Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing

- > Volume 1 Issue 1

- > The importance of financial literacy and its impact...

Article contents

Introduction, the overarching value of financial literacy, using financial instruments: from mortgages to crypto assets, financial education in school and the workplace, concluding remarks, the importance of financial literacy and its impact on financial wellbeing.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2023

In this editorial, we provided an overview of the papers in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing. They cover topics that are at the center of academic research, from the effects of financial education in school and the workplace to the importance of financial literacy for the macro-economy. They also cover financial inclusion and how financial literacy can promote the use of basic financial instruments, such as bank accounts. Moreover, they cover financial decision making in the context of complex instruments, such as mortgages, reverse mortgages, and crypto assets. The papers all share similar findings: financial literacy is low and often inadequate for making the types of financial decisions that are required today. Moreover, financial literacy is particularly low among already vulnerable groups. Importantly, financial literacy matters: it helps people make savvy financial decisions, including being less influenced by framing, better understand information that is provided to them, better understand the workings of insurance, and being more comfortable using basic financial instruments. In a nutshell, financial literacy improves financial wellbeing.

Financial literacy is an essential skill for making savvy financial decisions, understanding the world around us, and being a good citizen. Changes in the pension system, the increasing complexity of financial instruments (including new instruments such as crypto assets), inflation, and increased risks (from the war in Ukraine to climate change) are some of the reasons behind the increasingly urgent need for individuals to have the knowledge and skills that will increase their financial resilience and wellbeing. The OECD Recommendation on Financial Literacy, adopted in 2020, recognized financial wellbeing as the ultimate goal of financial literacy. Footnote 1

Despite this urgency, levels of financial literacy are remarkably low, even in countries with well-developed financial markets and in which individuals actively participate in financial markets. According to the latest OECD adult financial literacy survey, financial literacy is low in many of the countries belonging to the G7 and G20 bloc. This aligns with findings from a global survey on financial literacy that showed that only a handful of countries rank high on very basic measures of financial literacy. Footnote 2 , Footnote 3 Not only is financial illiteracy widespread in the population, but it is particularly acute in some demographic sub-groups that are already financially vulnerable, such as women and those with low-income and low-educational attainment. Footnote 4

Financial literacy is also low among high school students, indicating that the next generation of adults is ill equipped to face the challenges and changes that are ahead of them. According to the latest wave of the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in some G7 countries, such as Italy, about 20 percent of students do not have basic proficiency in financial literacy. In other countries, such as Peru or Brazil, that proportion is higher than 40 percent. Footnote 5

Much research has been done so far, from measuring financial literacy to assessing the effectiveness of financial education programs to evaluating the link between financial literacy and behavior and the impact of financial literacy on individuals as well as the macro-economy. The number of papers on financial literacy has increased exponentially over the past decade. Footnote 6 Financial literacy has become an official field of study, with its own Journal of Economic Literature code (G53). For all of these reasons, it was time to have an academic journal dedicated to financial literacy. Its mission is to provide the most rigorous research to advance knowledge and to inform policy and programs.

The inaugural issue of the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing covers topics that are at the center of academic research, from the effects of financial education in school and the workplace to the importance of financial literacy for the macro-economy. It also covers financial inclusion and how financial literacy can promote the use of basic financial instruments, such as bank accounts. Moreover, it covers financial decision making in the context of complex instruments, such as mortgages, reverse mortgages, and crypto assets.

Because the authors of the papers in this inaugural issue have done a vast amount of work on the topics under consideration, we have asked them, when possible, to provide an overview of their work so to gain a perspective of what we have learned so far and what are the most fruitful directions for future research.

There are three principles that bring all of these papers and topics together. First, financial literacy’s relevance at the global level: it affects all countries and economies, irrespective of levels of economic development. The papers in this issue cover experiences from Peru, the United States, Canada, Australia, India, and Sub-Saharan African countries, among many others. When it comes to financial literacy, we can learn from many countries around the world, and the issues discussed in these papers are strikingly similar. Second, whether we are considering the use of basic financial instruments such as bank accounts, or complex ones such as crypto assets, skills are needed if they are to be used to minimize risk and maximize benefits. Third, improving the effectiveness of financial education requires effort as well as ingenuity, and one of the things we can learn from many of these works is how policy and programs can be improved with the help of research. For example, given that financial education in school can affect parents in addition to children, it might make sense to involve parents more directly in financial education programs in school. And because people require support to use financial instruments, attention should be paid to how the use of technology can be improved or can be better complemented with financial education.

In the following sections, we provide a brief description of the papers that are part of the inaugural issue and what we can learn from them.

The benefits of financial education can be far reaching. For example, there has been a push around the world, and significantly in the G20 countries, for promoting financial inclusion. Footnote 7 A high proportion of people in many emerging economies do not have easy access to even basic assets such as bank accounts, let alone access to financial markets, including the stock market. If finance can be important for growth, so is financial literacy, as it can promote participation in financial markets and savvy use of financial instruments. And as financial markets become more sophisticated, the ability to take advantage of new investment opportunities can help reduce inequality (Lo Prete Reference Lo Prete 2013 ).

But there is another important and under-explored avenue related to the impact of financial literacy, which is whether and how much policy makers can be successful in implementing economic reforms. Like individual financial decisions, many reforms involve a trade-off between a sacrifice today for a benefit in the future. However, if people have low financial literacy, they may fail to appreciate future benefits or may not be fully aware of the workings of government budgets and of institutions such as Social Security and the pension system. Overall, attempts to reform pension systems have been met with sharp opposition, even in the face of increasing longevity, decreasing birth rates, and other changes that put existing systems on potentially unsustainable paths. Can financial literacy help with the implementation of those reforms, thus improving the performance of an economy in the long term? And how important is knowledge of pensions?

These are some of the questions pursued by Fornero and Lo Prete ( Reference Fornero and Lo Prete 2023 ). The authors have not just done pioneering work in this area, but Professor Fornero implemented a sweeping reform of the Italian pension system when she served as the Minister of Labour, Social Policy and Gender Equality in Italy from November 2011 to April 2013. They first make the case that it is very important to improve pension literacy, both because there have been many changes to pension systems and because there are a lot of complexities in those systems. Better pension literacy can, for example, help people plan better for their own retirement. This can be particularly important for women, who live longer than men, have lower labor market attachment due to childbearing and other household responsibilities, and have lower wages. As the authors argue, the level of pension literacy is still very low and is particularly low among women, both of which are factors that can jeopardize retirement security.

Most importantly, the authors investigate whether financial literacy helps in the implementation of pension reforms. They report promising evidence that populations with a higher average level of financial literacy are less likely to punish governments for implementing reforms. And financial literacy can help individuals be better citizens (and more educated voters) and less likely to suffer from fiscal illusion, i.e., voters’ failure to estimate the (net) cost of a tax reduction (in terms of higher debt and/or the lower provision of public goods and services). According to their paper, financial literacy can also impact electoral participation, which is another good outcome for the workings of democracies.

It may be useful to note that the countries that started financial literacy programs or were the first to create national strategies for financial literacy did so because of their focus on the pension system and changes in pensions. The focus has now expanded to other topics, but pensions remain an important area of interest. And more than 80 countries have or are implementing national strategies for financial literacy, i.e., policy makers as well have acknowledged the importance of financial literacy at the national level.

Continuing on the topic of the global economy and pioneering work, if we want to have a good understanding of how finance and the use of financial instruments can be important for the wellbeing of individuals and the economy at large, we need to turn to the World Bank Global Findex. It is the most comprehensive database on financial inclusion; the data, which are collected directly from users of financial services, provide unique information on how adults save, borrow, make payments, and manage financial risks. Findings are sobering. The paper by Ansar et al. ( Reference Ansar, Klapper and Singer 2023 ) reminds us that, as of 2021, as many as 1.4 billion adults – or 24 percent of adults – worldwide are without even the most basic asset, i.e., a financial account, or are unbanked . Interestingly, the characteristics of those without an account are very similar to those with low financial literacy: women, poor adults, less educated adults, young adults, and those living in rural areas.

We can learn a lot from looking at the reasons why people do not have an accounts, which speaks to the importance of collecting these types of data. Specifically, the data show that a sizable number of respondents cite lack of help or being uncomfortable using an account as a reason for being unbanked. In developing countries, 64 percent of unbanked adults said they could not use an account at a financial institution without help, a proportion that becomes higher among women and other vulnerable groups. This finding is further evidence that we cannot underestimate the difficulties in using financial instruments. And even those who have an account do not always make good use of it. For example, in India – where every adult with an Aadhaar biometric ID was de facto given a no-minimum-balance, no-fee accounts account as part of the government’s Jan Dhan Yojana program – it was found that many accounts were dormant or had little or no activity. Inactive account holders in India often cite their discomfort level with financial services among the top barriers to account usage. Specifically, about 30 percent of inactive account holders do not use their account because they do not feel comfortable doing so by themselves. And looking at a subsample of 25 Sub-Saharan African countries, where mobile money accounts are widespread, the paper reports that 31 percent of mobile money account holders cannot use their account without help.

These data point to an opportunity for financial education. Strengthening financial literacy can result in more efficient and effective use of basic financial instruments.

Given that the use and good management of basic financial instruments, such as bank accounts, presents difficulty for many people, more complex financial instruments pose an even greater challenge, especially in the context of accelerated digitalization of financial services, which brings new risks for consumers (OECD 2018 ).

We were particularly interested in behavior related to mortgages because the home is the most important asset for most families. Choosing a suitable mortgage is therefore critical to financial wellbeing and, if the financial crisis of 2007/2008 is any indicator, a poor mortgage choice can be a major source of financial distress.

The paper by Torp et al. ( Reference Torp, Liu, Agnew, Bateman, Eckert and Iskhakov 2023 ) helps us to shed light on decisions related to mortgages. In a series of randomly assigned tasks, the authors assessed participants’ subjective comfort with a range of home loan amounts, framed as lump sum debts or equivalent repayment streams. Does framing matter when it comes to decisions about mortgages and does financial literacy and broker advice help? It is not easy to translate stocks into a flow of payments, but often individuals must do so when making financial decisions. As mentioned earlier, high levels of financial literacy cannot be taken for granted, even among the G20 countries. Like other papers in this issue, the authors measure financial literacy using the Big Three financial literacy questions, which assess knowledge of basic financial concepts related to interest rates, inflation, and risk diversification, which are essential elements of financial decisions, including mortgage choice. Less than half of the participants in their sample, i.e., people age 25–64 who have bought or are interested in buying a house, are able to answer these questions.

Similar to findings in other contexts, for example, pension wealth, the authors found that borrowers are less comfortable when loans are framed as lump sum debts rather than equivalent repayment streams. Borrowers are also less adept at translating repayment streams into equivalent lump sums. Interestingly, financial literacy tends to make borrowers more cautious and less comfortable with debt in general and less sensitive to framing. Also, financially literate borrowers can match liabilities with servicing burdens, a key component of sound mortgage management.

Turning to the people who have consulted mortgage brokers, they report higher levels of comfort with debt in general and less discomfort with lump sums compared to repayment streams. Brokers also seem to help clients better grasp the link between loan amounts and repayments. After accounting for potential endogeneity, the authors’ found that, while brokers increase people’s confidence and probably improve their understanding of home loans, they also appear to influence clients’ comfort with debt.

This paper sheds light on the potential effects of financial education: when it comes to household mortgage decisions, financial education can reduce mortgage stress by inducing caution in borrowers and reducing susceptibility to framing. It may also help in using the services of brokers to the household’s advantage.

And given that the house is such a major asset in a household’s balance sheet, what to do with it (including after retirement) is also an important decision. Specifically, do people understand reverse mortgages and does financial literacy help in dealing with these products, which can be even more complex than standard mortgages?

The paper by Choinière-Crèvecoeur and Michaud ( Reference Choinière-Crèvecoeur and Michaud 2023 ) aims to understand the interplay between financial literacy and the valuation of reverse mortgage products. As explained in the paper, a reverse mortgage is a financial product that allows a homeowner to convert a portion of the current equity of their principal residence into cash. Unlike many other mortgage products, the borrower is not obligated to make payments before moving out, selling, or dying. In addition, the borrower is insured against the risk that the loan will be worth more than the house when it is sold. This is called the no-negative equity guarantee (NNEG) of the reverse mortgage. This feature means that the borrower’s longevity risk, as well as the risk of a decline in house prices, is transferred to the lender.

As the definition of the product makes clear, the valuation of reverse mortgages is complex. Specifically, the insurance value of the NNEG is likely to be quite difficult to grasp and compute. It involves projecting house prices in the future, survival risk, and other considerations, such as when one expects to sell the house. Consumers with limited financial literacy may have a harder time making sense of the price and value of the products offered.

To understand how consumers value reverse mortgages, the authors conducted an experiment in which respondents were offered different reverse mortgage products and had to evaluate them by giving their probability of buying each product within the next year. The authors investigate how financial literacy as well as prior knowledge of reverse mortgages shapes the evaluation of reverse mortgage products, in particular the actuarial value of the NNEG and the interest rate charged.

In their sample of 55- to 75-year-old respondents living in the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia, the authors find that more than half of eligible Canadians (55.5%) lack a basic knowledge of reverse mortgages. Moreover, only a little more than half of the respondents in the sample (54.1%) could correctly answer the Big Three questions, indicating that financial literacy is low even among older respondents, who have presumably made many financial decisions.

The findings from this paper show that the effect of financial literacy goes beyond simply increasing or decreasing the likelihood of purchasing a product. In some instances, such as with reverse mortgages, financial literacy enables respondents to better evaluate and assess the value of financial products. Consistent with many other papers, the empirical work in this paper also makes clear that insurance is a hard concept for households to understand, particularly when it involves complex risk calculations. More research should be devoted to understanding how financial education may help households better grasp concepts related to risk and insurance.

Crypto assets are another complex product, and one that is likely to be at least as hard to understand as insurance. Ownership of crypto assets is increasingly rapidly across countries, particularly among the young, which is why we are particularly interested in learning more about decisions related to new and risky products.

A very interesting hypothesis often mentioned in the general media, and pursued in the paper by Gerrans et al. ( Reference Gerrans, Babu Abisekaraj and Liu 2023 ), is that given the rapid increase in the price of crypto over time, people have fear of missing out, or FoMO, on the earnings that can result from crypto ownership. The field of behavioral finance has documented that emotions, attitudes, and behavioral biases can play an important role in financial decisions and the authors build on that field and the literature examining differences in psychological status and personality between investors and non-investors.

The analysis is carried out on data from a survey of undergraduate students at the University of Western Australia as part of a program examining the financial literacy of young adults, including students who enroll in an elective personal finance unit. The survey was conducted in the last week of July 2021, when crypto and stock prices had risen substantially in the 12 months prior to the survey. The relevance of FoMO is considered in addition to financial literacy and important preference parameters, such as risk tolerance. The authors look at both the direct effect of FoMo and the indirect effect of financial literacy and risk tolerance.

Estimates from a simple investment model identify a significant role for FoMO, along with financial literacy and risk tolerance, in current and future investment intentions related to both stocks and crypto. Interestingly, FoMO effects are largest for crypto and future investment intentions and smallest for current stock investment. While risk tolerance and financial literacy have positive effects for current crypto investment, these effects are small and smaller than the effects of FoMO. Financial literacy retains a significant small effect for future stock investment but not for crypto. Risk tolerance and financial literacy have larger effects than FoMO on current ownership of stocks. Thus, factors beyond those traditionally considered in investment models can play a role when looking at new and complex assets.

In addition to direct effects, financial literacy has an indirect effect on investment via FoMO, suggesting that FoMO has some basis in knowledge, though this is a small effect and only robust for stocks. Financial literacy is a significant predictor of FoMO for stocks but only weakly for crypto. Moreover, FoMO is a significant positive predictor of risk tolerance, though the estimated effect is not economically meaningful. Interestingly, FoMO explains only a small amount of gender difference in current crypto ownership, and it does not significantly explain observed gender difference for stock ownership.

As discussed at the end of the paper, the authors are agnostic on whether FoMO is good or bad. To the extent that non-participation in stock markets is a mistake, FoMO may serve a positive role. Given positive associations (although small) between financial literacy and FoMO for stocks, interventions directly addressing FoMO may be useful. For crypto as well, interventions that tap into FoMO could have some effects.

More than ever, the promotion of financial literacy is important; it is particularly important among the young, as it will help them make savvy decisions about very risky assets, such as crypto.

While financial literacy is an essential skill, particularly among the young, many young people lack knowledge of basic financial concepts. Back in 2000, the OECD started PISA, an ambitious project to assess student performance in critical areas. PISA gauges whether students are prepared for future challenges, whether they can analyze, reason, and communicate effectively, and whether they have the capacity to continue learning throughout their lives. Since its first wave in 2000, PISA has tested 15-year-old students’ skills and knowledge in three key domains: mathematics, reading, and science. In 2012, PISA introduced an optional financial literacy assessment, which became the first large-scale international study to assess youths’ financial literacy. The PISA financial literacy assessment measures the proficiency of 15-year-olds in demonstrating and applying financial knowledge and skills.

This is the definition of financial literacy from the team of experts who worked on this assessment Footnote 8 :

“Financial literacy is knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, as well as the skills and attitudes to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial wellbeing of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life . ” ( OECD 2019b )

As reported in more detail in Lusardi ( Reference Lusardi 2015 ), there are four innovative aspects of this definition that should be highlighted. First, financial literacy does not refer simply to knowledge and understanding but also to its purpose, which is to promote effective decision making. Second, and in line with the objectives of this journal, the aim of financial literacy is to improve financial wellbeing, not to affect a single behavior, such as increasing saving or decreasing debt. Third, financial literacy has effects not just for individuals but for society as well. Fourth, financial literacy, like reading, writing, and knowledge of science, enables young people to participate in economic life. We highlight this definition because it represents many of the principles covered in this inaugural issue.

The PISA financial literacy data have become a critical source of information with which to assess the level of financial literacy among the young. Starting from the original wave in 2012, we have found that several rich countries do not have high levels of youth financial literacy. For example, both the United States and some European countries, such as Italy, France, and Spain, ranked at the OECD average or below the average on the 2012 financial literacy scale. Moreover, and importantly, financial literacy is strongly linked to socio-economic status: the students who are financially literate are disproportionately those from families with higher levels of education and income and from homes with a lot of books. (OECD 2014 ; Lusardi Reference Lusardi 2015 ).

The PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment will provide further insights into young people’s financial literacy across 23 countries and economies, and take into consideration changes in the socio-demographic and financial landscape, such as the use of digital services, that are relevant for students’ financial literacy and decision making.

Countries have started to add financial education in school, in some cases making it mandatory. Notably, Portugal made financial education mandatory in school in 2018, adding it to the civic education curriculum, and many states in the United States have passed legislation to make financial education mandatory in high school curricula. Recent empirical evidence on the effectiveness of financial education in school shows it holds much promise. For example, according to a meta-analysis covering financial education programs from as many as 33 countries on 6 continents, and considering the programs evaluated most rigorously, financial education is found to affect both financial knowledge and downstream behavior. Remarkably, the effects are similar across age groups, i.e., they hold among the young and the old, and they hold across countries. Footnote 9 Other work examining the effect of financial education in high school also shows that young people who were exposed to high school financial education are much less likely to have problems with debt as young adults (Urban et al. Reference Urban, Schmeiser, Collins and Brown 2020 ).

While the focus on financial education has been on whether it improves the knowledge and wellbeing of students, it could also affect others. Frisancho ( Reference Frisancho 2023 ) in this inaugural issue examines whether financial education in high school can also affect parents. This is a very innovative paper and for many reasons. First, the analysis is carried out on a large sample of schools in Peru. As mentioned earlier, Peru is a country with a high percentage of students who perform poorly on financial literacy assessments. Second, it is possible to link the data with information from credit bureau records, which provide data on financial outcomes. This is more rigorous information than can be obtained by relying, for example, on self-reports. Third and importantly, the evaluation is based on a large-scale experiment, where students were randomly assigned to control and treatment groups, which is the most rigorous method with which to assess the impact of financial education. We hope many programs can be evaluated using these methods and that this study can provide guidelines for other countries.

The findings speak of the power of financial education: in addition to affecting students, it helps parents, specifically parents of low-income students. Among parents from poorer households, default probabilities decrease, credit scores increase, and debt levels increase too. And there is an important gender effect: it is mostly the parents of daughters who experience improvement in their financial behaviors. These findings are intrinsically important and have policy implications: Financial education in school can be far reaching and can have important spillover effects, in particular for vulnerable groups.

And if schools can be suitable places to provide financial education to the young, the workplace can be ideal for financial education programs for adults, as also recognized by the OECD in the Policy Handbook on Financial Education in the Workplace (OECD 2022 b). There are many reasons why workplace financial education can be important. First, employers may benefit too. A simple statistic from the work of Hasler et al. ( Reference Hasler, Lusardi, Yagnik and Yakobski 2023 ) is quite informative. In an attempt to provide a crude proxy of the cost of financial illiteracy, the 2021 Personal Finance Index ( P-Fin Index) survey asks respondents to give an estimate of the total number of hours per week they spend worrying about their personal finances, and how many of those hours are spent at work. Findings are startling. In 2021, U.S. adults reported spending about 7 hours per week, on average, thinking about and dealing with issues and problems related to their personal finances, with over three of these hours spent at work. The most financially literate respondents (who answered over 75 percent of the P-Fin Index questions correctly) reported spending much less time dealing with their personal finances: about three total hours per week with 1 hour per week at work. In contrast, the least financially literate respondents (those who answered 25 percent or less of the P-Fin Index questions correctly) reported spending a staggering 11 total hours per week and over 4 hours per week at work thinking about and dealing with issues related to their finances.

Hasler et al. ( Reference Hasler, Lusardi, Yagnik and Yakobski 2023 ) use these data to do a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the return to a workplace financial education program. For a company with 30 minimum-wage employees (earning $15 per hour) who work 50 weeks per year, financial education can recover $22,500 of value per year for an employer, which is conceivably greater than the cost of many workplace financial wellness programs. In other words, scalable, low-cost financial education programs would likely create a positive return on investment, in particular for large employers.

Because of the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution in the United States, a number of large firms have started to offer financial education programs. However, it is difficult to access that data without working directly with an employer. It is also difficult to acquire data that are representative of the population of workers or employers. The research of Clark ( Reference Clark 2023 ), who has worked with many employers in different sectors, is rather unique and helps us to shed light on the workings and promises of workplace financial education. As noted in his paper, providing financial education when workers are first hired is ideal, because it is in the interest of both employers and employees to understand the benefits offered by the firm and how to best use them. Providing education related to retirement and retirement planning is also beneficial to both parties, given that a substantial portion of employer benefits relate to pensions and the promotion of financial security in retirement. However, as the author effectively argues, financial education should not be limited to retirement topics, as other financial decisions made by employees can interact with decisions about whether or not to participate in pension plans and how much to contribute to those plans. Holistic financial education programs offered throughout the life cycle may better fit the needs of a heterogeneous population of workers. And programs provided well before retirement may enable workers to take better advantage of the power of interest compounding, helping them begin to save as early as possible and take advantage of employer matches. It is not always possible to evaluate the effectiveness of programs using randomized controlled trials or controlling for certain factors, such as whether program attendees are those who are inherently interested in financial education, but the evidence provided in this overview of two decades of work shows that workplace financial education holds much promise.

Clark’s work has included personal interactions with employers and employees, providing opportunities for both quantitative and qualitative work, and the evidence from small samples can be illuminating too. For example, the author shows that financial education programs are appreciated and rated with high marks by employees. While self-selection may play a role in program attendance, offering this type of benefit can be a useful retention tool, particularly in the tight post-pandemic labor market. We specifically encourage reading the last part of the paper, which provides useful best practices for increasing the effectiveness of employer-provided financial education programs.

The papers in this inaugural issue all share similar findings: financial literacy is low and often inadequate for making the types of financial decisions that are required today, from opening a bank account, to managing a mortgage, to using reverse mortgages later in life, to investing in new and risky assets such as crypto. Moreover, financial literacy is particularly low among already vulnerable groups, such as women and individuals with low-income or low-educational attainment. Importantly, financial literacy matters: it helps people make savvy financial decisions, including being less influenced by framing, better understand information that is provided to them, better understand the workings of insurance, and being more comfortable using basic financial instruments. In a nutshell, financial literacy improves financial wellbeing! The effects of financial literacy extend beyond individuals: financial literacy can affect the macro-economy as well.

Financial literacy is essential for the promotion of financial inclusion, as people need knowledge and skills to effectively use financial instruments, even the most basic ones, such as bank accounts. Every financial instrument carries potential costs and risks, and some basic knowledge is necessary to use these instruments well. And when financial instruments are complex (as in the case of mortgages, including reverse mortgages) or risky (as in the case of assets such as crypto), financial literacy becomes a must for informed consumer use along with adequate financial protection.

Financial literacy is also expected to help individuals deal with emerging trends and challenges in the financial landscape, from digital financial services to sustainable finance, as recognized in the priorities of the OECD International Network on Financial Education for the next biennium.

Policy makers, practitioners, the private and public sectors, and academics can benefit from the findings reported in the papers in this inaugural issue. Our objective is to publish the most rigorous and relevant work. But most importantly, we hope that this journal will become a source for relevant information and that the research that is published here will have an impact and improve the financial wellbeing of individuals around the world.

1 See OECD ( 2020 a).

2 See OECD ( 2020 b) and Klapper and Lusardi ( Reference Klapper and Lusardi 2020 ).

3 The OECD will release the results of a new data collection in 2023 from developed and developing countries, which will look not only at financial literacy but also at the financial resilience and financial wellbeing of consumers around the world in an internationally comparable way (OECD 2022 a).

4 See Lusardi and Mitchell ( Reference Lusardi and Mitchell 2014 ) for a discussion and review of the empirical evidence on financial literacy.

5 See OECD ( 2020 c). The next PISA financial literacy assessment will be released in 2024.

6 See Kaiser et al. ( Reference Kaiser, Lusardi, Menkhoff and Urban 2022 ).

7 See the G20 High-Level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion ( 2016 ).

8 Lusardi and Messy both participated in the work leading to this assessment.

9 See Kaiser et al. ( Reference Kaiser, Lusardi, Menkhoff and Urban 2022 ).

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 1, Issue 1

- Annamaria Lusardi (a1) and Flore-Anne Messy (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2023.8

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

A Reflection on the Research Brief: Financial Education Matters

April 21, 2022

Testing the Effectiveness of Financial Education Across 76 Randomized Experiments

Dr. billy hensley, president and ceo, national endowment for financial education (nefe) gerri walsh, president, finra investor education foundation.

