A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Use the guidelines below to learn about the practice of close reading.

When your teachers or professors ask you to analyze a literary text, they often look for something frequently called close reading. Close reading is deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form.

Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Literary analysis involves examining these components, which allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character’s daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like “tome” instead of “book”? In effect, you are putting the author’s choices under a microscope.

The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work.

Close reading sometimes feels like over-analyzing, but don’t worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you will sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. This guide imagines you are sitting down to read a text for the first time on your way to developing an argument about a text and writing a paper. To give one example of how to do this, we will read the poem “Design” by famous American poet Robert Frost and attend to four major components of literary texts: subject, form, word choice (diction), and theme.

If you want even more information about approaching poems specifically, take a look at our guide: How to Read a Poem .

As our guide to reading poetry suggests, have a pencil out when you read a text. Make notes in the margins, underline important words, place question marks where you are confused by something. Of course, if you are reading in a library book, you should keep all your notes on a separate piece of paper. If you are not making marks directly on, in, and beside the text, be sure to note line numbers or even quote portions of the text so you have enough context to remember what you found interesting.

Design I found a dimpled spider, fat and white, On a white heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth— Assorted characters of death and blight Mixed ready to begin the morning right, Like the ingredients of a witches’ broth— A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth, And dead wings carried like a paper kite. What had that flower to do with being white, The wayside blue and innocent heal-all? What brought the kindred spider to that height, Then steered the white moth thither in the night? What but design of darkness to appall?— If design govern in a thing so small.

The subject of a literary text is simply what the text is about. What is its plot? What is its most important topic? What image does it describe? It’s easy to think of novels and stories as having plots, but sometimes it helps to think of poetry as having a kind of plot as well. When you examine the subject of a text, you want to develop some preliminary ideas about the text and make sure you understand its major concerns before you dig deeper.

Observations

In “Design,” the speaker describes a scene: a white spider holding a moth on a white flower. The flower is a heal-all, the blooms of which are usually violet-blue. This heal-all is unusual. The speaker then poses a series of questions, asking why this heal-all is white instead of blue and how the spider and moth found this particular flower. How did this situation arise?

The speaker’s questions seem simple, but they are actually fairly nuanced. We can use them as a guide for our own as we go forward with our close reading.

- Furthering the speaker’s simple “how did this happen,” we might ask, is the scene in this poem a manufactured situation?

- The white moth and white spider each use the atypical white flower as camouflage in search of sanctuary and supper respectively. Did these flora and fauna come together for a purpose?

- Does the speaker have a stance about whether there is a purpose behind the scene? If so, what is it?

- How will other elements of the text relate to the unpleasantness and uncertainty in our first look at the poem’s subject?

After thinking about local questions, we have to zoom out. Ultimately, what is this text about?

Form is how a text is put together. When you look at a text, observe how the author has arranged it. If it is a novel, is it written in the first person? How is the novel divided? If it is a short story, why did the author choose to write short-form fiction instead of a novel or novella? Examining the form of a text can help you develop a starting set of questions in your reading, which then may guide further questions stemming from even closer attention to the specific words the author chooses. A little background research on form and what different forms can mean makes it easier to figure out why and how the author’s choices are important.

Most poems follow rules or principles of form; even free verse poems are marked by the author’s choices in line breaks, rhythm, and rhyme—even if none of these exists, which is a notable choice in itself. Here’s an example of thinking through these elements in “Design.”

In “Design,” Frost chooses an Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet form: fourteen lines in iambic pentameter consisting of an octave (a stanza of eight lines) and a sestet (a stanza of six lines). We will focus on rhyme scheme and stanza structure rather than meter for the purposes of this guide. A typical Italian sonnet has a specific rhyme scheme for the octave:

a b b a a b b a

There’s more variation in the sestet rhymes, but one of the more common schemes is

c d e c d e

Conventionally, the octave introduces a problem or question which the sestet then resolves. The point at which the sonnet goes from the problem/question to the resolution is called the volta, or turn. (Note that we are speaking only in generalities here; there is a great deal of variation.)

Frost uses the usual octave scheme with “-ite”/”-ight” (a) and “oth” (b) sounds: “white,” “moth,” “cloth,” “blight,” “right,” “broth,” “froth,” “kite.” However, his sestet follows an unusual scheme with “-ite”/”-ight” and “all” sounds:

a c a a c c

Now, we have a few questions with which we can start:

- Why use an Italian sonnet?

- Why use an unusual scheme in the sestet?

- What problem/question and resolution (if any) does Frost offer?

- What is the volta in this poem?

- In other words, what is the point?

Italian sonnets have a long tradition; many careful readers recognize the form and know what to expect from his octave, volta, and sestet. Frost seems to do something fairly standard in the octave in presenting a situation; however, the turn Frost makes is not to resolution, but to questions and uncertainty. A white spider sitting on a white flower has killed a white moth.

- How did these elements come together?

- Was the moth’s death random or by design?

- Is one worse than the other?

We can guess right away that Frost’s disruption of the usual purpose of the sestet has something to do with his disruption of its rhyme scheme. Looking even more closely at the text will help us refine our observations and guesses.

Word Choice, or Diction

Looking at the word choice of a text helps us “dig in” ever more deeply. If you are reading something longer, are there certain words that come up again and again? Are there words that stand out? While you are going through this process, it is best for you to assume that every word is important—again, you can decide whether something is really important later.

Even when you read prose, our guide for reading poetry offers good advice: read with a pencil and make notes. Mark the words that stand out, and perhaps write the questions you have in the margins or on a separate piece of paper. If you have ideas that may possibly answer your questions, write those down, too.

