- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Cruel Spectacle of ‘The Whale’

By Roxane Gay

Contributing Opinion Writer

“The Whale ,” Darren Aronofsky’s latest film, is one you hope, desperately, will be seen by an audience that has the necessary cultural literacy, the empathy, to watch the story and recognize that the onscreen portrayal of fatness bears little resemblance to the lived experiences of fat people. It is a gratuitous, self-aggrandizing fiction at best.

The film should ask us to see Charlie, the protagonist played by Brendan Fraser, as a person, to understand his grief and mourn with him, to hope for him to pull his life together. But that’s not how the movie was filmed. Most audiences will see the spectacle of a 600-pound man unwilling to care for himself, grieving the loss of his partner who died by suicide, eager to die himself and using food as the means to that end. The disdain the filmmakers seem to have for their protagonist is constant, inescapable. It’s infuriating. To have all this onscreen talent and all these award-winning creators behind the camera, working to make an inhumane film about a very human being — what, exactly, is the point of that?

For most of its two-hour run time, “The Whale” is emotionally devastating. Charlie’s grief and inability to find the will to live are utterly crushing. The material circumstances of his life — teaching writing online; always hiding from his students by keeping his camera off; enduring the understandable fury of his teenage daughter, who simply wants to know why he abandoned her; shirking the concern of his best friend, who has already lost one beloved brother and can hardly bear to lose her last connection to him — are overwhelming and relentless, manipulative and pitiable. I suppose that’s the point of this particular adaptation of Sam Hunter’s play of the same name.

“The Whale” is assiduous about conveying its gravitas and self-importance. There is the austere title card and the dark and claustrophobic setting of a dank apartment; the formidable cast emotes solemnly but energetically. I didn’t know much about the film, but I did know that it was about a fat man seeking some kind of redemption and that it starred Mr. Fraser, one of my favorite actors. Even though he wore a fat suit for the role, a Hollywood practice I find abhorrent, I was willing to give the movie a chance because he has earned plenty of my good will.

Members of the small cast acquit themselves well enough with the material they’re given. Charlie is isolated and is reckoning with his mistakes as he dies of heart failure. This is not a subtle film. In his final days, he tries to reconcile with his estranged, irreverent daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink). He is cared for by his best friend and deceased partner’s sister, Liz (Hong Chau), and the monotony of his life is interrupted by Thomas (Ty Simpkins) a misguided missionary who awkwardly inserts himself into Charlie’s last days.

Mr. Fraser brings pathos to this role, though I wish he had been given better material, more worthy of his talent. His performance makes him a strong contender for all the major awards, and that’s a shame — not because he doesn’t deserve them but because what’s also being rewarded is such a demeaning portrayal of a fat man. We’ll hear about how brave Mr. Fraser is for taking on a role like this, for wearing a fat suit, for being willing to embody so many people’s worst fears. Hollywood loves to reward actors who dare to take on roles that require them to abandon the good looks that enabled their careers.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

“The Whale” is an abhorrent film, but it also features excellent performances.

It gawks at the grotesquerie of its central figure beneath the guise of sentimentality, but it also offers sharp exchanges between its characters that ring with bracing honesty.

It’s the kind of film you should probably see if only to have an informed, thoughtful discussion about it, but it’s also one you probably won’t want to watch.

This aligns it with Darren Aronofsky’s movies in general, which can often be a challenging sit. The director is notorious for putting his actors (and his audiences) through the wringer, whether it’s Jennifer Connolly’s drug addict in “ Requiem for a Dream ,” Mickey Rourke’s aging athlete in “ The Wrestler ,” Natalie Portman’s obsessed ballerina in “ Black Swan ,” or Jennifer Lawrence’s besieged wife in “mother!” (For the record, I’m a fan of Aronofsky’s work in general.)

But the difference between those films and “The Whale” is their intent, whether it’s the splendor of their artistry or the thrill of their provocation. There’s a verve to those movies, an unpredictability, an undeniable daring, and a virtuoso style. They feature images you’ve likely never seen before or since, but they’ll undoubtedly stay with you afterward.

“The Whale” may initially feel gentler, but its main point seems to be sticking the camera in front of Brendan Fraser , encased in a fat suit that makes him appear to weigh 600 pounds, and asking us to wallow in his deterioration. In theory, we are meant to pity him or at least find sympathy for his physical and psychological plight by the film’s conclusion. But in reality, the overall vibe is one of morbid fascination for this mountain of a man. Here he is, knocking over an end table as he struggles to get up from the couch; there he is, cramming candy bars in his mouth as he Googles “congestive heart failure.” We can tsk-tsk all we like between our mouthfuls of popcorn and Junior Mints while watching Fraser’s Charlie gobble greasy fried chicken straight from the bucket or inhale a giant meatball sub with such alacrity that he nearly chokes to death. The message “The Whale” sends us home with seems to be: Thank God that’s not us.

In working from Samuel D. Hunter’s script, based on Hunter’s stage play, Aronofsky doesn’t appear to be as interested in understanding these impulses and indulgences as much as pointing and staring at them. His depiction of Charlie’s isolation within his squalid Idaho apartment includes a scene of him masturbating to gay porn with such gusto that he almost has a heart attack, a moment made of equal parts shock value and shame. But then, in a jarring shift, the tone eventually turns maudlin with Charlie’s increasing martyrdom.

Within the extremes of this approach, Fraser brings more warmth and humanity to the role than he’s afforded on the page. We hear his voice first; Charlie is a college writing professor who teaches his students online from behind the safety of a black square. And it’s such a welcoming and resonant sound, full of decency and humor. Fraser’s been away for a while, but his contradictions have always made him an engaging screen presence—the contrast of his imposing physique and playful spirit. He does so much with his eyes here to give us a glimpse into Charlie’s sweet but tortured soul, and the subtlety he’s able to convey goes a long way toward making “The Whale” tolerable.

But he’s also saddled with a screenplay that spells out every emotion in ways that are so clunky as to be groan-inducing. At Charlie’s most desperate, panicky moments, he soothes himself by reading or reciting a student’s beloved essay on Moby Dick , which—in part—gives the film its title and will take on increasing significance. He describes the elusive white whale of Herman Melville’s novel as he stands up, shirtless, and lumbers across the living room, down the hall, and toward the bedroom with a walker. At this moment, you’re meant to marvel at the elaborate makeup and prosthetic work on display; you’re more likely to roll your eyes at the writing.

“He thinks his life will be better if he can just kill this whale, but in reality, it won’t help him at all,” he intones in a painfully obvious bit of symbolism. “This book made me think about my own life,” he adds as if we couldn’t figure that out for ourselves.

A few visitors interrupt the loneliness of his days, chiefly Hong Chau as his nurse and longtime friend, Liz. She’s deeply caring but also no-nonsense, providing a crucial spark to these otherwise dour proceedings. Aronofsky’s longtime cinematographer, the brilliant Matthew Libatique , has lit Charlie’s apartment in such a relentlessly dark and dim fashion to signify his sorrow that it’s oppressive. Once you realize the entirety of the film will take place within these cramped confines, it sends a shiver of dread. And the choice to tell this story in the boxy, 1.33 aspect ratio further heightens its sense of dour claustrophobia.

But then “Stranger Things” star Sadie Sink arrives as Charlie’s rebellious, estranged daughter, Ellie; her mom was married to Charlie before he came out as a gay man. While their first meeting in many years is laden with exposition about the pain and awkwardness of their time apart, the two eventually settle into an interesting, prickly rapport. Sink brings immediacy and accessibility to the role of the sullen but bright teenager, and her presence, like Chau’s, improves “The Whale” considerably. Her casting is also spot-on in her resemblance to Fraser, especially in her expressive eyes.

The arrival of yet another visitor—an earnest, insistent church missionary played by Ty Simpkins —feels like a total contrivance, however. Allowing him inside the apartment repeatedly makes zero sense, even within the context that Charlie believes he’s dying and wants to make amends. He even says to this sweet young man: “I’m not interested in being saved.” And yet, the exchanges between Sink and Simpkins provide some much-needed life and emotional truth. The subplot about their unlikely friendship feels like something from a totally different movie and a much more interesting one.

