- Argumentative

- Ecocriticism

- Informative

- Explicatory

- Illustrative

- Problem Solution

- Interpretive

- Music Analysis

- All Essay Examples

- Entertainment

- Law, Crime & Punishment

- Artificial Intelligence

- Environment

- Geography & Travel

- Government & Politics

- Nursing & Health

- Information Science and Technology

- All Essay Topics

Reflection On Health And Safety

Health and safety are paramount in every aspect of life, whether in the workplace, at home, or in the community. Reflecting on the importance of health and safety measures is crucial to ensure the well-being of individuals and the overall functioning of society. This essay delves into the significance of prioritizing health and safety, the challenges faced in maintaining them, and the strategies to promote a culture of safety.

First and foremost, prioritizing health and safety is essential because it directly impacts the quality of life and productivity of individuals. In the workplace, adherence to safety protocols reduces the risk of accidents and injuries, thereby safeguarding employees' physical and mental well-being. Moreover, a safe working environment fosters a sense of security and trust among workers, leading to increased job satisfaction and morale. Similarly, in daily life, practicing safety measures such as wearing seat belts, following traffic rules, and maintaining hygiene habits significantly reduce the occurrence of accidents and illnesses, contributing to overall health and longevity.

However, despite the awareness of the importance of health and safety, numerous challenges hinder their effective implementation. One such challenge is complacency, where individuals become lax in adhering to safety protocols due to familiarity or a perceived sense of invincibility. Additionally, financial constraints may limit organizations' ability to invest in robust safety infrastructure or training programs, leaving employees vulnerable to hazards. Moreover, cultural attitudes and societal norms may influence people to prioritize convenience over safety, further exacerbating risks.

To promote a culture of safety, proactive measures and strategies are imperative. Organizations can prioritize safety by integrating it into their core values and establishing clear policies and procedures. This includes regular safety training for employees, conducting risk assessments, and implementing measures to mitigate identified hazards. Furthermore, fostering open communication channels where employees can voice safety concerns without fear of reprisal encourages a collective responsibility towards safety.

In conclusion, reflecting on health and safety underscores their fundamental importance in preserving life and well-being. By acknowledging the challenges and implementing proactive measures, individuals and organizations can create environments that prioritize safety, ultimately contributing to a healthier and safer society for all.

Related Essays

- Level 2 Reflective Account - Health and Safety Essay

- Outline How Legislation, Policies and Procedures Relating to Health, Safety and Security Influence Health and Social Care Settings.

- Contribute to Health and Safety in Health and Social Care ( Hsc 027)

- Btec Level 3 Health and Social Care - Health and Safety Unit 3

- Cultural Safety In Health Care

US Occupational Safety And Health Act (OSHA) Of 1970

The United States Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) is a landmark piece of legislation aimed at ensuring safe and healthy working conditions for employees across various industries. Enacted in 1970, OSHA was a response to the alarming rates of workplace injuries, illnesses, and fatalities that were prevalent at the time. The primary objective of OSHA is to prevent workplace hazards by setting and enforcing standards, providing training, outreach, education, and assistance to both employers and employees. One of the key provisions of OSHA is the requirement for employers to provide a workplace free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees. This includes ensuring that machinery and equipment are properly maintained, providing personal protective equipment (PPE) where necessary, and implementing safety protocols and procedures. By holding employers accountable for maintaining safe working environments, OSHA has played a crucial role in reducing workplace accidents and fatalities over the years. In addition to setting and enforcing safety standards, OSHA also provides training and educational resources to both employers and employees. This includes programs such as the OSHA Training Institute (OTI) Education Centers, which offer courses on various occupational safety and health topics. By empowering employers and employees with the knowledge and skills to identify and mitigate workplace hazards, OSHA helps to prevent accidents and injuries before they occur. Furthermore, OSHA promotes workplace safety through outreach and assistance programs designed to raise awareness and provide support to employers and employees. These programs include partnerships with industry associations, trade unions, and other organizations to develop best practices and promote a culture of safety in the workplace. By collaborating with stakeholders and fostering a collective commitment to safety, OSHA has been able to make significant strides in reducing workplace injuries and fatalities. In conclusion, the United States Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) plays a vital role in protecting the health and safety of workers across the country. Through its comprehensive approach to preventing workplace hazards, enforcing safety standards, and providing training and support, OSHA has contributed to significant improvements in workplace safety over the past decades. However, ongoing efforts are needed to ensure that OSHA continues to adapt to emerging risks and challenges in the modern workplace....

- Workplace Culture

- Public Services

Contribute to Children and Young Peoples Health and Safety (Cu1512)

Ensuring the health and well-being of children and young people is a collective responsibility that requires concerted efforts from various stakeholders, including parents, educators, healthcare professionals, policymakers, and the wider community. By contributing to children and young people's health, individuals and institutions play a pivotal role in shaping their physical, mental, and emotional development, thereby laying the foundation for a healthier and more prosperous future. One of the primary ways to contribute to children and young people's health is by promoting healthy lifestyle habits from an early age. This encompasses fostering nutritious eating habits, encouraging regular physical activity, and promoting adequate sleep patterns. By instilling these habits during childhood and adolescence, individuals can mitigate the risk of obesity, chronic diseases, and mental health disorders later in life, thus fostering a healthier population overall. Moreover, access to quality healthcare services is essential for safeguarding children and young people's health. This entails ensuring timely vaccinations, regular health check-ups, and prompt medical interventions when needed. By advocating for accessible and equitable healthcare services, individuals and organizations can address disparities in health outcomes among children and young people, particularly those from marginalized or underserved communities. Furthermore, creating supportive environments that prioritize children and young people's well-being is crucial for fostering their overall health. This includes promoting safe and nurturing home environments, fostering positive relationships with peers and adults, and providing opportunities for educational and social development. Additionally, addressing environmental factors such as air quality, access to green spaces, and exposure to harmful substances can further contribute to children and young people's health outcomes. In conclusion, contributing to children and young people's health requires a holistic approach that encompasses various dimensions, including lifestyle factors, healthcare access, and environmental considerations. By promoting healthy habits, advocating for equitable healthcare services, and creating supportive environments, individuals and institutions can collectively empower the next generation to lead healthier and more fulfilling lives. Ultimately, investing in children and young people's health is not only a moral imperative but also a strategic investment in the well-being and prosperity of society as a whole....

- Nutrition & Dieting

- Public Health Issues

- Global Health Challenges

Pwcs 37 Understand Health and Safety in Social Care Settings Essay

Health and safety in the workplace is a crucial aspect of any organization, as it not only ensures the well-being of employees but also contributes to the overall productivity and success of the business. By understanding the principles of health and safety, employers can create a safe and healthy work environment for their employees, reducing the risk of accidents and injuries. One of the key aspects of health and safety in the workplace is risk assessment. Employers must identify and assess any potential risks that could harm their employees and take appropriate measures to eliminate or minimize these risks. This could include providing training on how to safely use equipment, implementing safety procedures, and ensuring that the workplace is free from hazards. By conducting regular risk assessments, employers can proactively address any safety concerns and prevent accidents from occurring. Another important aspect of health and safety in the workplace is the provision of adequate training and information. Employees should be trained on how to safely perform their job duties, as well as how to respond in case of an emergency. This could include training on how to use fire extinguishers, first aid procedures, and how to report any safety concerns to management. By providing employees with the necessary training and information, employers can empower them to take an active role in maintaining a safe work environment. In addition to risk assessment and training, employers must also ensure that they comply with relevant health and safety regulations. This could include implementing safety policies and procedures, conducting regular inspections, and providing personal protective equipment where necessary. By staying up to date with health and safety regulations, employers can demonstrate their commitment to the well-being of their employees and avoid potential legal issues. In conclusion, understanding health and safety in the workplace is essential for creating a safe and healthy work environment. By conducting risk assessments, providing adequate training and information, and complying with regulations, employers can protect their employees from harm and create a positive workplace culture. Ultimately, prioritizing health and safety in the workplace not only benefits employees but also contributes to the overall success of the organization....

