Explainer: Causes and consequences of Amazon fires and deforestation

- Medium Text

WHAT CAUSES THE FIRES?

Why are brazil's fires so bad at this time of year, is climate change affecting amazon forest fires, have brazil's fires been worse than usual in recent years, how much worse is forest loss since 2019.

WILL THIS YEAR'S FIRE SEASON BE DIFFERENT?

Are the amazon fires contributing to climate change.

Sign up here.

Reporting by Jake Spring in Sao Paulo and Gloria Dickie in London; Editing by Katy Daigle

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Jake Spring reports primarily on forests, climate diplomacy, carbon markets and climate science. Based in Brazil, his investigative reporting on destruction of the Amazon rainforest under ex-President Jair Bolsonaro won 2021 Best Reporting in Latin America from the Overseas Press Club of America (https://opcofamerica.org/Awardarchive/the-robert-spiers-benjamin-award-2021/). His beat reporting on Brazil’s environmental destruction won a Covering Climate Now award and was honored by the Society of Environmental Journalists. He joined Reuters in 2014 in China, where he previously worked as editor-in-chief of China Economic Review. He is fluent in Mandarin Chinese and Brazilian Portuguese.

Gloria Dickie reports on climate and environmental issues for Reuters. She is based in London. Her interests include biodiversity loss, Arctic science, the cryosphere, international climate diplomacy, climate change and public health, and human-wildlife conflict. She previously worked as a freelance environmental journalist for 7 years, writing for publications such as the New York Times, the Guardian, Scientific American, and Wired magazine. Dickie was a 2022 finalist for the Livingston Awards for Young Journalists in the international reporting category for her climate reporting from Svalbard. She is also an author at W.W. Norton.

Mexico's Sheinbaum: judicial reform won't violate commitments with USMCA trade pact

A judicial reform planned by Mexico's government will not violate the country's commitments with the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum said on Wednesday.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

UConn Today

September 7, 2021 | Combined Reports - UConn Communications

Study Shows the Impacts of Deforestation and Forest Burning on Biodiversity in the Amazon

Since 2001, between 40,000 and 73,400 square miles of Amazon rainforest have been impacted by fires

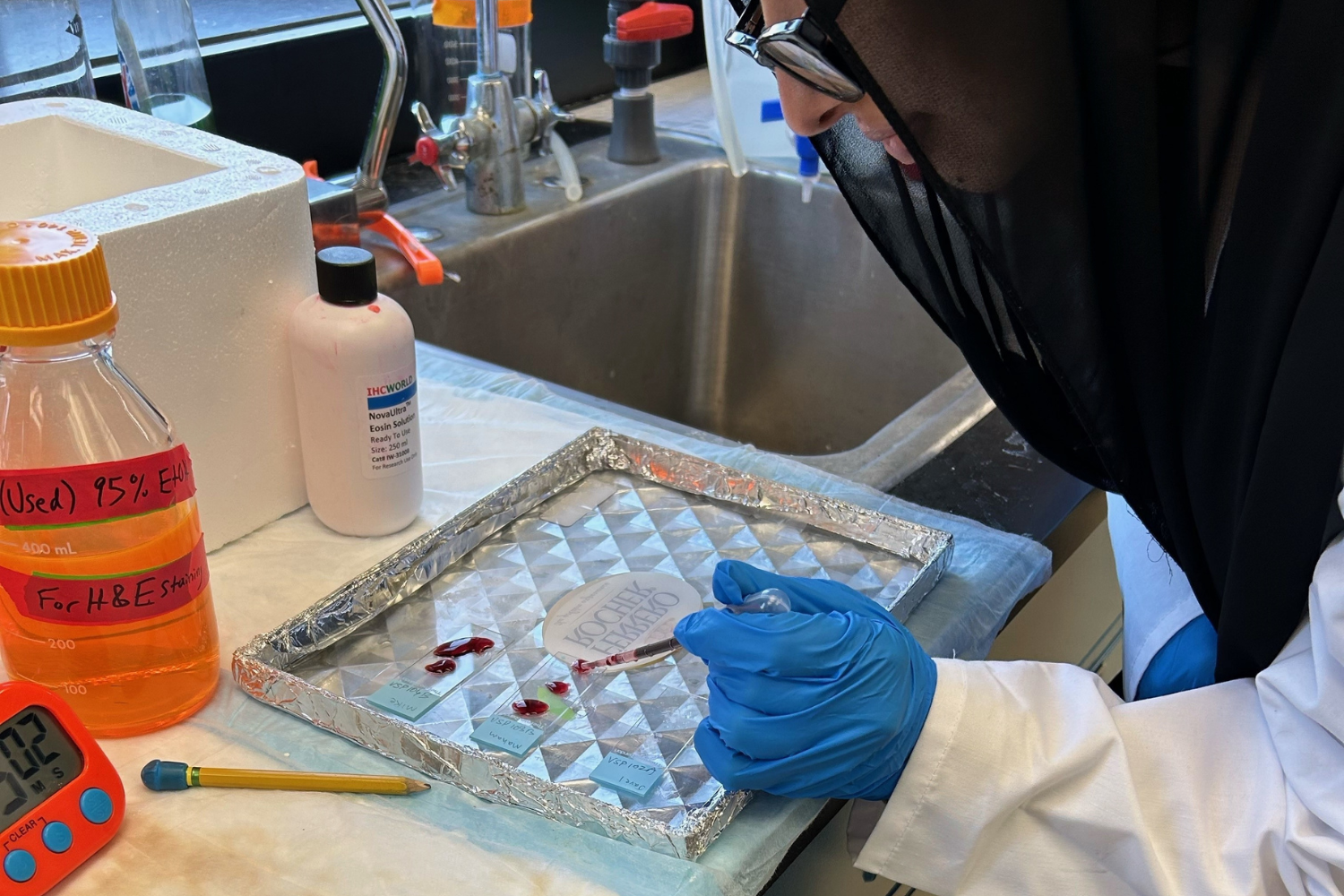

Ring of fire: Smoke rises through the understory of a forest in the Amazon region. Plants and animals in the Amazonian rainforest evolved largely without fire, so they lack the adaptations necessary to cope with it. (Credit: Paulo Brando)

A new study, co-authored by a team of researchers including UConn Ecology and Evolutionary Biology researcher Cory Merow provides the first quantitative assessment of how environmental policies on deforestation, along with forest fires and drought, have impacted the diversity of plants and animals in the Amazon. The findings were published in the Sept. 1 issue of Nature .

Researchers used records of more than 14,500 plant and vertebrate species to create biodiversity maps of the Amazon region. Overlaying the maps with historical and current observations of forest fires and deforestation over the last two decades allowed the team to quantify the cumulative impacts on the region’s species.

They found that since 2001, between 40,000 and 73,400 square miles of Amazon rainforest have been impacted by fires, affecting 95% of all Amazonian species and as many as 85% of species that are listed as threatened in this region. While forest management policies enacted in Brazil during the mid-2000s slowed the rate of habitat destruction, relaxed enforcement of these policies coinciding with a change in government in 2019 has seemingly begun to reverse this trend, the authors write. With fires impacting 1,640 to 4,000 square miles of forest, 2019 stands out as one of the most extreme years for biodiversity impacts since 2009, when regulations limiting deforestation were enforced.

“Perhaps most compelling is the role that public pressure played in curbing forest loss in 2019,” Merow says. “When the Brazilian government stopped enforced forest regulations in 2019, each month between January and August 2019 was the worse month on record (e.g. comparing January 2019 to previous January’s) for forest loss in the 20-year history of available data. However, based on international pressure, forest regulation resumed in September 2019, and forest loss declined significantly for the rest of the year, resulting in 2019 looking like an average year compared to the 20-year history. This was big: active media coverage and public support for policy changes were effective at curbing biodiversity loss on a very rapid time scale.”

The findings are especially critical in light of the fact that at no point in time did the Amazon get a break from those increasing impacts, which would have allowed for some recovery, says senior study author Brian Enquist, a professor in UArizona’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology .

“Even with policies in place, which you can think of as a brake slowing the rate of deforestation, it’s like a car that keeps moving forward, just at a slower speed,” Enquist says. “But in 2019, it’s like the foot was let off the brake, causing it to accelerate again.”

Known mostly for its dense rainforests, the Amazon basin supports around 40% of the world’s remaining tropical forests. It is of global importance as a provider of ecosystem services such as scrubbing and storing carbon from the atmosphere, and it plays a vital role in regulating Earth’s climate. The area also is an enormous reservoir of the planet’s biodiversity, providing habitats for one out of every 10 of the planet’s known species. It has been estimated that in the Amazon, 1,000 tree species can populate an area smaller than a half square mile.

“Fire is not a part of the natural cycle in the rainforest,” says study co-author Crystal N. H. McMichael at the University of Amsterdam. “Native species lack the adaptations that would allow them to cope with it, unlike the forest communities in temperate areas. Repeated burning can cause massive changes in species composition and likely devastating consequences for the entire ecosystem.”

Since the 1960s, the Amazon has lost about 20% of its forest cover to deforestation and fires. While fires and deforestation often go hand in hand, that has not always been the case, Enquist says. As climate change brings more frequent and more severe drought conditions to the region, and fire is often used to clear large areas of rainforest for the agricultural industry, deforestation has spillover effects by increasing the chances of wildfires. Forest loss is predicted reach 21 to 40% by 2050, and such habitat loss will have large impacts on the region’s biodiversity, according to the authors.

“Since the majority of fires in the Amazon are intentionally set by people, preventing them is largely within our control,” says study co-author Patrick Roehrdanz, senior manager of climate change and biodiversity at Conservation International. “One way is to recommit to strong antideforestation policies in Brazil, combined with incentives for a forest economy, and replicate them in other Amazonian countries.”

Policies to protect Amazonian biodiversity should include the formal recognition of Indigenous lands, which encompass more than one-third of the Amazon region, the authors write, pointing to previous research showing that lands owned, used or occupied by Indigenous peoples have less species decline, less pollution and better-managed natural resources.

The authors say their study underscores the dangers of continuing lax policy enforcement. As fires encroach on the heart of the Amazon basin, where biodiversity is greatest, their impacts will have more dire effects, even if the rate of forest burning remains unchanged.

The research was made possible by strategic investment funds allocated by the Arizona Institutes for Resilience at UArizona and the university’s Bridging Biodiversity and Conservation Science group. Additional support came from the National Science Foundation’s Harnessing the Data Revolution program . Data and computation were provided through the Botanical Information and Ecology Network , which is supported by CyVerse , the NSF’s data management platform led by UArizona.

Recent Articles

August 21, 2024

Summer Scientific Research by Connecticut Youth at UConn Health

Read the article

Cheese Champions: UConn Cheeses Win Awards in National, Regional Competitions

August 20, 2024

Finding Healing: UConn Leads National Study Effort for Survivors of State-Sponsored Torture

| GEOG 30N Environment and Society in a Changing World |

- ASSIGNMENTS

- Program Home Page

- LIBRARY RESOURCES

Case Study: The Amazon Rainforest

The Amazon in context

Tropical rainforests are often considered to be the “cradles of biodiversity.” Though they cover only about 6% of the Earth’s land surface, they are home to over 50% of global biodiversity. Rainforests also take in massive amounts of carbon dioxide and release oxygen through photosynthesis, which has also given them the nickname “lungs of the planet.” They also store very large amounts of carbon, and so cutting and burning their biomass contributes to global climate change. Many modern medicines are derived from rainforest plants, and several very important food crops originated in the rainforest, including bananas, mangos, chocolate, coffee, and sugar cane.

In order to qualify as a tropical rainforest, an area must receive over 250 centimeters of rainfall each year and have an average temperature above 24 degrees centigrade, as well as never experience frosts. The Amazon rainforest in South America is the largest in the world. The second largest is the Congo in central Africa, and other important rainforests can be found in Central America, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia. Brazil contains about 40% of the world’s remaining tropical rainforest. Its rainforest covers an area of land about 2/3 the size of the continental United States.

There are countless reasons, both anthropocentric and ecocentric, to value rainforests. But they are one of the most threatened types of ecosystems in the world today. It’s somewhat difficult to estimate how quickly rainforests are being cut down, but estimates range from between 50,000 and 170,000 square kilometers per year. Even the most conservative estimates project that if we keep cutting down rainforests as we are today, within about 100 years there will be none left.

How does a rainforest work?

Rainforests are incredibly complex ecosystems, but understanding a few basics about their ecology will help us understand why clear-cutting and fragmentation are such destructive activities for rainforest biodiversity.

High biodiversity in tropical rainforests means that the interrelationships between organisms are very complex. A single tree may house more than 40 different ant species, each of which has a different ecological function and may alter the habitat in distinct and important ways. Ecologists debate about whether systems that have high biodiversity are stable and resilient, like a spider web composed of many strong individual strands, or fragile, like a house of cards. Both metaphors are likely appropriate in some cases. One thing we can be certain of is that it is very difficult in a rainforest system, as in most other ecosystems, to affect just one type of organism. Also, clear cutting one small area may damage hundreds or thousands of established species interactions that reach beyond the cleared area.

Pollination is a challenge for rainforest trees because there are so many different species, unlike forests in the temperate regions that are often dominated by less than a dozen tree species. One solution is for individual trees to grow close together, making pollination simpler, but this can make that species vulnerable to extinction if the one area where it lives is clear cut. Another strategy is to develop a mutualistic relationship with a long-distance pollinator, like a specific bee or hummingbird species. These pollinators develop mental maps of where each tree of a particular species is located and then travel between them on a sort of “trap-line” that allows trees to pollinate each other. One problem is that if a forest is fragmented then these trap-line connections can be disrupted, and so trees can fail to be pollinated and reproduce even if they haven’t been cut.

The quality of rainforest soils is perhaps the most surprising aspect of their ecology. We might expect a lush rainforest to grow from incredibly rich, fertile soils, but actually, the opposite is true. While some rainforest soils that are derived from volcanic ash or from river deposits can be quite fertile, generally rainforest soils are very poor in nutrients and organic matter. Rainforests hold most of their nutrients in their live vegetation, not in the soil. Their soils do not maintain nutrients very well either, which means that existing nutrients quickly “leech” out, being carried away by water as it percolates through the soil. Also, soils in rainforests tend to be acidic, which means that it’s difficult for plants to access even the few existing nutrients. The section on slash and burn agriculture in the previous module describes some of the challenges that farmers face when they attempt to grow crops on tropical rainforest soils, but perhaps the most important lesson is that once a rainforest is cut down and cleared away, very little fertility is left to help a forest regrow.

What is driving deforestation in the Amazon?

Many factors contribute to tropical deforestation, but consider this typical set of circumstances and processes that result in rapid and unsustainable rates of deforestation. This story fits well with the historical experience of Brazil and other countries with territory in the Amazon Basin.

Population growth and poverty encourage poor farmers to clear new areas of rainforest, and their efforts are further exacerbated by government policies that permit landless peasants to establish legal title to land that they have cleared.

At the same time, international lending institutions like the World Bank provide money to the national government for large-scale projects like mining, construction of dams, new roads, and other infrastructure that directly reduces the forest or makes it easier for farmers to access new areas to clear.

The activities most often encouraging new road development are timber harvesting and mining. Loggers cut out the best timber for domestic use or export, and in the process knock over many other less valuable trees. Those trees are eventually cleared and used for wood pulp, or burned, and the area is converted into cattle pastures. After a few years, the vegetation is sufficiently degraded to make it not profitable to raise cattle, and the land is sold to poor farmers seeking out a subsistence living.

Regardless of how poor farmers get their land, they often are only able to gain a few years of decent crop yields before the poor quality of the soil overwhelms their efforts, and then they are forced to move on to another plot of land. Small-scale farmers also hunt for meat in the remaining fragmented forest areas, which reduces the biodiversity in those areas as well.

Another important factor not mentioned in the scenario above is the clearing of rainforest for industrial agriculture plantations of bananas, pineapples, and sugar cane. These crops are primarily grown for export, and so an additional driver to consider is consumer demand for these crops in countries like the United States.

These cycles of land use, which are driven by poverty and population growth as well as government policies, have led to the rapid loss of tropical rainforests. What is lost in many cases is not simply biodiversity, but also valuable renewable resources that could sustain many generations of humans to come. Efforts to protect rainforests and other areas of high biodiversity is the topic of the next section.

Amazon Rainforest Fires

The first seven months of 2024 saw the highest number of fires in 20 years, a staggering 7.4 million acres of brazil’s amazon burned in the first half of 2024, a 122% increase from the previous year, expanding and securing land rights of indigenous peoples is one of the best ways to protect the amazon, 2024 marks the worst year for amazon fires in two decades.

