Graduate Writing Center

Introductions, thesis statements, and roadmaps - graduate writing center.

- Citations / Avoiding Plagiarism

- Critical Thinking

- Discipline-Specific Resources

- Generative AI

- iThenticate FAQ

- Types of Papers

- Standard Paper Structure

Introductions, Thesis Statements, and Roadmaps

- Body Paragraphs and Topic Sentences

- Literature Reviews

- Conclusions

- Executive Summaries and Abstracts

- Punctuation

- Style: Clarity and Concision

- Writing Process

- Writing a Thesis

- Quick Clips & Tips

- Presentations and Graphics

The first paragraph or two of any paper should be constructed with care, creating a path for both the writer and reader to follow. However, it is very common to adjust the introduction more than once over the course of drafting and revising your document. In fact, it is normal (and often very useful, or even essential!) to heavily revise your introduction after you've finished composing the paper, since that is most likely when you have the best grasp on what you've been aiming to say.

The introduction is your opportunity to efficiently establish for your reader the topic and significance of your discussion, the focused argument or claim you’ll make contained in your thesis statement, and a sense of how your presentation of information will proceed.

There are a few things to avoid in crafting good introductions. Steer clear of unnecessary length: you should be able to effectively introduce the critical elements of any project a page or less. Another pitfall to watch out for is providing excessive history or context before clearly stating your own purpose. Finally, don’t lose time stalling because you can't think of a good first line. A funny or dramatic opener for your paper (also known as “a hook”) can be a nice touch, but it is by no means a required element in a good academic paper.

Introductions, Thesis Statements, and Roadmaps Links

- Short video (5:47): " Writing an Introduction to a Paper ," GWC

- Handout (printable): " Introductions ," University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Writing Center

- Handout (printable): " Thesis Statements ," University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Writing Center

- NPS-specific one-page (printable) S ample Thesis Chapter Introduction with Roadmap , from "Venezuela: A Revolution on Standby," Luis Calvo

- Short video (3:39): " Writing Ninjas: How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement "

- Video (5:06): " Thesis Statements ," Purdue OWL

Writing Topics A–Z

This index links to the most relevant page for each item. Please email us at [email protected] if we're missing something!

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Published on June 7, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical early steps in your writing process . It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding the specifics of your dissertation topic and showcasing its relevance to your field.

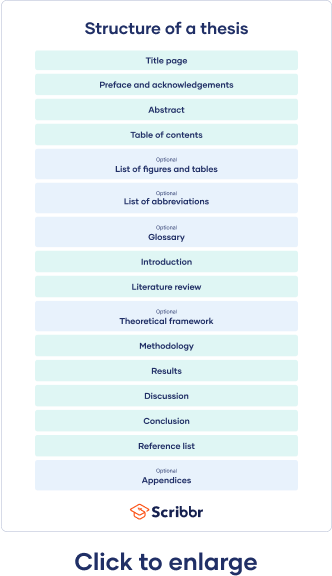

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation , such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

In the final product, you can also provide a chapter outline for your readers. This is a short paragraph at the end of your introduction to inform readers about the organizational structure of your thesis or dissertation. This chapter outline is also known as a reading guide or summary outline.

Table of contents

How to outline your thesis or dissertation, dissertation and thesis outline templates, chapter outline example, sample sentences for your chapter outline, sample verbs for variation in your chapter outline, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis and dissertation outlines.

While there are some inter-institutional differences, many outlines proceed in a fairly similar fashion.

- Working Title

- “Elevator pitch” of your work (often written last).

- Introduce your area of study, sharing details about your research question, problem statement , and hypotheses . Situate your research within an existing paradigm or conceptual or theoretical framework .

- Subdivide as you see fit into main topics and sub-topics.

- Describe your research methods (e.g., your scope , population , and data collection ).

- Present your research findings and share about your data analysis methods.

- Answer the research question in a concise way.

- Interpret your findings, discuss potential limitations of your own research and speculate about future implications or related opportunities.

For a more detailed overview of chapters and other elements, be sure to check out our article on the structure of a dissertation or download our template .

To help you get started, we’ve created a full thesis or dissertation template in Word or Google Docs format. It’s easy adapt it to your own requirements.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

It can be easy to fall into a pattern of overusing the same words or sentence constructions, which can make your work monotonous and repetitive for your readers. Consider utilizing some of the alternative constructions presented below.

Example 1: Passive construction

The passive voice is a common choice for outlines and overviews because the context makes it clear who is carrying out the action (e.g., you are conducting the research ). However, overuse of the passive voice can make your text vague and imprecise.

Example 2: IS-AV construction

You can also present your information using the “IS-AV” (inanimate subject with an active verb ) construction.

A chapter is an inanimate object, so it is not capable of taking an action itself (e.g., presenting or discussing). However, the meaning of the sentence is still easily understandable, so the IS-AV construction can be a good way to add variety to your text.

Example 3: The “I” construction

Another option is to use the “I” construction, which is often recommended by style manuals (e.g., APA Style and Chicago style ). However, depending on your field of study, this construction is not always considered professional or academic. Ask your supervisor if you’re not sure.

Example 4: Mix-and-match

To truly make the most of these options, consider mixing and matching the passive voice , IS-AV construction , and “I” construction .This can help the flow of your argument and improve the readability of your text.

As you draft the chapter outline, you may also find yourself frequently repeating the same words, such as “discuss,” “present,” “prove,” or “show.” Consider branching out to add richness and nuance to your writing. Here are some examples of synonyms you can use.

| Address | Describe | Imply | Refute |

| Argue | Determine | Indicate | Report |

| Claim | Emphasize | Mention | Reveal |

| Clarify | Examine | Point out | Speculate |

| Compare | Explain | Posit | Summarize |

| Concern | Formulate | Present | Target |

| Counter | Focus on | Propose | Treat |

| Define | Give | Provide insight into | Underpin |

| Demonstrate | Highlight | Recommend | Use |

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

The title page of your thesis or dissertation goes first, before all other content or lists that you may choose to include.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review , research methods , avenues for future research, etc.)

