Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Gathering and Analyzing Qualitative Data

Gathering and analyzing qualitative data.

As the role of clinician researchers expands beyond the bedside, it is important to consider the possibilities of inquiry beyond the quantitative approach. In contrast to the quantitative approach, qualitative methodology is highly inductive and relies on the background and interpretation of the researcher to derive meaning from the gathering and analytic processes central to qualitative inquiry.

Chapter 4: Learning Objectives

As you explore the research opportunities central to your interests to consider whether qualitative component would enrich your work, you’ll be able to:

- Define what qualitative research is

- Compare qualitative and quantitative approaches

- Describe the process of creating themes from recurring ideas gleaned from narrative interviews

What Is Qualitative Research?

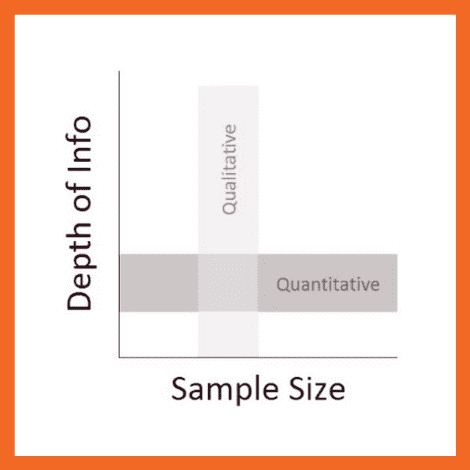

Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of numerical data from a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this method is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in fields such as respiratory care and other clinical fields, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques, such as grounded theory, thematic analysis, critical discourse analysis, or interpretative phenomenological analysis. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008). They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To address this question, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This method is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, and that female undergraduate students are not substantially more talkative than male undergraduate students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And quantitative research is not very good at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this depth is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973) .

Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this detail. The table below lists some contrasts between qualitative and quantitative research

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

Data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, participant observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews. Interviews in qualitative research can be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them—or structured, where there is a strict script that the interviewer does not deviate from. Most interviews are in between the two and are called semi-structured interviews, where the researcher has a few consistent questions and can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. The unstructured interview was the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide victims because the researchers were aware that how much was disclosed about such a sensitive topic should be led by the families, not by the researchers.

Another approach used in qualitative research involves small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue, known as focus groups. The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one- on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses. However, we know from social psychology that group dynamics are often at play in any group, including focus groups, and it is useful to be aware of those possibilities. For example, the desire to be liked by others can lead participants to provide inaccurate answers that they believe will be perceived favorably by the other participants. The same may be said for personality characteristics. For example, highly extraverted participants can sometimes dominate discussions within focus groups.

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with people recovering from alcohol use disorder to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this project sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) . This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this analysis in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative—an interpretation of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

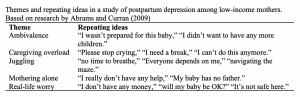

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009) . Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. The table below hows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

“Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk….Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)”

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms, not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances. The table below illustrates the process of creating themes from repeating ideas in the qualitative research gathering and analysis process.

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004). In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches. One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables in a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation. The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Using qualitative research can often help clarify quantitative results via triangulation. Trenor, Yu, Waight, Zerda, and Sha (2008) investigated the experience of female engineering students at a university. In the first phase, female engineering students were asked to complete a survey, where they rated a number of their perceptions, including their sense of belonging. Their results were compared across the student ethnicities, and statistically, the various ethnic groups showed no differences in their ratings of their sense of belonging.

One might look at that result and conclude that ethnicity does not have anything to do with one’s sense of belonging. However, in the second phase, the authors also conducted interviews with the students, and in those interviews, many minority students reported how the diversity of cultures at the university enhanced their sense of belonging. Without the qualitative component, we might have drawn the wrong conclusion about the quantitative results.

This example shows how qualitative and quantitative research work together to help us understand human behavior. Some researchers have characterized qualitative research as best for identifying behaviors or the phenomenon whereas quantitative research is best for understanding meaning or identifying the mechanism. However, Bryman (2012) argues for breaking down the divide between these arbitrarily different ways of investigating the same questions.

Key Takeaways

- The qualitative approach is centered on an inductive method of reasoning

- The qualitative approach focuses on understanding phenomenon through the perspective of those experiencing it

- Researchers search for recurring topics and group themes to build upon theory to explain findings

- A mixed methods approach uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to explain different aspects of a phenomenon, processes, or practice

- This chapter can be attributed to Research Methods in Psychology by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. This adaptation constitutes the fourth edition of this textbook, and builds upon the second Canadian edition by Rajiv S. Jhangiani (Kwantlen Polytechnic University) and I-Chant A. Chiang (Quest University Canada), the second American edition by Dana C. Leighton (Texas A&M University-Texarkana), and the third American edition by Carrie Cuttler (Washington State University) and feedback from several peer reviewers coordinated by the Rebus Community. This edition is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

Gathering and Analyzing Qualitative Data Copyright © by megankoster is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Chapter 10. Introduction to Data Collection Techniques

Introduction.

Now that we have discussed various aspects of qualitative research, we can begin to collect data. This chapter serves as a bridge between the first half and second half of this textbook (and perhaps your course) by introducing techniques of data collection. You’ve already been introduced to some of this because qualitative research is often characterized by the form of data collection; for example, an ethnographic study is one that employs primarily observational data collection for the purpose of documenting and presenting a particular culture or ethnos. Thus, some of this chapter will operate as a review of material already covered, but we will be approaching it from the data-collection side rather than the tradition-of-inquiry side we explored in chapters 2 and 4.

Revisiting Approaches

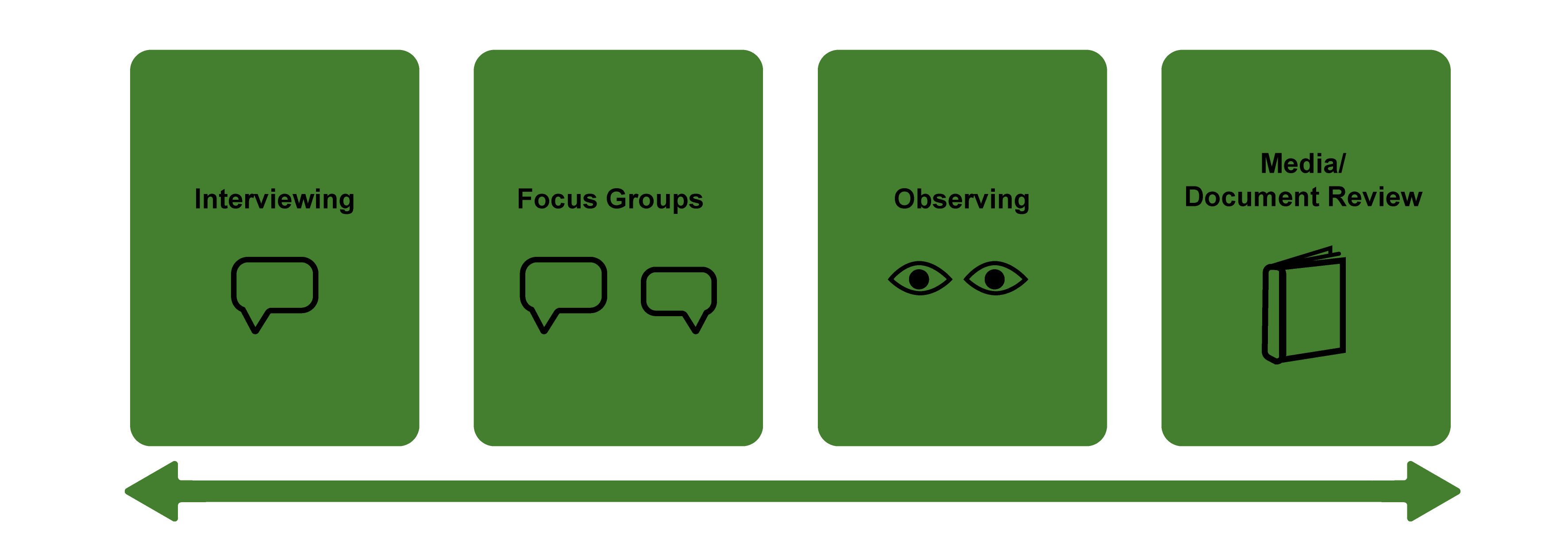

There are four primary techniques of data collection used in qualitative research: interviews, focus groups, observations, and document review. [1] There are other available techniques, such as visual analysis (e.g., photo elicitation) and biography (e.g., autoethnography) that are sometimes used independently or supplementarily to one of the main forms. Not to confuse you unduly, but these various data collection techniques are employed differently by different qualitative research traditions so that sometimes the technique and the tradition become inextricably entwined. This is largely the case with observations and ethnography. The ethnographic tradition is fundamentally based on observational techniques. At the same time, traditions other than ethnography also employ observational techniques, so it is worthwhile thinking of “tradition” and “technique” separately (see figure 10.1).

| TYPE | As in... | Approaches where you commonly see this technique... | Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview-based studies | ; Ethnography (along with Observations); Mixed Methods; Grounded Theory; Narrative Inquiry; Feminist Approaches | Semi-structured or unstructured interviews with one to 100 participants, depending on tradition | |

| Case Study; Feminist Approaches; Mixed Methods; often used as a supplementary technique | SIngle or comparative focused discussions with 5-12 persons | ||

| Participant-observation studies; ethnographic studies | ; Grounded Theory; Symbolic Interactionism; Case Study | Multiple observations in "field," with written fieldnotes serving as the data | |

| Historical or archival research or content analysis | ; Content Analysis; Narrative Inquiry; Mixed Methods | Systematic and rigorous analyses of documents employing coding techniques | |

| Photo/drawing elicitations; photovoice | Phenomenology; Grounded Theory; Ethnography | Supplemental technique asking participants to draw/explain or view/explain visual material | |

| Autoethnography; Oral Histories | Narrative Inquiry; Case Study; Oral History | Largely chronologically-structured collection of a person's life history; can be a single illustrative case |

Figure 10.1. Data Collection Techniques

Each of these data collection techniques will be the subject of its own chapter in the second half of this textbook. This chapter serves as an orienting overview and as the bridge between the conceptual/design portion of qualitative research and the actual practice of conducting qualitative research.

Overview of the Four Primary Approaches

Interviews are at the heart of qualitative research. Returning to epistemological foundations, it is during the interview that the researcher truly opens herself to hearing what others have to say, encouraging her interview subjects to reflect deeply on the meanings and values they hold. Interviews are used in almost every qualitative tradition but are particularly salient in phenomenological studies, studies seeking to understand the meaning of people’s lived experiences.

Focus groups can be seen as a type of interview, one in which a group of persons (ideally between five and twelve) is asked a series of questions focused on a particular topic or subject. They are sometimes used as the primary form of data collection, especially outside academic research. For example, businesses often employ focus groups to determine if a particular product is likely to sell. Among qualitative researchers, it is often used in conjunction with any other primary data collection technique as a form of “triangulation,” or a way of increasing the reliability of the study by getting at the object of study from multiple directions. [2] Some traditions, such as feminist approaches, also see the focus group as an important “consciousness-raising” tool.

If interviews are at the heart of qualitative research, observations are its lifeblood. Researchers who are more interested in the practices and behaviors of people than what they think or who are trying to understand the parameters of an organizational culture rely on observations as their primary form of data collection. The notes they make “in the field” (either during observations or afterward) form the “data” that will be analyzed. Ethnographers, those seeking to describe a particular ethnos, or culture, believe that observations are more reliable guides to that culture than what people have to say about it. Observations are thus the primary form of data collection for ethnographers, albeit often supplemented with in-depth interviews.

Some would say that these three—interviews, focus groups, and observations—are really the foundational techniques of data collection. They are far and away the three techniques most frequently used separately, in conjunction with one another, and even sometimes in mixed methods qualitative/quantitative studies. Document review, either as a form of content analysis or separately, however, is an important addition to the qualitative researcher’s toolkit and should not be overlooked (figure 10.1). Although it is rare for a qualitative researcher to make document review their primary or sole form of data collection, including documents in the research design can help expand the reach and the reliability of a study. Document review can take many forms, from historical and archival research, in which the researcher pieces together a narrative of the past by finding and analyzing a variety of “documents” and records (including photographs and physical artifacts), to analyses of contemporary media content, as in the case of compiling and coding blog posts or other online commentaries, and content analysis that identifies and describes communicative aspects of media or documents.

In addition to these four major techniques, there are a host of emerging and incidental data collection techniques, from photo elicitation or photo voice, in which respondents are asked to comment upon a photograph or image (particularly useful as a supplement to interviews when the respondents are hesitant or unable to answer direct questions), to autoethnographies, in which the researcher uses his own position and life to increase our understanding about a phenomenon and its historical and social context.

Taken together, these techniques provide a wide range of practices and tools with which to discover the world. They are particularly suited to addressing the questions that qualitative researchers ask—questions about how things happen and why people act the way they do, given particular social contexts and shared meanings about the world (chapter 4).

Triangulation and Mixed Methods

Because the researcher plays such a large and nonneutral role in qualitative research, one that requires constant reflectivity and awareness (chapter 6), there is a constant need to reassure her audience that the results she finds are reliable. Quantitative researchers can point to any number of measures of statistical significance to reassure their audiences, but qualitative researchers do not have math to hide behind. And she will also want to reassure herself that what she is hearing in her interviews or observing in the field is a true reflection of what is going on (or as “true” as possible, given the problem that the world is as large and varied as the elephant; see chapter 3). For those reasons, it is common for researchers to employ more than one data collection technique or to include multiple and comparative populations, settings, and samples in the research design (chapter 2). A single set of interviews or initial comparison of focus groups might be conceived as a “pilot study” from which to launch the actual study. Undergraduate students working on a research project might be advised to think about their projects in this way as well. You are simply not going to have enough time or resources as an undergraduate to construct and complete a successful qualitative research project, but you may be able to tackle a pilot study. Graduate students also need to think about the amount of time and resources they have for completing a full study. Masters-level students, or students who have one year or less in which to complete a program, should probably consider their study as an initial exploratory pilot. PhD candidates might have the time and resources to devote to the type of triangulated, multifaceted research design called for by the research question.

We call the use of multiple qualitative methods of data collection and the inclusion of multiple and comparative populations and settings “triangulation.” Using different data collection methods allows us to check the consistency of our findings. For example, a study of the vaccine hesitant might include a set of interviews with vaccine-hesitant people and a focus group of the same and a content analysis of online comments about a vaccine mandate. By employing all three methods, we can be more confident of our interpretations from the interviews alone (especially if we are hearing the same thing throughout; if we are not, then this is a good sign that we need to push a little further to find out what is really going on). [3] Methodological triangulation is an important tool for increasing the reliability of our findings and the overall success of our research.

Methodological triangulation should not be confused with mixed methods techniques, which refer instead to the combining of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Mixed methods studies can increase reliability, but that is not their primary purpose. Mixed methods address multiple research questions, both the “how many” and “why” kind, or the causal and explanatory kind. Mixed methods will be discussed in more detail in chapter 15.

Let us return to the three examples of qualitative research described in chapter 1: Cory Abramson’s study of aging ( The End Game) , Jennifer Pierce’s study of lawyers and discrimination ( Racing for Innocence ), and my own study of liberal arts college students ( Amplified Advantage ). Each of these studies uses triangulation.

Abramson’s book is primarily based on three years of observations in four distinct neighborhoods. He chose the neighborhoods in such a way to maximize his ability to make comparisons: two were primarily middle class and two were primarily poor; further, within each set, one was predominantly White, while the other was either racially diverse or primarily African American. In each neighborhood, he was present in senior centers, doctors’ offices, public transportation, and other public spots where the elderly congregated. [4] The observations are the core of the book, and they are richly written and described in very moving passages. But it wasn’t enough for him to watch the seniors. He also engaged with them in casual conversation. That, too, is part of fieldwork. He sometimes even helped them make it to the doctor’s office or get around town. Going beyond these interactions, he also interviewed sixty seniors, an equal amount from each of the four neighborhoods. It was in the interviews that he could ask more detailed questions about their lives, what they thought about aging, what it meant to them to be considered old, and what their hopes and frustrations were. He could see that those living in the poor neighborhoods had a more difficult time accessing care and resources than those living in the more affluent neighborhoods, but he couldn’t know how the seniors understood these difficulties without interviewing them. Both forms of data collection supported each other and helped make the study richer and more insightful. Interviews alone would have failed to demonstrate the very real differences he observed (and that some seniors would not even have known about). This is the value of methodological triangulation.

Pierce’s book relies on two separate forms of data collection—interviews with lawyers at a firm that has experienced a history of racial discrimination and content analyses of news stories and popular films that screened during the same years of the alleged racial discrimination. I’ve used this book when teaching methods and have often found students struggle with understanding why these two forms of data collection were used. I think this is because we don’t teach students to appreciate or recognize “popular films” as a legitimate form of data. But what Pierce does is interesting and insightful in the best tradition of qualitative research. Here is a description of the content analyses from a review of her book:

In the chapter on the news media, Professor Pierce uses content analysis to argue that the media not only helped shape the meaning of affirmative action, but also helped create white males as a class of victims. The overall narrative that emerged from these media accounts was one of white male innocence and victimization. She also maintains that this narrative was used to support “neoconservative and neoliberal political agendas” (p. 21). The focus of these articles tended to be that affirmative action hurt white working-class and middle-class men particularly during the recession in the 1980s (despite statistical evidence that people of color were hurt far more than white males by the recession). In these stories fairness and innocence were seen in purely individual terms. Although there were stories that supported affirmative action and developed a broader understanding of fairness, the total number of stories slanted against affirmative action from 1990 to 1999. During that time period negative stories always outnumbered those supporting the policy, usually by a ratio of 3:1 or 3:2. Headlines, the presentation of polling data, and an emphasis in stories on racial division, Pierce argues, reinforced the story of white male victimization. Interestingly, the news media did very few stories on gender and affirmative action. The chapter on the film industry from 1989 to 1999 reinforces Pierce’s argument and adds another layer to her interpretation of affirmative action during this time period. She sampled almost 60 Hollywood films with receipts ranging from four million to 184 million dollars. In this chapter she argues that the dominant theme of these films was racial progress and the redemption of white Americans from past racism. These movies usually portrayed white, elite, and male experiences. People of color were background figures who supported the protagonist and “anointed” him as a savior (p. 45). Over the course of the film the protagonists move from “innocence to consciousness” concerning racism. The antagonists in these films most often were racist working-class white men. A Time to Kill , Mississippi Burning , Amistad , Ghosts of Mississippi , The Long Walk Home , To Kill a Mockingbird , and Dances with Wolves receive particular analysis in this chapter, and her examination of them leads Pierce to conclude that they infused a myth of racial progress into America’s cultural memory. White experiences of race are the focus and contemporary forms of racism are underplayed or omitted. Further, these films stereotype both working-class and elite white males, and underscore the neoliberal emphasis on individualism. ( Hrezo 2012 )

With that context in place, Pierce then turned to interviews with attorneys. She finds that White male attorneys often misremembered facts about the period in which the law firm was accused of racial discrimination and that they often portrayed their firms as having made substantial racial progress. This was in contrast to many of the lawyers of color and female lawyers who remembered the history differently and who saw continuing examples of racial (and gender) discrimination at the law firm. In most of the interviews, people talked about individuals, not structure (and these are attorneys, who really should know better!). By including both content analyses and interviews in her study, Pierce is better able to situate the attorney narratives and explain the larger context for the shared meanings of individual innocence and racial progress. Had this been a study only of films during this period, we would not know how actual people who lived during this period understood the decisions they made; had we had only the interviews, we would have missed the historical context and seen a lot of these interviewees as, well, not very nice people at all. Together, we have a study that is original, inventive, and insightful.

My own study of how class background affects the experiences and outcomes of students at small liberal arts colleges relies on mixed methods and triangulation. At the core of the book is an original survey of college students across the US. From analyses of this survey, I can present findings on “how many” questions and descriptive statistics comparing students of different social class backgrounds. For example, I know and can demonstrate that working-class college students are less likely to go to graduate school after college than upper-class college students are. I can even give you some estimates of the class gap. But what I can’t tell you from the survey is exactly why this is so or how it came to be so . For that, I employ interviews, focus groups, document reviews, and observations. Basically, I threw the kitchen sink at the “problem” of class reproduction and higher education (i.e., Does college reduce class inequalities or make them worse?). A review of historical documents provides a picture of the place of the small liberal arts college in the broader social and historical context. Who had access to these colleges and for what purpose have always been in contest, with some groups attempting to exclude others from opportunities for advancement. What it means to choose a small liberal arts college in the early twenty-first century is thus different for those whose parents are college professors, for those whose parents have a great deal of money, and for those who are the first in their family to attend college. I was able to get at these different understandings through interviews and focus groups and to further delineate the culture of these colleges by careful observation (and my own participation in them, as both former student and current professor). Putting together individual meanings, student dispositions, organizational culture, and historical context allowed me to present a story of how exactly colleges can both help advance first-generation, low-income, working-class college students and simultaneously amplify the preexisting advantages of their peers. Mixed methods addressed multiple research questions, while triangulation allowed for this deeper, more complex story to emerge.

In the next few chapters, we will explore each of the primary data collection techniques in much more detail. As we do so, think about how these techniques may be productively joined for more reliable and deeper studies of the social world.

Advanced Reading: Triangulation

Denzin ( 1978 ) identified four basic types of triangulation: data, investigator, theory, and methodological. Properly speaking, if we use the Denzin typology, the use of multiple methods of data collection and analysis to strengthen one’s study is really a form of methodological triangulation. It may be helpful to understand how this differs from the other types.

Data triangulation occurs when the researcher uses a variety of sources in a single study. Perhaps they are interviewing multiple samples of college students. Obviously, this overlaps with sample selection (see chapter 5). It is helpful for the researcher to understand that these multiple data sources add strength and reliability to the study. After all, it is not just “these students here” but also “those students over there” that are experiencing this phenomenon in a particular way.

Investigator triangulation occurs when different researchers or evaluators are part of the research team. Intercoding reliability is a form of investigator triangulation (or at least a way of leveraging the power of multiple researchers to raise the reliability of the study).

Theory triangulation is the use of multiple perspectives to interpret a single set of data, as in the case of competing theoretical paradigms (e.g., a human capital approach vs. a Bourdieusian multiple capital approach).

Methodological triangulation , as explained in this chapter, is the use of multiple methods to study a single phenomenon, issue, or problem.

Further Readings

Carter, Nancy, Denise Bryant-Lukosius, Alba DiCenso, Jennifer Blythe, Alan J. Neville. 2014. “The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research.” Oncology Nursing Forum 41(5):545–547. Discusses the four types of triangulation identified by Denzin with an example of the use of focus groups and in-depth individuals.

Mathison, Sandra. 1988. “Why Triangulate?” Educational Researcher 17(2):13–17. Presents three particular ways of assessing validity through the use of triangulated data collection: convergence, inconsistency, and contradiction.

Tracy, Sarah J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight ‘Big-Tent’ Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16(10):837–851. Focuses on triangulation as a criterion for conducting valid qualitative research.

- Marshall and Rossman ( 2016 ) state this slightly differently. They list four primary methods for gathering information: (1) participating in the setting, (2) observing directly, (3) interviewing in depth, and (4) analyzing documents and material culture (141). An astute reader will note that I have collapsed participation into observation and that I have distinguished focus groups from interviews. I suspect that this distinction marks me as more of an interview-based researcher, while Marshall and Rossman prioritize ethnographic approaches. The main point of this footnote is to show you, the reader, that there is no single agreed-upon number of approaches to collecting qualitative data. ↵

- See “ Advanced Reading: Triangulation ” at end of this chapter. ↵

- We can also think about triangulating the sources, as when we include comparison groups in our sample (e.g., if we include those receiving vaccines, we might find out a bit more about where the real differences lie between them and the vaccine hesitant); triangulating the analysts (building a research team so that your interpretations can be checked against those of others on the team); and even triangulating the theoretical perspective (as when we “try on,” say, different conceptualizations of social capital in our analyses). ↵

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 24, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 22 March 2008

Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups

- P. Gill 1 ,

- K. Stewart 2 ,

- E. Treasure 3 &

- B. Chadwick 4

British Dental Journal volume 204 , pages 291–295 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

1.70m Accesses

1064 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

Interviews and focus groups are the most common methods of data collection used in qualitative healthcare research

Interviews can be used to explore the views, experiences, beliefs and motivations of individual participants

Focus group use group dynamics to generate qualitative data

Qualitative research in dentistry

Conducting qualitative interviews with school children in dental research

Analysing and presenting qualitative data

This paper explores the most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. The paper examines each method in detail, focusing on how they work in practice, when their use is appropriate and what they can offer dentistry. Examples of empirical studies that have used interviews or focus groups are also provided.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interviews in the social sciences

A review of technical and quality assessment considerations of audio-visual and web-conferencing focus groups in qualitative health research

Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common terminology, introduction.

Having explored the nature and purpose of qualitative research in the previous paper, this paper explores methods of data collection used in qualitative research. There are a variety of methods of data collection in qualitative research, including observations, textual or visual analysis (eg from books or videos) and interviews (individual or group). 1 However, the most common methods used, particularly in healthcare research, are interviews and focus groups. 2 , 3

The purpose of this paper is to explore these two methods in more detail, in particular how they work in practice, the purpose of each, when their use is appropriate and what they can offer dental research.

Qualitative research interviews

There are three fundamental types of research interviews: structured, semi-structured and unstructured. Structured interviews are, essentially, verbally administered questionnaires, in which a list of predetermined questions are asked, with little or no variation and with no scope for follow-up questions to responses that warrant further elaboration. Consequently, they are relatively quick and easy to administer and may be of particular use if clarification of certain questions are required or if there are likely to be literacy or numeracy problems with the respondents. However, by their very nature, they only allow for limited participant responses and are, therefore, of little use if 'depth' is required.

Conversely, unstructured interviews do not reflect any preconceived theories or ideas and are performed with little or no organisation. 4 Such an interview may simply start with an opening question such as 'Can you tell me about your experience of visiting the dentist?' and will then progress based, primarily, upon the initial response. Unstructured interviews are usually very time-consuming (often lasting several hours) and can be difficult to manage, and to participate in, as the lack of predetermined interview questions provides little guidance on what to talk about (which many participants find confusing and unhelpful). Their use is, therefore, generally only considered where significant 'depth' is required, or where virtually nothing is known about the subject area (or a different perspective of a known subject area is required).

Semi-structured interviews consist of several key questions that help to define the areas to be explored, but also allows the interviewer or interviewee to diverge in order to pursue an idea or response in more detail. 2 This interview format is used most frequently in healthcare, as it provides participants with some guidance on what to talk about, which many find helpful. The flexibility of this approach, particularly compared to structured interviews, also allows for the discovery or elaboration of information that is important to participants but may not have previously been thought of as pertinent by the research team.