In a troubling trend, the Brazilian Amazon registered a 76% increase in fire hotspots from 2023 during the same seven month period (January – July). According to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), there were nearly 25,000 fire hotspots through July 2024, the highest number for this period since 2005. Of these hotspots, 11,434 were recorded in July alone, an increase of 98% compared to the same month last year, which recorded 5,772 fire hotspots. The highest number of fires in the month was recorded on July 30, with 1,348 records in a single day.

Other areas of the Amazon also experienced a record number of fires in the first seven months of the year, including Bolivia. According to data from INPE, the country registered roughly 17,700 fire points from January through July, the most ever seen in that period. Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname also saw a huge surge in fires in the first seven months of the year.

The Brazilian Amazon already experienced a significant increase in fires in 2023 , with at least 26.4 million acres burned, representing a 35.4% increase from 2022. The majority of this destruction occurred in the final months of the year. The current data indicates a critical and escalating situation for Amazon fires in 2024, underscoring the urgent need for immediate and effective action to mitigate further damage.

The Impact of Climate Change and Rising Temperatures

Several factors have contributed to the massive increase in fires in the Amazon. The region is experiencing drier conditions, a phenomenon closely linked to climate change and intensified by El Niño. In fact, 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded for our planet, and June 2024 marked 13 consecutive months of global record temperatures, increasing the forest’s vulnerability to fires. The region also experienced a historic drought in 2023 , which caused flames to spread through native vegetation. Low water levels in the region’s rivers made it difficult to combat the fires, leaving Indigenous and riverside villages inaccessible.

Area Burned in Brazil’s Amazon Annually Since 2019

Rainforest Foundation Us’s Response to the Amazon Fires

Healthy communities can manage and protect their lands better than anyone. And healthy forests don’t burn.

Building on 35 years of steady, dedicated work with Indigenous partners in the Amazon and Central America, Rainforest Foundation US provides the tools, training, and resources to directly support in legal defense, land titling, and monitoring . We also partner and collaborate with Indigenous peoples and local communities to strengthen their organizations . This enables them—the best defenders of their rainforests—to continue to manage their lands with the knowledge and care they have sustained for thousands of years.

Throughout the Amazon, we are supporting partners to actively prevent and respond to the threat of fires by:

- Advancing land rights to over 6.6 million acres of Indigenous peoples’ territories in the Amazon regions of Peru, Brazil, and Guyana. Indigenous peoples with legal recognition of their lands are better able to protect them.

- Expanding Indigenous monitoring programs—some similar to our Rainforest Alert program in Peru—to over 19.5 million acres of tropical forest throughout Central and South America.

- Supporting Indigenous partners in Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Guyana, to raise over $5 million to strengthen their organizations.

How do Indigenous Peoples and Land Rights help prevent fires?

Indigenous peoples are the most effective forest stewards . Rainforests held by Indigenous peoples have fewer fires and lower fire temperatures, meaning they’re better able to resist forest loss. Data also shows that rainforests managed by Indigenous peoples contain greater carbon density than state-managed forests and foster higher levels of biodiversity. In other words, these forests are vital to our planet and play a crucial role in combating the climate crisis.

One of the best ways to protect the Amazon from destruction from fire, mining, industrial ranching, and illegal-logging is to secure and expand the land rights of Indigenous peoples living in these territories. Ensuring Indigenous peoples and local communities have rightful governance and control over their territories, as well as access to the necessary technology, training, and resources to manage and protect their territories is crucial to preventing fires and protecting the region’s biodiversity and cultural heritage.

The satellite map below displays real-time fires and Indigenous peoples’ lands. The majority of fires are observed outside Indigenous territories, typically ceasing at their boundaries.

Why Does the Rainforest Burn?

Tropical forests such as the Amazon are very humid, and under natural conditions they rarely burn—unlike many forests in the western United States where fire is a natural part of the forest’s life cycle.

In the last few decades, two interrelated phenomena have driven Amazon fires: drought, and the expansion of industrial agriculture.

Forests cleared for cattle ranching, agriculture, logging, or illegal mining are cut and then deliberately set on fire once the felled trees are dry enough to burn. Typically, the surrounding forest is wet enough to stop the fire at the edges of new fields and pastures. Typically, the surrounding forest is wet enough to stop the fires at the edges of new fields and pastures. But prolonged drought in the Amazon—linked to climate change and deforestation—means fires are escaping into neighboring primary forests and burning out of control across thousands of acres.

As more forests are cleared, new roads are built, and new fields are cleared for cattle and agriculture, a vicious cycle is created that both intensifies the drought and exposes more forests to fire threats and forest degradation.

Scientists warn this cycle is leading the entire Amazon basin towards a ‘tipping point,’ believed to occur when the combined effects of deforestation and degradation surpass a threshold of 20% to 25% . A study warns that the Amazon rainforest could reach this ‘tipping point’ by as soon as 2050. At that point, the world’s largest tropical forest would become so fragmented that it would no longer retain sufficient moisture to sustain itself, leading to catastrophic consequences for the global climate and life on Earth.

The Need for Coordinated Action

“We know that reducing deforestation and supporting Indigenous and local communities’ fire brigades is effective in both preventing and mitigating the impact of fires. However, with the Amazon in an extended drought and quickly approaching a tipping point, the scale of these fires presents a very new type of threat to the region. Protecting forests and traditional fire management practices will need to be reinforced with more systematic state measures, including accountability, emergency response planning, and aerial fire suppression,” suggests Cameron Ellis, Field Science Director of RFUS

The response to fires must be coordinated among various government agencies and institutions, with increasingly sophisticated accountability methods and increased fines.

“The mixture of climate change with El Niño contributes to highly flammable soil conditions, but the Amazon is not a biome that naturally burns. The response to fires in the Amazon should be a command-and-control strategy, with joint operations and rigorous penalties,” adds Christine Halvorson, Program Director of RFUS

Immediate actions are needed to protect this vital biome and its communities. And raising awareness about the severity of the situation and the need for immediate action to protect the Amazon is critical to ensuring a more sustainable future for the Amazon rainforest and its inhabitants.

Related News

Uniting for Wildlife: Highlights from a ‘TechCamp’ Workshop in the Peruvian Amazon

The city of Iquitos, Peru, hosted an event dedicated to the protection of Amazonian wildlife. Organized by Rainforest Foundation US, the Regional Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the East (ORPIO), and the Regional Organization AIDESEP Ucayali (ORAU), and with financial support from the U.S. Embassy in Peru and the World Resources Institute (WRI), the event brought together a diverse group of 55 participants.

Voices of Global Forest Watch: Wendy Pineda, RFUS Peru’s General Program Manager

Indigenous peoples are, without question, the most effective stewards of our forests. Now, imagine the transformative power when they have access to advanced tools that amplify their efforts to safeguard their lands. Check out this interview with Wendy Pineda Ortiz, General Project Manager of our Peru program, to learn how Indigenous peoples in the Peruvian Amazon are leveraging cutting-edge monitoring technology to fight deforestation.

The Ancestral Forest: How Indigenous Peoples Transformed the Amazon into a Vast Garden

For centuries, many people in the Western world believed the Amazon to be an unpopulated and untouched forest. This has never been entirely true. The Amazon has been managed by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. On this International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, explore how—through the creation of fertile soils and selecting and cultivating various plant and tree species over millennia—Indigenous peoples have transformed the Amazon rainforest into the most biodiverse ecosystem on Earth.

Support Our Work

Rainforest Foundation US is tackling the major challenges of our day: deforestation, the climate crisis, and human rights violations. Your donation moves us one step closer to creating a more sustainable and just future.

THE EARTH IS SPEAKING

Will you listen?

Now, through April 30th, your impact will be doubled. A generous donor has committed to matching all donations up to $15,000.

Any amount makes a difference.

Donate Today

Sign up today.

Get updates on our recent work and victories, stories from our Indigenous partners, and learn how you can get involved.

Technically defined as an enormous fire burning more than 100 square kilometers (38 square miles) of forest that occurs at the same time, in the same region and under the same climatic conditions, a megafire doesn’t necessarily need to be continuous. There may be multiple fire outbreaks. And it so happens that, at least in theory, they shouldn’t be happening in the humid tropical rainforest.

In a biome characterized by its intense humidity and trees that grow more than 50 meters (164 feet) in height, fire does not occur spontaneously. Usually accidental, forest fires in Amazonia are caused by uncontrolled small fires such as crop burning, livestock management (to clear pasture) or clear-cutting — this, which is almost always illegal, resulting from razing trees for new pastureland, monoculture farming or real estate speculation. What is certain is that all types of fire in the Amazon Rainforest are anthropic, meaning humans caused them.

According to Lancaster University researcher Jos Barlow, there is more than one type of forest fire. “There are wildfires when a forest burns for the first time: Usually it is low-burning, spreads slowly and can even be difficult to detect via satellite. Yet it still has a great impact on the forest and kills many species adapted to that dark understory,” explains Barlow, who has been working in Amazonia for two decades. “And there are fires [that start] when the forest has already been degraded by selective logging or a previous fire. These more degraded forests burn more intensely and the fire spreads faster.”

The issue is that fires in Amazonia are unlike those in other biomes. In the Brazilian Cerrado, for example, the trees have thick bark and are more resistant. Many species manage to resprout after a fire. But Amazonian trees are covered in thinner bark that offers no resistance to fire. Forest fires leave scars in Amazonia. But what happens when the marks left in the rainforest are overproportional?

Megafires in the Brazilian Amazon

Satellite imagery gathered by MapBiomas (1998, 2005 and 2015) and the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Biospheric Sciences Lab (2023) show the scope of megafires in different states in the Brazilian Amazon over the last 25 years and the conservation units most affected by the fires:

- 1998, Roraima state, 1,765 km2 (681 mi2), Roraima National Forest, Maracá Ecological Station and the Yanomami Indigenous Territory;

- 2005, Acre state, 427 km2 (165 mi2), Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve;

- 2015, Maranhão state, 2,200 km2 (850 mi2), Arariboia Indigenous Territory;

- 2015, Pará state, 9,820 km2 (3,790 mi2), Tapajós National Forest and Tapajós-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve;

- 2023, Pará state, 2,592 km2 (1,000 mi2), Flona Tapajós National Forest and Tapajós-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve.

Fire at the foot of the Andes

In December 2023, Douglas Morton, who runs NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s Biospheric Sciences Lab, met with Ambiental Media’s geo-journalism team. During the meeting, he shared images from his computer screen detailing the multitude of fire outbreaks in the eastern part of Tapajós National Forest in the Santarém region. “It’s an enormous area. We’re talking about 2,000 km2 [772 mi2] that have been burning for a month and a half.” Researchers from the Sustainable Amazonia Network [Rede Amazônia Sustentável] explain that the rainforest surrounding Santarém and along the Bolivian border with the Brazilian states of Acre and Rondônia are burning this year at such high proportions that it has been characterized as a megafire.

“There are megafires burning in all the forests near the foot of the Andes in Bolivia. Almost everything is on fire,” Barlow says. “To get an idea, there is one single fire covering 727 km2 [280 mi2]. This is just one fire, but it has run together with several other enormous fires.”

According to scientists, megafires are a result of an El Niño year paired with the driest period, causing the most severe drought seen in the last 40 years in Amazonia . The worsening effects of climate changes, rainforest degraded areas and low river and groundwater levels (like those seen in 2023) contributed to the spread of wildfires.

“When you have a drought year, both small farmers and large landowners lose control of fires,” says Liana Anderson, a researcher at the National Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning [Centro Nacional de Monitoramento e Alertas de Desastres Naturais] (CEMADEN). “We see a larger percentage of forests burned within large properties. This shows we have vulnerability in rural areas.”

According to CEMADEN data, the scenario will remain worrisome into 2024. El Niño’s effects that favor fires — a lower tendency for rainfall and higher than average temperatures for the period — peaked in December 2023.

“It seems to me that this year is the most intense of all my years working in this national forest, more intense than 2015 and 2016, which were the other El Niño years,” states Marcos Oliveira, a firefighter with ICMBio, the environment ministry’s office overseeing protected areas who is currently combating the wildfires in the Tapajós National Forest. “We managed to control some burns, but in others we needed to call in brigades from outside to get the job done.”

A cover article in Science magazine from the beginning of 2023 states that 38% of the Amazon Rainforest is degraded, meaning that it’s already showing gradual loss of vegetation and no longer provides the same environmental services as intact forest. This means that the Amazon is weakened and more vulnerable to recurring and extreme climate events, and also too dry to prevent fire from spreading.

In a well-preserved Amazonia, our feet make no sound as we walk through the forest, even during the dry season. Despite the dry weather, the litterfall — the layer of nonliving organic debris that accumulates on the forest floor — remains moist. Such is not the case in a forest that has burned. “When you walk, you can hear the leaves: crunch, crunch, crunch,” describes Barlow. “It’s impressive; a totally different experience. It’s much drier, and the leaves and branches from trees that have already died make up a layer of fuel for fires.”

The first wildfire that passes through an area of the rainforest in Amazonia can kill nearly half of the trees. For many subsequent years, the largest trees continue to die because the fire has weakened them and they are more vulnerable to disease, fungi and termites. When they fall, they kill adjacent young trees in a sort of domino effect. So, one of the results, or scars, left on the forest is that it becomes more open, like Swiss cheese, in Berenguer’s words.

When observing the parts of the forest that burned just eight years ago during the 2015 El Niño, Berenguer says, the landscape is different, with more so-called pioneer trees, which are the first to appear in degraded areas. “These are the trees that grow even in vacant lots; they’ll grow anywhere. One is a very common genus, the embaúbas , which in the Tupi language means ‘hollow tree.’”

She also comments that she has noticed a difference in the megafire burning today: It is burning vertically. “In these areas with many embaúbas — the areas that burned in the last El Niño [2015] — we are seeing flames that at times reach 10 m (32 ft) in height. Apparently, the fire is traveling more rapidly and is larger than we had seen before, causing the deaths of even more individuals.”

It so happens that the fires have not been occurring exclusively in previously burned areas nor in areas directly related to clear-cutting. Researchers are concerned that right now, any fire at all could quickly get out of control because the entire landscape is flammable.

“It’s important to point out that, in a year like 2023, we are seeing more forest fires in areas where there has been less deforestation,” says Morton. “This is because fire is being widely used for other purposes.”

A study carried out in Acre shows that climate extremes previously felt in the region at 50-year intervals are now felt every year. And many different events are happening every year. “We are having a collapse caused by many concurrent events, each of which is greatly damaging,” says Sonaira Silva, researcher at Acre Federal University.

Just like this year, the 2015 Pará megafire burned not only in areas that had undergone previous disturbances, but also in areas of intact rainforest. Berenguer says that 2015 was a window on a future reality, pointing out that fire knows no boundaries.

Keeping forests from burning

Specialists trust the fire watch data generated in Brazil. Aside from government data, some private and third-sector organizations are also working to observe the situation. “The geotechnical work being done at institutions that are developing monitoring systems is quite commendable,” states Anderson.

The more specific the data, the better they are for creating prevention policies. Anderson mentions the Amazonia Fire Calendar, containing data on the time of year in which each region in the Amazon becomes more vulnerable to fire. “This type of information is very important for policy planning and decision-making,” she says.

However, preventing fires continues to be a challenge because most of the funding is allocated to fighting already existing fires. Specialists say employees should be hired to exclusively monitor satellite imagery so that reaction times can be reduced when a fire breaks out. “Firefighting is part of it, but it’s not the solution in and of itself. It’s a bandage that falls off the first time anyone starts to sweat,” says Barlow. “We must find ways to keep the forests from catching fire in the first place.”

An even more effective prevention tool would be the sort of work done by Joaquim Parimé, head of the IBAMA Environmental Emergency and Forest Fire Nucleus in Roraima. Since 2015, Parimé has been developing work with Indigenous communities that focuses on integrated fire management, prescribed burning, controlled burning and creating firebreaks in strategic microsystems. And wildfires have ceased in the locations where the project was put in place.

“The results have been very encouraging in the regions belonging to Indigenous people. These populations have revived ancestral uses of fire to manage their landscapes. They use fire to maintain the ecosystem, they use fire as a tool to preserve. They use good fire, benevolent fire, fire that protects.”

Joice Ferreira is a researcher at Embrapa Eastern Amazon and the co-author of a document delivered to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change that aims to improve the policies included in the Plan of Action for Deforestation Prevention and Control in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm). She also suggests that an emergency fund to prevent and fight fires in extremely dry years should be created.

“The fund could provide funding in critical regions so they [family farmers] don’t plant their gardens. It would protect the area, a sort of food grant during a season when families weren’t allowed to plant crops,” the biologist suggests. “Once a fire spreads, it’s much more difficult to contain and creates enormous costs, both environmentally and socially.”

Megafires are hard to fight. Aside from being voluminous, they spread through parts of the forest with limited access. Sometimes they are only really extinguished when the rainy season comes around again. “We are in the field all the time. Four days of rain is no help; a day later, everything is dry again and catching fire,” says Ralph Cohen, head of the ICMBio firefighting brigade in the Tapajós National Forest. “There are many Indigenous areas, many communities. We are working to protect these areas. And the fire this year was very intense. Very, very intense.”

Cohen says he fears losing the rainforest more than he fears fire. Snakes, sloths, coatis and tortoises are the animals he most finds in agony. “We find many, many animals. We find them trying to run away, dead, injured. It’s heartbreaking.”

People and nature suffer as historic drought fuels calamitous Amazon fires

This story was first published in Portuguese by Ambiental Media and produced in partnership with the Sustainable Amazon Network (RAS).

Banner image of a megafire in western Pará state in November 2023. Image courtesy of Marizilda Cruppe/RAS.

To wipe or to wash? That is the question

Toilet paper: Environmentally impactful, but alternatives are rolling out

Rolling towards circularity? Tracking the trace of tires

Getting the bread: What’s the environmental impact of wheat?

Consumed traces the life cycle of a variety of common consumer products from their origins, across supply chains, and waste streams. The circular economy is an attempt to lessen the pace and impact of consumption through efforts to reduce demand for raw materials by recycling wastes, improve the reusability/durability of products to limit pollution, and […]

Free and open access to credible information

Latest articles.

In Mexico, avocado suppliers continue sourcing from illegally deforested land

Indonesian Islamic behemoth’s entry into coal mining sparks youth wing revolt

Indonesia expands IPLC land recognition — but the pace is too slow, critics say

One year after oil referendum, what’s next for Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park?

In the DRC, a government commission is taking funds owed to people relocated by mines

Conserving & restoring waterways can mitigate extreme urban heat in Bangladesh

Arctic melt ponds influence sea ice extent each summer — but how much?

3D ‘digital twin’ rainforest maps could help reforestation programs in Costa Rica

you're currently offline

- Environment

Everything you need to know about the fires in the Amazon

Why are the fires burning and why is it such a big deal.

By Justine Calma , a senior science reporter covering climate change, clean energy, and environmental justice with more than a decade of experience. She is also the host of Hell or High Water: When Disaster Hits Home, a podcast from Vox Media and Audible Originals.

Share this story

If you buy something from a Verge link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19125948/1164446768.jpg.jpg)

Record-breaking fires are ripping through the Amazon — an ecosystem on which the whole world depends. The Verge will update this page with news and analysis on the fires and the effects that could linger once the ash settles.

Table of Contents:

Why is the Amazon burning?

Why is this a big deal?

Why is this a hot topic politically?

- How are the fires being fought?

An unprecedented number of fires raged throughout Brazil in 2019, intensifying in August. That month, the country’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) reported that there were more than 80,000 fires, the most that it had ever recorded. It was a nearly 80 percent jump compared to the number of fires the country experienced over the same time period in 2018. More than half of those fires took place in the Amazon.

The number of blazes decreased in September , after president Jair Bolsonaro bowed to mounting pressure to address the flames and announced a 60-day ban on setting fires to clear land. Some exceptions were made for indigenous peoples who practice subsistence agriculture and those who’ve received clearance by environmental authorities to use controlled burning to prevent larger fires.

“There is no doubt that this rise in fire activity is associated with a sharp rise in deforestation”

“These are intentional fires to clear the forest,” Cathelijne Stoof, coordinator of the Fire Center at Wageningen University (WUR) in the Netherlands, tells The Verge . “People want to get rid of the forest to make agricultural land, for people to eat meat.” The INPE found that deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon hit an 11-year high in 2019.

“There is no doubt that this rise in fire activity is associated with a sharp rise in deforestation,” Paulo Artaxo, an atmospheric physicist at the University of São Paulo, told Science Magazine . He explained that the fires are expanding along the borders of new agricultural development, which is what’s often seen in fires related to forest clearing.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, which had pledged to open up the Amazon to more development, has sought to shift attention away from deforestation. Bolsonaro initially pointed a finger at NGOs opposing his policies for allegedly intentionally setting fires in protest, without giving any evidence to back his claim. In August, he fired the director of the National Institute for Space Research over a dispute over data it released showing the sharp uptick in deforestation that’s taken place since Bolsonaro took office. On August 20th, Brazil’s Minister of the Environment Ricardo Salles tweeted that dry weather, wind, and heat caused the fires to spread so widely. But even during the dry season, large fires aren’t a natural phenomenon in the Amazon’s tropical ecosystem.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19126415/1163385128.jpg.jpg)

Everyone on the planet benefits from the health of the Amazon. As its trees take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen, the Amazon plays a huge role in pulling planet-warming greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere. Without it, climate change speeds up. But as the world’s largest rainforest is eaten away by logging, mining, and agribusiness, it may not be able to provide the same buffer.

“The Amazon was buying you some time that it is not going to buy anymore,” Carlos Quesada, a scientist at Brazil’s National Institute for Amazonian Research, told Public Radio International in 2018. Scientists warn that the rainforest could reach a tipping point , turning into something more like a savanna when it can no longer sustain itself as a rainforest. That would mean it’s not able to soak up nearly as much carbon as it does now. And if the Amazon as we know it dies, it wouldn’t go quietly. As the trees and plants perish, they would release billions of tons of carbon that has been stored for decades — making it nearly impossible to escape a climate catastrophe.

Everyone on the planet benefits from the health of the Amazon

Of course, those nearest to the fires will bear the most immediate effects. Smoke from the fires got so bad, it seemed to turn day into night in São Paulo on August 20th. Residents say the air quality is still making it difficult to breathe. On top of that, a massive global study on air pollution found that among the two dozen countries it observed, Brazil showed one of the sharpest increases in mortality rates whenever there’s more soot in the air.

And because fire isn’t a natural phenomenon in the region, it can have outsized impacts on local plants and animals. One in ten of all animal species on Earth call the Amazon home, and experts expect that they will be dramatically affected by the fires in the short term . In the Amazon, plants and animals are “exceptionally sensitive” to fire, Jos Barlow, a professor of conservation science at Lancaster University in the UK, said to The Verge in an email. According to Barlow, even low-intensity fires with flames just 30 centimeters tall can kill up to half of the trees burned in a tropical rainforest.

When Jair Bolsonaro was campaigning for office as a far-right candidate, he called for setting aside less land in the Amazon for indigenous tribes and preservation, and instead making it easier for industry to come into the rainforest. Since his election in October 2018, Bolsonaro put the Ministry of Agriculture in charge of the demarcation of indigenous territories instead of the Justice Ministry, essentially “letting the fox take over the chicken coop,” according to one lawmaker . His policies have been politically popular among industry and agricultural interests in Brazil, even as they’ve been condemned by Brazilian environmental groups and opposition lawmakers. Hundreds of indigenous women stormed the country’s capital on August 13th to protest Bolsonaro’s environmental rollbacks and encroachment of development on indigenous lands. The hashtag #PrayforAmazonia blew up on Twitter.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19126393/1161492194.jpg.jpg)

About 60 percent of the Amazon can be found within Brazil’s borders, which gives the nation a massive amount of influence over the region. Not surprisingly, the fires have called international attention to the plight of the Amazon and have turned up the heat on Bolsonaro’s environmental policies.

French President Emmanuel Macron took to Twitter to call for action, pushing for emergency international talks on the Amazon at the G7 summit. On August 26th, the world’s seven largest economies offered Brazil more than $22 million in aid to help it get the fires under control. Bolsonaro promptly turned down the money, accusing Macron on Twitter of treating Brazil like a colony. Some in Brazil, including Bolsonaro, see the international aid as an attack on Brazil’s sovereignty , and its right to decide how to manage the land within its borders.

“Letting the fox take over the chicken coop”

President Donald Trump, on the other hand, congratulated Bolsonaro on his handling of the fires. “He is working very hard on the Amazon fires and in all respects doing a great job for the people of Brazil,” he tweeted on the 27th.

Bolsonaro has since said that he’ll reconsider the deal, as long as Macron takes back his “ insults ” and Brazil has control over how the money is spent. On the 27th, Bolsonaro accepted $12.2 million in aid from the UK.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19126423/1164459408.jpg.jpg)

How are the fires being fought?

After weeks of international and internal pressure, Bolsonaro deployed the military to help battle the fires on August 24, sending 44,000 troops to six states. Reuters reported the next day that warplanes were dousing flames.

“It’s a complex operation. We have a lot of challenges,” Paulo Barroso tells The Verge. Barroso is the chairman of the national forest fire management committee of the National League of Military Firefighters Corps in Brazil. He has spent three decades fighting fires in Mato Grosso, one of the regions most affected by the ongoing fires. According to Barroso, more than 10,400 firefighters are spread thin across 5.5 million square kilometers in the Amazon and “hotspots” break out in the locations they’re unable to cover.

“We don’t have an adequate structure to prevent, to control, and to fight the forest fires”

Barroso contends that they need more equipment and infrastructure to adequately battle the flames. There are 778 municipalities throughout the Amazon, but according to Barroso, only 110 of those have fire departments. “We don’t have an adequate structure to prevent, to control, and to fight the forest fires,” Barroso says. He wants to establish a forest fire protection system in the Amazon that brings together government entities, indigenous peoples, local communities, the military, large companies, NGOs, and education and research centers. “We have to integrate everybody,” Barroso says, adding, “we need money to do this, we have to receive a great investment.”

Barroso and other experts agree that it’s important to look ahead to prevent fires like we’re seeing now. After all, August is just the beginning of Brazil’s largely manmade fire season, when slashing-and-burning in the country peaks and coincides with drier weather.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19126433/1163748175.jpg.jpg)

Controlled burns are also a popular deforestation technique in other countries where the Amazon is burning, including Bolivia . There, the government brought in a modified Boeing 747 supertanker to douse the flames.

Using planes to put out wildfires in the Amazon isn’t a typical method of firefighting in tropical forests, and is likely to get expensive, Lancaster University’s Jos Barlow tells The Verge . He says that large-scale fires in areas cleared by deforestation “are best contained with wide firebreaks created with bulldozers — not easy in remote regions.” If the fires enter the forest itself, they require different tactics. “They can normally be contained by clearing narrow fire breaks in the leaf litter and fine fuel,” Barlow says. “But this is labour intensive over large scales, and fires need to be reached soon, before they get too big.”

Fires that have been intentionally set, as we’re seeing in Brazil, can be even more difficult to control compared to a sudden wildland fire. “They’re designed to be deliberately destructive,” says Timothy Ingalsbee, co-founder and executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology and research associate at the University of Oregon. Slashing before burning produces a lot of very dry, very flammable fuel. And at this scale, Ingalsbee calls the fires “an act of global vandalism.”

Barlow says, “The best fire fighting technique in the Amazon is to prevent them in the first place — by controlling deforestation and managing agricultural activities.”

WUR’s Cathelijne Stoof agrees: “Fighting the fires is of course important now,” she says. “For the longer term, it is way more important to focus on deforestation.”

The Acolyte has been canceled

The ftc’s noncompete agreements ban has been struck down, sonos ceo says the old app can’t be rereleased, microsoft teams’ new single app for personal and work is now available, valve bans razer and wooting’s new keyboard features in counter-strike 2.

More from Science

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23935561/acastro_STK103__04.jpg)

Amazon — like SpaceX — claims the labor board is unconstitutional

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25288452/246992_AI_at_Work_REAL_COST_ECarter.png)

How much electricity does AI consume?

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25287681/1371856480.jpg)

A Big Tech-backed campaign to plant trees might have taken a wrong turn

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25287408/2003731596.jpg)

SpaceX successfully launches Odysseus in bid to return US to the lunar surface

Trouble in the Amazon

The rainforest is starting to release its carbon.

Is it heading towards a tipping point?

24 August 2023

By Daniel Grossman

Photographs by Dado Galdieri/Hilaea Media for Nature

Video by Patrick Vanier/Hilaea Media for Nature

Climate change, deforestation and other human threats are driving the Amazon towards the limits of survival.

Researchers are racing to chart its future.

The Pulitzer Center in Washington DC supported travel for Daniel Grossman and for photographer Dado Galdieri and videographer Patrick Vanier.

This article is also available as a pdf version .

Luciana Gatti stares grimly out of the window of the small aircraft as it takes off from the city of Santarém, Brazil, in the heart of the eastern Amazon forest. Minutes into the flight, the plane passes over a 30-kilometre stretch of near-total ecological devastation. It’s a patchwork of farmland, filled with emerald-green corn stalks and newly clear-cut plots where the rainforest once stood.

“This is awful. So sad,” says Gatti, a climate scientist at the National Institute for Space Research in São José dos Campos, Brazil.

Gatti is part of a broad group of scientists attempting to forecast the future of the Amazon rainforest. The land ecosystems of the world together absorb about 30% of the carbon dioxide released by burning fossil fuels; scientists think that most of this takes place in forests, and the Amazon is by far the world’s largest contiguous forest.

Rows of black-pepper plants grow in a field near Santarém that was formerly rainforest.

Since 2010, Gatti has collected air samples over the Amazon in planes such as this one, to monitor how much CO 2 the forest absorbs. In 2021, she reported data from 590 flights that showed that the Amazon forest’s uptake — its carbon sink — is weak over most of its area 1 . In the southeastern Amazon, the forest has become a source of CO 2 .

The finding gained headlines around the world and surprised many scientists, who expected the Amazon to be a much stronger carbon sink. For Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist at the University of São Paulo Institute of Advanced Studies in Brazil, the change was happening much too soon. In 2016, using climate models, he and his colleagues predicted that the combination of unchecked deforestation and global climate change would eventually push the Amazon forest past a “tipping point” , transforming the climate across a vast swathe of the Amazon 2 . Then, the conditions that support a lush, closed-canopy forest would no longer exist. Gatti’s observations seem to show the early signs of what he forecast, Nobre says.

A dealership for the farming equipment company John Deere sits at the edge of the rainforest in Santarém.

“What we were predicting to happen perhaps in two or three decades is already taking place,” says Nobre, who was one of a dozen co-authors of the paper with Gatti.

I’ve travelled to Santarém, where the Tapajós River joins the Amazon River, to join Gatti and other scientists trying to determine whether the forest is heading for an irreversible transformation towards a degraded form of savannah. Another big question is whether the forest can still be saved by slowing climate change, halting Amazon deforestation and restoring its damaged lands, something Nobre suggests is possible.

The large-scale deforestation we saw from the air is the most visible threat to the Amazon. But the forest is suffering in other, less-obvious ways. Erika Berenguer, an ecologist at the University of Oxford and Lancaster University, UK, has found that even intact forest is no longer as healthy as it once was, because of forces such as climate change and the impacts of agriculture that spill beyond farm borders. Earlier this year, a large international team of researchers, including Berenguer, reported that such changes were having effects across 38% of the intact Amazon forest 3 .

Gatti first visited Santarém in the late 1990s, when most of the farming in this part of the Amazon was practised by smallholders for subsistence purposes. Now, she’s astounded by the scale of destruction that has ravaged the jungle. While passing over one huge, newly razed parcel of Amazon forest, Gatti’s voice crackles over the plane’s intercom. “They are killing the forest to transform everything into soy beans.”

Breath of the forest

The plane that collects air samples for Gatti is housed in a cavernous hangar at Santarém airport. On a rainy day in May, she visits the hangar to meet with Washington Salvador, one of her regular pilots. Gatti checks on the rugged plastic suitcases she has had shipped to Santarém and stored in her tiny office at the airport. Inside them, cradled in foam, are 12 sturdy glass flasks the size and shape of one-litre soft-drink bottles.

Luciana Gatti (right) prepares for a flight that will collect air samples over the Amazon forest.

Climate scientist Luciana Gatti stands at the top of a tower above the canopy, watching one of the aeroplanes that collects air samples over the forest.

Luciana Gatti discusses threats to the rainforest.

The problem is that we are advancing a lot in deforestation.

There is a moratorium that is not being obeyed.

When we compare the size of the deforested area from 2010 to 2018 and look at the years 2019 and 2020, which were part of the Bolsonaro government, we see an increase in 70% of planted areas for soy, 60% for corn and 13% for cattle raising.

So a very large increase is happening.

The moratoriums, the agreements are not being respected.

Gatti doesn’t need to accompany Salvador when he collects the samples. That’s fortunate, because she gets air sick flying in small planes. The pilots who work with her fly twice a month to a specific sampling location, one in each quadrant of the Amazon basin. Once they reach an altitude of 4,420 metres over a landmark, the pilot presses a button, opening valves and turning on a compressor that fills the first flask with air taken through a nozzle from outside. Then, they dive in a steep, tight spiral centred around the landmark, collecting 11 more samples, each at a specified altitude. At the final level, the pilot practically buzzes the canopy, sometimes barely 100 metres above the ground.

In her laboratory at the National Institute for Space Research, Gatti measures the amount of CO 2 in the samples. She calculates how much the forest soaks up (or releases) by comparing her measurements with those taken over the Atlantic Ocean, which is upstream of the trade winds that blow over the Amazon.

This patch of the rainforest in the eastern Amazon has been carved up into an array of fields. (Video contains the sound of an aeroplane engine).

Flasks used for sampling air above the rainforest. Luciana Gatti and her colleagues use these samples to determine how carbon dioxide moves into and out of the forest.

Scott Denning, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins who has collaborated with Gatti, says that her research has been an “amazingly logistically difficult project”. “The beauty of Luciana’s work, and also the difficulty of her work, is that she’s done it over and over and over again, every two weeks for ten years.”

Fading forest

Air samples taken over the Amazon rainforest at five sites (orange dots) track the movement of carbon dioxide into and out of the forest between 2010 and 2018. By measuring the total flow of carbon (black) and subtracting that released by fires (grey), researchers calculate the net flux (orange). Negative values indicate carbon sinks — areas that absorb more than they naturally emit. The southeast has become a carbon source, releasing more than it absorbs.

Carbon movement

Flux from fire

Total carbon flux

Forest cover

Regional carbon flux

(grams of carbon

per square metre per day)

Measurement sites

Nature publications remain neutral with regard to contested jurisdictional claims in published maps.

Source: Ref. 1

Regional carbon flux (grams of carbon

Lax enforcement

Some of the forces transforming the Amazon biome are on display at Santarém’s port, where a trio of eight-storey-high silos looms over the city’s fish market. Each silo can hold 18,000 tonnes of maize (corn) or soya beans, waiting to be shipped to other parts of Brazil and then around the globe. As of 2017, more than 13% of the Amazon’s old-growth forest had been cleared, largely for ranching and for growing crops. Almost two-thirds of the biome is in Brazil, which had lost more than 17% of such forest by that year, and its deforestation rates surged in 2019 during the administration of former president Jair Bolsonaro.

A trio of grain silos stands near the edge of Santarém.

Brazil’s Forest Code is supposed to protect the country’s woods. One key provision requires that in the Amazon, 80% of any plot, a portion known as the Legal Reserve, must be left intact. But many scientists and forest activists argue that lax enforcement makes it too easy to circumvent the law, and that fines for not complying aren’t effective deterrents because they are rarely paid.

Also, people often get title to public or Indigenous land that they illegally occupy and clear, through a process called land grabbing. Philip Fearnside, an ecologist at Brazil’s National Institute for Research in Amazonia in Manaus, says, “Brazil is basically the only country where you can still go into the forest and start clearing and expect to come out with a land title. It’s like the Wild West of North America in the eighteenth century.”

After a one-hour drive south from Santarém, we meet the Indigenous chief — the cacique — of the tiny village of Açaizal in the reservation known as Terra Munduruku do Planalto. He sits on a deck at a rough-hewn wooden table, positioned so he can watch for unwanted outsiders who might drive past.

Josenildo Munduruku, leader of his tribe, in a school with some of his students.

Josenildo Munduruku — as is customary, his surname is the same as his tribe — says that decades ago, non-Indigenous homesteaders began establishing smallholdings on land that he and his ancestors had occupied for generations. He says that they built houses and opened up cattle pastures without ever asking permission or obtaining legal rights. Previous generations of his community didn’t object. “Our parents did not have this type of understanding — they were not concerned about it,” he says.

The land eventually ended up in the hands of commercial growers, who buy up adjacent plots then raze huge swathes of jungle. “They do not care about these trees from which we extract medicine. For them, these trees are meaningless, useless,” says Munduruku. He says that his community has tried unsuccessfully to get help from the government to recover some of the land.

Maize (corn) grows in a field in the Munduruku territory next to intact rainforest.

A farmer harvests a field in a deforested area near Santarém.

The high value of some tropical hardwoods also threatens the forest. Off a highway just west of Açaizal, a timber-mill worker sends a massive log through an industrial saw, which slices off a plank as thick as an encyclopedia. Other workers shape the rough board into standard dimensions.

Ricardo Veronese, the timber mill’s owner, says that his family members, a small lumber dynasty, came to the state of Pará from Mato Grosso state 17 years ago. “We came to Pará because there was plenty of virgin forest left,” he says. The situation in Mato Grosso is different: since the mid-1980s, roughly 40% of its rainforest has been cut down 4 .

Every year, Veronese’s mill saws up about 2,000 giant trees, mostly for high-end flooring and porch decks in the United States and Europe. With obvious pride, he says that he takes only “sustainably harvested” wood. The huge trunks, stacked by the score in a yard, come from state-regulated logging operations that practise selective logging, he says, where only large trees are cut, leaving the remaining trees to grow and fill gaps in the canopy. And he says that his company follows the government’s rules for selective logging, which require firms to take steps to reduce their impact.

But many ecologists say that the selective logging permitted by the Forest Code is often not sustainable. That’s because the trees that are removed are generally slow-growing species with dense wood, whereas the species that grow back have less-dense wood, so they absorb less carbon in the same space. And few companies follow the requirements for selective logging , such as limiting road construction or the number of trees cut. “About 90% of selective logging in the Amazon is estimated as illegal, and therefore doesn’t follow any of these procedures,” says Berenguer.

A sawmill processes logs from the rainforest on the outskirts of Santarém.

Carbon counting

It takes patience and perseverance to monitor the Amazon for long periods. Berenguer and her team have been measuring 6,000 trees in the Tapajós National Forest every three months since 2015. From this, they estimate changes in the amount of biomass in the forest, and how much carbon is stored there 5 .

Censuses such as these, and atmospheric measurements such as Gatti’s, are two common techniques climate scientists use to study the uptake and release of carbon. Each has strengths and drawbacks.

The censuses directly measure the amount of carbon (in the form of wood) in a forest. If paired with measurements of debris on the ground and CO 2 released from soil, they can also take account of decay. But censuses look only at a limited number of sites. Atmospheric measurements can assess the combined impact of changes in forests at regional and even continental scales. But it’s hard to decipher the cause of any changes they show.

In 2010, Berenguer began monitoring more than 20 plots in and around the Tapajós forest. Her goal was to compare the carbon uptake of primary forest with that of jungle degraded by selective logging — legal and otherwise. But in 2015, an unprecedented heat wave and drought hit the eastern Amazon.

Eight of Berenguer’s plots were burnt, killing hundreds of trees that she’d measured at least twice. She recalls the day in 2015 that she visited a recently scorched plot. Her assistant, Gilson Oliveira, had run ahead. “And he just started screaming, ‘Oh tree number 71 is dead. Tree number 114 is burning,’” Her equipment was destroyed. Some favourite trees had died. “I just collapsed crying; just sat down in the ashes.”

Under normal conditions, the Amazon forest is almost fireproof. It’s too wet to burn. But by the time this long dry season ended, fires had scorched one million hectares of primary forest in the eastern Amazon, an area the size of Lebanon, killing an estimated 2.5 billion trees and producing as much CO 2 as Brazil releases from burning fossil fuels in a year 5 . Some of Berenguer’s research was, literally, reduced to ashes. Still, she saw the chance to study a problem that is expected to become increasingly common: the combined effect of multiple issues, such as severe drought, fires and human degradation caused by selective logging and clear-cutting.

A patch of former rainforest in the Munduruku territory has been cleared of trees and will be burnt before it is planted. The impacts and fires spread into the rainforest beyond the edge of the field.

On a tour of where Berenguer’s team works in the Tapajós forest, her field director, Marcos Alves, takes us to a site that burnt in 2015. Not long before the fire, illegal loggers removed the biggest, most economically valuable trees. The forest has grown back with plenty of vegetation, including some fast-growing species that are already as thick as telephone poles. But there are none of the giants that can be found elsewhere in the forest.

Alves and Oliveira take Gatti and me to a site three kilometres up the highway that has never been selectively logged or clear cut, and which escaped the 2015 fires. It’s dimmer here because the high canopy is so thick. And it’s noticeably cooler: not only do the trees block sunlight, but they also transpire vast quantities of water, which chills the air.

Gatti marvels at the size of a Brazil-nut tree ( Bertholletia excelsa ) that forms part of the canopy. “It’s amazing! How much water this tree puts into the air.”

Luciana Gatti stands between the buttresses of a giant samauma tree ( Ceiba pentandra ), which she often visits on trips to the eastern Amazon.

In 2021, Berenguer and a team of co-authors from Brazil and Europe published a study 5 of carbon uptake and tree mortality in her plots during the first three years after the 2015–16 burning. They compared plots that had been selectively logged or had burnt in the years before 2015–16, with ones that had not been logged or burnt. The study found that more trees died in degraded plots.

Although plots that weren’t degraded fared the best in her study, Berenguer says that there is no such thing as “pristine forest” any more. Climate change has warmed the entire Amazon forest by 1 °C in the past 60 years. The eastern Amazon has warmed even more.

Amazon rainfall has not changed appreciably, when averaged over the year. But the dry season, when rain is needed most, is becoming longer, especially in the northeastern Amazon, where dry-season rainfall decreased by 34% between 1979 and 2018 1 . In the southeastern Amazon, the season now lasts about 4 weeks longer than it did 40 years ago, putting stress on trees, especially the big ones. Still, Berenguer says that, so far, the measurable effects of climate change on the forest are relatively subtle compared with those of direct human impacts such as logging.

Fading forests

David Lapola, an Earth-system modeller at Brazil’s University of Campinas, says that deforestation alone can’t explain why the Amazon carbon sink has weakened — and has reversed in the southeast. He and more than 30 colleagues, including Gatti and Berenguer, published an analysis this year noting that carbon emissions resulting from degradation equal — or exceed — those from clear-cutting deforestation 3 .

Widespread threats

The area of intact Amazon forest that has been degraded by different forces exceeds the area that has been deforested by clear-cutting. Three main drivers of degradation are fires, selective timber extraction and edge effects that harm the forest near areas that have been cleared or burnt. Severe droughts can also cause degradation.

5.5% of total remaining Amazon forest degraded

Fire, edge effects

and timber extraction

Deforestation

Forest degradation

2001–18 (thousand km 2 )

Number of severe

Area affected by selective timber

Extent of edge effects

(km 2 , log scale)

extraction (km 2 , log scale)

droughts 2001–18

Source: Ref. 3

Area affected by

selective timber

5.5% of total

remaining Amazon forest degraded

Number of severe droughts 2001–18

Area burnt (km 2 , log scale)

Extent of edge effects (km 2 , log scale)

What’s more, even intact forest with no obvious local human impacts is accumulating less carbon than it used to, as seen in some tree-census studies. A 2015 analysis 6 of 321 plots of Amazon primary forest with no overt human impacts reported “a long-term decreasing trend of carbon accumulation”. A similar study 7 published in 2020 reported the same things in the Congo Basin forest — the world’s second-largest tropical jungle.

That’s a change from previous decades, when censuses indicated that such primary forest in the Amazon was storing more carbon. There is no consensus explanation for these slowdowns, or why primary forest was accumulating carbon. But many researchers suspect that the carbon gains in previous decades stem from the influence of extra CO 2 in the atmosphere, which can stimulate the growth of plants. In some studies that expose large forest plots to elevated CO 2 , known as free-air carbon enrichment (FACE) experiments, researchers have measured gains in biomass. But this effect lasted only a few years in one experiment 8 , and other studies have not yet determined whether the gains are temporary.

All of the forest FACE experiments have so far been conducted in temperate regions, however. And many scientists suspect that tropical forests — and the Amazon, in particular — might follow different rules. The first tropical-forest FACE experiment is finally under construction, 50 kilometres north of Manaus. Nobre says that it could help to predict whether continued increases in CO 2 will benefit the Amazon.

For several decades, Nobre and his students have used computer models to forecast how climate change and deforestation will affect the Amazon. The research grew, in part, from work in the 1970s showing that the Amazon forest itself helps to create the conditions that nourish it 9 . Moisture blowing in from the Atlantic falls as rain in the eastern Amazon and is then transpired and blown farther west. It recycles several times before reaching the Andes. A smaller or seriously degraded forest would recycle less water, and eventually might not be able to support the lush, humid forest.

In their 2016 study 2 , Nobre and several colleagues estimated the Amazon would reach a tipping point if the planet warms by more than 2.5 °C above pre-industrial temperatures and if 20–25% of the Amazon is deforested. The planet is on track to reach 2.5 °C of warming by 2100, according to a report released by the United Nations last October .

Nobre now wonders whether his earlier study was too conservative. “What Luciana Gatti’s paper shows is that this whole area in the southern Amazon is becoming a carbon source.” He is convinced that, although the Amazon is not at the tipping point yet, it might be soon.

Susan Trumbore, director of the Max Planck Institute of Biogeochemistry in Jena, Germany, is not a fan of using the term tipping point, a phrase with no precise definition, to discuss the Amazon. But she says that the forest’s future is in question. “We all think of a tipping point as it’s going to happen and it’s going to happen fast. I have a feeling that it’s going to be a gradual alteration of the ecosystem that we know is coming with climate change,” she says. Regardless of whether the change will be fast or slow, Trumbore agrees with the majority of scientists who study the Amazon that it is facing serious challenges that might have global ramifications.

Luciana Gatti climbs a tower that rises above the canopy in the rainforest.

Some of those challenges are directly linked to politics in the region. On 23 August, Gatti and her colleagues reported that assaults on the Amazon — including deforestation, burning and degradation — had increased dramatically in 2019 and 2020 as a result of declines in law enforcement. And that doubled the carbon emissions from the region 10 .

The fate of the Amazon is on Gatti’s mind as she climbs a lattice tower in the Tapajós forest — one of the landmarks her pilots fly over as they collect air samples. The metal structure rattles and creaks as she ascends. On the deck, 15 storeys above the ground, she gazes at the forest spreading in all directions out to the horizon. It looks unblemished. But she says that it is suffering.

“We are killing this ecosystem directly and indirectly,” she says, choking up. She wipes a tear from her eye. “This is what scares me terribly and why it’s affecting me so much when I come here. I’m observing the forest dying.”

Trees in the rainforest pump tremendous amounts of water vapour into the atmosphere through the process of evapotranspiration. Cleared land releases much less moisture, drying out nearby areas of the forest.

Daniel Grossman is a freelance reporter in Watertown, Massachusetts.

Mariana Lenharo contributed translations.

- Author: Daniel Grossman

- Photographer: Dado Galdieri

- Videographer: Patrick Vanier

- Media editor: Amelia Hennighausen

- Subeditor: Anne Haggart

- Art editor: Chris Ryan

- Editor: Richard Monastersky

- Gatti, L. V. et al. Nature 595 , 388–393 (2021).

- Nobre, C. A. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 10759–10768 (2016).

- Lapola, D. M. et al. Science 379 , eabp8622 (2023).

- Griffiths, P., Jakimow, B. & Hostert, P. Remote Sens. Environ. 216 , 497–513 (2018).

- Berenguer, E. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , e2019377118 (2021).

- Brienen, R. J. W. et al. Nature 519 , 344–348 (2015).

- Hubau, W. et al. Nature 579 , 80–87 (2020).

- Norby R. J., Warren, J. M., Iversen, C. M., Medlyn, B. E. & McMurtrie, R. E. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107 , 19368–19373 (2010).

- Salati, E., Dall’Olio, A., Matsui, E. & Gat, J. R. Water Resour. Res. 15 , 1250–1258 (1979).

- Gatti, L. V. et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06390-0 (2023).

Correction: A photo caption in an earlier version of this feature erroneously described a farmer as preparing a field near Santarém for planting. In fact, the field was being harvested.

- Privacy Policy