Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, what are the benefits of group work.

“More hands make for lighter work.” “Two heads are better than one.” “The more the merrier.”

These adages speak to the potential groups have to be more productive, creative, and motivated than individuals on their own.

Benefits for students

Group projects can help students develop a host of skills that are increasingly important in the professional world (Caruso & Woolley, 2008; Mannix & Neale, 2005). Positive group experiences, moreover, have been shown to contribute to student learning, retention and overall college success (Astin, 1997; Tinto, 1998; National Survey of Student Engagement, 2006).

Properly structured, group projects can reinforce skills that are relevant to both group and individual work, including the ability to:

- Break complex tasks into parts and steps

- Plan and manage time

- Refine understanding through discussion and explanation

- Give and receive feedback on performance

- Challenge assumptions

- Develop stronger communication skills.

Group projects can also help students develop skills specific to collaborative efforts, allowing students to...

- Tackle more complex problems than they could on their own.

- Delegate roles and responsibilities.

- Share diverse perspectives.

- Pool knowledge and skills.

- Hold one another (and be held) accountable.

- Receive social support and encouragement to take risks.

- Develop new approaches to resolving differences.

- Establish a shared identity with other group members.

- Find effective peers to emulate.

- Develop their own voice and perspectives in relation to peers.

While the potential learning benefits of group work are significant, simply assigning group work is no guarantee that these goals will be achieved. In fact, group projects can – and often do – backfire badly when they are not designed , supervised , and assessed in a way that promotes meaningful teamwork and deep collaboration.

Benefits for instructors

Faculty can often assign more complex, authentic problems to groups of students than they could to individuals. Group work also introduces more unpredictability in teaching, since groups may approach tasks and solve problems in novel, interesting ways. This can be refreshing for instructors. Additionally, group assignments can be useful when there are a limited number of viable project topics to distribute among students. And they can reduce the number of final products instructors have to grade.

Whatever the benefits in terms of teaching, instructors should take care only to assign as group work tasks that truly fulfill the learning objectives of the course and lend themselves to collaboration. Instructors should also be aware that group projects can add work for faculty at different points in the semester and introduce its own grading complexities .

Astin, A. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Caruso, H.M., & Wooley, A.W. (2008). Harnessing the power of emergent interdependence to promote diverse team collaboration. Diversity and Groups. 11, 245-266.

Mannix, E., & Neale, M.A. (2005). What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6(2), 31-55.

National Survey of Student Engagement Report. (2006). http://nsse.iub.edu/NSSE_2006_Annual_Report/docs/NSSE_2006_Annual_Report.pdf .

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Request a Consultation

- Workshops and Virtual Conversations

- Technical Support

- Course Design and Preparation

- Observation & Feedback

Teaching Resources

Benefits of Group Work

Resource overview.

Why using group work in your class can improve student learning

There are several benefits for including group work in your class. Sharing these benefits with your students in a transparent manner helps them understand how group work can improve learning and prepare them for life experiences (Taylor 2011). The benefits of group work include the following:

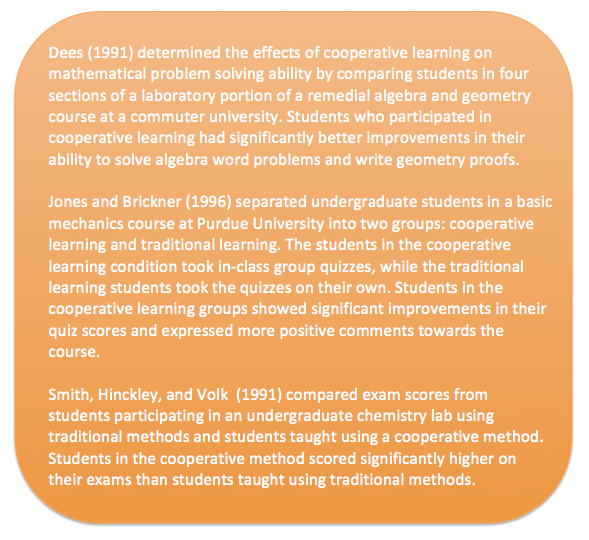

- Students engaged in group work, or cooperative learning, show increased individual achievement compared to students working alone. For example, in their meta-analysis examining over 168 studies of undergraduate students, Johnson et al. (2014) determined that students learning in a collaborative situation had greater knowledge acquisition, retention of material, and higher-order problem solving and reasoning abilities than students working alone. There are several reasons for this difference. Students’ interactions and discussions with others allow the group to construct new knowledge, place it within a conceptual framework of existing knowledge, and then refine and assess what they know and do not know. This group dialogue helps them make sense of what they are learning and what they still need to understand or learn (Ambrose et al. 2010; Eberlein et al. 2008). In addition, groups can tackle more complex problems than individuals can and thus have the potential to gain more expertise and become more engaged in a discipline (Qin et al 1995; Kuh 2007). Group work creates more opportunities for critical thinking and can promote student learning and achievement.

- Student group work enhances communication and other professional development skills. Estimates indicate that 80% of all employees work in group settings (Attle & Baker 2007). Therefore, employers value effective oral and written communication skills as well as the ability to work effectively within diverse groups (ABET 2016-2017; Finelli et al. 2011). Creating facilitated opportunities for group work in your class allows students to enhance their skills in working effectively with others (Bennett & Gadlin 2012; Jackson et al. 2014). Group work gives students the opportunity to engage in process skills critical for processing information, and evaluating and solving problems, as well as management skills through the use of roles within groups, and assessment skills involved in assessing options to make decisions about their group’s final answer. All of these skills are critical to successful teamwork both in the classroom and the workplace.

Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, Inc. Criteria for accrediting Engineering Programs (ABET), 2016-2017 http://www.abet.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria/criteria-for-accrediting-engineering-programs-2016-2017/

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., Lovett, M. C., DiPietro, M., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Attle, S., & Baker, B. 2007 Cooperative learning in a competitive environment: Classroom applications. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , 19 (1), 77-83.

Bennett, L. M., & Gadlin, H. (2012). Collaboration and team science. Journal of Investigative Medicine , 60 (5), 768-775.

Davidson, N., & Major, C. H. (2014). Boundary crossings: Cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and problem-based learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching , 25 (3/4), 7-55.

Eberlein, T., Kampmeier, J., Minderhout, V., Moog, R. S., Platt, T., Varma‐Nelson, P., & White, H. B. (2008). Pedagogies of engagement in science. Biochemistry and molecular biology education , 36 (4), 262-273.

Finelli, C. J., Bergom, I., & Mesa, V. (2011). Student teams in the engineering classroom and beyond: Setting up students for success. CRLT Occasional Papers , 29 .

Jackson, D., Sibson, R., & Riebe, L. (2014). Undergraduate perceptions of the development of team-working skills. Education+ Training , 56 (1), 7-20.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journal on Excellence in University Teaching , 25 (4), 1-26.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2007). Piecing Together the Student Success Puzzle: Research, Propositions, and Recommendations. ASHE Higher Education Report, Volume 32, Number 5. ASHE Higher Education Report , 32 (5), 1-182.

Qin, Z., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1995). Cooperative versus competitive efforts and problem solving. Review of educational Research, 65 (2), 129-143.

Taylor, A. (2011). Top 10 reasons students dislike working in small groups… and why I do it anyway. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education , 39 (3), 219-220.

How to write a Reflection on Group Work Essay

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Here are the exact steps you need to follow for a reflection on group work essay.

- Explain what Reflection Is

- Explore the benefits of group work

- Explore the challenges group

- Give examples of the benefits and challenges your group faced

- Discuss how your group handled your challenges

- Discuss what you will do differently next time

Do you have to reflect on how your group work project went?

This is a super common essay that teachers assign. So, let’s have a look at how you can go about writing a superb reflection on your group work project that should get great grades.

The essay structure I outline below takes the funnel approach to essay writing: it starts broad and general, then zooms in on your specific group’s situation.

Disclaimer: Make sure you check with your teacher to see if this is a good style to use for your essay. Take a draft to your teacher to get their feedback on whether it’s what they’re looking for!

This is a 6-step essay (the 7 th step is editing!). Here’s a general rule for how much depth to go into depending on your word count:

- 1500 word essay – one paragraph for each step, plus a paragraph each for the introduction and conclusion ;

- 3000 word essay – two paragraphs for each step, plus a paragraph each for the introduction and conclusion;

- 300 – 500 word essay – one or two sentences for each step.

Adjust this essay plan depending on your teacher’s requirements and remember to always ask your teacher, a classmate or a professional tutor to review the piece before submitting.

Here’s the steps I’ll outline for you in this advice article:

Step 1. Explain what ‘Reflection’ Is

You might have heard that you need to define your terms in essays. Well, the most important term in this essay is ‘reflection’.

So, let’s have a look at what reflection is…

Reflection is the process of:

- Pausing and looking back at what has just happened; then

- Thinking about how you can get better next time.

Reflection is encouraged in most professions because it’s believed that reflection helps you to become better at your job – we could say ‘reflection makes you a better practitioner’.

Think about it: let’s say you did a speech in front of a crowd. Then, you looked at video footage of that speech and realised you said ‘um’ and ‘ah’ too many times. Next time, you’re going to focus on not saying ‘um’ so that you’ll do a better job next time, right?

Well, that’s reflection: thinking about what happened and how you can do better next time.

It’s really important that you do both of the above two points in your essay. You can’t just say what happened. You need to say how you will do better next time in order to get a top grade on this group work reflection essay.

Scholarly Sources to Cite for Step 1

Okay, so you have a good general idea of what reflection is. Now, what scholarly sources should you use when explaining reflection? Below, I’m going to give you two basic sources that would usually be enough for an undergraduate essay. I’ll also suggest two more sources for further reading if you really want to shine!

I recommend these two sources to cite when explaining what reflective practice is and how it occurs. They are two of the central sources on reflective practice:

- Describe what happened during the group work process

- Explain how you felt during the group work process

- Look at the good and bad aspects of the group work process

- What were some of the things that got in the way of success? What were some things that helped you succeed?

- What could you have done differently to improve the situation?

- Action plan. What are you going to do next time to make the group work process better?

- What? Explain what happened

- So What? Explain what you learned

- Now What? What can I do next time to make the group work process better?

Possible Sources:

Bassot, B. (2015). The reflective practice guide: An interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection . Routledge.

Brock, A. (2014). What is reflection and reflective practice?. In The Early Years Reflective Practice Handbook (pp. 25-39). Routledge.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods . Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Extension Sources for Top Students

Now, if you want to go deeper and really show off your knowledge, have a look at these two scholars:

- John Dewey – the first major scholar to come up with the idea of reflective practice

- Donald Schön – technical rationality, reflection in action vs. reflection on action

Get a Pdf of this article for class

Enjoy subscriber-only access to this article’s pdf

Step 2. Explore the general benefits of group work for learning

Once you have given an explanation of what group work is (and hopefully cited Gibbs, Rolfe, Dewey or Schon), I recommend digging into the benefits of group work for your own learning.

The teacher gave you a group work task for a reason: what is that reason?

You’ll need to explain the reasons group work is beneficial for you. This will show your teacher that you understand what group work is supposed to achieve. Here’s some ideas:

- Multiple Perspectives. Group work helps you to see things from other people’s perspectives. If you did the task on your own, you might not have thought of some of the ideas that your team members contributed to the project.

- Contribution of Unique Skills. Each team member might have a different set of skills they can bring to the table. You can explain how groups can make the most of different team members’ strengths to make the final contribution as good as it can be. For example, one team member might be good at IT and might be able to put together a strong final presentation, while another member might be a pro at researching using google scholar so they got the task of doing the initial scholarly research.

- Improved Communication Skills. Group work projects help you to work on your communication skills. Communication skills required in group work projects include speaking in turn, speaking up when you have ideas, actively listening to other team members’ contributions, and crucially making compromises for the good of the team.

- Learn to Manage Workplace Conflict. Lastly, your teachers often assign you group work tasks so you can learn to manage conflict and disagreement. You’ll come across this a whole lot in the workplace, so your teachers want you to have some experience being professional while handling disagreements.

You might be able to add more ideas to this list, or you might just want to select one or two from that list to write about depending on the length requirements for the essay.

Scholarly Sources for Step 3

Make sure you provide citations for these points above. You might want to use google scholar or google books and type in ‘Benefits of group work’ to find some quality scholarly sources to cite.

Step 3. Explore the general challenges group work can cause

Step 3 is the mirror image of Step 2. For this step, explore the challenges posed by group work.

Students are usually pretty good at this step because you can usually think of some aspects of group work that made you anxious or frustrated. Here are a few common challenges that group work causes:

- Time Consuming. You need to organize meetups and often can’t move onto the next component of the project until everyone has agree to move on. When working on your own you can just crack on and get it done. So, team work often takes a lot of time and requires significant pre-planning so you don’t miss your submission deadlines!

- Learning Style Conflicts. Different people learn in different ways. Some of us like to get everything done at the last minute or are not very meticulous in our writing. Others of us are very organized and detailed and get anxious when things don’t go exactly how we expect. This leads to conflict and frustration in a group work setting.

- Free Loaders. Usually in a group work project there’s people who do more work than others. The issue of free loaders is always going to be a challenge in group work, and you can discuss in this section how ensuring individual accountability to the group is a common group work issue.

- Communication Breakdown. This is one especially for online students. It’s often the case that you email team members your ideas or to ask them to reply by a deadline and you don’t hear back from them. Regular communication is an important part of group work, yet sometimes your team members will let you down on this part.

As with Step 3, consider adding more points to this list if you need to, or selecting one or two if your essay is only a short one.

8 Pros And Cons Of Group Work At University

| Pros of Group Work | Cons of Group Work |

|---|---|

| Members of your team will have different perspectives to bring to the table. Embrace team brainstorming to bring in more ideas than you would on your own. | You can get on with an individual task at your own pace, but groups need to arrange meet-ups and set deadlines to function effectively. This is time-consuming and requires pre-planning. |

| Each of your team members will have different skills. Embrace your IT-obsessed team member’s computer skills; embrace the organizer’s skills for keeping the group on track, and embrace the strongest writer’s editing skills to get the best out of your group. | Some of your team members will want to get everything done at once; others will procrastinate frequently. You might also have conflicts in strategic directions depending on your different approaches to learning. |

| Use group work to learn how to communicate more effectively. Focus on active listening and asking questions that will prompt your team members to expand on their ideas. | Many groups struggle with people who don’t carry their own weight. You need to ensure you delegate tasks to the lazy group members and be stern with them about sticking to the deadlines they agreed upon. |

| In the workforce you’re not going to get along with your colleagues. Use group work at university to learn how to deal with difficult team members calmly and professionally. | It can be hard to get group members all on the same page. Members don’t rely to questions, get anxiety and shut down, or get busy with their own lives. It’s important every team member is ready and available for ongoing communication with the group. |

You’ll probably find you can cite the same scholarly sources for both steps 2 and 3 because if a source discusses the benefits of group work it’ll probably also discuss the challenges.

Step 4. Explore the specific benefits and challenges your group faced

Step 4 is where you zoom in on your group’s specific challenges. Have a think: what were the issues you really struggled with as a group?

- Was one team member absent for a few of the group meetings?

- Did the group have to change some deadlines due to lack of time?

- Were there any specific disagreements you had to work through?

- Did a group member drop out of the group part way through?

- Were there any communication break downs?

Feel free to also mention some things your group did really well. Have a think about these examples:

- Was one member of the group really good at organizing you all?

- Did you make some good professional relationships?

- Did a group member help you to see something from an entirely new perspective?

- Did working in a group help you to feel like you weren’t lost and alone in the process of completing the group work component of your course?

Here, because you’re talking about your own perspectives, it’s usually okay to use first person language (but check with your teacher). You are also talking about your own point of view so citations might not be quite as necessary, but it’s still a good idea to add in one or two citations – perhaps to the sources you cited in Steps 2 and 3?

Step 5. Discuss how your group managed your challenges

Step 5 is where you can explore how you worked to overcome some of the challenges you mentioned in Step 4.

So, have a think:

- Did your group make any changes part way through the project to address some challenges you faced?

- Did you set roles or delegate tasks to help ensure the group work process went smoothly?

- Did you contact your teacher at any point for advice on how to progress in the group work scenario?

- Did you use technology such as Google Docs or Facebook Messenger to help you to collaborate more effectively as a team?

In this step, you should be showing how your team was proactive in reflecting on your group work progress and making changes throughout the process to ensure it ran as smoothly as possible. This act of making little changes throughout the group work process is what’s called ‘Reflection in Action’ (Schön, 2017).

Scholarly Source for Step 5

Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . Routledge.

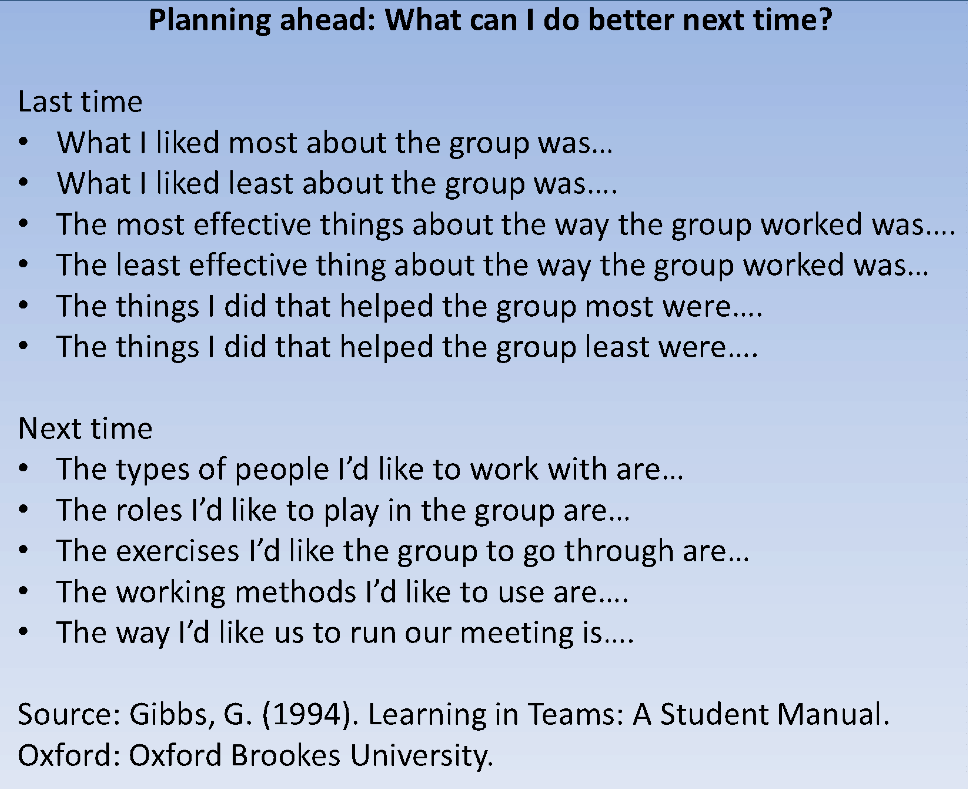

Step 6. Conclude by exploring what you will do differently next time

Step 6 is the most important step, and the one far too many students skip. For Step 6, you need to show how you not only reflected on what happened but also are able to use that reflection for personal growth into the future.

