Growth Tactics

Types of Group Discussion: Strategies for Effective Discussions

Jump To Section

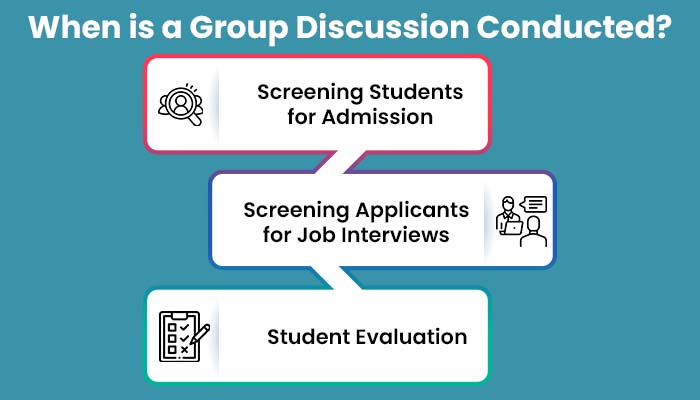

Group discussion is a valuable tool for learning, collaboration, and fostering critical thinking skills. Whether you are a student preparing for an exam, an educator looking for ways to engage your students, or a leader trying to solve a problem, understanding the different types of group discussions, topics, and strategies is essential. In this blog post, we will explore the various types of group discussions, how to choose a suitable topic, and strategies for facilitating meaningful and productive discussions.

Understanding Group Discussion

Group discussions are a form of interactive communication that involves a small group of individuals sharing their thoughts, ideas, and opinions on a specific topic. These discussions can take place in various settings, such as classrooms, organizations, or professional settings, and can serve different purposes, such as problem-solving, decision-making, or brainstorming.

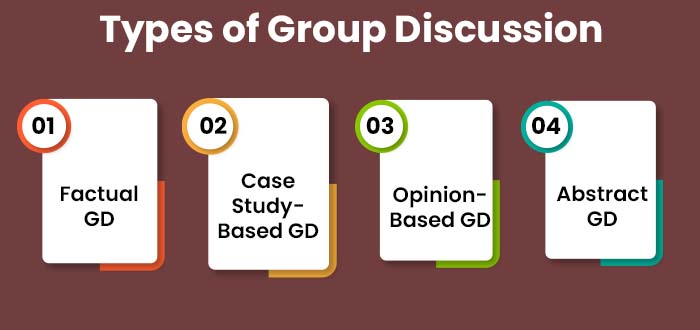

Types of Group Discussion

Group discussions offer a dynamic environment for sharing thoughts, ideas, and opinions. They can be beneficial for learning, collaboration, and developing critical thinking skills . Let’s explore three types of group discussions: case-based discussions, topic-based discussions, and structured group discussions.

1. Case-Based Discussions

In case-based discussions, participants analyze and discuss specific cases or scenarios. They evaluate possible solutions or approaches, which helps develop problem-solving and analytical skills. By actively engaging with real or hypothetical case studies, participants enhance their ability to think critically about complex situations.

2. Topic-Based Discussions

Topic-based discussions center around a specific subject or theme. Participants express their opinions, present arguments, and explore different viewpoints. These discussions improve communication skills and foster critical thinking as participants analyze and evaluate various perspectives on a given topic.

3. Structured Group Discussions

Structured group discussions follow predefined formats or rules. A moderator guides the discussion by posing questions and facilitating conversation. This format ensures active participation and constructive exchanges, providing a framework for focused and productive discussions.

By understanding the different types of group discussions, participants can choose the most suitable format for their goals and create an engaging and interactive environment for meaningful conversations.

Choosing a Suitable Topic

Selecting an appropriate topic is crucial for a successful group discussion. Consider the following factors when choosing a topic:

1. Relevance to the Participants

The topic should be relevant to the participants’ interests, experiences, or areas of study. This helps create a sense of engagement and encourages active participation.

2. Controversial and Thought-Provoking

Controversial topics or those that require critical thinking and analysis can spark lively and meaningful discussions. Avoid vague or overly simplistic topics that do not stimulate thoughtful discussion.

3. Current Affairs and Real-World Issues

Discussing current affairs and real-world issues helps participants develop an understanding of the socio-economic and political landscape. These topics encourage participants to think critically and evaluate different perspectives.

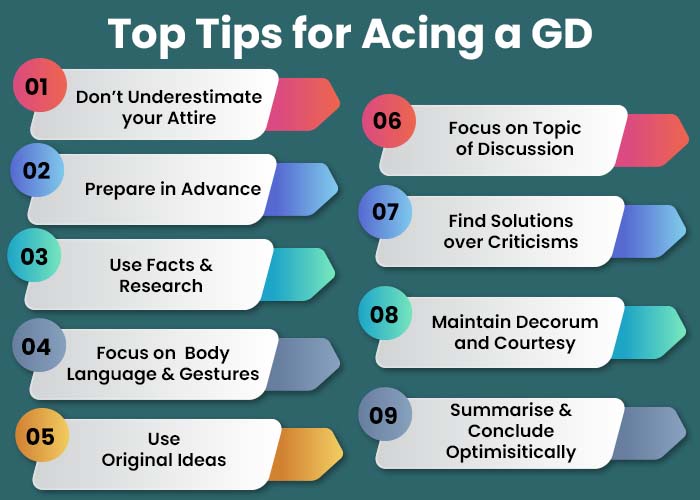

Strategies for Effective Group Discussions

To make group discussions productive and engaging, consider implementing the following strategies:

1. Establish Clear Ground Rules

Start by establishing clear guidelines and expectations for the discussion. These ground rules should emphasize the importance of active listening, respectful communication, and equal participation. By setting a foundation of mutual respect and inclusivity, you create a safe and open environment for all participants to contribute their ideas.

2. Encourage the Expression of Diverse Perspectives

Promote a culture that values and encourages diverse perspectives. Encourage participants to share their unique viewpoints, experiences, and ideas. By actively seeking and embracing different perspectives, you enrich the conversation and foster a deeper understanding of the topic at hand. Remember that diversity of thought leads to more innovative and creative solutions.

3. Foster Lateral Thinking and Problem-Solving

Encourage participants to think critically and approach problems from various angles. Foster an environment that values and promotes lateral thinking, which involves exploring unconventional or alternative solutions. Encourage participants to challenge assumptions and consider different perspectives to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

4. Provide Structured Discussion Prompts

Prepare a list of discussion prompts or questions in advance to guide the conversation. These prompts should cover various aspects of the topic and encourage participants to think critically and express their thoughts. Structured discussion prompts provide a framework and keep the conversation focused and productive. This helps ensure that all important aspects of the topic are explored.

5. Facilitate Active Participation

Actively engage all participants to facilitate their active participation in the discussion. Encourage quieter participants to contribute by directly asking for their input or by creating a supportive environment that encourages them to share their thoughts. By ensuring that everyone feels heard and valued, you create a space for meaningful and collaborative discussions.

By implementing these strategies, you can make your group discussions more effective, inclusive, and thought-provoking. These approaches promote critical thinking, enhance problem-solving skills, and allow for the exploration of multiple perspectives. Remember that an open and respectful environment is key to fostering successful group discussions.

Common Challenges in Group Discussions and How to Overcome Them

Group discussions can be an effective way to generate ideas, facilitate collaboration, and arrive at well-informed decisions. However, there are common challenges that can arise during group discussions. Here are some of these challenges and strategies to overcome them:

1. Dominant Personalities

Some participants may have dominant personalities that can overpower the conversation, making others feel unheard or overshadowed. To prevent dominance, set equal speaking opportunities for everyone. Encourage active listening to make sure everyone’s voice is heard. If someone is dominating the conversation, try direct questions to other participants and redirecting the conversation towards the quieter members.

2. Groupthink

Groupthink occurs when the desire for group harmony leads to conformity and a lack of critical thinking. To avoid it, make sure to encourage diverse opinions, ideas, and perspectives. Assign a designated devil’s advocate whose role is to challenge proposed ideas. Anonymous ideation sessions and setting the tone of every idea is welcome helps in the same.

3. Lack of Focus

Conversations may easily veer off-topic or lack a clear focus, making it difficult to achieve the intended goals. Keep the conversation focused by setting and reviewing an agenda periodically. Encourage participants to take constructive breaks that revitalize their focus. Use summarizing techniques throughout the discussion to align the focus.

4. Unequal Participation

In some situations, certain individuals may dominate conversations while others stay silent. Encourage participation by assigning specific roles, and asking directly for input from quieter participants. Brainstorming techniques can be used like round-robin, think-pair-share, or small groups to ensure equal participation.

5. Conflict Resolution

Conflicts or disagreements may arise during group discussions, leading to stress and uncertainty. To handle conflicts constructively, encourage active listening, acknowledging different perspectives and viewpoints, facilitating open dialogue, and seeking win-win solutions. By creating an open and inclusive space to resolve conflicts, the group’s dynamics and outcomes will enhance positively.

By proactively addressing these common challenges, groups can have meaningful conversations that lead to actionable insights and productive solutions.

Technology and Group Discussions

Technology has revolutionized the way we communicate and collaborate in group settings. With the rise of virtual meetings, video conferencing, and online collaboration tools, it’s now easier than ever to conduct group discussions from anywhere in the world. However, with these benefits come new challenges as well. Here are some ways technology can impact group discussions and how to overcome them.

Pros of Using Technology in Group Discussions

Increased Flexibility and Accessibility : With online tools, group members can join meetings from anywhere, at any time. This allows for greater flexibility and accessibility, making it easier for people to participate in group discussions even if they are not physically present.

Improved Collaboration : Virtual tools allow group members to collaborate in real-time, regardless of their physical location. This makes it easier for members to share ideas and information, and work together to achieve a common goal.

Reduced Costs : Virtual meetings can significantly reduce costs associated with travel and facility rental. This makes it easier for groups with limited resources to conduct discussions without sacrificing the benefits of in-person meetings.

Cons of Using Technology in Group Discussions

Technical Difficulties : Technical difficulties can arise during virtual meetings, which can delay progress and cause frustration. This can be overcome by having all participants test the technology before the meeting and ensuring all participants have a stable internet connection.

Lack of Non-Verbal Cues : During virtual meetings, non-verbal cues such as body language and facial expressions can be difficult to read. To overcome this, group members must be clear and concise with their verbal communication.

Distractions : Since virtual meetings can be conducted from anywhere, it’s easy for participants to become distracted by their surroundings. To overcome this, establish ground rules for participants such as turning off notifications or finding a quiet space to participate in the discussion.

In conclusion, technology has revolutionized the way we conduct group discussions and collaboration. By being aware of the pros and cons of using virtual meetings and online collaboration tools, groups can take advantage of the benefits while mitigating the challenges.

Group discussions are an effective way to promote critical thinking, collaboration, and communication skills . By understanding the different types of group discussions, selecting suitable topics, and implementing effective strategies, educators and students can foster engaging and productive discussions. Remember to establish ground rules, encourage diverse perspectives, and provide structured prompts to make the most out of your group discussions.

Key Takeaways

- Group discussions can take various forms, including case-based and topic-based discussions.

- Choosing a relevant and thought-provoking topic is crucial for effective discussions.

- Strategies such as establishing ground rules and encouraging diverse perspectives enhance the quality of group discussions .

- Active participation and structured discussion prompts facilitate meaningful conversations.

2 thoughts on “Types of Group Discussion: Strategies for Effective Discussions”

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful post. Thanks for providing this information.

Hello growthtactics.net admin, Thanks for the educational content!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

A Step-by-Step Guide To Case Discussion

By ashi jain.

CAT Champions 2024

Join InsideIIM GOLD

Webinars & Workshops

- Compare B-Schools

- Free CAT Course

Take Free Mock Tests

Upskill With AltUni

CAT Study Planner

Are you comfortable in Decision Making in a given situation How aptly you analyze the situation with a logical approach How much time do you take in arriving at a decision How good are you in taking the rightful course of action

Solved Example:

Hari, the only working member of the family has been working an organization for 25 years. His job required long standing hours. One day, while working, he lost his leg in an accident. The company paid for his medical reimbursement.

Since he was a hardworking employee; the company offered him another compensatory job. He refused by saying, ‘Once a Lion, always a Lion’. As an HR, what solution would you suggest?

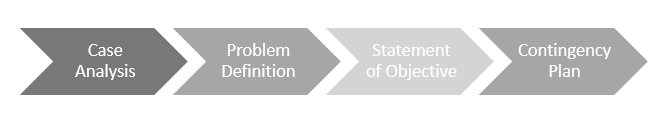

Identification of the Problem:

Obvious: accident, refusal of job, only earning member, his attitude, and inability to do his current job Hidden: the reputation of the company at stake, the course of action might influence other employees

Action Plan:

As an HR, you are first expected to check the company records and find out how a similar case has been dealt with in the past. Second, you need to take cognizance of the track record of the employee highlighted by the keyword ‘hardworking’.

Given the situation at hand, he is deemed unfit for his current role. However, the problem arises because of his attitude towards the compensatory job. Hence, in such a case, counselling is required.

Here, three levels of Counselling is required: 1. Ist level is with Hari 2. IInd level of counselling is required with the Union Leader (if any) to keep the collective interest and the reputation of the company in mind 3. IIIrd level of counselling is required with his family members as they constitute of the afflicted party

If the counselling does not work, one should also identify a contingency plan or Plan B. In this case, the Contingency Plan would be – hire someone from his family for a compensatory role.

Note that the following options are out of scope and should be avoided: 1. Increase Hari’s salary so that he gives in and agrees to do the compensatory job 2. Status Quo – do not bother as long as the Company is making a profit 3. Replace Hari with someone else

1. Pinpoint the key issues to be solved and identify their cause and effects

2. Start broad and try to work through a range of issues methodically

3. Connect the facts and evidence and focus on the big picture

4. Discuss any trade-offs or implications of your proposed solution

5. Relate your conclusion back to the problem statement and make sure you have answered all the questions

1. Do not be anxious if you are not able to understand the situation well or unable to justify the problem. Read again, a little slowly, it will help you understand better.

2. Do not jump to conclusions; try to move systematically and gradually.

3. Do not panic if you are unable to analyze the situation. Listen carefully to others as the discussion starts, it will help you gauge the problem at hand.

All the best! Ace the GDPI season.

Related Tags

Why More Students Are Taking CAT 2024?

XAT 2025: XLRI Changes Exam Paper Pattern

CAT 2023 Slot 1 DILR Breakdown ft.Dr.Shashank Prabhu || DILR Dangal Ep.5 || CAT DILR Preparation

CAT 2023 vs 2022: Score vs Percentile Analysis & Sectional Cutoffs

Arsh's Winning Strategy: From 40 Percentile in CAT 2022 to 96.67 in CAT 2023

Mini Mock Test

LRDI 3- CAT Champions 2

LRDI 4 - CAT Champions 2

VARC-3 CAT Champions 2

Quants 3-CAT Champions 2

VARC-4 CAT Champions 2

Quants 2-CAT Champions 2

LRDI 2- CAT Champions 2

VARC-1 CAT Champions 2

Quants 1-CAT Champions 2

VARC-2 CAT Champions 2

LRDI 1- CAT Champion 2

Lesson 7 | Pre-Session Test | RC Application - 2

Lesson 6 | Pre-Session Test | RC Application - 1

Lesson 4 | Pre-Session Test | Option Elimination Skill

Lesson 3 | Pre-Session Test | Effective Reading Skill

CAT 2023 DILR SLOT 3

CAT 2022 DILR SLOT 1

CAT 2023 DILR SLOT 2

CAT 2023 DILR SLOT 1

CAT 2020 VARC SLOT - 3

CAT 2020 VARC SLOT 2

CAT 2020 VARC SLOT 1

CAT 2021 VARC Slot 3

CAT 2021 VARC Slot 2

CAT 2021 VARC Slot 1

CAT 2017 VARC SLOT- 2

CAT 2017 VARC SLOT- 1

CAT 2018 VARC SLOT- 2

CAT 2018 VARC SLOT- 1

CAT 2019 VARC SLOT- 2

Take Free Test Here

Aimcat 2519 live solving by shashank prabhu, founder - point99 (cat 100%iler | seasoned cat trainer).

By Team InsideIIM

How A Non-Engineer Went From 17%ile to 99+%ile In CAT

I made it to fms delhi with gap years ft.shayari || 99.21%iler cat 2023, best 4 months strategy to score 99+%ile in cat 2024 ft.pallav goyal (iim a), essential resources for cat 2024 & how much practice you need for 99%ile, cat 2023 slot 1 reading comprehension breakdown by 99.9%iler ft. karan agrawal (fms delhi), how to eliminate options in rc | cat varc tricks to score 99+ percentile ft. gejo sir, career launcher, subscribe to our newsletter.

For a daily dose of the hottest, most insightful content created just for you! And don't worry - we won't spam you.

Who Are You?

Top B-Schools

InsideIIM Gold

InsideIIM.com is India's largest community of India's top talent that pursues or aspires to pursue a career in Management.

Follow Us Here

Konversations By InsideIIM

TestPrep By InsideIIM

- NMAT by GMAC

- Exam Syllabus

- Score Vs Percentile

- Exam Preparation

- Explainer Concepts

- Free Mock Tests

- RTI Data Analysis

- Selection Criteria

- CAT Toppers Interview

- Study Planner

- Admission Statistics

- Interview Experiences

- Explore B-Schools

- B-School Rankings

- Life In A B-School

- B-School Placements

- Certificate Programs

- Katalyst Programs

Placement Preparation

- Summer Placements Guide

- Final Placements Guide

Career Guide

- Career Explorer

- The Top 0.5% League

- Konversations Cafe

- The AltUni Career Show

- Employer Rankings

- Alumni Reports

- Salary Reports

Copyright 2024 - Kira9 Edumedia Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved.

MBA admission: How to crack case-based group discussions?

- By:Surbhi Jain

- Date: 2018-11-27 14:13:32

Case studies or caselets are now an integral part of admissions to the MBA. Often, candidates should analyze small files during a group discussion (GD), instead of general topics. The idea is to examine the candidate's point of view, logical approach, quick thinking, and his problem-solving attitude before finalizing his/her candidature for the MBA program. The caselets do not require any prior knowledge of the subject. It is considered an effective way of judging the management qualities of a candidate required for admission to the B-School.

Read More- Predict your Percentile/Score through CAT Percentile/ CAT Score Predictor

Although the Top management institutes (IIMs) have suppressed the group discussions, various leading business schools still continue to conduct case-based GDs some of the institutes are- XLRI-Jamshedpur, SPJIMR, Mumbai and NMIMS, Mumbai, etc. So what happens in a caselet? Mentors will give 10 minutes to the candidates to read a case summary followed by 10 minutes to write whatever we understood after that there will be a group discussion of 20 minutes. Let us figure out more about GD-based case studies in management institutes:

A case study is all about analysis because everyone gives the same information and therefore starts from the same base.

The case study topics are mainly related to current affairs. Current socio-economic environment, government policies, innovations, global economic climate or socio-political debates prevalent in popular media. Learn about as many case study topics as possible.

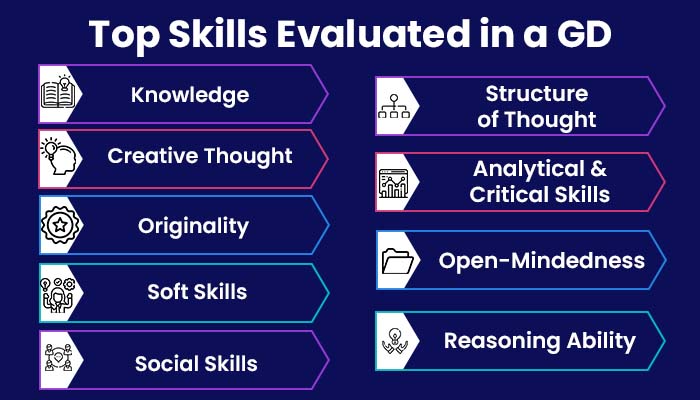

The purpose of these case-based GDs is to judge the knowledge, communication skills, leadership qualities and the ability of the candidate to make logical arguments and convince the opposing party, qualities needed to be a good manager.

Read more- GD/PI Tips for MBA Colleges in India

Here are some tips for solving case-based group discussions:

Refer to the topics covered in the GDs of your target institute. You can collect this information online or from coaching institutes. Take note of the topics covered over the years, it is very likely that the topics will go in the same direction this year as well.

Read newspapers, journals, magazines and watch current affairs programs to find out what's going on around you. Case-based GDs typically focus on business and economic issues that affect the social and political climate. Read editorials and articles based on hot topics, so you can use them while making your point of view during GD.

Meet up with your friends who are also MBA aspirants, form a group and hold a case-based group discussion. Exchange ideas, observe and develop confidence.

In case-based GDs, around five minutes are given to prepare, so use this time wisely. If the case is about a topic where the decision is to be made, quickly think of points to back your ‘to’ or ‘for’ stand and choose one. If the subject is such that a decision has already been made and the group has to decide whether it is right or wrong, re-choose aside after quickly weighing your points.

What should be the right approach?

Approach which can identify the crux of the problem, can logically analyze it and can suggest an alternate course of action to solve it, is the right approach. Know the steps that will lead you to solve it

Step1: Attentively read the caselet, following the important points Step2: Understand the objectives of the organization Step3: Get to the core of the problem and its causes Step4: Identify and focus on the obstacles and constraints of the issue in achieving the desired goals Step5: Find out the alternatives, analyze them and pick out the relevant ones. Step6: Filter all of the alternatives and choose the most appropriate one. Step7: Frame the course of action to implement the decision

Read more- CAT Score vs CAT Predictor

A few don’ts for caselet exercises-

- Do not be anxious and hyper even if you are not able to fully understand the situation or unable to identify the problem at first. read again it a little slowly, it will help you better understand.

- Do not jump on the conclusions; try to move step by step.

- Do not panic if you are unable to find an appropriate solution. Your analytical skills, the logical process of identifying the problem and the moving towards its solution will also be evaluated.

- Do not be in a hurry to speak without arriving at some logical analysis and solution strategy. When you speak, be relevant and to the point.

For more details and guidance you can reach at 7772954321 | 8818886504 and write us at [email protected]

Related Blog

SNAP 2022 - Know about it All (SNAP 2022 Eligibility, Important dates, Exam Pattern, Syllabus, Admit Card, Application Fees)

SNAP 2022 - Know about it All! (SNAP 2022 Eligibility, Important dates, Exam Pattern, Syllabus, Admit Card, Application Fees)

CAT 2018 Important dates, fees, Procedure & Eligibility

CAT 2018 Important dates , Procedure & Eligibility

Student login

Forgot password.

Colege login

College login.

Channel Partner Login

Join now for free

By clicking submit button, I agree to the terms of services and privacy policy .

Thanks for the registration, We have sent an email with verification link please verify your account.

And also please verify your mobile number enter otp here

Register here to get in touch with hundreds of colleges on our platform.

- News and Notifications

- Refund & Cancellation Policy

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy Policy

- College Predictor

- Best MBA Colleges in Delhi

- Best MBA Colleges In India

Have a Question

- +91 77729 54321

- [email protected]

- 24x7 Dedicated Custome Care Support -->

Head Office

405, Vibrant Twin Tower, Manorama Ganj, NH3, AB Road, Geeta Bhawan Square, Indore, Madhya Pradesh 452001

Phone: 964 444 0101 | 777 295 4321

Time: Mon-Sat:09:30AM - 06:30PM

Mumbai Office

Mumbai Office no. 303, Hari Om Plaza, M G Road, Near SGNP Main Gate, Sukurwadi, Borivali East, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400066

Phone: 771 881 7500 | 977 000 7700

© BookMyColleges.com. All Right Reserved. 2024

Stay Updated About All the Latest MBA News, Exams and B-schools.

You never know this might be what you have been looking for all around. get it now , exam details.

Tips for Discussion Group Leaders

Once the program begins, each discussion group is assigned a leader who serves as the facilitator for each case study

Here are some tips for leading an insightful and productive exchange.

Before you begin, make sure that all members understand the value of the discussion group process. You may find it helpful to have a brief conversation about the Discussion Group Best Practices listed above.

Think of yourself as a discussion facilitator. Your goal is to keep the group focused on moving through the case questions. Don't feel that you need to master all the content more thoroughly than the other group members do.

Guide the group through the study questions for each assignment. Keep track of time so that your group can discuss all the cases and readings, instead of being bogged down in the first case of the morning or afternoon.

The study questions are designed to keep the group focused on the key issues that will contribute to an effective discussion in the larger classroom meeting. Don’t let your peers stray too far into anecdotes or issues that aren't relevant.

If a subset of your living group appears to be dominating the discussion, encourage the less vocal members to participate. They'll be more apt to speak up if you ask them to share their unique perspectives on the topic at hand.

If you have questions about how to handle a specific situation that may arise in your group, please reach out to the faculty or staff for assistance. We’re here to help you get the most out of your group discussions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What can i expect on the first day, what happens in class if nobody talks, does everyone take part in "role-playing".

How To Facilitate A Case Study Workshop Session

A case study can be used as part of a training workshop to facilitate a learning point or as part of an assessment programme to gauge candidate’s response and analysis of situations. Case studies can be great for sharing experiences and reaffirming knowledge and understanding.

Here are some reasons to give a case study a try:

- increases awareness of a problem and helps teams formulate possible solutions.

- exchanges ideas and helps team members share past experiences.

- helps to analyse a problem and reach a decision as a team.

- facilitates and reaffirms key learning points.

Pre-printed scenario cards (optional)

Space Required:

Small. Classroom or training room

Group Size:

6 to 16 people

Total Time:

- 5 minutes to introduction and setup

- 10 minutes per case study for analysis and discussion (based on 4 case studies)

- 5 minutes for final review and case study debrief

Case Study Setup

Select the topic or theme that you were like to focus on during the training exercise. Prepare some possible scenarios or research articles related to the subject.

Case studies should be descriptions of events that really happened or fictional but based on reality. When leading the exercise, you can present the case study yourself, provide it in written form or even use videos or audio clips.

When I lead case studies sessions, I normally print the question on a piece of A4 paper and laminate them ready for workshop.

Case Study Instructions

From experience, I have found that a case studies session can be delivered two different ways.

The first way is to simply provide the group with a scenario and let them discuss it together as one big group.

The alternative is to split the group into smaller sub-groups and provide each group with the scenario. Once all groups have an opportunity to analyse and discuss the scenario, ask each group to present their findings back. This is a good way to get participants that are less likely to open up in bigger groups involved.

Look at your group and think about what will work best and give you the results you need.

When leading the case studies session, actively listen to discussion and provide necessary assistance to facilitate (guide) the analysis and discussion in the proper direction. Make sure you lead the discussion towards the learning objectives of the training workshop.

If you have people that conflicting views, then let them argue their points. If the discussion becomes too heated, stop them and summarise the discussion points and move on.

If everyone in the group agrees on something, or the discussion becomes stagnant then try playing devil’s advocate to get participants to look at the scenario from a different point of view.

When introducing the scenario, ask the group to think about the following 5 questions:

- What’s the problem?

- What’s the cause of the problem?

- How could the problem have been avoided?

- What are the solutions to the problem?

- What can you learn from this scenario?

Try to be flexible with your timings. If you need to stop a scenario early because the group become too heated or the group have explored the subject completely, stop them and summarise before moving on. If the scenario leads to valuable learning and you’re running out of time, allow an extra five minutes and skip another scenario.

Tips and Guidance

A good way to lead up to a case study is to present the scenario to the group at the end of the day and ask them to read up on the material and prepare in the evening. The first part of the following days’ workshop should then be the case study.

I like to lead a case study session by simply handed over the question cards and letting the group begin the discussion on their own. At the end of the discussion, I’ll summarise the key points – help them identify why the case study was important to the learning and move on to the next one.

If you’re discussing any sensitive subjects such as child protection etc then it is important to tell the group at the beginning of the case study. Explain that anything discussed exercise must not be mentioned again and if anyone needs to leave for a couple of minutes then they are more than welcome to.

Further Reading

10 Tips for Better Facilitation

How To Facilitate Group Discussions: The “Gallery” Exercise

Questions? Comments? Let us know in the comments below!

Related Posts

How To Play The Empire Game: Fun Group Game

Diving into the Depths: How to Play Sharks and Minnows

The Red Light Green Light Game

Thanks! This article helped me a lot!

Glad it was helpful!

Thanks – Helped! Have you any thoughts around case studies which are not based around a problem?

Gigi, I am glad this helped.

Can you elaborate on what you mean about the case studies not being based on a problem?

A big part of the value of this type of exercise is that you can ideally take emotions out of play and analyze an undesired situation or problem neutrally helping your team to better deal with these types of scenarios in real life when emotions could potentially flare up. If the person can realize the bigger picture and be equipped with productive ways to handle the situation then hopefully the outcome with be better in real life.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Free PDF: "5 Fun Team Building Activities"

Five of our favorite team building activities. Easy set up, printable instructions, and review questions.

Your Privacy is protected.

Get 30 of our best Team Building Activities in one PDF eBook!

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

bok_logo_2-02_-_harvard_left.png

Case Study At-A-Glance

A case study is a way to let students interact with material in an open-ended manner. the goal is not to find solutions, but to explore possibilities and options of a real-life scenario..

Want examples of a Case-Study? Check out the ABLConnect Activity Database Want to read research supporting the Case-Study method? Click here

Why should you facilitate a Case Study?

Want to facilitate a case-study in your class .

How-To Run a Case-Study

- Before class pick the case study topic/scenario. You can either generate a fictional situation or can use a real-world example.

- Clearly let students know how they should prepare. Will the information be given to them in class or do they need to do readings/research before coming to class?

- Have a list of questions prepared to help guide discussion (see below)

- Sessions work best when the group size is between 5-20 people so that everyone has an opportunity to participate. You may choose to have one large whole-class discussion or break into sub-groups and have smaller discussions. If you break into groups, make sure to leave extra time at the end to bring the whole class back together to discuss the key points from each group and to highlight any differences.

- What is the problem?

- What is the cause of the problem?

- Who are the key players in the situation? What is their position?

- What are the relevant data?

- What are possible solutions – both short-term and long-term?

- What are alternate solutions? – Play (or have the students play) Devil’s Advocate and consider alternate view points

- What are potential outcomes of each solution?

- What other information do you want to see?

- What can we learn from the scenario?

- Be flexible. While you may have a set of questions prepared, don’t be afraid to go where the discussion naturally takes you. However, be conscious of time and re-focus the group if key points are being missed

- Role-playing can be an effective strategy to showcase alternate viewpoints and resolve any conflicts

- Involve as many students as possible. Teamwork and communication are key aspects of this exercise. If needed, call on students who haven’t spoken yet or instigate another rule to encourage participation.

- Write out key facts on the board for reference. It is also helpful to write out possible solutions and list the pros/cons discussed.

- Having the information written out makes it easier for students to reference during the discussion and helps maintain everyone on the same page.

- Keep an eye on the clock and make sure students are moving through the scenario at a reasonable pace. If needed, prompt students with guided questions to help them move faster.

- Either give or have the students give a concluding statement that highlights the goals and key points from the discussion. Make sure to compare and contrast alternate viewpoints that came up during the discussion and emphasize the take-home messages that can be applied to future situations.

- Inform students (either individually or the group) how they did during the case study. What worked? What didn’t work? Did everyone participate equally?

- Taking time to reflect on the process is just as important to emphasize and help students learn the importance of teamwork and communication.

CLICK HERE FOR A PRINTER FRIENDLY VERSION

Other Sources:

Harvard Business School: Teaching By the Case-Study Method

Written by Catherine Weiner

- Utility Menu

GA4 tagging code

- Demonstrating Moves Live

- Raw Clips Library

- Facilitation Guide

Structuring the Case Discussion

Well-designed cases are intentionally complex. Therefore, presenting an entire case to students all at once has the potential to overwhelm student groups and lead them to overlook key details or analytic steps. Accordingly, Barbara Cockrill asks students to review key case concepts the night before, and then presents the case in digestible “chunks” during a CBCL session. Structuring the case discussion around key in-depth questions, Cockrill creates a thoughtful interplay between small group work and whole group discussion that makes for more systematic forays into the case at hand.

Barbara Cockrill , Harold Amos Academy Associate Professor of Medicine

Student Group

Harvard Medical School

Homeostasis I

40 students

Additional Details

First-year requisite

- Classroom Considerations

- Relevant Research

- Related Resources

- CBCL provides students the opportunity to apply course material in new ways. For this reason, you might consider not sharing the case with students beforehand and having them experience it in class with fresh eyes.

- Chunk cases so students can focus on case specifics and gradually build-up to greater complexity and understanding.

- Introduce variety into case-based discussions. Integrate a mix of independent work, small group discussion, and whole group share outs to keep students engaged and provide multiple junctures for students to get feedback on their understanding.

- Instructor scaffolding is critical for effective case-based learning ( Ramaekers et al., 2011 )

- This resource from the Harvard Business School provides suggestions for questioning, listening, and responding during a case discussion .

- This comprehensive resource on “The ABCs of Case Teaching” provides helpful tips for planning and “running” your case .

Related Moves

Experiencing the Case as a Student Team

Regulating the Flow of Energy in the Classroom

Designing Focused Discussions for Relevance and Transfer of Knowledge

- Testimonial

- Web Stories

Learning Home

Not Now! Will rate later

Practice Case Studies: Long

- The Exotic Melons: You are the manager (Worldwide Sales Cock and Bull Melons) in a Dubai-based company that deals in selling exotic fruits. Cock and Bull Melons are a special variety of melons that can be cultivated only on the sandy dunes surrounding the Cock and Bull oasis in the Sahara desert. Worldwide demand and supply have been quite stable so far at 100 melons a year, with the supply being just sufficient to cover the demand. Cock and Bull Melons have traditionally been sold to the sheikhs in the Middle East, and Hollywood and Bollywood actors and actresses. Their exorbitant prices take them out of reach of common people. In January 2002, the research centre at Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), India discovers that Cock and Bull melons can cure the fatal MarGaya syndrome in pregnant women, which kills both he mother and the child. Also, it can cure the fatal MaraGaya syndrome in diabetic patients. Both these symptoms are very rare. Unfortunately for you, in May 2002, the MaraGaya syndrome strikes 2000 people in America and the MarGaya syndrome strikes 1000 pregnant women in Sweden. 100 Cock and Bull melons are required to cure the 1000 cases in America while 100 are required to cure the Swedish problem. You know that the patients in both the countries cannot afford the high cost of Cock and Bull melon treatment. You also know that the revenues from treating patients would be much lower than selling them to sheikhs and film stars. You are in a real dilemma. What would you do?

- Confidential Information? Mr. SecretKeeper is a Corporate Head (HR) in a company. He is very nice and gets along well with all people. People often consult him for help and advice. One person (named “Mr. A”) approaches him for a job because he is right now jobless. Mr. SecretKeeper takes the guy's qualifications and asks him to come after a week however, since no job available. He keeps frequently postponing the job offer. Mr. A keeps visiting the HR head, Mr. Secret Keeper, often and becomes his close friend. Then, one day, Mr. A confides with the HR Head “I was in prison for 18 years for a crime that I had not committed. With two years remaining of the sentence, I ran away from jail. Even now, police is in look out for me.” Mr. SecretKeeper tells the person to go home and that he would give him a job. However as soon as he leaves, Mr. SecretKeeper calls up the police and gives the details of Mr. A and asks them to arrest Mr. A. Because of this betrayal of trust by the HR head, people in the organisation have started losing faith in him. A senior person in the office complains to the VP that the Mr. Secret Keeper has “broken faith”, so others could not come to him. Assume that you are the VP of the company. What would you do about the situation?

- Decisive Interview, GD & Essay prep

- GD: Topics 2021

- GD: Approach

- GD: Do's and Don'ts

- GD: Communications

- Solved GDs Topics

GD Introduction

- Types of GD topics: Techniques

- GD: Ettiquette

- GD: Content

- Solved Case Studies

Essential MBA GD Guide: Key Topics with Strategies Free

- Importance of Group Discussions

- Tips and Strategies to handle a GD

- Top 25 GD topics

- Free Download

- In a fix! You are the young dynamic, blue-eyed boy (girl) in a firm, which is a known leader in the industrial oils business. Under your leadership, the company has done extremely well in a slow, sluggish, mature market and has also effectively warded off competition from the superior industrial oil segment. However, as a young blooded individual, you decide that the company should branch into something more glamorous and contemporary. You manage to convince the top management to get into the film-making business. The film-making business is started as another division, where the systems and processes are kept the same to have uniformity across businesses. You manage to hire top talent in this field Mr. A, Mr. B and Mr. C from different competitors. You have big hopes from the trio as these people have come together as a team for the first time. You grant every freedom to these people to recruit their own subordinates. Barely a month after the film-making business has started, you are in a fix! Mr. B throws his cap, sheds a zillion tears and tells you in a choked voice that he would rather die than continue with your business. A couple of months later Mr. C blames your policies and quits. Your six monthly profit and loss statement shows that film-making business had been a horrific disaster. The only remaining member of the star trio, Mr. A says that the business is slightly out of form and that he might deliver if you grant him complete freedom. You can now see your own future as dark as the industrial oils your company specializes in. You are wondering what went wrong and what should you do now?

- Tension on the job: Sujit Bhattacharyya (Bhola) had been an exceptionally bright student throughout his studies at IIT-Kharagpur. He devoted four years in pursuit of academic excellence. He had very few friends. Few peers liked him, but he was the darling of all his professors. Bhola joined TELCO from the campus as production supervisor in charge of vehicle assembly. Bhola used to manage shop floor operations consisting of truck assembly and in a shift 30-33 operator used to report to him. The IQ level of a typical operator could be compared to that of a class VIII student, but years of experience had made them confident about their job. GRAB THE OFFER: Kick start Your Preparations with FREE access to 25+ Mocks, 75+ Videos & 100+ Chapterwise Tests. Sign Up Now The operators, by virtue of doing the same job for so many years, had developed a highly robotic style of functioning and were highly resistant to change. The trade union was powerful and exercised a lot of leverage with the management, to secure incentives and overtime payment, which were fixed at a uniform rate across the departments. Nilesh was an operator in charge of front axle assembly. The number of trucks that rolled out of the factory was equal to the number of axles assembled. Thus, Nilesh was looking after a highly sensitive assembly operation. Nilesh, lately, had lost a lot of money in the stock market, had frequent quarrels with his wife and many times used to come drunk to the shop floor. His abrasive behavior had caused a lot of worry to Bhola. Nilesh also started absenting himself from duty and became casual in his approach. Subsequently, Nilesh was transferred to the quality control department to reduce his physical workload. Bhola found it very difficult to find a suitable replacement for Nilesh in the assembly area. He had to frequently interchange workers who were unable to cope with the high pressure work at the axle assembly. They deliberately started going slow, and thereby, affected productivity. Bhola did his best to pinpoint the problem. He was under tremendous pressure from the top to increase productivity to previous levels. The workers started demanding additional incentives and overtime payments. The management, on the other hand, was opposed to any change in the incentive structure. Bhola was helpless. He tried his best and at times did the work himself. The workers, sensing that Bhola had little control over them, became more aggressive and further slowed their work. Bhola suffered an emotional breakdown and had to stay away from work for two months. Discuss what the main issues in the case are and what would be your approach in this situation.

- Tuna-Tuna Lactuna!: The Minicoy Canning Factory (henceforth MCF) was set up by the Lakshadweep administration in 1969 with an aim to step up fishery production, provide employment and enable fishermen to sell their excess fish for better returns. MCF could produce only up to 150,000 cans per year because of labour constraint. However, due to excess production, by September 2001, MCF had accumulated an unsold inventory of 150,000 cans amounting to Rs. 12,807,700. In 2001, 64,322 cans were sold resulting in a turnover of Rs. 6,302,500 and a profit of Rs. 810,380. Competition for MCF came from Integrated Fisheries Project (henceforth IFP), a government undertaking set up with an aim to introduce and popularize diversified fishery products in rural and urban markets. MCF canned a type of tuna called Skipjack tuna, whose meat was harder and different in taste as compared to Yellow fin tuna canned by IFP. The distributors felt that higher price of Skipjack tuna was the culprit for lower sales vis-à-vis IFP. The higher price was on account of higher overheads for MCF attributed to lower volumes. IFP also had a stronger dealer network and a much larger promotion budget. The demand for canned tuna is concentrated in upcountry areas. However, the sale of MCF's tuna to these regions has been low. Sales enquiries had also been received from the Middle East, but no action had been taken on them. Markets other than the retail market were also being explored. The management of MCF was pondering over what the problem was and what could be done to resolve it amicably, both in the short term as well as in the longer term.

- Et tu Brutus!: Yahan Gadbad Inc. is a reputed multinational that specialized in organizing beauty pageants. The protagonists of this piece, besides you (of course), are Mr. Bhartus, the HR Manager and Mr. BigMouth, the flamboyant hospitality manager. Mr. BigMouth has been in Yahan Gadbad Inc. for over a decade now, during which he has successfully organized half a dozen pageants at exotic locales around the world. People in Yahan Gadbad swear by his integrity and professionalism and he has been the role model in the company for the last decade. Mr. Bhartus and Mr. BigMouth were good friends. One day after they had had a drink too many, Mr. BigMouth said to Mr. Bhartus, “Bhartu, I have something to confess to you. Bhartu dear, please listen to me as a friend and not as an HR manager”. “Of course Biggie!” said Mr. Bhartus, “I have big stomach. I can digest any secret”. Mr. BigMouth then said, “Do you remember the pageant we had in Polynesian Islands? You know, Bhartu the human heart is frail. I kind of got bowled over by a contestant. We had a week of debauchery. I rigged the contest to help her get the second runners up title”. In spite of the promise made to Mr. BigMouth, Mr. Bhartus comes to you (President, Yahan Gadbad Inc.) with the information. You think aloud, “Damn! What do I do now? The HR department handles confidential information and this fool could not keep a secret. On the other hand… God! Please guide me!”

- Student's BIG problem: In an institute AIM, the students' council is selected by a voting wherein each student is allocated a vote for each position in the council. The council is supposed to undertake activities of students' interests. Each student pays Rs. 50 per year towards council dues. Extending the brief of the council, it decides to add responsibilities and projects. As a first, it introduces a scheme for students wherein it provides them stationary and hosiery at a subsidized price. This is to be done on a no-profit no-loss basis. Initially, it is done only for a select group of students as a pilot exercise. Extending in the first month, the council has a sale of Rs.3500. They make a profit of Rs. 300. Seeing this, the council decides to expand its store for the complete instituted. They buy goods worth Rs.15000 for the first time and Rs 10000 the second time. In order to buy these goods, it takes loan of Rs.8000 at an interest of 18% per annum. Rumors of bungling of money start floating around the campus. Some council members are alleged to have taken money from the store and the council funds. As a result of these rumors, some students begin to boycott the council and start to doubts its intentions. In addition, they allege that the store was supposed to be on a no profit no-loss basis, but still it aimed at earning profits. On complaints to the institute authorities, the store is closed for business till further notice, pending an internal investigation into the matter. As a result of the store closure, the council is left with stocks of Rs.13500. In addition, the council also has to repay Rs. 8000 plus interest to the financial institution. In the present scenario, what could be the possible solutions?

- The Video Games Case You are the CEO of a large, diversified entertainment company. A division of your firm manufactures video games. The division is the third largest manufacturer of hardware in the industry and has a 10% market share, with the top two having 40% and 35% respectively. The industry growth has been strong, though over the last few months, the overall industry sales growth has slowed a bit. The division's sales have increased rapidly over the last year from a relatively small base. Current estimate is annual sales of 500,000 units for your division. The selling price of the basic Video Game unit (hardware) is Rs. 1000. The current cost of manufacturing a unit is Rs. 700, excluding the marketing costs. The top two competitors are estimated to have a 10 to 15% cost advantage currently. The division currently exceeds corporate return requirements; however, margins have recently been falling. The product features are constantly developed (e.g., new type of remote joy stick), to appeal to the segments of the market. However, the division estimates much of the initial target market (young families) has now purchased the video game hardware. No large new user segments have been identified . Recently, a request has come to you, the CEO, for approval of Rs. 20 Cr. for tripling the division's capacity. The requested expansion will also reduce the cost of manufacture by 5 to 7 % from the present value. Should you approve the expansion?

- Bow Bow! You are the General Manager (Procurement) in a large, international trading firm, Idhar Udhar Inc. Your current responsibilities involve procurement of rats, dogs and cats from the dark interiors of Africa and selling them at a profit in developed countries as pets. Of these products, dogs are extremely seasonal, being available only from the middle of May to the end of August. You are expecting a bumper season this time around. Also, the price of dogs in the developed countries being at an all time high, you are expecting record profits which would, in a swift move, also put your career on the fast track. Bang in the middle of the procurement season, an internal audit reveals that Mr. Ghotala Doggy, your star manager (Procurement Dogs) has siphoned off Rs. 20,000 from company funds. Mr. Doggy has excellent relations with the suppliers and you know that it would be impossible to meet targets without him. On your questioning, Mr. Doggy reveals that he had taken the money for paying the medical bills of his daughter, Ms. Bitchy Doggy, who was seriously ill. Following this incident, audits were conducted in other divisions and irregularities were found there also. However, since your division was the first where such an incident took place, people are looking at you to set a precedent. Your company lays extreme emphasis on personal integrity and this is the first time in the company's century old history that such an incident has occurred. What would you do?

- The Dilemma! You are the GM (HR) of a small firm involved in manufacturing and selling AM/FM radios. Of late, sales of radios have declined due to emergence of TV, Cable etc. The main departments are the production, marketing and accounting. Bharat is a clerk in the accounting department. He has been with the company for 15 years now. He knows the job well, but of late, is increasingly coming late for work. He is married with two children and he cites family problems as the cause of late arrival on job. Every time he promises to mend his ways, but has not done so till date. Om is the production supervisor. He has been with the company since its inception 30 years ago and commands a lot of respect from his workers. But, age is catching up on him fast. Also, the much younger workers are increasingly questioning and resisting his authority. If chucked out of the job, it might be difficult for him to find another job at his age. He is due to retire in another two years. Jai is a young MBA in marketing from a major B-School. He joined the company a year ago and started new advertising and marketing campaigns, at a tremendous cost to the company. His plans met with initial success, but then the sales were back to its initial levels. He handles the company's dealers in the northern region. But, his initial success seems to have gone to his head. He increasingly feels discontented when some of his new ideas are turned down by the higher management. Jagdish is a marketing executive with the company for the last 6 years. Though not an MBA, he was still hired for the job due to his sharp acumen. In the years to follow, with an increasing mumber of MBA's joining the company, he was denied promotion last year. This caused bouts of deep depression, from which he recovered after two months. After that, he has been complacent in his work and sometimes even rude to the customers. In a desperate cost-cutting measure, your company decides that it must reduce the workforce as a first measure. These four are the possible candidates for job termination. You, as a group, have to decide how many you will sack, which ones, and why?

- Group Discussions

- Personality

- Past Experiences

Most Popular Articles - PS

100 Group Discussion (GD) Topics for MBA 2024

Solved GDs Topic

Top 50 Other (Science, Economy, Environment) topics for GD

5 tips for starting a GD

GD FAQs: Communication

GD FAQs: Content

Stages of GD preparation

Group Discussion Etiquettes

Case Study: Tips and Strategy

MBA Case Studies - Solved Examples

Practice Case Studies: Short

5 tips for handling Abstract GD topics

5 tips for handling a fish market situation in GD

5 things to follow: if you don’t know much about the GD topic

Do’s and Don’ts in a Group Discussion

5 tips for handling Factual GD topics

How to prepare for Group Discussion

Evidence-Based Case Study Guidelines: Group Dynamics

Group Dynamics issues an open call for authors to submit an Evidence-Based Case Study for possible publication. Developing such a series of Evidence-Based Case Studies will be useful in advancing the evidence for group psychology and group psychotherapy. Group practice for this call is defined broadly to include therapy groups, teams, organizations and other group contexts. The goal of these Evidenced-Based Case Studies is to integrate verbatim case material from the group with standardized, empirical measures of process and outcome evaluated at different times during the life of the group, team or organization. Authors should describe vignettes highlighting key interventions, processes and mechanisms regarding their specific approach in the context of empirical scales.

Such an investigation will provide much needed information to bridge the gap between research and practice. Evidence-based case studies will also provide an important model of how to integrate basic research into applied work in therapy, team, and organizational contexts. This will open an avenue for publication to those in full time private practice, those who work primarily as consultants or organizations and teams that integrate research measures into their applied work. Finally, this approach to studying group phenomena may provide a list of systematic case studies from various forms of treatment and interventions that meet the American Psychological Association's criteria for Evidence-Based Practice (APA, 2006) as well as the Clinical Utility dimension in the Criteria for Evaluating Treatment Guidelines (APA, 2002).

Authors who are interested in preparing an Evidence-Based Case Study must follow these guidelines:

- The report must include the assessment (from the individual group member or independent rater perspective at the group level, but not only the therapist/leader) of at least two standardized empirical outcome measures related to team, organization or group objective. Optimally, such a report would include several outcome measures assessing a wide array of functioning such as: global functioning, team or organizational objectives, target symptoms, subjective well-being, interpersonal functioning, social/occupational functioning and measures of personality.

- The report must also include at least one empirical process measure (e.g., therapeutic alliance, session depth, emotional experiencing, team functioning, organizational cohesion) evaluated on at least three separate occasions.

- At minimum, specific outcome data should be presented using standardized mean difference (i.e. effect size) and clinical significance methodology (i.e. unchanged, reliable change, movement into functional distribution, clinically significant change and deterioration [see Jacobson et al. 1999]). Group Dynamics encourages submission of both successful and unsuccessful cases. In addition, it might be instructive to compare and contrast the technical interventions that occurred during a positive change case with that of an unchanged or deteriorated case from the same approach. The Evidence-Based Case Study section is not necessarily for advanced statistical time series analyses of process or outcome data, although such articles would be welcomed. Simple analyses of standardized outcome measures by way of clinical significance and effect size methods are sufficient.

- Verbatim vignettes with several group participant and therapist/leader turns highlighting key interventions, processes, and mechanisms of change must be provided. Discussion of any therapeutic or group-level interventions should not be presented only from a global or abstract perspective.

- Manuscripts must be within the journal word limit, as indicated on the journal website .

- Appropriate informed consent must be obtained from participants, and the study must be approved by an internal review board. The author must indicate that vignettes were sufficiently de-identified to protect confidentiality and privacy.

The following provide examples of what an Evidence-Based Case Study article might look like:

- Granasen, M. & Andersson, D. (2016). Measuring team effectiveness in cyber-defense exercises: A cross-disciplinary case study, Cognition, Technology & Work, 18 , 121–143. This study reported on simulated exercises to assess team functioning and effectiveness in repelling cyberattacks. Team performance (outcome), team cognition (processes within teams) were assessed and reported. The authors provided recommendations to enhance team performance. However, missing from this case study were vignettes to illustrate the concepts.

- Maxwell, K., Callahan, J. L., Holtz, P., Janis, B. M., Gerber, M. M., & Connor, D. R. (2016). Comparative study of group treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychotherapy, 53 , 433-445. The authors assessed a new potential group treatment for PTSD compared to cognitive processing therapy (CPT) as a pre-cursor to a randomized controlled trial. Two groups from each treatment type were compared. The authors measured outcomes but did not provide process measures. Several clinical vignettes illustrate the treatments.

- Tasca, G. A., Foot, M., Leite, C., Maxwell, H., Balfour, L., & Bissada, H. (2011). Interpersonal processes in psychodynamic-interpersonal and cognitive behavioral group therapy: A systematic case study of two groups. Psychotherapy, 48 , 260-273. Outcomes were measured outcomes pre- and post-treatment (effect sizes and reliable change indices) comparing two group therapists who were highly adherent to their specific treatment approach. The authors measured interpersonal processes at three time points from observer ratings of video recordings. Outcomes were measured using standardized scales. Clinical vignettes illustrated the differing interpersonal styles between the two group therapists.

Authors who have conducted an effectiveness or efficacy trial on a particular type of intervention in which they collected standardized process and outcome measures in addition to the use of audio/videotape of sessions should consider submitting an Evidence-Based Case Study. Likewise, a clinician in private practice, or a team or organizational consultant who would like to add these elements at the start of a new or existing group or team should also consider submitting an Evidence-Based Case Study.

Group Dynamics will begin accepting submissions for Evidence-Based Case Studies starting January 2019. Anyone who may have an interest in submitting an Evidence-Based Case Study is encouraged to contact the editor .

American Psychological Association, (2002). Criteria for evaluating treatment guidelines. American Psychologist, 57 , 1052–1059.

American Psychological Association, (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61 , 271–285.

Jacobson, N., Roberts, L., Berns, S., & McGlinchey, J. (1999). Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: Description, application, and alternatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67 , 300–307.

This Is What You Need to Know to Pass Your Group Case Interview

- Last Updated January, 2024

If you’re on this page, chances are you’ve been told you’re scheduled for a group interview.

After practicing for weeks to get good at cracking a normal case interview, hearing you have a group interview might make you feel like you’ve scaled a huge mountain only to find that there’s an even higher peak beyond it that you need to climb.

Group case interviews present some different challenges than individual cases, but if you know what those challenges are, you can overcome them.

We’ll tell you how.

In this article, we’ll cover what a group case interview is, why consulting firms use them, the key to passing your group interview, and tell you the 6 tips on group interviews you need to know.

If this is your first time to MyConsultingOffer.org, you may want to start with this page on Case Interview Prep . But if you’re ready to learn everything you need to know to pass a group case, you’re in the right place.

Let’s get started!

What is a Group Case Interview?

The group needs to come to a collective point of view on what the client’s problem is, how to structure their analysis, and what the final recommendation should be.

The group should also agree on how the analysis of the case will be conducted at a high level, but the actual number-crunching will need to be divided between group members in order to complete the work in the allotted time.

The group’s analysis and recommendation will be presented to one or more interviewers.

Why Do Consulting Firms Use Group Case Interviews?

It can feel difficult to trust your team members when you know that you’re all competing for the same job, but that’s what the group case is about — it tests teamwork skills in a high-stakes environment.

Management consultants are hired to solve big, thorny business problems, ones that require the work of multiple people to solve.

While there is a hierarchy on consulting teams with a partner leading the work, consulting partners simultaneously manage multiple clients or multiple studies at one large client.

They won’t work with your team every day and in their absence, the team still needs to be able to work together effectively.

Even if a partner is leading a team’s problem-solving discussion, each consultant has a responsibility to make sure the team’s best thinking is being put forward to help the client.

Ideas are both expected from each member of the team and valued.

Even the newest analyst has a contribution to make.

T he analyst may have been the person to analyze the data and therefore be closest to the information that will drive the solution to the problem.

The flat power-structure of the team makes it critical that each consultant works well with others on teams.

In assessing each member of a group case team, interviewers will ask themselves:

Does each of the recruits listen as well as lead?

Are they open to other peoples’ ideas?

Can they perform independent analysis and interpret what impact their work has on the overall problem the team is trying to solve?

Can they persuade team members of their points of view?

The Key to Passing the Group Case: Make Sure Your Group Is Organized

A group case must be solved by going through the same 4 steps as individual cases : the opening, structuring the problem, the analysis, and the recommendation.

Your team should break down the time you have to solve the case into time allotted to each of these steps to ensure you don’t spend too long in one area and not reach a recommendation.

Make sure the team agrees on a single statement of the client’s problem.

Take the time for everyone to read the materials, take notes, and suggest what they think is the key question(s) that need to be solved in this case.

Write it on a whiteboard or somewhere else to ensure there’s agreement. You can’t solve the problem together if you don’t agree on what the problem is.

Usually, someone in the group will take the lead on organizing the group.

If no one does, this is your opportunity to demonstrate your leadership and teamwork skills, but if there are people fighting over the leadership position (unlikely since everyone is on their “best behavior”), then contribute and don’t worry that you aren’t “leading” the discussion just yet.

Create a clear, MECE structure to analyze the problem.

This is even more important to solving a group case than an individual one because you need to make sure that when the group breaks up so each member can perform part of the analysis, all the issues are covered and there’s not duplicated effort between team members.

After your group structures the problem, split up the analysis that needs to be done between members of the group.

If no one suggests breaking up the analysis, then volunteer the idea. Be sure to explain how each person’s piece fits into the team effort.

Each person should do their analysis independently to ensure there is sufficient time to complete all the required tasks, though the team should regroup briefly if someone has a problem they need help with or comes up with an insight that could influence the work other group members are doing.

While you do your own analysis, you’ll need to demonstrate you understand the bigger picture by involving your teammates, sharing how your findings impacts their work, and articulating how all the insights lead to an answer to the client’s problem.

After everyone has completed their analysis, the group should come back together so everyone can report their results and the group can collectively come to a recommendation to present to interviewers.

In addition to the normal 4 parts of the case, group cases usually require you to present your recommendation to the interviewer(s).

Be sure to build time into your schedule for creating slides, deciding who presents what, and practicing your delivery.

Many groups fail because they begin their presentation without deciding who has which role.

In consulting, this is like going into a client meeting without knowing who is presenting which slide to the client and makes your team look unprofessional.

Presentation

Start with your recommendation and then provide the key pieces of analysis and/or reasoning that support it.

Again, the work will need to be divided between team members to ensure you get slides written in the allotted time.

For more information on writing good slide presentations, see Written Case Interview page.

6 Tips to Pass Your Group Case Interview

Tip 1: organize your team.

A disorganized team will not be able to complete their analysis and develop a strong recommendation in the time allotted.

See the previous section for the steps the group needs to complete to solve the case.

If someone else does take charge, don’t fight for control.

Show leadership by making points that help to move the team’s problem solving forward, not fighting so that it goes backwards.

Tip 2: Move the Problem-Solving Forward

With multiple team members trying to contribute and express their point of view, it’s possible to have a lot of discussion without getting closer to a solution to the client’s business problem. You can overcome this by:

- Summing up what the team has agreed on so far,

- Providing insight into how the team’s discussion impacts the problem you’re tasked with solving, and/or

- Steering the team to discuss the next steps.

If it feels like the team is rehashing the same topics, use these options to move the problem solving forward.

Tip 3: Make Fact-Based Decisions

It’s okay to disagree with team members but always disagree like a consultant. Challenge teammates’ ideas with data, not opinions.

If there is analysis that needs to be done to determine which point of view is correct, table the discussion until the analysis has been completed.

Tip 4: Don't Steamroll Teammates

As mentioned earlier, consulting teams value the ideas and input of every team member.

Because of this, cutting off, interrupting or talking over other team members is more likely to get you turned down for a consulting job than hired.

The quality of your contribution to group discussions is more important than the quantity (or air time) you consume.

Demonstrate your collaboration and interpersonal skills.

Tip 5: Remain Confident When the Team Presents

Keep your poker face on even if your teammates don’t make every point the way you would have made it.

Like steamrolling teammates in discussions, frowning or shaking your head as they present will make it look like you’re not a team player.

Tip 6: Remember, Everyone Can Get Offers

In many jobs, there is only one position open.

At consulting firms, a class of new analysts and associates is hired each year.

There aren’t quotas regarding hiring only one person from a group interview team, so working cooperatively to solve the problem is a better strategy than undermining other members of your group to appear smarter than they are.

We’ve seen group interviews where no one gets a job offer and that can be because teammates undermine each other.

Don’t Over-Invest in Prepping for a Group Case Study Interview

Like the written case interview , group cases come up infrequently.

The 2 most common types of case interviews are individual interviews: the candidate-led interview or the interviewer-led interview.

In the candidate-led interview , the recruit is responsible for moving the problem solving forward. After they ensure they understand the problem and structure how they’d approach solving it, they pick one piece of the problem to start drilling down on first. Candidate-led cases are commonly used by Bain and BCG.

In the interviewer-led interview , the interviewer will suggest the first part of the case a recruit should probe after they have presented their opening and structured the problem. Interviewer-led interviews are commonly used by McKinsey .

Because individual cases are much more common than group cases, don’t spend time preparing for a group case unless you’re sure you’ll have one.

If you’re invited to take part in a group case interview, your preparation on individual cases will ensure you have a good approach cracking the case.

At this point, we hope you feel confident you can pass your group case interview.

In this article, we’ve covered what a group case interview is, why consulting firms use them, the key to passing your group interview, and the 6 tips on group interviews you need to know.

Still have questions?

If you have more questions about group interviews, leave them in the comments below. One of My Consulting Offer’s case coaches will answer them.

People prepping for a group case interview have also found the following other pages helpful:

- Case Interview Math ,

- Written Case Interview , and

- Bain One Way Interview .

Help with Case Study Interview Preparation

Thanks for turning to My Consulting Offer for advice on case study interview prep. My Consulting Offer has helped almost 85% of the people we’ve worked with get a job in management consulting. We want you to be successful in your consulting interviews too.

If you want a step-by-step solution to land more offers from consulting firms, then grab the free video training series below. It’s been created by former Bain, BCG, and McKinsey Consultants, Managers and Recruiters.

It contains the EXACT solution used by over 500 of our clients to land offers.

The best part?

It’s absolutely free. Just put your name and email address in and you’ll have instant access to the training series.

© My CONSULTING Offer

3 Top Strategies to Master the Case Interview in Under a Week

We are sharing our powerful strategies to pass the case interview even if you have no business background, zero casing experience, or only have a week to prepare.

No thanks, I don't want free strategies to get into consulting.

We are excited to invite you to the online event., where should we send you the calendar invite and login information.

Center for Teaching Innovation

Facilitating discussions.

Facilitating a longer discussion in a small class or seminar requires many skills in planning, asking good questions, listening, managing the time, keeping an eye on the group dynamics, and thinking on your feet to respond. It takes time and experience to become a good discussion facilitator. Observing how other instructors facilitate discussion, either by asking a colleague if you can observe a class or through participating in the Big Red Teaching Days class observation program, is one way to enhance your skills. Below, you can find strategies to plan, structure, and lead a discussion.

Asking Good Questions as a Facilitator

Shape your questions to practice intellectual skills . When creating your question prompts, reflect on your learning outcomes and the intellectual skills you are helping the students to practice. For example, you may want students to practice critiquing the study methods or use of evidence, examining different perspectives, identifying assumptions or biases, seeing themes or patterns, or recognizing rhetorical moves. Write your questions with your learning outcomes in mind.

Ask one question at a time and then wait . Be careful about making a question too complex, stacking questions (asking two or more questions at one time), or over-explaining and rephrasing your question. Ask one question and then wait 10-30 seconds or give students some time to write. A complex question needs thinking time. Allowing more thinking time encourages greater participation from everyone – not just from the students who can quickly jump into a discussion.

Organizing discussion questions Consider organizing your questions into the categories of ‘warming up,’ ‘exploring’, and ‘wrapping up’.

Warm-up: Give students an opportunity to start thinking about a topic or question. This might include individual writing or thinking time or a discussion prompt to discuss with a partner. Some example warm-up questions include.

- Try to write a one sentence summary of this topic/reading/case study etc.

- Write down three questions you have about this topic/reading/film/art work/material etc.

- What stood out to you in the reading/film/music etc.?

- How do you feel about the argument or perspective presented? Do you agree or disagree and why?