9.1 Null and Alternative Hypotheses

The actual test begins by considering two hypotheses . They are called the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . These hypotheses contain opposing viewpoints.

H 0 , the — null hypothesis: a statement of no difference between sample means or proportions or no difference between a sample mean or proportion and a population mean or proportion. In other words, the difference equals 0.

H a —, the alternative hypothesis: a claim about the population that is contradictory to H 0 and what we conclude when we reject H 0 .

Since the null and alternative hypotheses are contradictory, you must examine evidence to decide if you have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis or not. The evidence is in the form of sample data.

After you have determined which hypothesis the sample supports, you make a decision. There are two options for a decision. They are reject H 0 if the sample information favors the alternative hypothesis or do not reject H 0 or decline to reject H 0 if the sample information is insufficient to reject the null hypothesis.

Mathematical Symbols Used in H 0 and H a :

| equal (=) | not equal (≠) greater than (>) less than (<) |

| greater than or equal to (≥) | less than (<) |

| less than or equal to (≤) | more than (>) |

H 0 always has a symbol with an equal in it. H a never has a symbol with an equal in it. The choice of symbol depends on the wording of the hypothesis test. However, be aware that many researchers use = in the null hypothesis, even with > or < as the symbol in the alternative hypothesis. This practice is acceptable because we only make the decision to reject or not reject the null hypothesis.

Example 9.1

H 0 : No more than 30 percent of the registered voters in Santa Clara County voted in the primary election. p ≤ 30 H a : More than 30 percent of the registered voters in Santa Clara County voted in the primary election. p > 30

A medical trial is conducted to test whether or not a new medicine reduces cholesterol by 25 percent. State the null and alternative hypotheses.

Example 9.2

We want to test whether the mean GPA of students in American colleges is different from 2.0 (out of 4.0). The null and alternative hypotheses are the following: H 0 : μ = 2.0 H a : μ ≠ 2.0

We want to test whether the mean height of eighth graders is 66 inches. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Fill in the correct symbol (=, ≠, ≥, <, ≤, >) for the null and alternative hypotheses.

- H 0 : μ __ 66

- H a : μ __ 66

Example 9.3

We want to test if college students take fewer than five years to graduate from college, on the average. The null and alternative hypotheses are the following: H 0 : μ ≥ 5 H a : μ < 5

We want to test if it takes fewer than 45 minutes to teach a lesson plan. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Fill in the correct symbol ( =, ≠, ≥, <, ≤, >) for the null and alternative hypotheses.

- H 0 : μ __ 45

- H a : μ __ 45

Example 9.4

An article on school standards stated that about half of all students in France, Germany, and Israel take advanced placement exams and a third of the students pass. The same article stated that 6.6 percent of U.S. students take advanced placement exams and 4.4 percent pass. Test if the percentage of U.S. students who take advanced placement exams is more than 6.6 percent. State the null and alternative hypotheses. H 0 : p ≤ 0.066 H a : p > 0.066

On a state driver’s test, about 40 percent pass the test on the first try. We want to test if more than 40 percent pass on the first try. Fill in the correct symbol (=, ≠, ≥, <, ≤, >) for the null and alternative hypotheses.

- H 0 : p __ 0.40

- H a : p __ 0.40

Collaborative Exercise

Bring to class a newspaper, some news magazines, and some internet articles. In groups, find articles from which your group can write null and alternative hypotheses. Discuss your hypotheses with the rest of the class.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute Texas Education Agency (TEA). The original material is available at: https://www.texasgateway.org/book/tea-statistics . Changes were made to the original material, including updates to art, structure, and other content updates.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/statistics/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Barbara Illowsky, Susan Dean

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Statistics

- Publication date: Mar 27, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/statistics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/statistics/pages/9-1-null-and-alternative-hypotheses

© Apr 16, 2024 Texas Education Agency (TEA). The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Hypothesis Testing: Uses, Steps & Example

By Jim Frost 4 Comments

What is Hypothesis Testing?

Hypothesis testing in statistics uses sample data to infer the properties of a whole population . These tests determine whether a random sample provides sufficient evidence to conclude an effect or relationship exists in the population. Researchers use them to help separate genuine population-level effects from false effects that random chance can create in samples. These methods are also known as significance testing.

For example, researchers are testing a new medication to see if it lowers blood pressure. They compare a group taking the drug to a control group taking a placebo. If their hypothesis test results are statistically significant, the medication’s effect of lowering blood pressure likely exists in the broader population, not just the sample studied.

Using Hypothesis Tests

A hypothesis test evaluates two mutually exclusive statements about a population to determine which statement the sample data best supports. These two statements are called the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . The following are typical examples:

- Null Hypothesis : The effect does not exist in the population.

- Alternative Hypothesis : The effect does exist in the population.

Hypothesis testing accounts for the inherent uncertainty of using a sample to draw conclusions about a population, which reduces the chances of false discoveries. These procedures determine whether the sample data are sufficiently inconsistent with the null hypothesis that you can reject it. If you can reject the null, your data favor the alternative statement that an effect exists in the population.

Statistical significance in hypothesis testing indicates that an effect you see in sample data also likely exists in the population after accounting for random sampling error , variability, and sample size. Your results are statistically significant when the p-value is less than your significance level or, equivalently, when your confidence interval excludes the null hypothesis value.

Conversely, non-significant results indicate that despite an apparent sample effect, you can’t be sure it exists in the population. It could be chance variation in the sample and not a genuine effect.

Learn more about Failing to Reject the Null .

5 Steps of Significance Testing

Hypothesis testing involves five key steps, each critical to validating a research hypothesis using statistical methods:

- Formulate the Hypotheses : Write your research hypotheses as a null hypothesis (H 0 ) and an alternative hypothesis (H A ).

- Data Collection : Gather data specifically aimed at testing the hypothesis.

- Conduct A Test : Use a suitable statistical test to analyze your data.

- Make a Decision : Based on the statistical test results, decide whether to reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject it.

- Report the Results : Summarize and present the outcomes in your report’s results and discussion sections.

While the specifics of these steps can vary depending on the research context and the data type, the fundamental process of hypothesis testing remains consistent across different studies.

Let’s work through these steps in an example!

Hypothesis Testing Example

Researchers want to determine if a new educational program improves student performance on standardized tests. They randomly assign 30 students to a control group , which follows the standard curriculum, and another 30 students to a treatment group, which participates in the new educational program. After a semester, they compare the test scores of both groups.

Download the CSV data file to perform the hypothesis testing yourself: Hypothesis_Testing .

The researchers write their hypotheses. These statements apply to the population, so they use the mu (μ) symbol for the population mean parameter .

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ) : The population means of the test scores for the two groups are equal (μ 1 = μ 2 ).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ) : The population means of the test scores for the two groups are unequal (μ 1 ≠ μ 2 ).

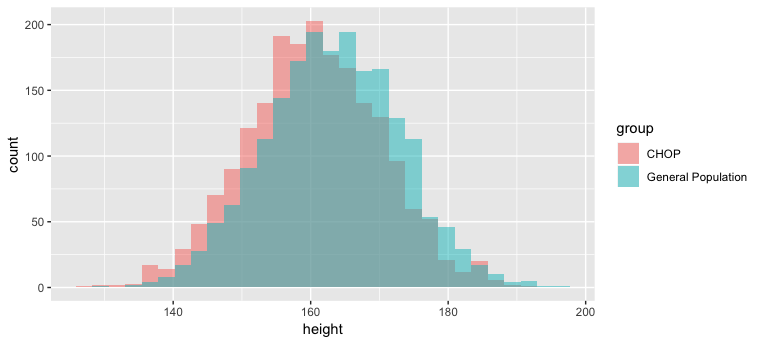

Choosing the correct hypothesis test depends on attributes such as data type and number of groups. Because they’re using continuous data and comparing two means, the researchers use a 2-sample t-test .

