- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Types of Literature Review — A Guide for Researchers

Table of Contents

Researchers often face challenges when choosing the appropriate type of literature review for their study. Regardless of the type of research design and the topic of a research problem , they encounter numerous queries, including:

What is the right type of literature review my study demands?

- How do we gather the data?

- How to conduct one?

- How reliable are the review findings?

- How do we employ them in our research? And the list goes on.

If you’re also dealing with such a hefty questionnaire, this article is of help. Read through this piece of guide to get an exhaustive understanding of the different types of literature reviews and their step-by-step methodologies along with a dash of pros and cons discussed.

Heading from scratch!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review provides a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge on a particular topic, which is quintessential to any research project. Researchers employ various literature reviews based on their research goals and methodologies. The review process involves assembling, critically evaluating, and synthesizing existing scientific publications relevant to the research question at hand. It serves multiple purposes, including identifying gaps in existing literature, providing theoretical background, and supporting the rationale for a research study.

What is the importance of a Literature review in research?

Literature review in research serves several key purposes, including:

- Background of the study: Provides proper context for the research. It helps researchers understand the historical development, theoretical perspectives, and key debates related to their research topic.

- Identification of research gaps: By reviewing existing literature, researchers can identify gaps or inconsistencies in knowledge, paving the way for new research questions and hypotheses relevant to their study.

- Theoretical framework development: Facilitates the development of theoretical frameworks by cultivating diverse perspectives and empirical findings. It helps researchers refine their conceptualizations and theoretical models.

- Methodological guidance: Offers methodological guidance by highlighting the documented research methods and techniques used in previous studies. It assists researchers in selecting appropriate research designs, data collection methods, and analytical tools.

- Quality assurance and upholding academic integrity: Conducting a thorough literature review demonstrates the rigor and scholarly integrity of the research. It ensures that researchers are aware of relevant studies and can accurately attribute ideas and findings to their original sources.

Types of Literature Review

Literature review plays a crucial role in guiding the research process , from providing the background of the study to research dissemination and contributing to the synthesis of the latest theoretical literature review findings in academia.

However, not all types of literature reviews are the same; they vary in terms of methodology, approach, and purpose. Let's have a look at the various types of literature reviews to gain a deeper understanding of their applications.

1. Narrative Literature Review

A narrative literature review, also known as a traditional literature review, involves analyzing and summarizing existing literature without adhering to a structured methodology. It typically provides a descriptive overview of key concepts, theories, and relevant findings of the research topic.

Unlike other types of literature reviews, narrative reviews reinforce a more traditional approach, emphasizing the interpretation and discussion of the research findings rather than strict adherence to methodological review criteria. It helps researchers explore diverse perspectives and insights based on the research topic and acts as preliminary work for further investigation.

Steps to Conduct a Narrative Literature Review

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-writing-a-narrative-review_fig1_354466408

Define the research question or topic:

The first step in conducting a narrative literature review is to clearly define the research question or topic of interest. Defining the scope and purpose of the review includes — What specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore? What are the main objectives of the research? Refine your research question based on the specific area you want to explore.

Conduct a thorough literature search

Once the research question is defined, you can conduct a comprehensive literature search. Explore and use relevant databases and search engines like SciSpace Discover to identify credible and pertinent, scholarly articles and publications.

Select relevant studies

Before choosing the right set of studies, it’s vital to determine inclusion (studies that should possess the required factors) and exclusion criteria for the literature and then carefully select papers. For example — Which studies or sources will be included based on relevance, quality, and publication date?

*Important (applies to all the reviews): Inclusion criteria are the factors a study must include (For example: Include only peer-reviewed articles published between 2022-2023, etc.). Exclusion criteria are the factors that wouldn’t be required for your search strategy (Example: exclude irrelevant papers, preprints, written in non-English, etc.)

Critically analyze the literature

Once the relevant studies are shortlisted, evaluate the methodology, findings, and limitations of each source and jot down key themes, patterns, and contradictions. You can use efficient AI tools to conduct a thorough literature review and analyze all the required information.

Synthesize and integrate the findings

Now, you can weave together the reviewed studies, underscoring significant findings such that new frameworks, contrasting viewpoints, and identifying knowledge gaps.