For example, in a recent dental public heath study, 5 school children in Cardiff, UK were interviewed about their food choices and preferences. A key finding that emerged from semi-structured interviews, which was not previously thought to be as highly influential as the data subsequently confirmed, was the significance of peer-pressure in influencing children's food choices and preferences. This finding was also established primarily through follow-up questioning (eg probing interesting responses with follow-up questions, such as 'Can you tell me a bit more about that?') and, therefore, may not have emerged in the same way, if at all, if asked as a predetermined question.

The purpose of research interviews

The purpose of the research interview is to explore the views, experiences, beliefs and/or motivations of individuals on specific matters (eg factors that influence their attendance at the dentist). Qualitative methods, such as interviews, are believed to provide a 'deeper' understanding of social phenomena than would be obtained from purely quantitative methods, such as questionnaires. 1 Interviews are, therefore, most appropriate where little is already known about the study phenomenon or where detailed insights are required from individual participants. They are also particularly appropriate for exploring sensitive topics, where participants may not want to talk about such issues in a group environment.

Examples of dental studies that have collected data using interviews are 'Examining the psychosocial process involved in regular dental attendance' 6 and 'Exploring factors governing dentists' treatment philosophies'. 7 Gibson et al . 6 provided an improved understanding of factors that influenced people's regular attendance with their dentist. The study by Kay and Blinkhorn 7 provided a detailed insight into factors that influenced GDPs' decision making in relation to treatment choices. The study found that dentists' clinical decisions about treatments were not necessarily related to pathology or treatment options, as was perhaps initially thought, but also involved discussions with patients, patients' values and dentists' feelings of self esteem and conscience.

There are many similarities between clinical encounters and research interviews, in that both employ similar interpersonal skills, such as questioning, conversing and listening. However, there are also some fundamental differences between the two, such as the purpose of the encounter, reasons for participating, roles of the people involved and how the interview is conducted and recorded. 8

The primary purpose of clinical encounters is for the dentist to ask the patient questions in order to acquire sufficient information to inform decision making and treatment options. However, the constraints of most consultations are such that any open-ended questioning needs to be brought to a conclusion within a fairly short time. 2 In contrast, the fundamental purpose of the research interview is to listen attentively to what respondents have to say, in order to acquire more knowledge about the study topic. 9 Unlike the clinical encounter, it is not to intentionally offer any form of help or advice, which many researchers have neither the training nor the time for. Research interviewing therefore requires a different approach and a different range of skills.

The interview

When designing an interview schedule it is imperative to ask questions that are likely to yield as much information about the study phenomenon as possible and also be able to address the aims and objectives of the research. In a qualitative interview, good questions should be open-ended (ie, require more than a yes/no answer), neutral, sensitive and understandable. 2 It is usually best to start with questions that participants can answer easily and then proceed to more difficult or sensitive topics. 2 This can help put respondents at ease, build up confidence and rapport and often generates rich data that subsequently develops the interview further.

As in any research, it is often wise to first pilot the interview schedule on several respondents prior to data collection proper. 8 This allows the research team to establish if the schedule is clear, understandable and capable of answering the research questions, and if, therefore, any changes to the interview schedule are required.

The length of interviews varies depending on the topic, researcher and participant. However, on average, healthcare interviews last 20-60 minutes. Interviews can be performed on a one-off or, if change over time is of interest, repeated basis, 4 for example exploring the psychosocial impact of oral trauma on participants and their subsequent experiences of cosmetic dental surgery.

Developing the interview

Before an interview takes place, respondents should be informed about the study details and given assurance about ethical principles, such as anonymity and confidentiality. 2 This gives respondents some idea of what to expect from the interview, increases the likelihood of honesty and is also a fundamental aspect of the informed consent process.

Wherever possible, interviews should be conducted in areas free from distractions and at times and locations that are most suitable for participants. For many this may be at their own home in the evenings. Whilst researchers may have less control over the home environment, familiarity may help the respondent to relax and result in a more productive interview. 9 Establishing rapport with participants prior to the interview is also important as this can also have a positive effect on the subsequent development of the interview.

When conducting the actual interview it is prudent for the interviewer to familiarise themselves with the interview schedule, so that the process appears more natural and less rehearsed. However, to ensure that the interview is as productive as possible, researchers must possess a repertoire of skills and techniques to ensure that comprehensive and representative data are collected during the interview. 10 One of the most important skills is the ability to listen attentively to what is being said, so that participants are able to recount their experiences as fully as possible, without unnecessary interruptions.

Other important skills include adopting open and emotionally neutral body language, nodding, smiling, looking interested and making encouraging noises (eg, 'Mmmm') during the interview. 2 The strategic use of silence, if used appropriately, can also be highly effective at getting respondents to contemplate their responses, talk more, elaborate or clarify particular issues. Other techniques that can be used to develop the interview further include reflecting on remarks made by participants (eg, 'Pain?') and probing remarks ('When you said you were afraid of going to the dentist what did you mean?'). 9 Where appropriate, it is also wise to seek clarification from respondents if it is unclear what they mean. The use of 'leading' or 'loaded' questions that may unduly influence responses should always be avoided (eg, 'So you think dental surgery waiting rooms are frightening?' rather than 'How do you find the waiting room at the dentists?').