Here are the results.

The treatment group’s mean is 58.70, compared to the control group’s mean of 48.12. The mean difference is 10.67 points. Use the test’s p-value and significance level to determine whether this difference is likely a product of random fluctuation in the sample or a genuine population effect.

Because the p-value (0.000) is less than the standard significance level of 0.05, the results are statistically significant, and we can reject the null hypothesis. The sample data provides sufficient evidence to conclude that the new program’s effect exists in the population.

Limitations

Hypothesis testing improves your effectiveness in making data-driven decisions. However, it is not 100% accurate because random samples occasionally produce fluky results. Hypothesis tests have two types of errors, both relating to drawing incorrect conclusions.

- Type I error: The test rejects a true null hypothesis—a false positive.

- Type II error: The test fails to reject a false null hypothesis—a false negative.

Learn more about Type I and Type II Errors .

Our exploration of hypothesis testing using a practical example of an educational program reveals its powerful ability to guide decisions based on statistical evidence. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or professional, understanding and applying these procedures can open new doors to discovering insights and making informed decisions. Let this tool empower your analytical endeavors as you navigate through the vast seas of data.

Learn more about the Hypothesis Tests for Various Data Types .

Share this:

Reader Interactions

June 10, 2024 at 10:51 am

Thank you, Jim, for another helpful article; timely too since I have started reading your new book on hypothesis testing and, now that we are at the end of the school year, my district is asking me to perform a number of evaluations on instructional programs. This is where my question/concern comes in. You mention that hypothesis testing is all about testing samples. However, I use all the students in my district when I make these comparisons. Since I am using the entire “population” in my evaluations (I don’t select a sample of third grade students, for example, but I use all 700 third graders), am I somehow misusing the tests? Or can I rest assured that my district’s student population is only a sample of the universal population of students?

June 10, 2024 at 1:50 pm

I hope you are finding the book helpful!

Yes, the purpose of hypothesis testing is to infer the properties of a population while accounting for random sampling error.

In your case, it comes down to how you want to use the results. Who do you want the results to apply to?

If you’re summarizing the sample, looking for trends and patterns, or evaluating those students and don’t plan to apply those results to other students, you don’t need hypothesis testing because there is no sampling error. They are the population and you can just use descriptive statistics. In this case, you’d only need to focus on the practical significance of the effect sizes.

On the other hand, if you want to apply the results from this group to other students, you’ll need hypothesis testing. However, there is the complicating issue of what population your sample of students represent. I’m sure your district has its own unique characteristics, demographics, etc. Your district’s students probably don’t adequately represent a universal population. At the very least, you’d need to recognize any special attributes of your district and how they could bias the results when trying to apply them outside the district. Or they might apply to similar districts in your region.

However, I’d imagine your 3rd graders probably adequately represent future classes of 3rd graders in your district. You need to be alert to changing demographics. At least in the short run I’d imagine they’d be representative of future classes.

Think about how these results will be used. Do they just apply to the students you measured? Then you don’t need hypothesis tests. However, if the results are being used to infer things about other students outside of the sample, you’ll need hypothesis testing along with considering how well your students represent the other students and how they differ.

I hope that helps!

June 10, 2024 at 3:21 pm

Thank you so much, Jim, for the suggestions in terms of what I need to think about and consider! You are always so clear in your explanations!!!!

June 10, 2024 at 3:22 pm

You’re very welcome! Best of luck with your evaluations!

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.1: Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10211

- Kyle Siegrist

- University of Alabama in Huntsville via Random Services

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Basic Theory

Preliminaries.

As usual, our starting point is a random experiment with an underlying sample space and a probability measure \(\P\). In the basic statistical model, we have an observable random variable \(\bs{X}\) taking values in a set \(S\). In general, \(\bs{X}\) can have quite a complicated structure. For example, if the experiment is to sample \(n\) objects from a population and record various measurements of interest, then \[ \bs{X} = (X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n) \] where \(X_i\) is the vector of measurements for the \(i\)th object. The most important special case occurs when \((X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n)\) are independent and identically distributed. In this case, we have a random sample of size \(n\) from the common distribution.

The purpose of this section is to define and discuss the basic concepts of statistical hypothesis testing . Collectively, these concepts are sometimes referred to as the Neyman-Pearson framework, in honor of Jerzy Neyman and Egon Pearson, who first formalized them.

A statistical hypothesis is a statement about the distribution of \(\bs{X}\). Equivalently, a statistical hypothesis specifies a set of possible distributions of \(\bs{X}\): the set of distributions for which the statement is true. A hypothesis that specifies a single distribution for \(\bs{X}\) is called simple ; a hypothesis that specifies more than one distribution for \(\bs{X}\) is called composite .

In hypothesis testing , the goal is to see if there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject a presumed null hypothesis in favor of a conjectured alternative hypothesis . The null hypothesis is usually denoted \(H_0\) while the alternative hypothesis is usually denoted \(H_1\).

An hypothesis test is a statistical decision ; the conclusion will either be to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative, or to fail to reject the null hypothesis. The decision that we make must, of course, be based on the observed value \(\bs{x}\) of the data vector \(\bs{X}\). Thus, we will find an appropriate subset \(R\) of the sample space \(S\) and reject \(H_0\) if and only if \(\bs{x} \in R\). The set \(R\) is known as the rejection region or the critical region . Note the asymmetry between the null and alternative hypotheses. This asymmetry is due to the fact that we assume the null hypothesis, in a sense, and then see if there is sufficient evidence in \(\bs{x}\) to overturn this assumption in favor of the alternative.

An hypothesis test is a statistical analogy to proof by contradiction, in a sense. Suppose for a moment that \(H_1\) is a statement in a mathematical theory and that \(H_0\) is its negation. One way that we can prove \(H_1\) is to assume \(H_0\) and work our way logically to a contradiction. In an hypothesis test, we don't prove anything of course, but there are similarities. We assume \(H_0\) and then see if the data \(\bs{x}\) are sufficiently at odds with that assumption that we feel justified in rejecting \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_1\).

Often, the critical region is defined in terms of a statistic \(w(\bs{X})\), known as a test statistic , where \(w\) is a function from \(S\) into another set \(T\). We find an appropriate rejection region \(R_T \subseteq T\) and reject \(H_0\) when the observed value \(w(\bs{x}) \in R_T\). Thus, the rejection region in \(S\) is then \(R = w^{-1}(R_T) = \left\{\bs{x} \in S: w(\bs{x}) \in R_T\right\}\). As usual, the use of a statistic often allows significant data reduction when the dimension of the test statistic is much smaller than the dimension of the data vector.

The ultimate decision may be correct or may be in error. There are two types of errors, depending on which of the hypotheses is actually true.

Types of errors:

- A type 1 error is rejecting the null hypothesis \(H_0\) when \(H_0\) is true.

- A type 2 error is failing to reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\) when the alternative hypothesis \(H_1\) is true.

Similarly, there are two ways to make a correct decision: we could reject \(H_0\) when \(H_1\) is true or we could fail to reject \(H_0\) when \(H_0\) is true. The possibilities are summarized in the following table:

| State | Decision | Fail to reject \(H_0\) | Reject \(H_0\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(H_0\) True | Correct | Type 1 error |

| \(H_1\) True | Type 2 error | Correct |

Of course, when we observe \(\bs{X} = \bs{x}\) and make our decision, either we will have made the correct decision or we will have committed an error, and usually we will never know which of these events has occurred. Prior to gathering the data, however, we can consider the probabilities of the various errors.

If \(H_0\) is true (that is, the distribution of \(\bs{X}\) is specified by \(H_0\)), then \(\P(\bs{X} \in R)\) is the probability of a type 1 error for this distribution. If \(H_0\) is composite, then \(H_0\) specifies a variety of different distributions for \(\bs{X}\) and thus there is a set of type 1 error probabilities.

The maximum probability of a type 1 error, over the set of distributions specified by \( H_0 \), is the significance level of the test or the size of the critical region.

The significance level is often denoted by \(\alpha\). Usually, the rejection region is constructed so that the significance level is a prescribed, small value (typically 0.1, 0.05, 0.01).

If \(H_1\) is true (that is, the distribution of \(\bs{X}\) is specified by \(H_1\)), then \(\P(\bs{X} \notin R)\) is the probability of a type 2 error for this distribution. Again, if \(H_1\) is composite then \(H_1\) specifies a variety of different distributions for \(\bs{X}\), and thus there will be a set of type 2 error probabilities. Generally, there is a tradeoff between the type 1 and type 2 error probabilities. If we reduce the probability of a type 1 error, by making the rejection region \(R\) smaller, we necessarily increase the probability of a type 2 error because the complementary region \(S \setminus R\) is larger.

The extreme cases can give us some insight. First consider the decision rule in which we never reject \(H_0\), regardless of the evidence \(\bs{x}\). This corresponds to the rejection region \(R = \emptyset\). A type 1 error is impossible, so the significance level is 0. On the other hand, the probability of a type 2 error is 1 for any distribution defined by \(H_1\). At the other extreme, consider the decision rule in which we always rejects \(H_0\) regardless of the evidence \(\bs{x}\). This corresponds to the rejection region \(R = S\). A type 2 error is impossible, but now the probability of a type 1 error is 1 for any distribution defined by \(H_0\). In between these two worthless tests are meaningful tests that take the evidence \(\bs{x}\) into account.

If \(H_1\) is true, so that the distribution of \(\bs{X}\) is specified by \(H_1\), then \(\P(\bs{X} \in R)\), the probability of rejecting \(H_0\) is the power of the test for that distribution.

Thus the power of the test for a distribution specified by \( H_1 \) is the probability of making the correct decision.

Suppose that we have two tests, corresponding to rejection regions \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), respectively, each having significance level \(\alpha\). The test with region \(R_1\) is uniformly more powerful than the test with region \(R_2\) if \[ \P(\bs{X} \in R_1) \ge \P(\bs{X} \in R_2) \text{ for every distribution of } \bs{X} \text{ specified by } H_1 \]

Naturally, in this case, we would prefer the first test. Often, however, two tests will not be uniformly ordered; one test will be more powerful for some distributions specified by \(H_1\) while the other test will be more powerful for other distributions specified by \(H_1\).

If a test has significance level \(\alpha\) and is uniformly more powerful than any other test with significance level \(\alpha\), then the test is said to be a uniformly most powerful test at level \(\alpha\).

Clearly a uniformly most powerful test is the best we can do.

\(P\)-value

In most cases, we have a general procedure that allows us to construct a test (that is, a rejection region \(R_\alpha\)) for any given significance level \(\alpha \in (0, 1)\). Typically, \(R_\alpha\) decreases (in the subset sense) as \(\alpha\) decreases.

The \(P\)-value of the observed value \(\bs{x}\) of \(\bs{X}\), denoted \(P(\bs{x})\), is defined to be the smallest \(\alpha\) for which \(\bs{x} \in R_\alpha\); that is, the smallest significance level for which \(H_0\) is rejected, given \(\bs{X} = \bs{x}\).

Knowing \(P(\bs{x})\) allows us to test \(H_0\) at any significance level for the given data \(\bs{x}\): If \(P(\bs{x}) \le \alpha\) then we would reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\); if \(P(\bs{x}) \gt \alpha\) then we fail to reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\). Note that \(P(\bs{X})\) is a statistic . Informally, \(P(\bs{x})\) can often be thought of as the probability of an outcome as or more extreme than the observed value \(\bs{x}\), where extreme is interpreted relative to the null hypothesis \(H_0\).

Analogy with Justice Systems

There is a helpful analogy between statistical hypothesis testing and the criminal justice system in the US and various other countries. Consider a person charged with a crime. The presumed null hypothesis is that the person is innocent of the crime; the conjectured alternative hypothesis is that the person is guilty of the crime. The test of the hypotheses is a trial with evidence presented by both sides playing the role of the data. After considering the evidence, the jury delivers the decision as either not guilty or guilty . Note that innocent is not a possible verdict of the jury, because it is not the point of the trial to prove the person innocent. Rather, the point of the trial is to see whether there is sufficient evidence to overturn the null hypothesis that the person is innocent in favor of the alternative hypothesis of that the person is guilty. A type 1 error is convicting a person who is innocent; a type 2 error is acquitting a person who is guilty. Generally, a type 1 error is considered the more serious of the two possible errors, so in an attempt to hold the chance of a type 1 error to a very low level, the standard for conviction in serious criminal cases is beyond a reasonable doubt .

Tests of an Unknown Parameter

Hypothesis testing is a very general concept, but an important special class occurs when the distribution of the data variable \(\bs{X}\) depends on a parameter \(\theta\) taking values in a parameter space \(\Theta\). The parameter may be vector-valued, so that \(\bs{\theta} = (\theta_1, \theta_2, \ldots, \theta_n)\) and \(\Theta \subseteq \R^k\) for some \(k \in \N_+\). The hypotheses generally take the form \[ H_0: \theta \in \Theta_0 \text{ versus } H_1: \theta \notin \Theta_0 \] where \(\Theta_0\) is a prescribed subset of the parameter space \(\Theta\). In this setting, the probabilities of making an error or a correct decision depend on the true value of \(\theta\). If \(R\) is the rejection region, then the power function \( Q \) is given by \[ Q(\theta) = \P_\theta(\bs{X} \in R), \quad \theta \in \Theta \] The power function gives a lot of information about the test.

The power function satisfies the following properties:

- \(Q(\theta)\) is the probability of a type 1 error when \(\theta \in \Theta_0\).

- \(\max\left\{Q(\theta): \theta \in \Theta_0\right\}\) is the significance level of the test.

- \(1 - Q(\theta)\) is the probability of a type 2 error when \(\theta \notin \Theta_0\).

- \(Q(\theta)\) is the power of the test when \(\theta \notin \Theta_0\).

If we have two tests, we can compare them by means of their power functions.

Suppose that we have two tests, corresponding to rejection regions \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), respectively, each having significance level \(\alpha\). The test with rejection region \(R_1\) is uniformly more powerful than the test with rejection region \(R_2\) if \( Q_1(\theta) \ge Q_2(\theta)\) for all \( \theta \notin \Theta_0 \).

Most hypothesis tests of an unknown real parameter \(\theta\) fall into three special cases:

Suppose that \( \theta \) is a real parameter and \( \theta_0 \in \Theta \) a specified value. The tests below are respectively the two-sided test , the left-tailed test , and the right-tailed test .

- \(H_0: \theta = \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \ne \theta_0\)

- \(H_0: \theta \ge \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \lt \theta_0\)

- \(H_0: \theta \le \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \gt \theta_0\)

Thus the tests are named after the conjectured alternative. Of course, there may be other unknown parameters besides \(\theta\) (known as nuisance parameters ).

Equivalence Between Hypothesis Test and Confidence Sets

There is an equivalence between hypothesis tests and confidence sets for a parameter \(\theta\).

Suppose that \(C(\bs{x})\) is a \(1 - \alpha\) level confidence set for \(\theta\). The following test has significance level \(\alpha\) for the hypothesis \( H_0: \theta = \theta_0 \) versus \( H_1: \theta \ne \theta_0 \): Reject \(H_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \notin C(\bs{x})\)

By definition, \(\P[\theta \in C(\bs{X})] = 1 - \alpha\). Hence if \(H_0\) is true so that \(\theta = \theta_0\), then the probability of a type 1 error is \(P[\theta \notin C(\bs{X})] = \alpha\).

Equivalently, we fail to reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\) if and only if \(\theta_0\) is in the corresponding \(1 - \alpha\) level confidence set. In particular, this equivalence applies to interval estimates of a real parameter \(\theta\) and the common tests for \(\theta\) given above .

In each case below, the confidence interval has confidence level \(1 - \alpha\) and the test has significance level \(\alpha\).

- Suppose that \(\left[L(\bs{X}, U(\bs{X})\right]\) is a two-sided confidence interval for \(\theta\). Reject \(H_0: \theta = \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \ne \theta_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \lt L(\bs{X})\) or \(\theta_0 \gt U(\bs{X})\).

- Suppose that \(L(\bs{X})\) is a confidence lower bound for \(\theta\). Reject \(H_0: \theta \le \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \gt \theta_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \lt L(\bs{X})\).

- Suppose that \(U(\bs{X})\) is a confidence upper bound for \(\theta\). Reject \(H_0: \theta \ge \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \lt \theta_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \gt U(\bs{X})\).

Pivot Variables and Test Statistics

Recall that confidence sets of an unknown parameter \(\theta\) are often constructed through a pivot variable , that is, a random variable \(W(\bs{X}, \theta)\) that depends on the data vector \(\bs{X}\) and the parameter \(\theta\), but whose distribution does not depend on \(\theta\) and is known. In this case, a natural test statistic for the basic tests given above is \(W(\bs{X}, \theta_0)\).

User Preferences

Content preview.

Arcu felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis:

- Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

- Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate

- Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident

Keyboard Shortcuts

6a.2 - steps for hypothesis tests, the logic of hypothesis testing section .

A hypothesis, in statistics, is a statement about a population parameter, where this statement typically is represented by some specific numerical value. In testing a hypothesis, we use a method where we gather data in an effort to gather evidence about the hypothesis.

How do we decide whether to reject the null hypothesis?

- If the sample data are consistent with the null hypothesis, then we do not reject it.

- If the sample data are inconsistent with the null hypothesis, but consistent with the alternative, then we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the alternative hypothesis is true.

Six Steps for Hypothesis Tests Section

In hypothesis testing, there are certain steps one must follow. Below these are summarized into six such steps to conducting a test of a hypothesis.

- Set up the hypotheses and check conditions : Each hypothesis test includes two hypotheses about the population. One is the null hypothesis, notated as \(H_0 \), which is a statement of a particular parameter value. This hypothesis is assumed to be true until there is evidence to suggest otherwise. The second hypothesis is called the alternative, or research hypothesis, notated as \(H_a \). The alternative hypothesis is a statement of a range of alternative values in which the parameter may fall. One must also check that any conditions (assumptions) needed to run the test have been satisfied e.g. normality of data, independence, and number of success and failure outcomes.

- Decide on the significance level, \(\alpha \): This value is used as a probability cutoff for making decisions about the null hypothesis. This alpha value represents the probability we are willing to place on our test for making an incorrect decision in regards to rejecting the null hypothesis. The most common \(\alpha \) value is 0.05 or 5%. Other popular choices are 0.01 (1%) and 0.1 (10%).

- Calculate the test statistic: Gather sample data and calculate a test statistic where the sample statistic is compared to the parameter value. The test statistic is calculated under the assumption the null hypothesis is true and incorporates a measure of standard error and assumptions (conditions) related to the sampling distribution.

- Calculate probability value (p-value), or find the rejection region: A p-value is found by using the test statistic to calculate the probability of the sample data producing such a test statistic or one more extreme. The rejection region is found by using alpha to find a critical value; the rejection region is the area that is more extreme than the critical value. We discuss the p-value and rejection region in more detail in the next section.

- Make a decision about the null hypothesis: In this step, we decide to either reject the null hypothesis or decide to fail to reject the null hypothesis. Notice we do not make a decision where we will accept the null hypothesis.

- State an overall conclusion : Once we have found the p-value or rejection region, and made a statistical decision about the null hypothesis (i.e. we will reject the null or fail to reject the null), we then want to summarize our results into an overall conclusion for our test.

We will follow these six steps for the remainder of this Lesson. In the future Lessons, the steps will be followed but may not be explained explicitly.

Step 1 is a very important step to set up correctly. If your hypotheses are incorrect, your conclusion will be incorrect. In this next section, we practice with Step 1 for the one sample situations.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 13: Inferential Statistics

Understanding Null Hypothesis Testing

Learning Objectives

- Explain the purpose of null hypothesis testing, including the role of sampling error.

- Describe the basic logic of null hypothesis testing.

- Describe the role of relationship strength and sample size in determining statistical significance and make reasonable judgments about statistical significance based on these two factors.

The Purpose of Null Hypothesis Testing

As we have seen, psychological research typically involves measuring one or more variables for a sample and computing descriptive statistics for that sample. In general, however, the researcher’s goal is not to draw conclusions about that sample but to draw conclusions about the population that the sample was selected from. Thus researchers must use sample statistics to draw conclusions about the corresponding values in the population. These corresponding values in the population are called parameters . Imagine, for example, that a researcher measures the number of depressive symptoms exhibited by each of 50 clinically depressed adults and computes the mean number of symptoms. The researcher probably wants to use this sample statistic (the mean number of symptoms for the sample) to draw conclusions about the corresponding population parameter (the mean number of symptoms for clinically depressed adults).

Unfortunately, sample statistics are not perfect estimates of their corresponding population parameters. This is because there is a certain amount of random variability in any statistic from sample to sample. The mean number of depressive symptoms might be 8.73 in one sample of clinically depressed adults, 6.45 in a second sample, and 9.44 in a third—even though these samples are selected randomly from the same population. Similarly, the correlation (Pearson’s r ) between two variables might be +.24 in one sample, −.04 in a second sample, and +.15 in a third—again, even though these samples are selected randomly from the same population. This random variability in a statistic from sample to sample is called sampling error . (Note that the term error here refers to random variability and does not imply that anyone has made a mistake. No one “commits a sampling error.”)

One implication of this is that when there is a statistical relationship in a sample, it is not always clear that there is a statistical relationship in the population. A small difference between two group means in a sample might indicate that there is a small difference between the two group means in the population. But it could also be that there is no difference between the means in the population and that the difference in the sample is just a matter of sampling error. Similarly, a Pearson’s r value of −.29 in a sample might mean that there is a negative relationship in the population. But it could also be that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample is just a matter of sampling error.

In fact, any statistical relationship in a sample can be interpreted in two ways:

- There is a relationship in the population, and the relationship in the sample reflects this.

- There is no relationship in the population, and the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error.

