Holy Roman Empire

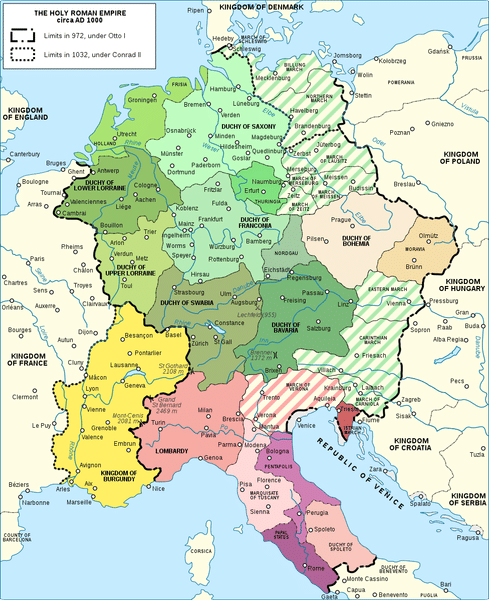

The Holy Roman Empire was a mainly Germanic conglomeration of lands in Central Europe during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. It was also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation from the late fifteenth century onwards. It originated with the partition of the Frankish Empire following the Treaty of Verdun in 843, and lasted until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars . At its peak the Holy Roman Empire encompassed the territories of present-day Germany , Switzerland , Liechtenstein , Luxembourg , Czech Republic , Austria , Slovenia , Belgium , and the Netherlands as well as large parts of modern Poland , France and Italy . At the time of its dissolution it consisted of its core German territories and smaller parts of France, Italy, Poland, Croatia, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The Holy Roman Empire was created in 800 when Charlemagne was crowned by Pope Leo III. Behind this lay the conviction that Christendom should be a single political unit in which religion and governance combined to serve one Lord, Jesus Christ, who is enthroned in heaven above all earthly rulers. The title of Emperor was held by his heirs, the Carolingian Dynasty until the death of Charles the Fat in 887. It passed to the German prince in 962, when Otto I, Duke of Saxony, King of Germany and Italy, was crowned by Pope John XII in return for his guaranteeing the independence of the Papal States. Otto later deposed Pope John in favor of Leo VIII. The actual authority of the Emperor was rarely if ever recognized outside of the territory over which he actually exercised sovereignty, so for example Scandinavia and the British isles remained outside.

- 1 Government

- 2 Nomenclature

- 3.1 King of the Romans

- 3.2 Imperial estates

- 3.3 Reichstag

- 3.4 Imperial courts

- 3.5 Imperial circles

- 4.1 From the East Franks to the Investiture Controversy

- 4.2 Under the Hohenstaufen

- 4.3 Rise of the territories after the Staufen

- 4.4 Imperial reform

- 4.5 Crisis after Reformation

- 4.6 The long decline

- 6 Successive German Empires

- 8 References

- 9 External links

Towards the end of the Empire, the advent of Protestantism as the dominant and often state religion across most of North Europe meant that the even the fiction of a single, unified Christian world was increasingly meaningless. However, at its most powerful, the Empire did represent recognition that temporal power is subject to God's authority and that all power should be wielded morally and with integrity, not for personal gain and self-gratification. The Empire, for much of its history, can be seen as the Christian equivalent of the Muslim caliphate except that the Caliph combined political authority with the spiritual role of being the first amongst equals [1] , while the Emperor was subject to the Pope's authority [2] .

The Reich (empire) was an elective monarchy whose Emperor was crowned by the Pope until 1508. For most of its existence the Empire lacked the central authority of a modern state and was more akin to a loose religious confederation, divided into numerous territories ruled by hereditary nobles, prince-bishops, knightly orders, and free cities. These rulers (later only a select few of them known as Electors) would elect the Emperor from among their number, although there was a strong tendency for the office of Emperor to become hereditary. The House of Habsburg and the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine, for example, furnished an almost continuous line of Emperors from 1452.

The concept of the Reich not only included the government of a specific territory, but had strong Christian religious connotations (hence the holy prefix). The Emperors thought of themselves as continuing the function of the Roman Emperors in defending, governing and supporting the Church. This viewpoint led to much strife between the Empire and the papacy .

Nomenclature

The Holy Roman Empire was a conscious attempt to resurrect the Western Roman Empire, considered to have ended with the abdication of Romulus Augustulus in 476. Although Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Imperator Augustus on December 25, 800, and his son, Louis the Pious was also crowned as Emperor by the Pope, the Empire and the imperial office did not become formalized for some decades, due largely to the Frankish tendency to divide realms between heirs after a ruler's death. It is notable that Louis first crowned himself in 814, upon his father's death, but in 816, Pope Stephen V , who had succeeded Leo III, visited Rheims and again crowned Louis. By that act, the Emperor strengthened the papacy by recognizing the importance of the pope in imperial coronations.

Contemporary terminology for the Empire varied greatly over the centuries. The term Roman Empire was used in 1034 to denote the lands under Conrad II, and Holy Empire in 1157. The use of the term Roman Emperor to refer to Northern European rulers started earlier with Otto II (Emperor 973–983). Emperors from Charlemagne (c. 742 or 747 – 814) to Otto I the Great (Emperor 962–973) had simply used the phrase Imperator Augustus ("August Emperor"). The precise term Holy Roman Empire (German: Heiliges Römisches Reich dates from 1254; the final version Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (German Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation ) appears in 1512, after several variations in the late 15th century. [3]

Contemporaries did not quite know how to describe this entity either. In his famous 1667 description De statu imperii Germanici, published under the alias Severinus de Monzambano, Samuel Pufendorf wrote: "Nihil ergo aliud restat, quam ut dicamus Germaniam esse irregulare aliquod corpus et monstro simile …" ("We are therefore left with calling Germany a body that conforms to no rule and resembles a monster").

In his Essai sur l'histoire generale et sur les moeurs et l'espirit des nations (1756), the French essayist and philosopher Voltaire described the Holy Roman Empire as an "agglomeration" which was "neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire."

In Faust I, in a scene written in 1775, the German author Goethe has one of the drinkers in Auerbach's Cellar in Leipzig ask "Our Holy Roman Empire, lads, what still holds it together?" Goethe also has a longer, not very favourable essay about his personal experiences as a trainee at the Reichskammergericht in his autobiographical work Dichtung und Wahrheit.

Institutions

From the High Middle Ages onwards, the Reich was stamped by a coexistence of the Empire with the struggle of the dukes of the local territories to take power away from it. As opposed to the rulers of the West Frankish lands, which later became France , the Emperors never managed to gain much control over the lands that they formally owned. Instead, Emperors were forced to grant more and more powers to the individual dukes in their respective territories. This process began in the twelfth century and was more or less concluded with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia . Several attempts were made to reverse this degradation of the Reich's former glory, but failed.

Formally, the Reich comprised the King, to be crowned Emperor by the pope (until 1508), on one side, and the Reichsstände (imperial estates) on the other.

King of the Romans

Becoming Emperor required becoming King of the Romans ( Rex romanorum / römischer König ) first. Kings had been elected since time immemorial: in the ninth century by the leaders of the five most important tribes: the Salian Franks of Lorraine, the Riparian Franks of Franconia, and the Saxons, Bavarians, and Swabians, later by the main lay and clerical dukes of the kingdom, finally only by the so-called Kurfürsten (electing dukes, electors). This college was formally established by a 1356 decree known as the Golden Bull. Initially, there were seven electors: the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the King of Bohemia, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, and the Archbishops of Köln, Mainz, and Trier. During the Thirty Years' War , the Duke of Bavaria was given the right to vote as the eighth elector. In order to be elected king, a candidate had to first win over the electors, usually with bribes or promises of land.

Until 1508, the newly-elected king then travelled to Rome to be crowned Emperor by the Pope. In many cases, this took several years while the King was held up by other tasks: frequently he first had to resolve conflicts in rebellious northern Italy or was in quarrel with the Pope himself.

At no time could the Emperor simply issue decrees and govern autonomously over the Empire. His power was severely restricted by the various local leaders: after the late fifteenth century, the Reichstag established itself as the legislative body of the Empire, a complicated assembly that convened irregularly at the request of the Emperor at varying locations. Only after 1663 would the Reichstag become a permanent assembly.

Imperial estates

An entity was considered Reichsstand (imperial estate) if, according to feudal law, it had no authority above it except the Holy Roman Emperor himself. They included:

- Territories governed by a prince or duke, and in some cases kings. (Rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, with the exception of the King of Bohemia (an elector), were not allowed to become King within the Empire, but some had kingdoms outside the Empire, as was, for instance, the case in the Kingdom of Great Britain , where the ruler was also the Prince-elector of Hanover from 1714 until the dissolution of the Empire.)

- Feudal territories led by a clerical dignitary, who was then considered a prince of the church. In the common case of a Prince-Bishop, this temporal territory (called a prince-bishopric) frequently overlapped his—often larger—ecclesiastical diocese (bishopric), giving the bishop both worldly and clerical powers. Examples include the three prince-archbishoprics: Cologne, Trier, and Mainz.

- Imperial Free Cities

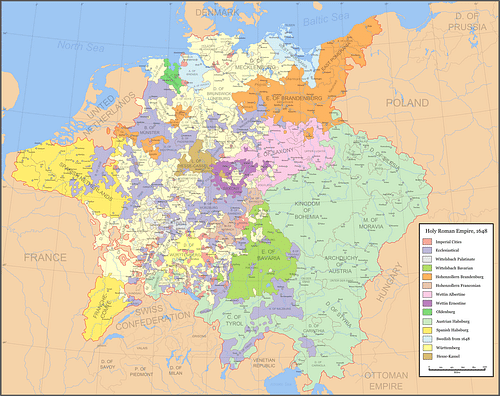

The number of territories was amazingly large, rising to several hundred at the time of the Peace of Westphalia . Many of these comprised no more than a few square miles, so the Empire is aptly described as a "patchwork carpet" (Flickenteppich) by many (see Kleinstaaterei). For a list of Reichsstands in 1792, see List of Reichstag participants (1792).

The Reichstag was the legislative body of the Holy Roman Empire. It was divided into three distinct classes:

- The Council of Electors, which included the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire.

- The Secular Bench: Princes (those with the title of Prince, Grand Duke, Duke, Count Palatine, Margrave, or Landgrave) held individual votes; some held more than one vote on the basis of ruling several territories. Also, the Council included Counts or Grafs, who were grouped into four Colleges: Wetterau, Swabia, Franconia, and Westphalia. Each College could cast one vote as a whole.

- The Ecclesiastical Bench: Bishops, certain Abbots, and the two Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order and the Order of St John had individual votes. Certain other Abbots were grouped into two Colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. Each College held one collective vote.

- The Council of Imperial Cities, which included representatives from Imperial Cities grouped into two Colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. Each College had one collective vote. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal to the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Reichstag had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as in 1648 with the peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War .

Imperial courts

The Reich also had two courts: the Reichshofrat (also known in English as the Aulic Council) at the court of the King/Emperor (that is, later in Vienna ), and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court), established with the Imperial Reform of 1495.

Imperial circles

As part of the Reichsreform, six Imperial Circles were established in 1500 and extended to ten in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not all) of the various states of the Empire for the purposes of defense, imperial taxation, supervising of coining, peace keeping functions and public security. Each circle had its own Kreistag ("Circle Diet").

From the East Franks to the Investiture Controversy

The Holy Roman Empire is usually considered to have been founded at the latest in 962 by Otto I the Great, the first German holder of the title of Emperor.

Although some date the beginning of the Holy Roman Empire from the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans in 800, Charlemagne himself more typically used the title king of the Franks. This title also makes clearer that the Frankish Kingdom covered an area that included modern-day France and Germany and was thus the kernel of both countries.

Most historians therefore consider the establishment of the Empire to be a process that started with the split of the Frankish realm in the Treaty of Verdun in 843, continuing the Carolingian dynasty independently in all three sections. The eastern part fell to Louis the German, who was followed by several leaders until the death of Louis the Child, the last Carolingian in the eastern part.

The leaders of Alamannia, Bavaria, Frankia and Saxonia elected Conrad I of the Franks, not a Carolingian, as their leader in 911. His successor, Henry (Heinrich) I the Fowler (r. 919–936), a Saxon elected at the Reichstag of Fritzlar in 919, achieved the acceptance of a separate Eastern Empire by the West Frankish (still ruled by the Carolingians) in 921, calling himself rex Francorum orientalum (King of the East Franks). He founded the Ottonian dynasty.

Heinrich designated his son Otto to be his successor, who was elected King in Aachen in 936. A marriage alliance with the widowed queen of Italy gave Otto control over that nation as well. His later crowning as Emperor Otto I (later called "the Great") in 962 would mark an important step, since from then on the Empire – and not the West-Frankish kingdom that was the other remainder of the Frankish kingdoms – would have the blessing of the Pope. Otto had gained much of his power earlier, when, in 955, the Magyars were defeated in the Battle of Lechfeld.

In contemporary and later writings, the crowning would be referred to as translatio imperii, the transfer of the Empire from the Romans to a new Empire. The German Emperors thus thought of themselves as being in direct succession of those of the Roman Empire; this is why they initially called themselves Augustus. Still, they did not call themselves "Roman" Emperors at first, probably in order not to provoke conflict with the Roman Emperor who still existed in Constantinople . The term imperator Romanorum only became common under Conrad II later.

At this time, the eastern kingdom was not "German" but a "confederation" of the old Germanic tribes of the Bavarians, Alamanns, Franks and Saxons. The Empire as a political union probably only survived because of the strong personal influence of King Henry the Saxon and his son, Otto. Although formally elected by the leaders of the Germanic tribes, they were actually able to designate their successors.

This changed after Henry II died in 1024 without any children. Conrad II, first of the Salian Dynasty, was then elected king in 1024 only after some debate. How exactly the king was chosen thus seems to be a complicated conglomeration of personal influence, tribal quarrels, inheritance, and acclamation by those leaders that would eventually become the collegiate of Electors.

Already at this time the dualism between the "territories," then those of the old tribes rooted in the Frankish lands, and the King/Emperor, became apparent. Each king preferred to spend most time in his own homelands; the Saxons, for example, spent much time in palatinates around the Harz mountains, among them Goslar. This practice had only changed under Otto III (king 983, Emperor 996–1002), who began to utilize bishopries all over the Empire as temporary seats of government. Also, his successors, Henry II, Conrad II, and Henry III , apparently managed to appoint the dukes of the territories. It is thus no coincidence that at this time, the terminology changes and the first occurrences of a regnum Teutonicum are found.

The glory of the Empire almost collapsed in the Investiture Controversy, in which Pope Gregory VII declared a ban on King Henry IV (king 1056, Emperor 1084–1106). Although this was taken back after the 1077 Walk to Canossa, the ban had wide-reaching consequences. Meanwhile, the German dukes had elected a second king, Rudolf of Swabia, whom Henry IV could only defeat after a three-year war in 1080. The mythical roots of the Empire were permanently damaged; the German king was humiliated. Most importantly though, the church became an independent player in the political system of the Empire.

Under the Hohenstaufen

Conrad III came to the throne in 1138, being the first of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, which was about to restore the glory of the Empire even under the new conditions of the 1122 Concordat of Worms. It was Frederick I "Barbarossa" (king 1152, Emperor 1155–1190) who first called the Empire "holy," with which he intended to address mainly law and legislation.

Also, under Barbarossa, the idea of the "Romanness" of the Empire culminated again, which seemed to be an attempt to justify the Emperor's power independently of the (now strengthened) Pope. An imperial assembly at the fields of Roncaglia in 1158 explicitly reclaimed imperial rights at the advice of quattuor doctores of the emerging judicial facility of the University of Bologna, citing phrases such as princeps legibus solutus ("the emperor [princeps] is not bound by law") from the Digestae of the Corpus Juris Civilis. That the Roman laws were created for an entirely different system and didn't fit the structure of the Empire was obviously secondary; the point here was that the court of the Emperor made an attempt to establish a legal constitution.

Imperial rights had been referred to as regalia since the Investiture Controversy, but were enumerated for the first time at Roncaglia as well. This comprehensive list included public roads, tariffs, coining, collecting punitive fees, and the investiture, the seating and unseating of office holders. These rights were now explicitly rooted in Roman Law, a far-reaching constitutional act; north of the Alps, the system was also now connected to feudal law, a change most visible in the withdrawal of the feuds of Henry the Lion in 1180 which led to his public banning. Barbarossa thus managed for a time to more closely bind the stubborn Germanic dukes to the Empire as a whole.

Another important constitutional move at Roncaglia was the establishment of a new peace (Landfrieden) for all of the Empire, an attempt to (on the one hand) abolish private vendettas not only between the many local dukes, but on the other hand a means to tie the Emperor's subordinates to a legal system of jurisdiction and public prosecution of criminal acts – a predecessor concept of "rule of law," in modern terms, that was, at this time, not yet universally accepted.

In order to solve the problem that the emperor was (after the Investiture Controversy) no longer as able to use the church as a mechanism to maintain power, the Staufer increasingly lent land to ministerialia, formerly unfree service men, which Frederick hoped would be more reliable than local dukes. Initially used mainly for war services, this new class of people would form the basis for the later knights, another basis of imperial power.

Another new concept of the time was the systematic foundation of new cities, both by the emperor and the local dukes. These were partly due to the explosion in population, but also to concentrate economic power at strategic locations, while formerly cities only existed in the shape of either old Roman foundations or older bishoprics. Cities that were founded in the 12th century include Freiburg, possibly the economic model for many later cities, and Munich .

The later reign of the last Staufer Emperor, Frederick II, was in many ways different from that of earlier Emperors. Still a child, he first reigned in Sicily , while in Germany, Barbarossa's second son Philip of Swabia and Henry the Lion's son Otto IV competed with him for the title of "King of the Germans." After finally having been crowned emperor in 1220, he risked conflict with the pope when he claimed power over Rome; astonishingly to many, he managed to claim Jerusalem in a Crusade in 1228 while still under the pope's ban.

While Frederick brought the mythical idea of the Empire to a last highpoint, he was also the one to initiate the major steps that led to its disintegration. On the one hand, he concentrated on establishing an – for the times – extraordinarily modern state in Sicily, with public services, finances, and jurisdiction. On the other hand, Frederick was the emperor who granted major powers to the German dukes in two far-reaching privileges that would never be reclaimed by the central power. In the 1220 Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis, Frederick basically gave up a number of regalia in favor of the bishops, among them tariffs, coining, jurisdiction and fortification. The 1232 Statutum in favorem principum mostly extended these privileges to the other (non-clerical) territories (Frederick II was forced to give those privileges by a rebellion of his son, Henry). Although many of these privileges had existed earlier, they were now granted globally, and once and for all, to allow the German dukes to maintain order north of the Alps while Frederick wanted to concentrate on his homelands in Italy. The 1232 document marked the first time that the German dukes were called domini terrae, owners of their lands, a remarkable change in terminology as well.

The Teutonic Knights were invited to Poland by the duke of Masovia Konrad of Masovia to Christianize the Prussians in 1226.

During the long stays of the Hohenstaufen emperors (1138-1254) in Italy , the German princes became stronger and began a successful, mostly peaceful colonization of West Slavic lands, so that the empire's influence increased to eventually include Pomerania and Silesia .

Rise of the territories after the Staufen

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, none of the dynasties worthy of producing the king proved able to do so, and the leading dukes elected several competing kings. The time from 1246 (beginning with the election of Heinrich Raspe and William of Holland) to 1273, when Rudolph I of Habsburg was elected king, is commonly referred to as the Interregnum. During the Interregnum, much of what was left of imperial authority was lost, as the princes were given time to consolidate their holdings and become even more independent rulers.

In 1257, there occurred a double election which produced a situation that guaranteed a long interregnum. William of Holland had fallen the previous year, and Conrad of Swabia had died three years earlier. First, three electors (Palatinate, Cologne and Mainz) (being mostly of the Guelph persuasion) cast their votes for Richard of Cornwall who became the successor of William of Holland as king. After a delay, a fourth elector, Bohemia , joined this choice. However, a couple of months later, Bohemia and the three other electors Trier, Brandenburg and Saxony voted for Alfonso X of Castile, this being based on Ghibelline party. The realm now had two kings. Was the King of Bohemia entitled to change his vote, or was the election complete when four electors had chosen a king? Were the four electors together entitled to depose Richard a couple of months later, if his election had been valid?

The difficulties in electing the king eventually led to the emergence of a fixed college of electors, the Kurfürsten, whose composition and procedures were set forth in the Golden Bull of 1356. This development probably best symbolizes the emerging duality between Kaiser und Reich , emperor and realm, which were no longer considered identical. This is also revealed in the way the post-Staufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called Reichsgut, which always belonged to the respective king (and included many Imperial Cities). After the thirteenth century, its relevance faded (even though some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806). Instead, the Reichsgut was increasingly pawned to local dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire but, more frequently, to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to civilize stubborn dukes. The direct governance of the Reichsgut no longer matched the needs of either the king or the dukes.

Instead, the kings, beginning with Rudolph I of Habsburg, increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support their power. In contrast with the Reichsgut, which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories were comparably compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolph I thus lent Austria and Styria to his own sons.

With Henry VII, the House of Luxembourg entered the stage. In 1312, he was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (Hausmacht) : Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314, emperor 1328–1347) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from his own lands in Bohemia. Interestingly, it was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

The thirteenth century also saw a general structural change in how land was administered. Instead of personal duties, money increasingly became the common means to represent economic value in agriculture. Peasants were increasingly required to pay tribute for their lands. The concept of "property" more and more replaced more ancient forms of jurisdiction, although they were still very much tied together. In the territories (not at the level of the Empire), power became increasingly bundled: Whoever owned the land had jurisdiction, from which other powers derived. It is important to note, however, that jurisdiction at this time did not include legislation, which virtually did not exist until well into the fifteenth century. Court practice heavily relied on traditional customs or rules described as customary.

It is during this time that the territories began to transform themselves into predecessors of modern states. The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were most identical to the lands of the old Germanic tribes, e.g., Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded through imperial privileges.

Imperial reform

The "constitution" of the Empire was still largely unsettled at the beginning of the 15th century. Although some procedures and institutions had been fixed, for example by the Golden Bull of 1356, the rules of how the king, the electors, and the other dukes should cooperate in the Empire much depended on the personality of the respective king. It therefore proved somewhat fatal that Sigismund of Luxemburg (king 1410, emperor 1433–1437) and Frederick III of Habsburg (king 1440, emperor 1452–1493) neglected the old core lands of the empire and mostly resided in their own lands. Without the presence of the king, the old institution of the Hoftag, the assembly of the realm's leading men, deteriorated. The Reichstag as a legislative organ of the Empire did not exist yet. Even worse, dukes often went into feuds against each other that, more often than not, escalated into local wars.

At the same time, the church was in crisis too. The conflict between several competing popes was only resolved at the Council of Constance (1414–1418); after 1419, much energy was spent on fighting the heresy of the Hussites . The medieval idea of a unified Corpus christianum, of which the papacy and the Empire were the leading institutions, began to decline.

With these drastic changes, much discussion emerged in the 15th century about the Empire itself. Rules from the past no longer adequately described the structure of the time, and a reinforcement of earlier Landfrieden was urgently called for. During this time, the concept of "reform" emerged, in the original sense of the Latin verb re-formare, to regain an earlier shape that had been lost.

When Frederick III needed the dukes to finance war against Hungary in 1486 and at the same time had his son, later Maximilian I elected king, he was presented with the dukes' united demand to participate in an Imperial Court. For the first time, the assembly of the electors and other dukes was now called Reichstag (to be joined by the Imperial Free Cities later). While Frederick refused, his more conciliatory son finally convened the Reichstag at Worms in 1495, after his father's death in 1493. Here, the king and the dukes agreed on four bills, commonly referred to as the Reichsreform (Imperial Reform) : a set of legal acts to give the disintegrating Empire back some structure. Among others, this act produced the Imperial Circle Estates and the Reichskammergericht (Imperial Chamber Court); structures that would — to a degree — persist until the end of the Empire in 1806.

However, it took a few more decades until the new regulation was universally accepted and the new court began to actually function; only in 1512 would the Imperial Circles be finalized. The King also made sure that his own court, the Reichshofrat, continued to function in parallel to the Reichskammergericht. It is interesting to note that in this year, the Empire also received its new title, the Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation ("Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation").

Crisis after Reformation

In 1517, Martin Luther initiated what would later be known as the Reformation . At this time, many local dukes saw a chance to oppose the hegemony of Emperor Charles V. The empire became then fatally divided along religious lines, with the North, the East, and many of the major cities—Strassburg, Frankfurt and Nuremberg—became Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic . Religious conflicts were waged in various parts of Europe for a century, though in German regions there was relative quiet from the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 until the Defenestration of Prague in 1618. When Bohemians rebelled against the emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which devastated the Empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but they also seized considerable chunks of territory for themselves. The long conflict bled the Empire to such a degree that it would never recover its former strength.

The long decline

The actual end of the empire came in several steps. After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which gave the territories almost complete sovereignty , even allowing them to form independent alliances with other states, the Empire was only a mere conglomeration of largely independent states. By the rise of Louis XIV of France , the Holy Roman Empire as such had lost all power and clout in major European politics. The Habsburg emperors relied more on their role as Austrian archdukes than as emperors when challenged by Prussia , portions of which were part of the Empire. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Habsburgs were embroiled in various European conflicts. From 1792 onwards, revolutionary France was at war with various parts of the Empire intermittently. The Empire was formally dissolved on August 6, 1806 when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria ) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French Army under Napoleon Bonaparte . Napoleon reorganized much of the empire into the Confederation of the Rhine. This ended the so-called First Reich. Francis II's family continued to be called Austrian emperors until 1918. In fact, the Habsburg Emperors of Austria, however nostalgically and sentimentally, considered themselves, as the lawful heirs of the Holy Roman monarchs, to be themselves the final continuation of the Holy Roman Imperial line, their dynasty dying out with the ousting of Karl I in 1918 (reigned 1916-1918). Germany itself would not become one unified state until 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War . In addition, at the time of the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following the First World War, it was argued that Liechtenstein as a fief of the Holy Roman Empire (supposedly still incarnated in Liechtensteiner eyes at an abstract level in the person of the then-destitute Austro-Hungarian Emperor, despite its formal dissolution in 1806) was no longer bound to Austria, then emerging as an independent monarchy which did not consider itself as the legal successor to the Empire. Liechtenstein is thus the last independent state in Europe which can claim an element of continuity from the Holy Roman Empire.

It has been said that modern history of Germany was primarily predetermined by three factors: the Reich, the Reformation , and the later dualism between Austria and Prussia. Many attempts have been made to explain why the Reich never managed to gain a strong centralized power over the territories, as opposed to neighboring France. Some reasons include:

- The Reich had been a very federal body from the beginning: again, as opposed to France, which had mostly been part of the Roman Empire, in the eastern parts of the Frankish kingdom, the Germanic tribes later comprising the German nation (Saxons, Thuringians, Franks, Bavarians, Alamanni or Swabians) were much more independent and reluctant to cede power to a central authority. All attempts to make the kingdom hereditary failed; instead, the king was always elected. Later, every candidate for the king had to make promises to his electorate, the so-called Wahlkapitulationen (election capitulations), thus granting the territories more and more power over the centuries.

- Due to its religious connotations, the Reich as an institution was severely damaged by the contest between the Pope and the German Kings over their respective coronations as Emperor. It was never entirely clear under which conditions the pope would crown the emperor and especially whether the worldly power of the emperor was dependent on the clerical power of the pope. Much debate occurred over this, especially during the eleventh century, eventually leading to the Investiture Controversy and the Concordat of Worms in 1122.

- Whether the feudal system of the Reich, where the King formally was the top of the so-called "feudal pyramid," was a cause of or a symptom of the Empire's weakness is unclear. In any case, military obedience, which – according to Germanic tradition – was closely tied to the giving of land to tributaries, was always a problem: when the Reich had to go to war, decisions were slow and brittle.

- Until the sixteenth century, the economic interests of the south and west diverged from those of the north where the Hanseatic League operated. The Hanseatic League was far more closely allied to Scandinavia and the Baltic than the rest of Germany.

- German historiography nowadays often views the Holy Roman Empire as a well balanced system of organizing a multitude of (effectively independent) states under a complex system of legal regulations. Smaller estates like the Lordships or the Imperial Free cities survived for centuries as independent entities, although they had no effective military strength. The supreme courts, the Reichshofrat and the Reichskammergericht helped to settle conflicts, or at least keep them as wars of words rather than shooting wars.

- The multitude of different territories with different religious denominations and different forms of government led to a great variety of cultural diversification, which can be felt even in present day Germany with regional cultures, patterns of behavior and dialects changing sometimes within the range of kilometres.

Successive German Empires

After the unification of Germany as a nation state in 1871, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation was also known as the Old Empire (First Reich) while the new empire was known as the New Empire, second Empire, or Second Reich. Adolf Hitler called his regime the Third Reich .

- ↑ thus, the spiritual and the temporal were equal and symbolically the Caliph represented both

- ↑ The Pope claimed to be temporal and spiritual leader, delegating temporal leadership to the Emperor, spiritual to the Bishops as Lords-spiritual

- ↑ The term for the Empire, in other languages that historically were spoken within its confines are: Czech: Svatá říše římská, later Svatá říše římská národa německého ; Dutch: Heilige Roomse Rijk, later Heilige Roomse Rijk der Duitse Naties/Volkeren ; French: Saint Empire Romain Germanique ; Italian: Sacro Romano Impero ; Slovene: Sveto rimsko cesarstvo, later Sveto rimsko cesarstvo nemške narodnosti.

References ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Angermeier, Heninz. Das Alte Reich in der deutschen Geschichte. Studien über Kontinuitäten und Zäsuren, München: Campus 1991 ISBN 9783593371009

- Bryce, James. The Holy Roman Empire New York, Schocken Books, 1967 ISBN 0333036093

- Criswell, David. The Rise of the Holy Roman Empire. Charleston, SC: Fortress/Adonai Press, 2003 ISBN 9781591097303

- Hartmann, Peter Claus. Kulturgeschichte des Heiligen Römischen Reiches 1648 bis 1806. Wien: Böhlau, 2001 ISBN 9783205993087

- Heer, Friedrich. The Holy Roman Empire. New Haven, CT: Phoenix Press, 2002 ISBN 978-1842126004

- Schmidt, Georg. Geschichte des Alten Reiches. München: C.H. Beck, 1999 ISBN 9783406453359

- von Aretin, Karl Otmar Freiherr. Das Alte Reich 1648-1806. 4 vols. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1993-2000. ISBN 9783608941746

- Zophy, Jonathan W. (ed.), The Holy Roman Empire: A Dictionary Handbook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980. ISBN 9780313214578

External links

All links retrieved July 18, 2024.

- The Holy Roman Empire in 1648

- The Holy Roman Empire in 1789 (Interactive map)

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards . This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Holy Roman Empire history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia :

- History of "Holy Roman Empire"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- Pages using ISBN magic links

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The holy roman empire and the habsburgs, 1400–1600.

Margaret of Austria

Jean Hey (called Master of Moulins)

Saint Maurice

Lucas Cranach the Elder and Workshop

Mars and Venus United by Love

Paolo Veronese (Paolo Caliari)

Lukas Spielhausen

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Friedrich III (1463–1525), the Wise, Elector of Saxony

Armor of Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–1564)

Kunz Lochner

Johann I (1468–1532), the Constant, Elector of Saxony

Johann (1498–1537), Duke of Saxony

Double-Barreled Wheellock Pistol Made for Emperor Charles V (reigned 1519–56)

Daniel, Archbishop of Mainz

- Master HKVB

Maximillian II, Holy Roman Emperor (1527–1576)

Medalist: Antonio Abondio

Celestial globe with clockwork

Gerhard Emmoser

Diana and Actaeon

Bartholomeus Spranger

Adriaen de Vries

The Harvesters

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Portrait of Rudolph II

Aegidius Sadeler II

Jennifer Meagher Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Background on the Empire On Christmas day in the year 800—more than three centuries after the abdication of the last Roman emperor—Charlemagne, the Carolingian king of the Franks, was crowned Emperor of the West by Pope Leo III. This act was seen as a revival, or transference, of the Roman empire ( translatio imperii ), prophesied to be the last of four earthly kingdoms preceding the Apocalypse. The imperial title, which asserted symbolic authority over all Christendom but had little concrete political significance, was passed to Charlemagne’s Carolingian successors. It was, however, the German emperor Otto I (r. 962–73) who, by military conquest and astute political policy, placed the territorial empire of Charlemagne under German rule and established in Central Europe the feudal state that would be called, by the thirteenth century, the Holy Roman Empire. From the time of Otto’s coronation until the official dissolution of the empire in 1806, the imperial title was held almost exclusively by German monarchs and, for nearly four centuries, by members of a single family.

Although most German kings attained imperial coronation, there were often several candidates for the throne. A body of princes, called electors, selected by majority vote both the German king and emperor; the crown, however, was only officially conferred by the pope, who occasionally claimed ultimate authority in the election. Over time, tensions mounted between the emperors and electors who, as one of the three representative groups in the Imperial Diet (or parliamentary body), kept the power of the monarch in check. The culmination of these tensions came with the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century: while the emperors adhered to Roman Catholicism, the electors generally supported the Reformation. It was, in fact, an elector—Frederick III (the Wise) of Saxony—who gave refuge to Martin Luther upon his excommunication.

The Habsburg Emperors Rudolf I (died 1291), the King of the Germans, came from a noble family of Swiss origin and rose to power in 1273. His defeat of King Otakar II of Bohemia (r. 1253–78) five years later gained significant territorial holdings for the Habsburgs in Austria, the cornerstone of their empire. By the sixteenth century, the imperial title was long regarded as hereditary, allowing the Habsburg dominion to expand dramatically over continental Europe not only through military conquest but also through carefully chosen marriage alliances.

Meagher, Jennifer. “The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/habs/hd_habs.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Zophy, Jonathan W., comp. An Annotated Bibliography of the Holy Roman Empire . New York: Greenwood Press, 1986.

Additional Essays by Jennifer Meagher

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Genre Painting in Northern Europe .” (April 2008)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ The Pre-Raphaelites .” (October 2004)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Italian Painting of the Later Middle Ages .” (September 2010)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Gerard David (born about 1455, died 1523) .” (June 2009)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Petrus Christus (active by 1444, died 1475/76) .” (December 2008)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Still-Life Painting in Southern Europe, 1600–1800 .” (June 2008)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art .” (October 2004)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Botanical Imagery in European Painting .” (August 2007)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Commedia dell’arte .” (July 2007)

- Meagher, Jennifer. “ Food and Drink in European Painting, 1400–1800 .” (May 2009)

Related Essays

- Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage

- Famous Makers of Arms and Armors and European Centers of Production

- Patronage at the Later Valois Courts (1461–1589)

- The Reformation

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples

- Burgundian Netherlands: Private Life

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400–1600

- Fashion in European Armor, 1500–1600

- Fontainebleau

- The Greater Ottoman Empire, 1600–1800

- Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617)

- Jan Gossart (ca. 1478–1532) and His Circle

- Northern Italian Renaissance Painting

- Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe

- The Papacy during the Renaissance

- Prague during the Rule of Rudolf II (1583–1612)

- The Printed Image in the West: Woodcut

- Renaissance Drawings: Material and Function

- The Roman Empire (27 B.C.–393 A.D.)

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Lombardy

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Venice and the Veneto

- Woodcut Book Illustration in Renaissance Italy: Florence in the 1490s

- Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- France, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Italian Peninsula, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Mexico and Central America, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- South America, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- Carolingian Art

- Central Europe

- Christianity

- Frankish Art

- High Renaissance

- Holy Roman Empire

- Iberian Peninsula

- The Netherlands

- Ottonian Art

- Renaissance Art

- Sculpture in the Round

Artist or Maker

- Abondio, Antonio

- Bruegel, Pieter, the Elder

- Cranach, Lucas, the Elder

- De Vries, Adriaen

- Emmoser, Gerhard

- Gemlich, Ambrosius

- Lochner, Kunz

- Peck, Peter

- Sadeler, Aegidius, II

- Spranger, Bartholomeus

- Veronese, Paolo

- Von Aachen, Hans

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Celestial” by Clare Vincent

- MetMedia: The Harvesters

The Ideology of the Holy Roman Empire

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

"The Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman , nor an empire ," wrote Voltaire , and this interpretation still dominates the popular imagination, so the Holy Roman Empire is treated as a bad joke, a pale parody of the glory of Rome . But was Voltaire right? Here we will explore the ideology that explains, and perhaps justifies, the name.

Renewal of the Roman Empire

The Franks were one of the many peoples who had migrated into Europe in the waning centuries of the Roman Empire. In the centuries following the fall of the Western Roman Empire , people carved out kingdoms, fought brutal wars, and rose to greatness—and fell from it—with bewildering speed. In the middle of the 8th century, Pepin the Short (r. 751-768), joined in the scrap when he usurped the throne of the Franks

Importantly, Pepin sought and got the blessing of the pope in order to get legitimacy for the new Carolingian Dynasty . As the bishop of Rome and the heart of the missionary movement, the pope had enormous prestige and influence over the other bishops to the north and west. He was the most prominent figure of the medieval church in western Europe, and with prominence came danger, so partnership with a great lord was very beneficial. However, the dynasty that Pepin founded is known by the name of his son, Charles the Great, Carolus Magnus , or as he is commonly known Charlemagne (l. 742-814).

Charlemagne extended what was already the greatest kingdom in western Europe until it encompassed (roughly) modern-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western Germany, Switzerland, Slovenia, and northern Italy . On top of that, he was keen to spread Christian and classical teaching, in Latin, throughout this vast realm. After Charlemagne had defeated the pope’s enemies, the Lombards of Italy, the pope took their alliance one stage further. On Christmas Day 800 CE, Pope Leo III crowned him Emperor of the Romans. The story goes that Charlemagne was shocked and humbled by such an honour, but very likely this was a shrewd political move by both him and Leo to cement the prestige of the Church and the Crown.

The lands of the Franks fractured on the death of Charlemagne’s son. The Treaty of Verdun, in 843, divided the Carolingian Empire among Charlemagne's grandsons. In theory, the northern Italian section continued to be the site of the imperial throne, but the eastern section—East Francia, covering much of what we now call Germany—was the most powerful. The Pope had long had problems with their northerly neighbours, and just as Leo had called in Charlemagne to conquer the Lombards in exchange for the imperial title, Otto the Great, ruler of East Francia, came and conquered northern Italy in 961. A year later, in 962, he was Holy Roman Emperor and a revitalised Holy Roman Empire came into being with its heartland in Germany.

Here the deal between pope and emperor became more than a bit of back-scratching. The partnership of a glorious lord and the leader of the church in the West underpinned a new civilisation , what today we call medieval Europe. Pope and emperor became known as the Two Swords, the symbolic leaders of Northern and Western Europe, or Latin Christendom. The pope would represent the shared religious life while the emperor would represent the political world they shared.

Emperor was not just some fancy title. It meant being the heir to mighty Rome, whose history sat heavily on the shoulders of Europe. To understand this, we need to look at the Old Testament Book of Daniel. Daniel prophesied that there would be four world empires before the Apocalypse. Translatio imperii was the name for how one world empire’s mantle was taken up by the next. In Late Antiquity, Christian interpretation of this prophecy was that each empire had shifted a little west, culminating in the Roman Empire. Given the world had not yet ended, as far as anyone could tell, this concept of translatio imperii could inspire and legitimise the renovation of a Christian Roman Empire, here in the post-imperial kingdoms of the far West. The revived Roman Empire was simply a continuation of the final earthly empire, and the people of Europe would see in the Apocalypse under its guidance.

The Byzantine Empire still claimed to be the Roman Empire, but the Latin West had an increasing sense of separation from the Greek East. Although the eastern and western churches were not yet formally divided in Charlemagne’s time, their cultures and associations had grown far apart. The western church, importantly, was dominated by the pope in Rome, while according to the East, he was only one bishop among many. The idea of a separate, western, Latin Christian-Roman civilisation made sense to the people who lived there. They tended to describe their state as the Renewal of the Roman Empire ( Renovatio imperii Romanorum ) rather than the Holy Roman Empire - that term took over in the 1100s - but the concept is the same.

Understood in this light, the light in which people at the time would have seen it, the combination of terms makes sense:

- Holy, the true Christians, the right-believers who uphold God ’s truth in a world of heretics and heathens;

- Roman, the heirs of the Roman Empire and centred on the spiritual primacy of the city of Rome, whose bishop is representative of our shared religious life;

- Empire, led by an Emperor, the one ruler recognised by all the civilisation as the highest in rank and first in precedence, whose special authority represents common civilisation.

Interestingly the Eastern Roman Empire would later follow the same idea on different tracks. The Greek Orthodox and Latin Catholic Churches are considered to have officially split when the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople mutually excommunicated one another in 1054. The peoples who would become the East Slav had long been heavily influenced by the Greek Orthodox culture emanating from the Byzantines. After 1453: the fall of Constantinople to the Muslim Ottoman Empire , Moscow would claim the translatio imperii and call itself the ‘Third Rome’ with a caesar ( Tsar ) at the head.

Conflict between Pope & Emperor

This image of the Two Swords, pope and emperor as the ruler-representatives of Latin Christendom, was a rather dubious interpretation of a passage in Luke: "The disciples said, 'See, Lord, here are two swords.' 'That is enough,' he replied." (22:37-38). If it was built on shaky biblical foundations, the political ones soon cracked, too, and the Two Swords started to clash against each other.

First, reform movements in the 1100s energised the Church. They saw the Church as too lax, riddled with sin, and wanted to clamp down on priests getting married and monks living in luxury. The great Cluniac reforms sought to purify the daily life of medieval monks , and Pope Gregory VII wanted to impose good order and morality on all his priests, not just monks living in a medieval monastery . Now the church could not accept being a mere legitimising deputy to whoever happened to be in power, and because of its new, strict, hierarchical organisation, it had the power to fight for its influence.

Second, the Normans had entered Italy at the beginning of the 1000s. These warriors of fierce reputation had the power to fight for the pope and, as newcomers, craved the authority the church could give them. They did not always get along, but they always had the option of allying with the pope, who could now have a lordly protector other than the emperor.

The most famous example of a conflict featuring the pope against the emperor is the so-called Investiture Controversy . In 1076, Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085) excommunicated Henry IV , Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1084-1105) after they disputed who could choose the bishop of Milan. It might seem like a very disproportionate action to a petty dispute, but the right to invest the bishops within the empire with the symbols of their office was deeply important to their authority. Unfortunately for Henry, his excommunication was the green light for a number of disaffected nobles to rise against him. He diffused the situation marvellously when he walked to Canossa, where Gregory was staying, and knelt barefoot in the snow until Gregory agreed to absolve him.

However, the question of investiture rumbled on, many more battles were fought, many more people died. The Concordat of Worms was a patch-up compromise in 1122, but the underlying tension between these two pre-eminent figures remained. Neither could quite fully assert their authority over the other, and conflict flared up again and again. Pope John XXII and Emperor Louis IV’s struggle in the 14th century is memorably depicted in Umberto Eco’s bestselling novel The Name of the Rose .

So the Two Swords stayed at each other's throats. It never worked seamlessly or, frankly, even particularly well. However, conflict should not be interpreted as failure . There was so much controversy precisely because the issue mattered to those involved. The Pope and the Emperor were like two boxers fighting in an arena they had built for a trophy they had invented. They were bickering over their place and relative power within the framework they had set up. It was very hard—and not at all in their interests—to think outside of that framework. The fact that they fought so hard is indicative of how important it was to them to claim the symbolic leadership of the new civilisation they had founded.

Sovereignty: Both Swords Broken

Over the course of the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire began to lose its pre-eminence among the powers of Europe. The Two Swords concept gradually faded in relevance. For sure, there were mighty emperors like Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1155-1190) and his grandson Frederick II (r. 1220-1250), who conquered Sicily and even briefly liberated Jerusalem in the Sixth Crusade . Occasionally they received direct homage from other kings, as when Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1191-1197) captured Richard I of England , (aka Richard the Lionheart, r. 1189-1199) in 1193. Of course, Richard did this under duress, but the fact it was possible is important. King Richard could not have legally given submission to any other monarch in Europe because no other monarch in Europe had a title that outranked. However, the claim to universal dominion was limited to occasions like this.

Beyond the lands they held with their kingly titles, like Germany and northern Italy, the emperors had little authority. They held court and raised their armies more in their capacities as Kings of Germany rather than Holy Roman Emperors. Philosophers began to argue for the sovereignty of monarchs and cities . That means that each king, queen, and city-state was free to rule as they wished within their realm over temporal matters, without reference to the emperor. In spiritual matters, they still had to respect the church, of course. Some scholars argued that this was a right as a member of the universal empire, some that the Roman Empire had never been restored at all, and others that it sprang from the special laws and customs of each people. Whatever the details, the effect was the same: the rejection of imperial authority by Europe outside the empire.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The emperor’s vassals in Germany continued to assert their independence. In 1078, during the Investiture Controversy, the strongest of these vassals had responded to Gregory’s excommunication of Henry IV by electing a new king. Their ‘anti-king’ died within two years, and Henry had regained the initiative by then, but the legacy of that action was that the most prominent German princes reserved the right to decide who the next king of Germany would be. Candidates now had to placate and bribe these electors and so they stayed very commanding and autonomous. They even broke the link between the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor when they declared, in 1356, that the imperial title would be assumed automatically by whoever they elected as King of Germany. This made successions smoother, and the electors more influential, but damaged the idea that the empire might represent the Latin Christian world.

Europe’s shared civilisation was changing. Voltaire called it "a sort of great Republic divided into several states" of which the empire was only one. It had, at best, ceremonial precedence, a first among equals kind of title. Even when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556) united the Holy Roman Empire with Spain and its vast overseas colonies and it looked as if a universal empire was once again possible, the states of Europe jealously guarded their sovereignty. Henry VIII of England ’s (r. 1509-1547) 1533 Act in Restraint of Appeals, part of his break with the Catholic Church, begins by stating that "this Realm of England is an Empire". The point of this flourish was to assert that England would respect no law but its own. It was explicitly rejecting the idea that anyone was above the king. Of course, this was directed at the pope. The medieval concept of sovereignty had rejected the emperor, now Henry VIII was taking the logical next step and rejecting the pope, too. In the duel of the Two Swords, both lost.

However, the Holy Roman Empire was not just another European state. Outsiders may not have paid its imperial trappings much mind by the Early Modern Period (from about 1500 onwards), but its peculiar, imperial history gave it special features and special meaning to the people who lived in its boundaries.

Charlemagne changed Europe forever when he was crowned in Rome on Christmas Day 800, so too did a German monk named Martin Luther when he fixed his 95 theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral on Halloween 1517. Luther set in motion a chain of events that we now called the Protestant Reformation . This was the context to England’s break with Rome, and that was only one of many revolutionary events sparked by reformers like Luther.

Religion tore apart the empire for a hundred years . The very word Protestant comes from those Lutheran princes who protested a Catholic decision in the Reichstag (the meeting of all the rulers in the empire) of 1529. Those Protestants formed the Schmalkaldic League and negotiated the Peace of Augsburg (1555) in which, despite their defeat in war, they got official privileges to practice their religion. As the Spanish Netherlands and France descended into civil war, Catholic and Lutheran princes alike rallied around the empire as a neutral framework in which they could practice their religions. The settlement broke down as certain influential princes converted to Calvinism, another form of Protestantism not accepted by the Peace of Augsburg, and the different denominations bickered over whose candidates would control the lucrative prince-archbishoprics. These tensions exploded while the emperor was distracted fighting the Ottomans. Many historians consider the subsequent Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) as the real breakup of the Holy Roman Empire, a time when the whole edifice descended into horrifying butchery and, afterwards, was nothing but a hollow shell. Indeed, Voltaire wrote his famous quotation in the period after the Thirty Years’ War.

For the people of the Holy Roman Empire, though, all of these were civil wars into which external powers (controversially) intervened. People were fighting inside their empire over disagreements about what it should become. Unlike Anglican England, Lutheran Sweden, or Catholic France, the empire accepted several Christianities and could do this because it was not the property of a single dynasty or dominated by a single group. It remained a non-ethnic, non-religious, overarching identity that could embrace many particular and local identities. Where people stood inside that framework was perpetually the source of conflict, on and off the battlefield, but the framework itself survived. The final death of the empire in the first years of the 19th century was the omen of new, very different ideas about empires.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Christopher Clark;. Iron Kingdom. Penguin; edition (2007-09-06), 2021.

- Hawes, James. The Shortest History of Germany―A Retelling for Our Times . The Experiment, 2019.

- History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps: Two Swords

- In Our Time, The Concordat of Worms , accessed 20 Jun 2021.

- Jenny Benham. Peacemaking in the Middle Ages: Principles and Practice. 2011

- Latham, Andrew. Theorizing Medieval Geopolitics. Routledge, 2016.

- Pipes, Richard. Russia under the Old Regime. Penguin Books, 1997.

- The 30 Years' War (1618-48) and the Second Defenestration of Prague - Professor Peter Wilson , accessed 20 Jun 2021.

- Voltaire. "17: Christian Europe as a Great Republic?." The Idea of Europe , edited by Seth, Catriona & von Kulessa, Rotraud. Open Book Publishers, 2017.

- Voltaire. An essay on universal history, the manners, and spirit of nations, from the reign.. Gale ECCO, Print Editions, 2010.

- Walter Ullman. "This Realm of England is an Empire." Ecclesiastical History , 3/2/2011, pp. 175 - 203.

- Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome. Penguin Books, 2010.

- Wilson, Peter H. The Holy Roman Empire. Penguin UK, 2017.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

Investiture Controversy

Protestant Reformation

Ten Protestant Reformation Facts You Need to Know

Counter-Reformation

The Printing Press & the Protestant Reformation

Ten Women of the Protestant Reformation

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Grief, I. T. (2021, June 22). The Ideology of the Holy Roman Empire . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1786/the-ideology-of-the-holy-roman-empire/

Chicago Style

Grief, Isaac Toman. " The Ideology of the Holy Roman Empire ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified June 22, 2021. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1786/the-ideology-of-the-holy-roman-empire/.

Grief, Isaac Toman. " The Ideology of the Holy Roman Empire ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 22 Jun 2021. Web. 29 Aug 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Isaac Toman Grief , published on 22 June 2021. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Nature of the empire

Religious origins

Political origins.

- Coronation of Charlemagne as emperor

- The Carolingian Empire

- The Ottonian Empire

- The Investiture Controversy

- The Hohenstaufen emperors

- The effect of the Reformation

- The end of the empire

- Holy Roman emperors

- How was the Holy Roman Empire formed?

- Why did the Holy Roman Empire fall?

- What did Charles V try to accomplish during his reign as Holy Roman Emperor?

- What were the greatest threats to Charles V’s empire?

- Why did Charles V abdicate his rule?

Origins of the empire and sources of imperial ideas

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Deutsches Historisches Museum - “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation 962-1806”

- Chemistry LibreTexts - The Holy Roman Empire

- World History Encyclopedia - Holy Roman Empire

- Khan Academy - The Roman Empire

- GlobalSecurity.org - Holy Roman Empire

- The History Learning Site - Holy Roman Empire

- Holy Roman Empire - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Holy Roman Empire - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

There was no inherent reason why, after the fall of the Roman Empire in the West in 476 and the establishment there of Germanic kingdoms, there should ever again have been an empire , still less a Roman empire, in western Europe . The reason this took place is to be sought (1) in certain local events in Rome in the years and months immediately preceding Charlemagne’s coronation in 800, and (2) in certain long-standing tendencies that made this particular solution of a difficult situation thinkable. These long-standing tendencies are to be regarded as preconditions rather than causes of the coronation; they do not account for it, but without them it is difficult to imagine how it could have taken place.

The first is the persistence, despite the fact that it was no longer a political reality west of Italy , of the idea of the universal and eternal Roman Empire. The importance of this tradition may easily be exaggerated. After the establishment of the Germanic kingdoms, kings such as Clovis in Gaul and Theodoric the Great in Italy were glad to accept Roman titles from the Byzantine emperor, who sought to maintain the formal unity of the Roman Empire by treating them as his vicars and lieutenants; but this was a short-lived expedient. By the 8th century any sense of belonging to the empire, by then confined to eastern Europe, had disappeared in the West.

Far more effective in the minds of the barbarian peoples of the West was the idea of the Imperium Christianum, or “Christian Empire,” which took shape after the conversion of Constantine the Great and the reconciliation between Christianity and the Roman Empire. Not only did the Christian church become a state church, including in its liturgy prayers for the empire and the emperor, but it also brought the Roman Empire into the framework of Christian eschatology (doctrine of last things), as the last of the world monarchies whose end would mark the inception of the kingdom of God. Through Christian iconography and through the liturgy the church’s view of the empire as a vehicle of God’s will, for the Christianization of the world, became prevalent. It was expressed with peculiar force in the letters of Charlemagne’s adviser Alcuin .

Apart from the persistence of the idea of a Christian Roman Empire, a third precondition for the establishment of an empire in the West was the existence of a candidate of sufficient power and standing in the person of the Frankish king. The Frankish kingdom expanded until it comprised most of western Europe, and it acquired the Lombard kingdom in northern Italy in 774. The importance of the ties forged by Charlemagne’s immediate predecessors with the papacy are obvious. Though it is scarcely true that Charlemagne’s accession to the empire was simply a consequence of this expansion, his outstanding position was evidently a precondition of his elevation to the imperial throne.

When one turns from the preconditions to the causes of the events of 800 and from the realm of ideas to that of political facts, one enters another world. It is the world of the Byzantine (or Eastern) Empire, of which the pope was a subject, confirmed in his bishopric like other bishops by the Byzantine emperor. By the 8th century, however, the imperial position in Italy, centred in the Exarchate of Ravenna, was crumbling. Confronted by the power of Islam , the empire concentrated on the problems of the East and was unable to defend its Italian lands from the Lombards , who had entered Italy in 568. Furthermore, the Byzantine emperors of the Isaurian dynasty , of whom the first was Leo III (717–741), were estranged from the papacy by the Iconoclastic Controversy . Hitherto fear of the Lombards had kept the popes faithful to the Byzantine emperor and to the exarch in Ravenna, but the situation changed. When the Lombards renewed their advance southward, taking Ravenna in 751 and driving out the exarch, the pope appealed in vain to the Byzantine emperor . He then, in an epoch-making turn to the West, sought assistance from the Frankish king Pippin III the Short, who invaded Italy and reduced the Lombard king Aistulf to submission (754). Returning in 756, Pippin bestowed on the papacy the territories belonging to the exarchate. Thus was born both the temporal power of the papacy and the close alliance between the papacy and the Frankish monarchy .

Particularly significant of the anomalous position that had arisen in Italy was the action of the pope in conferring on the Frankish king the title of patrician, which could legally be conferred only by the emperor; in the form the pope gave it ( patricius Romanorum ), the title was meant to authorize its possessor to defend and support the Holy See against its foes. Even so, the papacy was reluctant to break its constitutional links with the imperial system, and this was particularly so under Pope Adrian I (772–795), after Charlemagne had in 774 defeated the last independent Lombard king, Desiderius, and taken his kingdom. As king of Lombardy the defender might become as dangerous to the pope as those against whom he had provided defense.

The events briefly related show, first, the growing estrangement between East and West; second, the difficult position of the pope between the Byzantine emperor and the Frankish king; third, the tenuousness of the imperial hold over Rome and central Italy. After the expulsion of the exarch in 751, the pope himself, in de facto possession, probably hoped to become the emperor’s successor in the West. Whether the document itself belongs to the 750s or not, this was the sense of the forged Donation of Constantine , in which the emperor Constantine I is represented as having conferred on Pope Sylvester I the imperial palace of the Lateran, the imperial insignia, and “all the provinces, places and cities of Italy and the western regions.” Such ambitions, however, proved illusory when Charlemagne became king of the Lombards. When it was even rumoured that Charles intended to depose Adrian and set up a Frankish pope in his place, it would have been folly for the pope to think of formal severance from the existing empire. Nevertheless, the empire’s shadowy titles were unlikely to be respected long in Italy unless the Byzantine emperor took action. From 781 papal documents were no longer being dated by the emperor’s regnal year, and the pope was minting his own coins.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Holy Roman Empire 1300–1650

Introduction, general overviews.

- Primary Sources

- Interpreting Imperial Political Culture

- Political Identity and the “German Nation”

- Kings and Emperors

- Territories, Towns, and Regional History within the Empire

- Gender History

- Religious Change and Confessionalization

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Charles V, Emperor

- Cities and Urban Patriciates

- Female Monarchy in Renaissance and Reformation Europe

- German Reformation

- Maximilian I, Emperor

- The Reformation

- The Thirty Years War

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Giulia Gonzaga

- Margaret Cavendish

- Merchant Adventurers

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Holy Roman Empire 1300–1650 by Duncan Hardy LAST REVIEWED: 22 September 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 22 September 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0472