Does financial education work? In other words, does building and improving foundational knowledge about money help people make better decisions and lead to better financial outcomes? Four prominent scholars recently came together to seek answers.

The FINRA Investor Education Foundation (FINRA Foundation), the National Endowment for Financial Education® (NEFE®) and the study’s authors collaborated to elevate this research through the brief Financial Education Matters: Testing the Effectiveness of Financial Education Across 76 Randomized Experiments, which can be found on both the FINRA Foundation and NEFE websites. This brief is an important milestone for our community and merits the attention of teachers, researchers and anyone who advocates for financial education.

The research clearly shows that financial education is a cost-effective way to increase financial knowledge and improve a host of behaviors related to budgeting, saving, credit, insurance and more. In fact, its impact is comparable to that of core school curricula and diverse programs, such as smoking cessation efforts, that help individuals manage personal issues.

Financial education cannot solve every challenge in people’s financial lives. Rather, it is just one, albeit critical, component of the Personal Finance Ecosystem . We believe a combination of effective legislation, regulation, consumer-friendly choices, and efforts to expand inclusion and equity also are required to foster financial well-being. However, this new meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that financial education is very much part of the solution. When properly administered, financial education can improve people’s lives and communities—both directly and indirectly. The challenge is to meet a growing demand for financial education and ensure that it keeps pace with the changes in our financial world.

The study used meta-analysis, a stringent research technique, to evaluate the effectiveness of financial education in its many forms—in the classroom, at the workplace and other situations where lessons about money intersect with people’s daily lives. The researchers examined results from scores of independent studies across 33 countries. All of these studies asked the same underlying question: “Is financial education effective?”

The results from the different studies were aggregated and subjected to rigorous statistical analysis to draw a single, overarching conclusion about financial education. But the question remains: “How trustworthy are the 76 experiments that comprised the larger study?”

Notably, the researchers only evaluated experimental studies that used randomized control trials, which are the most reliable form of scientific research. The experiments in the meta-analysis tested whether an educational intervention was effective by comparing people who received the education (the treatment group) to people who did not (the control group). To reduce bias, participants were placed in each of these groups at random, that is, by chance. This allowed researchers to draw conclusions about whether financial education actually causes improvements in financial knowledge and behavior.

The FINRA Foundation and NEFE aim to elevate rigorous, scholarly work and support research that illuminates the need for inclusive and quality financial education interventions and policies. Advancements in financial education research over the past eight years have been impressive and essential. The recent study continues that trend and helps to make future research all the more consequential.

We applaud the pioneering work examined in the meta-analysis. Looking ahead, we are confident new studies will emerge that further our understanding of how financial education shapes people’s knowledge and decisions about money. In time, researchers will replicate the meta-analysis, and the field will coalesce around meticulous standards for how we can most effectively deliver financial education, while demonstrating its value in helping all Americans improve their financial well-being.

September 05, 2024

Successes of Grassroots, Native-led Financial Education

The power of Native-led financial education as traditional wisdom meets modern finance to uplift and empower Native communities.

Respect Legislative Intent with Youth Financial Education Requirements

August 19, 2024

Are high schools giving students and educators the tools they need? Dive into the discussion of the importance of implementing stand-alone financial education courses in high schools to ensure students receive comprehensive and equitable financial literacy.

August 16, 2024

Passing Legislation Is Just the Beginning: A 2024 Legislative Review of K-12 Financial Education Requirements

Our 2024 legislative review reveals key state-by-state progress and setbacks in financial literacy requirements around the United States.

- Conference key note

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2019

Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications

- Annamaria Lusardi 1

Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics volume 155 , Article number: 1 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

433k Accesses

335 Citations

216 Altmetric

Metrics details

1 Introduction

Throughout their lifetime, individuals today are more responsible for their personal finances than ever before. With life expectancies rising, pension and social welfare systems are being strained. In many countries, employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans are swiftly giving way to private defined contribution (DC) plans, shifting the responsibility for retirement saving and investing from employers to employees. Individuals have also experienced changes in labor markets. Skills are becoming more critical, leading to divergence in wages between those with a college education, or higher, and those with lower levels of education. Simultaneously, financial markets are rapidly changing, with developments in technology and new and more complex financial products. From student loans to mortgages, credit cards, mutual funds, and annuities, the range of financial products people have to choose from is very different from what it was in the past, and decisions relating to these financial products have implications for individual well-being. Moreover, the exponential growth in financial technology (fintech) is revolutionizing the way people make payments, decide about their financial investments, and seek financial advice. In this context, it is important to understand how financially knowledgeable people are and to what extent their knowledge of finance affects their financial decision-making.

An essential indicator of people’s ability to make financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aptly defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life. Thus, financial literacy refers to both knowledge and financial behavior, and this paper will analyze research on both topics.

As I describe in more detail below, findings around the world are sobering. Financial literacy is low even in advanced economies with well-developed financial markets. On average, about one third of the global population has familiarity with the basic concepts that underlie everyday financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). The average hides gaping vulnerabilities of certain population subgroups and even lower knowledge of specific financial topics. Furthermore, there is evidence of a lack of confidence, particularly among women, and this has implications for how people approach and make financial decisions. In the following sections, I describe how we measure financial literacy, the levels of literacy we find around the world, the implications of those findings for financial decision-making, and how we can improve financial literacy.

2 How financially literate are people?

2.1 measuring financial literacy: the big three.

In the context of rapid changes and constant developments in the financial sector and the broader economy, it is important to understand whether people are equipped to effectively navigate the maze of financial decisions that they face every day. To provide the tools for better financial decision-making, one must assess not only what people know but also what they need to know, and then evaluate the gap between those things. There are a few fundamental concepts at the basis of most financial decision-making. These concepts are universal, applying to every context and economic environment. Three such concepts are (1) numeracy as it relates to the capacity to do interest rate calculations and understand interest compounding; (2) understanding of inflation; and (3) understanding of risk diversification. Translating these concepts into easily measured financial literacy metrics is difficult, but Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2008 , 2011b , 2011c ) have designed a standard set of questions around these concepts and implemented them in numerous surveys in the USA and around the world.

Four principles informed the design of these questions, as described in detail by Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ). The first is simplicity : the questions should measure knowledge of the building blocks fundamental to decision-making in an intertemporal setting. The second is relevance : the questions should relate to concepts pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day financial decisions over the life cycle; moreover, they must capture general rather than context-specific ideas. Third is brevity : the number of questions must be few enough to secure widespread adoption; and fourth is capacity to differentiate , meaning that questions should differentiate financial knowledge in such a way as to permit comparisons across people. Each of these principles is important in the context of face-to-face, telephone, and online surveys.

Three basic questions (since dubbed the “Big Three”) to measure financial literacy have been fielded in many surveys in the USA, including the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) and, more recently, the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and in many national surveys around the world. They have also become the standard way to measure financial literacy in surveys used by the private sector. For example, the Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement included the Big Three questions in the 2018 Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, covering around 16,000 people in 15 countries. Both ING and Allianz, but also investment funds, and pension funds have used the Big Three to measure financial literacy. The exact wording of the questions is provided in Table 1 .

2.2 Cross-country comparison

The first examination of financial literacy using the Big Three was possible due to a special module on financial literacy and retirement planning that Lusardi and Mitchell designed for the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is a survey of Americans over age 50. Astonishingly, the data showed that only half of older Americans—who presumably had made many financial decisions in their lives—could answer the two basic questions measuring understanding of interest rates and inflation (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ). And just one third demonstrated understanding of these two concepts and answered the third question, measuring understanding of risk diversification, correctly. It is sobering that recent US surveys, such as the 2015 NFCS, the 2016 SCF, and the 2017 Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking (SHED), show that financial knowledge has remained stubbornly low over time.

Over time, the Big Three have been added to other national surveys across countries and Lusardi and Mitchell have coordinated a project called Financial Literacy around the World (FLat World), which is an international comparison of financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ).

Findings from the FLat World project, which so far includes data from 15 countries, including Switzerland, highlight the urgent need to improve financial literacy (see Table 2 ). Across countries, financial literacy is at a crisis level, with the average rate of financial literacy, as measured by those answering correctly all three questions, at around 30%. Moreover, only around 50% of respondents in most countries are able to correctly answer the two financial literacy questions on interest rates and inflation correctly. A noteworthy point is that most countries included in the FLat World project have well-developed financial markets, which further highlights the cause for alarm over the demonstrated lack of the financial literacy. The fact that levels of financial literacy are so similar across countries with varying levels of economic development—indicating that in terms of financial knowledge, the world is indeed flat —shows that income levels or ubiquity of complex financial products do not by themselves equate to a more financially literate population.

Other noteworthy findings emerge in Table 2 . For instance, as expected, understanding of the effects of inflation (i.e., of real versus nominal values) among survey respondents is low in countries that have experienced deflation rather than inflation: in Japan, understanding of inflation is at 59%; in other countries, such as Germany, it is at 78% and, in the Netherlands, it is at 77%. Across countries, individuals have the lowest level of knowledge around the concept of risk, and the percentage of correct answers is particularly low when looking at knowledge of risk diversification. Here, we note the prevalence of “do not know” answers. While “do not know” responses hover around 15% on the topic of interest rates and 18% for inflation, about 30% of respondents—in some countries even more—are likely to respond “do not know” to the risk diversification question. In Switzerland, 74% answered the risk diversification question correctly and 13% reported not knowing the answer (compared to 3% and 4% responding “do not know” for the interest rates and inflation questions, respectively).

These findings are supported by many other surveys. For example, the 2014 Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey shows that, around the world, people know the least about risk and risk diversification (Klapper, Lusardi, and Van Oudheusden, 2015 ). Similarly, results from the 2016 Allianz survey, which collected evidence from ten European countries on money, financial literacy, and risk in the digital age, show very low-risk literacy in all countries covered by the survey. In Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, which are the three top-performing nations in term of financial knowledge, less than 20% of respondents can answer three questions related to knowledge of risk and risk diversification (Allianz, 2017 ).

Other surveys show that the findings about financial literacy correlate in an expected way with other data. For example, performance on the mathematics and science sections of the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) correlates with performance on the Big Three and, specifically, on the question relating to interest rates. Similarly, respondents in Sweden, which has experienced pension privatization, performed better on the risk diversification question (at 68%), than did respondents in Russia and East Germany, where people have had less exposure to the stock market. For researchers studying financial knowledge and its effects, these findings hint to the fact that financial literacy could be the result of choice and not an exogenous variable.

To summarize, financial literacy is low across the world and higher national income levels do not equate to a more financially literate population. The design of the Big Three questions enables a global comparison and allows for a deeper understanding of financial literacy. This enhances the measure’s utility because it helps to identify general and specific vulnerabilities across countries and within population subgroups, as will be explained in the next section.

2.3 Who knows the least?

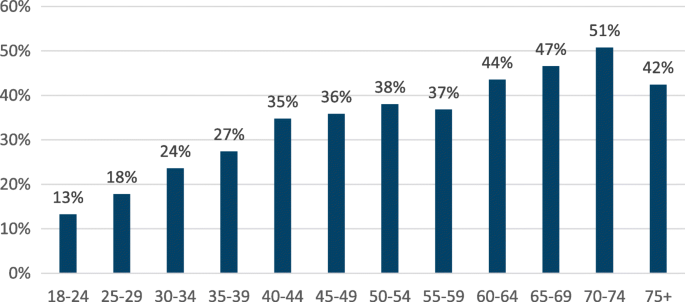

Low financial literacy on average is exacerbated by patterns of vulnerability among specific population subgroups. For instance, as reported in Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ), even though educational attainment is positively correlated with financial literacy, it is not sufficient. Even well-educated people are not necessarily savvy about money. Financial literacy is also low among the young. In the USA, less than 30% of respondents can correctly answer the Big Three by age 40, even though many consequential financial decisions are made well before that age (see Fig. 1 ). Similarly, in Switzerland, only 45% of those aged 35 or younger are able to correctly answer the Big Three questions. Footnote 1 And if people may learn from making financial decisions, that learning seems limited. As shown in Fig. 1 , many older individuals, who have already made decisions, cannot answer three basic financial literacy questions.

Financial literacy across age in the USA. This figure shows the percentage of respondents who answered correctly all Big Three questions by age group (year 2015). Source: 2015 US National Financial Capability Study

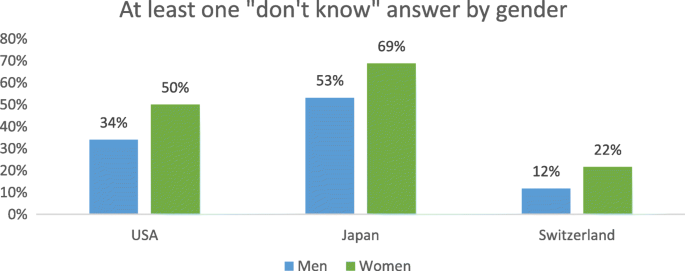

A gender gap in financial literacy is also present across countries. Women are less likely than men to answer questions correctly. The gap is present not only on the overall scale but also within each topic, across countries of different income levels, and at different ages. Women are also disproportionately more likely to indicate that they do not know the answer to specific questions (Fig. 2 ), highlighting overconfidence among men and awareness of lack of knowledge among women. Even in Finland, which is a relatively equal society in terms of gender, 44% of men compared to 27% of women answer all three questions correctly and 18% of women give at least one “do not know” response versus less than 10% of men (Kalmi and Ruuskanen, 2017 ). These figures further reflect the universality of the Big Three questions. As reported in Fig. 2 , “do not know” responses among women are prevalent not only in European countries, for example, Switzerland, but also in North America (represented in the figure by the USA, though similar findings are reported in Canada) and in Asia (represented in the figure by Japan). Those interested in learning more about the differences in financial literacy across demographics and other characteristics can consult Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2011c , 2014 ).

Gender differences in the responses to the Big Three questions. Sources: USA—Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ; Japan—Sekita, 2011 ; Switzerland—Brown and Graf, 2013

3 Does financial literacy matter?

A growing number of financial instruments have gained importance, including alternative financial services such as payday loans, pawnshops, and rent to own stores that charge very high interest rates. Simultaneously, in the changing economic landscape, people are increasingly responsible for personal financial planning and for investing and spending their resources throughout their lifetime. We have witnessed changes not only in the asset side of household balance sheets but also in the liability side. For example, in the USA, many people arrive close to retirement carrying a lot more debt than previous generations did (Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero, 2018 ). Overall, individuals are making substantially more financial decisions over their lifetime, living longer, and gaining access to a range of new financial products. These trends, combined with low financial literacy levels around the world and, particularly, among vulnerable population groups, indicate that elevating financial literacy must become a priority for policy makers.

There is ample evidence of the impact of financial literacy on people’s decisions and financial behavior. For example, financial literacy has been proven to affect both saving and investment behavior and debt management and borrowing practices. Empirically, financially savvy people are more likely to accumulate wealth (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014 ). There are several explanations for why higher financial literacy translates into greater wealth. Several studies have documented that those who have higher financial literacy are more likely to plan for retirement, probably because they are more likely to appreciate the power of interest compounding and are better able to do calculations. According to the findings of the FLat World project, answering one additional financial question correctly is associated with a 3–4 percentage point greater probability of planning for retirement; this finding is seen in Germany, the USA, Japan, and Sweden. Financial literacy is found to have the strongest impact in the Netherlands, where knowing the right answer to one additional financial literacy question is associated with a 10 percentage point higher probability of planning (Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015 ). Empirically, planning is a very strong predictor of wealth; those who plan arrive close to retirement with two to three times the amount of wealth as those who do not plan (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ).

Financial literacy is also associated with higher returns on investments and investment in more complex assets, such as stocks, which normally offer higher rates of return. This finding has important consequences for wealth; according to the simulation by Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell ( 2017 ), in the context of a life-cycle model of saving with many sources of uncertainty, from 30 to 40% of US retirement wealth inequality can be accounted for by differences in financial knowledge. These results show that financial literacy is not a sideshow, but it plays a critical role in saving and wealth accumulation.

Financial literacy is also strongly correlated with a greater ability to cope with emergency expenses and weather income shocks. Those who are financially literate are more likely to report that they can come up with $2000 in 30 days or that they are able to cover an emergency expense of $400 with cash or savings (Hasler, Lusardi, and Oggero, 2018 ).

With regard to debt behavior, those who are more financially literate are less likely to have credit card debt and more likely to pay the full balance of their credit card each month rather than just paying the minimum due (Lusardi and Tufano, 2009 , 2015 ). Individuals with higher financial literacy levels also are more likely to refinance their mortgages when it makes sense to do so, tend not to borrow against their 401(k) plans, and are less likely to use high-cost borrowing methods, e.g., payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, and refund anticipation loans (Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg, 2013 ).

Several studies have documented poor debt behavior and its link to financial literacy. Moore ( 2003 ) reported that the least financially literate are also more likely to have costly mortgages. Lusardi and Tufano ( 2015 ) showed that the least financially savvy incurred high transaction costs, paying higher fees and using high-cost borrowing methods. In their study, the less knowledgeable also reported excessive debt loads and an inability to judge their debt positions. Similarly, Mottola ( 2013 ) found that those with low financial literacy were more likely to engage in costly credit card behavior, and Utkus and Young ( 2011 ) concluded that the least literate were more likely to borrow against their 401(k) and pension accounts.

Young people also struggle with debt, in particular with student loans. According to Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Oggero ( 2016 ), Millennials know little about their student loans and many do not attempt to calculate the payment amounts that will later be associated with the loans they take. When asked what they would do, if given the chance to revisit their student loan borrowing decisions, about half of Millennials indicate that they would make a different decision.

Finally, a recent report on Millennials in the USA (18- to 34-year-olds) noted the impact of financial technology (fintech) on the financial behavior of young individuals. New and rapidly expanding mobile payment options have made transactions easier, quicker, and more convenient. The average user of mobile payments apps and technology in the USA is a high-income, well-educated male who works full time and is likely to belong to an ethnic minority group. Overall, users of mobile payments are busy individuals who are financially active (holding more assets and incurring more debt). However, mobile payment users display expensive financial behaviors, such as spending more than they earn, using alternative financial services, and occasionally overdrawing their checking accounts. Additionally, mobile payment users display lower levels of financial literacy (Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Avery, 2018 ). The rapid growth in fintech around the world juxtaposed with expensive financial behavior means that more attention must be paid to the impact of mobile payment use on financial behavior. Fintech is not a substitute for financial literacy.

4 The way forward for financial literacy and what works

Overall, financial literacy affects everything from day-to-day to long-term financial decisions, and this has implications for both individuals and society. Low levels of financial literacy across countries are correlated with ineffective spending and financial planning, and expensive borrowing and debt management. These low levels of financial literacy worldwide and their widespread implications necessitate urgent efforts. Results from various surveys and research show that the Big Three questions are useful not only in assessing aggregate financial literacy but also in identifying vulnerable population subgroups and areas of financial decision-making that need improvement. Thus, these findings are relevant for policy makers and practitioners. Financial illiteracy has implications not only for the decisions that people make for themselves but also for society. The rapid spread of mobile payment technology and alternative financial services combined with lack of financial literacy can exacerbate wealth inequality.

To be effective, financial literacy initiatives need to be large and scalable. Schools, workplaces, and community platforms provide unique opportunities to deliver financial education to large and often diverse segments of the population. Furthermore, stark vulnerabilities across countries make it clear that specific subgroups, such as women and young people, are ideal targets for financial literacy programs. Given women’s awareness of their lack of financial knowledge, as indicated via their “do not know” responses to the Big Three questions, they are likely to be more receptive to financial education.

