How to teach research skills to high school students: 12 tips

by mindroar | Oct 10, 2021 | blog | 0 comments

Teachers often find it difficult to decide how to teach research skills to high school students. You probably feel students should know how to do research by high school. But often students’ skills are lacking in one or more areas.

Today we’re not going to give you research skills lesson plans for high school. But we will give you 12 tips for how to teach research skills to high school students. Bonus, the tips will make it quick, fun, and easy.

One of my favorite ways of teaching research skills to high school students is to use the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series.

The videos are free and short (between ten and fifteen minutes each). They cover information such as evaluating the trustworthiness of sources, using Wikipedia, lateral reading, and understanding how the source medium can affect the message.

Another thing I like to integrate into my lessons are the Crash Course Study Skills videos . Again, they’re free and short. Plus they are an easy way to refresh study skills such as:

- note-taking

- writing papers

- editing papers

- getting organized

- and studying for tests and exams.

If you’re ready to get started, we’ll give you links to great resources that you can integrate into your lessons. Because often students just need a refresh on a particular skill and not a whole semester-long course.

1. Why learn digital research skills?

Tip number one of how to teach research skills to high school students. Address the dreaded ‘why?’ questions upfront. You know the questions: Why do we have to do this? When am I ever going to use this?

If your students understand why they need good research skills and know that you will show them specific strategies to improve their skills, they are far more likely to buy into learning about how to research effectively.

An easy way to answer this question is that students spend so much time online. Some people spend almost an entire day online each week.

It’s amazing to have such easy access to information, unlike the pre-internet days. But there is far more misinformation and disinformation online.

A webpage, Facebook post, Instagram post, YouTube video, infographic, meme, gif, TikTok video (etc etc) can be created by just about anyone with a phone. And it’s easy to create them in a way that looks professional and legitimate.

This can make it hard for people to know what is real, true, evidence-based information and what is not.

The first Crash Course Navigating Digital Information video gets into the nitty-gritty of why we should learn strategies for evaluating the information we find (online or otherwise!).

An easy way to answer the ‘why’ questions your high schoolers will ask, the video is an excellent resource.

2. Teaching your students to fact check

Tip number two for teaching research skills to high school students is to teach your students concrete strategies for how to check facts.

It’s surprising how many students will hand in work with blatant factual errors. Errors they could have avoided had they done a quick fact check.

An easy way to broach this research skill in high school is to watch the second video in the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series. It explains what fact-checking is, why people should do it, and how to make it a habit.

You can explain to your students that they’ll write better papers if they learn to fact-check. But they’ll also make better decisions if they make fact-checking a habit.

The video looks at why people are more likely to believe mis- or disinformation online. And it shows students a series of questions they can use to identify mis- or disinformation.

The video also discusses why it’s important to find a few generally reliable sources of information and to use those as a way to fact-check other online sources.

3. Teaching your students how and why to read laterally

This ties in with tip number 2 – teach concrete research strategies – but it is more specific. Fact-checking tends to be checking what claim sources are making, who is making the claim, and corroborating the claim with other sources.

But lateral reading is another concrete research skills strategy that you can teach to students. This skill helps students spot inaccurate information quickly and avoid wasting valuable research time.

One of the best (and easiest!) research skills for high school students to learn is how to read laterally. And teachers can demonstrate it so, so easily. As John Green says in the third Crash Course Navigating Digital Information video , just open another tab!

The video also shows students good websites to use to check hoaxes and controversial information.

Importantly, John Green also explains that students need a “toolbox” of strategies to assess sources of information. There’s not one magic source of information that is 100% accurate.

4. Teaching your students how to evaluate trustworthiness

Deciding who to trust online can be difficult even for those of us with lots of experience navigating online. And it is made even more difficult by how easy it now is to create a professional-looking websites.

This video shows students what to look for when evaluating trustworthiness. It also explains how to take bias, opinion, and political orientations into account when using information sources.

The video explains how reputable information sources gather reliable information (versus disreputable sources). And shows how reputable information sources navigate the situation when they discover their information is incorrect or misleading.

Students can apply the research skills from this video to news sources, novel excerpts, scholarly articles, and primary sources. Teaching students to look for bias, political orientation, and opinions within all sources is one of the most valuable research skills for high school students.

5. Teaching your students to use Wikipedia

Now, I know that Wikipedia can be the bane of your teacherly existence when you are reading essays. I know it can make you want to gouge your eyes out with a spoon when you read the same recycled article in thirty different essays. But, teaching students how to use Wikipedia as a jumping-off point is a useful skill.

Wikipedia is no less accurate than other online encyclopedia-type sources. And it often includes hyperlinks and references that students can check or use for further research. Plus it has handy-dandy warnings for inaccurate and contentious information.

Part of how to teach research skills to high school students is teaching them how to use general reference material such as encyclopedias for broad information. And then following up with how to use more detailed information such as primary and secondary sources.

The Crash Course video about Wikipedia is an easy way to show students how to use it more effectively.

6. Teaching your students to evaluate evidence

Another important research skill to teach high school students is how to evaluate evidence. This skill is important, both in their own and in others’ work.

An easy way to do this is the Crash Course video about evaluating evidence video. The short video shows students how to evaluate evidence using authorship, the evidence provided, and the relevance of the evidence.

It also gives examples of ways that evidence can be used to mislead. For example, it shows that simply providing evidence doesn’t mean that the evidence is quality evidence that supports the claim being made.

The video shows examples of evidence that is related to a topic, but irrelevant to the claim. Having an example of irrelevant evidence helps students understand the difference between related but irrelevant evidence and evidence that is relevant to the claim.

Finally, the video gives students questions that they can use to evaluate evidence.

7. Teaching your students to evaluate photos and videos

While the previous video about evidence looked at how to evaluate evidence in general, this video looks specifically at video and photographic evidence.

The video looks at how videos and photos can be manipulated to provide evidence for a claim. It suggests that seeking out the context for photos and videos is especially important as a video or photo is easy to misinterpret. This is especially the case if a misleading caption or surrounding information is provided.

The video also gives tools that students can use to discover hoaxes or fakes. Similarly, it encourages people to look for the origin of the photo or video to find the creator. And to then use that with contextual information to decide whether the photo or video is reliable evidence for a claim.

8. Teaching your students to evaluate data and infographics

Other sources of evidence that students (and adults!) often misinterpret or are misled by are data and infographics. Often people take the mere existence of statistics or other data as evidence for a claim instead of investigating further.

Again the Crash Course video suggests seeking out the source and context for data and infographics. It suggests that students often see data as neutral and irrefutable, but that data is inherently biased as it is created by humans.

The video gives a real-world example of how data can be manipulated as a source of evidence by showing how two different news sources represented global warming data.

9. Teaching your students how search engines work and why to use click restraint

Another video from the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series is the video about how search engines work and click restraint . This video shows how search engines decide which information to list at the top of the search results. It also shows how search engines decide what information is relevant and of good quality.

The video gives search tips for using search engines to encourage the algorithms to return more reliable and accurate results.

This video is important when you are want to know how to teach research skills to high school students. This is because many students don’t understand why the first few results on a search are not necessarily the best information available.

10. Teach your students how to evaluate social media sources

One of the important research skills high school students need is to evaluate social media posts. Many people now get news and information from social media sites that have little to no oversight or editorial control. So, being able to evaluate posts for accuracy is key.

This video in the Crash Course Navigating Digital Information series also explains that social media sites are free to use because they make money from advertising. The advertising money comes from keeping people on the platform (and looking at the ads).

How do they keep people on the platform? By using algorithms that gather information about how long people spend on or react to different photos, posts and videos. Then, the algorithms will send viewers more content that is similar to the content that they view or interact with.

This prioritizes content that is controversial, shocking, engaging, attractive. It also reinforces the social norms of the audience members using the platform.

By teaching students how to combat the way that social media algorithms work, you can show them how to gather more reliable and relevant information in their everyday lives. Further, you help students work out if social media posts are relevant to (reliable for) their academic work.

11. Teaching your students how to cite sources

Another important research skill high school students need is how to accurately cite sources. A quick Google search turned up a few good free ideas:

- This lesson plan from the Brooklyn Library for grades 4-11. It aligns with the common core objectives and provides worksheets for students to learn to use MLA citation.

- This blog post about middle-school teacher Jody Passanini’s experiences trying to teach students in English and History how to cite sources both in-text and at the end with a reference list.

- This scavenger hunt lesson by 8th grade teacher on ReadWriteThink. It has a free printout asking students to prove assertions (which could be either student- or teacher-generated) with quotes from the text and a page number. It also has an example answer using the Catching Fire (Hunger Games) novel.

- The Chicago Manual of Style has this quick author-date citation guide .

- This page by Purdue Online Writing Lab has an MLA citation guide , as well as links to other citation guides such as APA.

If you are wanting other activities, a quick search of TPT showed these to be popular and well-received by other teachers:

- Laura Randazzo’s 9th edition MLA in-text and end-of-text citation activities

- Tracee Orman 8th edition MLA cheet sheet

- The Daring English Teacher’s MLA 8th edition citation powerpoint

12. Teaching your students to take notes

Another important skill to look at when considering how to teach research skills to high school students is whether they know how to take effective notes.

The Crash Course Study Skills note-taking video is great for this. It outlines three note-taking styles – the outline method, the Cornell method, and the mind map method. And it shows students how to use each of the methods.

This can help you start a conversation with your students about which styles of note-taking are most effective for different tasks.

For example, mind maps are great for seeing connections between ideas and brain dumps. The outline method is great for topics that are hierarchical. And the Cornell method is great for topics with lots of specific vocabulary.

Having these types of metacognitive discussions with your students helps them identify study and research strategies. It also helps them to learn which strategies are most effective in different situations.

Teaching research skills to high school students . . .

Doesn’t have to be

- time-consuming

The fantastic Crash Course Navigating Digital Information videos are a great way to get started if you are wondering how to teach research skills to high school students.

If you decide to use the videos in your class, you can buy individual worksheets if you have specific skills in mind. Or you can buy the full bundle if you think you’ll end up watching all of the videos.

Got any great tips for teaching research skills to high school students?

Head over to our Facebook or Instagram pages and let us know!

- Research Skills

How to Teach Online Research Skills to Students in 5 Steps (Free Posters)

Please note, this post was updated in 2020 and I no longer update this website.

How often does this scenario play out in your classroom?

You want your students to go online and do some research for some sort of project, essay, story or presentation. Time ticks away, students are busy searching and clicking, but are they finding the useful and accurate information they need for their project?

We’re very fortunate that many classrooms are now well equipped with devices and the internet, so accessing the wealth of information online should be easier than ever, however, there are many obstacles.

Students (and teachers) need to navigate:

- What search terms to put into Google or other search engines

- What search results to click on and read through (while avoiding inappropriate or irrelevant sites or advertisements)

- How to determine what information is credible, relevant and student friendly

- How to process, synthesize, evaluate , and present the information

- How to compare a range of sources to evaluate their reliability and relevancy

- How to cite sources correctly

Phew! No wonder things often don’t turn out as expected when you tell your students to just “google” their topic. On top of these difficulties some students face other obstacles including: low literacy skills, limited internet access, language barriers, learning difficulties and disabilities.

All of the skills involved in online research can be said to come under the term of information literacy, which tends to fall under a broader umbrella term of digital literacy.

Being literate in this way is an essential life skill.

This post offers tips and suggestions on how to approach this big topic. You’ll learn a 5 step method to break down the research process into manageable chunks in the classroom. Scroll down to find a handy poster for your classroom too.

How to Teach Information Literacy and Online Research Skills

The topic of researching and filtering information can be broken down in so many ways but I believe the best approach involves:

- Starting young and building on skills

- Embedding explicit teaching and mini-lessons regularly (check out my 50 mini-lesson ideas here !)

- Providing lots of opportunity for practice and feedback

- Teachers seeking to improve their own skills — these free courses from Google might help

- Working with your librarian if you have one

💡 While teaching research skills is something that should be worked on throughout the year, I also like the idea of starting the year off strongly with a “Research Day” which is something 7th grade teacher Dan Gallagher wrote about . Dan and his colleagues had their students spend a day rotating around different activities to learn more about researching online. Something to think about!

Google or a Kid-friendly Search Engine?

If you teach young students you might be wondering what the best starting place is.

I’ve only ever used Google with students but I know many teachers like to start with search engines designed for children. If you’ve tried these search engines, I’d love you to add your thoughts in a comment.

💡 If you’re not using a kid-friendly search engine, definitely make sure SafeSearch is activated on Google or Bing. It’s not foolproof but it helps.

Two search engines designed for children that look particularly useful include:

These sites are powered by Google SafeSearch with some extra filtering/moderating.

KidzSearch contains additional features like videos and image sections to browse. While not necessarily a bad thing, I prefer the simple interface of Kiddle for beginners.

Read more about child-friendly search engines

This article from Naked Security provides a helpful overview of using child-friendly search engines like Kiddle.

To summarise their findings, search-engines like Kiddle can be useful but are not perfect.

For younger children who need to be online but are far too young to be left to their own devices, and for parents and educators that want little ones to easily avoid age-inappropriate content, these search engines are quite a handy tool. For older children, however, the results in these search engines may be too restrictive to be useful, and will likely only frustrate children to use other means.

Remember, these sorts of tools are not a replacement for education and supervision.

Maybe start with no search engine?

Another possible starting point for researching with young students is avoiding a search engine altogether.

Students could head straight to a site they’ve used before (or choose from a small number of teacher suggested sites). There’s a lot to be learned just from finding, filtering, and using information found on various websites.

Five Steps to Teaching Students How to Research Online and Filter Information

This five-step model might be a useful starting point for your students to consider every time they embark on some research.

Let’s break down each step. You can find a summary poster at the end.

Students first need to take a moment to consider what information they’re actually looking for in their searches.

It can be a worthwhile exercise to add this extra step in between giving a student a task (or choice of tasks) and sending them off to research.

You could have a class discussion or small group conferences on brainstorming keywords , considering synonyms or alternative phrases , generating questions etc. Mindmapping might help too.

2016 research by Morrison showed that 80% of students rarely or never made a list of possible search words. This may be a fairly easy habit to start with.

Time spent defining the task can lead to a more effective and streamlined research process.

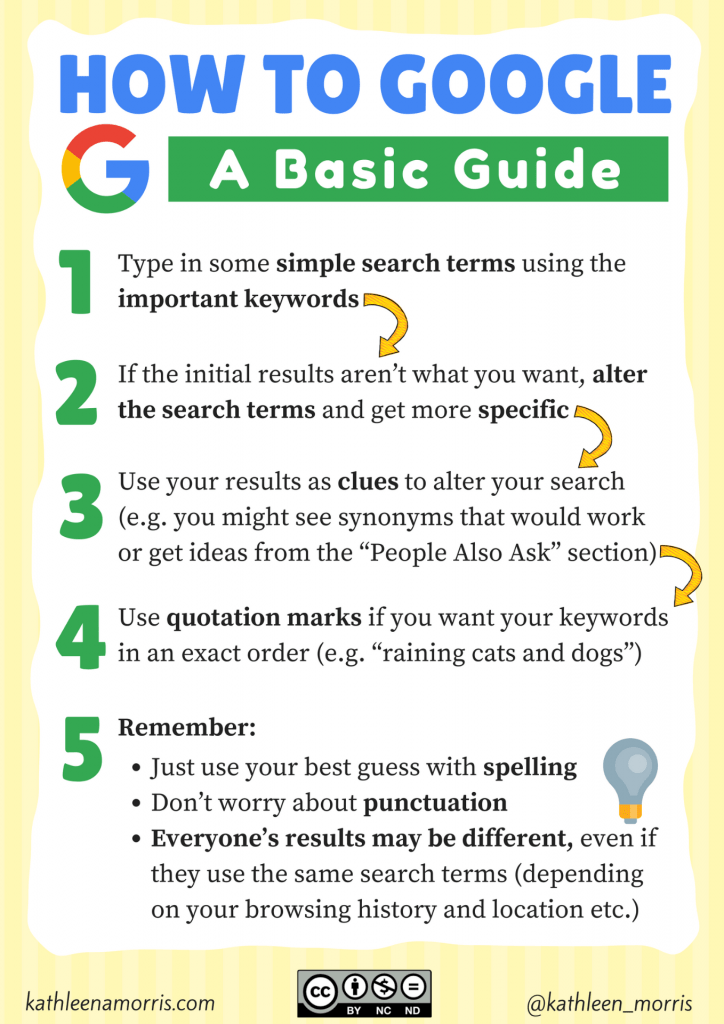

It sounds simple but students need to know that the quality of the search terms they put in the Google search box will determine the quality of their results.

There are a LOT of tips and tricks for Googling but I think it’s best to have students first master the basics of doing a proper Google search.

I recommend consolidating these basics:

- Type in some simple search terms using only the important keywords

- If the initial results aren’t what you want, alter the search terms and get more specific (get clues from the initial search results e.g. you might see synonyms that would work or get ideas from the “People Also Ask” section)

- Use quotation marks if you want your keywords in an exact order, e.g. “raining cats and dogs”

- use your best guess with spelling (Google will often understand)

- don’t worry about punctuation

- understand that everyone’s results will be different , even if they use the same search terms (depending on browser history, location etc.)

📌 Get a free PDF of this poster here.

Links to learn more about Google searches

There’s lots you can learn about Google searches.

I highly recommend you take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “instant searches”.

Med Kharbach has also shared a simple visual with 12 search tips which would be really handy once students master the basics too.

The Google Search Education website is an amazing resource with lessons for beginner/intermediate/advanced plus slideshows and videos. It’s also home to the A Google A Day classroom challenges. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

Useful videos about Google searches

How search works.

This easy to understand video from Code.org to explains more about how search works.

How Does Google Know Everything About Me?

You might like to share this video with older students that explains how Google knows what you’re typing or thinking. Despite this algorithm, Google can’t necessarily know what you’re looking for if you’re not clear with your search terms.

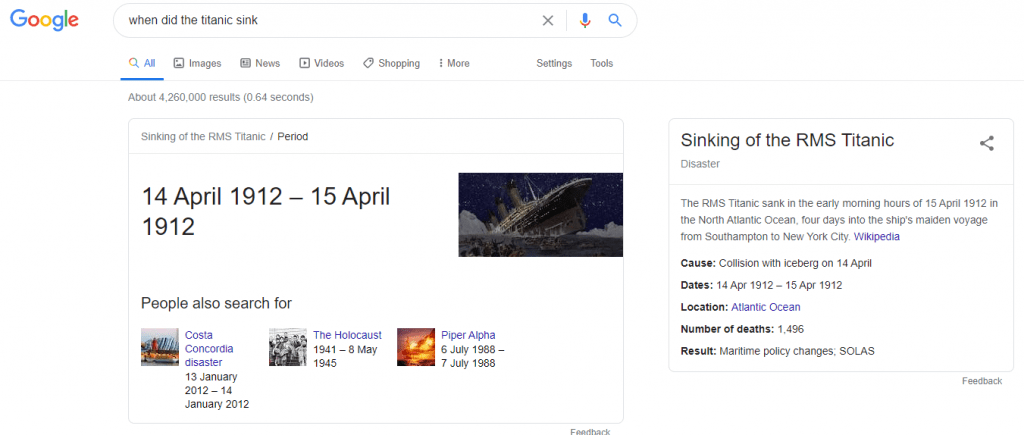

What about when the answer comes up in Google instantly?

If you’ve been using Google for a while, you know they are tweaking the search formula so that more and more, an answer will show up within the Google search result itself. You won’t even need to click through to any websites.

For example, here I’ve asked when the Titanic sunk. I don’t need to go to any websites to find out. The answer is right there in front of me.

While instant searches and featured snippets are great and mean you can “get an answer” without leaving Google, students often don’t have the background knowledge to know if a result is incorrect or not. So double checking is always a good idea.

As students get older, they’ll be able to know when they can trust an answer and when double checking is needed.

Type in a subject like cats and you’ll be presented with information about the animals, sports teams, the musical along with a lot of advertising. There are a lot of topics where some background knowledge helps. And that can only be developed with time and age.

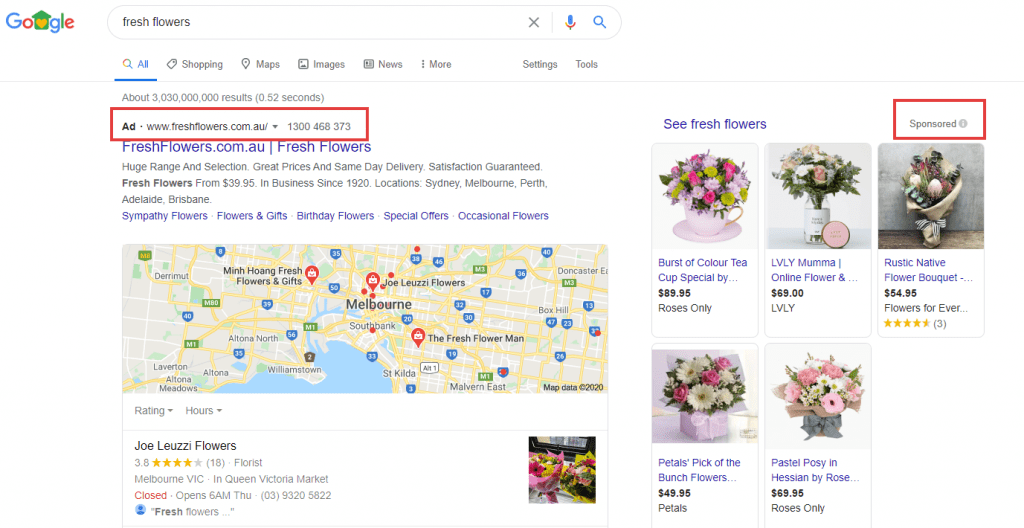

Entering quality search terms is one thing but knowing what to click on is another.

You might like to encourage students to look beyond the first few results. Let students know that Google’s PageRank algorithm is complex (as per the video above), and many websites use Search Engine Optimisation to improve the visibility of their pages in search results. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the most useful or relevant sites for you.

As pointed out in this article by Scientific American ,

Skilled searchers know that the ranking of results from a search engine is not a statement about objective truth, but about the best matching of the search query, term frequency, and the connectedness of web pages. Whether or not those results answer the searchers’ questions is still up for them to determine.

Point out the anatomy of a Google search result and ensure students know what all the components mean. This could be as part of a whole class discussion, or students could create their own annotations.

An important habit to get into is looking at the green URL and specifically the domain . Use some intuition to decide whether it seems reliable. Does the URL look like a well-known site? Is it a forum or opinion site? Is it an educational or government institution? Domains that include .gov or .edu might be more reliable sources.

When looking through possible results, you may want to teach students to open sites in new tabs, leaving their search results in a tab for easy access later (e.g. right-click on the title and click “Open link in new tab” or press Control/Command and click the link).

Searchers are often not skilled at identifying advertising within search results. A famous 2016 Stanford University study revealed that 82% of middle-schoolers couldn’t distinguish between an ad labelled “sponsored content” and a real news story.

Time spent identifying advertising within search results could help students become much more savvy searchers. Looking for the words “ad” and “sponsored” is a great place to start.

4) Evaluate

Once you click on a link and land on a site, how do you know if it offers the information you need?

Students need to know how to search for the specific information they’re after on a website. Teach students how to look for the search box on a webpage or use Control F (Command F on Mac) to bring up a search box that can scan the page.

Ensure students understand that you cannot believe everything you read . This might involve checking multiple sources. You might set up class guidelines that ask students to cross check their information on two or three different sites before assuming it’s accurate.

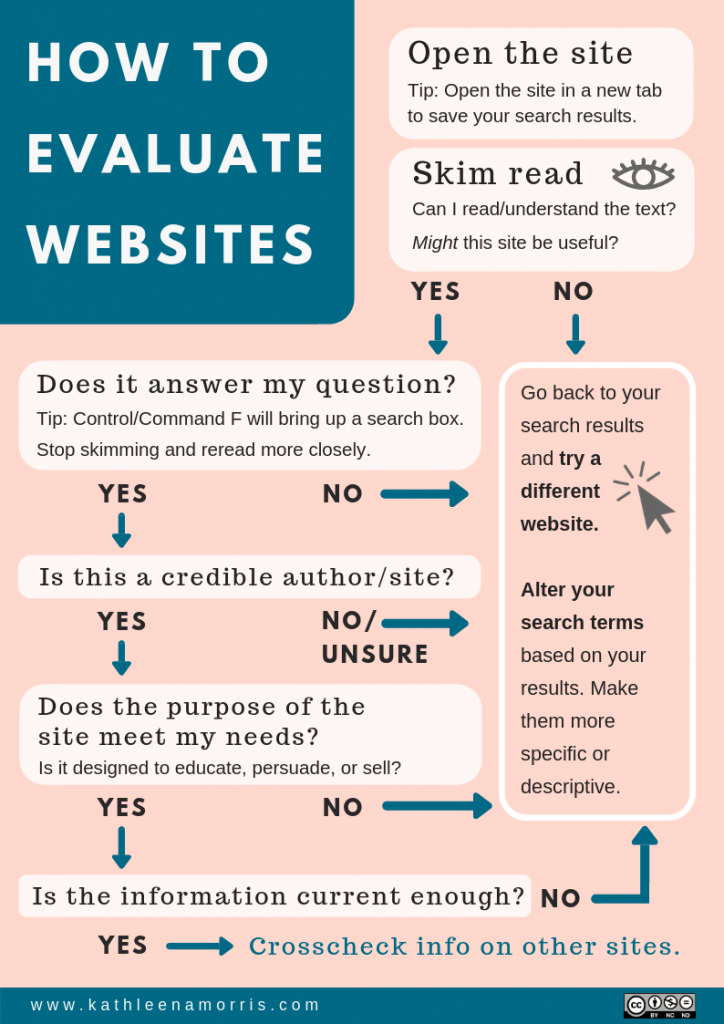

I’ve written a post all about teaching students how to evaluate websites . It includes this flowchart which you’re welcome to download and use in your classroom.

So your students navigated the obstacles of searching and finding information on quality websites. They’ve found what they need! Hooray.

Many students will instinctively want to copy and paste the information they find for their own work.

We need to inform students about plagiarism and copyright infringement while giving them the skills they need to avoid this.

- Students need to know that plagiarism is taking someone’s work and presenting it as your own. You could have a class discussion about the ethics and legalities of this.

- Students also need to be assured that they can use information from other sources and they should. They just need to say who wrote it, where it was from and so on.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

Give students lots of practice writing information in their own words. Younger students can benefit from simply putting stories or recounts in their own words. Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising .

There are some free online tools that summarise information for you. These aren’t perfect and aren’t a replacement from learning the skill but they could be handy for students to try out and evaluate. For example, students could try writing their own summary and then comparing it to a computer summary. I like the tool SMMRY as you can enter text or a URL of an article. Eric Curts shares a list of 7 summary tools in this blog post .

Students also need a lot of practice using quotation marks and citing sources .

The internet can offer a confusing web of information at times. Students need to be shown how to look for the primary source of information. For example, if they find information on Wikipedia, they need to cite from the bibliography at the bottom of the Wikipedia article, not Wikipedia itself.

There are many ways you can teach citation:

- I like Kathy Schrock’s PDF document which demonstrates how you can progressively teach citation from grades 1 to 6 (and beyond). It gives some clear examples that you could adapt for your own classroom use.

Staying organised!

You might also like to set up a system for students to organise their information while they’re searching. There are many apps and online tools to curate, annotate, and bookmark information, however, you could just set up a simple system like a Google Doc or Spreadsheet.

The format and function is simple and clear. This means students don’t have to put much thought into using and designing their collections. Instead, they can focus on the important curation process.

Bring These Ideas to Life With Mini-Lessons!

We know how important it is for students to have solid research skills. But how can you fit teaching research skills into a jam-packed curriculum? The answer may be … mini-lessons !

Whether you teach primary or secondary students, I’ve compiled 50 ideas for mini-lessons.

Try one a day or one a week and by the end of the school year, you might just be amazed at how independent your students are becoming with researching.

Become an Internet Search Master with This Google Slides Presentation

In early 2019, I was contacted by Noah King who is a teacher in Northern California.

Noah was teaching his students about my 5 step process outlined in this post and put together a Google Slides Presentation with elaboration and examples.

You’re welcome to use and adapt the Google Slides Presentation yourself. Find out exactly how to do this in this post.

The Presentation was designed for students around 10-11 years old but I think it could easily be adapted for different age groups.

Recap: How To Do Online Research

Despite many students being confident users of technology, they need to be taught how to find information online that’s relevant, factual, student-friendly, and safe.

Keep these six steps in mind whenever you need to do some online research:

- Clarify : What information are you looking for? Consider keywords, questions, synonyms, alternative phrases etc.

- Search : What are the best words you can type into the search engine to get the highest quality results?

- Delve : What search results should you click on and explore further?

- Evaluate : Once you click on a link and land on a site, how do you know if it offers the information you need?

- Cite : How can you write information in your own words (paraphrase or summarise), use direct quotes, and cite sources?

- Staying organised : How can you keep the valuable information you find online organised as you go through the research process?

Don’t forget to ask for help!

Lastly, remember to get help when you need it. If you’re lucky enough to have a teacher-librarian at your school, use them! They’re a wonderful resource.

If not, consult with other staff members, librarians at your local library, or members of your professional learning network. There are lots of people out there who are willing and able to help with research. You just need to ask!

Being able to research effectively is an essential skill for everyone . It’s only becoming more important as our world becomes increasingly information-saturated. Therefore, it’s definitely worth investing some classroom time in this topic.

Developing research skills doesn’t necessarily require a large chunk of time either. Integration is key and remember to fit in your mini-lessons . Model your own searches explicitly and talk out loud as you look things up.

When you’re modelling your research, go to some weak or fake websites and ask students to justify whether they think the site would be useful and reliable. Eric Curts has an excellent article where he shares four fake sites to help teach students about website evaluation. This would be a great place to start!

Introduce students to librarians ; they are a wonderful resource and often underutilised. It pays for students to know how they can collaborate with librarians for personalised help.

Finally, consider investing a little time in brushing up on research skills yourself . Everyone thinks they can “google” but many don’t realise they could do it even better (myself included!).

You Might Also Enjoy

Teaching Digital Citizenship: 10 Internet Safety Tips for Students

Free Images, Copyright, And Creative Commons: A Guide For Teachers And Students

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

14 Replies to “How to Teach Online Research Skills to Students in 5 Steps (Free Posters)”

Kathleen, I like your point about opening up sites in new tabs. You might be interested in Mike Caulfield’s ‘four moves’ .

What a fabulous resource, Aaron. Thanks so much for sharing. This is definitely one that others should check out too. Even if teachers don’t use it with students (or are teaching young students), it could be a great source of learning for educators too.

This is great information and I found the safe search sites you provided a benefit for my children. I searched for other safe search sites and you may want to know about them. http://www.kids-search.com and http://www.safesearch.tips .

Hi Alice, great finds! Thanks so much for sharing. I like the simple interface. It’s probably a good thing there are ads at the top of the listing too. It’s an important skill for students to learn how to distinguish these. 🙂

Great website! Really useful info 🙂

I really appreciate this blog post! Teaching digital literacy can be a struggle. This topic is great for teachers, like me, who need guidance in effectively scaffolding for scholars who to use the internet to gain information.

So glad to hear it was helpful, Shasta! Good luck teaching digital literacy!

Why teachers stopped investing in themselves! Thanks a lot for the article, but this is the question I’m asking myself after all teachers referring to google as if it has everything you need ! Why it has to come from you and not the whole education system! Why it’s an option? As you said smaller children don’t need search engine in the first place! I totally agree, and I’m soo disappointed how schooling system is careless toward digital harms , the very least it’s waste of the time of my child and the most being exposed to all rubbish on the websites. I’m really disappointed that most teachers are not thinking taking care of their reputation when it comes to digital learning. Ok using you tube at school as material it’s ok , but why can’t you pay little extra to avoid adverts while teaching your children! Saving paper created mountains of electronic-toxic waste all over the world! What a degradation of education.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Shohida. I disagree that all schooling systems are careless towards ‘digital harms’, however, I do feel like more digital citizenship education is always important!

Hi Kathleen, I love your How to Evaluate Websites Flow Chart! I was wondering if I could have permission to have it translated into Spanish. I would like to add it to a Digital Research Toolkit that I have created for students.

Thank you! Kristen

Hi Kristen, You’re welcome to translate it! Please just leave the original attribution to my site on there. 🙂 Thanks so much for asking. I really hope it’s useful to your students! Kathleen

[…] matter how old your child is, there are many ways for them to do research into their question. For very young children, you’ll need to do the online research work. Take your time with […]

[…] digs deep into how teachers can guide students through responsible research practices on her blog (2019). She suggests a 5 step model for elementary students on how to do online […]

Writing lesson plans on the fly outside of my usual knowledge base (COVID taken down so many teachers!) and this info is precisely what I needed! Thanks!!!

Comments are closed.

Research Lesson Plan: Research to Build and Present Knowledge

*Click to open and customize your own copy of the Research Lesson Plan .

This lesson accompanies the BrainPOP topic Research , and supports the standard of gathering relevant information from multiple sources. Students demonstrate understanding through a variety of projects.

Step 1: ACTIVATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

Prompt students to think of a time they had to do research, either for school or for themselves. Ask:

- How did you determine what information to look for?

- What went well? What was challenging?

Step 2: BUILD BACKGROUND

- Read aloud the description on the Research topic page .

- Play the Movie , pausing to check for understanding.

- Have students read one of the following Related Reading articles: “Way Back When” or “In Depth.” Partner them with someone who read a different article to share what they learned with each other.

Step 3: ENGAGE Students express what they learned about research while practicing essential literacy skills with one or more of the following activities. Differentiate by assigning ones that meet individual student needs.

- Make-a-Movie : Create a tutorial that answers this question: What are the steps for writing a research report? (Essential Literacy Skill: Acquire and use domain specific words and phrases)

- Make-a-Map : Make a spider map in which you state a research question in the center, and around it, identify sub questions and sources for finding answers in order to write a research report. (Essential Literacy Skill: Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources)

- Creative Coding : Code a museum where each artifact represents a component of the research process. (Essential Literacy Skill: Make logical inferences from explicit details)

Step 4: APPLY & ASSESS

Apply : Students t ake the Research Challenge , applying essential literacy skills while demonstrating what they learned about this topic.

Assess: Wrap up the lesson with the Research Quiz .

Step 5: EXTEND LEARNING

Related BrainPOP Topics : Deepen understanding of research with these topics: Online Sources , Internet Search , and Citing Sources .

Additional Support Resources:

- Pause Point Overview : Video tutorial showing how Pause Points actively engage students to stop, think, and express ideas.

- Modifications for BrainPOP Learning Activities: Strategies to meet ELL and other instructional and student needs.

- BrainPOP Learning Activities Support: Resources for best practices using BrainPOP.

- BrainPOP Jr. (K-3)

- BrainPOP ELL

- BrainPOP Science

- BrainPOP Español

- BrainPOP Français

- Set Up Accounts

- Single Sign-on

- Manage Subscription

- Quick Tours

- About BrainPOP

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Trademarks & Copyrights

Toolkit for Teaching Research at Princeton

- Toolkit Home

- All Things Canvas

- Teaching for the Writing Seminars

- Remote Teaching

- Faculty Collaboration Checklist

General Orientation to the Library

Database/catalog searching, developing and narrowing a research topic, teaching how to evaluate sources, citing sources/citation management, orienting departmental majors to library resources, lesson plans for teaching remotely.

- Bank of Exit and Learning Assessment Surveys

- Bibliographic Management (Zotero, Endnote, Etc)

- Models, Standards, etc.

- Professional Resources & Bibliography

- Discussion Board This link opens in a new window

- User-facing Instruction Pages @PUL

- extended access

(These were created for writing seminars but can be used for other courses)

- The Great Library Treasure Hunt Created by Kachina Allen and Audrey Welber for a Writing Seminar

- Library Treasure Hunt (Created by Audrey Welber for "Celebrity" Writing Seminar)

- You Love the Library Treasure Hunt created by Raf Allison

- First and Second Session Lesson Plans by Darwin Scott for "Decoding Dress"

- Library "Jeopardy" by Elana Broch

- Slavery WRI; library research & assessing sources R. Friedman w/N. Elder

- Intro to the Library Collaboration and Search Techniques

- Developing a Research Topic (Shannon Winston)

- Topic Formation in Library (Caswell-Klein)

*********************************************************************************************************************************

Lesson Plans Shared at our Fall 2023 "Working Brunch":

Alain St. Pierre || Steve Knowlton 1 || Steve Knowlton 2 || Steve Knowlton 3 || Audrey Welber

(These were created for writing seminars but can be used for other courses.)

- Finding Your Dream Source Created by Greg Spears and Audrey Welber for "Music and Madness"

- Dream Source Sample Exercise Created by Sam Garcia and Audrey Welber

- Library Discovery Session Exercises Created by Writing Seminar Faculty member Cecily Swanson

- Advanced searching tips for Articles+ and the Library Catalog Intended as a Pre-draft assignment for Unit 3; it can easily be split up into two separate assignments/lessons.

- WRI 146 - session 1 R. Friedman w/instructor E. Ljung; exploring library resources and museum objects

- Narrowing Your Topic

- CRAAP Test for Evaluating Sources Created by Alex Davis for "Politics of Intimacy"

- Evaluating resources UC-Berkeley LibGuide: General, Scholarly vs. Popular, Primary and Secondary

- Evaluating Sources Created by Raf Allison

- Zotero Libguide (created by Audrey Welber)

- A short "getting started" video tutorial A 5 minute crash course on using Zotero at Princeton. Zotero can save you hours of frustration because it enables you to quickly import and organize your materials as you do your research and easily insert citations into Word (and google doc, Scrivener, Latek, etc) as you write. Zotero also generates a bibliography based on the sources you've cited (but can also create a standalone bibliography.)

- Endnote, Basic

- MolBio Junior Tutorial

- MolBio Tutorial Reflection reflection of how the lesson went

Preparation for your Zoom session:

A 10 minute getting started video from Zoom company

Preparation for your Zoom session for the Writing Seminars/important details about using Zoom with a class (culled from brainstorm session with many teaching librarians on 3/20)

Lesson plans/exercises:

Research Clinic

Outline Session #1

One of Audrey's lesson plans for first session

Elana's plan (4 short sessions)

Denise's plan for a Freshman Writing Seminar

Research Clinic Research clinic sample plan

Mini exercises

Videos created for flipped classroom ("asychronous" learning)

Thomas Keenan: 5 videos for a Writing Seminar Discovery Session

Wayne Bivens-Tatum: Zoom video creation tutorial (for a subject area class)

Audrey Welber: Articles+, Catalog, and Zotero

- << Previous: Faculty Collaboration Checklist

- Next: Bank of Exit and Learning Assessment Surveys >>

- Last Updated: Sep 10, 2024 12:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/teachingtoolkit

Lesson Plan

Harness your research skills, view aligned standards, learning objectives.

Students will be able to conduct research and present their information on a topic of their choice.

Introduction

- Ask students to describe a time they became interested in a topic (e.g., baseball, dancing, Greek mythology, baking cupcakes). Ask them to describe what they did to learn more about the topic. Record student answers.

- Explain to students that one can conduct research when they are curious about a topic and want to learn more about it. Tell students that research can be done by reading various sources, conducting interviews, or giving surveys to people who are connected to the topic you are researching.

- Tell students that today they will choose a topic that interests them. They will conduct research on the topic, take notes and record the sources of information, and present the research to their classmates.

Think Like a Researcher: Instruction Resources: #6 Developing Successful Research Questions

- Guide Organization

- Overall Summary

- #1 Think Like a Researcher!

- #2 How to Read a Scholarly Article

- #3 Reading for Keywords (CREDO)

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research (Alternate)

- #5 Integrating Sources

- Research Question Discussion

- #7 Avoiding Researcher Bias

- #8 Understanding the Information Cycle

- #9 Exploring Databases

- #10 Library Session

- #11 Post Library Session Activities

- Summary - Readings

- Summary - Research Journal Prompts

- Summary - Key Assignments

- Jigsaw Readings

- Permission Form

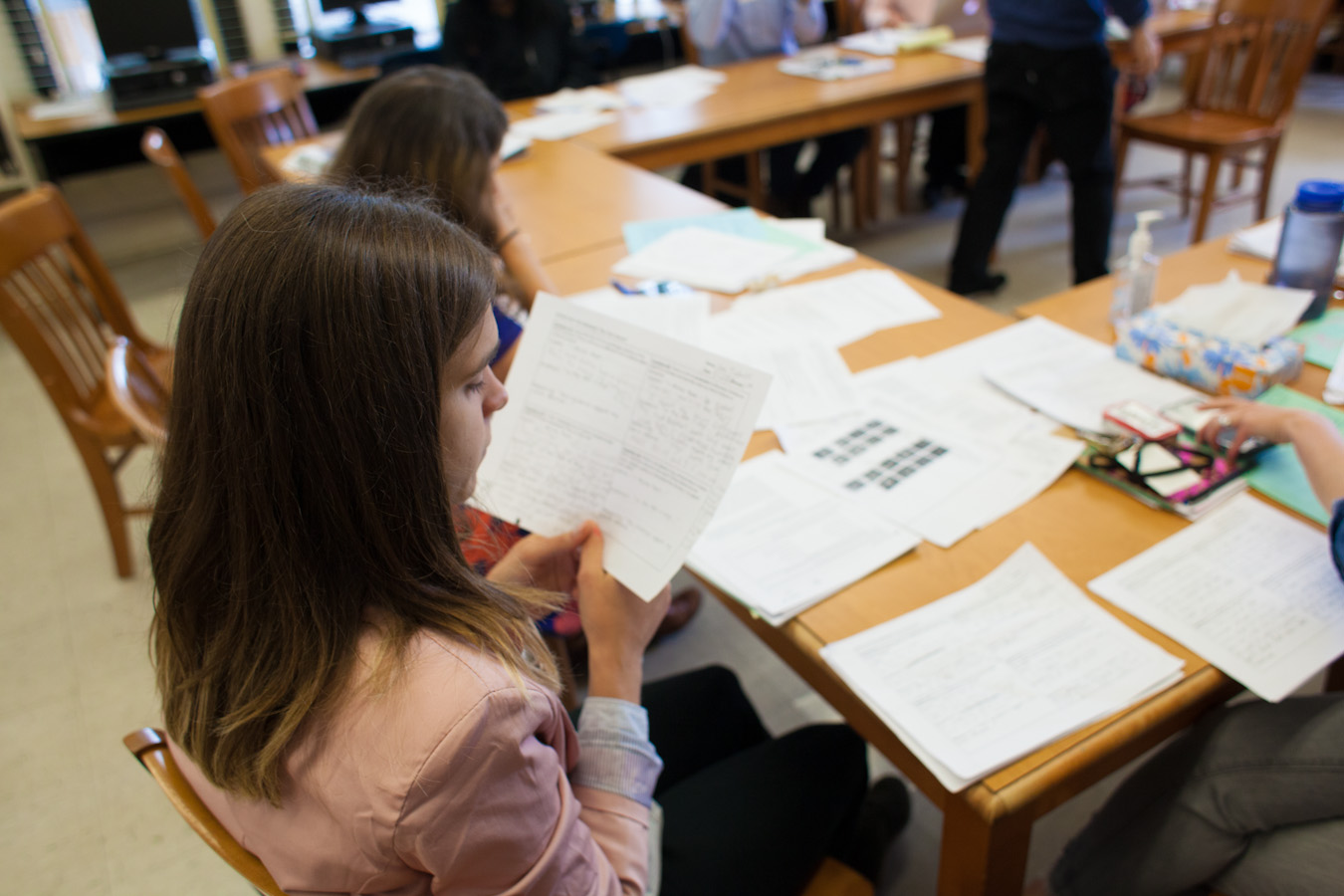

Course Learning Outcome: Develop ability to synthesize and express complex ideas; demonstrate information literacy and be able to work with evidence

Goal: Develop students’ ability to recognize and create successful research questions

Specifically, students will be able to

- identify the components of a successful research question.

- create a viable research question.

What Makes a Good Research Topic Handout

These handouts are intended to be used as a discussion generator that will help students develop a solid research topic or question. Many students start with topics that are poorly articulated, too broad, unarguable, or are socially insignificant. Each of these problems may result in a topic that is virtually un-researchable. Starting with a researchable topic is critical to writing an effective paper.

Research shows that students are much more invested in writing when they are able to choose their own topics. However, there is also research to support the notion that students are completely overwhelmed and frustrated when they are given complete freedom to write about whatever they choose. Providing some structure or topic themes that allow students to make bounded choices may be a way mitigate these competing realities.

These handouts can be modified or edited for your purposes. One can be used as a handout for students while the other can serve as a sample answer key. The document is best used as part of a process. For instance, perhaps starting with discussing the issues and potential research questions, moving on to problems and social significance but returning to proposals/solutions at a later date.

- Research Questions - Handout Key (2 pgs) This document is a condensed version of "What Makes a Good Research Topic". It serves as a key.

- Research Questions - Handout for Students (2 pgs) This document could be used with a class to discuss sample research questions (are they suitable?) and to have them start thinking about problems, social significance, and solutions for additional sample research questions.

- Research Question Discussion This tab includes materials for introduction students to research question criteria for a problem/solution essay.

Additional Resources

These documents have similarities to those above. They represent original documents and conversations about research questions from previous TRAIL trainings.

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? - Original Handout (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan. 2016 (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan 2016 with comments

Topic Selection (NCSU Libraries)

Howard, Rebecca Moore, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigues. " Writing from sources, writing from sentences ." Writing & Pedagogy 2.2 (2010): 177-192.

Research Journal

Assign after students have participated in the Developing Successful Research Topics/Questions Lesson OR have drafted a Research Proposal.

Think about your potential research question.

- What is the problem that underlies your question?

- Is the problem of social significance? Explain.

- Is your proposed solution to the problem feasible? Explain.

- Do you think there is evidence to support your solution?

Keys for Writers - Additional Resource

Keys for Writers (Raimes and Miller-Cochran) includes a section to guide students in the formation of an arguable claim (thesis). The authors advise students to avoid the following since they are not debatable.

- "a neutral statement, which gives no hint of the writer's position"

- "an announcement of the paper's broad subject"

- "a fact, which is not arguable"

- "a truism (statement that is obviously true)"

- "a personal or religious conviction that cannot be logically debated"

- "an opinion based only on your feelings"

- "a sweeping generalization" (Section 4C, pg. 52)

The book also provides examples and key points (pg. 53) for a good working thesis.

- << Previous: #5 Integrating Sources

- Next: Research Question Discussion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/think_like_a_researcher

Research Building Blocks: "Cite Those Sources!"

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Children are naturally curious—they want to know "how" and "why." Teaching research skills can help students find answers for themselves. This lesson is taken from a research skills unit where the students complete a written report on a state symbol. Here, students learn the importance of citing their sources to give credit to the authors of their information as well as learn about plagiarism. They explore a Website about plagiarism to learn the when and where of citing sources as well as times when citing sources is not necessary. They look at examples of acceptable and unacceptable paraphrasing. Finally, students practice citing sources and creating a bibliography.

Featured Resources

Avoiding Plagiarism : This resource from Purdue OWL gives comprehensive advice about how to avoid plagiarism.

From Theory to Practice

Teaching the process and application of research should be an ongoing part of all school curricula. It is important that research components are taught all through the year, beginning on the first day of school. Dreher et al. explain that "[S]tudents need to learn creative and multifaceted approaches to research and inquiry. The ability to identify good topics, to gather information, and to evaluate, assemble, and interpret findings from among the many general and specialized information sources now available to them is one of the most vital skills that students can acquire" (39).

Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

- Chart paper

- Internet access

Student Objectives

Students will

- discuss plagiarism.

- practice paraphrasing.

- credit sources used in research.

Instruction & Activities

- It is very important for students to understand the need for, and purpose of, giving credit to the sources they use in the research process. The students need to learn about the concept of plagiarism. Plagiarism is using others' ideas or words without clearly acknowledging the source of that information. While discussing the concept of plagiarism, use this avoiding plagiarism Web page to learn the when and where of citing sources as well as times when citing sources is not necessary.

- To remind students of the basic rules to avoid plagiarism, write the following on chart paper and post it close to the research area or media center in the classroom.

another person's idea, opinion, or theory.

any facts, statistics, graphs, drawings-any pieces of information-that are not common knowledge.

quotations of another person's actual spoken or written words.

paraphrases of another person's spoken or written words.

- After the discussion, use the example paragraph from How to Recognize Unacceptable and Acceptable Paraphrases to show the appropriate/inappropriate way to paraphrase information.

- providing them with a group of resources to create a bibliography for frequent practice in an activity or learning-center situation. Creating a Bibliography for Your Report discusses the various components of a bibliography.

- modeling the step-by-step development of a bibliography for your class in a variety of settings and subject areas.

- posting the standard bibliography format in a prominent place in your classroom.

Student Assessment / Reflections

As this is only one step in teaching the research process, students need not be graded on the activity. Continued practice in paraphrasing and quoting material is most important, with teacher and peer feedback benefitting the student researcher. Final bibliographies turned in with the research report could then be graded based on accurate information and style.

- Professional Library

- Lesson Plans

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

- All eBooks & Audiobooks

- Academic eBook Collection

- Home Grown eBook Collection

- Off-Campus Access

- Literature Resource Center

- Opposing Viewpoints

- ProQuest Central

- Course Guides

- Citing Sources

- Library Research

- Websites by Topic

- Book-a-Librarian

- Research Tutorials

- Use the Catalog

- Use Databases

- Use Films on Demand

- Use Home Grown eBooks

- Use NC LIVE

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Make an Appointment

- Writing Tools

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing Center

Service Alert

Research 101

- ACRL Framework Alignment

- Before You Begin...

- Lesson 1: Choose a Research Topic

- Lesson 2: Develop a Research Strategy

- Lesson 3: Conduct Ongoing Research

- Lesson 4: Analyze & Review Sources

- Lesson 5: Use Information Effectively

- After You Finish...

- Acknowledgements

Text: 336-308-8801

Email: [email protected]

Call: 336-633-0204

Schedule: Book-a-Librarian

Like us on Facebook

Links on this guide may go to external web sites not connected with Randolph Community College. Their inclusion is not an endorsement by Randolph Community College and the College is not responsible for the accuracy of their content or the security of their site.

All links on this page open in a new window.

Lesson 1: Choose a Research Topic

In this chapter, you'll learn to:

- Formulate questions for research, based on information gaps or on reexamination of existing, possibly conflicting, information.

- Recognize that you, the researcher, are often entering into an ongoing scholarly conversation, not a finished conversation.

- Conduct background research to develop research strategies.

- Instructions

- 1) Scholarly Conversations

- 2) Research Topic

- 3) Research Question

Click on the numbered tabs to complete each activity.

Activities include videos, tutorials, and interactive tasks.

Questions about this lesson will be included on the Research 101 Quiz.

*It is recommended that you take notes while you complete each activity to prepare for the Research 101 quiz.

*If you have to take a break, make a note of your last activity so that you can pick up where you left off later.

"Choosing a Topic" Video by Amanda Burbage

This introductory video explains how when you choose a research topic, you are actually joining an ongoing academic conversation.

- "Choosing a Topic" Video Transcript

- CC BY-SA 4.0

"Scholarly Conversations" Tutorial by New Literacies Alliance

"In this lesson, students will discover how research is like a conversation that takes place between scholars in a field and will investigate ways they can become part of the conversation over time." -NewLiteraciesAlliance.org

"Scholarly Conversations" Tutorial

1. Click on the tutorial link above.

2. Click the green "Sign In" button to login to your New Literacies Alliance account before beginning the tutorial .

*Go to the "Before You Begin" page of Research 101 if you have not yet registered for an account.

3. Click the green "View Course" button.

4. Click the plus sign beside "Lesson".

5. Click the link that appears below to begin the tutorial.

- CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

"Picking Your Topic IS Research" Video by NC State University Libraries

This video explains that before you begin a project, you should do some preliminary research on your topic. This is a cyclical process, involving collecting background information and tweaking, to construct an interesting topic that you can further explore in your paper.

- "Picking Your Topic IS Research" Video Transcript

"Using Wikipedia for Academic Research (CLIP)" Video by Michael Baird

Although Wikipedia is not a suitable source for an academic research paper, it can still be very helpful! This video explains how this online encyclopedia can serve as a treasure trove of topic phrases, keywords, names, dates, and citations that you can use throughout the research process.

NOTE: Audio begins at 0.18 seconds.

- "Using Wikipedia for Academic Research (CLIP)" Video Transcript

"How to Develop a STRONG Research Question" Video by Scribbr

This video explains how to turn your research topic into a research question that is focused, researchable, feasible, specific, complex, and relevant.

