PSYC 210: Foundations of Psychology

- Tips for Searching for Articles

What is a literature review?

Conducting a literature review, organizing a literature review, writing a literature review, helpful book.

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Google Scholar

A literature review is a compilation of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches

Source: "What is a Literature Review?", Old Dominion University, https://guides.lib.odu.edu/c.php?g=966167&p=6980532

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by a central research question. It represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted, and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- Write down terms that are related to your question for they will be useful for searches later.

2. Decide on the scope of your review.

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment.

- Consider these things when planning your time for research.

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

- By Research Guide

4. Conduct your searches and find the literature.

- Review the abstracts carefully - this will save you time!

- Many databases will have a search history tab for you to return to for later.

- Use bibliographies and references of research studies to locate others.

- Use citation management software such as Zotero to keep track of your research citations.

5. Review the literature.

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question you are reviewing? What are the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze the literature review, samples and variables used, results, and conclusions. Does the research seem complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicted studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Are they experts or novices? Has the study been cited?

Source: "Literature Review", University of West Florida, https://libguides.uwf.edu/c.php?g=215113&p=5139469

A literature review is not a summary of the sources but a synthesis of the sources. It is made up of the topics the sources are discussing. Each section of the review is focused on a topic, and the relevant sources are discussed within the context of that topic.

1. Select the most relevant material from the sources

- Could be material that answers the question directly

- Extract as a direct quote or paraphrase

2. Arrange that material so you can focus on it apart from the source text itself

- You are now working with fewer words/passages

- Material is all in one place

3. Group similar points, themes, or topics together and label them

- The labels describe the points, themes, or topics that are the backbone of your paper’s structure

4. Order those points, themes, or topics as you will discuss them in the paper, and turn the labels into actual assertions

- A sentence that makes a point that is directly related to your research question or thesis

This is now the outline for your literature review.

Source: "Organizing a Review of the Literature – The Basics", George Mason University Writing Center, https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/research-based-writing/organizing-literature-reviews-the-basics

- Literature Review Matrix Here is a template on how people tend to organize their thoughts. The matrix template is a good way to write out the key parts of each article and take notes. Downloads as an XLSX file.

The most common way that literature reviews are organized is by theme or author. Find a general pattern of structure for the review. When organizing the review, consider the following:

- the methodology

- the quality of the findings or conclusions

- major strengths and weaknesses

- any other important information

Writing Tips:

- Be selective - Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. It should directly relate to the review's focus.

- Use quotes sparingly.

- Keep your own voice - Your voice (the writer's) should remain front and center. .

- Aim for one key figure/table per section to illustrate complex content, summarize a large body of relevant data, or describe the order of a process

- Legend below image/figure and above table and always refer to them in text

Source: "Composing your Literature Review", Florida A&M University, https://library.famu.edu/c.php?g=577356&p=3982811

- << Previous: Tips for Searching for Articles

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 3:43 PM

- URL: https://infoguides.pepperdine.edu/PSYC210

Explore. Discover. Create.

Copyright © 2022 Pepperdine University

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Request Info

- Search Search Site Faculty/Staff

- Open Navigation Menu Menu Close Navigation Menu

- Literature Review Guidelines

Making sense of what has been written on your topic.

Goals of a literature review:.

Before doing work in primary sources, historians must know what has been written on their topic. They must be familiar with theories and arguments–as well as facts–that appear in secondary sources.

Before you proceed with your research project, you too must be familiar with the literature: you do not want to waste time on theories that others have disproved and you want to take full advantage of what others have argued. You want to be able to discuss and analyze your topic.

Your literature review will demonstrate your familiarity with your topic’s secondary literature.

GUIDELINES FOR A LITERATURE REVIEW:

1) LENGTH: 8-10 pages of text for Senior Theses (485) (consult with your professor for other classes), with either footnotes or endnotes and with a works-consulted bibliography. [See also the citation guide on this site.]

2) NUMBER OF WORKS REVIEWED: Depends on the assignment, but for Senior Theses (485), at least ten is typical.

3) CHOOSING WORKS:

Your literature review must include enough works to provide evidence of both the breadth and the depth of the research on your topic or, at least, one important angle of it. The number of works necessary to do this will depend on your topic. For most topics, AT LEAST TEN works (mostly books but also significant scholarly articles) are necessary, although you will not necessarily give all of them equal treatment in your paper (e.g., some might appear in notes rather than the essay). 4) ORGANIZING/ARRANGING THE LITERATURE:

As you uncover the literature (i.e., secondary writing) on your topic, you should determine how the various pieces relate to each other. Your ability to do so will demonstrate your understanding of the evolution of literature.

You might determine that the literature makes sense when divided by time period, by methodology, by sources, by discipline, by thematic focus, by race, ethnicity, and/or gender of author, or by political ideology. This list is not exhaustive. You might also decide to subdivide categories based on other criteria. There is no “rule” on divisions—historians wrote the literature without consulting each other and without regard to the goal of fitting into a neat, obvious organization useful to students.

The key step is to FIGURE OUT the most logical, clarifying angle. Do not arbitrarily choose a categorization; use the one that the literature seems to fall into. How do you do that? For every source, you should note its thesis, date, author background, methodology, and sources. Does a pattern appear when you consider such information from each of your sources? If so, you have a possible thesis about the literature. If not, you might still have a thesis.

Consider: Are there missing elements in the literature? For example, no works published during a particular (usually fairly lengthy) time period? Or do studies appear after long neglect of a topic? Do interpretations change at some point? Does the major methodology being used change? Do interpretations vary based on sources used?

Follow these links for more help on analyzing historiography and historical perspective .

5) CONTENTS OF LITERATURE REVIEW:

The literature review is a research paper with three ingredients:

a) A brief discussion of the issue (the person, event, idea). [While this section should be brief, it needs to set up the thesis and literature that follow.] b) Your thesis about the literature c) A clear argument, using the works on topic as evidence, i.e., you discuss the sources in relation to your thesis, not as a separate topic.

These ingredients must be presented in an essay with an introduction, body, and conclusion.

6) ARGUING YOUR THESIS:

The thesis of a literature review should not only describe how the literature has evolved, but also provide a clear evaluation of that literature. You should assess the literature in terms of the quality of either individual works or categories of works. For instance, you might argue that a certain approach (e.g. social history, cultural history, or another) is better because it deals with a more complex view of the issue or because they use a wider array of source materials more effectively. You should also ensure that you integrate that evaluation throughout your argument. Doing so might include negative assessments of some works in order to reinforce your argument regarding the positive qualities of other works and approaches to the topic.

Within each group, you should provide essential information about each work: the author’s thesis, the work’s title and date, the author’s supporting arguments and major evidence.

In most cases, arranging the sources chronologically by publication date within each section makes the most sense because earlier works influenced later ones in one way or another. Reference to publication date also indicates that you are aware of this significant historiographical element.

As you discuss each work, DO NOT FORGET WHY YOU ARE DISCUSSING IT. YOU ARE PRESENTING AND SUPPORTING A THESIS ABOUT THE LITERATURE.

When discussing a particular work for the first time, you should refer to it by the author’s full name, the work’s title, and year of publication (either in parentheses after the title or worked into the sentence).