Instead, Aronofsky insists on veering between cruelty and melodrama, with Fraser stuck in the middle, a curiosity on display.

Now playing in theaters.

Christy Lemire

Christy Lemire is a longtime film critic who has written for RogerEbert.com since 2013. Before that, she was the film critic for The Associated Press for nearly 15 years and co-hosted the public television series “Ebert Presents At the Movies” opposite Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, with Roger Ebert serving as managing editor. Read her answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here .

- Brendan Fraser as Charlie

- Sadie Sink as Ellie

- Hong Chau as Liz

- Ty Simpkins as Thomas

- Samantha Morton as Mary

- Sathya Sridharan as Dan

- Andrew Weisblum

- Darren Aronofsky

Cinematographer

- Matthew Libatique

- Rob Simonsen

Writer (based on the play by)

- Samuel D. Hunter

Leave a comment

Now playing.

Rebel Ridge

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice

Piece by Piece

Merchant Ivory

The Deliverance

City of Dreams

Out Come the Wolves

Seeking Mavis Beacon

Latest articles

Venice Film Festival 2024: Happyend, Pavements, Familiar Touch

Venice Film Festival 2024: The Biennale College

Telluride Film Festival 2024: Nickel Boys, The Piano Lesson, September 5

Fight or Flight: Jeremy Saulnier on Rebel Ridge

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

The Definitive Voice of Entertainment News

Subscribe for full access to The Hollywood Reporter

site categories

‘the whale’ review: brendan fraser is heart-wrenching in darren aronofsky’s portrait of regret and deliverance.

Sadie Sink, Hong Chau, Ty Simpkins and Samantha Morton also appear in this chamber drama adapted by Samuel D. Hunter from his play about grief and salvation.

By David Rooney

David Rooney

Chief Film Critic

- Share on Facebook

- Share to Flipboard

- Send an Email

- Show additional share options

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Reddit

- Share on Tumblr

- Share on Whats App

- Print the Article

- Post a Comment

Related Stories

'the quiet son' review: far-right radicalism pulls a family apart in an intensely-performed french drama, 'pavements' review: alex ross perry's multifaceted portrait of the influential '90s band is all-encompassing and a bit exhausting.

With its airless single setting and main character whose dire health crisis makes the ticking clock on his life apparent from the start, The Whale seemed a tricky prospect for screen transfer. Aronofsky succeeds not by artificially opening up the piece but by leaning into its theatricality, immersing us in the claustrophobia that has become inescapable for Fraser’s character, Charlie. The scene structure of a focal character confined to a few rooms while secondary characters come and go, at times overlapping, remains very much that of a play.

Shooting in the snug 1.33 aspect ratio might seem to box us in even more, and the shortage of light seeping in from outside Charlie’s apartment is perhaps a tad symbolically heavy-handed. But DP Matthew Libatique’s spry camera and Andrew Weisblum’s dynamic editing bring surprising movement to the static situation. The one significant questionable choice is the overkill of Rob Simonsen’s emotionally emphatic score, rather than trusting the actors to do that work.

Aronofsky and Hunter startle the audience early on, not just by exposing Charlie’s severe obesity — Fraser wears a mix of latex suit plus digital prosthetics designed by Adrien Morot — but by revealing this mountain of a man to be still capable of sexual desire. Charlie keeps the camera off during the online writing course he teaches, claiming that the webcam on his laptop is broken. But its video component functions just fine when moments later he’s watching gay porn and furiously masturbating.

Charlie’s crisis is averted by the arrival of his health care worker friend Liz ( Hong Chau , wonderful), who is used to dealing with his emergencies. She tells him his congestive heart failure and sky-high blood pressure mean he’ll likely be dead within a week. Exasperated at his continuing refusal to go to a hospital, ostensibly due to lack of health insurance, Liz is often impatient and angry with Charlie. But her love for him is such that she reluctantly indulges his fast-food addiction, bringing him buckets of fried chicken and meatball subs.

Grief is the ailment that unites Charlie and sharp-tongued Liz, also making her ferocious with the persistently present Thomas. Her adoptive father is a senior council member at New Life, and she blames the death of her brother Alan on the church. Alan was a former student of Charlie’s who became the love of his life but could never get over his father’s condemnation, developing a chronic eating disorder that eventually killed him.

The tidy symmetry of one partner starving himself to death and the other’s self-destruction happening through gluttony is a little schematic, just as the Moby Dick elements are a literary flourish that shows the writer’s hand. But Hunter’s script and the intimacy of the actors’ work keep the melancholy drama grounded and credible.

The teenager’s spiky confrontations with her gentle giant of a father are matched by her needling exchanges with Thomas, whom she manipulates the same way she does Charlie and her hard-bitten mother. Sink (a Stranger Things regular) doesn’t hold back in a characterization that justifies Mary’s description of her as “evil.” But the residual love beneath both women’s screechy outbursts and hurt distance is slowly revealed in some genuinely moving moments, notably as Charlie reminisces with Mary about a family trip to Oregon when he was much less heavy, the last time he went swimming.

Every member of the small ensemble makes an impression, even the mostly unseen Sathya Sridharan as a friendly pizza delivery guy who never fails to ask about Charlie’s welfare from behind the closed apartment door.

The standout, alongside Fraser, is Chau, following her slyly funny work in Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up with a nuanced turn as a woman knocked sideways by loss and bracing for another devastating hit of it. In both cases, her inability to intervene has left her helpless, enraged, exhausted and in visible pain. There’s also humor in Liz’s annoyance with Charlie’s innate positivity, which endures no matter how bad his circumstances become. In a movie that’s partly about the human instinct to care for other people, Chau breaks your heart.

His physicality, straining to navigate awkward spaces and maneuver a body that requires more strength than Charlie has left, is distressing to witness, as are his fits of coughing, choking, gasping for breath. On the few occasions where he struggles to stand to his full height, he fills the frame, a figure of tremendous pathos less because of his size than his suffering. But in a film about salvation, it’s the inextinguishable humanity of Fraser’s performance that floors you.

Full credits

Thr newsletters.

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Dave bautista talks ‘the killer’s game’ romance and how ‘dune: part two’ repurposed ‘dune’ footage, box office preview: ‘beetlejuice beetlejuice’ eyes near-record $100m-$110m september opening, ‘the apprentice’ producers explain why they need a kickstarter campaign, trump film ‘the apprentice’ set for private toronto fest screening, mixed ‘joker: folie à deux’ reviews highlight lack of excitement, underused lady gaga in sequel, ‘diva futura’ review: a messy but well-acted celebration of the golden age of an italian porn empire.

‘The Whale’ Review: Brendan Fraser Is Sly and Moving as a Morbidly Obese Man, but Darren Aronofsky’s Film Is Hampered by Its Contrivances

The director seamlessly adapts Samuel D. Hunter's play but can't transcend the play's problems.

By Owen Gleiberman

Owen Gleiberman

Chief Film Critic

- ‘Joker: Folie à Deux’ Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Star in a Cracked Jukebox Musical — but It Doesn’t Let Joker Be Joker Enough 12 hours ago

- ‘The Room Next Door’ Review: Tilda Swinton Gives a Monumental Performance as a Woman Confronting Death in Pedro Almodóvar’s First English-Language Drama 2 days ago

- ‘Wolfs’ Review: George Clooney and Brad Pitt Are Rival Fixers in a Winning Action Comedy Spiked With Movie-Star Chemistry 3 days ago

Related Stories

The Postwar Streaming Market: A Special Report

Enid Blyton Adaptation 'Magic Faraway Tree' Lands U.K. Distribution Deal

Popular on variety.

“The Whale” is based on a stageplay by Samuel D. Hunter, who also wrote the script, and the entire film takes place in Charlie’s apartment, most of it unfolding in that seedy bookish living room. Aronofsky doesn’t necessarily “open up” the play, but working with the great cinematographer Matthew Libatique he doesn’t need to. Shot without flourishes, the movie has a plainspoken visual flow to it. And given what a sympathetic and fascinating character Fraser makes Charlie, we’re eager to settle in with him in that depressive lair, and to get to the bottom of the film’s inevitable two dramatic questions: How did Charlie get this way? And can he be saved?

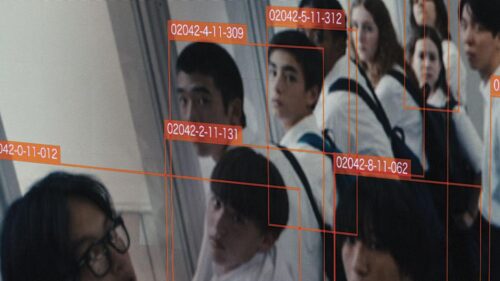

In case there is any doubt he needs saving, “The Whale” quickly establishes that he’s an addict living a life of isolated misery and self-disgust, scarfing away his despair (at various points we see him going at a bucket of fried chicken, a drawer full of candy, and voluminous take-out pizzas from Gambino’s, all of which is rather sad to behold). Charlie teaches an expository writing seminar at an online college, doing it on Zoom, which looks very today (though the film, for no good reason, is set during the presidential primary season of 2016), with video images of the students surrounding a small black square at the center of the screen. That’s where Charlie should be; he tells the students his laptop camera isn’t working, which is his way of hiding his body and the shame he feels about it. But he’s a canny teacher who knows what good writing is, even if his lessons about structure and topic sentences fall on apathetic ears.

Charlie has a friend of sorts, Liz (Hong Chau), who happens to be a nurse, and when she comes over and learns that his blood pressure is in the 240/130 range, she declares it an emergency situation. He has congestive heart failure; with that kind of blood pressure, he’ll be dead in a week. But Charlie refuses to go the hospital, and will continue to do so. He’s got a handy excuse. With no health insurance, if he seeks medical care he’ll run up tens of thousands of dollars in bills. As Liz points out, it’s better to be in debt than dead. But Charlie’s resistance to healing himself bespeaks a deeper crisis. He doesn’t want help. If he dies (and that’s the film’s basic suspense), it will essentially be a suicide.

It’s hard not to notice that Liz, given how much she’s taking care of Charlie, has a spiky and rather abrasive personality. We think: Okay, that’s who she is. But a couple of other characters enter the movie — and when Ellie (Sadie Sink), Charlie’s 17-year-old daughter, shows up, we notice that she has a really spiky and abrasive personality. Does Charlie just happen to be surrounded by hellcats and cranks? Or is there something in Hunter’s dialogue that is simply, reflexively over-the-top in its theatrical hostility?

And what a rage it is! Sadie Sink, from “Stranger Things,” acts with a fire and directness that recalls the young Lindsay Lohan, but the volatile spitfire she’s playing is bitter — at her father, and at the world — in an absolutist way that rings absolutely false. Lots of teenagers are angry and alienated, but they’re not just angry and alienated. There are shades of vulnerability that come with being that age. We keep waiting for Ellie to show another side, to reflect the fact that the father she resents is still, on some level … her father.

“The Whale,” while it has a captivating character at its center, turns out to be equal parts sincerity and hokum. The movie carries us along, tethering the audience to Fraser’s intensely lived-in and touching performance, yet the more it goes on the more its drama is interlaced with nagging contrivances, like the whole issue of why this father and daughter were ever so separated from each other. We learn that after Charlie and Ellie’s mother, Mary (Samantha Morton), were divorced, Mary got full custody and cut Charlie off from Ellie. But they never stopped living in the same small town, and even single parents who don’t have custody are legally entitled to see their children. Charlie, we’re told, was eager to have kids; he lived with Ellie and her mother until the girl was eight. So why would he have just … let her go?

There’s one other major character, a lost young missionary for the New Life Church named Thomas, and though Ty Simpkins plays him appealingly, the way this cult-like church plays into the movie feels like one hard-to-swallow conceit too many. This matters a lot, because if we can’t totally buy what’s happening, we won’t be as moved by Charlie’s road to redemption. Near the end, there’s a very moving moment. It’s when Charlie is discussing the essay on “Moby Dick” he’s been reading pieces of throughout the film, and we learn where the essay comes from and why it means so much to him. If only the rest of the movie were that convincing! But most of “The Whale” simply isn’t as good as Brendan Fraser’s performance. For what he brings off, though, it deserves to be seen.

Reviewed at Venice Film Festival, Sept. 4, 2022. Running time: 117 MIN.

- Production: An A24 release of a Protozoa Pictures production. Producers: Darren Aronofsky, Jeremy Dawson, Art Handel. Executive producers: Scott Franklin, Tyson Bidner.

- Crew: Director: Darren Aronofsky. Screenplay: Samuel D. Hunter. Camera: Matthew Libatique. Editor: Andrew Weisblum. Music: Rob Simonsen.

- With: Brendan Fraser, Sadie Sink, Ty Simpkins, Hong Chau, Samantha Morton, Sathya Sridharan.

More from Variety

Andrew Garfield, Florence Pugh to Close San Sebastian Film Festival With John Crowley’s ‘We Live in Time’

Take-Two Earnings Emblematic of Endless Risk-Taking in Gaming Biz

Fortnite’s Complicated Return to iOS Is Hardly a Victory

More from our brands, paula abdul cancels canada tour over injuries: ‘breaks my heart’.

$6.2 Million Will Score You This Seventh-Floor Spread at the Dakota in N.Y.C.

Navarro, Pegula Highlight Billionaire Parents at U.S. Open

The Best Loofahs and Body Scrubbers, According to Dermatologists

Outlander Finale Recap: A Pivotal Death Sends Jamie and Claire Back to Where It All Began — Plus, Grade It!

Brendan Fraser Deserves an Oscar for ‘The Whale.’ He Also Deserves a Better Movie

By David Fear

Charlie is 600 lbs. This is the first thing you notice about him; this is the first thing you are meant to notice about him. He’s always been a big guy, he says, but he “let it get out of control.” On the Zooms in which Charlie teaches online English courses — he’s a professor — his voice is always emanating from a solid square of black, the video permanently disabled, the word “Instructor” the only visual his students associate with him.

But when we first see Charlie in The Whale , director Darren Aronofsky’s adaptation of Samuel D. Hunter’s award-winning 2012 play, we get to observe all of him: a bulk of a man, his body bloated and swollen, sitting deep in the corner of his couch, masturbating furiously to online porn. Severe chest pains interrupt his endeavor. Only the arrival of a random stranger, who happens to find the apartment door unlocked, saves his life.

Editor’s picks

Every awful thing trump has promised to do in a second term, the 250 greatest guitarists of all time, the 500 greatest albums of all time, 25 most influential creators of 2024, trump tries to convince america he's not weird and totally normal at town hall, 14-year-old boy identified as georgia school shooting suspect, goldman sachs says trump win would lead to economic downturn , oasis announce invite-only wembley stadium reunion concerts after chaotic ticket sale, ryan reynolds calls on academy to add best stunts category, four-time oscars host jimmy kimmel won't return in 2025: it became 'too much' to balance, hear paul weller's haunting cover of billie eilish's ‘what was i made for’.

Fraser is a dream collaborator in that respect, and yet The Whale seems hellbent on making you view Charlie as a grotesque. There’s something monstrous about the way it keeps framing him, how it seems to almost fetishize every roll of his flesh and put the sound of his greasy chomping on fried chicken so high in the sound mix. What this man is experiencing — a horrible sense of shame that’s metastasized into self-destruction — is not pretty. But the movie seems to revel a little too enthusiastically in its own ugliness. That doom-laden score by Rob Simonsen keeps rubbing the despair even deeper into your face. For every sunbeam of humanity Fraser lets shine through this soul, the film summons a half-dozen dark clouds to try and dampen it.

Disney Pauses Adaptation of 'The Graveyard Book' Amid Neil Gaiman Allegations

- Ramifications

- By Emily Zemler

Lee Daniels Reflects on Making 'Empire': 'Absolutely the Worst Experience'

- Bad Memories

'Rust' Armorer Receives Probation Sentence After Pleading Guilty to Bringing Gun to Bar

- Additional Sentence

- By Larisha Paul

'Grotesquerie' Trailer: Niecy Nash-Betts Stars, Travis Kelce Predicts 'No Future' in Ungodly Thriller

- Ungodly Hour

- By Kalia Richardson

Jason Momoa and Jack Black Enter a Pixelated Paradise in 'A Minecraft Movie' Trailer

Most popular, brad pitt and george clooney dance to 4-minute standing ovation for ‘wolfs’ during chaotic venice premiere, richard gere jokes he had "no chemistry" with julia roberts in 'pretty woman', demi moore fuels speculation that she doesn't approve of channing tatum's plans to remake ghost, jackie winsor, artist whose labor-intensive sculptures inspire mystery and awe, dies at 82, you might also like, ‘aisha can’t fly away’ wins at final cut as venice production bridge wraps, lab-grown cotton start-up galy raises $33 million series b round from inditex, h&m, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors, disney pauses neil gaiman’s ‘the graveyard book’ adaptation in wake of sexual assault allegations — exclusive, navarro, pegula highlight billionaire parents at u.s. open.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Movie Reviews

The Whale review: Brendan Fraser shines in a overwrought, underbaked drama

The actor is better than director Darren Aronfosky's stagey adaptation.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/image001-1-96bff255cc7d4c8da59d9d4192867e86.jpg)

In every awards season, there are certain movies whose heat index seems to rise almost solely because of a central performance: actors so indelible in the part they transcend the flaws and missteps of the film formed around them. (Renée Zellweger in Judy was one a few years ago, or Rami Malek in Bohemian Rhapsody ; both won Oscars.) Brendan Fraser 's astonishing turn in The Whale often feels like that to the n th degree: a tender, modest, and momentously human piece of work plonked in the midst of a drama so masochistically stilted and stagey it often feels less like a movie than an endurance test, or even worse, a parody.

The staginess, to be fair, is at least partly because it was in fact a play, one that director Darren Aronofsky spent the last decade trying to bring to the screen (the playwright, Samuel D. Hunter, also penned the adaptation). Why the man who helmed Black Swan , The Wrestler , and Requiem for a Dream would find a bleak psychological drama about deeply broken people appealing is not a mystery; what he found irresistible here though, is less easy to see. Fraser's Charlie, in the opening scene, is just a voice inside a black Zoom screen. That's because he teaches remotely at an online college, but his excuse of a broken laptop camera is a lie: The truth is he's morbidly obese, so large that he can't leave his shabby apartment or even stand up without a walker. He can just about manage to bathe and feed himself, but other activities (masturbation, laughing) leave him too clammy and winded to breathe.

There's a gadget for nearly every physical thing he can't do on his own — handles and pulleys in the shower, a special seat in the bathroom, even a little clawed picker-upper for whatever he might drop on the floor. And a friend named Liz ( Watchmen 's Hong Chau ) comes faithfully every day to check his vitals and bring him groceries. Liz is also a nurse, and she keeps telling him plainly that he's dying. But she's often interrupted by a knock at the door: First an earnest young missionary (Ty Simpkins) named Thomas hoping to spread the good word, and later, Ellie ( Stranger Things ' Sadie Sink), his estranged teenage daughter whose only words for him, primarily, are sneered f-bombs. Ellie, hissing and venomous, hates him because he left her mother ( Samantha Morton ) years ago for another man, but mainly she hates everything.

Aside from a single brief flashback, the action, such as it is, is confined entirely to Charlie's drab apartment and the small roundelay of guests who steadily come through to drop chunks of story exposition or settle scores. Fraser — encased in elaborate prosthetics that Aronfosky revels in shooting like a Caravaggio, all shadows and moody, milky light — welcomes them, down to the missionary kid. Charlie knows that he's killing himself and he knows why, but there's hardly any complaint or self-pity; instead he's emotionally generous almost to a fault, a man still eager to spread his love of Walt Whitman and Moby Dick and only connect, even if his efforts are met with mockery or disgust.

He and Chau, who brings a bright acidity and affection to Liz, often seem to be drawing from a different well than their castmates. But all the actors are left to mine their own layers in characters who have only the scantest backstories and broad traits: Hellish Teenager, Troubled Soul, Man Too Big to Live. Those dynamics may have played out better on stage, where a certain kind of bold underlining serves a live audience. Here it often feels clumsy and maddeningly inconsistent, stranding Fraser in a melodrama undeserving of his lovely, unshowy performance. Whatever he wins for The Whale — and early prizes have already come — he deserves. The rest is just chum. Grade: C

Related content:

- Mummy reunion! Brendan Fraser and Michelle Yeoh share a sweet hug at TIFF Tribute Awards

- Brendan Fraser says he might not take another role as deep as The Whale : 'I gave it everything'

- Lena Dunham took Andrew Scott from hot priest to 'hot medieval dad' in Catherine Called Birdy

- Brendan Fraser gets emotional over Whale awards victory, his first trophy 'since grade 4'

Related Articles

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

The Whale Is a Perfect Comeback Role for Brendan Fraser

I was not at the first Venice press screening of Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale , but I did have to see the film that played in the same theater immediately afterward, so I got to wade through a small crowd of still shell-shocked critics as I entered. Before going in, I talked to some colleagues milling about, including a couple of fellow Aronofsky skeptics. They all seemed surprised to have found themselves so devastated by the movie and, in particular, by Brendan Fraser’s performance. The buzz around the movie grew and grew that night and the following day so that, by the time I saw The Whale at its actual premiere in the Sala Grande, the place seemed ready to explode.

And explode it did as soon as the end credits started rolling. The audience response to The Whale , and Fraser, was immediate and immense and sustained. They wouldn’t let him leave . He kept taking bows and bows. He got emotional. Everybody got emotional. It was the kind of total love-in one lives to see at festivals like this.

It felt well deserved. It’s a great comeback story for a beloved box-office star who rarely got the kinds of serious parts that might have led to awards buzz in the past. In his heyday, Fraser had a seemingly effortless charm that allowed him to glide easily through big poppy movies without ever looking as if he were trying too hard or, worse, not taking things seriously. He always seemed like a sweet guy who was just happy to be there, but he never seemed like a joke. (The films sometimes were jokes, but not him.)

That sweetness is on full display in The Whale , though Aronofsky’s film would probably not be described by anyone as “sweet.” Based on Samuel D. Hunter’s play , it’s the story of Charlie, a 600-pound man who doesn’t leave his apartment, teaches English via Zoom (with his camera always turned off, citing technical issues), and is trying desperately to reconnect with his bitter, estranged daughter (Sadie Sink) before he dies from congestive heart failure. He could and should go to the hospital, but he refuses, citing a lack of health insurance. Charlie seems almost ready to die. He has a downright Zen response when his headstrong nurse, Liz (Hong Chau), freaks out about his blood-pressure numbers. He talks about pain in a matter-of-fact fashion. Charlie, we sense, is always in pain. Near him, he keeps an old, mysterious student essay on Moby-Dick , which he starts reading to himself whenever he has a health scare, even though he’s already memorized it, because he wants to go out on a beautiful note. Talk about symbolism!

Fraser and Aronofsky have talked about trying to portray Charlie’s life-threatening obesity in a compassionate manner, including in their use of prosthetics, which has come under some criticism . The Whale is certainly not a movie about “fat jokes” (though there are a couple of them, particularly in the occasionally comic back-and-forth between Charlie and Liz). But here’s the thing: The film is built around the idea of revulsion and extreme consumption. It has multiple scenes of Charlie eating enormous amounts of food. He stress-eats candy bars when he Googles details about his medical condition. At one point, riddled with shame and guilt, he cries, gorges on piles of food, then vomits it out before our eyes. The idea is that this man is killing himself. The food isn’t so much food as it is a metaphor for all the hurt and pain he’s absorbed. The whole thing is a metaphor, and as such, it’s pitched a few degrees off from reality.

Is Charlie presented as pathetic? Well, yes, but in the original meaning of the word: He evokes sympathy and sadness, not ridicule or contempt. When he talks to people, his eyes are wide and inquisitive, and there’s a half-smile on his face. He seems open, kind, curious — and shy. Prosthetic or no, it’s a perfect part for Fraser. It’s hard to imagine anyone else in the part, frankly. The character’s demeanor makes sense for someone who doesn’t see much company, who is ashamed to show himself to strangers but still longs to connect.

Aronofsky has made a point of not opening up Hunter’s play, which means that not only does the action of the film take place entirely within the confines of Charlie’s apartment, it also has such theatrical devices as people just wandering in at pivotal moments in the story. It’s a wise choice because The Whale is filled with key elements that would stand out as stagy if its world were rendered more realistically. (Remember that essay on Moby-Dick ?) Through his interactions with his daughter and a young missionary (Ty Simpkins) for a fundamentalist religion called the New Life, we learn about Charlie’s past — he left his family because he fell in love with one of his night-school students nine years ago, and he hasn’t been the same since his lover, Alan, died. Indeed, Charlie has basically been eating himself to death since then.

Despite the director’s formal control and the confined setting, The Whale can, for much of its running time, feel tonally muddled. Dark comedy juts against deep emotion, languor bumps against speed. Characters give speeches about religion, and they deliver blunt passages of exposition that can feel awkward. As open and gentle as Fraser’s performance is, the actors around him, particularly Sink, are stylized and brutal — their cutting, angry remarks are delivered in rapid-fire, theatrical fashion. It all feels, initially, like a mistake. But by the final scene, we realize that what we’ve been watching is akin to a chemical experiment; Aronofsky has brought these disparate elements together to bounce them against one another. At one point, I wondered if there was something wrong with the projection because the film was so visually muddy — until someone finally opened a door and gorgeous, gorgeous sunlight flooded the screen. Once everything finally collides in The Whale , something shattering and beautiful and honest emerges.

More From Venice

- James Bond’s Sexuality Is None of Luca Guadagnino’s Business

- A Minute-By-Minute Breakdown of The Brutalist

- Controversial Point: George Clooney and Brad Pitt Are Good Together

- vulture homepage lede

- vulture section lede

- venice film festival

- biennale cinema 2022

- darren aronofsky

- brendan fraser

- new york magazine

- movie review

Most Viewed Stories

- Cinematrix No. 163: September 5, 2024

- The Bachelorette Season-Finale Recap: It Wasn’t Supposed to Be This Way

- Joker: Folie à Deux Commits the Mortal Sin of Wasting Lady Gaga

- Welcome to New MILF Cinema

- Babygirl Might Just Be The Year’s Hottest Movie

- 2024’s Comedians You Should and Will Know

Editor’s Picks

Most Popular

What is your email.

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

Summary A reclusive English teacher (Brendan Fraser) living with severe obesity attempts to reconnect with his estranged teenage daughter for one last chance at redemption.

Directed By : Darren Aronofsky

Written By : Samuel D. Hunter

Where to Watch

Brendan Fraser

Ty simpkins, samantha morton, sathya sridharan, dan the pizza man, young ellie, allison altman, lance oppenheim, grace perkins, wilhelm schalaudek, critic reviews.

- All Reviews

- Positive Reviews

- Mixed Reviews

- Negative Reviews

User Reviews

Related movies, dekalog (1988), tokyo story, the conformist, the leopard (re-release), lawrence of arabia (re-release), citizen kane, three colors: red, the godfather, fanny and alexander (re-release), touch of evil, army of shadows, city lights, intolerance, the rules of the game, seven samurai, the wild bunch, au hasard balthazar, pépé le moko (re-release), related news.

September 2024 Movie Preview

Keith kimbell.

Get details on this month's most notable new films including a long-awaited Beetlejuice sequel, Francis Ford Coppola's controversial passion project, and much more.

2024 Movie Release Calendar

Jason dietz.

Find a schedule of release dates for every movie coming to theaters, VOD, and streaming throughout 2024 and beyond, updated daily.

DVD/Blu-ray Releases: New & Upcoming

Find a list of new movie and TV releases on DVD and Blu-ray (updated weekly) as well as a calendar of upcoming releases on home video.

Every Alien Movie, Ranked

We rank every film in the Alien franchise, from the 1979 original to the new Alien: Romulus, from worst to best by Metascore.

Every Movie Based on a Videogame, Ranked

We rank every live-action film adapted from a video game—dating from 1993's Super Mario Bros. to this month's new Borderlands—from worst to best according to their Metascores.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election results

- Google trends

- AP & Elections

- U.S. Open Tennis

- Paralympic Games

- College football

- Auto Racing

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Review: ‘The Whale’ is a hard but astounding film to watch

This image released by A24 shows Brendan Fraser in a scene from “The Whale.” (A24 via AP)

This image released by A24 shows Hong Chau in a scene from “The Whale.” (A24 via AP)

This image released by A24 shows Sadie Sink in a scene from “The Whale.” (A24 via AP)

Brendan Fraser poses for a portrait in Los Angeles on Friday, Nov. 18, 2022, to promote his film “The Whale.” (Photo by Rebecca Cabage/Invision/AP)

- Copy Link copied

The center of gravity of “The Whale” is obviously the 600-pound man at its center. Look closely, though, and he’s the one with a soul as light as a feather.

Charlie is a reclusive, morbidly obese English literature teacher unable and unwilling to stop eating himself to death. As his health woes mount and his life expectancy is put at just a week, Charlie struggles to reacquaint himself with his estranged daughter. We meet him on Monday and the film goes day by day to Friday.

Charlie is a gentle giant, not raging at his fast approaching demise. He’s an optimist and a fierce believer in truth even though there is nothing in his world reinforcing either. “The Whale” is not always pleasant to watch but the payoff and performances make it an astounding film.

Stationary and wheezing on his couch, Charlie is repeatedly visited by a constellation of people — a friendly nurse, his teenage daughter and a young missionary from an apocalyptical church. They all need something from this well-meaning but broken man — spiritual, medical or familial. They are all broken, too.

The movie, based and adapted from the off-Broadway play of the same name by Samuel D. Hunter, is directed by Darren Aronofsky, who helmed such dark tales as “Requiem for a Dream” and “Black Swan.” Hunter’s depiction of the mortification of the flesh perfectly meets a director enamored by the grotesque.

Brendan Fraser has earned lots of Oscar buzz for playing Charlie, allowing his signature puppy dog face to remain despite a massive body suit and swelling prosthetics. And why not? It is one of the most moving performances in years, full of humanity and a redemptive triumph for an actor who hid his talent in quickly forgotten films like “Blast from the Past,” “Hair Brained” and “Airheads.”

The whole cast is perfect, from Sadie Sink as Charlie’s spiky daughter, Hong Chau as his foul-mouthed nursing angel, Ty Simpkins as the missionary with a hidden past and Samantha Morton as his ex-wife with simmering anger and yet still love. There are steady references to Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick,” which gives the film the title and its doomed vibe.

Charlie has ballooned ever since the death of his same-sex partner, who apparently willed himself to death by wasting away in starvation after their relationship was condemned by his church-leading father. Charlie has apparently decided to die the opposite way.

He is sadly apologetic to his nurse — “I’m sorry,” he says continually — and shuts the video camera on his laptop during his online classes. Even the pizza delivery man doesn’t know what he looks like. “Who would want me to be part of their life?” he asks.

There has been fear that the film might be fatphobic and it’s true that cinematographer Matthew Libatique often leans into unflattering ways to show Charlie, soaping in a shower, straining to stand up or touch the floor, covered in sweat and shoving pizza or fried chicken into his mouth. Maybe some of that could have been touched on instead of lingered on.

But body weight is not what the writer and director want to focus on here. It’s more the weight of guilt and love and faith. “I just want to know I did one good thing in my life!” Charlie shouts. One feels that the underlying issue in “The Whale” could have been obesity as easily as cancer or alcoholism or a blood disorder. Hunter is exploring salvation, redemption, determinism and family.

The play has been sharpened for the screen but there’s no escaping the fact that it is rooted inside Charlie’s Idaho apartment, which he shuffles about in on a walker or later a wheelchair. This doesn’t make for sweeping cinema. Sometimes the apartment feels confining like a ship, adding to the Melville theme.

Some of the filmic attempts are forced, like the symbolically heavy bird that Charlie feeds outside his window, the three times actors rush to leave the apartment only to stop and turn back, and the heavy rain that builds as the film’s climax nears. But this is a film that stays with you and changes you. It is heavy, indeed.

