- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Formative influences

Influence of the scientific revolution, work during the plague years.

- Inaugural lectures at Trinity

- Controversy

- Influence of the Hermetic tradition

- Planetary motion

- Universal gravitation

- Warden of the mint

- Interest in religion and theology

- Leader of English science

- Final years

What is Isaac Newton most famous for?

How was isaac newton educated, what was isaac newton’s childhood like.

- What is the Scientific Revolution?

- How is the Scientific Revolution connected to the Enlightenment?

Isaac Newton

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Isaac Newton Institute of Mathematical Sciences - Who was Isaac Newton?

- Science Kids - Fun Science and Technology for Kids - Biography of Isaac Newton

- Trinity College Dublin - School of mathematics - Biography of Sir Isaac Newton

- World History Encyclopedia - Isaac Newton

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Isaac Newton

- University of British Columbia - Physics and Astronomy Department - The Life and Work of Newton

- LiveScience - Biography of Isaac Newton

- Physics LibreTexts - Newton's Laws of Motion

- Isaac Newton - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Isaac Newton - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Although Isaac Newton is well known for his discoveries in optics (white light composition) and mathematics ( calculus ), it is his formulation of the three laws of motion —the basic principles of modern physics—for which he is most famous. His formulation of the laws of motion resulted in the law of universal gravitation .

After interrupted attendance at the grammar school in Grantham, Lincolnshire , England , Isaac Newton finally settled down to prepare for university, going on to Trinity College, Cambridge , in 1661, somewhat older than his classmates. There he immersed himself in Aristotle ’s work and discovered the works of René Descartes before graduating in 1665 with a bachelor’s degree.

Isaac Newton was born to a widowed mother (his father died three months prior) and was not expected to survive, being tiny and weak. Shortly thereafter Newton was sent by his stepfather, the well-to-do minister Barnabas Smith, to live with his grandmother and was separated from his mother until Smith’s death in 1653.

What did Isaac Newton write?

Isaac Newton is widely known for his published work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), commonly known as the Principia . His laws of motion first appeared in this work. It is one of the most important single works in the history of modern science .

Recent News

Isaac Newton (born December 25, 1642 [January 4, 1643, New Style], Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire , England—died March 20 [March 31], 1727, London) was an English physicist and mathematician who was the culminating figure of the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century. In optics , his discovery of the composition of white light integrated the phenomena of colours into the science of light and laid the foundation for modern physical optics. In mechanics , his three laws of motion , the basic principles of modern physics , resulted in the formulation of the law of universal gravitation . In mathematics , he was the original discoverer of the infinitesimal calculus . Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica ( Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy , 1687) was one of the most important single works in the history of modern science.

Born in the hamlet of Woolsthorpe, Newton was the only son of a local yeoman , also Isaac Newton, who had died three months before, and of Hannah Ayscough. That same year, at Arcetri near Florence, Galileo Galilei had died; Newton would eventually pick up his idea of a mathematical science of motion and bring his work to full fruition . A tiny and weak baby, Newton was not expected to survive his first day of life, much less 84 years. Deprived of a father before birth, he soon lost his mother as well, for within two years she married a second time; her husband, the well-to-do minister Barnabas Smith, left young Isaac with his grandmother and moved to a neighbouring village to raise a son and two daughters. For nine years, until the death of Barnabas Smith in 1653, Isaac was effectively separated from his mother, and his pronounced psychotic tendencies have been ascribed to this traumatic event. That he hated his stepfather we may be sure. When he examined the state of his soul in 1662 and compiled a catalog of sins in shorthand, he remembered “Threatning my father and mother Smith to burne them and the house over them.” The acute sense of insecurity that rendered him obsessively anxious when his work was published and irrationally violent when he defended it accompanied Newton throughout his life and can plausibly be traced to his early years.

After his mother was widowed a second time, she determined that her first-born son should manage her now considerable property. It quickly became apparent, however, that this would be a disaster, both for the estate and for Newton. He could not bring himself to concentrate on rural affairs—set to watch the cattle, he would curl up under a tree with a book. Fortunately, the mistake was recognized, and Newton was sent back to the grammar school in Grantham , where he had already studied, to prepare for the university. As with many of the leading scientists of the age, he left behind in Grantham anecdotes about his mechanical ability and his skill in building models of machines, such as clocks and windmills . At the school he apparently gained a firm command of Latin but probably received no more than a smattering of arithmetic. By June 1661 he was ready to matriculate at Trinity College , Cambridge , somewhat older than the other undergraduates because of his interrupted education.

When Newton arrived in Cambridge in 1661, the movement now known as the Scientific Revolution was well advanced, and many of the works basic to modern science had appeared. Astronomers from Nicolaus Copernicus to Johannes Kepler had elaborated the heliocentric system of the universe . Galileo had proposed the foundations of a new mechanics built on the principle of inertia . Led by René Descartes , philosophers had begun to formulate a new conception of nature as an intricate, impersonal, and inert machine. Yet as far as the universities of Europe, including Cambridge, were concerned, all this might well have never happened. They continued to be the strongholds of outmoded Aristotelianism , which rested on a geocentric view of the universe and dealt with nature in qualitative rather than quantitative terms.

Like thousands of other undergraduates, Newton began his higher education by immersing himself in Aristotle’s work. Even though the new philosophy was not in the curriculum, it was in the air. Some time during his undergraduate career, Newton discovered the works of the French natural philosopher Descartes and the other mechanical philosophers, who, in contrast to Aristotle, viewed physical reality as composed entirely of particles of matter in motion and who held that all the phenomena of nature result from their mechanical interaction. A new set of notes, which he entitled “ Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae ” (“Certain Philosophical Questions”), begun sometime in 1664, usurped the unused pages of a notebook intended for traditional scholastic exercises; under the title he entered the slogan “Amicus Plato amicus Aristoteles magis amica veritas” (“Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my best friend is truth”). Newton’s scientific career had begun.

The “Quaestiones” reveal that Newton had discovered the new conception of nature that provided the framework of the Scientific Revolution. He had thoroughly mastered the works of Descartes and had also discovered that the French philosopher Pierre Gassendi had revived atomism , an alternative mechanical system to explain nature. The “Quaestiones” also reveal that Newton already was inclined to find the latter a more attractive philosophy than Cartesian natural philosophy, which rejected the existence of ultimate indivisible particles. The works of the 17th-century chemist Robert Boyle provided the foundation for Newton’s considerable work in chemistry. Significantly, he had read Henry More , the Cambridge Platonist, and was thereby introduced to another intellectual world, the magical Hermetic tradition, which sought to explain natural phenomena in terms of alchemical and magical concepts. The two traditions of natural philosophy, the mechanical and the Hermetic, antithetical though they appear, continued to influence his thought and in their tension supplied the fundamental theme of his scientific career.

Although he did not record it in the “Quaestiones,” Newton had also begun his mathematical studies. He again started with Descartes, from whose La Géometrie he branched out into the other literature of modern analysis with its application of algebraic techniques to problems of geometry . He then reached back for the support of classical geometry. Within little more than a year, he had mastered the literature; and, pursuing his own line of analysis, he began to move into new territory. He discovered the binomial theorem , and he developed the calculus , a more powerful form of analysis that employs infinitesimal considerations in finding the slopes of curves and areas under curves.

By 1669 Newton was ready to write a tract summarizing his progress, De Analysi per Aequationes Numeri Terminorum Infinitas (“On Analysis by Infinite Series”), which circulated in manuscript through a limited circle and made his name known. During the next two years he revised it as De methodis serierum et fluxionum (“ On the Methods of Series and Fluxions ”). The word fluxions , Newton’s private rubric, indicates that the calculus had been born. Despite the fact that only a handful of savants were even aware of Newton’s existence, he had arrived at the point where he had become the leading mathematician in Europe.

When Newton received the bachelor’s degree in April 1665, the most remarkable undergraduate career in the history of university education had passed unrecognized. On his own, without formal guidance, he had sought out the new philosophy and the new mathematics and made them his own, but he had confined the progress of his studies to his notebooks. Then, in 1665, the plague closed the university, and for most of the following two years he was forced to stay at his home, contemplating at leisure what he had learned. During the plague years Newton laid the foundations of the calculus and extended an earlier insight into an essay, “Of Colours,” which contains most of the ideas elaborated in his Opticks . It was during this time that he examined the elements of circular motion and, applying his analysis to the Moon and the planets , derived the inverse square relation that the radially directed force acting on a planet decreases with the square of its distance from the Sun —which was later crucial to the law of universal gravitation. The world heard nothing of these discoveries.

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

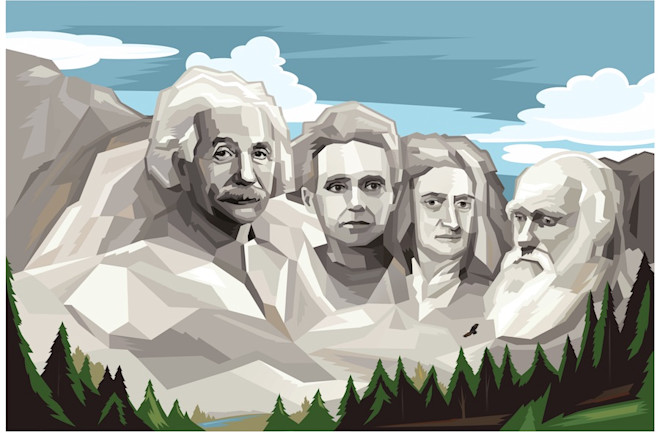

10 Famous Scientists and Their Contributions

Get to know the greatest scientists in the world. learn how these famous scientists changed the world as we know it through their contributions and discoveries..

From unraveling the mysteries of the cosmos to unearthing the origins of humanity, these famous scientists have not only expanded the boundaries of human knowledge but have also profoundly altered the way we live, work, and perceive the world around us. The relentless pursuit of knowledge by these visionary thinkers has propelled humanity forward in ways that were once unimaginable.

These exceptional individuals have made an extraordinary impact on fields including physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, and numerous others. Their contributions stand as a testament to the transformative power of human curiosity and the enduring impact of those who dared to ask questions, challenge the status quo, and change the world. Join us as we embark on a journey through the lives and legacies of the greatest scientists of all time.

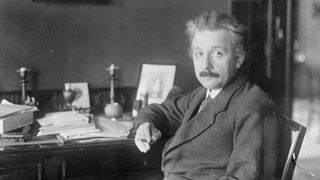

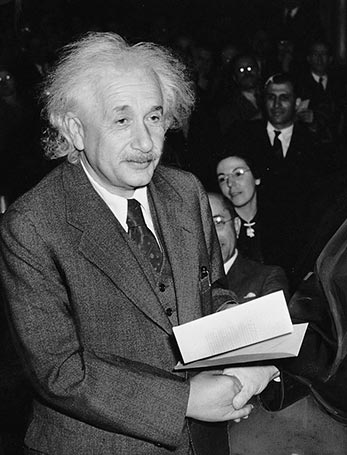

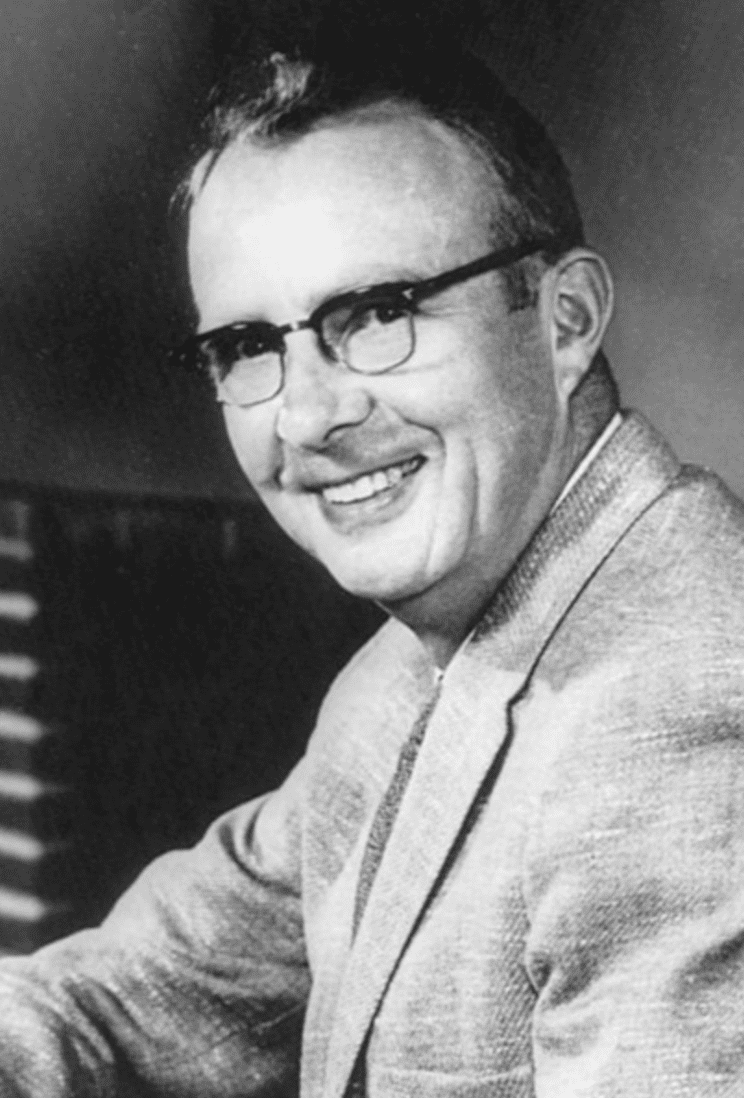

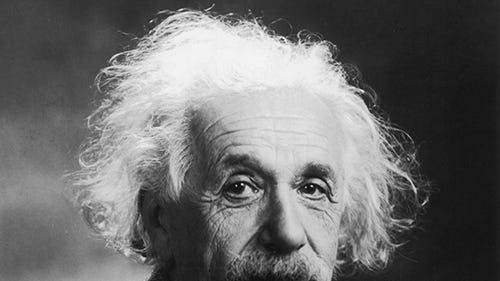

1. Albert Einstein: The Whole Package

Albert Einstein was not only a scientific genius but also a figure of enduring popularity and intrigue. His remarkable contributions to science, which include the famous equation E = mc2 and the theory of relativity , challenged conventional notions and reshaped our understanding of the universe.

Born in Ulm, Germany, in 1879, Einstein was a precocious child. As a teenager, he wrote a paper on magnetic fields. (Einstein never actually failed math, contrary to popular lore.) His career trajectory began as a clerk in the Swiss Patent Office in 1905, where he published his four groundbreaking papers, including his famous equation, E = mc2, which described the relationship between matter and energy.

Contributions

Einstein's watershed year of 1905 marked the publication of his most important papers, addressing topics such as Brownian motion , the photoelectric effect and special relativity. His work in special relativity introduced the idea that space and time are interwoven, laying the foundation for modern astronomy. In 1916, he expanded on his theory of relativity with the development of general relativity, proposing that mass distorts the fabric of space and time.

Although Einstein received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921, it wasn't for his work on general relativity but rather for his discovery of the photoelectric effect. His contributions to science earned him a prestigious place in the scientific community.

Key Moment

A crowd barged past dioramas, glass displays, and wide-eyed security guards in the American Museum of Natural History. Screams rang out as some runners fell and were trampled. Upon arriving at a lecture hall, the mob broke down the door.

The date was Jan. 8, 1930, and the New York museum was showing a film about Albert Einstein and his general theory of relativity. Einstein was not present, but 4,500 mostly ticketless people still showed up for the viewing. Museum officials told them “no ticket, no show,” setting the stage for, in the words of the Chicago Tribune , “the first science riot in history.”

Such was Einstein’s popularity. As a publicist might say, he was the whole package: distinctive look (untamed hair, rumpled sweater), witty personality (his quips, such as God not playing dice, would live on) and major scientific cred (his papers upended physics).

Read More: 5 Interesting Things About Albert Einstein

Einstein, who died of heart failure in 1955 , left behind a profound legacy in the world of science. His life's work extended beyond scientific discoveries, encompassing his role as a public intellectual, civil rights advocate, and pacifist.

Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity remains one of his most celebrated achievements. It predicted the existence of black holes and gravitational waves, with physicists recently measuring the waves from the collision of two black holes over a billion light-years away. General relativity also underpins the concept of gravitational lensing, enabling astronomers to study distant cosmic objects in unprecedented detail.

“Einstein remains the last, and perhaps only, physicist ever to become a household name,” says James Overduin, a theoretical physicist at Towson University in Maryland.

Einstein's legacy goes beyond his scientific contributions. He is remembered for his imaginative thinking, a quality that led to his greatest insights. His influence as a public figure and his advocacy for civil rights continue to inspire generations.

“I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination,” he said in a Saturday Evening Post interview. “Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

— Mark Barna

Read More: 20 Brilliant Albert Einstein Quotes

2. Marie Curie: She Went Her Own Way

Marie Curie's remarkable journey to scientific acclaim was characterized by determination and a thirst for knowledge. Living amidst poverty and political turmoil, her unwavering passion for learning and her contributions to the fields of physics and chemistry have made an everlasting impact on the world of science.

Marie Curie , born as Maria Salomea Sklodowska in 1867 in Warsaw, Poland, faced immense challenges during her early life due to both her gender and her family's financial struggles. Her parents, fervent Polish patriots, sacrificed their wealth in support of their homeland's fight for independence from Russian, Austrian, and Prussian rule. Despite these hardships, Marie's parents, who were educators themselves, instilled a deep love for learning and Polish culture in her.

Marie and her sisters were initially denied higher education opportunities due to societal restrictions and lack of financial resources. In response, Marie and her sister Bronislawa joined a clandestine organization known as the Flying University, aimed at providing Polish education, forbidden under Russian rule.

Marie Curie's path to scientific greatness began when she arrived in Paris in 1891 to pursue higher education. Inspired by the work of French physicist Henri Becquerel, who discovered the emissions of uranium, Marie chose to explore uranium's rays for her Ph.D. thesis. Her research led her to the groundbreaking discovery of radioactivity, revealing that matter could undergo atomic-level transformations.

Marie Curie collaborated with her husband, Pierre Curie, and together they examined uranium-rich minerals, ultimately discovering two new elements, polonium and radium. Their work was published in 1898, and within just five months, they announced the discovery of radium.

In 1903, Marie Curie, Pierre Curie, and Henri Becquerel were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering work in radioactivity. Marie became the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize, marking a historic achievement.

Read More: 5 Things You Didn't Know About Marie Curie

Tragedy struck in 1906 when Pierre Curie died suddenly in a carriage accident. Despite her grief, Marie Curie persevered and continued her research, taking over Pierre's position at the University of Paris. In 1911, she earned her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her remarkable contributions to the fields of polonium and radium.

Marie Curie's legacy extended beyond her Nobel Prizes. She made significant contributions to the fields of radiology and nuclear physics. She founded the Radium Institute in Paris, which produced its own Nobel laureates, and during World War I, she led France's first military radiology center, becoming the first female medical physicist.

Marie Curie died in 1934 from a type of anemia that likely stemmed from her exposure to such extreme radiation during her career. In fact, her original notes and papers are still so radioactive that they’re kept in lead-lined boxes, and you need protective gear to view them

Marie Curie's legacy endures as one of the greatest scientists of all time. She remains the only person to receive Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields, a testament to her exceptional contributions to science. Her groundbreaking research in radioactivity revolutionized our understanding of matter and energy, leaving her mark on the fields of physics, chemistry, and medicine.

— Lacy Schley

Read More: Marie Curie: Iconic Scientist, Nobel Prize Winner … War Hero?

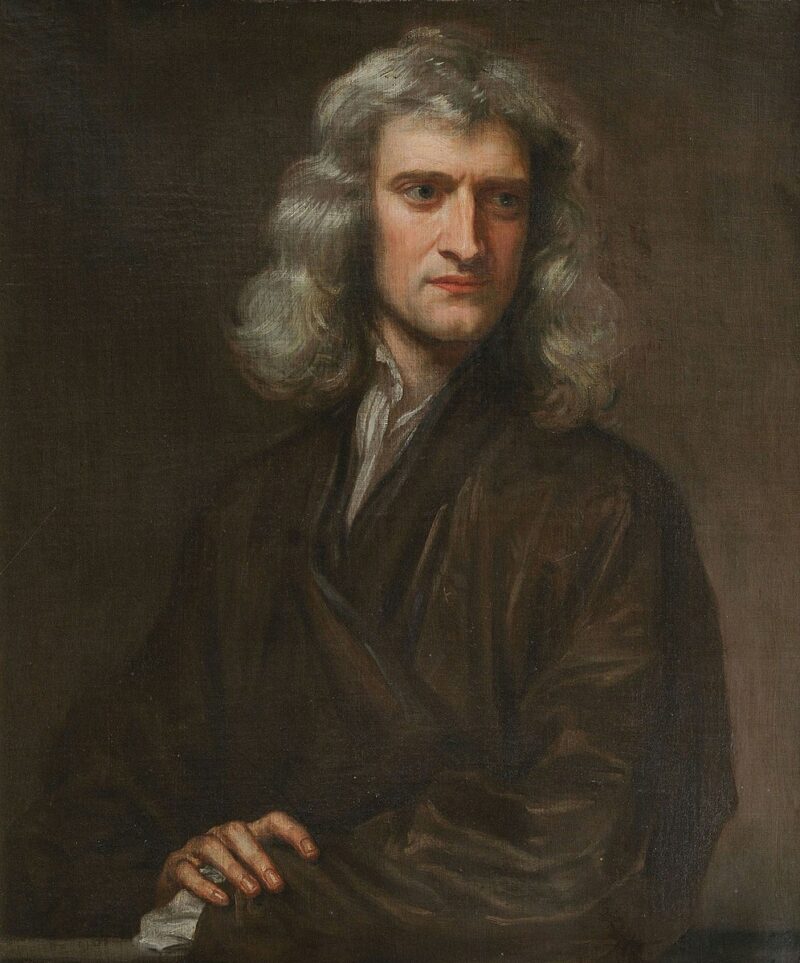

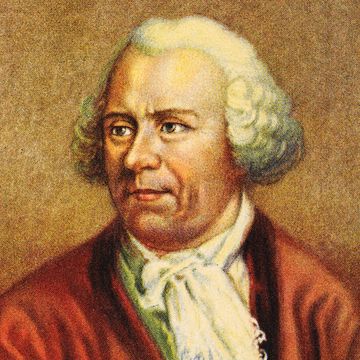

3. Isaac Newton: The Man Who Defined Science on a Bet

Isaac Newton was an English mathematician, physicist and astronomer who is widely recognized as one of the most influential scientists in history. He made groundbreaking contributions to various fields of science and mathematics and is considered one of the key figures in the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

Isaac Newton was born on Christmas Day in 1642. Despite being a sickly infant, his survival was an achievement in itself. Just 23 years later, with Cambridge University closed due to the plague, Newton embarked on groundbreaking discoveries that would bear his name. He invented calculus, a new form of mathematics, as part of his scientific journey.

Newton's introverted nature led him to withhold his findings for decades. It was only through the persistent efforts of his friend, Edmund Halley, who was famous for discovering comets, that Newton finally agreed to publish. Halley's interest was piqued due to a bet about planetary orbits, and Newton, having already solved the problem, astounded him with his answer.

Read More: 5 Eccentric Facts About Isaac Newton

The culmination of Newton's work was the "Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica," commonly known as the Principia , published in 1687. This monumental work not only described the motion of planets and projectiles but also revealed the unifying force of gravity, demonstrating that it governed both heavenly and earthly bodies. Newton's laws became the key to unlocking the universe's mysteries.

Newton's dedication to academia was unwavering. He rarely left his room except to deliver lectures, even if it meant addressing empty rooms. His contributions extended beyond the laws of motion and gravitation to encompass groundbreaking work in optics, color theory, the development of reflecting telescopes bearing his name, and fundamental advancements in mathematics and heat.

In 1692, Newton faced a rare failure and experienced a prolonged nervous breakdown, possibly exacerbated by mercury poisoning from his alchemical experiments. Although he ceased producing scientific work, his influence in the field persisted.

Achievements

Newton spent his remaining three decades modernizing England's economy and pursuing criminals. In 1696, he received a royal appointment as the Warden of the Mint in London. Despite being viewed as a cushy job with a handsome salary, Newton immersed himself in the role. He oversaw the recoinage of English currency, provided economic advice, established the gold standard, and introduced ridged coins that prevented the tampering of precious metals. His dedication extended to pursuing counterfeiters vigorously, even infiltrating London's criminal networks , and witnessing their executions.

Newton's reputation among his peers was marred by his unpleasant demeanor. He had few close friends, never married, and was described as "insidious, ambitious, and excessively covetous of praise, and impatient of contradiction" by Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed. Newton held grudges for extended periods and engaged in famous feuds, notably with German scientist Gottfried Leibniz over the invention of calculus and English scientist Robert Hooke.

Isaac Newton's legacy endures as one of the world's greatest scientists. His contributions to physics, mathematics, and various scientific disciplines shifted human understanding. Newton's laws of motion and gravitation revolutionized the field of physics and continue to be foundational principles.

His work in optics and mathematics laid the groundwork for future scientific advancements. Despite his complex personality, Newton's legacy as a scientific visionary remains unparalleled.

How fitting that the unit of force is named after stubborn, persistent, amazing Newton, himself a force of nature.

— Bill Andrews

Read More: Isaac Newton, World's Most Famous Alchemist

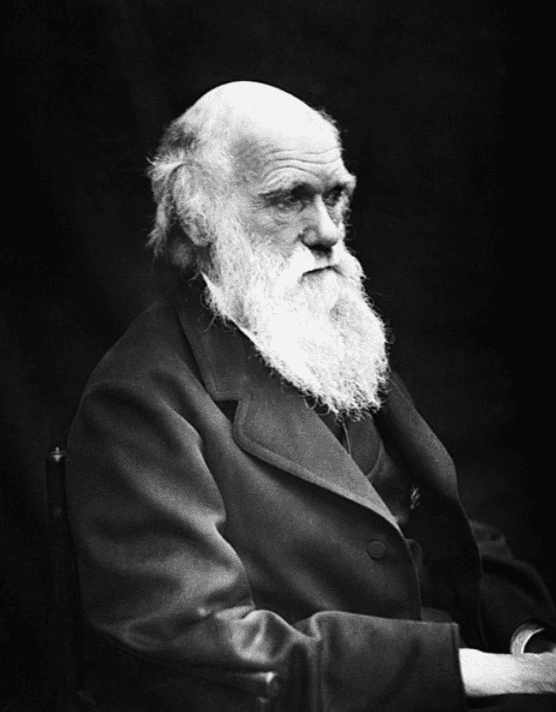

4. Charles Darwin: Delivering the Evolutionary Gospel

Charles Darwin has become one of the world's most renowned scientists. His inspiration came from a deep curiosity about beetles and geology, setting him on a transformative path. His theory of evolution through natural selection challenged prevailing beliefs and left an enduring legacy that continues to shape the field of biology and our understanding of life on Earth.

Charles Darwin , an unlikely revolutionary scientist, began his journey with interests in collecting beetles and studying geology. As a young man, he occasionally skipped classes at the University of Edinburgh Medical School to explore the countryside. His path to becoming the father of evolutionary biology took an unexpected turn in 1831 when he received an invitation to join a world-spanning journey aboard the HMS Beagle .

During his five-year voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, Darwin observed and documented geological formations, various habitats and the diverse flora and fauna across the Southern Hemisphere. His observations led to a paradigm-shifting realization that challenged the prevailing Victorian-era theories of animal origins rooted in creationism.

Darwin noticed subtle variations within the same species based on their environments, exemplified by the unique beak shapes of Galapagos finches adapted to their food sources. This observation gave rise to the concept of natural selection, suggesting that species could change over time due to environmental factors, rather than divine intervention.

Read More: 7 Things You May Not Know About Charles Darwin

Upon his return, Darwin was initially hesitant to publish his evolutionary ideas, instead focusing on studying his voyage samples and producing works on geology, coral reefs and barnacles. He married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and they had ten children, with Darwin actively engaging as a loving and attentive father — an uncommon practice among eminent scientists of his era.

Darwin's unique interests in taxidermy , unusual food and his struggle with ill health did not deter him from his evolutionary pursuits. Over two decades, he meticulously gathered overwhelming evidence in support of evolution.

Publication

All of his observations and musings eventually coalesced into the tour de force that was On the Origin of Species , published in 1859 when Darwin was 50 years old. The 500-page book sold out immediately, and Darwin would go on to produce six editions, each time adding to and refining his arguments.

In non-technical language, the book laid out a simple argument for how the wide array of Earth’s species came to be. It was based on two ideas: that species can change gradually over time, and that all species face difficulties brought on by their surroundings. From these basic observations, it stands to reason that those species best adapted to their environments will survive and those that fall short will die out.

Despite facing fierce criticism from proponents of creationism and the religious establishment, Darwin's theory of natural selection and evolution eventually gained acceptance in the 1930s. His work revolutionized scientific thought and remains largely intact to this day.

His theory, meticulously documented and logically sound, has withstood the test of time and scrutiny. Jerry Coyne, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, emphasizes the profound impact of Darwin's theory, stating that it "changed people’s views in so short a time" and that "there’s nothing you can really say to go after the important aspects of Darwin’s theory."

— Nathaniel Scharping

Read More: 8 Inspirational Sayings From Charles Darwin

5. Nikola Tesla: Wizard of the Industrial Revolution

Nikola Tesla grips his hat in his hand. He points his cane toward Niagara Falls and beckons bystanders to turn their gaze to the future. This bronze Tesla — a statue on the Canadian side — stands atop an induction motor, the type of engine that drove the first hydroelectric power plant.

Nikola Tesla exhibited a remarkable aptitude for science and invention from an early age. His work in electricity, magnetism and wireless power transmission concepts, established him as an eccentric but brilliant pioneer in the field of electrical engineering.

Nikola Tesla , a Serbian-American engineer, was born in 1856 in what is now Croatia. His pioneering work in the field of electrical engineering laid the foundation for our modern electrified world. Tesla's groundbreaking designs played a crucial role in advancing alternating current (AC) technology during the early days of the electric age, enabling the transmission of electric power over vast distances, ultimately lighting up American homes.

One of Tesla's most significant contributions was the development of the Tesla coil , a high-voltage transformer that had a profound impact on electrical engineering. His innovative techniques allowed for wireless transmission of power, a concept that is still being explored today, particularly in the field of wireless charging, including applications in cell phones.

Tesla's visionary mind led him to propose audacious ideas, including a grand plan involving a system of towers that could harness energy from the environment and transmit both signals and electricity wirelessly around the world. While these ideas were intriguing, they were ultimately deemed impractical and remained unrealized. Tesla also claimed to have invented a "death ray," adding to his mystique.

Read More: What Did Nikola Tesla Do? The Truth Behind the Legend

Tesla's eccentric genius and prolific inventions earned him widespread recognition during his lifetime. He held numerous patents and made significant contributions to the field of electrical engineering. While he did not invent alternating current (AC), he played a pivotal role in its development and promotion. His ceaseless work and inventions made him a household name, a rare feat for scientists in his era.

In recent years, Tesla's legacy has taken on a life of its own, often overshadowing his actual inventions. He has become a symbol of innovation and eccentricity, inspiring events like San Diego Comic-Con, where attendees dress as Tesla. Perhaps most notably, the world's most famous electric car company bears his name, reflecting his ongoing influence on the electrification of transportation.

While Tesla's mystique sometimes veered into the realm of self-promotion and fantastical claims, his genuine contributions to electrical engineering cannot be denied. He may not have caused earthquakes with his inventions or single handedly discovered AC, but his visionary work and impact on the electrification of the world continue to illuminate our lives.

— Eric Betz

Read More: These 7 Famous Physicists Are Still Alive Today

6. Galileo Galilei: Discoverer of the Cosmos

Galileo Galilei , an Italian mathematician, made a pivotal contribution to modern astronomy around December 1609. At the age of 45, he turned a telescope towards the moon and ushered in a new era in the field.

His observations unveiled remarkable discoveries, such as the presence of four large moons orbiting Jupiter and the realization that the Milky Way's faint glow emanated from countless distant stars. Additionally, he identified sunspots on the surface of the sun and observed the phases of Venus, providing conclusive evidence that Venus orbited the sun within Earth's own orbit.

While Galileo didn't invent the telescope and wasn't the first to use one for celestial observations, his work undeniably marked a turning point in the history of science. His groundbreaking findings supported the heliocentric model proposed by Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who had revolutionized astronomy with his sun-centered solar system model .

Beyond his astronomical observations, Galileo made significant contributions to the understanding of motion. He demonstrated that objects dropped simultaneously would hit the ground at the same time, irrespective of their size, illustrating that gravity isn't dependent on an object's mass. His law of inertia also played a critical role in explaining the Earth's rotation.

Read More: 12 Fascinating Facts About Galileo Galilei You May Not Know

Galileo's discoveries, particularly his support for the Copernican model of the solar system, brought him into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church. In 1616, an inquisition ordered him to cease promoting heliocentrism, as it contradicted the church's geocentric doctrine based on Aristotle's outdated views of the cosmos.

The situation worsened in 1633 when Galileo published a work comparing the Copernican and Ptolemaic systems, further discrediting the latter. Consequently, the church placed him under house arrest, where he remained until his death in 1642.

Galileo's legacy endured despite the challenges he faced from religious authorities. His observations and pioneering work on celestial bodies and motion laid the foundation for modern astronomy and physics.

His law of inertia, in particular, would influence future scientists, including Sir Isaac Newton, who built upon Galileo's work to formulate a comprehensive set of laws of motion that continue to guide spacecraft navigation across the solar system today. Notably, NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter, launched centuries later, demonstrated the enduring relevance of Galileo's contributions to the field of space exploration.

Read More: Galileo Galilei's Legacy Went Beyond Science

7. Ada Lovelace: The Enchantress of Numbers

Ada Lovelace defied the conventions of her era and transformed the world of computer science. She is known as the world's first computer programmer. Her legacy endures, inspiring generations of computer scientists and earning her the title of the "Enchantress of Numbers.”

Ada Lovelace, born Ada Byron, made history as the world's first computer programmer, a remarkable achievement considering she lived a century before the advent of modern computers. Her journey into the world of mathematics and computing began in the early 1830s when she was just 17 years old.

Ada, the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, entered into a pivotal collaboration with British mathematician, inventor, and engineer Charles Babbage. Babbage had conceived plans for an intricate machine called the Difference Engine — essentially a massive mechanical calculator.

Read More: Meet Ada Lovelace, The First Computer Programmer

At a gathering in the 1830s, Babbage exhibited an incomplete prototype of his Difference Engine. Among the attendees was the young Ada Lovelace, who, despite her age, grasped the workings of the machine. This encounter marked the beginning of a profound working relationship and close friendship between Lovelace and Babbage that endured until her untimely death in 1852 at the age of 36. Inspired by Babbage's innovations, Lovelace recognized the immense potential of his latest concept, the Analytical Engine.

The Analytical Engine was more than a mere calculator. Its intricate mechanisms, coupled with the ability for users to input commands through punch cards, endowed it with the capacity to perform a wide range of mathematical tasks. Lovelace, in fact, went a step further by crafting instructions for solving a complex mathematical problem, effectively creating what many historians later deemed the world's first computer program. In her groundbreaking work, Lovelace laid the foundation for computer programming, defining her legacy as one of the greatest scientists.

Ada Lovelace's contributions to the realm of "poetical science," as she termed it, are celebrated as pioneering achievements in computer programming and mathematics. Despite her tumultuous personal life marked by gambling and scandal, her intellectual brilliance and foresight into the potential of computing machines set her apart. Charles Babbage himself described Lovelace as an "enchantress" who wielded a remarkable influence over the abstract realm of science, a force equivalent to the most brilliant male intellects of her time.

Read More: Meet 10 Women in Science Who Changed the World

8. Pythagoras: Math's Mystery Man

Pythagoras left an enduring legacy in the world of mathematics that continues to influence the field to this day. While his famous Pythagorean theorem , which relates the sides of a right triangle, is well-known, his broader contributions to mathematics and his belief in the fundamental role of numbers in the universe shaped the foundations of geometry and mathematical thought for centuries to come.

Pythagoras , a Greek philosopher and mathematician, lived in the sixth century B.C. He is credited with the Pythagorean theorem, although the origins of this mathematical concept are debated.

Pythagoras is most famous for the Pythagorean theorem, which relates the lengths of the sides of a right triangle. While he may not have been the first to discover it, he played a significant role in its development. His emphasis on the importance of mathematical concepts laid the foundation for modern geometry.

Pythagoras did not receive formal awards, but his legacy in mathematics and geometry is considered one of the cornerstones of scientific knowledge.

Pythagoras' contributions to mathematics, particularly the Pythagorean theorem, have had a lasting impact on science and education. His emphasis on the importance of mathematical relationships and the certainty of mathematical proofs continues to influence the way we understand the world.

Read More: The Origin Story of Pythagoras and His Cult Followers

9. Carl Linnaeus: Say His Name(s)

Carl Linnaeus embarked on a mission to improve the chaos of naming living organisms. His innovative system of binomial nomenclature not only simplified the process of scientific communication but also laid the foundation for modern taxonomy, leaving an enduring legacy in the field of biology.

It started in Sweden: a functional, user-friendly innovation that took over the world, bringing order to chaos. No, not an Ikea closet organizer. We’re talking about the binomial nomenclature system , which has given us clarity and a common language, devised by Carl Linnaeus.

Linnaeus, born in southern Sweden in 1707, was an “intensely practical” man, according to Sandra Knapp, a botanist and taxonomist at the Natural History Museum in London. He lived at a time when formal scientific training was scant and there was no system for referring to living things. Plants and animals had common names, which varied from one location and language to the next, and scientific “phrase names,” cumbersome Latin descriptions that could run several paragraphs.ccjhhg

While Linnaeus is often hailed as the father of taxonomy, his primary focus was on naming rather than organizing living organisms into evolutionary hierarchies. The task of ordering species would come later, notably with the work of Charles Darwin in the following century. Despite advancements in our understanding of evolution and the impact of genetic analysis on biological classification, Linnaeus' naming system endures as a simple and adaptable means of identification.

The 18th century was also a time when European explorers were fanning out across the globe, finding ever more plants and animals new to science.

“There got to be more and more things that needed to be described, and the names were becoming more and more complex,” says Knapp.

Linnaeus, a botanist with a talent for noticing details, first used what he called “trivial names” in the margins of his 1753 book Species Plantarum . He intended the simple Latin two-word construction for each plant as a kind of shorthand, an easy way to remember what it was.

“It reflected the adjective-noun structure in languages all over the world,” Knapp says of the trivial names, which today we know as genus and species. The names moved quickly from the margins of a single book to the center of botany, and then all of biology. Linnaeus started a revolution — positioning him as one of the greatest scientists — but it was an unintentional one.

Today we regard Linnaeus as the father of taxonomy, which is used to sort the entire living world into evolutionary hierarchies, or family trees. But the systematic Swede was mostly interested in naming things rather than ordering them, an emphasis that arrived the next century with Charles Darwin.

As evolution became better understood and, more recently, genetic analysis changed how we classify and organize living things, many of Linnaeus’ other ideas have been supplanted. But his naming system, so simple and adaptable, remains.

“It doesn’t matter to the tree in the forest if it has a name,” Knapp says. “But by giving it a name, we can discuss it. Linnaeus gave us a system so we could talk about the natural world.”

— Gemma Tarlach

Read More: Is Plant Communication a Real Thing?

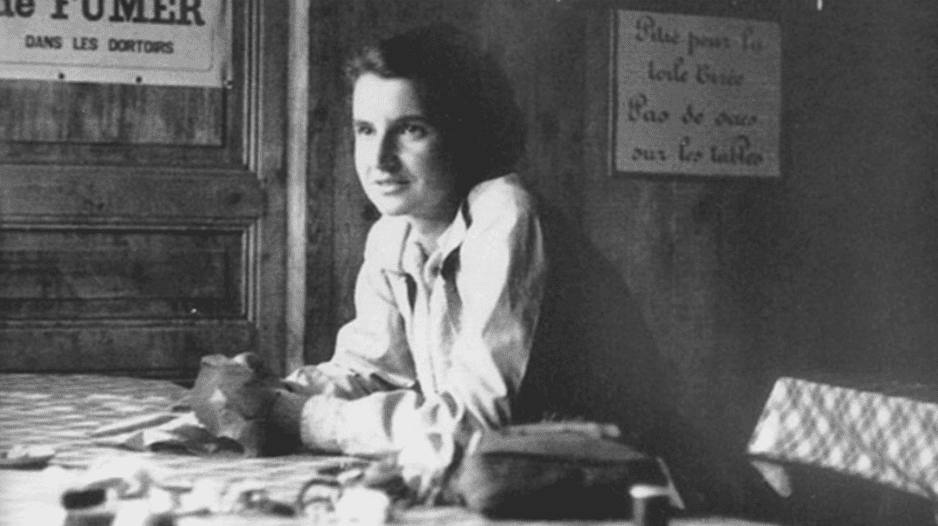

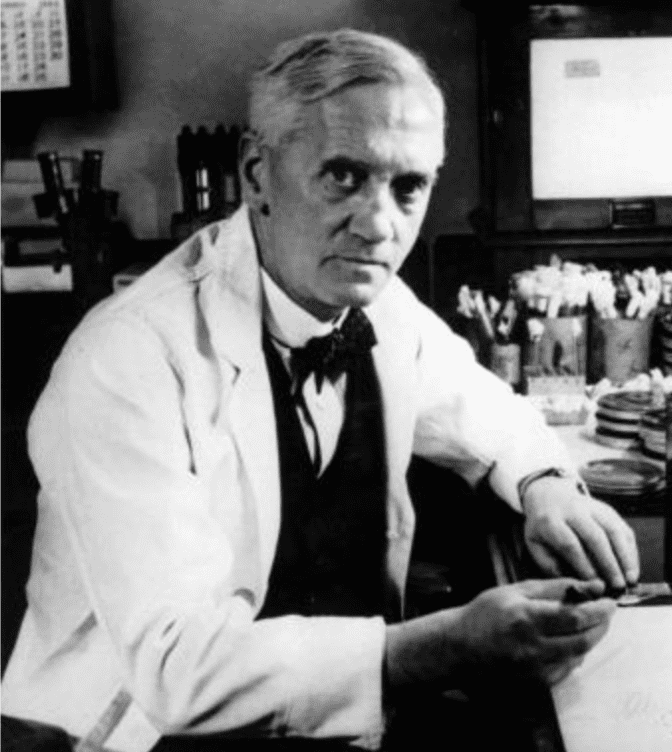

10. Rosalind Franklin: The Hero Denied Her Due

Rosalind Franklin, a brilliant and tenacious scientist, transformed the world of molecular biology. Her pioneering work in X-ray crystallography and groundbreaking research on the structure of DNA propelled her to the forefront of scientific discovery. Yet, her remarkable contributions were often overshadowed, and her legacy is not only one of scientific excellence but also a testament to the persistence and resilience of a scientist who deserved greater recognition in her time.

Rosalind Franklin , one of the greatest scientists of her time, was a British-born firebrand and perfectionist. While she had a reputation for being somewhat reserved and difficult to connect with, those who knew her well found her to be outgoing and loyal. Franklin's brilliance shone through in her work, particularly in the field of X-ray crystallography , an imaging technique that revealed molecular structures based on scattered X-ray beams. Her early research on the microstructures of carbon and graphite remains influential in the scientific community.

However, it was Rosalind Franklin's groundbreaking work with DNA that would become her most significant contribution. During her time at King's College London in the early 1950s, she came close to proving the double-helix theory of DNA. Her achievement was epitomized in "photograph #51," which was considered the finest image of a DNA molecule at that time. Unfortunately, her work was viewed by others, notably James Watson and Francis Crick.

Watson saw photograph #51 through her colleague Maurice Wilkins, and Crick received unpublished data from a report Franklin had submitted to the council. In 1953, Watson and Crick published their iconic paper in "Nature," loosely citing Franklin's work, which also appeared in the same issue.

Rosalind Franklin's pivotal role in elucidating the structure of DNA was overlooked when the Nobel Prize was awarded in 1962 to James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins. This omission is widely regarded as one of the major snubs of the 20th century in the field of science.

Despite her groundbreaking work and significant contributions to science, Franklin's life was tragically cut short. In 1956, at the height of her career, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, possibly linked to her extensive X-ray work. Remarkably, she continued to work in the lab until her passing in 1958 at the young age of 37.

Rosalind Franklin's legacy endures not only for her achievements but also for the recognition she deserved but did not receive during her lifetime. She was known for her extreme clarity and perfectionism in all her scientific endeavors, changing the field of molecular biology. While many remember her for her contributions, she is also remembered for how her work was overshadowed and underappreciated, a testament to her enduring influence on the world of science.

“As a scientist, Miss Franklin was distinguished by extreme clarity and perfection in everything she undertook,” Bernal wrote in her obituary, published in Nature . Though it’s her achievements that close colleagues admired, most remember Franklin for how she was forgotten.