Let’s take a look at the first line of “Design”:

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white

The poem starts with something unpleasant: a spider. Then, as we look more closely at the adjectives describing the spider, we may see connotations of something that sounds unhealthy or unnatural. When we imagine spiders, we do not generally picture them dimpled and white; it is an uncommon and decidedly creepy image. There is dissonance between the spider and its descriptors, i.e., what is wrong with this picture? Already we have a question: what is going on with this spider?

We should look for additional clues further on in the text. The next two lines develop the image of the unusual, unpleasant-sounding spider:

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth—

Now we have a white flower (a heal-all, which usually has a violet-blue flower) and a white moth in addition to our white spider. Heal-alls have medicinal properties, as their name suggests, but this one seems to have a genetic mutation—perhaps like the spider? Does the mutation that changes the heal-all’s color also change its beneficial properties—could it be poisonous rather than curative? A white moth doesn’t seem remarkable, but it is “Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth,” or like manmade fabric that is artificially “rigid” rather than smooth and flowing like we imagine satin to be. We might think for a moment of a shroud or the lining of a coffin, but even that is awry, for neither should be stiff with death.

The first three lines of the poem’s octave introduce unpleasant natural images “of death and blight” (as the speaker puts it in line four). The flower and moth disrupt expectations: the heal-all is white instead of “blue and innocent,” and the moth is reduced to “rigid satin cloth” or “dead wings carried like a paper kite.” We might expect a spider to be unpleasant and deadly; the poem’s spider also has an unusual and unhealthy appearance.

- The focus on whiteness in these lines has more to do with death than purity—can we understand that whiteness as being corpse-like rather than virtuous?

Well before the volta, Frost makes a “turn” away from nature as a retreat and haven; instead, he unearths its inherent dangers, making nature menacing. From three lines alone, we have a number of questions:

- Will whiteness play a role in the rest of the poem?

- How does “design”—an arrangement of these circumstances—fit with a scene of death?

- What other juxtapositions might we encounter?

These disruptions and dissonances recollect Frost’s alteration to the standard Italian sonnet form: finding the ways and places in which form and word choice go together will help us begin to unravel some larger concepts the poem itself addresses.

Put simply, themes are major ideas in a text. Many texts, especially longer forms like novels and plays, have multiple themes. That’s good news when you are close reading because it means there are many different ways you can think through the questions you develop.

So far in our reading of “Design,” our questions revolve around disruption: disruption of form, disruption of expectations in the description of certain images. Discovering a concept or idea that links multiple questions or observations you have made is the beginning of a discovery of theme.

What is happening with disruption in “Design”? What point is Frost making? Observations about other elements in the text help you address the idea of disruption in more depth. Here is where we look back at the work we have already done: What is the text about? What is notable about the form, and how does it support or undermine what the words say? Does the specific language of the text highlight, or redirect, certain ideas?

In this example, we are looking to determine what kind(s) of disruption the poem contains or describes. Rather than “disruption,” we want to see what kind of disruption, or whether indeed Frost uses disruptions in form and language to communicate something opposite: design.

Sample Analysis

After you make notes, formulate questions, and set tentative hypotheses, you must analyze the subject of your close reading. Literary analysis is another process of reading (and writing!) that allows you to make a claim about the text. It is also the point at which you turn a critical eye to your earlier questions and observations to find the most compelling points, discarding the ones that are a “stretch.” By “stretch,” we mean that we must discard points that are fascinating but have no clear connection to the text as a whole. (We recommend a separate document for recording the brilliant ideas that don’t quite fit this time around.)

Here follows an excerpt from a brief analysis of “Design” based on the close reading above. This example focuses on some lines in great detail in order to unpack the meaning and significance of the poem’s language. By commenting on the different elements of close reading we have discussed, it takes the results of our close reading to offer one particular way into the text. (In case you were thinking about using this sample as your own, be warned: it has no thesis and it is easily discoverable on the web. Plus it doesn’t have a title.)

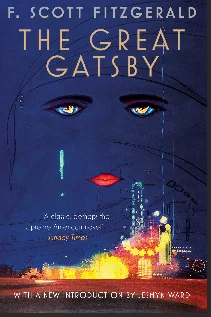

Frost’s speaker brews unlikely associations in the first stanza of the poem. The “Assorted characters of death and blight / Mixed ready to begin the morning right” make of the grotesque scene an equally grotesque mockery of a breakfast cereal (4–5). These lines are almost singsong in meter and it is easy to imagine them set to a radio jingle. A pun on “right”/”rite” slides the “characters of death and blight” into their expected concoction: a “witches’ broth” (6). These juxtapositions—a healthy breakfast that is also a potion for dark magic—are borne out when our “fat and white” spider becomes “a snow-drop”—an early spring flower associated with renewal—and the moth as “dead wings carried like a paper kite” (1, 7, 8). Like the mutant heal-all that hosts the moth’s death, the spider becomes a deadly flower; the harmless moth becomes a child’s toy, but as “dead wings,” more like a puppet made of a skull. The volta offers no resolution for our unsettled expectations. Having observed the scene and detailed its elements in all their unpleasantness, the speaker turns to questions rather than answers. How did “The wayside blue and innocent heal-all” end up white and bleached like a bone (10)? How did its “kindred spider” find the white flower, which was its perfect hiding place (11)? Was the moth, then, also searching for camouflage, only to meet its end? Using another question as a disguise, the speaker offers a hypothesis: “What but design of darkness to appall?” (13). This question sounds rhetorical, as though the only reason for such an unlikely combination of flora and fauna is some “design of darkness.” Some force, the speaker suggests, assembled the white spider, flower, and moth to snuff out the moth’s life. Such a design appalls, or horrifies. We might also consider the speaker asking what other force but dark design could use something as simple as appalling in its other sense (making pale or white) to effect death. However, the poem does not close with a question, but with a statement. The speaker’s “If design govern in a thing so small” establishes a condition for the octave’s questions after the fact (14). There is no point in considering the dark design that brought together “assorted characters of death and blight” if such an event is too minor, too physically small to be the work of some force unknown. Ending on an “if” clause has the effect of rendering the poem still more uncertain in its conclusions: not only are we faced with unanswered questions, we are now not even sure those questions are valid in the first place. Behind the speaker and the disturbing scene, we have Frost and his defiance of our expectations for a Petrarchan sonnet. Like whatever designer may have altered the flower and attracted the spider to kill the moth, the poet built his poem “wrong” with a purpose in mind. Design surely governs in a poem, however small; does Frost also have a dark design? Can we compare a scene in nature to a carefully constructed sonnet?