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, November 21). Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/dissertation-thesis-outline/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation table of contents in word | instructions & examples, figure and table lists | word instructions, template & examples, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Aspect | Thesis | Thesis Statement |

Definition | An extensive document presenting the author's research and findings, typically for a degree or professional qualification. | A concise sentence or two in an essay or research paper that outlines the main idea or argument. |

Position | It’s the entire document on its own. | Typically found at the end of the introduction of an essay, research paper, or thesis. |

Components | Introduction, methodology, results, conclusions, and bibliography or references. | Doesn't include any specific components |

Purpose | Provides detailed research, presents findings, and contributes to a field of study. | To guide the reader about the main point or argument of the paper or essay. |

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

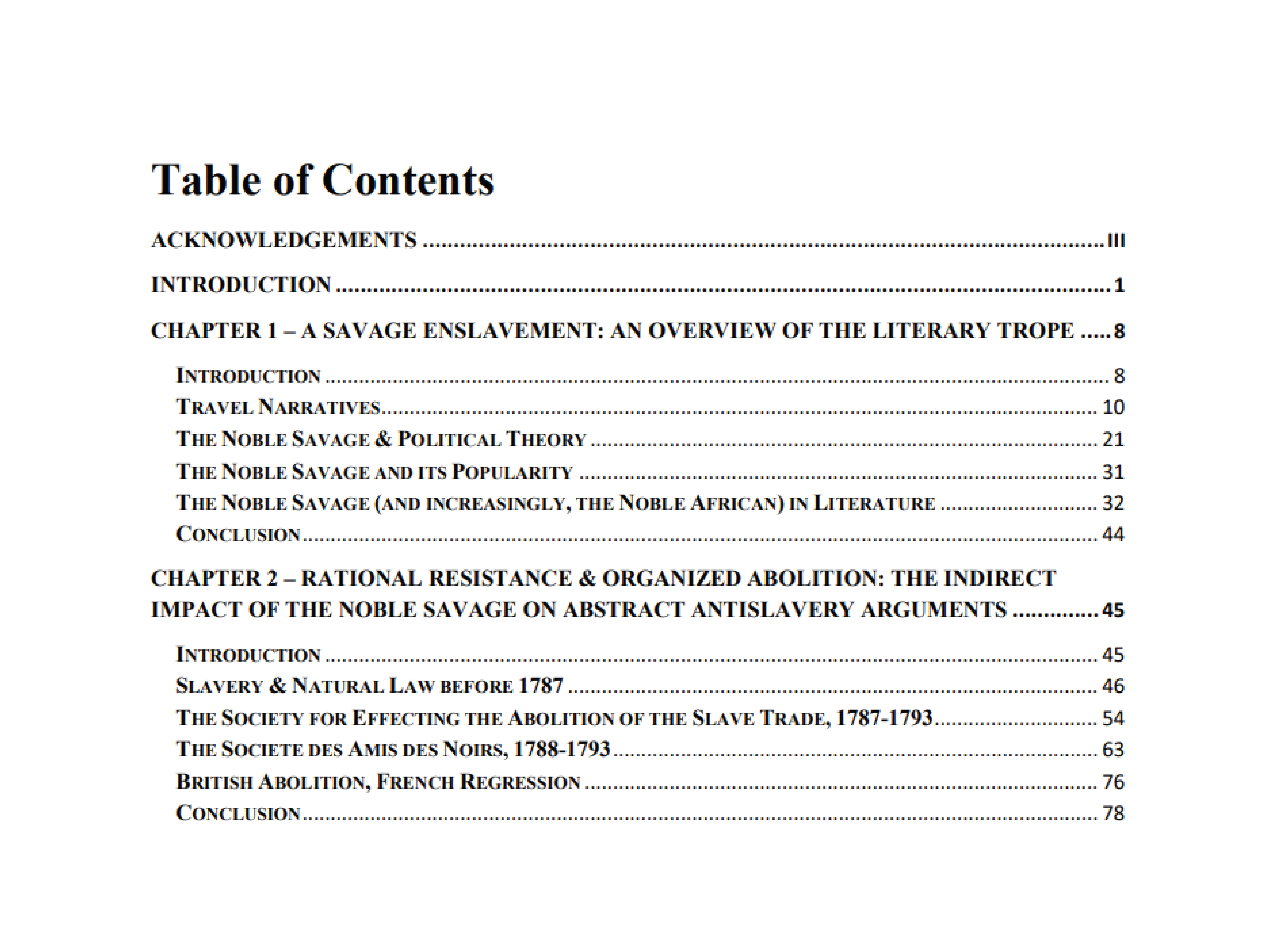

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Aspect | Thesis | Dissertation |

Purpose | Often for a master's degree, showcasing a grasp of existing research | Primarily for a doctoral degree, contributing new knowledge to the field |

Length | 100 pages, focusing on a specific topic or question. | 400-500 pages, involving deep research and comprehensive findings |

Research Depth | Builds upon existing research | Involves original and groundbreaking research |

Advisor's Role | Guides the research process | Acts more as a consultant, allowing the student to take the lead |

Outcome | Demonstrates understanding of the subject | Proves capability to conduct independent and original research |

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

This ChatGPT Alternative Will Change How You Read PDFs Forever!

Smallpdf vs SciSpace: Which ChatPDF is Right for You?