— Carl Engelking

Read More: The Unsung Heroes of Science

More Greatest Scientists: Our Personal Favorites

Isaac Asimov (1920–1992) Asimov was my gateway into science fiction, then science, then everything else. He penned some of the genre’s most iconic works — fleshing out the laws of robotics, the messiness of a galactic empire, the pitfalls of predicting the future — in simple, effortless prose. A trained biochemist, the Russian-born New Yorker wrote prolifically, producing over 400 books, not all science-related: Of the 10 Dewey Decimal categories, he has books in nine. — B.A.

Richard Feynman (1918–1988) Feynman played a part in most of the highlights of 20th-century physics. In 1941, he joined the Manhattan Project. After the war, his Feynman diagrams — for which he shared the ’65 Nobel Prize in Physics — became the standard way to show how subatomic particles interact. As part of the 1986 space shuttle Challenger disaster investigation, he explained the problems to the public in easily understandable terms, his trademark. Feynman was also famously irreverent, and his books pack lessons I live by. — E.B.

Robert FitzRoy (1805–1865) FitzRoy suffered for science, and for that I respect him. As captain of the HMS Beagle , he sailed Charles Darwin around the world, only to later oppose his shipmate’s theory of evolution while waving a Bible overhead. FitzRoy founded the U.K.’s Met Office in 1854, and he was a pioneer of prediction; he coined the term weather forecast. But after losing his fortunes, suffering from depression and poor health, and facing fierce criticism of his forecasting system, he slit his throat in 1865. — C.E.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) Lamarck may be remembered as a failure today, but to me, he represents an important step forward for evolutionary thinking . Before he suggested that species could change over time in the early 19th century, no one took the concept of evolution seriously. Though eventually proven wrong, Lamarck’s work brought the concept of evolution into the light and would help shape the theories of a young Charles Darwin. Science isn’t all about dazzling successes; it’s also a story of failures surmounted and incremental advances. — N.S.

Lucretius (99 B.C.–55 B.C.) My path to the first-century B.C. Roman thinker Titus Lucretius Carus started with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Michele de Montaigne, who cited him in their essays. Lucretius’ only known work, On the Nature of Things, is remarkable for its foreshadowing of Darwinism, humans as higher primates, the study of atoms and the scientific method — all contemplated in a geocentric world ruled by eccentric gods. — M.B.

Katharine McCormick (1875–1967) McCormick planned to attend medical school after earning her biology degree from MIT in 1904. Instead, she married rich. After her husband’s death in 1947, she used her inheritance to provide crucial funding for research on the hormonal birth control pill . She also fought to make her alma mater more accessible to women, leading to an all-female dormitory, allowing more women to enroll. As a feminist interested in science, I’d love to be friends with this badass advocate for women’s rights. — L.S.

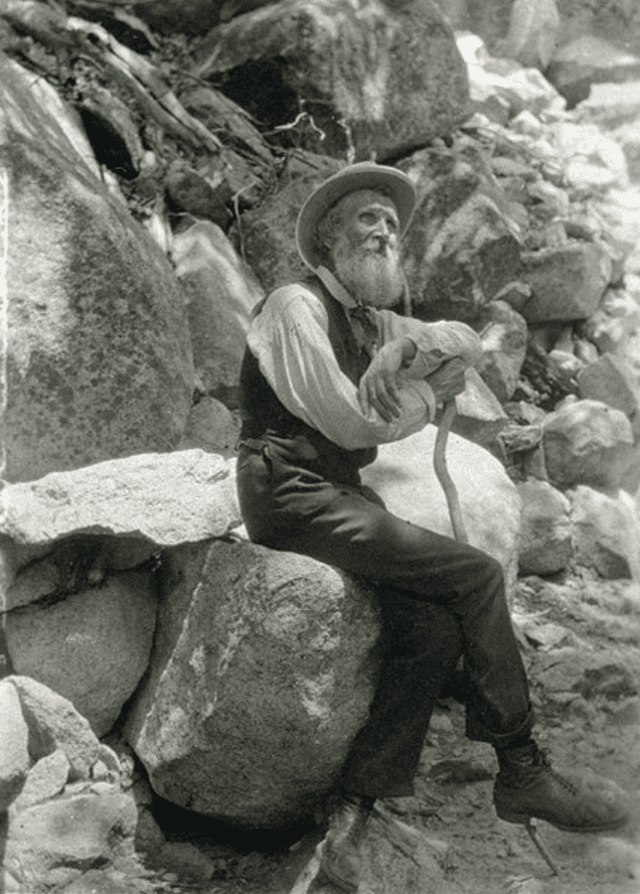

John Muir (1838–1914) In 1863, Muir abandoned his eclectic combination of courses at the University of Wisconsin to wander instead the “University of the Wilderness” — a school he never stopped attending. A champion of the national parks (enough right there to make him a hero to me!), Muir fought vigorously for conservation and warned, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” It’s a reminder we need today, more than ever. — Elisa Neckar

Rolf O. Peterson (1944–) Peterson helms the world’s longest-running study of the predator-prey relationship in the wild, between wolves and moose on Isle Royale in the middle of Lake Superior. He’s devoted more than four decades to the 58-year wildlife ecology project, a dedication and passion indicative, to me, of what science is all about. As the wolf population has nearly disappeared and moose numbers have climbed, patience and emotional investment like his are crucial in the quest to learn how nature works. — Becky Lang

Marie Tharp (1920–2006) I love maps. So did geologist and cartographer Tharp . In the mid-20th century, before women were permitted aboard research vessels, Tharp explored the oceans from her desk at Columbia University. With the seafloor — then thought to be nearly flat — her canvas, and raw data her inks, she revealed a landscape of mountain ranges and deep trenches. Her keen eye also spotted the first hints of plate tectonics at work beneath the waves. Initially dismissed, Tharp’s observations would become crucial to proving continental drift. — G.T.

Read more: The Dynasties That Changed Science

Making Science Popular With Other Greatest Scientists

Science needs to get out of the lab and into the public eye. Over the past hundred years or so, these other greatest scientists have made it their mission. They left their contributions in multiple sciences while making them broadly available to the general public.

Sean M. Carroll (1966– ) : The physicist (and one-time Discover blogger) has developed a following among space enthusiasts through his lectures, television appearances and books, including The Particle at the End of the Universe, on the Higgs boson .

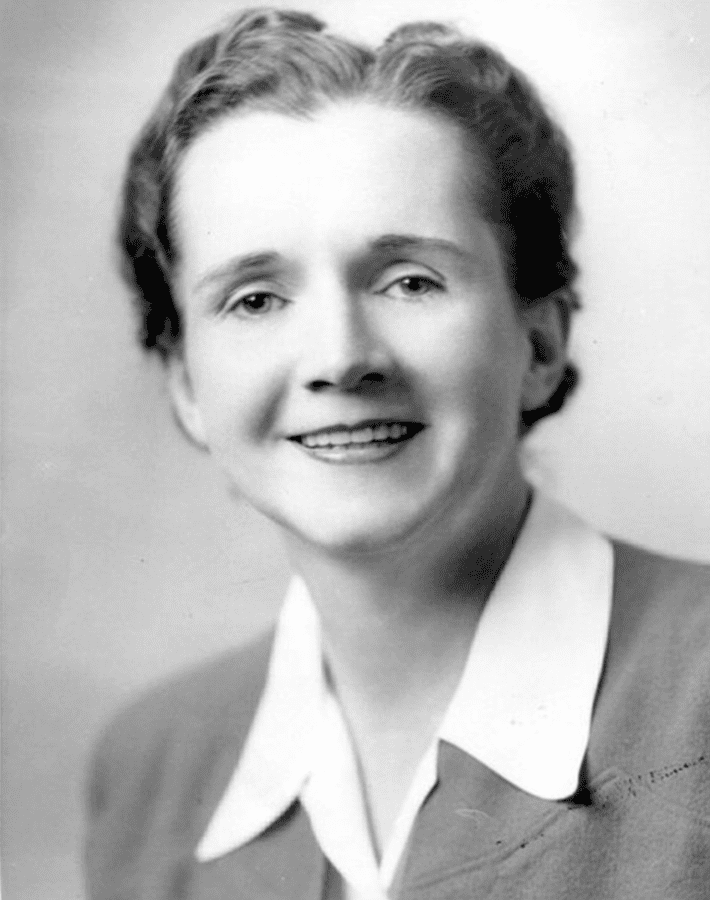

Rachel Carson (1907–1964) : With her 1962 book Silent Spring , the biologist energized a nascent environmental movement. In 2006, Discover named Silent Spring among the top 25 science books of all time.

Richard Dawkins (1941– ) : The biologist, a charismatic speaker, first gained public notoriety in 1976 with his book The Selfish Gene , one of his many works on evolution .

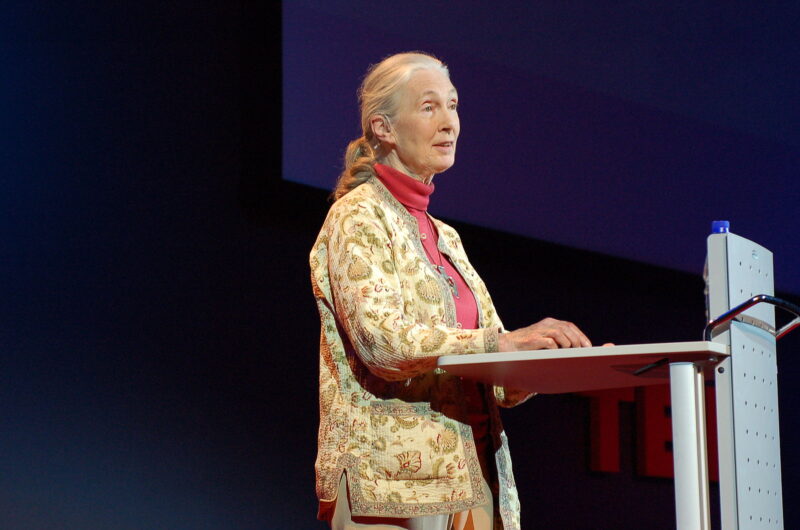

Jane Goodall (1934– ) : Studying chimpanzees in Tanzania, Goodall’s patience and observational skills led to fresh insights into their behavior — and led her to star in a number of television documentaries.

Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002) : In 1997, the paleontologist Gould was a guest on The Simpson s, a testament to his broad appeal. Among scientists, Gould was controversial for his idea of evolution unfolding in fits and starts rather than in a continuum.

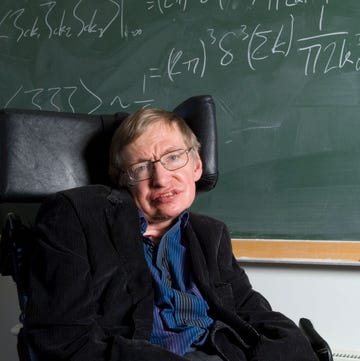

Stephen Hawking (1942–2018) : His books’ titles suggest the breadth and boldness of his ideas: The Universe in a Nutshell, The Theory of Everything . “My goal is simple,” he has said. “It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is and why it exists at all.”

Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) : If Henry Thoreau and John Muir primed the pump for American environmentalism, Leopold filled the first buckets . His posthumously published A Sand County Almanac is a cornerstone of modern environmentalism.