Discussion and conclusion

This is an important step before crafting a narrative review — summarize the main findings of the review and discuss their implications in the relevant field. For example — What are the practical implications for practitioners? What are the directions for future research for them?

Write a cohesive narrative review

Organize the review into coherent sections and structure your review logically, guiding the reader through the research landscape and offering valuable insights. Use clear and concise language to convey key points effectively.

Structure of Narrative Literature Review

A well-structured, narrative analysis or literature review typically includes the following components:

- Introduction: Provides an overview of the topic, objectives of the study, and rationale for the review.

- Background: Highlights relevant background information and establish the context for the review.

- Main Body: Indexes the literature into thematic sections or categories, discussing key findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks.

- Discussion: Analyze and synthesize the findings of the reviewed studies, stressing similarities, differences, and any gaps in the literature.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main findings of the review, identifies implications for future research, and offers concluding remarks.

Pros and Cons of Narrative Literature Review

- Flexibility in methodology and doesn’t necessarily rely on structured methodologies

- Follows traditional approach and provides valuable and contextualized insights

- Suitable for exploring complex or interdisciplinary topics. For example — Climate change and human health, Cybersecurity and privacy in the digital age, and more

- Subjectivity in data selection and interpretation

- Potential for bias in the review process

- Lack of rigor compared to systematic reviews

Example of Well-Executed Narrative Literature Reviews

Paper title: Examining Moral Injury in Clinical Practice: A Narrative Literature Review

Source: SciSpace

You can also chat with the papers using SciSpace ChatPDF to get a thorough understanding of the research papers.

While narrative reviews offer flexibility, academic integrity remains paramount. So, ensure proper citation of all sources and maintain a transparent and factual approach throughout your critical narrative review, itself.

2. Systematic Review

A systematic literature review is one of the comprehensive types of literature review that follows a structured approach to assembling, analyzing, and synthesizing existing research relevant to a particular topic or question. It involves clearly defined criteria for exploring and choosing studies, as well as rigorous methods for evaluating the quality of relevant studies.

It plays a prominent role in evidence-based practice and decision-making across various domains, including healthcare, social sciences, education, health sciences, and more. By systematically investigating available literature, researchers can identify gaps in knowledge, evaluate the strength of evidence, and report future research directions.

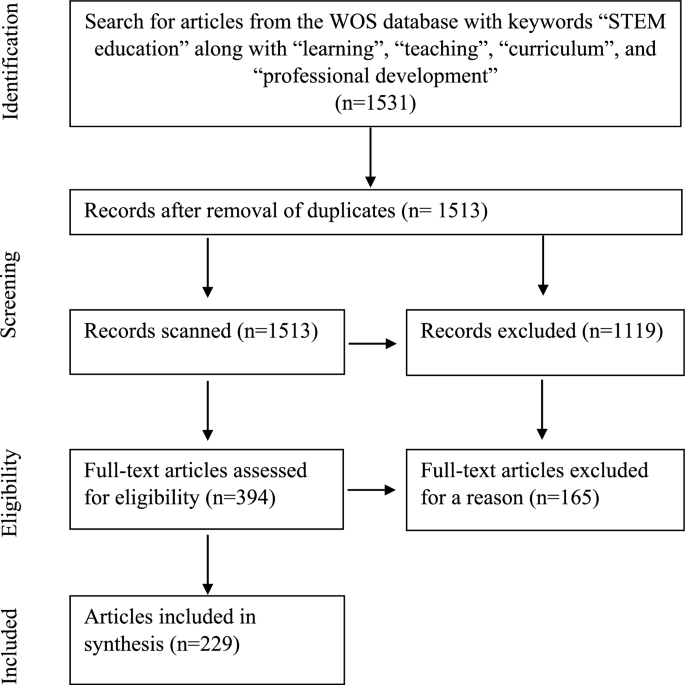

Steps to Conduct Systematic Reviews

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-Systematic-Literature-Review_fig1_321422320

Here are the key steps involved in conducting a systematic literature review

Formulate a clear and focused research question

Clearly define the research question or objective of the review. It helps to centralize the literature search strategy and determine inclusion criteria for relevant studies.