At the end of the interview it is important to thank participants for their time and ask them if there is anything they would like to add. This gives respondents an opportunity to deal with issues that they have thought about, or think are important but have not been dealt with by the interviewer. 9 This can often lead to the discovery of new, unanticipated information. Respondents should also be debriefed about the study after the interview has finished.

All interviews should be tape recorded and transcribed verbatim afterwards, as this protects against bias and provides a permanent record of what was and was not said. 8 It is often also helpful to make 'field notes' during and immediately after each interview about observations, thoughts and ideas about the interview, as this can help in data analysis process. 4 , 8

Focus groups

Focus groups share many common features with less structured interviews, but there is more to them than merely collecting similar data from many participants at once. A focus group is a group discussion on a particular topic organised for research purposes. This discussion is guided, monitored and recorded by a researcher (sometimes called a moderator or facilitator). 11 , 12

Focus groups were first used as a research method in market research, originating in the 1940s in the work of the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University. Eventually the success of focus groups as a marketing tool in the private sector resulted in its use in public sector marketing, such as the assessment of the impact of health education campaigns. 13 However, focus group techniques, as used in public and private sectors, have diverged over time. Therefore, in this paper, we seek to describe focus groups as they are used in academic research.

When focus groups are used

Focus groups are used for generating information on collective views, and the meanings that lie behind those views. They are also useful in generating a rich understanding of participants' experiences and beliefs. 12 Suggested criteria for using focus groups include: 13

As a standalone method, for research relating to group norms, meanings and processes

In a multi-method design, to explore a topic or collect group language or narratives to be used in later stages

To clarify, extend, qualify or challenge data collected through other methods

To feedback results to research participants.

Morgan 12 suggests that focus groups should be avoided according to the following criteria:

If listening to participants' views generates expectations for the outcome of the research that can not be fulfilled

If participants are uneasy with each other, and will therefore not discuss their feelings and opinions openly

If the topic of interest to the researcher is not a topic the participants can or wish to discuss

If statistical data is required. Focus groups give depth and insight, but cannot produce useful numerical results.

Conducting focus groups: group composition and size

The composition of a focus group needs great care to get the best quality of discussion. There is no 'best' solution to group composition, and group mix will always impact on the data, according to things such as the mix of ages, sexes and social professional statuses of the participants. What is important is that the researcher gives due consideration to the impact of group mix (eg, how the group may interact with each other) before the focus group proceeds. 14

Interaction is key to a successful focus group. Sometimes this means a pre-existing group interacts best for research purposes, and sometimes stranger groups. Pre-existing groups may be easier to recruit, have shared experiences and enjoy a comfort and familiarity which facilitates discussion or the ability to challenge each other comfortably. In health settings, pre-existing groups can overcome issues relating to disclosure of potentially stigmatising status which people may find uncomfortable in stranger groups (conversely there may be situations where disclosure is more comfortable in stranger groups). In other research projects it may be decided that stranger groups will be able to speak more freely without fear of repercussion, and challenges to other participants may be more challenging and probing, leading to richer data. 13

Group size is an important consideration in focus group research. Stewart and Shamdasani 14 suggest that it is better to slightly over-recruit for a focus group and potentially manage a slightly larger group, than under-recruit and risk having to cancel the session or having an unsatisfactory discussion. They advise that each group will probably have two non-attenders. The optimum size for a focus group is six to eight participants (excluding researchers), but focus groups can work successfully with as few as three and as many as 14 participants. Small groups risk limited discussion occurring, while large groups can be chaotic, hard to manage for the moderator and frustrating for participants who feel they get insufficient opportunities to speak. 13

Preparing an interview schedule

Like research interviews, the interview schedule for focus groups is often no more structured than a loose schedule of topics to be discussed. However, in preparing an interview schedule for focus groups, Stewart and Shamdasani 14 suggest two general principles:

Questions should move from general to more specific questions

Question order should be relative to importance of issues in the research agenda.

There can, however, be some conflict between these two principles, and trade offs are often needed, although often discussions will take on a life of their own, which will influence or determine the order in which issues are covered. Usually, less than a dozen predetermined questions are needed and, as with research interviews, the researcher will also probe and expand on issues according to the discussion.

Moderating a focus group looks easy when done well, but requires a complex set of skills, which are related to the following principles: 15

Participants have valuable views and the ability to respond actively, positively and respectfully. Such an approach is not simply a courtesy, but will encourage fruitful discussions

Moderating without participating: a moderator must guide a discussion rather than join in with it. Expressing one's own views tends to give participants cues as to what to say (introducing bias), rather than the confidence to be open and honest about their own views

Be prepared for views that may be unpalatably critical of a topic which may be important to you

It is important to recognise that researchers' individual characteristics mean that no one person will always be suitable to moderate any kind of group. Sometimes the characteristics that suit a moderator for one group will inhibit discussion in another

Be yourself. If the moderator is comfortable and natural, participants will feel relaxed.

The moderator should facilitate group discussion, keeping it focussed without leading it. They should also be able to prevent the discussion being dominated by one member (for example, by emphasising at the outset the importance of hearing a range of views), ensure that all participants have ample opportunity to contribute, allow differences of opinions to be discussed fairly and, if required, encourage reticent participants. 13

Other relevant factors

The venue for a focus group is important and should, ideally, be accessible, comfortable, private, quiet and free from distractions. 13 However, while a central location, such as the participants' workplace or school, may encourage attendance, the venue may affect participants' behaviour. For example, in a school setting, pupils may behave like pupils, and in clinical settings, participants may be affected by any anxieties that affect them when they attend in a patient role.