- "How to Develop a STRONG Research Question" Video Transcript

- Scribbr Video Citation

"Ask the Right Questions" Tutorial by New Literacies Alliance

"In this lesson, students will explore what it takes to narrow a search in order to find the best information." -NewLiteraciesAlliance.org

"Ask the Right Questions" Tutorial

- << Previous: Before You Begin...

- Next: Lesson 2: Develop a Research Strategy >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://libguides.randolph.edu/R101

GET TEACHING TIPS AND FREE RESOURCES

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

The Brown Bag Teacher

Teach the Children. Love the Children. Change the World.

January 12, 2020

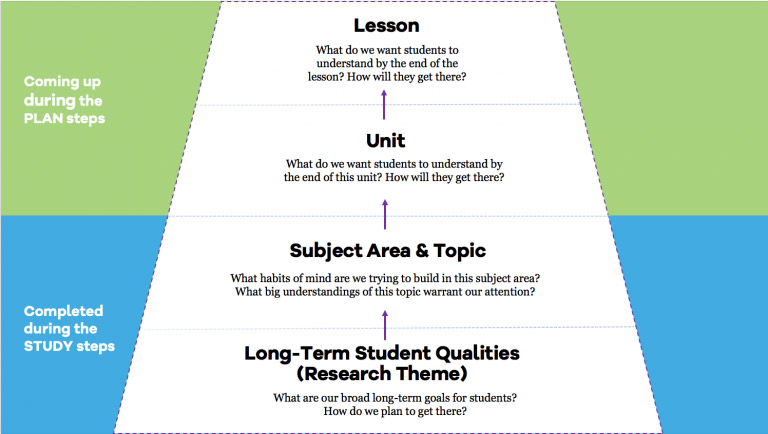

Organizing Research in 1st & 2nd Grade

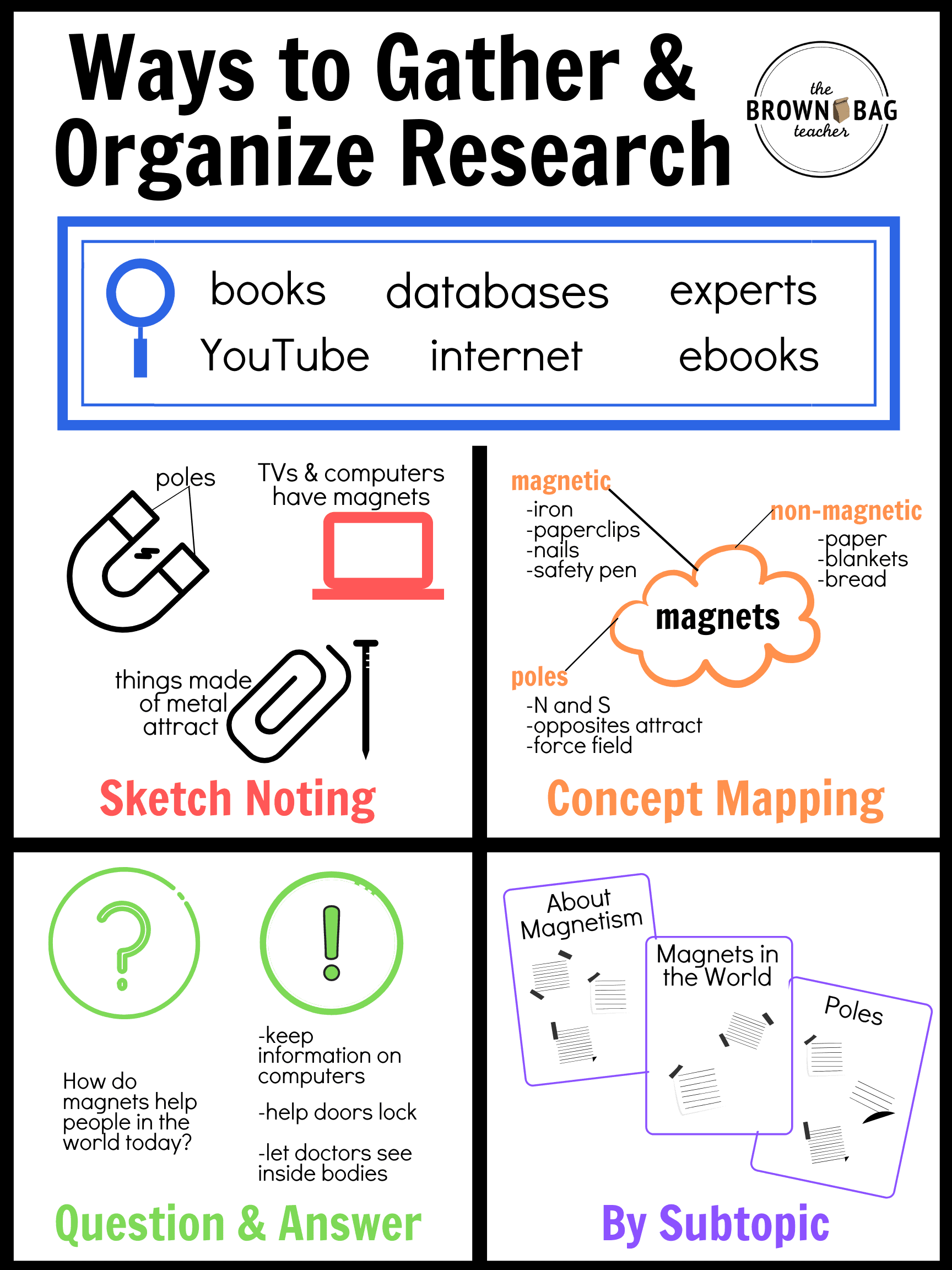

Independent research in 1st and 2nd Grade is not something that just magically happens. Organizing writing is not something that just happens automatically. Both of these skills have to be explicitly modeled and scaffolded for students. The great news? When given the opportunity, students rise. The Common Core Standards ask our 1st and 2nd grade students to “Participate in shared research and writing projects”, as well as, “…gather information from provided sources to answer a question.” Our students are very capable of participating in real-world research with the appropriate scaffolds, supports, and explicit instruction. But how do we get there?

Where Do We Get Our Research in 1st & 2nd Grade?

Initially, research in 1st and 2nd Grade begins with books ( Pebble Go and National Graphic Kids are some of our favorites). I’ll also print articles and books from Reading AZ and Read Works if they are available. (If you have RAZ Kids, then you can just assign the Reading AZ texts to specific students and they can access them online. #savethetrees). Starting with print resources help me better manage the research and allows us to learn basic research skills before integrating technology.

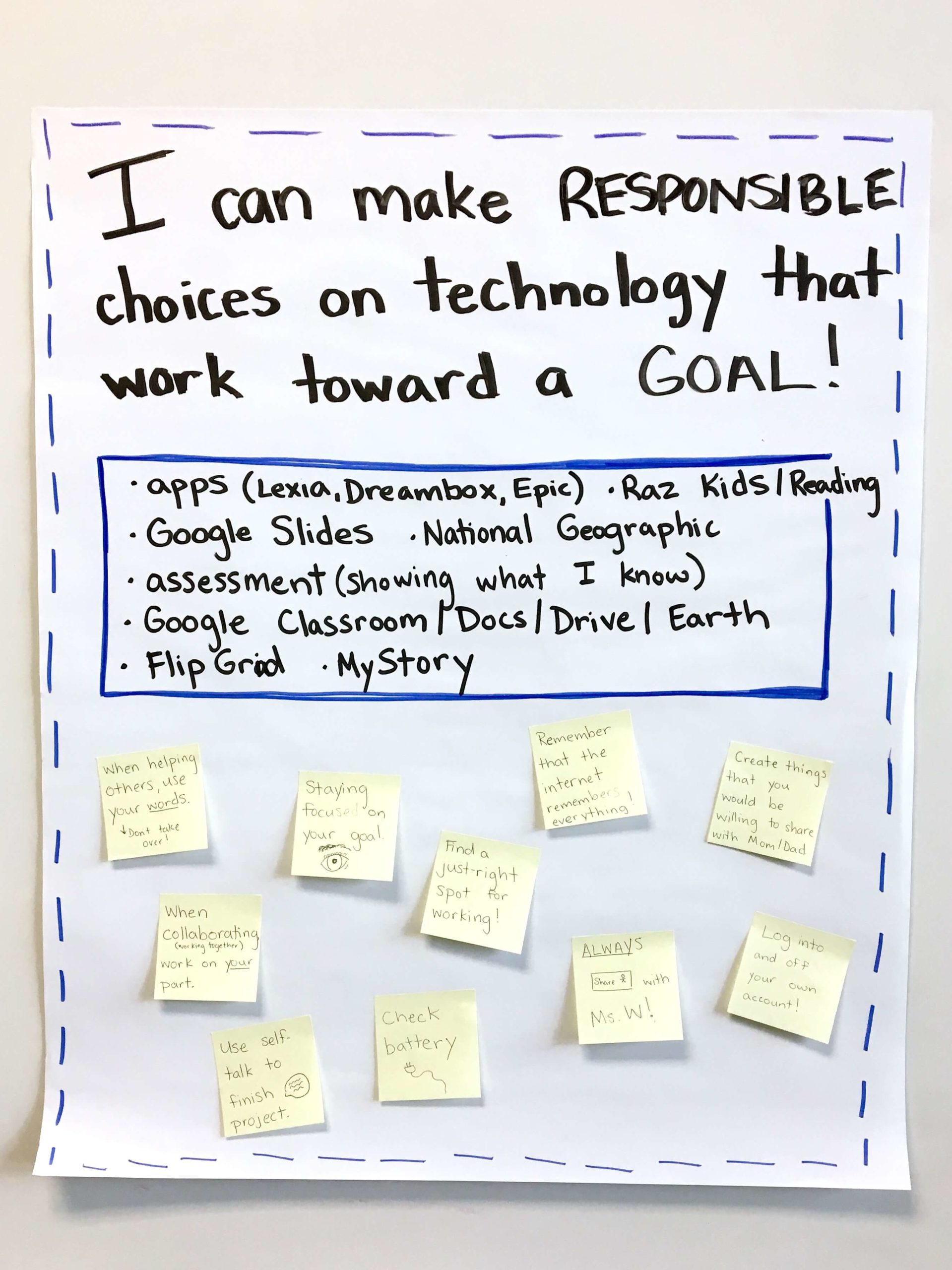

Then, we slowly branch to ebooks using EPIC . I’m able to create topic specific collections for students and share them directly to their EPIC accounts. From there, we model using videos from YouTube ( SciShow Kids ). Now, the SciShow Kids videos are on Epic , so it’s even safer!! (Note – These are 6 and 7 year olds. In my classroom, they will not have the privilege or responsibility to freely roam the internet or YouTube.)

Finally we branch into online databases (all KY schools have free access to Kentucky Virtual Library) and teacher-chosen websites. I link specific websites students are allowed to visit from Google Classroom. As we explore these online resources, we have frequent conversations about internet safety and internet expectations. When online, our choices should always help us become better readers, writers, and humans.

Scaffolding research collection in this way allows me the opportunity to model expectations for each resource and how to use it, as well as, ensure students are safe.

Why Organize Research in 1st & 2nd Grade?

Organizing and structuring writing is not a skill that is innate within students. Students have to be explicitly taught executive functioning skills – such as organization. Additionally, when we research I don’t want students just copying down an entire book or webpage. The world’s most random collection of information will not be helpful in sharing our learning down the road. Researching in 1st and 2nd Grade means we invest the time to learn, read, model, practice, and tweak together.

When teaching students to gather and organize information, there are DOZENS of structures for doing it. As a teacher, I typically pick 3-4 different ways that are developmentally appropriate for my 1st and 2nd graders, as well as, lend themselves to the types of research we will be doing.

Planning of Instruction

Reading and writing are forever connected and they should be. We can leverage each one to ensure that students see both subjects in context, as well as, part of their daily lives. Additionally, as I am preparing for our research unit , we will leverage whatever we are learning in science and/or social studies. This ensures students have the background to do specific research about a topic, rather than “All About Monkeys”.

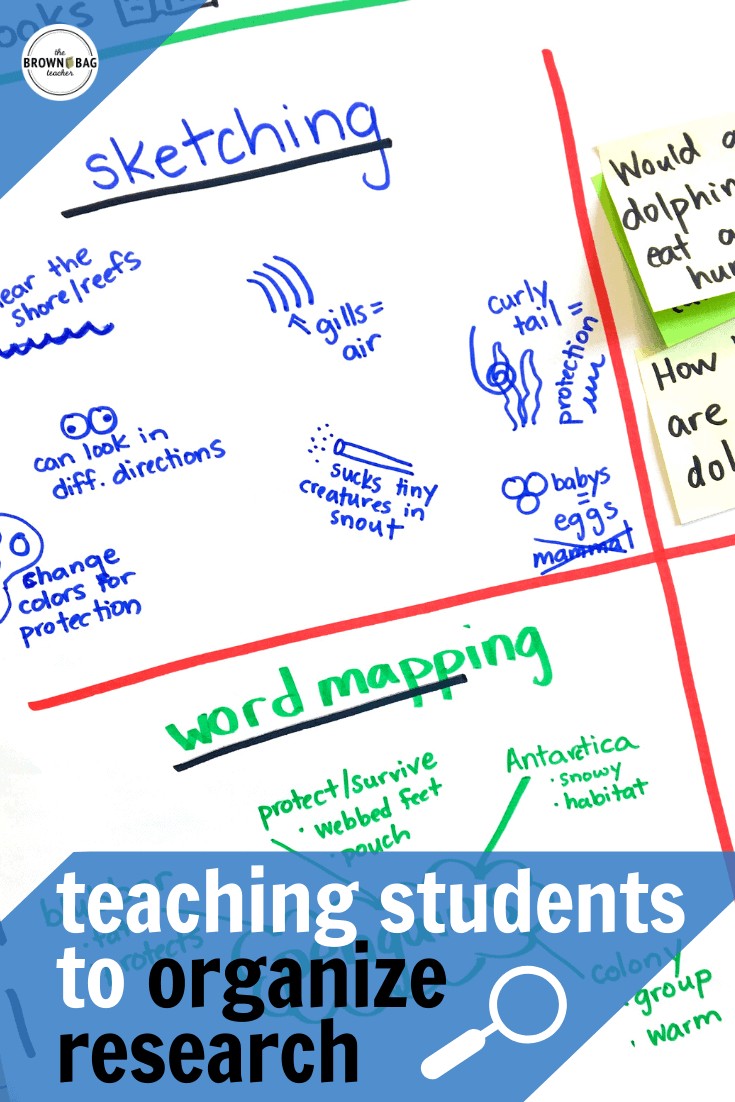

As new strategies for organizing research are explored we do not abandon all the others. Rather, the strategies we learn are ones that can easily be combined. Sketch noting is the best example of this. It can be a part of a concept map, questions and answers, and/or creating subtopics.

As I introduce ways to organize writing , I will typically do it as a part of our reading or science mini-lessons. The strategy is modeled in the context of content and then, we practice again together during writing. Next, students typically work in partners to try the strategy out and ultimately, they work independently. Some students will need more teacher support in independently researching and that’s okay.

Sketch Noting

Sketch noting is typically the first way students to collect research. It is the most kid-friendly and non-threatening. As a class, we read a text from our science or social studies learning and then, consider the big ideas. (At this point, we haven’t talked about developing a research question, so our information gathering is broad.) We talk about the ideas and what symbols or pictures represent them. Then, we discuss importance of including captions that contain important vocabulary, people, ideas, and numbers. Sketch notes don’t need to be in complete sentences, so it’s fine to write single words, bullets, or fragments.

Teaching students to create subtopics is a great way to start narrowing the research field. From all-the-random-facts to these-facts-fit-the-subtopics-I-have-chosen, students are to start differentiating between important information and “fun extras”.

The use of subheadings is easily modeled using the table of contents in informational texts. We spend time looking at these texts, noticing what subtopics the author chose to write about, and what types of information he/she included (and didn’t include).

As students choose subtopics, we put each subtopic as a heading on a different page in their writing notebook. Then, research collected for each subtopic is placed on the page specific to the learning. This can be done using bullets or sticky notes. Although expensive, I prefer the sticky-note route. It allows the details to be easily manipulated/moved around and seem less daunting for students who are reluctant writers.

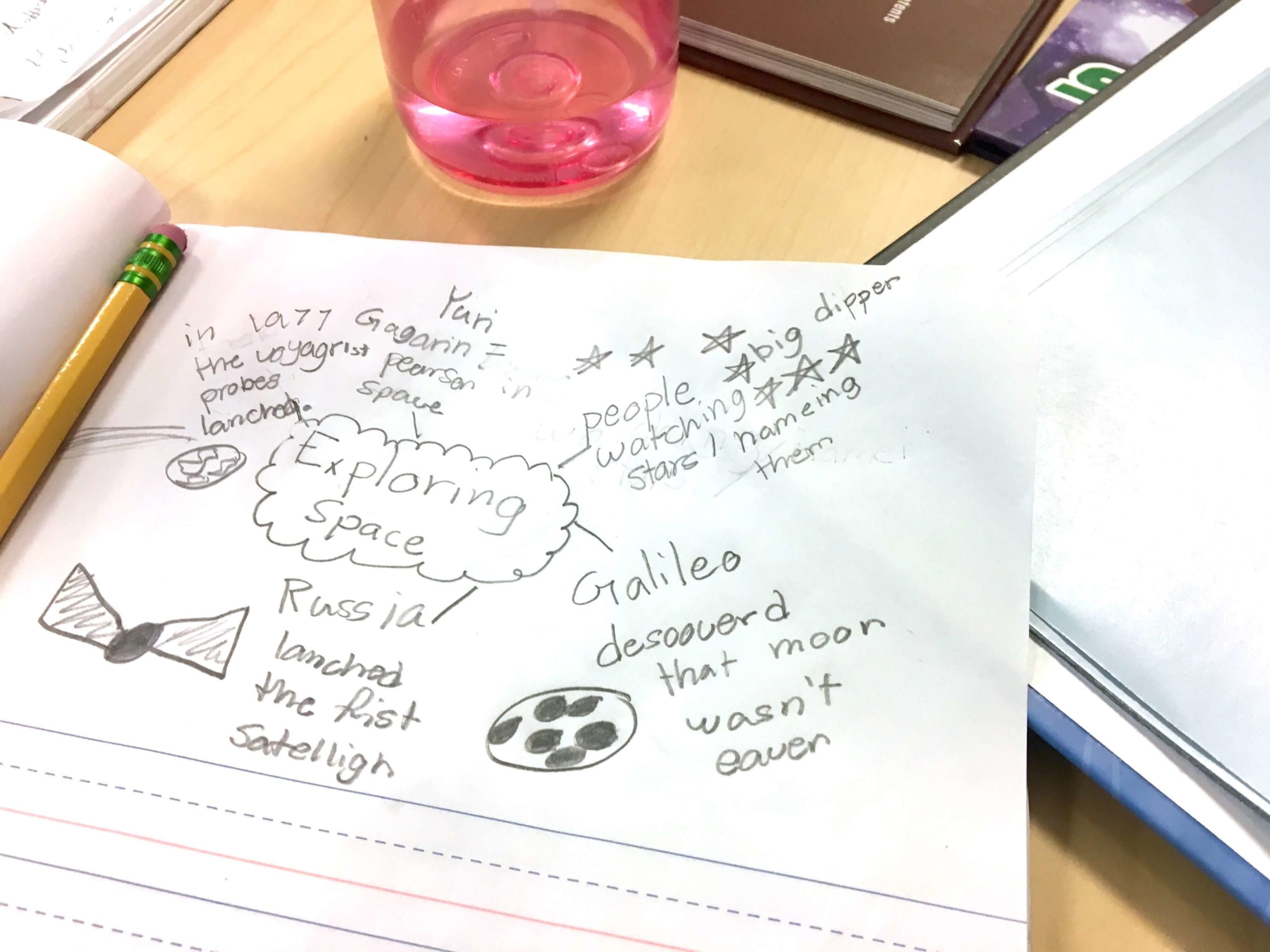

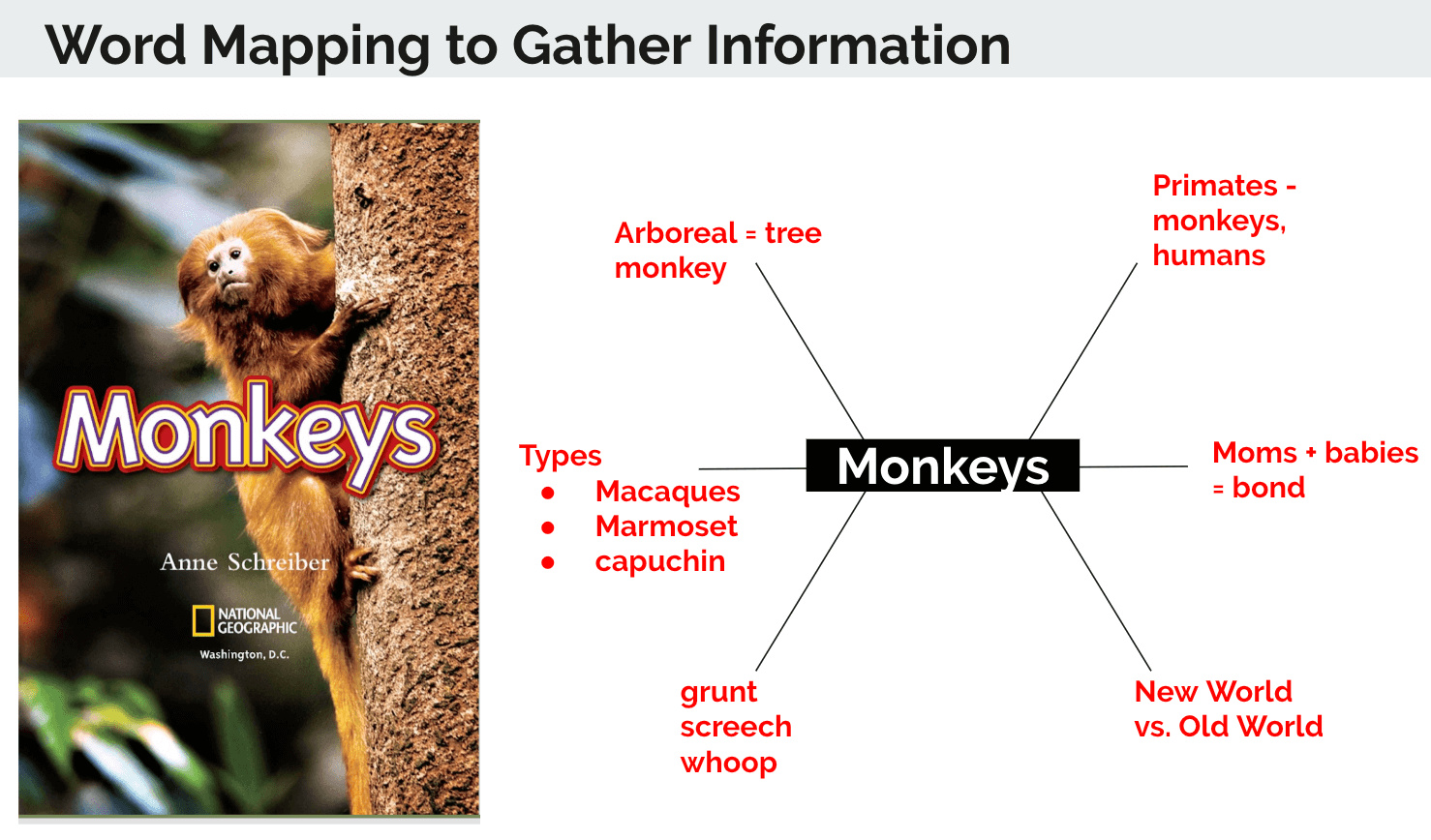

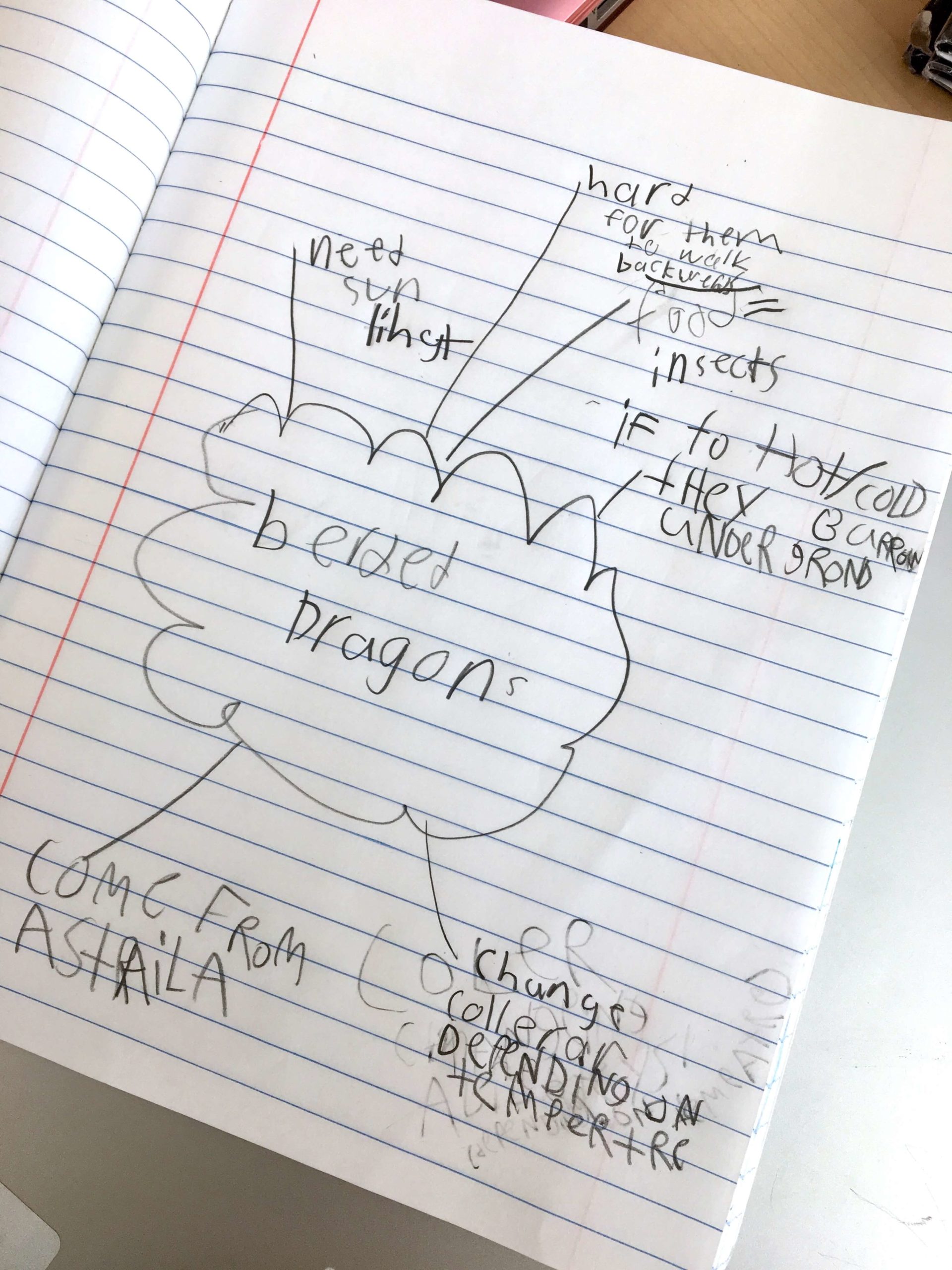

Concept Mapping

Additionally, concept mapping is very similar to creating subtopics. Ultimately, this strategy becomes a little nebulous. Often times I will introduce it before subtopics sometimes after. There is no hard and fast rule. If taught after subtopics, we will create concept maps with ALL the information and then, create subtopics into which to sort the information. If teaching after subtopics, we natural embed subtopics into our mind maps.

The student sample belows shows a general collection of information with some sketch noting. That’s okay! It is a signal to me, as the teacher, we may need more support in structuring our thinking or we may not be focused on a specific research question.

Question & Answer

Hands-down the question/answer strategy is THE most effective for helping students explore specific research questions and avoiding the “All About” book filled with lots of random facts.

To begin this strategy, we read an informational text aloud and identify a sentence or idea in the text that we want to learn more about. We write this sentence or details from the text on a sticky note and stick it at the top of a page in our writing journal. From there, we make a bulleted list of questions from that detail. What do we want to know more about? What would our reader want to know more about?

Now, as we read/listen/write, these become our research questions. This strategy is gold because it means students are driving the inquiry, we are looking at something specific, and the questions will determine which sources we need. Therefore, using multiple information sources become authentic.

We Have the Information…Now What?

Now that we have completed research on several different topics, questions, and/or questions, we are ready to publish and share our learning. The science or social studies unit our learning aligned with determine how the information is shared. Sometimes we use Google Slides, paragraphs , letters, and sometimes we’ll share our ideas in a speech.

Research in 1st and 2nd Grade is a tough task. There will be missteps – not so great mini-lessons, skipping of steps, moving too fast, hard-to-find-research topics – and that’s okay. All of these things help us, as teachers, and students grow. Research in the real-world is not perfect, and it shouldn’t be in our classrooms either.

So, my challenge to you – offer students real opportunities to learn and research without over scaffolding. Be brave in teaching students’ strategies that allow choice, flexibility, and curiosity to reign. You’ve got this, friends.

Related Posts

Reader Interactions

April 22, 2024 at 4:51 am

Thank you for providing a useful framework for using sketch notes as an information gathering tool, especially in the early stages of research before developing specific research questions. If you are also feeling free, you can try some online games like a small world cup .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.

Teaching Students How to Formulate Research Questions

When it comes to teaching students how to write a research paper, there is one area where students struggle: writing a guiding research question. Oftentimes, their research questions are either too vague or off-topic.

Teaching high school students how to formulate a research question is an important skill that will help students succeed not only on their research paper assignments but in other areas of their lives as well.

A well-formulated research question helps students focus their research, determine the relevance of the information they seek, and effectively communicate the purpose of their research to others. It is the starting point for teaching students how to write a research paper .

Here are some steps for teaching high school students how to formulate a research question:

- Start by introducing the concept of a research question. Explain that a research question is a specific question that a student aims to answer through research. It should be focused, clear, and specific, and should reflect the student’s interests and curiosity about a particular topic.

- Next, help students brainstorm potential research questions. Encourage them to think about topics that they are interested in and to consider what they would like to learn more about. Encourage them to be creative and to consider different angles on a topic. One thing I like to do is have students brainstorm on a T-chart: what they know about the subject and what they would like to know about the subject.

- Once students have identified a potential research question, help them refine it. Encourage them to make their question as specific as possible, and to consider the feasibility of answering it through research. For example, a general question like “What is the history of the American Revolution?” is far too open. Instead, it can be refined to a specific question like “How did the role of women in the American Revolution differ from their role in other major revolutions of the time period?”

- Finally, encourage students to test the validity of their research question. Have them consider whether their question is answerable through research, and whether it is relevant to their interests and the broader context of their academic or personal goals. If after a quick search students are not finding anything remotely close that answers their questions, they should go back and refine their research question.

Here are some examples of research questions that high school students might consider:

- How has the role of [topic] changed over the past 50 years?

- What are the effects of [topic] on [topic]?

- How did the [topic] impact the lives of [topic] in the [topic]?

- How have [topic] changed over the past century, and what has influenced those changes?

Remember, the goal of teaching high school students how to formulate a research question is to help them develop the critical thinking and problem-solving skills that are essential for success in academia and beyond. When students truly understand and grasp this skill, they gain far more knowledge than just the stepping stone for writing a great paper. By guiding students through the process of formulating a research question, you can help students become more confident, independent learners.

You might also be interested in the blog post about research paper topics for secondary EL A students.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Leave this field empty

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes