explanation for them.

Preventing Bias in Qualitative Research

To evaluate qualitative studies, the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) checklist for qualitative studies can be used to ensure all aspects of a study have been considered (CASP, 2018).

The quality of research can be enhanced and assessed using criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, co-coding, and member-checking.

Co-coding

Relying on only one researcher to interpret rich and complex data may risk key insights and alternative viewpoints being missed. Therefore, coding is often performed by multiple researchers.

A common strategy must be defined at the beginning of the coding process (Busetto et al., 2020). This includes establishing a useful coding list and finding a common definition of individual codes.

Transcripts are initially coded independently by researchers and then compared and consolidated to minimize error or bias and to bring confirmation of findings.

Member checking

Member checking (or respondent validation) involves checking back with participants to see if the research resonates with their experiences (Russell & Gregory, 2003).

Data can be returned to participants after data collection or when results are first available. For example, participants may be provided with their interview transcript and asked to verify whether this is a complete and accurate representation of their views.

Participants may then clarify or elaborate on their responses to ensure they align with their views (Shenton, 2004).

This feedback becomes part of data collection and ensures accurate descriptions/ interpretations of phenomena (Mays & Pope, 2000).

Reflexivity in qualitative research

Reflexivity typically involves examining your own judgments, practices, and belief systems during data collection and analysis. It aims to identify any personal beliefs which may affect the research.

Reflexivity is essential in qualitative research to ensure methodological transparency and complete reporting. This enables readers to understand how the interaction between the researcher and participant shapes the data.

Depending on the research question and population being researched, factors that need to be considered include the experience of the researcher, how the contact was established and maintained, age, gender, and ethnicity.

These details are important because, in qualitative research, the researcher is a dynamic part of the research process and actively influences the outcome of the research (Boeije, 2014).

Reflexivity Example

Who you are and your characteristics influence how you collect and analyze data. Here is an example of a reflexivity statement for research on smoking. I am a 30-year-old white female from a middle-class background. I live in the southwest of England and have been educated to master’s level. I have been involved in two research projects on oral health. I have never smoked, but I have witnessed how smoking can cause ill health from my volunteering in a smoking cessation clinic. My research aspirations are to help to develop interventions to help smokers quit.

Establishing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

Trustworthiness is a concept used to assess the quality and rigor of qualitative research. Four criteria are used to assess a study’s trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

1. Credibility in Qualitative Research

Credibility refers to how accurately the results represent the reality and viewpoints of the participants.

To establish credibility in research, participants’ views and the researcher’s representation of their views need to align (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

To increase the credibility of findings, researchers may use data source triangulation, investigator triangulation, peer debriefing, or member checking (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

2. Transferability in Qualitative Research

Transferability refers to how generalizable the findings are: whether the findings may be applied to another context, setting, or group (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

Transferability can be enhanced by giving thorough and in-depth descriptions of the research setting, sample, and methods (Nowell et al., 2017).

3. Dependability in Qualitative Research

Dependability is the extent to which the study could be replicated under similar conditions and the findings would be consistent.

Researchers can establish dependability using methods such as audit trails so readers can see the research process is logical and traceable (Koch, 1994).

4. Confirmability in Qualitative Research

Confirmability is concerned with establishing that there is a clear link between the researcher’s interpretations/ findings and the data.

Researchers can achieve confirmability by demonstrating how conclusions and interpretations were arrived at (Nowell et al., 2017).

This enables readers to understand the reasoning behind the decisions made.

Audit Trails in Qualitative Research

An audit trail provides evidence of the decisions made by the researcher regarding theory, research design, and data collection, as well as the steps they have chosen to manage, analyze, and report data.

The researcher must provide a clear rationale to demonstrate how conclusions were reached in their study.

A clear description of the research path must be provided to enable readers to trace through the researcher’s logic (Halpren, 1983).

Researchers should maintain records of the raw data, field notes, transcripts, and a reflective journal in order to provide a clear audit trail.

Discovery of unexpected data

Open-ended questions in qualitative research mean the researcher can probe an interview topic and enable the participant to elaborate on responses in an unrestricted manner.

This allows unexpected data to emerge, which can lead to further research into that topic.

The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps generate hypotheses that can be tested quantitatively (Busetto et al., 2020).

Flexibility

Data collection and analysis can be modified and adapted to take the research in a different direction if new ideas or patterns emerge in the data.

This enables researchers to investigate new opportunities while firmly maintaining their research goals.

Naturalistic settings

The behaviors of participants are recorded in real-world settings. Studies that use real-world settings have high ecological validity since participants behave more authentically.

Limitations

Time-consuming .

Qualitative research results in large amounts of data which often need to be transcribed and analyzed manually.

Even when software is used, transcription can be inaccurate, and using software for analysis can result in many codes which need to be condensed into themes.

Subjectivity

The researcher has an integral role in collecting and interpreting qualitative data. Therefore, the conclusions reached are from their perspective and experience.

Consequently, interpretations of data from another researcher may vary greatly.

Limited generalizability

The aim of qualitative research is to provide a detailed, contextualized understanding of an aspect of the human experience from a relatively small sample size.

Despite rigorous analysis procedures, conclusions drawn cannot be generalized to the wider population since data may be biased or unrepresentative.

Therefore, results are only applicable to a small group of the population.

While individual qualitative studies are often limited in their generalizability due to factors such as sample size and context, metasynthesis enables researchers to synthesize findings from multiple studies, potentially leading to more generalizable conclusions.

By integrating findings from studies conducted in diverse settings and with different populations, metasynthesis can provide broader insights into the phenomenon of interest.

Extraneous variables

Qualitative research is often conducted in real-world settings. This may cause results to be unreliable since extraneous variables may affect the data, for example:

- Situational variables : different environmental conditions may influence participants’ behavior in a study. The random variation in factors (such as noise or lighting) may be difficult to control in real-world settings.

- Participant characteristics : this includes any characteristics that may influence how a participant answers/ behaves in a study. This may include a participant’s mood, gender, age, ethnicity, sexual identity, IQ, etc.

- Experimenter effect : experimenter effect refers to how a researcher’s unintentional influence can change the outcome of a study. This occurs when (i) their interactions with participants unintentionally change participants’ behaviors or (ii) due to errors in observation, interpretation, or analysis.

What sample size should qualitative research be?

The sample size for qualitative studies has been recommended to include a minimum of 12 participants to reach data saturation (Braun, 2013).

Are surveys qualitative or quantitative?

Surveys can be used to gather information from a sample qualitatively or quantitatively. Qualitative surveys use open-ended questions to gather detailed information from a large sample using free text responses.

The use of open-ended questions allows for unrestricted responses where participants use their own words, enabling the collection of more in-depth information than closed-ended questions.

In contrast, quantitative surveys consist of closed-ended questions with multiple-choice answer options. Quantitative surveys are ideal to gather a statistical representation of a population.

What are the ethical considerations of qualitative research?

Before conducting a study, you must think about any risks that could occur and take steps to prevent them. Participant Protection : Researchers must protect participants from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend, or harm participants. Transparency : Researchers are obligated to clearly communicate how they will collect, store, analyze, use, and share the data. Confidentiality : You need to consider how to maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ data.

What is triangulation in qualitative research?

Triangulation refers to the use of several approaches in a study to comprehensively understand phenomena. This method helps to increase the validity and credibility of research findings.

Types of triangulation include method triangulation (using multiple methods to gather data); investigator triangulation (multiple researchers for collecting/ analyzing data), theory triangulation (comparing several theoretical perspectives to explain a phenomenon), and data source triangulation (using data from various times, locations, and people; Carter et al., 2014).

Why is qualitative research important?

Qualitative research allows researchers to describe and explain the social world. The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps to generate hypotheses that can then be tested quantitatively.

In qualitative research, participants are able to express their thoughts, experiences, and feelings without constraint.

Additionally, researchers are able to follow up on participants’ answers in real-time, generating valuable discussion around a topic. This enables researchers to gain a nuanced understanding of phenomena which is difficult to attain using quantitative methods.

What is coding data in qualitative research?

Coding data is a qualitative data analysis strategy in which a section of text is assigned with a label that describes its content.

These labels may be words or phrases which represent important (and recurring) patterns in the data.

This process enables researchers to identify related content across the dataset. Codes can then be used to group similar types of data to generate themes.

What is the difference between qualitative and quantitative research?

Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data in order to understand experiences and meanings from the participant’s perspective.

This can provide rich, in-depth insights on complicated phenomena. Qualitative data may be collected using interviews, focus groups, or observations.

In contrast, quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to measure the frequency, magnitude, or relationships of variables. This can provide objective and reliable evidence that can be generalized to the wider population.

Quantitative data may be collected using closed-ended questionnaires or experiments.

What is trustworthiness in qualitative research?

Trustworthiness is a concept used to assess the quality and rigor of qualitative research. Four criteria are used to assess a study’s trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility refers to how accurately the results represent the reality and viewpoints of the participants. Transferability refers to whether the findings may be applied to another context, setting, or group.

Dependability is the extent to which the findings are consistent and reliable. Confirmability refers to the objectivity of findings (not influenced by the bias or assumptions of researchers).

What is data saturation in qualitative research?

Data saturation is a methodological principle used to guide the sample size of a qualitative research study.

Data saturation is proposed as a necessary methodological component in qualitative research (Saunders et al., 2018) as it is a vital criterion for discontinuing data collection and/or analysis.

The intention of data saturation is to find “no new data, no new themes, no new coding, and ability to replicate the study” (Guest et al., 2006). Therefore, enough data has been gathered to make conclusions.

Why is sampling in qualitative research important?

In quantitative research, large sample sizes are used to provide statistically significant quantitative estimates.

This is because quantitative research aims to provide generalizable conclusions that represent populations.

However, the aim of sampling in qualitative research is to gather data that will help the researcher understand the depth, complexity, variation, or context of a phenomenon. The small sample sizes in qualitative studies support the depth of case-oriented analysis.

What is narrative analysis?

Narrative analysis is a qualitative research method used to understand how individuals create stories from their personal experiences.

There is an emphasis on understanding the context in which a narrative is constructed, recognizing the influence of historical, cultural, and social factors on storytelling.

Researchers can use different methods together to explore a research question.

Some narrative researchers focus on the content of what is said, using thematic narrative analysis, while others focus on the structure, such as holistic-form or categorical-form structural narrative analysis. Others focus on how the narrative is produced and performed.

Boeije, H. (2014). Analysis in qualitative research. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology , 3 (2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2014). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 12 (2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological research and practice , 2 (1), 14-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology nursing forum , 41 (5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of a Qualitative research. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Accessed: March 15 2023

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Successful Qualitative Research , 1-400.

Denny, E., & Weckesser, A. (2022). How to do qualitative research?: Qualitative research methods. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology , 129 (7), 1166-1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17150

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). The discovery of grounded theory. The Discovery of Grounded Theory , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206-1

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18 (1), 59-82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

Halpren, E. S. (1983). Auditing naturalistic inquiries: The development and application of a model (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Bloomington.

Hammarberg, K., Kirkman, M., & de Lacey, S. (2016). Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Human Reproduction , 31 (3), 498–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334

Koch, T. (1994). Establishing rigour in qualitative research: The decision trail. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19, 976–986. doi:10.1111/ j.1365-2648.1994.tb01177.x

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Petty, N. J., Thomson, O. P., & Stew, G. (2012). Ready for a paradigm shift? part 2: Introducing qualitative research methodologies and methods. Manual Therapy , 17 (5), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.03.004

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage

Reeves, S., Kuper, A., & Hodges, B. D. (2008). Qualitative research methodologies: Ethnography. BMJ , 337 (aug07 3). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1020

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity , 52 (4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Scarduzio, J. A. (2017). Emic approach to qualitative research. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 1–2 . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0082

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice / Margrit Schreier.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative health research , 17 (10), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

Tenny, S., Brannan, J. M., & Brannan, G. D. (2022). Qualitative Study. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Tobin, G. A., & Begley, C. M. (2004). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 388–396. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences , 15 (3), 398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Wood L. A., Kroger R. O. (2000). Doing discourse analysis: Methods for studying action in talk and text. Sage.

Yilmaz, K. (2013). Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. European journal of education , 48 (2), 311-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12014

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 30 January 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analysing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, and history.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organisation?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography, action research, phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasise different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organisations to understand their cultures. | |

| Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. | |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves ‘instruments’ in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analysing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organise your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorise your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analysing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasise different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorise common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility