Dissertations and major projects

- Planning your dissertation

- Introduction

Doing the research

Methodology, thinking about structure, working with your supervisor.

- Managing your data

- Writing up your dissertation

Useful links for dissertations and major projects

- Study Advice Helping students to achieve study success with guides, video tutorials, seminars and appointments.

- Maths Support A guide to Maths Support resources which may help if you're finding any mathematical or statistical topic difficult during the transition to University study.

- Academic writing LibGuide Expert guidance on punctuation, grammar, writing style and proof-reading.

- Guide to citing references Includes guidance on why, when and how to use references correctly in your academic writing.

- The Final Chapter An excellent guide from the University of Leeds on all aspects of research projects

- Royal Literary Fund: Writing a Literature Review A guide to writing literature reviews from the Royal Literary Fund

- Academic Phrasebank Use this site for examples of linking phrases and ways to refer to sources.

The research process for a dissertation or project is substantial and takes time. You will need to think about what you have to find out in order to answer your research question, and where and when you can find this information. As you gather your research, keep returning to your research question to check what you are doing is relevant.

This page gives advice on keeping on track during your research by using your plan, your method or research process, your structure, and your supervisor.

The kinds of research you will need to do will depend on your research question. You will usually need to survey existing literature to get an overview of the knowledge that has been gained so far on the topic; this will inform your own research and your interpretations. You may also decide to do:

- primary research (conducting your own experiments, surveys etc to gain new knowledge)

- secondary research (collating knowledge from other people's research to produce a new synthesis).

You may need to do either or both.

Primary research

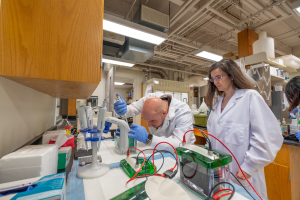

If you are doing qualitative or quantitative research, or experiments, start on these as soon as you can. Gathering data takes a lot of time. People are often too busy to participate in interviews or fill out questionnaires and you might need to find extra participants to make up your sample. Scientific experiments may take longer than you anticipate especially if they require ethical clearance, special equipment, or learning new methods.

- Design and plan your data collection methods – check them with your supervisor and see if they fit with your methodology.

- Identify and plan for any ethical issues with collecting your data.

- Do a test or pilot questionnaire as soon as possible so you can make changes if necessary.

- Identify your sample size and control groups.

- Have a contingency plan if not everyone is willing to participate.

- Keep good records – number and store any evidence – don't throw anything out until you graduate! See our advice on Managing your data in this guide for more suggestions.

The key to effective secondary research is to keep it under control, and to take an approach which will make your reading and your notes meaningful first time round.

- Start small with one main text and build up.

- Once you have an overview, formulate some sub-questions which will help answer your main dissertation question.

- Look for the answers to these questions.

- Do more reading to fill in the gaps.

- Keep thinking, and analysing the relevance of the information as you go along.

- But be aware of your work schedule – you can't read everything, so be selective.

If you need help, consult your Academic Liaison Librarian - they may know about materials you hadn't thought of.

- Literature searching A guide to finding articles, books and other materials on your subject. Includes tips on constructing a comprehensive search using search operators (AND/OR), truncation and wildcards.

- Doing your literature search videos - University of Reading Two short videos from the Library on planning and doing a literature search

- Doing your literature review video Watch this brief video tutorial for guidance on writing your literature review.

- Doing your literature review transcript Read the transcript.

- Contact your Academic Liaison Librarian

Methodology means being aware of the way in which you do something and being able to justify why you did it that way. Each academic discipline has a number of different sets of methods for conducting research.

For example: One method of conducting qualitative research is semi-structured interviews, another method is case studies – each are appropriate for finding different levels and types of information.

The method you choose will be the model for how you go about your research:

- Why is the method you chose the most appropriate way of finding an answer to your research question?

- Are there any other methods you might have used…why didn't you choose them?

- Throughout your dissertation be aware of the decisions you make and note them down explaining why you made them:

- Did you change your plans when you encountered a problem?

- Did you have to adjust sample size, questions, approach?

This awareness of why you did your research in a certain way and your ability to explain and justify these choices is a vital part of your dissertation.

Do bear in mind that no structure, title or question is set in stone until you submit your completed work. If you find a more interesting or productive way to discuss your topic, don't be afraid to change your structure - providing you have time to do any extra work.

- Structuring your dissertation (video) Watch this brief video tutorial for more on the topic.

- Structuring your dissertation (transcript) Read the transcript.

- Have some specific questions to ask your supervisor: These can be general like "How can I narrow down my question?" or more detailed such as "Am I interpreting this result correctly?"

- If you are unsure of an idea or approach, don't be afraid to talk it through with your supervisor – that's what they're there for! Just explaining it to someone else can help sort out your own thinking.

- It is easier for supervisors to give advice on a specific piece of work, so bring your research proposal, or chapter draft, to the meetings – your supervisor might not have time to read it all, so highlight places you'd like feedback on.

It's worth taking the advice of your supervisor seriously. You may have a strong idea of what you want to do in your dissertation, but your supervisor has academic experience and often knows what will and won't work. If you explain your ideas and are polite and enthusiastic, your supervisor can be a great sounding board and source of expert information.

|

In your first meeting with your supervisor, find out about frequency and times of supervisions. Check whether they mind being contacted by email, and if they will be away at any time during your project. |

- << Previous: Planning your dissertation

- Next: Managing your data >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 2:41 PM

- URL: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/dissertations

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="how to research for a dissertation"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Guide to writing your thesis/dissertation, definition of dissertation and thesis.

The dissertation or thesis is a scholarly treatise that substantiates a specific point of view as a result of original research that is conducted by students during their graduate study. At Cornell, the thesis is a requirement for the receipt of the M.A. and M.S. degrees and some professional master’s degrees. The dissertation is a requirement of the Ph.D. degree.

Formatting Requirement and Standards

The Graduate School sets the minimum format for your thesis or dissertation, while you, your special committee, and your advisor/chair decide upon the content and length. Grammar, punctuation, spelling, and other mechanical issues are your sole responsibility. Generally, the thesis and dissertation should conform to the standards of leading academic journals in your field. The Graduate School does not monitor the thesis or dissertation for mechanics, content, or style.

“Papers Option” Dissertation or Thesis

A “papers option” is available only to students in certain fields, which are listed on the Fields Permitting the Use of Papers Option page , or by approved petition. If you choose the papers option, your dissertation or thesis is organized as a series of relatively independent chapters or papers that you have submitted or will be submitting to journals in the field. You must be the only author or the first author of the papers to be used in the dissertation. The papers-option dissertation or thesis must meet all format and submission requirements, and a singular referencing convention must be used throughout.

ProQuest Electronic Submissions

The dissertation and thesis become permanent records of your original research, and in the case of doctoral research, the Graduate School requires publication of the dissertation and abstract in its original form. All Cornell master’s theses and doctoral dissertations require an electronic submission through ProQuest, which fills orders for paper or digital copies of the thesis and dissertation and makes a digital version available online via their subscription database, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses . For master’s theses, only the abstract is available. ProQuest provides worldwide distribution of your work from the master copy. You retain control over your dissertation and are free to grant publishing rights as you see fit. The formatting requirements contained in this guide meet all ProQuest specifications.

Copies of Dissertation and Thesis

Copies of Ph.D. dissertations and master’s theses are also uploaded in PDF format to the Cornell Library Repository, eCommons . A print copy of each master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation is submitted to Cornell University Library by ProQuest.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Table of Contents

Dissertation

Definition:

Dissertation is a lengthy and detailed academic document that presents the results of original research on a specific topic or question. It is usually required as a final project for a doctoral degree or a master’s degree.

Dissertation Meaning in Research

In Research , a dissertation refers to a substantial research project that students undertake in order to obtain an advanced degree such as a Ph.D. or a Master’s degree.

Dissertation typically involves the exploration of a particular research question or topic in-depth, and it requires students to conduct original research, analyze data, and present their findings in a scholarly manner. It is often the culmination of years of study and represents a significant contribution to the academic field.

Types of Dissertation

Types of Dissertation are as follows:

Empirical Dissertation

An empirical dissertation is a research study that uses primary data collected through surveys, experiments, or observations. It typically follows a quantitative research approach and uses statistical methods to analyze the data.

Non-Empirical Dissertation

A non-empirical dissertation is based on secondary sources, such as books, articles, and online resources. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as content analysis or discourse analysis.

Narrative Dissertation

A narrative dissertation is a personal account of the researcher’s experience or journey. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, focus groups, or ethnography.

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review is a comprehensive analysis of existing research on a specific topic. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as meta-analysis or thematic analysis.

Case Study Dissertation

A case study dissertation is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or organization. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, observations, or document analysis.

Mixed-Methods Dissertation

A mixed-methods dissertation combines both quantitative and qualitative research approaches to gather and analyze data. It typically uses methods such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as statistical analysis.

How to Write a Dissertation

Here are some general steps to help guide you through the process of writing a dissertation:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that you are passionate about and that is relevant to your field of study. It should be specific enough to allow for in-depth research but broad enough to be interesting and engaging.

- Conduct research : Conduct thorough research on your chosen topic, utilizing a variety of sources, including books, academic journals, and online databases. Take detailed notes and organize your information in a way that makes sense to you.

- Create an outline : Develop an outline that will serve as a roadmap for your dissertation. The outline should include the introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Write the introduction: The introduction should provide a brief overview of your topic, the research questions, and the significance of the study. It should also include a clear thesis statement that states your main argument.

- Write the literature review: The literature review should provide a comprehensive analysis of existing research on your topic. It should identify gaps in the research and explain how your study will fill those gaps.

- Write the methodology: The methodology section should explain the research methods you used to collect and analyze data. It should also include a discussion of any limitations or weaknesses in your approach.

- Write the results: The results section should present the findings of your research in a clear and organized manner. Use charts, graphs, and tables to help illustrate your data.

- Write the discussion: The discussion section should interpret your results and explain their significance. It should also address any limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research.

- Write the conclusion: The conclusion should summarize your main findings and restate your thesis statement. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

- Edit and revise: Once you have completed a draft of your dissertation, review it carefully to ensure that it is well-organized, clear, and free of errors. Make any necessary revisions and edits before submitting it to your advisor for review.

Dissertation Format

The format of a dissertation may vary depending on the institution and field of study, but generally, it follows a similar structure:

- Title Page: This includes the title of the dissertation, the author’s name, and the date of submission.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the dissertation’s purpose, methods, and findings.

- Table of Contents: A list of the main sections and subsections of the dissertation, along with their page numbers.

- Introduction : A statement of the problem or research question, a brief overview of the literature, and an explanation of the significance of the study.

- Literature Review : A comprehensive review of the literature relevant to the research question or problem.

- Methodology : A description of the methods used to conduct the research, including data collection and analysis procedures.

- Results : A presentation of the findings of the research, including tables, charts, and graphs.

- Discussion : A discussion of the implications of the findings, their significance in the context of the literature, and limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : A summary of the main points of the study and their implications for future research.

- References : A list of all sources cited in the dissertation.

- Appendices : Additional materials that support the research, such as data tables, charts, or transcripts.

Dissertation Outline

Dissertation Outline is as follows:

Title Page:

- Title of dissertation

- Author name

- Institutional affiliation

- Date of submission

- Brief summary of the dissertation’s research problem, objectives, methods, findings, and implications

- Usually around 250-300 words

Table of Contents:

- List of chapters and sections in the dissertation, with page numbers for each

I. Introduction

- Background and context of the research

- Research problem and objectives

- Significance of the research

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing literature on the research topic

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Theoretical framework and concepts

III. Methodology

- Research design and methods used

- Data collection and analysis techniques

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation and analysis of data collected

- Findings and outcomes of the research

- Interpretation of the results

V. Discussion

- Discussion of the results in relation to the research problem and objectives

- Evaluation of the research outcomes and implications

- Suggestions for future research

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of the research findings and outcomes

- Implications for the research topic and field

- Limitations and recommendations for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the dissertation

VIII. Appendices

- Additional materials that support the research, such as tables, figures, or questionnaires.

Example of Dissertation

Here is an example Dissertation for students:

Title : Exploring the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Achievement and Well-being among College Students

This dissertation aims to investigate the impact of mindfulness meditation on the academic achievement and well-being of college students. Mindfulness meditation has gained popularity as a technique for reducing stress and enhancing mental health, but its effects on academic performance have not been extensively studied. Using a randomized controlled trial design, the study will compare the academic performance and well-being of college students who practice mindfulness meditation with those who do not. The study will also examine the moderating role of personality traits and demographic factors on the effects of mindfulness meditation.

Chapter Outline:

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Background and rationale for the study

- Research questions and objectives

- Significance of the study

- Overview of the dissertation structure

Chapter 2: Literature Review

- Definition and conceptualization of mindfulness meditation

- Theoretical framework of mindfulness meditation

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and academic achievement

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and well-being

- The role of personality and demographic factors in the effects of mindfulness meditation

Chapter 3: Methodology

- Research design and hypothesis

- Participants and sampling method

- Intervention and procedure

- Measures and instruments

- Data analysis method

Chapter 4: Results

- Descriptive statistics and data screening

- Analysis of main effects

- Analysis of moderating effects

- Post-hoc analyses and sensitivity tests

Chapter 5: Discussion

- Summary of findings

- Implications for theory and practice

- Limitations and directions for future research

- Conclusion and contribution to the literature

Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Recap of the research questions and objectives

- Summary of the key findings

- Contribution to the literature and practice

- Implications for policy and practice

- Final thoughts and recommendations.

References :

List of all the sources cited in the dissertation

Appendices :

Additional materials such as the survey questionnaire, interview guide, and consent forms.

Note : This is just an example and the structure of a dissertation may vary depending on the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the institution or the supervisor.

How Long is a Dissertation

The length of a dissertation can vary depending on the field of study, the level of degree being pursued, and the specific requirements of the institution. Generally, a dissertation for a doctoral degree can range from 80,000 to 100,000 words, while a dissertation for a master’s degree may be shorter, typically ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 words. However, it is important to note that these are general guidelines and the actual length of a dissertation can vary widely depending on the specific requirements of the program and the research topic being studied. It is always best to consult with your academic advisor or the guidelines provided by your institution for more specific information on dissertation length.

Applications of Dissertation

Here are some applications of a dissertation:

- Advancing the Field: Dissertations often include new research or a new perspective on existing research, which can help to advance the field. The results of a dissertation can be used by other researchers to build upon or challenge existing knowledge, leading to further advancements in the field.

- Career Advancement: Completing a dissertation demonstrates a high level of expertise in a particular field, which can lead to career advancement opportunities. For example, having a PhD can open doors to higher-paying jobs in academia, research institutions, or the private sector.

- Publishing Opportunities: Dissertations can be published as books or journal articles, which can help to increase the visibility and credibility of the author’s research.

- Personal Growth: The process of writing a dissertation involves a significant amount of research, analysis, and critical thinking. This can help students to develop important skills, such as time management, problem-solving, and communication, which can be valuable in both their personal and professional lives.

- Policy Implications: The findings of a dissertation can have policy implications, particularly in fields such as public health, education, and social sciences. Policymakers can use the research to inform decision-making and improve outcomes for the population.

When to Write a Dissertation

Here are some situations where writing a dissertation may be necessary:

- Pursuing a Doctoral Degree: Writing a dissertation is usually a requirement for earning a doctoral degree, so if you are interested in pursuing a doctorate, you will likely need to write a dissertation.

- Conducting Original Research : Dissertations require students to conduct original research on a specific topic. If you are interested in conducting original research on a topic, writing a dissertation may be the best way to do so.

- Advancing Your Career: Some professions, such as academia and research, may require individuals to have a doctoral degree. Writing a dissertation can help you advance your career by demonstrating your expertise in a particular area.

- Contributing to Knowledge: Dissertations are often based on original research that can contribute to the knowledge base of a field. If you are passionate about advancing knowledge in a particular area, writing a dissertation can help you achieve that goal.

- Meeting Academic Requirements : If you are a graduate student, writing a dissertation may be a requirement for completing your program. Be sure to check with your academic advisor to determine if this is the case for you.

Purpose of Dissertation

some common purposes of a dissertation include:

- To contribute to the knowledge in a particular field : A dissertation is often the culmination of years of research and study, and it should make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field.

- To demonstrate mastery of a subject: A dissertation requires extensive research, analysis, and writing, and completing one demonstrates a student’s mastery of their subject area.

- To develop critical thinking and research skills : A dissertation requires students to think critically about their research question, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on evidence. These skills are valuable not only in academia but also in many professional fields.

- To demonstrate academic integrity: A dissertation must be conducted and written in accordance with rigorous academic standards, including ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent, protecting the privacy of participants, and avoiding plagiarism.

- To prepare for an academic career: Completing a dissertation is often a requirement for obtaining a PhD and pursuing a career in academia. It can demonstrate to potential employers that the student has the necessary skills and experience to conduct original research and make meaningful contributions to their field.

- To develop writing and communication skills: A dissertation requires a significant amount of writing and communication skills to convey complex ideas and research findings in a clear and concise manner. This skill set can be valuable in various professional fields.

- To demonstrate independence and initiative: A dissertation requires students to work independently and take initiative in developing their research question, designing their study, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. This demonstrates to potential employers or academic institutions that the student is capable of independent research and taking initiative in their work.

- To contribute to policy or practice: Some dissertations may have a practical application, such as informing policy decisions or improving practices in a particular field. These dissertations can have a significant impact on society, and their findings may be used to improve the lives of individuals or communities.

- To pursue personal interests: Some students may choose to pursue a dissertation topic that aligns with their personal interests or passions, providing them with the opportunity to delve deeper into a topic that they find personally meaningful.

Advantage of Dissertation

Some advantages of writing a dissertation include:

- Developing research and analytical skills: The process of writing a dissertation involves conducting extensive research, analyzing data, and presenting findings in a clear and coherent manner. This process can help students develop important research and analytical skills that can be useful in their future careers.

- Demonstrating expertise in a subject: Writing a dissertation allows students to demonstrate their expertise in a particular subject area. It can help establish their credibility as a knowledgeable and competent professional in their field.

- Contributing to the academic community: A well-written dissertation can contribute new knowledge to the academic community and potentially inform future research in the field.

- Improving writing and communication skills : Writing a dissertation requires students to write and present their research in a clear and concise manner. This can help improve their writing and communication skills, which are essential for success in many professions.

- Increasing job opportunities: Completing a dissertation can increase job opportunities in certain fields, particularly in academia and research-based positions.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing...

Future Research – Thesis Guide

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Research Approach – Types Methods and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

15 Steps to Good Research

- Define and articulate a research question (formulate a research hypothesis). How to Write a Thesis Statement (Indiana University)

- Identify possible sources of information in many types and formats. Georgetown University Library's Research & Course Guides

- Judge the scope of the project.

- Reevaluate the research question based on the nature and extent of information available and the parameters of the research project.

- Select the most appropriate investigative methods (surveys, interviews, experiments) and research tools (periodical indexes, databases, websites).

- Plan the research project. Writing Anxiety (UNC-Chapel Hill) Strategies for Academic Writing (SUNY Empire State College)

- Retrieve information using a variety of methods (draw on a repertoire of skills).

- Refine the search strategy as necessary.

- Write and organize useful notes and keep track of sources. Taking Notes from Research Reading (University of Toronto) Use a citation manager: Zotero or Refworks

- Evaluate sources using appropriate criteria. Evaluating Internet Sources

- Synthesize, analyze and integrate information sources and prior knowledge. Georgetown University Writing Center

- Revise hypothesis as necessary.

- Use information effectively for a specific purpose.

- Understand such issues as plagiarism, ownership of information (implications of copyright to some extent), and costs of information. Georgetown University Honor Council Copyright Basics (Purdue University) How to Recognize Plagiarism: Tutorials and Tests from Indiana University

- Cite properly and give credit for sources of ideas. MLA Bibliographic Form (7th edition, 2009) MLA Bibliographic Form (8th edition, 2016) Turabian Bibliographic Form: Footnote/Endnote Turabian Bibliographic Form: Parenthetical Reference Use a citation manager: Zotero or Refworks

Adapted from the Association of Colleges and Research Libraries "Objectives for Information Literacy Instruction" , which are more complete and include outcomes. See also the broader "Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 11 November 2022.

A dissertation proposal describes the research you want to do: what it’s about, how you’ll conduct it, and why it’s worthwhile. You will probably have to write a proposal before starting your dissertation as an undergraduate or postgraduate student.

A dissertation proposal should generally include:

- An introduction to your topic and aims

- A literature review of the current state of knowledge

- An outline of your proposed methodology

- A discussion of the possible implications of the research

- A bibliography of relevant sources

Dissertation proposals vary a lot in terms of length and structure, so make sure to follow any guidelines given to you by your institution, and check with your supervisor when you’re unsure.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Step 1: coming up with an idea, step 2: presenting your idea in the introduction, step 3: exploring related research in the literature review, step 4: describing your methodology, step 5: outlining the potential implications of your research, step 6: creating a reference list or bibliography.

Before writing your proposal, it’s important to come up with a strong idea for your dissertation.

Find an area of your field that interests you and do some preliminary reading in that area. What are the key concerns of other researchers? What do they suggest as areas for further research, and what strikes you personally as an interesting gap in the field?

Once you have an idea, consider how to narrow it down and the best way to frame it. Don’t be too ambitious or too vague – a dissertation topic needs to be specific enough to be feasible. Move from a broad field of interest to a specific niche:

- Russian literature 19th century Russian literature The novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky

- Social media Mental health effects of social media Influence of social media on young adults suffering from anxiety

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Like most academic texts, a dissertation proposal begins with an introduction . This is where you introduce the topic of your research, provide some background, and most importantly, present your aim , objectives and research question(s) .

Try to dive straight into your chosen topic: What’s at stake in your research? Why is it interesting? Don’t spend too long on generalisations or grand statements:

- Social media is the most important technological trend of the 21st century. It has changed the world and influences our lives every day.

- Psychologists generally agree that the ubiquity of social media in the lives of young adults today has a profound impact on their mental health. However, the exact nature of this impact needs further investigation.

Once your area of research is clear, you can present more background and context. What does the reader need to know to understand your proposed questions? What’s the current state of research on this topic, and what will your dissertation contribute to the field?

If you’re including a literature review, you don’t need to go into too much detail at this point, but give the reader a general sense of the debates that you’re intervening in.

This leads you into the most important part of the introduction: your aim, objectives and research question(s) . These should be clearly identifiable and stand out from the text – for example, you could present them using bullet points or bold font.

Make sure that your research questions are specific and workable – something you can reasonably answer within the scope of your dissertation. Avoid being too broad or having too many different questions. Remember that your goal in a dissertation proposal is to convince the reader that your research is valuable and feasible:

- Does social media harm mental health?

- What is the impact of daily social media use on 18– to 25–year–olds suffering from general anxiety disorder?

Now that your topic is clear, it’s time to explore existing research covering similar ideas. This is important because it shows you what is missing from other research in the field and ensures that you’re not asking a question someone else has already answered.

You’ve probably already done some preliminary reading, but now that your topic is more clearly defined, you need to thoroughly analyse and evaluate the most relevant sources in your literature review .

Here you should summarise the findings of other researchers and comment on gaps and problems in their studies. There may be a lot of research to cover, so make effective use of paraphrasing to write concisely:

- Smith and Prakash state that ‘our results indicate a 25% decrease in the incidence of mechanical failure after the new formula was applied’.

- Smith and Prakash’s formula reduced mechanical failures by 25%.

The point is to identify findings and theories that will influence your own research, but also to highlight gaps and limitations in previous research which your dissertation can address:

- Subsequent research has failed to replicate this result, however, suggesting a flaw in Smith and Prakash’s methods. It is likely that the failure resulted from…

Next, you’ll describe your proposed methodology : the specific things you hope to do, the structure of your research and the methods that you will use to gather and analyse data.

You should get quite specific in this section – you need to convince your supervisor that you’ve thought through your approach to the research and can realistically carry it out. This section will look quite different, and vary in length, depending on your field of study.

You may be engaged in more empirical research, focusing on data collection and discovering new information, or more theoretical research, attempting to develop a new conceptual model or add nuance to an existing one.

Dissertation research often involves both, but the content of your methodology section will vary according to how important each approach is to your dissertation.

Empirical research

Empirical research involves collecting new data and analysing it in order to answer your research questions. It can be quantitative (focused on numbers), qualitative (focused on words and meanings), or a combination of both.

With empirical research, it’s important to describe in detail how you plan to collect your data:

- Will you use surveys ? A lab experiment ? Interviews?

- What variables will you measure?

- How will you select a representative sample ?

- If other people will participate in your research, what measures will you take to ensure they are treated ethically?

- What tools (conceptual and physical) will you use, and why?

It’s appropriate to cite other research here. When you need to justify your choice of a particular research method or tool, for example, you can cite a text describing the advantages and appropriate usage of that method.

Don’t overdo this, though; you don’t need to reiterate the whole theoretical literature, just what’s relevant to the choices you have made.

Moreover, your research will necessarily involve analysing the data after you have collected it. Though you don’t know yet what the data will look like, it’s important to know what you’re looking for and indicate what methods (e.g. statistical tests , thematic analysis ) you will use.

Theoretical research

You can also do theoretical research that doesn’t involve original data collection. In this case, your methodology section will focus more on the theory you plan to work with in your dissertation: relevant conceptual models and the approach you intend to take.

For example, a literary analysis dissertation rarely involves collecting new data, but it’s still necessary to explain the theoretical approach that will be taken to the text(s) under discussion, as well as which parts of the text(s) you will focus on:

- This dissertation will utilise Foucault’s theory of panopticism to explore the theme of surveillance in Orwell’s 1984 and Kafka’s The Trial…

Here, you may refer to the same theorists you have already discussed in the literature review. In this case, the emphasis is placed on how you plan to use their contributions in your own research.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

You’ll usually conclude your dissertation proposal with a section discussing what you expect your research to achieve.

You obviously can’t be too sure: you don’t know yet what your results and conclusions will be. Instead, you should describe the projected implications and contribution to knowledge of your dissertation.

First, consider the potential implications of your research. Will you:

- Develop or test a theory?

- Provide new information to governments or businesses?

- Challenge a commonly held belief?

- Suggest an improvement to a specific process?

Describe the intended result of your research and the theoretical or practical impact it will have:

Finally, it’s sensible to conclude by briefly restating the contribution to knowledge you hope to make: the specific question(s) you hope to answer and the gap the answer(s) will fill in existing knowledge:

Like any academic text, it’s important that your dissertation proposal effectively references all the sources you have used. You need to include a properly formatted reference list or bibliography at the end of your proposal.

Different institutions recommend different styles of referencing – commonly used styles include Harvard , Vancouver , APA , or MHRA . If your department does not have specific requirements, choose a style and apply it consistently.

A reference list includes only the sources that you cited in your proposal. A bibliography is slightly different: it can include every source you consulted in preparing the proposal, even if you didn’t mention it in the text. In the case of a dissertation proposal, a bibliography may also list relevant sources that you haven’t yet read, but that you intend to use during the research itself.

Check with your supervisor what type of bibliography or reference list you should include.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 11). How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- What Is an Internship? Everything You Should Know

- How Long Should a Thesis Statement Be?

- How to Write a Character Analysis Essay

- Best Colours for Your PowerPoint Presentation: How to Choose

- How to Write a Nursing Essay

- Top 5 Essential Skills You Should Build As An International Student

- How Professional Editing Services Can Take Your Writing to the Next Level

- How to Write an Effective Essay Outline

- How to Write a Law Essay: A Comprehensive Guide with Examples

- What Are the Limitations of ChatGPT?

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

A complete guide to dissertation primary research

(Last updated: 7 May 2021)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

For many students, including those who are at postgraduate level or well-versed in the dissertation process, the prospect of primary research can be somewhat daunting.

But we are here to help quell those pesky nerves you may be feeling if you are faced with doing primary research for your dissertation.

Step 1: Decide on the type of data

Step 2: decide on primary research methodology.

Steps 3 – 8 if you have chosen a qualitative method

Steps 3 – 8 if you have chosen a quantitative method

Steps 3 – 8 if you have chosen a mixed method

Other steps you need to consider

The reasons that students can feel so wary of primary research can be many-fold. From a lack of knowledge of primary research methods, to a loathing for statistics, or an absence of the sufficient skills required… The apprehension that students can feel towards primary research for their dissertation is often comparable to the almost insurmountable levels of stress before exams.

And yet, there’s a significant difference between doing primary research and sitting exams. The former is far more engaging, rewarding, varied, and dare we say it, even fun. You’re in the driving seat and you get to ask the questions. What’s more, students carrying out primary research have an opportunity to make small contributions to their field, which can feel really satisfying – for many, it’s their first taste of being a researcher, rather than just a learner.

Now, if you’re reading this and scoffing at our steadfast enthusiasm for primary research, we’ll let you in on a little secret – doing research actually isn’t that difficult. It’s a case of learning to follow specific procedures and knowing when to make particular decisions.

Which is where this guide comes in; it offers step-by-step advice on these procedures and decisions, so you can use it to support you both before and during your dissertation research process.

As set out below, there are different primary research methodologies that you can choose from. The first two steps are the same for whatever method you choose; after that, the steps you take depend on the methodology you have chosen.

Primary data has been collected by the researcher himself or herself. When doing primary research for your undergraduate or graduate degrees, you will most commonly rely on this type of data. It is often said that primary data is “real time” data, meaning that it has been collected at the time of the research project. Here, the data collection is under the direct control of the researcher.

Secondary data has been collected by somebody else in the past and is usually accessible via past researchers, government sources, and various online and offline records. This type of data is referred to as “past data”, because it has been collected in the past. Using secondary data is relatively easy since you do not have to collect any data yourself. However, it is not always certain that secondary data would be 100% relevant for your project, since it was collected with a different research question in mind. Furthermore, there may be questions over the accuracy of secondary data.

Big data is the most complex type of data, which is why it is almost never used during undergraduate or graduate studies. Big data is characterised by three Vs: high volume of data, wide variety of the type of data, and high velocity with which the data is processed. Due to the complexity of big data, standard data processing procedures do not apply and you would need intense training to learn how to process it.

Qualitative research is exploratory in nature. This means that qualitative research is often conducted when there are no quantitative investigations on the topic, and you are seeking to explore the topic for the first time. This exploration is achieved by considering the perspectives of specific individuals. You are concerned with particular meanings that reflect a dynamic (rather than fixed) reality. By observing or interviewing people, you can come to an understanding of their own perception of reality.

Quantitative research is confirmatory in nature. Thus, the main goal is to confirm or disconfirm hypotheses by relying on statistical analyses. In quantitative research, you will be concerned with numerical data that reflects a fixed and measurable (rather than dynamic) reality. Using large samples and testing your participants through reliable tools, you are seeking to generalise your findings to the broader population.

Mixed research combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The goal is to gain a more thorough understanding of a topic than would be possible by relying on a single methodological approach. Usually, a mixed method involves doing qualitative research first, which is then supplemented by quantitative research.

Thus, first you explore a phenomenon through a low-scale study that focuses on the meanings of particular individuals, and then you seek to form a hypothesis and test it with a larger sample. You can rely on other mixed methodologies as well, which will be described later.

What to do if you have chosen a qualitative method

Step 3: be aware of strengths and limitations.

Still, there are many things that you cannot achieve with qualitative research. Since you are investigating a select group of people, you cannot generalise your findings to the broader population. With qualitative methodology, it is also harder to establish the quality of research. Here, the quality depends on your own skills and your ability to avoid bias while interpreting findings. Finally, qualitative research involves interpreting multiple perspectives, which makes it harder to reach a consensus and establish a “bottom line” of your results and conclusions.

Step 4: Select a specific qualitative method

An observation, as its name implies, involves observing a group of individuals within their own setting. As a researcher, your role is to immerse yourself in this setting and observe the behaviour of interest. You may either become involved with your participants, therefore taking a participating role, or you can act as a bystander and observer. You will need to complete an observation checklist, which you will have made in advance, on which you will note how your participants behaved.

Interviews are the most common qualitative method. In interviews, your role is to rely on predetermined questions that explore participants’ understanding, opinions, attitudes, feelings, and the like. Depending on your research topic, you may also deviate from your question structure to explore whatever appears relevant in the present moment. The main aim is always to understand participants’ own subjective perspectives.

Focus groups are like interviews, except that they are conducted with more than one person. Participants in a focus group are several individuals usually from different demographic backgrounds. Your role is to engage them in an open discussion and to explore their understanding of a topic.

In both interviews and focus groups, you should record your sessions and transcribe them afterwards.

Step 5: Select participants

To establish who these individuals (or organisation) will be, you must consult your research question. You also need to decide on the number of participants, which is generally low in qualitative research, and to decide whether participants should be from similar or different backgrounds. Ask yourself: What needs to connect them and what needs to differentiate them?

Selecting your participants involves deciding how you will recruit them. An observation study, usually has a predetermined context in which your participants operate, and this makes recruitment straightforward since you know where your participants are. A case study does not necessitate recruitment, since your subject of investigation is a predefined person or organisation.

However, interviews and focus groups need a more elaborate approach to recruitment as your participants need to represent a certain target group. A common recruitment method here is the snowball technique, where your existing participants themselves recruit more participants. Otherwise, you need to identify what connects your participants and try to recruit them at a location where they all operate.

Also remember that your participants always need to sign an informed consent, therefore agreeing to take part in the research (see Step 9 below for more information about informed consent and research ethics).

Step 6: Select measures

Observation studies usually involve a checklist on which you note your observations. Focus groups, interviews, and most case studies use structured or semi-structured interviews. Structured interviews rely on a predetermined set of questions, whereas semi-structured interviews combine predetermined questions with an opportunity to explore the responses further.

In most circumstances, you will want to use semi-structured interviews because they enable you to elicit more detailed responses.

When using observations, you will need to craft your observation checklist; when using interviews, you will need to craft your interview questions. Observation checklists are easy to create, since they involve your predetermined focuses of observation. These may include participants’ names (or numbers if they are to remain anonymous), their demographic characteristics, and whatever it is that you are observing.

When crafting interview questions, you will need to consult your research question, and sometimes also the relevant literature. For instance, if your interviews focus on the motivations for playing computer games, you can craft general questions that relate to your research question – such as, “what motivates you to play computer games the most?”.

However, by searching the relevant literature, you may discover that some people play games because they feel competent, and then decide to ask your subjects, “does playing games satisfy your need for competence?”

Step 7: Select analyses

With qualitative research, your data analysis relies on coding and finding themes in your data.

The process of coding should be straightforward. You simply need to read through your observation checklist or interview transcripts and underline each interesting observation or answer.

Finding themes in your data involves grouping the coded observations/answers into patterns. This is a simple process of grouping codes, which may require some time, but is usually interesting work. There are different procedures to choose from while coding and finding themes in your data. These include thematic analysis, interpretative phenomenological analysis, constant comparative analysis, narrative analysis, and discourse analysis. Let’s define each of these.

Thematic analysis is the most commonly used procedure. The goal is to code data, search for themes among the codes, review themes, and name themes. Interpretative phenomenological analysis is done in the same way as a thematic analysis, but with a special focus on understanding how a given person, in a given context, makes sense of a phenomenon.

In constant comparative analysis, one piece of data (one theme, one statement) is compared to all others to detect similarities or differences; this comparison aims at understanding the relations between the data. Narrative analysis also extracts themes, but it focuses on the way that participants represent their experiences linguistically.

Finally, discourse analysis also focuses on language, but the goal is to understand how language relates to the influences that shape people’s thoughts and behaviours.

Step 8: Understand procedure

During observations and interviews, you are collecting your data. As noted previously, you always need to record your interviews and transcribe them afterwards. Observation checklists merely need to be completed during observations.

Once your data has been collected, you can then analyse your results, after which you should be ready to write your final report.

What to do if you have chosen a quantitative method

Quantitative research also enables you to test hypotheses and to determine causality. Determining causality is possible because a quantitative method allows you to control for extraneous variables (confounders) that may affect the relationship between certain variables. Finally, by using standardised procedures, your quantitative study can be replicated in the future, either by you or by other researchers.

At the same time, however, quantitative research also has certain limitations. For instance, this type of research is not as effective at understanding in-depth perceptions of people, simply because it seeks to average their responses and get a “bottom line” of their answers.

In addition, quantitative research often uses self-report measures and there can never be certainty that participants were honest. Sometimes, quantitative research does not include enough contextual information for the interpretation of results. Finally, a failure to correctly select your participants, measures and analyses might lower the generalisability and accuracy of your findings.

Step 4: Select a specific quantitative method

Let’s look at each of these separately.

Descriptive research is used when you want to describe characteristics of a population or a phenomenon. For instance, if you want to describe how many college students use drugs and which drugs are most commonly used, then you can use descriptive research.

You are not seeking to establish the relationship between different variables, but merely to describe the phenomenon in question. Thus, descriptive research is never used to establish causation.

Correlational research is used when you are investigating a relationship between two or more variables. The concept of independent and dependent variables is important for correlational research.

An independent variable is one that you control to test the effects on the dependent variable. For example, if you want to see how intelligence affects people’s critical thinking, intelligence is your independent variable and critical thinking is your dependent variable.

In scientific jargon, correlation tests whether an independent variable relates to the levels of the dependent variable(s). Note that correlation never establishes causation – it merely tests a relationship between variables.

You can also control for the effect of a third variable, which is called a covariate or a confounder. For instance, you may want to see if intelligence relates to critical thinking after controlling for people’s abstract reasoning.

The reason why you might want to control for this variable is that abstract reasoning is related to both intelligence and critical thinking. Thus, you are trying to specify a more direct relationship between intelligence and critical thinking by removing the variable that “meddles in between”.

Experiments aim to establish causation. This is what differentiates them from descriptive and correlational research. To establish causation, experiments manipulate the independent variable.

Or, to put this another way, experiments have two or more conditions of the independent variable and they test their effect on the dependent variable. Here’s an example: You want to test if a new supplement (independent variable) increases people’s concentration (dependent variable). You need a reference point – something to compare this effect to. Thus, you compare the effect of a supplement to a placebo, by giving some of your participants a sugary pill.

Now your independent variable is the type of treatment, with two conditions – supplement and placebo. By comparing the concentration levels (dependent variable) between participants who received the supplement versus placebo (independent variable), you can determine if the supplement caused increased concentration.

Experiments can have two types of designs: between-subjects and within-subjects. The above example illustrated a between-subjects design because concentration levels were compared between participants who got a supplement and those who got a placebo.

But you can also do a within-subjects comparison. For example, you may want to see if taking a supplement before or after a meal impacts concentration levels differently. Here, your independent variable is the time the supplement is taken (with two conditions: before and after the meal). You then ask the same group of participants to take on Day 1 the supplement before the meal and on Day 2 after the meal.

Since both conditions apply to all your participants, you are making a within-subjects comparison. Regardless of the type of design you are using, when assigning participants to a condition, you need to ensure that you do so randomly.

A quasi-experiment is not a true experiment. It differs from a true experiment because it lacks random assignment to different conditions. You would use a quasi-experiment when your participants are grouped into different conditions according to a predetermined characteristic.

For instance, you may want to see if children are less likely than adolescents to cheat on a test. Here, you are categorising your participants according to their age and thus you cannot use random assignment. Because of this, it is often said that quasi-experiments cannot properly establish causation.

Nonetheless, they are a useful tool for looking at differences between predetermined groups of participants.

A very good practice is to rely on a G-Power analysis to calculate how large your sample size should be in order to increase the accuracy of your findings. G-Power analysis, for which you can download a program online, is based on a consideration of previous studies’ effect sizes, significance levels, and power.

Thus, you will need to find a study that investigated a similar effect, dig up its reported effect size, significance level and power, and enter these parameters in a G-Power analysis. There are many guides online on how to do this.

When selecting participants for your quantitative research, you also need to ensure that they are representative of the target population. You can do this by specifying your inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For instance, if your target population consists of young women who have given birth and who have depression, then you will include only women who have given birth, who are younger than 35, and who have depression. Consequently, you will exclude women who do not fulfil these criteria.

Remember that here, just as in qualitative research, you need informed consent from your participants, therefore ensuring that they have agreed to take part in the research.

A questionnaire is reliable when it has led to consistent results across studies, and it is valid when it measures what it is supposed to measure. You can claim that a questionnaire is valid and reliable when previous studies have established its validity and reliability (you must cite these studies, of course).

Moreover, you can test the reliability of a questionnaire yourself, by calculating its Cronbach’s Alpha value in a statistics programme, such as SPSS. Values higher than 0.7 indicate acceptable reliability, values higher than 0.8 indicate good reliability, and values higher than 0.9 indicate excellent reliability. Anything below 0.7 indicates unreliability.

You can always consult your supervisor about which questionnaires to use in your study. Alternatively, you can search for questionnaires yourself by looking at previous studies and the kind of measures they employed.

Each questionnaire that you decide to use will require you to calculate final scores. You can obtain the guidelines for calculating final scores in previous studies that used a given questionnaire. You will complete this calculation by relying on a statistical program.

Very often, this calculation will involve reverse-scoring some items. For instance, a questionnaire may ask “are you feeling good today?”, where a response number of 5 means “completely agree”. Then you can have another question that asks “are you feeling bad today?”, where a response number of 5 again means “completely agree”. If your questionnaire measures whether a person feels good, then you will have to reverse-score the second of these questions so that higher responses indicate feeling more (rather than less) good. This can also be done using a statistics program.

However, there is no reason why they should, since the whole procedure of doing statistical analyses is not that difficult – you just need to know which analysis to use for which purpose and to read guidelines on how to do particular analyses (online and in books). Let’s provide specific examples.

If you are doing descriptive research, your analyses will rely on descriptive and/or frequencies statistics.

Descriptive statistics include calculating means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies statistics include calculating the number and percentage of the frequencies of answers on categorical variables.

Continuous variables are those where final scores have a wide range. For instance, participants’ age is a continuous variable, because the final scores can range from 1 year to 100 years. Here, you calculate a mean and say that your participants were, on average, 37.7 years old (for example).

Another example of a continuous variable are responses from a questionnaire where you need to calculate a final score. For example, if your questionnaire assessed the degree of satisfaction with medical services, on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely), and there are ten questions on the questionnaire, you will have a final score for each participant that ranges from 10 to 50. This is a continuous variable and you can calculate the final mean score (and standard deviation) for your whole sample.

Categorical variables are those that do not result in final scores, but result in categorising participants in specific categories. An example of a categorical variable is gender, because your participants are categorised as either male or female. Here, your final report will say something like “50 (50%) participants were male and 50 (50%) were female”.

Please note that you will have to do descriptive and frequencies statistics in all types of quantitative research, even if your research is not descriptive research per se. They are needed when you describe the demographic characteristics of your sample (participants’ age, gender, education level, and the like).

When doing correlational research, you will perform a correlation or a regression analysis. Correlation analysis is done when you want to see if levels of an independent variable relate to the levels of a dependent variable (for example, “is intelligence related to critical thinking?”).

You will need to check if your data is normally distributed – that is, if the histogram that summarises the data has a bell-shaped curve. This can be done by creating a histogram in a statistics program, the guidelines for which you can find online. If you conclude that your data is normally distributed, you will rely on a Pearson correlation analysis; if your data is not normally distributed, you will use a Spearman correlation analysis. You can also include a covariate (such as people’s abstract reasoning) and see if a correlation exists between two variables after controlling for a covariate.

Regression analysis is done when you want to see if levels of an independent variable(s) predict levels of a dependent variable (for example, “does intelligence predict critical thinking?”). Regression is useful because it allows you to control for various confounders simultaneously. Thus, you can investigate if intelligence predicts critical thinking after controlling for participants’ abstract reasoning, age, gender, educational level, and the like. You can find online resources on how to interpret a regression analysis.

When you are conducting experiments and quasi-experiments, you are using t-tests, ANOVA (analysis of variance), or MANCOVA (multivariate analysis of variance).

Independent samples t-tests are used when you have one independent variable with two conditions (such as giving participants a supplement versus a placebo) and one dependent variable (such as concentration levels). This test is called “independent samples” because you have different participants in your two conditions.

As noted above, this is a between-subjects design. Thus, with an independent samples t-test you are seeking to establish if participants who were given a supplement, versus those who were given a placebo, show different concentration levels. If you have a within-subjects design, you will use a paired samples t-test. This test is called “paired” because you compare the same group of participants on two paired conditions (such as taking a supplement before versus after a meal).

Thus, with a paired samples t-test, you are establishing whether concentration levels (dependent variable) at Time 1 (taking a supplement before the meal) are different than at Time 2 (taking a supplement after the meal).

There are two main types of ANOVA analysis. One-way ANOVA is used when you have more than two conditions of an independent variable.

For instance, you would use a one-way ANOVA in a between-subjects design, where you are testing the effects of the type of treatment (independent variable) on concentration levels (dependent variable), while having three conditions of the independent variable, such as supplement (condition 1), placebo (condition 2), and concentration training (condition 3).

Two-way ANOVA, on the other hand, is used when you have more than one independent variable.

For instance, you may want to see if there is an interaction between the type of treatment (independent variable with three conditions: supplement, placebo, and concentration training) and gender (independent variable with two conditions: male and female) on participants’ concentration (dependent variable).

Finally, MANCOVA is used when you have one or more independent variables, but you also have more than one dependent variable.

For example, you would use MANCOVA if you are testing the effect of the type of treatment (independent variable with three conditions: supplement, placebo, and concentration training) on two dependent variables (such as concentration and an ability to remember information correctly).

If you are doing an experiment, once you have recruited your participants, you need to randomly assign them to conditions. If you are doing quasi-experimental research, you will have a specific procedure for predetermining which participant goes to which condition. For instance, if you are comparing children versus adolescents, you will categorise them according to their age. In the case of descriptive and correlational research, you don’t need to categorise your participants.

Furthermore, with all procedures you need to introduce your participants to the research and give them an informed consent. Then you will provide them with the specific measures you are using.

Sometimes, it is good practice to counterbalance the order of questionnaires. This means that some participants will get Questionnaire 1 first, and others will be given Questionnaire 2 first.

Counterbalancing is important to remove the possibility of the “order effects”, whereby the order of the presentation of questionnaires influences results.

At the end of your study, you will “debrief” your participants, meaning that you will explain to them the actual purpose of the research. After doing statistical analysis, you will need to write a final report.

What to do if you have chosen a mixed method

Quantitative research, on the other hand, is limited because it does not lead to an in-depth understanding of particular meanings and contexts – something that qualitative research makes up for. Thus, by using the mixed method, the strengths of each approach are making up for their respective weaknesses. You can, therefore, obtain more information about your research question than if you relied on a single methodology.

Mixed research has, however, some limitations. One of its main limitations is that research design can be quite complex. It can also take much more time to plan mixed research than to plan qualitative or quantitative research.

Sometimes, you may experience difficulties in bridging your results because you need to combine the results of qualitative and quantitative research. Finally, you may find it difficult to resolve discrepancies that occur when you interpret your results.

For these reasons, mixed research needs to be done and interpreted with care.

Step 4: Select a specific mixed method

Let’s address each of these separately.

Sequential exploratory design is a method whereby qualitative research is done first and quantitative research is done second. By following this order, you can investigate a topic in-depth first, and then supplement it with numerical data. This method is useful if you want to test the elements of a theory that stems from qualitative research and if you want to generalise qualitative findings to different population samples.

Sequential explanatory design is when quantitative research is done first and qualitative research is done second. Here, priority is given to quantitative data. The goal of subsequent collection of qualitative data is to help you interpret the quantitative data. This design is used when you want to engage in an in-depth explanation, interpretation, and contextualisation of quantitative findings. Alternatively, you can use it when you obtain unexpected results from quantitative research, which you then want to clarify through qualitative data.

Concurrent triangulation design involves the simultaneous use of qualitative and quantitative data collection. Here, equal weighting is given to both methods and the analysis of both types of data is done both separately and simultaneously.

This design is used when you want to obtain detailed information about a topic and when you want to cross-validate your findings. Cross-validation is a statistical procedure for estimating the performance of a theoretical model that predicts something. Although you may decide to use concurrent triangulation during your research, you will probably not be asked to cross-validate the findings, since this is a complex procedure.

Concurrent nested design is when you collect qualitative and quantitative data at the same time, but you employ a dominant method (qualitative or quantitative) that nests or embeds the less dominant method (for example, if the dominant method is quantitative, the less dominant would be qualitative).

What this nesting means is that your less dominant method addresses a different research question than that addressed by your dominant method. The results of the two types of methods are then combined in the final work output. Concurrent nested design is the most complex form of mixed designs, which is why you are not expected to use it during your undergraduate or graduate studies, unless you have been specifically asked.

In summary, participants in the qualitative part of the investigation will be several individuals who are relevant for your research project. Conversely, your sample size for the quantitative part of the investigation will be higher, including many participants chosen as representative of your target population.

You will also need to rely on different recruitment strategies when selecting participants for qualitative versus quantitative research.

An in-depth explanation of these measures has been provided in the sections above dealing with qualitative and quantitative research respectively.

In summary, qualitative research relies on the use of observations or interviews, which you usually need to craft yourself. Quantitative research relies on the use of reliable and valid questionnaires, which you can take from past research.

Sometimes, within the mixed method, you will be required to craft a questionnaire on the basis of the results of your qualitative research. This is especially likely if you are using the sequential exploratory design, where you seek to validate the results of your qualitative research through subsequent quantitative data.

In any case, a mixed method requires a special emphasis on aligning your qualitative and quantitative measures, so that they address the same topic. You can always consult your supervisor on how to do this.

In general, qualitative investigations require you to thematically analyse your data, which is done through coding participants’ answers or your observations and finding themes among the codes. You can rely on a thematic analysis, interpretative phenomenological analysis, constant comparative analysis, narrative analysis, and discourse analysis.

Quantitative investigations require you to do statistical analyses, the choice of which depends on the type of quantitative design you are using. Thus, you will use descriptive statistics if you do descriptive research, correlation or regression if you are doing correlational research, and a t-test, ANOVA, or MANCOVA if you are doing an experiment or a quasi-experiment.

The reverse is true if you are using the sequential explanatory design. Concurrent triangulation and concurrent nested designs require you to perform the qualitative and quantitative parts of the investigation simultaneously; what differentiates them is whether you are (or are not) prioritising one (either qualitative or quantitative) as a predominant method.

Regardless of your mixed design, you will need to follow specific procedures for qualitative and quantitative research, all of which have been described above.

Step 9: Think about ethics

Some studies deal with especially vulnerable groups of people or with sensitive topics. It is extremely important, therefore, that no harm is done to your participants.

Before beginning your primary research, you will submit your research proposal to an ethics committee. Here, you will specify how you will deal with all possible ethical issues that may arise during your study. Even if your primary research is deemed as ethical, you will need to comply with certain rules and conduct to satisfy the ethical requirements. These consist of providing informed consent, ensuring confidentiality and the protection of participants, allowing a possibility to withdraw from the study, and providing debriefing.