- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

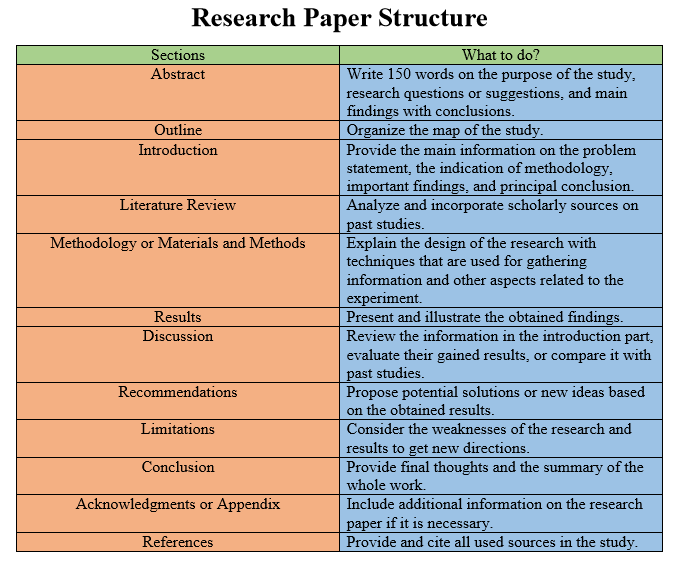

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

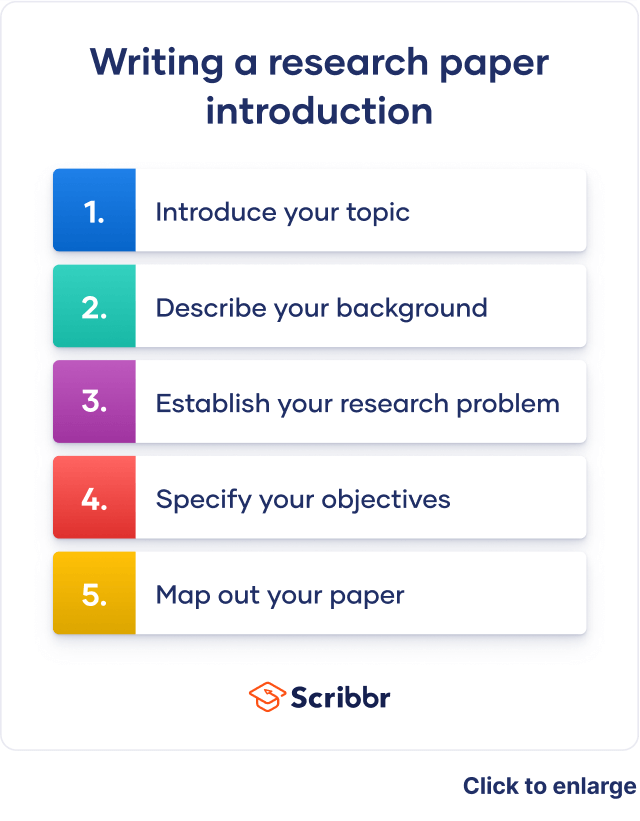

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

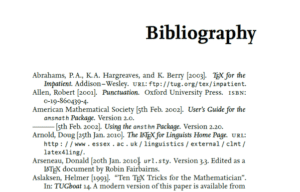

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and...

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is a research paper?

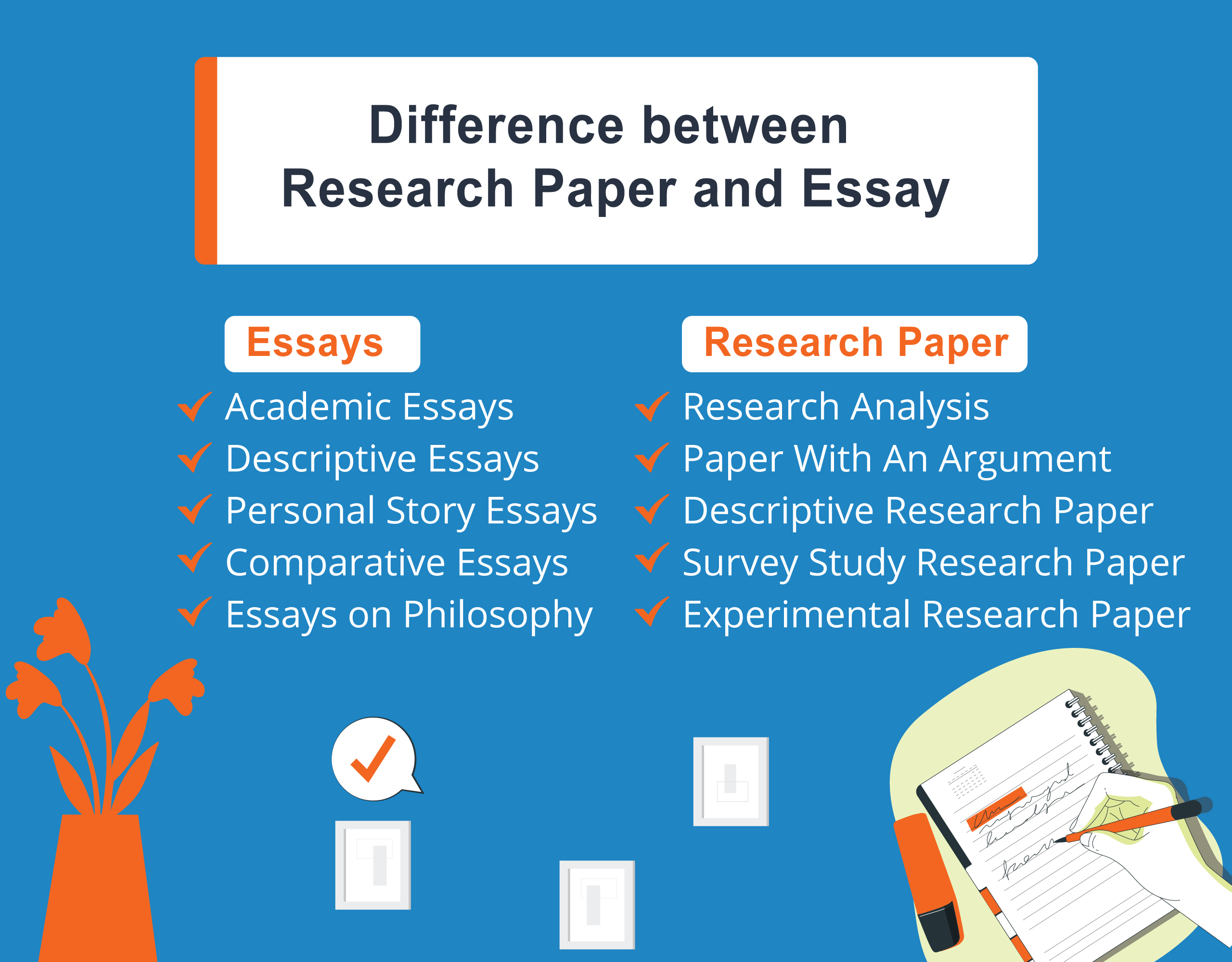

A research paper is a paper that makes an argument about a topic based on research and analysis.

Any paper requiring the writer to research a particular topic is a research paper. Unlike essays, which are often based largely on opinion and are written from the author's point of view, research papers are based in fact.

A research paper requires you to form an opinion on a topic, research and gain expert knowledge on that topic, and then back up your own opinions and assertions with facts found through your thorough research.

➡️ Read more about different types of research papers .

What is the difference between a research paper and a thesis?

A thesis is a large paper, or multi-chapter work, based on a topic relating to your field of study.

A thesis is a document students of higher education write to obtain an academic degree or qualification. Usually, it is longer than a research paper and takes multiple years to complete.

Generally associated with graduate/postgraduate studies, it is carried out under the supervision of a professor or other academic of the university.

A major difference between a research paper and a thesis is that:

- a research paper presents certain facts that have already been researched and explained by others

- a thesis starts with a certain scholarly question or statement, which then leads to further research and new findings

This means that a thesis requires the author to input original work and their own findings in a certain field, whereas the research paper can be completed with extensive research only.

➡️ Getting ready to start a research paper or thesis? Take a look at our guides on how to start a research paper or how to come up with a topic for your thesis .

Frequently Asked Questions about research papers

Take a look at this list of the top 21 Free Online Journal and Research Databases , such as ScienceOpen , Directory of Open Access Journals , ERIC , and many more.

Mason Porter, Professor at UCLA, explains in this forum post the main reasons to write a research paper:

- To create new knowledge and disseminate it.

- To teach science and how to write about it in an academic style.

- Some practical benefits: prestige, establishing credentials, requirements for grants or to help one get a future grant proposal, and so on.

Generally, people involved in the academia. Research papers are mostly written by higher education students and professional researchers.

Yes, a research paper is the same as a scientific paper. Both papers have the same purpose and format.

A major difference between a research paper and a thesis is that the former presents certain facts that have already been researched and explained by others, whereas the latter starts with a certain scholarly question or statement, which then leads to further research and new findings.

Related Articles

- Research Guides

BSCI 1510L Literature and Stats Guide: 3.2 Components of a scientific paper

- 1 What is a scientific paper?

- 2 Referencing and accessing papers

- 2.1 Literature Cited

- 2.2 Accessing Scientific Papers

- 2.3 Traversing the web of citations

- 2.4 Keyword Searches

- 3 Style of scientific writing

- 3.1 Specific details regarding scientific writing

3.2 Components of a scientific paper

- 4 Summary of the Writing Guide and Further Information

- Appendix A: Calculation Final Concentrations

- 1 Formulas in Excel

- 2 Basic operations in Excel

- 3 Measurement and Variation

- 3.1 Describing Quantities and Their Variation

- 3.2 Samples Versus Populations

- 3.3 Calculating Descriptive Statistics using Excel

- 4 Variation and differences

- 5 Differences in Experimental Science

- 5.1 Aside: Commuting to Nashville

- 5.2 P and Detecting Differences in Variable Quantities

- 5.3 Statistical significance

- 5.4 A test for differences of sample means: 95% Confidence Intervals

- 5.5 Error bars in figures

- 5.6 Discussing statistics in your scientific writing

- 6 Scatter plot, trendline, and linear regression

- 7 The t-test of Means

- 8 Paired t-test

- 9 Two-Tailed and One-Tailed Tests

- 10 Variation on t-tests: ANOVA

- 11 Reporting the Results of a Statistical Test

- 12 Summary of statistical tests

- 1 Objectives

- 2 Project timeline

- 3 Background

- 4 Previous work in the BSCI 111 class

- 5 General notes about the project

- 6 About the paper

- 7 References

Nearly all journal articles are divided into the following major sections: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references or literature cited. Usually the sections are labeled as such, although often the introduction (and sometimes the abstract) is not labeled. Sometimes alternative section titles are used. The abstract is sometimes called the "summary", the methods are sometimes called "materials and methods", and the discussion is sometimes called "conclusions". Some journals also include the minor sections of "key words" following the abstract, and "acknowledgments" following the discussion. In some journals, the sections may be divided into subsections that are given descriptive titles. However, the general division into the six major sections is nearly universal.

3.2.1 Abstract

The abstract is a short summary (150-200 words or less) of the important points of the paper. It does not generally include background information. There may be a very brief statement of the rationale for conducting the study. It describes what was done, but without details. It also describes the results in a summarized way that usually includes whether or not the statistical tests were significant. It usually concludes with a brief statement of the importance of the results. Abstracts do not include references. When writing a paper, the abstract is always the last part to be written.

The purpose of the abstract is to allow potential readers of a paper to find out the important points of the paper without having to actually read the paper. It should be a self-contained unit capable of being understood without the benefit of the text of the article . It essentially serves as an "advertisement" for the paper that readers use to determine whether or not they actually want to wade through the entire paper or not. Abstracts are generally freely available in electronic form and are often presented in the results of an electronic search. If searchers do not have electronic access to the journal in which the article is published, the abstract is the only means that they have to decide whether to go through the effort (going to the library to look up the paper journal, requesting a reprint from the author, buying a copy of the article from a service, requesting the article by Interlibrary Loan) of acquiring the article. Therefore it is important that the abstract accurately and succinctly presents the most important information in the article.

3.2.2 Introduction

The introduction section of a paper provides the background information necessary to understand why the described experiment was conducted. The introduction should describe previous research on the topic that has led to the unanswered questions being addressed by the experiment and should cite important previous papers that form the background for the experiment. The introduction should also state in an organized fashion the goals of the research, i.e. the particular, specific questions that will be tested in the experiments. There should be a one-to-one correspondence between questions raised in the introduction and points discussed in the conclusion section of the paper. In other words, do not raise questions in the introduction unless you are going to have some kind of answer to the question that you intend to discuss at the end of the paper.

You may have been told that every paper must have a hypothesis that can be clearly stated. That is often true, but not always. If your experiment involves a manipulation which tests a specific hypothesis, then you should clearly state that hypothesis. On the other hand, if your experiment was primarily exploratory, descriptive, or measurative, then you probably did not have an a priori hypothesis, so don't pretend that you did and make one up. (See the discussion in the introduction to Experiment 5 for more on this.) If you state a hypothesis in the introduction, it should be a general hypothesis and not a null or alternative hypothesis for a statistical test. If it is necessary to explain how a statistical test will help you evaluate your general hypothesis, explain that in the methods section.

A good introduction should be fairly heavy with citations. This indicates to the reader that the authors are informed about previous work on the topic and are not working in a vacuum. Citations also provide jumping-off points to allow the reader to explore other tangents to the subject that are not directly addressed in the paper. If the paper supports or refutes previous work, readers can look up the citations and make a comparison for themselves.

"Do not get lost in reviewing background information. Remember that the Introduction is meant to introduce the reader to your research, not summarize and evaluate all past literature on the subject (which is the purpose of a review paper). Many of the other studies you may be tempted to discuss in your Introduction are better saved for the Discussion, where they become a powerful tool for comparing and interpreting your results. Include only enough background information to allow your reader to understand why you are asking the questions you are and why your hypotheses are reasonable ones. Often, a brief explanation of the theory involved is sufficient.

Write this section in the past or present tense, never in the future. " (Steingraber et al. 1985)

In other words, the introduction section relates what the topic being investigated is, why it is important, what research (if any) has been done prior that is relevant to what you are trying to do, and in what ways you will be looking into this topic.

An example to think about:

This is an example of a student-derived introduction. Read the paragraph and before you go beyond, think about the paragraph first.

"Hand-washing is one of the most effective and simplest of ways to reduce infection and disease, and thereby causing less death. When examining the effects of soap on hands, it was the work of Sickbert-Bennett and colleagues (2005) that showed that using soap or an alcohol on the hands during hand-washing was a significant effect in removing bacteria from the human hand. Based on the work of this, the team led by Larsen (1991) then showed that the use of computer imaging could be a more effective way to compare the amount of bacteria on a hand."

There are several aspects within this "introduction" that could use improvement. A group of any random 4 of you could easily come up with at 10 different things to reword, revise, expand upon.

In specific, there should be one thing addressed that more than likely you did not catch when you were reading it.

The citations: Not the format, but the logical use of them.

Look again. "...the work of Sickbert-Bennett...(2005)" and then "Based on the work of this, the team led by Larsen (1991)..."

How can someone in 1991 use or base their work on something from 2005?

They cannot. You can spend an entire hour using spellcheck and reading through and through again to find all the little things to "give it more oomph", but at the core, you still must present a clear and concise and logical thought-process.

3.2.3 Methods (taken mostly verbatim from Steingraber et al. 1985, until the version A, B,C portion)

The function of the methods section is to describe all experimental procedures, including controls. The description should be complete enough to enable someone else to repeat your work. If there is more than one part to the experiment, it is a good idea to describe your methods and present your results in the same order in each section. This may not be the same order in which the experiments were performed -it is up to you to decide what order of presentation will make the most sense to your reader.

1. Explain why each procedure was done, i.e., what variable were you measuring and why? Example:

Difficult to understand : First, I removed the frog muscle and then I poured Ringer’s solution on it. Next, I attached it to the kymograph.

Improved: I removed the frog muscle and poured Ringer’s solution on it to prevent it from drying out. I then attached the muscle to the kymograph in order to determine the minimum voltage required for contraction.

Better: Frog muscle was excised between attachment points to the bone. Ringer's solution was added to the excised section to prevent drying out. The muscle was attached to the kymograph in order to determine the minimum voltage required for contraction.

2. Experimental procedures and results are narrated in the past tense (what you did, what you found, etc.) whereas conclusions from your results are given in the present tense.

3. Mathematical equations and statistical tests are considered mathematical methods and should be described in this section along with the actual experimental work. (Show a sample calculation, state the type of test(s) performed and program used)

4. Use active rather than passive voice when possible. [Note: see Section 3.1.4 for more about this.] Always use the singular "I" rather than the plural "we" when you are the only author of the paper (Methods section only). Throughout the paper, avoid contractions, e.g. did not vs. didn’t.

5. If any of your methods is fully described in a previous publication (yours or someone else’s), you can cite work that instead of describing the procedure again.

Example: The chromosomes were counted at meiosis in the anthers with the standard acetocarmine technique of Snow (1955).

Below is a PARTIAL and incomplete version of a "method". Without getting into the details of why, Version A and B are bad. A is missing too many details and B is giving some extra details but not giving some important ones, such as the volumes used. Version C is still not complete, but it is at least a viable method. Notice that C is also not the longest....it is possible to be detailed without being long-winded.

In other words, the methods section is what you did in the experiment and has enough details that someone else can repeat your experiment. If the methods section has excluded one or more important detail(s) such that the reader of the method does not know what happened, it is a 'poor' methods section. Similarly, by giving out too many useless details a methods section can be 'poor'.

You may have multiple sub-sections within your methods (i.e., a section for media preparation, a section for where the chemicals came from, a section for the basic physical process that occurred, etc.,). A methods section is NEVER a list of numbered steps.

3.2.4 Results (with excerpts from Steingraber et al. 1985)

The function of this section is to summarize general trends in the data without comment, bias, or interpretation. The results of statistical tests applied to your data are reported in this section although conclusions about your original hypotheses are saved for the Discussion section. In other words, you state "the P-value" in Results and whether below/above 0.05 and thus significant/not significant while in the Discussion you restate the P-value and then formally state what that means beyond "significant/not significant".

Tables and figures should be used when they are a more efficient way to convey information than verbal description. They must be independent units, accompanied by explanatory captions that allow them to be understood by someone who has not read the text. Do not repeat in the text the information in tables and figures, but do cite them, with a summary statement when that is appropriate. Example:

Incorrect: The results are given in Figure 1.

Correct: Temperature was directly proportional to metabolic rate (Fig. 1).

Please note that the entire word "Figure" is almost never written in an article. It is nearly always abbreviated as "Fig." and capitalized. Tables are cited in the same way, although Table is not abbreviated.

Whenever possible, use a figure instead of a table. Relationships between numbers are more readily grasped when they are presented graphically rather than as columns in a table.

Data may be presented in figures and tables, but this may not substitute for a verbal summary of the findings. The text should be understandable by someone who has not seen your figures and tables.

1. All results should be presented, including those that do not support the hypothesis.

2. Statements made in the text must be supported by the results contained in figures and tables.

3. The results of statistical tests can be presented in parentheses following a verbal description.

Example: Fruit size was significantly greater in trees growing alone (t = 3.65, df = 2, p < 0.05).

Simple results of statistical tests may be reported in the text as shown in the preceding example. The results of multiple tests may be reported in a table if that increases clarity. (See Section 11 of the Statistics Manual for more details about reporting the results of statistical tests.) It is not necessary to provide a citation for a simple t-test of means, paired t-test, or linear regression. If you use other more complex (or less well-known) tests, you should cite the text or reference you followed to do the test. In your materials and methods section, you should report how you did the test (e.g. using the statistical analysis package of Excel).

It is NEVER appropriate to simply paste the results from statistical software into the results section of your paper. The output generally reports more information than is required and it is not in an appropriate format for a paper. Similar, do NOT place a screenshot.

Should you include every data point or not in the paper? Prior to 2010 or so, most papers would probably not present the actual raw data collected, but rather show the "descriptive statistics" about their data (mean, SD, SE, CI, etc.). Often, people could simply contact the author(s) for the data and go from there. As many journals have a significant on-line footprint now, it has become increasingly more common that the entire data could be included in the paper. And realize why the entire raw data may not have been included in a publication. Prior to about 2010, your publication had limited paper space to be seen on. If you have a sample of size of 10 or 50, you probably could show the entire data set easily in one table/figure and it not take up too much printed space. If your sample size was 500 or 5,000 or more, the size of the data alone would take pages of printed text. Given how much the Internet and on-line publications have improved/increased in storage space, often now there will be either an embedded file to access or the author(s) will place the file on-line somewhere with an address link, such as GitHub. Videos of the experiment are also shown as well now.

3.2.4.1 Tables

- Do not repeat information in a table that you are depicting in a graph or histogram; include a table only if it presents new information.

- It is easier to compare numbers by reading down a column rather than across a row. Therefore, list sets of data you want your reader to compare in vertical form.

- Provide each table with a number (Table 1, Table 2, etc.) and a title. The numbered title is placed above the table .

- Please see Section 11 of the Excel Reference and Statistics Manual for further information on reporting the results of statistical tests.

3.2.4.2. Figures

- These comprise graphs, histograms, and illustrations, both drawings and photographs. Provide each figure with a number (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, etc.) and a caption (or "legend") that explains what the figure shows. The numbered caption is placed below the figure . Figure legend = Figure caption.

- Figures submitted for publication must be "photo ready," i.e., they will appear just as you submit them, or photographically reduced. Therefore, when you graduate from student papers to publishable manuscripts, you must learn to prepare figures that will not embarrass you. At the present time, virtually all journals require manuscripts to be submitted electronically and it is generally assumed that all graphs and maps will be created using software rather than being created by hand. Nearly all journals have specific guidelines for the file types, resolution, and physical widths required for figures. Only in a few cases (e.g. sketched diagrams) would figures still be created by hand using ink and those figures would be scanned and labeled using graphics software. Proportions must be the same as those of the page in the journal to which the paper will be submitted.

- Graphs and Histograms: Both can be used to compare two variables. However, graphs show continuous change, whereas histograms show discrete variables only. You can compare groups of data by plotting two or even three lines on one graph, but avoid cluttered graphs that are hard to read, and do not plot unrelated trends on the same graph. For both graphs, and histograms, plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. Label both axes, including units of measurement except in the few cases where variables are unitless, such as absorbance.

- Drawings and Photographs: These are used to illustrate organisms, experimental apparatus, models of structures, cellular and subcellular structure, and results of procedures like electrophoresis. Preparing such figures well is a lot of work and can be very expensive, so each figure must add enough to justify its preparation and publication, but good figures can greatly enhance a professional article, as your reading in biological journals has already shown.

3.2.5 Discussion (modified; taken from Steingraber et al. 1985)

The function of this section is to analyze the data and relate them to other studies. To "analyze" means to evaluate the meaning of your results in terms of the original question or hypothesis and point out their biological significance.

1. The Discussion should contain at least:

- the relationship between the results and the original hypothesis, i.e., whether they support the hypothesis, or cause it to be rejected or modified

- an integration of your results with those of previous studies in order to arrive at explanations for the observed phenomena

- possible explanations for unexpected results and observations, phrased as hypotheses that can be tested by realistic experimental procedures, which you should describe

2. Trends that are not statistically significant can still be discussed if they are suggestive or interesting, but cannot be made the basis for conclusions as if they were significant.

3. Avoid redundancy between the Results and the Discussion section. Do not repeat detailed descriptions of the data and results in the Discussion. In some journals, Results and Discussions are joined in a single section, in order to permit a single integrated treatment with minimal repetition. This is more appropriate for short, simple articles than for longer, more complicated ones.

4. End the Discussion with a summary of the principal points you want the reader to remember. This is also the appropriate place to propose specific further study if that will serve some purpose, but do not end with the tired cliché that "this problem needs more study." All problems in biology need more study. Do not close on what you wish you had done, rather finish stating your conclusions and contributions.

5. Conclusion section. Primarily dependent upon the complexity and depth of an experiment, there may be a formal conclusion section after the discussion section. In general, the last line or so of the discussion section should be a more or less summary statement of the overall finding of the experiment. IF the experiment was large enough/complex enough/multiple findings uncovered, a distinct paragraph (or two) may be needed to help clarify the findings. Again, only if the experiment scale/findings warrant a separate conclusion section.

3.2.6 Title

The title of the paper should be the last thing that you write. That is because it should distill the essence of the paper even more than the abstract (the next to last thing that you write).

The title should contain three elements:

1. the name of the organism studied;

2. the particular aspect or system studied;

3. the variable(s) manipulated.

Do not be afraid to be grammatically creative. Here are some variations on a theme, all suitable as titles:

THE EFFECT OF TEMPERATURE ON GERMINATION OF ZEA MAYS

DOES TEMPERATURE AFFECT GERMINATION OF ZEA MAYS?

TEMPERATURE AND ZEA MAYS GERMINATION: IMPLICATIONS FOR AGRICULTURE

Sometimes it is possible to include the principal result or conclusion in the title:

HIGH TEMPERATURES REDUCE GERMINATION OF ZEA MAYS

Note for the BSCI 1510L class: to make your paper look more like a real paper, you can list all of the other group members as co-authors. However, if you do that, you should list you name first so that we know that you wrote it.

3.2.7 Literature Cited

Please refer to section 2.1 of this guide.

- << Previous: 3.1 Specific details regarding scientific writing

- Next: 4 Summary of the Writing Guide and Further Information >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/bsci1510L

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

What Is a Research Paper?

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Olivia Valdes was the Associate Editorial Director for ThoughtCo. She worked with Dotdash Meredith from 2017 to 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Olivia-Valdes_WEB1-1e405fc799d9474e9212215c4f21b141.jpg)

- B.A., American Studies, Yale University

A research paper is a common form of academic writing . Research papers require students and academics to locate information about a topic (that is, to conduct research ), take a stand on that topic, and provide support (or evidence) for that position in an organized report.

The term research paper may also refer to a scholarly article that contains the results of original research or an evaluation of research conducted by others. Most scholarly articles must undergo a process of peer review before they can be accepted for publication in an academic journal.

Define Your Research Question

The first step in writing a research paper is defining your research question . Has your instructor assigned a specific topic? If so, great—you've got this step covered. If not, review the guidelines of the assignment. Your instructor has likely provided several general subjects for your consideration. Your research paper should focus on a specific angle on one of these subjects. Spend some time mulling over your options before deciding which one you'd like to explore more deeply.

Try to choose a research question that interests you. The research process is time-consuming, and you'll be significantly more motivated if you have a genuine desire to learn more about the topic. You should also consider whether you have access to all of the resources necessary to conduct thorough research on your topic, such as primary and secondary sources .

Create a Research Strategy

Approach the research process systematically by creating a research strategy. First, review your library's website. What resources are available? Where will you find them? Do any resources require a special process to gain access? Start gathering those resources—especially those that may be difficult to access—as soon as possible.

Second, make an appointment with a reference librarian . A reference librarian is nothing short of a research superhero. He or she will listen to your research question, offer suggestions for how to focus your research, and direct you toward valuable sources that directly relate to your topic.

Evaluate Sources

Now that you've gathered a wide array of sources, it's time to evaluate them. First, consider the reliability of the information. Where is the information coming from? What is the origin of the source? Second, assess the relevance of the information. How does this information relate to your research question? Does it support, refute, or add context to your position? How does it relate to the other sources you'll be using in your paper? Once you have determined that your sources are both reliable and relevant, you can proceed confidently to the writing phase.

Why Write Research Papers?

The research process is one of the most taxing academic tasks you'll be asked to complete. Luckily, the value of writing a research paper goes beyond that A+ you hope to receive. Here are just some of the benefits of research papers.

- Learning Scholarly Conventions: Writing a research paper is a crash course in the stylistic conventions of scholarly writing. During the research and writing process, you'll learn how to document your research, cite sources appropriately, format an academic paper, maintain an academic tone, and more.

- Organizing Information: In a way, research is nothing more than a massive organizational project. The information available to you is near-infinite, and it's your job to review that information, narrow it down, categorize it, and present it in a clear, relevant format. This process requires attention to detail and major brainpower.

- Managing Time: Research papers put your time management skills to the test. Every step of the research and writing process takes time, and it's up to you to set aside the time you'll need to complete each step of the task. Maximize your efficiency by creating a research schedule and inserting blocks of "research time" into your calendar as soon as you receive the assignment.

- Exploring Your Chosen Subject: We couldn't forget the best part of research papers—learning about something that truly excites you. No matter what topic you choose, you're bound to come away from the research process with new ideas and countless nuggets of fascinating information.

The best research papers are the result of genuine interest and a thorough research process. With these ideas in mind, go forth and research. Welcome to the scholarly conversation!

- Documentation in Reports and Research Papers

- Thesis: Definition and Examples in Composition

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- How to Use Footnotes in Research Papers

- How to Write an Abstract

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- How to Take Better Notes During Lectures, Discussions, and Interviews

- What Is a Literature Review?

- Research in Essays and Reports

- Topic In Composition and Speech

- Focusing in Composition

- What Is a Citation?

- What Are Endnotes, Why Are They Needed, and How Are They Used?

- What Is Plagiarism?

- Definition of Appendix in a Book or Written Work

)

How to write a research paper: A step-by-step guide

Published July 20, 2020. Updated May 19, 2022.

Research Paper Definition

A research paper is an essay that evaluates or argues a perception or a point.

Overview of research paper

Research papers are papers written as in-depth analyses of the academic literature on a selected topic. A research paper outline consists of planning out the main sections of the paper, including the points and evidence, so that the drafting and editing processes are much easier. The research paper should have an introduction paragraph, at least three body paragraphs, a conclusion paragraph, and a Works Cited page. Some important steps should be followed while writing a research paper. The steps include understanding the instructor’s expectations for how to write a research paper, brainstorming research paper ideas, conducting research, defining the thesis statement, making a research paper outline, writing, editing again if required, creating a title page, and writing an abstract.

Key takeaways

- A research paper is an essay that analyzes or argues a perspective or a point.

- A research paper outline involves planning out the main sections of your paper, including your points and evidence, so that the drafting and editing processes go a lot smoother.

- Before you write your research paper outline, consult your instructor, research potential topics, and define your thesis statement.

- Your research paper should include an introduction paragraph, at least three body paragraphs, a conclusion paragraph, and a Works Cited page.

What are the steps to writing a research paper?

Here are 7 steps on how to write a research paper, plus two optional steps on creating a title page and an abstract:

Step 1: Understand your instructor’s expectations for how to write a research paper

Step 2: brainstorm research paper ideas, step 3: conduct research, step 4: define your thesis statement, step 5: make a research paper outline, step 6: write, step 7: edit, edit, and edit again, step 8 (optional): create a title page, step 9 (optional): write an abstract.

- Additional tips

Worried about your writing? Submit your paper for a Chegg Writing essay check , or for an Expert Check proofreading . Both can help you find and fix potential writing issues.

First, read and reread the rubric for the assignment. Depending on your field of study, the guidelines will vary. For instance, psychology, education, and the sciences tend to use APA research paper format, while the humanities, language, and the fine arts tend to use MLA or Chicago style.

Once you know which research paper format to use, take heed of any specific expectations your instructor has for this assignment. For example:

- When is it due?

- What is the expected page count?

- Will your instructor expect to see a research paper outline before the draft?

- Is there a set topic list or can you choose your own?

- Is there someplace to look at sample research papers that got A’s?

If anything isn’t clear about how to write a research paper, don’t hesitate to ask your instructor.

Being aware of the assignment’s details is a good start! However, even after reading them, you may still be asking some of the following questions:

- How do you think of topics for research papers?

- How do you think of interesting research paper topics?

- How do I structure an outline?

- Where can you find examples of research papers?

We’ll answer all of these questions (and more) in the steps below.

Some instructors offer a set of research paper topics to choose from. That makes it easy for you—just pick the research paper idea that intrigues you the most! Since all the topics have been approved by your instructor, you shouldn’t have to worry about any of them being too “broad” or “narrow.” (But remember, there are no easy research paper topics!)

On the other hand, many instructors expect students to brainstorm their own topics for research papers. In this case, you will need to ensure your topic is relevant as well as not too broad or narrow.

An example of a research paper topic that is too broad is “The History of Modernist Literature.” An expert would be hard-pressed to write a book on this topic, much less a school essay.

An example of a research paper topic that is too narrow is “Why the First Line of Ulysses Exemplifies Modernist Literature.” It may take a page or two to outline the ways in which the first line of Ulysses exemplifies traits of modernist literature, but there’s only so much you can write about one line!

Good research paper topics fall somewhere in the middle . An example of this would be “Why Ulysses ’ Stephen Exemplifies Modernist Literature.” Analyzing a character in a novel is broader than analyzing a single line, but it is narrower than examining an entire literary movement.

Next, conduct research and use an adequate number of reputable sources to back up your argument or analysis. This means that you need to evaluate the credibility of all your sources and probably include a few peer-reviewed journal articles (tip: use a database).

A lot of good sources can be found online or at your school’s library (in-person and online). If you’re stuck finding sources or would like to see a sample research paper, ask your librarian for help. If you’re having trouble finding useful sources, it may be a warning sign that your idea is too broad or narrow. For a more comprehensive look at research, check this out .

Your thesis statement is the most important line of your research paper! It encompasses in one sentence what your paper is all about. Having a concrete thesis statement will help you organize your thoughts around a defined point, and it will help your readers understand what they’re reading about.

If you could boil your paper down into a single line, what would that line be?

Here is an example of a working thesis:

In George Orwell’s 1984 , the Party manipulates citizens into total submission to the Party’s ideals through Newspeak, propaganda, and altered history.

For more information, see this guide on thesis statements .

Even if you think you chose an easy research paper topic, a structured, outlined research paper format is still necessary to help you stay organized and on-track while you draft. The traditional research paper outline example looks something like this:

Introduction

- Main point #1

- Main point #2

- Main point #3

Works cited

Let’s examine each section in detail.

Wondering how to start a research paper that gets an A? One good step is to have a strong introduction. Your research paper introduction will include the following elements:

- state your thesis (the one or two-line gist of your paper)

- explain the question you will answer or argument you will make

- outline your research methodology

1. Open with a hook

Keep your readers reading—hook them! A handy tip for writing a hook is to think about what made you choose this topic. What about your topic captured your interest enough to research it and write a paper about it?

A hook might sound something like the following examples:

Did you know that babies have around a hundred more bones than adults?

A language dies every fourteen days.

Of course, by no means does your opening line have to be so shocking. It could be as simple as you’d like, as long as it pulls your readers in and gives them an idea of what your paper is going to be about.

2. Introduce relevant background context

After you’ve hooked your readers, introduce them to the topic at hand. What is already known about it? What is still a mystery? Why should we care? Finally, what work have you done to advance knowledge on this topic?

You can include a relevant quotation or paraphrase here, but keep it short and sweet. Your introduction should not be bogged down with anything less than essential.

3. End on your thesis statement

Finally, end your introduction paragraph with your thesis statement, which is a concise sentence (just one, two max) summarizing the crux of your research paper.

Research paper introduction example

As John Wilkes Booth fled the scene of his assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, he yelled, “ Sic semper tyrannis ! The South is avenged!” Booth was an ardent supporter of the Southern cause during the Civil War era, but what made him passionate enough to assassinate a sitting president? Although Booth’s ire can be traced mostly to his backing of the South, there is more to the story than just that. John Wilkes Booth had three primary motives for assassinating Abraham Lincoln.

The body of your paper is not limited to three points, as shown below, but three is typically considered the minimum. A good rule of thumb is to back up each main point with three arguments or pieces of evidence. To present a cogent argument or make your analysis more compelling , present your points and arguments in a “strong, stronger, strongest” research paper format.

- Main point #1 – A strong point

- Strong supporting argument or evidence #1

- Stronger supporting argument or evidence #2

- Strongest supporting argument or evidence #3

- Main point #2 – A stronger point

- Main point #3 – Your strongest point

The conclusion is crucial for helping your readers reflect on your main arguments or analyses and understand why what they just read was worthwhile.

- restate your topic

- synthesize your most important points

- restate your thesis statement

- tie it all into the bigger picture

1. Restate your topic

Before you wrap up your paper, it helps to remind your readers of the main idea at hand. This is different than restating your thesis. While your thesis states the specific argument or analysis at hand, the main idea of your research paper might be much broader. For instance, your thesis statement might be “John Wilkes Booth had three primary motives for assassinating Abraham Lincoln.” The main idea of the paper is Booth’s assassination of Lincoln. Even broader, the research paper is about American history.

2. Synthesize your most important points