How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

- 4 minute read

- 25.1K views

Table of Contents

The discussion section in scientific manuscripts might be the last few paragraphs, but its role goes far beyond wrapping up. It’s the part of an article where scientists talk about what they found and what it means, where raw data turns into meaningful insights. Therefore, discussion is a vital component of the article.

An excellent discussion is well-organized. We bring to you authors a classic 6-step method for writing discussion sections, with examples to illustrate the functions and specific writing logic of each step. Take a look at how you can impress journal reviewers with a concise and focused discussion section!

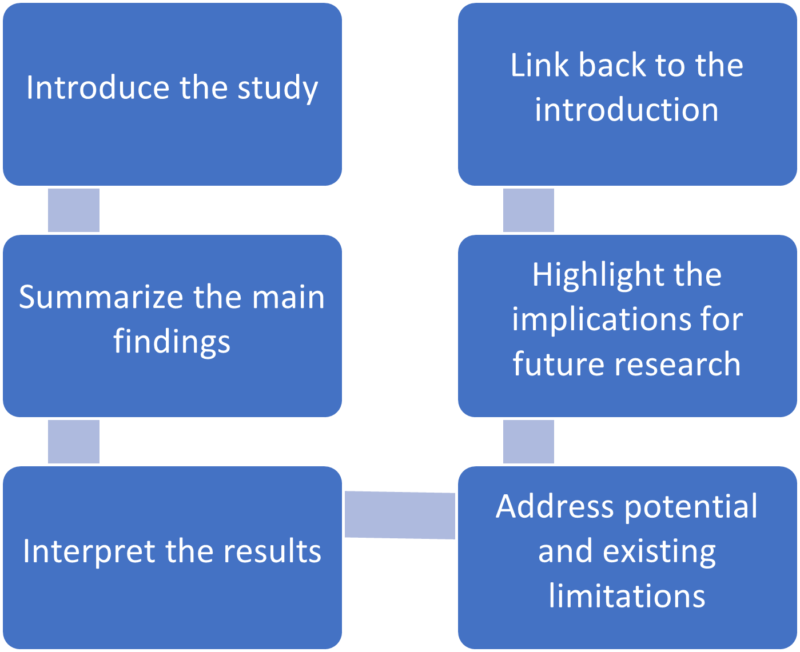

Discussion frame structure

Conventionally, a discussion section has three parts: an introductory paragraph, a few intermediate paragraphs, and a conclusion¹. Please follow the steps below:

1.Introduction—mention gaps in previous research¹⁻ ²

Here, you orient the reader to your study. In the first paragraph, it is advisable to mention the research gap your paper addresses.

Example: This study investigated the cognitive effects of a meat-only diet on adults. While earlier studies have explored the impact of a carnivorous diet on physical attributes and agility, they have not explicitly addressed its influence on cognitively intense tasks involving memory and reasoning.

2. Summarizing key findings—let your data speak ¹⁻ ²

After you have laid out the context for your study, recapitulate some of its key findings. Also, highlight key data and evidence supporting these findings.

Example: We found that risk-taking behavior among teenagers correlates with their tendency to invest in cryptocurrencies. Risk takers in this study, as measured by the Cambridge Gambling Task, tended to have an inordinately higher proportion of their savings invested as crypto coins.

3. Interpreting results—compare with other papers¹⁻²

Here, you must analyze and interpret any results concerning the research question or hypothesis. How do the key findings of your study help verify or disprove the hypothesis? What practical relevance does your discovery have?

Example: Our study suggests that higher daily caffeine intake is not associated with poor performance in major sporting events. Athletes may benefit from the cardiovascular benefits of daily caffeine intake without adversely impacting performance.

Remember, unlike the results section, the discussion ideally focuses on locating your findings in the larger body of existing research. Hence, compare your results with those of other peer-reviewed papers.

Example: Although Miller et al. (2020) found evidence of such political bias in a multicultural population, our findings suggest that the bias is weak or virtually non-existent among politically active citizens.

4. Addressing limitations—their potential impact on the results¹⁻²

Discuss the potential impact of limitations on the results. Most studies have limitations, and it is crucial to acknowledge them in the intermediary paragraphs of the discussion section. Limitations may include low sample size, suspected interference or noise in data, low effect size, etc.

Example: This study explored a comprehensive list of adverse effects associated with the novel drug ‘X’. However, long-term studies may be needed to confirm its safety, especially regarding major cardiac events.

5. Implications for future research—how to explore further¹⁻²

Locate areas of your research where more investigation is needed. Concluding paragraphs of the discussion can explain what research will likely confirm your results or identify knowledge gaps your study left unaddressed.

Example: Our study demonstrates that roads paved with the plastic-infused compound ‘Y’ are more resilient than asphalt. Future studies may explore economically feasible ways of producing compound Y in bulk.

6. Conclusion—summarize content¹⁻²

A good way to wind up the discussion section is by revisiting the research question mentioned in your introduction. Sign off by expressing the main findings of your study.

Example: Recent observations suggest that the fish ‘Z’ is moving upriver in many parts of the Amazon basin. Our findings provide conclusive evidence that this phenomenon is associated with rising sea levels and climate change, not due to elevated numbers of invasive predators.

A rigorous and concise discussion section is one of the keys to achieving an excellent paper. It serves as a critical platform for researchers to interpret and connect their findings with the broader scientific context. By detailing the results, carefully comparing them with existing research, and explaining the limitations of this study, you can effectively help reviewers and readers understand the entire research article more comprehensively and deeply¹⁻² , thereby helping your manuscript to be successfully published and gain wider dissemination.

In addition to keeping this writing guide, you can also use Elsevier Language Services to improve the quality of your paper more deeply and comprehensively. We have a professional editing team covering multiple disciplines. With our profound disciplinary background and rich polishing experience, we can significantly optimize all paper modules including the discussion, effectively improve the fluency and rigor of your articles, and make your scientific research results consistent, with its value reflected more clearly. We are always committed to ensuring the quality of papers according to the standards of top journals, improving the publishing efficiency of scientific researchers, and helping you on the road to academic success. Check us out here !

Type in wordcount for Standard Total: USD EUR JPY Follow this link if your manuscript is longer than 12,000 words. Upload

References:

- Masic, I. (2018). How to write an efficient discussion? Medical Archives , 72(3), 306. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2018.72.306-307

- Şanlı, Ö., Erdem, S., & Tefik, T. (2014). How to write a discussion section? Urology Research & Practice , 39(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2013.049

Navigating “Chinglish” Errors in Academic English Writing

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

You may also like.

Submission 101: What format should be used for academic papers?

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE: Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE: If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in and of itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. "How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section." Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Blair Lorrie. “Choosing a Methodology.” In Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation , Teaching Writing Series. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2016), pp. 49-72; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Kallet, Richard H. “How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper.” Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004):1229-1232; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Rudestam, Kjell Erik and Rae R. Newton. “The Method Chapter: Describing Your Research Plan.” In Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process . (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015), pp. 87-115; What is Interpretive Research. Institute of Public and International Affairs, University of Utah; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

To locate data and statistics, GO HERE .

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between the application of theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics . Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship. S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Methods and the Methodology

Do not confuse the terms "methods" and "methodology." As Schneider notes, a method refers to the technical steps taken to do research . Descriptions of methods usually include defining and stating why you have chosen specific techniques to investigate a research problem, followed by an outline of the procedures you used to systematically select, gather, and process the data [remember to always save the interpretation of data for the discussion section of your paper].

The methodology refers to a discussion of the underlying reasoning why particular methods were used . This discussion includes describing the theoretical concepts that inform the choice of methods to be applied, placing the choice of methods within the more general nature of academic work, and reviewing its relevance to examining the research problem. The methodology section also includes a thorough review of the methods other scholars have used to study the topic.

Bryman, Alan. "Of Methods and Methodology." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 3 (2008): 159-168; Schneider, Florian. “What's in a Methodology: The Difference between Method, Methodology, and Theory…and How to Get the Balance Right?” PoliticsEastAsia.com. Chinese Department, University of Leiden, Netherlands.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Aug 27, 2024 1:14 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Discussion Section for a Research Paper

We’ve talked about several useful writing tips that authors should consider while drafting or editing their research papers. In particular, we’ve focused on figures and legends , as well as the Introduction , Methods , and Results . Now that we’ve addressed the more technical portions of your journal manuscript, let’s turn to the analytical segments of your research article. In this article, we’ll provide tips on how to write a strong Discussion section that best portrays the significance of your research contributions.

What is the Discussion section of a research paper?

In a nutshell, your Discussion fulfills the promise you made to readers in your Introduction . At the beginning of your paper, you tell us why we should care about your research. You then guide us through a series of intricate images and graphs that capture all the relevant data you collected during your research. We may be dazzled and impressed at first, but none of that matters if you deliver an anti-climactic conclusion in the Discussion section!

Are you feeling pressured? Don’t worry. To be honest, you will edit the Discussion section of your manuscript numerous times. After all, in as little as one to two paragraphs ( Nature ‘s suggestion based on their 3,000-word main body text limit), you have to explain how your research moves us from point A (issues you raise in the Introduction) to point B (our new understanding of these matters). You must also recommend how we might get to point C (i.e., identify what you think is the next direction for research in this field). That’s a lot to say in two paragraphs!

So, how do you do that? Let’s take a closer look.

What should I include in the Discussion section?

As we stated above, the goal of your Discussion section is to answer the questions you raise in your Introduction by using the results you collected during your research . The content you include in the Discussions segment should include the following information:

- Remind us why we should be interested in this research project.

- Describe the nature of the knowledge gap you were trying to fill using the results of your study.

- Don’t repeat your Introduction. Instead, focus on why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place.

- Mainly, you want to remind us of how your research will increase our knowledge base and inspire others to conduct further research.

- Clearly tell us what that piece of missing knowledge was.

- Answer each of the questions you asked in your Introduction and explain how your results support those conclusions.

- Make sure to factor in all results relevant to the questions (even if those results were not statistically significant).

- Focus on the significance of the most noteworthy results.

- If conflicting inferences can be drawn from your results, evaluate the merits of all of them.

- Don’t rehash what you said earlier in the Results section. Rather, discuss your findings in the context of answering your hypothesis. Instead of making statements like “[The first result] was this…,” say, “[The first result] suggests [conclusion].”

- Do your conclusions line up with existing literature?

- Discuss whether your findings agree with current knowledge and expectations.

- Keep in mind good persuasive argument skills, such as explaining the strengths of your arguments and highlighting the weaknesses of contrary opinions.

- If you discovered something unexpected, offer reasons. If your conclusions aren’t aligned with current literature, explain.

- Address any limitations of your study and how relevant they are to interpreting your results and validating your findings.

- Make sure to acknowledge any weaknesses in your conclusions and suggest room for further research concerning that aspect of your analysis.

- Make sure your suggestions aren’t ones that should have been conducted during your research! Doing so might raise questions about your initial research design and protocols.

- Similarly, maintain a critical but unapologetic tone. You want to instill confidence in your readers that you have thoroughly examined your results and have objectively assessed them in a way that would benefit the scientific community’s desire to expand our knowledge base.

- Recommend next steps.

- Your suggestions should inspire other researchers to conduct follow-up studies to build upon the knowledge you have shared with them.

- Keep the list short (no more than two).

How to Write the Discussion Section

The above list of what to include in the Discussion section gives an overall idea of what you need to focus on throughout the section. Below are some tips and general suggestions about the technical aspects of writing and organization that you might find useful as you draft or revise the contents we’ve outlined above.

Technical writing elements

- Embrace active voice because it eliminates the awkward phrasing and wordiness that accompanies passive voice.

- Use the present tense, which should also be employed in the Introduction.

- Sprinkle with first person pronouns if needed, but generally, avoid it. We want to focus on your findings.

- Maintain an objective and analytical tone.

Discussion section organization

- Keep the same flow across the Results, Methods, and Discussion sections.

- We develop a rhythm as we read and parallel structures facilitate our comprehension. When you organize information the same way in each of these related parts of your journal manuscript, we can quickly see how a certain result was interpreted and quickly verify the particular methods used to produce that result.

- Notice how using parallel structure will eliminate extra narration in the Discussion part since we can anticipate the flow of your ideas based on what we read in the Results segment. Reducing wordiness is important when you only have a few paragraphs to devote to the Discussion section!

- Within each subpart of a Discussion, the information should flow as follows: (A) conclusion first, (B) relevant results and how they relate to that conclusion and (C) relevant literature.

- End with a concise summary explaining the big-picture impact of your study on our understanding of the subject matter. At the beginning of your Discussion section, you stated why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place. Now, it is time to end with “how your research filled that gap.”

Discussion Part 1: Summarizing Key Findings

Begin the Discussion section by restating your statement of the problem and briefly summarizing the major results. Do not simply repeat your findings. Rather, try to create a concise statement of the main results that directly answer the central research question that you stated in the Introduction section . This content should not be longer than one paragraph in length.

Many researchers struggle with understanding the precise differences between a Discussion section and a Results section . The most important thing to remember here is that your Discussion section should subjectively evaluate the findings presented in the Results section, and in relatively the same order. Keep these sections distinct by making sure that you do not repeat the findings without providing an interpretation.

Phrase examples: Summarizing the results

- The findings indicate that …

- These results suggest a correlation between A and B …

- The data present here suggest that …

- An interpretation of the findings reveals a connection between…

Discussion Part 2: Interpreting the Findings

What do the results mean? It may seem obvious to you, but simply looking at the figures in the Results section will not necessarily convey to readers the importance of the findings in answering your research questions.

The exact structure of interpretations depends on the type of research being conducted. Here are some common approaches to interpreting data:

- Identifying correlations and relationships in the findings

- Explaining whether the results confirm or undermine your research hypothesis

- Giving the findings context within the history of similar research studies

- Discussing unexpected results and analyzing their significance to your study or general research

- Offering alternative explanations and arguing for your position

Organize the Discussion section around key arguments, themes, hypotheses, or research questions or problems. Again, make sure to follow the same order as you did in the Results section.

Discussion Part 3: Discussing the Implications

In addition to providing your own interpretations, show how your results fit into the wider scholarly literature you surveyed in the literature review section. This section is called the implications of the study . Show where and how these results fit into existing knowledge, what additional insights they contribute, and any possible consequences that might arise from this knowledge, both in the specific research topic and in the wider scientific domain.

Questions to ask yourself when dealing with potential implications:

- Do your findings fall in line with existing theories, or do they challenge these theories or findings? What new information do they contribute to the literature, if any? How exactly do these findings impact or conflict with existing theories or models?

- What are the practical implications on actual subjects or demographics?

- What are the methodological implications for similar studies conducted either in the past or future?

Your purpose in giving the implications is to spell out exactly what your study has contributed and why researchers and other readers should be interested.

Phrase examples: Discussing the implications of the research

- These results confirm the existing evidence in X studies…

- The results are not in line with the foregoing theory that…

- This experiment provides new insights into the connection between…

- These findings present a more nuanced understanding of…

- While previous studies have focused on X, these results demonstrate that Y.

Step 4: Acknowledging the limitations

All research has study limitations of one sort or another. Acknowledging limitations in methodology or approach helps strengthen your credibility as a researcher. Study limitations are not simply a list of mistakes made in the study. Rather, limitations help provide a more detailed picture of what can or cannot be concluded from your findings. In essence, they help temper and qualify the study implications you listed previously.

Study limitations can relate to research design, specific methodological or material choices, or unexpected issues that emerged while you conducted the research. Mention only those limitations directly relate to your research questions, and explain what impact these limitations had on how your study was conducted and the validity of any interpretations.

Possible types of study limitations:

- Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

- Lack of previous research studies on the topic

- Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

- Limited access to data

- Time constraints in properly preparing and executing the study

After discussing the study limitations, you can also stress that your results are still valid. Give some specific reasons why the limitations do not necessarily handicap your study or narrow its scope.

Phrase examples: Limitations sentence beginners

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first limitation is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

Discussion Part 5: Giving Recommendations for Further Research

Based on your interpretation and discussion of the findings, your recommendations can include practical changes to the study or specific further research to be conducted to clarify the research questions. Recommendations are often listed in a separate Conclusion section , but often this is just the final paragraph of the Discussion section.

Suggestions for further research often stem directly from the limitations outlined. Rather than simply stating that “further research should be conducted,” provide concrete specifics for how future can help answer questions that your research could not.

Phrase examples: Recommendation sentence beginners

- Further research is needed to establish …

- There is abundant space for further progress in analyzing…

- A further study with more focus on X should be done to investigate…

- Further studies of X that account for these variables must be undertaken.

Consider Receiving Professional Language Editing

As you edit or draft your research manuscript, we hope that you implement these guidelines to produce a more effective Discussion section. And after completing your draft, don’t forget to submit your work to a professional proofreading and English editing service like Wordvice, including our manuscript editing service for paper editing , cover letter editing , SOP editing , and personal statement proofreading services. Language editors not only proofread and correct errors in grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting but also improve terms and revise phrases so they read more naturally. Wordvice is an industry leader in providing high-quality revision for all types of academic documents.

For additional information about how to write a strong research paper, make sure to check out our full research writing series !

Wordvice Writing Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Additional Academic Resources

- Guide for Authors. (Elsevier)

- How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper. (Bates College)

- Structure of a Research Paper. (University of Minnesota Biomedical Library)

- How to Choose a Target Journal (Springer)

- How to Write Figures and Tables (UNC Writing Center)

How To Write The Discussion Chapter

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

If you’re reading this, chances are you’ve reached the discussion chapter of your thesis or dissertation and are looking for a bit of guidance. Well, you’ve come to the right place ! In this post, we’ll unpack and demystify the typical discussion chapter in straightforward, easy to understand language, with loads of examples .

Overview: The Discussion Chapter

- What the discussion chapter is

- What to include in your discussion

- How to write up your discussion

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free discussion template

What (exactly) is the discussion chapter?

The discussion chapter is where you interpret and explain your results within your thesis or dissertation. This contrasts with the results chapter, where you merely present and describe the analysis findings (whether qualitative or quantitative ). In the discussion chapter, you elaborate on and evaluate your research findings, and discuss the significance and implications of your results .

In this chapter, you’ll situate your research findings in terms of your research questions or hypotheses and tie them back to previous studies and literature (which you would have covered in your literature review chapter). You’ll also have a look at how relevant and/or significant your findings are to your field of research, and you’ll argue for the conclusions that you draw from your analysis. Simply put, the discussion chapter is there for you to interact with and explain your research findings in a thorough and coherent manner.

What should I include in the discussion chapter?

First things first: in some studies, the results and discussion chapter are combined into one chapter . This depends on the type of study you conducted (i.e., the nature of the study and methodology adopted), as well as the standards set by the university. So, check in with your university regarding their norms and expectations before getting started. In this post, we’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as this is most common.

Basically, your discussion chapter should analyse , explore the meaning and identify the importance of the data you presented in your results chapter. In the discussion chapter, you’ll give your results some form of meaning by evaluating and interpreting them. This will help answer your research questions, achieve your research aims and support your overall conclusion (s). Therefore, you discussion chapter should focus on findings that are directly connected to your research aims and questions. Don’t waste precious time and word count on findings that are not central to the purpose of your research project.

As this chapter is a reflection of your results chapter, it’s vital that you don’t report any new findings . In other words, you can’t present claims here if you didn’t present the relevant data in the results chapter first. So, make sure that for every discussion point you raise in this chapter, you’ve covered the respective data analysis in the results chapter. If you haven’t, you’ll need to go back and adjust your results chapter accordingly.

If you’re struggling to get started, try writing down a bullet point list everything you found in your results chapter. From this, you can make a list of everything you need to cover in your discussion chapter. Also, make sure you revisit your research questions or hypotheses and incorporate the relevant discussion to address these. This will also help you to see how you can structure your chapter logically.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the discussion chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear idea of what the discussion chapter is and what it needs to include, let’s look at how you can go about structuring this critically important chapter. Broadly speaking, there are six core components that need to be included, and these can be treated as steps in the chapter writing process.

Step 1: Restate your research problem and research questions

The first step in writing up your discussion chapter is to remind your reader of your research problem , as well as your research aim(s) and research questions . If you have hypotheses, you can also briefly mention these. This “reminder” is very important because, after reading dozens of pages, the reader may have forgotten the original point of your research or been swayed in another direction. It’s also likely that some readers skip straight to your discussion chapter from the introduction chapter , so make sure that your research aims and research questions are clear.

Step 2: Summarise your key findings

Next, you’ll want to summarise your key findings from your results chapter. This may look different for qualitative and quantitative research , where qualitative research may report on themes and relationships, whereas quantitative research may touch on correlations and causal relationships. Regardless of the methodology, in this section you need to highlight the overall key findings in relation to your research questions.

Typically, this section only requires one or two paragraphs , depending on how many research questions you have. Aim to be concise here, as you will unpack these findings in more detail later in the chapter. For now, a few lines that directly address your research questions are all that you need.

Some examples of the kind of language you’d use here include:

- The data suggest that…

- The data support/oppose the theory that…

- The analysis identifies…

These are purely examples. What you present here will be completely dependent on your original research questions, so make sure that you are led by them .

Step 3: Interpret your results

Once you’ve restated your research problem and research question(s) and briefly presented your key findings, you can unpack your findings by interpreting your results. Remember: only include what you reported in your results section – don’t introduce new information.

From a structural perspective, it can be a wise approach to follow a similar structure in this chapter as you did in your results chapter. This would help improve readability and make it easier for your reader to follow your arguments. For example, if you structured you results discussion by qualitative themes, it may make sense to do the same here.

Alternatively, you may structure this chapter by research questions, or based on an overarching theoretical framework that your study revolved around. Every study is different, so you’ll need to assess what structure works best for you.

When interpreting your results, you’ll want to assess how your findings compare to those of the existing research (from your literature review chapter). Even if your findings contrast with the existing research, you need to include these in your discussion. In fact, those contrasts are often the most interesting findings . In this case, you’d want to think about why you didn’t find what you were expecting in your data and what the significance of this contrast is.

Here are a few questions to help guide your discussion:

- How do your results relate with those of previous studies ?

- If you get results that differ from those of previous studies, why may this be the case?

- What do your results contribute to your field of research?

- What other explanations could there be for your findings?

When interpreting your findings, be careful not to draw conclusions that aren’t substantiated . Every claim you make needs to be backed up with evidence or findings from the data (and that data needs to be presented in the previous chapter – results). This can look different for different studies; qualitative data may require quotes as evidence, whereas quantitative data would use statistical methods and tests. Whatever the case, every claim you make needs to be strongly backed up.

Step 4: Acknowledge the limitations of your study

The fourth step in writing up your discussion chapter is to acknowledge the limitations of the study. These limitations can cover any part of your study , from the scope or theoretical basis to the analysis method(s) or sample. For example, you may find that you collected data from a very small sample with unique characteristics, which would mean that you are unable to generalise your results to the broader population.

For some students, discussing the limitations of their work can feel a little bit self-defeating . This is a misconception, as a core indicator of high-quality research is its ability to accurately identify its weaknesses. In other words, accurately stating the limitations of your work is a strength, not a weakness . All that said, be careful not to undermine your own research. Tell the reader what limitations exist and what improvements could be made, but also remind them of the value of your study despite its limitations.

Step 5: Make recommendations for implementation and future research

Now that you’ve unpacked your findings and acknowledge the limitations thereof, the next thing you’ll need to do is reflect on your study in terms of two factors:

- The practical application of your findings

- Suggestions for future research

The first thing to discuss is how your findings can be used in the real world – in other words, what contribution can they make to the field or industry? Where are these contributions applicable, how and why? For example, if your research is on communication in health settings, in what ways can your findings be applied to the context of a hospital or medical clinic? Make sure that you spell this out for your reader in practical terms, but also be realistic and make sure that any applications are feasible.

The next discussion point is the opportunity for future research . In other words, how can other studies build on what you’ve found and also improve the findings by overcoming some of the limitations in your study (which you discussed a little earlier). In doing this, you’ll want to investigate whether your results fit in with findings of previous research, and if not, why this may be the case. For example, are there any factors that you didn’t consider in your study? What future research can be done to remedy this? When you write up your suggestions, make sure that you don’t just say that more research is needed on the topic, also comment on how the research can build on your study.

Step 6: Provide a concluding summary

Finally, you’ve reached your final stretch. In this section, you’ll want to provide a brief recap of the key findings – in other words, the findings that directly address your research questions . Basically, your conclusion should tell the reader what your study has found, and what they need to take away from reading your report.

When writing up your concluding summary, bear in mind that some readers may skip straight to this section from the beginning of the chapter. So, make sure that this section flows well from and has a strong connection to the opening section of the chapter.

Tips and tricks for an A-grade discussion chapter

Now that you know what the discussion chapter is , what to include and exclude , and how to structure it , here are some tips and suggestions to help you craft a quality discussion chapter.

- When you write up your discussion chapter, make sure that you keep it consistent with your introduction chapter , as some readers will skip from the introduction chapter directly to the discussion chapter. Your discussion should use the same tense as your introduction, and it should also make use of the same key terms.

- Don’t make assumptions about your readers. As a writer, you have hands-on experience with the data and so it can be easy to present it in an over-simplified manner. Make sure that you spell out your findings and interpretations for the intelligent layman.

- Have a look at other theses and dissertations from your institution, especially the discussion sections. This will help you to understand the standards and conventions of your university, and you’ll also get a good idea of how others have structured their discussion chapters. You can also check out our chapter template .

- Avoid using absolute terms such as “These results prove that…”, rather make use of terms such as “suggest” or “indicate”, where you could say, “These results suggest that…” or “These results indicate…”. It is highly unlikely that a dissertation or thesis will scientifically prove something (due to a variety of resource constraints), so be humble in your language.

- Use well-structured and consistently formatted headings to ensure that your reader can easily navigate between sections, and so that your chapter flows logically and coherently.

If you have any questions or thoughts regarding this post, feel free to leave a comment below. Also, if you’re looking for one-on-one help with your discussion chapter (or thesis in general), consider booking a free consultation with one of our highly experienced Grad Coaches to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

37 Comments

Thank you this is helpful!

This is very helpful to me… Thanks a lot for sharing this with us 😊

This has been very helpful indeed. Thank you.

This is actually really helpful, I just stumbled upon it. Very happy that I found it, thank you.

Me too! I was kinda lost on how to approach my discussion chapter. How helpful! Thanks a lot!

This is really good and explicit. Thanks

Thank you, this blog has been such a help.

Thank you. This is very helpful.

Dear sir/madame

Thanks a lot for this helpful blog. Really, it supported me in writing my discussion chapter while I was totally unaware about its structure and method of writing.

With regards

Syed Firoz Ahmad PhD, Research Scholar

I agree so much. This blog was god sent. It assisted me so much while I was totally clueless about the context and the know-how. Now I am fully aware of what I am to do and how I am to do it.

Thanks! This is helpful!

thanks alot for this informative website

Dear Sir/Madam,

Truly, your article was much benefited when i structured my discussion chapter.

Thank you very much!!!

This is helpful for me in writing my research discussion component. I have to copy this text on Microsoft word cause of my weakness that I cannot be able to read the text on screen a long time. So many thanks for this articles.

This was helpful

Thanks Jenna, well explained.

Thank you! This is super helpful.

Thanks very much. I have appreciated the six steps on writing the Discussion chapter which are (i) Restating the research problem and questions (ii) Summarising the key findings (iii) Interpreting the results linked to relating to previous results in positive and negative ways; explaining whay different or same and contribution to field of research and expalnation of findings (iv) Acknowledgeing limitations (v) Recommendations for implementation and future resaerch and finally (vi) Providing a conscluding summary

My two questions are: 1. On step 1 and 2 can it be the overall or you restate and sumamrise on each findings based on the reaerch question? 2. On 4 and 5 do you do the acknowlledgement , recommendations on each research finding or overall. This is not clear from your expalanattion.

Please respond.

This post is very useful. I’m wondering whether practical implications must be introduced in the Discussion section or in the Conclusion section?

Sigh, I never knew a 20 min video could have literally save my life like this. I found this at the right time!!!! Everything I need to know in one video thanks a mil ! OMGG and that 6 step!!!!!! was the cherry on top the cake!!!!!!!!!

Thanks alot.., I have gained much

This piece is very helpful on how to go about my discussion section. I can always recommend GradCoach research guides for colleagues.

Many thanks for this resource. It has been very helpful to me. I was finding it hard to even write the first sentence. Much appreciated.

Thanks so much. Very helpful to know what is included in the discussion section

this was a very helpful and useful information

This is very helpful. Very very helpful. Thanks for sharing this online!

it is very helpfull article, and i will recommend it to my fellow students. Thank you.

Superlative! More grease to your elbows.

Powerful, thank you for sharing.

Wow! Just wow! God bless the day I stumbled upon you guys’ YouTube videos! It’s been truly life changing and anxiety about my report that is due in less than a month has subsided significantly!

Simplified explanation. Well done.

The presentation is enlightening. Thank you very much.

Thanks for the support and guidance

This has been a great help to me and thank you do much

I second that “it is highly unlikely that a dissertation or thesis will scientifically prove something”; although, could you enlighten us on that comment and elaborate more please?

Sure, no problem.

Scientific proof is generally considered a very strong assertion that something is definitively and universally true. In most scientific disciplines, especially within the realms of natural and social sciences, absolute proof is very rare. Instead, researchers aim to provide evidence that supports or rejects hypotheses. This evidence increases or decreases the likelihood that a particular theory is correct, but it rarely proves something in the absolute sense.

Dissertations and theses, as substantial as they are, typically focus on exploring a specific question or problem within a larger field of study. They contribute to a broader conversation and body of knowledge. The aim is often to provide detailed insight, extend understanding, and suggest directions for further research rather than to offer definitive proof. These academic works are part of a cumulative process of knowledge building where each piece of research connects with others to gradually enhance our understanding of complex phenomena.

Furthermore, the rigorous nature of scientific inquiry involves continuous testing, validation, and potential refutation of ideas. What might be considered a “proof” at one point can later be challenged by new evidence or alternative interpretations. Therefore, the language of “proof” is cautiously used in academic circles to maintain scientific integrity and humility.

This was very helpful, thank you!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

General Research Paper Guidelines: Discussion

Discussion section.

The overall purpose of a research paper’s discussion section is to evaluate and interpret results, while explaining both the implications and limitations of your findings. Per APA (2020) guidelines, this section requires you to “examine, interpret, and qualify the results and draw inferences and conclusions from them” (p. 89). Discussion sections also require you to detail any new insights, think through areas for future research, highlight the work that still needs to be done to further your topic, and provide a clear conclusion to your research paper. In a good discussion section, you should do the following:

- Clearly connect the discussion of your results to your introduction, including your central argument, thesis, or problem statement.

- Provide readers with a critical thinking through of your results, answering the “so what?” question about each of your findings. In other words, why is this finding important?

- Detail how your research findings might address critical gaps or problems in your field

- Compare your results to similar studies’ findings

- Provide the possibility of alternative interpretations, as your goal as a researcher is to “discover” and “examine” and not to “prove” or “disprove.” Instead of trying to fit your results into your hypothesis, critically engage with alternative interpretations to your results.

For more specific details on your Discussion section, be sure to review Sections 3.8 (pp. 89-90) and 3.16 (pp. 103-104) of your 7 th edition APA manual

*Box content adapted from:

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 8 the discussion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/discussion

Limitations

Limitations of generalizability or utility of findings, often over which the researcher has no control, should be detailed in your Discussion section. Including limitations for your reader allows you to demonstrate you have thought critically about your given topic, understood relevant literature addressing your topic, and chosen the methodology most appropriate for your research. It also allows you an opportunity to suggest avenues for future research on your topic. An effective limitations section will include the following:

- Detail (a) sources of potential bias, (b) possible imprecision of measures, (c) other limitations or weaknesses of the study, including any methodological or researcher limitations.

- Sample size: In quantitative research, if a sample size is too small, it is more difficult to generalize results.

- Lack of available/reliable data : In some cases, data might not be available or reliable, which will ultimately affect the overall scope of your research. Use this as an opportunity to explain areas for future study.

- Lack of prior research on your study topic: In some cases, you might find that there is very little or no similar research on your study topic, which hinders the credibility and scope of your own research. If this is the case, use this limitation as an opportunity to call for future research. However, make sure you have done a thorough search of the available literature before making this claim.

- Flaws in measurement of data: Hindsight is 20/20, and you might realize after you have completed your research that the data tool you used actually limited the scope or results of your study in some way. Again, acknowledge the weakness and use it as an opportunity to highlight areas for future study.

- Limits of self-reported data: In your research, you are assuming that any participants will be honest and forthcoming with responses or information they provide to you. Simply acknowledging this assumption as a possible limitation is important in your research.

- Access: Most research requires that you have access to people, documents, organizations, etc.. However, for various reasons, access is sometimes limited or denied altogether. If this is the case, you will want to acknowledge access as a limitation to your research.

- Time: Choosing a research focus that is narrow enough in scope to finish in a given time period is important. If such limitations of time prevent you from certain forms of research, access, or study designs, acknowledging this time restraint is important. Acknowledging such limitations is important, as they can point other researchers to areas that require future study.

- Potential Bias: All researchers have some biases, so when reading and revising your draft, pay special attention to the possibilities for bias in your own work. Such bias could be in the form you organized people, places, participants, or events. They might also exist in the method you selected or the interpretation of your results. Acknowledging such bias is an important part of the research process.

- Language Fluency: On occasion, researchers or research participants might have language fluency issues, which could potentially hinder results or how effectively you interpret results. If this is an issue in your research, make sure to acknowledge it in your limitations section.

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: Limitations of the study . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/limitations