Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

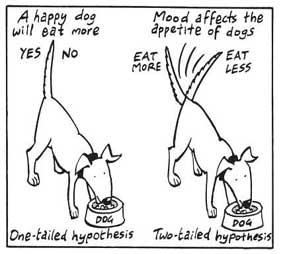

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

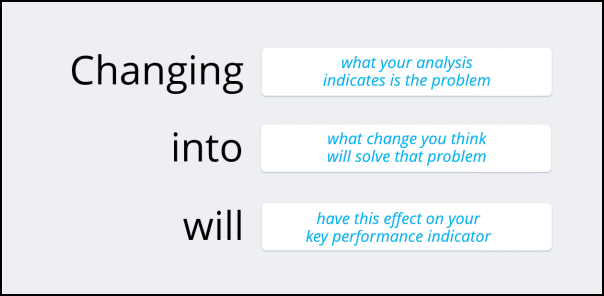

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

User Preferences

Content preview.

Arcu felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis:

- Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

- Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate

- Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident

Keyboard Shortcuts

5.2 - writing hypotheses.

The first step in conducting a hypothesis test is to write the hypothesis statements that are going to be tested. For each test you will have a null hypothesis (\(H_0\)) and an alternative hypothesis (\(H_a\)).

When writing hypotheses there are three things that we need to know: (1) the parameter that we are testing (2) the direction of the test (non-directional, right-tailed or left-tailed), and (3) the value of the hypothesized parameter.

- At this point we can write hypotheses for a single mean (\(\mu\)), paired means(\(\mu_d\)), a single proportion (\(p\)), the difference between two independent means (\(\mu_1-\mu_2\)), the difference between two proportions (\(p_1-p_2\)), a simple linear regression slope (\(\beta\)), and a correlation (\(\rho\)).

- The research question will give us the information necessary to determine if the test is two-tailed (e.g., "different from," "not equal to"), right-tailed (e.g., "greater than," "more than"), or left-tailed (e.g., "less than," "fewer than").

- The research question will also give us the hypothesized parameter value. This is the number that goes in the hypothesis statements (i.e., \(\mu_0\) and \(p_0\)). For the difference between two groups, regression, and correlation, this value is typically 0.

Hypotheses are always written in terms of population parameters (e.g., \(p\) and \(\mu\)). The tables below display all of the possible hypotheses for the parameters that we have learned thus far. Note that the null hypothesis always includes the equality (i.e., =).

| Research Question | Is the population mean different from \( \mu_{0} \)? | Is the population mean greater than \(\mu_{0}\)? | Is the population mean less than \(\mu_{0}\)? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(\mu=\mu_{0} \) | \(\mu=\mu_{0} \) | \(\mu=\mu_{0} \) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(\mu\neq \mu_{0} \) | \(\mu> \mu_{0} \) | \(\mu<\mu_{0} \) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

| Research Question | Is there a difference in the population? | Is there a mean increase in the population? | Is there a mean decrease in the population? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(\mu_d=0 \) | \(\mu_d =0 \) | \(\mu_d=0 \) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(\mu_d \neq 0 \) | \(\mu_d> 0 \) | \(\mu_d<0 \) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

| Research Question | Is the population proportion different from \(p_0\)? | Is the population proportion greater than \(p_0\)? | Is the population proportion less than \(p_0\)? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(p=p_0\) | \(p= p_0\) | \(p= p_0\) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(p\neq p_0\) | \(p> p_0\) | \(p< p_0\) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

| Research Question | Are the population means different? | Is the population mean in group 1 greater than the population mean in group 2? | Is the population mean in group 1 less than the population mean in groups 2? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(\mu_1=\mu_2\) | \(\mu_1 = \mu_2 \) | \(\mu_1 = \mu_2 \) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(\mu_1 \ne \mu_2 \) | \(\mu_1 \gt \mu_2 \) | \(\mu_1 \lt \mu_2\) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

| Research Question | Are the population proportions different? | Is the population proportion in group 1 greater than the population proportion in groups 2? | Is the population proportion in group 1 less than the population proportion in group 2? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(p_1 = p_2 \) | \(p_1 = p_2 \) | \(p_1 = p_2 \) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(p_1 \ne p_2\) | \(p_1 \gt p_2 \) | \(p_1 \lt p_2\) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

| Research Question | Is the slope in the population different from 0? | Is the slope in the population positive? | Is the slope in the population negative? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(\beta =0\) | \(\beta= 0\) | \(\beta = 0\) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(\beta\neq 0\) | \(\beta> 0\) | \(\beta< 0\) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

| Research Question | Is the correlation in the population different from 0? | Is the correlation in the population positive? | Is the correlation in the population negative? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis, \(H_{0}\) | \(\rho=0\) | \(\rho= 0\) | \(\rho = 0\) |

| Alternative Hypothesis, \(H_{a}\) | \(\rho \neq 0\) | \(\rho > 0\) | \(\rho< 0\) |

| Type of Hypothesis Test | Two-tailed, non-directional | Right-tailed, directional | Left-tailed, directional |

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples

Published on November 8, 2019 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics . It is most often used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses, that arise from theories.

There are 5 main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis as a null hypothesis and alternate hypothesis (H o ) and (H a or H 1 ).

- Collect data in a way designed to test the hypothesis.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test .

- Decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

- Present the findings in your results and discussion section.

Though the specific details might vary, the procedure you will use when testing a hypothesis will always follow some version of these steps.

Table of contents

Step 1: state your null and alternate hypothesis, step 2: collect data, step 3: perform a statistical test, step 4: decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis, step 5: present your findings, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about hypothesis testing.

After developing your initial research hypothesis (the prediction that you want to investigate), it is important to restate it as a null (H o ) and alternate (H a ) hypothesis so that you can test it mathematically.

The alternate hypothesis is usually your initial hypothesis that predicts a relationship between variables. The null hypothesis is a prediction of no relationship between the variables you are interested in.

- H 0 : Men are, on average, not taller than women. H a : Men are, on average, taller than women.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

For a statistical test to be valid , it is important to perform sampling and collect data in a way that is designed to test your hypothesis. If your data are not representative, then you cannot make statistical inferences about the population you are interested in.

There are a variety of statistical tests available, but they are all based on the comparison of within-group variance (how spread out the data is within a category) versus between-group variance (how different the categories are from one another).

If the between-group variance is large enough that there is little or no overlap between groups, then your statistical test will reflect that by showing a low p -value . This means it is unlikely that the differences between these groups came about by chance.

Alternatively, if there is high within-group variance and low between-group variance, then your statistical test will reflect that with a high p -value. This means it is likely that any difference you measure between groups is due to chance.

Your choice of statistical test will be based on the type of variables and the level of measurement of your collected data .

- an estimate of the difference in average height between the two groups.

- a p -value showing how likely you are to see this difference if the null hypothesis of no difference is true.

Based on the outcome of your statistical test, you will have to decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

In most cases you will use the p -value generated by your statistical test to guide your decision. And in most cases, your predetermined level of significance for rejecting the null hypothesis will be 0.05 – that is, when there is a less than 5% chance that you would see these results if the null hypothesis were true.

In some cases, researchers choose a more conservative level of significance, such as 0.01 (1%). This minimizes the risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis ( Type I error ).

The results of hypothesis testing will be presented in the results and discussion sections of your research paper , dissertation or thesis .

In the results section you should give a brief summary of the data and a summary of the results of your statistical test (for example, the estimated difference between group means and associated p -value). In the discussion , you can discuss whether your initial hypothesis was supported by your results or not.

In the formal language of hypothesis testing, we talk about rejecting or failing to reject the null hypothesis. You will probably be asked to do this in your statistics assignments.

However, when presenting research results in academic papers we rarely talk this way. Instead, we go back to our alternate hypothesis (in this case, the hypothesis that men are on average taller than women) and state whether the result of our test did or did not support the alternate hypothesis.

If your null hypothesis was rejected, this result is interpreted as “supported the alternate hypothesis.”

These are superficial differences; you can see that they mean the same thing.

You might notice that we don’t say that we reject or fail to reject the alternate hypothesis . This is because hypothesis testing is not designed to prove or disprove anything. It is only designed to test whether a pattern we measure could have arisen spuriously, or by chance.

If we reject the null hypothesis based on our research (i.e., we find that it is unlikely that the pattern arose by chance), then we can say our test lends support to our hypothesis . But if the pattern does not pass our decision rule, meaning that it could have arisen by chance, then we say the test is inconsistent with our hypothesis .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bevans, R. (2023, June 22). Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/hypothesis-testing/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

Other students also liked, choosing the right statistical test | types & examples, understanding p values | definition and examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is secondary school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout secondary school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy than teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | Secondary school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative correlation between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of hypothesis

Did you know.

The Difference Between Hypothesis and Theory

A hypothesis is an assumption, an idea that is proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested to see if it might be true.

In the scientific method, the hypothesis is constructed before any applicable research has been done, apart from a basic background review. You ask a question, read up on what has been studied before, and then form a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is usually tentative; it's an assumption or suggestion made strictly for the objective of being tested.

A theory , in contrast, is a principle that has been formed as an attempt to explain things that have already been substantiated by data. It is used in the names of a number of principles accepted in the scientific community, such as the Big Bang Theory . Because of the rigors of experimentation and control, it is understood to be more likely to be true than a hypothesis is.

In non-scientific use, however, hypothesis and theory are often used interchangeably to mean simply an idea, speculation, or hunch, with theory being the more common choice.

Since this casual use does away with the distinctions upheld by the scientific community, hypothesis and theory are prone to being wrongly interpreted even when they are encountered in scientific contexts—or at least, contexts that allude to scientific study without making the critical distinction that scientists employ when weighing hypotheses and theories.

The most common occurrence is when theory is interpreted—and sometimes even gleefully seized upon—to mean something having less truth value than other scientific principles. (The word law applies to principles so firmly established that they are almost never questioned, such as the law of gravity.)

This mistake is one of projection: since we use theory in general to mean something lightly speculated, then it's implied that scientists must be talking about the same level of uncertainty when they use theory to refer to their well-tested and reasoned principles.

The distinction has come to the forefront particularly on occasions when the content of science curricula in schools has been challenged—notably, when a school board in Georgia put stickers on textbooks stating that evolution was "a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things." As Kenneth R. Miller, a cell biologist at Brown University, has said , a theory "doesn’t mean a hunch or a guess. A theory is a system of explanations that ties together a whole bunch of facts. It not only explains those facts, but predicts what you ought to find from other observations and experiments.”

While theories are never completely infallible, they form the basis of scientific reasoning because, as Miller said "to the best of our ability, we’ve tested them, and they’ve held up."

- proposition

- supposition

hypothesis , theory , law mean a formula derived by inference from scientific data that explains a principle operating in nature.

hypothesis implies insufficient evidence to provide more than a tentative explanation.

theory implies a greater range of evidence and greater likelihood of truth.

law implies a statement of order and relation in nature that has been found to be invariable under the same conditions.

Examples of hypothesis in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'hypothesis.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Greek, from hypotithenai to put under, suppose, from hypo- + tithenai to put — more at do

1641, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

Phrases Containing hypothesis

- counter - hypothesis

- nebular hypothesis

- null hypothesis

- planetesimal hypothesis

- Whorfian hypothesis

Articles Related to hypothesis

This is the Difference Between a...

This is the Difference Between a Hypothesis and a Theory

In scientific reasoning, they're two completely different things

Dictionary Entries Near hypothesis

hypothermia

hypothesize

Cite this Entry

“Hypothesis.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hypothesis. Accessed 24 Aug. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of hypothesis, medical definition, medical definition of hypothesis, more from merriam-webster on hypothesis.

Nglish: Translation of hypothesis for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of hypothesis for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about hypothesis

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Statistical Hypothesis Testing Overview

By Jim Frost 59 Comments

In this blog post, I explain why you need to use statistical hypothesis testing and help you navigate the essential terminology. Hypothesis testing is a crucial procedure to perform when you want to make inferences about a population using a random sample. These inferences include estimating population properties such as the mean, differences between means, proportions, and the relationships between variables.

This post provides an overview of statistical hypothesis testing. If you need to perform hypothesis tests, consider getting my book, Hypothesis Testing: An Intuitive Guide .

Why You Should Perform Statistical Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a form of inferential statistics that allows us to draw conclusions about an entire population based on a representative sample. You gain tremendous benefits by working with a sample. In most cases, it is simply impossible to observe the entire population to understand its properties. The only alternative is to collect a random sample and then use statistics to analyze it.

While samples are much more practical and less expensive to work with, there are trade-offs. When you estimate the properties of a population from a sample, the sample statistics are unlikely to equal the actual population value exactly. For instance, your sample mean is unlikely to equal the population mean. The difference between the sample statistic and the population value is the sample error.

Differences that researchers observe in samples might be due to sampling error rather than representing a true effect at the population level. If sampling error causes the observed difference, the next time someone performs the same experiment the results might be different. Hypothesis testing incorporates estimates of the sampling error to help you make the correct decision. Learn more about Sampling Error .

For example, if you are studying the proportion of defects produced by two manufacturing methods, any difference you observe between the two sample proportions might be sample error rather than a true difference. If the difference does not exist at the population level, you won’t obtain the benefits that you expect based on the sample statistics. That can be a costly mistake!

Let’s cover some basic hypothesis testing terms that you need to know.

Background information : Difference between Descriptive and Inferential Statistics and Populations, Parameters, and Samples in Inferential Statistics

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a statistical analysis that uses sample data to assess two mutually exclusive theories about the properties of a population. Statisticians call these theories the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis. A hypothesis test assesses your sample statistic and factors in an estimate of the sample error to determine which hypothesis the data support.

When you can reject the null hypothesis, the results are statistically significant, and your data support the theory that an effect exists at the population level.

The effect is the difference between the population value and the null hypothesis value. The effect is also known as population effect or the difference. For example, the mean difference between the health outcome for a treatment group and a control group is the effect.

Typically, you do not know the size of the actual effect. However, you can use a hypothesis test to help you determine whether an effect exists and to estimate its size. Hypothesis tests convert your sample effect into a test statistic, which it evaluates for statistical significance. Learn more about Test Statistics .

An effect can be statistically significant, but that doesn’t necessarily indicate that it is important in a real-world, practical sense. For more information, read my post about Statistical vs. Practical Significance .

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is one of two mutually exclusive theories about the properties of the population in hypothesis testing. Typically, the null hypothesis states that there is no effect (i.e., the effect size equals zero). The null is often signified by H 0 .

In all hypothesis testing, the researchers are testing an effect of some sort. The effect can be the effectiveness of a new vaccination, the durability of a new product, the proportion of defect in a manufacturing process, and so on. There is some benefit or difference that the researchers hope to identify.

However, it’s possible that there is no effect or no difference between the experimental groups. In statistics, we call this lack of an effect the null hypothesis. Therefore, if you can reject the null, you can favor the alternative hypothesis, which states that the effect exists (doesn’t equal zero) at the population level.

You can think of the null as the default theory that requires sufficiently strong evidence against in order to reject it.

For example, in a 2-sample t-test, the null often states that the difference between the two means equals zero.

When you can reject the null hypothesis, your results are statistically significant. Learn more about Statistical Significance: Definition & Meaning .

Related post : Understanding the Null Hypothesis in More Detail

Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is the other theory about the properties of the population in hypothesis testing. Typically, the alternative hypothesis states that a population parameter does not equal the null hypothesis value. In other words, there is a non-zero effect. If your sample contains sufficient evidence, you can reject the null and favor the alternative hypothesis. The alternative is often identified with H 1 or H A .

For example, in a 2-sample t-test, the alternative often states that the difference between the two means does not equal zero.

You can specify either a one- or two-tailed alternative hypothesis:

If you perform a two-tailed hypothesis test, the alternative states that the population parameter does not equal the null value. For example, when the alternative hypothesis is H A : μ ≠ 0, the test can detect differences both greater than and less than the null value.

A one-tailed alternative has more power to detect an effect but it can test for a difference in only one direction. For example, H A : μ > 0 can only test for differences that are greater than zero.

Related posts : Understanding T-tests and One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Hypothesis Tests Explained

P-values are the probability that you would obtain the effect observed in your sample, or larger, if the null hypothesis is correct. In simpler terms, p-values tell you how strongly your sample data contradict the null. Lower p-values represent stronger evidence against the null. You use P-values in conjunction with the significance level to determine whether your data favor the null or alternative hypothesis.

Related post : Interpreting P-values Correctly

Significance Level (Alpha)

For instance, a significance level of 0.05 signifies a 5% risk of deciding that an effect exists when it does not exist.

Use p-values and significance levels together to help you determine which hypothesis the data support. If the p-value is less than your significance level, you can reject the null and conclude that the effect is statistically significant. In other words, the evidence in your sample is strong enough to be able to reject the null hypothesis at the population level.

Related posts : Graphical Approach to Significance Levels and P-values and Conceptual Approach to Understanding Significance Levels

Types of Errors in Hypothesis Testing

Statistical hypothesis tests are not 100% accurate because they use a random sample to draw conclusions about entire populations. There are two types of errors related to drawing an incorrect conclusion.

- False positives: You reject a null that is true. Statisticians call this a Type I error . The Type I error rate equals your significance level or alpha (α).

- False negatives: You fail to reject a null that is false. Statisticians call this a Type II error. Generally, you do not know the Type II error rate. However, it is a larger risk when you have a small sample size , noisy data, or a small effect size. The type II error rate is also known as beta (β).

Statistical power is the probability that a hypothesis test correctly infers that a sample effect exists in the population. In other words, the test correctly rejects a false null hypothesis. Consequently, power is inversely related to a Type II error. Power = 1 – β. Learn more about Power in Statistics .

Related posts : Types of Errors in Hypothesis Testing and Estimating a Good Sample Size for Your Study Using Power Analysis

Which Type of Hypothesis Test is Right for You?

There are many different types of procedures you can use. The correct choice depends on your research goals and the data you collect. Do you need to understand the mean or the differences between means? Or, perhaps you need to assess proportions. You can even use hypothesis testing to determine whether the relationships between variables are statistically significant.

To choose the proper statistical procedure, you’ll need to assess your study objectives and collect the correct type of data . This background research is necessary before you begin a study.

Related Post : Hypothesis Tests for Continuous, Binary, and Count Data

Statistical tests are crucial when you want to use sample data to make conclusions about a population because these tests account for sample error. Using significance levels and p-values to determine when to reject the null hypothesis improves the probability that you will draw the correct conclusion.

To see an alternative approach to these traditional hypothesis testing methods, learn about bootstrapping in statistics !

If you want to see examples of hypothesis testing in action, I recommend the following posts that I have written:

- How Effective Are Flu Shots? This example shows how you can use statistics to test proportions.

- Fatality Rates in Star Trek . This example shows how to use hypothesis testing with categorical data.

- Busting Myths About the Battle of the Sexes . A fun example based on a Mythbusters episode that assess continuous data using several different tests.

- Are Yawns Contagious? Another fun example inspired by a Mythbusters episode.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

January 14, 2024 at 8:43 am

Hello professor Jim, how are you doing! Pls. What are the properties of a population and their examples? Thanks for your time and understanding.

January 14, 2024 at 12:57 pm

Please read my post about Populations vs. Samples for more information and examples.

Also, please note there is a search bar in the upper-right margin of my website. Use that to search for topics.

July 5, 2023 at 7:05 am

Hello, I have a question as I read your post. You say in p-values section

“P-values are the probability that you would obtain the effect observed in your sample, or larger, if the null hypothesis is correct. In simpler terms, p-values tell you how strongly your sample data contradict the null. Lower p-values represent stronger evidence against the null.”

But according to your definition of effect, the null states that an effect does not exist, correct? So what I assume you want to say is that “P-values are the probability that you would obtain the effect observed in your sample, or larger, if the null hypothesis is **incorrect**.”

July 6, 2023 at 5:18 am

Hi Shrinivas,

The correct definition of p-value is that it is a probability that exists in the context of a true null hypothesis. So, the quotation is correct in stating “if the null hypothesis is correct.”

Essentially, the p-value tells you the likelihood of your observed results (or more extreme) if the null hypothesis is true. It gives you an idea of whether your results are surprising or unusual if there is no effect.

Hence, with sufficiently low p-values, you reject the null hypothesis because it’s telling you that your sample results were unlikely to have occurred if there was no effect in the population.

I hope that helps make it more clear. If not, let me know I’ll attempt to clarify!

May 8, 2023 at 12:47 am

Thanks a lot Ny best regards

May 7, 2023 at 11:15 pm

Hi Jim Can you tell me something about size effect? Thanks

May 8, 2023 at 12:29 am

Here’s a post that I’ve written about Effect Sizes that will hopefully tell you what you need to know. Please read that. Then, if you have any more specific questions about effect sizes, please post them there. Thanks!

January 7, 2023 at 4:19 pm

Hi Jim, I have only read two pages so far but I am really amazed because in few paragraphs you made me clearly understand the concepts of months of courses I received in biostatistics! Thanks so much for this work you have done it helps a lot!

January 10, 2023 at 3:25 pm

Thanks so much!

June 17, 2021 at 1:45 pm

Can you help in the following question: Rocinante36 is priced at ₹7 lakh and has been designed to deliver a mileage of 22 km/litre and a top speed of 140 km/hr. Formulate the null and alternative hypotheses for mileage and top speed to check whether the new models are performing as per the desired design specifications.

April 19, 2021 at 1:51 pm

Its indeed great to read your work statistics.

I have a doubt regarding the one sample t-test. So as per your book on hypothesis testing with reference to page no 45, you have mentioned the difference between “the sample mean and the hypothesised mean is statistically significant”. So as per my understanding it should be quoted like “the difference between the population mean and the hypothesised mean is statistically significant”. The catch here is the hypothesised mean represents the sample mean.

Please help me understand this.

Regards Rajat

April 19, 2021 at 3:46 pm

Thanks for buying my book. I’m so glad it’s been helpful!

The test is performed on the sample but the results apply to the population. Hence, if the difference between the sample mean (observed in your study) and the hypothesized mean is statistically significant, that suggests that population does not equal the hypothesized mean.

For one sample tests, the hypothesized mean is not the sample mean. It is a mean that you want to use for the test value. It usually represents a value that is important to your research. In other words, it’s a value that you pick for some theoretical/practical reasons. You pick it because you want to determine whether the population mean is different from that particular value.

I hope that helps!

November 5, 2020 at 6:24 am

Jim, you are such a magnificent statistician/economist/econometrician/data scientist etc whatever profession. Your work inspires and simplifies the lives of so many researchers around the world. I truly admire you and your work. I will buy a copy of each book you have on statistics or econometrics. Keep doing the good work. Remain ever blessed

November 6, 2020 at 9:47 pm

Hi Renatus,

Thanks so much for you very kind comments. You made my day!! I’m so glad that my website has been helpful. And, thanks so much for supporting my books! 🙂

November 2, 2020 at 9:32 pm

Hi Jim, I hope you are aware of 2019 American Statistical Association’s official statement on Statistical Significance: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00031305.2019.1583913 In case you do not bother reading the full article, may I quote you the core message here: “We conclude, based on our review of the articles in this special issue and the broader literature, that it is time to stop using the term “statistically significant” entirely. Nor should variants such as “significantly different,” “p < 0.05,” and “nonsignificant” survive, whether expressed in words, by asterisks in a table, or in some other way."

With best wishes,

November 3, 2020 at 2:09 am

I’m definitely aware of the debate surrounding how to use p-values most effectively. However, I need to correct you on one point. The link you provide is NOT a statement by the American Statistical Association. It is an editorial by several authors.

There is considerable debate over this issue. There are problems with p-values. However, as the authors state themselves, much of the problem is over people’s mindsets about how to use p-values and their incorrect interpretations about what statistical significance does and does not mean.

If you were to read my website more thoroughly, you’d be aware that I share many of their concerns and I address them in multiple posts. One of the authors’ key points is the need to be thoughtful and conduct thoughtful research and analysis. I emphasize this aspect in multiple posts on this topic. I’ll ask you to read the following three because they all address some of the authors’ concerns and suggestions. But you might run across others to read as well.

Five Tips for Using P-values to Avoid Being Misled How to Interpret P-values Correctly P-values and the Reproducibility of Experimental Results

September 24, 2020 at 11:52 pm

HI Jim, i just want you to know that you made explanation for Statistics so simple! I should say lesser and fewer words that reduce the complexity. All the best! 🙂

September 25, 2020 at 1:03 am

Thanks, Rene! Your kind words mean a lot to me! I’m so glad it has been helpful!

September 23, 2020 at 2:21 am

Honestly, I never understood stats during my entire M.Ed course and was another nightmare for me. But how easily you have explained each concept, I have understood stats way beyond my imagination. Thank you so much for helping ignorant research scholars like us. Looking forward to get hardcopy of your book. Kindly tell is it available through flipkart?

September 24, 2020 at 11:14 pm

I’m so happy to hear that my website has been helpful!

I checked on flipkart and it appears like my books are not available there. I’m never exactly sure where they’re available due to the vagaries of different distribution channels. They are available on Amazon in India.

Introduction to Statistics: An Intuitive Guide (Amazon IN) Hypothesis Testing: An Intuitive Guide (Amazon IN)

July 26, 2020 at 11:57 am

Dear Jim I am a teacher from India . I don’t have any background in statistics, and still I should tell that in a single read I can follow your explanations . I take my entire biostatistics class for botany graduates with your explanations. Thanks a lot. May I know how I can avail your books in India

July 28, 2020 at 12:31 am

Right now my books are only available as ebooks from my website. However, soon I’ll have some exciting news about other ways to obtain it. Stay tuned! I’ll announce it on my email list. If you’re not already on it, you can sign up using the form that is in the right margin of my website.

June 22, 2020 at 2:02 pm

Also can you please let me if this book covers topics like EDA and principal component analysis?

June 22, 2020 at 2:07 pm

This book doesn’t cover principal components analysis. Although, I wouldn’t really classify that as a hypothesis test. In the future, I might write a multivariate analysis book that would cover this and others. But, that’s well down the road.

My Introduction to Statistics covers EDA. That’s the largely graphical look at your data that you often do prior to hypothesis testing. The Introduction book perfectly leads right into the Hypothesis Testing book.

June 22, 2020 at 1:45 pm

Thanks for the detailed explanation. It does clear my doubts. I saw that your book related to hypothesis testing has the topics that I am studying currently. I am looking forward to purchasing it.

Regards, Take Care

June 19, 2020 at 1:03 pm

For this particular article I did not understand a couple of statements and it would great if you could help: 1)”If sample error causes the observed difference, the next time someone performs the same experiment the results might be different.” 2)”If the difference does not exist at the population level, you won’t obtain the benefits that you expect based on the sample statistics.”

I discovered your articles by chance and now I keep coming back to read & understand statistical concepts. These articles are very informative & easy to digest. Thanks for the simplifying things.

June 20, 2020 at 9:53 pm

I’m so happy to hear that you’ve found my website to be helpful!

To answer your questions, keep in mind that a central tenant of inferential statistics is that the random sample that a study drew was only one of an infinite number of possible it could’ve drawn. Each random sample produces different results. Most results will cluster around the population value assuming they used good methodology. However, random sampling error always exists and makes it so that population estimates from a sample almost never exactly equal the correct population value.

So, imagine that we’re studying a medication and comparing the treatment and control groups. Suppose that the medicine is truly not effect and that the population difference between the treatment and control group is zero (i.e., no difference.) Despite the true difference being zero, most sample estimates will show some degree of either a positive or negative effect thanks to random sampling error. So, just because a study has an observed difference does not mean that a difference exists at the population level. So, on to your questions:

1. If the observed difference is just random error, then it makes sense that if you collected another random sample, the difference could change. It could change from negative to positive, positive to negative, more extreme, less extreme, etc. However, if the difference exists at the population level, most random samples drawn from the population will reflect that difference. If the medicine has an effect, most random samples will reflect that fact and not bounce around on both sides of zero as much.

2. This is closely related to the previous answer. If there is no difference at the population level, but say you approve the medicine because of the observed effects in a sample. Even though your random sample showed an effect (which was really random error), that effect doesn’t exist. So, when you start using it on a larger scale, people won’t benefit from the medicine. That’s why it’s important to separate out what is easily explained by random error versus what is not easily explained by it.

I think reading my post about how hypothesis tests work will help clarify this process. Also, in about 24 hours (as I write this), I’ll be releasing my new ebook about Hypothesis Testing!

May 29, 2020 at 5:23 am

Hi Jim, I really enjoy your blog. Can you please link me on your blog where you discuss about Subgroup analysis and how it is done? I need to use non parametric and parametric statistical methods for my work and also do subgroup analysis in order to identify potential groups of patients that may benefit more from using a treatment than other groups.

May 29, 2020 at 2:12 pm

Hi, I don’t have a specific article about subgroup analysis. However, subgroup analysis is just the dividing up of a larger sample into subgroups and then analyzing those subgroups separately. You can use the various analyses I write about on the subgroups.

Alternatively, you can include the subgroups in regression analysis as an indicator variable and include that variable as a main effect and an interaction effect to see how the relationships vary by subgroup without needing to subdivide your data. I write about that approach in my article about comparing regression lines . This approach is my preferred approach when possible.

April 19, 2020 at 7:58 am

sir is confidence interval is a part of estimation?

April 17, 2020 at 3:36 pm

Sir can u plz briefly explain alternatives of hypothesis testing? I m unable to find the answer

April 18, 2020 at 1:22 am

Assuming you want to draw conclusions about populations by using samples (i.e., inferential statistics ), you can use confidence intervals and bootstrap methods as alternatives to the traditional hypothesis testing methods.

March 9, 2020 at 10:01 pm

Hi JIm, could you please help with activities that can best teach concepts of hypothesis testing through simulation, Also, do you have any question set that would enhance students intuition why learning hypothesis testing as a topic in introductory statistics. Thanks.

March 5, 2020 at 3:48 pm

Hi Jim, I’m studying multiple hypothesis testing & was wondering if you had any material that would be relevant. I’m more trying to understand how testing multiple samples simultaneously affects your results & more on the Bonferroni Correction

March 5, 2020 at 4:05 pm

I write about multiple comparisons (aka post hoc tests) in the ANOVA context . I don’t talk about Bonferroni Corrections specifically but I cover related types of corrections. I’m not sure if that exactly addresses what you want to know but is probably the closest I have already written. I hope it helps!

January 14, 2020 at 9:03 pm

Thank you! Have a great day/evening.

January 13, 2020 at 7:10 pm

Any help would be greatly appreciated. What is the difference between The Hypothesis Test and The Statistical Test of Hypothesis?

January 14, 2020 at 11:02 am

They sound like the same thing to me. Unless this is specialized terminology for a particular field or the author was intending something specific, I’d guess they’re one and the same.

April 1, 2019 at 10:00 am

so these are the only two forms of Hypothesis used in statistical testing?

April 1, 2019 at 10:02 am

Are you referring to the null and alternative hypothesis? If so, yes, that’s those are the standard hypotheses in a statistical hypothesis test.

April 1, 2019 at 9:57 am

year very insightful post, thanks for the write up

October 27, 2018 at 11:09 pm

hi there, am upcoming statistician, out of all blogs that i have read, i have found this one more useful as long as my problem is concerned. thanks so much

October 27, 2018 at 11:14 pm

Hi Stano, you’re very welcome! Thanks for your kind words. They mean a lot! I’m happy to hear that my posts were able to help you. I’m sure you will be a fantastic statistician. Best of luck with your studies!

October 26, 2018 at 11:39 am

Dear Jim, thank you very much for your explanations! I have a question. Can I use t-test to compare two samples in case each of them have right bias?

October 26, 2018 at 12:00 pm

Hi Tetyana,

You’re very welcome!

The term “right bias” is not a standard term. Do you by chance mean right skewed distributions? In other words, if you plot the distribution for each group on a histogram they have longer right tails? These are not the symmetrical bell-shape curves of the normal distribution.

If that’s the case, yes you can as long as you exceed a specific sample size within each group. I include a table that contains these sample size requirements in my post about nonparametric vs parametric analyses .

Bias in statistics refers to cases where an estimate of a value is systematically higher or lower than the true value. If this is the case, you might be able to use t-tests, but you’d need to be sure to understand the nature of the bias so you would understand what the results are really indicating.

I hope this helps!

April 2, 2018 at 7:28 am

Simple and upto the point 👍 Thank you so much.