A Note on Organization

Your goal in a paper about literature is to communicate your best and most interesting ideas to your reader. Depending on the type of paper you have been assigned, your ideas may need to be organized in service of a thesis to which everything should link back. It is best to ask your instructor about the expectations for your paper.

Knowing how to organize these papers can be tricky, in part because there is no single right answer—only more and less effective answers. You may decide to organize your paper thematically, or by tackling each idea sequentially; you may choose to order your ideas by their importance to your argument or to the poem. If you are comparing and contrasting two texts, you might work thematically or by addressing first one text and then the other. One way to approach a text may be to start with the beginning of the novel, story, play, or poem, and work your way toward its end. For example, here is the rough structure of the example above: The author of the sample decided to use the poem itself as an organizational guide, at least for this part of the analysis.

- A paragraph about the octave.

- A paragraph about the volta.

- A paragraph about the penultimate line (13).

- A paragraph about the final line (14).

- A paragraph addressing form that suggests a transition to the next section of the paper.

You will have to decide for yourself the best way to communicate your ideas to your reader. Is it easier to follow your points when you write about each part of the text in detail before moving on? Or is your work clearer when you work through each big idea—the significance of whiteness, the effect of an altered sonnet form, and so on—sequentially?

We suggest you write your paper however is easiest for you then move things around during revision if you need to.

Further Reading

If you really want to master the practice of reading and writing about literature, we recommend Sylvan Barnet and William E. Cain’s wonderful book, A Short Guide to Writing about Literature . Barnet and Cain offer not only definitions and descriptions of processes, but examples of explications and analyses, as well as checklists for you, the author of the paper. The Short Guide is certainly not the only available reference for writing about literature, but it is an excellent guide and reminder for new writers and veterans alike.

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

How to Do a Close Reading

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Close Reading Fundamentals

How to choose a passage to close-read, how to approach a close reading, how to annotate a passage, how to improve your close reading, how to practice close reading, how to incorporate close readings into an essay, how to teach close reading, additional resources for advanced students.

Close reading engages with the formal properties of a text—its literary devices, language, structure, and style. Popularized in the mid-twentieth century, this way of reading allows you to interpret a text without outside information such as historical context, author biography, philosophy, or political ideology. It also requires you to put aside your affective (that is, personal and emotional) response to the text, focusing instead on objective study. Why close-read a text? Doing so will increase your understanding of how a piece of writing works, as well as what it means. Perhaps most importantly, close reading can help you develop and support an essay argument. In this guide, you'll learn more about what close reading entails and find strategies for producing precise, creative close readings. We've included a section with resources for teachers, along with a final section with further reading for advanced students.

You might compare close reading to wringing out a wet towel, in which you twist the material repeatedly until you have extracted as much liquid as possible. When you close-read, you'll return to a short passage several times in order to note as many details about its form and content as possible. Use the links below to learn more about close reading's place in literary history and in the classroom.

"Close Reading" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's relatively short introduction to close reading contains sections on background, examples, and how to teach close reading. You can also click the links on this page to learn more about the literary critics who pioneered the method.

"Close Reading: A Brief Note" (Literariness.org)

This article provides a condensed discussion of what close reading is, how it works, and how it is different from other ways of reading a literary text.

"What Close Reading Actually Means" ( TeachThought )

In this article by an Ed.D., you'll learn what close reading "really means" in the classroom today—a meaning that has shifted significantly from its original place in 20th century literary criticism.

"Close Reading" (Univ. of Washington)

This hand-out from a college writing course defines close reading, suggests why we close-read, and offers tips for close reading successfully, including focusing on language, audience, and scope.

"Glossary Entry on New Criticism" (Poetry Foundation)

If you'd like to read a short introduction to the school of thought that gave rise to close reading, this is the place to go. Poetry Foundation's entry on New Criticism is concise and accessible.

"New Criticism" (Washington State Univ.)

This webpage from a college writing course offers another brief explanation of close reading in relation to New Criticism. It provides some key questions to help you think like a New Critic.

When choosing a passage to close-read, you'll want to look for relatively short bits of text that are rich in detail. The resources below offer more tips and tricks for selecting passages, along with links to pre-selected passages you can print for use at home or in the classroom.

"How to Choose the Perfect Passage for Close Reading" ( We Are Teachers )

This post from a former special education teacher describes six characteristics you might look for when selecting a close reading passage from a novel: beginnings, pivotal plot points, character changes, high-density passages, "Q&A" passages, and "aesthetic" passages.

