An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Review of guidelines and literature for handling missing data in longitudinal clinical trials with a case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Clinical Biostatistics, Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ 07065, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 17080924

- DOI: 10.1002/pst.189

Missing data in clinical trials are inevitable. We highlight the ICH guidelines and CPMP points to consider on missing data. Specifically, we outline how we should consider missing data issues when designing, planning and conducting studies to minimize missing data impact. We also go beyond the coverage of the above two documents, provide a more detailed review of the basic concepts of missing data and frequently used terminologies, and examples of the typical missing data mechanism, and discuss technical details and literature for several frequently used statistical methods and associated software. Finally, we provide a case study where the principles outlined in this paper are applied to one clinical program at protocol design, data analysis plan and other stages of a clinical trial.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Handling missing data issues in clinical trials for rheumatic diseases. Wong WK, Boscardin WJ, Postlethwaite AE, Furst DE. Wong WK, et al. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011 Jan;32(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.09.001. Epub 2010 Sep 16. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011. PMID: 20840873 Review.

- Handling missing data in vaccine clinical trials for immunogenicity and safety evaluation. Li X, Wang WW, Liu GF, Chan IS. Li X, et al. J Biopharm Stat. 2011 Mar;21(2):294-310. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2011.550111. J Biopharm Stat. 2011. PMID: 21391003

- Missing data in clinical trials: from clinical assumptions to statistical analysis using pattern mixture models. Ratitch B, O'Kelly M, Tosiello R. Ratitch B, et al. Pharm Stat. 2013 Nov-Dec;12(6):337-47. doi: 10.1002/pst.1549. Epub 2013 Jan 4. Pharm Stat. 2013. PMID: 23292975

- Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Graham JW. Graham JW. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549-76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009. PMID: 18652544 Review.

- Analyzing longitudinal data with missing values. Enders CK. Enders CK. Rehabil Psychol. 2011 Nov;56(4):267-88. doi: 10.1037/a0025579. Epub 2011 Oct 3. Rehabil Psychol. 2011. PMID: 21967118 Review.

- Effectiveness of Early Postpartum Rectus Abdominis versus Transversus Abdominis Training in Patients with Diastasis of the Rectus Abdominis Muscles: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Simpson E, Hahne A. Simpson E, et al. Physiother Can. 2023 Nov 27;75(4):368-376. doi: 10.3138/ptc-2021-0111. eCollection 2023 Nov. Physiother Can. 2023. PMID: 38037580

- Return to Play After Surgical Treatment of High-Grade Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries in the Australian Football League. Borbas P, Warby S, Yalizis M, Smith M, Hoy G. Borbas P, et al. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022 Apr 6;10(4):23259671221085602. doi: 10.1177/23259671221085602. eCollection 2022 Apr. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022. PMID: 35400140 Free PMC article.

- Crohn's disease therapeutic dietary intervention (CD-TDI): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Raman M, Ma C, Taylor LM, Dieleman LA, Gkoutos GV, Vallance JK, McCoy KD, Lewis I, Jijon H, McKay DM, Mutch DM, Barkema HW, Gibson D, Rauch M, Ghosh S. Raman M, et al. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022 Jan;9(1):e000841. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000841. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022. PMID: 35046093 Free PMC article.

- A latent class based imputation method under Bayesian quantile regression framework using asymmetric Laplace distribution for longitudinal medication usage data with intermittent missing values. Lee M, Rahbar MH, Gensler LS, Brown M, Weisman M, Reveille JD. Lee M, et al. J Biopharm Stat. 2020;30(1):160-177. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2019.1684306. Epub 2019 Nov 15. J Biopharm Stat. 2020. PMID: 31730441 Free PMC article.

- Handling Missing Data in the Modeling of Intensive Longitudinal Data. Ji L, Chow SM, Schermerhorn AC, Jacobson NC, Cummings EM. Ji L, et al. Struct Equ Modeling. 2018;25(5):715-736. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2017.1417046. Epub 2018 Feb 8. Struct Equ Modeling. 2018. PMID: 31303745 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Open access

- Published: 06 September 2024

Neurological monitoring and management for adult extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization consensus guidelines

- Sung-Min Cho 1 , 2 ,

- Jaeho Hwang 1 ,

- Giovanni Chiarini 3 , 4 ,

- Marwa Amer 5 , 6 ,

- Marta V. Antonini 7 ,

- Nicholas Barrett 8 ,

- Jan Belohlavek 9 ,

- Daniel Brodie 10 ,

- Heidi J. Dalton 11 ,

- Rodrigo Diaz 12 ,

- Alyaa Elhazmi 5 , 6 ,

- Pouya Tahsili-Fahadan 1 , 13 ,

- Jonathon Fanning 14 ,

- John Fraser 14 ,

- Aparna Hoskote 15 ,

- Jae-Seung Jung 16 ,

- Christopher Lotz 17 ,

- Graeme MacLaren 18 ,

- Giles Peek 19 ,

- Angelo Polito 20 ,

- Jan Pudil 9 ,

- Lakshmi Raman 21 ,

- Kollengode Ramanathan 18 ,

- Dinis Dos Reis Miranda 22 ,

- Daniel Rob 9 ,

- Leonardo Salazar Rojas 23 ,

- Fabio Silvio Taccone 24 ,

- Glenn Whitman 2 ,

- Akram M. Zaaqoq 25 na1 &

- Roberto Lorusso 3 na1

Critical Care volume 28 , Article number: 296 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Critical care of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) with acute brain injury (ABI) is notable for a lack of high-quality clinical evidence. Here, we offer guidelines for neurological care (neurological monitoring and management) of adults during and after ECMO support.

These guidelines are based on clinical practice consensus recommendations and scientific statements. We convened an international multidisciplinary consensus panel including 30 clinician-scientists with expertise in ECMO from all chapters of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). We used a modified Delphi process with three rounds of voting and asked panelists to assess the recommendation levels.

We identified five key clinical areas needing guidance: (1) neurological monitoring, (2) post-cannulation early physiological targets and ABI, (3) neurological therapy including medical and surgical intervention, (4) neurological prognostication, and (5) neurological follow-up and outcomes. The consensus produced 30 statements and recommendations regarding key clinical areas. We identified several knowledge gaps to shape future research efforts.

Conclusions

The impact of ABI on morbidity and mortality in ECMO patients is significant. Particularly, early detection and timely intervention are crucial for improving outcomes. These consensus recommendations and scientific statements serve to guide the neurological monitoring and prevention of ABI, and management strategy of ECMO-associated ABI.

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is increasingly utilized, yet patients receiving ECMO support commonly experience major complications, including acute brain injury (ABI). ABI increases in-hospital mortality by a factor of 2–3 [ 1 , 2 ]. ABI is more common in venoarterial (VA) ECMO than venovenous (VV) ECMO, especially for those with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) with 27–32% of ABI during ECMO support (Table 1 ) despite its survival benefit [ 3 , 4 ]. Although a protocolized neurological monitoring is shown to improve the detection of ABI, this is limited to a few ECMO centers [ 5 ]. The management of ECMO patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) is not standardized, and neurological monitoring and care vary significantly across ECMO centers, thus, the ICU management of patients with ABI during ECMO lacks high-quality evidence and recommendations.

As clinical experience accumulates and ECMO becomes more widely used, clinical guidelines and focused research on neurological monitoring and management of ABI are imperative to enhance ECMO patient care and improve early as well as long-term outcomes. This heterogeneity presents an opportunity to standardize and facilitate neurological care in ECMO [ 5 ].

To establish clinical guidelines on this topic, an international multidisciplinary panel of experts specialized in neurology, critical care, surgery, and other ECMO-related fields was assembled to provide clinical practice consensus recommendations and scientific statements in neurological monitoring and management of adult ECMO patients. These recommendations and statements have been promoted and endorsed by the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). We identified five key clinical areas needing recommendations: (1) neurological monitoring, (2) post-cannulation early physiological targets and their associations with ABI, (3) neurological therapy including medical and surgical intervention, (4) neurological prognostication, and (5) neurological follow-up and outcomes. Here, we present consensus recommendations based on the available evidence and related knowledge gaps warranting further investigations were also identified and summarized (Table 2 ).

Consensus guideline members

ELSO, an international non-profit consortium of healthcare institutions, researchers, and industry partners, developed this consensus statement. ELSO consists of 611 ECMO centers, with chapters in Europe, Asia–Pacific, North America, Latin America, Southwest Asia, and Africa.

An international multidisciplinary consensus panel of 30 experts, including neurologists, intensivists, surgeons, perfusionists, and other professionals in intensive care medicine with expertise or involvement in ECMO, from all ELSO chapters was assembled.

Each of the five-panel subgroups addressed a pre-selected clinical practice domain relevant to patients admitted to the ICU with ABI (ischemic stroke, ICH, or hypoxic-ischemic brain injury). Invited experts contributed to the guidelines through a three-phase process: (1) a literature search/review of neurological monitoring, management, and neurological ECMO outcomes, (2) summarizing the literature search/review, and (3) developing consensus guidelines using a modified Delphi method. The literature search and review performed comprehensively in PubMed on August 29, 2023 yielded up-to-date evidence on neurological monitoring and management strategies. Five key neurological areas needing recommendations were identified (see Introduction).

Guideline development

The selected articles were distributed to each subgroup. The subgroups summarized the findings and developed guidelines and recommendations for each subsection. Each subgroup nominated two leaders for cross-subgroup coordination. The consensus guideline members met regularly throughout the year in subgroup and whole-group settings to discuss their progress and reach a consensus on the finalized document. A modified Delphi process with three rounds of voting to assess the recommendation statements was implemented. Strong recommendation, weak recommendation, or no recommendation was defined when > 85%, 75–85%, and < 75% of panelists, respectively, agreed with a recommendation statement. Three rounds of voting and the authors’ comments about the expert consensus guideline appear in Supplemental Tables 1 – 3 . The guidelines and recommendations were summarized and presented as 5 sections: (1) neurological assessment and monitoring; (2) bedside management; (3) interventional neurology, neurosurgery, and neurocritical care; (4) neurological prognostication; and (5) long-term outcome and quality of life.

Neurological assessment and monitoring

Neurological examination.

Serial bedside examination remains the mainstay of neurological assessment in ECMO patients. However, neurological evaluation, especially early after ECMO cannulation, is frequently confounded by sedatives and paralytics, necessitating noninvasive multimodal neurological monitoring in patients with impaired consciousness. The data on ABI timing to ECMO cannulation/support are limited. Therefore, a baseline neurological assessment is recommended before and immediately after cannulation, followed by serial evaluations throughout ECMO support and after weaning. The ideal frequency of neurological examination is not yet established. Daily assessment by a neurologist/neurointensivist (if available) can improve neurological care. [ 5 , 7 ] More frequent bedside nursing assessment, every 1–4 h based on ABI risk, is reasonable. Particularly, assessing signs of life (such as gasping, pupillary light response, and increased consciousness) is integral to the clinical examination, as these signs observed before, during resuscitation, and while on ECMO support may be associated with improved neurological outcomes [ 8 ]. Historically, the absence of brainstem reflexes with fixed, dilated pupils before cannulation was equated to irreversible ABI and a contraindication to ECMO. However, during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), fixed and dilated pupils are frequently seen after epinephrine administration, and patients have achieved favorable outcomes despite these findings [ 9 ].

Serial neurological examination should include mental status assessment, brainstem reflexes (pupillary light response and oculocephalic, corneal, and cough/gag reflexes), and motor exam. Standardized scoring tools such as the Glasgow Coma Scale and the Confusion Assessment Method should be used. Assessing the motor response of extremities in neurological examinations is only helpful when analgo-sedation and paralytic is lightened or off. Therefore, neurological exam for spinal cord injury, a rare but devastating injury, is very challenging [ 10 ]. Sensory exams are mostly limited in ECMO patients.

Adequate analgo-sedation is essential to ECMO support and minimizes adverse events [ 11 ]. ECMO circuitry and common concomitant impaired liver or kidney function alter medication pharmacokinetics. Standardized sedation protocols with validated scoring systems, such as the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale, are recommended. Overall, intermittent (as-needed) analgo-sedation is preferred over continuous infusion. Short-acting, non-benzodiazepine sedatives could be considered [ 11 ]. Daily reassessment of sedation goals, stepwise sedation weaning, and sedation interruptions can improve neurological exams and ABI diagnosis [ 11 ].

Neurological monitoring

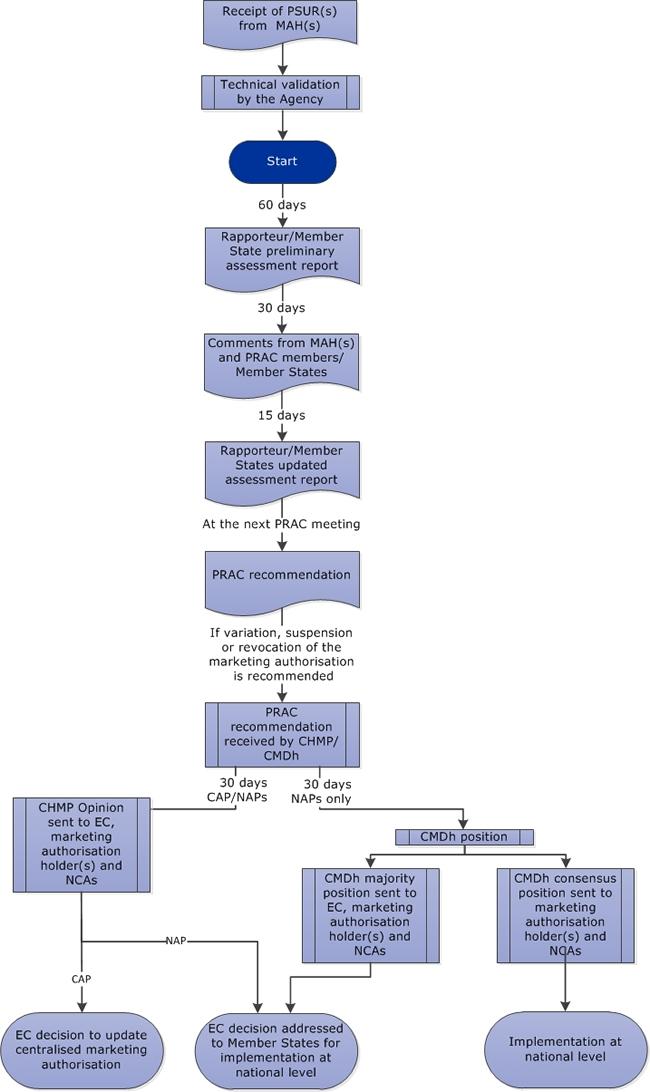

Standardized neurological monitoring, clinical assessment, and a sedation cessation protocol may increase ABI detection and improve neurological outcomes [ 8 , 12 ]. In a single-center study (90% VA ECMO), autopsy shortly after ECMO decannulation showed that 68% of ECMO non-survivors had developed ABI [ 13 ]. In another cohort, 9 of 10 brains exhibited ABI at autopsy [ 14 ], suggesting that ABI incidence is likely higher than clinical detection. Early, accurate ABI detection with standardized neurological monitoring and early interventions is critical for mitigating ABI. Table 3 summarizes current neurological monitoring tools and their evidence (Supplemental Fig. 1 ), and Table 4 provides the consensus recommendations on neurological monitoring (Fig. 1 ). A concise review of sedation, disorders of consciousness and seizure is separately summarized in Supplemental File 1.

Recommendations for neurological monitoring and neuroimaging on ECMO. ABI: acute brain injury; EEG: electroencephalography; rSO 2 : regional oxygen saturation; SSEP: somatosensory evoked potential; VA ECMO: venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Bedside management

Arterial oxygen.

The brain depends on aerobic glucose metabolism for energy, with an average cerebral consumption of 3.5 mL oxygen per 100 g of brain tissue per minute. Hyperoxemia (partial pressure of oxygen (PaO 2 ) > 100 or 120 mmHg: mild; > 300 mmHg: severe) and hypoxemia (PaO 2 < 60 or 70 mmHg) are associated with increased mortality in ICU patients, including subjects on ECMO [ 41 , 42 ].

Limited data exist on early (first 24 h) oxygen targets and neurological outcomes after VV ECMO cannulation. In a single-center observational cohort study, PaO 2 < 70 mmHg (hypoxemia) was associated with ABI, especially ICH [ 43 ]. There are no data on hyperoxemia as it is not often an issue clinically in VV ECMO patients.

In VA ECMO, when the heart recovers before lung recovery, cerebral hypoxemia (especially of the right side of the brain) may occur due to the “differential oxygenation” (also called “Harlequin Syndrome” or “North–South Syndrome”), which is monitored by arterial blood gases from right radial arterial line, especially for those supported with peripheral VA ECMO. Monitoring of cerebral oxygenation using NIRS may be useful in diagnosing differential oxygenation [ 15 ].

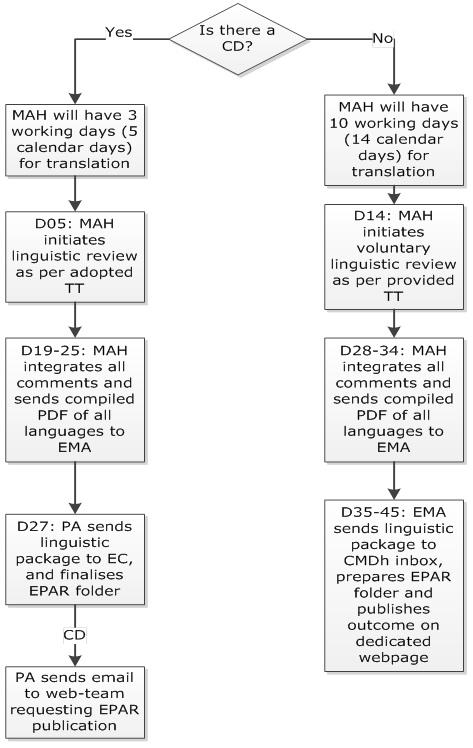

Severe hyperoxemia (PaO 2 > 300 mmHg) within 24 h after the cannulation may be associated with ABI and poor neurologic outcomes [ 4 , 42 , 44 ]. As optimal oxygenation targets are unknown, it is reasonable to avoid early (within 24 h) severe hyperoxemia and hypoxemia by manipulating the fraction of delivered oxygen from the ECMO sweep gas (Fig. 2 ). Given the high-quality data are limited, it is crucial to prospectively study the impact of hyperoxemia on ABI and neurological outcomes in VA ECMO as a multi-institutional study with protocolized neurological monitoring and diagnostic ABI adjudication. Importantly, further research is necessary to investigate the impact of hyperoxemia on each major VA ECMO cohort: postcardiotomy shock, ECPR, and post-acute myocardial infarction (AMI) as well as non-AMI cardiogenic shock.

Recommendations for bedside management on ECMO. ABG: arterial blood gas; BP: blood pressure; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MAP: mean arterial pressure; PaCO 2 : partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO 2 : partial pressure of oxygen; VA: venoarterial; VV: venovenous

Arterial carbon dioxide

Severe acidosis and hypercapnia are common before ECMO cannulation, and both are rapidly corrected upon ECMO initiation by adjusting sweep gas flow across the oxygenator. Carbon dioxide is a potent cerebral vasodilator that increases cerebral blood flow[ 45 ] and neuronal metabolic demand [ 46 ]. Prolonged hypercapnia, common in pre-ECMO patients, may impair cerebral autoregulation, leading to high cerebral blood flow and a narrow regulatory pressure window [ 40 , 47 ]. While high partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO 2 ) should be avoided, rapid correction of sustained high PaCO 2, particularly soon after ECMO initiation, sometimes leads to rapid hypocapnia; it may cause cerebral vasoconstriction and a decrease in cerebral oxygen delivery, resulting in cerebral ischemia [ 46 ]. Routine use of full-dose anticoagulation therapy at ECMO initiation and thereafter may cause hemorrhagic conversion of an ischemic injury.

In an ELSO registry analysis, a rapid early decrease in PaCO 2 was independently associated with an increased risk of ICH in ARDS patients with VV ECMO [ 48 ]. An ELSO retrospective study of 11,972 VV ECMO patients showed that those with ΔPaCO 2 > 50% in the peri-cannulation period were more likely to experience ABI (infarct and ICH) [ 49 ].

A higher ΔPaCO 2 in VA ECMO was associated with ICH in a single-center observational study [ 50 ]. However, an ELSO retrospective study of 3125 ECPR patients showed ΔPaCO 2 higher in ABI than non-ABI, but ΔPaCO 2 was not significantly associated with ABI [ 4 ]. These findings are limited by (a) a lack of sensitive, reliable, and readily available diagnostic markers of ABI, (b) retrospective observations, and (c) inconsistent arterial blood gas sampling. Further research with standardized neurological diagnostic/monitoring tools and granular arterial blood gas data is necessary. However, avoiding a large ΔPaCO 2 > 50% in the peri-cannulation period for both VA and VV ECMO is reasonable.

Temperature

Inducing hypothermia during ischemia prolongs the tolerance of organs to ischemia, improving neurological outcomes [ 51 ]. Thus, it could be reasonable to use hypothermia in VA ECMO patients where cerebral ischemic and hypoperfusion time is prolonged. This rationale is even more important in patients who have already suffered severe hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, as in ECPR. However, as demonstrated by a meta-analysis of 2643 ECPR patients (35 studies), data on this topic are severely heterogeneous and limited to low-quality evidence [ 52 ]. One randomized controlled trial on cardiogenic shock patients requiring VA ECMO compared moderate hypothermia (33–34 °C) versus normothermia (36–37 °C), showing no mortality difference at 30 days [ 53 ]. This study was limited by (1) insufficient sample size due to inaccurate effect size estimation based on non-ECMO studies, (2) lack of formal neurological assessment, and (3) primary outcome being mortality outcome at 30 days instead of neurological outcomes at 90 or 180 days. The basic and preclinical science on hypothermia in ischemia is strong, and VA ECMO patients have a high incidence of ABI and prolonged absent/low cerebral perfusion. Also, bleeding complications and coagulopathy were similar between those with hypothermia vs. without in a meta-analysis of ECPR patients [ 52 ]. A robust multicenter prospective observation cohort study is needed to test the effect of hypothermia strategically in each major VA ECMO cohort. There is no data on hypothermia in VV ECMO patients.

Blood pressure

No data exists on early and optimal blood pressure (BP) goals and ABI prevention, especially for stroke or hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, as the timing of ABI is not well-defined during the peri-cannulation period. After acute ischemic stroke, permissive hypertension (BP ≤ 220/120 mmHg) is recommended by the AHA[ 54 ]; it is reasonable to target mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) that can provide adequate cerebral perfusion in the setting of acute ischemic stroke.

Higher BPs lead to increased afterload, which may hinder myocardial recovery (VA ECMO only), particularly when the left ventricle is not vented. In the absence of high-quality data, allowing patients with acute ischemic stroke to autoregulate is reasonable if the heart can tolerate it. After ICH, lower BP (systolic BP < 140 mmHg and MAP < 90 mmHg) is preferred due to anticoagulation-associated ICH [ 55 ]. Cerebral autoregulation function in the setting of non-pulsatile blood flow and ABI is an active research area, and autoregulatory dysfunction may contribute to ABI in ECMO (Supplemental File 2) [ 56 ].

Low pulse pressure (< 20 mmHg) in the first 24 h of VA ECMO was associated with ABI [ 57 ]. However, data are weak regarding improving pulse pressure with inotropes, or left ventricle venting in ECMO [ 58 ]. Evidence on BP goals for optimal cerebral perfusion in ECMO patients is sparse. Yet, individualized BP management tailored to dynamic cerebral autoregulation function is likely needed in this complex population. However, evidence as well as related therapeutic actions in this regard are still limited and represent mandatory objectives for future research to enhance ECMO patient management and most likely ABI complications prevention and/or reduction. A summary of consensus recommendations and evidence appears in Table 5 and Supplemental Table 4 .

Interventional neurology, neurosurgery, and neurocritical care

ABI diagnosis in ECMO patients is based on comprehensive neurological assessment and brain imaging. Neurological assessment for acute stroke should include the Glasgow Coma Scale and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Non-contrast head CT is imperative to rule out ICH with acute neurological exam change. CT angiogram is needed to assess for large vessel occlusion.

Brain perfusion optimization

Managing intracranial pressure (ICP) and BP contributes to adequate brain perfusion in ABI patients. Elevating the head of the bed by 30 degrees might benefit patients with ABI and elevated ICP [ 61 ]. However, brain oxygenation and circulation improve in the supine position, benefiting perfusion-dependent patients with acute ischemic strokes. The head of the bed could be guided by monitoring surrogate markers of cerebral hemodynamics (i.e., transcranial Doppler ultrasound: cerebral blood flow velocity) and oxygenation (i.e., NIRS: regional saturation) [ 62 , 63 ]. If the heart can tolerate a higher BP, it’s reasonable to target a higher BP target (although individualized BP goal is recommended) to achieve adequate cerebral perfusion pressure, such as permissive hypertension for ischemic stroke. However, increased BP is associated with hematoma extension in ICH, so reducing BP (systolic BP < 140 mmHg) is reasonable, as ECMO patients are usually on full anticoagulation at the time of ICH.

Managing ischemic stroke

Tissue plasminogen activator (tpa).

Non-contrast head CT is imperative to rule out bleeding in acute neurological change, particularly during ECMO. tPA is a time-dependent intervention in acute ischemic stroke. Intravenous tPA in the setting of ECMO carries a high risk of bleeding, especially with systemic anticoagulation and platelet dysfunction. Given these risks, the use of tPA is generally not indicated in ECMO patients. Although there is limited literature specifically addressing this issue, the consensus among experts is to avoid tPA (Fig. 3 ).

Recommendations for interventional neurology, neurosurgery & neurocritical care on ECMO. CT: computed tomography; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICH: intracranial hemorrhage; ICP: intracranial pressure; PbtO 2 : brain tissue oxygenation; tPA: tissue plasminogen activator; VV: venovenous; VA: venoarterial

Mechanical thrombectomy

CT angiogram is needed to rule out large vessel occlusion, typically accompanied by a CT perfusion scan to assess salvageable penumbra. Mechanical thrombectomy should be pursued for patients with large vessel occlusion detected by CT angiogram (accompanied by a CT perfusion scan to assess salvageable penumbra), by consulting stroke specialists, as tPA is generally not recommended in ECMO [ 64 ].

Decompressive craniectomy

Decompressive craniectomy may be indicated in patients with space-occupying lesions with acute intracranial hypertension, such as hemispheric infarction with malignant edema. Hyperosmolar therapy is indicated for cerebral edema [ 1 ]. Systemic anticoagulation monitoring and resumption are necessary post-operatively. Successful craniectomy has been reported for patients on ECMO [ 65 ]. As evidence is limited, the risks versus benefits of such an intervention should be judiciously discussed in a multidisciplinary manner.

Managing ICH

There are two primary considerations in ICH management. First, preventing hematoma expansion by BP control and discontinuing systemic anticoagulation is recommended. The duration of systemic anticoagulation varies based on the mode of ECMO. VV ECMO may allow anticoagulation discontinuation until decannulation based on multiple reports of heparin-free VV ECMO with a heparin-coated circuit [ 66 ]. In contrast, holding systemic anticoagulation carries a higher risk of thromboembolism with VA ECMO, especially the ECMO circuit [ 67 , 68 ]. Early cessation without reversal and judicious resumption of anticoagulation with repeated neuroimaging appeared feasible in the cohort of patients with ECMO-associated ischemic stroke and ICH [ 37 ]. Second, surgical or minimally invasive surgery hematoma evacuation may be considered. There is limited data on neurosurgical interventions in ECMO[ 69 ] for patients with no other management options. Neurosurgery may be considered and utilized. Multidisciplinary discussion should be undertaken, involving neurosurgeons and neurologists in decision-making.

Intracranial pressure monitoring

While external ventricular drainage may be indicated in patients with ICH with intraventricular extension and hydrocephalus, ECMO is associated with coagulopathy and requires systemic anticoagulation. Therefore, external ventricular drain insertion is a high-risk procedure associated with intra- and post-procedural bleeding [ 69 ]. External ventricular drain may be considered in selected patients at risk of imminent death from intraventricular hemorrhage and hydrocephalus. Monitoring ICP or invasive brain tissue oxygenation may be used in patients at high risk of ICP. Invasive ICP and brain tissue oxygenation have not been shown to improve long-term outcomes and may increase the risk of parenchymal hemorrhage in ECMO patients.

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST)

Diagnosis of CVST requires a high index of suspicion in patients with risk factors for thrombosis, including internal jugular vein cannulation. Particularly, large dual-lumen VV ECMO cannulas may be associated with ABI, possibly due to venous hypertension and cannula-related thrombosis [ 70 ]. Clinical diagnosis is challenging because of varying neurological manifestations, including non-specific symptoms such as headache, seizure, or encephalopathy [ 71 ]. The diagnosis is made with brain CT in ECMO. Systemic anticoagulation is the primary treatment; however, in deteriorating patients, endovascular mechanical thrombectomy in advanced centers may be considered [ 72 ]. Lumbar puncture or other spinal fluid drainage and acetazolamide may be considered for patients with increased ICP, along with anti-edema interventions (raising the head of the bed, hyperosmolar therapy, sedation/analgesia, etc.) [ 73 ]. In severe CVST cases with hemispheric cerebral edema, decompressive craniectomy may be considered. A summary of consensus recommendations and evidence is provided in Table 6 and Supplemental Table 5 .

Neurological prognostication

Neurological prognostication is imperative in patients supported by ECPR, in which severe hypoxic-ischemic brain injury may occur as a consequence of refractory cardiac arrest and/or due to inadequate ECMO flow and differential hypoxia. It provides families and caregivers critical information and guides treatment decisions based on the likelihood of a meaningful neurological recovery. As the data on neurological prognostication is limited [ 74 ], a comprehensive approach to prognostication is needed.

Clinical examination plays a pivotal role in prognostication. Practitioners should first rule out potential confounding factors, such as sedatives, significant electrolyte disturbances, and hypothermia, to prevent an overly pessimistic prognosis. Daily clinical/neurological assessments are recommended for patients undergoing targeted temperature management, with the most crucial evaluation conducted after rewarming [ 74 ]. Attention should be given to pupillary and corneal reflexes [ 75 , 76 ]. Clinicians must exercise caution to mitigate the “self-fulfilling prophecy” bias, which occurs when prognostic test results indicating poor outcomes influence treatment decisions [ 77 ].

A comprehensive prognostication strategy should include electrophysiological tests, the evaluation of biomarkers of ABI, and neuroimaging (Table 7 ). Notwithstanding, new modalities are under investigation and will hopefully provide additional clues in such a setting regarding early and enhanced detection of ABI as well as prognostication in ECMO patients [ 78 , 79 ]. An unfavorable neurological outcome in patients without ECMO and cardiac arrest is strongly suggested by at least two indicators of severe ABI. These include the absence of pupillary and corneal reflexes at ≥ 72 h, bilateral lack of N20 cortical waves in somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) at ≥ 24 h, highly malignant EEG patterns at > 24 h, neuron-specific enolase levels exceeding 60 μg/L at 48 h or 72 h, status myoclonus ≤ 72 h, and extensive diffuse anoxic injury observed on brain CT/MRI [ 74 , 80 ]. This approach has not been validated in ECMO patients and has limited evidence [ 30 ].

Neuron-specific enolase values are often higher in ECMO patients due to ongoing hemolysis [ 30 , 85 ]. The most accurate neuron-specific enolase threshold for predicting an unfavorable neurological outcome in ECPR remains unknown, possibly exceeding 100 μg/L. There are sparse data on ECMO patients regarding other biomarkers, such as neurofilament light chain or tau. A combination of clinical, biomarker, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging assessment may effectively predict a neurological outcome within the first week following cardiac arrest [ 81 ]. However, limited data exist for this approach in ECMO patients; further research is needed to validate its utility. A summary of consensus recommendations and evidence is provided in Table 7 .

Other neurological diseases

Neurological prognostication in other ABI (non-hypoxic-ischemic brain injury) with ECMO is challenging and relies on less robust data than cardiac arrest. In the context of stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic), clinical factors impacting outcomes include neurological exam, age, functionality (i.e., modified Rankin Scale), size, and stroke location. For example, age and the location of intracerebral hemorrhage may contribute to neurological prognosis [ 86 ]. However, decisions regarding withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy should be highly individualized with multidisciplinary discussions and considered patient preferences, as data on ECMO patients are sparse.

ICH while the patient is anticoagulated during ECMO carries extremely high mortality and morbidity, as shown in large ELSO registry-based investigations [ 87 , 88 ]. However, these studies did not account for withdrawing life-sustaining therapy in ECMO. Without data, no recommendations for neurological prognostication in ECMO patients can be made.

Brain death on ECMO

A systematic review reported that an apnea test could be included in brain-death criteria in ECMO patients by reducing sweep gas flow or adding exogenous carbon dioxide [ 89 ]. When an apnea test is challenging due to hemodynamic/cardiopulmonary instability, a cerebral angiogram or nuclear scan (radionuclide brain scan) is preferred [ 89 ]. We provide recommendations on apnea tests in ECMO patients (Supplemental Fig. 2 ).

Goals of care discussion

Goals of care and end-of-life discussions are often culturally influenced or determined. Therefore, it is difficult to propose international guidelines for such. No patient-level research guides communicating with families or managing ECMO discontinuation [ 82 ]. Families of ECMO patients experience significant anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder long after hospital discharge [ 83 ]. Frequent family conversations/meetings should focus on informed consent, early goal-setting with timelines and re-evaluation, clear communication, and emotional support with compassion [ 82 ]. Ethics should be discussed openly, including whether to continue or discontinue care and resource allocation issues [ 82 ]. Routine use of ethics consultation within 72 h of cannulation, if the resource is available, can mitigate ethical conflicts by setting clear expectations [ 84 ]. Withdrawal from ECMO should be a structured process involving preparatory family meetings and clinical aspects, including symptom management, technical circuit management, and bereavement support, containing family and staff support.[ 90 ].

Long-term outcome and quality of life

Sparse information exists on long-term outcomes. Long-term MRI found cerebral infarction or hemorrhage in 37–52% of adult ECMO survivors [ 59 , 60 ]. Cognitive impairment and neuroradiologic findings were associated [ 59 , 60 ]. ECMO patients often suffer long-term psychiatric disorders, including organic mental disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorders [ 91 ]. The incidence of neuroradiologic findings was significantly higher in VA ECMO patients than VV ECMO patients [ 59 ]. Given the high frequency, a routine, long-term, structured, standardized follow-up program is recommended for all ECMO centers. Such programs should encompass disease-specific care for underlying and acquired conditions, focusing on neurological and psychiatric disorders. Program design depends on the availability of institutional and international resources. ECMO centers should adapt follow-up programs their specific patient populations and resources while adhering to the recommendations outlined in Table 8 .

Neurological outcomes and quality of life

Assessing ECMO survivors’ quality of life is crucial to understanding the overall impact of ECMO. It is preferable to use internationally recognized, validated tests at standardized intervals. Establishing uniform measures of cognitive function in ECMO patients may clarify outcomes in future studies. Therefore, all patients should have their modified Rankin Scale assessed at discharge and during each follow-up. Additional detailed assessments may be performed based on local practices and patient conditions (e.g., Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended, Montreal Cognitive Assessment). A summary of consensus recommendations and evidence is provided in Table 8 and Supplemental Fig. 3 .

The impact of ABI on morbidity and mortality in ECMO patients is high, and early ABI detection and timely intervention may improve outcomes. Therefore, standardized neurological monitoring and neurological expertise are recommended for ECMO patients. These consensus recommendations and scientific statements serve to guide the neurological monitoring and prevention of ABI, and management strategy of ECMO-associated ABI These recommendations strongly benefit from multidisciplinary care, where it is available, to maximize the chances of favorable long-term outcomes and a good quality of life. Further research on predisposing factors, prevention, neuroimaging and management are ongoing or further required in an attempt to reduce or prevent such dreadful adverse events in ECMO patients.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- Acute brain injury

Acute myocardial infarction

Computed tomography

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Electroencephalogram

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization

Intracranial hemorrhage

Intracranial pressure

Intensive care unit

Magnetic resonance imaging

Near-infrared spectroscopy

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

Partial pressure of oxygen

Regional oxygen saturation

Somatosensory evoked potential

Tissue plasminogen activator

Venoarterial

Cho SM, Farrokh S, Whitman G, Bleck TP, Geocadin RG. Neurocritical care for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(12):1773–81.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lorusso R, Gelsomino S, Parise O, Di Mauro M, Barili F, Geskes G, Vizzardi E, Rycus PT, Muellenbach R, Mueller T, et al. Neurologic injury in adults supported with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure: findings from the extracorporeal life support organization database. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):1389–97.

Ubben JFH, Heuts S, Delnoij TSR, Suverein MM, van de Koolwijk AF, van der Horst ICC, Maessen JG, Bartos J, Kavalkova P, Rob D, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for refractory OHCA: lessons from three randomized controlled trials-the trialists’ view. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2023;12(8):540–7.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shou BL, Ong CS, Premraj L, Brown P, Tonna JE, Dalton HJ, Kim BS, Keller SP, Whitman GJR, Cho SM. Arterial oxygen and carbon dioxide tension and acute brain injury in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation patients: analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023;42(4):503–11.

Ong CS, Etchill E, Dong J, Shou BL, Shelley L, Giuliano K, Al-Kawaz M, Ritzl EK, Geocadin RG, Kim BS, et al. Neuromonitoring detects brain injury in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;165(6):2104–10.

Shoskes A, Migdady I, Rice C, et al. Brain injury is more common in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation than venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):1799–808. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004618 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Cho SM, Ziai W, Mayasi Y, Gusdon AM, Creed J, Sharrock M, Stephens RS, Choi CW, Ritzl EK, Suarez J, et al. Noninvasive neurological monitoring in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2020;66(4):388–93.

Debaty G, Lamhaut L, Aubert R, Nicol M, Sanchez C, Chavanon O, Bouzat P, Durand M, Vanzetto G, Hutin A, et al. Prognostic value of signs of life throughout cardiopulmonary resuscitation for refractory out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2021;162:163–70.

Desai M, Wang J, Zakaria A, Dinescu D, Bogar L, Singh R, Dalton H, Osborn E. Fixed and dilated pupils, not a contraindication for extracorporeal support: a case series. Perfusion. 2020;35(8):814–8.

Le Guennec L, Shor N, Levy B, Lebreton G, Leprince P, Combes A, Dormont D, Luyt CE. Spinal cord infarction during venoarterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. J Artif Organs. 2020;23(4):388–93.

Crow J, Lindsley J, Cho SM, Wang J, Lantry JH 3rd, Kim BS, Tahsili-Fahadan P. Analgosedation in critically Ill adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. ASAIO J. 2022;68(12):1419–27.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cho SM, Ziai W, Geocadin R, Choi CW, Whitman G. Arterial-sided oxygenator clot and TCD emboli in VA-ECMO. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;107(1):326–7.

Cho S-M, Geocadin RG, Caturegli G, Chan V, White B, Dodd-o J, Kim BS, Sussman M, Choi CW, Whitman G, et al. Understanding characteristics of acute brain injury in adult ECMO: an autopsy study. Crit Care Med. 2020;94:1650.

Google Scholar

Mateen FJ, Muralidharan R, Shinohara RT, Parisi JE, Schears GJ, Wijdicks EF. Neurological injury in adults treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(12):1543–9.

Zhao D, Shou BL, Caturegli G, et al. Trends on near-infrared spectroscopy associated with acute brain injury in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2023;69(12):1083–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000002032 .

Pozzebon S, Blandino Ortiz A, Franchi F, et al. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy in adult patients undergoing veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Neurocrit Care. 2018;29(1):94–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-018-0512-1 .

Bertini P, Marabotti A, Paternoster G, et al. Regional cerebral oxygen saturation to predict favorable outcome in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2023;37(7):1265–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2023.01.007 .

Joram N, Beqiri E, Pezzato S, et al. Continuous monitoring of cerebral autoregulation in children supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a pilot study. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34(3):935–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01111-1 .

Tian F, Farhat A, Morriss MC, et al. Cerebral hemodynamic profile in ischemic and hemorrhagic brain injury acquired during pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(10):879–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002438 .

Caturegli G, Zhang LQ, Mayasi Y, et al. Characterization of cerebral hemodynamics with TCD in patients undergoing VA-ECMO and VV-ECMO: a prospective observational study. Neurocrit Care. 2023;38(2):407–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-022-01653-6 .

Kavi T, Esch M, Rinsky B, Rosengart A, Lahiri S, Lyden PD. Transcranial doppler changes in patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(12):2882–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.07.050 .

Caturegli G, Kapoor S, Ponomarev V, et al. Transcranial Doppler microemboli and acute brain injury in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a prospective observational study. JTCVS Tech. 2022;15:111–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjtc.2022.07.026 .

Oddo M, Taccone FS, Petrosino M, et al. The Neurological Pupil index for outcome prognostication in people with acute brain injury (ORANGE): a prospective, observational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(10):925–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00271-5 .

Miroz JP, Ben-Hamouda N, Bernini A, et al. Neurological pupil index for early prognostication after venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Chest. 2020;157(5):1167–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.037 .

Magalhaes E, Reuter J, Wanono R, et al. Early EEG for prognostication under venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Neurocrit Care. 2020;33(3):688–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01066-3 .

Amorim E, Firme MS, Zheng WL, et al. High incidence of epileptiform activity in adults undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2022;140:4–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2022.04.018 .

Sinnah F, Dalloz MA, Magalhaes E, et al. Early electroencephalography findings in cardiogenic shock patients treated by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(5):e389–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003010 .

Peluso L, Rechichi S, Franchi F, et al. Electroencephalographic features in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):629. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03353-z .

Cho SM, Choi CW, Whitman G, et al. Neurophysiological findings and brain injury pattern in patients on ECMO. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2021;52(6):462–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550059419892757 .

Ben-Hamouda N, Ltaief Z, Kirsch M, et al. Neuroprognostication under ecmo after cardiac arrest: Are classical tools still performant? Neurocrit Care. 2022;37(1):293–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-022-01516-0 .

Kim YO, Ko RE, Chung CR, et al. Prognostic value of early intermittent electroencephalography in patients after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1745. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061745 .

Lidegran MK, Mosskin M, Ringertz HG, Frenckner BP, Linden VB. Cranial CT for diagnosis of intracranial complications in adult and pediatric patients during ECMO: clinical benefits in diagnosis and treatment. Acad Radiol. 2007;14(1):62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2006.10.004 .

Cvetkovic M, Chiarini G, Belliato M, et al. International survey of neuromonitoring and neurodevelopmental outcome in children and adults supported on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in Europe. Perfusion. 2023;38(2):245–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/02676591211042563 .

Malfertheiner MV, Koch A, Fisser C, et al. Incidence of early intra-cranial bleeding and ischaemia in adult veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation patients: a retrospective analysis of risk factors. Perfusion. 2020;35:8–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267659120907438 .

Lockie CJA, Gillon SA, Barrett NA, et al. Severe respiratory failure, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and intracranial hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(10):1642–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002579 .

Zotzmann V, Rilinger J, Lang CN, et al. Early full-body computed tomography in patients after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR). Resuscitation. 2020;146:149–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.11.024 .

Prokupets R, Kannapadi N, Chang H, et al. Management of anticoagulation therapy in ECMO-associated ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage. Innovations (Phila). 2023;18(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/15569845221141702 .

Cho SM, Wilcox C, Keller S, et al. Assessing the SAfety and FEasibility of bedside portable low-field brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in patients on ECMO (SAFE-MRI ECMO study): study protocol and first case series experience. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03990-6 .

Lorusso R, Taccone FS, Belliato M, et al. Brain monitoring in adult and pediatric ECMO patients: the importance of early and late assessments. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(10):1061–74. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.17.11911-5 .

Khanduja S, Kim J, Kang JK, et al. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in ecmo: pathophysiology, neuromonitoring, and therapeutic opportunities. Cells. 2023;12(11):1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12111546 .

de Jonge E, Peelen L, Keijzers PJ, Joore H, de Lange D, van der Voort PH, Bosman RJ, de Waal RA, Wesselink R, de Keizer NF. Association between administered oxygen, arterial partial oxygen pressure and mortality in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2008;12(6):R156.

Al-Kawaz MN, Canner J, Caturegli G, Kannapadi N, Balucani C, Shelley L, Kim BS, Choi CW, Geocadin RG, Whitman G, et al. Duration of hyperoxia and neurologic outcomes in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(10):e968–77.

Akbar AF, Shou BL, Feng CY, Zhao DX, Kim BS, Whitman G, Bush EL, Cho SM, Investigators H. Lower oxygen tension and intracranial hemorrhage in veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Lung. 2023;201(3):315–20.

Cho SM, Canner J, Chiarini G, Calligy K, Caturegli G, Rycus P, Barbaro RP, Tonna J, Lorusso R, Kilic A, et al. Modifiable risk factors and mortality from ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in patients receiving venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: results from the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(10):e897–905.

Harper AM, Bell RA. The effect of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis on the blood flow through the cerebral cortex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1963;26(4):341–4.

Dulla CG, Dobelis P, Pearson T, Frenguelli BG, Staley KJ, Masino SA. Adenosine and ATP link PCO2 to cortical excitability via pH. Neuron. 2005;48(6):1011–23.

Meng L, Gelb AW. Regulation of cerebral autoregulation by carbon dioxide. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(1):196–205.

Deng B, Ying J, Mu D. Subtypes and mechanistic advances of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-related acute brain injury. Brain Sci. 2023;13(8):1165.

Cavayas YA, Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Fan E. The early change in Pa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1525–35.

Shou BL, Ong CS, Zhou AL, Al-Kawaz MN, Etchill E, Giuliano K, Dong J, Bush E, Kim BS, Choi CW, et al. Arterial carbon dioxide and acute brain injury in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2022;42(4):503–11.

van der Worp HB, Sena ES, Donnan GA, Howells DW, Macleod MR. Hypothermia in animal models of acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 12):3063–74.

Huang M, Shoskes A, Migdady I, Amin M, Hasan L, Price C, Uchino K, Choi CW, Hernandez AV, Cho SM. Does targeted temperature management improve neurological outcome in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR)? J Intensive Care Med. 2022;37(2):157–67.

Levy B, Girerd N, Amour J, Besnier E, Nesseler N, Helms J, Delmas C, Sonneville R, Guidon C, Rozec B, et al. Effect of moderate hypothermia vs normothermia on 30-day mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock receiving venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(5):442–53.

Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46–110.

Minhas JS, Moullaali TJ, Rinkel GJE, Anderson CS. Blood pressure management after intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage: the knowns and known unknowns. Stroke. 2022;53(4):1065–73.

Kazmi SO, Sivakumar S, Karakitsos D, Alharthy A, Lazaridis C. Cerebral pathophysiology in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: pitfalls in daily clinical management. Crit Care Res Pract. 2018;2018:3237810.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shou BL, Wilcox C, Florissi I, Kalra A, Caturegli G, Zhang LQ, Bush E, Kim B, Keller SP, Whitman GJR, et al. Early low pulse pressure in VA-ECMO is associated with acute brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2023;38(3):612–21.

Lee SI, Lim YS, Park CH, Choi WS, Choi CH. Importance of pulse pressure after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Card Surg. 2021;36(8):2743–50.

Risnes I, Wagner K, Nome T, et al. Cerebral outcome in adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(4):1401–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.10.008 .

von Bahr V, Kalzen H, Hultman J, et al. Long-term cognitive outcome and brain imaging in adults after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(5):e351–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002992 .

Article Google Scholar

Ropper AH, O’Rourke D, Kennedy SK. Head position, intracranial pressure, and compliance. Neurology. 1982;32(11):1288–91.

Blanco P, Abdo-Cuza A. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound in neurocritical care. J Ultrasound. 2018;21(1):1–16.

Miller C, Armonda R. Participants in the International Multi-disciplinary Consensus conference on Multimodality Monitoring of cerebral blood flow and ischemia in the critically ill. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(2):1–26.

Raha O, Hall C, Malik A, D’Anna L, Lobotesis K, Kwan J, Banerjee S. Advances in mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischaemic stroke. BMJ Med. 2023;2(1): e000407.

Friesenecker BE, Peer R, Rieder J, Lirk P, Knotzer H, Hasibeder WR, Mayr AJ, Dunser MW. Craniotomy during ECMO in a severely traumatized patient. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147(9):993–6.

Ryu KM, Chang SW. Heparin-free extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a patient with severe pulmonary contusions and bronchial disruption. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2018;5(3):204–7.

Lamarche Y, Chow B, Bedard A, Johal N, Kaan A, Humphries KH, Cheung A. Thromboembolic events in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation without anticoagulation. Innovations (Phila). 2010;5(6):424–9.

Fina D, Matteucci M, Jiritano F, Meani P, Lo Coco V, Kowalewski M, Maessen J, Guazzi M, Ballotta A, Ranucci M, Lorusso R. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation without therapeutic anticoagulation in adults: a systematic review of the current literature. Int J Artif Organs. 2020;43(9):570–8.

Fletcher-Sandersjoo A, Thelin EP, Bartek J Jr, Elmi-Terander A, Broman M, Bellander BM. Management of intracranial hemorrhage in adult patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): an observational cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12): e0190365.

Mazzeffi M, Kon Z, Menaker J, Johnson DM, Parise O, Gelsomino S, Lorusso R, Herr D. Large dual-lumen extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cannulas are associated with more intracranial hemorrhage. ASAIO J. 2019;65(7):674–7.

Idiculla PS, Gurala D, Palanisamy M, Vijayakumar R, Dhandapani S, Nagarajan E. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a comprehensive review. Eur Neurol. 2020;83(4):369–79.

Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD Jr, Bushnell CD, Cucchiara B, Cushman M, deVeber G, Ferro JM, Tsai FY, Stroke C, American Heart Association, et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1158–92.

Einhaupl K, Stam J, Bousser MG, De Bruijn SF, Ferro JM, Martinelli I, Masuhr F. European federation of neurological S: EFNS guideline on the treatment of cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in adult patients. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(10):1229–35.

Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Bottiger BW, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert VRM, et al. European resuscitation council and european society of intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Resuscitation. 2021;161:220–69.

Nutma S, Ruijter BJ, Beishuizen A, Tromp SC, Scholten E, Horn J, van den Bergh WM, van Kranen-Mastenbroek VH, Thomeer EC, Moudrous W, et al. Myoclonus in comatose patients with electrographic status epilepticus after cardiac arrest: corresponding EEG patterns, effects of treatment and outcomes. Resuscitation. 2023;186: 109745.

Peluso L, Oddo M, Minini A, Citerio G, Horn J, Di Bernardini E, Rundgren M, Cariou A, Payen JF, Storm C, et al. Neurological pupil index and its association with other prognostic tools after cardiac arrest: a post hoc analysis. Resuscitation. 2022;179:259–66.

Elmer J, Kurz MC, Coppler PJ, Steinberg A, DeMasi S, De-Arteaga M, Simon N, Zadorozhny VI, Flickinger KL, Callaway CW, et al. Time to awakening and self-fulfilling prophecies after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(4):503–12.

Cho SM, Khanduja S, Kim J, Kang JK, Briscoe J, Arlinghaus LR, Dinh K, Kim BS, Sair HI, Wandji AN, Moreno E, Torres G, Gavito-Higuera J, Choi HA, Pitts J, Gusdon AM, Whitman GJ. detection of acute brain injury in intensive care unit patients on ECMO support using ultra-low-field portable mri: a retrospective analysis compared to head CT. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(6):606.

Cho SM, Khanduja S, Wilcox C, Dinh K, Kim J, Kang JK, Chinedozi ID, Darby Z, Acton M, Rando H, Briscoe J, Bush E, Sair HI, Pitts J, Arlinghaus LR, Wandji AN, Moreno E, Torres G, Akkanti B, Gavito-Higuera J, Keller S, Choi HA, Kim BS, Gusdon A, Whitman GJ. Clinical use of bedside portable low-field brain magnetic resonance imaging in patients on ECMO: The results from multicenter SAFE MRI ECMO study. Res Sq [Preprint] . 2024

Rajajee V, Muehlschlegel S, Wartenberg KE, Alexander SA, Busl KM, Chou SHY, Creutzfeldt CJ, Fontaine GV, Fried H, Hocker SE, et al. Guidelines for neuroprognostication in comatose adult survivors of cardiac arrest. Neurocrit Care. 2023;38(3):533–63.

Sandroni C, D’Arrigo S, Cacciola S, et al. Prediction of good neurological outcome in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(4):389–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06618-z .

Moynihan KM, Dorste A, Siegel BD, Rabinowitz EJ, McReynolds A, October TW. Decision-making, ethics, and end-of-life care in pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a comprehensive narrative review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2021;22(9):806–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002766 .

Onrust M, Lansink-Hartgring AO, van der Meulen I, Luttik ML, de Jong J, Dieperink W. Coping strategies, anxiety and depressive symptoms in family members of patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a prospective cohort study. Heart Lung Mar. 2022;52:146–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.01.002 .

Wirpsa MJ, Carabini LM, Neely KJ, Kroll C, Wocial LD. Mitigating ethical conflict and moral distress in the care of patients on ECMO: impact of an automatic ethics consultation protocol. J Med Ethics. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106881 .

Petermichl W, Philipp A, Hiller KA, Foltan M, Floerchinger B, Graf B, Lunz D. Reliability of prognostic biomarkers after prehospital extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation with target temperature management. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29(1):147.

Gregorio T, Pipa S, Cavaleiro P, Atanasio G, Albuquerque I, Castro Chaves P, Azevedo L. Original intracerebral hemorrhage score for the prediction of short-term mortality in cerebral hemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(6):857–64.

Cho SM, Canner J, Caturegli G, Choi CW, Etchill E, Giuliano K, Chiarini G, Calligy K, Rycus P, Lorusso R, et al. Risk factors of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of data from the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(1):91–101.

Hwang J, Kalra A, Shou BL, Whitman G, Wilcox C, Brodie D, Zaaqoq AM, Lorusso R, Uchino K, Cho SM. Epidemiology of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):433.

Lie SA, Hwang NC. Challenges of brain death and apnea testing in adult patients on extracorporeal corporeal membrane oxygenation-a review. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33(8):2266–72.

Machado DS, Garros D, Montuno L, Avery LK, Kittelson S, Peek G, Moynihan KM. Finishing well: compassionate extracorporeal membrane oxygenation discontinuation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(5):e553–62.