Develop a thorough literature search strategy

Design a comprehensive search strategy to identify relevant studies. It involves scrutinizing scientific databases and all relevant articles in journals. Plus, seek suggestions from domain experts and review reference lists of relevant review articles.

Screening and selecting studies

Employ predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to systematically screen the identified studies. This screening process also typically involves multiple reviewers independently assessing the eligibility of each study.

Data extraction

Extract key information from selected studies using standardized forms or protocols. It includes study characteristics, methods, results, and conclusions.

Critical appraisal

Evaluate the methodological quality and potential biases of included studies. Various tools (BMC medical research methodology) and criteria can be implemented for critical evaluation depending on the study design and research quetions .

Data synthesis

Analyze and synthesize review findings from individual studies to draw encompassing conclusions or identify overarching patterns and explore heterogeneity among studies.

Interpretation and conclusion

Interpret the findings about the research question, considering the strengths and limitations of the research evidence. Draw conclusions and implications for further research.

The final step — Report writing

Craft a detailed report of the systematic literature review adhering to the established guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). This ensures transparency and reproducibility of the review process.

By following these steps, a systematic literature review aims to provide a comprehensive and unbiased summary of existing evidence, help make informed decisions, and advance knowledge in the respective domain or field.

Structure of a systematic literature review

A well-structured systematic literature review typically consists of the following sections:

- Introduction: Provides background information on the research topic, outlines the review objectives, and enunciates the scope of the study.

- Methodology: Describes the literature search strategy, selection criteria, data extraction process, and other methods used for data synthesis, extraction, or other data analysis..

- Results: Presents the review findings, including a summary of the incorporated studies and their key findings.

- Discussion: Interprets the findings in light of the review objectives, discusses their implications, and identifies limitations or promising areas for future research.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main review findings and provides suggestions based on the evidence presented in depth meta analysis.

*Important (applies to all the reviews): Remember, the specific structure of your literature review may vary depending on your topic, research question, and intended audience. However, adhering to a clear and logical hierarchy ensures your review effectively analyses and synthesizes knowledge and contributes valuable insights for readers.

Pros and Cons of Systematic Literature Review

- Adopts rigorous and transparent methodology

- Minimizes bias and enhances the reliability of the study

- Provides evidence-based insights

- Time and resource-intensive

- High dependency on the quality of available literature (literature research strategy should be accurate)

- Potential for publication bias

Example of Well-Executed Systematic Literature Review

Paper title: Systematic Reviews: Understanding the Best Evidence For Clinical Decision-making in Health Care: Pros and Cons.

Read this detailed article on how to use AI tools to conduct a systematic review for your research!

3. Scoping Literature Review

A scoping literature review is a methodological review type of literature review that adopts an iterative approach to systematically map the existing literature on a particular topic or research area. It involves identifying, selecting, and synthesizing relevant papers to provide an overview of the size and scope of available evidence. Scoping reviews are broader in scope and include a diverse range of study designs and methodologies especially focused on health services research.

The main purpose of a scoping literature review is to examine the extent, range, and nature of existing studies on a topic, thereby identifying gaps in research, inconsistencies, and areas for further investigation. Additionally, scoping reviews can help researchers identify suitable methodologies and formulate clinical recommendations. They also act as the frameworks for future systematic reviews or primary research studies.

Scoping reviews are primarily focused on —

- Emerging or evolving topics — where the research landscape is still growing or budding. Example — Whole Systems Approaches to Diet and Healthy Weight: A Scoping Review of Reviews .

- Broad and complex topics : With a vast amount of existing literature.

- Scenarios where a systematic review is not feasible: Due to limited resources or time constraints.

Steps to Conduct a Scoping Literature Review

While Scoping reviews are not as rigorous as systematic reviews, however, they still follow a structured approach. Here are the steps:

Identify the research question: Define the broad topic you want to explore.

Identify Relevant Studies: Conduct a comprehensive search of relevant literature using appropriate databases, keywords, and search strategies.

Select studies to be included in the review: Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, determine the appropriate studies to be included in the review.

Data extraction and charting : Extract relevant information from selected studies, such as year, author, main results, study characteristics, key findings, and methodological approaches. However, it varies depending on the research question.

Collate, summarize, and report the results: Analyze and summarize the extracted data to identify key themes and trends. Then, present the findings of the scoping review in a clear and structured manner, following established guidelines and frameworks .

Structure of a Scoping Literature Review

A scoping literature review typically follows a structured format similar to a systematic review. It includes the following sections:

- Introduction: Introduce the research topic and objectives of the review, providing the historical context, and rationale for the study.

- Methods : Describe the methods used to conduct the review, including search strategies, study selection criteria, and data extraction procedures.

- Results: Present the findings of the review, including key themes, concepts, and patterns identified in the literature review.

- Discussion: Examine the implications of the findings, including strengths, limitations, and areas for further examination.

- Conclusion: Recapitulate the main findings of the review and their implications for future research, policy, or practice.

Pros and Cons of Scoping Literature Review

- Provides a comprehensive overview of existing literature

- Helps to identify gaps and areas for further research

- Suitable for exploring broad or complex research questions

- Doesn’t provide the depth of analysis offered by systematic reviews

- Subject to researcher bias in study selection and data extraction

- Requires careful consideration of literature search strategies and inclusion criteria to ensure comprehensiveness and validity.

In short, a scoping review helps map the literature on developing or emerging topics and identifying gaps. It might be considered as a step before conducting another type of review, such as a systematic review. Basically, acts as a precursor for other literature reviews.

Example of a Well-Executed Scoping Literature Review

Paper title: Health Chatbots in Africa Literature: A Scoping Review

Check out the key differences between Systematic and Scoping reviews — Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

4. Integrative Literature Review

Integrative Literature Review (ILR) is a type of literature review that proposes a distinctive way to analyze and synthesize existing literature on a specific topic, providing a thorough understanding of research and identifying potential gaps for future research.

Unlike a systematic review, which emphasizes quantitative studies and follows strict inclusion criteria, an ILR embraces a more pliable approach. It works beyond simply summarizing findings — it critically analyzes, integrates, and interprets research from various methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) to provide a deeper understanding of the research landscape. ILRs provide a holistic and systematic overview of existing research, integrating findings from various methodologies. ILRs are ideal for exploring intricate research issues, examining manifold perspectives, and developing new research questions.

Steps to Conduct an Integrative Literature Review

- Identify the research question: Clearly define the research question or topic of interest as formulating a clear and focused research question is critical to leading the entire review process.

- Literature search strategy: Employ systematic search techniques to locate relevant literature across various databases and sources.

- Evaluate the quality of the included studies : Critically assess the methodology, rigor, and validity of each study by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter and select studies aligned with the research objectives.

- Data Extraction: Extract relevant data from selected studies using a structured approach.

- Synthesize the findings : Thoroughly analyze the selected literature, identify key themes, and synthesize findings to derive noteworthy insights.

- Critical appraisal: Critically evaluate the quality and validity of qualitative research and included studies by using BMC medical research methodology.

- Interpret and present your findings: Discuss the purpose and implications of your analysis, spotlighting key insights and limitations. Organize and present the findings coherently and systematically.

Structure of an Integrative Literature Review

- Introduction : Provide an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the integrative review.

- Methods: Describe the opted literature search strategy, selection criteria, and data extraction process.

- Results: Present the synthesized findings, including key themes, patterns, and contradictions.

- Discussion: Interpret the findings about the research question, emphasizing implications for theory, practice, and prospective research.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main findings, limitations, and contributions of the integrative review.

Pros and Cons of Integrative Literature Review

- Informs evidence-based practice and policy to the relevant stakeholders of the research.

- Contributes to theory development and methodological advancement, especially in the healthcare arena.

- Integrates diverse perspectives and findings

- Time-consuming process due to the extensive literature search and synthesis

- Requires advanced analytical and critical thinking skills

- Potential for bias in study selection and interpretation

- The quality of included studies may vary, affecting the validity of the review

Example of Integrative Literature Reviews

Paper Title: An Integrative Literature Review: The Dual Impact of Technological Tools on Health and Technostress Among Older Workers

5. Rapid Literature Review

A Rapid Literature Review (RLR) is the fastest type of literature review which makes use of a streamlined approach for synthesizing literature summaries, offering a quicker and more focused alternative to traditional systematic reviews. Despite employing identical research methods, it often simplifies or omits specific steps to expedite the process. It allows researchers to gain valuable insights into current research trends and identify key findings within a shorter timeframe, often ranging from a few days to a few weeks — unlike traditional literature reviews, which may take months or even years to complete.

When to Consider a Rapid Literature Review?

- When time impediments demand a swift summary of existing research

- For emerging topics where the latest literature requires quick evaluation

- To report pilot studies or preliminary research before embarking on a comprehensive systematic review

Steps to Conduct a Rapid Literature Review

- Define the research question or topic of interest. A well-defined question guides the search process and helps researchers focus on relevant studies.

- Determine key databases and sources of relevant literature to ensure comprehensive coverage.

- Develop literature search strategies using appropriate keywords and filters to fetch a pool of potential scientific articles.

- Screen search results based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Extract and summarize relevant information from the above-preferred studies.

- Synthesize findings to identify key themes, patterns, or gaps in the literature.

- Prepare a concise report or a summary of the RLR findings.

Structure of a Rapid Literature Review

An effective structure of an RLR typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction: Briefly introduce the research topic and objectives of the RLR.

- Methodology: Describe the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction process.

- Results: Present a summary of the findings, including key themes or patterns identified.

- Discussion: Interpret the findings, discuss implications, and highlight any limitations or areas for further research

- Conclusion: Summarize the key findings and their implications for practice or future research

Pros and Cons of Rapid Literature Review

- RLRs can be completed quickly, authorizing timely decision-making

- RLRs are a cost-effective approach since they require fewer resources compared to traditional literature reviews

- Offers great accessibility as RLRs provide prompt access to synthesized evidence for stakeholders

- RLRs are flexible as they can be easily adapted for various research contexts and objectives

- RLR reports are limited and restricted, not as in-depth as systematic reviews, and do not provide comprehensive coverage of the literature compared to traditional reviews.

- Susceptible to bias because of the expedited nature of RLRs. It would increase the chance of overlooking relevant studies or biases in the selection process.

- Due to time constraints, RLR findings might not be robust enough as compared to systematic reviews.

Example of a Well-Executed Rapid Literature Review

Paper Title: What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature

A Summary of Literature Review Types

Literature Review Type | Narrative | Systematic | Integrative | Rapid | Scoping |

Approach | The traditional approach lacks a structured methodology | Systematic search, including structured methodology | Combines diverse methodologies for a comprehensive understanding | Quick review within time constraints | Preliminary study of existing literature |

How Exhaustive is the process? | May or may not be comprehensive | Exhaustive and comprehensive search | A comprehensive search for integration | Time-limited search | Determined by time or scope constraints |

Data Synthesis | Narrative | Narrative with tabular accompaniment | Integration of various sources or methodologies | Narrative and tabular | Narrative and tabular |

Purpose | Provides description of meta analysis and conceptualization of the review | Comprehensive evidence synthesis | Holistic understanding | Quick policy or practice guidelines review | Preliminary literature review |

Key characteristics | Storytelling, chronological presentation | Rigorous, traditional and systematic techniques approach | Diverse source or method integration | Time-constrained, systematic approach | Identifies literature size and scope |

Example Use Case | Historical exploration | Effectiveness evaluation | Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed combination | Policy summary | Research literature overview |

Tools and Resources for Conducting Different Types of Literature Reviews

Online scientific databases.

Platforms such as SciSpace , PubMed , Scopus , Elsevier , and Web of Science provide access to a vast array of scholarly literature, facilitating the search and data retrieval process.

Reference management software

Tools like SciSpace Citation Generator , EndNote, Zotero , and Mendeley assist researchers in organizing, annotating, and citing relevant literature, streamlining the review process altogether.

Automate Literature Review with AI tools

Automate the literature review process by using tools like SciSpace literature review which helps you compare and contrast multiple papers all on one screen in an easy-to-read matrix format. You can effortlessly analyze and interpret the review findings tailored to your study. It also supports the review in 75+ languages, making it more manageable even for non-English speakers.

Goes without saying — literature review plays a pivotal role in academic research to identify the current trends and provide insights to pave the way for future research endeavors. Different types of literature review has their own strengths and limitations, making them suitable for different research designs and contexts. Whether conducting a narrative review, systematic review, scoping review, integrative review, or rapid literature review, researchers must cautiously consider the objectives, resources, and the nature of the research topic.

If you’re currently working on a literature review and still adopting a manual and traditional approach, switch to the automated AI literature review workspace and transform your traditional literature review into a rapid one by extracting all the latest and relevant data for your research!

There you go!

Frequently Asked Questions

Narrative reviews give a general overview of a topic based on the author's knowledge. They may lack clear criteria and can be biased. On the other hand, systematic reviews aim to answer specific research questions by following strict methods. They're thorough but time-consuming.

A systematic review collects and analyzes existing research to provide an overview of a topic, while a meta-analysis statistically combines data from multiple studies to draw conclusions about the overall effect of an intervention or relationship between variables.

A systematic review thoroughly analyzes existing research on a specific topic using strict methods. In contrast, a scoping review offers a broader overview of the literature without evaluating individual studies in depth.

A systematic review thoroughly examines existing research using a rigorous process, while a rapid review provides a quicker summary of evidence, often by simplifying some of the systematic review steps to meet shorter timelines.

A systematic review carefully examines many studies on a single topic using specific guidelines. Conversely, an integrative review blends various types of research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

You might also like

This ChatGPT Alternative Will Change How You Read PDFs Forever!

Smallpdf vs SciSpace: Which ChatPDF is Right for You?

Adobe PDF Reader vs. SciSpace ChatPDF — Best Chat PDF Tools

- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services

- Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services : Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

- Develop a Protocol

- Develop Your Research Question

- Select Databases

- Select Gray Literature Sources

- Write a Search Strategy

- Manage Your Search Process

- Register Your Protocol

- Citation Management

- Article Screening

- Risk of Bias Assessment

- Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Find Guidance by Discipline

- Manage Your Research Data

- Browse Evidence Portals by Discipline

- Automate the Process, Tools & Technologies

- Adapting Systematic Review Methods

- Additional Resources

Choosing a Literature Review Methodology

Growing interest in evidence-based practice has driven an increase in review methodologies. Your choice of review methodology (or literature review type) will be informed by the intent (purpose, function) of your research project and the time and resources of your team.

- Decision Tree (What Type of Review is Right for You?) Developed by Cornell University Library staff, this "decision-tree" guides the user to a handful of review guides given time and intent.

Types of Evidence Synthesis*

Critical Review - Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or model.

Mapping Review (Systematic Map) - Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature.

Meta-Analysis - Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results.

Mixed Studies Review (Mixed Methods Review) - Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies.

Narrative (Literature) Review - Broad, generic term - Refers to an examination and general synthesis of the research literature, often with a wide scope; completeness and comprehensiveness may vary. Does not follow an established protocol.

Overview - Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics.

Qualitative Systematic Review or Qualitative Evidence Synthesis - Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies.

Rapid Review - Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research.

Scoping Review or Evidence Map - Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research.

State-of-the-art Review - Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives on issue or point out area for further research.

Systematic Review - Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesize research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review. (An emerging subset includes Living Reviews or Living Systematic Reviews - A [review or] systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available.)

Systematic Search and Review - Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis.’

Umbrella Review - Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results.

*Apart from some qualifying description for "Narrative (Literature) Review", these definitions are provided in Grant & Booth's "A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies."

Literature Review Types/Typologies, Taxonomies

Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. "A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies." Health Information and Libraries Journal 26.2 (2009): 91-108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x Link

Munn, Zachary, et al. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology , vol. 18, no. 1, Nov. 2018, p. 143. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. Link

Sutton, A., et al. "Meeting the Review Family: Exploring Review Types and Associated Information Retrieval Requirements." Health Information and Libraries Journal 36.3 (2019): 202-22. DOI: 10.1111/hir.12276 Link

- << Previous: Home

- Next: The Systematic Review Process >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 3:55 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/literature_review

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Massive Attack’s science-led drive to lower music’s carbon footprint

Career Feature 04 SEP 24

Tales of a migratory marine biologist

Career Feature 28 AUG 24

Nail your tech-industry interviews with these six techniques

Career Column 28 AUG 24

Why I’m committed to breaking the bias in large language models

Career Guide 04 SEP 24

Binning out-of-date chemicals? Somebody think about the carbon!

Correspondence 27 AUG 24

No more hunting for replication studies: crowdsourced database makes them easy to find

Nature Index 27 AUG 24

Publishing nightmare: a researcher’s quest to keep his own work from being plagiarized

News 04 SEP 24

Intellectual property and data privacy: the hidden risks of AI

How can I publish open access when I can’t afford the fees?

Career Feature 02 SEP 24

Postdoctoral Associate- Genetic Epidemiology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

NOMIS Foundation ETH Postdoctoral Fellowship

The NOMIS Foundation ETH Fellowship Programme supports postdoctoral researchers at ETH Zurich within the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life ...

Zurich, Canton of Zürich (CH)

Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich

13 PhD Positions at Heidelberg University

GRK2727/1 – InCheck Innate Immune Checkpoints in Cancer and Tissue Damage

Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg (DE) and Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg (DE)

Medical Faculties Mannheim & Heidelberg and DKFZ, Germany

Postdoctoral Associate- Environmental Epidemiology

Open faculty positions at the state key laboratory of brain cognition & brain-inspired intelligence.

The laboratory focuses on understanding the mechanisms of brain intelligence and developing the theory and techniques of brain-inspired intelligence.

Shanghai, China

CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology (CEBSIT)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 11:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Types of Articles found in Scholarly Journals

- How to Limit to Empirical Articles

Literature Review Articles

- Theoretical Articles

- News, Book Reviews, Opinion, Letters to the Editor, etc.

- Video: How to Read a Scholarly Article

What if I see words often found in other articles?

Since literature reviews reference others articles, you may find the buzz words commons in theoretical and empirical articles.. Existence of these words is common in review articles. The phrase literature review is option predominantly featured in the title or abstract. These are really great finds for your research to help you lead ahead in your research.

- Purpose of a literature review

- Key Questions for a lit review

- What does a literature review article look like

- There's a literature review in my empirical article

A literature summarizes & analyzes published work on a topic in order to

- evaluate the state of research on the topic.

- provide an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic.

- suggest future research and/or gaps in knowledge.

- synthesize and place into context original research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic (as in the literature review prior within an empirical research article.

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

1. Who are the key researchers on this topic?

2. What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

3. How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

4. Have there been any controversies or debates about the research? Is there a consensus? Are there any contradictions?

5. Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

6. How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

7. Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

8. What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

9. How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

10. How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation?

The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

The body of the review should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups the author can then discuss the merits of each article and provide analysis and comparison of the importance of each article to similar ones.

The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the lit review.

In this context, the "literature" refers published scholarly work in a field. Literature includes journal articles, conference proceedings, technical reports, and books.

A literature review can also be a short introductory section of a research article, report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. In the anatomy of a scholarly research article example, the literature review is a part of the introduction. Sometimes in empirical research, the literature review is its own section.

- << Previous: How to Limit to Empirical Articles

- Next: Theoretical Articles >>

- Last Updated: Jul 1, 2024 9:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.rider.edu/types

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Librarian Assistance

For help, please contact the librarian for your subject area. We have a guide to library specialists by subject .

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 5:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

We want to hear from you! Fill out the Library's User Survey and enter to win.

Pharmacy : Types of Review Articles (Literature, Scoping and Systematic)

- Pharmacy Library (Lower Level, Room 0013)

- Creating a Search Strategy

- Databases (PubMed, Embase, +more)

- Grey Literature Sources (Websites, theses, clinical trials +more)

- Electronic Journals (Browse journals, or look for a place to publish)

- Types of Review Articles (Literature, Scoping and Systematic)

- Research Methods (Designing your own research; calculating statistics)

- Indigenous Research and Resources

- Patents - Where to Search

- Artificial Intelligence Tools for Research

- Critical Appraisal

- Cite Using the AMA Style

- Reference (Citation) Management Programs - Zotero, RefWorks, Mendeley

- Writing Tips

- Research Data Management

Their Uniqueness, Characteristics and Differences

- Types of Review Articles

The above slides explore:

- The purpose of each type of review article

- Their methodology

- Practical examples for each article type

- Systematic Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and other Knowledge Syntheses (McGill University) Learn about the different types of knowledge syntheses and how to conduct them.