"Close Reading Passages" (Reading Sage)

Reading Sage provides links to close reading passages you can use as is; alternatively, you could also use them as models for selecting your own passages. The page is divided into sections geared toward elementary, middle school, and early high school students.

"Close Reading" (Univ. of Guelph)

The University of Guelph's guide to close reading contains a short section on how to "Select a Passage." The author suggests that you choose a brief passage.

"Close Reading Advice" (Prezi)

This Prezi was created by an AP English teacher. The opening section on passage selection suggests choosing "thick paragraphs" filled with "figurative language and rich details or description."

Now that you know how to select a passage to analyze, you'll need to familiarize yourself with the textual qualities you should look for when reading. Whether you're approaching a poem, a novel, or a magazine article, details on the level of language (literary devices) and form (formal features) convey meaning. Understanding how a text communicates will help you understand what it is communicating. The links in this section will familiarize you with the tools you need to start a close reading.

Literary Devices

"Literary Devices and Terms" (LitCharts)

LitCharts' dedicated page covers 130+ literary devices. Also known as "rhetorical devices," "figures of speech," or "elements of style," these linguistic constructions are the building blocks of literature. Some of the most common include simile , metaphor , alliteration , and onomatopoeia ; browse the links on LitCharts to learn about many more.

"Rhetorical Device" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's page on rhetorical devices defines the term in relation to the ancient art of "rhetoric" or persuasive speaking. At the bottom of the page, you'll find links to several online handbooks and lists of rhetorical devices.

"15 Must Know Rhetorical Terms for AP English Literature" ( Albert )

The Albert blog offers this list of 15 rhetorical devices that high school English students should know how to define and spot in a literary text; though geared toward the Advanced Placement exam, its tips are widely applicable.

"The 55 AP Language and Composition Terms You Must Know" (PrepScholar)

This blog post lists 55 terms high school students should learn how to recognize and define for the Advanced Placement exam in English Literature.

Formal Features

In LitCharts' bank of literary devices and terms, you'll also find resources to describe a text's structure and overall character. Some of the most important of these are rhyme , meter , and tone ; browse the page to find more.

"Rhythm" ( Encyclopedia Britannica )

This encyclopedia entry on rhythm and meter offers an in-depth definition of the two most fundamental aspects of poetry.

"How to Analyze Syntax for AP English Literature" ( Albert)

The Albert blog will help you understand what "syntax" is, making a case for why you should pay attention to sentence structure when analyzing a literary text.

"Grammar Basics: Sentence Parts and Sentence Structures" ( ThoughtCo )

This article provides a meticulous overview of the components of a sentence. It's useful if you need to review your parts of speech or if you need to be able to identify things like prepositional phrases.

"Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice" (Wheaton College)

Wheaton College's Writing Center offers this clear, concise discussion of several important formal features. Although it's designed to help essay writers, it will also help you understand and spot these stylistic features in others' work.

Now that you know what rhetorical devices, formal features, and other details to look for, you're ready to find them in a text. For this purpose, it is crucial to annotate (write notes) as you read and re-read. Each time you return to the text, you'll likely notice something new; these observations will form the basis of your close reading. The resources in this section offer some concrete strategies for annotating literary texts.

"How to Annotate a Text" (LitCharts)

Begin by consulting our How to Annotate a Text guide. This collection of links and resources is helpful for short passages (that is, those for close reading) as well as longer works, like whole novels or poems.

"Annotation Guide" (Covington Catholic High School)

This hand-out from a high school teacher will help you understand why we annotate, and how to annotate a text successfully. You might choose to incorporate some of the interpretive notes and symbols suggested here.

"Annotating Literature" (New Canaan Public Schools)

This one-page, introductory resource provides a list of 10 items you should look for when reading a text, including attitude and theme.

"Purposeful Annotation" (Dave Stuart Jr.)

This article from a high school teacher's blog describes the author's top close reading strategy: purposeful annotation. In fact, this teacher more or less equates close reading with annotation.

Looking for ways to improve your close reading? The articles, guides, and videos in this section will expose you to various methods of close reading, as well as practice exercises. No two people read exactly the same way. Whatever your level of expertise, it can be useful to broaden your skill set by testing the techniques suggested by the resources below.

"How to Do a Close Reading" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, part of Harvard's comprehensive "Strategies for Essay Writing Guide," describes three steps to a successful close reading. You will want to return to this resource when incorporating your close reading into an essay.

"A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis" (Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center)

Working through this guide from another college writing center will help you move through the process of close reading a text. You'll find a sample analysis of Robert Frost's "Design" at the end.

"How to Do a Close Reading of a Text" (YouTube)

This four-minute video from the "Literacy and Math Ideas" channel offers a number of helpful tips for reading a text closely in accordance with Common Core standards.

"Poetry: Close Reading" (Purdue OWL)

Short, dense poems are a natural fit for the close reading approach. This page from the Purdue Online Writing Lab takes you step-by-step through an analysis of Shakespeare's Sonnet 116.

"Steps for Close Reading or Explication de Texte" ( The Literary Link )

This page, which mentions close reading's close relationship to the French formalist method of "explication de texte," shares "12 Steps to Literary Awareness."

You can practice your close reading skills by reading, re-reading and annotating any brief passage of text. The resources below will get you started by offering pre-selected passages and questions to guide your reading. You'll find links to resources that are designed for students of all levels, from elementary school through college.

"Notes on Close Reading" (MIT Open Courseware)

This resource describes steps you can work through when close reading, providing a passage from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein for you to test your skills.

"Close Reading Practice Worksheets" (Gillian Duff's English Resources)

Here, you'll find 10 close reading-centered worksheets you can download and print. The "higher-close-reading-formula" link at the bottom of the page provides a chart with even more steps and strategies for close reading.

"Close Reading Activities" (Education World)

The four activities described on this page are best suited to elementary and middle school students. Under each heading is a link to handouts or detailed descriptions of the activity.

"Close Reading Practice Passages: High School" (Varsity Tutors)

This webpage from Varsity Tutors contains over a dozen links to close reading passages and exercises, including several resources that focus on close-reading satire.

"Benjamin Franklin's Satire of Witch Hunting" (America in Class)

This page contains both a "teacher's guide" and "student version" to interpreting Benjamin Franklin's satire of a witch trial. The thirteen close reading questions on the right side of the page will help you analyze the text thoroughly.

Whether you're writing a research paper or an essay, close reading can help you build an argument. Careful analysis of your primary texts allows you to draw out meanings you want to emphasize, thereby supporting your central claim. The resources in this section introduce you to strategies suited to various common writing assignments.

"How to Write a Research Paper" (LitCharts)

The resources in this guide will help you learn to formulate a thesis, organize evidence, write an outline, and draft a research paper, one of the two most common assignments in which you might incorporate close reading.

"How to Write an Essay" (LitCharts)

In this guide, you'll learn how to plan, draft, and revise an essay, whether for the classroom or as a take-home assignment. Close reading goes hand in hand with the brainstorming and drafting processes for essay writing.

"Guide to the Close Reading Essay" (Univ. of Warwick)

This guide was designed for undergraduates, and assumes prior knowledge of formal features and rhetorical devices one might find in a poem. High schoolers will find it useful after addressing the "elements of a close reading" section above.

"Beginning the Academic Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Harvard's guide discusses the broader category of the "academic essay." Here, the author assumes that your essay's close readings will be accompanied by context and evidence from secondary sources.

A Short Guide to Writing About Literature (Amazon)

Sylvan Barnet and William E. Cain emphasize that writing is a process. In their book, you'll find definitions of important literary terms, examples of successful explications of literary texts, and checklists for essay writers.

Due in part to the Common Core's emphasis on close reading skills, resources for teaching students how to close-read abound. Here, you'll find a wealth of information on how and why we teach students to close-read texts. The first section includes links to activities, exercises, and complete lesson plans. The second section offers background material on the method, along with strategies for implementing close reading in the classroom.

Lesson Plans and Activities

"Four Lessons for Introducing the Fundamental Steps of Close Reading" (Corwin)

Here, Corwin has made the second chapter of Nancy Akhavan's The Nonfiction Now Lesson Bank, Grades 4 – 8 available online. You'll find four sample lessons to use in the elementary or middle school classroom

"Sonic Patterns: Exploring Poetic Techniques Through Close Reading" ( ReadWriteThink )

This lesson plan for high school students includes material for five 50-minute sessions on sonic patterns (including consonance, assonance, and alliteration). The literary text at hand is Robert Hayden's "Those Winter Sundays."

"Close Reading of a Short Text: Complete Lesson" (McGraw Hill via YouTube)

This eight-minute video describes a complete lesson in which a teacher models close reading of a short text and offers guiding questions.

"Close Reading Model Lessons" (Achieve the Core)

These three model lessons on close reading will help you determine what makes a text "appropriately complex" for the grade level you teach.

Close Reading Bundle (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This top-rated bundle of close reading resources was designed for the middle school classroom. It contains over 150 pages of worksheets, complete lesson plans, and literacy center ideas.

"10 Intriguing Photos to Teach Close Reading and Visual Thinking Skills" ( The New York Times )

The New York Times' s Learning Network has gathered 10 photos from the "What's Going on in This Picture" series that teachers can use to help students develop analytical and visual thinking skills.

"The Close Reading Essay" (Brandeis Univ.)

Brandeis University's writing program offers this detailed set of guidelines and goals you might use when assigning a close reading essay.

Close Reading Resources (Varsity Tutors)

Varsity Tutors has compiled a list of over twenty links to lesson plans, strategies, and activities for teaching elementary, middle school, and high school students to close read.

Background Material and Teaching Strategies

Falling in Love with Close Reading (Amazon)

Christopher Lehman and Kate Roberts aim to show how close reading can be "rigorous, meaningful, and joyous." It offers a three-step "close reading ritual" and engaging lesson plans.

Notice & Note: Strategies for Close Reading (Amazon)

Kylene Beers (a former Senior Reading Researcher at Yale) and Robert E. Probst (a Professor Emeritus of English Education) introduce six "signposts" readers can use to detect significant moments in a work of literature.

"How to Do a Close Reading" (YouTube)

TeachLikeThis offers this four-minute video on teaching students to close-read by looking at a text's language, narrative, syntax, and context.

"Strategy Guide: Close Reading of a Literary Text" ( ReadWriteThink )

This guide for middle school and high school teachers will help you choose texts that are appropriately complex for the grade level you teach, and offers strategies for planning engaging lessons.

"Close Reading Steps for Success" (Appletastic Learning)

Shelly Rees, a teacher with over 20 years of experience, introduces six helpful steps you can use to help your students engage with challenging reading passages. The article is geared toward elementary and middle school teachers.

"4 Steps to Boost Students' Close Reading Skills" ( Amplify )

Doug Fisher, a professor of educational leadership, suggests using these four steps to help students at any grade level learn how to close read.

Like most tools of literary analysis, close reading has a complex history. It's not necessary to understand the theoretical underpinnings of close reading in order to use this tool. For advanced high school students and college students who ask "why close-read," though, the resources below will serve as useful starting points for discussion.

"Discipline and Parse: The Politics of Close Reading" ( Los Angeles Review of Books )

This book review by a well-known English professor at Columbia provides an engaging, anecdotal introduction to close reading's place in literary history. Robbins points to some of the method's shortcomings, but also elegantly defends it.

"Intentional Fallacy" ( Encyclopedia Britannica )

The literary critics who developed close reading cautioned against judging a text based on the author's intention. This encyclopedia entry offers an expanded definition of this way of reading, called the "intentional fallacy."

"Seven Types of Ambiguity" (Wikipedia)

This Wikipedia article will introduce you to William Empson's Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), one of the foundational texts of New Criticism, the school of thought that theorized close reading.

"What is Distant Reading" ( The New York Times)

This article makes it clear that "close reading" isn't the only way to analyze literary texts. It offers a brief introduction to the "distant reading" method of computational criticism pioneered by Franco Moretti in recent years.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1996 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 42,161 quotes across 1996 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to do a close reading essay [Updated 2024]

Close reading refers to the process of interpreting a literary work’s meaning by analyzing both its form and content. In this post, we provide you with strategies for close reading that you can apply to your next assignment or analysis.

What is a close reading?

Close reading involves paying attention to a literary work’s language, style, and overall meaning. It includes looking for patterns, repetitions, oddities, and other significant features of a text. Your goal should be to reveal subtleties and complexities beyond an initial reading.

The primary difference between simply reading a work and doing a close reading is that, in the latter, you approach the text as a kind of detective.

When you’re doing a close reading, a literary work becomes a puzzle. And, as a reader, your job is to pull all the pieces together—both what the text says and how it says it.

How do you do a close reading?

Typically, a close reading focuses on a small passage or section of a literary work. Although you should always consider how the selection you’re analyzing fits into the work as a whole, it’s generally not necessary to include lengthy summaries or overviews in a close reading.

There are several aspects of the text to consider in a close reading:

- Literal Content: Even though a close reading should go beyond an analysis of a text’s literal content, every reading should start there. You need to have a firm grasp of the foundational content of a passage before you can analyze it closely. Use the common journalistic questions (Who? What? When? Where? Why?) to establish the basics like plot, character, and setting.

- Tone: What is the tone of the passage you’re examining? How does the tone influence the entire passage? Is it serious, comic, ironic, or something else?

- Characterization: What do you learn about specific characters from the passage? Who is the narrator or speaker? Watch out for language that reveals the motives and feelings of particular characters.

- Structure: What kind of structure does the work utilize? If it’s a poem, is it written in free or blank verse? If you’re working with a novel, does the structure deviate from certain conventions, like straightforward plot or realism? Does the form contribute to the overall meaning?

- Figurative Language: Examine the passage carefully for similes, metaphors, and other types of figurative language. Are there repetitions of certain figures or patterns of opposition? Do certain words or phrases stand in for larger issues?

- Diction: Diction means word choice. You should look up any words that you don’t know in a dictionary and pay attention to the meanings and etymology of words. Never assume that you know a word’s meaning at first glance. Why might the author choose certain words over others?

- Style and Sound: Pay attention to the work’s style. Does the text utilize parallelism? Are there any instances of alliteration or other types of poetic sound? How do these stylistic features contribute to the passage’s overall meaning?

- Context: Consider how the passage you’re reading fits into the work as a whole. Also, does the text refer to historical or cultural information from the world outside of the text? Does the text reference other literary works?

Once you’ve considered the above features of the passage, reflect on its relationship to the work’s larger themes, ideas, and actions. In the end, a close reading allows you to expand your understanding of a text.

Close reading example

Let’s take a look at how this technique works by examining two stanzas from Lorine Niedecker’s poem, “ I rose from marsh mud ”:

I rose from marsh mud, algae, equisetum, willows, sweet green, noisy birds and frogs to see her wed in the rich rich silence of the church, the little white slave-girl in her diamond fronds.

First, we need to consider the stanzas’ literal content. In this case, the poem is about attending a wedding. Next, we should take note of the poem’s form: four-line stanzas, written in free verse.

From there, we need to look more closely at individual words and phrases. For instance, the first stanza discusses how the speaker “rose from marsh mud” and then lists items like “algae, equisetum, willows” and “sweet green,” all of which are plants. Could the speaker have been gardening before attending the wedding?

Now, juxtapose the first stanza with the second: the speaker leaves the natural world of mud and greenness for the “rich/ rich silence of the church.” Note the repetition of the word, “rich,” and how the poem goes on to describe the “little white slave-girl/ in her diamond fronds,” the necessarily “rich” jewelry that the bride wears at her wedding.

Niedecker’s description of the diamond jewelry as “fronds” refers back to the natural world of plants that the speaker left behind. Note also the similarities in sound between the “frogs” of the first stanza and the “fronds” of the second.

We might conclude from a comparison of the two stanzas that, while the “marsh mud” might be full of “noisy/ birds and frogs,” it’s a far better place to be than the “rich/rich silence of the church.”

Ultimately, even a short close reading of Niedecker’s poem reveals layers of meaning that enhance our understanding of the work’s overall message.

How to write a close reading essay

Getting started.

Before you can write your close reading essay, you need to read the text that you plan to examine at least twice (but often more than that). Follow the above guidelines to break down your close reading into multiple parts.

Once you’ve read the text closely and made notes, you can then create a short outline for your essay. Determine how you want to approach to structure of your essay and keep in mind any specific requirements that your instructor may have for the assignment.

Structure and organization

Some close reading essays will simply analyze the text’s form and content without making a specific argument about the text. Other times, your instructor might want you to use a close reading to support an argument. In these cases, you’ll need to include a thesis statement in the introduction to your close reading essay.

You’ll organize your essay using the standard essay format. This includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Most of your close reading will be in the body paragraphs.

Formatting and length

The formatting of your close reading essay will depend on what type of citation style that your assignment requires. If you’re writing a close reading for a composition or literature class , you’ll most likely use MLA or Chicago style.

The length of your essay will vary depending on your assignment guidelines and the length and complexity of the text that you’re analyzing. If your close reading is part of a longer paper, then it may only take up a few paragraphs.

Citations and bibliography

Since you will be quoting directly from the text in your close reading essay, you will need to have in-text, parenthetical citations for each quote. You will also need to include a full bibliographic reference for the text you’re analyzing in a bibliography or works cited page.

To save time, use a credible citation generator like BibGuru to create your in-text and bibliographic citations. You can also use our citation guides on MLA and Chicago to determine what you need to include in your citations.

Frequently Asked Questions about how to do a close reading

A successful close reading pays attention to both the form and content of a literary work. This includes: literal content, tone, characterization, structure, figurative language, diction, sound, style, and context.

A close reading essay is a paper that analyzes a text or a portion of a text. It considers both the form and content of the text. The specific format of your close reading essay will depend on your assignment guidelines.

Skimming and close reading are opposite approaches. Skimming involves scanning a text superficially in order to glean the most important points, while close reading means analyzing the details of a text’s language, style, and overall form.

You might begin a close reading by providing some context about the passage’s significance to the work as a whole. You could also briefly summarize the literal content of the section that you’re examining.

The length of your essay will vary depending on your assignment guidelines and the length and complexity of the text that you’re analyzing.

Make your life easier with our productivity and writing resources.

For students and teachers.

- Utility Menu

ef0807c43085bac34d8a275e3ff004ed

Classicswrites, a guide to research and writing in the field of classics.

- Harvard Classics

- HarvardWrites

Close Reading

Close reading as analysis.

Close reading is the technique of carefully analyzing a passage’s language, content, structure, and patterns in order to understand what a passage means, what it suggests, and how it connects to the larger work. A close reading delves into what a passage means beyond a superficial level, then links what that passage suggests outward to its broader context. One goal of close reading is to help readers to see facets of the text that they may not have noticed before. To this end, close reading entails “reading out of” a text rather than “reading into” it. Let the text lead, and listen to it.

The goal of close reading is to notice, describe, and interpret details of the text that are already there, rather than to impose your own point of view. As a general rule of thumb, every claim you make should be directly supported by evidence in the text. As the name suggests this technique is best applied to a specific passage or passages rather than a longer piece, almost like a case study.

Use close reading to learn:

- what the passage says

- what the passage implies

- how the passage connects to its context

Why Close Reading?

Close reading is a fundamental skill for the analysis of any sort of text or discourse, whether it is literary, political, or commercial. It enables you to analyze how a text functions, and it helps you to understand a text’s explicit and implicit goals. The structure, vocabulary, language, imagery, and metaphors used in a text are all crucial to the way it achieves its purpose, and they are therefore all targets for close reading. Practicing close reading will train you to be an intelligent and critical reader of all kinds of writing, from political speeches to television advertisements and from popular novels to classic works of literature.

Wondering how to do a close reading? Click on our Where to Begin section to find out more!

- Where to Begin and Strategies

- Tips and Tricks

Email: [email protected] Phone: 650-430-8087 (text or call)

- Apr 9, 2023

Close-Reading Strategies: The Ultimate Guide to Close Reading

Close reading helps you not only read a text, but analyze it. The process of close reading teaches you to approach a text actively, considering the text’s purpose, how the author chose to present it, and how these decisions impact the text.

The close reading strategy improves your reading comprehension, your analysis, and your writing. Close reading will help you write essays and perform well on standardized tests like the SAT Reading Section . Any age group can practice close reading, and it works with any text.

This article will outline everything you need to know about close reading, including what it is, why it's important, how to do a close reading, and 5 strategies to improve your close reading abilities.

What is close reading?

Close reading is a reading method that examines not only the text’s content but how the author’s rhetorical, literary, and structural decisions help develop it to achieve a purpose.

No matter the text genre–narrative, informational, argumentative, poetry, or editorial–the author uses language to achieve some purpose: to inform, convince, entertain the audience, or a combination. In every text, the author utilizes a variety of rhetorical and literary strategies, or devices, to achieve these effects on the audience.

Common literary strategies or devices that impact every text:

Diction: Word choice

Syntax: Sentence structure

Tone: Emotion of the words used

Conflict: Problems, issues, or disagreements within or related to the text

Structure: The order of the words, sentences, paragraphs, and ideas

Point of view: The speaker’s perspective on the events or subject matter

Genre: The category or “type” of text–fiction, science-fiction, scientific article, etc.

Imagery: The sensory or visual language the author uses to describe the subject, characters, setting, etc.

Close reading observes how the author uses these strategies to develop the text, create an intended effect upon the reader, and build a central message or main idea.

Why is close reading important?

Close reading is important because it helps you comprehend the text, develop deeper ideas about its meaning, and write and talk about the text with more sophistication. When you consider not just what the text says, but how and why the author constructs it that way, you move beyond surface-level reading into analysis.

Close reading allows you to notice details, language, and connections that you may have previously overlooked. These observations create insights about the text, leading to richer class discussions, better essays, and more joy while reading. Observing an author’s strategies also improves your writing, as you gradually begin to emulate the strategies you notice.

How do you do a close reading?

Do a close reading by selecting a text passage, closely observing the writing style and structure while you read, noticing the author's language choices, underlining and annotating your observations, and asking questions about the text.

General Close-Reading Process:

Select a text passage: Pick a piece of text or passage that you want to analyze. The sweet spot usually lies between roughly one and three paragraphs. Songs and poems also work well for close reading.

Notice the writing style: As you read, ask yourself “What stands out to me about this author’s style? What patterns, words, and choices do I notice?” Pay attention to the emotions you feel as you read, identifying what in the text triggers that response.

Observe the structure: Notice how the author orders words, sentences, lines, and paragraphs. Consider how this order builds an image or idea about the text’s subject. Ask yourself, “How does this structure develop my understanding of the subject?”

Notice language choices: The author selected particular words to build a tone, evoke images in the reader’s mind, create a nuanced argument, or have some other effect on the reader. Note powerful or significant diction–word choice–and consider the purpose it serves, or how it develops any of the devices listed above, such as tone or imagery.

Underline: Have a pencil while you read and–if you’re allowed to mark the paper–underline any observations you make. Underline any of the devices listed above, anything that has an effect on you, or anything you enjoy. There’s no right or wrong way to underline a text, so underline whatever catches your interest.

Annotate: Record your thoughts and observations as you read, by writing in the margins, on a separate sheet of paper, or using an assigned annotation format. Feel free to note questions, individual words, literary devices, or anything you notice.

Ask questions: Along with the annotation ideas listed above, formulate questions and write them down while you read. Generally, the best questions begin with how or why . For example, “Why did the author use this word?” or “How does this detail affect the reader?”

5 Close Reading Strategies to Improve Analysis and Comprehension

Here are my 5 favorite strategies to improve your close reading, analysis, and reading comprehension:

Generate a purpose question (PQ)

Annotate with your PQ in mind

Track the 5 Ws

Notice the conflict

Identify the tone

Generate a Purpose Question

A purpose question (PQ) is a question you pose before reading a text to help you read actively. You can create a PQ for a text of any genre or length–a novel, a short story, a poem, a passage, or an informational text–and there is no right or wrong way to create a PQ.

To create a purpose question, consider any pre-reading context you have:

Text images

School assignment guidelines

Any task you’re expected to complete when you finish reading

Examine the text’s title to guess what the text is about, then formulate an open-ended question that relates to the text, what it might say, and what might be important. As you read, seek and underline information that relates to your PQ and helps you answer it. By the time you finish reading, you should be able to answer your PQ.

Generally, the best open-ended questions begin with how or why .

Your PQ will sometimes simply repurpose the text’s title into a question, like these examples:

Text TitleExample PQ “A Good Man is Hard to Find?” (fiction)Why is a good man hard to find?“The Lady with the Dog” (fiction)What is so important about the lady and her dog?“The Fringe Benefits of Failure” (essay)How can failure be beneficial?“An Epidemic of Fear” (essay)What is causing the epidemic of fear?“New Therapies to Aid Muscle Regeneration” (article)How do these new therapies aid muscle regeneration?

Write down your PQ, either on the text itself or on a separate sheet of paper for note-taking. When you read with a purpose–like answering a question–it becomes easier to identify and annotate what’s important in the text.

Annotate with your PQ in Mind

It’s much easier to take good notes when you have a reading goal–something to answer or accomplish, such as a PQ.

As you read and annotate the text, refer to your purpose question. Search the text for details that relate to and help you answer your PQ. When you find relevant details, underline them and record how the detail relates to your PQ. If you can’t write on the text itself, record your thoughts on a separate paper or word document.

Here’s how and where I annotate a text, and what I usually write in my annotations.

Where and How to Annotate a TextWhat to Write Underline the text Questions –what did you ask or wonder while reading?Write in the margin Thoughts and connections –what did the text make you think about?Use a separate sheet of paper Comments –what made you underline that particular word or detail?On your phone or computer–use a notetaking app or a Google Doc Significance –why is that particular detail important?

As you read the text, constantly ask yourself, How does this information help me answer my PQ? When you’re finished with the text, you should be able to answer your purpose question–and the notes you’ve taken should help you do that.

To monitor your own comprehension while you read, remain aware of the text’s 5 Ws: who, what, where, when, why.

After every sentence or section, reflect to verify the following information:

Who: Who is the text about? Who is narrating, or telling the story?

What: What is the text about?

Where: Where do the text’s events take place?

When: When did the text’s events occur?

Why: Why did this main event occur? Why did the storyteller write this text?

At any given point while you read, you should be able to identify this context. If you realize that you’re disoriented and have lost track of some key Ws, revisit the most recent sentences to see if you missed something critical. Then, continue on with the text, mindfully searching for the information you’re missing.

If you finish reading and still feel uncertain about this core information, revisit the first paragraph. A passage’s first paragraph usually provides fundamental details–such as the characters, setting, main event, and the story’s general context. Revisiting this paragraph sometimes alerts you to basic details you overlooked during your first readthrough.

The 5 Ws also work as an annotation strategy, where you underline all textual information related to the 5 Ws.

Notice the Conflict

Every story or passage centers around at least one conflict. A conflict is the characters’ primary struggle–the issue they’re faced with, the main challenge they try to overcome.