Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.2 Problem-Solving: Heuristics and Algorithms

Learning objectives.

- Describe the differences between heuristics and algorithms in information processing.

When faced with a problem to solve, should you go with intuition or with more measured, logical reasoning? Obviously, we use both of these approaches. Some of the decisions we make are rapid, emotional, and automatic. Daniel Kahneman (2011) calls this “fast” thinking. By definition, fast thinking saves time. For example, you may quickly decide to buy something because it is on sale; your fast brain has perceived a bargain, and you go for it quickly. On the other hand, “slow” thinking requires more effort; applying this in the same scenario might cause us not to buy the item because we have reasoned that we don’t really need it, that it is still too expensive, and so on. Using slow and fast thinking does not guarantee good decision-making if they are employed at the wrong time. Sometimes it is not clear which is called for, because many decisions have a level of uncertainty built into them. In this section, we will explore some of the applications of these tendencies to think fast or slow.

We will look further into our thought processes, more specifically, into some of the problem-solving strategies that we use. Heuristics are information-processing strategies that are useful in many cases but may lead to errors when misapplied. A heuristic is a principle with broad application, essentially an educated guess about something. We use heuristics all the time, for example, when deciding what groceries to buy from the supermarket, when looking for a library book, when choosing the best route to drive through town to avoid traffic congestion, and so on. Heuristics can be thought of as aids to decision making; they allow us to reach a solution without a lot of cognitive effort or time.

The benefit of heuristics in helping us reach decisions fairly easily is also the potential downfall: the solution provided by the use of heuristics is not necessarily the best one. Let’s consider some of the most frequently applied, and misapplied, heuristics in the table below.

| Heuristic | Description | Examples of Threats to Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Representativeness | A judgment that something that is more representative of its category is more likely to occur | We may overestimate the likelihood that a person belongs to a particular category because they resemble our prototype of that category. |

| Availability | A judgment that what comes easily to mind is common | We may overestimate the crime statistics in our own area because these crimes are so easy to recall. |

| Anchoring and adjustment | A tendency to use a given starting point as the basis for a subsequent judgment | We may be swayed towards or away from decisions based on the starting point, which may be inaccurate. |

In many cases, we base our judgments on information that seems to represent, or match, what we expect will happen, while ignoring other potentially more relevant statistical information. When we do so, we are using the representativeness heuristic . Consider, for instance, the data presented in the table below. Let’s say that you went to a hospital, and you checked the records of the babies that were born on that given day. Which pattern of births do you think you are most likely to find?

| 6:31 a.m. | Girl | 6:31 a.m. | Boy |

| 8:15 a.m. | Girl | 8:15 a.m. | Girl |

| 9:42 a.m. | Girl | 9:42 a.m. | Boy |

| 1:13 p.m. | Girl | 1:13 p.m. | Girl |

| 3:39 p.m. | Boy | 3:39 p.m. | Girl |

| 5:12 p.m. | Boy | 5:12 p.m. | Boy |

| 7:42 p.m. | Boy | 7:42 p.m. | Girl |

| 11:44 p.m. | Boy | 11:44 p.m. | Boy |

| Using the representativeness heuristic may lead us to incorrectly believe that some patterns of observed events are more likely to have occurred than others. In this case, list B seems more random, and thus is judged as more likely to have occurred, but statistically both lists are equally likely. | |||

Most people think that list B is more likely, probably because list B looks more random, and matches — or is “representative of” — our ideas about randomness, but statisticians know that any pattern of four girls and four boys is mathematically equally likely. Whether a boy or girl is born first has no bearing on what sex will be born second; these are independent events, each with a 50:50 chance of being a boy or a girl. The problem is that we have a schema of what randomness should be like, which does not always match what is mathematically the case. Similarly, people who see a flipped coin come up “heads” five times in a row will frequently predict, and perhaps even wager money, that “tails” will be next. This behaviour is known as the gambler’s fallacy . Mathematically, the gambler’s fallacy is an error: the likelihood of any single coin flip being “tails” is always 50%, regardless of how many times it has come up “heads” in the past.

The representativeness heuristic may explain why we judge people on the basis of appearance. Suppose you meet your new next-door neighbour, who drives a loud motorcycle, has many tattoos, wears leather, and has long hair. Later, you try to guess their occupation. What comes to mind most readily? Are they a teacher? Insurance salesman? IT specialist? Librarian? Drug dealer? The representativeness heuristic will lead you to compare your neighbour to the prototypes you have for these occupations and choose the one that they seem to represent the best. Thus, your judgment is affected by how much your neibour seems to resemble each of these groups. Sometimes these judgments are accurate, but they often fail because they do not account for base rates , which is the actual frequency with which these groups exist. In this case, the group with the lowest base rate is probably drug dealer.

Our judgments can also be influenced by how easy it is to retrieve a memory. The tendency to make judgments of the frequency or likelihood that an event occurs on the basis of the ease with which it can be retrieved from memory is known as the availability heuristic (MacLeod & Campbell, 1992; Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). Imagine, for instance, that I asked you to indicate whether there are more words in the English language that begin with the letter “R” or that have the letter “R” as the third letter. You would probably answer this question by trying to think of words that have each of the characteristics, thinking of all the words you know that begin with “R” and all that have “R” in the third position. Because it is much easier to retrieve words by their first letter than by their third, we may incorrectly guess that there are more words that begin with “R,” even though there are in fact more words that have “R” as the third letter.

The availability heuristic may explain why we tend to overestimate the likelihood of crimes or disasters; those that are reported widely in the news are more readily imaginable, and therefore, we tend to overestimate how often they occur. Things that we find easy to imagine, or to remember from watching the news, are estimated to occur frequently. Anything that gets a lot of news coverage is easy to imagine. Availability bias does not just affect our thinking. It can change behaviour. For example, homicides are usually widely reported in the news, leading people to make inaccurate assumptions about the frequency of murder. In Canada, the murder rate has dropped steadily since the 1970s (Statistics Canada, 2018), but this information tends not to be reported, leading people to overestimate the probability of being affected by violent crime. In another example, doctors who recently treated patients suffering from a particular condition were more likely to diagnose the condition in subsequent patients because they overestimated the prevalence of the condition (Poses & Anthony, 1991).

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic is another example of how fast thinking can lead to a decision that might not be optimal. Anchoring and adjustment is easily seen when we are faced with buying something that does not have a fixed price. For example, if you are interested in a used car, and the asking price is $10,000, what price do you think you might offer? Using $10,000 as an anchor, you are likely to adjust your offer from there, and perhaps offer $9000 or $9500. Never mind that $10,000 may not be a reasonable anchoring price. Anchoring and adjustment does not just happen when we’re buying something. It can also be used in any situation that calls for judgment under uncertainty, such as sentencing decisions in criminal cases (Bennett, 2014), and it applies to groups as well as individuals (Rutledge, 1993).

In contrast to heuristics, which can be thought of as problem-solving strategies based on educated guesses, algorithms are problem-solving strategies that use rules. Algorithms are generally a logical set of steps that, if applied correctly, should be accurate. For example, you could make a cake using heuristics — relying on your previous baking experience and guessing at the number and amount of ingredients, baking time, and so on — or using an algorithm. The latter would require a recipe which would provide step-by-step instructions; the recipe is the algorithm. Unless you are an extremely accomplished baker, the algorithm should provide you with a better cake than using heuristics would. While heuristics offer a solution that might be correct, a correctly applied algorithm is guaranteed to provide a correct solution. Of course, not all problems can be solved by algorithms.

As with heuristics, the use of algorithmic processing interacts with behaviour and emotion. Understanding what strategy might provide the best solution requires knowledge and experience. As we will see in the next section, we are prone to a number of cognitive biases that persist despite knowledge and experience.

Key Takeaways

- We use a variety of shortcuts in our information processing, such as the representativeness, availability, and anchoring and adjustment heuristics. These help us to make fast judgments but may lead to errors.

- Algorithms are problem-solving strategies that are based on rules rather than guesses. Algorithms, if applied correctly, are far less likely to result in errors or incorrect solutions than heuristics. Algorithms are based on logic.

Bennett, M. W. (2014). Confronting cognitive ‘anchoring effect’ and ‘blind spot’ biases in federal sentencing: A modest solution for reforming and fundamental flaw. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology , 104 (3), 489-534.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

MacLeod, C., & Campbell, L. (1992). Memory accessibility and probability judgments: An experimental evaluation of the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63 (6), 890–902.

Poses, R. M., & Anthony, M. (1991). Availability, wishful thinking, and physicians’ diagnostic judgments for patients with suspected bacteremia. Medical Decision Making, 11 , 159-68.

Rutledge, R. W. (1993). The effects of group decisions and group-shifts on use of the anchoring and adjustment heuristic. Social Behavior and Personality, 21 (3), 215-226.

Statistics Canada. (2018). Ho micide in Canada, 2017 . Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/181121/dq181121a-eng.pdf

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5 , 207–232.

Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2020 by Sally Walters is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 9. Cognition

Problem-Solving: Heuristics and Algorithms

Dinesh Ramoo

Approximate reading time : 11 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the differences between heuristics and algorithms in information processing

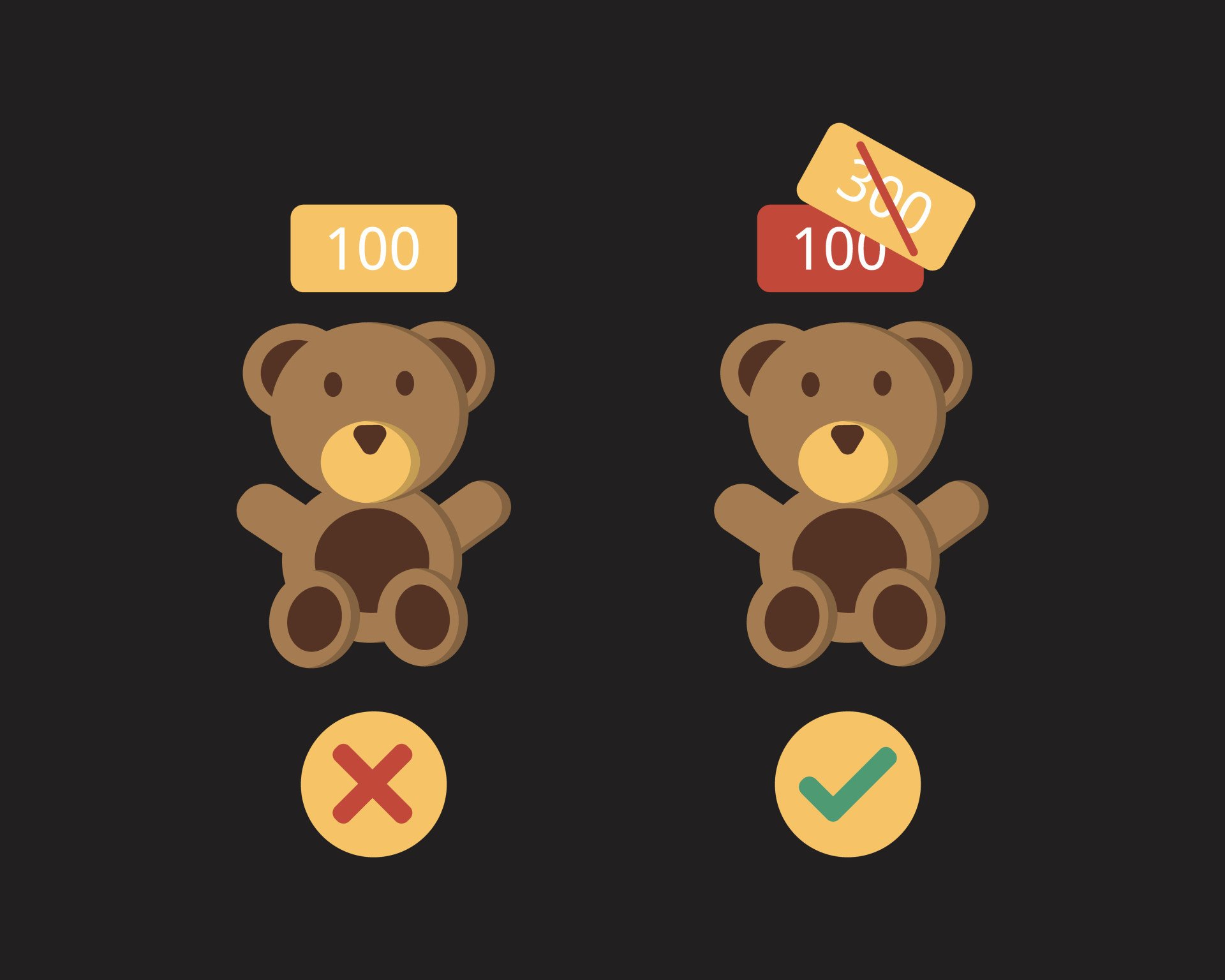

When faced with a problem to solve, should you go with intuition or with more measured, logical reasoning? Obviously, we use both of these approaches. Some of the decisions we make are rapid, emotional, and automatic. Daniel Kahneman (2011) calls this “fast” thinking. By definition, fast thinking saves time. For example, you may quickly decide to buy something because it is on sale; your fast brain has perceived a bargain, and you go for it quickly. On the other hand, “slow” thinking requires more effort; applying this in the same scenario might cause us not to buy the item because we have reasoned that we don’t really need it, that it is still too expensive, and so on. Using slow and fast thinking does not guarantee good decision-making if they are employed at the wrong time. Sometimes it is not clear which is called for, because many decisions have a level of uncertainty built into them. In this section, we will explore some of the applications of these tendencies to think fast or slow.

We will look further into our thought processes, more specifically, into some of the problem-solving strategies that we use. Heuristics are information-processing strategies that are useful in many cases but may lead to errors when misapplied. A heuristic is a principle with broad application, essentially an educated guess about something. We use heuristics all the time, for example, when deciding what groceries to buy from the supermarket, when deciding what to wear before going out, when choosing the best route to drive through town to avoid traffic congestion, and so on. Heuristics can be thought of as aids to decision making; they allow us to reach a solution without a lot of cognitive effort or time.

The benefit of heuristics in helping us reach decisions fairly easily is also the potential downfall: the solution provided by the use of heuristics is not necessarily the best one. Let’s consider some of the most frequently applied, and misapplied, heuristics in Table CO.3 below.

| Heuristic | Description | Examples of Threats to Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Representativeness | A judgment that something that is more representative of its category is more likely to occur | We may overestimate the likelihood that a person belongs to a particular category because they resemble our prototype of that category. |

| Availability | A judgment that what comes easily to mind is common | We may overestimate the crime statistics in our own area because these crimes are so easy to recall. |

| Anchoring and adjustment | A tendency to use a given starting point as the basis for a subsequent judgment | We may be swayed towards or away from decisions based on the starting point, which may be inaccurate. |

In many cases, we base our judgments on information that seems to represent, or match, what we expect will happen, while ignoring other potentially more relevant statistical information. When we do so, we are using the representativeness heuristic . Consider, for instance, the data presented in the lists below. Let’s say that you went to a hospital, and you checked the records of the babies that were born on that given day. Which pattern of births do you think you are most likely to find?

- 6:31 a.m. – Girl

- 8:15 a.m. – Girl

- 9:42 a.m. – Girl

- 1:13 p.m. – Girl

- 3:39 p.m. – Boy

- 5:12 p.m. – Boy

- 7:42 p.m. – Boy

- 11:44 p.m. – Boy

- 6:31 a.m. – Boy

- 9:42 a.m. – Boy

- 3:39 p.m. – Girl

- 7:42 p.m. – Girl

Using the representativeness heuristic may lead us to incorrectly believe that some patterns of observed events are more likely to have occurred than others.

Most people think that list B is more likely, probably because list B looks more random, and matches — or is “representative of” — our ideas about randomness, but statisticians know that any pattern of four girls and four boys is mathematically equally likely. Whether a boy or girl is born first has no bearing on what sex will be born second; these are independent events, each with a 50:50 chance of being a boy or a girl. The problem is that we have a schema of what randomness should be like, which does not always match what is mathematically the case. Similarly, people who see a flipped coin come up “heads”five times in a row will frequently predict, and perhaps even wager money, that “tails” will be next. This behaviour is known as the gambler’s fallacy . Mathematically, the gambler’s fallacy is an error;: the likelihood of any single coin flip being “tails” is always 50%, regardless of how many times it has come up “heads” in the past. Think of how people choose lottery numbers. People who follow the lottery often have the impression that numbers that were chosen before are unlikely to reoccur even though the selection of numbers is random and not dependent on previous events. But the gambler’s fallacy is so strong in most people that they follow this logic all the time.

The representativeness heuristic may explain why we judge people on the basis of appearance. Suppose you meet your new next-door neighbour, who drives a loud motorcycle, has many tattoos, wears leather, and has long hair. Later, you try to guess their occupation. What comes to mind most readily? Are they a teacher? Insurance salesman? IT specialist? Librarian? Drug dealer? The representativeness heuristic will lead you to compare your neighbour to the prototypes you have for these occupations and choose the one that they seem to represent the best. Thus, your judgment is affected by how much your neighbour seems to resemble each of these groups. Sometimes these judgments are accurate, but they often fail because they do not account for base rates , which is the actual frequency with which these groups exist. In this case, the group with the lowest base rate is probably drug dealer.

Our judgments can also be influenced by how easy it is to retrieve a memory. The tendency to make judgments of the frequency or likelihood that an event occurs on the basis of the ease with which it can be retrieved from memory is known as the availability heuristic (MacLeod & Campbell, 1992; Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). Imagine, for instance, that I asked you to indicate whether there are more words in the English language that begin with the letter “R” or that have the letter “R” as the third letter. You would probably answer this question by trying to think of words that have each of the characteristics, thinking of all the words you know that begin with “R” and all that have “R” in the third position. Because it is much easier to retrieve words by their first letter than by their third, we may incorrectly guess that there are more words that begin with “R,” even though there are in fact more words that have “R” as the third letter.

The availability heuristic may explain why we tend to overestimate the likelihood of crimes or disasters; those that are reported widely in the news are more readily imaginable, and therefore, we tend to overestimate how often they occur. Things that we find easy to imagine, or to remember from watching the news, are estimated to occur frequently. Anything that gets a lot of news coverage is easy to imagine. Availability bias does not just affect our thinking. It can change behaviour. For example, homicides are usually widely reported in the news, leading people to make inaccurate assumptions about the frequency of murder. In Canada, the murder rate has dropped steadily since the 1970s (Statistics Canada, 2018), but this information tends not to be reported, leading people to overestimate the probability of being affected by violent crime. In another example, doctors who recently treated patients suffering from a particular condition were more likely to diagnose the condition in subsequent patients because they overestimated the prevalence of the condition (Poses & Anthony, 1991). After the attack on 9/11, more people died from car accidents because more people drove instead of flying in a plane. Even though the attack was an isolated incident and even though flying is statistically safer than driving, the mere fact of seeing the attack on television again and again made people think that flying was more dangerous than it is.

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic is another example of how fast thinking can lead to a decision that might not be optimal. Anchoring and adjustment is easily seen when we are faced with buying something that does not have a fixed price. For example, if you are interested in a used car, and the asking price is $10,000, what price do you think you might offer? Using $10,000 as an anchor, you are likely to adjust your offer from there, and perhaps offer $9000 or $9500. Never mind that $10,000 may not be a reasonable anchoring price. Anchoring and adjustment happens not just when we’re buying something. It can also be used in any situation that calls for judgment under uncertainty, such as sentencing decisions in criminal cases (Bennett, 2014), and it applies to groups as well as individuals (Rutledge, 1993).

In contrast to heuristics, which can be thought of as problem-solving strategies based on educated guesses, algorithms are problem-solving strategies that use rules. Algorithms are generally a logical set of steps that, if applied correctly, should be accurate. For example, you could make a cake using heuristics — relying on your previous baking experience and guessing at the number and amount of ingredients, baking time, and so on — or using an algorithm. The latter would require a recipe which would provide step-by-step instructions; the recipe is the algorithm. Unless you are an extremely accomplished baker, the algorithm should provide you with a better cake than using heuristics would. While heuristics offer a solution that might be correct, a correctly applied algorithm is guaranteed to provide a correct solution. Of course, not all problems can be solved by algorithms.

As with heuristics, the use of algorithmic processing interacts with behaviour and emotion. Understanding what strategy might provide the best solution requires knowledge and experience. As we will see in the next section, we are prone to a number of cognitive biases that persist despite knowledge and experience.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).

Problem-Solving: Heuristics and Algorithms Copyright © 2024 by Dinesh Ramoo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Heuristics: Definition, Examples, And How They Work

Benjamin Frimodig

Science Expert

B.A., History and Science, Harvard University

Ben Frimodig is a 2021 graduate of Harvard College, where he studied the History of Science.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Every day our brains must process and respond to thousands of problems, both large and small, at a moment’s notice. It might even be overwhelming to consider the sheer volume of complex problems we regularly face in need of a quick solution.

While one might wish there was time to methodically and thoughtfully evaluate the fine details of our everyday tasks, the cognitive demands of daily life often make such processing logistically impossible.

Therefore, the brain must develop reliable shortcuts to keep up with the stimulus-rich environments we inhabit. Psychologists refer to these efficient problem-solving techniques as heuristics.

Heuristics can be thought of as general cognitive frameworks humans rely on regularly to reach a solution quickly.

For example, if a student needs to decide what subject she will study at university, her intuition will likely be drawn toward the path that she envisions as most satisfying, practical, and interesting.

She may also think back on her strengths and weaknesses in secondary school or perhaps even write out a pros and cons list to facilitate her choice.

It’s important to note that these heuristics broadly apply to everyday problems, produce sound solutions, and helps simplify otherwise complicated mental tasks. These are the three defining features of a heuristic.

While the concept of heuristics dates back to Ancient Greece (the term is derived from the Greek word for “to discover”), most of the information known today on the subject comes from prominent twentieth-century social scientists.

Herbert Simon’s study of a notion he called “bounded rationality” focused on decision-making under restrictive cognitive conditions, such as limited time and information.

This concept of optimizing an inherently imperfect analysis frames the contemporary study of heuristics and leads many to credit Simon as a foundational figure in the field.

Kahneman’s Theory of Decision Making

The immense contributions of psychologist Daniel Kahneman to our understanding of cognitive problem-solving deserve special attention.

As context for his theory, Kahneman put forward the estimate that an individual makes around 35,000 decisions each day! To reach these resolutions, the mind relies on either “fast” or “slow” thinking.

The fast thinking pathway (system 1) operates mostly unconsciously and aims to reach reliable decisions with as minimal cognitive strain as possible.

While system 1 relies on broad observations and quick evaluative techniques (heuristics!), system 2 (slow thinking) requires conscious, continuous attention to carefully assess the details of a given problem and logically reach a solution.

Given the sheer volume of daily decisions, it’s no surprise that around 98% of problem-solving uses system 1.

Thus, it is crucial that the human mind develops a toolbox of effective, efficient heuristics to support this fast-thinking pathway.

Heuristics vs. Algorithms

Those who’ve studied the psychology of decision-making might notice similarities between heuristics and algorithms. However, remember that these are two distinct modes of cognition.

Heuristics are methods or strategies which often lead to problem solutions but are not guaranteed to succeed.

They can be distinguished from algorithms, which are methods or procedures that will always produce a solution sooner or later.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that can be reliably used to solve a specific problem. While the concept of an algorithm is most commonly used in reference to technology and mathematics, our brains rely on algorithms every day to resolve issues (Kahneman, 2011).

The important thing to remember is that algorithms are a set of mental instructions unique to specific situations, while heuristics are general rules of thumb that can help the mind process and overcome various obstacles.

For example, if you are thoughtfully reading every line of this article, you are using an algorithm.

On the other hand, if you are quickly skimming each section for important information or perhaps focusing only on sections you don’t already understand, you are using a heuristic!

Why Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics usually occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind at the same moment

When studying heuristics, keep in mind both the benefits and unavoidable drawbacks of their application. The ubiquity of these techniques in human society makes such weaknesses especially worthy of evaluation.

More specifically, in expediting decision-making processes, heuristics also predispose us to a number of cognitive biases .

A cognitive bias is an incorrect but pervasive judgment derived from an illogical pattern of cognition. In simple terms, a cognitive bias occurs when one internalizes a subjective perception as a reliable and objective truth.

Heuristics are reliable but imperfect; In the application of broad decision-making “shortcuts” to guide one’s response to specific situations, occasional errors are both inevitable and have the potential to catalyze persistent mistakes.

For example, consider the risks of faulty applications of the representative heuristic discussed above. While the technique encourages one to assign situations into broad categories based on superficial characteristics and one’s past experiences for the sake of cognitive expediency, such thinking is also the basis of stereotypes and discrimination.

In practice, these errors result in the disproportionate favoring of one group and/or the oppression of other groups within a given society.

Indeed, the most impactful research relating to heuristics often centers on the connection between them and systematic discrimination.

The tradeoff between thoughtful rationality and cognitive efficiency encompasses both the benefits and pitfalls of heuristics and represents a foundational concept in psychological research.

When learning about heuristics, keep in mind their relevance to all areas of human interaction. After all, the study of social psychology is intrinsically interdisciplinary.

Many of the most important studies on heuristics relate to flawed decision-making processes in high-stakes fields like law, medicine, and politics.

Researchers often draw on a distinct set of already established heuristics in their analysis. While dozens of unique heuristics have been observed, brief descriptions of those most central to the field are included below:

Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic describes the tendency to make choices based on information that comes to mind readily.

For example, children of divorced parents are more likely to have pessimistic views towards marriage as adults.

Of important note, this heuristic can also involve assigning more importance to more recently learned information, largely due to the easier recall of such information.

Representativeness Heuristic

This technique allows one to quickly assign probabilities to and predict the outcome of new scenarios using psychological prototypes derived from past experiences.

For example, juries are less likely to convict individuals who are well-groomed and wearing formal attire (under the assumption that stylish, well-kempt individuals typically do not commit crimes).

This is one of the most studied heuristics by social psychologists for its relevance to the development of stereotypes.

Scarcity Heuristic

This method of decision-making is predicated on the perception of less abundant, rarer items as inherently more valuable than more abundant items.

We rely on the scarcity heuristic when we must make a fast selection with incomplete information. For example, a student deciding between two universities may be drawn toward the option with the lower acceptance rate, assuming that this exclusivity indicates a more desirable experience.

The concept of scarcity is central to behavioral economists’ study of consumer behavior (a field that evaluates economics through the lens of human psychology).

Trial and Error

This is the most basic and perhaps frequently cited heuristic. Trial and error can be used to solve a problem that possesses a discrete number of possible solutions and involves simply attempting each possible option until the correct solution is identified.

For example, if an individual was putting together a jigsaw puzzle, he or she would try multiple pieces until locating a proper fit.

This technique is commonly taught in introductory psychology courses due to its simple representation of the central purpose of heuristics: the use of reliable problem-solving frameworks to reduce cognitive load.

Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic

Anchoring refers to the tendency to formulate expectations relating to new scenarios relative to an already ingrained piece of information.

Put simply, this anchoring one to form reasonable estimations around uncertainties. For example, if asked to estimate the number of days in a year on Mars, many people would first call to mind the fact the Earth’s year is 365 days (the “anchor”) and adjust accordingly.

This tendency can also help explain the observation that ingrained information often hinders the learning of new information, a concept known as retroactive inhibition.

Familiarity Heuristic

This technique can be used to guide actions in cognitively demanding situations by simply reverting to previous behaviors successfully utilized under similar circumstances.

The familiarity heuristic is most useful in unfamiliar, stressful environments.

For example, a job seeker might recall behavioral standards in other high-stakes situations from her past (perhaps an important presentation at university) to guide her behavior in a job interview.

Many psychologists interpret this technique as a slightly more specific variation of the availability heuristic.

How to Make Better Decisions

Heuristics are ingrained cognitive processes utilized by all humans and can lead to various biases.

Both of these statements are established facts. However, this does not mean that the biases that heuristics produce are unavoidable. As the wide-ranging impacts of such biases on societal institutions have become a popular research topic, psychologists have emphasized techniques for reaching more sound, thoughtful and fair decisions in our daily lives.

Ironically, many of these techniques are themselves heuristics!

To focus on the key details of a given problem, one might create a mental list of explicit goals and values. To clearly identify the impacts of choice, one should imagine its impacts one year in the future and from the perspective of all parties involved.

Most importantly, one must gain a mindful understanding of the problem-solving techniques used by our minds and the common mistakes that result. Mindfulness of these flawed yet persistent pathways allows one to quickly identify and remedy the biases (or otherwise flawed thinking) they tend to create!

Further Information

- Shah, A. K., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2008). Heuristics made easy: an effort-reduction framework. Psychological bulletin, 134(2), 207.

- Marewski, J. N., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 14(1), 77.

- Del Campo, C., Pauser, S., Steiner, E., & Vetschera, R. (2016). Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making. Journal of Business Economics, 86(4), 389-412.

What is a heuristic in psychology?

A heuristic in psychology is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb that simplifies decision-making and problem-solving. Heuristics often speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution, but they can also lead to cognitive biases.

Bobadilla-Suarez, S., & Love, B. C. (2017, May 29). Fast or Frugal, but Not Both: Decision Heuristics Under Time Pressure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition .

Bowes, S. M., Ammirati, R. J., Costello, T. H., Basterfield, C., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Cognitive biases, heuristics, and logical fallacies in clinical practice: A brief field guide for practicing clinicians and supervisors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51 (5), 435–445.

Dietrich, C. (2010). “Decision Making: Factors that Influence Decision Making, Heuristics Used, and Decision Outcomes.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 2(02).

Groenewegen, A. (2021, September 1). Kahneman Fast and slow thinking: System 1 and 2 explained by Sue. SUE Behavioral Design. Retrieved March 26, 2022, from https://suebehaviouraldesign.com/kahneman-fast-slow-thinking/

Kahneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision .

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . Macmillan.

Pratkanis, A. (1989). The cognitive representation of attitudes. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 71–98). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Simon, H.A., 1956. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review .

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185 (4157), 1124–1131.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Thinking and Intelligence

Problem Solving

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When you are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them ( [link] ). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error . The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trial and error | Continue trying different solutions until problem is solved | Restarting phone, turning off WiFi, turning off bluetooth in order to determine why your phone is malfunctioning |

| Algorithm | Step-by-step problem-solving formula | Instruction manual for installing new software on your computer |

| Heuristic | General problem-solving framework | Working backwards; breaking a task into steps |

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

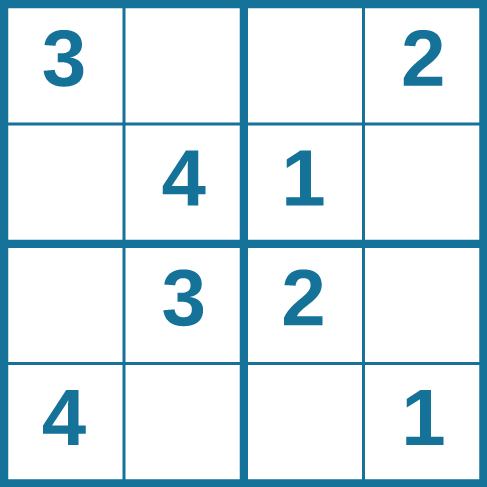

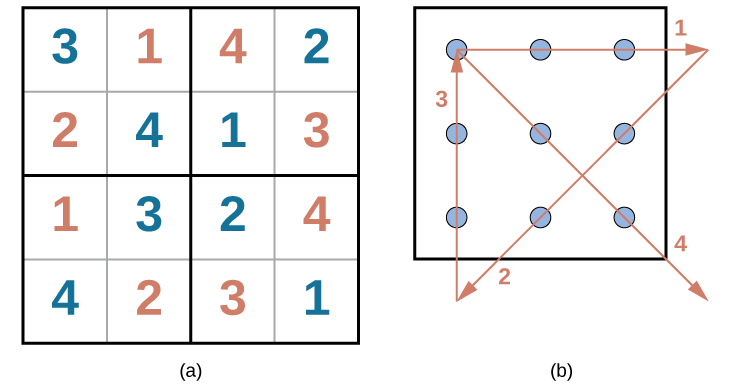

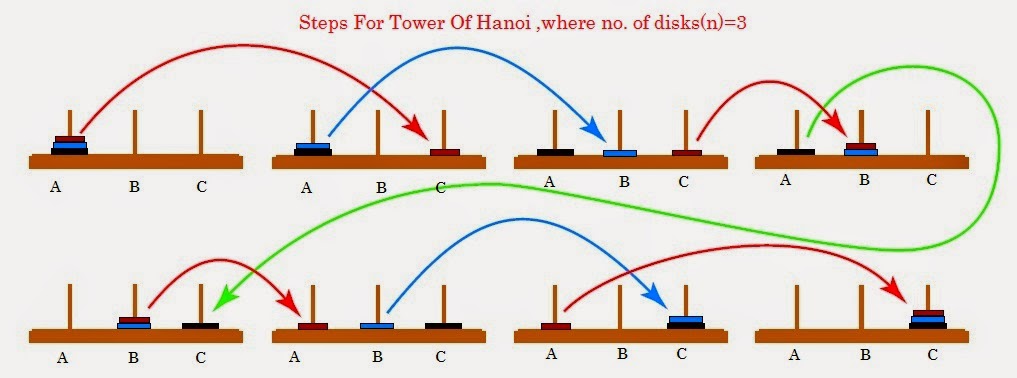

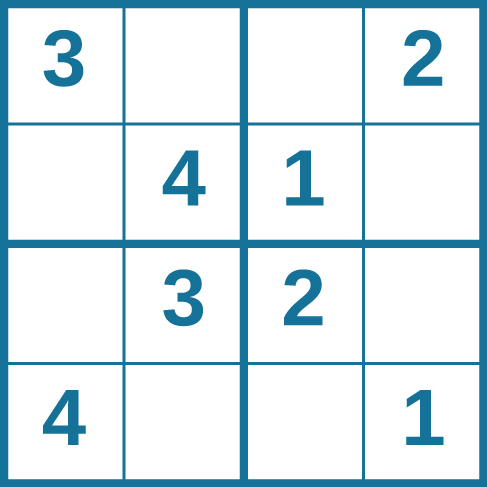

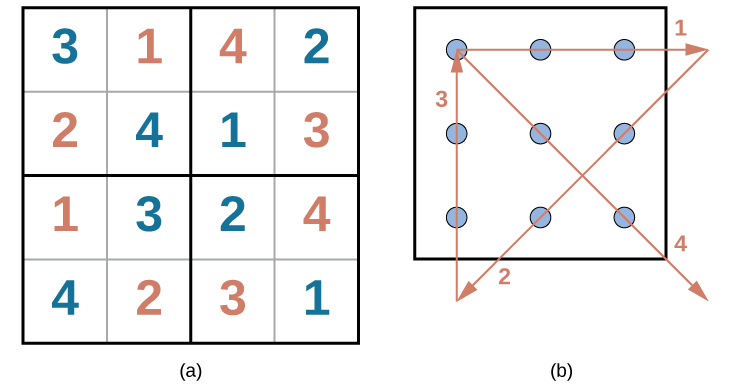

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below ( [link] ) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

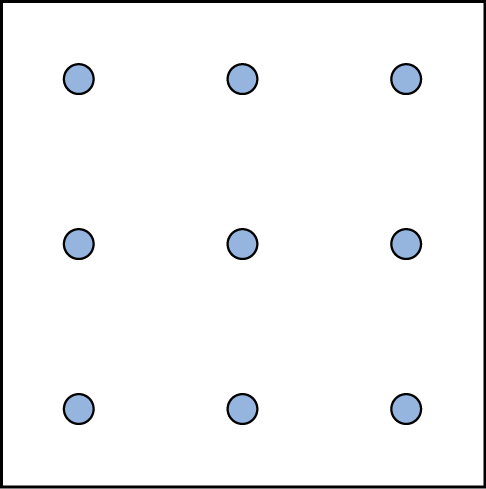

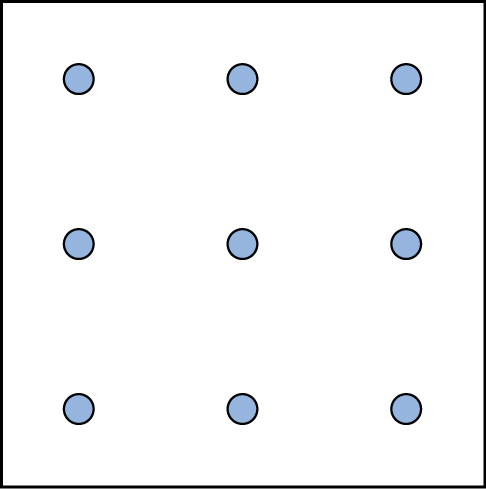

Here is another popular type of puzzle ( [link] ) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

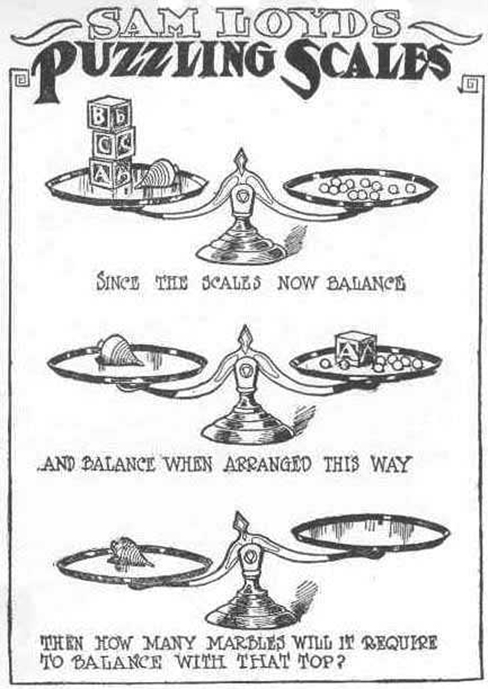

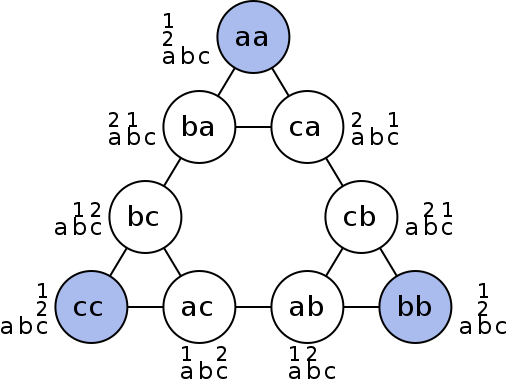

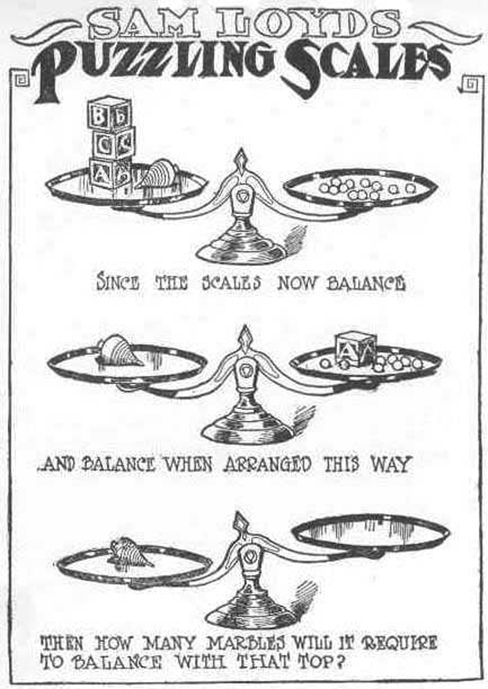

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below ( [link] ). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

PITFALLS TO PROBLEM SOLVING

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Check out this Apollo 13 scene where the group of NASA engineers are given the task of overcoming functional fixedness.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in [link] .

| Bias | Description |

|---|---|

| Anchoring | Tendency to focus on one particular piece of information when making decisions or problem-solving |

| Confirmation | Focuses on information that confirms existing beliefs |

| Hindsight | Belief that the event just experienced was predictable |

| Representative | Unintentional stereotyping of someone or something |

| Availability | Decision is based upon either an available precedent or an example that may be faulty |

Please visit this site to see a clever music video that a high school teacher made to explain these and other cognitive biases to his AP psychology students.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in [link] ? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in [link] and [link] ? Here are the answers ( [link] ).

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

Review Questions

A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

- an algorithm

- a heuristic

- a mental set

- trial and error

A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

- anchoring bias

- confirmation bias

- representative bias

- availability bias

Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

Critical Thinking Questions

What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

Functional fixedness occurs when you cannot see a use for an object other than the use for which it was intended. For example, if you need something to hold up a tarp in the rain, but only have a pitchfork, you must overcome your expectation that a pitchfork can only be used for garden chores before you realize that you could stick it in the ground and drape the tarp on top of it to hold it up.

How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

An algorithm is a proven formula for achieving a desired outcome. It saves time because if you follow it exactly, you will solve the problem without having to figure out how to solve the problem. It is a bit like not reinventing the wheel.

Personal Application Question

Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

Problem Solving Copyright © 2014 by OpenStaxCollege is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

39 8.2 Problem-Solving: Heuristics and Algorithms

Learning objectives.

- Describe the differences between heuristics and algorithms in information processing.

When faced with a problem to solve, should you go with intuition or with more measured, logical reasoning? Obviously, we use both of these approaches. Some of the decisions we make are rapid, emotional, and automatic. Daniel Kahneman (2011) calls this “fast” thinking. By definition, fast thinking saves time. For example, you may quickly decide to buy something because it is on sale; your fast brain has perceived a bargain, and you go for it quickly. On the other hand, “slow” thinking requires more effort; applying this in the same scenario might cause us not to buy the item because we have reasoned that we don’t really need it, that it is still too expensive, and so on. Using slow and fast thinking does not guarantee good decision-making if they are employed at the wrong time. Sometimes it is not clear which is called for, because many decisions have a level of uncertainty built into them. In this section, we will explore some of the applications of these tendencies to think fast or slow.

We will look further into our thought processes, more specifically, into some of the problem-solving strategies that we use. Heuristics are information-processing strategies that are useful in many cases but may lead to errors when misapplied. A heuristic is a principle with broad application, essentially an educated guess about something. We use heuristics all the time, for example, when deciding what groceries to buy from the supermarket, when looking for a library book, when choosing the best route to drive through town to avoid traffic congestion, and so on. Heuristics can be thought of as aids to decision making; they allow us to reach a solution without a lot of cognitive effort or time.

The benefit of heuristics in helping us reach decisions fairly easily is also the potential downfall: the solution provided by the use of heuristics is not necessarily the best one. Let’s consider some of the most frequently applied, and misapplied, heuristics in the table below.

| Heuristic | Description | Examples of Threats to Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Representativeness | A judgment that something that is more representative of its category is more likely to occur | We may overestimate the likelihood that a person belongs to a particular category because they resemble our prototype of that category. |

| Availability | A judgment that what comes easily to mind is common | We may overestimate the crime statistics in our own area because these crimes are so easy to recall. |

| Anchoring and adjustment | A tendency to use a given starting point as the basis for a subsequent judgment | We may be swayed towards or away from decisions based on the starting point, which may be inaccurate. |

In many cases, we base our judgments on information that seems to represent, or match, what we expect will happen, while ignoring other potentially more relevant statistical information. When we do so, we are using the representativeness heuristic . Consider, for instance, the data presented in the table below. Let’s say that you went to a hospital, and you checked the records of the babies that were born on that given day. Which pattern of births do you think you are most likely to find?

| 6:31 a.m. | Girl | 6:31 a.m. | Boy |

| 8:15 a.m. | Girl | 8:15 a.m. | Girl |

| 9:42 a.m. | Girl | 9:42 a.m. | Boy |

| 1:13 p.m. | Girl | 1:13 p.m. | Girl |

| 3:39 p.m. | Boy | 3:39 p.m. | Girl |

| 5:12 p.m. | Boy | 5:12 p.m. | Boy |

| 7:42 p.m. | Boy | 7:42 p.m. | Girl |

| 11:44 p.m. | Boy | 11:44 p.m. | Boy |

| Using the representativeness heuristic may lead us to incorrectly believe that some patterns of observed events are more likely to have occurred than others. In this case, list B seems more random, and thus is judged as more likely to have occurred, but statistically both lists are equally likely. | |||

Most people think that list B is more likely, probably because list B looks more random, and matches — or is “representative of” — our ideas about randomness, but statisticians know that any pattern of four girls and four boys is mathematically equally likely. Whether a boy or girl is born first has no bearing on what sex will be born second; these are independent events, each with a 50:50 chance of being a boy or a girl. The problem is that we have a schema of what randomness should be like, which does not always match what is mathematically the case. Similarly, people who see a flipped coin come up “heads” five times in a row will frequently predict, and perhaps even wager money, that “tails” will be next. This behaviour is known as the gambler’s fallacy . Mathematically, the gambler’s fallacy is an error: the likelihood of any single coin flip being “tails” is always 50%, regardless of how many times it has come up “heads” in the past.

The representativeness heuristic may explain why we judge people on the basis of appearance. Suppose you meet your new next-door neighbour, who drives a loud motorcycle, has many tattoos, wears leather, and has long hair. Later, you try to guess their occupation. What comes to mind most readily? Are they a teacher? Insurance salesman? IT specialist? Librarian? Drug dealer? The representativeness heuristic will lead you to compare your neighbour to the prototypes you have for these occupations and choose the one that they seem to represent the best. Thus, your judgment is affected by how much your neibour seems to resemble each of these groups. Sometimes these judgments are accurate, but they often fail because they do not account for base rates , which is the actual frequency with which these groups exist. In this case, the group with the lowest base rate is probably drug dealer.

Our judgments can also be influenced by how easy it is to retrieve a memory. The tendency to make judgments of the frequency or likelihood that an event occurs on the basis of the ease with which it can be retrieved from memory is known as the availability heuristic (MacLeod & Campbell, 1992; Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). Imagine, for instance, that I asked you to indicate whether there are more words in the English language that begin with the letter “R” or that have the letter “R” as the third letter. You would probably answer this question by trying to think of words that have each of the characteristics, thinking of all the words you know that begin with “R” and all that have “R” in the third position. Because it is much easier to retrieve words by their first letter than by their third, we may incorrectly guess that there are more words that begin with “R,” even though there are in fact more words that have “R” as the third letter.

The availability heuristic may explain why we tend to overestimate the likelihood of crimes or disasters; those that are reported widely in the news are more readily imaginable, and therefore, we tend to overestimate how often they occur. Things that we find easy to imagine, or to remember from watching the news, are estimated to occur frequently. Anything that gets a lot of news coverage is easy to imagine. Availability bias does not just affect our thinking. It can change behaviour. For example, homicides are usually widely reported in the news, leading people to make inaccurate assumptions about the frequency of murder. In Canada, the murder rate has dropped steadily since the 1970s (Statistics Canada, 2018), but this information tends not to be reported, leading people to overestimate the probability of being affected by violent crime. In another example, doctors who recently treated patients suffering from a particular condition were more likely to diagnose the condition in subsequent patients because they overestimated the prevalence of the condition (Poses & Anthony, 1991).

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic is another example of how fast thinking can lead to a decision that might not be optimal. Anchoring and adjustment is easily seen when we are faced with buying something that does not have a fixed price. For example, if you are interested in a used car, and the asking price is $10,000, what price do you think you might offer? Using $10,000 as an anchor, you are likely to adjust your offer from there, and perhaps offer $9000 or $9500. Never mind that $10,000 may not be a reasonable anchoring price. Anchoring and adjustment does not just happen when we’re buying something. It can also be used in any situation that calls for judgment under uncertainty, such as sentencing decisions in criminal cases (Bennett, 2014), and it applies to groups as well as individuals (Rutledge, 1993).

In contrast to heuristics, which can be thought of as problem-solving strategies based on educated guesses, algorithms are problem-solving strategies that use rules. Algorithms are generally a logical set of steps that, if applied correctly, should be accurate. For example, you could make a cake using heuristics — relying on your previous baking experience and guessing at the number and amount of ingredients, baking time, and so on — or using an algorithm. The latter would require a recipe which would provide step-by-step instructions; the recipe is the algorithm. Unless you are an extremely accomplished baker, the algorithm should provide you with a better cake than using heuristics would. While heuristics offer a solution that might be correct, a correctly applied algorithm is guaranteed to provide a correct solution. Of course, not all problems can be solved by algorithms.

As with heuristics, the use of algorithmic processing interacts with behaviour and emotion. Understanding what strategy might provide the best solution requires knowledge and experience. As we will see in the next section, we are prone to a number of cognitive biases that persist despite knowledge and experience.

Key Takeaways

- We use a variety of shortcuts in our information processing, such as the representativeness, availability, and anchoring and adjustment heuristics. These help us to make fast judgments but may lead to errors.

- Algorithms are problem-solving strategies that are based on rules rather than guesses. Algorithms, if applied correctly, are far less likely to result in errors or incorrect solutions than heuristics. Algorithms are based on logic.

Bennett, M. W. (2014). Confronting cognitive ‘anchoring effect’ and ‘blind spot’ biases in federal sentencing: A modest solution for reforming and fundamental flaw. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology , 104 (3), 489-534.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

MacLeod, C., & Campbell, L. (1992). Memory accessibility and probability judgments: An experimental evaluation of the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63 (6), 890–902.

Poses, R. M., & Anthony, M. (1991). Availability, wishful thinking, and physicians’ diagnostic judgments for patients with suspected bacteremia. Medical Decision Making, 11 , 159-68.

Rutledge, R. W. (1993). The effects of group decisions and group-shifts on use of the anchoring and adjustment heuristic. Social Behavior and Personality, 21 (3), 215-226.

Statistics Canada. (2018). Ho micide in Canada, 2017 . Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/181121/dq181121a-eng.pdf

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5 , 207–232.

Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2020 by Sally Walters is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Open Course

Problem Solving: Algorithms vs. Heuristics

In this video I explain the difference between an algorithm and a heuristic and provide an example demonstrating why we tend to use heuristics when solving problems. While algorithms provide step-by-step procedures that can guarantee solutions, heuristics are faster and provide shortcuts for getting to solutions, though this has the potential to cause errors. In the next few videos we’ll see examples of heuristics that we tend to use and the potential decision-making errors that they can cause.

Don’t forget to subscribe to the channel to see future videos! Have questions or topics you’d like to see covered in a future video? Let me know by commenting or sending me an email!

Check out my psychology guide: Master Introductory Psychology, a low-priced alternative to a traditional textbook: http://amzn.to/2eTqm5s

Video Transcript:

Hi, I’m Michael Corayer and this is Psych Exam Review. In this video I want to explain the difference between an algorithm and a heuristic and then provide an example that will hopefully help you to see why it is that we tend to use heuristic.

First, what is an algorithm? Well an algorithm is a step by step procedure for solving a problem. The downside of an algorithm is that it tends to be slow because we have to follow each step. We have to move through the process but on the positive side an algorithm guarantees that we’ll get to the solution. If we can follow all the steps, then we will find the solution to the problem. So an algorithm is guaranteed to work but it’s slow.

What’s a heuristic? Well, a heuristic is sort of a mental shortcut. It’s not a step-by-step procedure and so the downside of a heuristic is, because it’s not a step-by-step procedure it doesn’t guarantee that we’ll actually get to the solution. It might not work so a heuristic is not guaranteed.

We don’t know if it will get us to the correct solution but it’s faster, right? Because it’s a shortcut it skips a lot of the steps and says well these probably aren’t going to get to the solution so I’m just going to skip them. Now it could be the case that those steps would have gotten to the solution or would have gotten to a better solution but the heuristic says I mostly am concerned with getting a quick answer rather than the always correct answer.

Ok, so let’s look at an example of a sort of everyday problem that you might experience and how you would solve it using an algorithm versus using a heuristic. So let’s imagine that I’m in my apartment and I want to go somewhere and so of course I need to take my keys with me and I can’t find them. They’re not on my desk where I usually put them and so I have this problem of how do I find my keys.

Well I know that they’re inside the apartment because I’m inside the apartment and I must have unlocked the door to get in. So one thing that I could do is I could follow an algorithm for solving this problem. I could say okay if the keys are definitely in the apartment somewhere then a step-by-step procedure for finding them will be to start in one corner of the apartment and to slowly look in every single location expanding out from that corner of the apartment until I’ve searched every square inch of the apartment and if I do that it is guaranteed that I will find my keys because they must be in the apartment somewhere.

That approach, that step-by-step procedure will guarantee that I find them but as you can already see it’s going to be slow, right? Because I’m not allowed to skip ahead I have to start in one corner and progress through the entire apartment. Now that’s probably not how you look for your keys if you can’t find them. What do you do instead?

You use a heuristic. You use a shortcut. You say “there’s probably a lot of places that I can just not look in because my keys probably aren’t there.” Now I don’t know that for sure because I don’t know where my keys are but a heuristic that I might use in this approach to solving this problem would be to say “why don’t I look the last place that I remember having them” or maybe I should start by looking in the door, maybe I’ve left them in the door when I unlocked it, right?

Now this doesn’t guarantee that my keys are going to be there but there’s a higher likelihood and it’s going to be faster if I look in the two or three places that my keys are usually found then. I’m probably going to find them. It’s not guaranteed; I might not find my keys in those two or three locations. I might say “okay maybe they’re in the pocket of the pants that I was wearing yesterday or maybe they’re in the door or maybe I set them down on the kitchen table instead of in my bedroom” right?

So what a heuristic does, it says check those places first, take a shortcut. Don’t start looking under the couch, I mean the odds of them being under the couch are probably pretty low. They’re not necessarily zero but they’re low. So start with the places that they might be and then move out from there. Now again, this doesn’t guarantee that I’ll find the keys but it’s going to be a lot faster and maybe I try that and it still doesn’t work. Then maybe eventually I have to resort to my algorithm approach but most of the time we use heuristics.

We have shortcuts that we use that allow us to skip a lot of potentially unnecessary steps. So in the next few videos we’ll look at some other types of heuristics that we use in our decision-making. We’ll also see the situations where they can lead us astray; they can lead us to think that we’ve found the answer when in fact we haven’t or we found an incorrect answer. Ok, I hope you found this helpful, if so, please like the video and subscribe to the channel for more.

Thanks for watching!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

All Subjects

5.7 Introduction to Thinking and Problem Solving

4 min read • june 18, 2024

Sadiyya Holsey

Haseung Jun

So, we just went over memory, but how do we actually think and problem solve? 🤔

Problem Solving

There are two different ways by which you could solve problems:

An algorithm is a step by step method that guarantees to solve a particular problem.

If you lost your phone📱, the algorithm might look like this:

- Remember where you put the phone last. If you don’t, go to the next step. ⤵️

- Retrace your steps. If you can’t, go to the next step.⤵️

- Call your phone to determine the location. Algorithms are process oriented 🔄

A heuristic is also known as a “rule of thumb.” Using heuristic is a quick way to solve a problem 💨, but is usually less effective than using an algorithm (more error prone). Heuristics also involve using trial and error ❌

An example of a heuristic would be trying to find the x value that makes this equal true: 3x+6=24. You might plug in multiple x values until you determine the x value that works.

Heuristics are the opposite of algorithms and are more result oriented. We use our mental set , schemas , prototypes , and concepts automatically when using heuristics.

Tip —When problem solving , think about algorithms as the long way and heuristics as the shortcut.

How would you solve 3x+6=24 using an algorithm?

Instead of using a heuristic and just plugging in answers till you find the right one, you could also solve this problem step by step using an algorithm. The steps may look like this:

- Subtract 6 on both sides: 3x=18

- Divide by 3 on both sides: x=6 You use a mixture of these two when taking a test and overall in everyday life activities🏃🍳.

Trial and Error

Trial and error is when you try to solve a problem multiple times using multiple methods. If you try to solve a problem one time using one method, the next time you solve it, you may use a different method. This process is repeated until a solution is reached.

How do we think?

A mental set is when individuals try to solve a problem the same way all the time because it has worked in the past. However, that doesn’t mean this problem solving method is applicable to the problem at hand or will work for other people. Having a mental set makes it harder to solve problems. Similarly, fixation is the inability to look at a problem with a different perspective.

Intuition is colloquially known as a “gut feeling.” It is sensing something without a direct reason and basically an automatic thought💾

- When problem-solving and making difficult decisions, our brain intuits for us.

- As we learn and grow, our intuition does, too. Our learned associations surface as this gut feeling that we have because of how we know the world works around us 🌎

Insight was discovered by Wolfgang Kohler. It occurs when an individual has an all-of the sudden understanding when solving a problem or learning something. It's that light bulb💡 moment!

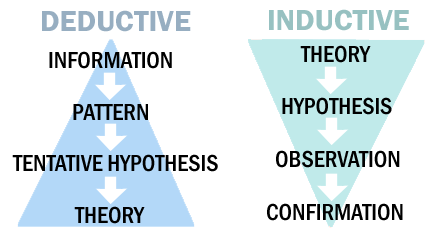

Inductive Reasoning

Reasoning from something specific to something general, which puts your thought into concepts and groups.

Fun Fact —Sherlock Holmes uses inductive reasoning .

Deductive Reasoning

Reasoning from something general to something specific. Think of mind-maps: you have one central idea in the middle (general) and then branch out into specific ideas.

These are usually more logical 🤔

🎨Creativity

Did you ever wonder how we get our creativity and to the extent to which it exists? Being creative is having the ability to produce ideas that are valuable. That's it; we're all creative in our own way.

There are five components of creativity 📸:

- Expertise —The more knowledge we have, the more ideas we build. Knowledge is the foundation of every idea that comes about.1. Generally, greater intelligence leads to a higher creativity 🎭 According to the threshold theory, a certain level of intelligence is necessary for creative work. However, it's not necessary sufficient, meaning other factors play in when it comes to creativity.

- Imaginative thinking skills —In order to be creative, you must be open-minded and see things in different ways. These skills also include being able to make connections and recognize patterns in ideas.

- A venturesome personality —Be willing to take risks, explore ideas, and try new things! 🧗

- Intrinsic Motivation —This is to be driven by your interests and the will to explore for your own satisfaction.

- A creative environment —All the above help fuel your creativity, but creativity can't exist without a supportive environment🌲 There are two different ways of thinking:

📝 Convergent Thinking

This is the more logical way of thinking, in which we narrow the solutions to a problem till we find the best one. Convergent thinking is used in IQ and intelligence tests.

💭 Divergent Thinking

The more creative way of thinking! You can think of this as brainstorming and diverging into different directions of thought. Rather than finding the best solution, divergent thinkers expand the number of solutions.

Divergent thinkers have a much easier time when problem solving since they have more of an open mind to trying different solutions.

Key Terms to Review ( 17 )

© 2024 fiveable inc. all rights reserved., ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website..

Problem-Solving With Algorithm Psychotherapy

Problem-solving plays a crucial role in our daily lives. Regardless of whether it's a personal or professional challenge, we might always seek ways to find solutions to the problems we face. However, in our fast-paced world, relying on intuition and trial and error may not always be feasible.

What is an algorithm? Psychology applications

You likely utilize similar systems when solving problems in your daily life. When confronted with a challenge, our decision-making process is often based on how we’ve solved similar problems in the past. For example, you may have memorized the fastest route to your office, including the most efficient detours. Now, when you’re driving to work, you can use the knowledge gained from past commutes to make decisions on which roads to take when there is traffic or a road closure. This framework for logical reasoning is now a mental shortcut that saves time by helping you avoid thinking about the best decisions to make.

Using algorithmic psychology and problem-solving strategies

What are the potential benefits of this problem-solving approach, increased accuracy, objectivity, efficiency of algorithms.

These advantages could potentially enhance the quality and accuracy of psychological assessments, leading to better diagnoses and treatments.

Algorithms in mental health diagnosis

One of the areas where algorithms are making a significant impact in psychology might be the diagnosis of mental health disorders. Historically, mental health diagnoses have been based on subjective assessments, such as interviews with a clinician or self-reported symptoms. However, these set methods may be prone to error and might not always provide an accurate diagnosis.

Solving problems in mental wellness with algorithms

Challenges with algorithms in psychology.

While the algorithm approach to solving problems can offer several benefits to those in the field of psychology, there are also several challenges that might be addressed to ensure their effective use.

Drawbacks of the algorithmic problem-solving strategy

Discretion concerns, lack of transparency in algorithm psychology, limited generalizability.

This might be a significant challenge in psychology, where there is a need to develop algorithms that could be used across diverse populations to create the best route to solve a problem.

Below are examples of frequently asked questions on algorithms used in psychology to discuss in psychotherapy:

Why is it important to ask questions in psychology?

What are the 3 big questions of psychology?

What is the questionnaire method in psychology?

What is self-questioning in psychology?

Why do philosophers ask questions?

Do liars avoid questions?

What are the first questions that a psychologist asks?

What is a Likert scale in psychology?

What is the survey vs questionnaire method?

What are 4 types of attitude scales?

What is semantic differential in psychology?

What is the 5-point Likert scale in psychology?

What type of survey method is best?

Is the questionnaire a method or technique?

What is the ABC model of attitude?

- Brain Diseases And Mental Health Medically reviewed by Majesty Purvis , LCMHC

- Extinction Psychology Medically reviewed by Arianna Williams , LPC, CCTP

- Psychologists