For example, “The field of slavery studies has recently been transformed by Ben Johnson’s The New Slave (2001)” and “Joe Doe argues in his 1997 study, Slavery in America, that . . . .”

Your paper should always note secondary sources’ relationship to each other, particularly in terms of your thesis about the literature (e.g., “Unlike Smith’s work, Mary Brown’s analysis reaches the conclusion that . . . .” and “Because of Anderson’s reliance on the president’s personal papers, his interpretation differs from Barry’s”). The various pieces of the literature are “related” to each other, so you need to indicate to the reader some of that relationship. (It helps the reader follow your thesis, and it convinces the reader that you know what you are talking about.)

7) DOCUMENTATION:

Each source you discuss in your paper must be documented using footnotes/endnotes and a bibliography. Providing author and title and date in the paper is not sufficient. Use correct Turabian/Chicago Manual of Style form. [See Bibliography and Footnotes/Endnotes pages.]

In addition, further supporting, but less significant, sources should be included in content foot or endnotes . (e.g., “For a similar argument to Ben Johnson’s, see John Terry, The Slave Who Was New (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), 3-45.”)

8 ) CONCLUSION OF LITERATURE REVIEW:

Your conclusion should not only reiterate your argument (thesis), but also discuss questions that remain unanswered by the literature. What has the literature accomplished? What has not been studied? What debates need to be settled?

Additional writing guidelines

History and American Studies

- About the Department

- Major Requirements & Courses

- What courses will I take as an History major?

- What can I do with my History degree?

- History 485

- Methodology

- Choosing a Topic

- Book Reviews

- Historiographic Clues

- Understanding Historical Perspective

- Sample Literature Review

- Using Quotations

- Ellipses and Brackets

- Footnotes and Endnotes

- Content Notes

- Citation Guide

- Citing Non-Print Resources

- How to Annotate

- Annotated Examples

- Journals vs. Magazines

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Historians Define Plagiarism

- Plagiarism Tutorial

- UMW Honor System

- Presentation Guidelines

- Tips for Leading Seminars

- Hints for Class Discussion

- Speaking Center

- Guidelines for a Research Paper

- Library Research Plan

- How to Use ILL

- Database Guide

- Guide to Online Research

- Writing Guidelines

- Recognizing Passive Voice

- Introduction and Conclusion

- MS Word’s Grammar and Spellcheck

- Writing Center

- What You Need to Know

- Links to Online Primary Sources by Region

- What will I learn from my American Studies major?

- What courses will I take as an American Studies major?

- What can I do with my American Studies degree?

- American Studies 485

- For Prospective Students

- Honors and Award Recipients

- Internships

Alumni Intros

How have History & American Studies majors built careers after earning their degrees? Learn more by clicking the image above.

Recent Posts

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 26, 2024

- Fall 2024 Courses

- Fall 2023 Symposium – 12/8 – All Welcome!

- Spring ’24 Course Flyers

- Internship Opportunity – Chesapeake Gateways Ambassador

- Congratulations to our Graduates!

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 21, 2023

- View umwhistory’s profile on Facebook

- View umwhistory’s profile on Twitter

Under recognized yet a clinically relevant impact of aneurysm location in Distal Anterior Cerebral Artery (DACA) aneurysms: insights from a contemporary surgical experience

- Published: 31 August 2024

- Volume 47 , article number 517 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Abhishek Halder 1 ,

- Kuntal Kanti Das 1 ,

- Soumen Kanjilal 1 ,

- Kamlesh Singh Bhaisora 1 ,

- Ashutosh Kumar 1 ,

- Pawan Kumar Verma 1 ,

- Ved Prakash Maurya 1 ,

- Anant Mehrotra 1 ,

- Arun Kumar Srivastava 1 &

- Awadhesh Kumar Jaiswal 1

Aneurysms of the distal anterior cerebral artery (DACA) are rare but surgically challenging. Despite a known therapeutic implication of the aneurysm location on the DACA territory, the literature is unclear about its clinical and prognostic significance. Our surgical experience over the last 5 years was reviewed to compare the clinical, operative, and outcome characteristics between aneurysms located below the mid portion of the genu of the corpus callosum (called proximal aneurysms) to those distal to this point (called distal aneurysms). A prognostic factor analysis was done using uni and multivariable analysis. A total of 34 patients were treated (M: F = 1:2.3). The distal group had a higher frequency of poor clinical grade at presentation ( n = 9, 47.4%) in contrast to ( n = 2, 13.3%) proximal aneurysms ( p = 0.039). Despite an overall tendency for a delayed functional improvement in these patients, the results were mainly due to favorable outcomes in the proximal group (favourable functional outcomes at discharge and at last follow-up being 80% and 86.7% respectively). On the multivariable analysis, only WFNS grade (> 2) at presentation (OR = 13.75; 95CI = 1.2–157.7) ( p = 0.035) and application of temporary clips (AOR = 34.32; 95CI = 2.59–454.1) ( p = 0.007), both of which were more in the distal group, independently predicted a poor long term functional outcome. Thus, the aneurysm location impacts the preoperative clinical grade, the intraoperative aneurysm rupture risk rate as well as the temporary clipping requirement. A combination of these factors leads to worse short and long-term functional outcomes in the distal DACA aneurysms.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at the institute were the study was conducted.

Carvi Y, Nievas MN (2010) The influence of configuration and location of ruptured distal cerebral anterior artery aneurysms on their treatment modality and results: analysis of our casuistry and literature review. Neurol Res 32:73–81. https://doi.org/10.1179/016164110X12556180205951

Article Google Scholar

Choque-Velasquez J, Hernesniemi J (2018) One burr-hole craniotomy: anterior interhemispheric approach in Helsinki neurosurgery. Surg Neurol Int 9:141. https://doi.org/10.4103/sni.sni_163_18

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Das KK, Singh S, Sharma P, Mehrotra A, Bhaisora K, Sardhara J, Srivastava AK, Jaiswal AK, Behari S, Kumar R (2017) Results of Proactive Surgical clipping in Poor-Grade Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Pattern of Recovery and predictors of Outcome. World Neurosurg 102:561–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.03.090

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ferch R, Pasqualin A, Pinna G, Chioffi F, Bricolo A (2002) Temporary arterial occlusion in the repair of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: an analysis of risk factors for stroke. J Neurosurg 97:836–842. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2002.97.4.0836

Furtado SV, Jayakumar D, Perikal PJ, Mohan D (2021) Contemporary Management of Distal Anterior cerebral artery aneurysms: a dual-trained neurosurgeon’s perspective. J Neurosci Rural Pract 12:711–717. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1735823

Griessenauer CJ, Poston TL, Shoja MM, Mortazavi MM, Falola M, Tubbs RS, Fisher WS (2014) The impact of Temporary artery occlusion during intracranial aneurysm surgery on long-term clinical outcome: part I. patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg 82:140–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.02.068

Kandregula S, Savardekar AR, Terrell D, Adeeb N, Whipple S, Beyl R, Birk HS, Newman WC, Kosty J, Cuellar H, Guthikonda B (2022) Microsurgical clipping and endovascular management of unruptured anterior circulation aneurysms: how age, frailty, and comorbidity indexes influence outcomes. J Neurosurg 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3171/2022.8.JNS22372

Kawashima M, Matsushima T, Sasaki T (2003) Surgical strategy for distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysms: microsurgical anatomy. J Neurosurg 99:517–525. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2003.99.3.0517

Kiyofuji S, Sora S, Graffeo CS, Perry A, Link MJ (2020) Anterior interhemispheric approach for clipping of subcallosal distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysms: case series and technical notes. Neurosurg Rev 43:801–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-019-01126-z

Lee J-Y, Kim M-K, Cho B-M, Park S-H, Oh S-M (2007) Surgical Experience of the ruptured distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysms. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 42:281. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2007.42.4.281

Lehecka M, Dashti R, Lehto H, Kivisaari R, Niemelä M, Hernesniemi J (2010) Distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysms. Surgical Management of Cerebrovascular Disease. Springer Vienna, Vienna, pp 15–26

Chapter Google Scholar

Metayer T, Gilard V, Piotin M, Emery E, Borha A, Robichon E, Briant AR, Derrey S, Vivien D, Gaberel T (2023) Microsurgery and Endovascular Therapy for Distal Anterior cerebral artery aneurysm: a Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. World Neurosurg 178:e174–e181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2023.07.022

Miyazawa N, Nukui H, Yagi S, Yamagata Z, Horikoshi T, Yagishita T, Sugita M (2000) Statistical analysis of factors affecting the outcome of patients with ruptured distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 142:1241–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007010070020

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Petr O, Coufalová L, Bradáč O, Rehwald R, Glodny B, Beneš V (2017) Safety and Efficacy of Surgical and Endovascular Treatment for Distal Anterior cerebral artery aneurysms: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 100:557–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.11.134

Proust F, Toussaint P, Hannequin D, Rabenenoïna C, Le Gars D, Fréger P (1997) Outcome in 43 patients with distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke 28:2405–2409. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.28.12.2405

Rao BM (2016) Surgery for distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysm. Neurol India 64:1145. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.193762

Sharma GR, Karki P, Joshi S, Paudel P, Shah DB, Baburam P, Bidhan G (2023) Factors affecting the Outcome after Surgical clipping of ruptured distal anterior cerebral artery (DACA) aneurysms. Asian J Neurosurg 18:557–566. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1771371

Yoshikawa MH, Rabelo NN, Telles JPM, Pipek LZ, Barbosa GB, Barbato NC, Coelho ACSDS, Teixeira MJ, Figueiredo EG (2023) Role of temporary arterial occlusion in subarachnoid hemorrhage outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Acta Cirúrgica Bras 38:e387923. https://doi.org/10.1590/acb387923

Download references

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurosurgery, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, UP 226014, India

Abhishek Halder, Kuntal Kanti Das, Soumen Kanjilal, Kamlesh Singh Bhaisora, Ashutosh Kumar, Pawan Kumar Verma, Ved Prakash Maurya, Anant Mehrotra, Arun Kumar Srivastava & Awadhesh Kumar Jaiswal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization - AH, KKD, SK; Methodology - AH, KKD, SK, KSB; Formal analysis and investigation - AH, KKD, SK and AK; Writing – original draft - AH, KKD, SK and AM; Writing - review & editing - AH, KKD, SK, KSB, PKV and AKS; Resources - AH, KKD, SK, VPM and PKV; Supervision - KKD, AM, AKS and AKJ;

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kuntal Kanti Das .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

This is an observational study. The Institutional Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

As this a retrospective study, the patients’ consent to participate were waived off by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

The manuscript does not contain any information from which a patient’s identity could be disclosed.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Halder, A., Das, K.K., Kanjilal, S. et al. Under recognized yet a clinically relevant impact of aneurysm location in Distal Anterior Cerebral Artery (DACA) aneurysms: insights from a contemporary surgical experience. Neurosurg Rev 47 , 517 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-02759-5

Download citation

Received : 07 March 2024

Revised : 28 June 2024

Accepted : 23 August 2024

Published : 31 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-02759-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Corpus callosum

- Surgical approach

- Sub callosal

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Study Protocol

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2024

Learning effect of online versus onsite education in health and medical scholarship – protocol for a cluster randomized trial

- Rie Raffing 1 ,

- Lars Konge 2 &

- Hanne Tønnesen 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 927 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

123 Accesses

Metrics details

The disruption of health and medical education by the COVID-19 pandemic made educators question the effect of online setting on students’ learning, motivation, self-efficacy and preference. In light of the health care staff shortage online scalable education seemed relevant. Reviews on the effect of online medical education called for high quality RCTs, which are increasingly relevant with rapid technological development and widespread adaption of online learning in universities. The objective of this trial is to compare standardized and feasible outcomes of an online and an onsite setting of a research course regarding the efficacy for PhD students within health and medical sciences: Primarily on learning of research methodology and secondly on preference, motivation, self-efficacy on short term and academic achievements on long term. Based on the authors experience with conducting courses during the pandemic, the hypothesis is that student preferred onsite setting is different to online setting.

Cluster randomized trial with two parallel groups. Two PhD research training courses at the University of Copenhagen are randomized to online (Zoom) or onsite (The Parker Institute, Denmark) setting. Enrolled students are invited to participate in the study. Primary outcome is short term learning. Secondary outcomes are short term preference, motivation, self-efficacy, and long-term academic achievements. Standardized, reproducible and feasible outcomes will be measured by tailor made multiple choice questionnaires, evaluation survey, frequently used Intrinsic Motivation Inventory, Single Item Self-Efficacy Question, and Google Scholar publication data. Sample size is calculated to 20 clusters and courses are randomized by a computer random number generator. Statistical analyses will be performed blinded by an external statistical expert.

Primary outcome and secondary significant outcomes will be compared and contrasted with relevant literature. Limitations include geographical setting; bias include lack of blinding and strengths are robust assessment methods in a well-established conceptual framework. Generalizability to PhD education in other disciplines is high. Results of this study will both have implications for students and educators involved in research training courses in health and medical education and for the patients who ultimately benefits from this training.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05736627. SPIRIT guidelines are followed.

Peer Review reports

Medical education was utterly disrupted for two years by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the midst of rearranging courses and adapting to online platforms we, with lecturers and course managers around the globe, wondered what the conversion to online setting did to students’ learning, motivation and self-efficacy [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. What the long-term consequences would be [ 4 ] and if scalable online medical education should play a greater role in the future [ 5 ] seemed relevant and appealing questions in a time when health care professionals are in demand. Our experience of performing research training during the pandemic was that although PhD students were grateful for courses being available, they found it difficult to concentrate related to the long screen hours. We sensed that most students preferred an onsite setting and perceived online courses a temporary and inferior necessity. The question is if this impacted their learning?

Since the common use of the internet in medical education, systematic reviews have sought to answer if there is a difference in learning effect when taught online compared to onsite. Although authors conclude that online learning may be equivalent to onsite in effect, they agree that studies are heterogeneous and small [ 6 , 7 ], with low quality of the evidence [ 8 , 9 ]. They therefore call for more robust and adequately powered high-quality RCTs to confirm their findings and suggest that students’ preferences in online learning should be investigated [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

This uncovers two knowledge gaps: I) High-quality RCTs on online versus onsite learning in health and medical education and II) Studies on students’ preferences in online learning.