“The Whale,” a A24 release that is in movie theaters on Friday, is rated R for “language, some drug use and sexual content.” Running time: 117 minutes. Four stars out of four.

MPAA definition of R: Restricted. Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian.

Online: https://a24films.com/films/the-whale

Mark Kennedy is at http://twitter.com/KennedyTwits

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

- About Rotten Tomatoes®

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening This Week

- Top Box Office

- Coming Soon to Theaters

- Certified Fresh Movies

Movies at Home

- Fandango at Home

- Prime Video

- Most Popular Streaming Movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- 73% Blink Twice Link to Blink Twice

- 95% Strange Darling Link to Strange Darling

- 86% Between the Temples Link to Between the Temples

New TV Tonight

- 100% Slow Horses: Season 4

- 97% English Teacher: Season 1

- -- The Perfect Couple: Season 1

- -- Tell Me Lies: Season 2

- -- Fight Night: The Million Dollar Heist: Season 1

- -- Wise Guy: David Chase and The Sopranos: Season 1

- -- Outlast: Season 2

- -- The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives: Season 1

- -- Selling Sunset: Season 8

- -- Whose Line Is It Anyway?: Season 14

Most Popular TV on RT

- 73% Kaos: Season 1

- 83% The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power: Season 2

- 88% Terminator Zero: Season 1

- 100% Dark Winds: Season 2

- 95% Only Murders in the Building: Season 4

- 92% Bad Monkey: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

Certified fresh pick

- 97% English Teacher: Season 1 Link to English Teacher: Season 1

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

Venice Film Festival 2024: Movie Scorecard

Best Movies of 2024: Best New Movies to Watch Now

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

Joker: Folie à Deux First Reviews: Joaquin Phoenix Shines Again in ‘Deranged, Exciting, and Deeply Unsettling’ Sequel

Renewed and Cancelled TV Shows 2024

- Trending on RT

- Beetlejuice Beetlejuice

- Top 10 Box Office

- Venice Film Festival

- Popular Series on Netflix

The Whale Reviews

I am certain that as is, The Whale (the film), struggles to say anything meaningful about people and oversells the characterizations and the relationships in a way that doesn’t feel natural.

Full Review | Original Score: 1.5/5 | Jul 26, 2024

...a project that, while certainly powerful at points, could have reached further heights if not for some very questionable calls.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Jul 17, 2024

However unsubtle with its messaging, “The Whale” is a devastating ode to the complexity of human beings, and the inner beauty one can find behind even the most destructive of feelings towards self and others.

Full Review | Jul 15, 2024

“The Whale” works because Fraser, particularly his eyes and voice, and the rest of the cast deliver performances that imbue their two-dimensional characters with enough presence and emotion that they feel three dimensional.

Full Review | Jun 8, 2024

Fraser keeps Charlie’s fully formed humanity at the forefront of The Whale, despite various filmmaking decisions that could flatten his character into a saccharine pity case.

Full Review | Jan 9, 2024

It’s Aronofsky’s most blunt and uninspired work yet— an indulgent and strident slice of misery porn that rides a wave of unearned emotion to its underwhelming conclusion.

Full Review | Nov 2, 2023

If I were to describe this film in one word, it would be melancholy; it is practically flawless, at least in my opinion, and conveys the notion that people are inherently kind...

Full Review | Sep 23, 2023

If you didn’t know that The Whale was based on a play, you’d work it out pretty quickly... The immediate distance that this initially creates soon evaporates, however, in no small part thanks to Fraser’s all-in performance.

Full Review | Sep 21, 2023

If it’s as sincere as it purports to be, this is one of the worst movies of recent years, and if it’s not — which is almost preferable — then it’s a landmark exercise in trolling.

Full Review | Aug 25, 2023

A morbidly obese man racked with self-loathing makes a desperate eleventh-hour attempt to reconnect with his estranged teenage daughter in the overstuffed but worthwhile drama, The Whale.

Full Review | Jul 26, 2023

Earns its place in the "most tearful films of the year" list as it moves slowly yet efficiently towards its overwhelmingly emotional ending, especially elevated by the most subtly powerful & irrefutably moving performance of Brendan Fraser's career.

Full Review | Original Score: B+ | Jul 25, 2023

A riveting character study of one broken man that transcends compassion, love, pain/regret. A masterpiece Sadie Sink/Hong Chau should be nominated & Brendan Fraser might have turned in one of the best performances of all time

Full Review | Jul 25, 2023

I just wished that the film overall was as strong as Brendan Fraser’s acting comeback.

Full Review | Original Score: C | Jul 22, 2023

Charlie [is] played brilliantly by Brendan Fraser...

Full Review | Jun 2, 2023

It has a more or less decent preamble that is propelled by an organic performance from Brendan Fraser on his return, but its psychological marrow is locked into a basic routine of trivial conversations and a lack of substance. [Full reveiw in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 5/10 | Apr 19, 2023

A strangely hopeful story that manages to stay on the surface even as it seems to sink into mediocrity. [Full review in Spanish]

Full Review | Mar 29, 2023

One of the most deplorable elements of The Whale is its near celebration of defeat and resignation. The decision by Charlie to eat himself to death is treated as a meaningful act of self-sacrifice. Why would this possibly be so?

Full Review | Mar 24, 2023

All the weight of the story (metaphorically and literally) is carried by its tragic protagonist — the ailing Charlie, whom Brendan Fraser portrays with such depth, nuance, and wit. Nothing in the film's text matches this commitment, and that's a problem.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Mar 21, 2023

Two words - Brendan Fraser. He was born to play Charlie and his Oscar award is extremely well deserved.

Full Review | Original Score: 3.5/5 | Mar 21, 2023

Chamber settings, by their nature, let the acting echo out and Fraser’s central performance speaks volumes about his character’s history.

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Mar 17, 2023

“The Whale” Portrays Fatness As A Monstrosity

Brendan Fraser is incredible in Darren Aronofsky’s latest drama. But the film is gratuitously fixated on the main character’s fatness.

BuzzFeed News Reporter

Brendan Fraser in The Whale

A long time ago , I learned to be skeptical when critics describe a movie as “unflinching.” “Unflinching” is code for “brave,” shorthand for “willing to go there .” But too often, a movie lauded for being unflinching is often a film rather comfortable with the gratuitous. Lee Daniels’s Precious was dubbed an unflinching look at poverty; Crash was called the same but about racism. Neither label has stood the test of time, partially because we have not yet answered some important questions: When does close observation cross the line from empathy into voyeurism? When does careful attention transform into shameless gawking? Depending on how you answer those questions, Darren Aronofsky ’s The Whale might either be a masterful display of compassion or an exercise in the familiar denigration of leering at the lives of fat people.

The Whale stars Brendan Fraser as Charlie, a depressed fat man who lives alone somewhere in Idaho. A committed shut-in, Charlie teaches online writing classes with his camera perpetually off while living in a cluttered apartment. We learn that his life radically changed after his partner died by suicide, and he’s been on the road to ruin ever since. Because of his 600-pound frame, Charlie is restricted in his movement — he uses a walker to get around and a handle attached to the ceiling to pull himself onto his bed; he needs a grabber to pick up the things that fall on the floor. The Whale relishes in the minute details of Charlie’s movements, offering close-ups as a kind of substitute for humanity. The camera stays uncomfortably close, or perhaps as a viewer you’re uncomfortable because of how close the camera is. Put one point in the “gratuitousness” column.

{ "id": 130912577 } The Whale is a movie that doesn’t know when it should have flinched.

When Charlie is not working, he entertains a range of visitors, from his nurse best friend Liz (an outstanding Hong Chau ) to his estranged daughter Ellie ( Sadie Sink ) to Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a young missionary from New Life, a church with a persistent local recruiting effort. But when Charlie learns that his health is failing rapidly and he doesn’t have long to live, these visits take on increasing urgency, and we see how his boundless and occasionally misplaced faith in people transforms the lives of those around him. A reluctant point for Team Compassion, I suppose.

With three months to go until the 2023 Oscars, Fraser is comfortably in the pole position to take home the Best Actor trophy. Before you even factor in his specific performance, this makes some sense: It’s the kind of role that Academy voters love, requiring a profound transformation. There are already elaborate descriptions of the hours-long daily process that Fraser needed to put on prosthetics that weighed 300 pounds. Add to that the underdog nature of Fraser’s casting — a beloved actor who has been away from the limelight for an extended period of time — and you have key ingredients of an Oscar-favorite narrative.

But even without the power of the narrative, Fraser’s performance is worthy of the Oscar buzz. On the whole, The Whale is uneven: Its thesis on religion is muddled, and it’s not quite sure what it wants to say about how faith transforms us. Aronofsky’s conclusions on the meaning of life seem half-baked. The Whale misuses Sink’s talents, relying on her to deliver outbursts that feel cartoonish and miscalculated despite her preternatural gift in subtler emotional performances. The film’s eye on Charlie's body is at times unsettling and feels over-the-top. Yet if you stack all of the flaws of The Whale — and there are dozens more — Fraser's performance is still so genuinely moving that it keeps the movie from falling flat.

It’s all the more remarkable considering the conversation The Whale has generated. In the New York Times, writer Roxane Gay called The Whale ’s writing and directing “ utterly careless ” and criticized the film for treating fatness as “the ultimate human failure, something despicable, to be avoided at all costs.” Meanwhile, Mark Hanson wrote for Slant Magazine that Aronofsky “may think he’s presenting some kind of radically cathartic journey but all he’s doing is bringing a hollow sense of dignity to his schematic brand of cinematic misery porn.”

The Whale may not work on all levels, but the conversation it is generating tells us that the film has become a perfect emblem of Hollywood’s struggles with representation of fat people and fatness. It’s reawakening the debate about fat suits even as it breaks the box office record for limited opening this year.

What appeared to be a well-meaning film has ended up as part of a long line of art about fat people that ends up trafficking in the same tropes around representing fat people. The Whale is a movie that doesn’t know when it should have flinched. It is a movie that fails to understand that in trying to dignify a type of person we rarely see onscreen, it fails to grasp where that dignity comes from. Put another one in the “voyeurism” column.

Jada Pinkett and Eddie Murphy in The Nutty Professor (1996)

It’s a truly stunning fact that in 1996’s The Nutty Professor , Eddie Murphy plays seven characters and five of them require a fat suit. Murphy didn’t invent the fat suit, but he professionalized it, perhaps even proselytized it. Serious question: What would Murphy’s net worth be if we subtract movies that use a fat suit? Actually, scratch that — what would Tyler Perry’s net worth be without fat suits? Actually, scratch that , what would Mike Myers’s net worth be without fat suits?

What I am trying to get at is that it has always been profitable for Hollywood to deploy fat suits. A character being fat has long been a comedic device, and from time to time Hollywood deemed it funnier for actors who are not fat to dress up as though they are; in these instances, the character’s very fatness was the whole joke.

{ "id": 130912589 } The camera is obsessed with Charlie’s fat, relishing its minuscule movements.

Fatness has long been pathologized in film and television. From Shallow Hal to Precious , from Roseanne to The Drew Carey Show , the fact that fat characters were fat was often a central struggle in their life. But in recent memory, representation of fat people has become much more complex — NBC’s This Is Us was praised for involving actor Chrissy Metz in the development of the arc for her character Kate. Metz spoke openly about the in-depth conversations she had with the producers of the show. Still, critics pointed out the ways Kate represents the worst of Hollywood anti-fat bias . Meanwhile in Pitch Perfect , Rebel Wilson’s Fat Amy reclaimed fatness, and that made her a fan favorite .

But despite whatever progress has been achieved, the fat suit abominations never stopped: There’s Sarah Paulson’s role as Linda Tripp in American Crime Story: Impeachment from last year. In 2017, Gary Oldman won an Oscar for his portrayal of Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour , in which he wore a fat suit. Fat suits seem, by and large, still acceptable in Hollywood, though it’s worth noting where that attitude may be turning. Paulson has promised to never wear one again and told the Los Angeles Times that she regretted wearing it. “I think fat phobia is real,” the actor told the paper. “I think to pretend otherwise causes further harm. And it is a very important conversation to be had.”

It is unfortunate that we are having this conversation with The Whale as its entry point. This is a movie that has made a spectacle of its prosthetics, both onscreen and off. In the film, the fat rolls spill from Charlie’s torso onto his thighs. The camera is obsessed with Charlie’s fat, relishing its minuscule movements. Offscreen, the Herculean task of applying 300 pounds of fake weight to Fraser has been a central pillar of the press tour. (Fraser called the prosthetics “ beautiful and arresting .”) Aronofsky pushed back against calling it a fat suit ; “I wouldn’t use that word,” he protested. “It’s prosthetics and makeup.”

Fraser, for his part, has been trying to complicate the fat suit story a little more: As he stumps for The Whale , he has been arguing that he’s not a trespasser — that he himself is bigger than he used to be in his days as a younger actor, and that his son is fat, so Fraser is no stranger to the difficulties of navigating the world as a fat person. His comments attempt to insulate the movie from the most potent criticism — that it is telling a story about fat people but made by people who have no business telling a story about fat people.

Fine. Let’s check the tape. The Whale ’s source material is the play by the same name, written by Samuel D. Hunter, who adapted his own work for the screen. Hunter has explained that The Whale draws from his own past, including his sexuality and negative relationship to food; he told the New Yorker that in college, he “started falling deeper and deeper into depression, and—this is not everybody—but for me personally it manifested in pretty rapid weight gain throughout my early twenties.”

When the play debuted to rave reviews in 2012, Hunter told the New York Times that his characters are an attempt to capture “a quotidian America that is often hidden behind curtains and doors.” His characters are meant to be “off-putting,” the Times noted, but Hunter’s skill is that they “become more humanized and relatable as the action progresses.”

But despite the best intentions of playwrights turned screenwriters, the translation from one medium to another requires a sophistication that The Whale does not possess. Onstage, audiences can watch Charlie struggle to move as they’re engrossed in the action of the play. His size becomes a part of a broad tapestry that brings his pain, his grief, and his capacity for love to life. But in a movie theater, audiences will watch Aronofsky’s gaze linger on his body in ways that don’t serve the narrative — ways that seem exploitative and possibly even cruel.

The fat suit debate doesn’t have a satisfying answer. Its roots are in a larger debate over whether it is reasonable to demand that everyone involved in the making of any movie depicting an underrepresented community has to be from that community. Surely this can’t be the case — this would undermine the point of the medium itself, which is to be transplanted into another experience in order to understand it, wrestle with it, and absorb it into our understanding of the world.

But the source of the debate is itself linked to a larger problem, which is that Hollywood so rarely makes an effort to accommodate a diverse range of experiences. The major Hollywood studio roles for fat people, or queer people, or trans people come along so rarely that it feels doubly insulting to then have actors of those communities miss out amid a drought of those roles. The Whale is being positioned as a film made by people who are aware of all these conversations. But their mere awareness doesn’t mean the filmmakers have anything insightful to say about fat representation.

Mickey Rourke, left, and director Darren Aronofsky on the set of The Wrestler in 2008.

Aronofsky is no stranger to the careful attention/shameless gawking dichotomy: From the fixation on the scars in The Wrestler to the confrontational shots of the calluses and bleeding toes in Black Swan to, oh, I don’t know, literally any scene in Requiem for a Dream , Aronofsky seems to think that zooming in and staying close on a scene is the same thing as shedding light and inviting empathy. The Whale is the strongest piece of evidence that this approach does not work.

The movie opens with a cautious shot that slowly reveals that Charlie is masturbating to gay porn, before it quickly sets up the stakes: just seeking this personal private pleasure might literally kill him. As he climaxes, Charlie’s heart is unable to cope with the exertion. But what is frustrating about this scene is the way the camera approaches Charlie; it’s staged like the monster reveal in a horror film. As critic Sean Donovan put it , the camera goes in “as if it’s afraid to approach him too quickly, a reticence that is hard to distinguish as a fear of what Charlie is doing or a fear of what Charlie is .”

{ "id": 130912752 } Aronofsky seems to think that zooming in and staying close on a scene is the same thing as shedding light and inviting empathy.

In the throes of a cardiac episode, Charlie receives an unexpected visitor, a young missionary. Gasping for air and exclaiming in pain, Charlie demands that his visitor read an essay aloud. It is here we learn that the title of the film is not only a convenient reference to Charlie’s size, but in fact it refers to Moby-Dick . But death hangs in the air from that moment on: We learn from Liz, Charlie's nurse friend who drops in to check on him, that his heart is failing, and he has maybe a week or so to live.

Charlie’s visitors can’t help but react to his weight. It’s the first thing they notice about him — his estranged daughter, the missionary, his ex-wife, and even the pizza deliverer who finally sees him after months of coming every day to leave the pizza at his front step. Though Liz is deeply familiar with Charlie's size, even she struggles with how to respond to it: She debates giving him a large sub because she doesn’t want to enable his compulsive eating habits.

That conflict bears out in The Whale — multiple scenes where Charlie’s mental health is spiraling has him frantically eating. These scenes are meant as clear displays of self-harm, but still there is something disquieting about anxious horror music swelling as the protagonist shoves a pizza in his mouth. Another point to Team Leering.

As the credits rolled, I kept thinking about the way those binging scenes were shot. One credit line thanks the Obesity Action Coalition for its participation in the film. The OAC’s website states that the organization is “dedicated to giving a voice” to people “affected by the disease of obesity.”

How did the coalition do that in the production of The Whale ? In a written statement, a representative told me that the OAC is “honored” to have participated in the film. “A24 approached us with the opportunity to offer the production team and the film's lead actor, Brendan Fraser, insight into the realities of living with severe obesity,” the statement said. “Our goal was to make sure the representation of severe obesity was realistic and respectful—not the caricature we so often see in movies or television shows.”

The OAC said it shared “the significant physical, emotional and social impacts of obesity, and we see that insight reflected in many of Charlie’s (Brendan Fraser) movements, actions and emotions throughout the film.” The statement described Fraser as “highly receptive to our feedback.”

But what does it mean for The Whale to consult the OAC in the first place? Activist Aubrey Gordon wrote in her book What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat that use of the word “obesity” itself is complicated because its definition is “inherently blaming fat people for their bodies.” (BuzzFeed News’ own style guide eschews “obese” and “overweight” in favor of the neutrality of “fat.”) How engaged is The Whale in conversations about fat justice in the first place? And how can it claim to be accountable to them if its preferred source of guidance employs outdated terms?

On the one hand, it sounds like those involved in the production of The Whale at least made an effort to hear about the lived reality of fat people before bringing it to life onscreen. But on the other hand, is The Whale really what care looks like? Is this as good as it gets? ●

Topics in this article

- Brendan Fraser

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Giddy Delights of “1941”

Little did I know, when, in December, 1979, I saw Steven Spielberg’s new film, “1941”—in 70-mm., on the curved screen of the Cinema 150 theatre, in Woodbury, Long Island— that I was witnessing a psychodrama of historic proportions. With a retrospective of Spielberg’s films opening at Film Forum (it runs through September 12th), the memory of that viewing, with its jolts of giddy delight, becomes all the more poignant. “1941” is my favorite film of Spielberg’s. It may not be his most personal movie (“ The Fabelmans ” is his family story, after all), but it’s the one in which he shows the most of his inner life—maybe even more than he intended. In “1941,” he lets his manic, movie-loving inner child loose and avows far more about his love of movies—and its connection to his fundamental worldview—than was prudent. It’s the film in which he lets himself go, in which he displays his cinematic id, and it’s perhaps the only one in which he suggests that he has an id at all. Yet the part of Spielberg that was unleashed proved unpopular. Critics panned “1941,” and, though it was neither a blockbuster nor a financial flop, it was a big disappointment after the smash hits of “ Jaws ” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” Spielberg, chastened, never cut loose again.

The premise of “1941” is, if not exactly offensive, cheerfully frivolous, in the vein of, say, the TV show “Hogan’s Heroes”: it’s a comedy about the entry of the United States into the Second World War, days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. (The film was loosely inspired by civil-defense mobilizations that took place in California, in preparation for a possible Japanese attack on the West Coast.) Working with a script by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, based on a story they’d written with John Milius, Spielberg brings together a teeming array of characters whose sense of purpose range from the fiercely martial and the steadfastly patriotic to the charmingly romantic and the brashly sexual. Converging thanks to a series of extravagant coincidences, they cause large-scale destruction in various Los Angeles venues where nobody gets seriously hurt.

The military action is launched by the arrival of a real-life figure, the crusty General Joseph W. Stilwell (Robert Stack), who has been sent to reassure the public but who, after a flurry of pronouncements and his flurry of orders, puts his duties aside for a screening of “Dumbo” at a theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. Stilwell’s aide, Captain Loomis Birkhead (Tim Matheson), is desperate to reëngage with a sort-of ex, Stilwell’s secretary, Donna Stratton (Nancy Allen), who has a fetish for airplanes—indeed, claims to get no pleasure except when airborne. The soldiers cross paths with a civilian named Wally (Bobby Di Cicco), a dishwasher slash waiter slash wannabe hipster who has a thing for dancing and is secretly dating a woman, Betty Douglas (Dianne Kay), whose father, Ward (Ned Beatty), despises him. An Army delegation persuades Ward, whose house is perched on the Santa Monica waterfront, to let a huge anti-aircraft cannon be placed on his lawn. A member of the delegation, Corporal “Stretch” Sitarski (Treat Williams), instantly falls for Betty; her best friend, Maxine (Wendie Jo Sperber), instantly falls for him. The three of them meet up at a U.S.O. dance in a ballroom where the women work as hostesses entertaining uniformed servicemen. Wally, worried that he’ll lose Betty to Stretch, frantically schemes to find a uniform and get in.

Roiling the armed forces from the skies is Captain Wild Bill Kelso (John Belushi), an unhinged pilot who rants with cigar in mouth and squeaky toy in pocket, hoping to take the battle to Japanese invaders. Civil defense proves equally antic, as two Santa Monica locals, Claude (Murray Hamilton) and his loopy grown son Herb (Eddie Deezen), are handed weapons, brought to an amusement park, and posted overnight in a Ferris wheel, high above the ground, to keep watch. Meanwhile, there really is a Japanese submarine looming off the coast with a German officer aboard. The Axis mission is to destroy Hollywood in order to deflate American morale and achieve a symbolic victory.

All of which is to say that the film is centered on the allure and the importance of Hollywood—and it’s situated in a world that bears no resemblance to any part of reality other than the substance and the power of Hollywood movies themselves. Spielberg makes sure that viewers recognize this cinema-centric artificiality from the very start, with a “Jaws” parody: a woman swimming alone in frigid waters has a terrifyingly close encounter with the surfacing submarine, during which a Japanese crew member gazing at her gleefully calls out, “Hollywood!” The Hollywood that Spielberg celebrates is that of its classic-era directors—a Hollywood that he evidently sees himself as heir to. When Wild Bill lands his airplane at a remote gas station to refuel, the resulting catastrophe is a parody of the gas-station conflagration in Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds.” However, where Hitchcock produces a vision of frozen horror, Spielberg simply delivers the regressive pleasure of explosions and flames. Kelso, whose reckless gunplay is to blame, hustles off to his plane with the awkward indifference of a toddler.

The scale of “1941” is colossal. Cityscape exteriors extend far along avenues and across office-building rooftops as backdrops for tumultuous action on land and in air—precision stunts, chaotic crowd scenes, aeronautical ballets, and chases by car and tank and motorcycle. Yet the film’s mighty and meticulous craft is largely in the service of primal gratifications and crude effects, which are rendered no less regressive by the Rube Goldberg-esque intricacy of the physical chains of causality giving rise to them. The emotional world mirrors that of “Looney Tunes,” and, indeed, its main cinematic forebear is a great comedy director who got his start as an animator and director on “Looney Tunes”: Frank Tashlin. Tashlin directed six of Jerry Lewis ’s early films, and, though Lewis isn’t in “1941,” his comic persona, which Tashlin had a decisive role in forming, looms large. (The goofy character of Herb, a childlike chatterbox, is essentially a Lewis surrogate, his name borrowed from Lewis’s character in “ The Ladies Man .”)