Focus groups are usually recorded, often observed (by a researcher other than the moderator, whose role is to observe the interaction of the group to enhance analysis) and sometimes videotaped. At the start of a focus group, a moderator should acknowledge the presence of the audio recording equipment, assure participants of confidentiality and give people the opportunity to withdraw if they are uncomfortable with being taped. 14

A good quality multi-directional external microphone is recommended for the recording of focus groups, as internal microphones are rarely good enough to cope with the variation in volume of different speakers. 13 If observers are present, they should be introduced to participants as someone who is just there to observe, and sit away from the discussion. 14 Videotaping will require more than one camera to capture the whole group, as well as additional operational personnel in the room. This is, therefore, very obtrusive, which can affect the spontaneity of the group and in a focus group does not usually yield enough additional information that could not be captured by an observer to make videotaping worthwhile. 15

The systematic analysis of focus group transcripts is crucial. However, the transcription of focus groups is more complex and time consuming than in one-to-one interviews, and each hour of audio can take up to eight hours to transcribe and generate approximately 100 pages of text. Recordings should be transcribed verbatim and also speakers should be identified in a way that makes it possible to follow the contributions of each individual. Sometimes observational notes also need to be described in the transcripts in order for them to make sense.

The analysis of qualitative data is explored in the final paper of this series. However, it is important to note that the analysis of focus group data is different from other qualitative data because of their interactive nature, and this needs to be taken into consideration during analysis. The importance of the context of other speakers is essential to the understanding of individual contributions. 13 For example, in a group situation, participants will often challenge each other and justify their remarks because of the group setting, in a way that perhaps they would not in a one-to-one interview. The analysis of focus group data must therefore take account of the group dynamics that have generated remarks.

Focus groups in dental research

Focus groups are used increasingly in dental research, on a diverse range of topics, 16 illuminating a number of areas relating to patients, dental services and the dental profession. Addressing a special needs population difficult to access and sample through quantitative measures, Robinson et al . 17 used focus groups to investigate the oral health-related attitudes of drug users, exploring the priorities, understandings and barriers to care they encounter. Newton et al . 18 used focus groups to explore barriers to services among minority ethnic groups, highlighting for the first time differences between minority ethnic groups. Demonstrating the use of the method with professional groups as subjects in dental research, Gussy et al . 19 explored the barriers to and possible strategies for developing a shared approach in prevention of caries among pre-schoolers. This mixed method study was very important as the qualitative element was able to explain why the clinical trial failed, and this understanding may help researchers improve on the quantitative aspect of future studies, as well as making a valuable academic contribution in its own right.

Interviews and focus groups remain the most common methods of data collection in qualitative research, and are now being used with increasing frequency in dental research, particularly to access areas not amendable to quantitative methods and/or where depth, insight and understanding of particular phenomena are required. The examples of dental studies that have employed these methods also help to demonstrate the range of research contexts to which interview and focus group research can make a useful contribution. The continued employment of these methods can further strengthen many areas of dentally related work.

Silverman D . Doing qualitative research . London: Sage Publications, 2000.

Google Scholar

Britten N . Qualitative interviews in healthcare. In Pope C, Mays N (eds) Qualitative research in health care . 2nd ed. pp 11–19. London: BMJ Books, 1999.

Legard R, Keegan J, Ward K . In-depth interviews. In Ritchie J, Lewis J (eds) Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers . pp 139–169. London: Sage Publications, 2003.

May K M . Interview techniques in qualitative research: concerns and challenges. In Morse J M (ed) Qualitative nursing research . pp 187–201. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1991.

Stewart K, Gill P, Treasure E, Chadwick B . Understanding about food among 6-11 year olds in South Wales. Food Culture Society 2006; 9 : 317–333.

Article Google Scholar

Gibson B, Drenna J, Hanna S, Freeman R . An exploratory qualitative study examining the social and psychological processes involved in regular dental attendance. J Public Health Dent 2000; 60 : 5–11.

Kay E J, Blinkhorn A S . A qualitative investigation of factors governing dentists' treatment philosophies. Br Dent J 1996; 180 : 171–176.

Pontin D . Interviews. In Cormack D F S (ed) The research process in nursing . 4th ed. pp 289–298. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2000.

Kvale S . Interviews . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1996.

Hammersley M, Atkinson P . Ethnography: principles in practice . 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1995.

Kitzinger J . The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol Health Illn 1994; 16 : 103–121.

Morgan D L . The focus group guide book . London: Sage Publications, 1998.

Book Google Scholar

Bloor M, Frankland J, Thomas M, Robson K . Focus groups in social research . London: Sage Publications, 2001.

Stewart D W, Shamdasani P M . Focus groups. Theory and practice . London: Sage Publications, 1990.

Krueger R A . Moderating focus groups . London: Sage Publications, 1998.

Chestnutt I G, Robson K F. Focus groups – what are they? Dent Update 2002; 28 : 189–192.

Robinson P G, Acquah S, Gibson B . Drug users: oral health related attitudes and behaviours. Br Dent J 2005; 198 : 219–224.

Newton J T, Thorogood N, Bhavnani V, Pitt J, Gibbons D E, Gelbier S . Barriers to the use of dental services by individuals from minority ethnic communities living in the United Kingdom: findings from focus groups. Primary Dent Care 2001; 8 : 157–161.

Gussy M G, Waters E, Kilpatrick M . A qualitative study exploring barriers to a model of shared care for pre-school children's oral health. Br Dent J 2006; 201 : 165–170.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.