Recently solid RCTs have been performed on the topic of web-based theoretical learning of research methods among health professionals [ 10 , 11 ]. However, these studies are on asynchronous courses among medical or master students with short term outcomes.

This uncovers three additional knowledge gaps: III) Studies on synchronous online learning IV) among PhD students of health and medical education V) with long term measurement of outcomes.

The rapid technological development including artificial intelligence (AI) and widespread adaption as well as application of online learning forced by the pandemic, has made online learning well-established. It represents high resolution live synchronic settings which is available on a variety of platforms with integrated AI and options for interaction with and among students, chat and break out rooms, and exterior digital tools for teachers [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Thus, investigating online learning today may be quite different than before the pandemic. On one hand, it could seem plausible that this technological development would make a difference in favour of online learning which could not be found in previous reviews of the evidence. On the other hand, the personal face-to-face interaction during onsite learning may still be more beneficial for the learning process and combined with our experience of students finding it difficult to concentrate when online during the pandemic we hypothesize that outcomes of the onsite setting are different from the online setting.

To support a robust study, we design it as a cluster randomized trial. Moreover, we use the well-established and widely used Kirkpatrick’s conceptual framework for evaluating learning as a lens to assess our outcomes [ 15 ]. Thus, to fill the above-mentioned knowledge gaps, the objective of this trial is to compare a synchronous online and an in-person onsite setting of a research course regarding the efficacy for PhD students within the health and medical sciences:

Primarily on theoretical learning of research methodology and

Secondly on

◦ Preference, motivation, self-efficacy on short term

◦ Academic achievements on long term

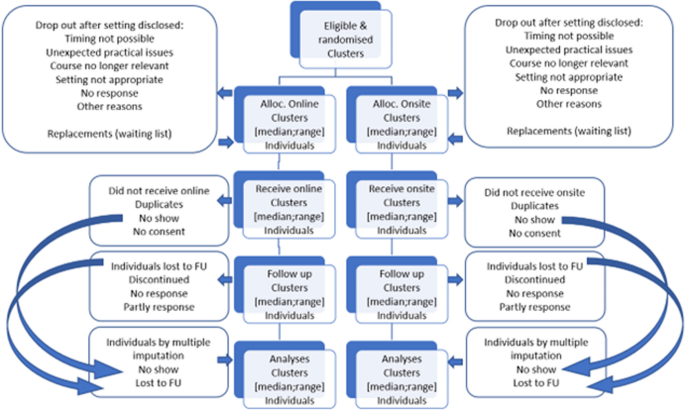

Trial design

This study protocol covers synchronous online and in-person onsite setting of research courses testing the efficacy for PhD students. It is a two parallel arms cluster randomized trial (Fig. 1 ).

Consort flow diagram

The study measures baseline and post intervention. Baseline variables and knowledge scores are obtained at the first day of the course, post intervention measurement is obtained the last day of the course (short term) and monthly for 24 months (long term).

Randomization is stratified giving 1:1 allocation ratio of the courses. As the number of participants within each course might differ, the allocation ratio of participants in the study will not fully be equal and 1:1 balanced.

Study setting

The study site is The Parker Institute at Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. From here the courses are organized and run online and onsite. The course programs and time schedules, the learning objective, the course management, the lecturers, and the delivery are identical in the two settings. The teachers use the same introductory presentations followed by training in break out groups, feed-back and discussions. For the online group, the setting is organized as meetings in the online collaboration tool Zoom® [ 16 ] using the basic available technicalities such as screen sharing, chat function for comments, and breakout rooms and other basics digital tools if preferred. The online version of the course is synchronous with live education and interaction. For the onsite group, the setting is the physical classroom at the learning facilities at the Parker Institute. Coffee and tea as well as simple sandwiches and bottles of water, which facilitate sociality, are available at the onsite setting. The participants in the online setting must get their food and drink by themselves, but online sociality is made possible by not closing down the online room during the breaks. The research methodology courses included in the study are “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research”, (see course programme in appendix 1) and “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” [ 17 ] (see course programme in appendix 2). The two courses both have 12 seats and last either three or three and a half days resulting in 2.2 and 2.6 ECTS credits, respectively. They are offered by the PhD School of the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. Both courses are available and covered by the annual tuition fee for all PhD students enrolled at a Danish university.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for participants: All PhD students enrolled on the PhD courses participate after informed consent: “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” at the PhD School of the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Exclusion criteria for participants: Declining to participate and withdrawal of informed consent.

Informed consent

The PhD students at the PhD School at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen participate after informed consent, taken by the daily project leader, allowing evaluation data from the course to be used after pseudo-anonymization in the project. They are informed in a welcome letter approximately three weeks prior to the course and again in the introduction the first course day. They register their consent on the first course day (Appendix 3). Declining to participate in the project does not influence their participation in the course.

Interventions

Online course settings will be compared to onsite course settings. We test if the onsite setting is different to online. Online learning is increasing but onsite learning is still the preferred educational setting in a medical context. In this case onsite learning represents “usual care”. The online course setting is meetings in Zoom using the technicalities available such as chat and breakout rooms. The onsite setting is the learning facilities, at the Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, The Capital Region, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The course settings are not expected to harm the participants, but should a request be made to discontinue the course or change setting this will be met, and the participant taken out of the study. Course participants are allowed to take part in relevant concomitant courses or other interventions during the trial.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

Course participants are motivated to complete the course irrespectively of the setting because it bears ECTS-points for their PhD education and adds to the mandatory number of ECTS-points. Thus, we expect adherence to be the same in both groups. However, we monitor their presence in the course and allocate time during class for testing the short-term outcomes ( motivation, self-efficacy, preference and learning). We encourage and, if necessary, repeatedly remind them to register with Google Scholar for our testing of the long-term outcome (academic achievement).

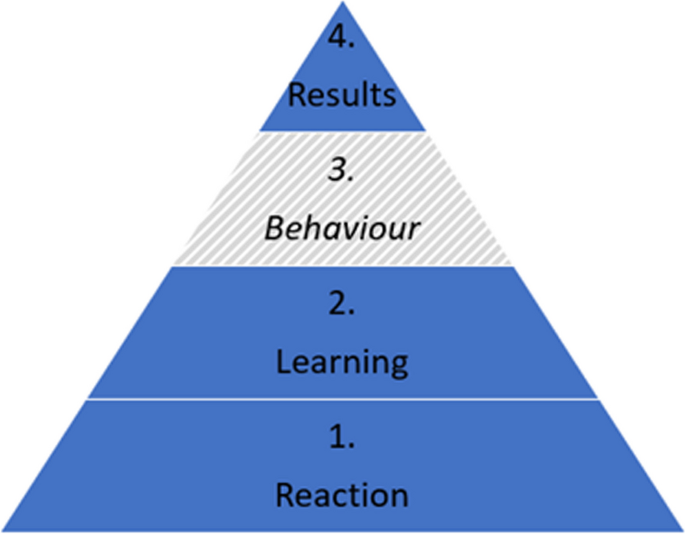

Outcomes are related to the Kirkpatrick model for evaluating learning (Fig. 2 ) which divides outcomes into four different levels; Reaction which includes for example motivation, self-efficacy and preferences, Learning which includes knowledge acquisition, Behaviour for practical application of skills when back at the job (not included in our outcomes), and Results for impact for end-users which includes for example academic achievements in the form of scientific articles [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

The Kirkpatrick model

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is short term learning (Kirkpatrick level 2).

Learning is assessed by a Multiple-Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) developed prior to the RCT specifically for this setting (Appendix 4). First the lecturers of the two courses were contacted and asked to provide five multiple choice questions presented as a stem with three answer options; one correct answer and two distractors. The questions should be related to core elements of their teaching under the heading of research training. The questions were set up to test the cognition of the students at the levels of "Knows" or "Knows how" according to Miller's Pyramid of Competence and not their behaviour [ 21 ]. Six of the course lecturers responded and out of this material all the questions which covered curriculum of both courses were selected. It was tested on 10 PhD students and within the lecturer group, revised after an item analysis and English language revised. The MCQ ended up containing 25 questions. The MCQ is filled in at baseline and repeated at the end of the course. The primary outcomes based on the MCQ is estimated as the score of learning calculated as number of correct answers out of 25 after the course. A decrease of points of the MCQ in the intervention groups denotes a deterioration of learning. In the MCQ the minimum score is 0 and 25 is maximum, where 19 indicates passing the course.

Furthermore, as secondary outcome, this outcome measurement will be categorized as binary outcome to determine passed/failed of the course defined by 75% (19/25) correct answers.

The learning score will be computed on group and individual level and compared regarding continued outcomes by the Mann–Whitney test comparing the learning score of the online and onsite groups. Regarding the binomial outcome of learning (passed/failed) data will be analysed by the Fisher’s exact test on an intention-to-treat basis between the online and onsite. The results will be presented as median and range and as mean and standard deviations, for possible future use in meta-analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Motivation assessment post course: Motivation level is measured by the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) Scale [ 22 ] (Appendix 5). The IMI items were randomized by random.org on the 4th of August 2022. It contains 12 items to be assessed by the students on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 is “Not at all true”, 4 is “Somewhat true” and 7 is “Very true”. The motivation score will be computed on group and individual level and will then be tested by the Mann–Whitney of the online and onsite group.

Self-efficacy assessment post course: Self-efficacy level is measured by a single-item measure developed and validated by Williams and Smith [ 23 ] (Appendix 6). It is assessed by the students on a scale from 1–10 where 1 is “Strongly disagree” and 10 is “Strongly agree”. The self-efficacy score will be computed on group and individual level and tested by a Mann–Whitney test to compare the self-efficacy score of the online and onsite group.

Preference assessment post course: Preference is measured as part of the general course satisfaction evaluation with the question “If you had the option to choose, which form would you prefer this course to have?” with the options “onsite form” and “online form”.

Academic achievement assessment is based on 24 monthly measurements post course of number of publications, number of citations, h-index, i10-index. This data is collected through the Google Scholar Profiles [ 24 ] of the students as this database covers most scientific journals. Associations between onsite/online and long-term academic will be examined with Kaplan Meyer and log rank test with a significance level of 0.05.

Participant timeline

Enrolment for the course at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, becomes available when it is published in the course catalogue. In the course description the course location is “To be announced”. Approximately 3–4 weeks before the course begins, the participant list is finalized, and students receive a welcome letter containing course details, including their allocation to either the online or onsite setting. On the first day of the course, oral information is provided, and participants provide informed consent, baseline variables, and base line knowledge scores.

The last day of scheduled activities the following scores are collected, knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy, setting preference, and academic achievement. To track students' long term academic achievements, follow-ups are conducted monthly for a period of 24 months, with assessments occurring within one week of the last course day (Table 1 ).

Sample size

The power calculation is based on the main outcome, theoretical learning on short term. For the sample size determination, we considered 12 available seats for participants in each course. To achieve statistical power, we aimed for 8 clusters in both online and onsite arms (in total 16 clusters) to detect an increase in learning outcome of 20% (learning outcome increase of 5 points). We considered an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.02, a standard deviation of 10, a power of 80%, and a two-sided alpha level of 5%. The Allocation Ratio was set at 1, implying an equal number of subjects in both online and onsite group.

Considering a dropout up to 2 students per course, equivalent to 17%, we determined that a total of 112 participants would be needed. This calculation factored in 10 clusters of 12 participants per study arm, which we deemed sufficient to assess any changes in learning outcome.

The sample size was estimated using the function n4means from the R package CRTSize [ 25 ].

Recruitment

Participants are PhD students enrolled in 10 courses of “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and 10 courses of “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” at the PhD School of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Assignment of interventions: allocation

Randomization will be performed on course-level. The courses are randomized by a computer random number generator [ 26 ]. To get a balanced randomization per year, 2 sets with 2 unique random integers in each, taken from the 1–4 range is requested.

The setting is not included in the course catalogue of the PhD School and thus allocation to online or onsite is concealed until 3–4 weeks before course commencement when a welcome letter with course information including allocation to online or onsite setting is distributed to the students. The lecturers are also informed of the course setting at this time point. If students withdraw from the course after being informed of the setting, a letter is sent to them enquiring of the reason for withdrawal and reason is recorded (Appendix 7).

The allocation sequence is generated by a computer random number generator (random.org). The participants and the lecturers sign up for the course without knowing the course setting (online or onsite) until 3–4 weeks before the course.

Assignment of interventions: blinding

Due to the nature of the study, it is not possible to blind trial participants or lecturers. The outcomes are reported by the participants directly in an online form, thus being blinded for the outcome assessor, but not for the individual participant. The data collection for the long-term follow-up regarding academic achievements is conducted without blinding. However, the external researcher analysing the data will be blinded.

Data collection and management

Data will be collected by the project leader (Table 1 ). Baseline variables and post course knowledge, motivation, and self-efficacy are self-reported through questionnaires in SurveyXact® [ 27 ]. Academic achievements are collected through Google Scholar profiles of the participants.

Given that we are using participant assessments and evaluations for research purposes, all data collection – except for monthly follow-up of academic achievements after the course – takes place either in the immediate beginning or ending of the course and therefore we expect participant retention to be high.

Data will be downloaded from SurveyXact and stored in a locked and logged drive on a computer belonging to the Capital Region of Denmark. Only the project leader has access to the data.

This project conduct is following the Danish Data Protection Agency guidelines of the European GDPR throughout the trial. Following the end of the trial, data will be stored at the Danish National Data Archive which fulfil Danish and European guidelines for data protection and management.

Statistical methods

Data is anonymized and blinded before the analyses. Analyses are performed by a researcher not otherwise involved in the inclusion or randomization, data collection or handling. All statistical tests will be testing the null hypotheses assuming the two arms of the trial being equal based on corresponding estimates. Analysis of primary outcome on short-term learning will be started once all data has been collected for all individuals in the last included course. Analyses of long-term academic achievement will be started at end of follow-up.

Baseline characteristics including both course- and individual level information will be presented. Table 2 presents the available data on baseline.

We will use multivariate analysis for identification of the most important predictors (motivation, self-efficacy, sex, educational background, and knowledge) for best effect on short and long term. The results will be presented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The results will be considered significant if CI does not include the value one.

All data processing and analyses were conducted using R statistical software version 4.1.0, 2021–05-18 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

If possible, all analysis will be performed for “Practical Course in Systematic Review Technique in Clinical Research” and for “Getting started: Writing your first manuscript for publication” separately.

Primary analyses will be handled with the intention-to-treat approach. The analyses will include all individuals with valid data regardless of they did attend the complete course. Missing data will be handled with multiple imputation [ 28 ] .

Upon reasonable request, public assess will be granted to protocol, datasets analysed during the current study, and statistical code Table 3 .

Oversight, monitoring, and adverse events

This project is coordinated in collaboration between the WHO CC (DEN-62) at the Parker Institute, CAMES, and the PhD School at the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. The project leader runs the day-to-day support of the trial. The steering committee of the trial includes principal investigators from WHO CC (DEN-62) and CAMES and the project leader and meets approximately three times a year.

Data monitoring is done on a daily basis by the project leader and controlled by an external independent researcher.

An adverse event is “a harmful and negative outcome that happens when a patient has been provided with medical care” [ 29 ]. Since this trial does not involve patients in medical care, we do not expect adverse events. If participants decline taking part in the course after receiving the information of the course setting, information on reason for declining is sought obtained. If the reason is the setting this can be considered an unintended effect. Information of unintended effects of the online setting (the intervention) will be recorded. Participants are encouraged to contact the project leader with any response to the course in general both during and after the course.

The trial description has been sent to the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (VEK) (21041907), which assessed it as not necessary to notify and that it could proceed without permission from VEK according to the Danish law and regulation of scientific research. The trial is registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (Privacy) (P-2022–158). Important protocol modification will be communicated to relevant parties as well as VEK, the Joint Regional Information Security and Clinicaltrials.gov within an as short timeframe as possible.

Dissemination plans

The results (positive, negative, or inconclusive) will be disseminated in educational, scientific, and clinical fora, in international scientific peer-reviewed journals, and clinicaltrials.gov will be updated upon completion of the trial. After scientific publication, the results will be disseminated to the public by the press, social media including the website of the hospital and other organizations – as well as internationally via WHO CC (DEN-62) at the Parker Institute and WHO Europe.

All authors will fulfil the ICMJE recommendations for authorship, and RR will be first author of the articles as a part of her PhD dissertation. Contributors who do not fulfil these recommendations will be offered acknowledgement in the article.

This cluster randomized trial investigates if an onsite setting of a research course for PhD students within the health and medical sciences is different from an online setting. The outcomes measured are learning of research methodology (primary), preference, motivation, and self-efficacy (secondary) on short term and academic achievements (secondary) on long term.

The results of this study will be discussed as follows:

Discussion of primary outcome

Primary outcome will be compared and contrasted with similar studies including recent RCTs and mixed-method studies on online and onsite research methodology courses within health and medical education [ 10 , 11 , 30 ] and for inspiration outside the field [ 31 , 32 ]: Tokalic finds similar outcomes for online and onsite, Martinic finds that the web-based educational intervention improves knowledge, Cheung concludes that the evidence is insufficient to say that the two modes have different learning outcomes, Kofoed finds online setting to have negative impact on learning and Rahimi-Ardabili presents positive self-reported student knowledge. These conflicting results will be discussed in the context of the result on the learning outcome of this study. The literature may change if more relevant studies are published.

Discussion of secondary outcomes

Secondary significant outcomes are compared and contrasted with similar studies.

Limitations, generalizability, bias and strengths

It is a limitation to this study, that an onsite curriculum for a full day is delivered identically online, as this may favour the onsite course due to screen fatigue [ 33 ]. At the same time, it is also a strength that the time schedules are similar in both settings. The offer of coffee, tea, water, and a plain sandwich in the onsite course may better facilitate the possibility for socializing. Another limitation is that the study is performed in Denmark within a specific educational culture, with institutional policies and resources which might affect the outcome and limit generalization to other geographical settings. However, international students are welcome in the class.

In educational interventions it is generally difficult to blind participants and this inherent limitation also applies to this trial [ 11 ]. Thus, the participants are not blinded to their assigned intervention, and neither are the lecturers in the courses. However, the external statistical expert will be blinded when doing the analyses.

We chose to compare in-person onsite setting with a synchronous online setting. Therefore, the online setting cannot be expected to generalize to asynchronous online setting. Asynchronous delivery has in some cases showed positive results and it might be because students could go back and forth through the modules in the interface without time limit [ 11 ].

We will report on all the outcomes defined prior to conducting the study to avoid selective reporting bias.

It is a strength of the study that it seeks to report outcomes within the 1, 2 and 4 levels of the Kirkpatrick conceptual framework, and not solely on level 1. It is also a strength that the study is cluster randomized which will reduce “infections” between the two settings and has an adequate power calculated sample size and looks for a relevant educational difference of 20% between the online and onsite setting.

Perspectives with implications for practice

The results of this study may have implications for the students for which educational setting they choose. Learning and preference results has implications for lecturers, course managers and curriculum developers which setting they should plan for the health and medical education. It may also be of inspiration for teaching and training in other disciplines. From a societal perspective it also has implications because we will know the effect and preferences of online learning in case of a future lock down.

Future research could investigate academic achievements in online and onsite research training on the long run (Kirkpatrick 4); the effect of blended learning versus online or onsite (Kirkpatrick 2); lecturers’ preferences for online and onsite setting within health and medical education (Kirkpatrick 1) and resource use in synchronous and asynchronous online learning (Kirkpatrick 5).

Trial status

This trial collected pilot data from August to September 2021 and opened for inclusion in January 2022. Completion of recruitment is expected in April 2024 and long-term follow-up in April 2026. Protocol version number 1 03.06.2022 with amendments 30.11.2023.

Availability of data and materials

The project leader will have access to the final trial dataset which will be available upon reasonable request. Exception to this is the qualitative raw data that might contain information leading to personal identification.

Abbreviations

Artificial Intelligence

Copenhagen academy for medical education and simulation

Confidence interval

Coronavirus disease

European credit transfer and accumulation system

International committee of medical journal editors

Intrinsic motivation inventory

Multiple choice questionnaire

Doctor of medicine

Masters of sciences

Randomized controlled trial

Scientific ethical committee of the Capital Region of Denmark

WHO Collaborating centre for evidence-based clinical health promotion

Samara M, Algdah A, Nassar Y, Zahra SA, Halim M, Barsom RMM. How did online learning impact the academic. J Technol Sci Educ. 2023;13(3):869–85.

Article Google Scholar

Nejadghaderi SA, Khoshgoftar Z, Fazlollahi A, Nasiri MJ. Medical education during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: an umbrella review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1358084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1358084 .

Madi M, Hamzeh H, Abujaber S, Nawasreh ZH. Have we failed them? Online learning self-efficacy of physiotherapy students during COVID-19 pandemic. Physiother Res Int. 2023;5:e1992. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1992 .

Torda A. How COVID-19 has pushed us into a medical education revolution. Intern Med J. 2020;50(9):1150–3.

Alhat S. Virtual Classroom: A Future of Education Post-COVID-19. Shanlax Int J Educ. 2020;8(4):101–4.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1181–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.10.1181 .

Pei L, Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666538. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1666538 .

Richmond H, Copsey B, Hall AM, Davies D, Lamb SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of online versus alternative methods for training licensed health care professionals to deliver clinical interventions. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1047-4 .

George PP, Zhabenko O, Kyaw BM, Antoniou P, Posadzki P, Saxena N, Semwal M, Tudor Car L, Zary N, Lockwood C, Car J. Online Digital Education for Postregistration Training of Medical Doctors: Systematic Review by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e13269. https://doi.org/10.2196/13269 .

Tokalić R, Poklepović Peričić T, Marušić A. Similar Outcomes of Web-Based and Face-to-Face Training of the GRADE Approach for the Certainty of Evidence: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e43928. https://doi.org/10.2196/43928 .

Krnic Martinic M, Čivljak M, Marušić A, Sapunar D, Poklepović Peričić T, Buljan I, et al. Web-Based Educational Intervention to Improve Knowledge of Systematic Reviews Among Health Science Professionals: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(8): e37000.

https://www.mentimeter.com/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

https://www.sendsteps.com/en/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

https://da.padlet.com/ . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Zackoff MW, Real FJ, Abramson EL, Li STT, Klein MD, Gusic ME. Enhancing Educational Scholarship Through Conceptual Frameworks: A Challenge and Roadmap for Medical Educators. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):135–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.003 .

https://zoom.us/ . Accessed 20 Aug 2024.

Raffing R, Larsen S, Konge L, Tønnesen H. From Targeted Needs Assessment to Course Ready for Implementation-A Model for Curriculum Development and the Course Results. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032529 .

https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/the-kirkpatrick-model/ . Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

Smidt A, Balandin S, Sigafoos J, Reed VA. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(3):266–74.

Campbell K, Taylor V, Douglas S. Effectiveness of online cancer education for nurses and allied health professionals; a systematic review using kirkpatrick evaluation framework. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(2):339–56.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–7.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68 .

Williams GM, Smith AP. Using single-item measures to examine the relationships between work, personality, and well-being in the workplace. Psychology. 2016;07(06):753–67.

https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/citations.html . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Rotondi MA. CRTSize: sample size estimation functions for cluster randomized trials. R package version 1.0. 2015. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=CRTSize .

Random.org. Available from: https://www.random.org/

https://rambollxact.dk/surveyxact . Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ (Online). 2009;339:157–60.

Google Scholar

Skelly C, Cassagnol M, Munakomi S. Adverse Events. StatPearls Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558963/ .

Rahimi-Ardabili H, Spooner C, Harris MF, Magin P, Tam CWM, Liaw ST, et al. Online training in evidence-based medicine and research methods for GP registrars: a mixed-methods evaluation of engagement and impact. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8439372/pdf/12909_2021_Article_2916.pdf .

Cheung YYH, Lam KF, Zhang H, Kwan CW, Wat KP, Zhang Z, et al. A randomized controlled experiment for comparing face-to-face and online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Educ. 2023;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1160430 .

Kofoed M, Gebhart L, Gilmore D, Moschitto R. Zooming to Class?: Experimental Evidence on College Students' Online Learning During Covid-19. SSRN Electron J. 2021;IZA Discussion Paper No. 14356.

Mutlu Aİ, Yüksel M. Listening effort, fatigue, and streamed voice quality during online university courses. Logop Phoniatr Vocol :1–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14015439.2024.2317789

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the students who make their evaluations available for this trial and MSc (Public Health) Mie Sylow Liljendahl for statistical support.

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University The Parker Institute, which hosts the WHO CC (DEN-62), receives a core grant from the Oak Foundation (OCAY-18–774-OFIL). The Oak Foundation had no role in the design of the study or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

WHO Collaborating Centre (DEN-62), Clinical Health Promotion Centre, The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg & Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, 2400, Denmark

Rie Raffing & Hanne Tønnesen

Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation (CAMES), Centre for HR and Education, The Capital Region of Denmark, Copenhagen, 2100, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RR, LK and HT have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; RR to the acquisition of data, and RR, LK and HT to the interpretation of data; RR has drafted the work and RR, LK, and HT have substantively revised it AND approved the submitted version AND agreed to be personally accountable for their own contributions as well as ensuring that any questions which relates to the accuracy or integrity of the work are adequately investigated, resolved and documented.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rie Raffing .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics has assessed the study Journal-nr.:21041907 (Date: 21–09-2021) without objections or comments. The study has been approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency Journal-nr.: P-2022–158 (Date: 04.05.2022).

All PhD students participate after informed consent. They can withdraw from the study at any time without explanations or consequences for their education. They will be offered information of the results at study completion. There are no risks for the course participants as the measurements in the course follow routine procedure and they are not affected by the follow up in Google Scholar. However, the 15 min of filling in the forms may be considered inconvenient.

The project will follow the GDPR and the Joint Regional Information Security Policy. Names and ID numbers are stored on a secure and logged server at the Capital Region Denmark to avoid risk of data leak. All outcomes are part of the routine evaluation at the courses, except the follow up for academic achievement by publications and related indexes. However, the publications are publicly available per se.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., supplementary material 2., supplementary material 3., supplementary material 4., supplementary material 5., supplementary material 6., supplementary material 7., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Raffing, R., Konge, L. & Tønnesen, H. Learning effect of online versus onsite education in health and medical scholarship – protocol for a cluster randomized trial. BMC Med Educ 24 , 927 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05915-z

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2024

Accepted : 14 August 2024

Published : 26 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05915-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-efficacy

- Achievements

- Health and Medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2024

Concordant fatal congenital anomaly in twin pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature

- Amenu Diriba 1 ,

- Temesgen Tilahun ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4138-4066 1 ,

- Lammii Gonfaa 1 ,

- Jemal Gebi 1 ,

- Bikila Lemi 1 ,

- Jiregna Fyera 1 ,

- Suleiman Mazeng 1 ,

- Aschalew Legesse 1 &

- Dinaol Alemu 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 18 , Article number: 406 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

When a pregnant mother finds out she has a fetus with a congenital defect, the parents feel profound worry, anxiety, and melancholy. Anomalies can happen in singleton or twin pregnancies, though they are more common in twin pregnancies. In twins, several congenital defects are typically discordant.

Case summary

We present a rare case of concordant fatal anomaly in twin pregnancy in a 22-year-old African patient primigravida mother from Western Ethiopia who presented for routine antenatal care. An obstetric ultrasound scan showed anencephaly, meningomyelocele, and severe ventriculomegaly. After receiving the counseling, the patient was admitted to the ward, and the pregnancy was terminated with the medical option. Following a successful in-patient stay, she was given folic acid supplements and instructed to get preconception counseling before getting pregnant again.