Bill Nye (1955– ) : What should an engineer and part-time stand-up comedian do with his life? For Nye, the answer was to become a science communicator . In the ’90s, he hosted a popular children’s science show and more recently has been an eloquent defender of evolution in public debates with creationists.

Oliver Sacks (1933–2015) : The neurologist began as a medical researcher , but found his calling in clinical practice and as a chronicler of strange medical maladies, most famously in his book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

Carl Sagan (1934–1996) : It’s hard to hear someone say “billions and billions” and not hear Sagan’s distinctive voice , and remember his 1980 Cosmos: A Personal Voyage miniseries. Sagan brought the wonder of the universe to the public in a way that had never happened before.

Neil deGrasse Tyson (1958– ) : The astrophysicist and gifted communicator is Carl Sagan’s successor as champion of the universe . In a nod to Sagan’s Cosmos , Tyson hosted the miniseries Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey in 2014.

E.O. Wilson (1929–2021) : The prolific, Pulitzer Prize-winning biologist first attracted broad public attention with 1975’s Sociobiology: The New Synthesis . His subsequent works have filled many a bookshelf with provocative discussions of biodiversity, philosophy and the animals he has studied most closely: ants. — M.B.

Read More: Who Was Anna Mani, and How Was She a Pioneer for Women in STEM?

Science Stars: The Next Generation

As science progresses, so does the roll call of new voices and greatest scientists serving as bridges between lab and layman. Here are some of our favorite emerging science stars:

British physicist Brian Cox became a household name in the U.K. in less than a decade, thanks to his accessible explanations of the universe in TV and radio shows, books and public appearances.

Neuroscientist Carl Hart debunks anti-science myths supporting misguided drug policies via various media, including his memoir High Price .

From the Amazon forest to the dissecting table, YouTube star and naturalist Emily Graslie brings viewers into the guts of the natural world, often literally.

When not talking dinosaurs or head transplants on Australian radio, molecular biologist Upulie Divisekera coordinates @RealScientists , a rotating Twitter account for science outreach.

Mixing pop culture and chemistry, analytical chemist Raychelle Burks demystifies the molecules behind poisons, dyes and even Game of Thrones via video, podcast and blog.

Climate scientist and evangelical Christian Katharine Hayhoe preaches beyond the choir about the planetary changes humans are causing in PBS’ Global Weirding video series. — Ashley Braun

Read More: 6 Famous Archaeologists You Need to Know About

This article was originally published on April 11, 2017 and has since been updated with new information by the Discover staff.

- solar system

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Albert Einstein: Biography, facts and impact on science

A brief biography of Albert Einstein (March 14, 1879 - April 18, 1955), the scientist whose theories changed the way we think about the universe.

- Einstein's birthday and education

Einstein's wives and children

How einstein changed physics.

- Later years and death

Gravitational waves and relativity

Additional resources.

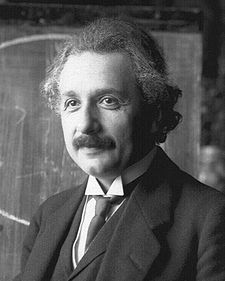

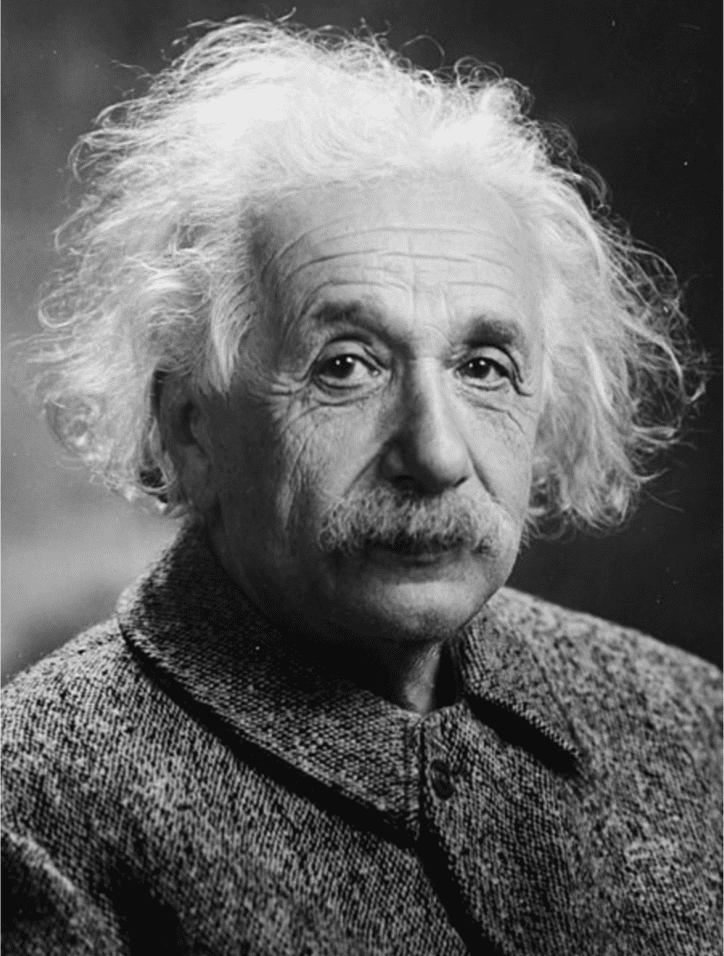

Albert Einstein was a German-American physicist and probably the most well-known scientist of the 20th century. He is famous for his theory of relativity , a pillar of modern physics that describes the dynamics of light and extremely massive entities, as well as his work in quantum mechanics , which focuses on the subatomic realm.

Albert Einstein's birthday and education

Einstein was born in Ulm, in the German state of Württemberg, on March 14, 1879, according to a biography from the Nobel Prize organization . His family moved to Munich six weeks later, and in 1885, when he was 6 years old, he began attending Petersschule, a Catholic elementary school.

Contrary to popular belief, Einstein was a good student. "Yesterday Albert received his grades, he was again number one, and his report card was brilliant," his mother once wrote to her sister, according to a German website dedicated to Einstein's legacy. But when he later switched to the Luitpold grammar school, young Einstein chafed under the school's authoritarian attitude, and his teacher once said of him, "never will he get anywhere."

In 1896, at age 17, Einstein entered the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich to be trained as a teacher in physics and mathematics. A few years later, he gained his diploma and acquired Swiss citizenship but was unable to find a teaching post. So he accepted a position as a technical assistant in the Swiss patent office.

Related: 10 discoveries that prove Einstein was right about the universe — and 1 that proves him wrong

Einstein married Mileva Maric, his longtime love and former student, in 1903. A year prior, they had a child out of wedlock, who was discovered by scholars only in the 1980s, when private letters revealed her existence. The daughter, called Lieserl in the letters, may have been mentally challenged and either died young or was adopted when she was a year old. Einstein had two other children with Maric, Hans Albert and Eduard, born in 1904 and 1910, respectively.

Einstein divorced Maric in 1919 and soon married his cousin Elsa Löwenthal, with whom he had been in a relationship since 1912.

Einstein obtained his doctorate in physics in 1905 — a year that's often known as his annus mirabilis ("year of miracles" in Latin), according to the Library of Congress . That year, he published four groundbreaking papers of significant importance in physics.

The first incorporated the idea that light could come in discrete particles called photons. This theory describes the photoelectric effect , the concept that underpins modern solar power. The second explained Brownian motion, or the random motion of particles or molecules. Einstein looked at the case of a dust mote moving randomly on the surface of water and suggested that water is made up of tiny, vibrating molecules that kick the dust back and forth.

The final two papers outlined his theory of special relativity, which showed how observers moving at different speeds would agree about the speed of light, which was a constant. These papers also introduced the equation E = mc^2, showing the equivalence between mass and energy. That finding is perhaps the most widely known aspect of Einstein's work. (In this infamous equation, E stands for energy, m represents mass and c is the constant speed of light).

In 1915, Einstein published four papers outlining his theory of general relativity, which updated Isaac Newton's laws of gravity by explaining that the force of gravity arose because massive objects warp the fabric of space-time. The theory was validated in 1919, when British astronomer Arthur Eddington observed stars at the edge of the sun during a solar eclipse and was able to show that their light was bent by the sun's gravitational well, causing shifts in their perceived positions.

Related: 8 Ways you can see Einstein's theory of relativity in real life

In 1921, he won the Nobel Prize in physics for his work on the photoelectric effect, though the committee members also mentioned his "services to Theoretical Physics" when presenting their award. The decision to give Einstein the award was controversial because the brilliant physicist was a Jew and a pacifist. Anti-Semitism was on the rise and relativity was not yet seen as a proven theory, according to an article from The Guardian .

Einstein was a professor at the University of Berlin for a time but fled Germany with Löwenthal in 1933, during the rise of Adolf Hitler. He renounced his German citizenship and moved to the United States to become a professor of theoretical physics at Princeton, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1940.

During this era, other researchers were creating a revolution by reformulating the rules of the smallest known entities in existence. The laws of quantum mechanics had been worked out by a group led by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr , and Einstein was intimately involved with their efforts.

Bohr and Einstein famously clashed over quantum mechanics. Bohr and his cohorts proposed that quantum particles behaved according to probabilistic laws, which Einstein found unacceptable, quipping that " God does not play dice with the universe ." Bohr's views eventually came to dominate much of contemporary thinking about quantum mechanics.

Einstein's later years and death

After he retired in 1945, Einstein spent most of his later years trying to unify gravity with electromagnetism in what's known as a unified field theory . Einstein died of a burst blood vessel near his heart on April 18, 1955, never unifying these forces.

Einstein's body was cremated and his ashes were spread in an undisclosed location, according to the American Museum of Natural History . But a doctor performed an unauthorized craniotomy before this and removed and saved Einstein's brain.

The brain has been the subject of many tests over the decades, which suggested that it had extra folding in the gray matter, the site of conscious thinking. In particular, there were more folds in the frontal lobes, which have been tied to abstract thought and planning. However, drawing any conclusions about intelligence based on a single specimen is problematic.

Related: Where is Einstein's brain?

In addition to his incredible legacy regarding relativity and quantum mechanics, Einstein conducted lesser-known research into a refrigeration method that required no motors, moving parts or coolant. He was also a tireless anti-war advocate, helping found the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , an organization dedicated to warning the public about the dangers of nuclear weapons .

Einstein's theories concerning relativity have so far held up spectacularly as a predictive models. Astronomers have found that, as the legendary physicist anticipated, the light of distant objects is lensed by massive, closer entities, a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, which has helped our understanding of the universe's evolution. The James Webb Space Telescope , launched in Dec. 2021, has utilized gravitational lensing on numerous occasions to detect light emitted near the dawn of time , dating to just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

In 2016, the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory also announced the first-ever direct detection of gravitational waves , created when massive neutron stars and black holes merge and generate ripples in the fabric of space-time. Further research published in 2023 found that the entire universe may be rippling with a faint "gravitational wave background," emitted by ancient, colliding black holes.

Find answers to frequently asked questions about Albert Einstein on the Nobel Prize website. Flip through digitized versions of Einstein's published and unpublished manuscripts at Einstein Archives Online. Learn about The Einstein Memorial at the National Academy of Sciences building in Washington, D.C.

This article was last updated on March 11, 2024 by Live Science editor Brandon Specktor to include new information about how Einstein's theories have been validated by modern experiments.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.

Stephen Hawking's black hole radiation paradox could finally be solved — if black holes aren't what they seem

Physicists unveil 1D gas made of pure light

9,000-year-old rock art of people swimming in what's now the arid Sahara

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb Telescope goes 'extreme' and spots baby stars at the edge of the Milky Way (image)

- 3 Why can't you suffocate by holding your breath?

- 4 Space photo of the week: Entangled galaxies form cosmic smiley face in new James Webb telescope image

- 5 Did Roman gladiators really fight to the death?

Scientific Biographies

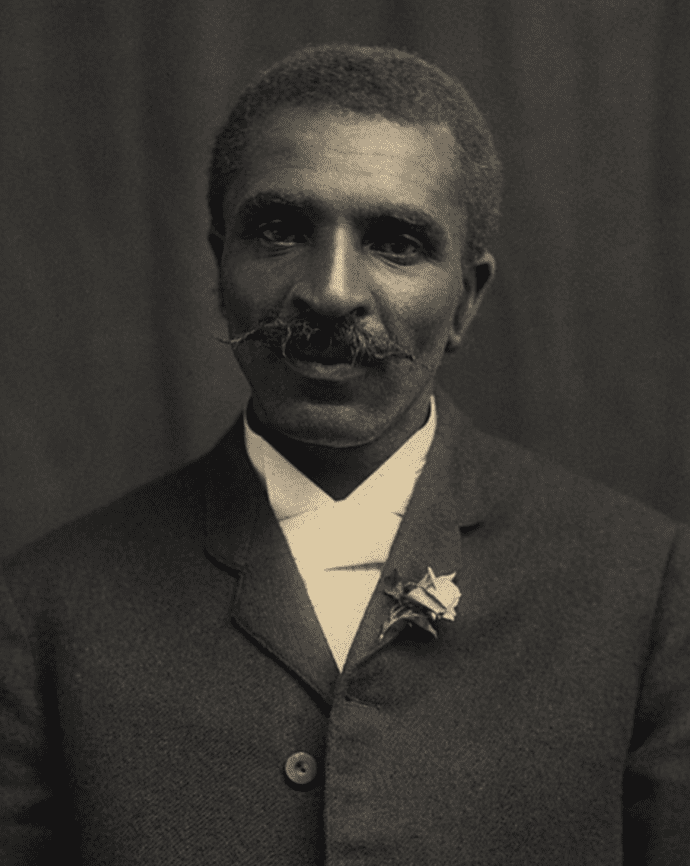

Mario molina.

As a postdoctoral researcher, Molina proposed that CFCs had the potential to destroy the earth’s protective ozone layer. The Mexican chemist eventually received a Nobel Prize for his discovery.

Filter biographies

About Scientific Biographies

Right Icon This ranking is based on an algorithm that combines various factors, including the votes of our users and search trends on the internet.

195.9K Votes

81.9K Votes

© Famous People All Rights Reserved

Biography Online

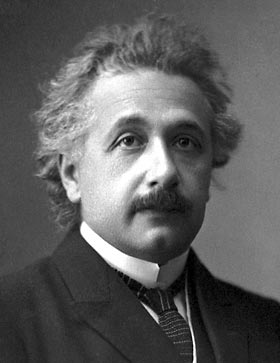

Albert Einstein Biography

Einstein is also well known as an original free-thinker, speaking on a range of humanitarian and global issues. After contributing to the theoretical development of nuclear physics and encouraging F.D. Roosevelt to start the Manhattan Project, he later spoke out against the use of nuclear weapons.

Born in Germany to Jewish parents, Einstein settled in Switzerland and then, after Hitler’s rise to power, the United States. Einstein was a truly global man and one of the undisputed genius’ of the Twentieth Century.

Early life Albert Einstein

Einstein was born 14 March 1879, in Ulm the German Empire. His parents were working-class (salesman/engineer) and non-observant Jews. Aged 15, the family moved to Milan, Italy, where his father hoped Albert would become a mechanical engineer. However, despite Einstein’s intellect and thirst for knowledge, his early academic reports suggested anything but a glittering career in academia. His teachers found him dim and slow to learn. Part of the problem was that Albert expressed no interest in learning languages and the learning by rote that was popular at the time.

“School failed me, and I failed the school. It bored me. The teachers behaved like Feldwebel (sergeants). I wanted to learn what I wanted to know, but they wanted me to learn for the exam.” Einstein and the Poet (1983)

At the age of 12, Einstein picked up a book on geometry and read it cover to cover. – He would later refer to it as his ‘holy booklet’. He became fascinated by maths and taught himself – becoming acquainted with the great scientific discoveries of the age.

Albert Einstein with wife Elsa

Despite Albert’s independent learning, he languished at school. Eventually, he was asked to leave by the authorities because his indifference was setting a bad example to other students.

He applied for admission to the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. His first attempt was a failure because he failed exams in botany, zoology and languages. However, he passed the next year and in 1900 became a Swiss citizen.

At college, he met a fellow student Mileva Maric, and after a long friendship, they married in 1903; they had two sons before divorcing several years later.

In 1896 Einstein renounced his German citizenship to avoid military conscription. For five years he was stateless, before successfully applying for Swiss citizenship in 1901. After graduating from Zurich college, he attempted to gain a teaching post but none was forthcoming; instead, he gained a job in the Swiss Patent Office.

While working at the Patent Office, Einstein continued his own scientific discoveries and began radical experiments to consider the nature of light and space.

Einstein in 1921

He published his first scientific paper in 1900, and by 1905 had completed his PhD entitled “ A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions . In addition to working on his PhD, Einstein also worked feverishly on other papers. In 1905, he published four pivotal scientific works, which would revolutionise modern physics. 1905 would later be referred to as his ‘ annus mirabilis .’

Einstein’s work started to gain recognition, and he was given a post at the University of Zurich (1909) and, in 1911, was offered the post of full-professor at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague (which was then part of Austria-Hungary Empire). He took Austrian-Hungary citizenship to accept the job. In 1914, he returned to Germany and was appointed a director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics. (1914–1932)

Albert Einstein’s Scientific Contributions

Quantum Theory

Einstein suggested that light doesn’t just travel as waves but as electric currents. This photoelectric effect could force metals to release a tiny stream of particles known as ‘quanta’. From this Quantum Theory, other inventors were able to develop devices such as television and movies. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.

Special Theory of Relativity

This theory was written in a simple style with no footnotes or academic references. The core of his theory of relativity is that:

“Movement can only be detected and measured as relative movement; the change of position of one body in respect to another.”

Thus there is no fixed absolute standard of comparison for judging the motion of the earth or plants. It was revolutionary because previously people had thought time and distance are absolutes. But, Einstein proved this not to be true.

He also said that if electrons travelled at close to the speed of light, their weight would increase.

This lead to Einstein’s famous equation:

Where E = energy m = mass and c = speed of light.

General Theory of Relativity 1916

Working from a basis of special relativity. Einstein sought to express all physical laws using equations based on mathematical equations.

He devoted the last period of his life trying to formulate a final unified field theory which included a rational explanation for electromagnetism. However, he was to be frustrated in searching for this final breakthrough theory.

Solar eclipse of 1919

In 1911, Einstein predicted the sun’s gravity would bend the light of another star. He based this on his new general theory of relativity. On 29 May 1919, during a solar eclipse, British astronomer and physicist Sir Arthur Eddington was able to confirm Einstein’s prediction. The news was published in newspapers around the world, and it made Einstein internationally known as a leading physicist. It was also symbolic of international co-operation between British and German scientists after the horrors of the First World War.

In the 1920s, Einstein travelled around the world – including the UK, US, Japan, Palestine and other countries. Einstein gave lectures to packed audiences and became an internationally recognised figure for his work on physics, but also his wider observations on world affairs.

Bohr-Einstein debates

During the 1920s, other scientists started developing the work of Einstein and coming to different conclusions on Quantum Physics. In 1925 and 1926, Einstein took part in debates with Max Born about the nature of relativity and quantum physics. Although the two disagreed on physics, they shared a mutual admiration.

As a German Jew, Einstein was threatened by the rise of the Nazi party. In 1933, when the Nazi’s seized power, they confiscated Einstein’s property, and later started burning his books. Einstein, then in England, took an offer to go to Princeton University in the US. He later wrote that he never had strong opinions about race and nationality but saw himself as a citizen of the world.

“I do not believe in race as such. Race is a fraud. All modern people are the conglomeration of so many ethnic mixtures that no pure race remains.”

Once in the US, Einstein dedicated himself to a strict discipline of academic study. He would spend no time on maintaining his dress and image. He considered these things ‘inessential’ and meant less time for his research. Einstein was notoriously absent-minded. In his youth, he once left his suitcase at a friends house. His friend’s parents told Einstein’s parents: “ That young man will never amount to anything, because he can’t remember anything.”

Although a bit of a loner, and happy in his own company, he had a good sense of humour. On January 3, 1943, Einstein received a letter from a girl who was having difficulties with mathematics in her studies. Einstein consoled her when he wrote in reply to her letter

“Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics. I can assure you that mine are still greater.”

Einstein professed belief in a God “Who reveals himself in the harmony of all being”. But, he followed no established religion. His view of God sought to establish a harmony between science and religion.

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.”

– Einstein, Science and Religion (1941)

Politics of Einstein

Einstein described himself as a Zionist Socialist. He did support the state of Israel but became concerned about the narrow nationalism of the new state. In 1952, he was offered the position as President of Israel, but he declined saying he had:

“neither the natural ability nor the experience to deal with human beings.” … “I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it.”

Einstein receiving US citizenship.

Albert Einstein was involved in many civil rights movements such as the American campaign to end lynching. He joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and considered racism, America’s worst disease. But he also spoke highly of the meritocracy in American society and the value of being able to speak freely.

On the outbreak of war in 1939, Einstein wrote to President Roosevelt about the prospect of Germany developing an atomic bomb. He warned Roosevelt that the Germans were working on a bomb with a devastating potential. Roosevelt headed his advice and started the Manhattan project to develop the US atom bomb. But, after the war ended, Einstein reverted to his pacifist views. Einstein said after the war.

“Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I would not have lifted a finger.” (Newsweek, 10 March 1947)

In the post-war McCarthyite era, Einstein was scrutinised closely for potential Communist links. He wrote an article in favour of socialism, “Why Socialism” (1949) He criticised Capitalism and suggested a democratic socialist alternative. He was also a strong critic of the arms race. Einstein remarked:

“I do not know how the third World War will be fought, but I can tell you what they will use in the Fourth—rocks!”

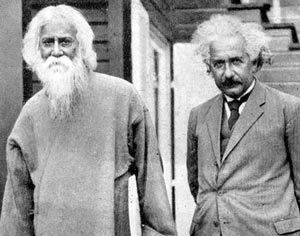

Rabindranath Tagore and Einstein

Einstein was feted as a scientist, but he was a polymath with interests in many fields. In particular, he loved music. He wrote that if he had not been a scientist, he would have been a musician. Einstein played the violin to a high standard.

“I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music… I get most joy in life out of music.”

Einstein died in 1955, at his request his brain and vital organs were removed for scientific study.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Albert Einstein ”, Oxford, www.biographyonline.net 23 Feb. 2008. Updated 2nd March 2017.

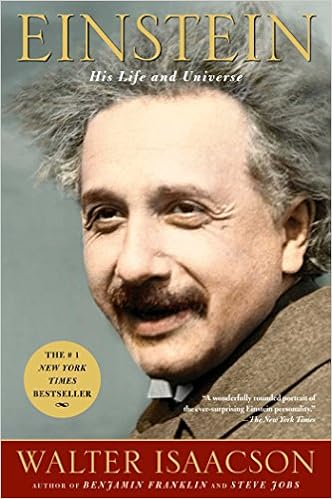

Albert Einstein – His Life and Universe

Albert Einstein – His Life at Amazon

Related pages

53 Interesting and unusual facts about Albert Einstein.

19 Comments

Albert E is awesome! Thanks for this website!!

- January 11, 2019 3:00 PM

Albert Einstein is the best scientist ever! He shall live forever!

- January 10, 2019 4:11 PM

very inspiring

- December 23, 2018 8:06 PM

Wow it is good

- December 08, 2018 10:14 AM

Thank u Albert for discovering all this and all the wonderful things u did!!!!

- November 15, 2018 7:03 PM

- By Madalyn Silva

Thank you so much, This biography really motivates me a lot. and I Have started to copy of Sir Albert Einstein’s habit.

- November 02, 2018 3:37 PM

- By Ankit Gupta

Sooo inspiring thanks Albert E. You helped me in my report in school I love you Albert E. 🙂 <3

- October 17, 2018 4:39 PM

- By brooklynn

By this inspired has been I !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- October 12, 2018 4:25 PM

- By Richard Clarlk

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Teach students checking vs. savings accounts!

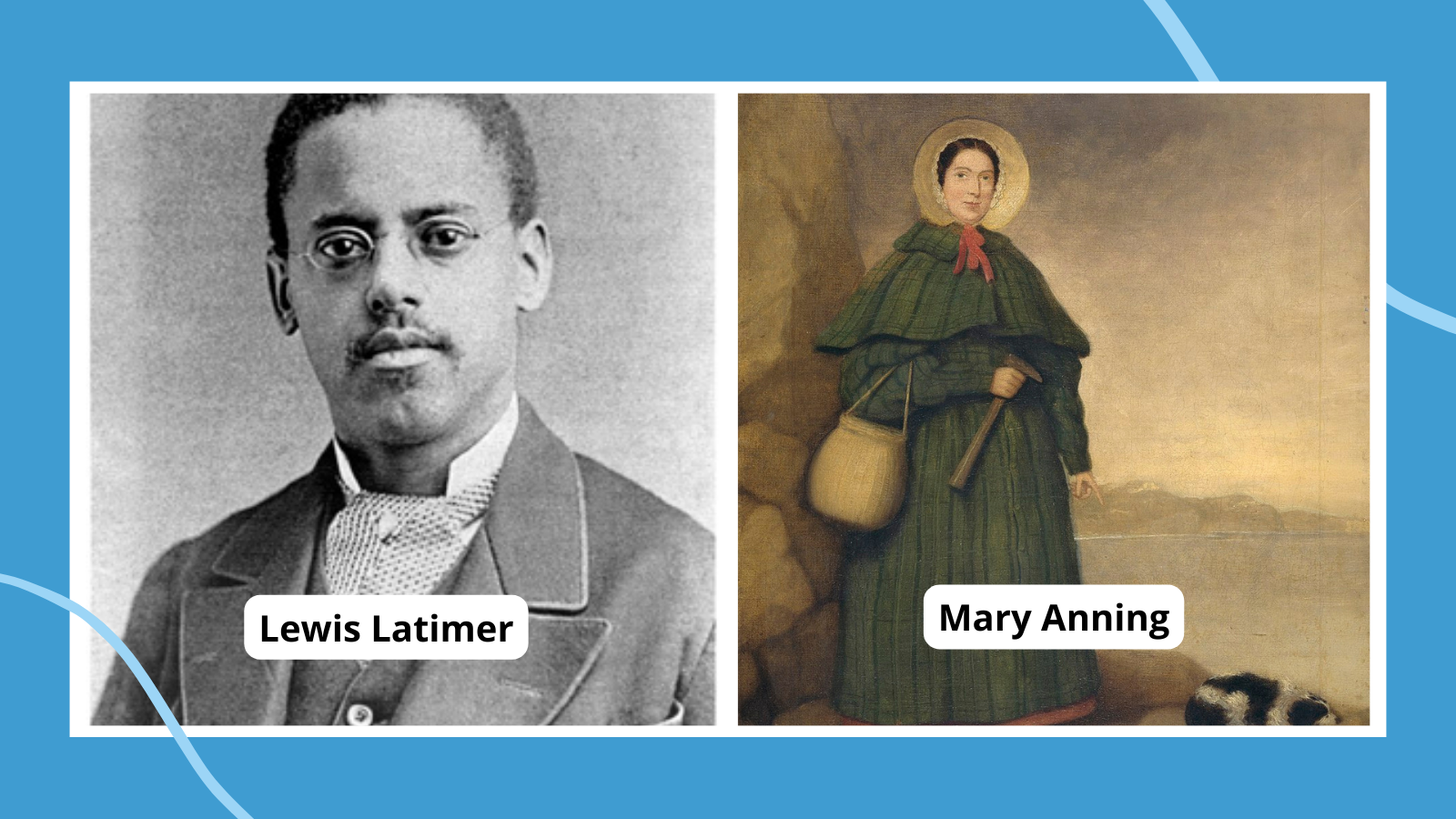

34 Famous Scientists Everyone Should Know

The people who break barriers, make discoveries, and show us what is possible.

From one hypothesis to the next, these famous scientists have made discoveries that saved lives, uncovered entire species, and reached into outer space. Understanding scientists—who they are/were and what they discovered—adds depth to facts and topics from dinosaurs to vaccines. Here are 34 scientists, from early history to today, who made and are making the discoveries that shape our world.

Famous Astronomers

Famous biologists, famous doctors and chemists, famous geologists and paleontologists, famous physicists.

- Famous Engineers

Scientists who explore the skies and teach us what we know about the universe, astronomers are literally out of this world.

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642)

Known as the founder of modern physics and one of the most famous scientists ever, Galileo discovered many theories and laws in his lifetime, including the law of inertia. He also improved upon the telescope and discovered several astronomical observations.

Learn more about Galileo at the Royal Museums Greenwich.

Try it: Conduct a bottle-drop experiment to test the laws of gravity.

Edwin Hubble (1889–1953)

Hubble discovered several galaxies beyond the Milky Way, opening up a whole new world of possibilities within astronomy. The Hubble Space Telescope was named after Hubble and his contributions.

Learn more about Edwin Hubble at NASA.

Try it: Make your own telescope using a variety of craft supplies.

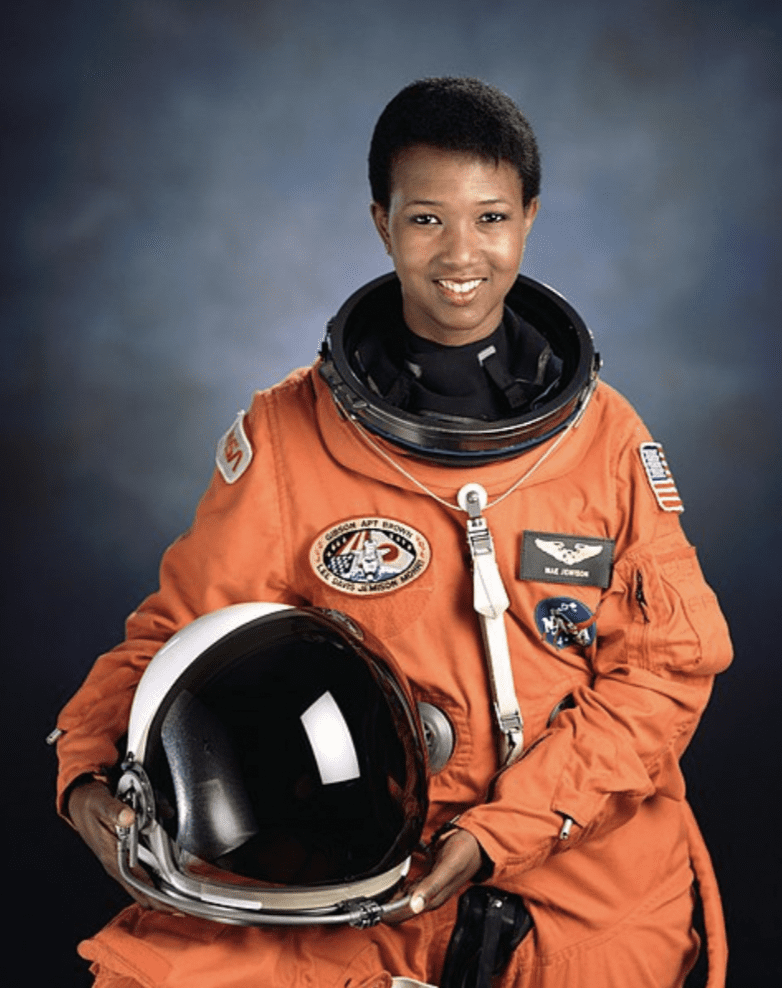

Mae Jemison (born 1956)

Mae Jemison was the first African American woman to launch into space. She also participated in the bone cell research experiment that took place on her expedition. ADVERTISEMENT

Learn more about Mae Jemison at the National Women’s History Museum.

Try this: Explore this Space Place page from NASA for some fun space experiments and activities.

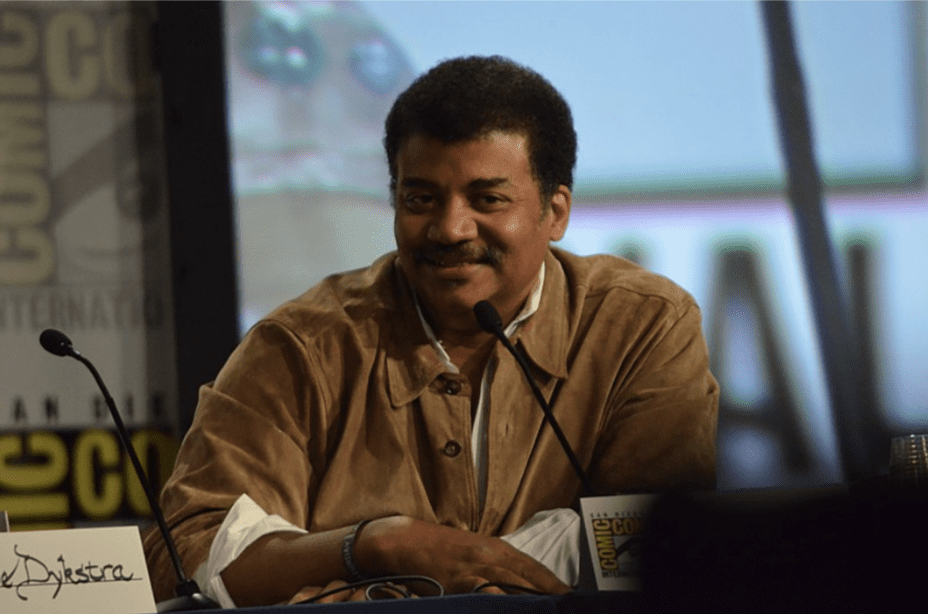

Neil deGrasse Tyson (born 1958)

One of the most famous scientists today, Neil deGrasse Tyson is known for making discoveries in cosmology, stellar formation, and astronomy. Tyson is a fascinating scientist and author of several books that popularized science for the general public. He is also the director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City.

Learn more about Neil deGrasse Tyson at the American Museum of Natural History.

Try it: Make an astrolobe and learn how to use it.