- Health Care

Mental Health Clinical Reflection

During my recent clinical experience in a mental health setting, I had the opportunity to witness firsthand the complexities and challenges faced by individuals struggling with various mental health conditions. One particular encounter that left a lasting impact on me was with a patient diagnosed with severe anxiety disorder. The patient, a young woman in her mid-20s, exhibited classic symptoms of anxiety, including restlessness, rapid heartbeat, and difficulty concentrating. As I observed her interactions with the healthcare team, it became clear to me the importance of empathy and understanding in providing effective care for individuals with mental health issues. In my role as a student observer, I was able to witness the collaborative efforts of the healthcare professionals in managing the patient's anxiety symptoms. The interdisciplinary team, consisting of psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and social workers, worked together to develop a comprehensive treatment plan tailored to the patient's specific needs. I learned the significance of a holistic approach to mental health care, where medication management, therapy sessions, and social support all play crucial roles in promoting recovery and well-being. Moreover, the clinical experience shed light on the stigma surrounding mental health disorders and the impact it has on patients' lives. Despite the advancements in mental health awareness, there is still a significant level of misunderstanding and discrimination towards individuals with psychiatric conditions. This experience reinforced the importance of destigmatizing mental health issues and promoting open discussions to create a more supportive and inclusive environment for those in need of help. In conclusion, my mental health clinical reflection has been a profound learning experience that has deepened my understanding of the complexities of mental health care. It has highlighted the importance of empathy, interdisciplinary collaboration, and destigmatization in providing effective support and treatment for individuals facing mental health challenges. Moving forward, I am committed to advocating for mental health awareness and working towards creating a more compassionate and understanding society for all individuals, especially those struggling with mental health issues....

- History of the United States

- Branches of Psychology

1.2 Explain The Main Point Of Health And Safety Policies And Procedures

Health and safety at work regulations are put in place to ensure the well-being of employees in the workplace. These regulations are designed to prevent accidents, injuries, and illnesses that may occur while on the job. Employers have a legal responsibility to provide a safe working environment for their employees and must comply with these regulations to avoid potential fines and legal consequences. One of the key aspects of health and safety at work regulations is the requirement for employers to conduct risk assessments. Risk assessments involve identifying potential hazards in the workplace and taking steps to eliminate or minimize them. This may include providing appropriate safety equipment, implementing safety procedures, and providing training to employees on how to safely perform their job duties. By conducting regular risk assessments, employers can proactively address potential safety issues before they result in accidents or injuries. Another important aspect of health and safety at work regulations is the requirement for employers to provide adequate training to employees. Training should cover topics such as how to use safety equipment, how to identify hazards, and what to do in case of an emergency. By ensuring that employees are properly trained, employers can help prevent accidents and injuries in the workplace. Additionally, training can empower employees to take an active role in maintaining a safe work environment and reporting any safety concerns to their employer. In conclusion, health and safety at work regulations play a crucial role in protecting the well-being of employees in the workplace. Employers must comply with these regulations to ensure that their employees are safe while on the job. By conducting risk assessments, providing adequate training, and implementing safety procedures, employers can create a safe work environment that reduces the risk of accidents and injuries. Ultimately, prioritizing health and safety at work benefits both employees and employers by promoting a culture of safety and well-being in the workplace....

Health And Safety At Work Act 1999

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1999 is a pivotal piece of legislation aimed at ensuring the health, safety, and welfare of individuals in the workplace across the United Kingdom. Enacted as a crucial response to the growing concerns regarding workplace hazards and employee well-being, this act lays down fundamental principles and obligations that employers must adhere to in order to create a safe and secure working environment. One of the key provisions of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1999 is the duty of employers to conduct risk assessments. Employers are required to assess the potential risks associated with their workplace activities and implement measures to mitigate these risks. This proactive approach not only safeguards the health and safety of employees but also helps in preventing accidents and injuries, thereby fostering a culture of prevention and care within the workplace. Furthermore, the act emphasizes the importance of providing adequate training and information to employees regarding health and safety procedures. Employers have a legal obligation to ensure that their staff members are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out their tasks safely. By investing in training programs and disseminating relevant information, employers empower their workforce to identify potential hazards and take appropriate precautions, thereby reducing the likelihood of accidents and injuries. In addition to protecting employees, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1999 also places obligations on employers to safeguard the health and safety of visitors and members of the public who may be affected by their activities. This includes implementing measures to control access to hazardous areas, providing clear signage and warnings, and taking precautions to prevent accidents or incidents that could harm external parties. In conclusion, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1999 plays a pivotal role in promoting a culture of health, safety, and well-being in the workplace. By outlining clear responsibilities for employers and emphasizing the importance of risk assessment, training, and information dissemination, this legislation ensures that individuals can work in environments that are free from harm and conducive to their overall health and welfare. Compliance with the provisions of this act not only fulfills legal obligations but also fosters a positive and supportive working environment where employees can thrive....

- Environmental Sustainability

- Cybersecurity and National Security

Reflective Account On Health And Social Care

Health and social care play pivotal roles in ensuring the well-being and quality of life for individuals within a community. Reflecting on my experiences within this field, I have come to appreciate the multifaceted nature of these services and the profound impact they have on individuals, families, and society as a whole. One aspect that stands out in my reflection is the importance of effective communication in health and social care settings. Clear and empathetic communication is essential for building trust and understanding between healthcare professionals, service users, and their families. Through my interactions with patients and their loved ones, I have learned the significance of active listening, non-verbal cues, and adapting communication styles to meet the diverse needs of individuals. Furthermore, my experiences have highlighted the critical role of collaboration and teamwork in delivering comprehensive care. In health and social care settings, interdisciplinary teams often work together to address the complex needs of patients, incorporating medical, psychological, and social interventions. Through collaborative efforts, professionals can leverage their unique expertise to provide holistic support and promote positive outcomes for service users. Another aspect of my reflection centers on the ethical considerations inherent in health and social care practice. As professionals, we are entrusted with the well-being and dignity of those under our care, and it is imperative to uphold ethical principles such as autonomy, beneficence, and justice. Reflecting on challenging situations, I have grappled with dilemmas related to informed consent, confidentiality, and resource allocation, underscoring the need for ethical decision-making frameworks and ongoing ethical reflection. Moreover, my experiences have deepened my understanding of the broader social determinants of health and their impact on individual health outcomes. Factors such as socioeconomic status, access to education, and cultural background significantly influence an individual's health and well-being. Recognizing these determinants underscores the importance of adopting a holistic and person-centered approach to care, addressing not only immediate health concerns but also underlying social and environmental factors. In conclusion, reflecting on my experiences in health and social care has reinforced my appreciation for the complexity and significance of this field. Effective communication, collaboration, ethical practice, and consideration of social determinants are essential components of providing high-quality care and promoting positive outcomes for individuals and communities. By continually reflecting on our practice and learning from experiences, we can strive to enhance the delivery of health and social care services, ultimately contributing to the well-being of society as a whole....

Reflection Paper On Health

Health is a multifaceted concept that encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being. It is not merely the absence of disease but rather a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellness. Throughout my life, my understanding of health has evolved, shaped by personal experiences, education, and societal influences. From a young age, I viewed health primarily in terms of physical fitness and absence of illness. I believed that as long as I didn't get sick, I was healthy. However, as I matured and gained more knowledge about health, I realized that it extends beyond the absence of disease. It involves nourishing the body with nutritious food, engaging in regular physical activity, and prioritizing mental well-being. I began to understand the importance of holistic health and how each aspect intertwines to contribute to overall wellness. As I navigated through various stages of life, I encountered challenges that tested my understanding of health. During times of stress and adversity, I learned the significance of mental resilience and coping mechanisms. I discovered the power of mindfulness practices, such as meditation and deep breathing, in managing stress and promoting mental clarity. These experiences reinforced the idea that health is not solely determined by physical factors but also by emotional and psychological resilience. Moreover, my interactions with diverse communities and exposure to different cultural perspectives broadened my understanding of health. I came to appreciate the role of social determinants, such as access to healthcare, socioeconomic status, and environmental factors, in shaping health outcomes. I recognized the importance of addressing systemic inequalities and advocating for policies that promote health equity for all individuals, regardless of their background or circumstances. In conclusion, reflecting on my journey with health, I have come to realize that it is a dynamic and interconnected aspect of life. It encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being, and is influenced by personal experiences, education, and societal factors. Embracing a holistic approach to health has empowered me to make informed choices, prioritize self-care, and advocate for health equity within my community. As I continue to evolve and learn, I am committed to nurturing my health and inspiring others to embark on their own journey towards holistic wellness....

Can't find the essay examples you need?

Use the search box below to find your desired essay examples.

Reflective Practice in Health Care Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

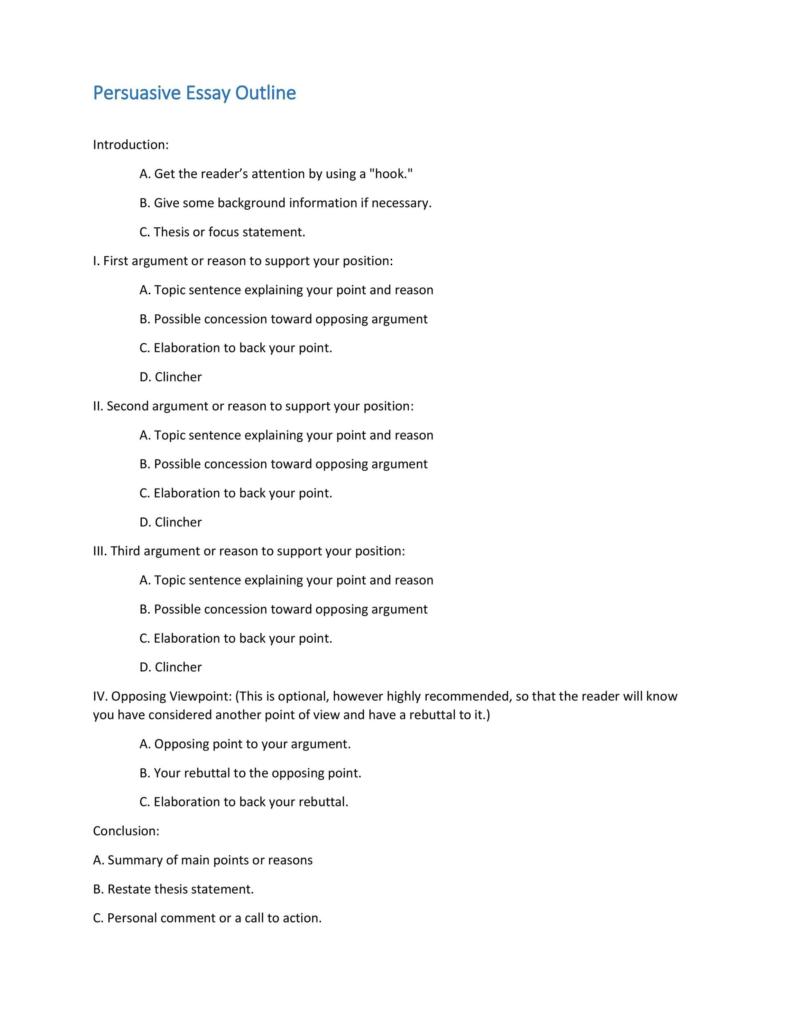

Introduction

The description/ event, evaluation and analysis, recommendation and action plan.

Reflection refers to an approach used to comprehend the personal practice process nature, which results in escalated knowledge as well as proper application in healthcare work, which eradicates the chances for medical errors (Walker, 1996). Reflection allows a person to think about an action and through this way, engage in a continuous learning process (Hendricks, Mooney and Berry, 1996: 100). Therefore, reflective practice is the most key source of personal improvement and professional development. As a result, the concept has become popular globally (Price, 2004: 470).

An evidence-based tool of practice applies the best care a patient can afford. The principal goal of evidence-based practice is clinical expert opinion or expertise, caregiver/ patient/ client perspectives (Pattinson, 2011). For the purpose of this assignment, the Gibbs reflective model is vital. A summarized model will offer reflection guidance as structured in the six stages. The stages are; event or description, feeling or thoughts, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and the action plan. This paper presents a case scenario where the practitioners involved in the care of the patient did not have effective communication, which impacted negatively on the patient. It also emphasizes the need for proper communication in health care.

Several years ago, as a senior anesthesia technician was just about to release an ODA for the lunch break, a boy who was approximately 5 years old and a pediatric cardiac patient was undergoing a dental clearance. After the dentist was thorough, the inhalation agent got terminated so as to allow the patient to recover prior to the removal of the endotracheal tube. The long extension set for intravenous use had already been closed as the short procedure was taking place. The boy began breathing again and tried to open his eyes. The reverse drugs were about to be given when the anesthetist requested the ODA to flush the intravenous line using 5ml of normal saline. However, the patient stopped breathing suddenly because of the boule that forced the residual muscle relaxant back into the patient. Consequently, the anesthetist began ventilating the patient, and it took approximately thirty minutes for the patient to recover. The patient did not experience considerable harm.

The shock was one of the feelings that overcame me first. The anesthetist was impatient in treating the patient and seemed to be in a hurry (Boud et al, 1985). He ought to have waited before flushing the intravenous line so as to avoid the formation of a boule, which forced the residual muscle relaxant back into the patient. Maybe he wanted to have finished all his duties before releasing the ODA for lunch. Moreover, there seemed to be miscommunication between the ODA and the anesthetist. Both of them should have deep knowledge of the process and, therefore, there should be no errors as was the case (Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper, 2001). It was extremely sad to see the suffering young boy lying down. I was torn between many negative emotions; sorrow, pity, empathy, and blame on the healthcare professionals (Davies, 2012).

As mandated by healthcare policies and standards, I strongly feel that healthcare professionals should adhere to them to prevent adverse effects on patients (Pattinson, 2011). Professionals ought to realize that there are countless areas where there can be a resultant detrimental impact on the well-being of the patient if there is miscommunication or inadequate communication between providers (Walker, 1996).

In the mentioned occasion, the patient should have taken the residual muscle relaxant out first before flushing the intravenous vein with normal saline (Molyneux, 2001). The anesthetist seemed not to be patient enough. Moreover, the anesthetist went beyond his obligation’s limit by authorizing the ODP to flush without thinking of the repercussions (Schon, 1991). In essence, the anesthetist failed to adhere to the protocol expected during patient management (Mac Suibhne, 2009: 434). Regardless of how long healthcare professionals have been in practice, they should always realize that they are dealing with human life and, therefore, be extremely keen (Mann and Gordon, 2009: 617).

In my reflection, I realized that there are numerous issues that are preventable if there is proper and effective communication within the settings (Schon, 1991). These include drug reactions and interactions, increased care cost and hospitalization time, untimely medications and procedures, and inappropriate treatment. All these can be prevented if professionals adhere to the protocols of effective communication (Asper, 2003: 45). If the anesthetist and ODP were communicating effectively and were aware of the proper guidelines to follow, the patient would have recovered normally from the procedure done.

It is imperative for the anesthetist to be aware of his vital role in the patient’s life. Hence, he should have adhered to the set protocol, guidelines, and standards, and ensured effective and timely communication between himself and the ODP. Flushing the IV after muscle relaxation ensures the patient recovers normally (Mann and Gordon, 2009: 617). Healthcare research indicates that approximately eighty percent of all grave medical errors are a result of miscommunication (Price, 2004: 47). It has been noted that when handing over patients to other professionals for specialized procedures, there is always incomplete information handover (Schön, 1991). Moreover, healthcare professionals lack adequate time to discuss the patients’ issues in detail, which results in negative impacts on the patient (Brown et al, 2003: 40).

In my opinion, the anesthetist was not sufficiently accountable and responsible. A medical practitioner who is responsible and accountable enough has a keen interest in a patient’s outcome. In this case, the anesthetist was impatient, which almost led to detrimental effects on the patient. He ought to have been accountable and waited for the muscles to relax before administering the drug. On the same note, the anesthetist and ODP ought to have ensured that proper medication is given to the patient. Price (2004: 40) asserts that this is because giving a patient the wrong medication is unethical and can result in detrimental patient effects.

It is worth noting that ineffective communication goes with other human factors. For instance, there might be differences among the various departments (Molyneux, 2001: 30). When professionals from these departments meet for a procedure, grudges they hold against each other may result in the patient suffering. This is ethically unacceptable and contrary to the patient’s rights (Bolton, 2010). Moreover, it is imperative that professionals go through the guidelines of the procedures they are to perform. This reduces the chances of errors. According to Schön (1991), another ethical measure is to seek the client’s consent.

It is worth noting that many patients suffer as a result of the failure of healthcare professionals to adhere to effective communication. Mostly, healthcare professionals do not dedicate adequate and quality time to patients (Larrivee, 2000: 293). They perform most of the procedures in a hurry, which affects patients negatively (Mann & Gordon, 2009: 620). If the anesthetist was not in a hurry and dedicated to the patient’s result, he would have allowed adequate time before flushing the IV. This would have ensured that the patient responded successfully after the procedure.

Ineffective and inadequate communication has been reported to be the vital contributing factor to inadvertent patient harm and medical errors (Welsh Assembly Government, 2008). It does not only result in emotional and physical inconveniences to all those concerned but also adverse happenings, which are extremely costly. For instance, the resulting cost from medical errors in Victoria’s hospitals is approximately a billion dollars every year (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985: 34). It is worth noting that today, healthcare is extremely diverse and complex, and improving communication amidst professionals in healthcare would considerably support safe patient care delivery (Asper, 2003). It is extremely vital that managements in hospitals stimulate action and discussion, as well as raise awareness in regard to the units, divisions, and organizations where more teamwork and improved communication is essential (Brown et al, 2003). Mostly, ineffective communication is particularly the known cause that leads to sentinel events. Ineffective communication which is ambiguous, incomplete, inaccurate, untimely, and where the recipient does not comprehend clearly, increases the results and errors, for poor patient safety (Welsh Assembly Government, 2008).

There exists immense evidence linking poor and ineffective communication between teams in healthcare (Mac Suibhne, 2009: 430). The stated results are extremely negative patient impacts (Brown et al, 2003: 96). For instance, according to America’s Joint Commission, the key cause of more than seventy percent of sentinel occurrences is a communication failure. Moreover, America’s Veterans Affairs Department National Centre for Patient Safety acknowledges that failed communication in healthcare is the chief root foundation of seventy-five percent negative patient impacts (Leitch and Day, 2000: 157).

When the patient sees too many patients, miscommunication may result (Brown et al, 2003: 103). Usually, patients make efforts to ensure the best treatment choices (Larrivee, 2000: 293). However, the treating doctor may be unconcerned about other experts caring for the patient. In most cases, physicians are usually unaware that their patients are being treated for disease complications (Hendricks, Mooney & Berry, 1996: 100). The spectrum of poor communication included services and medication being duplicated, the patient being given more medication than is necessary, and wrong surgery sites (Asper, 2003).

The negative drug interaction is another potential danger. This is mostly because the patient is ignorant of the medication being given and may not identify cases of over medication. Such a situation threatens life and should be prevented at all costs (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985: 91). Patients also have a role to play in their health care. They have the right to ask questions and confirm procedures (Davies, 2012: 7).

In order to ensure such a case never repeats among ODPs and anesthetists, the case will be reported to the head of the department. Discussing it will ensure that all professionals handle their patients with extra keenness and that they follow procedures and guidelines well (Ministry of Justice, 2006). Consequently, it will be discussed during the monthly meeting of the department. During the meeting, all health care professionals will be present, including the ODP and anesthetist in mention. Both will be requested to elaborate on what and why it happened. This will be aimed at reviewing their role in every procedure (Leitch and Day, 2000: 154). Moreover, the anesthetist will have to apologize to the family and elaborate on the issue to them. This will ensure accountability. These grave measures will be geared towards ensuring that all patients receive adequate, timely, and proper treatment (McSherry, Pearce and Tingle, 2011).

According to Davies (2012, 10), the main reason for writing and addressing the incident in detail is to prevent and avoid such an occurrence again. It is vital that the ODA enquires and double checks every detail with the anesthetist. Moreover, all drugs and syringes should be labeled to avoid using the wrong ones on the patient. The anesthetist should be the only one who handles them to avoid confusion.

An incident like this happens often in the UK. According to the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), such a case happens 109 times annually (Brown et al, 2003: 96). There is, therefore, a need to address issues surrounding it so as to reduce its incidence and prevalence.

In my opinion, failure to dedicate adequate time for patient care and miscommunication are the key causes of this incident. Following the HPC guidelines would have prevented the incident from occurring (Ministry of Justice, 2006). In the mentioned case, an efficient leader who could adhere to the use of a checklist and the structured plan was absent. This would guarantee patient safety before conducting the anesthesia as recommended by WHO.

In the light of this discussion, health care professionals should be trained adequately to ensure their effective communication and accountable participation (McSherry, Pearce and Tingle, 2011). I recommend that a structured documentation checklist, good teamwork, effective communication be made the key targets for a quality improvement plan which ensures patient safety in all departments (Asper, 2003). The majority of hospitals’ managements are unaware of the miscommunication pervasiveness that exists (Davies, 2012: 11). Moreover, miscommunication goes unnoticed in many healthcare settings. Factors that affect the quality of communication are usually ignored, which results in detrimental health impacts on patients (Schön, 1983).

In order to ensure effective communication between healthcare teams, there is the need to consider intercultural communication between staff, the circumstances and content of communication, various discourse modes, presence of resources and opportunities for creating a common body of understanding, and linguistic and cultural distances (Welsh Assembly Government, 2008). The management should ensure strategies where all these are incorporated towards effective communication (Asper, 2003: 34).

Asper, M 2003, Beginning Reflective Practice (Foundations in Nursing and Health Care) , Nelson Thomas Ltd., Cheltenham.

Bolton, G 2010, Reflective Practice, Writing and Professional Development (3rd edn), Sage Publications, California.

Boud, D, Keogh, R & Walker, D 1985, Reflection, Turning Experience into Learning , Routledge, New York.

Brown, G et al, eds., 2003, Becoming an Advanced Health Practitioner, Butterworth Heinemann, Edinburgh.

Davies, S 2012, “Embracing reflective practice”, Education for Primary Care, vol. 23, pp. 9–12.

Hendricks, J, Mooney, D & Berry, C 1996, “A practical strategy approach to the use of the reflective practice in critical care nursing”, Intensive & critical care nursing, vol. 12 no. 2, pp. 97–101.

Larrivee, B 2000, “Transforming Teaching Practice: Becoming the critically reflective teacher”, Reflective Practice, vol. 1 no. 3, pp. 293.

Leitch, R & Day, C 2000, “Action research and reflective practice: towards a holistic view”, Educational Action Research , vol. 8, pp. 179.

Mac Suibhne, S 2009, “’Wrestle to be the man philosophy wished to make you’: Marcus Aurelius, reflective practitioner”, Reflective Practice, vol. 10 no. 4, pp. 429–436.

Mann, K & Gordon, M 2009, “Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review”, Adv in Health Sci Educ, vol. 14, pp. 595–621.

McSherry, R, Pearce, P & Tingle, J 2011, Clinical governance: a guide to implementation for healthcare professionals (3rd ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

Ministry of Justice 2006, Making sense of human rights: a short introduction. Web.

Molyneux, J 2001, “Interprofessional teamworking: what makes teams work well”, Journal of Interprofessional Care , vol. 15 no.1, pp. 29-35.

Pattinson, S 2011, Medical law and ethics ( 3rd ed ) , Sweet & Maxwell/Thomson Reuters, London.

Price, 2004, “Encouraging reflection and critical thinking in practice”, Nursing Standard, vol. 18, pp. 47.

Rolfe, G, Freshwater, D & Jasper, M 2001, Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions , Palgrave, Basingstoke, U.K.

Schön, D. A 1983, The Reflective Practitioner, How Professionals Think In Action , Basic Books, London. Schon, D. A 1991, The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action , Arena, London.

Walker, S 1996, “Reflective practice in the accident and emergency setting”, Accident and emergency nursing, vol. 4 no.1, pp. 27–30.

Welsh Assembly Government 2008, Reference guide for consent to examination or treatment. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government. Web.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations

- Operations Management in Healthcare

- History of Early Anesthesia: From the Early 1840s to Nowadays

- Nurse Anaesthetist’s History and Role: Local Anesthesia and Complex Procedures

- Advanced Practice Nurse: Roles, Pros and Cons

- Health Workforce in Australia

- Higher Quality of Healthcare

- Centralization of Laboratory Information

- Major Health Policy Themes in Canada

- Conducting CODCD Building in Sydney University Project

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, May 9). Reflective Practice in Health Care. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reflective-practice-in-health-care/

"Reflective Practice in Health Care." IvyPanda , 9 May 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/reflective-practice-in-health-care/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Reflective Practice in Health Care'. 9 May.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Reflective Practice in Health Care." May 9, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reflective-practice-in-health-care/.

1. IvyPanda . "Reflective Practice in Health Care." May 9, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reflective-practice-in-health-care/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Reflective Practice in Health Care." May 9, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reflective-practice-in-health-care/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

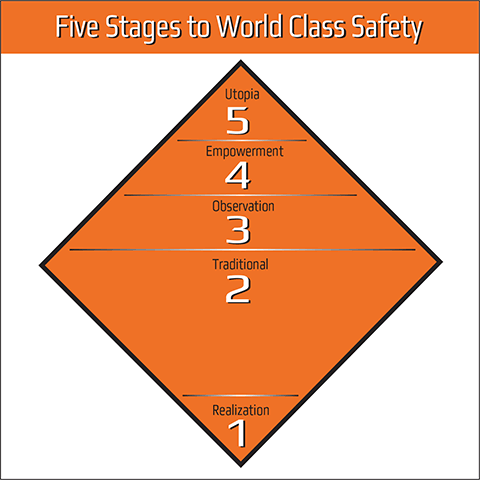

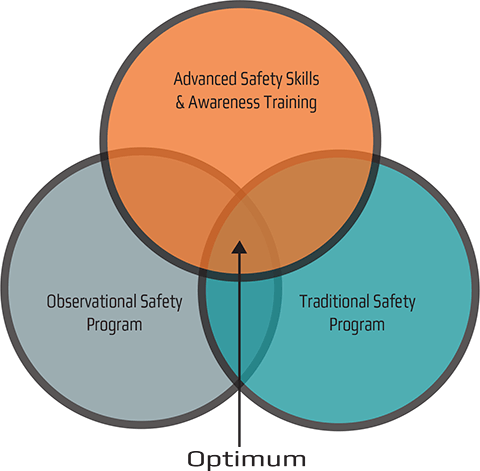

Reflections on safety

Recently, Safety Solutions magazine asked readers the question: "What do you think is the most important issue in workplace safety today?"- We received a huge number of responses - following are some of the editor's picks for the most useful answer to the question.

1 / Peter Goss

Safety in the workplace is all about identifying risks, and then managing those risks to avoid accidents and incidents. Workplaces that have high safety records do not necessarily have low risks in operations, and vice versa. High risk industries tend to appreciate the risks as the penalty for failure is often serious, or fatal.

The common thread that holds workplaces that have excellent safety performance records together is a management commitment to the safety system. Without management commitment, any safety system will be doomed to failure.

The trend in workplaces is that the workers in the workplace are becoming more casual and the use of labour hire firms is increasing. The crew of workers on site this month may not be the same as next month.

An induction program introduces workers to hazards and risks specific to the workplace and how the workplace manages those risks (eg, site rules and procedures). It sets the standard to which people are expected to work. With the ongoing casualisation of the work-force, management must understand that workers may work at several workplaces and that, if not inducted properly and managed and supervised properly, they may make incorrect assumptions and open themselves up to increased risk.

While it is easy to overlook subcontractor safety, casuals and subcontractors are stake-holders in the safety management system which must be managed and controlled properly. The most important issue in workplace safety is ensuring that as workplaces become more casualised, all stakeholders properly understand the risks of the industry and the site and that their understanding is continually verified.

2 / Bruce Fraser

I believe the most important issue in workplace safety today is simply the role each individual plays in whatever work/ob that is being carried out at the time.

Let me explain myself more clearly:

While we can institute legal and financial responsibilities on each individual for their actions during their work function, this still does not guarantee a safe work environment.

All workplaces are faced with similar safety considerations, the main difference being the methods used to complete the task at hand.

The only way to guarantee the highest level of safe operation at work is through the roles of each individual, backed up with a large helping of trust in a person's skills and abilities. Ultimately this means everyone being responsible for their own actions with the emphasis being on the completion of the task at hand safely and effectively.

Easy to say, you may think, however, also easy to do, with a bit of planning, education, and a solid set of standards and values, which are instituted and repeated regularly for all situations. It would be unfair to ask anyone to carry out a task effectively and safely if that person did not have all the tools to complete said task, and by tools I don't just mean spanners etc.

So, is it not fair then to expect a safe work ethic if proper preparation is undertaken?

There are so many clichés, adages, and proverbs about this situation that some of these thoughts must be true, however mundane and simple they sound. After all, they were written based on other peoples' actual experiences.

A simple solution to a largely complex problem?

3 / Jon Hilder

In my opinion the most important issue in workplace safety today is the behaviour or attitude of employees. This can range from good, bad or indifferent behaviour caused by a number of factors and not limited to such things as the working environment, the home environment and the people themselves. There is more and more pressure placed on employees to produce more and compete to the highest level that this can potentially cause stress and fatigue in some people.

They may have problems in their home environment and be experiencing trauma from marriage breakdown, custody issues or loss of loved ones.

Others may see safety as someone else's responsibility and will not participate unless there is "something in it for them".

Employees need to be motivated to change and the culture of risk-taking behaviour is influenced by the pressure of performance and an "it will never happen to me" attitude.

With all that has been said and done about attitude and behaviour, if the employee does not want to change his/her behaviour, as soon as they are out of site they will revert back to their old ways. It has been recorded where employees working long hours or nights have not intentionally done something outside of their normal behaviour but, without thinking, have placed themselves in a position where they have been injured.

To overcome these inherent risk-taking behaviours, management need to promote safety leadership by example, promote safety training and competencies of all employees and actively seek participation by employees in safety management of their workplaces.

Once these issues have been addressed and only then will employees embrace a safety culture and instinctively perform their tasks with a safety attitude.

4 / Mike Carter

An organisation can have in place all the appropriate regulatory measures, provide the appropriate tools and equipment for workplace safety, but at the end of the day these safety practices and management tools are part of everyone's job description.

To get through to the employee that it is their own personal responsibility to identify and correct hazards, wear the correct protective equipment, and that the safety committee is to be respected is probably the biggest hurdle today. The culture that can exist among employees of "I'm bulletproof" or "She'll be right" needs to be dissuaded by rewarding them for identifying potential or existing hazards and coming up with the appropriate preventative and corrective actions, whilst on the other hand enforcing the rules when the rules are ignored. At the end of the day, when unsafe work practices take place or hazard identification is ignored it's not just themselves that may have put at risk but others also and the consequences may have many ongoing effects on business and personal fronts for weeks, months, even years to come. "Effective safety starts between your ears, and not with your hands."

5 / Geoff Field

In my opinion, the most important issue in workplace safety today is a combination of awareness and responsibility. Most incidents are due to someone not doing the right thing, and this is often because they're (a) not aware that what they're doing is wrong, or (b) not taking responsibility for what they're doing. Everyone needs to switch their brains on and take charge of their lives.

6 / Jason Zealley

The most important issue in the workplace today would be working at heights, it affects almost every industry whether it's loading trucks at Safeway or working on housing.

There is a huge cost for all industries, I myself am a safety coordinator for a large construction company with over 300 employees and many sites to control and the biggest issue is trying to teach the old new ways.

Where the new can't see the risks and the consequences of falling more than 2 metres and turn a blind eye against their own personal safety and importantly other co-workers.

There is no tool out to teach personnel from these dangers, there are regulations but try to explain that in ways your personnel on-site understand, it's hard where they sign your work procedures in which they help to format - I just make it sound with the use of safety terms.

When these new regulations came about last year everyone could see they were necessary in some industries but what weren't thought about were what the effects would be and what was practicable and what was not. Anyway this is one of many concerns I have and I see in our everyday working environment.

7 / David Callander

As an Occupational Health and Safety co-ordinator for a workforce of 122 employees, being made up of both permanent and casual staff, that cover an area approximately 22,000 sq kilometres, I believe that one of the most important issues affecting OH&S is education.

Council workers are called upon to provide a large and varied range of tasks and through proper and effective education programs, the tasks are performed efficiently and safely.

A good education program not only enforces the importance of safety at the work sites, it also gives the workers the knowledge of their rights, ownership of theirs and their fellow workers' safety, security in the knowledge that the employer knows the benefits of providing a safe work environment, both for the employer and the employee.

Through regular updates and in-service education programs, the workers are also kept informed of current best practise and any changes in the industry.

Employees who understand and practise good risk management, are receptive to new ideas, change from the old habits to best practise, are keen to continue learning, make the life of an OH&S Coordinator a little easier. Education is the only way. Waiting to learn from mistakes is not an option.

8 / Craig Brogan

In my opinion we need to combat the area of complacency. It can be found in all areas of work no matter what the industry. You will find that where people regularly do the same task they will have less of an attention span to the task at hand, they assume that because they have been doing the same job for a period of time they know all of the dangers involved and as such are blind to the probability of the unforeseen circumstance arising.

Also when they train others in the same task they do not take a look at the whole picture and will invariably leave out important safety factors.

Example of complacency - a boilermaker or fitter will use safety glasses to grind a piece of steel in preparation for work, they then remove their safety glasses to have a closer inspection of the job and they find a small area that requires touching up with the grinder, they then use the grinder without safety glasses thinking "It's only a small area and shouldn't take long." Result - foreign body in eye.

We have a program at work where the employees sign a toolbox meeting sheet every morning, we regularly move the names around so that they have to look for their names prior to signing, thus showing them that things can change without their knowledge.

Container handling upgrade for rail freight operator

Four Konecranes Rail Mounted Gantry RMGs will go into operation as part of expansion and...

Hand protection for degreasers

Many degreasers are toxic, so Ansell advises that workers should make sure their hands are...

OHS Leaders Summit 2014

The OHS Leaders Summit 2014 is being held from 25-27 March 2014 at Surfers Paradise Marriot...

ISO Management systems and certifications with Quentic

Workplace Health & Safety Show returns to Sydney

Free IO-Link function blocks for parameterization and configuration of sensors and controllers

Welding safety — introducing the Speedglas Powered Air Training Academy

Cyclonic Waterproof Boot

Recycling sharps responsibly

- How to ensure ISO conformity and streamline your certification processes

- Camera innovations raise the bar for early fire detection in mining

- Big fan innovation delivers workplace heat safety and cuts your costs

- Heat stress at work: health & safety non-compliance

- Next-gen EHS platforms: what you need to know

- Comms Connect Melbourne 2024

- Workplace Health & Safety Show Sydney

Content from other channels on our network

Mandatory climate reporting: a game changer for Australian businesses

Australians unsure about food expiry labelling

Changes needed to decarbonise Australia's built environment

$2.2m in funding for council fleet electrification

Pathways for engineers to transition to renewable energy sector

Edible coatings to extend shelf life of produce

ACCC proposes to deny industry code on marketing of infant formula

Australia–UAE trade deal could benefit Aussie food producers

Schmackos dog treats now packaged with 60% recycled content

Aussie cold brew nitro tea maker to boost production after capital raise

Government invests in domestic rocket motor manufacturing

Testing carbon capture technology on a large scale

Rio Tinto to trial biofuel crop farming for renewable diesel production

BlueScope partners with Helios on low emissions steel technology

Chemical dosing tech to combat sulfide in sewers

- Advertising

- All content Copyright © 2024 Westwick-Farrow Pty Ltd

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- What Is an Adjective: Types, Uses, and Examples

How to Write a Reflective Essay

- Abstract vs. Introduction: What’s the Difference?

- How Do AI detectors Work? Breaking Down the Algorithm

- What is a Literature Review? Definition, Types, and Examples

- Why Is Your CV Getting Rejected and How to Avoid It

- Where to Find Images for Presentations

- What Is an Internship? Everything You Should Know

- How Long Should a Thesis Statement Be?

- How to Write a Character Analysis Essay

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

A complete guide to writing a reflective essay

(Last updated: 3 June 2024)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

“The overwhelming burden of writing my first ever reflective essay loomed over me as I sat as still as a statue, as my fingers nervously poised over the intimidating buttons on my laptop keyboard. Where would I begin? Where would I end? Nerve wracking thoughts filled my mind as I fretted over the seemingly impossible journey on which I was about to embark.”

Reflective essays may seem simple on the surface, but they can be a real stumbling block if you're not quite sure how to go about them. In simple terms, reflective essays constitute a critical examination of a life experience and, with the right guidance, they're not too challenging to put together. A reflective essay is similar to other essays in that it needs to be easily understood and well structured, but the content is more akin to something personal like a diary entry.

In this guide, we explore in detail how to write a great reflective essay , including what makes a good structure and some advice on the writing process. We’ve even thrown in an example reflective essay to inspire you too, making this the ultimate guide for anyone needing reflective essay help.

Types of Reflection Papers

There are several types of reflective papers, each serving a unique purpose. Educational reflection papers focus on your learning experiences, such as a course or a lecture, and how they have impacted your understanding. Professional reflection papers often relate to work experiences, discussing what you have learned in a professional setting and how it has shaped your skills and perspectives. Personal reflection papers delve into personal experiences and their influence on your personal growth and development.

Each of these requires a slightly different approach, but all aim to provide insight into your thoughts and experiences, demonstrating your ability to analyse and learn from them. Understanding the specific requirements of each type can help you tailor your writing to effectively convey your reflections.

Reflective Essay Format

In a reflective essay, a writer primarily examines his or her life experiences, hence the term ‘reflective’. The purpose of writing a reflective essay is to provide a platform for the author to not only recount a particular life experience, but to also explore how he or she has changed or learned from those experiences. Reflective writing can be presented in various formats, but you’ll most often see it in a learning log format or diary entry. Diary entries in particular are used to convey how the author’s thoughts have developed and evolved over the course of a particular period.

The format of a reflective essay may change depending on the target audience. Reflective essays can be academic, or may feature more broadly as a part of a general piece of writing for a magazine, for instance. For class assignments, while the presentation format can vary, the purpose generally remains the same: tutors aim to inspire students to think deeply and critically about a particular learning experience or set of experiences. Here are some typical examples of reflective essay formats that you may have to write:

A focus on personal growth:

A type of reflective essay often used by tutors as a strategy for helping students to learn how to analyse their personal life experiences to promote emotional growth and development. The essay gives the student a better understanding of both themselves and their behaviours.

A focus on the literature:

This kind of essay requires students to provide a summary of the literature, after which it is applied to the student’s own life experiences.

Pre-Writing Tips: How to Start Writing the Reflection Essay?

As you go about deciding on the content of your essay, you need to keep in mind that a reflective essay is highly personal and aimed at engaging the reader or target audience. And there’s much more to a reflective essay than just recounting a story. You need to be able to reflect (more on this later) on your experience by showing how it influenced your subsequent behaviours and how your life has been particularly changed as a result.

As a starting point, you might want to think about some important experiences in your life that have really impacted you, either positively, negatively, or both. Some typical reflection essay topics include: a real-life experience, an imagined experience, a special object or place, a person who had an influence on you, or something you have watched or read. If you are writing a reflective essay as part of an academic exercise, chances are your tutor will ask you to focus on a particular episode – such as a time when you had to make an important decision – and reflect on what the outcomes were. Note also, that the aftermath of the experience is especially important in a reflective essay; miss this out and you will simply be storytelling.

What Do You Mean By Reflection Essay?

It sounds obvious, but the reflective process forms the core of writing this type of essay, so it’s important you get it right from the outset. You need to really think about how the personal experience you have chosen to focus on impacted or changed you. Use your memories and feelings of the experience to determine the implications for you on a personal level.

Once you’ve chosen the topic of your essay, it’s really important you study it thoroughly and spend a lot of time trying to think about it vividly. Write down everything you can remember about it, describing it as clearly and fully as you can. Keep your five senses in mind as you do this, and be sure to use adjectives to describe your experience. At this stage, you can simply make notes using short phrases, but you need to ensure that you’re recording your responses, perceptions, and your experience of the event(s).

Once you’ve successfully emptied the contents of your memory, you need to start reflecting. A great way to do this is to pick out some reflection questions which will help you think deeper about the impact and lasting effects of your experience. Here are some useful questions that you can consider:

- What have you learned about yourself as a result of the experience?

- Have you developed because of it? How?

- Did it have any positive or negative bearing on your life?

- Looking back, what would you have done differently?

- Why do you think you made the particular choices that you did? Do you think these were the right choices?

- What are your thoughts on the experience in general? Was it a useful learning experience? What specific skills or perspectives did you acquire as a result?

These signpost questions should help kick-start your reflective process. Remember, asking yourself lots of questions is key to ensuring that you think deeply and critically about your experiences – a skill that is at the heart of writing a great reflective essay.

Consider using models of reflection (like the Gibbs or Kolb cycles) before, during, and after the learning process to ensure that you maintain a high standard of analysis. For example, before you really get stuck into the process, consider questions such as: what might happen (regarding the experience)? Are there any possible challenges to keep in mind? What knowledge is needed to be best prepared to approach the experience? Then, as you’re planning and writing, these questions may be useful: what is happening within the learning process? Is the process working out as expected? Am I dealing with the accompanying challenges successfully? Is there anything that needs to be done additionally to ensure that the learning process is successful? What am I learning from this? By adopting such a framework, you’ll be ensuring that you are keeping tabs on the reflective process that should underpin your work.

How to Strategically Plan Out the Reflective Essay Structure?

Here’s a very useful tip: although you may feel well prepared with all that time spent reflecting in your arsenal, do not, start writing your essay until you have worked out a comprehensive, well-rounded plan . Your writing will be so much more coherent, your ideas conveyed with structure and clarity, and your essay will likely achieve higher marks.

This is an especially important step when you’re tackling a reflective essay – there can be a tendency for people to get a little ‘lost’ or disorganised as they recount their life experiences in an erratic and often unsystematic manner as it is a topic so close to their hearts. But if you develop a thorough outline (this is the same as a ‘plan’) and ensure you stick to it like Christopher Columbus to a map, you should do just fine as you embark on the ultimate step of writing your essay. If you need further convincing on how important planning is, we’ve summarised the key benefits of creating a detailed essay outline below:

An outline allows you to establish the basic details that you plan to incorporate into your paper – this is great for helping you pick out any superfluous information, which can be removed entirely to make your essay succinct and to the point.

Think of the outline as a map – you plan in advance the points you wish to navigate through and discuss in your writing. Your work will more likely have a clear through line of thought, making it easier for the reader to understand. It’ll also help you avoid missing out any key information, and having to go back at the end and try to fit it in.

It’s a real time-saver! Because the outline essentially serves as the essay’s ‘skeleton’, you’ll save a tremendous amount of time when writing as you’ll be really familiar with what you want to say. As such, you’ll be able to allocate more time to editing the paper and ensuring it’s of a high standard.

Now you’re familiar with the benefits of using an outline for your reflective essay, it is essential that you know how to craft one. It can be considerably different from other typical essay outlines, mostly because of the varying subjects. But what remains the same, is that you need to start your outline by drafting the introduction, body and conclusion. More on this below.

Introduction

As is the case with all essays, your reflective essay must begin within an introduction that contains both a hook and a thesis statement. The point of having a ‘hook’ is to grab the attention of your audience or reader from the very beginning. You must portray the exciting aspects of your story in the initial paragraph so that you stand the best chances of holding your reader’s interest. Refer back to the opening quote of this article – did it grab your attention and encourage you to read more? The thesis statement is a brief summary of the focus of the essay, which in this case is a particular experience that influenced you significantly. Remember to give a quick overview of your experience – don’t give too much information away or you risk your reader becoming disinterested.

Next up is planning the body of your essay. This can be the hardest part of the entire paper; it’s easy to waffle and repeat yourself both in the plan and in the actual writing. Have you ever tried recounting a story to a friend only for them to tell you to ‘cut the long story short’? They key here is to put plenty of time and effort into planning the body, and you can draw on the following tips to help you do this well:

Try adopting a chronological approach. This means working through everything you want to touch upon as it happened in time. This kind of approach will ensure that your work is systematic and coherent. Keep in mind that a reflective essay doesn’t necessarily have to be linear, but working chronologically will prevent you from providing a haphazard recollection of your experience. Lay out the important elements of your experience in a timeline – this will then help you clearly see how to piece your narrative together.

Ensure the body of your reflective essay is well focused and contains appropriate critique and reflection. The body should not only summarise your experience, it should explore the impact that the experience has had on your life, as well as the lessons that you have learned as a result. The emphasis should generally be on reflection as opposed to summation. A reflective posture will not only provide readers with insight on your experience, it’ll highlight your personality and your ability to deal with or adapt to particular situations.

In the conclusion of your reflective essay, you should focus on bringing your piece together by providing a summary of both the points made throughout, and what you have learned as a result. Try to include a few points on why and how your attitudes and behaviours have been changed. Consider also how your character and skills have been affected, for example: what conclusions can be drawn about your problem-solving skills? What can be concluded about your approach to specific situations? What might you do differently in similar situations in the future? What steps have you taken to consolidate everything that you have learned from your experience? Keep in mind that your tutor will be looking out for evidence of reflection at a very high standard.

Congratulations – you now have the tools to create a thorough and accurate plan which should put you in good stead for the ultimate phase indeed of any essay, the writing process.

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Your Reflective Essay

As with all written assignments, sitting down to put pen to paper (or more likely fingers to keyboard) can be daunting. But if you have put in the time and effort fleshing out a thorough plan, you should be well prepared, which will make the writing process as smooth as possible. The following points should also help ease the writing process:

- To get a feel for the tone and format in which your writing should be, read other typically reflective pieces in magazines and newspapers, for instance.

- Don’t think too much about how to start your first sentence or paragraph; just start writing and you can always come back later to edit anything you’re not keen on. Your first draft won’t necessarily be your best essay writing work but it’s important to remember that the earlier you start writing, the more time you will have to keep reworking your paper until it’s perfect. Don’t shy away from using a free-flow method, writing and recording your thoughts and feelings on your experiences as and when they come to mind. But make sure you stick to your plan. Your plan is your roadmap which will ensure your writing doesn’t meander too far off course.

- For every point you make about an experience or event, support it by describing how you were directly impacted, using specific as opposed to vague words to convey exactly how you felt.

- Write using the first-person narrative, ensuring that the tone of your essay is very personal and reflective of your character.

- If you need to, refer back to our notes earlier on creating an outline. As you work through your essay, present your thoughts systematically, remembering to focus on your key learning outcomes.

- Consider starting your introduction with a short anecdote or quote to grasp your readers’ attention, or other engaging techniques such as flashbacks.

- Choose your vocabulary carefully to properly convey your feelings and emotions. Remember that reflective writing has a descriptive component and so must have a wide range of adjectives to draw from. Avoid vague adjectives such as ‘okay’ or ‘nice’ as they don’t really offer much insight into your feelings and personality. Be more specific – this will make your writing more engaging.

- Be honest with your feelings and opinions. Remember that this is a reflective task, and is the one place you can freely admit – without any repercussions – that you failed at a particular task. When assessing your essay, your tutor will expect a deep level of reflection, not a simple review of your experiences and emotion. Showing deep reflection requires you to move beyond the descriptive. Be extremely critical about your experience and your response to it. In your evaluation and analysis, ensure that you make value judgements, incorporating ideas from outside the experience you had to guide your analysis. Remember that you can be honest about your feelings without writing in a direct way. Use words that work for you and are aligned with your personality.

- Once you’ve finished learning about and reflecting on your experience, consider asking yourself these questions: what did I particularly value from the experience and why? Looking back, how successful has the process been? Think about your opinions immediately after the experience and how they differ now, so that you can evaluate the difference between your immediate and current perceptions. Asking yourself such questions will help you achieve reflective writing effectively and efficiently.

- Don’t shy away from using a variety of punctuation. It helps keeps your writing dynamic! Doesn’t it?

- If you really want to awaken your reader’s imagination, you can use imagery to create a vivid picture of your experiences.

- Ensure that you highlight your turning point, or what we like to call your “Aha!” moment. Without this moment, your resulting feelings and thoughts aren’t as valid and your argument not as strong.

- Don’t forget to keep reiterating the lessons you have learned from your experience.

Bonus Tip - Using Wider Sources

Although a reflective piece of writing is focused on personal experience, it’s important you draw on other sources to demonstrate your understanding of your experience from a theoretical perspective. It’ll show a level of analysis – and a standard of reliability in what you’re claiming – if you’re also able to validate your work against other perspectives that you find. Think about possible sources, like newspapers, surveys, books and even journal articles. Generally, the additional sources you decide to include in your work are highly dependent on your field of study. Analysing a wide range of sources, will show that you have read widely on your subject area, that you have nuanced insight into the available literature on the subject of your essay, and that you have considered the broader implications of the literature for your essay. The incorporation of other sources into your essay also helps to show that you are aware of the multi-dimensional nature of both the learning and problem-solving process.

Reflective Essay Example

If you want some inspiration for writing, take a look at our example of a short reflective essay , which can serve as a useful starting point for you when you set out to write your own.

Some Final Notes to Remember

To recap, the key to writing a reflective essay is demonstrating what lessons you have taken away from your experiences, and why and how you have been shaped by these lessons.

The reflective thinking process begins with you – you must consciously make an effort to identify and examine your own thoughts in relation to a particular experience. Don’t hesitate to explore any prior knowledge or experience of the topic, which will help you identify why you have formed certain opinions on the subject. Remember that central to reflective essay writing is the examination of your attitudes, assumptions and values, so be upfront about how you feel. Reflective writing can be quite therapeutic, helping you identify and clarify your strengths and weaknesses, particularly in terms of any knowledge gaps that you may have. It’s a pretty good way of improving your critical thinking skills, too. It enables you to adopt an introspective posture in analysing your experiences and how you learn/make sense of them.

If you are still having difficulties with starting the writing process, why not try mind-mapping which will help you to structure your thinking and ideas, enabling you to produce a coherent piece. Creating a mind map will ensure that your argument is written in a very systematic way that will be easy for your tutor to follow. Here’s a recap of the contents of this article, which also serves as a way to create a mind map:

1. Identify the topic you will be writing on.

2. Note down any ideas that are related to the topic and if you want to, try drawing a diagram to link together any topics, theories, and ideas.

3. Allow your ideas to flow freely, knowing that you will always have time to edit your reflective essay .

4. Consider how your ideas are connected to each other, then begin the writing process.