This is the heart and soul of your piece: here, you’re tying everything together and showing why reflection is so important!

This is the ‘action plan’ step in Gibbs’ cycle (you might want to cite Gibbs in this section!).

For Step 6, make some suggestions about how (based on your reflection) you now have some takeaway tips that you’ll bring forward to improve your group work skills next time. Here’s some ideas:

- Will you work harder next time to set deadlines in advance?

- Will you ensure you set clearer group roles next time to ensure the process runs more smoothly?

- Will you use a different type of technology (such as Google Docs) to ensure group communication goes more smoothly?

- Will you make sure you ask for help from your teacher earlier on in the process when you face challenges?

- Will you try harder to see things from everyone’s perspectives so there’s less conflict?

This step will be personalized based upon your own group work challenges and how you felt about the group work process. Even if you think your group worked really well together, I recommend you still come up with one or two ideas for continual improvement. Your teacher will want to see that you used reflection to strive for continual self-improvement.

Scholarly Source for Step 6

Step 7. edit.

Okay, you’ve got the nuts and bolts of the assessment put together now! Next, all you’ve got to do is write up the introduction and conclusion then edit the piece to make sure you keep growing your grades.

Here’s a few important suggestions for this last point:

- You should always write your introduction and conclusion last. They will be easier to write now that you’ve completed the main ‘body’ of the essay;

- Use my 5-step I.N.T.R.O method to write your introduction;

- Use my 5 C’s Conclusion method to write your conclusion;

- Use my 5 tips for editing an essay to edit it;

- Use the ProWritingAid app to get advice on how to improve your grammar and spelling. Make sure to also use the report on sentence length. It finds sentences that are too long and gives you advice on how to shorten them – such a good strategy for improving evaluative essay quality!

- Make sure you contact your teacher and ask for a one-to-one tutorial to go through the piece before submitting. This article only gives general advice, and you might need to make changes based upon the specific essay requirements that your teacher has provided.

That’s it! 7 steps to writing a quality group work reflection essay. I hope you found it useful. If you liked this post and want more clear and specific advice on writing great essays, I recommend signing up to my personal tutor mailing list.

Let’s sum up with those 7 steps one last time:

- Explain what ‘Reflection’ Is

- Explore the benefits of group work for learning

- Explore the challenges of group work for learning

- Explore the specific benefits and challenges your group faced

- Discuss how your group managed your challenges

- Conclude by exploring what you will do differently next time

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

2 thoughts on “How to write a Reflection on Group Work Essay”

Great instructions on writing a reflection essay. I would not change anything.

Thanks so much for your feedback! I really appreciate it. – Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Our Mission

Group Work That Works

Educators weigh in on solutions to the common pitfalls of group work.

Mention group work and you’re confronted with pointed questions and criticisms. The big problems, according to our audience: One or two students do all the work; it can be hard on introverts; and grading the group isn’t fair to the individuals.

But the research suggests that a certain amount of group work is beneficial.

“The most effective creative process alternates between time in groups, collaboration, interaction, and conversation... [and] times of solitude, where something different happens cognitively in your brain,” says Dr. Keith Sawyer, a researcher on creativity and collaboration, and author of Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration .

So we looked through our archives and reached out to educators on Facebook to find out what solutions they’ve come up with for these common problems.

Making Sure Everyone Participates

“How many times have we put students in groups only to watch them interact with their laptops instead of each other? Or complain about a lazy teammate?” asks Mary Burns, a former French, Latin, and English middle and high school teacher who now offers professional development in technology integration.

Unequal participation is perhaps the most common complaint about group work. Still, a review of Edutopia’s archives—and the tens of thousands of insights we receive in comments and reactions to our articles—revealed a handful of practices that educators use to promote equal participation. These involve setting out clear expectations for group work, increasing accountability among participants, and nurturing a productive group work dynamic.

Norms: At Aptos Middle School in San Francisco, the first step for group work is establishing group norms. Taji Allen-Sanchez, a sixth- and seventh-grade science teacher, lists expectations on the whiteboard, such as “everyone contributes” and “help others do things for themselves.”

For ambitious projects, Mikel Grady Jones, a high school math teacher in Houston, takes it a step further, asking her students to sign a group contract in which they agree on how they’ll divide the tasks and on expectations like “we all promise to do our work on time.” Heather Wolpert-Gawron, an English middle school teacher in Los Angeles, suggests creating a classroom contract with your students at the start of the year, so that agreed-upon norms can be referenced each time a new group activity begins.

Group size: It’s a simple fix, but the size of the groups can help establish the right dynamics. Generally, smaller groups are better because students can’t get away with hiding while the work is completed by others.

“When there is less room to hide, nonparticipation is more difficult,” says Burns. She recommends groups of four to five students, while Brande Tucker Arthur, a 10th-grade biology teacher in Lynchburg, Virginia, recommends even smaller groups of two or three students.

Meaningful roles: Roles can play an important part in keeping students accountable, but not all roles are helpful. A role like materials manager, for example, won’t actively engage a student in contributing to a group problem; the roles must be both meaningful and interdependent.

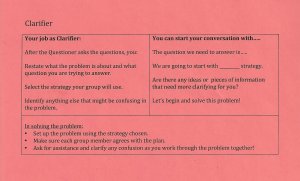

At University Park Campus School , a grade 7–12 school in Worcester, Massachusetts, students take on highly interdependent roles like summarizer, questioner, and clarifier. In an ongoing project, the questioner asks probing questions about the problem and suggests a few ideas on how to solve it, while the clarifier attempts to clear up any confusion, restates the problem, and selects a possible strategy the group will use as they move forward.

At Design 39, a K–8 school in San Diego, groups and roles are assigned randomly using Random Team Generator , but ClassDojo , Team Shake , and drawing students’ names from a container can also do the trick. In a practice called vertical learning, Design 39 students conduct group work publicly, writing out their thought processes on whiteboards to facilitate group feedback. The combination of randomizing teams and public sharing exposes students to a range of problem-solving approaches, gets them more comfortable with making mistakes, promotes teamwork, and allows kids to utilize different skill sets during each project.

Rich tasks: Making sure that a project is challenging and compelling is critical. A rich task is a problem that has multiple pathways to the solution and that one person would have difficulty solving on their own.

In an eighth-grade math class at Design 39, one recent rich task explored the concept of how monetary investments grow: Groups were tasked with solving exponential growth problems using simple and compound interest rates.

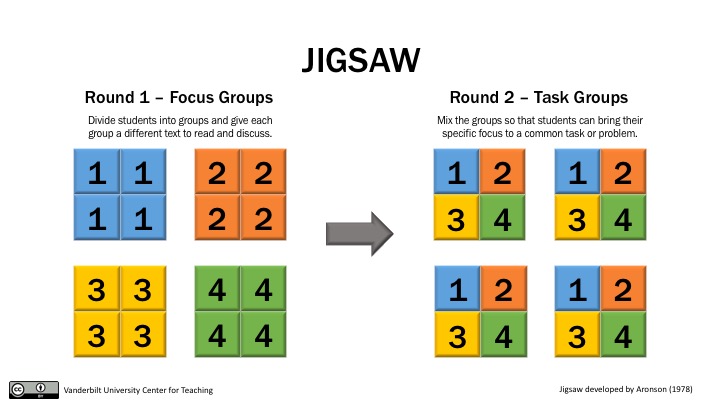

Rich tasks are not just for math class. When Dan St. Louis, the principal of University Park, was a teacher, he asked his English students to come up with a group definition of the word Orwellian . They did this through the jigsaw method, a type of grouping strategy that John Hattie’s study Visible Learning ranked as highly effective.

“Five groups of five students might each read a different news article about the modern world,” says St. Louis. “Then each student would join a new group of five where they need to explain their previous group’s article to each other and make connections to each. Using these connections, the group must then construct a definition of the word Orwellian .” For another example of the jigsaw approach, see this video from Cult of Pedagogy.

Supporting Introverts

Teachers worry about the impact of group work on introverts. Some of our educators suggest that giving introverts choice in who they’re grouped with can help them feel more comfortable.

“Even the quietest students are usually comfortable and confident when they are with peers with whom they connect,” says Shelly Kunkle, a veteran teacher at Wasawee Middle School in North Webster, Indiana. Wolpert-Gawron asks her students to list four peers they want to work with and then makes sure to pair them with one from their list.

Having defined roles within groups—like clarifier or questioner—also provides structure for students who may be less comfortable within complex social dynamics, and ensures that introverts don’t get overshadowed by their more extroverted peers.

Finally, be mindful that introverted students often simply need time to recharge. “Many introverts do not mind and even enjoy interacting in groups as long as they get some quiet time and solitude to recharge. It’s not about being shy or feeling unsafe in a large group,” says Barb Larochelle, a recently retired high school English teacher in Edmonton, Alberta, who taught for 29 years.

“I planned classes with some time to work quietly alone, some time to interact in smaller groups or as a whole class, and some time to get up and move around a little. A whole class of any one of those is going to be hard on one group, but a balance works well.”