The case demonstrates the importance of early obstetric ultrasound examination and detailed anatomic scanning, in twin pregnancies in particular. This case also calls for routine preconceptional care.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

A “congenital anomaly” is defined as any abnormal deviation from the expected structure, form, or function. “Malformations” are morphological abnormalities of organs or regions of the body resulting from an intrinsically abnormal developmental process, whereas “disruptions” are defects from interference with an initially normal developmental process [ 1 , 2 ].

Congenital anomalies present in twins also include any anomaly that may occur in singletons, including primary structural malformations, chromosomal defects, and genetic syndromes [ 1 , 2 ]. The anomalies may involve one or both twins [ 2 , 3 ]. The former is called discordant, while the latter is termed concordant [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Due to the anomaly’s multifactorial inheritance pattern, which is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, twins are usually discordant for this anomaly, with only one co-twin affected [ 1 , 3 ].

However, some research has shown that identical twins have concordant anomalies such as neural tube defects [ 3 , 4 ]. Here we present a rare case of concordant congenital anomaly in twin pregnancy.

Case presentation

This 22-year-old African patient primigravida from western Ethiopia came to Wallaga University Referral Hospital for her second appointment as part of her routine prenatal care schedule. She said she had been amenorrheic for the past 4 months, but she could not recall the last time she had had a regular menstrual cycle. She received folic acid 5 mg (orally daily and iron sulphate 325 mg orally three times daily for 3 months, and two doses of tetanus–diphtheria vaccine during her prenatal care. However, she had no preconceptional care.

In the course of the index pregnancy, she had never experienced headaches, vaginal bleeding, blurred vision, or epigastric pain. In addition, she had no history of smoking tobacco, chewing khat, drinking alcohol, or using other forms of medication. She had never had bronchial asthma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or heart disease.

There was no history of twin pregnancies in her family. This patient was diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum and hospitalized to the gynecology ward a month prior to the current presentation. She was released from the hospital after 2 days, having improved. It proved that the pregnancy was twins at 11 weeks appropriate for gestational age (AGA). However, no fetal anomaly was detected.

On examination, she was healthy-looking. Her vital signs were blood pressure (BP) = 120/70 mmHg, pulse rate (PR) = 84 beats per minute, respiratory rate (RR) = 20 breaths per minute, and a temperature of 37.6 °C. She had slightly pale conjunctiva. An abdominal exam showed a 20-week-sized gravid uterus. The lymph glandular system, respiratory system, cardiovascular system, and genitalia were normal. On neurologic examination, reflexes were intact, and meningeal signs were negative.

Urinalysis; complete blood count; random blood sugar (RBS); serology for syphilis, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); obstetrics ultrasound; and blood group were done. Obstetrics ultrasound showed a twin intrauterine pregnancy with an anencephalic twin A and severe ventriculomegaly and lumbar myelo-meningocele in twin B (Table 1 ).

With the final diagnosis of a second-trimester twin pregnancy with a concordant fatal anomaly, the patient was admitted to the gynecology ward. In the ward, the patient was given mifepristone 200 mg orally. After 24 hours, 400 µg of misoprostol was inserted vaginally. A total of 8 hours later, she expelled twin A, weighing 120 g of anencephalic abortus with cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebral defect, and twin B, weighing 150 g of hydrocephalic abortus with a thoracic and lumbar vertebral defect, and protrusion of the intestine via the right side para umbilical area without the covering membrane (Fig. 1 A, B). The placenta was monochorionic.

A Twin abortuses with neural tube defects at Wallaga University Referral Hospital, Western Ethiopia, 2023. B Twin abortuses with neural tube defects and gastroschisis at Wallaga University Referral Hospital, Western Ethiopia, 2023

When compared with singleton pregnancies, the rates of congenital anomalies are higher with multiple pregnancies [ 5 , 6 ]. In fetuses in multiple gestations, these anatomic abnormalities are more commonly linked to monozygotic (MZ) twining than dizygotic (DZ) twining [ 2 , 7 ].

Anomalies may affect all organ systems, but the commonest involve cardiovascular and central nervous systems, followed by ophthalmic and gastrointestinal abnormalities [ 1 , 4 , 7 , 8 ]. The concordance rate of major congenital malformations is around 20% for monozygotic twins, with most dizygotic twin pairs being discordant [ 1 ]. Only in certain organ systems do monozygotic twins exhibit higher concordance rates than DZ twins [ 4 , 7 ]. Our case is MZ twins. In both twins, the neural nervous system was affected. The twin pairs had neural tube defects. One twin had gastroschisis.

Anomalies in singleton and twin pregnancies are associated with maternal exposure to various factors such as diazepam use, cigarette smoking, maternal obesity, and nutritional deficiencies [ 9 ]. Our case was complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. Because of repeated vomiting, it could result in nutritional deficiency, which could in turn result in neural tube defects and other anomalies.

There is limited published evidence about screening for structural abnormalities in twin or higher order pregnancies [ 10 ]. Careful sonographic surveys of fetal anatomy are indicated in multifetal pregnancies because the risk for congenital anomalies is increased [ 11 ]. A complete fetal anatomic survey is therefore recommended for all twin gestations at 18–22 weeks’ gestational age [ 12 ]. The accuracy of ultrasonography for detecting congenital fetal anomalies in multiple gestations has not been adequately studied in large series [ 11 ].

Following diagnosis of an anomaly affecting only one fetus, practitioners may face the dilemma of expectant management versus selective termination. If the option of selective fetocide is considered, the main variable determining the technique to achieve this aim is chorionicity [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. In a dichorionic pregnancy, passage of fetocidal agents from one twin into the circulation of the co-twin is unlikely due to the lack of placental anastomoses [ 13 , 14 ]. When monochorionic (MC) twins are complicated with discordant fetal anomalies, the management scheme will be much more complex [ 13 , 14 ]. In this case, selective termination needs to be performed by ensuring complete and permanent occlusion of both the arterial and venous flows in the umbilical cord of the affected twin. Bipolar cord coagulation under ultrasound guidance is associated with approximately 70–80% survival rates [ 14 , 15 ]. However, management of concordant fatal anomaly in twin pregnancy is not controversial [ 3 ]. In our case, both twins had fatal congenital anomalies, which required immediate termination of the pregnancy using misoprostol.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Hepatitis B surface antigen

Human immunodeficiency virus

Monozygotic

Rhesus factor

Venereal disease research laboratory

White blood count

Weber MA, Sebire NJ. Genetics and developmental pathology of twinning. Seminars Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010; 15(6): 313–318). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1744165X10000466 .

Cunningham F, Leveno KJ, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Spong CY, Casey BM. eds. Multifetal Pregnancy. Williams Obstetrics, 26e . McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed February 01, 2024. https://accessmedicine-mhmedical-com-443.webvpn.sysu.edu.cn/content.aspx?bookid=2977§ionid=263825445 .

Momo RJ, Sama JD, Meka E, Temgoua MN, Foumane P. Challenge in the management of twin pregnancy with anencephaly of one fetus in a low- income country: a case presentation. J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;7(3):81–4.

Article Google Scholar

Jung YM, Lee SM, Oh S, Lyoo SH, Park CW, Lee SD, Park JS, Jun JK. The concordance rate of non-chromosomal congenital malformations in twins based on zygosity: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128(5):857–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16463 .