Work by John Ruskin Summary

Work by john ruskin literary analysis, more from john ruskin.

- Art Influencers

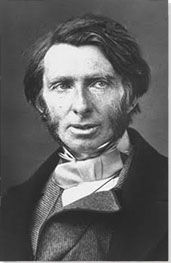

John Ruskin

British Art Critic, Painter, Social Thinker and Philanthropist

Summary of John Ruskin

An incredibly influential figure, who inspired people as diverse as Mahatma Ghandi, Leo Tolstoy, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti , Ruskin was a complex, intense, and incredibly articulate man. Although he is best known as an art critic and patron, he was a true polymath and was also a talented watercolorist, an engaging teacher, a respected geologist, and a campaigner for social and political change. The importance of nature, God, and society are reoccurring themes throughout his work and these driving forces formed the tenets of his forward-thinking beliefs. He was an advocate for new styles of painting, the protection of historic buildings, the conservation of natural landscapes, the education of women, and the improvement of conditions for the working classes. He also identified risks associated with the Industrial Revolution, such as pollution, many years before they were widely acknowledged. His writings and the ideas in them brought new artists to prominence, encouraged the formation of the National Trust, and helped to protect the architecture of Venice. His views also helped to shape welfare reforms in Britain such as the introduction of a minimum wage, free school meals, and universal healthcare.

Accomplishments

- Ruskin was an incredibly prolific writer, publishing more than 50 books on a huge range of topics from art criticism to fiction and political treatises to travel guides. It was through these writings (which included lecture transcripts and letters as well as more conventional essays) that he communicated his innovative ideas and over the course of his career, he simplified his writing style to make them as accessible to as many people as possible.

- As art critic, Ruskin championed the idea of "truth to nature" which encouraged painters to closely observe the landscape and in doing so capture the natural world as truthfully as possible, not romanticizing what they saw. This idea was hugely influential on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood , a group of young artists who rejected contemporary notions of artistic beauty and instead sought to produce a pre- Renaissance style of painting. Ruskin's emphasis on the natural (along with his dislike of mass production) also had an impact on the development of the Arts and Crafts Movement .

- Ruskin was an avid promoter of Gothic architecture and his writing influenced a widespread return from Neoclassicism to the earlier Gothic style. His work inspired architects including Le Corbusier , Frank Lloyd Wright , and Walter Gropius and his ideas are said to have been influential in the foundation of the Garden City Movement.

- Ruskin's religious upbringing continued to have an impact on his ideas and he believed that nature and beauty were inextricably bound up with concepts of the divine. He consequently argued that the best way to portray faith, was not through epic religious scenes, but through the understanding and faithful depiction of nature and the human body. This was taken to heart by the Pre-Raphaelite who attempted to harmoniously incorporate religious devotion into their work. This led to censure when developing this idea, they depicted religious figures as normal members of the working classes, with dirty clothes and fingernails instead of idealizing them.

John Ruskin and Important Artists and Artworks

Dido building Carthage, or The Rise of the Carthaginian Empire (1815)

Artist: J.M.W. Turner

This was one of ten paintings produced by Turner depicting the subject of the Carthaginian empire. Inspired by Virgil's The Aeneid , the composition shows Dido on the far left in blue robes. She is visiting her husband Sychaeus' tomb. The figure in front of her is likely to be Aeneas, a future love interest. Turner modelled the composition and style closely on the work of the well-known 17 th century landscape painter Claude Lorrain, notably his Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba (1648). According to Ruskin, however, Turner surpassed the Frenchman, writing that "Claude possesses some species of sterling excellence, but it follows not that he may not be excelled by Turner." Turner and Ruskin had a close, if complex relationship. The pair met when Ruskin's affluent father (John Ruskin senior) began to commission watercolors from the painter. Ruskin became fascinated with these works and penned his first defense of Turner when he was just 16 (although this was not published). As a result, he was invited to watch Turner paint, and the pair discussed art, with Turner asking the young critic's opinion, despite the fact that he was 30 years his junior. As a result and, in contrast to popular and critical opinion, Ruskin vehemently defended Turner in Modern Painters (1843), describing him as the "greatest of all landscape painters". By Turner's death in 1851, however, the pair had fallen out with Ruskin describing Turner's 1846 painting Angel Standing in the Sun as being "indicative of mental disease". Nevertheless, Ruskin's writing had a profound effect on Turner's success. As art historian Daisy Dunn writes: "Had it not been for Ruskin it is questionable whether Turner's art would be so popular today...Although Ruskin feared that public opinion had been permanently tainted by the critics, his words found an appreciative public."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

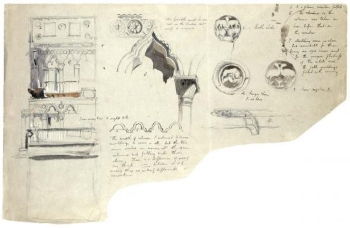

Loggia of the Ducal Palace, Venice (1849-50)

Ruskin's sketches and paintings of Venice were considered among his best, and although he never called himself an artist, an examination of this work gives a good understanding of his ideas. In this watercolor, he carefully studied the decorative columns of Venice's most famous Gothic loggia (a covered exterior gallery), as well as showing Saint Mark's Basilica in the distance. The watercolor demonstrates his talents as a draftsman and his skilled understanding of perspective and composition. Ruskin articulated his style and painterly processes in his 1857 work Elements of Drawing , in which he advocated close observation of nature. Its reach was such that Claude Monet said in 1900 that "ninety per cent of the theory of Impressionist painting is in... Elements of Drawing ." Ruskin called the Ducal Palace "the central building of the world" and for him, Venice represented spiritual purity. He believed that the intricacies and ornate designs of Gothic architecture were far superior to that of the subsequent Renaissance because they represented emotion and reverence for God. He said that Renaissance architects created for their own glory, while Gothic architects created for the glory of God, and that the Gothic style expressed man's humility in the face of the divine. He argued that the loss of Gothic architecture represented a loss of something deeply spiritual in Western society and the growth of a Pagan ethos. Ruskin's writings were responsible for the eventual Gothic revival and his books and drawings of Venice in particular were integral to securing the city's conservation. As art historian Daisy Dunn records: "Ruskin's publications sparked fresh interest in Italian art and particularly Venetian Gothic architecture. He made numerous prints and drawings, fearing that, if he did not, Venice might vanish undocumented like 'a lump of sugar in hot tea'." Ruskin's writings also influenced later architects, including the young Le Corbusier, whose early work demonstrates many of Ruskin's key principles. Frank Lloyd Wright's belief in the natural can also be seen as a result of Ruskin's influence and his skyscraper designs are based on the structural forms of trees.

Watercolor over graphite - The Met, New York

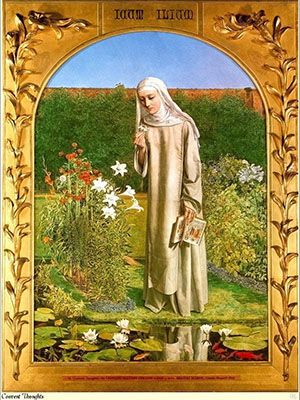

Convent Thoughts (1850-51)

Artist: Charles Allston Collins

This brightly colored oil canvas shows a nun deep in thought standing in a walled garden. She holds in her left hand a book showing a religious illustration, but it has been dropped to her side as she contemplates a passion flower - symbolic of Christ's crucifixion. The painting is executed in the minutely-detailed style of the early Pre-Raphaelites and the frame, designed by Millais, is inscribed with the words Sicit Lilium ("As the lily among thorns"), a quote taken from the Song of Solomon . The painting was exhibited at The Royal Academy in 1851. Charles Allston Collins is one of the lesser known of the Pre-Raphaelites (he was never a member of the brotherhood) but this work was nonetheless singled out by Ruskin in a letter to The Times . Ruskin commended the paintings of all the Pre-Raphaelites in the Academy exhibition, but noted particularly the botanical studies present in this image. Using this work as an example, Ruskin encouraged artists not to represent God with religious pictures, but with the natural world instead. The Pre-Raphaelites took these ideas to heart, producing a stream of art that depicted detailed and celebratory images of nature and the human body. These lessons were also taken up in America where artists at the frontier began to produce epic images of the great American West.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875)

Artist: James Whistler

Just as Ruskin had the power to build artists up, he could destroy them too. His fierce criticism of JAM Whistler caused him to instigate a court case that ultimately bankrupted him. This is one of six Nocturnes that the American artist painted depicting Cremorne Gardens in London. Much of the canvas depicts the night sky illuminated by fireworks, with the foggy night sky mixing with the billowing smoke of the fireworks. The foreground shows the banks of the River Thames, on which stand ghostlike figures, their transparency adding to the mystery of the work. Ruskin hated it. He accused Whistler of stealing Turner's style and decried the fact that he was painting the seedier side of London. Ruskin saw industrial pollution as symptomatic of moral degeneracy and this painting as an affront. When the painting was put up for sale in 1877, Ruskin wrote: "I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Whistler sued Ruskin for libel. In the court room he was asked if he thought the two days' labour he spent on Nocturne was worth the 200 guinea price tag. To applause he replied: "No. I ask it for the knowledge of a lifetime." Whistler won, but was awarded just a farthing in damages. The costs of the case financially ruined him, but the injury was not limited to Whistler. Ruskin's own inability to adapt to new styles damaged his reputation as a critic and many dismissed him as out of date; an enemy of modern art.

Oil on panel - The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, USA

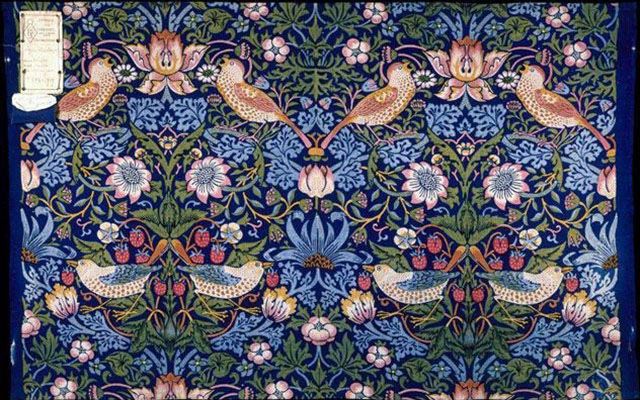

The Strawberry Thief (1883)

Artist: William Morris

This textile design is one of William Morris' most famous and the pattern shows the thrushes that stole the fruit from the garden of his Oxfordshire home. The fabric was printed by the indigo discharge method, an ancient and complex technique used for many centuries in the East. The intricate and stylized design reflects the aesthetics of Medieval revivalism to which Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement were closely aligned. Morris discovered Ruskin's writings at university and became a devoted follower of his work. The men had a lot in common; Morris revered nature and motifs of flowers, leaves and birds proliferated in his designs. They were also both appalled by the industrial revolution and its consequences - mass production, unimaginative architecture, and a decline in artisanship. They advocated a return to craftsmanship, leading to the advent of the Arts and Crafts movement which, in turn, influenced many of the principles of Art Nouveau. As art historian E. H. Gombrich wrote: "Men like Morris and Ruskin dreamt of a thorough reform of the arts and crafts, and the replacement of cheap mass-production by conscientious and meaningful handiwork. The influence of their criticism was very widespread even though the humble handicrafts which they advocated proved, under modern conditions, to be the greatest of luxuries." This is exemplified by this fabric, which due to its artisan production techniques would have been prohibitively expensive for most people.

Furniture fabric - The Victoria and Albert Museum, London

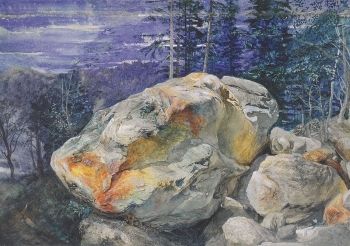

The Three Tetons (1881)

Artist: Thomas Moran

Ruskin's influence also stretched across the Atlantic to artists in the United States. The American Landscape Painter Thomas Moran was heavily influenced by Ruskinian thought and sought to reproduce the divine in his epic paintings. In this work, his subject was the distinctive Three Tetons, the principle summits of the Wyoming Range. Inspired by Ruskin's teachings, Moran sought to follow the concept of "truth to nature" which proposed that the artist had a fundamental role connecting nature and society, and to do so he went on dangerous and challenging journeys to produce epic canvases that depicted the Grand Canyon and the Rocky Mountains. Moran learned from Turner's paintings and following Ruskin's advice, made it his mission to "study nature carefully and reproduce her wonders accurately". Moran had been inspired by Modern Painters , and believed God was to be found in American topography. In turn Ruskin was a big fan, and he wrote many admiring letters to Moran and brought his work to add to his private collection. Ruskin wrote: "[n]or are there any descriptions of the Valley of Diamonds, or the Lake of the Black Islands, in the 'Arabian Nights,' anything like so wonderful as the scenes of California and the Rocky Mountains which you may ... see represented with most sincere and passionate enthusiasm by the American landscape painter, Mr Thomas Moran." By the 1850s, Ruskin had more readers in America than he did in England and his theories helped to unify artists as art historian Joni Louise Kinsey notes: "Indeed, it was Ruskin's conjunction of art with morality, religion and nature that for a time, at about mid-century, brought a number of disparate trends in American aesthetics together into something approaching a consensus, artistically and nationalistically."

Oil on board - The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, USA

Biography of John Ruskin

Childhood and early life.

An only child, Ruskin was born in 1819 in south London to affluent parents, John James Ruskin, a Scottish wine merchant, and Margaret Ruskin, the daughter of a pub proprietor. The young Ruskin spent his summers in the Scottish countryside and when he was four, the family moved to south London's Herne Hill, a rural area at the time. It was these early experiences that ignited his lifelong love of nature. He was educated at home, where he was influenced by his father's collection of watercolors and his mother's pious Protestantism. Ruskin recalled a rigorous daily practice of bible reading and interpretation, which was to provide an early foundation for his work in criticism. At the age of seven he began to write books and his father - ambitious for his son to find success - would pay him for his poems.

The family's wealth allowed them to travel extensively throughout the UK and Europe, visiting Italy, France, and Belgium. Ruskin was particularly taken by the picturesque landscape of the Lake District and his first publication was a poem entitled On Skiddaw and Derwent Water which appeared in the Spiritual Times in 1829. He also became fascinated by the Romantic poets Wordsworth, Byron, and Scott. Ruskin was an intelligent and articulate teenager. He collected and compiled a dictionary of minerals and he had three articles on geology published in the Magazine of Natural History when he was 15. He went on to study classics at Oxford University, where his mother followed him, insisting that she meet him for tea every day. He did well at university, but after a period of illness, he left in 1842, with only a double fourth degree (a classification lower than a third, awarded by Oxford until 1971) in classics and mathematics.

Mature Period

It is often forgotten that Ruskin was a talented artist in his own right, and he said the instinct he had to draw was akin to the instinct to eat and drink. He filled sketchbooks from an early age, and throughout his life produced volumes of exquisite sketches and watercolors of nature; blossoms, flowers, mountains, stones, clouds, minerals, and birds. His watercolors mimicked J.M.W. Turner's expressive style and he was most prolific in the period 1840-70, with fewer produced later in his life. He did not, however, exhibit his artwork professionally, instead he used his studies to record what he saw and assist with his writing. Although many of his images were never shared, he used some to illustrate his essays and books.

Modern Painters (1843)

When Ruskin was 24, he wrote the first volume of Modern Painters - Their Superiority in the Art of Landscape Painting to All the Ancient Masters , a hugely influential work that launched an assault on the artistic establishment. The book criticized the work of 17 th century painters such as Claude Lorrain , Nicolas Poussin , and Salvator Rosa. As an alternative, Ruskin promoted the accurate documentation of nature and he especially championed J.M.W. Turner , who was a controversial figure in the establishment at the time. Modern Painters questioned the arguments of Sir Joshua Reynolds and the rules which he had established at the Royal Academy. Many were appalled, but the passion with which Ruskin wrote won him fans and he was championed as a new voice in modern artistic thinking. He particularly found favor with contemporary writers of the time, including William Wordsworth, George Elliot, and Charlotte Brontë as well as with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood . Ruskin went on to publish four more volumes, with the last coming out in 1860. Modern Painters also found an eager readership in America, where artists felt it freed them. As artist John A. Parks said: "Art could now become both an aesthetic and a religious quest freed from the dominance of centuries of European painting. This was the magic brew that Ruskin had concocted and that American artists found utterly intoxicating."

The Stones of Venice (1851)

Ruskin was particularly enamored with the architecture of Venice and was vehemently opposed to restoration, so much so that he would climb scaffolding in the Italian city to argue with stonemasons. His convictions were immortalized in The Stones of Venice , a three-volume treatise on Venetian art and architecture, in which he expanded the ideas he had formulated in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), an extended essay in which he argued that the leading principles of architecture were sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory, and obedience. Within the Stones of Venice was a chapter On the Nature of Gothic , in which Ruskin proposed that architecture revealed the spiritual and moral state of the society that produced it. He admired the Christian society of the Middle Ages and its imperfections which represented the individual craftsman's autonomy and talent, but also that it was communal art, inspired by a love of God. It stood against the regularity and geometrical shapes of the Classical style that to Ruskin represented coldness, a need to control, and a "haughty aristocratic style". For Ruskin, Classical architecture represented a fall from healthy civilization.

Unto This Last (1862)

This work, although a move away from art criticism, was considered by many to be Ruskin's best. Unto This Last took on the thorny issue of capitalist economics, and formed an indictment of the dehumanization caused by the industrial revolution. Passionately written, the work was received with shock as he made a personal plea to his readers to help build a fairer society. He condemned the ugliness of industrialism and the impact commerce was having on the natural world. He also denounced society's dependence on child labor, appealing to employers to ask whether their own children would be asked to do such work.

Unto This Last alienated friends and professional acquaintances alike. Some considered his speech outmoded, others regarded him as self-righteous. One review said reading the book was like being "preached to death by a mad governess", while another stated "if we do not crush [Ruskin], his wild words will touch the springs of action in some hearts and before we are aware, a moral floodgate may fly open and drown us all." The impact of the work, however, cannot be underestimated and he influenced many founders of the British Labour Party as well as the economist John A Hobson. When Mahatma Gandhi read Unto This Last , it inspired him to become an activist, and he translated it into Gujarati so that it may be read by the working classes of India. Gandhi wrote: "I believe that I discovered some of my deepest convictions reflected in this great book of Ruskin and that is why it so captured me and made me transform my life."

The Marriage to Effie

In 1848 Ruskin married the beautiful Euphemia Gray (known as Effie), a family friend who was ten years his junior. It was a disaster as Ruskin failed to accommodate the young woman's interests or overcome the dominant presence of his own mother. One of the best-known stories about the marriage is that it was never consummated. Legend has it that Ruskin was unable to perform on his wedding night because he was so shocked by the revelation that his young wife had pubic hair, unlike the women in paintings he had grown up admiring. The story is most likely apocryphal, but Effie claimed her husband "had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening". This sentiment was echoed by Ruskin who stated that "It may be thought strange that I could abstain from a woman who to most people was so attractive. But though her face was beautiful, her person was not formed to excite passion. On the contrary, there were certain circumstances in her person which completely checked it". Ruskin's friend Clive Wilmer said: "The poor man had a bad marriage, but it takes two to make a bad marriage. He had faults, which one shouldn't pretend weren't there - he was very dogmatic...he could be quite arrogant - but he was extremely knowledgeable."

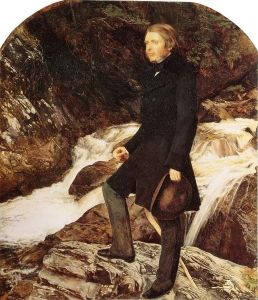

In 1852 Effie met John Everett Millais and modelled for one of his paintings, The Order of Release . Millais then accompanied the couple on a trip to Scotland to paint Ruskin. During this period Effie and he fell in love. Returning to London, Effie left Ruskin and filed for an annulment. Despite causing a major public scandal, in 1854 the marriage was annulled on the grounds of "incurable impotency". The following year Effie married Millais and they went onto to have eight children together. In 2014 the scandal was made into a movie, Effie Gray , starring Emma Thompson.

Around 1865 Ruskin fell in love with Rose La Touche (on who he based his 1865 book Sesame and Lillies ), a young pupil, to whom he proposed. Her parents refused permission after corresponding with Effie. The following year, Ruskin renewed his proposal when Rose turned 18 (by which time he was 47) and could legally make her own decision, but she, again, refused. Rose died in 1875, at the age of 27, reportedly of anorexia, and Ruskin was heartbroken. He was haunted by Rose's death, turning to spiritualism to contact her. During this period, he started to show the first signs of the serious psychological distress that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

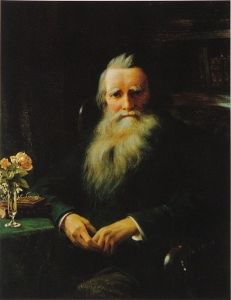

Late Years and Death

In 1869 Ruskin was made Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford. This was not Ruskin's first teaching role, he had been involved in education in a range of capacities from the 1850s and was a very popular lecturer. In 1871 he set up his own art school, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art which sought to challenge formal methods and rigid, mechanical teaching systems. He also promoted the virtues of public service and manual labor. Ruskin endowed the school with £5000 of his own money. In 1879 Ruskin resigned from Oxford, but resumed his Professorship in 1883, resigning again the following year, this was probably due to conflict with the University authorities, who refused to expand his Drawing School as well as his increasing ill health. During this period he continued to put his political thoughts into practice, writing the monthly magazine Fors Clavigera , aimed at "workmen and labourers" and founding the Guild of St George, a utopian society which encouraged traditional crafts and amassed a large collection of art, books, and historical objects. He also wrote a number of travel guides including Mornings in Florence (1875-77) and The Bible of Amiens (1880-85)

In 1871 he bought Brantwood, a house in the Lake District which stands today as a museum of Ruskin's work. He lived there for the rest of his life enjoying the simplicities of home decoration, gardening and baking. From the late-1870s he had bouts of deep depression and underwent episodes of crisis which may have been a symptom of bipolar disorder. He was cared for by his second cousin, Joan Severn, who inherited his estate after his death. In 1878 he became convinced that his beloved Rose had returned from the dead, crying out in delirium for "Rosie-Posie" and shouting "Everything white! Everything black!". He died from influenza at the age of 80 in 1900, leaving little money behind. He had inherited at least £120,000 from his father but had given most of it away.

The Legacy of John Ruskin

Ruskin's writing was responsible for shaping and promoting the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts Movement. His style of art criticism was groundbreaking and hugely influential to subsequent generations. As novelist Michael Bracewell writes: "Ruskin's passionate championing of particular artists paved the way for such great later critics as David Sylvester and Robert Hughes. Such erudition, clarity and richly opinionated rigor is sorely missed in contemporary art criticism." Ruskin was also respected by legendary writers including Marcel Proust, Charlotte Brontë. And Leo Tolstoy remarked after the critic's death: "John Ruskin was one of the most remarkable men not only of England and our time, but all countries and all time."

Beyond his writing and artistic talent, it was his radical ideas that really brought about change. As William Morris said: "He seemed to point out a new road on which others should travel" and Ruskin's social conscience was instrumental in improving society in Britain and abroad. He promoted women's education and carried out lectures to laborers which would go on to improve conditions for the working classes. He spent his own money setting up the Guild of St George which provided land where people could work cooperatively. The guild is now a charity for arts, crafts, and the rural economy. Furthermore, the introduction of garden cities have been attributed to Ruskin, and it was his love for the Lake District that ignited a drive to protect and conserve the landscape and sparked the foundation of the National Trust. His ideas also helped found the Welfare State in Britain - an institution that saw free health care for all, the introduction of a minimum wage and allowances for the vulnerable.

Ruskin continues to fascinate today, 200 years after his birth. As art historian Daisy Dunn notes: "Ruskin was a man of intense contradictions. Like a fish, he said, it is healthiest to swim against the stream. He described himself mostly as a Conservative, but many of his ideas were socialist in outlook. He believed in hierarchy but also that the rich had a responsibility to protect the poor." He has even been credited with foreseeing the horrors of climate change. In his book The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century he predicted "a period which will assuredly be recognized in future meteorological history as one of phenomena hitherto unrecorded in the courses of nature." As literary historian Marcus Waithe said: "Ruskin's dark premonition of atmospheric pollution...has been largely vindicated. Concerns about plastic pollution in our oceans likewise echo his fretful attention to the cleanliness of rivers and the purity of springs."

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on John Ruskin

- John Ruskin Our Pick By Tim Hilton

- John Ruskin: Artist and Observer By Christopher Baker

- Masters: John Ruskin and His Influence on American Art By John A. Parks

- Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud By Suzanne Fagence Cooper

- The Genius of John Ruskin: Selections from His Writings By John D. Rosenberg

- The Worlds of John Ruskin By Kevin Jackson

- Unto this last - 200 years of John Ruskin By Tara Contractor

- Modern Painters, Volume 1 By John Ruskin

- Praeterita - A memoir By John Ruskin

- The Stones of Venice By John Ruskin

- Unto This Last By John Ruskin

- Artists v critics, round one By Jonathan Jones / The Guardian / June 26, 2003

- Beguiled then bewildered: Ruskin's love-hate relationship with Turner Our Pick By Ben Luke / The Art Newspaper / February 6, 2019

- In praise of John Ruskin Our Pick By Michael Crowley / Spiked / September 6, 2019

- John Ruskin's marriage: what really happened By Michael Prodger / The Guardian / March 29, 2013

- Morbid Love By Philip Hoare / The Guardian / February 12, 2005

- 'Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin' Review: Going to Nature in His Own Fashion By Edward Rothstein / The Wall Street Journal / November 2, 2019

- Was Ruskin the most important man of the last 200 years? Our Pick By Daisy Dunn / BBC / February 8, 2019

- What to say about... John Ruskin The Guardian / March 24, 2002

- What was John Ruskin thinking on his unhappy wedding night? By Vanessa Thorpe / The Guardian / March 14, 2010

- 5 Ways John Ruskin Shaped the Art World Today By Redmond Bacon / Sleek Magazine / February 8, 2017

- A brief history of John Ruskin and Brantwood Coniston

- BBC Audio Documentary In Our Time - Melvyn Bragg on John Ruskin Our Pick

- John Ruskin & William Morris - An aesthetics documentary by Peter Fuller

- Ruskin at 200: The Art Critic as Word-Painter

- The First Ecologist: John Ruskin

- Written in Stone: Ruskin and Venice

Related Artists

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Sarah Ingram

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Kate Stephenson

English Literature Notes

Tuesday, july 9, 2013, analysis of an outstanding english essay "work" by john ruskin, no comments:, post a comment.

- Comments RSS

Here's a great place to put a random quote or random post title.

- English Drama (6)

- English Novel (6)

- English Poetry (8)

- English Prose (7)

“Work” By John Ruskin

9:37 AM | Filed Under English Prose | 0 Comments

Copyright 2008 White Space - WP Theme by Brian Gardner - Blogger Template by ThemeLib.com

Our use of cookies

We use necessary cookies to make our site work. We'd also like to set optional cookies to help us measure web traffic and report on campaigns.

We won't set optional cookies unless you enable them.

Cookie settings

The Complete Works of John Ruskin

From this page, you can download all or part of The Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin (1903-1912, eds. E.T Cook & A. Wedderburn) in PDF format.

To view or download the entire Library Edition or a specific volume, click on it in the list below. A PDF reader will be required.

Complete Works - every volume below as a single file portfolio pdf

- Volume I - Early Prose Writings

- Volume II - Poems

- Volumes III - VII - Modern Painters

- Volume VIII - The Seven Lamps of Architecture

- Volumes IX - XI - The Stones of Venice and Examples of the Architecture of Venice

- Volume XII - Lectures on Architecture and Painting (Edinburgh, 1853) with Other Papers (1844-1854)

- Volume XIII - Turner, The Harbours of England and Catalogues and Notes

- Volume XIV - Academy Notes, Notes on Prout and Hunt and Other Art Criticisms (1855-1888)

- Volume XV - The Elements of Drawing, The Elements of Perspective and The Laws of Fésole

- Volume XVI - "A Joy For Ever" and The Two Paths with letters on The Oxford Museum and various addresses (1856-1860)

- Volume XVII - Unto this Last, Munera Pulveris and Time and Tide with other writings on Political Economy (1860-1873)

- Volume XVIII - Sesame and Lilies, The Ethics of Dust and The Crown of Wild Olive with letters on Public Affairs (1859-1866)

- Volume XIX - The Cestus of Aglaia and The Queen of the Air with other papers and lectures on Art and Literature (1860-1870)

- Volume XX - Lectures on Art and Aratra Pentelici with lectures and notes on Greek Art and Mythology (1870)

- Volume XXI - The Ruskin Art Collection at Oxford: Catalogues, Notes and Instructions

- Volume XXII - Lectures on Landscape, Michael Angelo & Tintoret, The Eagle's Nest and Ariadne Florentina with notes for other Oxford lectures

- Volume XXIII - Val D'Arno, The Schools of Florence, Mornings in Florence and The Shepherd's Tower

- Volume XXIV - Giotto and his works in Padua, The Cavalli Monuments Verona, Guide to the Academy Venice and St Mark's Rest

- Volume XXV - Love's Meinie and Proserpina

- Volume XXVI - Deucalion and other studies in Rocks and Stones

- Volumes XXVII - XXIX - Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain

- Volume XXX - The Guild and Museum of St. George

- Volume XXXI - Bibliotheca Pastorum: The Economist of Xenophon, Rock Honeycomb, The Elements of Prosody and A Knight's Faith

- Volume XXXII - Studies of Peasant Life: The Story of Ida, Roadside Songs of Tuscany, Christ's Folk in the Apennine and Ulric the Farm Servant

- Volume XXXIII - The Bible of Amiens, Valle Crucis, The Art of England and The Pleasures of England

- Volume XXXIV - The Storm-cloud of the Nineteenth Century: On the Old Road, Arrows of the Chace and Ruskiniana

- Volume XXXV - Praeterita and Dilecta

- Volumes XXXVI - XXXVII - The Letters of John Ruskin (1827-1889)

- Volume XXXVIII - Bibliography, Catalogue of Ruskin's Drawings and Addenda et Corrigenda

- Volume XXXIX - General Index

Special thanks go to John Krug and Jen Shepherd (Lancaster University) for creating these PDFs.

5 Themes in the Works of John Ruskin

Tony Evans/Getty Images (cropped)

- Famous Architects

- An Introduction to Architecture

- Great Buildings

- Famous Houses

- Skyscrapers

- Tips For Homeowners

- Art & Artists

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Jackie-Craven-ThoughtCo-58eeac613df78cd3fc7a495c.jpg)

- Doctor of Arts, University of Albany, SUNY

- M.S., Literacy Education, University of Albany, SUNY

- B.A., English, Virginia Commonwealth University

We live in interesting technological times. As the 20th century turned into the 21st century, the Information Age took hold. Digital parametric design has changed the face of how architecture is practiced. Manufactured building materials are often synthetic. Some of today's critics caution against today's ubiquitous machine, that computer-aided design has become computer-driven design. Has artificial intelligence gone too far?

London-born John Ruskin (1819 to 1900) addressed similar questions in his time. Ruskin came of age during Britain's domination of what became known as the Industrial Revolution . Steam-powered machinery quickly and systematically created products that once had been hand-hewn. High-heating furnaces made hand-hammered wrought iron irrelevant to a new cast iron, easily molded into any shape without the need of the individual artist. Artificial perfection called cast-iron architecture was prefabricated and shipped around the world.

Ruskin's 19th-century cautionary criticisms are ones applicable to today's 21st-century world. In the following pages, explore some of the thoughts of this artist and social critic, in his own words. Although not an architect, John Ruskin influenced a generation of designers and continues to be on the must-read lists of today's architecture student.

Two of the best-known treatises in architecture were written by John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture , 1849, and The Stones of Venice , 1851.

Ruskin's Themes

Ruskin studied the architecture of northern Italy. He observed Verona's San Fermo, its arch being "wrought in fine stone, with a band of inlaid red brick, the whole chiseled and fitted with exquisite precision." * Ruskin noted a sameness in the Gothic palaces of Venice, but it was a sameness with a difference. Unlike today's Cape Cods in Suburbia, architectural details were not manufactured or prefabricated in the medieval town he sketched. Ruskin said:

"...the forms and mode of decoration of all the features were universally alike; not servilely alike, but fraternally; not with the sameness of coins cast from one mould, but with the likeness of the members of one family." — Section XLVI, Chapter VII Gothic Palaces, The Stones of Venice, Volume II

*Section XXXVI, Chapter VII

Rage Against the Machine

Throughout his life, Ruskin compared the industrialized English landscape with the great Gothic architecture of medieval cities. One can only imagine what Ruskin would say about today's engineered wood or vinyl siding. Ruskin said:

"It is only good for God to create without toil; that which man can create without toil is worthless: machine ornaments are no ornaments at all." — Appendix 17, The Stones of Venice, Volume I

Dehumanization of Man in an Industrial Age

Who today is encouraged to think? Ruskin acknowledged that a man can be trained to produce perfect, quickly made products, just like a machine can do. But do we want humanity to become mechanical beings? How dangerous is thinking in our own commerce and industry today? Ruskin said:

"Understand this clearly: You can teach a man to draw a straight line, and to cut one; to strike a curved line, and to carve it; and to copy and carve any number of given lines or forms, with admirable speed and perfect precision; and you find his work perfect of its kind: but if you ask him to think about any of those forms, to consider if he cannot find any better in his own head, he stops; his execution becomes hesitating; he thinks, and ten to one he thinks wrong; ten to one he makes a mistake in the first touch he gives to his work as a thinking being. But you have made a man of him for all that. He was only a machine before, an animated tool." — Section XI, Chapter VI - The Nature of Gothic, The Stones of Venice, Volume II

What is architecture?

Answering the question " What is architecture? " is not an easy task. John Ruskin spent a lifetime expressing his own opinion, defining the built environment in human terms. Ruskin said:

"Architecture is the art which so disposes and adorns the edifices raised by man for whatsoever uses, that the sight of them contributes to his mental health, power and pleasure." — Section I, Chapter I The Lamp of Sacrifice, The Seven Lamps of Architecture

Respecting the Environment, Natural Forms, and Local Materials

Today's green architecture and green design is an afterthought for some developers. To John Ruskin, natural forms are all that should be. Ruskin said:

"...for whatever is in architecture fair or beautiful, is imitated from natural forms....An architect should live as little in cities as a painter. Send him to our hills, and let him study there what nature understands by a buttress, and what by a dome." — Sections II and XXIV, Chapter III The Lamp of Power, The Seven Lamps of Architecture

Ruskin in Verona: Artistry and Honesty of the Hand-Crafted

As a young man in 1849, Ruskin railed against cast-iron ornamentation in the "Lamp of Truth" chapter of one of his most important books, The Seven Lamps of Architecture . How did Ruskin come to these beliefs?

As a youth, John Ruskin traveled with his family to mainland Europe, a custom he continued throughout his adult life. Travel was a time to observe architecture, sketch, and paint, and continue to write. While studying the northern Italian cities of Venice and Verona, Ruskin realized that the beauty he saw in architecture was created by man's hand. Ruskin said:

"The iron is always wrought, not cast, beaten first into thin leaves, and then cut either into strips or bands, two or three inches broad, which are bent into various curves to form the sides of the balcony, or else into actual leafage, sweeping and free, like the leaves of nature, with which it is richly decorated. There is no end to the variety of design, no limit to the lightness and flow of the forms, which the workman can produce out of iron treated in this manner; and it is very nearly as impossible for any metal-work, so handled, to be poor, or ignoble in effect, as it is for cast metal-work to be otherwise." — Section XXII, Chapter VII Gothic Palaces, The Stones of Venice Volume II

Ruskin's praise of the hand-crafted not only influenced the Arts & Crafts Movement but also continues to popularize Craftsman-style houses and furniture like Stickley.

Ruskin's Rage Against the Machine

John Ruskin lived and wrote during the explosive popularity of cast-iron architecture , a manufactured world he despised. As a boy, he had sketched the Piazza delle Erbe in Verona, shown here, remembering the beauty of the wrought iron and the carved stone balconies. The stone balustrade and the chiseled gods atop the Palazzo Maffei were worthy details to Ruskin, architecture, and ornamentation made by man and not by machine.