Assessing Group Work

Grading group work is problematic. Often, you don’t have a clear understanding of what each student knows, and a single student’s lack of effort can torpedo the group grade. To some degree, strategies that assign meaningful roles or that require public presentations from groups provide a window in to each student’s knowledge and contributions.

But not all classwork needs to be graded. Suzanna Kruger, a high school science teacher in Seaside, Oregon, doesn’t grade group work—there are plenty of individual assignments that receive grades, and plenty of other opportunities for formative assessment.

John McCarthy, a former high school English and social studies teacher and current education consultant and adjunct professor at Madonna University for the graduate department for education, suggests using group presentations or group products as a non-graded review for a test. But if you want to grade group work, he recommends making all academic assessments within group work individual assessments. For example, instead of grading a group presentation, McCarthy grades each student on an essay, which the students then use to create their group presentation.

Laura Moffit, a fifth-grade teacher in Wilmington, North Carolina, uses self and peer evaluations to shed light on how each student is contributing to group work—starting with a lesson on how to do an objective evaluation. “Just have students circle :), :|, or :( on three to five statements about each partner, anonymously,” Moffit commented on Facebook. “Then give the evaluations back to each group member. Finding out what people really think of your performance is a wake-up call.”

And Ted Malefyt, a middle school science teacher in Hamilton, Michigan, carries a clipboard with the class list formatted in a spreadsheet and walks around checking in on students while they do group work.

“Using this spreadsheet, you have your own record of which student is meeting your expectations and who needs extra help,” explains Malefyt. “As formative assessment takes place, quickly document with simple checkmarks.”

- The Student Experience

- Financial Aid

- Degree Finder

- Undergraduate Arts & Sciences

- Departments and Programs

- Research, Scholarship & Creativity

- Centers & Institutes

- Geisel School of Medicine

- Guarini School of Graduate & Advanced Studies

- Thayer School of Engineering

- Tuck School of Business

Campus Life

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Athletics & Recreation

- Student Groups & Activities

- Residential Life

- [email protected] Contact & Department Info Mail

- Diversity Statement

- Impact Reports

- Experiential Learning

- Gateway Initiative

- Online Learning

- Apgar Award for Innovation in Teaching

- Annual Reports

- Consultation

- Universal Design for Learning Institute

- Graduate Student and Postdoc Programs

- Learning Fellows Program

- New Faculty Programs

- On-Demand Seminars

- Resources for New Faculty

- Teaching & Learning Principles

- Preparing to Teach: Exploring Beliefs

- Knowledge for Teaching

- Student Development

- Recommended Reading

- Course Design - Getting Started

- Learning Outcomes

- Planning for Assessment

- Syllabus Guide

- Universal Design in Education

- Resilient Course Design

- Wellbeing in Course Design

- Academic Continuity During Disruption

- Nuts & Bolts

- First Day of Class

- Effective Lecturing

Student Group Work

- Inclusive Teaching

- Creating Accessible Materials

- Anti-Racist Pedagogy

- Teaching With Generative AI

- Formative Assessments

- Grading & Feedback

- Saving Time While Grading

- End-of-Term Evaluations

- Classroom Observations

- Other Sources of Teaching Support

- Schedules, Calendars, Maps

- Reserving the Teaching Center

- Funding Opportunities

- News & Events

Search form

- Teaching & Learning Foundations

- Course Design & Preparation

- Evaluating Teaching & Learning

- Dartmouth References

Group work has been shown to support deep learning, long-term information retention, strengthened communication and teamwork skills, and a greater sense of purpose and dedication to course materials––if groups are formed thoughtfully and given clear parameters ( Monson ; Oakley et. al. ; Davis ). Many students and faculty alike have (or have heard) horror stories about group work gone awry. But, research and student feedback show that with a bit of preparation, clear guidelines, and mechanisms for group troubleshooting in place, group work can be more than worth the effort.

Setting Groups Up for Success

"Professors have three major responsibilities concerning the implementation of [group work]––forming groups, training students to be effective collaborators, and managing collaborative groups." ––B.W. Speck

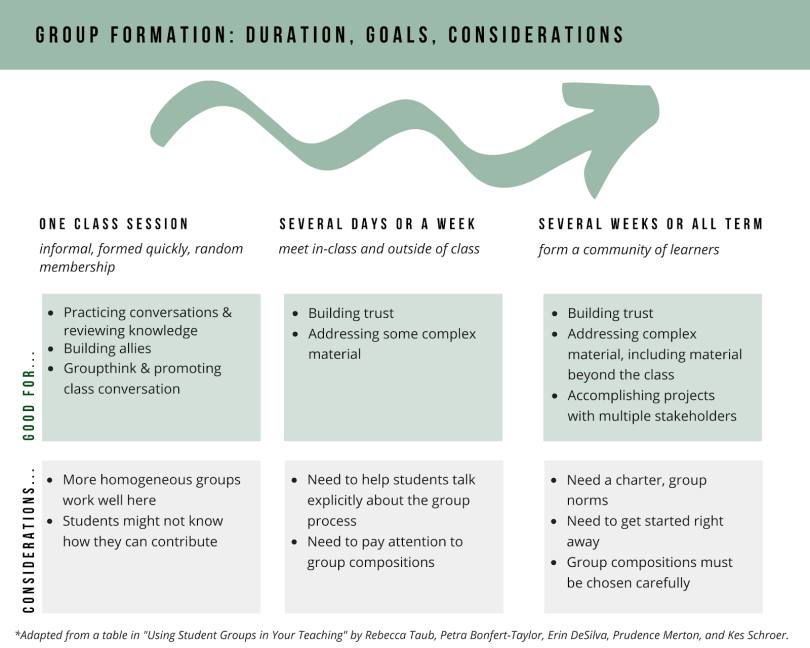

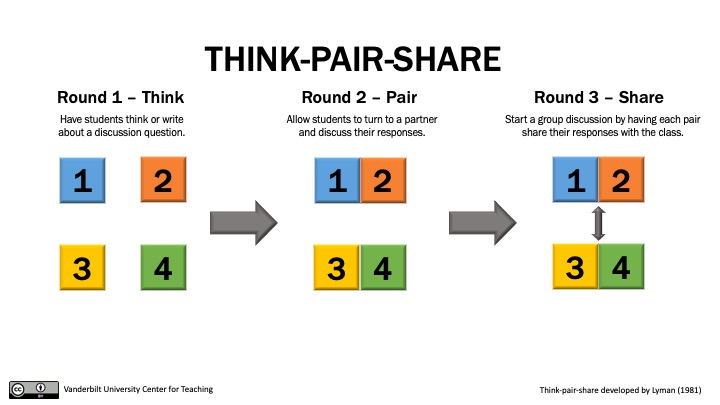

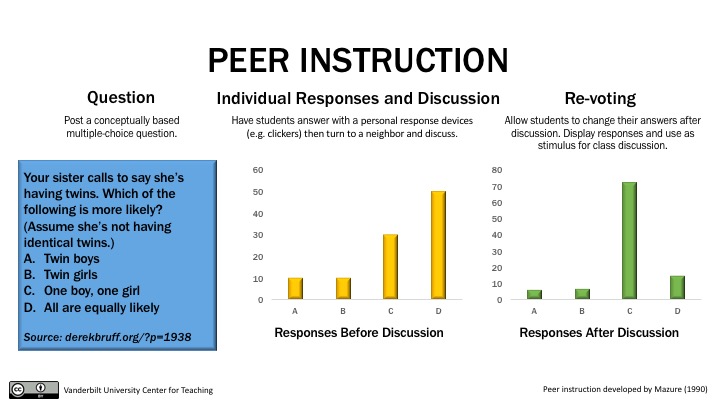

There are many ways to use student groups in your classes, from informal, short-term think-pair-share duos to small discussion groups that are formed and disbanded each class session, writing circles that persist for an entire essay cycle, and formal, long-term groups collaborating on a major course assignment. All of them require some level of instructor guidance on how groups should be formed, how group work should be approached, and what the goals of the work are. In some cases, asking students to turn to a classmate and share a question or comment is sufficient preparation. In others, much more scaffolding needs to be in place if students are to navigate their work successfully as a group. See the figure below for a quick overview of what such scaffolding might look like, based on the duration and goals of group work.

three-panel_detailed_storyboard.png

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on groups that will be working together for a week or more, because the length and complexity of the work such groups do together requires more planning and support. While the specific needs of such groups will depend upon the nature of the assignment, subject matter, and course learning objectives, the literature on group formation and collaborative student work provides some important considerations that are relevant to many cases, across disciplines. Here, these considerations are broken out into three categories: group formation, group training, and group management.

Note: COVID has, predictably, affected students' experience of group work, and not only due to the pivot to remote learning. For an in depth discussion of COVID and student group work, see "Student Teamwork During COVID-19: Challenges, Changes, and Consequences" ( Wildman, et. al. ). Click here to see a summary of the paper's key insights .

Group Formation

For long-term collaborations, groups should be created by instructors .

Student-selected groups are more likely to lead to "social slacking" and self-segregation .

Additionally, student-selected groups are less likely to lead to interdependence and collaboration . Students in the same group may end up breaking apart the project and working separately, or, one student may end up bearing the brunt of the workload.

One study indicated that "students found by a two-to-one ratio that their worst group work experiences were with self-formed groups" ( Feitchner and Davis ).

Self-selected groups tend to be homogeneous in terms of student skill-level and subject-matter experience, gender, and race.

For many types of group work, the ideal group size is 3-4 students .

Exceptions include groups formed for team-based-learning , which works well with 5-7 students, and ensemble practices in the arts , which range widely in group size. STEM-specific studies suggest groups of 3-5.

These smaller sizes help ensure that every group member has a meaningful role, while also making sure that there are enough perspectives represented to prevent inquiry from stalling (see group training, below, for resources on group roles).

In general: "The less skilful the group members, the smaller the groups should be. The shorter amount of time available, the smaller the groups should be" ( Davis ).

Groups thrive when their members are diverse (in terms of skill, prior subject-matter experience, and, yes, demographics).

More specifically, "groups that are gender-balanced, are ethnically diverse, and have members with different problem-solving approaches have been shown to exhibit enhanced collaboration" ( Wilson, Brickman, and Brame ).

Conversely, minority group members are most successful––in your class, and in their academic lives more generally––when they aren't isolated.

Isolated students may not feel empowered to speak and contribute at the same level as their fellow group members. "Studies have shown that when members of at-risk minority groups are isolated in project teams, they tend either to adopt relatively passive roles within the team or are relegated to such roles, thereby losing many of the benefits of the team interactivity" ( Heller and Hollobaugh qtd in Oakley et. al. ).

We know, for example, that men are 1.6x more likely to speak in class than women ( Lee and McCabe 2021). This issue is compounded by isolation within groups.

In fact, such unsuccessful group experiences may contribute to student retention issues: "The isolation these individuals feel within their teams could also contribute to a broader sense of isolation in the student body at large, which may in turn increase the dropout risk" ( Heller and Hollobaugh qtd in Oakley et. al. ).

There is some evidence that teamwork- or working-style has more of an impact on group cohesion than prior academic experience or skill with the subject matter.

"Generally, groups that are gender-balanced, are ethnically diverse, and have members with different problem-solving approaches have been shown to exhibit enhanced collaboration. The data on academic performance as a diversity factor do not point to a single conclusion" ( Wilson, Brickman, and Brame ).

And, finally, from a logistical viewpoint: if you don't provide dedicated group working time in class, group members will need common blocks of free time to meet outside of class.

X-hours can be fantastic as dedicated group-work time, if your course plan allows.

Group Training

"When a professor assumes that students will automatically work well together and provides little or no training in group success, groups can fall apart." ––B.W. Speck

Students express higher levels of satisfaction when instructors are explicit about the process and expectations of group work.

Setting expectations can help ameliorate student aversion to group work rooted in past negative experiences ( Felder and Brent 1996).

Groups tend not to differentiate between "social loafers" and team members who are struggling with the project or course content, exhibiting destructive behavior toward group members who fall into either category equally. By being transparent about the benefits of group work as well as the expectations about how group work should proceed, instructors can prevent much of this potential for group dysfunction ( Freeman and Greenacre ).

Giving students individual (rotating) roles within their group can help instill individual ownership of the project as well as foster collaboration and interdependence.

For instance, Oakley et. al. outline a four person team using the following roles:

Coordinator - "keeps everyone on task and makes sure everyone is involved."

Recorder - "prepares the final solution to be turned in."

Monitor - "checks to make sure everyone understands both the solution and the strategy used to get it."

Checker - "double-checks it before it is handed in."

Other roles might include:

Encourager - "encourages group members to continue to think through their approaches and ideas. The Encourager uses probing questions to help facilitate deeper thinking, and group-wide consideration of ideas" ( Fournier ).

Questioner - "pushes back when the team comes to consensus too quickly, without considering a number of options or points of view. The questioner makes sure that the group hears varied points of view, and that the group is not avoiding potentially rich areas of disagreement" ( Fournier ).

Reflector / Strategy Analyst - "observes team dynamics and guides the consensus-building process (helps group members come to a common conclusion)" ( Fournier ).

Spokesperson / Presenter - "presents the group's ideas to the rest of the class. The Spokesperson should rely on the recorder's notes to guide their report" ( Fournier ).

Requiring group members to rotate through these roles during the term "can help students develop communications skills in a variety of areas rather than relying on a single personal strength" ( Fournier ).

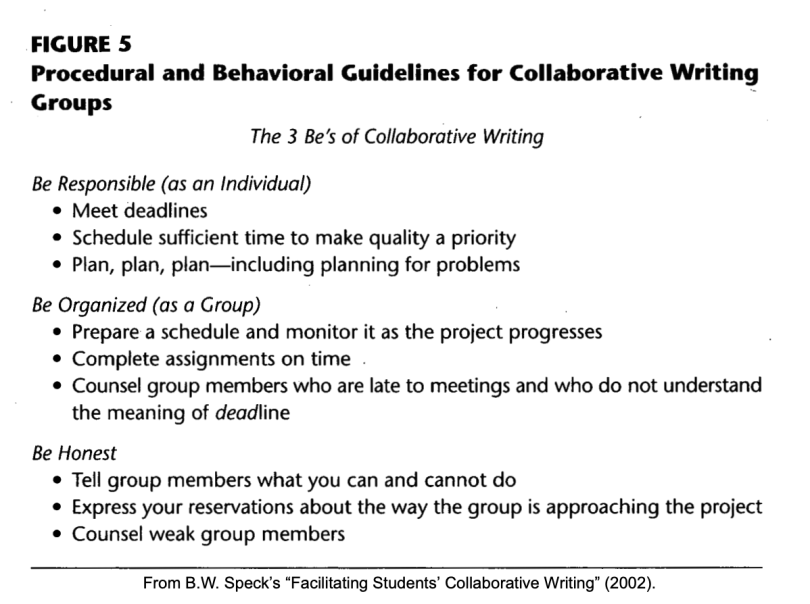

Functional groups develop "norms," "charters," or social contracts with agreed upon behaviors, values, and conflict-management practices.

For example, The 3 Be's of Collaborative Writing B.W. Speck uses with collaborative writing groups:

Be Responsible

Be Organized

3beswriting0.png

The University of Connecticut Writing Center offers this group contract template to be used after forming groups, but before assigning roles as a means to "prevent group discord" and "create a consensus on expectations.

Group Management

Even the most strategically formed groups may still fail if they aren't given sufficient guidance, or management. Some of the most important things to consider when determining how you and your students will work together to manage groups are:

Group Persistence (will students stay in a single group all term, or will groups be formed and reformed throughout the term?)

Motivation (what scaffolding needs to be in place to keep groups motivated?)

"To promote both accountability and autonomy, instructors should create milestones and deadlines for groups but also provide time for the students to expressly assign duties and roles to meet those deadlines" ( Wilson, Brickman, and Brame ).

Dartmouth faculty member, Professor Deborah Brooks, recommends building in opportunities for Peer Recognition .

For discussion groups, you may want to consider occasional opportunities for peer shout outs (for example, a student might want to shout out a group member who helped them understand something in a new way).

For longer, more formal group projects, peer awards can offer groups a fun way to recognize and celebrate their work as well as providing faculty some insight into the way groups worked together.

Assessment (how will group and individual work be assessed? how will students assess their own work and the group as a whole?)

Although it may not be appropriate for all types of group work to be graded, for group projects or assignments, it can be beneficial to assess both the work of the group as a whole and the work of individual group members.

Felder and Brent suggest:

Giving "individual tests that cover all of the material on the team assignments and projects" ( Felder and Brent 2007).

Making "groups responsible for seeing that non-contributors don't get credit" ( Felder and Brent 2007).

Using "peer ratings to make individual adjustments to team assignment grades" ( Felder and Brent 2007).

In addition to assessment via grading, it is important to structure in opportunities for student and group self-assessment.

"Once or twice during the group work task," Barbara Gross Davis suggests, "ask group members to discuss two questions: What action has each member taken that was helpful for the group? What action could each member take to make the group even better?" ( Davis ).

Felder and Brent suggest making plans for "periodic self-assessment of team functioning" every few weeks via written responses to questions such as ( Felder and Brent 2007):

How well are we meeting our goals and expectations?

What are we doing well?

What needs improvement?

What (if anything) will we do differently next time?

Troubleshooting (what happens when groups encounter a problem? what if a group fails to cohere?)

Make a contingency plan to chart out what happens when

Students drop the course, leaving groups too small or imbalance

A group fails to cohere.

Some research suggests that giving students the ability to "fire" a group member who isn't contributing can be an effective strategy ( Felder and Brent 2007).

But resist the urge to dissolve and reform groups frequently.

Studies have shown that:

"It takes at least [one month] for the teams to encounter problems, and learning to work through the problems is an important part of teamwork skill development" ( Felder and Brent 2007).

Build in opportunities for students to tell you how the group work is going:

"Conduct a midterm assessment to find out how students feel about teamwork" ( Felder and Brent 2007).

and, Opportunities for Reflection and Feedback ( will students have a chance to reflect on their group work? how will students report what's happening in their group to you? how will you provide feedback to groups?)

Thomas Wenzel notes that peer- and self-assessment, combined with instructor observations, are critical in courses using group work not only to identify dysfunctional groups but also to identify the contributions of each group member ( Wenzel ).

See this Team Peer Assessment developed by Angela R. Linse of the Schreyer Institute for Teaching Excellence

See the final pages of Oakley et. al. for a useful set of reflective and evaluative worksheets. Namely:

Evaluation of Progress Toward Effective Team Functioning

Team Member Evaluation Form

Peer Rating of Team Members

Autorating System

Note: peer rating and assessment are likely to be most useful as a conversation starter regarding group dynamics and norms.

Team Formation Tool

The Team Formation Tool, a Canvas app developed at Dartmouth, is a survey-based tool for the creation of optimized student groups. With the Team Formation Tool, instructors can create custom surveys designed to sort students into groups based on a cluster of predetermined criteria including time zone, teamwork and working style, preferred time of day to study, and more.

To learn more about the Team Formation Tool, read the overview here or contact [email protected] . To have the Team Formation Tool installed in your Canvas course, submit a Canvas Support Request here , and enter Team Formation Tool Installation in the Short Description of Problem field.

Additional Resources

Using Student Groups in Your Teaching

Episode 073 - Team Based Learning with Jim Sibley , Teaching in Higher Ed Podcast

Babson College Group Project Survival Guide

Effective Strategies for Cooperative Learning .

CBE––Life Sciences Education evidence-based teaching guide for Group Work .

Alison Burke's article, " How to Use Groups Effectively ."

Curated list of resources about Collaborative Learning & Group Work

Curated list of podcast episodes about group learning

Teach Remotely: Collaborative Projects discussion, facilitated by DCAL

Davis, Barbara Gross. Tools for Teaching. Vol. 1st ed, Jossey-Bass, 1993. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,url,uid&db=nlebk&AN=26088&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Feichtner, S. B., and E. A. Davis. "Why Some Groups Fail: A Survey of Students' Experiences with Learning Groups." Journal of Management Education, vol. 9, no. 4, Nov. 1984, pp. 58–73. DOI.org (Crossref), doi: 10.1177/105256298400900409 .

Felder, Richard M., and Rebecca Brent. "Navigating the Bumpy Road to Student-Centered Instruction." College Teaching, vol. 44, no. 2, Apr. 1996, pp. 43–47. DOI.org (Crossref), doi: 10.1080/87567555.1996.9933425 .

Felder, Richard M., and Rebecca Brent. "Cooperative Learning." Active Learning, edited by Patricia Ann Mabrouk, vol. 970, American Chemical Society, 2007, pp. 34–53. DOI.org (Crossref), doi: 10.1021/bk-2007-0970.ch004 .

Fournier, Eric. "Using Roles in Group Work." Washington University in St. Louis Center for Teaching and Learning, https://ctl.wustl.edu/resources/using-roles-in-group-work/ . Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

Freeman, Lynne, and Luke Greenacre. "An Examination of Socially Destructive Behaviors in Group Work." Journal of Marketing Education - J Market Educ, vol. 33, Apr. 2011, pp. 5–17. ResearchGate, doi: 10.1177/0273475310389150 .

Gaunt, Helena, and Danielle Shannon Treacy. "Ensemble Practices in the Arts: A Reflective Matrix to Enhance Team Work and Collaborative Learning in Higher Education." Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, vol. 19, no. 4, SAGE Publications, Oct. 2020, pp. 419–44. SAGE Journals, doi: 10.1177/1474022219885791 .

Hassanien, Ahmed. "Student Experience of Group Work and Group Assessment in Higher Education." Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, vol. 6, no. 1, July 2006, pp. 17–39. DOI.org (Crossref), doi: 10.1300/J172v06n01_02 .

Heller, Patricia, and Mark Hollabaugh. "Teaching Problem Solving through Cooperative Grouping. Part 2: Designing Problems and Structuring Groups." American Journal of Physics, vol. 60, no. 7, American Association of Physics Teachers, July 1992, pp. 637–44. aapt.scitation.org (Atypon), doi: 10.1119/1.17118 .

Monson, Renee. "Groups That Work: Student Achievement in Group Research Projects and Effects on Individual Learning." Teaching Sociology, vol. 45, no. 3, SAGE Publications Inc, July 2017, pp. 240–51. SAGE Journals, doi: 10.1177/0092055X17697772 .

Oakley, Barbara, et al. "Turning Student Groups into Effective Teams." Journal of Student Centered Learning, vol. 2, no. 1, 2004, pp. 9-34. https://www.engr.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/drive/1ofGhdOciEwloA2zofffqkr7jG3SeKRq3/2004-Oakley-paper(JSCL).pdf

Speck, Bruce W. Facilitating Students' Collaborative Writing. Jossey-Bass, 2002, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/ERIC-ED466716/pdf/ERIC-ED466716.pdf , Accessed 2 Feb 2021

Wenzel, Thomas J. "Evaluation Tools To Guide Students' Peer-Assessment and Self-Assessment in Group Activities for the Lab and Classroom." Journal of Chemical Education, vol. 84, no. 1, 2007, p. 182.

Wildman, Jessica, et al. "Student Teamwork During COVID-19: Challenges, Changes, and Consequences." Small Group Research, vol. 0, no. 0, 2021, pp. 1–16.

Wilson, KJ, et al. "Evidence Based Teaching Guide: Group Work." CBE Life Science Education, http://lse.ascb.org/evidence-based-teaching-guides/group-work/ . Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Group work as an incentive for learning – students’ experiences of group work.

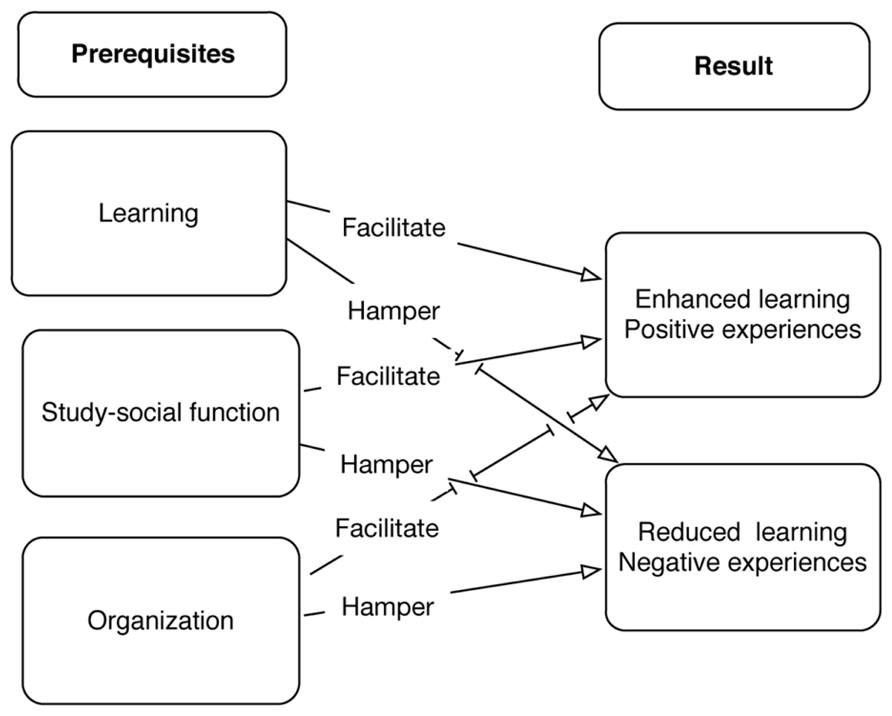

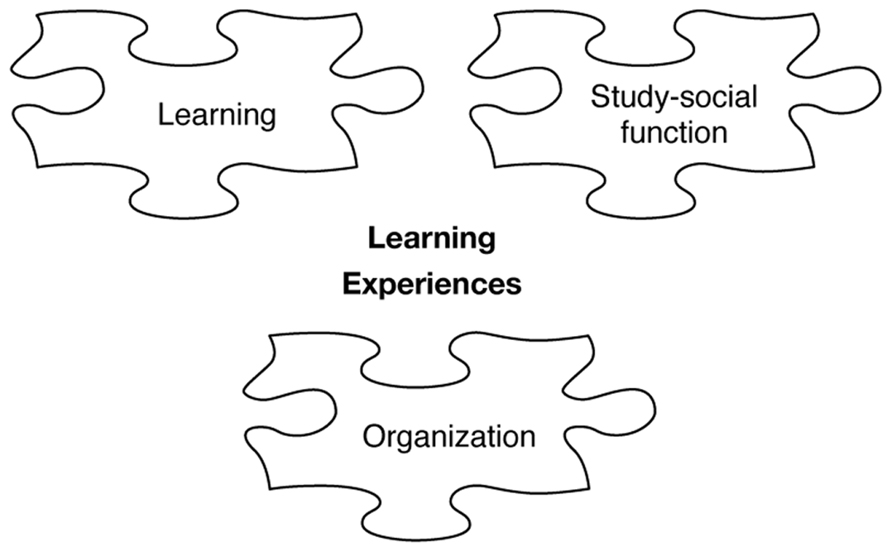

- Division of Psychology, Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

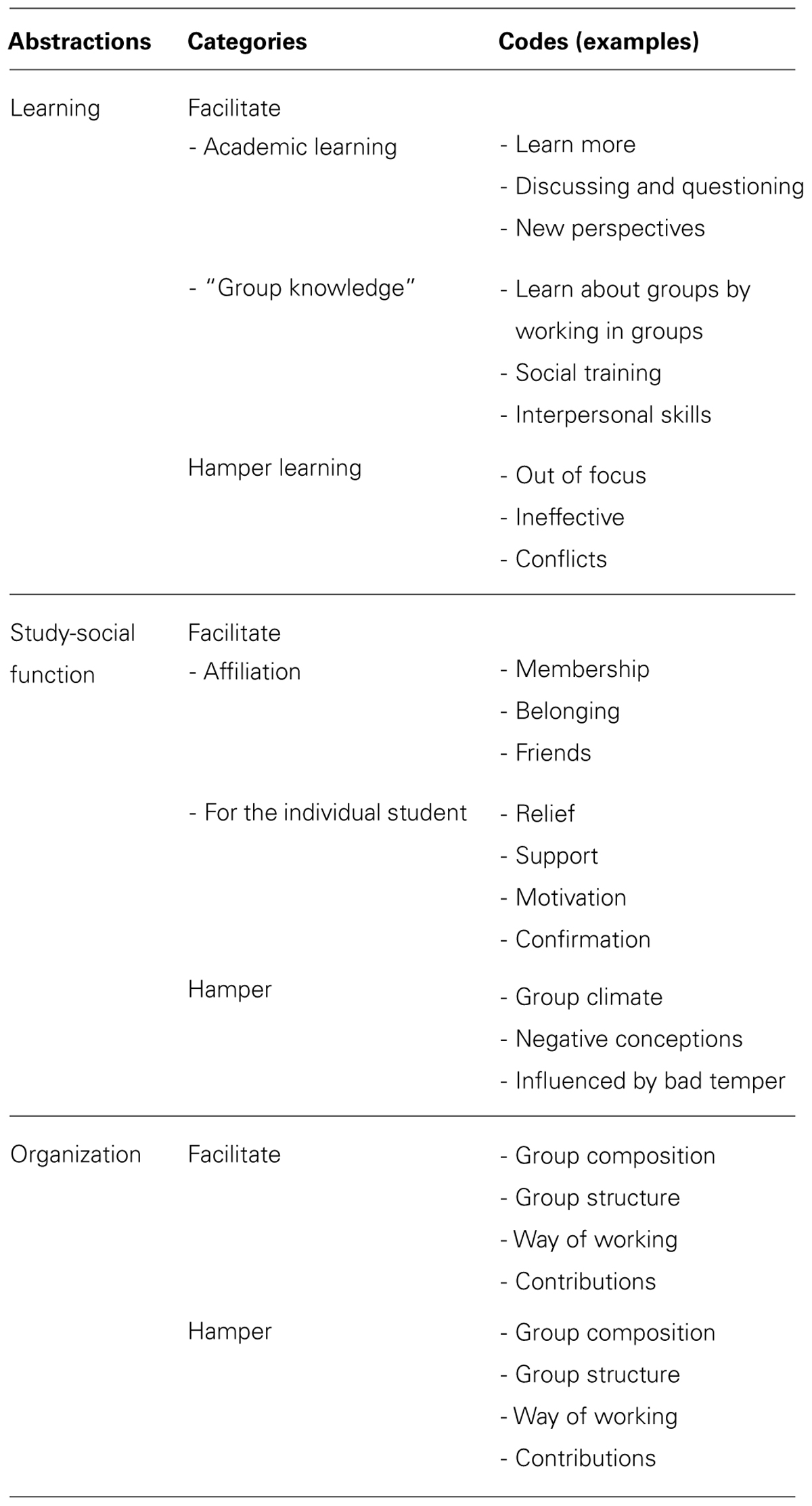

Group work is used as a means for learning at all levels in educational systems. There is strong scientific support for the benefits of having students learning and working in groups. Nevertheless, studies about what occurs in groups during group work and which factors actually influence the students’ ability to learn is still lacking. Similarly, the question of why some group work is successful and other group work results in the opposite is still unsolved. The aim of this article is to add to the current level of knowledge and understandings regarding the essence behind successful group work in higher education. This research is focused on the students’ experiences of group work and learning in groups, which is an almost non-existing aspect of research on group work prior to the beginning of the 21st century. A primary aim is to give university students a voice in the matter by elucidating the students’ positive and negative points of view and how the students assess learning when working in groups. Furthermore, the students’ explanations of why some group work ends up being a positive experience resulting in successful learning, while in other cases, the result is the reverse, are of interest. Data were collected through a study-specific questionnaire, with multiple choice and open-ended questions. The questionnaires were distributed to students in different study programs at two universities in Sweden. The present result is based on a reanalysis and qualitative analysis formed a key part of the study. The results indicate that most of the students’ experiences involved group work that facilitated learning, especially in the area of academic knowledge. Three important prerequisites (learning, study-social function, and organization) for group work that served as an effective pedagogy and as an incentive for learning were identified and discussed. All three abstractions facilitate or hamper students’ learning, as well as impact their experiences with group work.

Introduction

Group work is used as a means for learning at all levels in most educational systems, from compulsory education to higher education. The overarching purpose of group work in educational practice is to serve as an incentive for learning. For example, it is believed that the students involved in the group activity should “learn something.” This prerequisite has influenced previous research to predominantly focus on how to increase efficiency in group work and how to understand why some group work turns out favorably and other group work sessions result in the opposite. The review of previous research shows that in the 20th century, there has been an increase in research about students’ cooperation in the classroom ( Lou et al., 1996 ; Gillies and Boyle, 2010 , 2011 ). This increasing interest can be traced back to the fact that both researchers and teachers have become aware of the positive effects that collaboration might have on students’ ability to learn. The main concern in the research area has been on how interaction and cooperation among students influence learning and problem solving in groups ( Hammar Chiriac, 2011a , b ).

Two approaches concerning learning in group are of interest, namely cooperative learning and collaborative learning . There seems to be a certain amount of confusion concerning how these concepts are to be interpreted and used, as well as what they actually signify. Often the conceptions are used synonymously even though there are some differentiations. Cooperative group work is usually considered as a comprehensive umbrella concept for several modes of student active working modes ( Johnson and Johnson, 1975 ; Webb and Palincsar, 1996 ), whereas collaboration is a more of an exclusive concept and may be included in the much wider concept cooperation ( Hammar Chiriac, 2011a , b ). Cooperative learning may describe group work without any interaction between the students (i.e., the student may just be sitting next to each other; Bennet and Dunne, 1992 ; Galton and Williamson, 1992 ), while collaborative learning always includes interaction, collaboration, and utilization of the group’s competences ( Bennet and Dunne, 1992 ; Galton and Williamson, 1992 ; Webb and Palincsar, 1996 ).

At the present time, there is strong scientific support for the benefits of students learning and working in groups. In addition, the research shows that collaborative work promotes both academic achievement and collaborative abilities ( Johnson and Johnson, 2004 ; Baines et al., 2007 ; Gillies and Boyle, 2010 , 2011 ). According to Gillies and Boyle (2011) , the benefits are consistent irrespective of age (pre-school to college) and/or curriculum. When working interactively with others, students learn to inquire, share ideas, clarify differences, problem-solve, and construct new understandings. Gillies (2003a , b ) also stresses that students working together are more motivated to achieve than they would be when working individually. Thus, group work might serve as an incentive for learning, in terms of both academic knowledge and interpersonal skills. Nevertheless, studies about what occur in groups during group work and which factors actually influence the students’ ability to learn is still lacking in the literature, especially when it comes to addressing the students’ points of view, with some exceptions ( Cantwell and Andrews, 2002 ; Underwood, 2003 ; Peterson and Miller, 2004 ; Hansen, 2006 ; Hammar Chiriac and Granström, 2012 ). Similarly, the question of why some group work turns out successfully and other work results in the opposite is still unsolved. In this article, we hope to contribute some new pieces of information concerning the why some group work results in positive experiences and learning, while others result in the opposite.

Group Work in Education

Group work is frequently used in higher education as a pedagogical mode in the classroom, and it is viewed as equivalent to any other pedagogical practice (i.e., whole class lesson or individual work). Without considering the pros and cons of group work, a non-reflective choice of pedagogical mode might end up resulting in less desirable consequences. A reflective choice, on the other hand, might result in positive experiences and enhanced learning ( Galton et al., 2009 ; Gillies and Boyle, 2011 ; Hammar Chiriac and Granström, 2012 ).

Group Work as Objective or Means

Group work might serve different purposes. As mentioned above, the overall purpose of the group work in education is that the students who participate in group work “learn something.” Learning can be in terms of academic knowledge or “group knowledge.” Group knowledge refers to learning to work in groups ( Kutnick and Beredondini, 2009 ; Gillies and Boyle, 2010 , 2011 ; Hammar Chiriac, 2011a , b ). Affiliation, fellowship, and welfare might be of equal importance as academic knowledge, or they may even be prerequisites for learning. Thus, the group and the group work serve more functions than just than “just” being a pedagogical mode. Hence, before group work is implemented, it is important to consider the purpose the group assignment will have as the objective, the means, or both.

From a learning perspective, group work might function as both an objective (i.e., learning collaborative abilities) and as the means (i.e., a base for academic achievement) or both ( Gillies, 2003a , b ; Johnson and Johnson, 2004 ; Baines et al., 2007 ). If the purpose of the group work is to serve as an objective, the group’s function is to promote students’ development of group work abilities, such as social training and interpersonal skills. If, on the other hand, group work is used as a means to acquire academic knowledge, the group and the collaboration in the group become a base for students’ knowledge acquisition ( Gillies, 2003a , b ; Johnson and Johnson, 2004 ; Baines et al., 2007 ). The group contributes to the acquisition of knowledge and stimulates learning, thus promoting academic performance. Naturally, group work can be considered to be a learning environment, where group work is used both as an objective and as the means. One example of this concept is in the case of tutorial groups in problem-based learning. Both functions are important and might complement and/or even promote each other. Albeit used for different purposes, both approaches might serve as an incentive for learning, emphasizing different aspect knowledge, and learning in a group within an educational setting.

Working in a Group or as a Group

Even if group work is often defined as “pupils working together as a group or a team,” ( Blatchford et al., 2003 , p. 155), it is important to bear in mind that group work is not just one activity, but several activities with different conditions ( Hammar Chiriac, 2008 , 2010 ). This implies that group work may change characteristics several times during a group work session and/or during a group’s lifetime, thus suggesting that certain working modes may be better suited for different parts of a group’s work and vice versa ( Hammar Chiriac, 2008 , 2010 ). It is also important to differentiate between how the work is accomplished in the group, whether by working in a group or working as a group.

From a group work perspective, there are two primary ways of discussing cooperation in groups: working in a group (cooperation) or working as a group (collaboration; Underwood, 2003 ; Hammar Chiriac and Granström, 2012 ). Situations where students are sitting together in a group but working individually on separate parts of a group assignment are referred to as working in a group . This is not an uncommon situation within an educational setting ( Gillies and Boyle, 2011 ). Cooperation between students might occur, but it is not necessary to accomplish the group’s task. At the end of the task, the students put their separate contributions together into a joint product ( Galton and Williamson, 1992 ; Hammar Chiriac, 2010 , 2011a ). While no cooperative activities are mandatory while working in a group, cooperative learning may occur. However, the benefits in this case are an effect of social facilitation ( Zajonc, 1980 ; Baron, 1986 ; Uziel, 2007 ) and are not caused by cooperation. In this situation, social facilitation alludes to the enhanced motivational effect that the presence of other students have on individual student’s performance.

Working as a group, on the other hand, causes learning benefits from collaboration with other group members. Working as a group is often referred to as “real group work” or “meaningful group work,” and denotes group work in which students utilizes the group members’ skills and work together to achieve a common goal. Moreover, working as a group presupposes collaboration, and that all group members will be involved in and working on a common task to produce a joint outcome ( Bennet and Dunne, 1992 ; Galton and Williamson, 1992 ; Webb and Palincsar, 1996 ; Hammar Chiriac, 2011a , b ). Working as a group is characterized by common effort, the utilization of the group’s competence, and the presence of problem solving and reflection. According to Granström (2006) , working as a group is a more uncommon activity in an educational setting. Both approaches might be useful in different parts of group work, depending on the purpose of the group work and type of task assigned to the group ( Hammar Chiriac, 2008 ). Working in a group might lead to cooperative learning, while working as group might facilitate collaborative learning. While there are differences between the real meanings of the concepts, the terms are frequently used interchangeably ( Webb and Palincsar, 1996 ; Hammar Chiriac, 2011a , b ; Hammar Chiriac and Granström, 2012 ).

Previous Research of Students’ Experiences

As mentioned above, there are a limited number of studies concerning the participants’ perspectives on group work. Teachers often have to rely upon spontaneous viewpoints and indications about and students’ experiences of group work in the form of completed course evaluations. However, there are some exceptions ( Cantwell and Andrews, 2002 ; Underwood, 2003 ; Peterson and Miller, 2004 ; Hansen, 2006 ; Hammar Chiriac and Einarsson, 2007 ; Hammar Chiriac and Granström, 2012 ). To put this study in a context and provide a rationale for the present research, a selection of studies focusing on pupils’ and/or students’ experiences and conceptions of group work will be briefly discussed below. The pupils’ and/or students inside knowledge group work may present information relevant in all levels of educational systems.

Hansen (2006) conducted a small study with 34 participating students at a business faculty, focusing on the participants’ experiences of group work. In the study different aspects of students’ positive experiences of group work were identified. For example, it was found to be necessary that all group members take part and make an effort to take part in the group work, clear goals are set for the work, role differentiation exists among members, the task has some level of relevance, and there is clear leadership. Even though Hansen’s (2006) study was conducted in higher education, these findings may be relevant in other levels in educational systems.

To gain more knowledge and understand about the essence behind high-quality group work, Hammar Chiriac and Einarsson (2007) turned their focus toward students’ experiences and conceptions of group work in higher education. A primary aim was to give university students a voice in the matter by elucidating their students’ points of view and how the students assess working in groups. Do the students’ appreciate group projects or do they find it boring and even as a waste of time? Would some students prefer to work individually, or even in “the other group?” The study was a part of a larger research project on group work in education and only a small part of the data corpus was analyzed. Different critical aspects were identified as important incitements for whether the group work turned out to be a success or a failure. The students’ positive, as well as negative, experiences of group work include both task-related (e.g., learning, group composition, participants’ contribution, time) and socio-emotional (e.g., affiliation, conflict, group climate) aspects of group work. The students described their own group, as well as other groups, in a realistic way and did not believe that the grass was greener in the other group. The same data corpus is used in this article (see under Section The Previous Analysis). According to Underwood (2003) and Peterson and Miller (2004) , the students’ enthusiasm for group work is affected by type of task, as well as the group’s members. One problem that recurred frequently concerned students who did not contribute to the group work, also known as so-called free-riders ( Hammar Chiriac and Hempel, 2013 ). Students are, in general, reluctant to punish free-riders and antipathy toward working in groups is often associated with a previous experience of having free-riders in the group ( Peterson and Miller, 2004 ). To accomplish a favorable attitude toward group work, the advantages of collaborative activities as a means for learning must be elucidated. Furthermore, students must be granted a guarantee that free-riders will not bring the group in an unfavorable light. The free-riders, on the other hand, must be encouraged to participate in the common project.

Hammar Chiriac and Granström (2012) were also interested in students’ experiences and conceptions of high-quality and low-quality group work in school and how students aged 13–16 describe good and bad group work? Hammar Chiriac and Granström (2012) show that the students seem to have a clear conception of what constitutes group work and what does not. According to the students, genuine group work is characterized by collaboration on an assignment given by the teacher. They describe group work as working together with their classmates on a common task. The students are also fully aware that successful group work calls for members with appropriate skills that are focused on the task and for all members take part in the common work. Furthermore, the results disclose what students consider being important requisites for successful versus more futile group work. The students’ inside knowledge about classroom activities ended up in a taxonomy of crucial conditions for high-quality group work. The six conditions were: (a) organization of group work conditions, (b) mode of working in groups, (c) tasks given in group work, (d) reporting group work, (e) assessment of group work, and (f) the role of the teacher in group work. The most essential condition for the students seemed to be group composition and the participants’ responsibilities and contributions. According to the students, a well-organized group consists of approximately three members, which allows the group to not be too heterogeneous. Members should be allotted a reasonable amount of time and be provided with an environment that is not too noisy. Hence, all six aspects are related to the role of the teacher’s leadership since the first five points concern the framework and prerequisites created by the teacher.

Näslund (2013) summarized students’ and researchers’ joint knowledge based on experience and research on in the context of shared perspective for group work. As a result, Näslund noticed a joint apprehension concerning what constitutes “an ideal group work.” Näslund (2013) highlighted the fact that both students and researchers emphasized for ideal group work to occur, the following conditions were important to have: (a) the group work is carried out in supportive context, (b) cooperation occurs, (c) the group work is well-structured, (d) students come prepared and act as working members during the meetings, and (e) group members show respect for each other.

From this brief exposition of a selection of research focusing on students’ views on group work, it is obvious that more systematic studies or documentations on students’ conceptions and experiences of group work within higher education are relevant and desired. The present study, which is a reanalysis of a corpus of data addressing the students’ perspective of group, is a step in that direction.

Aim of the Study

The overarching knowledge interest of this study is to enhance the body of knowledge regarding group work in higher education. The aim of this article is to add knowledge and understanding of what the essence behind successful group work in higher education is by focusing on the students’ experiences and conceptions of group work and learning in groups , an almost non-existing aspect of research on group work until the beginning of the 21st century. A primary aim is to give university students a voice in the matter by elucidating the students’ positive and negative points of view and how the students assess learning when working in groups. Furthermore, the students’ explanations of why some group work results in positive experiences and learning, while in other cases, the result is the opposite, are of interest.

Materials and Methods

To capture university students’ experiences and conceptions of group work, an inductive qualitative approach, which emphasizes content and meaning rather than quantification, was used ( Breakwell et al., 2006 ; Bryman, 2012 ). The empirical data were collected through a study-specific, semi-structured questionnaire and a qualitative content analysis was performed ( Mayring, 2000 ; Graneheim and Lundman, 2003 ; Elo and Kyngäs, 2007 ).

Participants

All participating students attended traditional university programs where group work was a central and frequently used pedagogical method in the educational design. In addition, the participants’ programs allowed the students to be allocated to the same groups for a longer period of time, in some cases during a whole semester. University programs using specific pedagogical approaches, such as problem-based learning or case method, were not included in this study.

The participants consisted of a total of 210 students, 172 female and 38 male, from two universities in two different cities (approximately division: 75 and 25%). The students came from six different populations in four university programs: (a) The Psychologist Program/Master of Science in Psychology, (b) The Human Resource Management and Work Sciences Program, (c) Social Work Program, and (d) The Bachelor’s Programs in Biology. The informants were studying in their first through eighth terms, but the majority had previous experiences from working in other group settings. Only 2% of the students had just started their first term when the study was conducted, while the vast majority (96%) was participating in university studies in their second to sixth semester.

The teacher most frequently arranged the group composition and only a few students stated that they have had any influence on the group formation. There were, with a few exceptions, between 6 and 10 groups in each of the programs included in this study. The groups consisted of between four to eight members and the differences in sizes were almost proportionally distributed among the research group. The groups were foremost heterogeneous concerning gender, but irrespective of group size, there seems to have been a bias toward more women than men in most of the groups. When there was an underrepresented sex in the group, the minority mostly included two students of the same gender. More than 50% of the students answered that in this particularly group, they worked solely with new group members, i.e., students they had not worked with in previous group work during the program.