The near-crisis levels of financial illiteracy, the adverse impact that it has on financial behavior, and the vulnerabilities of certain groups speak of the need for and importance of financial education. Financial education is a crucial foundation for raising financial literacy and informing the next generations of consumers, workers, and citizens. Many countries have seen efforts in recent years to implement and provide financial education in schools, colleges, and workplaces. However, the continuously low levels of financial literacy across the world indicate that a piece of the puzzle is missing. A key lesson is that when it comes to providing financial education, one size does not fit all. In addition to the potential for large-scale implementation, the main components of any financial literacy program should be tailored content, targeted at specific audiences. An effective financial education program efficiently identifies the needs of its audience, accurately targets vulnerable groups, has clear objectives, and relies on rigorous evaluation metrics.

Using measures like the Big Three questions, it is imperative to recognize vulnerable groups and their specific needs in program designs. Upon identification, the next step is to incorporate this knowledge into financial education programs and solutions.

School-based education can be transformational by preparing young people for important financial decisions. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in both 2012 and 2015, found that, on average, only 10% of 15-year-olds achieved maximum proficiency on a five-point financial literacy scale. As of 2015, about one in five of students did not have even basic financial skills (see OECD, 2017 ). Rigorous financial education programs, coupled with teacher training and high school financial education requirements, are found to be correlated with fewer defaults and higher credit scores among young adults in the USA (Urban, Schmeiser, Collins, and Brown, 2018 ). It is important to target students and young adults in schools and colleges to provide them with the necessary tools to make sound financial decisions as they graduate and take on responsibilities, such as buying cars and houses, or starting retirement accounts. Given the rising cost of education and student loan debt and the need of young people to start contributing as early as possible to retirement accounts, the importance of financial education in school cannot be overstated.

There are three compelling reasons for having financial education in school. First, it is important to expose young people to the basic concepts underlying financial decision-making before they make important and consequential financial decisions. As noted in Fig. 1 , financial literacy is very low among the young and it does not seem to increase a lot with age/generations. Second, school provides access to financial literacy to groups who may not be exposed to it (or may not be equally exposed to it), for example, women. Third, it is important to reduce the costs of acquiring financial literacy, if we want to promote higher financial literacy both among individuals and among society.

There are compelling reasons to have personal finance courses in college as well. In the same way in which colleges and university offer courses in corporate finance to teach how to manage the finances of firms, so today individuals need the knowledge to manage their own finances over the lifetime, which in present discounted value often amount to large values and are made larger by private pension accounts.

Financial education can also be efficiently provided in workplaces. An effective financial education program targeted to adults recognizes the socioeconomic context of employees and offers interventions tailored to their specific needs. A case study conducted in 2013 with employees of the US Federal Reserve System showed that completing a financial literacy learning module led to significant changes in retirement planning behavior and better-performing investment portfolios (Clark, Lusardi, and Mitchell, 2017 ). It is also important to note the delivery method of these programs, especially when targeted to adults. For instance, video formats have a significantly higher impact on financial behavior than simple narratives, and instruction is most effective when it is kept brief and relevant (Heinberg et al., 2014 ).

The Big Three also show that it is particularly important to make people familiar with the concepts of risk and risk diversification. Programs devoted to teaching risk via, for example, visual tools have shown great promise (Lusardi et al., 2017 ). The complexity of some of these concepts and the costs of providing education in the workplace, coupled with the fact that many older individuals may not work or work in firms that do not offer such education, provide other reasons why financial education in school is so important.

Finally, it is important to provide financial education in the community, in places where people go to learn. A recent example is the International Federation of Finance Museums, an innovative global collaboration that promotes financial knowledge through museum exhibits and the exchange of resources. Museums can be places where to provide financial literacy both among the young and the old.

There are a variety of other ways in which financial education can be offered and also targeted to specific groups. However, there are few evaluations of the effectiveness of such initiatives and this is an area where more research is urgently needed, given the statistics reported in the first part of this paper.

5 Concluding remarks

The lack of financial literacy, even in some of the world’s most well-developed financial markets, is of acute concern and needs immediate attention. The Big Three questions that were designed to measure financial literacy go a long way in identifying aggregate differences in financial knowledge and highlighting vulnerabilities within populations and across topics of interest, thereby facilitating the development of tailored programs. Many such programs to provide financial education in schools and colleges, workplaces, and the larger community have taken existing evidence into account to create rigorous solutions. It is important to continue making strides in promoting financial literacy, by achieving scale and efficiency in future programs as well.

In August 2017, I was appointed Director of the Italian Financial Education Committee, tasked with designing and implementing the national strategy for financial literacy. I will be able to apply my research to policy and program initiatives in Italy to promote financial literacy: it is an essential skill in the twenty-first century, one that individuals need if they are to thrive economically in today’s society. As the research discussed in this paper well documents, financial literacy is like a global passport that allows individuals to make the most of the plethora of financial products available in the market and to make sound financial decisions. Financial literacy should be seen as a fundamental right and universal need, rather than the privilege of the relatively few consumers who have special access to financial knowledge or financial advice. In today’s world, financial literacy should be considered as important as basic literacy, i.e., the ability to read and write. Without it, individuals and societies cannot reach their full potential.

See Brown and Graf ( 2013 ).

Abbreviations

Defined benefit (refers to pension plan)

Defined contribution (refers to pension plan)

Financial Literacy around the World

National Financial Capability Study

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Programme for International Student Assessment

Survey of Consumer Finances

Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking

Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement. (2018). The New Social Contract: a blueprint for retirement in the 21st century. The Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey 2018. Retrieved from https://www.aegon.com/en/Home/Research/aegon-retirement-readiness-survey-2018/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Agnew, J., Bateman, H., & Thorp, S. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Australia. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Allianz (2017). When will the penny drop? Money, financial literacy and risk in the digital age. Retrieved from http://gflec.org/initiatives/money-finlit-risk/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Almenberg, J., & Säve-Söderbergh, J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 585–598.

Article Google Scholar

Arrondel, L., Debbich, M., & Savignac, F. (2013). Financial literacy and financial planning in France. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Beckmann, E. (2013). Financial literacy and household savings in Romania. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Boisclair, D., Lusardi, A., & Michaud, P. C. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Canada. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 277–296.

Brown, M., & Graf, R. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Bucher-Koenen, T., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 565–584.

Clark, R., Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Employee financial literacy and retirement plan behavior: a case study. Economic Inquiry, 55 (1), 248–259.

Crossan, D., Feslier, D., & Hurnard, R. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in New Zealand. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 619–635.

Fornero, E., & Monticone, C. (2011). Financial literacy and pension plan participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 547–564.

Hasler, A., Lusardi, A., and Oggero, N. (2018). Financial fragility in the US: evidence and implications. GFLEC working paper n. 2018–1.

Heinberg, A., Hung, A., Kapteyn, A., Lusardi, A., Samek, A. S., & Yoong, J. (2014). Five steps to planning success: experimental evidence from US households. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30 (4), 697–724.

Kalmi, P., & Ruuskanen, O. P. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 17 (3), 1–28.

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). Financial literacy around the world. In Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (GFLEC working paper).

Google Scholar