Adobe PDF Reader vs. SciSpace ChatPDF — Best Chat PDF Tools

- Directories

Thesis structures

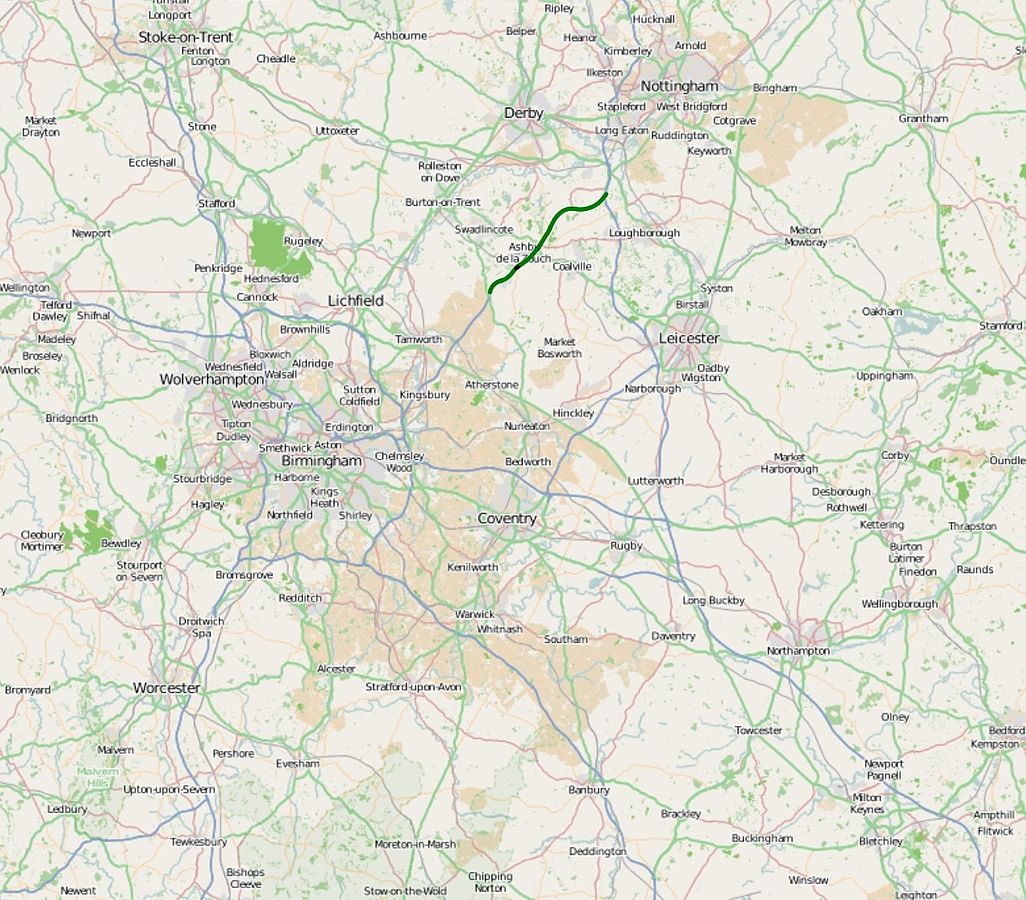

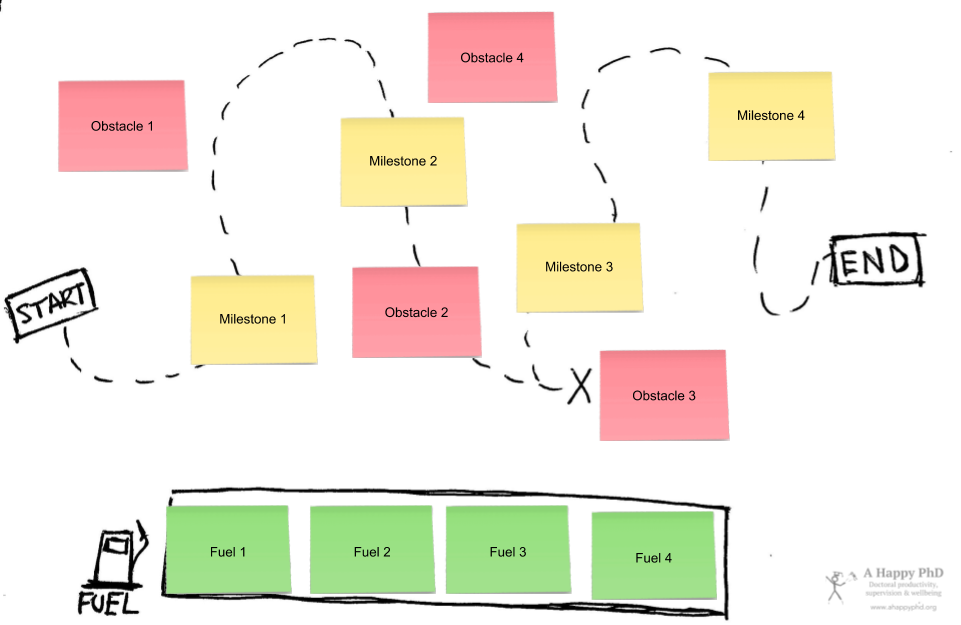

Whether you're writing a traditional thesis, thesis by compilation or an exegesis, your work needs to have an argument (some disciplines use key message, narrative, story or exposition). The argument is your answer to your research question/s, and the structure of your thesis should support the argument. A thesis argument map can help you to stay on track and can save you a lot of time writing.

Thesis argument maps

Key points:

- a thesis needs a clear research question/s or aim/s

- a thesis needs an argument that answers the research question/s

- each part of the thesis should contribute to your argument

- the thesis structure should support your argument

- an argument map can be very useful to guide you throughout your project

While there are different ways to produce an outline, we recommend using an argument map. Having an argument map planned out can be helpful for people in both the early and later stages of a research project. Even though in the early stages of your project you won't know exactly how it will turn out, it's still helpful to have a sense of where you are going and what you need to do. In the later stages of a project, you can revisit your argument map to see whether the different parts of the project still fit together logically.

On this page there are links to argument map examples and templates that you can choose from to help you organise your thesis or exegesis.

Filling out your argument map

To fill out your argument map, do the following.

- Write down your research question/s or aim/s in the top part of the map.

- Underneath the research question or aims, you'll see 'Argument' or 'Central narrative'. You might like to think of your argument as the take home message that tells the reader what your research has found overall. Even if you don't yet know the answer to your research question, write down what you anticipate your main answer/s will be. Having an idea of your argument or narrative helps you to plan out your chapters logically.

- Reflect on your argument: does it answer the research question? If it doesn't, do you need to clarify the argument? Or do you need to refine your research question?

- The introduction column outlines common elements of an introduction. Jot down your ideas in relation to each of the points.

- Write down the broad purpose of each chapter in the first row of the chapter columns. How will that chapter help you to answer your research question? How do the chapters follow on from one another?

- Jot down what you will argue in each of your chapter sections. You may have fewer than three sections in a chapter, so adapt the template as you like. How does each chapter section contribute to your chapter's argument? What evidence will you draw on?

- Reflect on your overall thesis structure. Are the chapters in a logical order to answer your research question/s? Does the structure best emphasise your analysis or themes? Are the sections organised around your themes or analytical points? Do you leave plenty of room to address counterarguments? Would another structure work? If so, which structure do you think most clearly answers your research question/s and shows a logical progression of analysis?

When you have a draft outline, carefully review it with your supervisor: is there unnecessary material (i.e. not directly related to the research question/s)? If so, remove or rework it. Is there missing material to add? Whenever you want to make a major change to your work, outlining it first can help you to consider new, more persuasive possibilities for structure.

Another way to test whether your thesis structure is persuasive and logical is to talk about it with someone who knows very little about your topic. You could try explaining it to a friend, to see whether they need to know the information in a certain sequence, and to see whether there are ideas you need to spend more/less time on explaining. You can also make an appointment at Academic Skills to discuss your argument map.

Principles of structure

The main principle of writing an outline is to work out a structure that best supports your argument. To do this, first consider your research question, and how you would persuade someone that your response is defensible. For example, if you have a question that asks for a comparison of two or more case studies, your structure needs to enable you to make that comparison effectively. You might have a chapter or section that provides a brief overview of each case study. Then, you could have a chapter that compares the case studies in relation to one variable or theme. You could then follow with a chapter that compares the case studies in relation to another variable or theme, and so on. In this way, you would have a structure that enables comparison.

If a part of your thesis does not seem to fit in, ask yourself how it helps you to answer the question. This can help you to identify where it would fit better. Otherwise, you might need to cut the section out of your thesis - you could consider whether it would work well in a separate publication instead.

To decide which structure is best for you, it's useful to have a look at other examples in your area. You can access past ANU theses on the ANU Library's digital thesis collection , you can ask your supervisor, and/or you can ask your College administrators to show you some past samples. When you look at them, consider:

- is it clear how each section of the thesis answers the research question?

- does the structure logically support the argument?

- is there a lot of background information that could be condensed?

- if the thesis is making comparisons, does the structure help you to understand the comparisons?

Thesis by compilation

Reference documents

- Exegesis narrative map (DOCX, 65.15 KB)

- Long Thesis Argument Map (DOCX, 65.8 KB)

- Sciences thesis argument map (DOCX, 64.9 KB)

- Short Thesis Argument Map (DOCX, 64.48 KB)

- Sample Epidemiology thesis argument map (PDF, 27.17 KB)

- Sample International Relations thesis argument map (PDF, 23.64 KB)

- Sample Film Studies thesis argument map (PDF, 45.92 KB)

Use contact details to request an alternative file format.

- ANU Library Academic Skills

- +61 2 6125 2972

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

6 ways to use concept mapping in your research

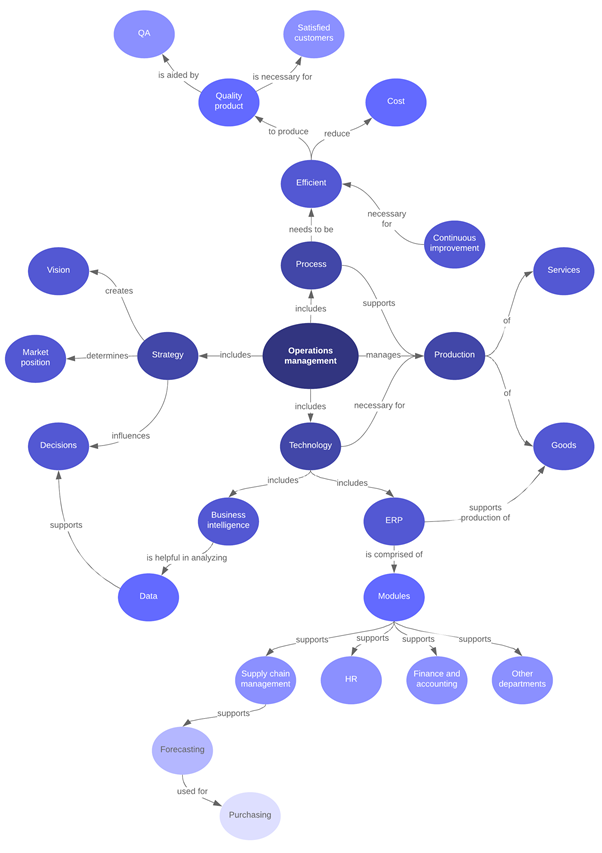

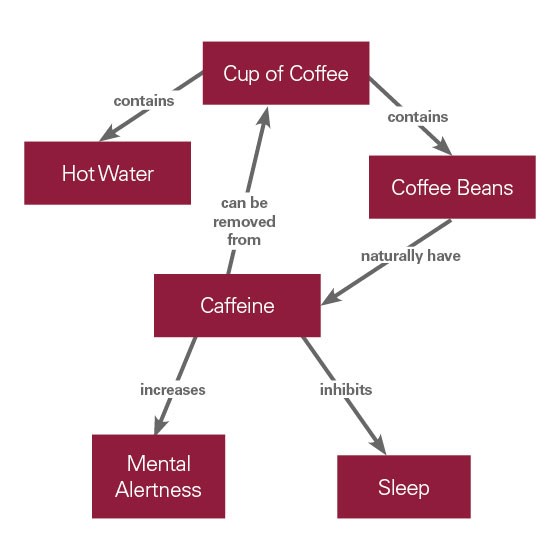

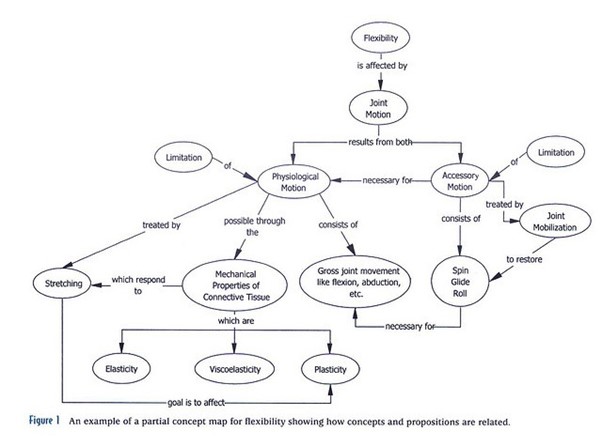

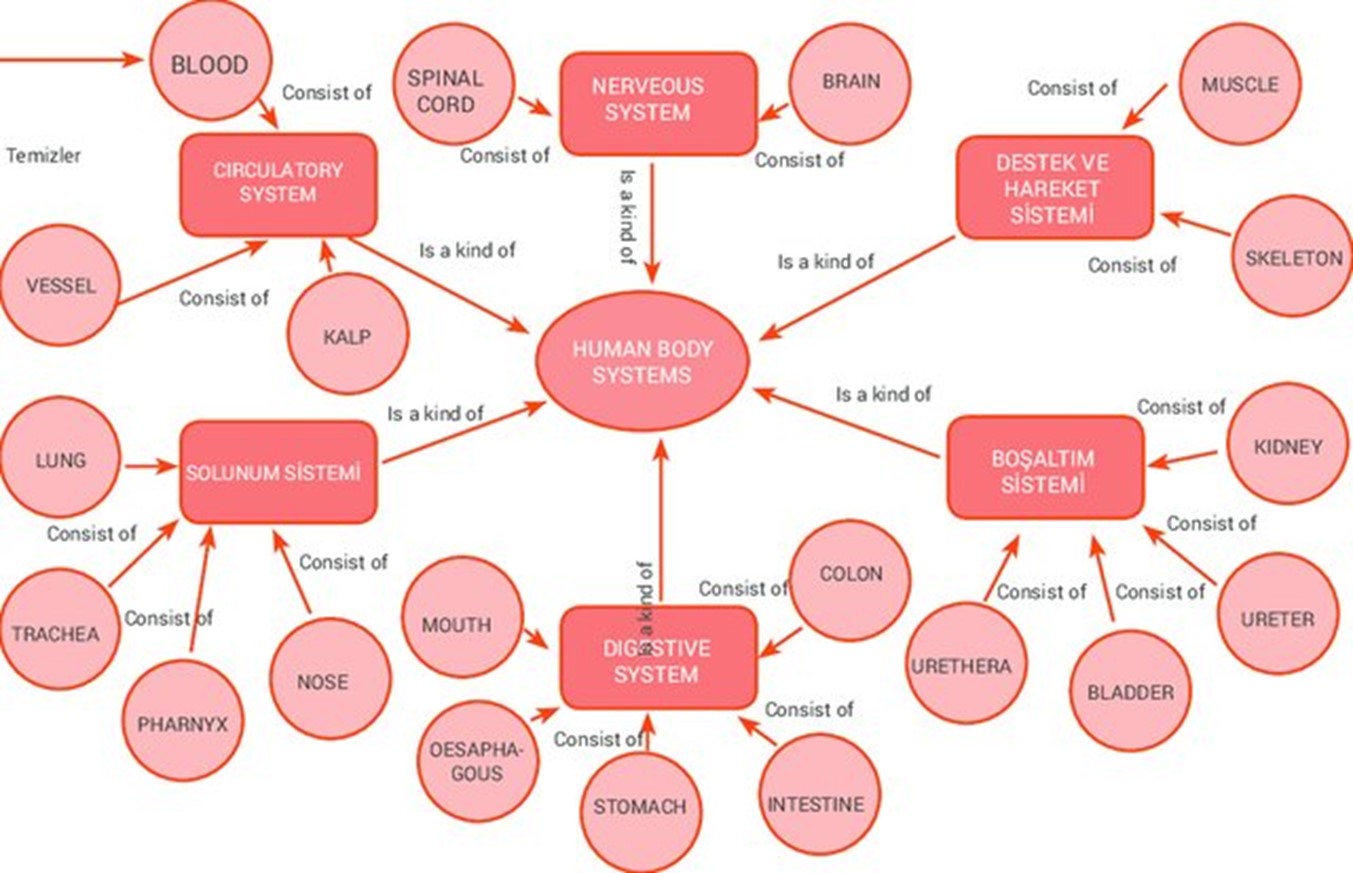

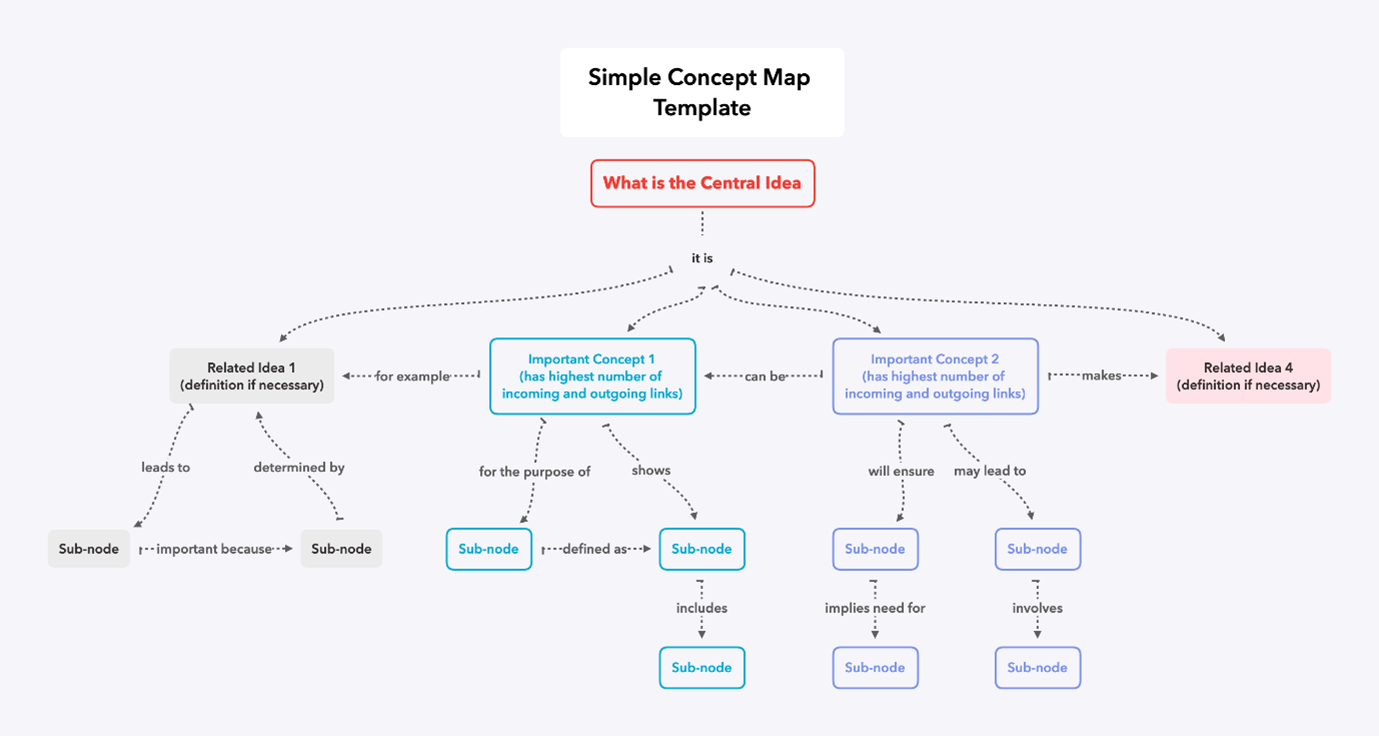

Joseph Novak developed concept mapping in the 1970s and ever since, it has been used to present the construction of knowledge. A concept map is a great way to present all the moving parts of your research project in one visually appealing figure. I recommend using this technique when you start thinking about your new research topic all the way through to the end product, and once you submitted your thesis, dissertation or research article, you can use concept mapping to plan your next project. If you prefer to watch the video explaining the 6 steps, scroll down.

What is the purpose of concept mapping?

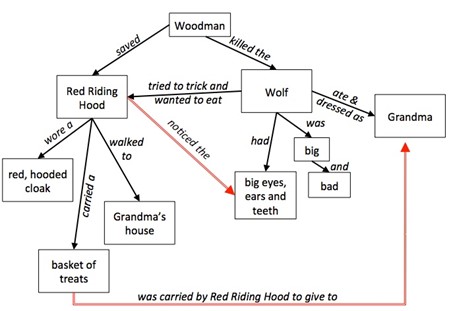

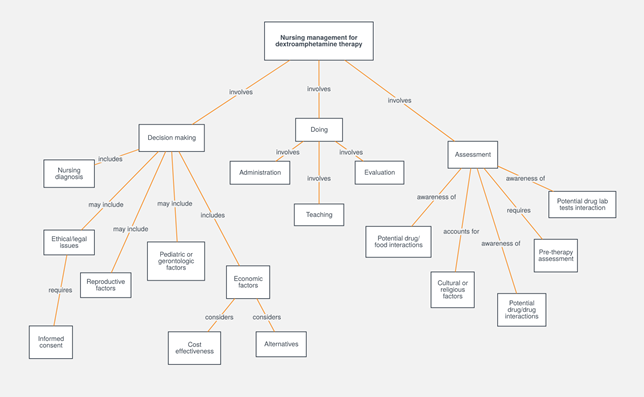

You may wonder what the purpose of a concept map is. A concept map shows the different “ideas” which form part of your research project, as well as the relationships between them. A concept map is a visual presentation of concepts as shapes, circles, ovals, triangles or rectangles, and the relationships between these concepts are presented by arrows. Your concept map will show the concept in words inside a shape, and the relationship is then presented in words next to each arrow, so that each branch reads like a sentence. What is the difference between a mind map and a concept map? A mind map is different from a concept map in that a mind map puts much less emphasis on the relationship between concepts.

How to use a concept map in your research

Don’t wait to put your concept map together until only after you have, what you consider, “all the knowledge” and have read “all the literature” (anyway, with two million research articles published each year, will that day ever come?). In the very early stages, when you start thinking about your research project, draw your concept map to get your thoughts organised. Then, as you become more and more abreast with the research out there, modify your concept map.

The process of creating a concept map is an iterative one and you will find that it feels like you have drawn and redrawn the map over and over so many times that you wonder if you are ever going to get to a final version. This process in itself is a learning experience and is vital to sort the concepts out for yourself. If you have clarity in your own head, it is easier to explain what your research is all about to someone else. In addition, including a concept map into a dissertation, thesis, or research article (where relevant) makes it easier for the reader (including the examiner or reviewer) to understand what your research project is all about. There are several instances in your research journey where a concept map will come in handy.

#1 Use a concept map to brainstorm your research topic

When you are conceptualising your research topic, create a concept map to put all the different aspects related to your research topic onto paper and to show the relationships between them. This will give you a bird’s eye view of all the moving parts associated with the chosen research topic. You will also, most probably, realise that the topic is too broad, and you’ll be able to zoom in a bit more to focus your research question better. But before you settle on a specific research question, do a bit of reading around the topic area. Your concept map will show you which keywords to search for.

#2 Use a concept map when planning the search strategy for your literature review

Jumping right into those databases to do a search for articles to include in your literature review can really take you down the deepest darkest rabbit hole. One of those where you find an appropriate article, then gets suggested a few related articles and then you find another few related articles to the related articles, and after 4 hours you can’t even remember what your actual focus was. To avoid this situation, draw your concept map first. You can use the concept map you drew when you brainstormed your research topic to give you guidance in terms of the keywords to search for. Planning your search strategy before you jump in will ensure that you remain on the well-lit path.

#3 Add a concept map to your completed literature review chapter

As you read more about your research topic, you’ll get a better idea of the relationships between the current concepts, and you’ll find more concepts to add to your concept map. Adapt your concept map as you go along, and once you have the final version of your literature review, add your concept map as a figure to your literature review chapter. This will give the reader a good overview of your literature review and it will make their hearts happy because we all know how nice it is to be rewarded with a picture after reading pages and pages of text.

#4 Use a concept map to plan your discussion

Once you completed your data analysis and interpretation, developing a concept map for your discussion will give you clarity on what to include in your discussion chapter or section.

#5 Add a concept map to your completed research project

Once you have completed your entire research project and you want to show how your findings filled a gap in the literature, you can indicate this by modifying the concept map which you created for our literature review. This is a great way to show how your research findings have added to the existing concepts related to your research topic.

#6 Use a concept map to show your research niche area

You can use a concept map to visually present your own research niche area and as your career progresses and you create more knowledge in a specific niche, you can add to your concept map.

How to make a concept map for research

Go to a place where there are very few distractions, a place that is conducive to letting those creative juices flow freely. Seeing that we all function differently, shall I rather say, a place which you perceive as having few distractions. It may be in a park, in your garden, at a restaurant, in the library or in your own study.

Take out a blank piece of paper and start thinking about your research project. Of course, you can do it on a blank page on your laptop as well. One of my students used sticky notes with each sticky note presenting a concept, and with smaller strips of sticky notes showing the relationships between concepts. You can even get all fancy and use concept mapping software. But as a start, a blank piece of paper is more than enough.

Jot down all the ideas that come to mind while you answer the following questions: What is your research about? Why is your research important? What gap does your research fill? What problem will your research solve? What influences your research outcome? Just jot all your thoughts down. Then, once you have all your thoughts on paper, see if you can identify some relationships between the concepts which you noted down. What comes before what? What is a consequence of what? What is associated with what?

Once you are happy with what you have put together, present it to a friend, preferably at a time when both of you are not in a hurry to get somewhere. At a bar with loud music may not work well, and on a first date may also not be a good idea. Explain what is going on in the concept map and give your friend a chance to ask some questions. As you explain it to someone, as well as through fielding your friend’s questions, it will start to make more sense to you, and you will most probably move some concepts around and add new ones. Repeat this process with someone else when you feel you need some more input.

If you are planning to feature your concept map in your thesis, dissertation or research article, now is the time to turn your rough concept map into something more presentable. One can easily get totally lost when it comes to choosing software to create a concept map. Some of the software out there is paid for while others give you a free version for some basic concept mapping. Be careful of that software which only gives you free access for 30 days, remember, you are going to change your concept map quite a few times as time goes on. If you prefer to use software which you are already familiar with, why not just do it in PowerPoint or Word? On the other hand, Lucidchart is really user-friendly. Watch the video below to see how easy it is to create a concept map with Lucidchart. Explore a few options and see what works for you, but be careful, this exploration can take you down that 4-hour rabbit hole and when a proposal submission deadline is looming, that rabbit hole is a dark place to be in.

We'd like to acknowledge Coffee Machine Cleaning for the image of the coffee cup and notebook used in this blog post.

Examples of concept maps

Here are a few examples of concept maps that show the concepts and the relationship between the concepts well. Click on the image to visit the original source. Go and enjoy developing a concept map for your research!

One last thing before you go, for more valuable content related to academic research, subscribe to the Research Masterminds YouTube Channel and hit the bell so that you get notified when I upload a new video. If you are a (post)graduate student working on a masters or doctoral research project, and you are passionate about life, adamant about completing your studies successfully and ready to get a head-start on your academic career, this opportunity is for you! Join our awesome membership site - a safe haven offering you coaching, community and content to boost your research experience and productivity. Check it out! https://www.researchmasterminds.com/academy .

Example 1 Little Red Riding Hood

Example 2 Nursing Management

Example 3 Operations Management

Example 4 Cup of Coffee

Example 5 Flexibility

Example 6 Human Body Systems

Example 7 Simple Concept Map Template

If you prefer to watch the video, here it is:

Leave a comment

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Published on 15 September 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 25 July 2024.

A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a PhD program in the UK.

Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Indeed, alongside a dissertation , it is the longest piece of writing students typically complete. It relies on your ability to conduct research from start to finish: designing your research , collecting data , developing a robust analysis, drawing strong conclusions , and writing concisely .

Thesis template

You can also download our full thesis template in the format of your choice below. Our template includes a ready-made table of contents , as well as guidance for what each chapter should include. It’s easy to make it your own, and can help you get started.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Thesis vs. thesis statement, how to structure a thesis, acknowledgements or preface, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review, methodology, reference list, proofreading and editing, defending your thesis, frequently asked questions about theses.

You may have heard the word thesis as a standalone term or as a component of academic writing called a thesis statement . Keep in mind that these are two very different things.

- A thesis statement is a very common component of an essay, particularly in the humanities. It usually comprises 1 or 2 sentences in the introduction of your essay , and should clearly and concisely summarise the central points of your academic essay .

- A thesis is a long-form piece of academic writing, often taking more than a full semester to complete. It is generally a degree requirement to complete a PhD program.

- In many countries, particularly the UK, a dissertation is generally written at the bachelor’s or master’s level.

- In the US, a dissertation is generally written as a final step toward obtaining a PhD.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

The final structure of your thesis depends on a variety of components, such as:

- Your discipline

- Your theoretical approach

Humanities theses are often structured more like a longer-form essay . Just like in an essay, you build an argument to support a central thesis.

In both hard and social sciences, theses typically include an introduction , literature review , methodology section , results section , discussion section , and conclusion section . These are each presented in their own dedicated section or chapter. In some cases, you might want to add an appendix .

Thesis examples

We’ve compiled a short list of thesis examples to help you get started.

- Example thesis #1: ‘Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the “Noble Savage” on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807’ by Suchait Kahlon.

- Example thesis #2: ‘”A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man”: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947’ by Julian Saint Reiman.

The very first page of your thesis contains all necessary identifying information, including:

- Your full title

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date.

Sometimes the title page also includes your student ID, the name of your supervisor, or the university’s logo. Check out your university’s guidelines if you’re not sure.

Read more about title pages

The acknowledgements section is usually optional. Its main point is to allow you to thank everyone who helped you in your thesis journey, such as supervisors, friends, or family. You can also choose to write a preface , but it’s typically one or the other, not both.

Read more about acknowledgements Read more about prefaces

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

An abstract is a short summary of your thesis. Usually a maximum of 300 words long, it’s should include brief descriptions of your research objectives , methods, results, and conclusions. Though it may seem short, it introduces your work to your audience, serving as a first impression of your thesis.

Read more about abstracts

A table of contents lists all of your sections, plus their corresponding page numbers and subheadings if you have them. This helps your reader seamlessly navigate your document.

Your table of contents should include all the major parts of your thesis. In particular, don’t forget the the appendices. If you used heading styles, it’s easy to generate an automatic table Microsoft Word.

Read more about tables of contents

While not mandatory, if you used a lot of tables and/or figures, it’s nice to include a list of them to help guide your reader. It’s also easy to generate one of these in Word: just use the ‘Insert Caption’ feature.

Read more about lists of figures and tables

If you have used a lot of industry- or field-specific abbreviations in your thesis, you should include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations . This way, your readers can easily look up any meanings they aren’t familiar with.

Read more about lists of abbreviations

Relatedly, if you find yourself using a lot of very specialised or field-specific terms that may not be familiar to your reader, consider including a glossary . Alphabetise the terms you want to include with a brief definition.

Read more about glossaries

An introduction sets up the topic, purpose, and relevance of your thesis, as well as expectations for your reader. This should:

- Ground your research topic , sharing any background information your reader may need

- Define the scope of your work

- Introduce any existing research on your topic, situating your work within a broader problem or debate

- State your research question(s)

- Outline (briefly) how the remainder of your work will proceed

In other words, your introduction should clearly and concisely show your reader the “what, why, and how” of your research.

Read more about introductions

A literature review helps you gain a robust understanding of any extant academic work on your topic, encompassing:

- Selecting relevant sources

- Determining the credibility of your sources

- Critically evaluating each of your sources

- Drawing connections between sources, including any themes, patterns, conflicts, or gaps

A literature review is not merely a summary of existing work. Rather, your literature review should ultimately lead to a clear justification for your own research, perhaps via:

- Addressing a gap in the literature

- Building on existing knowledge to draw new conclusions

- Exploring a new theoretical or methodological approach

- Introducing a new solution to an unresolved problem

- Definitively advocating for one side of a theoretical debate

Read more about literature reviews

Theoretical framework

Your literature review can often form the basis for your theoretical framework, but these are not the same thing. A theoretical framework defines and analyses the concepts and theories that your research hinges on.

Read more about theoretical frameworks

Your methodology chapter shows your reader how you conducted your research. It should be written clearly and methodically, easily allowing your reader to critically assess the credibility of your argument. Furthermore, your methods section should convince your reader that your method was the best way to answer your research question.

A methodology section should generally include:

- Your overall approach ( quantitative vs. qualitative )

- Your research methods (e.g., a longitudinal study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., interviews or a controlled experiment

- Any tools or materials you used (e.g., computer software)

- The data analysis methods you chose (e.g., statistical analysis , discourse analysis )

- A strong, but not defensive justification of your methods

Read more about methodology sections

Your results section should highlight what your methodology discovered. These two sections work in tandem, but shouldn’t repeat each other. While your results section can include hypotheses or themes, don’t include any speculation or new arguments here.

Your results section should:

- State each (relevant) result with any (relevant) descriptive statistics (e.g., mean , standard deviation ) and inferential statistics (e.g., test statistics , p values )

- Explain how each result relates to the research question

- Determine whether the hypothesis was supported

Additional data (like raw numbers or interview transcripts ) can be included as an appendix . You can include tables and figures, but only if they help the reader better understand your results.

Read more about results sections

Your discussion section is where you can interpret your results in detail. Did they meet your expectations? How well do they fit within the framework that you built? You can refer back to any relevant source material to situate your results within your field, but leave most of that analysis in your literature review.

For any unexpected results, offer explanations or alternative interpretations of your data.

Read more about discussion sections

Your thesis conclusion should concisely answer your main research question. It should leave your reader with an ultra-clear understanding of your central argument, and emphasise what your research specifically has contributed to your field.

Why does your research matter? What recommendations for future research do you have? Lastly, wrap up your work with any concluding remarks.

Read more about conclusions

In order to avoid plagiarism , don’t forget to include a full reference list at the end of your thesis, citing the sources that you used. Choose one citation style and follow it consistently throughout your thesis, taking note of the formatting requirements of each style.

Which style you choose is often set by your department or your field, but common styles include MLA , Chicago , and APA.

Create APA citations Create MLA citations

In order to stay clear and concise, your thesis should include the most essential information needed to answer your research question. However, chances are you have many contributing documents, like interview transcripts or survey questions . These can be added as appendices , to save space in the main body.

Read more about appendices

Once you’re done writing, the next part of your editing process begins. Leave plenty of time for proofreading and editing prior to submission. Nothing looks worse than grammar mistakes or sloppy spelling errors!

Consider using a professional thesis editing service to make sure your final project is perfect.

Once you’ve submitted your final product, it’s common practice to have a thesis defense, an oral component of your finished work. This is scheduled by your advisor or committee, and usually entails a presentation and Q&A session.

After your defense, your committee will meet to determine if you deserve any departmental honors or accolades. However, keep in mind that defenses are usually just a formality. If there are any serious issues with your work, these should be resolved with your advisor way before a defense.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation shouldn’t take up more than 5-7% of your overall word count.

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

If you only used a few abbreviations in your thesis or dissertation, you don’t necessarily need to include a list of abbreviations .

If your abbreviations are numerous, or if you think they won’t be known to your audience, it’s never a bad idea to add one. They can also improve readability, minimising confusion about abbreviations unfamiliar to your reader.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organise your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation, such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2024, July 25). What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/thesis-ultimate-guide/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation & thesis outline | example & free templates, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction.

Types Of Thesis Statements

Different Types of Thesis Statements Explained with Examples

Published on: Sep 3, 2024

Last updated on: Sep 3, 2024

People also read

If you’ve come to this, You might be asking yourself, "How many types of thesis statements are there?"

Well, there are different types of thesis statements, each designed for a specific kind of essay. If you’re looking to inform, persuade, or analyze, picking the right type of thesis statement is key.

We’ll explore the main types and even some you might not be familiar with, giving you clear examples to guide you along the way.

By the end of this blog, you'll know all about the different types of thesis statements in essays and how to use them in your writing.

Let's get started and make your essays more structured and impactful!

The 3 Major Types of Thesis Statements

A thesis statement is a single sentence that tells the main idea or point of your essay. A good thesis statement clearly explains what your essay is about and what you’re trying to show or argue.

Depending on the nature and the type of paper you’re writing, thesis statements can be divided into three primary types.

Expository/Explanatory Thesis Statement

An explanatory or expository thesis statement is all about giving information and explaining something. When you use this type, you’re setting up your essay to provide details, describe a process, or clarify a concept. Your goal is to inform the reader rather than to argue or analyze.

Example: “The process of photosynthesis involves the conversion of sunlight into energy, which plants use to grow and produce oxygen.”

In this example, the thesis statement clearly indicates that the essay will explain how photosynthesis works. It doesn’t try to persuade the reader or analyze different aspects; it simply provides information on a topic.

Argumentative Thesis Statement

In this example, the thesis statement clearly indicates that the argumentative essay will explain how photosynthesis works. It doesn’t try to persuade the reader or analyze different aspects; it simply provides information on a topic.

Example: “Implementing a four-day workweek would increase productivity and improve employee well-being, making it a beneficial change for modern businesses.”

Here, the thesis statement makes a clear argument that the four-day workweek is a positive change. The essay will then focus on providing evidence and reasons to support this point of view, as well as addressing any opposing views.

Analytical Thesis Statement

An analytical thesis statement breaks down a topic into its components and examines them. It’s used when you want to analyze how something works or evaluate different parts of a subject. This type of thesis statement is great for essays that involve analyzing literature, processes, or events.

Example: “In Shakespeare’s Hamlet , the use of soliloquies reveals the internal conflicts of the characters, illustrating their struggles with morality and action.”

This thesis statement sets up an essay that will analyze how soliloquies in Hamlet reflect the characters’ inner conflicts. It shows that the essay will dissect the use of these soliloquies and explain their significance.

Other Commonly Used Types

Besides the major types of thesis statements, there are several others that you might come across. Each type serves a different purpose and helps shape your essay in specific ways. Here’s a quick look at some commonly used kinds of thesis statements:

Persuasive Thesis Statement

- When your goal is to convince your reader of your viewpoint, a persuasive thesis statement comes into play. This type clearly presents the argument you'll support with evidence throughout your essay.

Narrative Thesis Statement

- A narrative thesis statement introduces the story or personal experience you'll describe in your essay. It sets the stage for the main event or plot of your narrative.

Descriptive Thesis Statement

- If your essay focuses on painting a vivid picture of a person, place, object, or event, you’ll use a descriptive thesis statement. This type emphasizes detailed and sensory-rich descriptions to help readers visualize the subject.

Comparative Thesis Statement

- To analyze and contrast different subjects, a comparative thesis statement is what you need. It compares two or more things, highlighting their similarities and differences.

Cause and Effect Thesis Statement

- Exploring how one event leads to another calls for a cause and effect thesis statement. This type examines the relationship between causes and their outcomes.

Evaluative Thesis Statement

- When making a judgment about the value or significance of something, an evaluative thesis statement is used. It involves assessing and critiquing the subject based on specific criteria.

Open Thesis Statement:

- An open thesis statement is broad and allows for exploring various aspects of a topic. It’s flexible and doesn’t limit the scope of the essay too much.

Closed Thesis Statement:

- A closed thesis statement is more specific and outlines the exact points or arguments that will be addressed in the essay. It gives a clear direction and indicates the structure of the argument or analysis.

How to Choose the Right Type of Thesis Statement

Choosing the right thesis statement is essential for guiding your essay in the right direction. To find the best fit, consider the following steps:

- Know Your Goal: Decide if you’re trying to inform, argue, analyze, or compare.

- Match the Format: Choose a thesis that fits the style of your essay, like narrative, descriptive, or cause and effect.

- Align with Your Points: Make sure your thesis reflects what you’ll be discussing or comparing.

- Be Clear: Your thesis should clearly show the direction of your essay.

- Be Flexible: Adjust your thesis if your focus changes during writing.

In Summary,

So, what’s the takeaway from all these different types of thesis statements? Understanding and choosing the right one can make a huge difference in how you communicate your ideas. Each type has its own role in shaping your essay.

If you need a helping hand with writing thesis statements, don’t worry—there’s help available. Try using the thesis statement generator from MyEssayWriter.ai . It’s a powerful tool that can guide you in creating a strong, clear thesis statement tailored to your essay’s needs.

Give our essay writer a try and take the guesswork out of your writing process!

Commonly Asked Questions

What is the 3 parts of a thesis statement.

- Topic: This tells the reader what the essay is about. It’s the subject you’ll be discussing.

- Claim: This is your main point or argument about the topic. It’s what you want to prove or explain.

- Reasons: These are the main reasons or points that support your claim. They outline how you’ll back up your argument in the essay.

What are the different types of thesis claims?

- Fact Claim: Asserts that something is true or false. It’s based on verifiable evidence.

- Value Claim: Argues whether something is good or bad, right or wrong. It’s based on personal or cultural values.

- Policy Claim: Suggests a course of action or change. It proposes what should be done or how things should be done differently.

- Definition Claim: Defines a term or concept in a specific way. It clarifies what something means or how it should be understood.

What is a theme statement and what are its types?

A theme statement is a sentence that shows the main message or big idea of a story. Instead of just summarizing what happens, it explains what the author wants to say about life, society, or people through the story.

Its types are:

- Universal theme statement

- Specific theme statement

- Complex theme statement

- Implicit theme statement

- Explicit theme statement

Caleb S. (Mass Literature and Linguistics, Masters)