The purpose of null hypothesis testing is simply to help researchers decide between these two interpretations.

The Logic of Null Hypothesis Testing

Null hypothesis testing is a formal approach to deciding between two interpretations of a statistical relationship in a sample. One interpretation is called the null hypothesis (often symbolized H 0 and read as “H-naught”). This is the idea that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error. Informally, the null hypothesis is that the sample relationship “occurred by chance.” The other interpretation is called the alternative hypothesis (often symbolized as H 1 ). This is the idea that there is a relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects this relationship in the population.

Again, every statistical relationship in a sample can be interpreted in either of these two ways: It might have occurred by chance, or it might reflect a relationship in the population. So researchers need a way to decide between them. Although there are many specific null hypothesis testing techniques, they are all based on the same general logic. The steps are as follows:

- Assume for the moment that the null hypothesis is true. There is no relationship between the variables in the population.

- Determine how likely the sample relationship would be if the null hypothesis were true.

- If the sample relationship would be extremely unlikely, then reject the null hypothesis in favour of the alternative hypothesis. If it would not be extremely unlikely, then retain the null hypothesis .

Following this logic, we can begin to understand why Mehl and his colleagues concluded that there is no difference in talkativeness between women and men in the population. In essence, they asked the following question: “If there were no difference in the population, how likely is it that we would find a small difference of d = 0.06 in our sample?” Their answer to this question was that this sample relationship would be fairly likely if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, they retained the null hypothesis—concluding that there is no evidence of a sex difference in the population. We can also see why Kanner and his colleagues concluded that there is a correlation between hassles and symptoms in the population. They asked, “If the null hypothesis were true, how likely is it that we would find a strong correlation of +.60 in our sample?” Their answer to this question was that this sample relationship would be fairly unlikely if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, they rejected the null hypothesis in favour of the alternative hypothesis—concluding that there is a positive correlation between these variables in the population.

A crucial step in null hypothesis testing is finding the likelihood of the sample result if the null hypothesis were true. This probability is called the p value . A low p value means that the sample result would be unlikely if the null hypothesis were true and leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis. A high p value means that the sample result would be likely if the null hypothesis were true and leads to the retention of the null hypothesis. But how low must the p value be before the sample result is considered unlikely enough to reject the null hypothesis? In null hypothesis testing, this criterion is called α (alpha) and is almost always set to .05. If there is less than a 5% chance of a result as extreme as the sample result if the null hypothesis were true, then the null hypothesis is rejected. When this happens, the result is said to be statistically significant . If there is greater than a 5% chance of a result as extreme as the sample result when the null hypothesis is true, then the null hypothesis is retained. This does not necessarily mean that the researcher accepts the null hypothesis as true—only that there is not currently enough evidence to conclude that it is true. Researchers often use the expression “fail to reject the null hypothesis” rather than “retain the null hypothesis,” but they never use the expression “accept the null hypothesis.”

The Misunderstood p Value

The p value is one of the most misunderstood quantities in psychological research (Cohen, 1994) [1] . Even professional researchers misinterpret it, and it is not unusual for such misinterpretations to appear in statistics textbooks!

The most common misinterpretation is that the p value is the probability that the null hypothesis is true—that the sample result occurred by chance. For example, a misguided researcher might say that because the p value is .02, there is only a 2% chance that the result is due to chance and a 98% chance that it reflects a real relationship in the population. But this is incorrect . The p value is really the probability of a result at least as extreme as the sample result if the null hypothesis were true. So a p value of .02 means that if the null hypothesis were true, a sample result this extreme would occur only 2% of the time.

You can avoid this misunderstanding by remembering that the p value is not the probability that any particular hypothesis is true or false. Instead, it is the probability of obtaining the sample result if the null hypothesis were true.

Role of Sample Size and Relationship Strength

Recall that null hypothesis testing involves answering the question, “If the null hypothesis were true, what is the probability of a sample result as extreme as this one?” In other words, “What is the p value?” It can be helpful to see that the answer to this question depends on just two considerations: the strength of the relationship and the size of the sample. Specifically, the stronger the sample relationship and the larger the sample, the less likely the result would be if the null hypothesis were true. That is, the lower the p value. This should make sense. Imagine a study in which a sample of 500 women is compared with a sample of 500 men in terms of some psychological characteristic, and Cohen’s d is a strong 0.50. If there were really no sex difference in the population, then a result this strong based on such a large sample should seem highly unlikely. Now imagine a similar study in which a sample of three women is compared with a sample of three men, and Cohen’s d is a weak 0.10. If there were no sex difference in the population, then a relationship this weak based on such a small sample should seem likely. And this is precisely why the null hypothesis would be rejected in the first example and retained in the second.

Of course, sometimes the result can be weak and the sample large, or the result can be strong and the sample small. In these cases, the two considerations trade off against each other so that a weak result can be statistically significant if the sample is large enough and a strong relationship can be statistically significant even if the sample is small. Table 13.1 shows roughly how relationship strength and sample size combine to determine whether a sample result is statistically significant. The columns of the table represent the three levels of relationship strength: weak, medium, and strong. The rows represent four sample sizes that can be considered small, medium, large, and extra large in the context of psychological research. Thus each cell in the table represents a combination of relationship strength and sample size. If a cell contains the word Yes , then this combination would be statistically significant for both Cohen’s d and Pearson’s r . If it contains the word No , then it would not be statistically significant for either. There is one cell where the decision for d and r would be different and another where it might be different depending on some additional considerations, which are discussed in Section 13.2 “Some Basic Null Hypothesis Tests”

| Sample Size | Weak relationship | Medium-strength relationship | Strong relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small ( = 20) | No | No | = Maybe = Yes |

| Medium ( = 50) | No | Yes | Yes |

| Large ( = 100) | = Yes = No | Yes | Yes |

| Extra large ( = 500) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Although Table 13.1 provides only a rough guideline, it shows very clearly that weak relationships based on medium or small samples are never statistically significant and that strong relationships based on medium or larger samples are always statistically significant. If you keep this lesson in mind, you will often know whether a result is statistically significant based on the descriptive statistics alone. It is extremely useful to be able to develop this kind of intuitive judgment. One reason is that it allows you to develop expectations about how your formal null hypothesis tests are going to come out, which in turn allows you to detect problems in your analyses. For example, if your sample relationship is strong and your sample is medium, then you would expect to reject the null hypothesis. If for some reason your formal null hypothesis test indicates otherwise, then you need to double-check your computations and interpretations. A second reason is that the ability to make this kind of intuitive judgment is an indication that you understand the basic logic of this approach in addition to being able to do the computations.

Statistical Significance Versus Practical Significance

Table 13.1 illustrates another extremely important point. A statistically significant result is not necessarily a strong one. Even a very weak result can be statistically significant if it is based on a large enough sample. This is closely related to Janet Shibley Hyde’s argument about sex differences (Hyde, 2007) [2] . The differences between women and men in mathematical problem solving and leadership ability are statistically significant. But the word significant can cause people to interpret these differences as strong and important—perhaps even important enough to influence the college courses they take or even who they vote for. As we have seen, however, these statistically significant differences are actually quite weak—perhaps even “trivial.”

This is why it is important to distinguish between the statistical significance of a result and the practical significance of that result. Practical significance refers to the importance or usefulness of the result in some real-world context. Many sex differences are statistically significant—and may even be interesting for purely scientific reasons—but they are not practically significant. In clinical practice, this same concept is often referred to as “clinical significance.” For example, a study on a new treatment for social phobia might show that it produces a statistically significant positive effect. Yet this effect still might not be strong enough to justify the time, effort, and other costs of putting it into practice—especially if easier and cheaper treatments that work almost as well already exist. Although statistically significant, this result would be said to lack practical or clinical significance.

Key Takeaways

- Null hypothesis testing is a formal approach to deciding whether a statistical relationship in a sample reflects a real relationship in the population or is just due to chance.

- The logic of null hypothesis testing involves assuming that the null hypothesis is true, finding how likely the sample result would be if this assumption were correct, and then making a decision. If the sample result would be unlikely if the null hypothesis were true, then it is rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis. If it would not be unlikely, then the null hypothesis is retained.

- The probability of obtaining the sample result if the null hypothesis were true (the p value) is based on two considerations: relationship strength and sample size. Reasonable judgments about whether a sample relationship is statistically significant can often be made by quickly considering these two factors.

- Statistical significance is not the same as relationship strength or importance. Even weak relationships can be statistically significant if the sample size is large enough. It is important to consider relationship strength and the practical significance of a result in addition to its statistical significance.

- Discussion: Imagine a study showing that people who eat more broccoli tend to be happier. Explain for someone who knows nothing about statistics why the researchers would conduct a null hypothesis test.

- The correlation between two variables is r = −.78 based on a sample size of 137.

- The mean score on a psychological characteristic for women is 25 ( SD = 5) and the mean score for men is 24 ( SD = 5). There were 12 women and 10 men in this study.

- In a memory experiment, the mean number of items recalled by the 40 participants in Condition A was 0.50 standard deviations greater than the mean number recalled by the 40 participants in Condition B.

- In another memory experiment, the mean scores for participants in Condition A and Condition B came out exactly the same!

- A student finds a correlation of r = .04 between the number of units the students in his research methods class are taking and the students’ level of stress.

Long Descriptions

“Null Hypothesis” long description: A comic depicting a man and a woman talking in the foreground. In the background is a child working at a desk. The man says to the woman, “I can’t believe schools are still teaching kids about the null hypothesis. I remember reading a big study that conclusively disproved it years ago.” [Return to “Null Hypothesis”]

“Conditional Risk” long description: A comic depicting two hikers beside a tree during a thunderstorm. A bolt of lightning goes “crack” in the dark sky as thunder booms. One of the hikers says, “Whoa! We should get inside!” The other hiker says, “It’s okay! Lightning only kills about 45 Americans a year, so the chances of dying are only one in 7,000,000. Let’s go on!” The comic’s caption says, “The annual death rate among people who know that statistic is one in six.” [Return to “Conditional Risk”]

Media Attributions

- Null Hypothesis by XKCD CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial)

- Conditional Risk by XKCD CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial)

- Cohen, J. (1994). The world is round: p < .05. American Psychologist, 49 , 997–1003. ↵

- Hyde, J. S. (2007). New directions in the study of gender similarities and differences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16 , 259–263. ↵

Values in a population that correspond to variables measured in a study.

The random variability in a statistic from sample to sample.

A formal approach to deciding between two interpretations of a statistical relationship in a sample.

The idea that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error.

The idea that there is a relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects this relationship in the population.

When the relationship found in the sample would be extremely unlikely, the idea that the relationship occurred “by chance” is rejected.

When the relationship found in the sample is likely to have occurred by chance, the null hypothesis is not rejected.

The probability that, if the null hypothesis were true, the result found in the sample would occur.

How low the p value must be before the sample result is considered unlikely in null hypothesis testing.

When there is less than a 5% chance of a result as extreme as the sample result occurring and the null hypothesis is rejected.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College Statistics

Course: ap®︎/college statistics > unit 10.

- Idea behind hypothesis testing

Examples of null and alternative hypotheses

- Writing null and alternative hypotheses

- P-values and significance tests

- Comparing P-values to different significance levels

- Estimating a P-value from a simulation

- Estimating P-values from simulations

- Using P-values to make conclusions

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

5 Free Tutorials on Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a fundamental technique used in statistics to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample of data to infer that a certain condition is true for the entire population. Whether you are a complete novice looking to get your feet wet or an intermediate learner aiming to expand your statistical skills, the following curated list of tutorials will guide you through various aspects of hypothesis testing. These resources have been selected to cater to different learning preferences and levels of existing knowledge.

1. Class Central: Free Course on Hypothesis Testing

Description: This free online course simplifies hypothesis testing into manageable lessons, ideal for beginners. It covers basic concepts such as Type 1 and Type 2 errors and statistical power, providing a solid foundation without overwhelming the learner with technical details. Interactive elements help engage users and solidify understanding through practice. This course is perfect for those who are just starting out in statistics and looking to understand the core principles of hypothesis testing.

Level: Beginner

Resource: Class Central Course

2. Statistics How To: Hypothesis Testing Guide

Description: This guide serves as an excellent starting point for anyone new to hypothesis testing. It walks readers through different types of tests, explaining when each should be used and why. The explanations are clear and concise, making complex topics accessible to beginners. Practical examples are used to demonstrate the applications of hypothesis testing in real-world scenarios.

Resource: Statistics How To Guide

3. DATAtab Hypothesis Testing Tutorial

Description: DATAtab’s tutorial on hypothesis testing offers a detailed exploration of the subject, suitable for those who already have some background in statistics. It explains various statistical tests and the scenarios in which they are applied, complemented by illustrative examples to aid understanding. This tutorial also covers how to interpret the results of these tests, making it a comprehensive resource for students and professionals alike. It’s perfect for those looking to enhance their knowledge and apply hypothesis testing in more complex studies.

Level: Intermediate

Resource: DATAtab Tutorial

4. MarinStatsLectures on YouTube

Description: MarinStatsLectures provides a comprehensive video series on hypothesis testing that covers the formulation of null and alternative hypotheses, understanding p-values, and the concept of statistical significance. The presenter uses clear, visual aids to help demystify the complex statistical concepts involved in testing hypotheses. Each video is designed to build on the previous one, making it an excellent series for those looking to deepen their understanding progressively. This resource is particularly beneficial for visual learners who appreciate step-by-step explanations.

Resource : YouTube: MarinStats Hypothesis Testing Series

5. Hypothesis Testing Tutorial (PDF)

Description: This PDF tutorial offers an in-depth look at hypothesis testing, perfect for advanced learners who prefer detailed, text-based learning materials. It revisits fundamental concepts like p-values and introduces more complex tests such as chi-squared and t-tests. The tutorial is structured to allow readers to delve deeply into each topic, with ample examples to illustrate complex concepts. This resource is ideal for students or professionals looking to deepen their statistical knowledge through a rigorous academic approach.

Resource: PDF Tutorial

As you explore these tutorials, you will gain a clearer understanding of hypothesis testing, which is essential for analyzing data and making informed decisions in various fields. Each resource is tailored to build your competence and confidence in applying hypothesis testing techniques to your own projects. Equip yourself with these skills today, and enhance your analytical capabilities for future challenges.

Header image by gstudioimagen on Freepik .

Featured Posts

An adept professional in the realms of Data Science, Machine Learning, and Artificial Intelligence, operating across various educational and content creation platforms.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Statology Community

Sign up to receive Statology's exclusive study resource: 100 practice problems with step-by-step solutions. Plus, get our latest insights, tutorials, and data analysis tips straight to your inbox!

By subscribing you accept Statology's Privacy Policy.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Choosing the Right Statistical Test | Types & Examples

Choosing the Right Statistical Test | Types & Examples

Published on January 28, 2020 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Statistical tests are used in hypothesis testing . They can be used to:

- determine whether a predictor variable has a statistically significant relationship with an outcome variable.

- estimate the difference between two or more groups.

Statistical tests assume a null hypothesis of no relationship or no difference between groups. Then they determine whether the observed data fall outside of the range of values predicted by the null hypothesis.

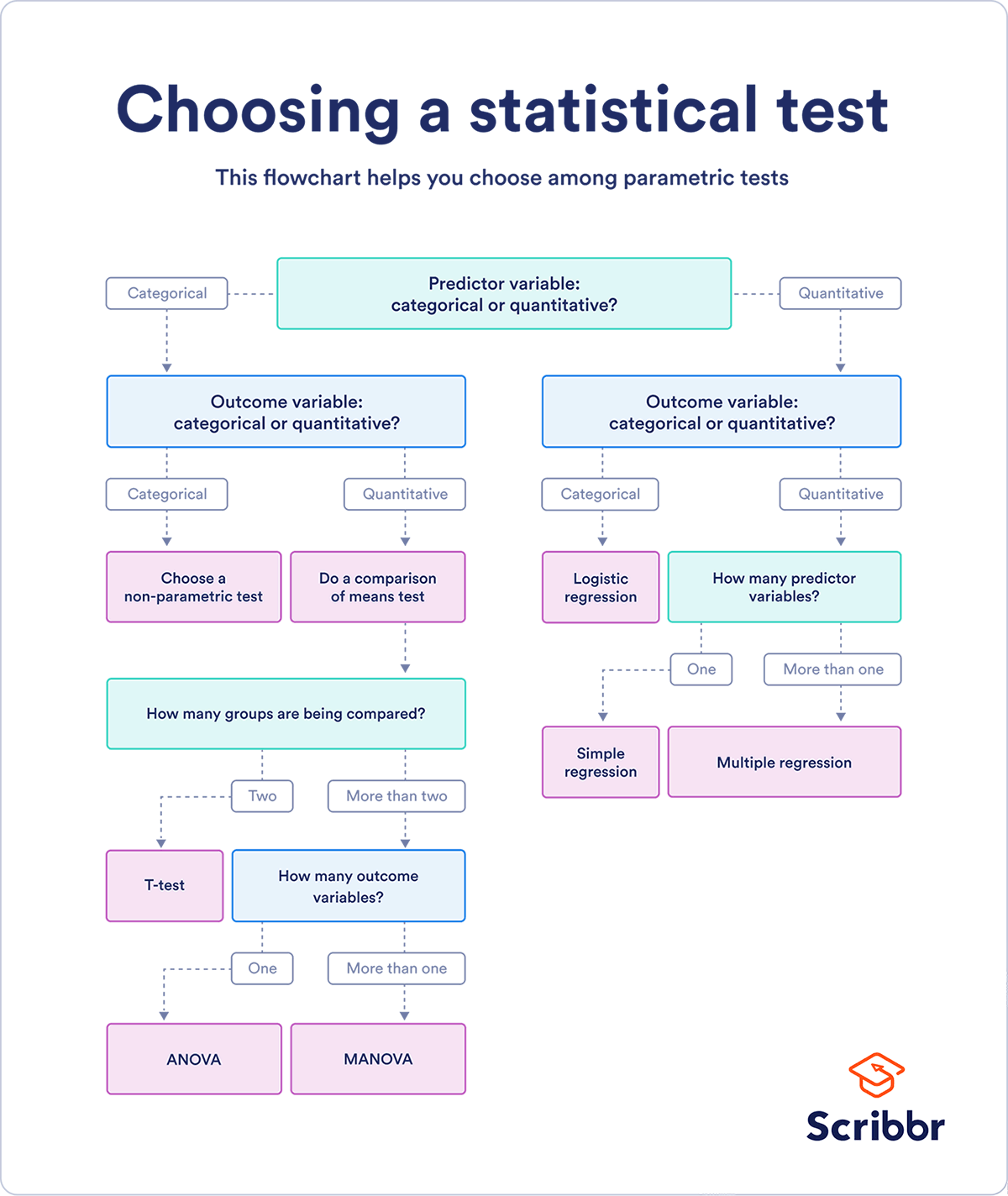

If you already know what types of variables you’re dealing with, you can use the flowchart to choose the right statistical test for your data.

Statistical tests flowchart

Table of contents

What does a statistical test do, when to perform a statistical test, choosing a parametric test: regression, comparison, or correlation, choosing a nonparametric test, flowchart: choosing a statistical test, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about statistical tests.

Statistical tests work by calculating a test statistic – a number that describes how much the relationship between variables in your test differs from the null hypothesis of no relationship.

It then calculates a p value (probability value). The p -value estimates how likely it is that you would see the difference described by the test statistic if the null hypothesis of no relationship were true.

If the value of the test statistic is more extreme than the statistic calculated from the null hypothesis, then you can infer a statistically significant relationship between the predictor and outcome variables.

If the value of the test statistic is less extreme than the one calculated from the null hypothesis, then you can infer no statistically significant relationship between the predictor and outcome variables.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You can perform statistical tests on data that have been collected in a statistically valid manner – either through an experiment , or through observations made using probability sampling methods .

For a statistical test to be valid , your sample size needs to be large enough to approximate the true distribution of the population being studied.

To determine which statistical test to use, you need to know:

- whether your data meets certain assumptions.

- the types of variables that you’re dealing with.

Statistical assumptions

Statistical tests make some common assumptions about the data they are testing:

- Independence of observations (a.k.a. no autocorrelation): The observations/variables you include in your test are not related (for example, multiple measurements of a single test subject are not independent, while measurements of multiple different test subjects are independent).

- Homogeneity of variance : the variance within each group being compared is similar among all groups. If one group has much more variation than others, it will limit the test’s effectiveness.

- Normality of data : the data follows a normal distribution (a.k.a. a bell curve). This assumption applies only to quantitative data .

If your data do not meet the assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variance, you may be able to perform a nonparametric statistical test , which allows you to make comparisons without any assumptions about the data distribution.

If your data do not meet the assumption of independence of observations, you may be able to use a test that accounts for structure in your data (repeated-measures tests or tests that include blocking variables).

Types of variables

The types of variables you have usually determine what type of statistical test you can use.

Quantitative variables represent amounts of things (e.g. the number of trees in a forest). Types of quantitative variables include:

- Continuous (aka ratio variables): represent measures and can usually be divided into units smaller than one (e.g. 0.75 grams).

- Discrete (aka integer variables): represent counts and usually can’t be divided into units smaller than one (e.g. 1 tree).

Categorical variables represent groupings of things (e.g. the different tree species in a forest). Types of categorical variables include:

- Ordinal : represent data with an order (e.g. rankings).

- Nominal : represent group names (e.g. brands or species names).

- Binary : represent data with a yes/no or 1/0 outcome (e.g. win or lose).

Choose the test that fits the types of predictor and outcome variables you have collected (if you are doing an experiment , these are the independent and dependent variables ). Consult the tables below to see which test best matches your variables.

Parametric tests usually have stricter requirements than nonparametric tests, and are able to make stronger inferences from the data. They can only be conducted with data that adheres to the common assumptions of statistical tests.

The most common types of parametric test include regression tests, comparison tests, and correlation tests.

Regression tests

Regression tests look for cause-and-effect relationships . They can be used to estimate the effect of one or more continuous variables on another variable.

| Predictor variable | Outcome variable | Research question example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is the effect of income on longevity? | |||

| What is the effect of income and minutes of exercise per day on longevity? | |||

| Logistic regression | What is the effect of drug dosage on the survival of a test subject? |

Comparison tests

Comparison tests look for differences among group means . They can be used to test the effect of a categorical variable on the mean value of some other characteristic.

T-tests are used when comparing the means of precisely two groups (e.g., the average heights of men and women). ANOVA and MANOVA tests are used when comparing the means of more than two groups (e.g., the average heights of children, teenagers, and adults).

| Predictor variable | Outcome variable | Research question example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paired t-test | What is the effect of two different test prep programs on the average exam scores for students from the same class? | ||

| Independent t-test | What is the difference in average exam scores for students from two different schools? | ||

| ANOVA | What is the difference in average pain levels among post-surgical patients given three different painkillers? | ||

| MANOVA | What is the effect of flower species on petal length, petal width, and stem length? |

Correlation tests

Correlation tests check whether variables are related without hypothesizing a cause-and-effect relationship.

These can be used to test whether two variables you want to use in (for example) a multiple regression test are autocorrelated.

| Variables | Research question example | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s | How are latitude and temperature related? |

Non-parametric tests don’t make as many assumptions about the data, and are useful when one or more of the common statistical assumptions are violated. However, the inferences they make aren’t as strong as with parametric tests.

| Predictor variable | Outcome variable | Use in place of… | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s | |||

| Pearson’s | |||

| Sign test | One-sample -test | ||

| Kruskal–Wallis | ANOVA | ||

| ANOSIM | MANOVA | ||

| Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test | Independent t-test | ||

| Wilcoxon Signed-rank test | Paired t-test | ||

This flowchart helps you choose among parametric tests. For nonparametric alternatives, check the table above.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

- Null hypothesis

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

Statistical tests commonly assume that:

- the data are normally distributed

- the groups that are being compared have similar variance

- the data are independent

If your data does not meet these assumptions you might still be able to use a nonparametric statistical test , which have fewer requirements but also make weaker inferences.

A test statistic is a number calculated by a statistical test . It describes how far your observed data is from the null hypothesis of no relationship between variables or no difference among sample groups.

The test statistic tells you how different two or more groups are from the overall population mean , or how different a linear slope is from the slope predicted by a null hypothesis . Different test statistics are used in different statistical tests.

Statistical significance is a term used by researchers to state that it is unlikely their observations could have occurred under the null hypothesis of a statistical test . Significance is usually denoted by a p -value , or probability value.

Statistical significance is arbitrary – it depends on the threshold, or alpha value, chosen by the researcher. The most common threshold is p < 0.05, which means that the data is likely to occur less than 5% of the time under the null hypothesis .

When the p -value falls below the chosen alpha value, then we say the result of the test is statistically significant.

Quantitative variables are any variables where the data represent amounts (e.g. height, weight, or age).

Categorical variables are any variables where the data represent groups. This includes rankings (e.g. finishing places in a race), classifications (e.g. brands of cereal), and binary outcomes (e.g. coin flips).

You need to know what type of variables you are working with to choose the right statistical test for your data and interpret your results .

Discrete and continuous variables are two types of quantitative variables :

- Discrete variables represent counts (e.g. the number of objects in a collection).

- Continuous variables represent measurable amounts (e.g. water volume or weight).

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bevans, R. (2023, June 22). Choosing the Right Statistical Test | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/statistical-tests/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

Other students also liked, hypothesis testing | a step-by-step guide with easy examples, test statistics | definition, interpretation, and examples, normal distribution | examples, formulas, & uses, what is your plagiarism score.

13.1 Understanding Null Hypothesis Testing

Learning objectives.

- Explain the purpose of null hypothesis testing, including the role of sampling error.

- Describe the basic logic of null hypothesis testing.

- Describe the role of relationship strength and sample size in determining statistical significance and make reasonable judgments about statistical significance based on these two factors.

The Purpose of Null Hypothesis Testing

As we have seen, psychological research typically involves measuring one or more variables in a sample and computing descriptive statistics for that sample. In general, however, the researcher’s goal is not to draw conclusions about that sample but to draw conclusions about the population that the sample was selected from. Thus researchers must use sample statistics to draw conclusions about the corresponding values in the population. These corresponding values in the population are called parameters . Imagine, for example, that a researcher measures the number of depressive symptoms exhibited by each of 50 adults with clinical depression and computes the mean number of symptoms. The researcher probably wants to use this sample statistic (the mean number of symptoms for the sample) to draw conclusions about the corresponding population parameter (the mean number of symptoms for adults with clinical depression).

Unfortunately, sample statistics are not perfect estimates of their corresponding population parameters. This is because there is a certain amount of random variability in any statistic from sample to sample. The mean number of depressive symptoms might be 8.73 in one sample of adults with clinical depression, 6.45 in a second sample, and 9.44 in a third—even though these samples are selected randomly from the same population. Similarly, the correlation (Pearson’s r ) between two variables might be +.24 in one sample, −.04 in a second sample, and +.15 in a third—again, even though these samples are selected randomly from the same population. This random variability in a statistic from sample to sample is called sampling error . (Note that the term error here refers to random variability and does not imply that anyone has made a mistake. No one “commits a sampling error.”)

One implication of this is that when there is a statistical relationship in a sample, it is not always clear that there is a statistical relationship in the population. A small difference between two group means in a sample might indicate that there is a small difference between the two group means in the population. But it could also be that there is no difference between the means in the population and that the difference in the sample is just a matter of sampling error. Similarly, a Pearson’s r value of −.29 in a sample might mean that there is a negative relationship in the population. But it could also be that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample is just a matter of sampling error.

In fact, any statistical relationship in a sample can be interpreted in two ways:

- There is a relationship in the population, and the relationship in the sample reflects this.

- There is no relationship in the population, and the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error.

The purpose of null hypothesis testing is simply to help researchers decide between these two interpretations.

The Logic of Null Hypothesis Testing

Null hypothesis testing is a formal approach to deciding between two interpretations of a statistical relationship in a sample. One interpretation is called the null hypothesis (often symbolized H 0 and read as “H-naught”). This is the idea that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error. Informally, the null hypothesis is that the sample relationship “occurred by chance.” The other interpretation is called the alternative hypothesis (often symbolized as H 1 ). This is the idea that there is a relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects this relationship in the population.

Again, every statistical relationship in a sample can be interpreted in either of these two ways: It might have occurred by chance, or it might reflect a relationship in the population. So researchers need a way to decide between them. Although there are many specific null hypothesis testing techniques, they are all based on the same general logic. The steps are as follows:

- Assume for the moment that the null hypothesis is true. There is no relationship between the variables in the population.

- Determine how likely the sample relationship would be if the null hypothesis were true.

- If the sample relationship would be extremely unlikely, then reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. If it would not be extremely unlikely, then retain the null hypothesis .

Following this logic, we can begin to understand why Mehl and his colleagues concluded that there is no difference in talkativeness between women and men in the population. In essence, they asked the following question: “If there were no difference in the population, how likely is it that we would find a small difference of d = 0.06 in our sample?” Their answer to this question was that this sample relationship would be fairly likely if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, they retained the null hypothesis—concluding that there is no evidence of a sex difference in the population. We can also see why Kanner and his colleagues concluded that there is a correlation between hassles and symptoms in the population. They asked, “If the null hypothesis were true, how likely is it that we would find a strong correlation of +.60 in our sample?” Their answer to this question was that this sample relationship would be fairly unlikely if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, they rejected the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis—concluding that there is a positive correlation between these variables in the population.