"For it is not the material, but the absence of the human labor, which makes the thing worthless," Ruskin wrote in "The Lamp of Truth." His most common examples were these:

Ruskin on Cast Iron

"But I believe no cause to have been more active in the degradation of our natural feeling for beauty, than the constant use of cast iron ornaments. The common iron work of the middle ages was as simple as it was effective, composed of leafage cut flat out of sheet iron, and twisted at the workman's will. No ornaments, on the contrary, are so cold, clumsy, and vulgar, so essentially incapable of a fine line, or shadow, as those of cast iron....there is no hope of the progress of the arts of any nation which indulges in these vulgar and cheap substitutes for real decoration." — Section XX, Chapter II The Lamp of Truth, The Seven Lamps of Architecture

Ruskin on Glass

"Our modern glass is exquisitely clear in its substance, true in its form, accurate in its cutting. We are proud of this. We ought to be ashamed of it. The old Venice glass was muddy, inaccurate in all its forms, and clumsily cut, if at all. And the old Venetian was justly proud of it. For there is this difference between the English and Venetian workman, that the former thinks only of accurately matching his patterns, and getting his curves perfectly true and his edges perfectly sharp, and becomes a mere machine for rounding curves and sharpening edges, while the old Venetian cared not a whit whether his edges were sharp or not, but he invented a new design for every glass that he made, and never moulded a handle or a lip without a new fancy in it. And therefore, though some Venetian glass is ugly and clumsy enough, when made by clumsy and uninventive workmen, other Venetian glass is so lovely in its forms that no price is too great for it; and we never see the same form in it twice. Now you cannot have the finish and the varied form too. If the workman is thinking about his edges, he cannot be thinking of his design; if of his design, he cannot think of his edges. Choose whether you will pay for the lovely form or the perfect finish, and choose at the same moment whether you will make the worker a man or a grindstone." — Section XX, Chapter VI The Nature of Gothic, The Stones of Venice Volume II

The writings of critic John Ruskin influenced social and labor movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. Ruskin did not live to see Henry Ford's Assembly Line , but he predicted that untethered mechanization would lead to labor specialization. In our own day, we wonder if an architect's creativity and ingenuity would suffer if asked to perform only one digital task, whether in a studio with a computer or on a project site with a laser beam. Ruskin said:

"We have much studied and much perfected, of late, the great civilized invention of the division of labor; only we give it a false name. It is not, truly speaking, the labor that is divided; but the men: — Divided into mere segments of men — broken into small fragments and crumbs of life; so that all the little piece of intelligence that is left in a man is not enough to make a pin, or a nail, but exhausts itself in making the point of a pin, or the head of a nail. Now it is a good and desirable thing, truly, to make many pins in a day; but if we could only see with what crystal sand their points were polished — sand of human soul, much to be magnified before it can be discerned for what it is — we should think there might be some loss in it also. And the great cry that rises from all our manufacturing cities, louder than their furnace blast, is all in very deed for this — that we manufacture everything there except men; we blanch cotton, and strengthen steel, and refine sugar, and shape pottery; but to brighten, to strengthen, to refine, or to form a single living spirit, never enters into our estimate of advantages."—Section XVI, Chapter VI The Nature of Gothic, The Stones of Venice, Volume II

When in his 50s and 60s, John Ruskin continued his social writings in monthly newsletters collectively called Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain . See the Ruskin Library News to download a PDF file of Ruskin's voluminous pamphlets written between 1871 and 1884. During this time period, Ruskin also established the Guild of St George , an experimental Utopian society similar to the American communes established by the Transcendentalists in the 1800s. This "alternative to industrial capitalism" might be known today as a "Hippie Commune."

Source: Background , Guild of St George website [accessed February 9, 2015]

What is Architecture: Ruskin's Lamp of Memory

In today's throw-away society, do we build buildings to last through the ages or is cost too much a factor? Can we create lasting designs and build with natural materials that future generations will enjoy? Is today's Blob Architecture beautifully crafted digital art, or will it seem just too silly in years hence?

John Ruskin continually defined architecture in his writings. More specifically, he wrote that we cannot remember without it, that architecture is memory . Ruskin said:

"For, indeed, the greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, or in its gold. Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity....it is in that golden stain of time, that we are to look for the real light, and color, and preciousness of architecture...." — Section X, The Lamp of Memory, The Seven Lamps of Architecture

John Ruskin's Legacy

As today's architect sits at his computer machine, dragging and dropping design lines as easily as (or easier than) skipping stones on Britain's Coniston Water, the 19th-century writings of John Ruskin make us stop and think — is this design architecture? And when any critic-philosopher allows us to partake in the human privilege of thought, his legacy is established. Ruskin lives on.

Ruskin's Legacy

- Created new interest in reviving Gothic architecture

- Influenced the Arts & Crafts Movement and hand-crafted workmanship

- Established interest in social reforms and labor movements from his writings on man's dehumanization in an Industrial Age

John Ruskin spent his final 28 years at Brantwood , overlooking the Lake District's Coniston. Some say he went mad or fell into dementia; many say his later writings show signs of a troubled man. While his personal life has titillated some 21st-century film-goers, his genius has influenced the more serious-minded for more than a century. Ruskin died in 1900 at his home, which is now a museum open to visitors of Cumbria .

If John Ruskin's writings do not appeal to a modern audience, his personal life certainly does. His character appears in a film about British painter J.M.W. Turner and, also, a film about his wife, Effie Gray.

- Mr. Turner , a film directed by Mike Leigh (2014)

- Effie Gray , a film directed by Richard Laxton (2014)

- " John Ruskin: Mike Leigh and Emma Thompson have got him all wrong " by Philip Hoare, The Guardian , October 7, 2014

- Marriage of Inconvenience by Robert Brownell (2013)

- Biography and Influence of John Ruskin, Writer and Philosopher

- Biography of William Morris, Leader of the Arts and Crafts Movement

- Biography of Philip Webb

- Maya Lin. The Architect, Sculptor, and Artist

- Eero Saarinen Portfolio of Selected Works

- Henry Hobson Richardson, The All-American Architect

- Interior Design - Looking Inside Frank Lloyd Wright

- Sir Christopher Wren, the Man Who Rebuilt London After the Fire

- Designing for Disney

- 15 Important African American Architects

- Florence Knoll, Designer of the Corporate Board Room

- I.M. Pei, Architect of Glass Geometries

- Frank Lloyd Wright Architecture by City and State

- Biography of Le Corbusier, Leader of the International Style

- Biography of John Augustus Roebling, Man of Iron

- Louis I. Kahn, a Premier Modernist Architect

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

John Ruskin summary

John Ruskin , (born Feb. 8, 1819, London, Eng.—died Jan. 20, 1900, Coniston, Lancashire), English art critic. Born into a wealthy family, Ruskin was largely educated at home. He was a gifted painter, but the best of his talent went into his writing. His multivolume Modern Painters (1843–60), planned as a defense of painter J.M.W. Turner , expanded to become a general survey of art. In Turner he saw “truth to nature” in landscape painting, and he went on to find the same truthfulness in Gothic architecture. His other writings include The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1851–53). He was also a defender of the Pre-Raphaelites . In 1869 he was elected Oxford’s first Slade professor of fine art; he resigned in 1879 after James McNeill Whistler won a libel suit against him. In later years he used his inherited wealth to promote idealistic social causes, but his powerful rhetoric, which still contained striking insights, became marred by bigotry and occasional incoherence. Ruskin remains the preeminent art critic of 19th-century Britain.

The Writings of John Ruskin: A Partial List

[ Victorian Web Home —> Authors —> John Ruskin —> Works —> Leading Questions ]

[ Disponible en español ]

A Quotation from Ruskin? "There is hardly anything in the world that someone cannot make a little worse and sell a little cheaper, and the people who consider price alone are that person's lawful prey."

| , 1836 ", 1836 , 1837 , 1841 of the American Southwest. " (Sawyer) (Sawyer) This Last, 1860 | and ) (discussions) — ) — compared to Praeteria (chapter in the Oxford "Past Masters" volume on Ruskin allows word searches the complete texts of The King of the Golden River, Sesame and Lilies, and The Stones of Venice |

Last modified 2 June 2023

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Work by John Ruskin Summary. Ruskin delivered his lecture "Work" before the working men's institute, at Camber well. In this speech he addresses the working people there at the institution of working men. This speech is a socio-economic criticism on the contemporary life of England. In the very beginning of his speech he tries to bring ...

Between those who work and those who play. Between those who produce the means of life, and those who consume them. Between those who work with the head, and those who work with the hand. Between those who work wisely, and who work foolishly. For easier memory, let us say we are going to oppose in our examination, --.

4 INTRODUCTION. Maremma,— notbyCampagnatomb,— notbythe sand-islesoftheTorcellanshore,— astheslowsteal- ingofaspectsofreckless,indolent,animalneglect ...

Summary of John Ruskin. An incredibly influential figure, who inspired people as diverse as Mahatma Ghandi, Leo Tolstoy, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ruskin was a complex, intense, and incredibly articulate man.Although he is best known as an art critic and patron, he was a true polymath and was also a talented watercolorist, an engaging teacher, a respected geologist, and a campaigner for ...

John Ruskin (1819 -1900) was an English art critic and social thinker, also remembered as a poet and artist. He wrote a number of essays on art and architecture that became extremely influential in the Victorian era. He takes material for his lecture "Work" from the existing economic revolution which is generally referred to as "Industrial ...

John Ruskin (1819 -1900) was an English art critic and social thinker, also remembered as a poet and artist. He wrote a number of essays on art and architecture that became extremely influential in the Victorian era. He takes material for his lecture "Work" from the existing economic revolution which is generally referred to as ...

First published: 1843-1860. Type of work: Art history and criticism. The greatness of a work of art is measured by its careful observation of the moral and spiritual superiority of the natural or ...

Ruskin chosen for their beauty, or for their bearing on some special theme: it is believed that no collection has existed which aimed to present a suggestive summary of all the' varying phases of his work, and to initiate the serious student into the most valuable portions of his thought.

Ask the Chatbot a Question Ask the Chatbot a Question John Ruskin (born February 8, 1819, London, England—died January 20, 1900, Coniston, Lancashire) was an English critic of art, architecture, and society who was a gifted painter, a distinctive prose stylist, and an important example of the Victorian Sage, or Prophet: a writer of polemical prose who seeks to cause widespread cultural and ...

The Raven (History and Summary) Quiz. Frankenstein Overview Quiz. "The Summer of the Beautiful White Horse" by William Saroyan Quiz. The Black Cat Overview Quiz. 1984 Part 1 Chapter 6 and 7 Quiz ...

From this page, you can download all or part of The Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin (1903-1912, eds. E.T Cook & A. Wedderburn) in PDF format. To view or download the entire Library Edition or a specific volume, click on it in the list below. A PDF reader will be required. Special thanks go to John Krug and Jen Shepherd (Lancaster ...

Although not an architect, John Ruskin influenced a generation of designers and continues to be on the must-read lists of today's architecture student. Two of the best-known treatises in architecture were written by John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849, and The Stones of Venice, 1851. The themes in the writings of John Ruskin ...

The Seven Principles. 1. Beauty. In the beauty section of the essay, Ruskin relies heavily on the designs seen in nature and points out that architecture should stem from the natural environment ...

John Ruskin: The Later Years. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000. Begins in 1859, when Ruskin is already famous. Describes his obsession with ten-year-old Rose La Touche as well as his ...

Ruskin, detail of an oil painting by Sir John Everett Millais, 1853-54; in a private collection. John Ruskin, (born Feb. 8, 1819, London, Eng.—died Jan. 20, 1900, Coniston, Lancashire), English art critic. Born into a wealthy family, Ruskin was largely educated at home. He was a gifted painter, but the best of his talent went into his writing.

Summary. Modern Painters is the work that gained for Ruskin the recognition of the English world of letters and creativity. Published in 1843, when Ruskin was twenty-four, it represents the young ...

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 - 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art historian, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era.He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and political economy. Ruskin was heavily engaged by the work of Viollet-le-Duc which he taught to all his pupils including William Morris ...

The Symbolical Grotesque — theories of allegory, artist, and imagination. Imitation, the Languages of Art, and Nature's Infinite Variety. Pathetic Fallacy. Aesthetic Theories. Ruskin's refutation of "False Opinions Held concerning Beauty". Typical Beauty. Vital Beauty. Sublimity. The Picturesque.