- Knowledge syntheses: Systematic & Scoping Reviews, and other review types (University of Toronto) Useful information and resources on the process of conducting various types of reviews or knowledge syntheses.

- Review Types (Temple University) Outlines other types of reviews like rapid reviews, mixed methods reviews, overview of reviews, etc. For each review, includes: definition, process, timeframe, limitations, + links to useful resources for conducting the review.

- Review Comparison Chart (Unity Health Toronto/St. Michael's Health Sciences Library) Compares the key elements of major knowledge synthesis methodologies in an infographic.

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tool (Unity Health Toronto/St. Michael's Health Sciences Library) This tool assists in making a decision about what type of review is right for you based on your research question(s) and the required parameters of each type of review. It is meant to be used with the comparison chart.

Systematic Review Management Software

- Covidence - a systematic review software tool Web-based software to support systematic screening and data abstraction for systematic and scoping reviews. Free for Waterloo students, faculty and researchers.

- Distiller Subscription-based, but student pricing available.

- Rayyan A free web-tool designed to manage the stages of systematic reviews and other knowledge synthesis projects.

What is the Project's Goal?

Always ask yourself:

- Do I want to systematically/comprehensively search the literature?

- Or, do I want to conduct a systematic review?

Conducting a comprehensive search of the literature involves very different methods than a systematic review. If you are unsure as to which project best meets your needs, consult the Pharmacy Liaison Librarian, Caitlin Carter at [email protected]

Writing the Protocol (Plan)

- What information should be provided in a protocol? (University of Toronto)

- JBI Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (see 11.2, "Development of a Scoping Review Protocol")

- Template for a systematic literature review protocol (Durham University)

- Knowledge Synthesis Protocol Template (Unity Health Toronto/St. Michael's Health Sciences Library)

Avoid duplication: register your scoping or systematic review protocol (plan)

- Where to prospectively register a systematic review? A short article describing the differences between the various available registration options.

- PROSPERO Protocol registry for systematic reviews. Does not accept scoping reviews or literature reviews. Research topic must be health or social care related.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Registry Register scoping and systematic reviews (must be JBI-affiliated).

- Research Registry Register reviews, randomized controlled trials, case reports, cohort studies, etc.

- Center for Open Science Register any research type.

- Protocols.io Register any research type.

- Nature's Protocol Exchange Protocols from all areas of the natural sciences.

Literature (Narrative) Reviews

These resources offer practical insight into literature reviews:

- The literature review: A few tips on conducting it

- Literature reviews: An overview for graduate students (video)

- Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method

- Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide

- Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade

- The four-part literature review process: breaking it down for students

- Advanced Research Skills: Conducting Literature and Systematic Reviews (free, online short course)

Scoping Reviews

These resources offer practical insight into scoping reviews:

- Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework

- Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework

- Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology

- The Joanna Briggs Institute - Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews

- Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews

Systematic Reviews

These resources offer practical insight into systematic reviews:

- Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions

- Systematic Reviews: The Process (Duke University)

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) Find out if reviews and economic evaluations have already been done before embarking on new projects. Last batch of records was added in 2015.

- PRISMA - what to report in a systematic review

- Doing a systematic review: A student's guide Available in PRINT in Pharmacy Library, Call number: R853.S94 D65 2017

- Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews Click on "download free PDF"

- Systematic Reviews (University of Ottawa) Systematic Reviews explained using the PIECES Model: planning, identifying, evaluating, collecting and combining, explaining and summarizing.

Library Support for Systematic Reviews

- UW Library Systematic Review Support Overview of the types of UW Library support for systematic/scoping review projects.

- UW Library Systematic Review Protocol Use the "UW Library Systematic Review Protocol" to identify the various aspects of your systematic review (SR) project. This protocol will help minimize the likelihood of bias throughout the SR process, which is vital to a SR.

- << Previous: Electronic Journals (Browse journals, or look for a place to publish)

- Next: Research Methods (Designing your own research; calculating statistics) >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 3:42 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.uwaterloo.ca/pharmacy

Research guides by subject

Course reserves

My library account

Book a study room

News and events

Work for the library

Support the library

We want to hear from you. You're viewing the newest version of the Library's website. Please send us your feedback !

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions